Abstract

Cord blood T lymphocytes are immature and their functional defect partially reflects a suboptimal level of costimulatory signals provided by neonatal antigen-presenting cells. Neonatal Vδ2 T lymphocytes, a small component of cellular immunity involved in the response against bacteria, protozoa, virus-infected cells and tumours, are also considered to be immature. Cord blood Vδ2 T lymphocytes are mostly naïve, proliferate poorly and do not produce cytokines in response to the model phosphoantigen isopentenyl pyrophosphate. We cultured cord blood mononuclear cells with the aminobisphosphonate Pamidronate or with live bacille Calmette–Guérin, and showed that both elicit a strong cord blood Vδ2 T-cell proliferative response, inducing the expression of activation markers and promoting the differentiation from naïve to memory cells. Our results suggest that cord blood Vδ2 T cells are not inherently unresponsive and can mount strong responses to aminobisphosphonates and mycobacteria. Neonatal Vδ2 T lymphocytes may be important participants in responses to microbial infections early in life.

Keywords: aminobisphosphonates, bacille Calmette–Guérin, cord blood, gammadelta, T lymphocytes

Introduction

The human neonatal immune system is considered to be partially immature or hyporesponsive compared with its adult counterpart. This early immune system seems skewed towards a T helper type 2 (Th2) profile1 and cord blood (CB) T lymphocytes display low proliferation and impaired Th1 cytokine production in response to stimuli.2 Neonatal T cells have a greater requirement than adult T cells for costimulatory signals and neonatal antigen-presenting cells (APC) do not provide sufficient costimulation for T-cell responses.3 However, when adult APC were used to stimulate CB T cells, adult levels of function were achieved.4

Neonatal γδ T-lymphocyte populations are also considered to be immature. In adult peripheral blood, the major γδ population expresses a Vγ2 chain paired with the Vδ2 chain. In CB, a dominant fraction of γδ cells expresses the Vδ1 chain mostly with the Vγ1,5 and the frequency of Vγ2Vδ2+ lymphocytes is low.6 Moreover, γδ T cells in CB expresses an array of γ and δ chain pairs that differ from the γδ pairs found commonly in adults: both Vγ2Vδ1 and Vγ1Vδ2 are unusual among adults, but are found in CB.5 During early childhood the γδ repertoire evolves; the frequency (and number) of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells increases because of positive selection and peripheral expansion.6 Selection and expansion produce a biased adult repertoire dominated by Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in blood.

The Vγ2Vδ2 T lymphocytes are important for the protective response against bacteria, protozoa, virus-infected cells and tumours. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells are stimulated by small non-peptidic compounds collectively named phosphoantigens.7,8 Some of these molecules, including isopentenyl-pyrophosphate (IPP), are precursors of isoprenoid biosynthesis9 and are common to all eukaryotes. Phosphoantigens are supposedly recognized directly by the T-cell receptor10,11 but biophysical studies have not confirmed this hypothesis. Another class of stimulatory compounds, the aminobisphosphonates, also elicits robust Vγ2Vδ2 lymphocyte responses12 but these molecules act indirectly, by blocking isoprenoid biosynthesis and inducing accumulation of IPP.13

Responses to phosphoantigens and other Vγ2Vδ2 T-cell stimulators are major histocompatibility complex (MHC) unrestricted,10,14 but whether other presenting molecules are involved is unknown. Upon activation, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells proliferate rapidly, secrete large amounts of Th1 cytokines (interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α) and acquire strong cytolytic capacity. The memory-effector compartment (CD27– CD45RA–) is mainly responsible for cytokine secretion and cytotoxic activity, while the central-memory compartment (CD27+ CD45RA–) is mainly responsible for proliferative responses.15

A large fraction of peripheral blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells expresses MHC type I-specific inhibitory receptors, including the CD94/NKG2A heterodimer. Triggering of these receptors partially inhibits Vδ2 lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production in response to microbial phosphoantigens, by setting a higher activation threshold.16 Engagement of CD94/NKG2A also down-modulates Vδ2 T-cell cytolytic activity against virus-infected or tumour cells.17 The MHC class I-specific inhibitory receptors may guard against Vδ2 autoreactivity (they recognize ubiquitous host molecules) by sensing the presence of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) -I molecules and hampering accidental Vδ2 lymphocyte activation in response to healthy cells or to low, physiological doses of phosphoantigens.

