Abstract

(±)-Mitorubrinic acid, a member of the azaphilone family of natural products, has been constructed in 12 steps. Key aspects of the synthesis include elaboration and oxidative dearomatization of an isocoumarin intermediate to provide the azaphilone nucleus with a disubstituted, unsaturated carboxylic acid side chain.

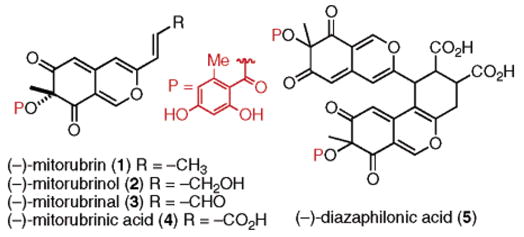

The mitorubrins are a unique subclass of azaphilones isolated from a variety of fungal species (Figure 1).1 The term azaphilone arises from the affinity of the 4H-pyran nucleus to undergo substitution with primary amines to form the corresponding vinylogous 4-pyridones. The mitorubrin subclass of azaphilones is comprised of (−)-mitorubrin (1),2 (−)-mitorubrinol (2),2 (−)-mitorubrinal (3),1 (−)-mitorubrinic acid (4),3 and its supposed dimer, diazaphilonic acid (5).4 The molecules 1–4 only differ by the oxidation state of their accompanying disubstituted E-olefinic side chain. They are closely related to the lunatoic acid family of azaphilones, which differ in their ester side chain functionality from the mitorubrins.1b

Figure 1.

The mitorubrins.

Whalley and co-workers reported an 11-step synthesis of (±)-mitorubrin (1) some time ago.5 However, a resurgence of interest accompanied recognition by the synthetic community of the diverse and distinct biological activities exhibited by the azaphilones. In particular, mitorubrinic acid (4) induces formation of chlamydospore-like cells in fungi and inhibits trypsine with an IC50 of 41 μmol/L.3b On the other hand, its presumed dimer diazaphilonic acid (5) inhibits Tth DNA polymerase with an IC50 of 2.6 μg/mL and is reported to completely inhibit MTI (human leukemia) telomerase activity at 50 μM.4

Porco has reported a concise entry to many azaphilone scaffolds using a gold-mediated cycloisomerization of o-alkynyl benzaldehydes.6a More recently, he provided enantioselective access to several azaphilones using stoichiometric copper, O2, and (−)-sparteine and has applied the method in the synthesis of the azaphilone (−)-S-15183A.7 However, the gold-mediated cyclization and subsequent copper-mediated enantioselective oxidation may not be amenable to derivatives containing an acrylate or disubstituted olefin, such as that found in the mitorubrins.

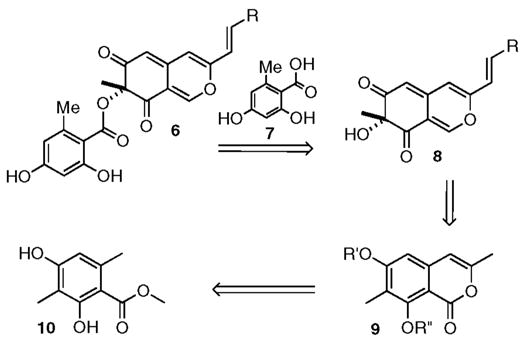

Therefore, we set out to devise a racemic route to the mitorubrins, which might be eventually adapted to our enantioselective dearomatization protocol.8 The fully elaborated skeleton 6 of the mitorubrins arises upon attaching orsellinic acid 7 to the 3° alcohol of 8 (Scheme 1).9 We imagined that the azaphilone core 8, in turn, could arise from the isocoumarin 9. Recognizing that an analogue of isocoumarin 9 had been produced by Staunton’s orsellenate enolization protocol some time ago,10 we chose the methyl benzoate 10 as our starting material.

Scheme 1.

