Abstract

To understand the elevated smoking rates among psychiatric patients, we investigated whether psychiatric diagnosis, illness severity, and other substance use predicted smoking status in a diverse sample (N = 2774 consecutive admissions) of psychiatric outpatients. Results indicated that 61% of patients smoked daily, and that 18% smoked heavily (more than one pack per day). Current smoking was related to psychiatric diagnosis and illness severity, as well as caffeine consumption, and drug and alcohol abuse. Diagnoses of bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia were independently related to smoking status, an association that was most pronounced among persons treated at clinics serving more impaired patients. Thus, psychiatric diagnosis and illness severity contribute to increased risk for smoking, even after controlling for other substance use. Cessation programs are needed to reduce tobacco-related morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Smoking, psychiatric illness, substance abuse, screening, health promotion

Recent findings from a national probability sample indicate that people with a mental illness are twice as likely as non-psychiatric controls to smoke, and may comprise as much as half of the tobacco market in the US (Lasser et al., 2000). Similarly, estimates of smoking prevalence among individuals receiving psychiatric care indicate that between 50% to 80% psychiatric patients smoke (de Leon et al., 1995; Goff, Henderson, & Amico, 1992; Hughes, Hatsukami, Mitchell, & Dahlgren, 1986), compared to 24% of the general population (CDC, 2001). Such findings suggest that the mentally ill may bear a disproportionate share of the public health burden associated with smoking-related illnesses (Bruce, Leaf, Rozal, Florio, & Hoff, 1994), and underscore the importance of clarifying the relationship between psychiatric illnesses and smoking.

Prior research has emphasized empirical investigations of patients with specific disorders, including major depression (Breslau, Peterson, Schultz, Chilcoat, & Andreski, 1998; Glassman et al., 1990), schizophrenia (Goff et al., 1992; Kelly & McCreadie, 1999), bipolar disorder (Corvin et al., 2001) and anxiety disorders (Breslau, Kilbey, & Andreski, 1991; Johnson et al., 2000). Studies that focus on distinct patient populations provide little information regarding common risk factors for smoking across the full spectrum of major psychiatric disorders. For example, some studies confirm that indices of illness severity and distress correlate with smoking status among psychiatric patients (Breslau, Kilbey, & Andreski, 1993; Hall et al., 1995). At the same time, research indicates that nicotine may be particularly effective in relieving negative symptoms associated with schizophrenia relative to other psychiatric symptoms (Dalack, Healy, & Meador-Woodruff, 1998; Lyon, 1999), suggesting that smoking related to “self-medication” may be more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared to other disorders. Consistent with this hypothesis, several small sample studies that include patients from multiple diagnostic groupings point to higher smoking rates among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared to other diagnostic subgroups (de Leon et al., 1995; Diwan, Castine, Pomerleau, Meador-Woodruff, & Dalack, 1998; Hughes et al., 1986).

A complicating factor is that alcohol and drug use disorders are more prevalent among persons with a psychiatric illness (Kessler et al., 1997), and co-occurring substance abuse is a strong predictor of smoking status among psychiatric patients (Farrell et al., 2001; Glassman et al., 1990). Moreover, caffeine use is highly prevalent among psychiatric patients (Goff et al., 1992), and individuals who smoke report higher levels of caffeine intake (Istvan & Matarazzo, 1984). Because both substance abuse and psychopathology have been linked to elevated rates of smoking among psychiatric patients, an important unanswered question is whether psychiatric diagnosis and other indices of psychopathology are independently associated with smoking after the effects of substance abuse are controlled. Prior research addressing this question has yielded mixed results (Black, Zimmerman, & Coryell, 1999; Breslau et al., 1991; Glassman et al., 1990), and the ability to generalize broadly from these studies is limited because of the exclusion of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

The present study improves upon prior research by drawing from a large, heterogeneous sample of psychiatric outpatients to clarify the degree to which psychiatric diagnosis, illness severity, and concurrent substance abuse independently contribute to smoking status. Medical records from consecutive outpatients receiving psychiatric care from two, not-for-profit hospitals were reviewed to obtain smoking and other health behavior data, along with psychiatric and demographic characteristics. Our primary objectives were (a) to provide prevalence estimates of current smoking in a large, heterogeneous sample of persons receiving outpatient psychiatric care; and (b) to characterize the independent contributions of patient characteristics, including psychiatric diagnosis, illness severity, and concurrent substance abuse, as risk factors for smoking. Because prior research suggests that heavy smokers have more difficulty with smoking cessation (Breslau & Peterson, 1996), our outcome analyses focus on characterizing patterns and correlates of current smoking, as well as heavy smoking as indicated by consumption of greater than one pack of cigarettes per day. We hypothesized that smoking status would be independently associated with greater illness severity, heavy caffeine use, and elevated risk for substance use disorders. Based on prior research, we also hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses would be at elevated risk for smoking even after controlling for current substance use.

