Abstract

Syntheses of soluble tetrabenzoporphyrins (TBP) and tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrins (TNP), with multiple substituents in the conjugated aromatic rings but bearing no substituents in the meso-positions, is reported. Both types of porphyrins were obtained by direct aromatization of precursor porphyrins, annealed with either cyclohexene or dihydronaphthalene fragments. TBPs and TNPs possess powerful absorption bands in the near-infrared (λ 610-710 nm, ϵ = 100,000-300,000 M-1 cm-1) and exhibit strong luminescence. Free bases and Zn complexes fluoresce with quantum yields of up to 50%, whereas Pd and Pt complexes phosphoresce in solutions at ambient temperatures. Remarkably, the phosphorescence quantum yields of Pd and Pt TBPs reach as high as 20-50%, which places them among the brightest near-infrared phosphors known to date.

Introduction

Porphyrins extended via conjugation with exocyclic aromatic rings form a large group of tetrapyrroles that have received much attention in the recent years.1 This interest is explained primarily by the photophysical effect of the π-conjugation, known to induce red shifts in the absorption spectra of porphyrins. Absorption in the red region of the spectrum is generally useful for those biomedical applications, which rely on exogenous dyes and/or contrast agents, e.g., PDT,2 in vivo optical sensing and imaging.3 Potential applications of π-extended porphyrins, therefore, exist primarily in the biomedical field3b,4,5 but also include the design of optical limiters6 and other nonlinear optical materials,7 as well as the development organic semiconductors,8 sensitizers for photovoltaic cells9 and fluorescent STM enhancers.10

Our interest in π-extended porphyrins stems from their usefulness as probes for biological oxygen measurements using phosphorescence quenching.11 Pt and Pd porphyrins show high rates of intersystem crossing from their excited singlet states to the triplet states, from which they decay by emitting phosphorescence.12 The triplet lifetimes of Pt and Pd porphyrins in solutions at ambient temperatures are usually in the order of tens to hundreds of microseconds, which makes their phosphorescence extremely sensitive to oxygen. For biomedical applications, such as oxygen imaging in tissue in vivo,3b,13 it is crucial that the absorption bands of the phosphorescent sensors overlap minimally with those of endogenous tissue chromophors (e.g., hemoglobin, myoglobin, cytochromes, etc.). Accordingly, dyes with absorption in the near-infrared and with strong oxygen-dependent phosphorescence have been the focus of our interest. While a large number of porphyrinoids with absorption in the infrared are known to date (e.g., chlorophylls, expanded porphyrins, phthalocyanines, etc.), the list of compounds that simultaneously possess strongly emissive triplet states is very short.14 Some metal complexes of symmetrically π-extended porphyrins, i.e., tetrabenzoporphyrins (TBPs) and tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrins (TNPs) (Chart 1), apparently combine both of these properties and, in fact, are superior to the other chromophors due to their particularly intense and narrow transitions in the near-infrared window of tissue.15

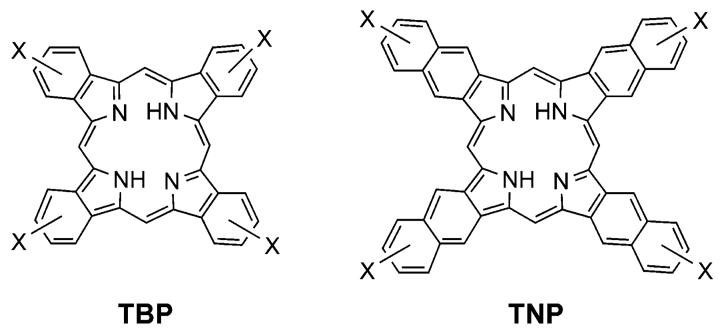

CHART 1.

Some water-soluble Pd meso-tetraaryltetrabenzoporphyrins (Ar4TBP) indeed have been shown to be effective as in vivo phosphorescent oxygen indicators.3b,15a,b,16 meso-Tetraarylated TNPs (Ar4TNP), although studied much less,17 also revealed potential in the oxygen-sensing application.15b,c At the same time, meso-unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs (Chart 1) and their metal complexes have remained practically unexplored in this, as well as in many other, areas of research. This is due largely to the difficulties in their synthesis, their extremely poor solubility and strong aggregation.

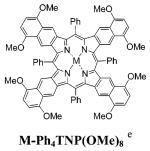

Metal complexes of meso-unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs, if made adequately soluble, are on the other hand likely to be very potent luminescent chromophores. Core macrocycles in their meso-tetraarylated analogues (Ar4TBPs and Ar4TNPs), which already exhibit quite strong luminescence, are severely nonplanar.18,40b,41 Nonplanarity is known to dramatically affect photophysical properties of porphyrins19 by shifting their absorption bands to the red20 and by reducing their luminescence quantum yields.21 According to both the X-ray data8b,c and the computational studies,22 TBPs and TNPs possess nearly ideally planar geometries. Therefore, it would be reasonable to expect that the luminescence quantum yields of TBPs and TNPs would be considerably higher than those of nonplanar Ar4TBPs and Ar4TNPs. Given that the absorption Q-bands of TBPs and TNPs are already positioned in the red as a consequence of the π-conjugation, these porphyrins should be superior as biological luminescent sensors.

Understanding the effects of nonplanarity is interesting not only for practical reasons. The interplay between the porphyrin structure and porphyrin photophysics has been intensely discussed in the recent literature.19,20,23 Not surprisingly, only a few experimental studies address the effects of nonplanarity in π-conjugated porphyrins,6d,15c,24,25 which is explained by their limited synthetic availability. In the past several years considerable progress has been made in the synthesis of meso-tetraarylated extended porphyrins (vide infra), and some of studies of their photophysical properties have been conducted. At the same time, soluble, nonaggregating planar TBPs and TNPs still remain a much less accessible target. Synthesis of these molecules constitutes the main focus of the present work.

Synthesis of meso-unsubstituted tetrabenzoporphyrin (TBP) was originally described by Helberger and co-workers26 and later by Linstead and co-workers.27 The TBP macrocycle was assembled by self-condensing o- cyanoacetophenone in the presence of metal salts at high temperature,26 an approach resembling classic phthalocyanine chemistry. A number of similar precursors, such as o-acetylbenzoic acid,28 phthalimides,29 phthalimidines,26,27,30 isoindoles31 and isoindoline,32 were used later to prepare differently substituted TBPs. The first synthesis of tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrin (TNP) also relied on the “template condensation” method.33 TNP was synthesized by condensing 3-carboxymethyl-5,6-benzophthalimidine with Zn acetate at high temperature. Several peripherally substituted TNPs, as well as isomeric tetranaphtho[1,2]porphyrins, were later prepared by similar methods from the corresponding benzophthalimidines or naphthalenedicarboximides.34

Aside from low yields and the large number of side products, the template condensation approach suffers because of the extremely harsh conditions required for the macrocycle assembly (i.e., fusion at 350-400 °C). Only a few TBPs and TNPs with inert substituents could be synthesized using this method.29b,30b,31,32 Over the past decade, several new approaches to π-extended porphyrins have emerged, all of them relying on more traditional porphyrin chemistry. A number of π-extended porphyrins were synthesized by Lash and co-workers and Ono and co-workers from the corresponding porphyrinogenic pyrroles, annealed with external aromatic rings.1b,35,36 Applying the same methodology to tetrabenzo- and tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrins, however, was impossible because of the very low stability of the required isoindoles.37 As a result, approaches based on the use of masked isoindole moiety received increasing attention. Two methods of synthesis of the TBP system have been subsequently devised by Cavaleiro’s38 and Ono’s groups.39 In the first method, TBP was synthesized form the precursor cyclohexenoporphyrin by base-catalyzed elimination of sulfinate, followed by oxidation with DDQ.38 In the second, TBP, TNP and their meso-arylated analogues were synthesized by thermal extrusion of ethylene from porphyrins fused with bicyclo[2.2.2]octadiene fragments.39 A recent version of the latter approach makes it possible to synthesize polyfunctionalized TBPs at low temperatures;39e however, the synthesis of bicyclo-fused pyrroles themselves is rather complicated, and no TNPs with substituents in the fused aromatic rings could be produced by this method.

In the course of our own work on the synthesis of polyfunctionalized π-extended porphyrins we came across a useful strategy based on the direct oxidative aromatization of precursor porphyrins, annealed with nonaromatic hydrocarbon rings.5,40,41,42 Using this method, a variety of Ar4TBPs5,40 and Ar4TNPs41 were synthesized in good yields from readily available starting materials. In the present paper we extend our methodology on the synthesis of soluble meso-unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs and report their basic photophysical properties.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of meso-Unsubstituted Tetrabenzoporphyrins (TBPs)

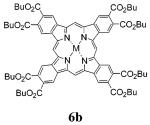

Synthesis of TBP-octaesters 6a,b is shown in Scheme 1. Esters 1a,b were obtained from commercially available 1,2,3,6-tetrahydrophthalic anhydride using standard procedures. Conversion of 1a (R = Me) into sulfone 2a and then into pyrroles 3a and 4a followed the published method.40b The same general procedures were used in the case of dibutoxycarbonyl derivatives, although both sulfone 2b and pyrrole ester 3b (X = Bn) were isolated as oils. To allow adequate characterization, these oils could be purified by simple flash chromatography (90-95% purity). Benzyl ester 3b was subjected to Pd-catalyzed hydrogenolysis, followed by decarboxylation of the pyrrole acid to give pyrrole 4b in 82% overall yield. Alternatively, tert-butyl ester 3c could be used as a precursor to 4b. 3c has an advantage of being a solid compound, and its conversion into 4b could be accomplished in a single step by being treated with TFA. However, the yield of 4b in this case was only 30-40%.