Cord blood Vδ2 T cells, unlike their adult counterparts, mostly display a naïve phenotype and have poor proliferative18 or cytokine responses19 to IPP stimulation. Our goal was to show whether CB Vδ2 cells are inherently incapable of responding to stimuli or whether their hyporesponsiveness is a reflection of inefficient APC function in cord blood mononuclear cell (CBMC) cultures. We compared CBMC responses to IPP and to the aminobisphosphonate Pamidronate (PAM). Both compounds stimulate adult Vδ2 cells,20 with the important difference that PAM is internalized by myeloid cells13 and Vδ2 cell responses to PAM occur only in the presence of myeloid cells in culture.21 Furthermore, we compared CB responses in specimens from European (Rome, Italy) and West African (Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire) deliveries. African mothers have a high probability of malaria exposure during pregnancy and Plasmodium sp. is known to produce phosphoantigens that stimulate Vδ2 T cells.22,23 By examining the differential responses to IPP and PAM in CB from Rome and Abidjan, we had the opportunity to evaluate the impact of possible fetal exposure to phosphoantigen and show whether this influences Vδ2 T cells directly or alters reactivity by affecting the APC function.

Materials and methods

Lymphocyte sample collection

Umbilical cord blood samples were obtained from uncomplicated full-term vaginal deliveries by venepuncture of the umbilical vein immediately after delivery. Samples were collected at the ‘San Pietro’ Hospital, Fatebenefratelli, in Rome, and at Alepe Hospital, near Abidjan in Côte d'Ivoire. In both sites, women donating CB were human immunodeficiency virus negative. Women enrolled in Rome did not have acute, clinical symptoms of infectious disease during pregnancy, while the infectious disease history was not known for the women enrolled in Alepe. The study was approved by the local ethical committee and informed consent forms were obtained from all women donating cord blood. Heparinized peripheral blood samples were collected from mothers at delivery (‘San Pietro’ Hospital, Fatebenefratelli). The CBMC and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by centrifugation over Ficoll–Hypaque (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient according to the manufacturer's instructions, and used immediately.

Cell culture

Freshly isolated CBMC and PBMC were resuspended at 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 (ICN Biomedical, Inc., Aurora, OH) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; ICN Biomedical, Inc.), 2 mm l-glutamine (ICN Biomedical, Inc.) and 10 IU/ml penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy). To expand Vγ2Vδ2 T lymphocytes, cultures were treated with isopentenyl-pyrophosphate (IPP) (Sigma) at 30 μg/ml, as previously described18 (for a few samples 3 μg/ml was used in parallel), or disodium-3-amino-1-hydroxypropylidene-1,1-bisphosphonic acid (Pamidronate; Novartis Farma, Origgio, Italy) at 10 μg/ml. In some experiments, live bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) Pasteur strain (Aventis-Pasteur, Lyon, France) was used at multiplicities of infection of 0·1, 0·5 and 1 colony-forming units per cell, and the antibiotic gentamycin (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to these cultures instead of penicillin–streptomycin. Human recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2) (50 IU/ml; Proleukin, Chiron, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) was added to all cultures. Medium with IL-2 represented the control treatment. Cells were incubated for 10 days at 37° with 5% CO2 and fresh medium was added on days 4 and 7. After 10 days, cells were harvested and their viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion.

A Stimulation Index (SI) was calculated as: the absolute number of Vδ2 after IPP or PAM stimulation divided by the absolute number of Vδ2 after IL-2 stimulation.

Flow cytometry

Expanded Vδ2 lymphocytes or ex vivo CBMC and PBMC were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; (ICN Biomedical Inc.) with 10% FBS and stained at 4° with directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies. After 20 min, cells were washed twice with PBS/10% FBS and resuspended in PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde. Between 2 × 104 and 5 × 104 lymphocytes (gated on the basis of forward and side scatter profiles) were collected for each sample on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and results were analysed using cellquest software (BD Biosciences). The following monoclonal antibodies, all purchased from BD/Pharmingen (San Jose, CA), were used for four-colour stainings: anti-Vδ2 (clone B6), anti-CD3 (clone SK7), anti-CD25 (clone M-A251), anti-CD69 (clone L78), anti-CD45-RA (clone HI100), anti-CD27 (clone M-T271), anti CD94 (clone HP-3D9).

