Abstract

The GoLoco motif is a short Gα-binding polypeptide sequence. It is often found in proteins that regulate cell-surface receptor signaling, such as RGS12, as well as in proteins that regulate mitotic spindle orientation and force generation during cell division, such as GPSM2/LGN. Here, we describe a high-throughput fluorescence polarization (FP) assay using fluorophore-labeled GoLoco motif peptides for identifying inhibitors of the GoLoco motif interaction with the G-protein alpha subunit Gαi1. The assay exhibits considerable stability over time and is tolerant to DMSO up to 5%. The Z′-factors for robustness of the GPSM2 and RGS12 GoLoco motif assays in a 96-well plate format were determined to be 0.81 and 0.84, respectively; the latter assay was run in a 384-well plate format and produced a Z′-factor of 0.80. To determine the screening factor window (Z-factor) of the RGS12 GoLoco motif screen using a small molecule library, the NCI Diversity Set was screened. The Z-factor was determined to be 0.66, suggesting that this FP assay would perform well when developed for 1,536-well format and scaled up to larger libraries. We then miniaturized to a 4 μL final volume a pair of FP assays utilizing fluorescein- (green) and rhodamine- (red) labeled RGS12 GoLoco motif peptides. In a fully-automated run, the Sigma-Aldrich LOPAC1280 collection was screened three times with every library compound being tested over a range of concentrations following the quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) paradigm; excellent assay performance was noted with average Z-factors of 0.84 and 0.66 for the green- and red-label assays, respectively.

Keywords: Fluorescence anisotropy, fluorescence polarization, GoLoco motif, heterotrimeric G-proteins, high-throughput screening

Introduction

Many extracellular signals, including hormones, neurotransmitters, growth factors, and sensory stimuli relay information intracellularly by activation of plasma membrane-bound receptors. The largest class of such receptors is the superfamily of seven transmembrane-domain G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), so named because these cell-surface proteins were originally found to couple extracellular stimuli into intracellular changes via activation of G-protein heterotrimers (Gαβγ) [1]. GPCRs represent a major therapeutic target giving rise to the largest single fraction of the prescription drug market with annual sales of several billion dollars [2]; however, opportunities to develop therapeutics that target the intracellular regulatory machinery controlling the kinetics and duration of GPCR signal transduction have been relatively ignored by comparison.

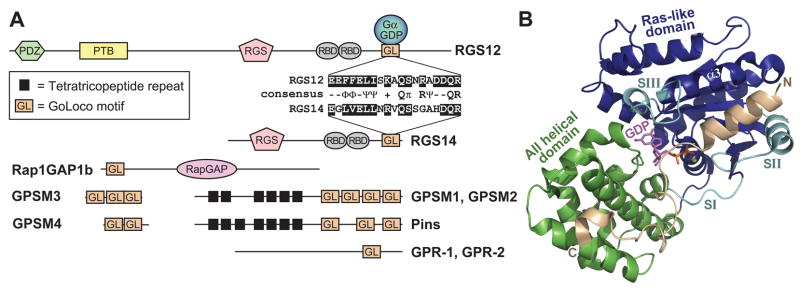

A diverse family of Gα-interacting proteins has been shown to share a common GoLoco (“Gαi/o-Loco” interaction) motif (Figure 1) (reviewed in [3,4]). GoLoco motif-containing proteins generally bind to GDP-bound Gα subunits of the Gi (adenylyl-cyclase inhibitory) class and act as GDP dissociation inhibitors (GDIs), slowing the spontaneous exchange of GDP for GTP and preventing re-association with Gβγ subunits [5–13]. Determination of the crystallographic structure of Gαi1·GDP in complex with the GoLoco motif of RGS14 [7] revealed critical determinants of Gα subunit specificity and GDI activity. The N-terminal alpha-helix of the GoLoco motif peptide binds between switch II and the α3 helix of the Gαi1 Ras-like domain (Figure 1B), grossly deforming the normal site of Gβγ interaction [7]. The aspartate-glutamine-arginine triad, which defines the final residues of the highly-conserved 19 amino-acid GoLoco motif signature (Figure 1A), orients the arginine residue into the guanine nucleotide-binding pocket of Gα, allowing contacts to be made between its basic δ-guanido group and the α- and β-phosphates of GDP [7]. Mutation of this single arginine residue within the Asp-Gln-Arg triad causes a loss of GDI activity [7,8,11].

Figure 1. The GoLoco motif is a Gαi GDP -interacting polypeptide found singly or in arrays in various proteins.

(A) Domain architecture of representative GoLoco motif proteins and a sequence alignment of the conserved core of the RGS12 and RGS14 GoLoco motifs. Domain abbreviations: GPSM, G-protein signaling modulator; PDZ, PSD-95/Discs large/ZO-1 homology; PTB, phosphotyrosine-binding domain; RGS, regulator of G-protein signaling box; RBD, Ras-binding domain; RapGAP, Rap-specific GTPase-activating protein domain. (B) The crystal structure of Gαi1 (Ras-like domain in blue, all α-helical domain in green, switch regions in cyan) bound to the GoLoco motif of RGS14 (PDB ID 2OM2). The GoLoco motif peptide (tan) binds across the Ras-like and all-helical domains of Gαi1, trapping GDP (magenta, with α- and β-phosphates in orange) within its binding site. The bound magnesium ion is illustrated in lime green.

A well-characterized physiological function of GoLoco motif proteins is in the regulation of asymmetric cell division in worm, fruit fly, and mammalian development (reviewed in [4,14]). For example, GPSM2 (a quadruple GoLoco motif-containing protein, previously known as LGN) binds to nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) and regulates mitotic spindle assembly; altering endogenous cellular levels of GPSM2, either via overexpression or RNA interference-mediated knockdown, leads to aberrant chromosomal segregation during mitosis [15]. Similar functions have also been ascribed to Drosophila and C. elegans homologs of GPSM2 (Pins and GPR-1/-2, respectively; refs. [16–20]).

Evidence is also emerging that GoLoco motif-containing proteins act as critical components of cell-surface receptor-mediated signal transduction pathways. GPSM2 over-expression has been found to affect both basal and GPCR-activated potassium currents from GIRK channels [21], the latter effect similar to what we previously observed via cellular microinjection of GoLoco motif peptides [22]. We have recently shown RGS12 to be a receptor-selective scaffold for components of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade [23]. RNA interference-mediated knockdown of RGS12 protein levels in primary mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons blunts nerve growth factor-stimulated axonogenesis [23]. Mutating the arginine residue within the Asp-Gln-Arg triad of the RGS12 GoLoco motif leads to a mislocalization of RGS12 to the nucleus, away from its normally punctate endosomal pattern of expression [24]. This latter finding suggests that small molecule inhibition of the GoLoco motif/Gαi interaction could serve to abrogate the normal signaling regulatory properties of GoLoco motif proteins, not only for RGS12 in the context of inhibiting sustained MAPK signal output, but also for GPSM2 and homologs in the context of dysregulating cell division processes in cancerous states of unchecked cellular proliferation [25,26].