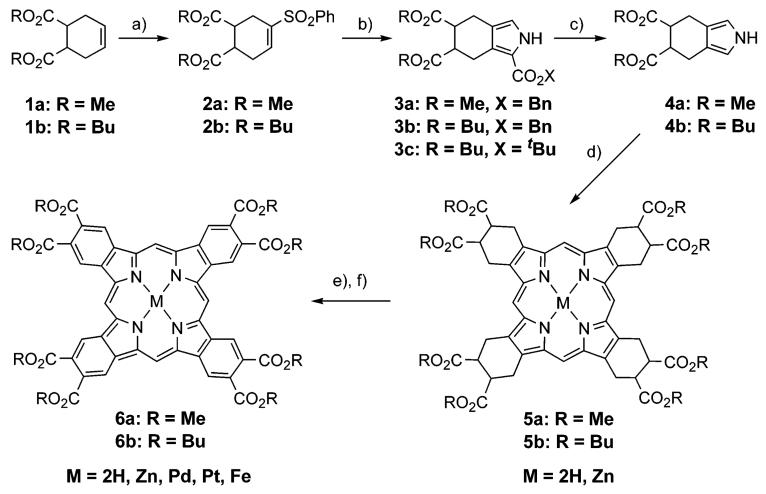

SCHEME 1a. a Reagents and conditions.

(a) (i) PhSCl, CH2Cl2, rt; (ii) MCPBA, CH2Cl2; (iii) DBU (80-85% for 3 steps); (b) CNCH2CO2X, tBuOK, THF, 0 °C (60-95%); (c) for R = Bn: (i) H2, Pearlman catalyst, THF-MeOH-Et3N, rt; (ii) (CH2OH)2, reflux, 30 min (82-90% for 2 steps); for R = tBu: TFA-CH2Cl2, Ar, rt, 30 min (30-40%); (d) (i) (CH2O)n, PhH, TsOH·H2O, Ar, reflux, 6-8 h, then air, (rt), overnight (30-45%); (ii) for M = Zn: Zn(OAc)2·2H2O, THF, reflux, 15 min (95-97%); (e) R = Bu: DDQ, toluene, reflux (95-97%); R = Me: DDQ, dioxane, reflux (20-96%); (f) PdCl2 or PtCl2, PhCN, reflux, Pd: 5-10 min, Pt: 7-8 h (84-90%), or Fe/FeCl2·4H2O, CH3CH2CO2H, Ar, reflux 1 h (74%).

Syntheses of tetracyclohexenoporphyrins (TCHPs) 5a,b from pyrroles 4a,b followed the classic synthesis of octaethylporphyrin (OEP).43 Porphyrin 5b with eight butoxycarbonyl groups was obtained in a higher yield (40-45%) than its octamethoxycarbonylated analogue 5a (30-40%). The increase in the yield was probably caused by the better solubility of the reaction intermediates, containing multiple butoxycarbonyl residues. Similarly, porphyrin 5b is very well soluble in most organic solvents (CH2Cl2, THF, diethyl ether), whereas porphyrin 5a is only moderately soluble.

TCHPs 5a,b were oxidized into the corresponding TBPs 6a,b by DDQ. The aromatization required substantially longer reaction times than did the recently reported aromatization of meso-tetraarylated TCHPs (Ar4TCHPs).5,40 However, the processes could be driven to completion, and the products were isolated in moderate (6a) to quantitative (6b) yields. The most striking difference between the reactivities of meso-unsubstituted TCHPs and Ar4TCHPs was that in the latter case it was necessary to preconvert Ar4TCHPs into their Cu, Ni or Pd complexes,5,40 whereas 5a,b could be oxidized into TBPs directly as free bases. Removing the metalation/demetalation step is obviously an advantage from the practical point of view but is also curious mechanistically.40b Metal assistance in the case of Ar4TCHPs was necessary because when these porphyrins, taken as free bases, were subjected to aromatization, they instantaneously formed dications, completely inert with respect to the oxidation. We have speculated that the protonation of the free bases occurred either directly, due to the acidification of the medium, or via the hydrogen abstraction from the solvent by an intermediate free-base cation radical.40b The fact that the rate of the aromatization appears to be reciprocal to the proton affinities of the free bases argues for the former pathway. The basicities of nonplanar Ar4TCHPs are much higher than those of their planar counterparts TCHPs,18b and the latter, as evidenced by our present results, can be aromatized as free bases.

Overall, more soluble octabutoxycarbonyl-TCHP 5b performed much better in the aromatization than its octamethoxycarbonyl analogue 5a, whose oxidation was additionally complicated by side reactions. For example, the oxidation of 5b and Zn-5b in toluene was completed after 4 h and required a 1.5- to 2-fold excess of DDQ. Under the same conditions, oxidation of 5a gave only undefined insoluble green solids, possibly products of the oxidative oligomerization. Aromatization of both 5a and Zn-5a could be accomplished in dioxane, but required a larger excess of DDQ (5- to 6-fold) and longer reaction times. Notably, neither Cu(II) nor Ni(II) nor Pd(II) complexes of 5a gave metallo-TBPs in good yields, whereas these metals have proven to be the best in the aromatization of Ar4TCHPs.40b

TBP 6b was further used to synthesize its Pd, Pt and Fe complexes, all of which showed excellent solubility in most common organic solvents. The structure and purity of the newly synthesized complexes were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR, MALDI-TOF spectrometry and elemental analysis. Pd and Pt derivatives were obtained by refluxing 6b with the corresponding chlorides in benzonitrile. For insertion of Fe, 6b was refluxed with a large excess of FeCl2 in propionic acid in the presence of iron wire. The UV-vis spectrum of the resulting Fe-6b was very similar to that of Fe(II) (bis)pyridine TBP.28a Fe-6b was stable on air for days both in the solid state and in solution when stored in the dark. A well-resolved NMR spectrum of Fe-6b suggests that this compound is a diamagnetic complex.44

Synthesis of meso-Unsubstituted Tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrins (TNP)

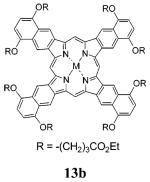

TNPs 13a,b were synthesized as shown in Scheme 2. The starting materials and reagents used in these syntheses were similar to those employed in the synthesis of the meso-tetraarylated analogues of porphyrin 13a (X = OMe), reported recently.41 The key starting material, 5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dihydronaphthalene 7, was prepared from butadiene and 1,4-benzoquinone45 and converted into its alkoxy derivatives using Williamson alkylation. Dimethoxy derivative 8a was prepared as described previously,45 whereas dialkoxy derivatives 8b and 8c, terminated with ester groups, were prepared from 7 and ethyl bromoacetate or ethyl 4-bromobutyrate, respectively.

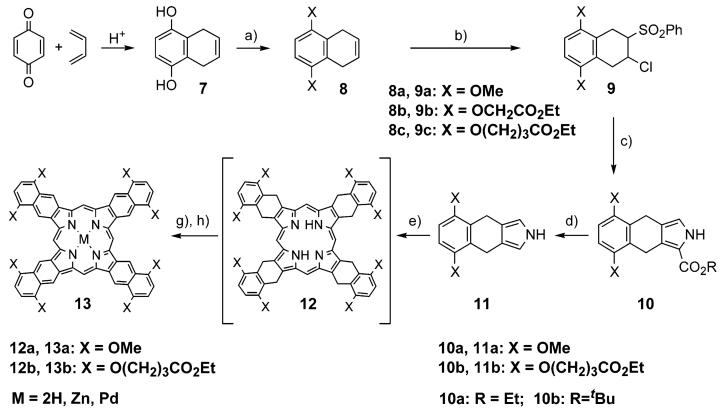

SCHEME 2a. a Reagents and conditions.

(a) Me2SO4 (for 8a), or BrCH2CO2Et (for 8b), or Br(CH2)3CO2Et-NaI (for 8c), K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 1-3 days (70-98%); (b) PhSCl, CH2Cl2, then MCPBA, CH2Cl2 (65-85%); (c) CNCH2CO2R, tBuOK, THF, reflux 30 min. (70-80%); (d) for R = Et: KOH, (CH2OH)2, reflux, 30 min (90-97%); for R = tBu: TFA-CH2Cl2, Ar, rt, 30 min (98%); (e) (CH2O)n, PhH, TsOH·H2O, Ar, reflux, 5 h, then air, rt, overnight; (g) DDQ, rt of reflux 30 min (e + g: 25-33%); (h) PdCl2 or Zn(OAc)2·2H2O, pyridine or PhCN/pyridine, reflux (80-95%).

α-Chlorosulfone 9a (X = OMe) was obtained from 8a following the published method.41 Synthesis of pyrrole 11a from 9a was performed as described earlier.41 9a was introduced into the modified Barton-Zard reaction with ethyl isocyanoacetate to give pyrrole ester 10a, which was further converted into 2,5-unsubstituted pyrrole 11a upon refluxing with KOH in ethylene glycol.