Statistical analysis

Differences among groups were evaluated using a two-tailed Student's t-test. P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Pamidronate treatment activates and expands CB Vδ2 T cells

Since CB Vδ2 T cells responded poorly to IPP,18 we wanted to evaluate the effectiveness of an aminobisphosphonate, PAM, for triggering Vδ2 T-cell proliferation. We stimulated PBMC from five healthy adult donors with PAM at concentrations ranging from 0·5 to 100 μg/ml, to define a dose–response curve. The most effective concentration for promoting expansion was 10 μg/ml (see Supplementary Figure S1) and we used this dosage for all subsequent experiments.

We measured the CB proliferative responses to IPP and PAM. All results reported were obtained using 30 μg/ml IPP; a lower IPP concentration, 3 μg/ml, was tested for some samples but was less potent (data not shown). The average CB Vδ2 frequency among CD3+ cells was significantly higher after IPP stimulation than after culture with IL-2 alone (P < 0·05), but was significantly lower than after stimulation with PAM (P < 0·05) (Fig. 1a). In fact, the average frequency of CB Vδ2 after PAM stimulation was almost threefold higher than the average after IPP stimulation (14·7% ± 13·6% versus 5·2% ± 5·8%). Thus, although PAM stimulates Vδ2 T cells by inducing the accumulation of IPP in accessory cells, PAM stimulation was significantly more effective than IPP itself for expanding neonatal γδ lymphocytes.

Figure 1.

Cord blood Vδ2 T cells are hyporesponsive to isopentenyl-pyrophosphate (IPP) but they respond better to Pamidronate (PAM). The frequency of Vδ2 among CD3+ cells was determined by flow cytometry ex vivo and after a 10-day culture with control medium [interleukin-2 (IL-2), 50 U/ml], IPP (30 μg/ml + IL-2, 50 U/ml) or PAM (10 μg/ml + IL-2, 50 U/ml) for 11 CB samples (a) and 16 maternal PB samples (b). Individual values as well as mean ± SD are shown for each sample set; *P < 0·05.

Maternal Vδ2 responses to IPP and PAM were similar in magnitude (Fig. 1b). Maternal Vδ2 frequency after IPP expansion was higher on average (P < 0·05) than CB Vδ2 frequency following the same treatment, and maternal stimulation indices to IPP were significantly higher (data not shown). However, considering the ex vivo frequencies of Vδ2 T-cells in CBMC and in PBMC (0·44% ± 0·29% and 2·9% ± 1·6%, respectively, P < 0·05) (Table 1), the increases in CB Vδ2 frequency were comparable to those of peripheral blood Vδ2 T lymphocytes. Maternal Vδ2 frequencies after PAM expansion were not significantly higher than CB Vδ2 frequency following the same treatment and stimulation indices for the mother cells treated with PAM were lower than for CB cells (data not shown).

Table 1.

Ex vivo phenotype for peripheral blood and cord blood mononuclear cells

| Phenotype | PBMC Rome | CBMC Rome | CBMC Abidjan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vδ2+ (% of CD3) | 2·86 ± 1·64 | 0·44 ± 0·29 | 0·47 ± 0·3 |

| CD94+ (% of Vδ2) | 42·7 ± 21·4 | 2·9 ± 2·8 | 8·4 ± 5·2 |

| CD45RA– (% of Vδ2) | 91·7 ± 8·1 | 29·1 ± 12·4 | 24·1 ± 14·9 |

| CD27– CD45RA–(% of Vδ2) | 44·9 ± 37·0 | 3·5 ± 2·3 | 7·8 ± 7·8 |

| CD27+ CD45RA–(% of Vδ2) | 46·8 ± 32·1 | 25·9 ± 15·6 | 16·3 ± 12·2 |

The frequency of Vδ2 T cells among CD3+ lymphocytes, and the proportion of Vδ2+ cells displaying each phenotype are shown for every group as mean ± SD.

CBMC, cord blood mononuclear cells; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Cord blood Vδ2 expansion was associated with up-regulation of the activation markers CD25 and CD69 (Fig. 2). CD25 was present on a small proportion of CB Vδ2 ex vivo (10·7% ± 7·2%). Both IPP stimulation and PAM stimulation increased significantly the fraction of CD25+ Vδ2 lymphocytes (P < 0·05), while culture with IL-2 alone did not have an effect (Fig. 2a). Less than 5% of CB Vδ2 displayed CD69 on the cell surface, but IL-2 was sufficient to increase the CD69+ fraction to 40%. After IPP or PAM stimulation the proportion of CD69+ cells (72·8% ± 8·4% and 64·8% ± 16%, respectively) was significantly higher (P < 0·001) than for control cultures (IL-2 only) (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Cord blood Vδ2 T-cell stimulation induces up-regulation of activation markers and natural killer receptors. The proportion of Vδ2 T lymphocytes expressing CD25, CD69 (a) and CD94 (b) was determined ex vivo and after a 10-day culture for nine (a) and 11 (b) cord blood samples, respectively. Mean + SD are represented for each sample set; *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001. IPP, isopentenyl-pyrophosphate; PAM, pamidronate.

