Abstract

IGF-1 has been shown to promote proliferation of normal epithelial breast cells, and the IGF pathway has also been linked to mammary carcinogenesis in animal models. We comprehensively examined the association between common genetic variation in the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 genes in relation to circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels and breast cancer risk within the NCI Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3). This analysis included 6,912 breast cancer cases and 8,891 matched controls (n = 6,410 for circulating IGF-I and 6,275 for circulating IGFBP-3 analyses) comprised primarily of Caucasian women drawn from six large cohorts. Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype patterns were characterized in the regions surrounding IGF1 and the genes coding for two of its binding proteins, IGFBP1 and IGFBP3. In total, thirty haplotype-tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (htSNP) were selected to provide high coverage of common haplotypes; the haplotype structure was defined across four haplotype blocks for IGF1 and three for IGFBP1 and IGFBP3. Specific IGF1 SNPs individually accounted for up to 5% change in circulating IGF-I levels and individual IGFBP3 SNPs were associated up to 12% change in circulating IGFBP-3 levels, but no associations were observed between these polymorphisms and breast cancer risk. Logistic regression analyses found no associations between breast cancer and any htSNPs or haplotypes in IGF1, IGFBP1, or IGFBP3. No effect modification was observed in analyses stratified by menopausal status, family history of breast cancer, body mass index, or postmenopausal hormone therapy, or for analyses stratified by stage at diagnosis or hormone receptor status. In summary, the impact of genetic variation in IGF1 and IGFBP3 on circulating IGF levels does not appear to substantially influence breast cancer risk substantially among primarily Caucasian postmenopausal women.

Introduction

The insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) signaling pathway stimulates cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis [1], [2]. The bioavailability of IGF-I in circulation and tissues is determined by the amount of free ligand that circulates unattached to binding protein. There are six IGF binding proteins. Approximately 75–90% of IGF-I binds to IGFBP-3, limiting its bioavailability. IGFBP-1 also modulates IGF-I bioavailability, and is inversely regulated by insulin [3]. IGF-I has been shown to promote proliferation of normal epithelial breast cells [1], [2], [4]. The IGF pathway has been linked to mammary carcinogenesis in animal models [5], and consequently, it has been extensively examined in relation to breast cancer pathogenesis.

Previous epidemiologic studies have suggested that high circulating levels of IGF-I and low levels of IGFBP-3 are associated with increased risk of premenopausal breast cancer [6], [7]. Numerous recent epidemiologic studies (reviewed in [6]) have begun to examine variation in the genes encoding IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 in relation to breast cancer risk. The most extensively examined polymorphisms in IGF1 has been the 5′ simple tandem repeat that lies 1-kb upstream from the IGF1 gene transcription start site (the most common allele in Caucasians is the 19 CA repeat) and an A/C polymorphism 5′ to IGFBP3 at nucleotide −202 (rs2854744) [6]. Some studies report that these or other IGF polymorphisms modestly affect circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 [6], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], but there is limited support for a direct effect on breast cancer risk. Most recently, comprehensive analyses of common genetic variation across the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 genes were conducted in two prospective cohorts [8], [9], [11], but no association with breast cancer risk was observed.

To comprehensively examine the role of common genetic variation in the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 genes in relation to circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels and breast cancer risk, we conducted a haplotype-based analysis in the NCI Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3) [13]. The large size of this study (cases = 6,912/controls = 8,891) enabled us to detect modest genetic effects, explore gene-environment interactions, and examine potentially important subclasses of tumors, such as those defined by stage or hormone receptor status.

Methods

Study Population

The BPC3 has been described in detail elsewhere [13]. Briefly, the consortium includes large well-established cohorts assembled in the United States or Europe that have DNA for genotyping and extensive questionnaire data from cohort members. This analysis includes 6,912 cases of invasive breast cancer and 8,891 matched controls from six cohorts: the American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study-II (CPS-II; [14]), the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort [15], the Harvard Nurses' Health Study (NHS; [16]), the Harvard Women's Health Study (WHS; [17]), the Hawaii-Los Angeles Multiethnic Cohort Study (MEC; [18]), and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial cohort (PLCO; [19]). With the exception of MEC, most women in these studies are Caucasian. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and each cohort has been approved by the following institutional review boards: Emory University (CPS-II), International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and each EPIC recruitment center (EPIC), Harvard University (NHS and WHS), University of Hawaii and University of Southern California (MEC), and the U.S. National Cancer Institute and the 10 study screening centers (PLCO).

Cases were initially identified in each cohort by self-report and subsequently verified from medical records or tumor registries and/or linkage with population-based cancer registries. In all cohorts, questionnaire data were collected prospectively before the cancer diagnosis. Controls were matched to cases by age, ethnicity (except in PLCO), and in some cohorts additional matching criteria were utilized (e.g. date of blood draw).

SNP Selection and Genotyping

The details of IGF1, IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 characterization and selection of haplotype-tagging SNPs (htSNPs) have been described elsewhere [9], [20]. Briefly, coding regions of IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 were sequenced in a panel of 95 advanced breast cancer cases from the MEC (19 from each of the five ethnic groups; African American, Latina, Japanese, Native Hawaiian, and Caucasian). SNPs were also selected from public databases to capture the genetic diversity of regions from ∼20 kb upstream to ∼10 kb downstream of each gene. Haplotype blocks (regions of strong linkage disequilibrium) were defined using the method of Gabriel et al. [21]. Haplotype tagging SNPs (htSNPs) were selected to predict the common haplotypes among Caucasians that meet a criterion of rh 2>0.80.