Method

Participants

The sample was drawn from 2,906 consecutive outpatients seen for an initial evaluation or ongoing care at seven hospital-based outpatient psychiatric clinics in Syracuse, New York. Patients with complete chart data, including psychiatric diagnosis, current smoking and substance use data, and demographic information, were included in the present sample. The sample consisted of 1482 women and 1292 men (N = 2774) with complete data. The mean age of participants was 39 years (SD = 11.4); the ethnic composition consisted of 77% White, 15% African-American, and 8% “other.” A minority of participants were married (13%). Psychiatric diagnoses recorded in the charts included 27% with depressive disorder, 23% schizophrenia, 11% bipolar disorder, 11% schizoaffective disorder, 11% other, 10% adjustment disorder, and 8% anxiety disorder. Among patients classified as “other,” common diagnoses included depressive or mood disorders not otherwise specified, assorted personality disorders, and mood disorders due to a medical condition.

Procedures

Consecutive patients seeking outpatient psychiatric care at either hospital completed a screening interview that assessed health behavior and substance use as part of standard care. Data were obtained from chart records with the approval of the Institutional Review Boards at both hospitals.

Measures

Demographic information

Participant age, marital status, ethnicity, and gender were obtained.

Smoking status

To assess current smoking, patients were asked “How many cigarettes do you smoke per day?” Primary outcome measures consisted of a dichotomous index of any current daily smoking (yes vs. no) as well as a measure of heavy smoking. Heavy smokers were defined as those reporting smoking greater than 1 pack of cigarettes per day (i.e., >20 cigarettes), as suggested by prior research (Anda et al., 1990; de Leon et al., 1995).

Caffeine consumption

Caffeine consumption was assessed with three questions requiring patients to indicate the average number of beverages consumed per day that were likely to contain caffeine, including 8 oz. servings of coffee, 8 oz. servings of tea, and 12 oz. servings of soda. Tea and soda consumption were converted into 8 oz. “coffee cup equivalents” using a multiplier of .30 to approximate the amount of caffeine found in tea and soda relative to a typical cup of brewed coffee. Values were then summed to yield an index of daily caffeine consumption. Patients’ caffeine use was recoded into a three level variable consisting of patients consuming two or fewer caffinated beverages per day (49%), those consuming 3–5 beverages per day (31%), and those consuming more than 5 beverages per day (20%).

Psychiatric diagnosis

Primary Axis I diagnosis was determined by an attending psychiatrist during an intake assessment, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). A subset of patients (N = 464) completed a portion of the Structured Clinical Interviews for the DSM-IV (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) to assess for the presence of major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia spectrum disorders, as part of the requirements for participation in a randomized clinical trial (reported elsewhere; Carey et al., 2002; Vanable, Carey, Carey, & Maisto, 2002). Of the 464 SCID interviews, 203 were administered by one of three doctoral level clinical psychologists, and 261 were administered by one of four advanced graduate students in clinical psychology who worked under the supervision of a doctoral level psychologist. Comparison of the SCID diagnoses with the intake diagnoses used in this study indicated good agreement for these diagnostic subgroups (exact agreement = 73%; Kappa coefficient = .63).

Illness severity

Because level of functioning data were not available for individual patients, we created a proxy indicator by calculating an average Global Assessment of Functioning score (GAF) for each of the seven outpatient clinics that served as research sites. The average GAF score for the seven clinic sites was 46.4 (SD = 4.3, median = 47.9), indicating a high degree of psychopathology in the sample as a whole. Based on use of the median GAF score as a cut-point, four clinic sites were coded as serving “higher severity” patients and three clinic sites were coded as serving “lower severity” patients. All patients from a given clinic were assigned its designated GAF rating of higher or lower severity.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993)

The AUDIT is a validated 10-item self-report instrument developed to identify individuals at risk for alcohol problems or who are already experiencing such problems (Bohn, Babor, & Kranzler, 1995). Summary scores range from 0 – 40, and prior research with psychiatric patients indicates that a cut point of greater than 7 maximizes sensitivity and specificity scores for identifying those with an alcohol-related disorder (Maisto, Carey, Carey, Gordon, & Gleason, 2000). Coefficient alpha in the current sample was .90.

Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10)

The DAST-10 is a validated 10 item screening test developed to identify drug-use related problems in the previous year (Cocco & Carey, 1998). A single summary score reflects the number of drug abuse items endorsed. Sensitivity and specificity with this population are optimized with a score of greater than 2 (Maisto et al., 2000). Coefficient alpha in the current sample was .91.

Overview of analyses

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and alpha was set at .05. Outcome analyses sought to identify correlates of (a) current smoking and (b) heavy smoking (i.e., more than one pack of cigarettes per day). First, chi-square analyses are reported to indicate the bivariate association between smoking status and patient characteristics. Next, multivariate logistic regression analyses are reported to characterize the independent contributions of patient diagnosis, illness severity, and substance use to the prediction of smoking status. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented to indicate the ratio of the odds of smoking for persons with a given risk factor relative to those without the risk factor. Categorical variables with more than two levels (e.g., psychiatric diagnosis) were recoded into dichotomous indicators using standard dummy coding procedures. Patients diagnosed with an adjustment disorder were presumed to have the least disabling diagnosis; therefore they were coded as the reference category for the multivariate analyses. Thus, smoking rates among patients within each diagnostic category were contrasted with rates reported by adjustment disorder patients, a group that approximates a non-psychiatric comparison group. This analytic approach parallels that of other investigations of smoking and mental illness (Hughes et al., 1986; Lasser et al., 2000), where smoking rates for major Axis I diagnoses are typically contrasted with rates reported by a non-psychiatric comparison group. Exploratory analyses also sought to identify potential moderator variables that would indicate that risk factors for smoking varied across different patient subgroups. For these analyses, the main effects for each model were entered into the logistic regression equation in the first step, and two-way interaction terms were entered in the second step to determine whether they contributed to the overall model. All possible two-way interaction combinations were tested in separate models. Significant interactions were characterized further through subgroup analyses.

Results

The overall prevalence of current smoking was 61% and of heavy smoking, was 18%. Current smokers reported consuming an average of 21.6 cigarettes per day (SD = 14.4). Seventy one percent of current smokers reported smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day.

The demographic characteristics of smokers and heavy smokers are shown in Table 1. Current smoking was more common among male respondents and among those in the middle age categories (30–46 years old) relative to patients under the age of 30 or over the age of 46. No other demographic differences emerged in comparisons of smokers vs. non-smokers. Heavy smokers were more likely to be male, older, and Caucasian. Marital status was unrelated to current smoking habits.

Table 1.

Percentage of Psychiatric Outpatients who are Current Smokers and Heavy Smokers, by Demographic Characteristics, Psychiatric Diagnosis, Psychopathology Level, and Risk for Substance Abuse (N = 2774)

| Patients Reporting Current Smoking |

Patients Reporting Heavy Smoking1 |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N | % | χ2 | df | p < | N | % | χ2 | df | p < |