The CD94/NKG2A dimer is present on most Vδ2 cells in peripheral blood but not on ex vivo CB Vδ2 lymphocytes.24 We monitored the presence of this marker (or NKG2A in another set of experiments, data not shown) on CB fresh cells and after 10 days in culture (Fig. 2b). CD94 was present on 2·9% ± 2·8% of ex vivo Vδ2 cells (Table 1). Control treatment (IL-2 only) or IPP stimulation induced a modest but significant increase of the CD94+ Vδ2 fraction compared to the fresh cells (to 7·8% ± 7·9% and 10·0% ± 8·5%, respectively). After culture with PAM, CD94 was present on a larger proportion of CB Vδ2 cells compared to after IPP stimulation (16·6% ± 7·3%, P < 0·05) (Fig. 2b).

Cord blood samples collected in Côte d'Ivoire respond to PAM better than CB collected in Rome

We collected CB samples in a rural area near Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire) and compared them to the samples collected in Rome. The CB Vδ2 lymphocytes from Abidjan, like those from Rome, responded better to PAM than to IPP (P < 0·001) (Fig. 3a). The CB Vδ2 T-cell frequency in fresh cells was similar between the two groups (Table 1) and was not significantly different after IPP treatment. However, the Vδ2 lymphocyte frequency following PAM stimulation was significantly higher for Côte d'Ivoire samples than for those collected in Rome (47·1% ± 12·2% versus 14·7% ± 13·6%, respectively, P < 0·001) (Fig. 3a). Similarly, PAM stimulation indices were significantly higher for samples collected in Côte d'Ivoire, while IPP stimulation indices were low in both groups (Fig. 3b), indicating that differences in the Vδ2 population (either frequency of reactive cells or maturation state) were not likely to account for the differential reactivity to PAM.

Figure 3.

Cord blood (CB) samples collected in Abidjan respond to pamidronate (PAM) better than CB samples collected in Rome. (a) Vδ2 frequency among CD3+ cells was determined ex vivo and after a 10-day culture for 13 CB samples collected in Abidjan and compared to the Vδ2 frequencies for the CB collected in Rome. Individual values as well as mean ± SD are shown for each sample set. (b) The stimulation index was calculated for each CB sample as follows: (Vδ2 frequency among lymphocytes × absolute number of viable cells in the presence of stimulus)/(Vδ2 frequency among lymphocytes × absolute number of viable cells in the presence of control medium). Mean + SD are represented for each sample set; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001. IPP, isopentenyl-pyrophosphate.

CD94 was present on a small proportion of fresh Vδ2 cells, although the fraction of Vδ2 CD94+ was significantly higher for CB samples collected in Abidjan than for those collected in Rome (P < 0·01) (Table 1). IPP induced a modest, but not significant increase in the fraction of CD94+ Vδ2 cells compared to the ex vivo Vδ2. PAM stimulation caused a significant increase in CD94 expression on Vδ2 lymphocytes compared to fresh cells or after culture with IL-2 alone (P < 0·01) (Fig. 4a). Comparing CD94 expression in stimulated CB collected in Rome or in Abidjan, we showed that the receptor expression pattern was identical in the two sample sets for all conditions and no significant differences were observed for the proportion of CD94+ Vδ2 cells after control, IPP or PAM treatment.

Figure 4.

Cord blood (CB) Vδ2 T-cell stimulation is associated with CD94 up-regulation and differentiation into effector-memory cells. The proportion of CD94+ (a) and of CD45RA– (b) Vδ2 cells was determined ex vivo and after a 10-day culture for 13 CB samples collected in Abidjan. Mean + SD are represented for each sample set; *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01. IPP, isopentenyl-pyrophosphate; PAM, pamidronate.

