Abstract

Title

Turnover intention in new graduate nurses: a multivariate analysis

Aim

This paper is a report of a study to determine the relationship of new nurse turnover intent with individual characteristics, work environment variables and organizational factors and to compare new nurse turnover with actual turnover in the 18 months of employment following completion of a residency.

Background

Because of their influence on patient safety and health outcomes nurse turnover and turnover intent have received considerable attention worldwide. When nurse staffing is inadequate, especially during nursing shortages, unfavourable clinical outcomes have been documented.

Method

Prospective data collection took place from 1999 to 2006 with 889 new paediatric nurses who completed the same residency. Scores on study instruments were related to likelihood of turnover intent using logistic regression analysis models. Relationships between turnover intent and actual turnover were compared using Kaplan–Meier survivorship.

Results

The final model demonstrated that older respondents were more likely to have turnover intent if they did not get their ward choice. Also higher scores on work environment and organizational characteristics contributed to likelihood that the new nurse would not be in the turnover intent group. These factors distinguish a new nurse with turnover intent from one without 79% of the time. Increased seeking of social support was related to turnover intent and older new graduates were more likely to be in the turnover intent group if they did not get their ward choice.

Conclusion

When new graduate nurses are satisfied with their jobs and pay and feel committed to the organization, the odds against turnover intent decrease.

What is already known about this topic

There is concern in many countries about nurse turnover and the resulting effects on patient safety and quality of care.

Decreasing ability to recruit experienced nurses has increased the emphasis on recruitment of new graduate nurses, particularly in the United States of America.

Historically, new graduate nurses have a high turnover rate within the first year of employment.

What this paper adds

When new graduate nurses are satisfied with their jobs and pay and feel committed to the organization, the odds of turnover intent decrease.

Increased seeking social support to cope with the transition from student to competent Registered Nurse is related to turnover intent.

Older graduates (>30) are 4·5 times more likely to have turnover intent if they do not get their ward of choice.

Keywords: longitudinal study, nursing, paediatric nurses, personnel turnover, support, work environment

Introduction

When the nursing shortage reached our hospital in the late 1990s, nurse recruitment and retention were identified as organizational imperatives. High vacancy rates affect hospital efficiency because of the costs associated with recruiting and orienting replacement nurses, hiring temporary agency nurses and supervising new nurses. Furthermore changes in nurse staffing decrease the effectiveness of team-based care on patient units; this results in less effective working relationships between nurses and physicians and thus ultimately affects patient care (Cangelosi et al. 1998, Hassmiller & Cozine 2006). This situation is not unique to the United States of America (USA) but has become a global concern, with attention focusing on nurse workload, staffing, turnover and organizational characteristics and their influence on patient safety and health outcomes (Aiken et al. 2001, Stone et al. 2003, O’Brien-Pallas et al. 2006).

Recruitment and retention of nurses to work in the high stress, complex environment of acute care hospitals, however, are challenging. In particular, children require extremely complex nursing care that demands a high level of competency to meet social mandates for safety and quality. In 1998 decreased recruitment of experienced nurses and increased Registered Nurse (RN) vacancy rates added pressure to attract more new graduates to our hospital. For new graduates, this environment is daunting. Nursing programmes in the USA provide limited clinical paediatric experience; this is seriously insufficient for the intense work environment, advanced medical technology and high patient acuity, which in our organization is the highest in Los Angeles County. To avoid the early flight of new nurses that occurred in the USA during the nursing shortage of the early 1980s, where 35–60% of new graduates left their employment within the first year of graduation (Hamilton et al. 1989), a 22-week residency was created to support new nurses during this transition. The residency was standardized across hospitals and incorporated guided clinical experiences, mentoring, one-to-one preceptorships, classroom activities and skills laboratories (Beecroft et al. 2001). Over the past 7 years, data linked to turnover and related variables have accumulated from six paediatric hospitals using the nurse residency programme. In this paper, we report on the analysis of these data and give insight into factors related to turnover among entry-level nurses during the first 24 months of employment.

Background

Because of their influence on patient safety and health outcomes, nurse turnover and turnover intent have received considerable attention worldwide (Stone et al. 2003). When nurse staffing is inadequate, especially during nursing shortages, unfavourable clinical outcomes have been documented. Aiken et al. (2002) found, in a study of 10,184 staff nurses, that a higher patient:nurse ratio was linked to increased risk of patient mortality. Furthermore, additional patient:nurse ratios increased the odds of nurse burnout by 23% and the odds of job dissatisfaction by 15%. Common reasons for turnover in the USA, Canada, England, Scotland and Germany, included problems in work design and emotional exhaustion (Aiken et al. 2001). Other researchers linked nurse job satisfaction directly to satisfaction with nursing care (McNeese-Smith 1999, Tzeng et al. 2002).

Job satisfaction as a predictor of anticipated turnover has been reported in several studies (Lucas et al. 1993, Lu et al. 2005). In their model of turnover, Hinshaw et al. (1986) included job satisfaction along with age, education, experience in nursing and job stress as individual characteristics and group cohesion and control over practice and autonomy as organizational factors contributing to anticipated and actual turnover. Similarly, Ingersoll et al. (2002) investigated the contribution of personal or individual and organizational factors to differences in levels of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intent at 1 and 5 years. They determined that age and education, as well as role, employment setting and specialty area, influenced perceptions of the work environment. When nurses perceived their work groups as supportive and cohesive, they were less critical of their organizations and more likely to remain attached to them. Research from various countries has confirmed that job satisfaction is a statistically significant predictor of nursing absenteeism, burnout, turnover and intent to quit (Lum et al. 1998, Shields & Ward 2001, Lu et al. 2005).

In the ‘Magnet hospital study’ in the USA, hospitals were successful based on their quality of care as well as ability to attract and keep nurses (McClure et al. 1983). Key factors in the work environment influenced hospital success and contributed to job satisfaction. Kramer and Schmalenberg (1991, 2004a, 2004b) confirmed this early work in subsequent studies demonstrating that Magnet hospital staff were more satisfied and had less turnover that non-Magnet staff. Decentralized decision-making, autonomous and empowered behaviour, communication, open and collaborative relationships with physicians and working with other clinically competent nurses contributed to nurse job satisfaction and, ultimately, to care quality, recruitment and retention.