For genetic characterization of IGF1, 154 SNPs were genotyped a multiethnic panel of 349 individuals with no history of cancer (18). Of the 154 SNPs genotyped, 53 were identified as monomorphic and 37 had poor genotyping results (i.e., genotyped ≤75% of samples or out of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium [one-sided P<.01] in more than one ethnic group)—these 90 SNPs were eliminated from further analysis. The remaining 64 SNPs were used for genetic characterization and had an average density of one SNP for every 2.4 kb over a 156-kb region. Fourteen htSNPs were selected using the expectation-maximization algorithm [22] to predict the common haplotypes among Caucasians (rh 2>0.85). For genetic characterization of IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 (which are located contiguously in a 35kb region of chromosome 7), 56 SNPs were genotyped in the multiethnic panel (18). Of the 56 SNPs genotyped, 17 were identified as monomorphic and 3 had poor genotyping results (as discussed above)—these 20 SNPs were eliminated from analysis. The remaining 36 SNPs were used for genetic characterization, having an average density of one SNP for every 2 kb over a 71-kb region. Twelve htSNPs were selected to predict the common haplotypes among Caucasians (rh 2>0.99). Additionally, two genic SNPs in IGFBP3 that were not part of a haplotype block were examined (rs6670, rs2453839), and two additional IGFBP3 SNPs (rs2132570, and rs2960436) were included. Thus, a total of 16 SNPs across IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 were evaluated. Genotyping of breast cancer cases and controls was performed in four laboratories (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA USA, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA USA, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, National Cancer Institute Core Genotyping Facility, Gaithersburg, MD USA) using a fluorescent 5′ endonuclease assay and the ABI-PRISM 7900 for sequence detection (Taqman). Initial quality control checks of the SNP assays were done at the manufacturer (ABI, Foster City, CA); an additional 500 test reactions were run by the BPC3. Assay characteristics for the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 htSNPs are available on a public website (http://www.uscnorris.com/mecgenetics/CohortGCKView.aspx). To assess interlaboratory variation, each genotyping center ran assays on a designated set of 94 samples from the Coriell Biorepository (Camden, NJ) (22). The completion and concordance rates were each >99%[23]. The internal quality of genotype data at each genotyping center was assessed by typing 5–10% blinded samples in duplicate or greater, depending on study.

IGF-I and IGFBP-3 Measurements

IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays among non-users of postmenopausal hormones (and non-users of oral contraceptives in EPIC). Detailed laboratory methods for these studies have been previously reported [24], [25], [26]. Blood samples analyzed in this study include all cohorts with the exception of the CPS-II and WHS cohorts, where most specimens were collected after diagnosis (CPS-II) or hormone assays were not performed (WHS). Thus, these analyses included 6,410 women for IGF-I and 6,275 women for IGFBP-3.

Statistical Analysis

In our hormone analyses, circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 values were naturally log-transformed to provide approximate normal distributions. Geometric mean levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 for IGF1 and IGFBP3 SNPs were calculated using linear regression analysis while adjusting for age at blood draw, assay laboratory and batch for circulating IGFs, BMI, race/ethnicity, and country within EPIC cohort. Additional regression analyses were conducted simultaneously adjusted for all other IGF1 and IGFBP SNPs to determine the best fit model of circulating levels.

In our breast cancer analysis, we examined both single SNP and haplotype effects on breast cancer risk. For single SNP analyses, we used conditional multivariate logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for breast cancer using a linear (log-odds additive) scoring for 0, 1 or 2 copies of the minor allele of each SNP. For the haplotype analyses, we calculated haplotype frequencies and subject-specific expected haplotype counts separately for each cohort, by country within EPIC, and by ethnicity within the MEC. An expectation-substitution approach was used to assign expected haplotype counts based on unphased genotype data and to account for uncertainty in assignment [27]. The most common haplotype was used as the referent group. Rare haplotypes (those with estimated individual frequencies <5%) were combined into a single category.

To test the global null hypothesis of no association between variation in IGF1, IGFBP1, or IGFBP3 haplotypes and risk of breast cancer (or subtypes defined by receptor status), we used a likelihood ratio test comparing a model with additive effects for each common haplotype (treating the most common haplotype as the referent) to the intercept-only model. To test for heterogeneity across cohorts and ethnic groups, we used the Wald X 2 for the htSNPs and a likelihood ratio test for the haplotypes.

We considered conditional models both without and with adjustment for known breast cancer risk factors. These included menopausal status (premenopausal, postmenopausal), age at menopause (<50, 50+, age unknown), BMI (<25, 25-<30, 30+, missing), parity (ever, never, missing), use of postmenopausal hormones (ever, never, missing), first-degree family history of breast cancer (yes, no, unknown), age at menarche (<13, 13–14, 15+, missing), and use of oral contraceptives (ever, never, missing). Because results remained virtually unchanged regardless of the model used, we present results from the conditional models adjusting for matching factors only. We also evaluated BMI, family history of breast cancer, and use of postmenopausal hormones for possible interaction effects using likelihood ratio testing (LRT). Models with the main effect of genotype and the covariate of interest were compared to models with the main effects of genotype and the covariate of interest, plus a multiplicative interaction term of the two variables. We also examined whether the associations between IGF1, IGFBP1, or IGFBP3 htSNPs or haplotypes and breast cancer differed by menopausal status (pre- versus post-menopausal), stage (in situ versus localized versus regional or distant metastasis) or hormone receptor (ER and PR) status.

Lastly, this analysis includes a portion of the previously published data from the MEC [9], [11] and EPIC [8] cohorts (n = 2,522 breast cancer cases). Thus, all associations were examined in sub-analyses that excluded the MEC and EPIC cohort participants.