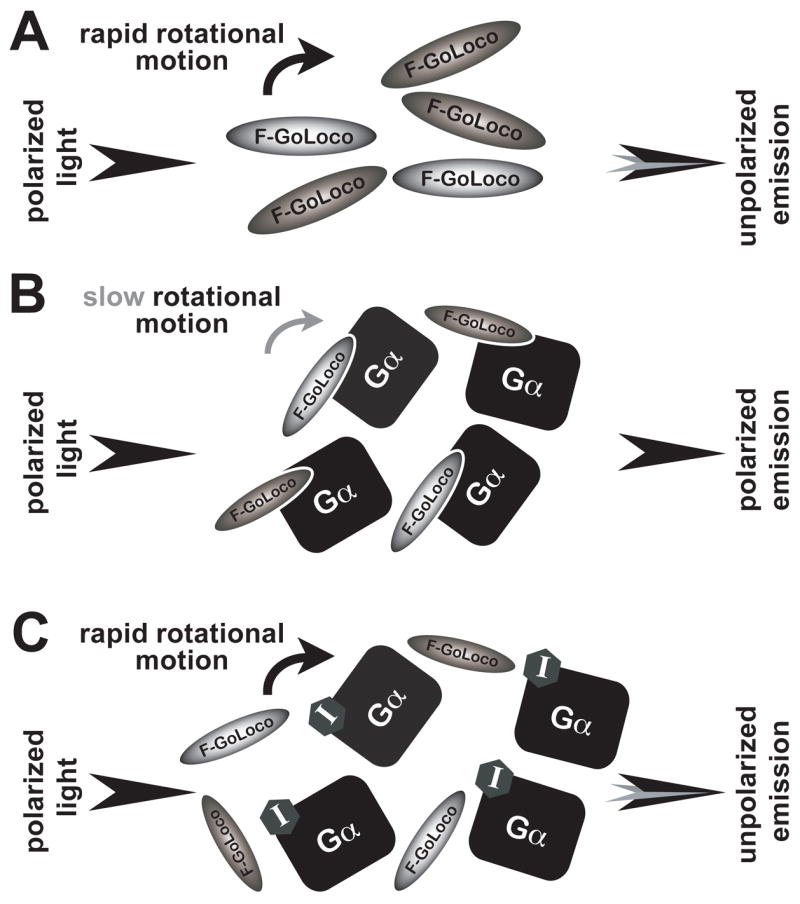

In this article, we describe the development of high-throughput screening (HTS) assays based on fluorescence polarization (FP) for the identification of small molecule inhibitors of the GoLoco motif/Gα protein interaction (Figure 2). FP is often used to detect the binding of fluorescently-labeled small ligands to larger binding partners (e.g., refs. [27–32]). FP is based on the physical principle that fluorescein and other fluorophores are only excited by incident light that is polarized parallel to their axis. If this fluorophore is stationary or only slowly rotating, subsequent emission remains polarized along the same axis. Conversely, if polarized light excites a fluorophore rapidly tumbling in solution (Figure 2A), the resulting emission is depolarized by the rapid rotational diffusion that occurs during the lifetime of the excited state (~4 ns for fluorescein, ref. [33]). This depolarization is quantified as fluorescence anisotropy (FA) or fluorescence polarization (FP) by measuring the intensity of the emission perpendicular (I⊥) and parallel (I||) to the plane of excitation (Equation (1); for a more comprehensive explanation of FA and FP, we refer the reader to ref. [33]). FA and FP are not equal but can be interconverted using equation (2). FP is a unitless ratio; however, it is often expressed as “milliP” (mP).

Figure 2. Schematic of a fluorescence polarization assay for detection of FITC-GoLoco motif probe binding to its Gαi1 subunit target.

(A) When excited by plane-polarized light, the rapid rotational motion of the unbound FITC-GoLoco motif probe decorrelates the light. (B) The rotational diffusion of the FITC-GoLoco motif probe dramatically decreases as its effective molecular weight changes upon binding to Gαi1. Consequently, polarized excitation results in polarized emission. (C) A small molecule inhibitor (“I”) that binds to Gαi1 in competition with the FITC-GoLoco motif probe increases the concentration of unbound (and rapidly rotating) probe, resulting in a decreased polarization signal.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Because the depolarization of fluorophore-emitted light is directly related to the rotational motion of the fluorophore-labeled molecule, and thus inversely related to its total molecular weight (MW), FA and FP are theoretically limited to measuring the binding of a lower MW ligand to a higher MW substrate (e.g., Figure 2B). While in theory this technique can be used to measure binding of any fluorescently-labeled ligand to a substrate as long as the MWligand is much less than MWsubstrate, in practice these assays are limited to ligands that have a MW of less than 5,000 Da. This limitation arises because of the short half-life (~4 ns) of the excited state of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) [33], the most readily used dye in fluorescence polarization assays. (Rhodamine-based dyes have an even shorter half-life in the excited state; ref. [33]). While other dyes with longer lifetimes can be used to measure binding between larger molecules [34–36], their use has not been widespread.

Fluorescence polarization assays have been developed to detect various biological events such as phosphorylation, proteolytic cleavage, single nucleotide polymorphism detection, cAMP production, protein-protein interactions, and protein-DNA interactions [28,29,31,32,37–41]. This article focuses on our development and validation of a ligand displacement assay to screen for inhibitors of RGS12/Gαi1 and GPSM2/Gαi1 interactions (Figure 2C).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Assay Material

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals used were the highest grade available from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Tris-HCl used in the 1,536-well plate format assay was procured from Invitrogen. 96-well black bottom plates were obtained from Costar (Corning, NY). The LOPAC1280 library of known bioactives (1280 compounds from Sigma-Aldrich; arrayed for screening as 8 concentrations at 5 nL each in 1,536-well Greiner polypropylene compound plates) was received as DMSO solutions at initial concentration of 10 mM. Plate-to-plate (vertical) dilutions in 384-well format and 384-to-1,536 compressions were performed on an Evolution P3 dispense system equipped with 384-tip pipetting head and two RapidStak units (Perkin-Elmer; Wellesley, MA). Additional details on the preparation of the compound library for quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) are provided elsewhere [42,43].

Protein Expression and Purification

Expression and purification of human His6-Gαi1 from the expression plasmid pProEXHTb-hGαi1 was performed essentially as previously described [7]. Briefly, BL21 (DE3) E. coli (Novagen; San Diego, CA) were grown to an OD600 nm of 0.6–0.8 at 37°C before induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside. After culture for 14–16 hours at 20°C, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and frozen at −80°C. Prior to purification, bacterial cell pellets were resuspended in N1 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaF, 30 μM AlCl3, 50 μM GDP, 30 mM imidazole, 5% (w/v) glycerol). Bacteria were lysed at 10 MPa using an Emulsiflex pressure homogenizer (Avestin; Ottawa, Canada). Cellular lysates were centrifuged at 100,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin FPLC column (FF HisTrap; GE Healthcare), washed with 7 column volumes of N1 buffer then 3 column volumes of N1 buffer containing an additional 30 mM of imidazole before eluting with N1 buffer containing an additional 300 mM of imidazole. Eluted protein was incubated with tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease and dialyzed into low imidazole buffer (N1 buffer with 5 mM DTT) overnight at 4°C (to cleave the N-terminal hexahistidine tag) before being passed over a second HisTrap column to separate the untagged Gαi1 from contaminants and cleavage products. The column flow-through was pooled and resolved using a calibrated 150 ml size exclusion column (Sephacryl S200, GE Healthcare) with S200 buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 μM GDP, 5% (w/v) glycerol). Protein was then concentrated to approximately 1 mM, as determined by A280 nm measurements upon denaturation in guanidine hydrochloride. Concentration was calculated based on the predicted extinction coefficient obtained using the ProtParam webtool [44]. His6-GαoA was purified using similar chromatographic methods as previously described [45].

Peptide Synthesis

Unless otherwise denoted, peptides were synthesized by Fmoc-group protection, purified via HPLC, and confirmed using mass spectrometry by the Tufts University Core Facility (Medford, MA). Peptide sequences were as follows:

| FITC-RGS12: | FITC-β-alanine-DEAEEFFELISKAQSNRADDQRGLLRKEDLVLPEFLR-amide; |

| FITC-GPSM2(GL2): | FITC- β-alanine-NTDEFLDLLASSQSRRLDDQRASFSNLPGLRLTQNSQS-amide; |

| GPSM1 GoLoco consensus: | TMGEEDFFDLLAKSQSKRMDDQRVDLAG-amide; |

| GPR-1(GoLoco wildtype) | EPVDMMDLIFSMSSRMDDQRTELPAARFIPPRPVSSASK-amide; |

| GPR-1(GoLoco R>F): | EPVDMMDLIFSMSSRMDDQFTELPAARFIPPRPVSSASK-amide. |

The 5-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)-labeled peptide (TAMRA-DEAEEFFELISKAQSNRADDQRGLLRKEDLVLPEFLR-amide) was synthesized and HPLC-purified by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Fluorescence Polarization Measurements in 96-well and 384-well Plate Formats

Polarization measurements during assay pilot trials were conducted using a PHERAstar microplate reader (BMG Labtech; Offenburg, Germany) with the fluorescence polarization module. Excitation wavelength was 485 ± 6 nm and emission was detected at 520 ± 15 nm. For each independent experiment, the gain of the parallel and perpendicular channel was calibrated so that 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 peptide had a polarization value of ~35 mP. The final volume of each 96-well plate well was brought to 180 μl with PheraBuffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM GDP, and 0.05% (v/v) NP40); the final volume per well in the 384-well plate format was 50 μL. For nucleotide selectivity studies, PheraBuffer was alternatively supplemented with aluminum tetrafluoride (i.e., addition of 10 mM NaF and 30 μM AlCl3). Data analysis for these assay pilot trials was conducted using PHERAstar software V1.60 (BMG LABTECH, Germany), as well as Excel version X for Macintosh (Microsoft, Seattle, Washington) and GraphPad Prism v4.0 (San Diego, CA). All dissociation constant (KD) values were determined with non-linear regression and fitting to Equation 3, in which FP is the fluorescence polarization (measured in mP), [Gα] is the concentration of Gαi1, Bmax is the maximum polarization, and FPzero is a correction factor to account for the polarization of unbound peptide (~35 mP).

