I am not a scholar, but a maker, and in an amateur way I would like to use this opportunity to discuss the relationship between sculpture and the viewer and also to say something about the evolution of my own work in the past 5–6 years. I am naturally passionate about the art of sculpture, but I am also passionate about art in general. I am very interested in Antonio Damasio's research into the modes of self-consciousness necessary for the arising of feeling, and how that might relate to my art form. I think that all art is an expression of and an instrument for the evolution of feeling in the same way that maths or logic might be for the expression of the intellect and that gymnastics might be for the training of the body. For me, sculpture is the art of the palpable that makes feeling intelligible.

Traditionally, the economy between the sculpture and the viewer went in one direction: feelings of awe, desire and changing notions of the beautiful were in some way objectified in sculpture. My interest has also been in an energy flow that goes in the opposite direction, in the feelings and experiences that sculpture somehow provokes in the viewer.

Sculpture has a dual nature: it is both a thing amongst other things and a picture of something; an embodiment of our sense of internal space, and an occupation of space. What precisely is embodied in sculpture and what are we responding to? In a sense, the artist has gone on a journey to make something, and the viewer must go on one to make something of it too.

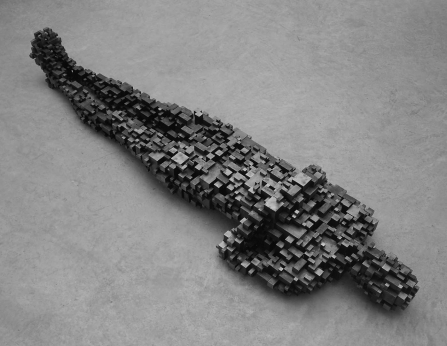

As Bruno Adriani points out, the dual nature of sculpture is mirrored by the dual nature of our response to it. The beholder may transfuse and transpose the system of coordinated axes of her own organism onto the sculpture (in other words, she empathetically inhabits it), or conversely she can see it as an object ‘out there’, as an objectification of her relationship to space, a realized model of self and the world (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Making space 2004. Stainless steel blocks 25×25×50 mm and 25×25×25 mm; 202×51×50 cm. Photographer: Steve White, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

To me, both of these approaches are viable and necessary: the self objectified as other, as thing, and the other, or the thing, empathized with as self. Both possibilities are liberating. Experiencing the self as an ‘other’ thing can be both an extension and a point of reflection.

Maybe sculpture itself is an act of liberation, a kind of myth of conception and origin so that in engaging with the object's own ontology, something is passed from the nature of the object to the beholder. So that the progression of form, motif, image, symbol—‘the shape of the thing’ in Erwin Panofsky's terms—are combined with Henri Poincaré's making of our experiences of abstract space into something concrete. Through this, the model that a sculpture both presents and embodies escapes from the condition of being a model. By being both an image and an object, actual and abstract, it becomes a kind of diagram of realization, of an activity which hopefully blends intuition and measure, mathematics and poetics, which can be both with a referent and absolutely itself. Poincaré developed a very useful idea that we can take our own body as an instrument of measurement in order to construct space, but not geometrical space, nor the space of representation (perspective), but space as a form of instinctive geometry.

I try through my work to provide the means that Poincaré demanded to fix our position in space. He says that every human being has to construct first this restricted space and then is capable of amplifying, by an act of imagination, ‘the restricted space to the great space where he can lodge the universe’ (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distillate II 2003. Bright mild steel blocks. 12.5×12.5×25 mm, 25×25×50 mm, 50×50×100 mm and 100×100×200 mm; 200×58×29.5 cm. Photographer: Steve White, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

This concentrated and restricted ‘defined space’ of sculpture becomes a virtual volume that gives whatever space it is put in a sense of proportion and relationship which mirrors the way that an environment is given proportion and relation by human inhabitation.

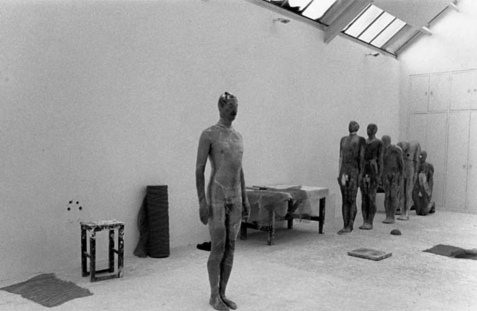

I would like to feel that what I am doing is healing Pascal's division between the mathematical and the intuitive mind. He says in his Pensées: ‘what prevents many intuitive minds from being mathematical is their absolute inability to look at the principles of mathematics and what prevents the mathematician from being intuitive is that they do not see what is before their eyes’. I seek to use objective means to describe subjective states. Having decided that the core of sculpture is a fulfilment of Adolf Hildebrand's aphorism ‘all forms have the purpose of making space visible and its continuity sensible’, my wager is to preserve the thing of sculpture in its autonomy while allowing for a degree of empathic inhabitation. It is not enough simply to make space visible: we have to make it felt. My methodology for doing that is to start with the experience of life and consciousness within the body (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Antony Gormley studio views (one of Antony standing wrapped in clingfilm with row of moulds to the left of him). Photographer: Elfi Tripamer, Vienna. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

