Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection induces profound differentiation of T cells, and is associated with impaired responses to other immune challenges. We therefore considered whether CMV infection and the consequent T-cell differentiation in Gambian infants was associated with impaired specific responses to measles vaccination or polyclonal responses to the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB). While the concentration of undifferentiated (CD27+ CD28+ CCR7+) T-cells in peripheral blood was unaffected by CMV, there was a large increase in differentiated (CD28− CD57+) CD8 T-cells and a smaller increase in differentiated CD4 cells. One week post-vaccination, the CD4 cell interferon-γ (IFN-γ) response to measles was lower among CMV-infected infants, but there were no other differences between the cytokine responses, or between the cytokine or proliferative responses 4 months post-vaccination. However, the CD8 T cells of CMV-infected infants proliferated more in response to SEB and the antibody response to measles correlated with the IFN-γ response to CMV, indicating that CMV infection actually enhances some immune responses in infancy.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, infant, measles, SEB, T cell

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is endemic throughout the world, and usually establishes a persistent infection that rarely causes clinical disease.1 Chronic infection of senior citizens is associated with a large expansion of the differentiated CD28− CD57+ subpopulation of CD8 T-cells and a smaller expansion of the equivalent subpopulation of CD4 T-cells.2–7 The expansion of differentiated, and possibly immunosenescent, CD8 T-cells contributes to an ‘immune risk phenotype’,8 which may also include an inversion of the ratio of CD4 and CD8 T-cells in extreme cases.3,5 Both the immune risk phenotype 9,10 and CMV infection 11 are associated with poor responses to the influenza vaccine and to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV),12 another persistent herpesvirus.

The large expansions of differentiated CD8 T cells induced by CMV infection have been found in infants younger than 6 months of age,13 although impairment of immune responses to influenza vaccine increases with age,11,12 showing that the mere presence of the differentiated subpopulations is not the only factor involved in the impairment. The complexity of the interactions between CMV and the immune system was further illustrated by a recent study that associated chronic murine CMV infection with enhanced peritoneal macrophage activity and protection from bacterial infection,14 leading the authors to conclude that CMV may have been functioning more as a symbiote than a pathogen.

The prevalence of CMV is typically higher in low-income countries than in the high-income countries where most research has been carried out,1 and the majority of infants in The Gambia are infected within the first year of life.13 Several studies have shown much higher levels of differentiation in the T cells of sub-Saharan African infants 15,16 than in their peers in Europe and North America,16–18 which is likely to be at least partly caused by the ubiquity of CMV infection.

Despite the ambiguity in the effect of CMV on immune responses, the similarity between the CD8 T-cell subpopulations of CMV-infected infants in sub-Saharan Africa and European and American senior citizens at risk of vaccine failure 3,10 is a matter of concern as the infants are usually infected with CMV while they are still receiving childhood immunizations. For instance, the measles vaccine is administered at 9 months of age, by which time most infants are infected with CMV.13 In spite of the availability of the vaccine, measles outbreaks frequently occur throughout the region and cause considerable morbidity and mortality among infants.19 However, while vaccine efficacy is typically over 90% in Europe and North America,20–22 it is usually reported at below 70% in West Africa,23–25 where human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence is low and severe malnutrition has not been reported as a contributing factor.

Both the wild type and the vaccine strains of measles virus induce antibody 26 and cellular immune responses involving the CD4 and CD8 T-cell populations.27 The relative importance of the cellular and humoral components of the response remains unclear, but depletion of CD8 T cells enhanced pathology considerably more than depletion of B cells in rhesus monkeys,28 demonstrating the importance of cell-mediated immunity.

We explored the possibility that infection with CMV and its effects on the CD8 T-cell population may affect either the capacity of the T cells of Gambian infants to respond to a polyclonal stimulus or the ability of the infants to mount an immune response to a specific challenge in the form of the measles vaccine. As it was not possible to perform a true test of vaccine efficacy by monitoring a attack rates during a measles outbreak, we assessed the effect of CMV infection on the ability of infants to mount cellular and antibody-mediated immune responses to the vaccine.

Subjects and methods

Subjects and sampling

A cohort of 132 subjects was recruited at birth from the maternity ward of Sukuta Health Centre, and informed consent, obtained from the mothers and documented by signature or thumb print, was confirmed when the measles vaccine was administered at 9 months of age. Recruitment was restricted to healthy singletons, defined by a birth weight of at least 2·0 kg without complications during pregnancy or congenital abnormalities.

The catchment area of Sukuta Health Centre is peri-urban, and is characterized by low income and crowded living conditions. The HIV status of study subjects was unknown, but adult prevalence in the region was below 2·5% at the time of the study (National AIDS Control Program, unpublished data) so was unlikely to be a significant confounder.

The study was approved by the MRC-Gambian Government Ethics Committee.

Vaccination and sampling

All infants received the vaccinations specified by the Gambian expanded programme of immunization, which included diphtheria, tetanus and adsorbed pertussis vaccine (Serum Institute of India, Pune, India), and ActHIB vaccine for Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) (Sanofi Pasteur) at 2, 3, 4 and 16 months of age. At 9 months of age, all infants were vaccinated with the Edmonston-Zagreb strain of measles virus (Serum Institute of India). A peripheral blood sample was collected into heparin (Sigma, Natick, MA) a week after vaccination, and the yellow fever and fourth polio booster, which are usually administered simultaneously with the measles vaccine, were delayed until the sample was collected. A second sample was collected into heparin at 13 months of age. Infants were assigned to treatment groups according to their CMV status at the time of each sample.

From each blood sample, the lymphocyte concentration was assessed using a Medonic CA620 haematology analyser (Boule Medical AB, Stockholm, Sweden), and the differential counts were validated by manual readings made by experienced haematologists. The Medonic returned differential counts for 149 of the 252 samples collected (59%), and manual counts were regarded as definitive for the remainder. Where both readings were available, they were validated against each other to confirm that the manual reads returned comparable results to the Medonic. Whole blood was phenotyped as explained below.

Plasma was collected, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were collected by separating on a lymphoprep (Axis-Shield POC AS, Oslo, Norway) column. The PBMC collected at 9 months were used for overnight enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) and intracytoplasmic cytokine staining. Samples collected at 13 months were used for overnight and cultured ELISpot, and proliferation assays.

At 18 months of age, a blood sample was collected into a serum separation microtainer (BD) for the measurement of antibody responses.

Diagnosis of CMV infection

Urine samples were collected within 2 weeks of birth, then monthly until 13 months of age. Every urine sample was tested for the presence of CMV DNA by a nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method.29,30 If a single positive sample followed by a negative sample had been detected by the time of blood sampling, or if the first urine sample collected after the blood sample was the first to test positive, plasma collected at the time of sampling was tested for anti-CMV immunoglobulin G (IgG) using the ELICYTOK-G and IgM using the ELICYTOK-M Reverse Plus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Diasorin, Saluggia, Italy).

