Abstract

Airway epithelium is emerging as a regulator of innate immune responses to a variety of insults including cigarette smoke. The main goal of this study was to explore the effects of cigarette smoke extracts (CSE) on Toll-like receptor (TLR) expression and activation in a human bronchial epithelial cell line (16-HBE). The CSE increased the expression of TLR4 and the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding, the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation, the release of interleukin-8 (IL-8) and the chemotactic activity toward neutrophils. It did not induce TLR2 expression or extracellular signal-regulated signal kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) activation. The LPS increased the expression of TLR4 and induced both NF-κB and ERK1/2 activation. The combined exposure of 16-HBE to CSE and LPS was associated with ERK activation rather than NF-κB activation and with a further increase of IL-8 release and of chemotactic activity toward neutrophils. Furthermore, CSE decreased the constitutive interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) release and counteracted the effect of LPS in inducing both the IP-10 release and the chemotactic activity toward lymphocytes. In conclusion, cigarette smoke, by altering the expression and the activation of TLR4 via the preferential release of IL-8, may contribute to the accumulation of neutrophils within the airways of smokers.

Keywords: airway epithelial cell, cigarette smoke, Toll-like receptors

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is mainly caused by cigarette smoke exposure and is characterized by the occurrence of recurring infections of the airways which play a crucial role in the progression of the disease and in the decline of respiratory functions.1–3

A key component of the innate immunity and of the innate defence mechanisms against infections is represented by the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family.4 Among the TLRs, the most studied are the TLR4 and the TLR2. The TLR4 recognizes mainly Gram-negative bacteria via the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) moiety present on the surface of these microorganisms while TLR2 induces responsiveness to bacterial lipoproteins and to components of Gram-positive bacteria such as peptidoglycan.5 After stimulation with bacterial products both receptors trigger the cell to produce inflammatory mediators via the activation of a protein (MyD88)5 which, in turn, promotes the activation of signalling pathways, including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), leading to the activation of the synthesis of inflammatory mediators and of adhesion molecules.5 Both TLR2 and TLR4, predominantly expressed by monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils,6 are also expressed by lung and bronchial epithelial cells.7 The airway epithelium is active in airway defence mechanisms by releasing cytoprotective mucus and defensins and exerts an important role in coordinating local inflammation and immune responses through the generation of cytokines and chemokines.8 In this regard, it has been demonstrated that airway epithelium upon stimulation is able to release interleukin-8 (IL-8) and interferon-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10)9 exerting a chemotactic activity toward neutrophils and lymphocytes, respectively, thus amplifying the inflammatory and immune responses.

Although it is known that cigarette smoke exposure is a major determinant of COPD and that the presence of recurrent infections of the airways plays a crucial role in the progression of COPD, the effect of cigarette smoke exposure on inflammation and on the innate immunity of the airway epithelium remains poorly understood.

Therefore, we sought to understand whether inflammatory and host defence determinants are affected by cigarette smoke exposure. The aims of the present study were to evaluate whether cigarette smoke exposure:

(1) alters the expression of TLRs; (2) affects the molecular events downstream from the activation of TLRs; (3) modifies the release of specific chemokines; (4) leads to the recruitment of other cells that are crucially involved in the pathogenesis of COPD.

Materials and methods

Preparation of cigarette smoke extracts (CSE)

Commercial cigarettes (Marlboro) were used in this study. Cigarette smoke solution was prepared as described previously10 with some modifications. Each cigarette was smoked for 5 min and one cigarette was used per 25 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to generate a CSE-PBS solution. The CSE solution was filtered through a 0·22-μm pore filter to remove bacteria and large particles. The smoke solution was then adjusted to pH 7·4 and used within 30 min of preparation. This solution was considered to be 100% CSE and was diluted to obtain the desired concentration in each experiment. The concentration of CSE was calculated spectrophotometrically measuring the optical density as previously described11 at a wavelength of 320 nm. The pattern of absorbance among different batches showed very few differences and the mean optical density of the different batches was 1·37 ± 0·16. The presence of contaminating LPS on undiluted CSE was assessed by a commercially available kit (Cambrex Corporation, East Rutherfort, NJ) and was below the detection limit of 0·1 EU/ml.