Results

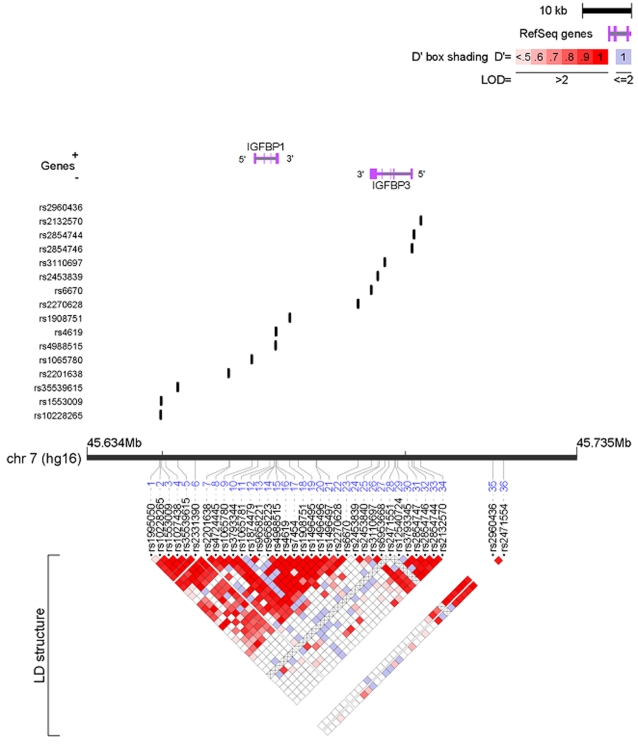

The genomic structure of IGF1 is shown in Fig. 1 and that of IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 is shown in Fig. 2. The IGF1 locus was characterized into four haplotype blocks. IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 loci are 19kb apart and were characterized by three haplotype blocks. The genotyping success rate was ≥95% for all SNPs at each genotyping center. No deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was observed among the controls overall (at the p<0.01 level). The frequencies of individual SNPs and common haplotypes within each LD block were consistent across all cohorts (data not shown).

Figure 1. IGF1 SNPs and linkage disequilibrium.

64 SNPs were identified covering a 56-kb region. Of these, 14 htSNPs defined the common haplotypes among Caucasians.

Figure 2. IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 SNPs and linkage disequilibrium.

36 SNPs were identified covering a 71-kb region. Of these, 12 htSNPs defined the common haplotypes among Caucasians.

Study characteristics of each cohort (except PLCO) have been published previously [28]. Briefly, case and control characteristics were comparable across all cohorts and most women were postmenopausal (n = 5,474 cases and 9,732 controls) and Caucasian. As there was no heterogeneity in results across cohorts for any main effects analyses, we only reported results from pooled analyses across all cohorts combined. Additionally, haplotype analyses did not contribute additional information beyond individual SNP results, thus we reported only results for all individual SNPs within each haplotype block.

SNPs in IGF1 (Table 1) and IGFBP3 (Table 2) were associated with circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels, respectively, in women not taking postmenopausal hormones. SNPs in IGF1 block 1 were most closely associated with circulating levels; the variant alleles were significantly associated with higher circulating IGF-I levels (trend p = 0.0075 for rs7965399 and p = 0.0262 for rs35767). However, these SNPs (wild type vs. variant homozygote) individually accounted for less than a 5% change in mean IGF-I levels. Results did not differ after simultaneously adjusting for all other IGF1 and IGFBP SNPs in the regression analysis (data not shown). The strongest relationships for IGFBP-3 were observed with five SNPs in IGFBP3 block 3: rs3110697, rs2854746, rs2854744, rs2132570, rs2960436 (trend p<0.001 for all). Rs2854746 remained significantly associated with IGFBP-3 levels (p<0.0001) after adjusting for all other IGF1 and IGFBP SNPs simultaneously in the regression analysis. These SNP associations account for a change in mean circulating IGFBP-3 levels ranging from 6% (rs2132570) to 12% (rs2854746).

Table 1. Associations between IGF1 SNPs and mean circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels in the BPC3.

| SNP (position) | Genotype | N (n = 6,410) | mean IGF1 diff | p-trend | % change | N (n = 6,410) | mean IGFBP-3 diff | p-trend | % change |