| Demographic variables | ||||||||||

| Age | 28.96 | 3 | 0.0001 | 25.20 | 3 | .0001 | ||||

| 18 – 29 (n=638) | 372 | 58 | 78 | 12 | ||||||

| 30 – 38 (n=725) | 477 | 66 | 134 | 19 | ||||||

| 39 – 46 (n=699) | 454 | 65 | 158 | 23 | ||||||

| > 46 (n=712) | 383 | 54 | 140 | 20 | ||||||

| Gender | 30.41 | 1 | 0.0001 | 16.60 | 1 | .0001 | ||||

| Female (n=1482) | 830 | 56 | 231 | 16 | ||||||

| Male (n=1292) | 856 | 66 | 279 | 22 | ||||||

| Ethnicity | 4.72 | 1 | ns | 37.17 | 2 | .0001 | ||||

| White (n=2123) | 1301 | 61 | 443 | 21 | ||||||

| Black (n=427) | 264 | 62 | 43 | 10 | ||||||

| Other (n=224) | 121 | 54 | 24 | 11 | ||||||

| Marital status | 0.39 | 1 | ns | 0.11 | 1 | ns | ||||

| Not married (n=2408) | 1469 | 61 | 445 | 19 | ||||||

| Married (n=366) | 217 | 59 | 65 | 18 | ||||||

| Substance use variables | ||||||||||

| AUDIT risk classification | 86.98 | 1 | .0001 | 6.25 | 1 | .05 | ||||

| Low risk (≤7; n=2206) | 1244 | 56 | 385 | 18 | ||||||

| High risk (>7; n=568) | 442 | 78 | 125 | 22 | ||||||

| DAST risk classification | 83.35 | 1 | .0001 | 0.77 | 1 | ns | ||||

| Low risk (≤2; n=2415) | 1389 | 58 | 438 | 18 | ||||||

| High risk (>2; n=359) | 297 | 83 | 72 | 20 | ||||||

| Caffeine Use | 259.09 | 2 | .0001 | 262.42 | 2 | .0001 | ||||

| Light (≤2 servings; n=1355) | 622 | 46 | 118 | 9 | ||||||

| Moderate (3–5 servings; n=869) | 619 | 71 | 170 | 20 | ||||||

| Heavy (>5 servings; n=550) | 445 | 81 | 222 | 40 | ||||||

| Psychiatric variables | ||||||||||

| Diagnosis | 21.92 | 6 | .005 | 39.70 | 6 | .0001 | ||||

| Adjustment disorder (n=279) | 143 | 51 | 35 | 13 | ||||||

| Anxiety disorder (n=219) | 123 | 56 | 35 | 16 | ||||||

| Depression (n=755) | 449 | 60 | 108 | 14 | ||||||

| Bipolar (n=293) | 192 | 66 | 65 | 22 | ||||||

| Schizoaffective (n=296) | 198 | 67 | 79 | 27 | ||||||

| Schizophrenia (n=623) | 393 | 63 | 139 | 22 | ||||||

| Other (n=309) | 188 | 61 | 49 | 16 | ||||||

| Illness severity | 15.22 | 1 | .0001 | 14.02 | 1 | 0.0001 | ||||

| Lower severity (n=1714) | 993 | 58 | 278 | 16 | ||||||

| Higher severity (n=1060) | 693 | 65 | 232 | 22 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 1686 | 61 | 510 | 18 | ||||||

Note: Percentages indicate the proportion of participants within each stratification classified as a current and heavy smoker.

Heavy smokers were defined as individuals who reported smoking greater than one pack per day.

Smoking Status as Function of Risk for Substance Use Disorders and Caffeine Consumption

Twenty-one percent of participants (n = 568) were at risk for alcohol dependence based on AUDIT scores, and 13% (n = 359) were at risk for drug dependence based on their score on the DAST. A total of 8% (n = 217) were at elevated risk for both alcohol and drug dependence. Bivariate associations between smoking status and substance use variables are shown in Table 1. As predicted, patients at elevated risk for alcohol and drug dependence reported higher rates of current smoking (78% and 83%, respectively) compared to those classified as low risk (56% and 58%; see Table 1). Similarly, patients with elevated AUDIT scores reported higher rates of heavy smoking (22%) compared to those with low AUDIT scores (18%). Rates of heavy smoking did not differ as a function of risk for drug dependence based on the DAST. Among patients at elevated risk for both drug and alcohol dependence (not tabled), 84% reported current smoking compared to 59% among other respondents, χ2 (1) = 54.79, p < .0001.

A large majority (86%) reported consumption of beverages likely to contain caffeine (M = 3.64 servings per day; SD = 5.96). Daily caffeine consumption was strongly related to current smoking status, with 81% of patients reporting heavy caffeine consumption being classified as current smokers compared to 46% among light caffeine users (see Table 1). Similarly, those reporting heavy caffeine use were much more likely to be heavy smokers (40%) compared to those reporting moderate (20%) and light (9%) caffeine intake.