In the mid to late 1990s, other researchers added to the growing literature on work environment influences on job satisfaction. Sabiston and Laschinger (1995) determined that individuals who feel empowered are likely to be more satisfied with their jobs, more committed to the organization and feel more control over their work. As a follow-up, Laschinger and Havens (1996) indicated that people are empowered when the work environment gives access to the information, support and resources necessary to getting the job performed and access to opportunities to learn and grow. When empowerment increases self-efficacy, then organizational commitment, autonomy, job satisfaction and perceptions of participative management result. Finally, organizational support that empowers nurses to use their knowledge and skills on patients' behalf enables nurses to employ professional knowledge and interventions to ‘rescue’ patients from dire and costly consequences (Havens & Aiken 1999).

The concept of professional-bureaucratic conflict originated with Corwin and Taves (1962) and was applied to new nurses, showing that dissonance or conflict between educational preparation and the realities and expectations of work occurred (Kramer 1974). Despite this early work, nursing stress or conflict triggered by inability to give the quality of care expected has persisted as a factor in new nurse retention problems (Gardner 1992, Cangelosi et al. 1998, Cowin & Hengstberger-Sims 2006).

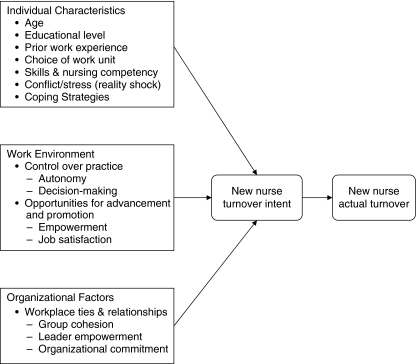

Model for investigation

A number of factors incorporating individual, work environment and organizational variables were found important to nurse retention in the literature and were included in the model tested in the study reported in this paper (see Figure 1). The model was adapted from previous work that analysed job satisfaction, individual, work environment and organizational factors in relationship to turnover intent or actual turnover (Hinshaw et al. 1986, Ingersoll et al. 2002, Yin & Yang 2002, Lu et al. 2005, Tourangeau & Cranley 2006).

Figure 1.

Model for investigation.

Whether or not these variables apply to new graduate nurses during their first year of employment has received limited attention. Recently, Suzuki et al. (2006) identified graduation from vocational nursing schools, dissatisfaction with assignment to a ward contrary to their desire and no peers for support as factors related to new nurse turnover in Japan. Our proposed model for investigation readily incorporated these factors. Therefore, our focus was to validate the relationship of variables identified in published research to turnover intent and actual turnover in new graduate nurses following a transition residency and throughout their first 24 months of employment.

The study

Aim

The aim of the study was: (i) to determine the relationship of new nurse turnover intent (TI) with individual characteristics of age, educational level, prior work experience, choice of work unit/ward, skills and nursing competency and coping strategies; work environment variables including control over practice (empowerment, autonomy, decision-making) and opportunities for advancement and promotion (job satisfaction); and organizational factors reflected in workplace ties and relationships with leaders and co-workers through group cohesion, leader empowerment and organizational commitment and (ii) to compare new nurse TI with actual turnover in the 18 months of employment following completion of a residency.

Design

A prospective survey design was used with data collection initiated in July 1999 and continuing to the present. Seven years of data are used for the current analysis.

Respondents

Study respondents were new nurse graduates (n = 889) in paediatrics who took part in a standardized nursing residency. The residency was initiated in July 1999 at our hospital and at other hospitals starting 2·5 years later and using the same content and methods.

All nurses who finished the residency completed an evaluation at programme conclusion. More than half were 23–30 years of age (n = 323, 56%) and had a baccalaureate degree or higher (n = 318, 57%). Moreover, many had previous experience in healthcare (n = 418, 72%) and were assigned to their first choice of nursing unit/ward (n = 522, 88%). Paediatric hospitals that submitted data on 50 or more respondents with at least 1 year of follow-up were included. All hospitals were not-for-profit and were of a similar bed size (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected respondent characteristics and relationship to turnover and turnover intent

| Variable | Turnover intent (n = 307/889) | Actual turnover (n) | Actual turnover rate* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital (n beds) | |||

| A (381) | 23/67 (34) | 3 (4·4) | 0·0051 |

| B (286) | 120/337 (36) | 85 (25·2) | 0·0073 |

| C (257) | 40/100 (40) | 2 (2) | 0·0018 |

| D (244) | 55/219 (25) | 39 (17·8) | 0·0071 |

| E (232) | 42/107 (39) | 14 (13·1) | 0·0067 |

| F (222) | 27/59 (46) | 4 (6·7) | 0·0051 |

| χ2 = 14·9501, d.f. = 5, P = 0·011† | |||

| Age | |||

| <23 | 82/182 (45) | 36 (19·7) | 0·0081 |

| 23–30 | 170/493 (35) | 81 (16·4) | 0·0065 |

| 31–40 | 42/145 (29) | 20 (13·7) | 0·0056 |

| Over 40 | 13/69 (19) | 10 (14·4) | 0·0064 |

| χ2 = 18·4115, d.f. = 3, P ≤ 0·001† | |||

| Education | |||

| AA and lower | 115/379 (30) | 63 (16·6) | 0·0029 |

| BS or higher | 192/510 (38) | 84 (16·5) | 0·0035 |

| χ2 = 4·9397, d.f. = 1, P = 0·026† | |||

| First choice of ward/unit | |||

| Yes | 257/779 (33) | 23 (20·9) | 0·0085 |

| No | 50/110 (46) | 124 (15·9) | 0·0064 |

| χ2 = 6·2958, d.f. = 1, P = 0·012† | |||

| Previous Experience | |||

| Yes | 220/668 (35) | 35 (13·9) | 0·0063 |

| None | 87/251 (35) | 112 (17·5) | 0·0068 |

| χ2 = 0·006, d.f. = 1, P = 0·936† | |||

| Older without first choice of ward/unit | |||

| Age ≤ 30 or first choice = yes | 290/858 (34) | 138 (16·1) | 0·0065 |

| Age > 30 and first choice = no | 17/31 (55) | 9 (29·0) | 0·0125 |

| χ2 = 5·9086, d.f. = 1, P = 0·015† | |||

Values are expressed as n (%). AA, associate arts; BS, bachelor of science.