| (3) |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Binding Assay

As a secondary screen for compounds that demonstrated at least partial concentration-dependent responses in the primary FP screen, optical detection of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was performed using a Biacore 3000 (GE Healthcare; Piscataway, NJ). Surfaces of carboxymethylated dextran (CM5) biosensors (GE Healthcare) were covalently derivatized with anti-GST antibody as previously described [45,46]. A GST fusion protein containing the minimal GoLoco motif of RGS12 [24] and GST protein alone (the latter as a negative control) were separately loaded onto anti-GST antibody surfaces to levels of ~900 resonance units (RUs) before 200 μL of 40 nM Gαi1·GDP protein (preincubated in either test compound or DMSO vehicle only) was injected over all flow cells using the KINJECT command at a flow-rate of 40 μL/minute with a dissociation phase of 2000 seconds. The biosensor surface was then stripped with a 40 μL injection of 10 mM Glycine pH 2.2 before being reloaded with GST-RGS12 fusion protein or GST alone for subsequent Gαi1·GDP injections. Non-specific binding to the GST alone surface was subtracted from each sensorgram curve using BIAevaluation software v.3.0 (Biacore). Percent inhibition of binding was calculated as the maximal RUs of specific binding observed (just before the dissociation phase) from a compound-treated Gαi1·GDP injection compared to a paired DMSO control-treated Gαi1·GDP injection.

qHTS Validation in 1,536-well Plate Format

Control plate set-up

Titration of the unlabeled control peptide was delivered via pin transfer [47] of 23 nL of solution per well from a separate source plate into column 2 of each assay plate. The starting concentration of the control peptide was 10 mM and 20 mM for the FITC (green) and TAMRA (red) assay, respectively, followed by two-fold dilution points in duplicate, for a total of sixteen concentrations, resulting in final assay concentration range from 57.2 nM to 1.74 nM, and 114 nM to 3.49 nM, for the green and red assay, respectively.

Pre-screen assay miniaturization and optimization

Titration samples containing a constant amount of fluorophore-labeled peptide and variable concentrations of Gαi1 protein were prepared in 384-well plates and transferred into 1,536-well black solid bottom plates by the use of CyBiWell 384-tip pipeting system (CyBio Boston, MA). For the subsequent 1,536-well-based experiments, a Flying Reagent Dispenser (FRD, Aurora Discovery, presently Beckman-Coulter) [48] was used to dispense reagents into the assay plates.

qHTS protocol

Four nL of reagents (10 nM FITC- or 15 nM TAMRA-labeled peptide in columns 3 and 4 as negative control; a mixture of 10 nM FITC- or 15 nM TAMRA-labeled peptide with Gαi1 [50 nM in the green assay and 25 nM in the red assay, respectively] in columns 1, 2, 5–48) were dispensed into 1,536-well Greiner black assay plates. Compounds and control peptide (23 nL) were transferred via Kalypsys pintool equipped with a 1,536-pin array (10 nL slotted pins, V&P Scientific, San Diego, CA) [47]. The plate was incubated for 10 min at room temperature, and then read on a ViewLux high-throughput CCD imager (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA) using FITC polarization filter sets (excitation 480 nm, emission 540 nm) for the green assay and BODIPY sets (excitation 525 nm, emission 598 nm) for the red assay, respectively. During reagent dispensing, reagent bottles were kept submerged in a 4 °C recirculating chiller bath and all liquid lines were covered with aluminum foil to minimize probe and protein degradation. All screening operations were performed on a fully integrated robotic system (Kalypsys, San Diego, CA) containing one RX-130 and two RX-90 anthropomorphic robotic arms (Staubli, Duncan, SC). Library plates were screened starting from the lowest and proceeding to the highest concentration. Vehicle-only plates, with DMSO being pin-transferred to the entire column 5–48 compound area, were included at the beginning, middle, and the end of the validation run in order to record any systematic shifts in assay signal.

Analysis of qHTS data

Screening data were corrected and normalized, and concentration-effect relationships derived by using NCGC in-house developed algorithms. Percent activity was computed after normalization using the median values of the uninhibited, or neutral, control (32 wells located in column 1) and the free-probe, or 100% inhibited, control (64 wells, entire columns 3 and 4), respectively. An in-house database was used to track sample concentrations across plates, while ActivityBase (ID Business Solutions Ltd, Guildford, UK) was used for compound and plate registrations. A four-parameter Hill equation [49] was fitted to the concentration-response data by minimizing the residual error between the modeled and observed responses.