Importantly, CB Vδ2 lymphocyte expansion was associated with phenotypic differentiation of initially naïve cells into effector-memory and central-memory cells. Overall, the proportion of CD45RA– Vδ2 cells was higher after culture, and IL-2 alone was sufficient to increase it from 24·1% to 38·2% (P < 0·01). After PAM stimulation the fraction of memory cells was significantly larger than with IL-2 alone (93·9% versus 38.2%, P < 0·01), while IPP induced only a modest increase in the CD45RA– fraction compared with control treatment (IL-2 only). The proportion of CD27– CD45RA– Vδ2 cells increased after both IPP and PAM stimulation, but was only significantly higher (P < 0·001) after PAM stimulation (Fig. 4b). The fraction of CD27+ CD45RA– (central memory) Vδ2 was the same after control treatment (IL-2 only) or IPP stimulation, but was significantly higher after PAM stimulation (P < 0·01).

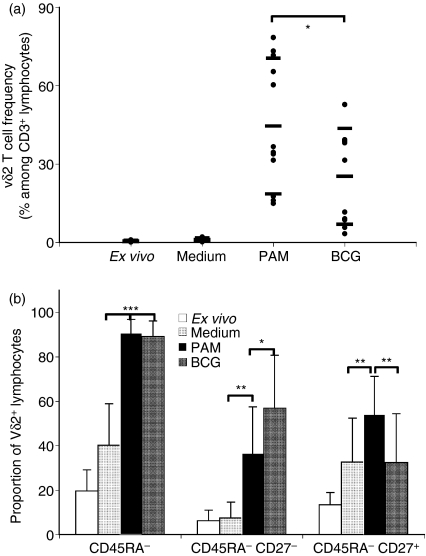

CB Vδ2 T lymphocytes respond to live BCG by proliferating and differentiating into effector-memory cells

Peripheral blood Vδ2 T cells are involved in the response to infectious agents, including mycobacteria. Since neonates in the Côte d'Ivoire are vaccinated routinely with BCG during the first week of life, we wanted to know whether CB Vδ2 lymphocytes respond to live BCG in a cell culture system and hence could be involved in the neonatal response to BCG. We used the same BCG preparation that is inoculated as vaccine, initially testing three multiplicities of infection (0·1 : 1, 0·5 : 1 and 1 : 1 colony-forming unit : CBMC ratios). BCG at the most effective multiplicity of infection, 0·5, induced expansion of the CB Vδ2 subset, whose frequency among CD3+ cells increased from the initial 0·47 ± 0·3% to 25·21 ± 18·35% (P < 0·001) after 10 days in culture (Fig. 5a). Pamidronate was more effective than BCG for triggering proliferation (P < 0·02); they were similarly effective for inducing differentiation of Vδ2 lymphocytes into CD45RA– memory cells (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, the proportion of effector-memory (CD27– CD45RA–) Vδ2 T cells was significantly higher after BCG than after PAM stimulation (36·6% ± 20·9% versus 56·8% ± 24%, P < 0·05) while the proportion of central memory (CD27+ CD45RA–) Vδ2 T cells was higher after PAM stimulation (54·1% ± 17·1% versus 32·4% ± 22%, P < 0·01). The fraction of CD94+ Vδ2 lymphocytes was larger after culture with BCG than after culture with PAM, but the difference was not statistically significant (data not shown). Consistent with the increase of CD27– CD45RA– Vδ2 T cells, preliminary flow cytometry studies showed that CB Vδ2 lymphocytes expanded with PAM or BCG then rested for a week, were able to secrete interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α upon restimulation (data not shown). However, further work is needed to confirm this observation.

Figure 5.

Cord blood (CB) Vδ2 T-cells respond to live bacilli Calmette–Guérin (BCG) stimulation by proliferating and differentiating into effector-memory cells. Vδ2 T-cell frequency among CD3+ cells (a) and the proportion of CD45RA– (b) Vδ2 lymphocytes were monitored ex vivo and after a 10-day culture for 10 CB samples collected in Abidjan. Individual values as well as mean ± SD are shown for Vδ2 frequency for each sample set (a), and mean + SD are represented for CD45RA– proportion (b). *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001. PAM, pamidronate.

Discussion

In this study, we show that CB Vδ2 T lymphocytes, although hyporesponsive to the model phosphoantigen IPP, were capable of proliferative responses to PAM or BCG. Pamidronate induced a more robust Vδ2 T-cell proliferation in CB samples collected in Abidjan compared to samples from Rome, but responses to IPP were poor for both groups.

Most Vδ2 T lymphocytes in CB are naïve. Adult Vδ2 T cells with naïve phenotype proliferate after IPP stimulation.25 There are clear and unexplained differences in the response to IPP by adult or CB Vδ2 T-cell subsets that both express a ‘naïve’ phenotype. This observation argues against the naïve state of CB Vδ2 being responsible for the low proliferation to IPP.