Actual turnover rate is the number that left divided by total number of months from hire for each hospital. This adjusts for different number of months from hire for each hospital.

Chi-square test applies to turnover intent only.

Instruments

All instruments except the Skills Competency Self-Confidence Survey are published tools with established reliability and validity. Initial psychometrics may be obtained from the references for each instrument. After accumulating 4 years of data the instruments were evaluated to determine if all items contributed substantially to total scores. This was performed in an effort to decrease respondent burden related to the number of instruments used. Forty-nine items that did not differentiate early leavers (within 24 months of hire date) from non-leavers or with low Cronbach alpha levels were removed. Cronbach alpha levels, which were the same or higher for the revised instruments, are given below.

Individual characteristics

Data on age, educational level, prior work experience and choice of work unit/ward were collected on a demographics form developed specifically for this evaluation. Skills competency was measured using the Skills Competency Self-Confidence Survey. This is a self-rating tool that includes generic skills for a paediatric Registered Nurse, with items derived from a paediatric staff nurse competency profile (Beecroft et al. 2004). Also the Slater Nursing Competencies Rating Scale: Self-Report (Wandelt & Stewart 1975) was used to provide a self-rating of performance in the clinical setting. The scale was adapted for paediatric nurses and reduced from 84 to 76 items (total scale α = 0·98). Professional orientation using the professional subscale (Lawler 1988) from Corwin's Nursing Role Conception Scale (Corwin & Taves 1962) was used to determine level of dissonance (conflict) experienced by new nurses between school preparation (‘ideal’ score) and the realities and expectations of work (‘real’ score). The Ways of Coping Revised (WOCR) instrument (Folkman & Lazarus 1988) was also used to assess cognitive and behavioural coping strategies used to deal with the transition from new graduate to staff nurse.

Work environment

Control over practice was measured by the Conditions for Work Effectiveness Questionnaire (CWE), Schutzenhofer Professional Nursing Autonomy Scale (PNA) and Clinical Decision-Making Scale (CDM). The CWE measured nurse perceptions of workplace empowerment. Specific structural factors that influence work behaviours include four subscales: opportunity, job activities, coaching and support and information. Respondents were given a list of specific items and asked to indicate what they have available now (denoted by ‘have’) and what they would like to have (denoted by ‘like’), which resulted in two scales (Chandler 1992). The PNA scale (Schutzenhofer 1988) describes clinical situations in which nurses must act autonomously to some degree. Eight items were deleted and one item re-worded for clarity (total scale α = 0·86). The CDM includes 33 statements about decision-making in the clinical setting. Each statement is answered on the basis of what a respondent is doing now (Jenkins 1985). Seven items were deleted from this scale with a change in α from 0·82 to 0·84. Job satisfaction was measured using the Work Satisfaction Scale (WS) and the Nurse Job Satisfaction Scale (NS) from Hinshaw and Atwood (1983). Three subscales in the NS were revised, with the deletion of two items for quality of care, two items for enjoyment and one for time to do one's job subscales, giving a change in total scale α from 0·88 to 0·89. Four subscales from the WS Scale were revised, with the deletion of one item from pay, three from professional status, one from interaction/cohesion and one from administration. The total scale α changed from 0·85 to 0·84.

Organizational factors

Workplace ties and relationships were measured using the Leader Empowerment Behaviours Scale (LEB), Group Cohesion Scale (GC) and Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OC). The LEB was revised to 16 items with the deletion of two subscales (total scale α = 0·95 unchanged). Higher scores indicate higher levels of empowerment (Hui 1994). GC elicits respondents’ opinion about the colleague group (nursing staff) with whom they work in terms of productivity, efficiency, morale, personal feelings, belongingness and working together (Good & Nelson 1973). The OC Questionnaire (Mowday et al. 1979) was revised, with deletion of four items. Scale α changed from 0·87 to 0·88. The QC measures the relative strength of an individual's identification with and involvement in a particular organization with higher scores indicating more commitment.

Turnover intention

This is a global measure of an individual's intention to leave the hospital and is a single-item scale which asks ‘Do you plan to leave this facility within the next year?’ Scores range from (1) not at all to (7) I surely do (Hinshaw & Atwood 1982).

Actual turnover

Turnover was defined as voluntary termination of employment at the hospital. Transfer between units/wards or other departments in a medical centre was not considered turnover. Length of tenure was the number of months from hire date into the residency to termination date.

Data collection

Survey responses from all new nurses who finished the residency were obtained at programme completion. Paid class time was provided for completion of the questionnaires, which was an expectation of the residency. No-one asked to be excluded from participation. Manual data entry occurred during the first 4 years and was double-checked for accuracy. Then Versant Voyager® (Versant RN Residency, Los Angeles, CA, USA) (a web-based management system) and personal handheld or laptop computers were used. Automated data entry was validated with manual data entry samples.

Ethical considerations

Each hospital's Institutional Review Board approved or exempted the study. Respondents were informed about study purpose at the start of the residency and were given an information sheet about data collection and management. Identification codes were used to maintain anonymity.

Data analysis

A variable that identified older nurses (>30 years) who did not get their first choice of nursing unit/ward was added to individual characteristics. This variable was statistically significant in relationship to mentoring new nurses in another study (Beecroft et al. 2006).

Sixty-six percent of nurses who selected ‘1’ on the TI scale indicated no turnover intention. Initial review of those who indicated any level of TI revealed similar results on most instruments, regardless of TI strength. Therefore, the TI item was transformed to a dichotomous variable with no TI (score = 1) and TI (score > 1). Fisher et al. (1994) made a similar transformation.

