Abstract

The influence of interpersonal communication on sexual adjustment in cohabiting heterosexual couples was investigated. Male and female partners from 76 heterosexual couples independently completed measures of their own and their partners’ sexual preferences, as well as measures of sexual and general relationship adjustment, sexual difficulties, marital role preferences, depression, and social desirability. Results indicated that sexual satisfaction in both partners was associated with men’s understanding of their partner’s preferences and agreement between their preferences. The influential role of men’s understanding was supported by hierarchical regression, convergent and discriminant evidence, and multiple regression models that accounted for 51% and 63% of variance in men’s and women’s sexual satisfaction. General relationship adjustment of both partners was associated with women’s understanding of men’s marital role preferences. An explanation of Understanding’s function is proposed, accounting for gender differences within and across sexual and general realms of relating.

Most theoretical models of human sexuality emphasize the importance of interpersonal communication in maintaining sexual adjustment. For example, Wincze and Carey (1991) state that “In many cases, sexual dysfunction problems cannot be addressed until communication improves” (p. 110). Despite theorists’ claims, evidence of the importance of sexual communication and of the characteristics of adequate sexual communication is lacking. It may be that communication allows partners to develop similar and compatible sexual “scripts” (Rosen & Leiblum, 1988). On the other hand, satisfying one another may depend on understanding each other’s sexual needs or scripts.

Two studies have examined directly the relationship between communication and sexual adjustment. Perlman and Abramson (1982) reported no relationship between sexual satisfaction and a self-report measure of sexual communication whereas Metz and Dwyer (1993) used self- and partner-report ratings to learn that couples in which the man had a sexual dysfunction were characterized by conflict avoidant men. However, the psychometric properties of communication measures in these studies were not adequately addressed, limiting confidence in their findings.

Because sexual communication may be regarded as a process in which information is exchanged, measuring the information itself (content) represents a valuable alternative to studying either the process of verbal exchange or participants’ self-reported views of their communication. The term “Co-orientation” was introduced by Newcomb (1953) and refers to an “interactive model” that is “cognitively-oriented” and focused on “information-based communication processes” (O’Keefe & Reid-Nash, 1987, p. 431). Using a paired-report method, co-orientation examines relationships between two individuals’ cognitions about some topic, as well as their perceptions of each others’ cognitions. In a heterosexual couple, for example, the woman’s understanding of the man’s preferred sexual practices refers to the comparison between his reported preferences and her perception/estimation of his self-report. Agreement refers to the concordance between their reported preferences.

The basic principles of co-orientation are evident in the Sexual Interaction Inventory (SII; LoPiccolo & Steger, 1974). Two subscales of the measure reflect partners’ “perceptual accuracy” of one another. Each is generated by the difference between how pleasurable one individual rates a particular sexual behavior and the mate’s estimation of the first person’s pleasure. These are, essentially, measures of understanding. Agreement is not included among the SII’s scales, so the relative significance among co-orientation variables has not been addressed. A more important limitation of the SII is that the perceptual accuracy scales contribute to the summary scale of sexual (dis)satisfaction. The confounding of these constructs renders investigation of their association with the SII problematic.

Thus, extant research provides little evidence regarding the role of sexual communication. Among the many unanswered questions, six motivated our inquiry. First, is sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships associated with better communication? Second, which elements of communication are most important for couples’ sexual adjustment? Is the husband’s sexual satisfaction associated with his understanding of his wife’s sexual preferences, with her understanding of him, with agreement between their preferences, or all three? Rosen and Leiblum (1988) emphasize compatible scripts, suggesting the importance of agreement. By contrast, the role of understanding is implied by those who emphasize “reciprocal feedback … to secure and give effective erotic stimulation” (Kaplan, 1974, p. 134).

Third, do understanding and agreement contribute any unique variance to the estimation of sexual adjustment? The importance of each would receive additional support if a competing variable could not account for its association with sexual satisfaction. Variables shown to be related to sexual satisfaction include depression (LoPiccolo & Friedman, 1988), poorer relationship adjustment (Persky et al., 1982), and the presence of children (Apt & Hurlbert, 1992). Individual characteristics, such as erotophilia (i.e., a positive orientation toward sexuality have also been linked to sexual satisfaction. The influence of age, marital status, number of previous partners, education, and other variables remains unclear. Fourth, will convergent and discriminant correlational evidence support the association of sexual adjustment with co-orientation variables? Fifth, does co-orientation operate similarly or differently when applied to the broader, non-sexual aspect of couples’ relationships? Research has not examined co-orientation separately in these two relational domains. Sixth, how much variance in sexual satisfaction can be accounted for by sexual co-orientation and other variables, using true stepwise multiple regression?

Method

Participants

Seventy-six heterosexual couples participated. Sixty-three couples were legally married and 13 were cohabiting (M = 9.57 yrs living together). Couples had an average of 2 children and 2 years of education beyond high school. Men were older than women (M = 35.4 vs. 34.0 yrs). Most participants were Caucasian (91%). The modal household income ranged from $30,000 to $45,000.