α-Chlorosulfones 9b,c were prepared from alkenes 8b,c by the same method as 9a.41 However, because both 9b and 9c contained ethyl ester groups, which were intended to be kept intact throughout the rest of the transformations, the use of ethyl isocyanoacetate in the subsequent Barton-Zard synthesis (step c in Scheme 2) was not feasible. Indeed, hydrolytic cleavage of the pyrrole-ethyl ester in the following step (step d in Scheme 2) would require heating this compound with KOH, and that would simultaneously destroy the peripheral ethyl ester groups. Consequently, we turned our attention to isocyanoacetates containing selectively cleavable benzyloxycarbonyl and tert-butoxycarbonyl groups. To our surprise, benzyl isocyanoacetate did not react with chlorosulfones 9a-c at all. tert-Butyl isocyanoacetate, on the other hand, reacted readily with sulfone 9c (X = O(CH2)3CO2Et, Scheme 2), giving pyrrole ester 10b in 70-80% yield, but did not react with 9b (X = OCH2CO2Et, Scheme 2). Only trace amounts of the corresponding pyrrole ester could be isolated, and there was a similar result when 9b reacted with ethyl isocyanoacetate.

The reasons for the unexpected behavior of benzyl isocyanoacetate is not well understood. In our past experience, benzyl isocyanoacetate did consistently show a somewhat lower reactivity in the Barton-Zard synthesis than did ethyl and tert-butyl isocyanoacetates but still usually gave pyrrole esters in reasonably good yields.40 Lash and co-workers, who originally introduced benzyl isocyanoacetate,46 used it successfully in many different syntheses;1b however, they also commented on its lower reactivity.46 On the other hand, for 9a-c the equilibrium between the vinyl sulfone47 and allyl sulfone forms48 is most certainly shifted toward the latter. Allyl sulfones are inactive in the Barton-Zard reaction, and thus, reduction in the concentration of the substrate (vinyl sulfone), combined with less active reagent (benzyl isocyanoacetate), led to such a dramatic decrease in the reaction rate, that virtually no condensation could be observed.

One possible explanation of the low reactivity of 9b is that this chlorosulfone, as well as the corresponding vinyl sulfone, possesses relatively easily ionizable CH2 groups in the side chains (-OCH2CO2R). Abstraction of a proton from one of these groups, under conditions of the Barton-Zard condensation49 would produce an anionic species, which is likely to be inert in the condensation with isocyanoacetates.

Pyrrole ester 10b, synthesized from sulfone 9c and tert-butyl isocyanoacetate, was cleaved and decarboxylated by TFA to give 11b in 98% yield. Pyrroles 11a (vide supra) and 11b were further reacted with formaldehyde under conditions similar to those used in the synthesis of 5a,b (Scheme 1). The UV-vis spectra of the reaction mixtures after the condensation closely resembled the spectra of OEP, evidencing formation of the intermediate octahydro-TNPs of type 12 (Scheme 2). These porphyrins, however, were not isolated. Instead, the mixtures were treated with DDQ or p-chloranil, and within minutes the conversion of 12 into TNPs was complete.

Octamethoxy-TNP 13a appeared to be insoluble in most organic solvents. It was purified by washing it with pyridine and THF, followed by recrystallization from refluxing benzonitrile. Porphyrin 13b, on the contrary, is very well soluble in many organic solvents, and it was purified by repetitive precipitation from CH2Cl2 by acetonitrile. Porphyrins 13a,b were isolated in 25-33% yields and converted into their Zn and Pd complexes by being reacted with the corresponding metal salts in refluxing pyridine or benzonitrile-pyridine mixtures.

NMR characterization of porphyrins 13a and Pd-13a was impossible due to their extremely low solubilities. The solubility of 13b and its complexes was significantly higher, but at the level of concentrations required for the NMR analysis aggregation still presented a considerable problem, especially for the Pd complex. Consequently, the aromatic signals in the spectra of Pd-13b appeared to be severely broadened. At the same time, the spectra of the free base 13b and of Zn-13b were quite well resolved, with aromatic resonances appearing at 11-12 ppm.

Photophysical Properties of meso-Unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs

Original photophysical studies of tetrabenzoporphyrin and its metal complexes were performed by Soloviev and co-workers50 and by Gouterman and co-workers.30c,51 Later, a number of investigators studied metallo-TBPs, primarily with respect to their applications.4a,15a,52 The photophysics of the TNP system,34a,17d,53 however, remains seriously understudied. Just the basic photophysical characteristics of Ar4TNPs have been recently reported,6d,15c,17g,41 whereas the properties of meso-unsubstituted TNPs have not yet been explored.

We have measured the absorption and emission characteristics of TBPs M-6b and TNPs M-13b and have compared them with those of Ph4TBPs5,40 and Ph4TNPs,41 substituted with similar functional groups in the fused aromatic rings. In this way, the influence of the side substituents on the photophysical properties can be excluded, whereas the effects of the nonplanar deformation and/or extra π-conjugation involving meso-aryl rings can be emphasized. The data are summarized in Table 1, and some absorption and emission spectra are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 1.

Selected Photophysical Data of meso-Unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs

| Absorptiona | Emissionb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porphyrine | M | Soret-band nm (lg ε) | Q-band nm (lg ε) | λmax, nm | Emission type,c ϕ (%)/τ (μs)d |

|

2H | 432 (5.40), 447 (5.51) | 626 (4.85), 673 (4.66) | 676, 748 | f, 27 |

| Zn | 460 (5.64) | 647 (5.14) | 647, 710 | f, 15 | |

| Pd | 426 (5.48) | 618 (5.20) | 770 | p, 23/400 | |

| Pt | 416 (5.23) | 609 (5.22) | 745 | p, 51/50 | |

|

2H | 471 (5.31) | 721 (5.30) | 733, 810 | f, 45 |

| Zn | 467 (5.43) | 708 (5.51) | 708, 781 | f, 18 | |

| Pd | 429 (5.15) | 696 (5.50) | 923 | p, 4/75 | |

|

2H | 483 (5.36) | 639 (1.37) | 733, 820 | f, 1.8 |

| Zn | 487 (5.59) | 668 (4.67) | 677, 746 | f, 3 | |

| Pd | 460 (5.40) | 636 (4.94) | 787 | p, 3/62 | |

|

2H | 509 (5.30) | 750 (5.00) | 957 | f, 13 |

| Zn | 504 (5.46) | 730 (5.23) | - | - | |

| Pd | 465 (5.23) | 720 (5.26) | 954 | p, 2.5/38 | |

Solvent: pyridine for Zn-6b, Pt-6b, M-13b and for all M-Ph4TNP(OMe)8; DMF for 6b, Pd-6b and for all M-Ph4TBP(CO2Me)8.

Solvent: DMF, deoxygenated by Ar for the phosphorescence measurements.

f = fluorescence, p = phosphorescence.

ϕ = emission quantum yield, τ = phosphorescence lifetime. Lifetime was not measured for fluorescence.

FIGURE 1.

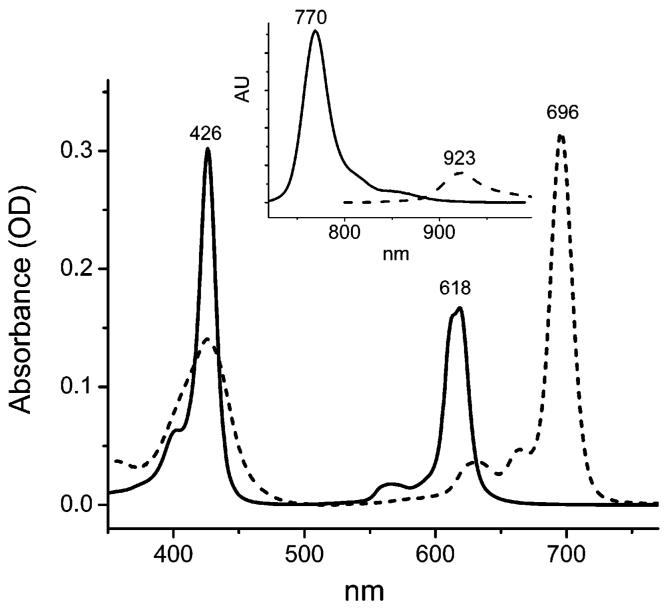

Absorption and fluorescence (inset) spectra of 6b (–) and 13b (- - -) in DMF. The spectra are scaled to reflect the relative extinction coefficients (absorption) and quantum yields (fluorescence).

FIGURE 2.

Absorption and phosphorescence (inset) spectra of Pd-6b (–) and Pd-13b (- - -) in deoxygenated DMF. The spectra are scaled to reflect the relative extinction coefficients (absorption) and quantum yields (phosphorescence).

The absorption bands of meso-unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs are blue-shifted by about 20-40 nm compared to the corresponding bands of Ar4TBPs and Ar4TNPs. This reflects the severe nonplanarity of the latter, confirmed earlier by both computational6d,15c and X-ray data.18,40b,41 Along with its own effect on the absorption spectra,20,21 the nonplanar deformation causes the meso-aryl rings in Ar4TBPs and Ar4TNPs to be partially drawn into the π-conjugation, which additionally contributes to the red shifts of the absorption bands.6d Consistent with flat structures of porphyrins of M-6b and M-13b, their Q-bands are much narrower and generally more intense than those of Ar4TBPs and Ar4TNPs. The emission bands of M-6b and M-13b are also much sharper and in some cases (e.g., fluorescence of 6b and 13b, Figure 1) display relatively well resolved vibronic structures. The Stokes shifts of the fluorescence of free bases 6b and 13b are very small (66 cm-1 for 6b; 94 cm-1 for 13b), whereas the Stokes shifts of the fluorescence of Ar4TBP free bases are typically in the order of several thousands of cm-1 (Table 1). All together, these facts consistently point toward the greatly increased rigidity of planar meso-unsubstituted porphyrins and suggest an increase in their radiative transitions.