Psychiatric Characteristics of Smokers versus Non-Smokers

Bivariate analyses revealed significant differences in smoking rates as a function of diagnostic classification (see Table 1). Patients with schizoaffective disorder reported the highest smoking rates (67%), followed by patients with bipolar disorder (66%), schizophrenia (63%), “other” (61%), depression (60%), anxiety disorders (56%), and adjustment disorders (51%). Subgroup analyses revealed that patients with schizoaffective disorder reported higher smoking rates (67%) compared to all other diagnostic subgroups combined (60%), χ2 (1) = 5.20, p < .03, and patients with an adjustment disorder were significantly less likely to report current smoking compared to all other diagnostic groups combined (51% vs 62%, χ2 (1) = 11.80, p < .005).

Diagnostic differences also emerged for analyses of heavy smoking (see Table 1). Patients with schizoaffective disorder reported the highest rate of heavy smoking (27%), followed by patients with bipolar disorder (22%) and schizophrenia (22%). Rates of heavy smoking ranged from 13% to 16% among patients with adjustment disorders, depression, anxiety disorders, or “other” diagnoses. Follow-up comparisons indicated that a higher percentage of patients with schizoaffective disorder (27% vs 17%, χ2 (1) = 15.23, p < .0001), and schizophrenia (22% vs 17%, χ2 (1) = 8.26, p < .005), reported heavy smoking compared to other diagnostic subgroups combined. A lower percentage of patients with depression (14% vs 20%, χ2 (1) = 11.51, p < .005), and adjustment disorder (13% vs 19%, χ2 (1) = 7.05, p < .01), reported heavy smoking compared to other diagnostic subgroups combined.

In terms of illness severity, 38% (n = 1060) were classified as receiving care from a clinic serving more severely impaired patients. Significant bivariate associations between illness severity and smoking status were observed, indicating higher smoking levels among patients receiving care from clinics serving more severely impaired patients. Rates of current and heavy smoking were 65% and 22% respectively among patients classified as “higher severity,” compared to rates of 58% and 16% among “lower severity” patients.

Multivariate Analyses

Although psychiatric diagnosis, illness severity, and substance use were all significantly associated with smoking status, bivariate analyses do not adjust for collinearity across predictor variables. To characterize the independent contributions of patient diagnosis, illness severity, and substance use as predictors of smoking status, two multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted in which all predictor variables were entered simultaneously. The pattern of findings was largely consistent with that which was observed in the bivariate analyses. As shown in Table 2, risk for drug and alcohol dependence, as well as current caffeine consumption were all independent predictors of current smoking in the multivariate model. With adjustment disorder as the reference group, all diagnoses except “other” emerged as significant correlates of current smoking. Finally, the multivariate analysis showed that illness severity was a predictor of current smoking at trend level (p < .06), with patients in the high severity group being at increased risk for smoking relative to those in the lower severity group.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analyses Predicting Current and Heavy Smoker Status (N = 2774)

| Current Smoker |

Heavy Smoker1 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | Wald χ2 | p < | AOR2 | 95% CI | Wald χ2 | p < | AOR2 | 95% CI |

| Substance Use Variables | ||||||||

| AUDIT | ||||||||

| Low risk | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | ||||

| High risk | 19.89 | .0001 | 1.74 | 1.37–2.22 | 1.45 | ns | 1.18 | .90–1.54 |

| DAST | ||||||||

| Low risk | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | ||||

| High risk | 35.75 | .0001 | 2.63 | 1.92–3.62 | .07 | ns | 1.04 | .75–1.45 |

| Caffeine use | ||||||||

| Light | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | ||||

| Moderate | 129.36 | .0001 | 3.05 | 2.52–3.70 | 38.08 | .0001 | 2.26 | 1.75–2.93 |

| Heavy | 152.25 | .0001 | 4.82 | 3.75–6.18 | 182.89 | .0001 | 6.15 | 4.73–8.00 |

| Psychiatric Variables | ||||||||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Adjustment disorder | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | ||||

| Anxiety disorder | 4.15 | .05 | 1.50 | 1.02–2.21 | 1.29 | ns | 1.36 | .80–2.32 |

| Depression | 5.05 | .05 | 1.42 | 1.05–1.92 | .05 | ns | 1.05 | .68–1.62 |

| Bipolar | 7.27 | .01 | 1.67 | 1.15–2.43 | 3.93 | .05 | 1.63 | 1.01–2.64 |

| Schizoaffective | 6.82 | .01 | 1.66 | 1.13–2.42 | 6.96 | .01 | 1.91 | 1.18–3.07 |

| Schizophrenia | 5.28 | .05 | 1.47 | 1.06–2.04 | 4.10 | .05 | 1.58 | 1.02–2.46 |

| Other | 2.59 | ns | 1.35 | .94–1.93 | .26 | ns | 1.14 | .69–1.87 |

| Illness severity | ||||||||

| Low severity | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | ||||

| High severity | 3.80 | .06 | 1.21 | 1.0–1.45 | 1.78 | ns | 1.16 | .93–1.46 |

Note: AOR = Adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ns = non-significant.