Stimulation of 16-HBE

The immortalized normal bronchial epithelial cell line 16-HBE was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco) and 1% weight per volume penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco).12 Cell cultures were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°. The 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of endotoxin (LPS 1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and in the presence and in the absence of different concentrations of CSE for 18 hr to evaluate the ability of these products to affect the expression and the activation of TLR4. The optimal time-points were selected on the basis of preliminary experiments. In some experiments PD98059 (Sigma; 25 μm; 30 min) or BAY117082 (Sigma; 50 μm; 30 min), inhibitors of ERK1/2 and of NF-κB, respectively, were added to the cultures before stimulation with CSE or LPS. At the end of stimulation, cell pellets, cell extracts and cell culture supernatants were collected for further evaluations. Cell apoptosis in the presence of the maximum CSE concentrations (20%) used was evaluated by staining with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide using a commercial kit (Bender MedSystem, Vienna, Austria) following the manufacturer's directions. Cells were analysed using a FACStar Plus (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) analyser equipped with an Argon ion Laser (Innova 70 Coherent; Becton Dickinson) and Consort32 computer support. The propidium-negative and annexin-V-negative cells (i.e. viable cells) were present in the lower left quadrant; the propidium-positive cells (i.e. necrotic cells) were present in the upper left quadrant; the propidium and annexin V double-positive cells (i.e. late apoptotic cells) were present in the upper right quadrant and the single annexin-V-positive cells (i.e. early apoptotic cells) were present in the lower right quadrant.

Expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in 16-HBE cells

To evaluate the expression of TLR2 and TLR4, cells were permeabilized using a commercial fix-perm cell permeabilization kit (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), incubated in the dark (30 min, 4°) with specific rabbit monoclonal antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) followed by a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark) and then evaluated by flow cytometry In some experiments non-permeabilized and permeabilized cells (n = 3) were included to assess the expression of TLR4 inside and outside the cells. Negative controls were performed using rabbit immunoglobulins (Dako). Data are expressed as geomean fluorescence intensity.

Binding of LPS

The binding of LPS was assessed using ALEXA fluor LPS (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). In particular, 16-HBE cells, stimulated as described above, were incubated with ALEXA fluor LPS for 30 min and the binding of LPS was evaluated by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as geomean fluorescence intensity.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis of TLR4 expression by 16-HBE cells

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed as previously described.13 The 16-HBE cells were stimulated with CSE and LPS (1 μg/ml) for 6, 12 and 18 hr and total cellular RNA was extracted using an RNAzol kit (Biotech Italia, Rome, Italy). This was then reverse-transcribed to complementary DNA, using Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (M-MLV-RT) and oligo-dT (12–18) primer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Real-time quantitative PCR of the human TLR4 gene was carried out on ABI PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detection Systems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using specific 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labelled probe and primers (Applied Biosystems, TaqMan Assays on Demand). GAPDH gene expression was used as the endogenous control for normalization. Relative quantification of messenger RNA was carried out using a comparative cycles threshold (CT) method.

Expression and activation of NF-κB

To study the expression and nuclear translocation of NF-κB, the cytoplasmic and nuclear protein fractions were separated using a commercial kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Western blot analysis, using a polyclonal antibody recognizing subunit p65 of NF-κB (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was then performed on these separated protein fractions. Detection was performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (NEN, Boston, MA), followed by autoradiography. Negative controls were performed in the absence of primary antibody or including an isotype control antibody. β-Actin (Sigma) was used as a housekeeping protein. Gel images were taken with an EPSON GT-6000 scanner (Hemel Hempstead, UK) and then imported to a National Institutes of Health Image analysis 1.61 program to determine band density. To assess NF-κB activation we used a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (SuperArray Bioscience, Frederick, MD) that measures the phosphorylated NF-κB (pNF-κB) and the total NF-κB (tNF-κB). Results are expressed as the ratio of pNF-κB to tNF-κB.

Expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2

The expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2 was evaluated by Western blot analysis as previously described using a polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). To assess ERK activation we used a commercially available ELISA kit (SuperArray Bioscience) that measures the phosphorylated ERK (pERK) and the total ERK (tERK). Results are expressed as the pERK : tERK ratio.

Measurement of IL-8 and of IP-10

The concentrations of IL-8 and IP-10 were determined using an ELISA (Quantikine; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). In some experiments (n = 4), the samples were evaluated for IL-8 production in the presence and in the absence of a TLR4 blocking peptide (eBioscience, San Diego, CA; 10 μg/106 cells, 1 hr before stimulation).

Chemotaxis of neutrophils

Neutrophils were purified from normal donors14 and chemotaxis toward neutrophils was performed as previously described14 using a micro-chamber (Costar Neuro Probe Inc., Cabin John, MD). To assess whether IL-8 was responsible for neutrophil migration, blocking experiments were performed by mixing the cell culture supernatants with an anti-human IL-8 monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems) for 30 min at 37° before loading the chamber. Results were expressed as number of transmigrated cells.

Chemotaxis of lymphocytes

Lymphocytes were purified from normal donors15 and chemotaxis toward lymphocytes was performed as previously described15 using a micro-chamber (Costar Neuro Probe Inc.). Results were expressed as number of transmigrated cells.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean counts ± standard deviations. The comparison between different experimental conditions was evaluated by analysis of variance (anova) with the Bonferroni test. P < 0·05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

CSE increase the expression of TLR4 in 16-HBE cells

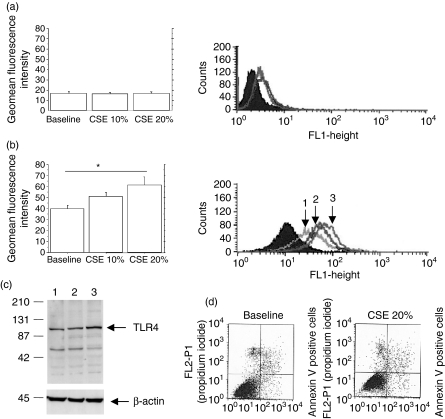

To explore whether CSE are able to affect the expression of innate immunity receptors, confluent 16-HBE cells were stimulated with CSE and then evaluated for their expression of TLR2 and TLR4. The exposure of 16-HBE cells to CSE did not increase the expression of TLR2 (Fig. 1a) but increased the expression of TLR4 (Fig. 1b) in a dose-dependent manner. Western blot analyses (Fig. 1c) and flow cytometry experiments with permeabilized cells confirmed the ability of CSE to increase the total production of TLR4 protein (inside the cells and on their surface). Flow cytometry analyses (n = 3) performed with non-permeabilized cells (geomean baseline = 18 ± 1·5; CSE 10% = 21 ± 1·5; CSE 20% = 25 ± 2) clarified that CSE not only increase total TLR4 protein expression but also promote an increase in the expression of TLR4 on the surface of the cells. To explore whether CSE at the highest tested concentration induce cell apoptosis, we evaluated the percentage of annexin-V-positive cells by flow cytometry. The percentage of apoptotic cells in the presence of CSE 20% was similar to the baseline condition (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) induces Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) expression by bronchial epithelial cells (n = 5). 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of different concentrations of CSE (10% and 20%) for 18 hr and were used to assess TLR2 and TLR4 expression (see Materials and methods for details). The expression of TLR2 (a) and TLR4 (b) was evaluated by flow cytometry and the results are expressed as geomean fluorescence intensity ± SD; *P < 0·05. At the right of panel (a) is a representative histogram plot of the TLR2 expression and at the right of panel (b) is a representative histogram plot of the TLR4 expression: shaded curve = negative control; open curve 1 = baseline; open curve 2 = CSE 10%; open curve 3 = CSE 20%. (c) Representative Western blot showing the expression of TLR4 at baseline level (lane 1) and following the exposure to CSE 10% (lane 2) and to CSE 20% (lane 3). Membranes were then stripped and incubated with goat polyclonal anti-β-actin. (d) Representative dot plots showing the percentage of annexin-V-positive 16-HBE cells at baseline and following exposure to CSE 20%. The annexin-V-positive cells are present in the upper and lower right quadrants.