Indeed, the values of the fluorescence quantum yields of meso-unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs free bases are in the range of 15-50%, which is significantly higher than for the analogous Ar4TBP(CO2Me)8’s and Ar4TNP(OMe)8’s (Table 1). As expected, Pd and Pt complexes of either TBPs or TNPs do not show fluorescence, which is due to a dramatic enhancement of their intersystem crossing. Instead, they emit from their triplet states. The quantum yields of the phosphorescence of TBPs Pd-6b and Pt-6b were found to be as high as 25% and 51% respectively, placing these metalloporphyrins among the brightest near-infrared phosphors known to date. The phosphorescent quantum yields of these porphyrins, as well as their triplet lifetimes are considerably larger than those of Ar4TBPs.

Based on the trends observed for TBPs and because of the high fluorescence quantum yield of 13b (45%), a similarly high quantum yield of the phosphorescence of Pd-TNP was expected. To our surprise, the phosphorescence of Pd-13b appeared to be quite moderate (ϕ = 4%), resembling that of Pd-Ph4TNP(OMe)8 (ϕ = 2.5%).54 It is possible that the lower emission yield of Pd-13b is due to the very low energy of the triplet band itself (λmax = 923 nm). Such a low energy triplet state is probably effectively overlapped by many ground-state vibrations, which enhance the rate of its internal conversion and cause the decrease in the emission quantum yield. Nevertheless, the phosphorescence quantum yield of Pd-13b, although below expected, is still entirely adequate for considering this chromophor in practical biological applications.

In conclusion, a convenient method of synthesis of meso-unsubstituted tetrabenzo- (TBP) and tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrins (TNP) with solubilizing groups at the periphery is described. The porphyrins were synthesized in 33-45% yields from readily available precursors. TBPs and TNPs and their metal complexes exhibit powerful absorption bands in the red region of the spectrum and luminesce with quantum yields of up to 50%. This places them among the brightest near-infrared absorbing luminescent tetrapyrroles known to date. Because of their exceptionally strong phosphorescence in solutions at ambient temperatures, Pd and Pt complexes of meso-unsubstituted π-extended porphyrins show great promise as luminescent probes for biological applications.

Experimental Section

Ethyl isocyanoacetate,55 benzyl isocyanoacetate46 and tert- butyl isocyanoacetate56 were prepared according to the published methods. Dimethyl 1,2,3,6-tetrahydrophthalate 1a was obtained from 1,2,3,6-tetrahydrophthalic anhydride as described previously.57 5,8-Dihydroxy-1,4-dihydronaphthalene 745 and 5,8-dimethoxy-1,4-dihydronaphthalene 8a45 were synthesized as reported previously. Vinyl sulfone 2a40b and α-chlorosulfone 9a41 were prepared following the published methods. Pyrrole esters 3a40b and 10a41 and pyrroles 4a40b and 11a41 were synthesized according to the published procedures. The equipment used for the analytical characterization of the compounds was described elsewhere.40b,41 Melting points are reported uncorrected.

Dibutyl 1,2,3,6-Tetrahydrophthalate (1b)

1b was obtained from 1,2,3,6-tetrahydrophthalic anhydride by a standard esterification method. 1,2,3,6-Tetrahydrophthalic anhydride (15 g, 99 mmol), butyl alcohol (40 mL), benzene (100 mL) and TsOH·H2O (0.1 g, 0.53 mmol) were refluxed with a Dean-Stark refluxing condenser until the separation of water stopped. NaHCO3 (0.5 g, 5.95 mmol) was added to the mixture and the excess of butyl alcohol was removed in a vacuum. The resulting material was dissolved in diethyl ether (100 mL), washed with 10% aqueous Na2CO3 (100 mL) and dried over K2CO3. After evaporation of the solvent, 1b was obtained as a colorless oil. Yield: 21.1 g, 75%. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 5.65 (s, 2H), 4.07 (t, 4H, J = 6.5 Hz), 3.02 (m, 2H), 2.56-2.31 (m, 4H) 1.58 (m, 4H), 1.34 (m, 4H), 0.91 (t, 6H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.3, 125.2, 64.42, 39.8, 30.6, 25.9, 19.2, 13.7.

Vinyl Sulfone (2b)

Synthesis of sulfone 2b from the ester 1b followed the general procedure described previously.58 The product was purified by flash chromatography on a short silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2) and isolated as a yellow oil. Yield: 83%. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.85-7.50 (m, 5H), 7.06 (d, 1H, J = 2 Hz), 4.03-3.86 (m, 4H), 3.10 (m, 1H), 3.00 (m, 1H), 2.90 (m, 1H), 2.60 (m, 3H), 1.45 (m, 4H), 1.28 (m, 4H), 0.88 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 172.1, 171.8, 139.2, 138.5, 136.8, 133.5, 129.3, 128.3, 128.2, 65.1, 39.7, 39.0, 30.7, 30.6, 26.6, 24.4, 19.3, 13.9.

Pyrrole Esters (3b,c)

Esters 3b,c were synthesized from vinyl sulfone 2b and the corresponding alkyl isocyanoacetates following the published method,49d used previously to synthesize pyrrole 3a from sulfone 2a and alkyl isocyanoacetates.40b

Benzyl ester 3b was purified by chromatography on a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2) and isolated as a yellow oil. Yield of 3b: 65%. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.89 (br s, 1H), 7.42-7.31 (m, 5H), 6.67 (d, 1H, J = 1.5 Hz), 5.29 (m, 2H), 4.06 (m, 4H), 3.41-2.83 (m, 6H), 1.56 (m, 4H), 1.32 (m, 4H), 0.89 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 174.5, 173.3, 170.3, 136.6, 128.7, 128.3, 128.2, 127.3, 119.8, 119.3, 117.8, 65.9, 64.8, 64.7, 41.2, 41.1, 30.7, 24.1, 22.6, 19.6, 16.3, 13.9.

tert-Butyl ester 3c was purified by flash chromatography on a short silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 30:1), followed by recrystallization from methanol. Yield of 3c: 60%, colorless crystals, mp 88-90 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.96 (br s, 1H), 6.63 (d, 1H, J = 3 Hz), 4.07 (m, 4H), 3.32-2.82 (m, 6H), 1.59-1.55 (s+m, 9+4H), 1.34 (m, 4H), 0.89 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.5, 173.4, 161.6, 124.5, 119.5, 119.4, 118.4, 80.7, 64.74, 64.69, 41.23, 41.19, 30.8, 28.7, 24.1, 22.9, 19.3, 13.8. Anal. Calcd for C25H35NO6: C, 65.53; H, 8.37; N, 3.32. Found: C, 65.42; H, 8.33; N, 3.44.

Pyrrole 4b

4b was synthesized from either benzyl ester 3b or tert-butyl ester 3c following the procedures described earlier for the synthesis of pyrrole 4a.40b 4b was purified by flash chromatography on a short silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2). Yield: 82% (from 3b) or 35% (from 3c), colorless oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.32 (br s, 1H), 6.37 (d, 2H, J = 2 Hz), 3.97 (m, 4H), 3.10-2.80 (m, 6H), 1.50 (m, 4H), 1.25 (m, 4H), 0.83 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.7, 116.6, 113.5, 64.6, 41.7, 30.7, 22.8, 19.2, 13.7.

Tetracyclohexenoporphyrins (5a,b)

Syntheses of porphyrins 5a,b followed the procedure described for the synthesis of OEP.43 The pyrrole (4a or 4b, 1.6 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (90 mL), the reaction flask was flushed with Ar and shaded from light by a piece of aluminum foil. Formaldehyde (37% aqueous solution, 0.18 mL) and TsOH·H2O (10 mg, 0.05 mmol) were added, and the mixture was refluxed with a Dean-Stark condenser for 6-8 h under Ar. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the flow of air was passed through the mixture overnight under continuous stirring. The solvent was evaporated, and the remaining material was purified on a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF; 5a, 20:1-10:1; 5b, 100:1-50:1). The red fraction was collected, evaporated to dryness, dissolved in a small volume of THF, layered over with ∼20-fold excess volume of MeOH-H2O (3:1) and left overnight in a closed vial. The resulting precipitate was collected by centrifugation and dried in a vacuum. Yield of 5a: 30-40%, red powder. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 9.98-9.85 (m, 4H), 4.70-3.60 (m, 48H), -3.80 (br, 4H); MALDI-TOF: m/z 990.82, calcd 990.35; UV-vis, CH2Cl2, λmax nm (ϵ) 399 (185,000), 498 (14,300), 533 (13,000), 566(7,000), 620 (5,000). Anal. Calcd for C52H54N4O16: C, 63.02; H, 5.49; N, 5.65. Found: C, 62.28; H, 5.31; N, 5.51. Yield of 5b: 40-45%, red powder. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 9.95-9.80 (m, 4H), 4.50-3.80 (m, 40H), 1.90-0.80 (m, 56H), -3.85 (br, 4H); MALDI-TOF: m/z 1329.02, calcd 1326.73; UV-vis, CH2Cl2, λmax nm (ϵ) 400 (180,000), 498 (14,000), 533 (13,000), 566 (7,000), 620 (5,000). Anal. Calcd for C76H102N4O16: C, 68.75; H, 7.74; N, 4.22. Found: C, 68.37; H, 7.57; N, 4.19.