In our analysis, individual scores (total and subscales), with the exception of Corwin's professional subscale, were transformed to percent of maximum possible score, with a subsequent range from 0% to 100%. Thus, instruments with different total scores were easily compared. Higher scores indicate better levels of the characteristic in question for these surveys. As explained previously, instruments were aligned with a category of variables identified from previous research describing individual, work environment and organizational factors in relationship to turnover intent or actual turnover. A univariate analysis of demographic variables with TI was performed using the chi-square test.

A univariate logistic regression analysis was performed on each instrument. Subsequently, within each category of variables (individual, work environment, organizational) a multivariate stepwise logistic regression, using an entry probability of P < 0·15, was performed to find a subset of instruments that jointly contributed statistically significant information to participants’ TI. Only the most influential variables within the three categories were used in the final multivariate analysis. Thus, variables were first reduced within each category for the final analysis. Then, using the most statistically significant variables from each of the categories, a stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to find a parsimonious model containing most of the information on TI. Comparison of nested models was based on the likelihood ratio test; goodness of fit was evaluated using the Hosmer–Lomeshow statistic and the model's classification ability was based on area under the ROC curve. In a logistic regression model, a value is assigned to each respondent representing the probability of that respondent being from the TI group. The area under the ROC curve gives the percentage of time that a random respondent from the TI group would be assigned a higher probability than a random respondent from the non-TI group. Thus, it represents a measure of correct model classification and is used to compare different models. A value of 0·5 represents a model with prediction no better than chance. A value of 1·0 represents perfect prediction. Results of the logistic regression models are presented with odds ratios (OR) along with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Odds ratios are presented as a per unit increase in each variable.

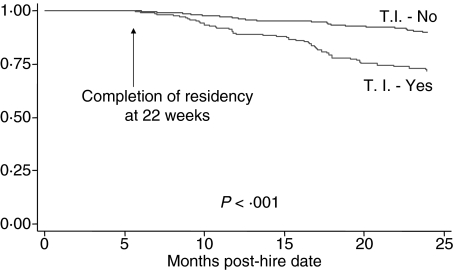

Relationship between TI at programme conclusion and actual turnover in the subsequent 18 months was investigated by using Kaplan–Meier survivorship technique and log rank statistic. Data were analysed using SPSS, version 10.1 (Chicago, IL, USA) and STATA, version 9.0 (College Station, TX, USA). As in the case of multivariate statistical models, other combinations of variables may give a similar ability to predict TI. Because of the correlation structure, however, two different models may not be as different as might appear. The important point is that all variable groupings contribute statistically significant and somewhat independent information about TI.

Results

Younger respondents were more likely to indicate TI (P = 0·001). Also respondents were more likely to indicate TI if they had a higher level of education (P = 0·026), or did not receive first choice of nursing unit/ward (P = 0·012), or were older and did not get their first choice of nursing unit/ward (P = 0·015). The statistical significance of TI and not receiving choice of nursing unit/ward can be attributed to older nurses (>30 years) who did not get their first choice. Among nurses <31 years old, there is no relationship between TI and first choice (42% vs. 38%, χ2 = 0·754, d.f. = 1, P = 0·386). A statistically significant difference (P = 0·011) was shown between hospitals for TI, which ranged from 25% to 46% for some turnover intent (34% overall; Table 1).

Respondents who indicated TI rated themselves lower on both skills self-confidence (P = 0·021) and Slater nursing competencies (P = 0·014) when compared with those who indicated no TI. Also they reported using positive reappraisal (P = 0·029) and planful problem-solving (P ≤ 0·001) coping strategies less frequently and escape-avoidance (P ≤ 0·001) coping strategies more often than new nurses with no TI. Furthermore, new nurses with TI scored lower on all other scales and subscales except for the CWE subscales of ‘job flexibility like’, ‘information like’, ‘coaching and support like’ and ‘work effectiveness like’, where they scored higher than those with no TI. On the other hand, available now scores (denoted as ‘have’) were lower and would ‘like’ to have scores were higher for the TI group than for the no TI group. Group differences were statistically significant except for ‘job flexibility have’ and ‘information like’ (Table 2). All scores on Table 2 except for Corwin's professional subscale are reported as per cent of maximum possible score, with a subsequent range from 0% to 100%. Higher scores indicate better levels of the characteristic in question.

Table 2.

Comparison of organizational fit variables by turnover intent

| Turnover intent (mean ± sd) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No (n = 582) | Yes (n = 307) | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Organizational fit | ||||

| Group cohesion – total | 85 ± 11 | 78 ± 14 | 0·95 (0·94, 0·97) | <0·001 |

| Group cohesion – productivity | 87 ± 12 | 83 ± 14 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Group cohesion – efficiency | 85 ± 16 | 80 ± 17 | 0·99 (0·98, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Group cohesion – morale | 79 ± 18 | 70 ± 21 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·98) | <0·001 |

| Group cohesion - belongingness | 78 ± 18 | 69 ± 22 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Group cohesion – personal feelings | 90 ± 11 | 83 ± 17 | 0·96 (0·95, 0·97) | <0·001 |

| Group cohesion – working together | 91 ± 11 | 84 ± 15 | 0·96 (0·95, 0·97) | <0·001 |

| Organizational commitment – total | 83 ± 13 | 75 ± 12 | 0·95 (0·94, 0·96) | <0·001 |

| Leader empowering behaviours – total | 77 ± 18 | 71 ± 17 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Leader empowering – meaningfulness | 78 ± 19 | 71 ± 18 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Leader empowering – decision-making | 75 ± 20 | 69 ± 20 | 0·99 (0·98, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Leader empowering – confidence | 77 ± 18 | 72 ± 17 | 0·98 (0·98, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Work environment | ||||

| Work satisfaction – total | 68 ± 8 | 62 ± 8 | 0·91 (0·89, 0·92) | <0·001 |

| Work satisfaction – administration | 67 ± 10 | 61 ± 11 | 0·95 (0·93, 0·96) | <0·001 |

| Work satisfaction – interaction | 78 ± 12 | 71 ± 14 | 0·96 (0·95, 0·98) | <0·001 |