If IgM was detected or the concentration of IgG in the sample exceeded that in umbilical cord blood, the infant was diagnosed as infected at the time of sampling. If the plasma did not have detectable levels of IgG or IgM, the infant was considered uninfected. If IgM was not detected and IgG was detected at a lower level than in the umbilical cord blood, the CMV status of the infant could not be established.

The serum collected at 18 months was tested for the presence of anti-CMV IgG and IgM in infants that had not yet been diagnosed with CMV.

Phenotyping

All flow cytometry reagents were obtained from BD (Le Pont-de-Claix, France). All samples were stained with PerCP-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody. The populations were further characterised with fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD28, anti-CD57 and anti-CD45RA, antigen-presenting cell (APC)-conjugated anti-CD27 and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-CCR7 antibodies. Red blood cells were lysed with FACSlyse solution. Samples were acquired using a FACSCalibur fitted with two lasers and analysed using FCS Express (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA).

Virus culture

All culture media were obtained from Sigma. Two strains of measles virus were cultured, the wild-type Edmonston strain (Ed-MV) and the EZ vaccine strain (EZ-MV), which was cultured from a vaccine vial. Two strains of vaccinia were cultured, the T7 wild-type strain (T7-VV) and a variant modified to express the pp65 protein of CMV (pp65-VV). The measles viruses were cultured in Vero cells, and the vaccinia viruses in baby hamster kidney cells. All viruses were cultured in a solution of 90% v/v R+ (RPMI containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) with 100 μg/ml 2 mm l-glutamine and 250 μg/ml amphotericin B, and 10% v/v human AB serum.

The harvested viruses were quantified as plaque forming units (PFU) by cytolytic plaque assay.

Inoculation and culture of PBMC

The technique for short-term stimulation with measles virus was modified from Jaye and colleagues.27 The PBMCs were suspended in R10F [R+ containing 2 mm l-glutamine and 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS)] and infected with Ed-MV at 0·1 plaque-forming units (p.f.u.)/cell in polypropylene 15 ml centrifuge tubes (BD). A negative control sample of equal size was treated with an equivalent volume of uninfected Vero cell supernatant. Both tubes were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 hr, then free virus was washed off by resuspending in 10 ml R+, centrifuging at 450 g for 5 min and discarding the supernatant. The PBMC were resuspended at 106/ml in R10AB (R+ containing 10% v/v human serum from blood type AB and 2 mm l-glutamine).

Short-term stimulation with pp65-VV and T7-VV was carried out by resuspending PBMCs at 106/ml in R10F and inoculating with either pp65-VV or T7-VV at a ratio of 2·0 p.f.u./cell.

Before long-term stimulation with measles, PBMC were suspended at 2 × 106/ml in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and labelled with 250 nm carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C for 7 min. Staining was quenched with FBS and the CFSE was washed off by adding 5–10 ml R10F and centrifuging at 600 g for 5 min. The PBMC were then washed twice by resuspension in 1 ml FBS followed by 14 ml R10F. An aliquot of 10% of the PBMC was then put aside in polypropylene 15 ml centrifuge tubes for viral infection, and the remaining cells were washed again by resuspension in 10 ml PBS and centrifugation to remove FBS, and resuspended at 2 × 106 cells/ml in 10% R10AB. Aliquots of 1–2 ml were placed in the wells of a polystyrene 48-well culture plate (BD) for maintenance.

The PBMC set aside for infection were inoculated with either Ed-MV or EZ-MV at a ratio of 1·0 p.f.u./cell, and negative control cultures were prepared with an equivalent volume of uninfected Vero cell supernatant, and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 18 hr. Cell-free virus was washed off by adding 10 ml R+ and centrifuging at 600 g for 5 min. The PBMCs were resuspended in R10AB, placed in a polystyrene petri-dish (Sterilin, Maidenhead, UK) and exposed to 302 nm UV light using a transilluminator (UVP). The infected PBMC were then added to the cultures that had already been prepared to make up a final ratio of 10% infected to 90% uninfected PBMC. For the proliferation assay, generic replicative capacity was assessed by adding the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) (Sigma) at 2 μg/ml.

Proliferation was assessed after 6 day of culture, but it was necessary to culture the cells for 13 days in order to expand the memory populations sufficiently to carry out an ELISpot. On the 8th day of culture, half the volume of R10AB was removed and replaced with fresh R10AB containing interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Chiron) at a final concentration of 10 U/ml.

Intracytoplasmic cytokine staining (ICS)

Preparations of PBMC inoculated with Ed-MV or pp65-VV for short-term stimulation as described above, or their respective negative controls, were placed in polystyrene 5 ml tubes (BD). A further aliquot was stimulated with 2 μg/ml SEB. Brefeldin A (Sigma) was added at 10 μg/ml to inhibit protein transport and the PBMC were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 12 hr. The cells were then permeabilized with FACSperm II (BD), stained with FITC-conjugated anti-interferon-γ (IFN-γ), PE-conjugated anti-CD4, PerCP-conjugated anti-CD8 and APC-conjugated anti-IL-2 antibodies, and acquired and analysed in the same way as the phenotype samples. Responses were calculated as the difference between the percentage of cells exhibiting a given response in the negative control sample and the percentage of cells exhibiting the same response in the treatment sample.

ELISpot

The ELISpot assay for IFN-γ was carried out on 96-well microplates with hydrophobic polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) based wells (Millipore). For overnight ELISpots, PBMC inoculated with Ed-MV or pp65-VV and their negative controls, prepared as described above, were inoculated into duplicate wells at 100 μl per well. Other PBMC were resuspended at 106 cells/ml in R10F, 100 μl aliquots were added to duplicate wells and stimulated with 100 μl suspensions of R10F containing 10 μg/ml human dermal fibroblast cells infected with CMV and osmotically lysed 31 (Virusys) with an equivalent concentration of normal human dermal fibroblast lysate (NHDF) as a negative control (Virusys), or 20 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma) as a positive control. The plate was incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 18 hr and IFNγ-producing cells were quantified using monoclonal antibodies (Mabtech, Stockholm, Sweden) that used an alkaline phosphatase detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Following long-term stimulation, viable cells were counted using trypan blue (Sigma), and the R10AB was washed off by suspension in R+ followed by centrifugation at 450 g for 5 min. The PBMC were resuspended in 200 μl R10F and reinfected with the virus strain that was used for the initial infection at 0·1 p.f.u./cell. The cells that had been inoculated with Vero cell supernatant were split and inoculated with either Ed-MV or EZ-MV as negative controls. Following incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 hr, cell free virus was washed off by resuspension in R+ and centrifugation at 450 g for 5 min, the cells were resuspended at 106/ml in R10AB. Aliquots of 100 μl of the suspensions were added to duplicate wells of ELISpot plates and cells inoculated into a further two wells were stimulated with 20 μg/ml PHA as a positive control. The ELISpot was then carried out in the same way as for the short-term stimulation.