The IPP is recognized directly by Vδ2 T cells without requiring uptake and processing by APC,10 while aminobisphosphonates must be internalized by accessory cells (monocytes, in PBMC cultures).13,21 Live BCG infects monocyte/macrophages and dendritic cells, causing cell activation, cytokine production and up-regulation of surface molecules.26–29Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected monocytes efficiently stimulate Vδ2 lymphocytes30 and maximal stimulation by live M. tuberculosis requires APC.31,32

The stronger responses to PAM or BCG may be related to pathways for antigen presentation in CB myeloid cells. If a presenting molecule is involved in phosphoantigen recognition, aminobisphosphonates and BCG but not IPP, may induce APC to modulate presenting molecules and give a stronger Vδ2 lymphocyte stimulation. It is also possible that CB Vδ2 lymphocytes, like CB αβ T cells, need higher costimulation (mediated either by cytokine/receptor interaction or by cognate receptor interactions) than neonatal APC can provide. The BCG activated APC/accessory cells may up-regulate surface molecules or release cytokines needed for optimal Vδ2 T-cell activation. The same may occur with PAM. Previous studies reported that 10 μm Zoledronate (another aminobisphosphonate, approximatively 100-fold more potent than PAM) has an overall inhibitory effect on adult myeloid cells, particularly macrophages,33 but a lower concentration enhances dendritic cell ability to stimulate innate and adaptive immunity.34 In our studies, the use of 25 μm PAM is optimal for Vδ2 cell responses, and probably represents a compromise between myeloid cell toxicity and APC activation in these CB mononuclear cell cultures.

There are reports of transplacental priming in the fetal immune system after maternal exposure to microbial35,36 and environmental1 antigens, and it is known that neonatal T-lymphocyte and B-lymphocyte reactivity is influenced by intrauterine exposure to microbial antigens.37,38 Phosphoantigens that stimulate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells are small molecules that are likely to cross the placental barrier. We wondered whether maternal exposure to pathogens that produce phosphoantigens might alter neonatal Vδ2 T cells and increase their in vitro reactivity to stimuli. Cells in the CB collected in Abidjan were more reactive to PAM than those collected in Rome, but responses to IPP were the same for both CB groups. Our results suggest that the disparity in PAM responsiveness was not dictated by the Vδ2 lymphocytes but was probably the result of differences in the population of APC/accessory cells. If Vδ2 T cells in the CB from Abidjan were inherently more reactive, they should have responded well to both compounds. Our observation might be explained by hypothesizing that transplacental priming via microbial antigens (which is likely to happen in women from rural areas of the Côte d'Ivoire, but not in women from Rome) activated fetal APC/accessory cells in utero and up-regulated molecule(s) and/or cytokines necessary for optimal Vδ2 stimulation. However, more focused studies are necessary to evaluate the potential impact of individual infectious diseases during pregnancy on neonatal Vδ2 reactivity and repertoire, and to define APC phenotypic/functional differences.

Proliferation of CB Vδ2 T cells was accompanied by several phenotypic modifications. Proliferation led to higher expression of CD25 or CD69 on Vδ2 cells, and the same was true for CD94 expression. However, we did not find a correlation between the final frequency of Vδ2 lymphocytes among CD3+ cells and expression levels for any of these molecules. In particular, proliferation did not seem sufficient or necessary for CD94 up-regulation, because some CB samples with high post-expansion Vδ2 cell frequencies had low proportions of CD94+ cells. We also noted that samples with low post-expansion Vδ2 frequencies had larger proportions of CD94+ cells. It was shown that Vδ2 lymphocytes in adult peripheral blood have CD94 either on the membrane or stored intracellularly, and CD94 is translocated from the cytoplasm to the surface upon stimulation. However, most Vδ2 clones of thymic origin (derived from naïve cells) were CD94–, did not have intracellular CD94 and its expression could not be induced by stimulation.39 Most CB Vδ2, like clones of thymic origin, also remained CD94– after stimulation.

Among adult Vδ2 T cells, the CD94– fraction had higher proliferative responses to phosphoantigens compared to the entire Vδ2 population,39 indicating that CD94 engagement could partially inhibit proliferation. The absence of CD94 may allow CB Vδ2 lymphocytes, when properly stimulated, to proliferate more than their adult counterparts. Proliferative responses to PAM (considering either stimulation indices or fold increase of Vδ2 T-cell frequency after culture) were higher in CB compared to maternal cells for specimens from Rome.