General Synthetic Strategy to Address the Mitorubrins

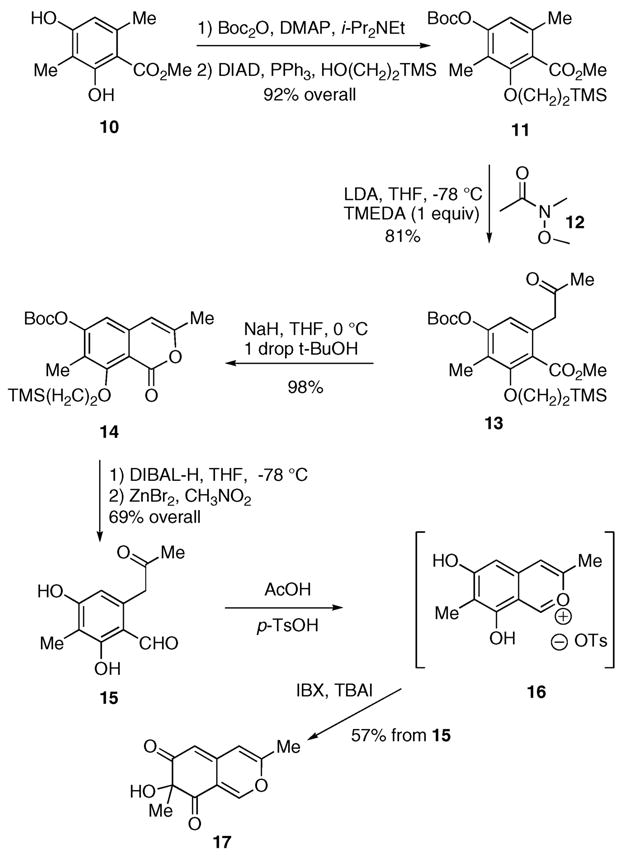

Our synthesis begins with mono-phenol protection using di-tert-butyl dicarbonate, N-ethyldiisopropylamine (DIPEA), and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP). Coupling of the more congested phenol proceeds with 2-(trimethylsilyl)-ethanol under Mitsunobu’s conditions. This two-pot sequence affords the differentially protected ester 11 in 92% overall yield (Scheme 2). Addition of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) results in γ-deprotonation and formation of the corresponding dienic enolate, which resembles a dimethide.10 However, a slight amendment to Staunton’s conditions proved necessary. Introduction of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine prior to the Weinreb acetamide 12 provides the keto ester 13 in 81% yield, whereas yields were 40–50% in its absence. Addition of base promotes enolization and cyclization of 13 to afford the isocoumarin 14 in 98% yield. The four-step sequence from 10 to 14 can easily be carried out on multigram scale.

Scheme 2.

A Concise Route to the Azaphilone Core

Selective reduction of the isocoumarin carbonyl moiety in 14 with 1.05 equiv of diisobutylaluminum hydride (DIBAL-H) in tetrahydrofuran followed by global deprotection of the O-tert-butyl carbonate and O-(CH2)2TMS ethers with zinc bromide in nitromethane provides the keto aldehyde 15 in 69% overall yield. The 2-benzopyrylium salt 16 forms upon addition of acetic acid and p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TsOH) to the keto aldehyde 15.11 After concentration and evaporation of the solvent, the salt 16 is re-dissolved in 1,2-dichloroethane and stirred with o-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) and a catalytic amount of tetra-n-butylammonium iodide (TBAI) to afford the azaphilone 17 in 57% yield. The delivery of a hydroxy residue ortho to both phenols was expected based on our earlier work with IBX.12 However, an important modification, addition of TBAI as reported by Porco, proved critical for this nucleus.6