Heavy smokers were defined as individuals who reported smoking greater than one pack per day.

The AOR reflects the unique effect of each predictor, adjusting for the effects of the other predictors in the model. Regression models are also adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, and marital status (not shown).

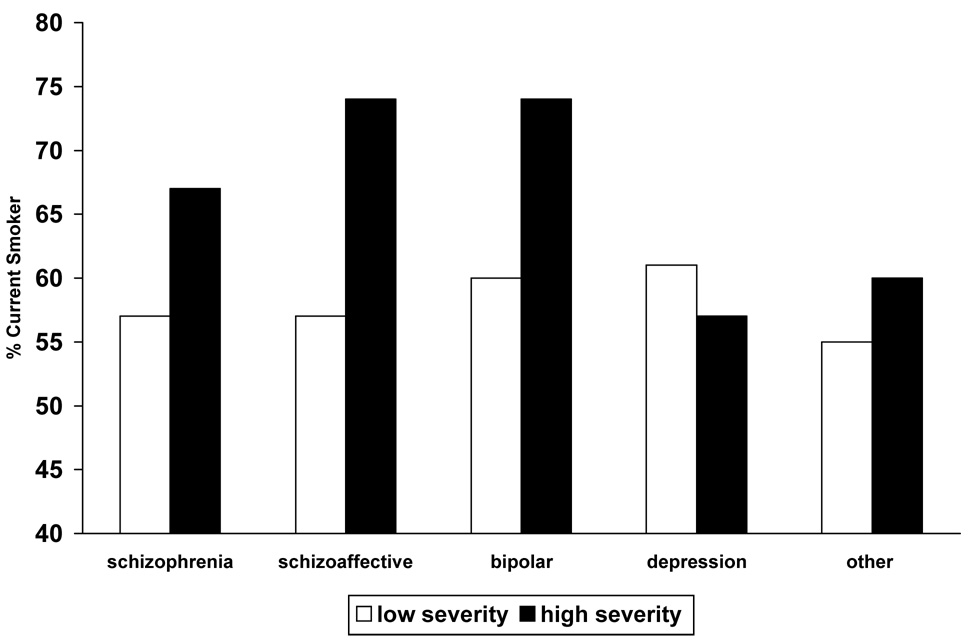

However, analyses to determine whether risk factors for current smoking varied across different patient subgroups revealed that the main effects for diagnosis and illness severity were qualified by a significant diagnosis-by-illness severity interaction that contributed to the prediction of smoking beyond that which was explained by all main effects (Δ Model χ2 = 20.68, p < .005). To evaluate this interaction, we conducted separate logistic regression analyses for patients in the low versus high illness severity group. Psychiatric diagnosis was not a significant risk factor for smoking among patients in the low illness severity subgroup. Among patients in the high illness severity group, diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia emerged as significant risk factors for smoking relative to other diagnoses (Wald χ2 = 10.48, AOR = 1.61, CI = 1.21 – 2.14, p < .005). This interaction is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows smoking rates as a function of illness severity and diagnosis. There were no other significant two-way interactions for analyses of current smoking status.

Figure 1. Smoking Status as a Function of Psychiatric Diagnosis and Illness Severity Classification.

Note: Data for patients with adjustment and anxiety disorders are collapsed into the “other” classification because of small cell sizes (<20) among patients in the high severity group.

Table 2 also shows multivariate predictors of heavy smoking. Caffeine use remained a strong predictor of heavy smoking in the multivariate model, but the other substance use variables did not contribute to the prediction of heavy smoking. Psychiatric diagnosis also was independently associated with heavy smoking. With adjustment disorder as the reference group, patients with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia were more likely to report heavy smoking. Neither the illness severity indicator nor the diagnosis-by-illness severity interaction predicted heavy smoking, and no other significant interactions emerged in multivariate analyses.