Dependent Variables

Index of Sexual Satisfaction (ISS; Hudson, Harrison, & Crosscup, 1981)

This 25-item self-report inventory, which elicits responses on a 5-point Likert-type scale, is balanced for positive and negative items and yields scores from 0 to 100. Higher scores reflect greater sexual dissatisfaction. Internal consistency has been demonstrated by the original authors (alpha = .91) and was supported in this sample (alpha = .89). The ISS is reliable over a one week interval (r = .93) and discriminates between couples with and without sexual problems (Hudson et al., 1981).

The Sexual Difficulties items from the marital relations questionnaire (Frank, Anderson, & Rubinstein, 1978) were used as an additional index of sexual adjustment. Each person may endorse 0 to 14 difficulties for each partner (up to 28 for the couple). These 28 items have been shown to discriminate between marital and sex therapy patients and between patient and non-patient couples (Frank, Anderson, & Rubinstein, 1980). Internal consistency was supported in this sample (alpha = .77).

Co-orientation Variables

Inventory of Dyadic Heterosexual Preferences and Inventory of Dyadic Heterosexual Preferences-Other (IDHP & IDHP-O; Purnine, Carey, & Jorgensen, 1996, in press)

The 27-item IDHP is an empirically derived, reliable and valid measure of individuals’ sexual behavior preferences. Each item is a statement of preference (e.g., “I would prefer to have sex under the bedcovers and with the lights off”), followed by a 6 point Likert scale (“strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”). Factor analysis identified six scales, each reflecting an area of preference: erotophilia, use of contraception, conventionality, use of erotica, use of drugs/alcohol, and romantic foreplay. Each scale score ranges from 1 to 6, calculated as the mean of item responses, with higher scores indicating greater endorsement. The scales are internally consistent (M alpha = .72), reliable (M test-retest r = .84), and their construct validity has been supported by correlations with criterion measures. In this study, these scales are a secondary function of the IDHP. The IDHP’s primary function was to generate scores of sexual Agreement and Understanding, calculated from the pool of all 27 items. For this purpose, the IDHP-O was also administered. The IDHP-O asks respondents to indicate how he or she believes their partner would respond to each item. A couple’s agreement is reflected by the Spearman correlation between their IDHPs. Each person’s understanding compares the partner’s IDHP to one’s own responses on the IDHP-O.

Marital role preferences

To operationalize behavioral preferences that pertain to general aspects of relationships, and the co-orientation of these preferences, we modified items from the marital relations questionnaire (Frank et al., 1978). The original measure contained 10 role-related behaviors, preceded by a sentence-stem (“In your opinion who should…”). Respondents checked “wife,” “husband,” “both,” or “neither.” We included these items and repeated them, with a different sentence-stem: “In your spouse or partner’s opinion, who should….” The response format for all 20 items was replaced with a Likert scale, anchored by “wife” and “husband,” in order to elicit continuous variability.

Other Explanatory Variables

Demographic variables

A brief structured interview helped to establish rapport and recorded age, marital status and duration, income, education, race, religious affiliation, and number and ages of children. Embedded in one of the written questionnaires was an item that asked respondents to estimate the total number of sex partners over the course of their lives.

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977)

The CESD measures depressive symptoms in the general population. Responses to 20 symptom-related statements are made on a four-point scale according to their frequency during the last week. Scores range from 0 to 60. Internal consistency was supported in this sample (alpha = .82) and original samples (alpha = .84 to .90). Validity has been supported by correlations with other self-report measures and clinical ratings of depression.

Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976)

This 32-item self-report measure of relationship satisfaction is internally consistent (alpha = .95), temporally stable (r = .87; Carey, Spector, Lantinga, & Krauss, 1993), and discriminates between distressed and non-distressed couples (Eddy, Heyman, & Weiss, 1991). The DAS has four factors: Dyadic Consensus, Satisfaction, and Cohesion as well as Affectional Expression. Because items in the last factor refer to “sex relations,” frequency of kissing, and being too tired for sex, there is overlap with the project’s main dependent variable, “sexual satisfaction.” For this reason, a composite of the first three subscales was used. Revised scores (DAS-R) were internally consistent (alpha = .89) and correlated with original DAS scores (r= .99, p < .0001).

Social Desirability Scale (SDS; Crowne & Marlowe, 1960)

This is a well-established self-report measure of the tendency to present oneself in a socially desirable manner. It contains 33 true/false items, some of which are reverse-scored. The original authors reported high internal consistency (alpha = .88) and a one month test-retest correlation of .89. Internal consistency was lower in this sample (alpha = .77).

Procedures

Flyers and newspaper advertisements solicited couples stating that they would receive $20 for participation in a “Couples Study.” Interested individuals left their telephone number on an answering machine. Only when called back did they receive an overview of the study, to reduce volunteer bias (Bogaert, 1996). Inclusion criteria required that couples were heterosexual, cohabiting for at least one year, between 25 and 50 years of age, not pregnant, and not less than six months postpartum.

Home visits were conducted by the senior author and a female assistant. Sessions began with both partners sitting in the same room and the investigator(s) providing an overview of the study. Couples were assured that their responses would remain confidential and that even their spouse/partner would not be allowed to see their responses. It was explained that names would not be associated with their records and that feedback regarding the couple’s functioning would not be possible. Consent forms were completed, and for the remainder of the session, assessment took place in separate rooms to ensure that respondents were not influenced by their partner. After the interview, participants completed the questionnaires, were compensated, and debriefed.