| Block 1 | |||||||||

| rs7965399 | TT | 5620 | 26.8 | 0 | 5495 | 122.1 | 0 | ||

| (101394153) | TC | 530 | 28.0 | 0.008 | 4.4 | 522 | 119.9 | 0.075 | −1.8 |

| CC | 41 | 28.1 | 4.8 | 41 | 112.7 | −8.3 | |||

| rs35767 | GG | 4184 | 26.9 | 0 | 4100 | 121.5 | 0 | ||

| (101378036) | GA | 1704 | 27.4 | 0.026 | 1.8 | 1662 | 120.6 | 0.049 | −0.7 |

| AA | 209 | 27.9 | 3.7 | 205 | 115.3 | −5.4 | |||

| Block 2 | |||||||||

| rs12821878 | GG | 3830 | 27.1 | 0 | 3751 | 121.6 | 0 | ||

| (101370134) | GA | 2039 | 26.8 | 0.187 | −1.3 | 1993 | 122.1 | 0.164 | 0.4 |

| AA | 326 | 26.8 | −1.3 | 317 | 125.2 | 3 | |||

| rs1019731 | CC | 4826 | 27.2 | 0 | 4718 | 121.5 | 0 | ||

| (101366892) | CA | 1312 | 27.1 | 0.915 | −0.5 | 1288 | 121.4 | 0.856 | −0.1 |

| AA | 103 | 28.1 | 3.3 | 101 | 123.5 | 1.6 | |||

| rs2195239 | CC | 3754 | 26.8 | 0 | 3673 | 121.3 | 0 | ||

| 101359169 | CG | 2182 | 27.4 | 0.028 | 2.3 | 2134 | 121.3 | 0.932 | 0 |

| GG | 330 | 27.2 | 1.7 | 326 | 121.2 | 0 | |||

| Block 3 | |||||||||

| rs10735380 | AA | 3397 | 26.8 | 0 | 3327 | 122.1 | 0 | ||

| (101346703) | AG | 2363 | 27.5 | 0.042 | 2.5 | 2310 | 121.5 | 0.847 | −0.5 |

| GG | 454 | 27.1 | 1 | 444 | 122.6 | 0.4 | |||

| rs2373722 | GG | 5405 | 27.1 | 0 | 5292 | 121.9 | 0 | ||

| (101342924) | GA | 809 | 27.8 | 0.071 | 2.4 | 787 | 120 | 0.256 | −1.6 |

| AA | 41 | 27.7 | 2 | 42 | 122.5 | 0.5 | |||

| rs5742665 | CC | 4690 | 27.1 | 0 | 4601 | 121.6 | 0 | ||

| (101326017) | CG | 1394 | 27.3 | 0.288 | 0.8 | 1355 | 121.1 | 0.532 | −0.4 |

| GG | 120 | 27.9 | 3.1 | 113 | 119.8 | −1.5 | |||

| rs1549593 | GG | 4703 | 27.0 | 0 | 4598 | 121.2 | 0 | ||

| (101299258) | GT | 1350 | 26.8 | 0.754 | −0.8 | 1325 | 122.7 | 0.541 | 1.2 |

| TT | 99 | 27.7 | 2.5 | 95 | 117.4 | −3.2 | |||

| rs1520220 | CC | 4068 | 26.8 | 0 | 3976 | 122.4 | 0 | ||

| (101298989) | CG | 1902 | 27.7 | 0.007 | 3.1 | 1868 | 121 | 0.157 | −1.2 |

| GG | 253 | 27.2 | 1.3 | 249 | 120.5 | −1.6 | |||

| Block 4 | |||||||||

| rs2946834 | GG | 2771 | 26.5 | 0 | 2714 | 122.7 | 0 | ||

| (101290281) | GA | 2716 | 27.4 | 0.007 | 3.2 | 2658 | 121 | 0.076 | −1.4 |

| AA | 704 | 27.1 | 2.2 | 685 | 120.5 | −1.8 | |||

| rs4764876 | GG | 3259 | 26.9 | 0 | 3187 | 121.5 | 0 | ||

| (101261169) | GC | 2460 | 27.2 | 0.218 | 1.2 | 2408 | 121.1 | 0.812 | −0.3 |

| CC | 461 | 27.1 | 1.1 | 451 | 121.4 | −0.1 | |||

| rs4764695 | GG | 1592 | 27.3 | 0 | 1559 | 121.9 | 0 | ||

| (101259580) | GA | 3122 | 27.1 | 0.190 | −0.9 | 3049 | 121.2 | 0.875 | 0.6 |

| AA | 1529 | 26.9 | −1.6 | 1500 | 122.2 | 0.2 | |||

| rs1996656 | AA | 4307 | 27.00 | 0 | 4215 | 120.5 | 0 | ||

| (101254429) | AG | 1718 | 27.2 | 0.605 | 0.8 | 1678 | 120.9 | 0.882 | 0.3 |

| GG | 185 | 26.9 | −0.3 | 182 | 119.9 | −0.5 |

Table 2. Associations between IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 SNPs and mean circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels in the BPC3.

| SNP | Genotype | N (n = 6,275) | mean IGF1 diff | p-trend | % change | N (n = 6,275) | mean IGFBP-3 diff | p-trend | % change |