| Work satisfaction – pay | 55 ± 16 | 48 ± 16 | 0·97 (0·96, 0·98) | <0·001 |

| Work satisfaction – professional status | 88 ± 10 | 79 ± 11 | 0·92 (0·91, 0·94) | <0·001 |

| Work satisfaction – task | 61 ± 14 | 57 ± 15 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Nurse satisfaction – total | 81 ± 10 | 74 ± 11 | 0·94 (0·93, 0·95) | <0·001 |

| Nurse satisfaction – enjoyment | 85 ± 10 | 78 ± 12 | 0·94 (0·93, 0·95) | <0·001 |

| Nurse satisfaction – quality of care | 77 ± 12 | 72 ± 13 | 0·97 (0·96, 0·98) | <0·001 |

| Nurse satisfaction – time to work | 75 ± 14 | 70 ± 16 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Nursing autonomy – total | 76 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | 0·97 (0·96, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Clinical decision making – total | 75 ± 6 | 73 ± 6 | 0·94 (0·92, 0·96) | <0·001 |

| Conditions for work effectiveness – total | 68 ± 6 | 67 ± 6 | 0·97 (0·95, 0·99) | 0·009 |

| CWE – total opportunity have | 69 ± 12 | 65 ± 12 | 0·97 (0·96, 0·98) | <0·001 |

| CWE – total opportunity like | 71 ± 10 | 72 ± 11 | 1·01 (1·00, 1·02) | 0·176 |

| CWE – total job have | 63 ± 14 | 61 ± 14 | 0·99 (0·98, 1·00) | 0·097 |

| CWE – total job like | 68 ± 13 | 71 ± 13 | 1·02 (1·01, 1·03) | <0·001 |

| CWE – total information have | 56 ± 11 | 54 ± 10 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | 0·002 |

| CWE – total information like | 79 ± 12 | 80 ± 11 | 1·01 (1·00, 1·02) | 0·155 |

| CWE – total coaching and support have | 61 ± 16 | 54 ± 16 | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| CWE – total coaching and support like | 77 ± 12 | 79 ± 12 | 1·02 (1·01, 1·03) | 0·005 |

| CWE – total work effectiveness have | 63 ± 10 | 59 ± 9 | 0·96 (0·94, 0·97) | <0·001 |

| CWE – total work effectiveness like | 74 ± 9 | 76 ± 10 | 1·02 (1·00, 1·04) | 0·017 |

| Individual | ||||

| Ways of coping | 44 ± 11 | 44 ± 11 | 1 (0·99, 1·02) | 0·502 |

| Ways of coping – confrontive coping | 30 ± 14 | 32 ± 13 | 1·01 (1·00, 1·02) | 0·09 |

| Ways of coping – distancing | 35 ± 15 | 36 ± 15 | 1·01 (1·00, 1·02) | 0·126 |

| Ways of coping – self-controlling | 48 ± 15 | 47 ± 14 | 1 (0·99, 1·01) | 0·432 |

| Ways of coping – seeking social support | 57 ± 15 | 56 ± 15 | 1 (0·99, 1·01) | 0·401 |

| Ways of coping – accepting responsibility | 43 ± 19 | 44 ± 18 | 1 (1·00, 1·01) | 0·479 |

| Ways of coping – escape-avoidance | 22 ± 14 | 27 ± 16 | 1·02 (1·01, 1·03) | <0·001 |

| Ways of coping – planful problem-solving | 59 ± 16 | 55 ± 15 | 0·99 (0·98, 0·99) | <0·001 |

| Ways of coping – positive reappraisal | 55 ± 17 | 53 ± 17 | 0·99 (0·98, 1·00) | 0·029 |

| Corwin nursing roles – dissonance score | 5 ± 7 | 5 ± 6·20 | 0·99 (0·97, 1·01) | 0·301 |

| Skills competency | 69 ± 13 | 67 ± 14 | 0·99 (0·98–1·00) | 0·021 |

| Slater competency | 81 ± 14 | 79 ± 15 | 0·99 (0·98, 1·00) | 0·014 |

CWE, conditions for work effectiveness; LEB, leader empowering behaviours.

Because many variables were correlated with each other, a series of stepwise logistic regression models was examined to find a reduced number of variables to explain most of the variability associated with TI. The final model from this analysis included data from each category of variables: age grouping and ‘older not first choice’ and WOCR subscale of seeking social support from individual characteristics, OC and GC subscale of personal feelings from organizational factors and WS subscales of pay and professional status and NS subscale of enjoyment from work environment (Table 3). In this model, older respondents (>30) are 4·5 times more likely to be in the TI group than those who got their first choice. Between work environment and organizational characteristics, higher scores all contribute to the likelihood that the new nurse will not be in the TI group. For a given new nurse this may translate as follows: when two nurses have similar scores on organizational commitment and pay but not on professional status, the nurse with a higher professional status score is less likely to be in the TI group. Thus, while all scores contribute information to TI, these results indicate that their contributions vary according to individual perceptions and their effects may be additive, depending on the score. Finally, increased use of social support coping strategies reflects an increased risk of being in the TI group.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression model for turnover intention

| Turnover intent | OR (95% CI) | se | z | P > |z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age grouping | 0·59 (0·47, 0·74) | 0·117 | −4·5 | <0·0001 |

| Older not first choice | 4·62 (1·87, 11·38) | 0·46 | 3·32 | 0·0009 |

| Organizational commitment | 0·97 (0·95, 0·98) | 0·007 | −4·7 | <0·0001 |

| Work satisfaction – pay | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | 0·005 | −4·42 | <0·0001 |

| Work satisfaction – professional status | 0·95 (0·93, 0·97) | 0·01 | −5·06 | <0·0001 |

| Nurse satisfaction – enjoyment | 0·98 (0·96, 0·99) | 0·009 | −3·01 | 0·0026 |

| Group cohesion – personal feelings | 0·98 (0·97, 0·99) | 0·006 | −3·13 | 0·0017 |

| WOC – seeking social support | 1·02 (1·00, 1·03) | 0·006 | 2·62 | 0·0089 |

Hosmer–Lomeshow goodness of fit χ2 = 10·47, d.f. = 8, P = 0·234, Area under the ROC curve = 0·791.