The study of neonatal γδ T cells provides an important model for understanding the development of cellular immunity. Our work revealed important differences in phosphoantigen responses between study groups in Europe and Africa. Future efforts will define the mechanisms responsible for those differences and help to understand the impact of maternal infectious disease on early child health and responses to paediatric vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We thank the ‘San Pietro’ Hospital Transfusional Centre, Laura De Leo and Dr Lucia Maule for their invaluable assistance with cord blood collection, Dr Carla Montesano and Dr Roberta Placido for advice, and Dr Luca Battistini for helpful suggestions and comments. We are especially grateful to Dr Henri Chenal, at the Centre de Recherches Bioclinique d'Abidjan for facilitating the research efforts of Dr Cappelli and Dr Cairo in Côte d'Ivoire. This work was supported by the Unesco Program ‘Families First Africa’.

Supplementary material

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

Dose-dependent response of peripheral blood Vδ2+ T cells to pamidronate stimulation.

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Prescott SL, Macaubas C, Holt BJ, Smallacombe TB, Loh R, Sly PD, Holt PG. Transplacental priming of the human immune system to environmental allergens: universal skewing of initial T cell responses toward the Th2 cytokine profile. J Immunol. 1998;160:4730–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris DT, Schumacher MJ, Locascio J, et al. Phenotypic and functional immaturity of human umbilical cord blood T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10006–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adkins B. T-cell function in newborn mice and humans. Immunol Today. 1999;20:330–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romani N, Reider D, Heuer M, Ebner S, Kampgen E, Eibl B, Niederwieser D, Schuler G. Generation of mature dendritic cells from human blood. An improved method with special regard to clinical applicability. J Immunol Methods. 1996;196:137–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morita CT, Parker CM, Brenner MB, Band H. TCR usage and functional capabilities of human gamma delta T cells at birth. J Immunol. 1994;153:3979–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker CM, Groh V, Band H, et al. Evidence for extrathymic changes in the T cell receptor gamma/delta repertoire. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1597–612. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka Y, Sano S, Nieves E, et al. Nonpeptide ligands for human gamma delta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8175–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka Y, Morita CT, Nieves E, Brenner MB, Bloom BR. Natural and synthetic nonpeptide antigens recognized by human gamma-delta T-cells. Nature. 1995;375:155–8. doi: 10.1038/375155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberl M, Hintz M, Reichenberg A, Kollas AK, Wiesner J, Jomaa H. Microbial isoprenoid biosynthesis and human gammadelta T cell activation. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:4–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita CT, Beckman EM, Bukowski JF, Tanaka Y, Band H, Bloom BR, Golan DE, Brenner MB. Direct presentation of nonpeptide prenyl pyrophosphate antigens to human gamma delta T cells. Immunity. 1995;3:495–507. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Band H, Brenner MB. Crucial role of TCR gamma chain junctional region in prenyl pyrophosphate antigen recognition by gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:286–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunzmann V, Bauer E, Wilhelm M. Gamma/delta T-cell stimulation by pamidronate. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:737–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gober HJ, Kistowska M, Angman L, Jeno P, Mori L, De Libero G. Human T cell receptor gammadelta cells recognize endogenous mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:163–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schild H, Mavaddat N, Litzenberger C, et al. The nature of major histocompatibility complex recognition by gamma delta T cells. Cell. 1994;76:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gioia C, Agrati C, Casetti R, et al. Lack of CD27– CD45RA– V gamma 9V delta 2+ T cell effectors in immunocompromised hosts and during active pulmonary tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2002;168:1484–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carena I, Shamshiev A, Donda A, Colonna M, Libero GD. Major histocompatibility complex class I molecules modulate activation threshold and early signaling of T cell antigen receptor-gamma/delta stimulated by nonpeptidic ligands. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1769–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poccia F, Cipriani B, Vendetti S, et al. CD94/NKG2 inhibitory receptor complex modulates both anti-viral and anti-tumoral responses of polyclonal phosphoantigen-reactive V gamma 9 V delta 2 T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:6009–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montesano C, Gioia C, Martini F, Agrati C, Cairo C, Pucillo LP, Colizzi V, Poccia F. Antiviral activity and anergy of gammadelta T lymphocytes in cord blood and immuno-compromised host. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2001;15:257–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engelmann I, Moeller U, Santamaria A, Kremsner PG, Luty AJ. Differing activation status and immune effector molecule expression profiles of neonatal and maternal lymphocytes in an African population. Immunology. 