| Block 1 | |||||||||

| rs10228265 | AA | 3035 | 26.9 | 0 | 2981 | 122.5 | 0 | ||

| (45649695) | AG | 2654 | 27.3 | 1.4 | 2587 | 121 | −1.2 | ||

| GG | 599 | 27.3 | 0.108 | 1.7 | 585 | 120.3 | 0.083 | −1.8 | |

| rs1553009 | GG | 4061 | 27.1 | 0 | 3976 | 121.5 | 0 | ||

| (45649774) | GA | 1998 | 27.6 | 2 | 1953 | 122.1 | 0.5 | ||

| AA | 235 | 26.5 | 0.285 | −2 | 232 | 124.4 | 0.270 | 2.4 | |

| rs35539615 | CC | 3640 | 27.2 | 0 | 3560 | 121.4 | 0 | ||

| (45653244) | CG | 2269 | 27.1 | −0.2 | 2223 | 121 | −0.3 | ||

| GG | 327 | 27.3 | 0.995 | 0.6 | 319 | 121.5 | 0.788 | 0.1 | |

| rs2201638 | GG | 5854 | 27.2 | 0 | 5729 | 122.1 | 0 | ||

| (45663690) | GA | 413 | 27.6 | 1.7 | 404 | 120.2 | −1.6 | ||

| AA | 17 | 27.7 | 0.349 | 2 | 17 | 113.1 | 0.209 | −8 | |

| rs1065780 | GG | 2358 | 27.0 | 0 | 2309 | 122 | 0 | ||

| (45668457) | GA | 2966 | 27.3 | 1.1 | 2902 | 121.8 | −0.2 | ||

| AA | 923 | 27.3 | 0.262 | 1.1 | 903 | 121.2 | 0.663 | −0.7 | |

| Block 2 | |||||||||

| rs4988515 | CC | 5753 | 27.1 | 0 | 5625 | 121.7 | 0 | ||

| (45673380) | CT | 522 | 27.2 | 0.5 | 515 | 121.1 | −0.5 | ||

| TT | 19 | 26.1 | 0.909 | −3.8 | 19 | 113.9 | 0.532 | −6.8 | |

| rs4619 | AA | 2662 | 27.0 | 0 | 2608 | 122.3 | 0 | ||

| (45673449) | AG | 2839 | 27.2 | 0.5 | 2774 | 121.3 | −0.8 | ||

| GG | 735 | 27.5 | 0.243 | 1.8 | 719 | 122 | 0.543 | −0.2 | |

| rs1908751 | CC | 3113 | 27.2 | 0 | 3047 | 122.2 | 0 | ||

| (45676299) | CT | 2586 | 27.0 | −0.7 | 2526 | 120.6 | −1.3 | ||

| TT | 560 | 27.1 | 0.568 | −0.3 | 552 | 122.6 | 0.486 | 0.3 | |

| rs2270628 | CC | 4121 | 27.3 | 0 | 4038 | 122.8 | 0 | ||

| (45690350) | CT | 1850 | 27.1 | −0.6 | 1804 | 120.1 | −2.2 | ||

| TT | 239 | 27.1 | 0.543 | −0.7 | 234 | 116.4 | 0.001 | −5.5 | |

| Block 3 | |||||||||

| rs3110697 | GG | 2203 | 27.4 | 0 | 2145 | 125.4 | 0 | ||

| (45695809) | GA | 2929 | 27.1 | −1.1 | 2877 | 122.2 | −2.6 | ||

| AA | 1083 | 27.9 | 0.392 | 1.8 | 1059 | 115.2 | <0.0001 | −8.9 | |

| rs2854746 | GG | 2010 | 27.3 | 0 | 1970 | 114.7 | 0 | ||

| (45701425) | GC | 2950 | 27.00 | −0.9 | 2884 | 123 | 7.2 | ||

| CC | 1168 | 27.2 | 0.741 | −0.1 | 1139 | 128.5 | <0.0001 | 12 | |

| rs2854744 | GG | 1586 | 27.6 | 0 | 1550 | 115.6 | 0 | ||

| (45701855) | GT | 3226 | 27.1 | −2.1 | 3169 | 121.5 | 5.1 | ||

| TT | 1427 | 27.6 | 0.745 | −0.3 | 1388 | 127.7 | <0.0001 | 10.5 | |

| Additional SNPs | |||||||||

| rs6670 | TT | 3841 | 27.3 | 0 | 3764 | 121.6 | 0 | ||

| (45693034) | TA | 2146 | 26.8 | −2.1 | 2091 | 120.1 | −1.2 | ||

| AA | 278 | 26.6 | 0.022 | −2.8 | 275 | 125.2 | 0.935 | 3 | |

| rs2453839 | TT | 4046 | 27.3 | 0 | 3964 | 122.3 | 0 | ||

| (45694353) | TC | 1961 | 27.2 | −0.5 | 1917 | 121 | −1.1 | ||

| CC | 250 | 27.5 | 0.901 | 0.9 | 242 | 121.4 | 0.264 | −0.7 | |

| rs2132570 | GG | 3948 | 27.1 | 0 | 2855 | 122.4 | 0 | ||

| (45703243) | GT | 1972 | 27.1 | −0.2 | 1933 | 118.9 | −2.9 | ||

| TT | 291 | 27.5 | 0.812 | 1.3 | 289 | 115.3 | <0.0001 | −6.2 | |

| rs2960436 | GG | 1645 | 27.6 | 0 | 1607 | 115 | 0 | ||

| (45718062) | GA | 3074 | 27.1 | −1.7 | 3021 | 122.5 | 6.5 | ||

| AA | 1547 | 27.3 | 0.431 | −0.9 | 1506 | 127.2 | <0.0001 | 10.6 |

None of the IGF1 and IGFBP3 SNPs associated with circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels were significantly associated with breast cancer risk (Tables 3 and 4 for IGF1 and IGFBP1/3, respectively), nor were other SNPs or haplotypes consistently associated with risk. When examining these associations among invasive breast cancer only, by stage, or by hormone-receptor status, we did not observe any associations between variation in these genes and disease risk (data not shown). Results did not differ when examining associations separately for pre- and post-menopausal women or when restricting the analysis to only white women (data not shown). No consistent interactions were observed among variants in the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 genes with any of the following: first-degree family history of breast cancer, ever oral contraceptive use, use of postmenopausal hormones, and BMI (<25, 25-<30, 30+). We observed no interactions resulting in sub-group associations with disease risk (data not shown).

Table 3. Association of tagging SNPs of IGF1 and breast cancer risk in the BPC3.