WOC, ways of coping.

The hospital differences demonstrated on the chi-square test (P = 0·011) did not translate into a statistical difference in employment at 24 months based on the Kaplan–Meier curves (P = 0·422, log rank test). Estimated 24-month employment ranged from 83% to 98% (overall 84%). Hospitals with the largest number of new graduate nurses had TI of 36%, 25% and 39% with 83%, 85% and 83% employed, respectively, at 24 months. The Kaplan–Meier estimates or percent employment at 24 months is 89% for no TI at 6 months and 72% for TI (P = 0·0001, log rank test; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated probability of continued employment based on the Kaplan–Meier survivorship curve.

Discussion

Many variables in this study were selected for their association with TI in previous studies. Thus, the statistically significant associations with TI are not entirely surprising. An inverse relationship between age and turnover was shown in other studies, which were cross-sectional and included all nurse levels (Parasuraman 1989, Fisher et al. 1994, Shields & Ward 2001). Unique to our study was a full range of ages for new nurses entering the profession over a 7-year period, as well as a common residency to ease transition to the wards. The increased likelihood of TI for older new graduate nurses who did not get their choice of nursing unit/ward, however, was unexpected. New nurses with an average age of 22·8 years in Japan were more likely to turnover when dissatisfied with a ward assignment that was not desired (OR = 3·36, P ≤ 0·01; Suzuki et al. 2006). New nurses in comparison to tenured nurses have less vested in their positions when dissatisfied and, therefore, are more likely to leave their job. In our study, older nurses may be more likely than younger persons to have fixed career goals and resign when their goals are not on track.

Seeking social support as a coping strategy increased the odds of being in the TI group. Greater use of this coping strategy may be a new graduate's attempt to deal with the stresses of transition, which may include taking the licensing exam, adjusting to a new job, mastering clinical skills, becoming a healthcare team member and making new friends. Kramer (1974) recognized that support was important for new nurses to endure the stresses of a first job.

In a study of stress experienced by new graduates, Symes et al. (2005) reported that over 58% of respondents were highly stressed when dealing with the pressures of being an inexperienced nurse. In their logistic regression analysis, Suzuki et al. (2006) reported a risk ratio 2·29 (P < 0·01) times greater for turnover of new nurses who indicated a lack of social support from peers. Previously, Hamilton et al. (1989) identified new graduates' need for socialization as critical for their growth and satisfaction in the workplace. Recently, Hayes et al. (2006a) emphasized interaction and good working relationships as necessary for job satisfaction and developing a sense of belonging. Thus, increased seeking social support in our study may reflect failure to obtain the necessary support and/or individual responses to dealing with the many stresses associated with being a new nurse.

Lower scores on skills self-confidence and perceptions of nursing competency also contributed to TI. Because building confidence in competency is key to hospital success in providing quality care (McClure et al. 1983), helping new graduates feel confident in their performance is vital during the first months of employment. Preceptor support, reasonable expectations, praise and opportunities for interaction appear to build new nurse confidence (Hayes et al. 2006b). Almada et al. (2004) reported that after completion of an 11-week facilitated orientation with a preceptor, new graduates expressed high levels of comfort. New graduate turnover decreased after initiation of the programme. Similarly, a 16-week competency-based orientation for new nurses demonstrated favourable results on clinical competence, confidence and comfort in a study by Blanzola et al. (2004). In our study, it appeared that a facilitated residency may not guarantee perceived confidence in competency for all participants at the end of the programme. Various factors may contribute to this finding, such as individual learning pace, a complex unit/ward requiring a lengthy orientation such as intensive care, or insufficient support for confidence building from preceptors or others.

Satisfaction with pay has received a fair amount of attention in the literature, with inconsistent findings (Hayes et al. 2006a). In our study pay referred to the monetary remuneration and fringe benefits received for work; professional status is the overall importance one attributes the job as viewed by self and others. Shields and Ward (2001) found that dissatisfaction with promotion had more impact on intent to leave than pay. They concluded that improving pay would have had limited success without better opportunities. Yin and Yang (2002) confirmed that nurse turnover was related to pay (r = −0·20) in a meta-analysis that investigated causal relationships among individual, organizational and environmental factors. Lum et al. (1998) studied the impact of pay policies on TI of experienced paediatric nurses and found that pay satisfaction had direct and indirect effects on TI. Working 12-hour shifts, having children, and a degree were influential with both direct and indirect effects.

In our study, lower scores for enjoyment in one's job also contributed to TI. Jackson (2005) examined what constitutes a good day for new nurses and identified the themes of ‘doing something well’, ‘feeling that you’ve achieved something’ and ‘getting the work performed’. A study of new graduate nurses in critical care demonstrated that positive precepting experiences and support systems were important for low role conflict and ambiguity (Boyle et al. 1996). Our findings warrant further analysis to determine what factors contribute to diminished enjoyment in one's job for new graduates. Is it related to job complexity, insufficient time or support to accomplish assigned tasks, or a specific work area?

We found that personal feelings about the work group are as important as seeking social support and enjoyment in one's job. In a survey of new graduates within 5 years of graduation Bowles and Candela (2005) determined that support from other staff and the nursing team was second in importance to patient care as reasons for leaving their first position. Thirty percent of respondents left their first position within 1 year and 57% left by 2 years. In another study, a year-long programme to provide social and professional reality integration (SPRING) for new graduates was implemented to meet their needs for support through the first year of transition to practice. The programme participants had less TI at 6 months and increased retention at 12 months when compared with nurses with <1 year of experience who had received the standard orientation (Newhouse et al. 2007). Organizations that value teamwork, cohesiveness and collaboration are more likely to have committed employees. Several researchers have shown that where interaction with others to achieve individual and group goals is encouraged, employees are more committed to the organization. For experienced nurses, job enjoyment improved after a team-building intervention over a 12-month period. Reduced turnover resulted along with improved group cohesion and RN-RN interaction (DiMeglio et al. 2005). Closer analysis of the work group for TI respondents in our study may provide further information on personal feelings.