Results

Detection of Gα/GoLoco motif interactions using fluorescence polarization

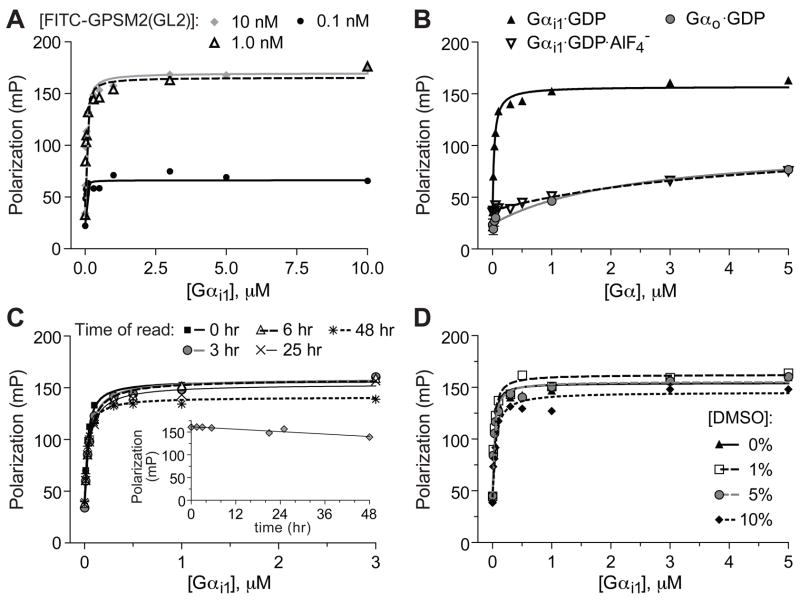

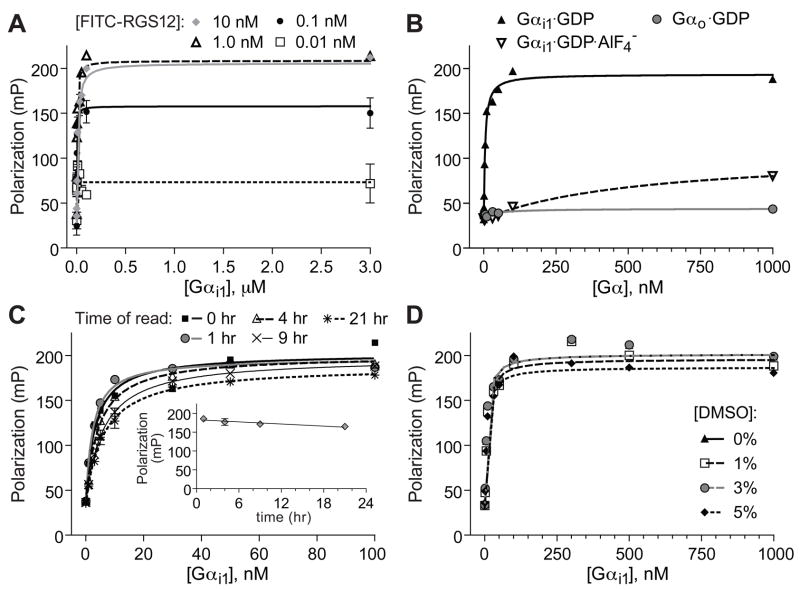

We previously described the use of a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled RGS12 GoLoco motif peptide (FITC-RGS12) as a probe to measure Gα/GoLoco motif interactions using FP [13]. Our aim in this present study was to validate this FP assay, and develop a corresponding Gαi1/GPSM2 interaction assay, as robust techniques for high-throughput screening for small molecule inhibitors of the Gα/GoLoco motif interaction. To establish an assay for Gαi1 binding to a GoLoco motif from GPSM2 (Figure 3), we first incubated increasing concentrations of Gαi1 protein (up to 10 μM) with constant amounts (either 0.1, 1.0, or 10 nM) of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) peptide encoding the second GoLoco motif of GPSM2. We observed robust interaction of Gαi1 with FITC-GPSM2(GL2), whereby addition of saturating amounts of Gαi1 caused an increase in FP from ~35 mP to ~160 mP (Figure 3A). Saturation binding isotherms illustrated that signal strength was optimal at FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe concentrations of 1 nM and above (Figure 3A). Non-linear regression was used to fit the binding isotherms from experiments using two different probe concentrations to Equation 3, yielding dissociation constants (KD) of 34 nM (using 1.0 nM probe) and 38 nM (using 10 nM FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe). Saturation binding isotherms of FITC-RGS12 binding to Gαi1 were also generated (Figure 4). FITC-RGS12 levels were held constant at 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 nM while the concentration of Gαi1 was increased up to 3 μM. While binding was observable with sub-nanomolar concentrations of FITC-RGS12 probe, maximal polarization (~200 mP) was observed at FITC-RGS12 concentrations =1 nM (Figure 4A); however, at probe concentrations below 5 nM, increased noise was observed upon the addition of DMSO (data not shown). The binding affinity for the FITC-RGS12 to Gαi1 was 3.8 nM (using 1 nM FITC-RGS12 probe).

Figure 3. 96-well microtiter plate-formatted fluorescence polarization assay for FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe binding to Gαi1.

(A) Concentration dependence and saturability of binding. Indicated concentrations of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe were incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP prior to measuring fluorescence polarization at equilibrium. (B) Nucleotide and Gα subunit dependence of polarization signal. 1 nM of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe was incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP (ground-state), Gαi1·GDP·AlF4− (transition-state-mimetic form), or Gαo·GDP prior to measuring fluorescence polarization at equilibrium. (C) Time-stability studies. 1 nM of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe was incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP in 96-well microtiter plate wells for indicated times prior to measuring fluorescence polarization. Inset, Time-dependence of polarization signal from 1 nM of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe incubated with 3 μM Gαi1·GDP. (D) DMSO tolerance. 1 nM of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe was incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP and indicated final concentrations (v/v) of DMSO prior to measuring fluorescence polarization.

Figure 4. 96-well microtiter plate-formatted fluorescence anisotropy assay for FITC-RGS12 GoLoco motif probe binding to Gαi1.

(A) Concentration dependence and saturability of binding. Indicated concentrations of FITC-RGS12 probe were incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP prior to measuring fluorescence polarization at equilibrium. (B) Nucleotide and Gα subunit dependence of polarization signal. 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 peptide was incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP (ground-state), Gαi1·GDP·AlF4− (transition-state-mimetic form), or Gαo·GDP prior to measuring fluorescence polarization at equilibrium. (C) Time-stability studies. 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 probe was incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP in 96-well microtiter plate wells for indicated times prior to measuring fluorescence polarization. Inset, Time-dependence of polarization signal from 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 probe incubated with 30 nM Gαi1·GDP. (D) DMSO tolerance. 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 peptide was incubated with indicated concentrations of Gαi1·GDP and indicated final concentrations (v/v) of DMSO prior to measuring fluorescence polarization. Error bars are mean ± SEM from triplicate samples.

To verify that these FP assays truly detect binding of the FITC-GPSM2(GL2) and FITC-RGS12 probes to their intended target of Gαi1·GDP (consistent with the known biochemistry of GoLoco motif/Gα interactions [4]), we tested the nucleotide dependence of the interaction. Saturation binding isotherms were generated at a constant concentration of 1 nM of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe with increasing concentrations of Gαi1 in either PheraBuffer or PheraBuffer with aluminum tetrafluoride (AlF4−, which binds Gα to create a transition state-mimetic form). As expected, upon the addition of AlF4−, there was a dramatic decrease in observed binding affinity. FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe bound three orders of magnitude more avidly to Gαi1·GDP than to Gαi1·GDP·AlF4− (KD of 35 nM versus 15 μM, respectively; Figure 3B). Binding of FITC-RGS12 probe demonstrated a similar preference for Gαi1·GDP (KD of 4.3 nM versus 1.6 μM for Gαi1·GDP·AlF4−; Figure 4B).

While GoLoco motifs were originally described as Gαi/o-binding peptides [3], subsequent biochemical characterization has demonstrated preferential binding to the Gαi subfamily (Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3) and not to Gαo (e.g., refs. [6,9]). To assess Gα subunit specificity, the binding of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) and FITC-RGS12 probes to Gαi1·GDP and Gαo·GDP proteins was compared. Both GoLoco motif probes exhibited significantly higher binding affinities for Gαi1·GDP than for Gαo·GDP. The KD for the FITC-GPSM2(GL2)/Gαo·GDP interaction was determined to be 3 μM, nearly two orders of magnitude higher than the affinity of the FITC-GPSM2(GL2)/Gαi1·GDP interaction (Figure 3B). Similarly, the binding affinity of FITC-RGS12 for Gαo·GDP was observed to be 70 μM versus 4.3 nM for Gαi1·GDP (Figure 4B).

To further validate this GoLoco motif/Gαi1 interaction assay for use in HTS, we characterized time dependence and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) tolerance of the assay. To assess the stability of the assay over extended periods of time, we measured saturation binding isotherms using 96-well plates containing FITC-GPSM2(GL2) or FITC-RGS12 probes (and increasing concentration of Gαi1) that were rescanned at several hour time intervals. The KD of the FITC-GPSM2(GL2)/Gαi1 interaction was consistent over the first 25 hours of repeated measurements and increased marginally only at 48 hours (Figure 3C). Similar long-term stability was also observed for FITC-RGS12/Gαi1 interaction (Figure 4C). Additional tests were made to establish the sensitivity of the assay to the standard HTS compound solvent DMSO; the FP assay using either FITC-GPSM2(GL2) or FITC-RGS12 probe demonstrated remarkable tolerance up to at least 5% (v/v) DMSO (Figures 3D, 4D).

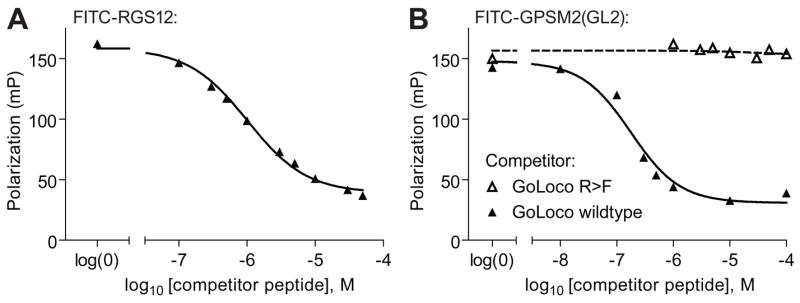

Competitive Binding Studies

To confirm that the FITC-GPSM2(GL2) and FITC-RGS12 probes bound in a reversible manner, unlabeled GoLoco motif peptides were used as “cold competitors” (Figure 5). For these competition binding assays, the concentrations of the FITC-labeled probe and Gαi1 were chosen so that the polarization signal was at ~80% of the maximal response [50]. Addition of unlabeled competitor peptide, derived from GPSM1 GoLoco motifs [5], to a mixture of 5 nM FITC-RGS12 probe and 30 nM Gαi1 resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in polarization (Figure 5A) with an IC50 of 1 μM. In separate tests using 1 nM FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe and 600 nM Gαi1, the IC50 for the unlabeled GoLoco motif competitor (based on GPR-1; [20]) was determined to be 177 nM (Figure 5B). To rule out the possibility of the apparent competition being an artifact of high peptide concentrations, we also titrated in a GoLoco motif peptide with the critical arginine of the Asp-Gln-Arg triad mutated to phenylalanine (“GoLoco R>F”; Figure 5B). As expected, this mutant peptide had no inhibitory effect at the same or higher concentrations.

Figure 5. Competitive inhibition of fluorescence polarization signal by unlabeled GoLoco motif peptides.

(A) Indicated concentrations of the unlabeled GPSM1 GoLoco motif consensus peptide was added to 5 nM FITC-RGS12 probe and 30 nM Gαi1. (B) Indicated concentrations of the unlabeled GPR-1 GoLoco motif peptide (“GoLoco wildtype) or the same peptide with the critical arginine mutated to phenylalanine (“GoLoco R>F”). Peptides were incubated with 1 nM of FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe and 600 nM of Gαi1·GDP protein prior to measuring fluorescence polarization at equilibrium.