| SNP | Genotype | Cases (n = 6,912) | Controls (n = 8,891) | OR* (95% CI) | p-trend |

| Block 1 | |||||

| rs7965399 | TT | 5668 | 7214 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| TC | 825 | 1095 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | ||

| CC | 76 | 105 | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | 0.12 | |

| rs35767 | GG | 4230 | 5359 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 1876 | 2468 | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | ||

| AA | 251 | 378 | 0.87 (0.76–1.01) | 0.06 | |

| TG | 5317 | 6767 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| TA | 855 | 1148 | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | ||

| CG | 100 | 129 | 1.00 (0.84–1.20) | ||

| CA | 390 | 531 | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 0.20 | |

| Block 2 | |||||

| rs12821878 | GG | 4073 | 5343 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 2090 | 2544 | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | ||

| AA | 299 | 400 | 0.98 (0.85–1.12) | 0.38 | |

| rs1019731 | CC | 5092 | 6639 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CA | 1404 | 1688 | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | ||

| AA | 97 | 145 | 0.87 (0.68–1.10) | 0.57 | |

| rs2195239 | CC | 3699 | 4819 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CG | 2440 | 3121 | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | ||

| GG | 434 | 532 | 1.03 (0.91–1.15) | 0.83 | |

| GCC | 3582 | 4691 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| GCG | 1671 | 2121 | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | ||

| ACC | 799 | 983 | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | ||

| AAC | 594 | 757 | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) | ||

| Haplotype Freq <5% | 16 | 22 | 0.99 (0.61–1.62) | 0.93 | |

| Block 3 | |||||

| rs10735380 | AA | 3658 | 4716 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| AG | 2502 | 3088 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | ||

| GG | 425 | 595 | 0.93 (0.83–1.05) | 0.92 | |

| rs2373722 | GG | 5845 | 7475 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 757 | 978 | 1.00 (0.92–1.10) | ||

| AA | 26 | 47 | 0.82 (0.52–1.30) | 0.82 | |

| rs5742665 | CC | 5133 | 6566 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CG | 1282 | 1674 | 1.01 (0.94–1.09) | ||

| GG | 107 | 131 | 1.12 (0.89–1.42) | 0.52 | |

| rs1549593 | GG | 4994 | 6455 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GT | 1416 | 1734 | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | ||

| TT | 114 | 146 | 0.98 (0.78–1.22) | 0.57 | |

| rs1520220 | CC | 4048 | 5277 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CG | 2207 | 2707 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | ||

| GG | 329 | 440 | 0.96 (0.85–1.10) | 0.73 | |

| AGCGC | 3171 | 4127 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| AGCGG | 322 | 395 | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | ||

| AGCTC | 697 | 858 | 1.04 (0.96–1.12) | ||

| AGGGC | 766 | 991 | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | ||

| GGCGC | 434 | 574 | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | ||

| GGCGG | 719 | 893 | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | ||

| GACGG | 406 | 541 | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | ||

| Haplotype Freq <5% | 147 | 196 | 0.93 (0.79–1.09) | 0.88 | |

| Block 4 | |||||

| rs2946834 | GG | 2857 | 3673 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 2898 | 3705 | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | ||

| AA | 845 | 1054 | 1.03 (0.94–1.12) | 0.61 | |

| rs4764876 | GG | 3315 | 4230 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GC | 2560 | 3395 | 0.97 (0.92–1.04) | ||

| CC | 643 | 739 | 1.08 (0.98–1.20) | 0.47 | |

| rs4764695 | GG | 1832 | 2373 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 3188 | 4087 | 1.02 (0.95–1.09) | ||

| AA | 1541 | 1977 | 1.01 (0.93–1.09) | 0.81 | |

| rs1996656 | AA | 4512 | 5753 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| AG | 1773 | 2320 | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | ||

| GG | 199 | 241 | 1.04 (0.88–1.23) | 0.72 | |

| GGAA | 2753 | 3506 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| GGGA | 1006 | 1340 | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | ||

| GGGG | 429 | 567 | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) | ||

| AGAA | 395 | 531 | 0.96 (0.88–1.06) | ||

| ACGA | 1134 | 1411 | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | ||

| ACGG | 666 | 860 | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) | ||

| Haplotype Freq <5% | 279 | 360 | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | 0.75 |

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and country within EPIC cohort.

Table 4. Association of tagging SNPs of IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 and breast cancer risk in the BPC3.

| SNP | Genotype | Cases (n = 6,912) | Controls (n = 8,891) | OR* (95% CI) | p-trend |

| Block 1 | |||||

| rs10228265 | AA | 3112 | 3962 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| AG | 2765 | 3637 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | ||

| GG | 646 | 846 | 0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 0.54 | |

| rs1553009 | GG | 4273 | 5490 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 2046 | 2668 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | ||

| AA | 243 | 336 | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.419 | |

| rs35539615 | CC | 2760 | 4836 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CG | 2298 | 3073 | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | ||

| GG | 389 | 473 | 1.01 (0.90–1.14) | 0.63 | |

| rs2201638 | GG | 6118 | 7831 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 497 | 706 | 0.94 (0.85–1.05) | ||

| AA | 34 | 35 | 1.17 (0.81–1.68) | 0.53 | |

| rs1065780 | GG | 2441 | 3083 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 2999 | 4080 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | ||

| AA | 1055 | 1282 | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 0.812 | |

| AGCGG | 1655 | 2070 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| AGGGG | 1564 | 2045 | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) | ||

| AACGA | 1263 | 1667 | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | ||

| GGCGA | 1267 | 1604 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | ||

| GGCGG | 555 | 748 | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | ||

| GGCAG | 255 | 357 | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | ||

| AGCGA | 52 | 71 | 0.88 (0.69–1.13) | ||

| Haplotype Freq <5% | 112 | 119 | 1.11 (0.94–1.32) | 0.30 | |

| Block 2 | |||||

| rs4988515 | CC | 5933 | 7702 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CT | 627 | 782 | 1.00 (0.91–1.11) | ||

| TT | 27 | 33 | 1.06 (0.69–1.63) | 0.86 | |

| rs4619 | AA | 2706 | 3456 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| AG | 2964 | 3886 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | ||

| GG | 907 | 1122 | 1.01 (0.93–1.11) | 0.94 | |

| rs1908751 | CC | 3238 | 4134 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CT | 2677 | 3518 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | ||