Results

Most participants (97%) completed all measures. The mean, standard deviation, and range of all variables are reported in Table 1. A normality test based on skewness and kurtosis (D’Agostino, Balanger, & D’Agostino, 1990) was performed on each non-demographic variable; if the assumption of normality was rejected at p ≤ .05, ladder-of-powers variable transformations were examined to most closely approximate normality (Tukey, 1977). A square root transformation was performed on scores of sexual dissatisfaction, sexual difficulties, depression, and sexual conventionality. A square transformation was applied to the three sexual co-orientation variables, dyadic adjustment, and the following sexual behavior preferences: erotophilia, use of contraception, use of erotica, and romantic foreplay. No transformations improved the shape of “use of drugs/alcohol” and none was necessary for social desirability.

Table 1.

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Range of Variables

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | t | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | |||||||

| Sexual (Dis)satisfaction (ISS) | |||||||

| Men | 18.93 | 11.89 | 0 | 55 | |||

| Women | 17.45 | 13.21 | 0 | 52 | 1.30 | 75 | .20 |

| Sexual Difficulties | |||||||

| Women’s report of men | 1.46 | 1.46 | 0 | 7 | |||

| Men’s report of men | 2.13 | 1.49 | 0 | 6 | 3.35 | 74 | .00 |

| Women’s report of women | 2.74 | 2.40 | 0 | 9 | |||

| Men’s report of women | 3.50 | 2.84 | 0 | 12 | 2.44 | 73 | .02 |

| Women’s report of total | 4.20 | 3.52 | 0 | 16 | |||

| Men’s report of total | 5.64 | 3.86 | 0 | 18 | 3.26 | 73 | .00 |

| Co-orientation Variables | |||||||

| Agreement | .49 | .22 | −.27 | .88 | |||

| Men’s understanding | .59 | .19 | −.15 | .87 | |||

| Women’s understanding | .60 | .16 | .14 | .92 | −.23 | 75 | .82 |

| Other Explanatory Variables | |||||||

| Depression (CESD) | |||||||

| Men | 9.58 | 6.17 | 0 | 30 | |||

| Women | 11.08 | 7.86 | 0 | 34 | 1.5 | 75 | .15 |

| Dyadic Adjustment (DAS) | |||||||

| Men | 109.0 | 12.49 | 78 | 136 | |||

| Women | 111.5 | 13.81 | 69 | 143 | 1.84 | 75 | .07 |

| Men (DAS-R) | 100.5 | 11.47 | 69 | 125 | |||

| Women (DAS-R) | 102.5 | 12.61 | 62 | 131 | 1.59 | 75 | .12 |

| Social Desirability (SDS) | |||||||

| Men | 15.20 | 5.11 | 4 | 26 | |||

| Women | 15.17 | 5.15 | 5 | 29 | .11 | 74 | .91 |

| Sexual Behavior Preferences (IDHP) | |||||||

| Erotophilia | |||||||

| Men | 4.54 | .54 | 3.00 | 5.86 | |||

| Women | 4.30 | .72 | 1.86 | 5.57 | 2.41 | 75 | .0184 |

| Use of Contraception | |||||||

| Men | 3.90 | 1.06 | 1.25 | 6.00 | |||

| Women | 4.45 | .99 | 1.25 | 6.00 | 3.58 | 75 | .0006 |

| Conventionality | |||||||

| Men | 2.54 | .73 | 1.25 | 5.00 | |||

| Women | 2.69 | .88 | 1.00 | 4.75 | 1.19 | 75 | .2390 |

| Use of Erotica | |||||||

| Men | 4.30 | 1.04 | 1.25 | 6.00 | |||

| Women | 3.78 | 1.28 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 3.40 | 75 | .0011 |

| Use of Drugs/Alcohol | |||||||

| Men | 2.43 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 5.75 | |||

| Women | 2.09 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.64 | 75 | .0101 |

| Romantic Foreplay | |||||||

| Men | 4.38 | .72 | 2.25 | 6.00 | |||

| Women | 4.94 | .69 | 2.25 | 6.00 | 5.24 | 75 | .0000 |

Note. Min. = minimum; Max. = maximum; ISS = Index of Sexual Satisfaction; CESD = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale; DAS-R = Dyadic Adjustment Scale - Revised (with “affectional expression” factor removed); SDS = Social Desirability Scale; IDHP = Inventory of Dyadic Heterosexual Preferences. For each instrument, higher scores indicate higher levels of the variable measured.