Estimation of Screening Window

The next step in validation of this FP-based HTS assay was determining its screening window. An initial screening window can be crudely estimated by measuring many samples that only contain positive or negative controls for inhibition of the probe/Gα interaction [51,52]. The mean and standard deviation of these controls were used to determine a Z′-factor for the assay using Equation (4), where σ is the standard deviation of the positive or negative control for inhibition and μ is the mean of the positive or negative control FP measurement [52]. Unlike other methods for quantifying the quality of an assay, the Z′-factor accounts for both the dynamic range (denominator) of the assay as well as the variation from well-to-well (numerator). The Z′-factor for the FP assay using 5 nM FITC-RGS12 probe, 30 nM Gαi1, and 30 μM unlabeled GoLoco motif competitor peptide was calculated to be 0.84. This value was obtained by running one 96-well plate of positive controls and one 96-well plate of negative controls at 175 μl final volume and 1% (v/v) DMSO. Reduction in well volume below 175 μl was found to increase the standard deviation of both positive and negative controls (data not shown). Performing the same analysis with the FITC-GPSM2(GL2) probe resulted in a Z′-factor of 0.81. To assess the scalability of this FP assay to higher density plates, the same replicates of positive and negative controls for inhibition were also run with the FITC-RGS12 probe using 384 well plates. The Z′-factor was found to be 0.80 using a final volume of 50 μl.

| (4) |

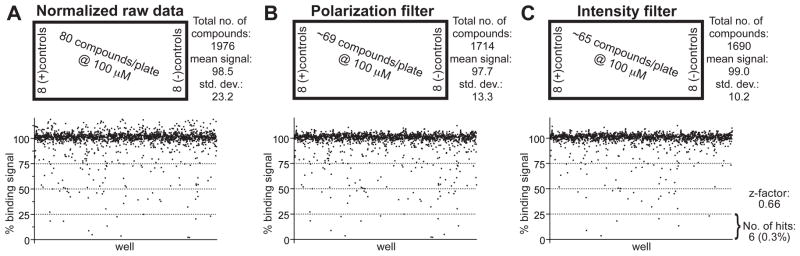

Initial Small Molecule Screen in 96-well Plate Format

While computing a Z′-factor is useful in assay development, screening window data from an actual compound library screen is more informative [51]. Towards this goal, we first obtained the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Developmental Therapeutics Program’s Diversity Set (http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/branches/dscb/diversity_explanation.html) and screened 1976 compounds from this collection at 100 μM final concentration (Figure 6). Raw fluorescence polarization data was first normalized to the mean polarization signal from negative controls (1% (v/v) DMSO only; set to 100% binding signal) and from positive controls for inhibition (30 μM GPSM1 competitor peptide; set to 0% binding signal) (Figure 6A). A total of 286 compounds were excluded based on non-specific effects on the fluorescence polarization and total fluorescence intensity readouts. First, compounds were excluded if the obtained polarization value was 5 standard deviations higher than the negative control or 5 standard deviations lower than the positive control for inhibition (“Polarization filter”, Figure 6B). Next, compounds were excluded if the raw fluorescence intensity value was 6 standard deviations higher than the negative control or 6 standard deviations lower than the positive control for inhibition (“Intensity filter”, Figure 6C). The screening window Z-factor from normalized data for the remaining 1690 compounds was 0.66, with a hit-rate of 0.3% (6 out of 1976 compounds tested; ‘hit’ defined as >75% inhibition) (Figure 6C). A parallel screening of the Diversity Set at 50 μM final compound concentration gave a screening window Z-factor of 0.69 with a hit rate of 0.48 % (data not shown).

Figure 6. Data from pilot screen of the NCI Diversity Set to establish a screening window Z-factor.

(A) Plot of normalized fluorescence polarization data from entire 1976 compound set run in 96-well plate format with 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 probe and 30 nM of Gαi1·GDP protein. Positive control wells contained 30 μM of competitor GPSM1 peptide; negative control wells contained vehicle only (1% (v/v) DMSO). (B) Data after exclusion of wells with polarization values 5 standard deviations outside control values (as described in text). (C) Data after additional exclusion of wells with raw fluorescence intensity values 6 standard deviations outside control values (as described in text).

Screening in the 384-well plate format and hit validation by SPR

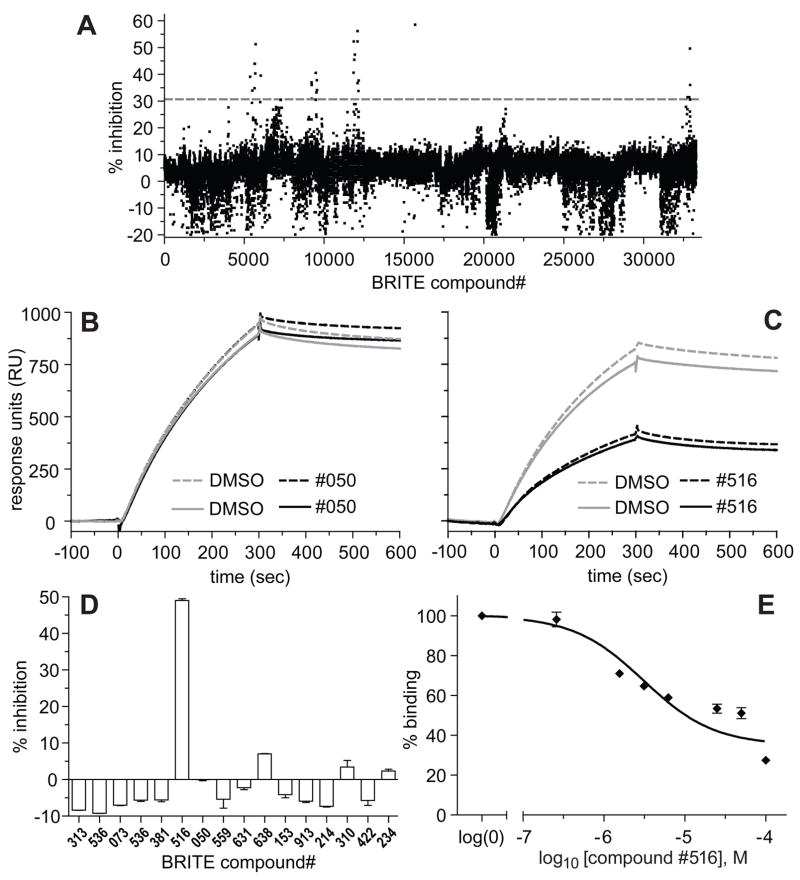

To examine the performance of the FP assay against a larger compound collection, we used the 384-well plate formatted assay in a screen of a 33,600-compound subset of the Biogen Idec 350,000 compound library. Thirty-two compounds were identified as inhibiting the assay by at least 30% (~1% hit rate); most of the hits were found in four clusters (Figure 7A), reflecting the grouping of compounds sharing similar chemistry on the same plates which is inherent to the design of the library subset derived from the original 350,000 compound library. Subsequent re-testing of each hit revealed 17 compounds exhibiting at least partial concentration-dependent inhibition of the primary FP assay. To validate these hits as inhibitors of the protein/peptide interaction, a secondary assay was performed based on optical detection of changes in surface plasmon resonance (e.g., Figure 7B,C) upon binding Gαi1 to immobilized GST-RGS12(GoLoco motif) fusion protein [24]. One of the hits from the primary FP assay was also found to inhibit the secondary SPR assay in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 7D,E). This compound is now the subject of further analysis.

Figure 7. Data from pilot primary screen of the BRITE Biogen Idec library subset and hit validation using an SPR-based secondary assay.

(A) Plot of percent inhibition for each compound in the 33,600-element BRITE Biogen Idec library subset run at 10 μM final concentration in 384-well plate format with 5 nM of FITC-RGS12 probe and 46 nM of Gαi1·GDP protein. Note the clustering of inhibitory activity reflecting plate-wise grouping of similar compound chemistry within the 33,600 compound subset of the larger 350,000 Biogen Idec library. Gray dashed line represents cut-off of greater than 30% inhibition used to select compounds for subsequent dose-response testing in the same primary FP assay. (B, C) Representative SPR data from two compounds exhibiting at least partial concentration-dependent responses in the primary FP assay. Panel B represents negative data from compounds (such as #050) that, after preincubation with Gαi1·GDP, did not inhibit the latter binding to a GST-RGS12(GoLoco motif) biosensor surface during a 5 minute association phase (0–300 seconds). Panel C represents positive data from a confirmed inhibitor of the Gαi1·GDP/GST-RGS12(GoLoco motif) interaction (compound #516). (D) Results of single-dose testing (13.3 μM final concentration) of 16 hits from the primary FP assay in the SPR-based secondary assay, performed as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Dose-response curve of the sole confirmed hit (compound #516) from the SPR-based secondary assay, performed as described in Materials and Methods, except with 50 μL injections of Gαi1·GDP at a flow-rate of 20 μL/min and a subsequent 200 second dissociation time.