Zn Tetracyclohexenoporphyrins (Zn-5a,b)

An excess of Zn(OAc)2·2H2O (100 mg, ∼0.5 mmol) was added to a solution of porphyrin 5a or 5b (0.1 mmol) in THF (20 mL), and the mixture was refluxed for 15-20 min. The conversion was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy (solvent THF). The reaction was stopped when the absorption band of the free base porphyrin (λmax = 620 nm) disappeared. The mixture was evaporated to dryness, and the remaining material was purified on a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1). The first pink fraction was collected and evaporated to dryness to give the product as a red amorphous solid. Yield of Zn-5a: 95-97%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.95-9.80 (m, 4H), 4.80-3.60 (m, 48H); MALDI-TOF m/z 1054.05, calcd 1052.27; UV-vis, CH2Cl2, λmax nm (ϵ) 402 (240,000), 533 (16,000), 568 (12,000). Anal. Calcd for C52H52N4O16Zn: C, 59.23; H, 4.97; N, 5.31. Found: C, 58.80; H, 4.96; N, 5.20. Yield of Zn-5b: 95-97%. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.89 (s, 4H), 4.60-4.40 (m, 16H), 4.2-4.0 (m, 24H), 1.60 (m, 16H), 1.36 (m, 16H0, 0.85 (m, 16H); MALDI-TOF m/z 1405.51, calcd 1403.67; UV-vis, CH2Cl2, λmax nm (ϵ) 402 (220,000), 533 (16,000), 568 (12,000). Anal. Calcd for C77H103N4O16Zn: C, 65.77; H, 7.38; N, 3.98. Found: C, 65.25; H, 7.45; N, 3.60.

Tetrabenzoporphyrins (6a,b and Zn-6a,b)

To synthesize porphyrins 6a and Zn-6a, 5a or Zn-5a (0.1 mmol), respectively, was dissolved in dioxane (75 mL), DDQ (450 mg, 2.0 mmol) was added, and the mixture was refluxed under Ar for 3 h. An extra portion of DDQ (450 mg, 2.0 mmol) was added and the mixture was refluxed for additional 2-3 h. The conversion was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy (solvent CH2Cl2-pyridine).39d If required, more DDQ was added and the refluxing was continued until the conversion was complete. In the case of 6b or Zn-6b, 5b or Zn-5b (0.1 mmol), respectively, was dissolved in toluene (100 mL), DDQ (363 mg, 1.6 mmol) was added, and the mixture was refluxed under Ar for 4-5 h, after which the conversion (monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy) was complete.

The workup in all the cases, i.e., 6a, Zn-6a, 6b and Zn-6b, followed the same protocol. The mixture was reduced to a small volume (5-10 mL), CH2Cl2 (150 mL) was added, and the resulting solution was washed with 10% aqueous Na2SO3 and 10% aqueous Na2CO3 and dried over K2CO3. After evaporation of the solvent, the resulting material was purified on a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1). The bright green fraction was collected, its volume was reduced down to about 5 mL, and the solution was layered over with methanol and left in a closed vial overnight. The resulting green precipitate was collected by centrifugation and dried in a vacuum. Yield of 6a:39f 20-30%, green powder. Yield of Zn-6a:39d 96%, green powder. Yield of 6b: 95%, green powder. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 9.55 (s, 4H), 9.22 (s, 8H), 4.74 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz); 2.08 (m, 16H), 1.74 (m, 16H), 1.19 (t, 24H, J = 7.5 Hz), -5.06 (br, 2H); 1H NMR (TFA-d) δ 11.99 (s, 4H), 10.52 (s, 8H), 4.90 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz); 2.13 (m, 16H), 1.75 (m, 16H), 1.20 (t, 24H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 168.1, 131.7, 122.1, 94.0, 66.4, 31.2, 19.7, 14.3; MALDI-TOF m/z 1311.54, calcd 1310.60; UV-vis, DMF, λmax nm (ϵ) 404 (46,500), 432 (240,000), 447 (325,000), 579 (20,000), 617 (66,500), 626 (70,000), 673 (46,000). Anal. Calcd for C76H86N4O16: C, 69.60; H, 6.61; N, 4.27. Found: C, 69.19; H, 6.66; N, 4.54. Yield of Zn-6b: 97%, green powder. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5, 50 °C) δ 11.25 (s, 4H), 10.26 (s, 8H), 4.85 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz); 2.05 (m, 16H), 1.69 (m, 16H), 1.11 (t, 24H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (pyridine-d5, 50 °C) δ 169.5, 144. 9, 140.6, 132.2, 97.6, 66.5, 31.6, 20.1, 14.4; MALDI-TOF m/z 1373.11, calcd 1372.52; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) 433 (55,-400), 460 (434,000), 589 (22,200), 647 (139,000). Anal. Calcd for C76H84N4O16Zn: C, 66.39; H, 6.16; N, 4.08. Found: C, 66.20; H, 6.19; N, 4.19.

Pd and Pt Tetrabenzoporphyrins (Pd-6b and Pt-6b)

Free base tetrabenzoporphyrin 6b (35 mg, 0.027 mmol) was dissolved in PhCN (5 mL), PdCl2 (10 mg, 0.053 mmol) or PtCl2 (15 mg, 0.053 mmol) was added, and the mixture was refluxed under Ar. The metal insertion required 5-10 min in the case of Pd complex and 8 h in the case of Pt complex. The conversion was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy (solvent DMF), and the reaction was stopped when the free-base Q-band (λmax = 673 nm) disappeared. The mixture was evaporated to dryness at 0.1 mmHg, and the remaining material was washed with methanol, dried, and purified on a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1) to give the product as a blue-green amorphous solid. Yield of Pd-6b: 90%. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5, 70 °C) δ 9.74 (br s, 4H), 9.33 (s, 8H), 4.95 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz); 2.20 (m, 16H), 1.83 (m, 16H), 1.28 (t, 24H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (pyridine-d5, 70 °C) δ 168.7, 137.3, 135.1., 132.4, 124.2, 97.3, 66.7, 31.6, 20.1, 14.4. MALDI-TOF m/z 1413.33, calcd1414.49; UV-vis, DMF, λmax nm (ϵ) 426 (305,000), 565 (17,000), 618 (160,000). Anal. Calcd for C76H84N4O16Pd: C, 64.47; H, 5.98; N, 3.96. Found: C, 64.29; H, 5.62; N, 4.03. Yield of Pt-6b: 84%. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5, 80 °C) δ 9.99 (s, 4H), 9.46 (s, 8H), 4.92 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz); 2.16 (m, 16H), 1.80 (m, 16H), 1.23 (t, 24H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (pyridine-d5, 50 °C) δ 168.8, 137.3, 134.8, 132.6, 122.6, 98.1, 66.8, 31.8, 20.2, 14.5; MALDI-TOF m/z 1503.49, calcd 1503.55; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) 416 (170,000), 557 (19,000), 609 (165,000). Anal. Calcd for C76H84N4O16Pt: C, 60.67; H, 5.63; N, 3.72. Found: C, 59.84; H, 5.23; N, 3.92.

Fe tetrabenzoporphyrin (Fe-6b)

Porphyrin 6b (27 mg, 0.02 mmol) was dissolved in propionic acid (10 mL). FeCl2·4H2O (100 mg, 0.5 mmol) and iron wire (∼100 mg) were added, and the mixture was refluxed under Ar for ∼1 h. The conversion was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy (solvent DMF), and the reaction was stopped when the free-base Q-band (λmax = 673 nm) disappeared. The mixture was filtered, the filtrate was evaporated to dryness, and the remaining material was washed with methanol-pyridine mixture and dried in a vacuum. The product was isolated as a blue-green amorphous solid. Yield of Fe-6b: 20 mg, 74%. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5) δ 11.38 (s, 4H), 10.12 (s, 8H), 4.72 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz); 1.92 (m, 16H), 1.59 (m, 16H), 1.02 (t, 24H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (pyridine-d5) δ 169.5, 143.2, 143.3, 131.2, 121.7, 98.3, 66.4, 31.5, 19.9, 14.2; MALDI-TOF m/z 1365.17, calcd 1364.52; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) 422 (110,000), 446 (99,500), 613 (100,000). Anal. Calcd for C76H84N4O16Fe: C, 66.86; H, 6.20; N, 4.10. Found: C, 66.29; H, 6.45; N, 3.98.

5,8-Dialkoxy-1,4-dihydronaphthalenes (8b,c)

Synthesis of compound 8b generally followed the procedure described for the synthesis of 5,8-dimethoxy-1,4-dihydronaphthalene 8a.45 Ethyl bromoacetate was used in the present synthesis instead of dimethyl sulfate. Yield of 8b: 85%, colorless solid, mp 117-118 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 6.50 (s, 2H), 5.87 (s, 2H), 4.56 (s, 4H), 4.24 (q, 4H, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.35 (s, 4H), 1.28 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 174.2, 169.4, 125.7, 123.5, 108.5, 66.2, 61.3, 24.4, 14.3. Anal. Calcd for C18H22O6: C, 64.66; H, 6.63. Found: C, 64.50; H, 6.58. Compound 8c was synthesized using a similar procedure. A mixture of 5,8-dihydroxy-1,4-dihydronaphthalene 7 (3.24 g, 20 mmol), ethyl 3-bromobutirate (11.7 g, 9.0 mL, 60 mmol), NaI (1.5 g, 10 mmol) and K2CO3 (15 g) was refluxed in acetone (100 mL) for 48-60 h. The solid was filtered off, washed with CH2Cl2 (100 mL), and the filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting material was recrystallized from ethyl alcohol to afford 2c as a cream-colored solid. Yield of 8c: 5.45 g, 69%, mp 117-118 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 6.58 (s, 2H), 5.86 (s, 2H), 4.13 (q, 4H, 3J(H,H) = 6.5 Hz), 3.93 (t, 4H, J = 6 Hz), 3.25 (s, 4H), 2.51 (t, 4H, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.10 (m, 4H), 1.25 (t, 6H, J = 7.5 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.5, 150.4, 124.9, 123.8, 108.2, 67.2, 60.6, 31.2, 25.1, 24.5, 14.5. Anal. Calcd for C22H30O6: C, 67.67; H, 7.74. Found: C, 67.52; H, 7.77.