1. Association between sexual co-orientation and sexual satisfaction

Correlations between sexual dissatisfaction and all explanatory variables are listed in Table 2. For both men and women, there was evidence (p ≤ .002) that sexual satisfaction is associated with couple agreement and men’s understanding of women’s preferences. Women’s understanding of men’s sexual preferences was not significantly correlated with men’s satisfaction, although it was related to women’s own satisfaction.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Sexual Dissatisfaction and Explanatory Variables

| Sexual Dissatisfaction | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||||||

| Sexual Co-orientation Variables | |||||||

| Agreement | −.35** | −.46** | |||||

| Men’s understanding | −.38** | −.43** | |||||

| Women’s understanding | −.13 | −.27* | |||||

| Social Desirability | |||||||

| Men | −.17 | .05 | |||||

| Women | −.02 | −.18 | |||||

| Depression | |||||||

| Men | .15 | .28* | |||||

| Women | .19 | .29** | |||||

| Dyadic Adjustment | |||||||

| Men | −.39*** | −.40*** | |||||

| Women | −.36** | −.61*** | |||||

| Sexual Behavior Preferences | |||||||

| Erotophilia | |||||||

| Men | −.13 | −.01 | |||||

| Women | −.31** | −.30** | |||||

| Use of Contraception | |||||||

| Men | .01 | −.01 | |||||

| Women | −.19 | −.26* | |||||

| Conventionality | |||||||

| Men | .30** | .14 | |||||

| Women | .41*** | .45*** | |||||

| Use of Erotica | |||||||

| Men | .16 | .16 | |||||

| Women | .03 | .13 | |||||

| Use Drugs/Alcohol | |||||||

| Men | .00 | .04 | |||||

| Women | .11 | .19 | |||||

| Romantic Foreplay | |||||||

| Men | −.08 | −.07 | |||||

| Women | −.46*** | −.42*** | |||||

| Demographic Variables | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| Men | −.11 | .00 | |||||

| Women | −.15 | −.11 | |||||

| Relationship Duration | −.07 | −.05 | |||||

| Number of Children | |||||||

| Total | −.17 | −.08 | |||||

| at home | −.07 | −.08 | |||||

| 10 yrs. old or younger | .01 | −.03 | |||||

| 5 yrs. old or younger | .04 | −.01 | |||||

| children + others at home | −.15 | −.10 | |||||

| Lifetime # Partners | |||||||

| Men | −.03 | .20 | |||||

| Women | .03 | .20 | |||||

| Family Income | .04 | .02 | |||||

| Years of Education | |||||||

| Men | .09 | .04 | |||||

| Women | .35** | .18 | |||||

Note. To explore the role of children as a dichotomous variable, 15 childless couples were compared to the 61 couples who had children. Sexual satisfaction did not differ among men (|t| = 1.24, p ≤ .22) or women (|t| = 1.18, p ≤ .24).

p≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

2. Relative importance among sexual co-orientation variables

Significant partial correlations between a man’s understanding and his (r = −.26, p ≤ .02) and his partner’s (r = −.24, p ≤ .04) sexual dissatisfaction support the influence of this variable, apart from the contribution of agreement and women’s understanding. The unique contribution of agreement was supported among women (r = −.28, p ≤ .01), though it was marginal with regard to men’s sexual dissatisfaction (r = −.21, p ≤ .08). Partial correlations did not support a unique contribution of women’s understanding to the sexual adjustment of women (r = .04, p ≤.72) or men (r = .08, p ≤ .50). Because convergent and discriminant evidence (described later) also failed to support the role of this variable, further analyses focused on the roles of agreement and men’s understanding only.

3. Sexual agreement and men’s understanding versus other potentially relevant variables

Sexual dissatisfaction was unrelated to social desirability response bias and most demographic variables, but it was related to several other variables (see Table 2). Nevertheless, across 30 hierarchical regression equations, the unique contributions of agreement and men’s understanding remained significant (p ≤ .05) in 29 instances (p ≤ .01 in 25 cases). Only agreement failed to contribute significant additional variance in estimating men’s dissatisfaction beyond that accounted for by their partners’ interest in romantic foreplay.

4. Convergent and discriminant support for main hypotheses

Table 3 includes correlations between sexual co-orientation variables and the number of sexual difficulties in the couple. These figures provide additional evidence that men’s understanding is related to couples’ sexual adjustment. Agreement was significantly associated with sexual difficulties as reported by women but not by men. Convergent evidence was not obtained for the association between sexual adjustment and women’s understanding.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Sexual Co-orientation, Marital Co-orientation, and Sexual and Marital Adjustment

| Sexual Dissatisfaction | Dyadic Adjustment | Sexual Difficulties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-orientation | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| Sexual Preference | ||||||

| Agreement | −.35** | −.46** | .25* | .30** | −.22 | −.29** |

| Men’s understanding | −.38** | −.43** | .12 | .08 | −.33** | −.27* |

| Women’s understanding | −.13 | −.27* | .17 | .19 | −.03 | −.18 |

| Marital Role Preference | ||||||

| Agreement | .12 | .09 | −.04 | −.08 | .24* | .19 |

| Men’s understanding | −.02 | .11 | −.03 | .02 | .19 | .16 |

| Women’s understanding | .09 | .26* | −.30** | −.40** | .31** | .25* |

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01.

Evidence suggested that the explanatory power of men’s understanding discriminates between sexual and generic dyadic adjustment, as it was unrelated to the latter. Sexual agreement did not discriminate between the broad and narrow aspects of a relationship, though its correlations with general relationship satisfaction were somewhat smaller.