Spots were counted using an ELRO2 ELISpot reader system using AID-reader version 3.1.1 software (AID, Strassberg, Germany). Specific spot-forming units (SFU 105 per PBMC) were calculated as the mean negative control subtracted from the mean treatment spot count.

Proliferation assays

Following 6 day of culture, CFSE-stained cells were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD4 and PerCP-conjugated anti-CD8 antibodies and acquired as described for the phenotyping.

Analysis was carried out using FCS Express. The CD4 and CD8 T-cell populations were gated and daughter cohorts of cells that had undergone division and remaining cells that had not were assigned based on the CFSE fluorescence of the various cohorts following treatment with SEB. The precursor frequency and mean number of divisions per surviving cell were calculated. The precursor frequency was calculated by dividing the size of each daughter cohort by the number of divisions it had undergone and dividing the result by the sum of precursors and cells that had not divided. The mean number of divisions per cell was calculated by multiplying the number of cells in each daughter cohort by the number of divisions they had undergone, dividing it by the total number of divided cells and multiplying the result by the precursor frequency.

Evaluation of antibody responses

The functional antibody response to measles virus was based on the ability of patient plasma to inhibit the haemagglutinin protein of measles virus, and was carried out after Whittle et al.32 with a sensitivity of 15·6 IU/ml and a minimum detectable value of 31·2 IU/ml.

Anti-tetanus toxoid (TT) IgG levels were evaluated by ELISA (NovaTec GmBH, Dietzenbach, Germany), and robust protection was indicated at 0·1 IU/ml.33,34 Anti-Hib IgG levels were evaluated using VaccZyme ELISA (The Binding Site) and protection was indicated at 0·15 μg/ml.35,36

Analysis of data

As most of the data were not normally distributed, nonparametric analyses were used. Pairwise comparisons were carried out using Mann–Whitney U-test and significances were adjusted using the step-down Bonferroni method. Correlations were calculated using Spearman's correlation coefficients, but where large correlation matrices were generated, significant correlations were only regarded as important where they were supported by other significant correlations on similar data. Analysis was carried out using Stata 8.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) and minitab 14 (Minitab Inc., State College, PA). All tests were considered significant at P < 0·05.

Results

Cohort characteristics and CMV prevalence

The infants in the cohort had a mean birth weight of 3·07 kg, a mean length at birth of 48·7 cm, and 49% were female.

At 9 months of age, CMV infection had been diagnosed in 86 of the 132 (65%) infants sampled. Prevalence rose to 90 of 121 (74%) at 13 months and 106 of 124 (85%) at 18 months of age.

Gender ratios, birth weights and lengths at birth did not vary between CMV infected and uninfected infants at any sample time.

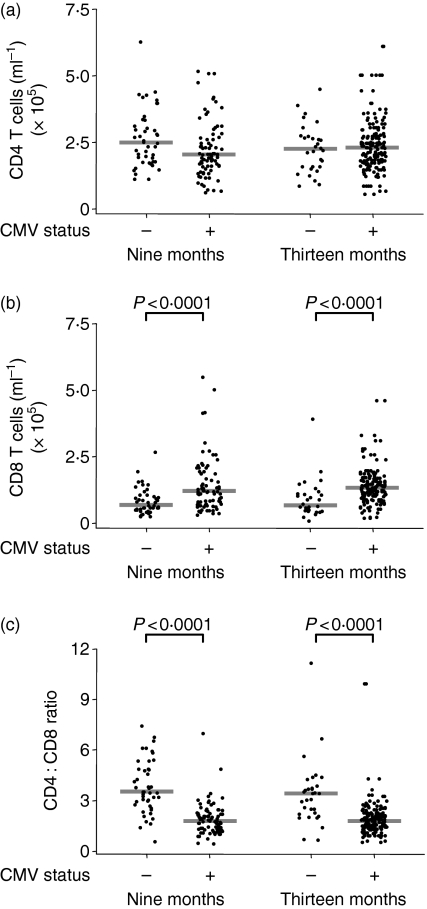

Infection with CMV induced considerable expansion and differentiation of CD8 T cells

The size of the CD4 T-cell population was unaffected by diagnosis with CMV, but the CD8 T-cell population of CMV-infected infants was more than 50% larger than that of uninfected infants (P < 0·0001), which resulted in a higher ratio of CD4 : CD8 T-cells among uninfected infants (P < 0·0001) (Fig. 1). However, CD4 : CD8 ratios below one were rare and only found in one of 45 (2·2%) CMV uninfected and seven of 81 (8·6%) CMV infected infants at 9 months, and 2 of 31 (6·5%) uninfected and 7 of 87 (8·0%) CMV infected at 13 months of age.

Figure 1.

Infants infected with cytomegalovirus (CMV) have a higher concentration of CD8 T cells in the peripheral blood. (a) Concentration of CD4 T cells, (b) concentration of CD8 T cells and (c) CD4 : CD8 ratio in CMV-infected and uninfected infants at 9 and 13 months. Bars indicate median values.

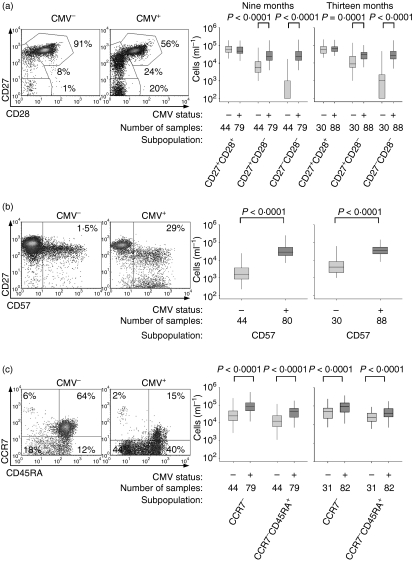

The CD8 T cells were categorized by CD27 and CD28 expression, into undifferentiated and early differentiated (CD27+ CD28+), intermediate (CD27+ CD28−) and fully differentiated (CD27− CD28−) populations.37,38 The magnitude of the early differentiated population did not differ with CMV status, but both the intermediate and fully differentiated populations were considerably larger in CMV-infected infants (P < 0·0001) (Fig. 2a). Similarly, the CD8 T cells that had lost expression of CD27 usually expressed CD57, and CD57 expression on CD8 T cells was considerably higher in CMV-infected infants (P < 0·0001) (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Infants infected with cytomegalovirus (CMV) have more differentiated CD8 T cells than uninfected infants. (a) Density plots of CD27 and CD28 expression in the CD8 T-cell population of CMV-infected and uninfected infants, selected as representative as they are the individuals with the median CD27+ CD28+ subpopulations at 9 months, and absolute sizes of all three subpopulations in all subjects. Percentages on scatter plots indicate the relative sizes of the indicated subpopulations. (b) Density plots of CD27 and CD57 expression, selected as representative as they are the individuals with the median CD57+ subpopulations at 9 months, and absolute sizes of all three subpopulations in all subjects. Percentages on scatter plots indicate the relative sizes of the indicated subpopulations. (c) Density plots of CCR7 and CD45RA expression, selected as representative as they are the individuals with the median CCR7− subpopulations at 9 months, and absolute sizes of all three subpopulations in all subjects. Percentages on scatter plots indicate the relative sizes of the subpopulations in each quadrant. Boxplots indicate median and interquartile range.