CSE increase the binding of LPS to 16-HBE cells

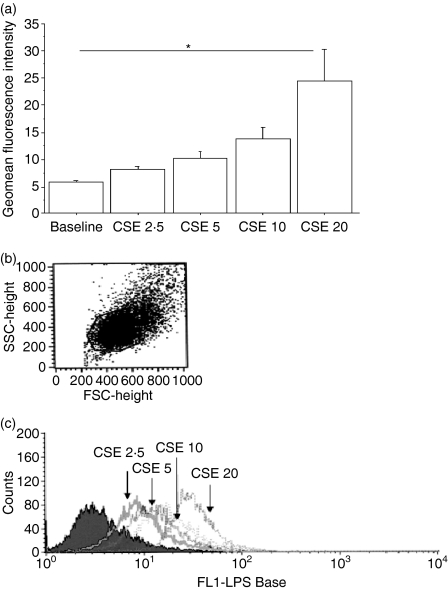

Since CSE were able to increase the expression of TLR4, the effect of CSE on the ability of 16-HBE cells to bind LPS, the ligand of TLR4, was determined. Interestingly, when the cells were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of CSE, a dose-dependent increase in LPS binding was observed (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 2.

Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) increases lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding by bronchial epithelial cells (n = 5). 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and absence of different concentrations of CSE for 18 hr and were used to assess LPS binding by flow cytometry using ALEXA fluor LPS (see Materials and methods for details) (a). Results are expressed as geomean fluorescence intensity ± SD; *P < 0·05. (b) Representative dot plots of the 16-HBE cells evaluated for assessing LPS binding. (c) Representative histogram showing the expression of ALEXA fluor LPS.

CSE increase the LPS-induced expression of TLR4 in 16-HBE cells

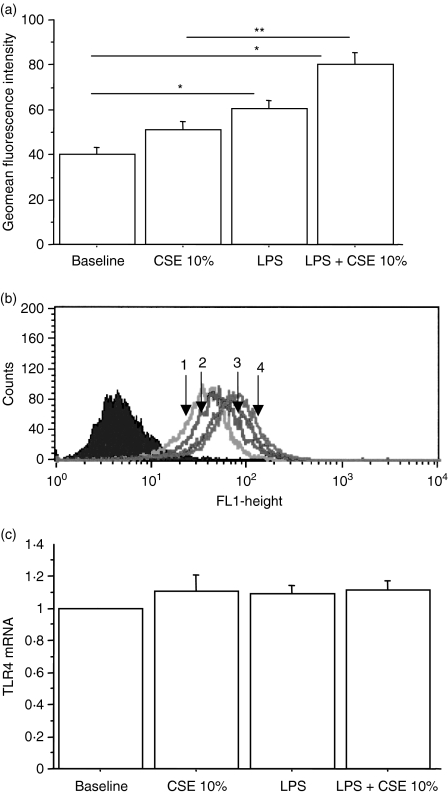

Experiments were designed to clarify whether CSE may affect the activity of LPS in the modulation of TLR4 expression.16 LPS alone was able to increase the expression of TLR4 and this effect was further increased by coculturing the cells with CSE 10% (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