5. Co-orientation applied to the general relationship

The bottom half of Table 3 reports on the co-orientation of marital role preferences. Results were the inverse of those for sexual co-orientation. Agreement and men’s understanding were not related to dyadic adjustment of women or men, whereas women’s understanding of their male partners’ preferences was related to the dyadic adjustment of both. Being aware of the husband’s general role preferences may be important for sexual as well as general aspects of the relationship, as indicated by 3 of 4 significant correlations.

6. Model building

Stepwise multiple regression was used to account for as much variance in individuals’ levels of sexual satisfaction as possible. For each partner, a pool of potential carriers (i.e., “predictors”) included all variables whose simple correlations with sexual dissatisfaction were significant at p ≤ .05 (see Table 2). This pool included 10 carriers for the estimation of female sexual satisfaction and 9 carriers for male satisfaction (see Table 4). True stepwise backward regression was specified, with a value of F = 1.0 to stay and F = 1.0 to enter. This procedure includes the entire pool of variables in an initial model, eliminating variables one by one, based on their value of F to stay. True stepwise regression allows for the re-introduction, at each step, of carriers that were previously dropped, if their F to enter value exceeds 1.0. This is an important feature when there is multicollinearity among carriers, because a carrier dropped early may prove significant in the absence of related carriers that are dropped later.

Table 4.

True Stepwise Multiple Regression, Estimating Sexual Dissatisfaction

| Women’s sexual dissatisfactiona | Men’s sexual dissatisfactionb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | p | F | F | p | |

| Carriers dropped | ||||||

| Women’s use of contraception | .00 | |||||

| Agreement | .04 | .00 | ||||

| Men’s dyadic adjustment | .05 | |||||

| Carriers Retained | ||||||

| Women’s dyadic adjustment | 31.23 | .00 | 1.91 | .17 | ||

| Women’s depression | 1.59 | .21 | ||||

| Women’s erotophilia | 1.61 | .21 | 1.40 | .24 | ||

| Women’s conventionality | 1.56 | .22 | 3.45 | .07 | ||

| Women’s romantic foreplay | 12.95 | .00 | 7.47 | .01 | ||

| Women’s education | 6.61 | .01 | ||||

| Men’s conventionality | 1.20 | .28 | ||||

| Men’s understanding | 8.68 | .00 | 2.08 | .15 | ||

| Men’s dyadic adjustment | 4.44 | .04 | ||||

| Men’s depression | 2.72 | .10 | ||||

R2 = .63, F(7,68) = 16.86 (p ≤ .0001)

R2 = .51, F(8,67) = 8.82 (p ≤ .0001)

Table 4 illustrates the results of these procedures, including F-values of variables that were dropped from the model and those that were retained. A majority of the variance in women’s (63%) and men’s (51%) sexual satisfaction was accounted for by a subset of the variable pool. For women’s satisfaction, important contributors included high levels of men’s understanding, female dyadic adjustment, and the woman’s preferences toward romantic foreplay. For men’s satisfaction, higher male dyadic adjustment was significant, as was the female partner’s romantic foreplay and lack of education. Men’s understanding was retained, but its contribution to the model was not statistically significant.

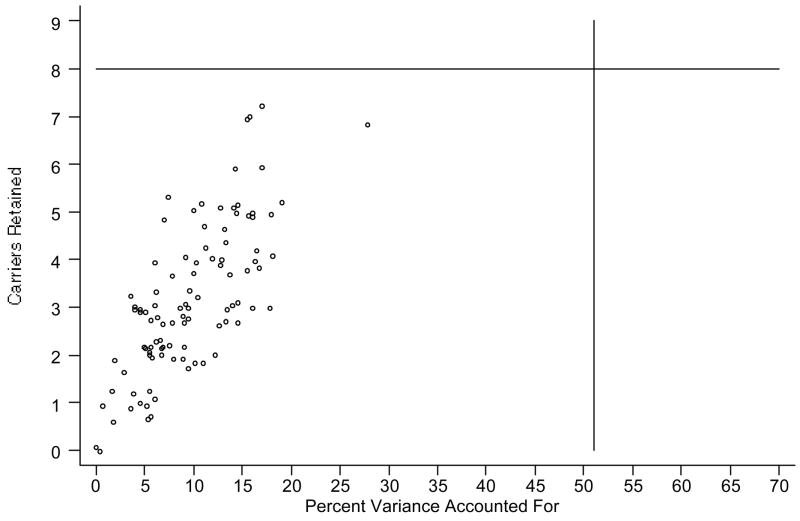

To allow for generalization from this sample, it was necessary to rule out the possibility that these results may have occurred by chance. Bootstrapping replications offer a valuable alternative to a true replication study or a split-half replication, in which a larger sample is divided into two sub samples. In bootstrapping, actual values of the dependent variable are reassigned randomly to create an artificial data set, and the same regression methods are then used to fit this purely random data. This process is repeated 99 times and the results, reflecting chance findings, are compared with the one actual model. The number of variables retained by each of these models may then be plotted against the variance explained by each (Figures 1 & 2). These figures illustrate the range of chance findings with regard to the number of carriers and the variance accounted for (as well as the positive relation between the two). Out of 100 equations that were plotted for men and women, only the actual model (1/100) accounted for 51% (men) or 63% (women) of variance, leading to a p-value ≤ .01. Moreover, these figures illustrate that none of the random results even came close to accounting for such large portions of variance. The structure of the models was also supported. For men, the true model was the only one out of 100 (p ≤ .01) that retained 8 carriers. For women, the actual model was 1 of 4 (p ≤ .04) that retained 7 carriers.