| TT | 593 | 758 | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | 0.57 | |

| rs2270628 | CC | 4198 | 5472 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| CT | 2031 | 2606 | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | ||

| TT | 276 | 629 | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) | 0.93 | |

| CACC | 2274 | 2926 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| CATC | 1907 | 2477 | 0.98 (0.94–1.04) | ||

| CGCC | 1198 | 1566 | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) | ||

| CGCT | 901 | 1143 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | ||

| TGCT | 348 | 434 | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | ||

| Haplotype Freq <5% | 95 | 136 | 0.88 (0.73–1.07) | 0.84 | |

| Block 3 | |||||

| rs3110697 | GG | 2241 | 2919 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 3032 | 3967 | 1.00 (0.94–1.07) | ||

| AA | 1191 | 1491 | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 0.47 | |

| rs2854746 | GG | 2142 | 2759 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GC | 2983 | 3843 | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | ||

| CC | 1208 | 1553 | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | 0.82 | |

| rs2854744 | GG | 1751 | 2190 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GT | 3155 | 4157 | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | ||

| TT | 1581 | 2011 | 0.98 (0.91–1.07) | 0.69 | |

| GCT | 2778 | 3601 | 1.00 (ref.) | ||

| AGG | 2707 | 3464 | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | ||

| GGG | 733 | 948 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | ||

| GGT | 382 | 513 | 0.95 (0.87–1.05) | ||

| Haplotype Freq <5% | 122 | 155 | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 0.80 | |

| Additional SNPs | |||||

| rs6670 | TT | 4210 | 5555 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| TA | 2022 | 2602 | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | ||

| AA | 305 | 356 | 1.12 (0.97–1.30) | 0.05 | |

| rs2453839 | TT | 4301 | 5516 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| TC | 2012 | 2650 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | ||

| CC | 274 | 354 | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | 0.89 | |

| rs2132570 | GG | 3999 | 5182 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GT | 2145 | 2772 | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | ||

| TT | 358 | 441 | 1.01 (0.89–1.15) | 0.99 | |

| rs2960436 | GG | 1795 | 2237 | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| GA | 3127 | 4156 | 0.96 (0.89–1.02) | ||

| AA | 1657 | 2128 | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 0.56 |

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and country within EPIC cohort

Across all statistical tests performed in relation to disease status, we observed fewer significant findings than those expected by chance alone (15 findings significant at p<0.05; 40 expected by chance alone). None of these findings provided clear evidence for main effect or subgroup associations for any of the SNPs or common haplotypes. Thus we believe these sporadic associations may reflect chance. Finally, we repeated all analyses excluding subjects from the MEC and EPIC cohorts, and found no meaningful differences in associations when compared to overall findings (data not shown).

Discussion

Our study is by far the largest to examine genetic variation in the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 genes in relation to both circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels and breast cancer risk. Several genetic variants in IGF1 and IGFBP3 predicted circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3, respectively, but no associations between these variants and breast cancer, overall or in subgroups, were seen. It is thus unlikely that these polymorphisms and their associated hormone levels substantially affect breast cancer risk. There was also no evidence of effect modification by selected breast cancer risk factors or subgroup effects, including menopausal status. While some previous epidemiologic studies have shown stronger support for a role of the IGF-I signaling pathway in premenopausal breast cancer [6], but we did not observe an association among premenopausal women alone.

Our findings are consistent with two previous studies that comprehensively examined the role of IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 genetic variation in relation to circulating IGF-I and IGFBP-3 levels and breast cancer risk [8], [9], [11]. Cases and controls from these two studies (EPIC and MEC) were included in the pooled analysis. However, sensitivity analyses that excluded these studies also found an association with circulating hormone levels. Other studies have primarily examined individual variants in IGF1, IGFBP1, or IGFBP3 in relation to breast cancer with mixed results [6], [29], [30], [31]. The most extensively studied variant in IGF1 is the (CA)n repeat polymorphism that lies 1-kb upstream of the IGF1 transcriptional start site [6], [31]. Some previous studies observed an association between this polymorphism and circulating IGF-I levels (reviewed in [6]); however, most did not observe a corresponding association with breast cancer risk. While we did not genotype IGF1 (CA) n polymorphism, we used data from a prior study [24] and determined that the less common repeat length for this polymorphism is in LD with the minor alleles of htSNPs in block 1, rs7965399 and rs35767. Thus, our reported associations with htSNPs in block 1 and circulating IGF-I levels appear consistent with previous literature, that genetic variation influences circulating IGF-I levels, but not at a level substantial enough to impact breast cancer risk.

The A/C polymorphism at nucleotide −202 in IGFBP3 (rs2854744), and located in haplotype block 3, has been the most extensively examined polymorphism in the IGF binding proteins[6], [8], [9], [29], [30], [31]. Some [6], [29], [30], [31] but not all previous studies [6], [8], [9], [29], [30], [31] have reported an association with breast cancer . This polymorphism has also been associated with circulating levels of IGFBP-3 [26], [30]. Our study confirms the previously reported findings with circulating IGFBP-3 levels, but neither the polymorphism (within Block 3 of IGFBP3 gene) nor the haplotype block were associated with breast cancer risk in our data.

Strengths of the BPC3 include its size and the comprehensive characterization of variation around the IGF1, IGFBP1, and IGFBP3 loci. The latter allows our analysis to provide powerful null evidence against a main effect association between breast cancer risk and variants in these genes that are common among Caucasian women as well as in defined subgroups of the study population.