I guess we then have to ask how these works fit into the world and how they can evoke or identify a feeling in space, how in a time of extreme visual cacophony in the built environment do we use the space of sculpture to reinforce the self in this confused and commercialized world? As we walk down the street, our attention is constantly bombarded with bright new goods in the shop windows, a man trying to evangelize with a microphone in the centre of the street, brief glimpses of the weather, a cloudless sky, an impending storm, large advertisements, the ringing and talking in mobile phones. In this distracting and distracted world, so lacking in cohesion, how do we insert sculpture as both a point of symbolized self in the world and a place for self in the world, a place that is silent, still, removed (figure 4)?

Figure 4.

Total strangers, 1996. Cast iron, 195×54×32 cm. Photographer: Antony Gormley, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

How do we make a sculpture into a point of origin which is both a symbol and a fusing of that symbol with what it symbolizes? A symbol for self and a place for self.

So to go back to where we started, if art moulds our emotional life in the same way that logic or mathematics might mould our intellectual life, and given that life experience is so fluid and fleeting and difficult to remember, how can art be a concentrated form of remembering? Can memory cohere in an object and if so how does it evoke memory in the viewer? Are we expected to remember another's experience or does the experience of sculpture, which is itself the embodiment of a particular feeling, give rise to another feeling, the viewer remembering something within his or her own experience that need have no relationship whatsoever with the original experience of the making of the work?

The fact is that art is not a recreation; it is the record of its own making, of a journey made from first impulse to a reconciliation with materiality. Art's central role is not to make the perfect copy. Real objects can become images but not the other way round. An image is always a virtual thing, a semblance, but my project is to make that virtuality as physical as possible. In nature the most striking visual phenomena are intangible: rainbows, mirages, shadows. I think that it is worth restating, as Susanne K. Langer has done, that all art is abstract in the sense that it separates semblance from material existence; painting by making a two-dimensional picture of something, and sculpture by making a semblance that is at the same time built on its own terms. This remembering, remaking, are not ends in themselves, nor are abstraction or figuration ends in themselves. It is simply that the principal aim of art is to alienate forms from their original or common use and to put them to new use, to become expressive of human feeling—and to me this human feeling is an internal one, what Langer has called ‘the familiar illusive pattern of sentience’: another or strange form which is given back to our perception and yet at the same time reaches beyond itself, a semblance charged with reality that feels towards outer space, to that beyond the palpable.

The historical view, particularly of the male sculptor, is of someone who works at arm's length making a sexualized or idealized bodyform out of a block of marble or a pile of clay, either an adding or subtracting process, the modeller or the carver. Sculpture has always been associated, ever since the time of Donatello and Michaelangelo, with egotistical determinism. I start from somewhere indeterminate, from the absolute subjectivity of the lived moment, with the idea that the only part of the material world that I actually inhabit is my own body, and that in it I have a sensitized and experiential field that can be acted on or made conscious from within.

This is a complete contestation of Plato's problem with arts in his Republic. He calls the artist's product ‘third hand’, since it is neither the result of the origination of a form nor the experience of its use, but a mere illusion of an illusion trying to capture through mimesis, and in some sense trick us into ascribing feeling to something that is merely a sham. My way of solving this particular problem is to try to use the body not as an actor in a mimetic tableau, nor as a form of representation that can become idealized, but to work from the other side of appearance, from inside the skin, replacing an idealized and determined representation by a subjective, indeterminate, internalized register of a lived moment (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Antony Gormley studio views (one of Antony's head covered in plaster (untitled-14)). Photographer: Elfi Tripamer, Vienna. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

I would suggest that this indexical registration is more accurate as a way of transferring the innate affective conditions of the body, and indeed of summoning them within the viewer's response, than the traditional forms of representation.

The real challenge of making sculpture today, making these discrete objects that can be exposed in the elemental world or shared in the collective spaces of our lives, is: how do we make their inherent silence and stillness active? How do we not take the standing of a sculpture for granted? How do we make the being that embodiment bears witness to both adequately present but also adequately open? How, in other words, do we reconcile the determinism of material presence with the indeterminism of experience (figure 6)?

Figure 6.