Figure 1.

Variables retained versus variance accounted for in 99 bootstrap replications, estimating male sexual satisfaction. Horizontal line represents 8 carriers retained by the model. Vertical line represents 51% of variance (R2) accounted for in men’s sexual satisfaction. Data points represent intersection of carriers retained and R2 for each regression equation on randomized resampling of dependent variable. Data points have been slightly displaced from their true positions for illustrative purposes, as many overlap.

Figure 2.

Variables retained versus variance accounted for in 99 bootstrap replications, estimating female sexual satisfaction. Horizontal line represents 7 carriers retained by the model. Vertical line represents 63% of variance (R2) accounted for in women’s sexual satisfaction. Data points represent intersection of carriers retained and R2 for each regression equation on randomized resampling of dependent variable. Data points have been slightly displaced from their true positions for illustrative purposes, as many overlap.

Although therapeutic interventions can increase partners’ understanding of one another (e.g., Nathan & Joanning, 1985) it may be more difficult to affect individual sexual preferences. Therefore, the latter were removed from the pool of carriers in two additional multiple regression equations, to highlight the role of Understanding. For men’s satisfaction, a four-carrier model accounted for 41% of the variance [F(4,71) = 12.18, p ≤ .0001]. Significant contributors to the model were men’s understanding (p ≤ .001), lower women’s education (p ≤ .001), and male dyadic adjustment (p ≤ .04). Female dyadic adjustment was also retained, though its contribution was nonsignificant. For women’s satisfaction, a three-carrier model accounted for 52% of the variance [F(3,72) = 26.40, p ≤ .0001]. Sexual agreement was retained, but only men’s understanding (p ≤ .001) and female dyadic adjustment (p ≤ .001) were significant contributors.

Discussion

Agreement between partners’ sexual preferences and men’s understanding of their partners’ preferences were significantly related to sexual adjustment. These variables accounted for variance in sexual satisfaction, independent of other contributing variables, and over half of the variance in sexual satisfaction was explained by a subset of variables. This study demonstrates the explanatory power of measuring communication via the structure and content of information exchange (co-orientation). Structural differences were evidenced in the different roles among men’s understanding, women’s understanding, and agreement. Different areas of content (sexual versus marital role preferences) were examined, with women’s understanding proving influential in the latter domain.

Relative Importance of Sexual Agreement, Women’s Understanding, and Men’s Understanding

Gender differences in sexual understanding have rarely been examined. Support for the influence of men’s understanding on both partners’ sexual adjustment was evident across all analyses (simple and partial correlations, hierarchical regression, convergent and discriminant evidence, model-building), but the role of women’s understanding was not supported. Differences between men’s understanding and agreement also emerged from this study. Although both were related to sexual satisfaction, agreement was also related to overall relationship adjustment. Its contribution was not specific to the sexual domain.

The Functions of Agreement and Understanding

What are the characteristics of adequate communication, and through what mechanisms does it function? To address these questions, we considered the observed differences among co-orientation variables and differences in the role of men’s and women’s understanding in sexual versus general relating. Different functions of agreement and understanding are proposed, in conjunction with established gender differences in sexual and marital roles, to account for these differences.

Agreement

Agreement presumably functions in a fairly straightforward manner. If both partners prefer the same sexual behaviors, it is more likely that sexual interactions will take place according to what is mutually acceptable and desirable. Of course, as in any correlational study, the opposite direction of influence (and other variables) must be considered. Sexual interactions that are particularly satisfying, for whatever reason (i.e., involving the influence of other variables), might reinforce specific behaviors, rendering them “preferred” by both partners. Only longitudinal studies with repeated measures of sexual satisfaction, Agreement, and other relevant variables would be able to determine the direction of such causal relationships. Such studies might determine whether satisfied couples achieved greater agreement over time, or if they simply had a good match from the beginning.

A “mismatch,” “discrepancy,” or lack of “compatibility” may be responsible for sexual difficulties according to the sexual scripting approach of Rosen and Leiblum (1988). Life changes, such as illness, aging, or the arrival of children put pressure on old scripts and require partners to negotiate script changes. The importance of matching scripts, operationalized as sexual Agreement in this study, is supported by these results. Communication research has suggested, however, that Understanding is influenced more by communication than is Agreement (Wackman, 1973). This study’s support for the role of understanding suggests that therapeutic efforts, in addition to matching scripts, should be aimed toward increasing men’s understanding of their partner’s script, regardless of the extent of Agreement.