In summary, results from this large collaborative study support previous evidence that specific genetic variants in IGF1 and IGFBP3 genes significantly influence circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3, respectively, but have no measurable effect on breast cancer risk. Given the large size of our study, it is unlikely that these loci contribute substantially to breast cancer risk among white, primarily postmenopausal, women, at the population level.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: Grant support from National Cancer Institute cooperative agreements U01-CA98233, U01-CA98710, U01-CA98216, and U01-CA98758 and Intramural Research Program of NIH/National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics.

References

- 1.Sachdev D, Yee D. The IGF system and breast cancer. Endocrine Related Cancer. 2001;8:197–209. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood TL, Yee D. IGFs and IGFBPs in the normal mammary gland and in breast cancer. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2000;5:1–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1009580913795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the human circulation: a review. Hormone Research. 1994;42:140–144. doi: 10.1159/000184186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burger AM, Leyland-Jones B, Banerjee K, Spyropoulos DD, Seth AK. Essential roles of IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-rP1 in breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41:1515–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hadsell DL, Bonnette SG. IGF and insulin action in the mammary gland: lessons from transgenic and knockout models. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2000;5:19–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1009559014703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher O, Gibson L, Johnson N, Altmann DR, Holly JMP, et al. Polymorphisms and circulating levels in the insulin-like growth factor system and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention. 2005;14:2–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen NE, Roddam AW, Allen DS, Fentiman IS, dosSantosSilva I, et al. A prospective study of serum insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I), IGF-II, IGF-binding protein-3 and breast cancer risk. British Journal of Cancer. 2005;92:1283–1287. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canzian F, McKay JD, Cleveland RJ, Dossus L, Biessy C, et al. Polymorphisms of genes coding for insulin-like growth factor I and its major binding proteins, circulating levels of IGF-I and IGFBP-3 and breast cancer risk: results from the EPIC study. British Journal of Cancer. 2006;94:299–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng I, Penney KL, Stram DO, LeMarchand L, Giorgi E, et al. Haplotype-based association studies of IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 with prostate and breast cancer risk: The Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention. 2006;15:1993–1997. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson M, McKay JD, Wiklund F, Rinaldi S, Verheus M, et al. Implications for prostate cancer of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) genetic variation and circulating IGF-I levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4820–4826. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setiawan VW, Cheng I, Stram DO, Penney KL, LeMarchand L, et al. IGF-I genetic variation and breast cancer: the Multiethnic Cohort. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention. 2006;15:172–174. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verheus M, McKay JD, Kaaks R, Canzian F, Biessy C, et al. Common genetic variation in the IGF-1 gene, serum IGF-I levels and breast density. Breast Cancer Res Treat (epub ahead of print) 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9827-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter DJ, Riboli E, Haiman CA, Albanes D, Altshuler D, et al. A candidate gene approach to searching for low-penetrance breast and prostate cancer genes. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5:977–985. doi: 10.1038/nrc1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Jacobs EJ, Almon ML, Chao A, et al. The American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Cancer. 2002;94:500–511. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riboli E, Hunt KJ, Slimani N, Ferrari P, Norat T, et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study populations and data collection. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:1113–1124. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses' Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:388–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rexrode KM, Lee IM, Cook NR, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Women's Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:19–27. doi: 10.1089/152460900318911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankin JH, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, et al. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:346–357. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes RB, Reding D, Kopp W, Subar AF, Bhat N, et al. Etiologic and early marker studies in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:349S–355S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng I, Stram DO, Penney KL, Pike M, LeMarchand L, et al. Common genetic variation in IGF1 and prostate cancer risk in the Multiethnic Cohort. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:123–134. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stram DO, Haiman CA, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Kolonel LN, et al. Choosing haplotype-tagging SNPS based on unphased genotype data using a preliminary sample of unrelated subjects with an example from the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Hum Hered. 2003;55:27–36. doi: 10.1159/000071807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Packer PB, Yeager M, Staats B, Welch R, Crenshaw A, et al. SNP500Cancer: a public resource for sequence validation and assay development for genetic variation in candidate genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:D528–532. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLellis K, Ingles S, Kolonel L, McKean-Cowdin R, Henderson B, et al. IGF1 genotype, mean plasma level and breast cancer risk in the Hawaii/Los Angeles multiethnic cohort. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:277–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinaldi S, Peeters PH, Berrino F, Dossus L, Biessy C, et al. IGF-I, IGFBP-3 and breast cancer risk in women: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:593–605. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schernhammer ES, Holly JM, Pollak MN, Hankinson SE. Circulating levels of insulin-like growth factors, their binding proteins, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:699–704. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaykin D, Westfall P, Young S, Karnoub M, Wagner M, et al. Testing association of statistically inferred haplotypes with discrete and continuous traits in samples of unrelated individuals. Human Heredity. 2002;53:79–91. doi: 10.1159/000057986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feigelson HS, Cox DG, Cann HM, Wacholder S, Kaaks R, et al. Haplotype analysis of the HSD17B1 gene and risk of breast cancer: a comprehensive approach to multicenter analyses of prospective cohorts. Cancer Research. 2006;66:2468–2475. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Blouin MJ, Pollak MN. Polymorphic variation at the -202 locus in IGFBP3: influence on serum levels of insulin-like growth factors, interaction with plasma retinol and vitamin D and breast cancer risk. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;107:60–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slattery ML, Sweeney C, Wolff R, Herrick J, Baumgartner K, et al. Genetic variation in IGF1, IGFBP3, IRS1, IRS2 and risk of breast cancer in women living in Southwestern United States. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2007;104:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner K, Hemminki K, Israelsson, Grzybowska E, Soderberg M, et al. Polymorphisms in the IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 promoter and the risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2005;92:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-2417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]