α-Chlorosulfones (9b,c)

Synthesis of compounds 9b,c generally followed the procedure described earlier for the synthesis of α-chlorosulfone 9a.41 The products were purified by flash chromatography on a silica gel column (eluent 9a, CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1; 9b, CH2Cl2) with subsequent crystallizations from ether-petroleum ether mixtures. Yield of 9b: 65%, yellowish solid, mp 111-112 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.95-7.53 (m, 5H), 6.53 (s, 2H), 4.85 (m, 1H), 4.85 (m, 1H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 4.53 (s, 2H), 4.23 (m, 4H), 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.48-3.26 (m, 4H), 1.26 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 174.3, 169.1, 150.4, 150.1, 138.2, 134.2, 129.4, 129.1, 123.4, 122.7, 109.8, 109.5, 66.5, 66.3, 64.4, 61.4, 51.8, 30.5, 24.6, 20.2, 14.3. Anal. Calcd for C24H27ClO8S: C, 56.41; H, 5.33. Found: C, 56.46; H, 5.27. Yield of 9c: 75%, yellowish solid, mp 86-87 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.92-7.55 (m, 5H), 6.60 (s, 2H), 4.86 (m, 1H), 4.13 (m, 4H), 3.90 (m, 4H), 3.70 (m, 1H), 3.38-3.15 (m, 4H), 2.47 (m, 4H), 2.10 (m, 4H), 1.25 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.5, 173.4, 150.4, 150.1, 138.4, 134.3, 129.5, 129.1, 122.3, 121.5, 109.2, 108.9, 67.4, 67.2, 64.5, 60.7, 52.0, 31.2, 31.1, 30.7, 25.0, 20.4, 14.5. Anal. Calcd for C28H35ClO8S: C, 59.30; H, 6.22. Found: C, 59.27; H, 6.18.

Pyrrole Ester (10b)

Compound 10b was prepared from α-chlorosulfone 9c and tert-butyl isocyanoacetate following the procedure described previously for the synthesis pyrrole ester 10a.41 The product was purified by flash chromatography on a short silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1), followed by recrystallization from methanol. Yield of 10b: 77%, light yellow crystals, mp 103-104 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.92 (br s, 1H), 6.81 (d, 1H, J = 2.5 Hz), 6.64 (s, 2H), 4.14 (m, 4H), 4.03 (m, 2H), 3.98 (t, 4H, J = 6 Hz), 3.80 (m, 2H), 2.55 (m, 4H), 2.13 (m, 4H), 1.57 (s, 9H), 1.25 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.6, 173.5, 161.7, 151.1, 150.8, 125.7, 125.3, 124.2, 119.3, 119.2, 118.1, 108.0, 107.9, 80.6, 67.3, 67.2, 60.6, 60.5, 31.3, 31.2, 28.7, 25.2, 25.1, 23.0, 21.2, 14.4, 14.3. Anal. Calcd for C29H39NO8: C, 65.77; H, 7.42; N, 2.64. Found: C, 65.71; H, 7.29; N, 2.66.

Pyrrole (11b)

tert-Butyl ester 10b (300 mg, 0.57 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (15 mL), and the solution was flushed with Ar for 5 min under stirring. The mixture was cooled on an ice bath, TFA (10 mL) was added, and the mixture was refluxed for 30 min. CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added to the mixture, after which it was poured into a beaker with ice-cold solution of Na2CO3 (10% aqueous, 100 mL). The resulting mixture was transferred into a separatory funnel, the organic layer was separated, the water phase was additionally extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 30 mL), and the combined organic solutions were washed with 10% aqueous Na2CO3 (50 mL). After drying over K2CO3, the solution was passed through a short silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1), and the solvent was evaporated to yield the product as a colorless solid. Yield of 11b: 255 mg, 98%. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.09 (br s, 1H), 6.67 (d, 2H, J = 2 Hz), 6.63 (s, 2H), 4.14 (q, 4H, J = 8 Hz), 3.98 (t, 4H, J = 6 Hz), 3.85 (s, 4H), 2.56 (t, 4H, J = 7 Hz), 2.14 (m, 4H), 1.26 (t, 6H, J = 7 Hz); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 173.7, 151.0, 126.8, 117.4, 113.1, 108.2, 67.4, 60.6, 31.5, 25.2, 21.2, 14.3.

Tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrins (13a,b)

The syntheses of porphyrins 13a,b from pyrroles 11a,b generally followed the procedure, described above for the synthesis of TCHPs 5a,b. The pyrrole (11a or 11b, 1.2 mmol) was dissolved in benzene (60 mL), and the solution was flushed with Ar. Formaldehyde (37% aqueous solution, 0.11 mL) and TsOH·H2O (30 mg, 0.16 mmol) were added to the mixture under vigorous stirring, and the mixture was refluxed for 4-5 h under Ar and then stirred overnight on air. The solvent was evaporated, and the remaining material was treated with DDQ (100 mg, 4 mmol). In the case of 13a, the reaction was performed in refluxing dioxane, whereas in the case of 13b, DDQ was added to the solution in CH2Cl2 at room temperature. In the latter case, the oxidation also could be done using p-chloranil (100 mg, 4 mmol) in refluxing toluene. The progress of the reaction was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy (13a in DMF; 13b in CH2Cl2). The spectrum changed gradually from the etio type, corresponding to the porphyrins of type 12 (Scheme 2) to characteristic TNP spectrum with an intense Q-band at ∼720 nm.

In the case of 13a, a green residue precipitated from the reaction mixture. It was collected by centrifugation and washed with pyridine and THF. For further purification, it was recrystallized from refluxing PhCN and dried in a vacuum. Yield of 13a: 25%, dark green powder. MALDI-TOF m/z 949.07, calcd 950.33; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) (86500), 471 (198,000), 656 (29,500), 721 (191,000). Anal. Calcd for C60H46N4O8: C, 75.77; H, 4.88; N, 5.89. Found: C, 75.24; H, 4.99; N, 5.75.

In the case of 13b, the reaction mixture was washed with 10% aqueous Na2SO3, with 10% aqueous Na2CO3, dried over K2CO3 and reduced in volume of about 5 mL. Acetonitrile (60 mL) was added, resulting in formation of a green precipitate. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with acetonitrile and methanol and dried in a vacuum. Yield of 13b: 33%, green powder. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5-PhNO2-d5, 1:1, 50 °C) δ 11.51 (s, 4H), 10.92 (s, 8H), 4.71 (br t, 16H), 4.56 (q, 16H, J = 7 Hz), 3.23 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz), 2.88 (m, 16H), 1.35 (t, 24H, J = 7 Hz), -1.27 (br s, 2H); MALDI-TOF m/z 1752.66, calcd 1750.75; 13C NMR (pyridine-d5-PhNO2-d5, 1:1, 80 °C) δ 174.4, 151.2, 127.6, 115.9, 105.6, 93.6, 69.5, 61.2, 32.6, 26.2, 15.0; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) 441 (90,000), 471 (205,000), 656 (31,500), 721 (199,500). Anal. Calcd for C100H110N4O24: C, 68.56; H, 6.33; N, 3.20. Found: C, 67.29; H, 6.02; N, 3.03.

Zn Tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrin (Zn-13b)

An excess of Zn(OAc)2·2H2O (30 mg, 0.16 mmol) was added to a solution of porphyrin 13b (17 mg, 0.01 mmol) in pyridine (20 mL), and the mixture was refluxed for 15-20 min. The conversion was monitored by UV-vis spectroscopy (solvent pyridine). The reaction was stopped when the absorption band of 13b (λmax = 722 nm) disappeared. The mixture was diluted with water, the green precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with methanol and dried in a vacuum. Yield of Zn-13b: 16 mg, 95%, green solid. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5) δ 11.80 (br s, 4H), 11.10 (br, 8H), 7.22 (br, 8H, ovlpd. w/solv), 4.60-4.53 (ovlpd. t+q, 16+16H), 3.15 (t, 16H, J = 7 Hz), 2.77 (m, 16H), 1.16 (t, 24H, J = 7 Hz); 13C NMR (pyridine-d5) δ 174.5, 151.1, 146.2, 138.2, 127.2, 115.5, 104.8, 92.6, 69.2, 61.1, 32.5, 25.6, 14.7; MALDI-TOF m/z 1815.50, calcd 1812.66; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) 439 (11,500), 467 (270,000), 645 (32,000), 674 (32,000), 708 (320,000). Anal. Calcd for C100H108N4O24Zn: C, 66.16; H, 6.00; N, 3.09. Found: C, 65.73; H, 5.90; N, 3.04.