Assay miniaturization to 1,536-well plates and evaluation of red-shifted peptide probes

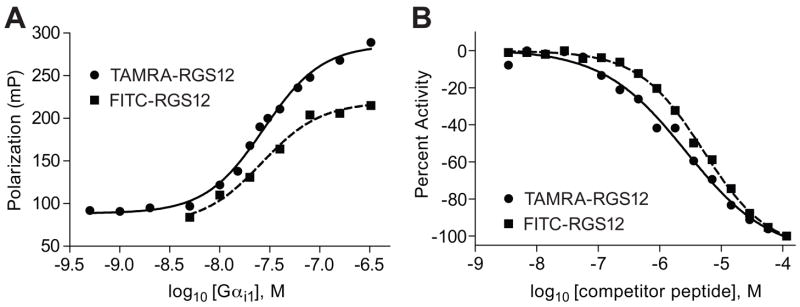

The FP assay was further miniaturized to a final volume of 4 μL in 1,536-well plate format by direct volume reduction. Retaining the inclusion of NP-40 in the assay buffer helped prevent peptide and protein absorption to the polystyrene wells due to the increased surface-to-volume ratio and also served to minimize the interfering effect of promiscuous inhibitors acting via colloidal aggregate formation [43,47]. In a titration experiment using 10 nM FITC-RGS12 probe (hereinafter referred to as green probe), a robust FP signal change was observed (Figure 8) and a Gαi1 protein concentration of 50 nM was selected for subsequent validation experiments. When the complex of 10 nM green probe and 50 nM Gαi1 protein was incubated with varying concentrations of unlabeled peptide in the 1,536-well plate, a concentration-response curve was observed (Figure 8B) whose associated IC50 value matched closely that obtained from 96- and 384-well based experiments.

Figure 8. Miniaturization of FP assay to 1,536-well plate format and evaluation of FITC- versus TAMRA-labeled RGS12 GoLoco motif peptide probe.

(A) Fluorescence polarization signal of FITC- (green) and TAMRA- (red) probes in the 1,536-well plate format. Protein-concentration dependence of the FP signal of 10 nM green probe (solid squares) and 15 nM red probe (solid circles) was measured in titrations with Gαi1. Evident from the plots is the greater FP signal obtained from the red probe. (B) Probe displacement by unlabeled peptide control in the 1,536-well plate format. Green (solid squares, 10 nM FITC-RGS12 probe plus 50 nM Gαi1) and red (solid circles, 15 nM TAMRA-RGS12 probe plus 25 nM Gαi1) protein complexes were allowed to interact with series of concentrations of unlabeled peptide (pin-transferred from DMSO stock solutions) for 15 min at room temperature. The leftward-shift in dose-response of the red probe curve is a reflection of the slight increase in assay sensitivity afforded by the decreased protein concentration.

In parallel with the miniaturization of the original green assay, a red-shifted probe was explored. Prior experience and our recent profiling of the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) compound library with respect to autofluorescence [53] prompted us to seek a red-shifted assay system in order to minimize the fraction of fluorescent compounds interfering with the fluorescent readout. Thus, a peptide of the same RGS12 GoLoco motif sequence was labeled with 5-carboxytetramethyl rhodamine (TAMRA, hereinafter referred to as red probe) and subjected to the same assay optimization experiments. In order to maintain robust fluorescence intensity signal with this fluorophore, the red probe concentration was increased slightly to 15 nM. In protein titration experiments, the FP signal change observed with the red-labeled peptide was higher, in the range of 180–190 mP, as previously experienced with this fluorophore [54] (Figure 8A). The increased FP window per same protein concentration allowed us to decrease the Gαi1 protein concentration in the red assay to half that of the green assay (25 nM versus 50 nM) while maintaining a sufficient signal window. Consistent with lowered probe and protein concentrations for the red system (15 nM red probe with 25 nM Gαi1 protein versus 10 nM green probe and 50 nM Gαi1 protein), the displacement of the red probe from its complex by the unlabeled competitor peptide resulted in left-shifted concentration-response curve (Figure 8B), thus confirming that the lowered protein load resulted in slightly improved assay sensitivity.

During the course of our red probe exploration, we evaluated two red-shifted fluorophores. An RGS12 GoLoco motif peptide of the same sequence labeled with BODIPY Texas Red failed to yield a change in fluorescence polarization when titrated with Gαi1 protein (data not shown), presumably due to an adverse effect of the fluorophore on the RGS12 peptide binding affinity and/or increased self-aggregation of the probe due to the hydrophobic nature of the BODIPY moiety. Thus, not every combination of peptide probe and fluorophore should be expected to yield a readily-optimizable binding assay and, as the present limited example suggests, fluorophores of an overly-hydrophobic nature might be problematic when used with peptides (as opposed to oligonucleotide or DNA probes, for example) while those containing a number of ionizable groups such as TAMRA might offer a better chance for developing a good peptide-based FP assay [54].

qHTS robotic validations using the LOPAC1280 library

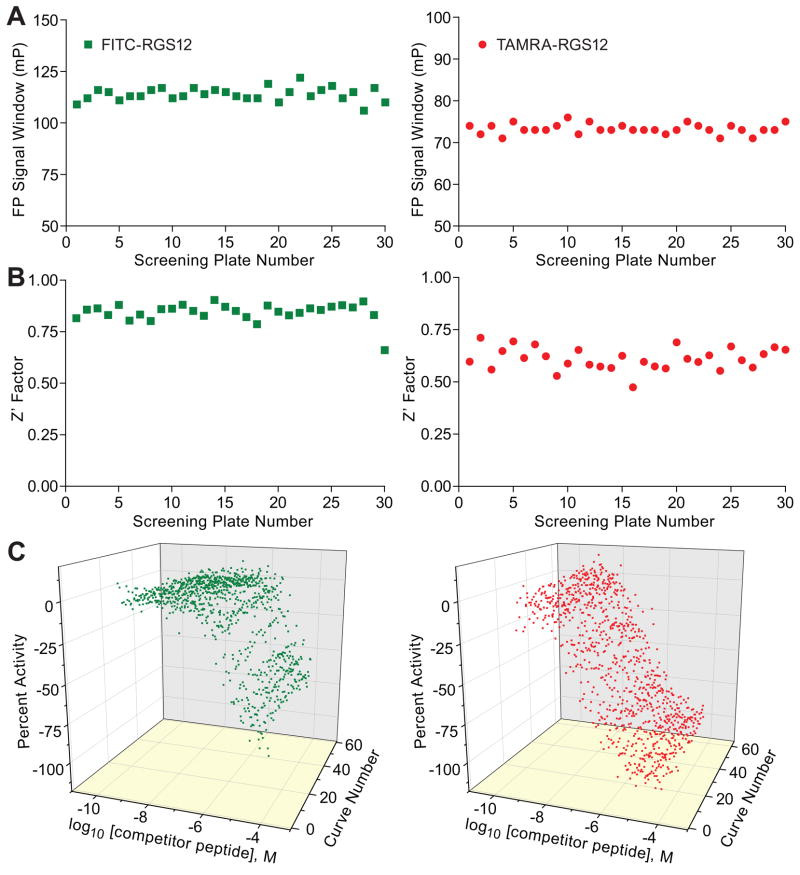

Once the peptide probe and Gαi1 protein concentrations were optimized for the green and red assays, we proceeded to run fully-automated, 1,536-well based robotic validations. For each fluorophore system, the LOPAC1280 collection was screened three consecutive times in concentration-response mode [42]. A total of 30 plates were run per fluorophore assay: 24 compound plates (i.e., three iterations of the LOPAC1280 eight-concentrations set) and 6 control DMSO plates,. The assay signal windows, as expressed by the difference between mean FP values for the bound and unbound labeled peptide controls, were stable throughout the robotic validation (Figure 9A). Both assays performed robustly, yielding an average Z′ factor of 0.84 for the green assay and 0.66 for the red assay, respectively (Figure 9B). The intra-plate peptide control titration curves remained nearly overlapping throughout the screen progression (Figure 9C), yielding average IC50 values of 7.8 μM and 0.6 μM for the green and red assays, respectively. During these qHTS experiments, each library compound was tested as an eight-point titration, with concentrations ranging from 2 nM to 57 μM, and for each well and each assay system, fluorescence polarization values, as well as parallel- and perpendicular-plane fluorescence intensity values, were collected and stored in the database.