The implication that the expansion of CD8 T cells largely comprised differentiated cells was supported by the fact that the magnitudes of the CCR7+ subpopulations were unaffected by CMV status, but CMV-infected infants had larger populations of CCR7− CD8 T-cells (P < 0·0001). A substantial proportion of the CCR7− subpopulation expressed high levels of CD45RA (Fig. 2c), which is associated with replicative senescence when expressed by differentiated cells.39,40

Infection with CMV induced low levels of differentiation in the CD4 T-cell population

Unlike CD8 T-cells, CD4 T-cells lose CD27 earlier in differentiation than CD28 so the CD4 population was categorized by CD27 and CD28 expression, into early (CD27+ CD28+), intermediate (CD27− CD28+) and fully differentiated (CD27−CD28−) subpopulations.41,42 The fully differentiated subpopulation was larger in CMV-infected infants (P < 0·0001), but there were no differences in the other two subpopulations (Fig. 3a). Expression of CD57 also tended to be higher in CMV-infected infants (Fig. 3b), although the difference was only statistically significant at 13 months (P = 0·006).

Figure 3.

Infants infected with cytomegalovirus (CMV) have slightly more differentiated CD4 T-cells than uninfected infants. (a) Density plots of CD27 and CD28 expression in the CD4 T-cell population of CMV-infected and uninfected infants, selected as representative as they are the individuals with the median CD27+ CD28+ subpopulations at 9 months, and absolute sizes of all three subpopulations in all subjects. Percentages on scatter plots indicate the relative sizes of the indicated subpopulations. (b) Density plots of CD27 and CD57 expression, selected as representative as they are the individuals with the median CD57+ subpopulations at 9 months, and absolute sizes of all three subpopulations in all subjects. Percentages on scatter plots indicate the relative sizes of the indicated subpopulations. (c) Density plots of CCR7 and CD45RA expression, selected as representative as they are the individuals with the median CCR7+ CD45RA− subpopulations at 9 months, and absolute sizes of all three subpopulations in all subjects. Percentages on scatter plots indicate the relative sizes of the subpopulations in each quadrant. Boxplots indicate median and interquartile range.

Expression of CD45RA and CCR7 allowed the populations to be divided into naïve (CCR7+ CD45RA+), effector/effector memory (CCR7−CD45RA−), central memory (CCR7+ CD45RA−) and effector memory RA cells (CCR7−CD45RA+).43–45 Infants infected with CMV had slightly less central memory cells at 9 months of age (P = 0·009), but there were no other significant differences in the sizes of the subpopulations (Fig. 3c).

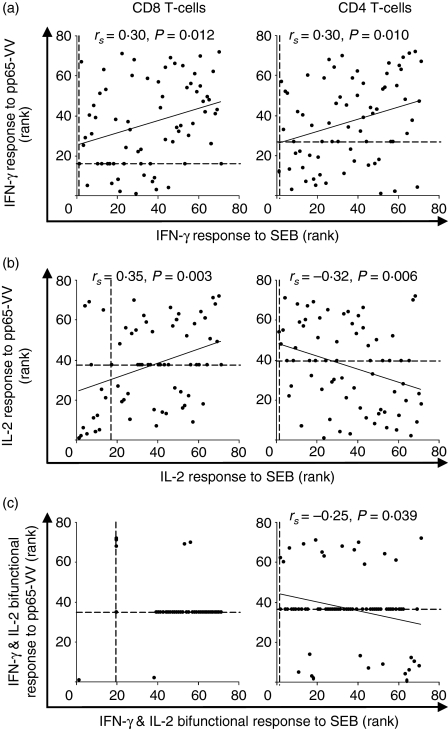

Responses to CMV correlated with enhanced effector responses by CD8 T-cells

The Ed-MV strain was a poor inducer of IFN-γ responses as measured by ELISpot following overnight stimulation, as responses were usually low and sometimes negative, indicating that fewer cells produced IFN-γ in the Ed-MV treated well than the negative control. There were no significant differences between the responses of CMV-infected infants and uninfected infants.

The IFN-γ and IL-2 responses of CD8 T-cells to Ed-MV were measured by ICS, but similarly revealed no differences between the CMV-infected and uninfected infants (data not shown). However, a median of 2·0% of the CD8 T cells of CMV-infected infants produced IFN-γ in response to SEB, which was an order of magnitude higher than the median of 0·32% of the CD8 T cells of CMV-uninfected infants (P < 0·0001) (data not shown), indicating that CMV infection induced a large subpopulation of cells with the capacity to produce IFN-γ.

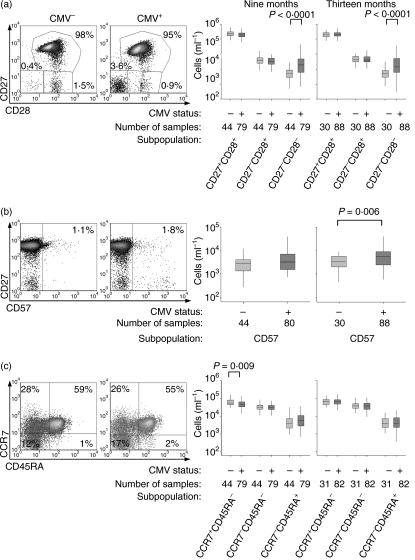

Such a suggestion is supported by the fact that the IFN-γ response to pp65-VV of the CD8 T cells correlated with the responses to SEB (rs = 0·30, P = 0·01) among CMV-infected infants. The IL-2 responses to SEB also tended to be low or absent, though a significant correlation with the responses to pp65-VV was apparent (rs = 0·35, P = 0·003). However, the CD8 T-cell response to pp65-VV did not correlate with the response to Ed-MV (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Responses of CD8 T cells to cytomegalovirus correlate positively with responses to c although the equivalent IL-2 responses of CD4 T cells correlates negatively. (a) Scatter plots of ranked proportions of IFN-γ-producing cells in response to pp65-VV and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB). (b) Scatter plots of ranked proportions of IL-2-producing cells in response to pp65-VV and SEB. (c) Scatter plots of ranked proportions of bifunctional IFN-γ- and IL-2-producing cells in response to pp65-VV and SEB. Data are ranked as correlations are non-parametric, and Spearman's correlation coefficients, significances and fitted lines are shown where correlations were significant. Dashed lines indicate rank of the zero-value.