Lower scores for organizational commitment have been associated with increased turnover or TI in other studies (Arnold & Feldman 1982, Tourangeau & Cranley 2006). In these studies commitment was positively related to job involvement and years in the organization and negatively related to work overload and turnover. These findings are similar to a recent study of new graduate nurses by Cho et al. (2006), who reported that emotional exhaustion influenced organizational commitment negatively. They also found that empowerment contributed positively to work life, which in turn decreased perceptions of emotional exhaustion. Although empowerment did not appear related to TI in our study, its influence on job satisfaction and organizational commitment warrants further analysis. Other studies have shown that leader behaviours and empowerment contribute to organizational commitment (McNeese-Smith 1995, Laschinger et al. 1999, Loke 2001).

Overall with the exception of the age related variables, our multivariate model shows that when new graduate nurses are satisfied with their jobs and pay and feel committed to the organization, the odds of TI decrease (Table 3). These findings are fairly consistent with previous research on nurse turnover. Our results, however, add a new perspective with a more homogeneous sample of entry-level nurses from multiple hospitals. They identify factors that contribute independent information about TI. Also these factors distinguish a new nurse with TI from one without TI 79% of the time. Further unique information about new graduates was the finding that increased use of seeking social support to cope with the transition from student to competent RN was related to TI and that older graduates (>30) are 4·5 times more likely to be in the TI group if they do not get their nursing unit/ward of choice.

Study limitations

After completion of the residency at 22 weeks, experiences of the study participants might have varied greatly. How these experiences influence turnover is limited to the variables studied. Additionally, another variable to measure stress levels during the transition period for new graduates could help to explain further the link between increased seeking social support and TI.

Conclusion

Most of the published research represents cross-sectional studies of heterogeneous nursing samples. The prospective nature of the data in our study, as well as increased homogeneity of the sample, will allow for future analysis to explore how these observed relationships change as nurses' experiences in the clinical setting and their interrelationships with colleagues evolve. In addition, because of the complexity of these data, the proposed conceptual model involving the relationships between the variables should be examined and critiqued through the use of structural equations.

Acknowledgments

Altangerel Manal, MD, MPH, Administrative Analyst, Patient Care Services, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles and Minya Sheng, MS, Data Administrator, Division of Research on Children, Youth and Families, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles for their diligent data management and statistical examination. Patricia A. Cornett, EdD, MS, RN, Sr Vice-President, Curriculum Evaluation and Product Development, Versant Advantage, Inc., Versant™ RN Residency for her review of this manuscript.

Author contributions

PCB, was responsible for the study conception and design and the drafting of the manuscript. PCB, FD and MRW performed the data collection and data analysis. PCB obtained funding and provided administrative support. PCB and FD made critical revisions to the paper. FD and MRW provided statistical expertise. PCB supervised the study.

References

- Aiken L, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Busse R, Clarke H, Giovanetti P, Hunt J, Rafferty AM, Shamian J. Nurses' reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001;20(3):43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(16):1987–1993. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almada P, Carafoli K, Flattery JB, French DA, McNamara M. Improving the retention rate of newly graduated nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2004;20(6):268–273. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold HJ, Feldman DC. A multivariate analysis of the determinants of job turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1982;67(3):350–360. [Google Scholar]