Pd Tetranaphtho[2,3]porphyrin (Pd-13b)

Free-base porphyrin 13b (17 mg, 0.01 mmol) was dissolved in PhCN (5 mL), PdCl2 (5 mg, 0.028 mmol) was added, and the mixture was refluxed under Ar for 1-3 min. A few drops of pyridine were added, and the mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. The solvents were removed in a vacuum (0.1 mmHg), and the remaining material was washed with methanol, dried and purified on a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2-THF, 20:1) to give the product as a green amorphous solid. Yield of Pd-13b: 82%. 1H NMR (pyridine-d5, 100 °C) δ 9.71 (br s, 4H), 9.02 (br, 8H), 4.71 (br, 16H), 4.50 (br, 16H), 3.17 (br, 16H), 2.84 (br, 16H), 1.37 (br, 24H); 13C NMR (pyridine-d5, 80 °C) δ 174.0, 69.4, 60.8, 32.3, 26.0, 14.7; MALDI-TOF m/z 1856.58, calcd 1854.64; UV-vis, pyridine, λmax nm (ϵ) 428 (140,000), 633 (34,000), 665 (44,000), 696 (315,000). Anal. Calcd for C100H108N4O24Pd: C, 64.70; H, 5.86; N, 3.02. Found: C, 63.77; H, 5.42; N, 3.54.

Acknowledgment

Support of the grant EB003663-01 from the NIH (USA) and the contract 02-5403-21-2 with Anteon Inc. (USA) are gratefully acknowledged. A.V.C. acknowledges the support of the grant RFBR 04-03-32650-à from Russian Foundation for Basic Research. The authors thank Ms. Natalie Kim for proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Copies of the NMR spectra of newly synthesized porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1)(a).Lash TD. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Academic Press; New York: 2000. Chapter 10. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lash TD. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2001;5:267. [Google Scholar]; (c) Vicente MGH, Smith KM. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2004;8:26. [Google Scholar]

- (2)(a).Bonnett R. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1995;24:19. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sessler JL, Dow WC, Oconnor D, Harriman A, Hemmi G, Mody TD, Miller RA, Qing F, Springs S, Woodburn K, Young SW. J. Alloys Compd. 1997;249:146. [Google Scholar]; (c) Pandey RK. In ref 1a, Chapter 43. [Google Scholar]; (d) Brunner H, Schellerer KM. Monatsh. Chem. 2002;133:679. [Google Scholar]; (e) Moan J, Peng Q. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nyman ES, Hynninen PH. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2004;73:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3)(a).Young SW, Qing F, Harriman A, Sessler JL, Dow WC, Mody TD, Hemmi GW, Hao YP, Miller RA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:6610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vinogradov SA, Lo L-W, Jenkins WT, Evans SM, Koch C, Wilson DF. Biophys. J. 1996;70:1609. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79764-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liebsch G, Klimant I, Frank B, Holst G, Wolfbeis OS. Appl. Spectrosc. 2000;54:548. [Google Scholar]; (d) Minamitani H, Tsukada K, Sekizuka E, Oshio C. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003;93:227. doi: 10.1254/jphs.93.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kress M, Meier T, Steiner R, Dolp F, Erdmann R, Ortmann U, Ruck A. J. Biomed. Opt. 2003;8:26. doi: 10.1117/1.1528595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Licha K. Contrast Agents II. 2002;222:1. [Google Scholar]

- (4)(a).Lavi A, Johnson FM, Ehrenberg B. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1994;231:144. [Google Scholar]; (b) Friedberg JS, Skema C, Baum ED, Burdick J, Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF, Horan AD, Nachamkin I. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48:105. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Finikova OS, Galkin AS, Rozhkov VV, Cordero MC, Hagerhall C, Vinogradov SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4882. doi: 10.1021/ja0341687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6)(a).Chen PL, Tomov IV, Dvornikov AS, Nakashima M, Roach JF, Alabran DM, Rentzepis PM. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:17507. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brunel M, Chaput F, Vinogradov SA, Campagne B, Canva M, Boilot JP. Chem. Phys. 1997;218:301. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ono N, Ito S, Wu CH, Chen CH, Wen TC. Chem. Phys. 2000;262:467. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rogers JE, Nguyen KA, Hufnagle DC, McLean DG, Su WJ, Gossett KM, Burke AR, Vinogradov SA, Pachter R, Fleitz PA. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:11331. [Google Scholar]

- (7)(a).Perry JW, Mansour K, Lee IS, Wu X, Bedworth PV, Chen CT, Ng D, Marder SR, Miles P, Wada T, Tian M, Sasabe H. Science. 1996;273:1533. [Google Scholar]; (b) Krivokapic A, Anderson HL, Bourhill G, Ives R, Clark S, McEwan KJ. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:652. [Google Scholar]; (c) Srinivas N, Rao SV, Rao D, Kimball BK, Nakashima M, Decristofano BS, Rao DN. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2001;5:549. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dini D, Barthel M, Schneider T, Ottmar M, Verma S, Hanack M. Solid State Ionics. 2003;165:289. [Google Scholar]; (e) Calvete M, Yang GY, Hanack M. Synth. Met. 2004;141:231. [Google Scholar]

- (8)(a).Martinsen J, Pace LJ, Phillips TE, Hoffman BM, Ibers JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:83. [Google Scholar]; (b) Martinsen J, Pace LJ, Phillips TE, Hoffman BM, Ibers JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:83. [Google Scholar]; (c) Liou KY, Newcomb TP, Heagy MD, Thompson JA, Heuer WB, Musselman RL, Jacobsen CS, Hoffman BM, Ibers JA. Inorg. Chem. 1992;31:4517. [Google Scholar]; (d) Aramaki S, Sakai Y, Ono N. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004;84:2085. [Google Scholar]

- (9)(a).Yamashita K. Chem. Lett. 1982;1085 [Google Scholar]; (b) Yamashita K, Harima Y, Kubota H, Suzuki H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1987;60:803. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Guo XL, Dong ZC, Trifonov AS, Miki K, Mashiko S, Okamoto T. Nanotechnology. 2004;15:S402. [Google Scholar]

- (11)(a).Vanderkooi JM, Maniara G, Green TJ, Wilson DF. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:5476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rumsey WL, Vanderkooi JM, Wilson DF. Science. 1988;241:1649. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA. In: Handbook of Biomedical Fluorescence. Mycek M-A, Pogue BW, editors. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2003. Chapter 17. [Google Scholar]

- (12)(a).Eastwood D, Gouterman M. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1970;35:359. [Google Scholar]; (b) Callis JB, Gouterman M, Jones YM, Henderson BH. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1971;39:410. [Google Scholar]; (c) Callis JB, Knowles JM, Gouterman M. J. Phys. Chem. 1973;77:154. doi: 10.1021/j100621a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim DH, Holten D, Gouterman M, Buchler JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:4015. [Google Scholar]

- (13)(a).Soloviev VY, Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA. Appl. Opt. 2003;42:113. [Google Scholar]; (b) Soloviev VY, Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA. Appl. Opt. 2004;43:564. doi: 10.1364/ao.43.000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14)(a).Papkovsky DB, Ponomarev GV, Wolfbeis OS. Spectrochim. Acta A. 1996;52:1629. [Google Scholar]; (b) Castellano FN, Lakowicz JR. Photochem. Photobiol. 1998;67:179. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(1998)067<0179:awslos>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Singh A, Johnson LW. Spectrochim. Acta A. 2003;59:905. doi: 10.1016/s1386-1425(02)00258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15)(a).Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2. 1995;103 [Google Scholar]; (b) Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1997;411:597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rozhkov VV, Khajehpour M, Vinogradov SA. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:4253. doi: 10.1021/ic034257k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16)(a).Dunphy I, Vinogradov SA, Wilson DF. Anal. Biochem. 2002;310:191. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rietveld IB, Kim E, Vinogradov SA. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:3821. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ziemer LS, Lee WMF, Vinogradov SA, Sehgal C, Wilson DF. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005;98:1503. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01140.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wilson DF, Vinogradov SA, Grosul P, Kuroki A, Bennett J. Appl. Opt. 2005;25:5239. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.005239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17)(a).Dashkevich SN, Kaliya OL, Kopranenkov VN, Luk’janets EA. Zh. Prikl. Spectrosk. (Russian) 1987;47:144. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sapunov UV, Soloviev KN, Kopranenkov VN, Dashkevich SN. Teor. Exp. Khim.(Russian) 1991;27:105. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kobayashi N, Nevin WA, Mizunuma S, Awaji H, Yamaguchi M. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993;205:51. [Google Scholar]; (d) Roitman L, Ehrenberg B, Kobayashi N. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 1994;77:23. [Google Scholar]

- (18)(a).Cheng RJ, Chen YR, Wang SL, Cheng CY. Polyhedron. 1993;12:1353. [Google Scholar]; (b) Finikova OS, Cheprakov AV, Carroll PJ, Dalosto S, Vinogradov SA. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:6944. doi: 10.1021/ic0260522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Senge MO. See, for examples. In ref 1a, Chapter 6 and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Haddad RE, Gazeau S, Pecaut J, Marchon JC, Medforth CJ, Shelnutt JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1253. doi: 10.1021/ja0280933. See, for example. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21)(a).Gentemann S, Medforth CJ, Forsyth TP, Nurco DJ, Smith KM, Fajer J, Holten D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:7363–7368. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sazanovich IV, Galievsky VA, van Hoek A, Schaafsma TJ, Malinovskii VL, Holten D, Chirvony VS. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:7818. [Google Scholar]

- (22)(a).Nguyen KA, Pachter R. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;114:10757. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kobayashi N, Konami H. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2001;5:233. [Google Scholar]; (c) Rosa A, Ricciardi G, Baerends EJ, van Gisbergen SJA. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:3311. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wertsching AK, Koch AS, DiMagno SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3932. doi: 10.1021/ja003137y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Renner MW, Cheng R-J, Chang CK, Fajer J. J. Phys. Chem. 1990;94:8508. [Google Scholar]