Understanding

Understanding may be important because it allows one to know how to satisfy the partner. This perspective places emphasis on specific practices that lead to the partner’s physical gratification (arousal, orgasm). Expressed in the writing of sex therapists like Kaplan (1974), this view may explain the relationship between men’s understanding and women’s satisfaction (r = .43). Yet why is women’s understanding not associated with male satisfaction? And why would men’s understanding be related to the male’s own satisfaction (r = .38)? Essentially, men’s sexuality may be based more on performance or pleasing their partners, less on their being effectively stimulated. If so, there would be less need of sexual understanding by their partners. As communication helps one “to secure and give effective erotic stimulation” (Kaplan, 1974, p. 134), one’s own understanding may help one to “give” such stimulation and being understood by the other may help one to “secure” it. Giving stimulation may be central to men’s satisfaction and securing it may be central to women’s. Gender differences in understanding in this study may be partly explained by this conceptualization, which is informed by the view of sex therapists that male sexual functioning depends less on his partner’s behavior. That arousal and orgasm are less interpersonally dependent for men is reflected in the fact that they report more frequent masturbation as well as higher rates of orgasm when controlling for the rate of masturbation (Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994). The instrumentality implicit in male sexual scripts is also reflected in the idea that men “are all too frequently burdened with the responsibility for arousing both themselves and their partners during a sexual encounter” (Rosen & Leiblum, 1988, p. 171).

Sexual versus general relating

For males, “in sex, as elsewhere, it’s performance that counts” (Rosen & Leiblum, 1988, p. 171). This may be far from the truth, however, if “elsewhere” is considered to be the general relationship. Overall, it is the woman who is traditionally burdened with “enormous responsibility for these relationships” (Kaschak, 1992, p. 161). In reviewing research on women’s experience, Kaschak argues that a woman “learns that men are central and that her function is to please them” (p. 76). This may be why husbands were more satisfied in the general relationship if their wives had greater understanding of their preferences about marital role behaviors. In the overall relationship, women may tend to be the active “pleasers,” and therefore, need to perceive accurately their partners’ preferences in this domain. By contrast, men’s understanding was not related to relationship satisfaction.

Inferences about the performance-related function of understanding in couples’ sexual and general relationships may be complicated by sex role differences among individuals. Rosenzweig and Dailey (1989) found that the sexual satisfaction of “feminine” women was linked to a factor characterized by “partner’s responses” (i.e., the perception that the partner is responsive to her needs). This points to the role of the partner’s informed performance and suggests that the importance of having a sexually understanding partner is associated with “femininity,” apart from (or interacting with) one’s gender.

Model-Building

In a prior attempt to estimate sexual adjustment (Hurlbert, Apt, & Rabehl, 1993), 56% of the variance in women’s ISS scores was accounted for by relationship closeness, erotophilia, sexual assertiveness, excitability, sexual desire, and higher frequency of sex. Despite the absence of several of these carriers in the present study, an even higher portion of variance (63%) was accounted for, underscoring the importance of such carriers as men’s understanding. This study also included men, providing evidence that different factors may be involved in men’s and women’s sexual satisfaction and that it may be more difficult to predict the satisfaction of men (51% variance accounted for).

Dyadic adjustment and men’s understanding were shown to be a powerful pair of estimates for both partners’ sexual adjustment, when sexual behavior preferences were excluded. Dyadic adjustment has often been associated with sexual adjustment, accounting for as much as 40%–55% of variance (Persky, et al., 1982). However, we removed sexually-related items from the measure of dyadic adjustment and found that these variables shared only 15% (in men) and 35% (in women) of variance suggesting that there is more to sexual satisfaction than can be explained by the quality of the general relationship. Happy couples may have unsatisfying sex lives and poorly adjusted couples may be satisfied sexually.

Limitations, Strengths, and Recommendations

Two limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample included primarily Caucasian participants. However, research indicates that race is not a dominant factor in peoples’ sexual behavior, as there are few differences in frequency of sex, rates of orgasm, or number of partners (Laumann et al., 1994). Second, we relied upon self-report data. However, candid reports are most likely when rapport is established, confidentiality is assured, and participants believe that responses will be compared with a criterion (Maisto, McKay, & Connors, 1990). In our study, anonymous questionnaires ensured privacy and face-to-face interviews allowed us to establish rapport. In addition, the paired-report method afforded each subject the implicit knowledge that his or her responses may be checked against their partner’s. Social desirability response bias was associated with neither sexual nor dyadic adjustment.

A unique strength of the current study is the use of the co-orientation method because it bypasses the issue of response bias. Sexual Agreement and understanding are not self-report variables. They take advantage of the simplicity of self-administration, but each response is treated as a “behavior,” to be compared with that of the partner. Not surprisingly, men’s and women’s social desirability response bias were unrelated to sexual agreement or understanding.

Conclusions regarding marital co-orientation and adjustment should be interpreted with caution, as we assessed the former with an instrument originally designed for other purposes. Further research into general dyadic co-orientation requires the systematic development and psychometric assessment of new measures. Researchers could then evaluate the proposition that gender differences in Understanding are related to social norms or scripts that emphasize women’s responsibility for the overall relationship and men’s “performance,” or instrumentality, in the specifically sexual relationship. Sex-roles may modify these gender differences and should be investigated.