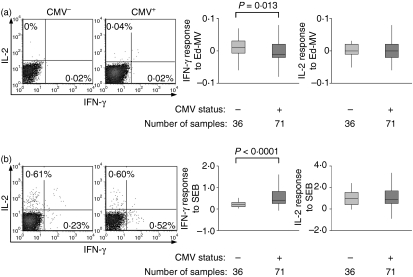

Infection with CMV reduced effector responses to measles by CD4 T cells

As with the CD8 T-cell responses, the CD4 T-cell responses to Ed-MV were frequently low or undetectable, though the median IFN-γ response was measurably lower in CMV-infected than uninfected infants (P = 0·013), probably because of a higher proportion of responders among CMV-uninfected infants (Fig. 5a). However, the median IFN-γ response to SEB was higher in CMV-infected infants (P < 0·0001) (Fig. 5b). There were no detectable differences in the IL-2 responses to either Ed-MV or SEB, or any correlation between the responses to pp65-VV and Ed-MV.

Figure 5.

The short-term CD4 T-cell response to Ed-MV and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) is slightly modulated by cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. (a) Scatter plots of the response to Ed-MV, gated on CD4 T cells and selected as representative of CMV-infected and uninfected infants as they had the median IFN-γ response among those that responded, and responses for all samples. (b) Scatter plots of the response to SEB, gated on CD4 T cells and selected as representative of CMV-infected and uninfected infants as they had the median IFN-γ response, and responses for all samples. Boxplots indicate medians and interquartile ranges.

While the IFN-γ response among CD4 T-cells to pp65-VV correlated positively with the IFN-γ response to SEB (rs = 0·30, P = 0·01), both the IL-2 (rs = −0·32, P = 0·006) and the IFN-γ and IL-2 bifunctional responses (rs = −0·25, P = 0·039) correlated negatively with the respective responses to SEB (Fig. 4).

Memory T-cell responses to measles virus were not modulated by CMV infection

The IFN-γ ELISpot generated a consistently positive if variable measure of the ex vivo T-cell response to CMV in infected 13 month old infants, with a median of 9·75 SFU 105 per PBMC (interquartile range 1·50, 26·88) among infected infants as opposed to 0·50 SFU 105 per PBMC (interquartile range −2·00, 2·00) among uninfected infants.

Following long-term restimulation, the median IFN-γ responses of the CMV-infected infants to EZ-MV was only 1·0 SFU 105 per PBMC and that of the uninfected infants was even lower although not significantly different, indicating that the vaccine strain was a poor stimulator of memory T cells. The wild type Ed-MV strain induced much stronger responses with medians of 42·5 SFU 105 per PBMC (interquartile range 18·5–149·5) for CMV-infected infants and 36·5 SFU 105 per PBMC (interquartile range 33·0–37·5) for uninfected infants, though the small magnitude and lack of significance of the difference suggests little or no influence of CMV infection.

Similarly, there were no significant differences in the proliferation of CD4 nor CD8 T cells in response to Ed-MV or EZ-MV between CMV-infected or uninfected infants.

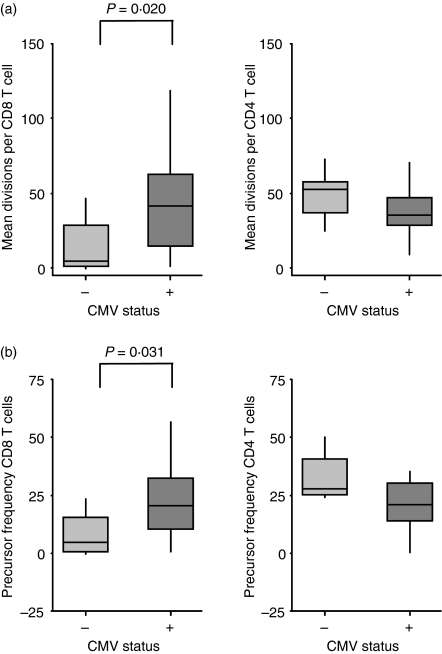

The CD8 T-cell proliferative response to SEB was enhanced by CMV infection

Following polyclonal stimulation with SEB, the median CD8 T-cell precursor frequency was around fivefold higher among CMV-infected infants (P = 0·031) and the median number of divisions per cell was 10-fold higher in infected infants (P = 0·02).

However, there were no significant differences in the proliferative responses of CD4 T cells to SEB (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Infection with cytomegalovirus increases the proliferation of CD8 T cells in response to SEB, measured by CFSE dilution. (a) Mean number of divisions per cell, calculated by subtracting the mean number of divisions among surviving cells in the negative control culture from the equivalent number in the SEB-stimulated culture. (b) Precursor frequency, calculated by subtracting the percentage of cells at the end of the culture period that had undergone at least one division in the negative control culture from the equivalent percentage in the SEB-stimulated culture. Boxplots indicate median and interquartile range.

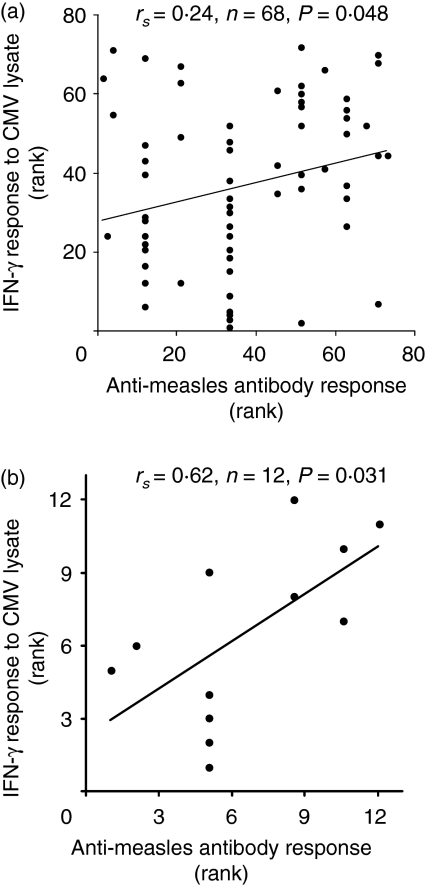

Anti-measles antibody responses correlated with the IFN-γ response to CMV

Neither CMV status at the time of vaccination nor at the time of sampling predicted a difference in the haemagglutinating antibody titre to measles at either 13 or 18 months of age. However, the IFN-γ response to CMV lysate at 13 months correlated positively with the haemagglutinating antibody titre measured at the same time (Fig. 7). There were no correlations between the antibody response to measles and any measure of T-cell responses to measles.