Figure 9. qHTS Performance.

Shown for both the green and red probe FP assays are the (A) FP signal window, (B) Z′ factor trend, and (C) intra-plate control titrations (duplicate curves per plate) as a function of screening plate number.

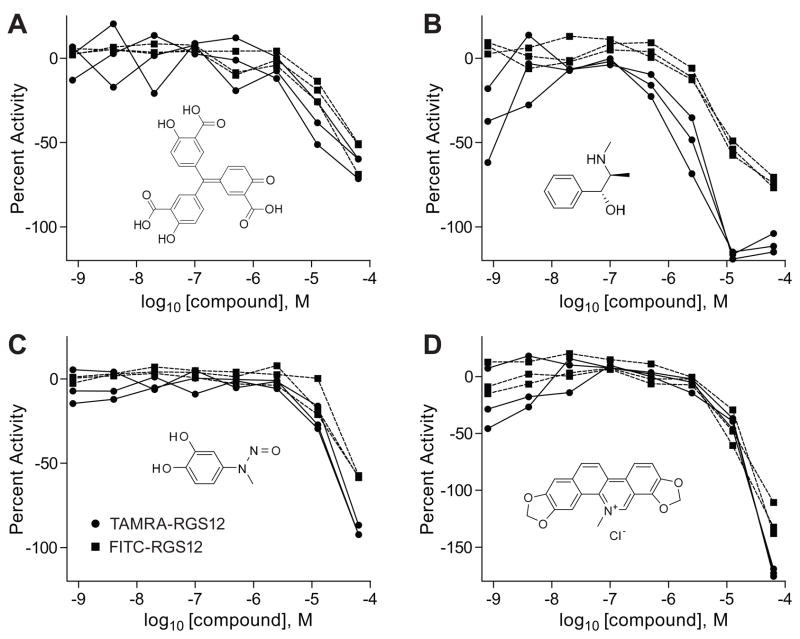

Unlike traditional HTS, qHTS provides concentration responses for all the compounds screened and allows determination of the half-maximal activity concentrations associated with each active compound. Additionally, compound effect can be described with respect to the shape, efficacy, and goodness-of-fit of its concentration-response curve [42]. Our LOPAC1280 library validation runs revealed 8 active compounds shared by the green and red screens, some of which were associated with complete concentration-response curves while others showed single-point inhibition at the highest concentration and, as such, the sigmoidal dose-response curves fitted through their data were of the lowest quality and reproducibility. However, for most of the active compounds identified in the LOPAC1280 library, there was excellent reproducibility within the triplicate runs, as well as good agreement between the outcomes from the green and red assays. Four examples of triplicate green and red concentration-response curves derived from the validations are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Examples of validation-derived active compounds.

The concentration-response curves (triplicate runs in both colors, with green probe data in solid squares and red probe data in solid circles) are shown for (A) NCGC00093568 (PubChem SID 11110719), (B) NCGC00093901 (PubChem SID 11111142), (C) NCGC00094195 (PubChem SID 11111500), and (D) NCGC00094379 (PubChem SID 11111810).

Discussion

Sensitivity of Binding Detection and Screening Window Optimization

In agreement with several previous studies of Gαi/GoLoco interactions (reviewed in [4]), the FP assay we have developed clearly demonstrates preferential binding of the GoLoco motif to the inactive, ground state of Gαi (i.e., Gαi1·GDP) and selective binding of Gαi1 versus Gαo (Figures 3B and 4B). The equilibrium binding-based FP assay was also found to detect binding with affinities that are consistent, but higher, than previously published and unpublished results using kinetic measurements (kon, koff) obtained by surface plasmon resonance [7,9]. These higher observed affinities for the RGS12 and GPSM2 interactions with Gαi1·GDP are most likely the result of the highly-sensitive probe detection technique being used in the FP assay, allowing use of probe concentrations that are less than the observed KD values. Additionally, the relatively hydrophobic FITC moiety added to these GoLoco motif peptides is likely to bind to Gαi1 and thereby increase the overall affinity of the labeled GoLoco motif peptide for its Gαi substrate.

From Equation (2), one can see that the Z′-factor is dependent on the standard deviation of the positive and negative controls. We found that the standard deviation could be decreased by increasing the amount of FITC-GoLoco motif probe in the assay as well as increasing the number of excitation flashes per well during fluorescence polarization measurements. However, these two factors must be balanced with competing considerations of increasing reagent consumption and the time to scan plates. An alternative way to increase the screening window would be to increase the Gαi1 concentration to increase the difference between the minimum and maximum FP signal; however, this change would concomitantly increase the amount of unbound Gαi1 and thus require more cold competitor peptide or compound to cause inhibition in the signal, resulting in a less sensitive assay.

Small-Scale Library Screens and Strategies for Minimizing Compound Interference

The fundamentally ratiometric nature of the fluorescence polarization measurement theoretically reduces the effects of interference from compounds that have overlapping spectra with the FITC-labeled probe [30]. Interference from compounds with overlapping absorbance spectra should not change an FP reading so long as the absorbance is proportional (P) along both axes (Equation 5); however, the robustness of this ratiometric measurement cannot compensate for compounds that interfere by increasing or decreasing the signal in an additive (A) manner (Eq. 5).

| (5) |

While a high tolerance to interference from compound absorbance is an advantage of FP assays, 226 compounds (11.4% of the set) were excluded from our pilot screening data of the NCI Diversity Set, based on FP measurement interference. With the FITC-labeled (green) assay, we developed a systematic way to exclude interfering compounds as shown in Figure 6. From the initial raw data, each plate was normalized so that the average of eight positive control wells for inhibition were set to 0% binding and the average of eight negative control wells were set to 100% binding. After this normalization, compounds that resulted in polarization values 5 standard deviations above 100% binding or 5 standard deviations below 0% binding were excluded. Compounds giving readings above the threshold likely interfered by causing aggregation of either probe or substrate. Compounds giving readings significantly below 0% binding were excluded because these compounds clearly interfered with probe fluorescence. Following this “polarization filter”, additional compounds were excluded based on intensity values [30]. While we observed that the fluorescence intensity of the FITC-GoLoco motif probes increased upon binding to Gα, this change in intensity was consistent between wells and across plates. Compounds that resulted in a total intensity value (2I⊥+I||) falling 6 standard deviations outside of the intensity window established from the controls were also excluded. As the result of these exclusions, 1690 of 1976 compounds remained within the NCI Diversity Set for consideration as Gαi/GoLoco motif binding inhibitors, with 6 of these compounds demonstrating inhibition of greater than 75 percent. From this single-concentration screen of nearly two thousand compounds at 100 μM final concentration and 1% (v/v) DMSO, the Z-factor was 0.66. This FP screen was also conducted at 50 μM final compound concentration and very little improvement in Z-factor was noted (data not shown). While the Z-factor was significantly lower than the Z′-factor calculated from controls, the Z-factor derived from this pilot library screen represents the actual screening window and, at a value of 0.66, still reflects an excellent assay robustness amenable to HTS of larger compound collections.

Another aspect of our optimization of this FP screening strategy was the development and implementation of a red-shifted fluorophore assay employing a TAMRA-labeled version of the RGS12 GoLoco motif peptide. The rationale for this change was to move farther away from the autofluorescence-sensitive regions of the light spectrum. In fact, our recently-completed fluorescent spectroscopic profiling of the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) and other compound libraries demonstrated that, in blue-shifted fluorophore regions such as the frequently-utilized UV/vis spectrum (excitations near 360 nm and emissions near 450 nm) and fluorescein spectrum (excitations around 480 nm and emissions near 520 nm), a significant proportion of library compounds are expected to interfere with the fluorescent assay readout (as high as 3% in the UV/vis region and 0.1% in the fluorescein region, respectively) [53]. In the present work, the transition to a red-shifted fluorophore resulted in an additional two-fold benefit of lowering the protein requirement for the screen and improving the sensitivity of the binding assay, both due to the fact that the rhodamine-based probe afforded greater FP signal change for the same protein concentration.