- (25)(a).Cheng RJ, Chen YR, Chuang CE. Heterocycles. 1992;34:1. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheng RJ, Chen YR, Chen CC. Heterocycles. 1994;38:1465. [Google Scholar]; (c) Cheng R-J, Lin S-H, Mo H-M. Organometallics. 1997;16:2121. [Google Scholar]

- (26)(a).Helberger JH, von Rebay A, Hever DB. Just. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1938;533:197. [Google Scholar]; (b) Helberger JH, Hever DB. Just. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1938;536:173. [Google Scholar]

- (27)(a).Barrett PA, Linstead RP, Rundall FG, Tuey GAP. J. Chem. Soc. 1940;1079 [Google Scholar]; (b) Linstead RP, Weiss FT. J. Chem. Soc. 1950;2975 [Google Scholar]

- (28)(a).Vogler A, Rethwisch B, Kunkely H, Hutterman J, Besenhard JO. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978;17:951. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vogler A, Kunkely H, Rethwisch B. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1980;46:101. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fischer K, Hanack M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1983;22:724. [Google Scholar]

- (29)(a).Kopranenkov VN, Makarova EA, Lukyanets EA. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 1981;51:2727. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kopranenkov VN, Makarova EA, Dashkevich SN, Luk’janets EA. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (Russian) 1988;773 [Google Scholar]; (c) Vorotnikov AM, Kopranenkov VN, Lukyanets EA. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (Russian) 1994;36 [Google Scholar]

- (30)(a).Edwards L, Gouterman M, Rose CB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:7638. doi: 10.1021/ja00440a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kopranenkov VN, Tarkhanova EA, Luk’yanets EA. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 1979;15:570. [Google Scholar]; (c) Koehorst RBM, Kleibeuker JF, Tjeerd JS, de Bie DA, Geursten B, Henrie RN, van der Plas HC. J. Chem. Soc. 1981;1005 [Google Scholar]

- (31)(a).Bender CO, Bonnett R, Smith RG. J. Chem. Soc. 1969;345 doi: 10.1039/p19720000771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bender CO, Bonnett R, Smith RG. J. Chem. Soc. 1970;1251 doi: 10.1039/p19720000771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Bender CO, Bonnett R, Smith RG. J. Chem. Soc. 1972;771 doi: 10.1039/p19720000771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Matsuzawa Y, Ichimura K, Kudo K. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1998;277:151. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kopranenkov VN, Makarova YA, Dashkevich SN, Lukyanets YA. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. (Russian) 1982;1563 [Google Scholar]

- (33).Kopranenkov VN, Vorotnikov AM, Lukyanets EA. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 1979;49:2783. [Google Scholar]

- (34)(a).Kopranenkov VN, Vorotnikov AM, Dashkevich SN, Luk’yanets EA. J. Gen. Chem. (Russian) 1985;803 [Google Scholar]; (b) Rein M, Hanack M. Chem. Ber. 1988;121:1601. [Google Scholar]

- (35)(a).Lash T. Energy Fuels. 1993;7:166. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lash TD, Roper TJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:7715. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lash TD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:2533. [Google Scholar]; (d) Lash TD, Denny CP. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:59. [Google Scholar]; (e) Manley JM, Roper TJ, Lash TD. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:874. doi: 10.1021/jo040269r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ono N, Hironaga H, Ono K, Kaneko S, Murashima T, Ueda T, Tsukamura C, Ogawa T. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin. Trans. 1. 1996;417 [Google Scholar]

- (37).Remy DE. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:1452. Synthesis of Ph4TBP from isoindole has been described, but it also required a condensation at high temperature. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Vicente MGH, Tome AC, Walter A, Cavaleiro JAS. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:3639. [Google Scholar]

- (39)(a).Ito S, Murashima T, Uno H, Ono N. Chem. Commun. 1998;1661 [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito S, Ochi N, Murashima T, Uno H, Ono N. Heterocycles. 2000;52:399. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ito S, Ochi N, Uno H, Murashima T, Ono N. Chem. Commun. 2000;893 [Google Scholar]; (d) Ito S, Uno H, Murashima T, Ono N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:45. [Google Scholar]; (e) Uno H, Ishikawa T, Hoshi T, Ono N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:5163. [Google Scholar]; (f) Murashima T, Tsujimoto S, Yamada T, Miyazawa T, Uno H, Ono N, Sugimoto N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:113. [Google Scholar]

- (40)(a).Finikova O, Cheprakov A, Beletskaya I, Vinogradov S. Chem. Commun. 2001;261 [Google Scholar]; (b) Finikova OS, Cheprakov AV, Beletskaya IP, Carroll PJ, Vinogradov SA. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:522. doi: 10.1021/jo0350054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41)(a).Finikova OS, Cheprakov AV, Carroll PJ, Vinogradov SA. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7517. doi: 10.1021/jo0347819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Finikova OS, Aleshchenkov SE, Brinas RP, Cheprakov AV, Carroll PJ, Vinogradov SA. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:4617. doi: 10.1021/jo047741t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42). The oxidation aromatization approach has been used before to synthesize aromatically π-extended porphyrins (for examples, see ref 35), but it has never been applied to the synthesis of meso-unsubstituted TBPs and TNPs. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sessler JL, Mozaffari A, Johnson MR. In: Organic Synthesis. Freeman JP, editor. Vol. 70. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1998. p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Kobayashi N, Koshiyama M, Osa T. Inorg. Chem. 1985;24:2502. Oxidation states and spin states of FeTBP complexes depend strongly on the nature of their axial ligation. For examples, see. and ref 28a,b. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Rama Rao AV, Yadav JS, Bal Reddy K, Mehendale AR. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:4643. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lash TD, Bellettini JR, Bastian JA, Couch KB. Synthesis. 1994;170 [Google Scholar]

- (47). The common substrates for Barton-Zard reaction are 2-nitroolefines and vinyl sulfones.49 In the case of α-chlorosulfones, such as 9a-c, the elimination of HCl, leading to the corresponding vinyl sulfones, and the subsequent Barton-Zard reaction can be combined in one step.41b.

- 48(a).Savoia D, Trombini C, Umani-Ronci A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1977;123 [Google Scholar]; (b) Inomata K, Hirata T, Kinoshita H, Kotake H, Senda H. Chem. Lett. 1988;2009 [Google Scholar]

- (49)(a).Barton D, Zard S. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985;1098 [Google Scholar]; (b) Barton D, Kervagoret J, Zard S. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:7587. [Google Scholar]; (c) Arnold DP, Burgess-Dean L, Hubbard J, Abdur Rahman M. Aust. J. Chem. 1994;47:969. [Google Scholar]; (d) Abel Y, Haake E, Haake G, Schmidt W, Struve D, Walter A, Montforts FP. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1998;81:1978. [Google Scholar]

- (50)(a).Sevchenko AN, Soloviev KN, Shkirman SF, Kachura TF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USSR (Russian) 1965;161:1313. For example see. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sevchenko AN, Soloviev KN, Gradushko AT, Shkirman SF. Soviet Phys. Proc. (Russian) 1967;11:349. [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsvirko MP, Sapunov VV, Soloviev KN. Opt. Spectrosc. (Russian) Vol. 34. 1973. p. 1094. [Google Scholar]; Kobayashi N. In: Phthalocyanines. Properties and Applications. Leznoff CC, Lever ABP, editors. VCH Publishers; New York: 1993. Also see. and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- (51)(a).Gouterman MJ. Mol. Spectrosc. 1961;6:138. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bajema L, Gouterman M, Rose C. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1971;39:421. [Google Scholar]; (c) Aartsma TJ, Gouterman M, Jochum C, Kwiram AL, Pepich BV, Williams LD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:6278. [Google Scholar]

- (52)(a).Aaviksoo J, Frieberg A, Savikhin S, Stelmakh GF, Tsvirko MP. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1984;111:275. For examples, see. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ehrenberg B, Johnson FM. Spectrochim. Acta. 1990;46a:1521. [Google Scholar]; (c) Luo BZ, Tian MZ, Li WL, Huang SH, Yu JQ. J. Lumin. 1992;53:247. [Google Scholar]; (d) Vacha M, Machida S, Horie K. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995;242:169. [Google Scholar]; (e) Stiel H, Volkmer A, Ruckmann I, Zeug A, Ehrenberg B, Roder B. Opt. Commun. 1998;155:135. [Google Scholar]; (f) Khodykin OV, Zilker SJ, Haarer D, Kharlamov BM. Opt. Lett. 1999;24:513. doi: 10.1364/ol.24.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Zhou X, Ren AM, Feng JK, Liu XJ. Can. J. Chem. 2004;82:19. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Sapunov VV, Solovev KN, Kopranenkov VN, Vorotnikov AM. Zh. Prikl. Spektrosk. 1986;45:56. [Google Scholar]

- (54). Earlier, we have pointed out41b that precise measurements of emission quantum yields in the range of the spectrum around 1 μm are difficult because of the rapidly fading sensitivity of the detection systems (PMTs). Therefore, the reported quantum yield values should be considered as approximate.

- (55).Tietze LF, Eicher T. Reaktionen und Synthesen im organisch-chemischen Praktikum und Forschungslaboratorium. Georg Thieme Verlag; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Novak BH, Lash TD. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3998. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Toyota M, Yokota M, Ihara M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1856. doi: 10.1021/ja0035506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Hopkins PB, Fuchs PL. J. Org. Chem. 1978;43:1208. [Google Scholar]