2006;119:515–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunzmann V, Bauer E, Feurle J, Weissinger F, Tony HP, Wilhelm M. Stimulation of gammadelta T cells by aminobisphosphonates and induction of antiplasma cell activity in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000;96:384–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyagawa F, Tanaka Y, Yamashita S, Minato N. Essential requirement of antigen presentation by monocyte lineage cells for the activation of primary human gamma delta T cells by aminobisphosphonate antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:5508–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behr C, Dubois P. Preferential expansion of V gamma 9 V delta 2 T cells following stimulation of peripheral blood lymphocytes with extracts of Plasmodium falciparum. Int Immunol. 1992;4:361–6. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behr C, Poupot R, Peyrat MA, Poquet Y, Constant P, Dubois P, Bonneville M, Fournie JJ. Plasmodium falciparum stimuli for human gammadelta T cells are related to phosphorylated antigens of mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2892–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2892-2896.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubio G, Aramburu J, Ontanon J, Lopez-Botet M, Aparicio P. A novel functional cell surface dimer (kp43) serves as accessory molecule for the activation of a subset of human gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:1312–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, Ferlazzo V, et al. Differential requirements for antigen or homeostatic cytokines for proliferation and differentiation of human Vgamma9 Vdelta2 naive, memory and effector T cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1764–72. doi: 10.1002/eji.200525983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KD, Lee HG, Kim JK, et al. Enhanced antigen-presenting activity and tumour necrosis factor-alpha-independent activation of dendritic cells following treatment with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin. Immunology. 1999;97:626–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu E, Law HK, Lau YL. BCG promotes cord blood monocyte-derived dendritic cell maturation with nuclear Rel-B up-regulation and cytosolic I kappa B alpha and beta degradation. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:105–12. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000069703.58586.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurnher M, Ramoner R, Gastl G, Radmayr C, Bock G, Herold M, Klocker H, Bartsch G. Bacillus Calmette–Guérin mycobacteria stimulate human blood dendritic cells. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:128–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970106)70:1<128::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Wakeham J, Harkness R, Xing Z. Macrophages are a significant source of type 1 cytokines during mycobacterial infection. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1023–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boom WH, Chervenak KA, Mincek MA, Ellner JJ. Role of the mononuclear phagocyte as an antigen-presenting cell for human gamma delta T cells activated by live Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3480–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.9.3480-3488.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balaji KN, Boom WH. Processing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli by human monocytes for CD4+ alphabeta and gammadelta T cells: role of particulate antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:98–106. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.98-106.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rojas RE, Torres M, Fournie JJ, Harding CV, Boom WH. Phosphoantigen presentation by macrophages to Mycobacterium tuberculosis– reactive Vgamma9Vdelta2 + T cells: modulation by chloroquine. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4019–27. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4019-4027.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolf AM, Rumpold H, Tilg H, Gastl G, Gunsilius E, Wolf D. The effect of zoledronic acid on the function and differentiation of myeloid cells. Haematologica. 2006;91:1165–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiore F, Castella B, Nuschak B, et al. Enhanced ability of dendritic cells to stimulate innate and adaptive immunity on short-term incubation with zoledronic acid. Blood. 2007;110:921–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Camus D, Carlier Y, Bina JC, Borojevic R, Prata A, Capron A. Sensitization to Schistosoma mansoni antigen in uninfected children born to infected mothers. J Infect Dis. 1976;134:405–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/134.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gill TJ, III, Repetti CF, Metlay LA, Rabin BS, Taylor FH, Thompson DS, Cortese AL. Transplacental immunization of the human fetus to tetanus by immunization of the mother. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:987–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI111071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dent A, Malhotra I, Mungai P, Muchiri E, Crabb BS, Kazura JW, King CL. Prenatal malaria immune experience affects acquisition of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 invasion inhibitory antibodies during infancy. J Immunol. 2006;177:7139–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malhotra I, Mungai P, Wamachi A, Kioko J, Ouma JH, Kazura JW, King CL. Helminth- and Bacillus Calmette–Guérin-induced immunity in children sensitized in utero to filariasis and schistosomiasis. J Immunol. 1999;162:6843–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boullier S, Poquet Y, Halary F, Bonneville M, Fournie JJ, Gougeon ML. Phosphoantigen activation induces surface translocation of intracellular CD94/NKG2A class I receptor on CD94– peripheral Vgamma9 Vdelta2 T cells but not on CD94– thymic or mature gammadelta T cell clones. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3399–410. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3399::AID-IMMU3399>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dose-dependent response of peripheral blood Vδ2+ T cells to pamidronate stimulation.