Research is needed to examine the effect of therapeutic interventions on partners’ sexual understanding and agreement, and to determine which improved co-orientation variables are predictive of better sexual adjustment. This may vary according to the gender of the “identified patient,” type of disorder/dysfunction, sex-role self-perception, and other factors. Such knowledge could lead to the informed use of co-orientation assessment in sex therapy (e.g., treatment planning, outcome evaluation). Because both members of a dyad play a part in the understanding of each (i.e., one person’s understanding depends on the other’s expression of information and one’s own reception of that information), both components need to be examined in relation to co-orientation structures and their change.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (K21-MH0110 and R01-MH54929). We thank Ann Kim and Meredith Knoll for their assistance with data collection and management; Kate B. Carey, Barbara H. Fiese, and Stephen A. Maisto for their comments on an earlier version of this report; John R. Gleason for his statistical consultation; and the participants for their important contributions.

References

- Apt C, Hurlbert DF. Motherhood and female sexuality beyond one year postpartum: A study of military wives. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy. 1992;18:104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert AF. Volunteer bias in human sexuality research: Evidence for both sexuality and personality differences in males. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1996;25:125–140. doi: 10.1007/BF02437932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Spector IP, Lantinga LJ, Krauss DJ. Reliability of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino RB, Balanger A, D’Agostino RB., Jr A suggestion for using powerful and informative tests of normality. The American Statistician. 1990;44:316–321. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy MJ, Heyman RE, Weiss RL. An empirical evaluation of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Exploring the differences between marital “satisfaction” and “adjustment”. Behavioral Assessment. 1991;13:199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Anderson C, Rubinstein D. Frequency of sexual dysfunction in “normal” couples. New England Journal of Medicine. 1978;299:111–115. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197807202990302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E, Anderson C, Rubinstein D. Marital role ideals and perception of marital role behavior in distressed and nondistressed couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1980;6:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WW, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC. A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. Journal of Sex Research. 1981;17:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbert DF, Apt C, Rabehl SM. Key variables to understanding female sexual satisfaction: An examination of women in nondistressed marriages. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1993;19:154–165. doi: 10.1080/00926239308404899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HS. The new sex therapy: Active treatment of sexual dysfunctions. New York: Times Books; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kaschak E. Engendered lives: A new psychology of women’s experience. New York: Harper Collins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- LoPiccolo J, Friedman JM. Broad-spectrum treatment of low sexual desire: Integration of cognitive, behavioral, and systemic therapy. In: Leiblum SR, Rosen RC, editors. Sexual desire disorders. New York: Guilford; 1988. pp. 313–347. [Google Scholar]

- LoPiccolo J, Steger J. The Sexual Interaction Inventory: A new instrument for assessment of sexual dysfunction. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1974;3:585–595. doi: 10.1007/BF01541141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, McKay JR, Connors GJ. Self-report issues in substance abuse: State of the art and future directions. Behavioral Assessment. 1990;12:117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Metz ME, Dwyer SM. Relationship conflict management patterns among sex dysfunction, sex offender, and satisfied couples. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1993;19:104–122. doi: 10.1080/00926239308404894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan EP, Joanning HH. Enhancing marital sexuality: An evaluation of a program for the sexual enrichment of normal couples. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1985;11:157–164. doi: 10.1080/00926238508405441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb TM. An approach to the study of communicative acts. Psychological Review. 1953;60:393–404. doi: 10.1037/h0063098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe GJ, Reid-Nash K. Socializing functions. In: Berger CR, Chaffee SH, editors. Handbook of communication science. Newbury Park: Sage; 1987. pp. 419–445. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman SD, Abramson PR. Sexual satisfaction among married and cohabiting individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:458–460. [Google Scholar]

- Persky H, Charney N, Strauss D, Miller WR, O’Brien CP, Lief HI. The relationship of sexual adjustment and related sexual behaviors and attitudes to marital adjustment. American Journal of Family Therapy. 1982;10:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Purnine DM, Carey MP, Jorgensen RS. The Inventory of Dyadic Heterosexual Preferences: Development and psychometric evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:375–387. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purnine DM, Carey MP, Jorgensen RS. Inventory of Dyadic Heterosexual Preferences and Inventory of Dyadic Heterosexual Preferences - Other. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, Bauserman R, Schreer G, Davis SL, editors. Sexually-related measures: A compendium. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CESD scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. A sexual scripting approach to problems of desire. In: Leiblum SR, Rosen RC, editors. Sexual desire disorders. New York: Guilford; 1988. pp. 168–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig JM, Dailey DM. Dyadic adjustment/sexual satisfaction in women and men as a function of psychological sex role and self-perception. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 1989;15:44–56. doi: 10.1080/00926238908412846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon W, Gagnon JH. A sexual scripts approach. In: Geer JH, O’Donohue WT, editors. Theories of human sexuality. New York: Plenum; 1987. pp. 363–383. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tukey JW. Exploratory data analysis. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wackman DB. Interpersonal communication and co-orientation. American Behavioral Scientist. 1973;16:537–550. [Google Scholar]

- Wincze JP, Carey MP. Sexual dysfunction: A guide for assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford; 1991. [Google Scholar]