Figure 7.

Anti-measles antibody response correlates with IFN-γ response to cytomegalovirus (CMV) at 13 months of age. (a) Ranked anti-measles antibody response measured by HAI plotted against ranked anti-CMV IFN-γ response measured by ELISpot among infants infected with CMV at time of vaccination. (b) Ranked anti-measles antibody response measured by HAI plotted against ranked anti-CMV IFN-γ response measured by ELISpot among infants infected with CMV between vaccination and sampling. Spearman's correlation statistics and lines of best fit are shown.

Similarly, there were no significant differences in antibody responses to the tetanus or Hib vaccines based on CMV status (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anti-tetanus toxoid and anti-Hib IgG levels measured at 18 months of age

| CMV status at first DTP-Hib | + | − | − | |

| CMV status at 9 months | + | + | − | |

| Anti-TT IgG1 | Number protected/number tested | 18/19 | 12/12 | 41/41 |

| Max titre | 4·64 | 2·89 | 3·83 | |

| Geometric mean titre | 0·91 | 1·23 | 1·36 | |

| Min titre | 0·01 | 0·15 | 0·15 | |

| Anti-Hib IgG2 | Number protected/number tested | 19/19 | 12/12 | 41/41 |

| Max titre | 22·68 | 13·88 | 30·44 | |

| Geometric mean titre | 2·10 | 1·82 | 2·79 | |

| Min titre | 0·15 | 0·20 | 0·18 |

CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Responses measured in IU/ml. Robust protection indicated at 0·1 IU/ml.

Responses measured in μg/ml. Protection indicated at 0·15 μg/ml.

Discussion

Individuals with chronic CMV infection have a more differentiated peripheral blood CD8 T-cell population than uninfected individuals.2–6,13 We found an increase in the proportion of differentiated CD8 T cells was caused by an increase in the absolute number of differentiated cells, defined by loss of CCR7, CD28 and CD27, and expression of CD57. Also, the number of undifferentiated CD8 T cells was unaffected by CMV infection. Similar results have been recorded from adults,2,4,46,47 although a study carried out in Sweden only found an enlarged CD8 T-cell population in individuals aged over 85 with a CD4 : CD8 ratio >1.5

In contrast to several studies on adults in high-income countries,2–4 we did not observe an increase in the total number of CD4 T cells in CMV-infected Gambian infants, although there was a slight increase in the number of cells expressing the highly differentiated CD27− CD28− phenotype37,38,45 and also in the number expressing CD57 at 13 months of age, indicating that CMV was driving a certain amount of differentiation among the CD4 T cells although considerably less dramatically than among the CD8 T-cells.

As CMV infection expanded the CD8 but not the CD4 T-cell population, there was a drop in the CD4 : CD8 ratio. The CD4 : CD8 ratio of a healthy person typically exceeds one, and inversion of that ratio is a key component of what Pawelec et al. described as the ‘immune risk phenotype’ (IRP) 3,8,48 and related to chronic CMV infection. While the median value of the CD4 : CD8 ratio in CMV infected infants was about half that of uninfected infants, it only fell below one in very few individuals, so CMV-infected infants rarely met this criterion of the IRP. Another criterion of the IRP is a large number of differentiated (CD28− CD57+) CD8 T-cells, and accumulation of such cells was apparent in the CMV infected infants. While it was not possible to compare the absolute numbers of circulating cells to those referred to in studies of the IRP in adults because of the considerably higher peripheral blood lymphocyte concentration in infants than adults,17,18 the percentages of differentiated cells were comparable to those of adults aged over 70 in high income countries 10 although slightly lower than in those that showed impaired immune responses to influenza vaccinations.11

In spite of showing some aspects of IRP, CMV-infected infants were able to mount CD8 T-cell responses to measles vaccine that were equivalent to the responses of uninfected infants. The only measure of immune response that showed any impairment was the CD4 T-cell IFN-γ response to measles measured a week after vaccination, in spite of the fact that the phenotypical differences between the CD4 T-cell populations of CMV infected and uninfected infants were considerably milder than between the CD8 T-cell populations. As the difference in effector response was not reflected in differences in CD4 T-cell memory responses, antibody responses, or either CD8 T-cell effector or memory responses, the reduced effector response of CD4 T cells does not appear to be indicative of failure to develop a protective immune response.

By contrast, a strong T-cell response to CMV at 13 months of age as measured by IFN-γ ELISpot actually predicted a strong antibody response to measles vaccine. Previous studies on the immunomodulatory effects of CMV have focused on adult and often elderly subjects, and have shown downregulation of immune responses among individuals infected with CMV.11,12 These findings provided evidence for the theory that the immune system has a finite amount of ‘space’ and that CMV occupies much of that space by filling it with large numbers of CD8 T cells that are already committed and thus unavailable to respond to other antigens.49 However, studies on children and younger adults have shown the development of a CMV-specific CD8 T-cell subpopulation that was additional to the pre-existing subpopulations, and was maintained without interfering with EBV or influenza specific CD8 T-cell populations.46,47 The similar behaviour of the CD8 T-cell populations of the infants in the present study suggests more flexibility than in the elderly, so it is possible that the number of specificities that can be supported only becomes restricted very late in life, where most studies of influenza vaccine efficacy have been focused.4,11 The hypothesis that loss of flexibility is a feature of later life is supported by the findings that CMV-specific subpopulations expand at the expense of EBV-specific subpopulations,12 and CD28- subpopulations expand at the expense of CD28+ subpopulations,50 in people over 60 years of age but not younger.

Most of the evidence for the concept of immunological space has been gleaned from studies on CD8 T cells.49 As the slight increase in the proportion of differentiated CD4 T cells was reflected in a slight decrease in the ex vivo IFN-γ response to CMV, it is possible that there is less flexibility in the CD4 T-cell population than the CD8, in spite of far less profound phenotypic changes.

In addition to the antibody response to measles, antibody titres to the single protein preparation of tetanus toxoid and the glycoconjugate vaccine to Hib were also measured. Neither response was affected by CMV status, implying that the lack of effect on the response to measles is not peculiar to that vaccine.