Another place, 1997. Cast iron, 100 figures/189×53×29 cm. Photographer: Helmut Kunde, Kiel. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

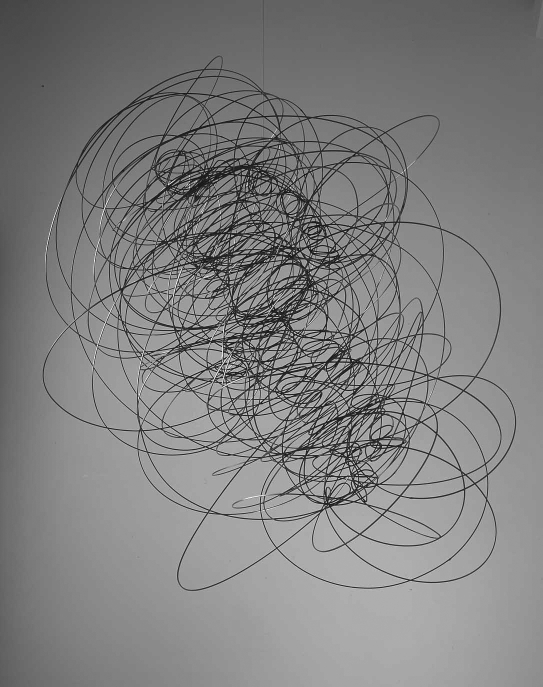

So I start with the indexical as opposed to the representational as my model, but then I have to think very hard about how the material and constructional processes are allied to this. This is the second level in which feeling comes into form. This is entirely intuitive and could be related to the way in which jazz or any form of improvized music uses the structures of octave, quaver, semi-quaver and all of the notational structure of music, in a way that is responsive to an emergent structure: a structure that evolves in time. The kind of sculpture that I am proposing starts with an indexical trace of a lived moment that has its own affective atmosphere, but this is then interpreted by a second level of evocation of feeling in relation to this lived body-space. Increasingly with my work I have attempted to find, through the association of algorithmic systems, a field that is rational, constructive but also open, so the internal subjective experience tries to find an objective equivalent using the laws of building, engineering, weight, measure and of mathematics, in order to see an internal state that is unmeasurable. This is a blending of the mathematical with the poetical in material, a form of physical thinking. And this is the second level of affective work determined by primary choice of material, i.e. we were going to use 50×25 mm square blocks (figure 7) or thin linear trajectories or round steel balls to interpret the body space (figure 8).

Figure 7.

Sublimate 2004. Bright mild steel blocks 12.5×12.5×25 mm, 25×25×50 mm, 50×50×100 mm and 100×100×200 mm; 195×52×32 cm. Photographer: Steve White, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

Figure 8.

Installation: Galerie Xavier Hufkens 2002. Bodies in Space V and Lost Dog II.

All this may strike you as being very abstract, so what I want to do is try to describe the processes by which I actually make a sculpture, in this case one of my recent ‘variable block’ works (the Precipitate, Sublimate, Concentrate series). All of my work starts from a position of unknowing, from a position of direct, raw being. It is a moment of lived time taken out of time which is in some way a point of origin. I am naked covered in a layer of clingfilm and my living body is registered in a chemical and mineral way in plaster. This three-dimensional negative that shows the space of my body is then translated into a three-dimensional positive form. That transposition is then translated into a construction using four different block sizes, each block being eight times bigger than the one before. The idea of these algorithmic build programmes is to find a means of measurement that translates the anatomy of the body normally configured in the relationship between bone, skin and muscle, into another kind of matrix more familiar to mathematicians or to builders. This new matrix becomes a kind of diagnostic instrument that transfers the inner set or attitude of the body into another form and allows us to see it anew (figure 9).

Figure 9.

Precipitate II 2004. Bright mild steel blocks 12.5×12.5×25 mm, 25×25×50 mm, 50×50×100 mm and 100×100×200 mm; 82×47×65 cm. Photographer: Steve White, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

This I think of as a kind of crystallization, a condensation of the subjective experience of the internal nature of the body into an objective form, a bodyform that is a gestalt, a unitary object made out of many parts. Each of those parts has an absolute and orthogonal relationship to those that lie around it. They conform very precisely to the way in which in digital imagery an image is held within an orthogonal matrix of squares, where the value of each square indicates something of the way that light falls on the surface of an object. These works have more to do with the condensation of mass conforming to some inner sense of the body. There is a contradiction in the way that these works can be read: on the one hand as an architectural model or an abstract image of absolute geometrical volumes, and on the other as an allusion to a body itself. Architecture contains the body in the absolute coordinates of vertical and horizontal construction. Here we have the internal body materialized using similar means (figure 10).

Figure 10.