Discussion

This research used a large sample to characterize common risk factors for smoking among patients representing the full spectrum of major psychiatric disorders. The prevalence of current smoking observed in this sample was 61%, a rate that is 2.5 times greater than the 24% rate that is estimated for all adults living in the United States (CDC, 2001). We observed considerable variability in smoking rates across different psychiatric diagnoses. Indeed, rates of heavy smoking among patients with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders were almost double the rates reported by patients with adjustment, anxiety and depressive disorders. Although smoking rates in the general population declined substantially prior to the 1990s and have remained relatively stable in the last decade, the smoking prevalence estimates reported here actually exceed those observed in an earlier study of psychiatric outpatients (Hughes et al., 1986), as well as the rates reported in a population-based sample of persons with a mental illness (Lasser et al., 2000). These findings suggest that public health campaigns, smoking cessation programs, and policy changes that target the general population have had little effect on the smoking habits of persons living with mental illness.

As predicted, patients at risk for drug and alcohol dependence, as well as those reporting heavy caffeine consumption, reported substantially elevated rates of smoking relative to others in the sample. The high co-occurrence of smoking and other substance use (including caffeine consumption) suggests considerable co-variation of risk across these substance use behaviors. Nonetheless, even after controlling for the effects of substance use, diagnoses of schizoaffective, schizophrenic, and bipolar disorder emerged as risk factors for smoking, an effect that was most pronounced among people receiving care from clinics serving more severely impaired patients. Thus, factors related to illness type and severity appear to contribute to risk for smoking beyond that which is explained by the presence of comorbid substance use disorders.

Prior research involving smaller samples of patients in treatment indicate higher rates of smoking among schizophrenic patients relative to other diagnostic groups (de Leon et al., 1995; Hughes et al., 1986), a finding that suggests increased vulnerability to smoking among patients seeking relief for symptoms associated with a psychotic disorder (Dalack et al., 1998). On this basis, we had hypothesized that patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders would report the highest rates of smoking relative to other patient subgroups. This prediction was partially confirmed: Patients with schizoaffective disorder reported the highest rates of smoking and heavy smoking compared to all other diagnostic groups. However, smoking rates among patients with bipolar disorder were also elevated relative to other diagnostic subgroups, and did not differ appreciably from those with schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia. Further research can help to clarify the extent to which elevated rates of smoking among patients with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders are due to the presence of psychosis, the fact that these disorders simply cause more chronic distress and functional impairment relative to other psychiatric conditions, or other explanations.

The clearest differences in smoking rates across diagnostic subgroups emerged among patients receiving care from clinics serving more severely impaired patients, where patients with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia reported substantially elevated rates of smoking relative to other patients. In contrast, among patients classified as “lower severity” on the basis of their clinic assignment, rates of smoking were equivalent across the different diagnostic subgroups. Although preliminary in nature, these findings suggest that elevated risk for smoking among patients with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders emerges primarily among patients with the most severe or debilitating forms of these illnesses. These observations could be tested more definitively in studies that include more precise measures of illness severity.

Major strengths of this study include the use of a large, representative sample of patients receiving ongoing care, the use of multivariate analyses to determine the independent contributions of relevant predictor variables, the use of psychometrically validated measures, and our focus on identification of risk factors for both current and heavy smoking. The primary limitation of this study was that diagnostic classification was based on chart data from an initial intake interview rather than a validated structured interview. In addition, our use of average GAF scores from each clinic site as a means of categorizing patients as “lower” vs. “higher” functioning provided only an approximation of illness severity. Findings concerning the interactive effects of illness severity and diagnosis require replication with standardized measures of diagnosis and illness severity. We note as well that archival data did not include information concerning patients’ socio-economic status and education, factors that may also contribute to high rates of smoking among psychiatric patients. Finally, we were also not able to examine the contribution of multiple psychiatric diagnoses to smoking (included Axis II diagnoses), a question that should be pursued in future research.

Available evidence suggests that smoking cessation is more challenging for patients experiencing psychiatric illness compared to the general population (Addington, el-Guebaly, Campbell, Hodgins, & Addington, 1998; Glassman et al., 1993). Indeed, given the range of challenges faced by persons with severe mental illness, some providers may be reluctant to encourage their patients to stop smoking, fearing that smoking cessation and nicotine withdrawal may exacerbate psychiatric symptoms. However, such reluctance may be shortsighted given the clear health hazards associated with smoking and the link between smoking and reduced life span among persons with mental illness (Bruce et al., 1994). More intensive research efforts should be directed toward the development of innovative and tailored approaches to smoking cessation to meet the needs of persons with mental illness.