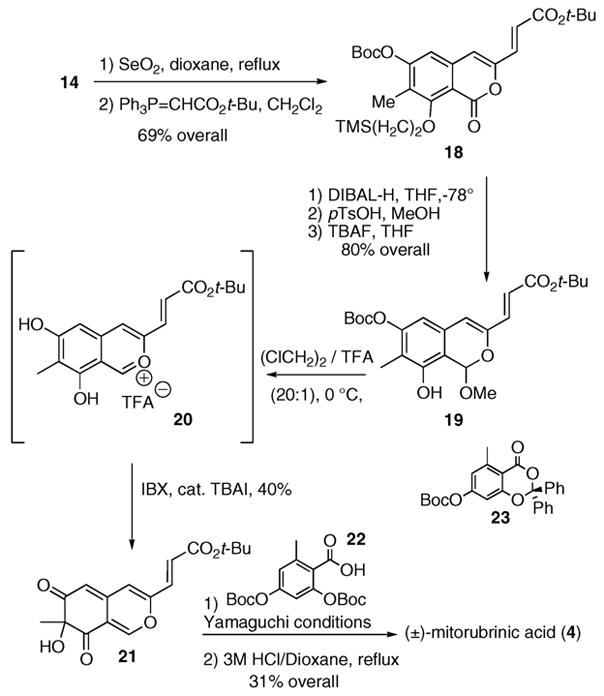

Having satisfactorily tested the dearomatization protocol, we began the synthesis of (±)-mitorubrinic acid (4) in earnest. Starting from isocoumarin 14, allylic oxidation with selenium dioxide in anhydrous dioxane affords the corresponding 3-formyl isocoumarin intermediate.13 Homologation using (t-butoxycarbonylmethylene)triphenylphosphorane in methylene chloride gives a 69% overall yield of E-tert-butyl ester 18, along with a small amount of its corresponding Z-isomer that is easily removed by chromatography. DIBAL-H in THF selectively reduces the lactone moiety, and the tert-butyl ester emerges unscathed. Addition of acidic methanol to the hemiketal intermediate followed by desilylation with tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride (TBAF) yields the mono-O-Boc phenol 19 in 80% over the three steps. Because of a problematic selective O-Boc cleavage in the presence of the tert-butyl ester, we decided to oxidize 19. Given our previous finding shown in Scheme 2, the oxidative dearomatization of 19 proved surprisingly difficult. This problem stems from competitive tert-butylation of the azaphilone by acidic cleavage of the O-Boc moiety. After considerable experimentation, we find that the ketal 19 converts to the benzopyrylium salt 20 when dissolved in a 20:1 mixture of 1,2-dichloroethane and trifluoroacetic acid at 0 °C. Upon subsequent exposure to IBX/TBAI,6a,12 the azaphilone 21 is produced in a modest yet reproducible 40% yield. The azaphilone 23 also directly arises from reaction of ketal 19 with iodosylbenzene and Lewis acids, such as trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate or BF3•OEt2. However, these conditions prove capricious (5–54%) and in some instances result in accompanying tert-butylation of the azaphilone nucleus.

Nevertheless, with a modest amount of the fully functionalized azaphilone core in hand, our attentions turned toward esterification. Several protocols were examined. Most conditions failed in our hands. In particular, photolysis of 21 with an orsellenatederived benzodioxin (23) using De Brabander’s14 protocol proved ineffective due to decomposition of the azaphilone. However, Yamaguchi’s lactonization conditions using 2,4,6-trichlorobenzoyl chloride, acid 22, and NEt3 produces the desired ester in a 35% yield.15 Subsequent global cleavage of the tert-butyl ester and tert-butyl carbonates proceeds with 3 M HCl in refluxing dioxane over 4 h to afford (±)-mitorubrinic acid (4) in a 31% yield over the two steps.

In conclusion, the first total synthesis of (±)-mitorubrinic acid (4) has been completed. The target is obtained in 12 steps in 5% overall yield. The core 21 is accessible in 16% yield after 10 steps. Although the congested esterification with the acid 22 needs further optimization (35% yield), the final deprotection proceeds in nearly quantitative fashion. We are currently examining the intramolecular cycloaddition of the symmetric anhydride derived from 4 to address diazaphilonic acid (5), as well as an enantioselective synthesis of (−)-4. Our findings will be reported shortly.

Scheme 3.

Completion of (±)-Mitorubrinic Acid (4)

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for financial support provided by the NIH GM-64831 and U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command (M.A.M.) (DAMD17-02-1-0334). M.A.M. thanks the University of California at Santa Barbara for a Graduate Mentor Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Full experimental details and compound characterization (1H NMR, 13C NMR, HRMS, FT-IR). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Suzuki S, Hosoe T, Nozawa K, Yaguchi T, Udagawa S, Kawai K. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1328. doi: 10.1021/np990146f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Natsume M, Takahashi Y, Marumo S. Agric Biol Chem. 1985;49:2517. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Büchi G, White JD, Wogan GN. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:3484. doi: 10.1021/ja01093a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Steyn PS, Vleggaar R. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1975:204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Locci R, Merlini L, Nasini G, Locci JR. Giornale di Microbiologia. 1967;15:93. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lesova K, Sturdikova M, Rosenberg M. J Basic Microbiol. 2000;40:365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Steglich W, Klaar M, Furtner W. Phytochemistry. 1984;18:2874. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Tabata Y, Ikegami S, Yaguchi T, Sasaki T, Hoshiko S, Sakuma S, Shin-Ya K, Seto H. J Antibiot. 1999;52:412. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.52.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oikawa H, Tokiwano T. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21:321. doi: 10.1039/b305068h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whalley WB, Chong R, Gray RW, King RR. J Chem Soc C. 1971:3571. doi: 10.1039/j39710003571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zhu J, Germain AR, Porco JA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:1239. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Stark LM, Pekari K, Sorensen EJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402563101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu J, Grigoriadis NP, Lee JP, Porco JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9342. doi: 10.1021/ja052049g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mejorado L, Hoarau C, Pettus TRR. Org Lett. 2004;6:1535. doi: 10.1021/ol0498592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solladie G, Rubio A, Carreño MC, Ruano JLG. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1990;3:187. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis CN, Spargo PL, Staunton J. Synthesis. 1986:944. [Google Scholar]

- 11.For acid-catalyzed formation of benzopyrylium salts, see: Wei W, Yao Z. J Org Chem. 2005;70:4585. doi: 10.1021/jo050414g.Suzuki T, Okada C, Arai K, Awaji A, Shimizu T, Tanemura K, Horaguchi T. J Heterocycl Chem. 2001;38:1409.Selenski CS, Pettus TRR. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:5298. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.01.109.

- 12.Magzdiak D, Rodriguez AA, Van de Water RV, Pettus TRR. Org Lett. 2002;4:285. doi: 10.1021/ol017068j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modi AR, Nadkarni DR, Usgaonkar RN. Ind J Chem. 1979;17B:624. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soltani O, De Brabander J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;177:1724. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1979;52:1989. [Google Scholar]