Infants infected with CMV had stronger responses to polyclonal stimulus, measured by the superantigen SEB, as measured by ex vivo cytokine production and cell division. Staphylococcal superantigens stimulate T cells by binding peptide-loaded class II human leucocyte antigen (HLA) molecules on APC directly to the Vβ chains of the TCR, thus bypassing any requirement for peptide specificity or costimulation by CD4 or CD8 ligation.51 The increased capacity for IFN-γ production by the CD8 T cells in CMV-infected infants probably reflects the larger number of differentiated cells that typically produce IFN-γ rather than IL-2.52

It is also possible that CMV-infected infants simply had more peptide-loaded HLA molecules for SEB to bind to, as CMV-specific cells may comprise several percent of the circulating T-cell population 13,53 and tend to be clonally diverse,6,53,54 so would include many cells with Vβ chains that SEB can bind to. However, the loss of CD28 50,55 and expression of CD57 40 characteristic of CMV-specific T cells 2,29,37,56 is associated with short telomeres and poor replication, and it has even been suggested that CD28– CD8 T-cells exert a suppressive influence over the rest of the CD8 T-cell population.57 As division in response to SEB was actually greater in PBMC from CMV-infected infants in spite of the high proportions of CD28− CD57+ CD8 T-cells, our findings do not support the hypothesis that such cells have suppressive activity. Subpopulations of CD28− CD8 T-cells have been induced to proliferate in vitro,58 and our data supports the suggestion that their poor replication is only apparent under certain conditions of stimulation, although we were unable to establish what proportion of the cells that actually divided began by expressing the CD28− CD57+ phenotype.

It is possible that the differentiation status of the cells of CMV-infected infants is reflective of a relatively high level of background activation, which is conducive to rapid responses such as division in response to stimulation. Such an effect would be visible in response to a polyclonal stimulus, but may not affect the number of cells specific for an antigenic stimulus such as measles. Such an effect may also explain why high levels of anti-CMV activity by T cells predict high-levels of antibody production to measles virus, as CD4 T-cell-mediated help for antibody producing B cells could also be expected to be enhanced by the same mechanism.

The infant SEB responses were considerably lower than those typically recorded from healthy adults, which concurs with an earlier study that showed that infant T cells mount a relatively low IFN-γ response to polyclonal stimuli.59 Similarly low levels have been reported from SEB-stimulated T cells of healthy infants,60 although we are not aware of any study that compared the SEB responses of infants and adults directly.

In summary, in spite of the high levels of differentiation induced in infants infected with CMV and the similarities in phenotype between the CD8 T cells of CMV-infected infants and adults at high risk for vaccine failure, we found no evidence that infection with CMV and the consequent T-cell differentiation reduced the ability of the measles vaccine to induce a T-cell memory pool or a robust antibody response. Indeed, anti-measles antibody titres actually correlated with the T-cell response to CMV in CMV-infected infants and responses to polyclonal stimulus were also higher in CMV-infected infants, indicating that CMV infection may actually enhance the immune responses to some types of immune challenge in infancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Sukuta birth cohort, Omar Badjie, Fatou Bah, Modou Bah, Saihou Bobb, Sarah Burl, Janko Camara, Sulayman Colley, Momodou Cox, Louise Downs, Isatou Drammeh, Mam Maram Drammeh, Momodou Lamin Fatty, Tisbeh Faye-Joof, Steve Kaye, Elishia Roberts, Bala Musa Sambou, Sarjo Sanneh, Lady Chilel Sanyang, Mohammed Tunkara and Pauline Waight. We are grateful for the support of Sally Savage of Sukuta Health Centre and the Western Division Health Team. The pp65-VV and T7-VV were a gift from Vincenzo Cerundolo of the Institute for Molecular Medicine, Oxford, UK. The study was funded by MRC.