Author Note

Peter A. Vanable, Michael P. Carey, Kate B. Carey, and Stephen A. Maisto, Center for Health and Behavior and Department of Psychology, Syracuse University.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01-MH54929. The authors thank Brian Borsari, Susan Collins, Christopher Correia, Lauren Durant, Julie Fuller, John Harkulich, JulieAnn Hartley, Vardit Konsens, Dan Neal, Teal Pedlow, Mary Beth Pray, Daniel Purnine, Kerstin Schroder, Jeffrey Simons, Lance Weinhardt, Adrienne Williams, Emily Wright, and Denise Zona for their assistance with the project.

References

- Addington J, el-Guebaly N, Campbell W, Hodgins DC, Addington D. Smoking cessation treatment for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:974–976. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington PL. Depression and the dynamics of smoking. A national perspective. JAMA. 1990;264:1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Zimmerman M, Coryell WH. Cigarette smoking and psychiatric disorder in a community sample. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;11:129–136. doi: 10.1023/a:1022355826450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn MJ, Babor TF, Kranzler HR. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation of a screening instrument for use in medical settings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:423–432. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey M, Andreski P. Nicotine dependence, major depression, and anxiety in young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:1069–1074. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Vulnerability to psychopathology in nicotine-dependent smokers: an epidemiologic study of young adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:941–946. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL. Smoking cessation in young adults: age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:214–220. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR, Chilcoat HD, Andreski P. Major depression and stages of smoking. A longitudinal investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, Rozal GP, Florio L, Hoff RA. Psychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:716–721. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SP, Gordon CM, Schroeder, Vanable PA. Reducing HIV risk behavior among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. 2002 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Cigarette Smoking among Adults -- United States, 1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2001;50:869–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco KM, Carey KB. Psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test in psychiatric outpatients. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:408–414. [Google Scholar]

- Corvin A, O'Mahony E, O'Regan M, Comerford C, O'Connell R, Craddock N, Gill M. Cigarette smoking and psychotic symptoms in bipolar affective disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:35–38. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalack GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1490–1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon J, Dadvand M, Canuso C, White AO, Stanilla JK, Simpson GM. Schizophrenia and smoking: an epidemiological survey in a state hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:453–455. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan A, Castine M, Pomerleau CS, Meador-Woodruff JH, Dalack GW. Differential prevalence of cigarette smoking in patients with schizophrenic vs mood disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 1998;33:113–118. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Howes S, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Jenkins R, Lewis G, Marsden J, Taylor C, Meltzer H. Nicotine, alcohol and drug dependence and psychiatric comorbidity: Results of a national household survey. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:432–437. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.5.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MG, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV--patient version (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Covey LS, Dalack GW, Stetner F, Rivelli SK, Fleiss J, Cooper TB. Smoking cessation, clonidine, and vulnerability to nicotine among dependent smokers. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1993;54:670–679. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. JAMA. 1990;264:1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Henderson DC, Amico E. Cigarette smoking in schizophrenia: relationship to psychopathology and medication side effects. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:1189–1194. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RG, Duhamel M, McClanahan R, Miles G, Nason C, Rosen S, Schiller P, Tao-Yonenaga L, Hall SM. Level of functioning, severity of illness, and smoking status among chronic psychiatric patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1995;183:468–471. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami DK, Mitchell JE, Dahlgren LA. Prevalence of smoking among psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143:993–997. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istvan J, Matarazzo JD. Tobacco, Alcohol and Caffeine Use: a review of their interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;905:301–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. 2000;284:2348–2351. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, McCreadie RG. Smoking habits, current symptoms, and premorbid characteristics of schizophrenic patients in Nithsdale, Scotland. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1751–1757. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon ER. A review of the effects of nicotine on schizophrenia and antipsychotic medications. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1346–1350. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.10.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Gleason JR. Use of the AUDIT and the DAST-10 to identify alcohol and drug use disorders among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:186–192. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Predictors of participation and attrition in a health promotion study involving psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:362–368. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]