Feeling material X (hanging) 2004. 4 mm×4 mm continuous rolled mild steel wire, 260×210×190 cm. Photographer: Steve White, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

Another way of materializing a zone of feeling is not about crystallization so much as ‘energization’, or the creation of a field—I explore this in the Feeling Material works, where I use a three-dimensional positive as the core around which a continuous line of mild steel up to 800 m in length is spun, so that the line makes an orbit around the edge of the body, then shoots into outer space, returning again to the bodyzone. So it might go around the wrist and then disappear into space and make one turn around the body and then re-enter the bodyzone at the chest, go out again, hit the bodyzone again around the neck. This continual orbiting from the surface of the bodyzone to its farther reaches builds up an energy field, a web, a net which can trap the eye of the beholder but also identify space. The work creates a kind of ‘feeling zone’. These works use the tensile properties of the material to create a matrix that evokes the laws of motion, of subatomic particles circling a nucleus and more recent theories of worm holes and string theory. Again, these sculptures have nothing to do with representation but with trying to make both an evocation of a zone of sensation and a matrix onto which sensations can be projected. They constitute a final layer of complication in terms of the syntax of feeling into form by objectifying the tension between mass and space.

If the earlier moments of essentialism within modernism defined an absolute mass, usually with a very highly finished and polished surface (extending substance into light, as in the work of Constantin Brancusi and Jean Arp), I am increasingly interested in making a mass that is active by interpenetrating the overall gestalt of the form with absence. So the stillness and the totality of the overall form is qualified by a kind of vibration of mass to void, presence to absence.

In conclusion, we have to ask how do sculptural form and the feeling that it provokes coalesce? My response to that would always be that they coalesce in the imagination of the viewer, not in the intrinsic and independent reality of the work. I think that we have evolved now from the fetishized notion of the unique and intrinsically valuable object to the idea that actually the real location of value is within the viewer. I would not like to think that these works are understood simply as symbols or signs, or even archetypes of aspirations towards wholeness and integrity. I see them as being an acknowledgement of the provisional nature of human experience, but also an expression of a desire to provide catalysts for hope.

Nothing is illustrated here, there is no narrative, but there is an act of constitution demanded of the viewer. There is a moment in which the independence and emancipation of art from a form of representation are offered to the viewer, and in that identification with the space of self lies a kind of freedom. I would like to suggest that in this there is a connection between the individual and oceanic, the particular and the field, that combines a re-interpretation of the sublime with a re-positioning of where art belongs, and explores anew whom it can be for and where it can be found.

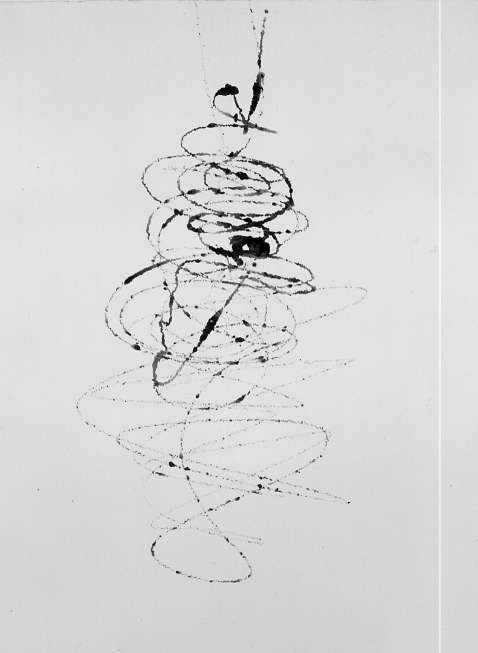

For me, the art of sculpture starts with a concentration in a single object separated from other objects. Therefore, it is a restricted thing, which can at the same time be a objectification of a sense of self and environment, offered to the sense of sight. In the moulding process I have to be very still and to be breathing regularly. I have to try not to think about the outside and to be completely concentrated on the space that exists behind appearance. At first this experience is very claustrophobic (figure 11).

Figure 11.

Trajectory field 21, 2003. Black pigment on paper, 38.2×28 cm. Photographer: Steve White, London. Courtesy of the artist and Jay Jopling/White Cube.

As the plaster goes on and I am enclosed ever more deeply in a damp, dark, soft enclosure, there is a descent into the darkness of the body. This is the space that we all spend our lives escaping from but it is also the place of imagination: a place that starts with feelings of claustrophobia but opens into an extension as wide as a sky at night. I use this space as the place of origination for my sculpture. It is not inscribed, it has no face, there are no values, there is no measurement. It is the place out of which experience arises, into which fear and longing fall. I see it as the space from which all potential comes and the space to which I have to continually return in order to make the subjective truth of experience real.

Footnotes

One contribution of 21 to a Theme Issue ‘Bioengineering the heart’.