References

- 1.Pass RF. Epidemiology and transmission of cytomegalovirus. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:243–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gratama JW, Naipal AM, Oosterveer MA, et al. Effects of herpes virus carrier status on peripheral T lymphocyte subsets. Blood. 1987;70:516–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsson J, Wikby A, Johansson B, Löfgren S, Nilsson B-O, Ferguson F. Age-related change in peripheral blood T-lymphocyte subpopulations and cytomegalovirus infection in the very old: the Swedish longitudinal OCTO immune study. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;121:187–201. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Looney R, Falsey A, Campbell D, et al. Role of cytomegalovirus in the T cell changes seen in elderly individuals. Clin Immunol. 1999;90:213–9. doi: 10.1006/clim.1998.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wikby A, Johansson B, Olsson J, Lofgren S, Nilsson BO, Ferguson F. Expansions of peripheral blood CD8 T-lymphocyte subpopulations and an association with cytomegalovirus seropositivity in the elderly: the Swedish NONA immune study. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:445–53. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan N, Shariff N, Cobbold M, et al. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8 T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J Immunol. 2002;169:1984–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberger B, Lazuardi L, Weiskirchner I, et al. Healthy aging and latent infection with CMV lead to distinct changes in CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell subsets in the elderly. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawelec G, Ferguson F, Wikby A. The SENIEUR protocol after 16 years. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;122:132–4. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saurwein-Teissl M, Lung T, Marx F, et al. Lack of antibody production following immunization in old age: association with CD8+ CD28− T cell clonal expansions and an imbalance in the production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines. J Immunol. 2002;168:5893–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorozny J, Fulbright J, Crowson C, Poland G, O'Fallon W, Weyland C. Value of immunological markers in predicting responsiveness to influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J Virol. 2001;75:12182–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12182-12187.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trzonkowski P, Mysliwska J, Szmit E, et al. Association between cytomegalovirus infection, enhanced proinflammatory response and low level of anti-hemagglutinins during the anti-influenza vaccination – an impact of immunosenescence. Vaccine. 2003;21:3826–36. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan N, Hislop A, Gudgeon N, et al. Herpesvirus-specific CD8 T cell immunity in old age: cytomegalovirus impairs the response to a coresident EBV infection. J Immunol. 2004;173:7481–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miles D, van der Sande M, Jeffries D, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in Gambian infants leads to profound CD8 T cell differentiation. J Virol. 2007;81:5766–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00052-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton E, White D, Cathelyn J, et al. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature. 2007;447:326–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsegaye A, Wolday D, Otto S, et al. Immunophenotyping of blood lymphocytes at birth, during childhood, and during adulthood in HIV-1-uninfected Ethiopians. Clin Immunol. 2003;109:338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzardini G, Trabattoni D, Saresella M, et al. Immune activation in HIV-infected African individuals. Italian–Ugandan AIDS cooperation program. AIDS. 1998;12:2387–96. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries E, de Bruin-Versteeg S, Comans-Bitter W, et al. Longitudinal survey of lymphocyte subpopulations in the first year of life. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:528–37. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200004000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shearer W, Rosenblatt H, Gelman R, et al. Lymphocyte subsets in healthy children from birth through 18 years of age: the pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group P1009 Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:973–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henao-Restrepo A, Strebel P, John Hoekstra E, Birmingham M, Bilous J. Experience in global measles control, 1990–2001. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(Suppl. 1):S15–21. doi: 10.1086/368273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynn T, Beller M, Funk E, et al. Incremental effectiveness of 2 doses of measles-containing vaccine compared with 1 dose among high school students during an outbreak. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(Suppl. 1):S86–90. doi: 10.1086/377699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitek C, Aduddell M, Brinton M, Hoffman R, Redd S. Increased protections during a measles outbreak of children previously vaccinated with a second dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:620–3. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janaszek W, Gay N, Gut W. Measles vaccine efficacy during an epidemic in 1998 in the highly vaccinated population of Poland. Vaccine. 2003;21:473–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malfait P, Jataou I, Jollet M, Margot A, De Benoist A, Moren A. Measles epidemic in the urban community of Niamey: transmission patterns, vaccine efficacy and immunization strategies, Niger, 1990 to 1991. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cisse B, Aaby P, Simondon F, Samb B, Soumaré M, Whittle H. Role of schools in the transmission of measles in rural Senegal: implications for measles control in developing countries. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:295–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aaby P, Knudsen K, Jensen T, et al. Measles incidence, vaccine efficacy, and mortality in two urban African areas with high vaccination coverage. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1043–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.5.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norrby E, Gollmar Y. Appearance and persistence of antibodies against different virus components after regular measles infections. Infect Immun. 1972;6:240–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.3.240-247.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaye A, Magnusen A, Whittle H. Human leukocyte antigen class I- and class II-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to measles antigens in immune adults. J Infect Dis. 1997;177:1282–9. doi: 10.1086/515271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Permar S, Klumpp S, Mansfield K, et al. Limited contribution of humoral immunity to the clearance of measles viremia in rhesus monkeys. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:998–1005. doi: 10.1086/422846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchant A, Appay V, van der Sande M, et al. Mature CD8+ T lymphocyte response to viral infection during fetal life. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1747–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI17470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preiser W, Bräuninger S, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic methods for the detection of cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplants. J Clin Virol. 2001;20:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(00)00156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes K, Alford C, Britt W. Antibody response to virus-encoded proteins after cytomegalovirus mononucleosis. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:615–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittle H, Mann G, Eccles M, et al. Effects of dose and strain of vaccine on success of measles vaccination of infants aged 4–5 months. Lancet. 1988;331:963–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonsen O, Bentzon M, Heron I. ELISA for the routine determination of antitoxic immunity to tetanus. J Biol Stand. 1986;14:231–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-1157(86)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melville-Smith M, Seagroatt V, Watkins J. A comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the toxin neutralization test in mice as a method for the estimation of tetanus antitoxin in human sera. J Biol Stand. 1983;11:137–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-1157(83)80038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schauer U, Stemberg F, Rieger C, et al. Levels of antibodies specific to tetanus toxoid, Haemophilus influenzae type b, and pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide in healthy children and adults. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:202–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.2.202-207.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Käyhty H. Difficulties in establishing a serological correlate of protection after immunization with Haemophilus influenzae conjugate vaccines. Biologicals. 1994;22:397–402. doi: 10.1006/biol.1994.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat Med. 2002;8:379–85. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Lier R, ten Berge I, Gamadia L. Human CD8+ T-cell differentiation in response to viruses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:1–8. doi: 10.1038/nri1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamann D, Kostense S, Wolthers K, Otto S, Baars P, Miedema F, van Lier R. Evidence that human CD8+ CD45RA+CD27− cells are induced by antigen and evolve through extensive rounds of division. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1027–33. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.7.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brenchley J, Karandikar N, Betts M, et al. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101:2711–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fletcher J, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Dunne P, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T cells in healthy carriers are continuously driven to replicative exhaustion. J Immunol. 2005;175:8218–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovaiou R, Weiskirchner I, Keller M, Pfister G, Cioca D, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Age-related differences in phenotype and function of CD4+ T cells are due to a phenotypic shift from naive to memory effector CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1359–66. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–12. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Champagne P, Ogg G, King A, et al. Skewed maturation of memory HIV-specific CD8 T lymphocytes. Nature. 2001;410:106–11. doi: 10.1038/35065118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seder R, Ahmed R. Similarities and differences in CD4+ and CD8+ effector and memory T cell generation. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:835–42. doi: 10.1038/ni969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Leeuwen E, Koning J, Remmerswaal E, van Baarle D, van Lier R, ten Berge I. Differential usage of cellular niches by cytomegalovirus versus EBV- and influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:4998–5005. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuijpers T, Vossen M, Gent M-R, et al. Frequencies of circulating cytolytic, CD45RA+ CD27−, CD8+ T lymphocytes depend on infection with CMV. J Immunol. 2003;170:4342–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pawelec G, Akbar A, Caruso C, Effros R, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Wikby A. Is immunosenescence infectious? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:406–10. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pawelec G, Gouttefangeas C. T-cell dysregulation caused by chronic antigenic stress: the role of CMV in immunosenescence? Aging Clin Exp Res. 2006;18:171–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03327436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nociari MM, Telford W, Russo C. Postthymic development of CD28− CD8+ T cell subset: age-associated expansion and shift from memory to naive phenotype. J Immunol. 1999;162:3327–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, Llera A, Tsuchiya D, et al. Three-dimensional structure of the complex between a T cell receptor beta chain and the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Immunity. 1998;9:807–16. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamann D, Baars P, Rep M, Hooibrink B, Kerkhof-Garde S, Klein M, Van Lier RAW. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1407–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sylwester A, Mitchell B, Edgar J, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202:673–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weekes MP, Wills MR, Mynard K, Carmichael AJ, Sissons PJG. The memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response to human cytomegalovirus infection contains individual peptide-specific CTL clones that have undergone extensive expansion in vivo. J Virol. 1999;73:2099–108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2099-2108.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boucher N, Dufeu-Duchesne T, Vicaut E, Farge D, Effros RB, Schachter F. CD28 expression in T cell aging and human longevity. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33:267–82. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(97)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen S, Tu W-W, Sharp M, et al. Antiviral CD8 T cells in the control of primary human cytomegalovirus infection in early childhood. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1619–27. doi: 10.1086/383249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Effros R. Role of T lymphocyte replicative senescence in vaccine efficacy. Vaccine. 2007;25:599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wills MR, Okecha G, Weekes MP, Gandhi MK, Sissons PJ, Carmichael AJ. Identification of naive or antigen-experienced human CD8+ T cells by expression of costimulation and chemokine receptors: analysis of the human cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T cell response. J Immunol. 2002;168:5455–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ehlers S, Smith K. Differentiation of T cell lymphokine gene expression: the in vitro acquisition of T cell memory. J Exp Med. 1991;173:25–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCloskey T, Haridas V, Pontrelli L, Pahwa S. Response to superantigen stimulation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from children perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus and receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:957–62. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.5.957-962.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]