Benefits of the qHTS Approach

The robotic validation screen for inhibitors of the RGS12 GoLoco motif/Gαi1 complex was performed in qHTS format, with every compound tested over a range of concentrations, spanning from tens of micromolar to low nanomolar, to generate a broad concentration-response profile. Thus, in addition to potencies and efficacies being assigned to each active compound immediately out of the primary screen, false positives and negatives due to single-point outliers are easily identified in the context of compound titration. Stated differently, after performing qHTS, the selection of active compounds is based on the premise that the biological effect of an active compound is a function of its concentration, rather than on pure statistical arguments and application of cutoffs. While the library preparation and the primary screen are “front-loaded” with an increased number of plates, the savings associated with reduced cherry-picking, re-arraying, and retesting steps tend to make up for those elevated initial costs, due to the increased robustness and higher information content of the screening data. Additionally, the higher quality of such screening datasets is expected to make them more valuable for data-mining in recently-established public databases such as PubChem.

In both robotic validations, the green and red assays performed robustly in the 1,536-well plate format, with Z′-factors remaining flat with the screen progression. The intra-plate unlabeled peptide control titration, which can be viewed as a combined internal standard for both the underlying assay biology and the reproducibility of compound transfer, yielded concentration-response curves that remained stable and reproducible throughout the screens (Figure 9C). Of note, miniaturization of this and other assays all the way to the 1,536-well plate format not only leads to reagent savings but also allows one to employ additional controls such as the intra-plate titration described here. The application of such controls that measure “the pulse” of the assay, while not necessarily required for signal normalization purposes, is made possible by the availability of so many additional wells in the 1,536-well plate. In lower plate densities, such as the 96-well plate, allocating 8 or 16 wells to low and high normalization controls is frequently barely enough to provide good statistics during large-scale screening. In contrast, in 1,536-well plates, the simple propagation of one empty 96-well plate column (equivalent to 8 wells) to the higher density plate leads to the natural creation of 128 wells (sixteen 96-well source plates feeding into one 1,536-well final plate) [43]. This 16-fold increase in the potentially-available wells makes it possible to add information content to each assay plate (by further partitioning the controls area) during large-collection miniaturized screens without placing undue burden on library preparation or otherwise compromising the outcome of the screens.

During our qHTS validations, each library compound was tested at eight concentrations and, for each well and fluorophore-type assay, three measurements were collected for a combined total of ~200,000 data points. The observed top active compounds in the green and red screens reproduced well upon repeated primary screening and across fluorophores (Figure 10). Our successful robotic validation screen suggests that this FP assay is robust and sensitive enough to be utilized in a large-scale, 1,536-well based screen.

Acknowledgments

Work performed at the NCGC was supported by the Molecular Libraries Initiative of the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. Work performed in the Siderovski lab was funded by NIH grants F30 MH074266 (to A.J.K.) and R03 NS053754 (to D.P.S.).

Footnotes

DATA DEPOSITION: The two 1,536-well plate formatted bioassays reported in this paper, as well as active compounds identified in the LOPAC1280 library validation screens, have been deposited in the PubChem database, http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (AID codes 879 for the green assay and 880 for the red assay).

References

- 1.Gilman AG. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:615–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:993–6. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siderovski DP, Diverse-Pierluissi M, De Vries L. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:340–1. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willard FS, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:925–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Vries L, Fischer T, Tronchere H, Brothers GM, Strockbine B, Siderovski DP, Farquhar MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimple RJ, De Vries L, Tronchere H, Behe CI, Morris RA, Gist Farquhar M, Siderovski DP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29275–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimple RJ, Kimple ME, Betts L, Sondek J, Siderovski DP. Nature. 2002;416:878–81. doi: 10.1038/416878a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimple RJ, Willard FS, Hains MD, Jones MB, Nweke GK, Siderovski DP. Biochem J. 2004;378:801–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCudden CR, Willard FS, Kimple RJ, Johnston CA, Hains MD, Jones MB, Siderovski DP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1745:254–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natochin M, Lester B, Peterson YK, Bernard ML, Lanier SM, Artemyev NO. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40981–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson YK, Bernard ML, Ma H, Hazard S, 3rd, Graber SG, Lanier SM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33193–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takesono A, Cismowski MJ, Ribas C, Bernard M, Chung P, Hazard S, 3rd, Duzic E, Lanier SM. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33202–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willard FS, Low AB, McCudden CR, Siderovski DP. Cell Signal. 2007;19:428–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siderovski DP, Willard FS. Int J Biol Sci. 2005;1:51–66. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du Q, Stukenberg PT, Macara IG. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izumi Y, Ohta N, Hisata K, Raabe T, Matsuzaki F. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:586–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nipper RW, Siller KH, Smith NR, Doe CQ, Prehoda KE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701812104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaefer M, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A, Knoblich JA. Curr Biol. 2000;10:353–62. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afshar K, Willard FS, Colombo K, Johnston CA, McCudden CR, Siderovski DP, Gonczy P. Cell. 2004;119:219–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colombo K, Grill SW, Kimple RJ, Willard FS, Siderovski DP, Gonczy P. Science. 2003;300:1957–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1084146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiser O, Qian X, Ehlers M, Ja WW, Roberts RW, Reuveny E, Jan YN, Jan LY. Neuron. 2006;50:561–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webb CK, McCudden CR, Willard FS, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP, Oxford GS. J Neurochem. 2005;92:1408–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willard MD, Willard FS, Li X, Cappell SD, Snider WD, Siderovski DP. Embo J. 2007;26:2029–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambi BS, Hains MD, Waters CM, Connell MC, Willard FS, Kimple AJ, Pyne S, Siderovski DP, Pyne NJ. Cell Signal. 2006;18:971–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho H, Kehrl JH. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:245–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimple RJ, Willard FS, Siderovski DP. Mol Interv. 2002;2:88–100. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke TJ, Loniello KR, Beebe JA, Ervin KM. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6:183–94. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drees BE, Weipert A, Hudson H, Ferguson CG, Chakravarty L, Prestwich GD. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6:321–30. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikiforov TT, Simeonov AM. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2003;6:201–12. doi: 10.2174/138620703106298383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owicki JC. J Biomol Screen. 2000;5:297–306. doi: 10.1177/108705710000500501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker GJ, Law TL, Lenoch FJ, Bolger RE. J Biomol Screen. 2000;5:77–88. doi: 10.1177/108705710000500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prystay L, Gagne A, Kasila P, Yeh LA, Banks P. J Biomol Screen. 2001;6:75–82. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 2. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szmacinski H, Terpetschnig E, Lakowicz JR. Biophys Chem. 1996;62:109–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02199-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Malak H, Lakowicz JR. Biophys J. 1995;68:342–50. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80193-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Youn HJ, Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR. Anal Biochem. 1995;232:24–30. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.9966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akula N, Chen YS, Hennessy K, Schulze TG, Singh G, McMahon FJ. Biotechniques 2002. 32;1072–6:1078. doi: 10.2144/02325rr02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonin PD, Erickson LA. Anal Biochem. 2002;306:8–16. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan W, Sun L, Liu J, Wu X, Zhang L, Yan M. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1138–42. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu TM, Chen X, Duan S, Miller RD, Kwok PY. Biotechniques. 2001;31:560, 562, 564–8. doi: 10.2144/01313rr01. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang TT, Huang ZT, Dai Y, Chen XP, Zhu P, Du GH. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:447–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11473–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yasgar A, Shinn P, Michael S, Zheng W, Jadhav A, Auld D, Austin C, Inglese J, Simeonov A. JALA. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jala.2007.12.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. In: The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Walker JM, editor. Humana Press; 2005. pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Willard FS, Kimple AJ, Johnston CA, Siderovski DP. Anal Biochem. 2005;340:341–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willard FS, Siderovski DP. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:320–38. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cleveland PH, Koutz PJ. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2005;3:213–25. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niles WD, Coassin PJ. Assay Drug Devel Technol. 2005;3:189–202. doi: 10.1089/adt.2005.3.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hill AV. J Physiol (London) 1910;40:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang X. J Biomol Screen. 2003;8:34–8. doi: 10.1177/1087057102239666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seethala R, Fernandes PB. Handbook of drug screening. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Thomas C, Wang Y, Huang R, Southall N, Shinn P, Smith J, Austin C, Auld D, Inglese J. J Med Chem. doi: 10.1021/jm701301m. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Jadhav A, Lokesh GL, Klumpp C, Michael S, Austin C, Natarajan A, Inglese J. Anal Biochem. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.11.039. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]