- Beecroft PC, Kunzman LA, Krozek C. RN internship: outcomes of a one-year pilot program. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2001;31(12):575–582. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecroft PC, Kunzman LA, Taylor S, Devenis E, Guzek F. Bridging the gap between school and workplace. Developing a new graduate nurse curriculum. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2004;34(7/8):338–345. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecroft PC, Santner S, Lacy ML, Kunzman LA, Dorey F. New graduate nurses' perceptions of mentoring: six-year programme evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;55(6):736–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanzola C, Lindeman R, King ML. Nurse Internship pathway to clinical comfort, confidence, and competency. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 2004;20(1):27–37. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles C, Candela L. First job experiences of recent RN graduates: improving the work environment. Nevada RNformation. 2005;14(2):16–19. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle DK, Popkess-Vawter S, Taunton RL. Socialization of new graduate nurses in critical care. Heart and Lung. 1996;25(2):141–154. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(96)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi JD, Markham FS, Bounds WT. Factors related to nurse retention and turnover: an updated study. Health Marketing Quarterly. 1998;15(3):25–43. doi: 10.1300/J026v15n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler GE. The source and process of empowerment. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 1992;16(3):65–71. doi: 10.1097/00006216-199201630-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Laschinger HKS, Wong C. Workplace empowerment, work engagement and organizational commitment of new graduate nurses. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership. 2006;19(3):43–60. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2006.18368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin RG, Taves MJ. Some concomitants of bureaucratice and professional conceptions of the nurse role. Nursing Research. 1962;11(4):223–227. doi: 10.1097/00006199-196211040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin LS, Hengstberger-Sims C. New graduate nurse self-concept and retention: a longitudinal study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006;43:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMeglio K, Padula C, Piatek C, Korber S, Barrett A, Ducharme M, Lucas S, Piermont N, Joyal E, DeNichola V, Corry K. Group cohesion and nurse satisfaction. Examination of a team-building approach. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2005;35(3):110–120. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200503000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ML, Hinson N, Deets C. Selected predictors of registered nurses' intent to stay. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;20:950–957. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20050950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Manual, Test Booklet, Scoring Key. Mind Garden, Inc.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DL. Conflict and retention of new graduate nurses. Western Journal Nursing Research. 1992;14(1):78–85. doi: 10.1177/019394599201400106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good LR, Nelson DA. Effects of person-group and intragroup attitude similarity on perceived group attractiveness and cohesiveness: II. Psychological Reports. 1973;33:551–560. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton EM, Murray MK, Lindholm LH, Myers RE. Effects of mentoring on job satisfaction, leadership behaviors, and job retention of new graduate nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development. 1989;5(4):159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassmiller SB, Cozine M. Addressing the nurse shortage to improve the quality of patient care. Health Affairs. 2006;25(1):268–274. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens DS, Aiken LH. Shaping systems to promote desired outcomes: the magnet hospital model. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1999;29(2):14–20. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LJ, O'Brien-Pallas L, Duffield C, Shamian J, Buchan J, Hughes F, Laschinger HKS, North N, Stone PW. Nurse turnover: a literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006a;43(2):237–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes LJ, Orchard CA, Hall LM, Nincic V, O'Brien-Pallas L, Andrews G. Career intentions of nursing students and new nurse graduates: a review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship. 2006b;3(1):1–15. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1281. Article 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw AS, Atwood J. Anticipated turnover: a preventive approach. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1982;4(3):54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw AS, Atwood JR. Nursing staff turnover, stress, and satisfaction: models, measures, and management. Annual Review of Nursing Research. 1983;1:133–153. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-40453-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw AS, Atwood J, Gerber RM, Erickson JR. Testing a theoretical model for job satisfaction and anticipated turnover of nursing staff. Nursing Research. 1986;34(6):384. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll GL, Olsan T, Drew-Cates J, DeVinnery BC, Davies J. Nurses' job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and career intent. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2002;32(5):250–263. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. The experience of a good day: a phenomenological study to explain a good day as experienced by a newly qualified RN. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;42:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins HM. A research tool for measuring perceptions of clinical decision making. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1985;1:221–229. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(85)80159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. Reality Shock. Why Nurses Leave Nursing. St Louis: Mosby; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M, Schmalenberg CE. Job satisfaction and retention: insights for the 90s. Part 2. Nursing. 1991;21(4):51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M, Schmalenberg CE. Essentials of a magnetic work environment. Part 1. Nursing 2004. 2004a;34(6):50–54. doi: 10.1097/00152193-200406000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M, Schmalenberg CE. Essentials of a magnetic work environment. Part 2. Nursing 2004. 2004b;34(7):44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger HKS, Havens DS. Staff nurse work empowerment and perceived control over nursing practice: conditions for work effectiveness. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1996;26(9):27–35. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger HKS, Wong C, McMahon L, Kaufmann C. Leader behavior impact on staff nurse empowerment, job tension, and work effectiveness. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1999;29(5):28–39. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler TG. Measuring the socialization to the professional nursing role. In: Strickland OL, Waltz CF, editors. Measurement of Nursing Outcomes, Vol. 2. Measuring Nursing Performance: Practice, Education, and Research. New York: Springer; 1988. pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Loke JCF. Leadership behaviours: effects on job satisfaction, productivity and organizational commitment. Journal of Nursing Management. 2001;9(4):191–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2001.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, While AE, Barriball L. Job satisfaction among nurses: a literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2005;42:211–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas MD, Atwood JR, Hagaman R. Replication and validation of anticipated turnover model for urban registered nurses. Nursing Research. 1993;42(1):29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum L, Kervin J, Clark K, Reid F, Sirola W. Explaining nursing turnover intent: job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, or organizational commitment? Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1998;19:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- McClure MM, Poulin M, Sovie M, Wandelt M. Magnet Hospitals: Attraction and Retention of Professional Nurses. Kansas City, MO: American Nurses Association; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- McNeese-Smith D. Job satisfaction, productivity, and organizational commitment. The result of leadership. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1995;25(9):17–26. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeese-Smith DK. A content analysis of staff nurse descriptions of job satisfaction and dissatisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(6):1332–1341. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowday RT, Steers RM, Porter LW. The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1979;14:224–247. [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse RP, Hoffman JJ, Suflita J, Hairston DP. Evaluating an innovative program to improve new nurse graduate socialization into the acute healthcare setting. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2007;31(1):50–60. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien-Pallas L, Griffin P, Shamian J, Buchan J, Duffield C, Hughes F, Laschinger HKS, North N, Stone PW. The impact of nurse turnover on patient, nurse, and system outcomes: a pilot study and focus for multicenter international study. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice. 2006;7(3):169–179. doi: 10.1177/1527154406291936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman S. Nursing turnover: an integrated model. Research in Nursing and Health. 1989;12:267–277. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770120409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabiston JA, Laschinger HKS. Staff nurse work empowerment and perceived autonomy. Tesing Kanter's theory of structured power in organizations. Journal of Nursing Administration. 1995;25(9):42–50. doi: 10.1097/00005110-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutzenhofer KK. Measuring professional autonomy in nurses. In: Strickland OL, Waltz CF, editors. Measurement of Nursing Outcomes, Vol. 2. Measuring Nursing Performance: Practice, Education, and Research. New York: Springer; 1988. pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shields MA, Ward M. Improving nurse retention in the National Health Service in England: the impact of job satisfaction on intentions to quit. Journal of Health Economics. 2001;20:677–701. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C. Department of Management. Indianapolis: PhD Indiana University; 1994. Effects of leader empowerment behaviors and followers’ personal control, voice, and self-efficacy on in-role and extra-role performance: an extension and empirical test of conger and Kanungo's Empowerment Process Model. [Google Scholar]

- Stone PW, Tourangeau AE, Duffield CM, Hughes F, Jones CB, O’Brien-Pallas L, Shamian J. Evidence of nurse working conditions: a global perspective. Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice. 2003;4(2):120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki E, Itomine I, Kanoya Y, Katsuki T, Horii S, Sato C. Factors affecting rapid turnover of novice nurses in university hospitals. Journal of Occupational Health. 2006;48:49–61. doi: 10.1539/joh.48.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symes L, Krepper KR, Lindy C, Byrd MN, Jacobus C, Throckmorton T. Stressful life events among new nurses: implications for retaining new graduates. Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2005;29(3):292–296. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau AE, Cranley LA. Nurse intention to remain employed: understanding and strengthening determinants. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;55(4):497–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng H-M, Ketefian S, Redman RW. Relationship of nurses' assessment of organizational culture, job satisfaction, and patient satisfaction with nursing care. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2002;39(1):79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandelt MA, Stewart DS. Slater Nursing Competencies Rating Scale. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Yin J-CT, Yang K-PA. Nursing turnover in Taiwan: a meta-analysis of related factors. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2002;39:573–581. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]