The combined exposure to cigarette smoke extracts (CSE) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increases Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) protein expression by bronchial epithelial cells (n = 5). 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of CSE 10% and of LPS (1 μg/ml) for 18 hr. The expression of TLR4 protein (a) was evaluated by flow cytometry and the results are expressed as geomean fluorescence intensity ± SD; *P < 0·05 versus baseline, **P < 0·05 versus CSE alone. (b) Representative histogram showing the expression of TLR4 protein. Closed curve = negative control; open curve 1 = baseline; open curve 2 = CSE 10%; open curve 3 = LPS; open curve 4 = CSE 10% + LPS. (c) TLR4 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression was quantified by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. GAPDH RNA was used for normalization. Data are expressed as fold induction over baseline condition.

Real-time PCR experiments were performed to assess whether the increased expression of TLR4 protein was associated with an increased messenger RNA expression. After 18 hr of stimulation LPS and CSE were unable to induce a significantly increased expression of TLR4 messenger RNA, either alone or in combination (Fig. 3b). Similar results were obtained after 6 and 12 hr of stimulation (data not shown).

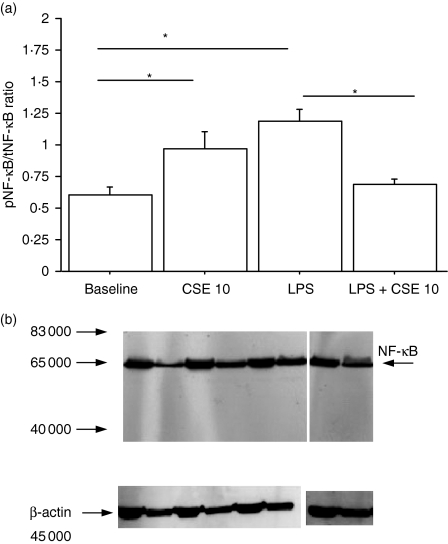

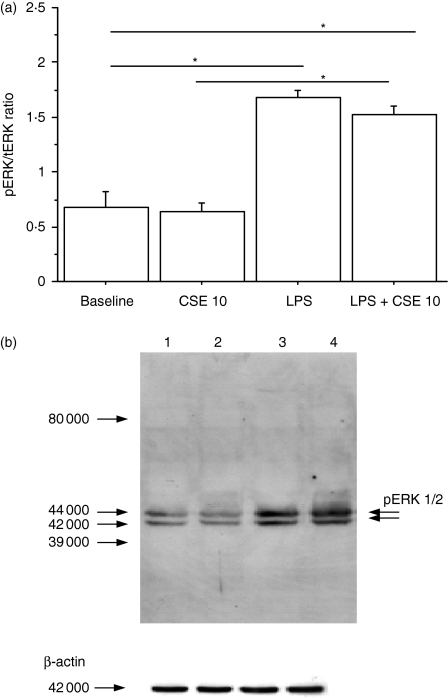

Effects of CSE on NF-κB and on pERK1/2 pathways

To determine whether the increase in LPS binding due to CSE exposure leads to an increased activation of some mechanisms downstream from LPS binding, the NF-κB and ERK pathways were explored. The NF-κB pathway was evaluated by assessing the pNF-κB : tNF-κB ratio (Fig. 4a) and the nuclear expression of NF-κB was investigated using Western blot analysis (Fig. 4b). The CSE and LPS alone were able to increase both the pNF-κB : tNF-κB ratio (Fig. 4a) and the nuclear expression of NF-κB (Fig. 4b), which suggested an activation of the NF-κB pathway. Conversely, CSE in combination with LPS significantly decreased the pNF-κB : tNF-κB ratio (Fig. 4a) and the nuclear expression of NF-κB (Fig. 4b) observed in the presence of LPS alone. To investigate the ERK pathway, the pERK : tERK ratio (Fig. 5a) was evaluated and pERK1/2 expression was assessed using Western blot analysis; LPS, but not CSE, was able to increase both the pERK : tERK ratio (Fig. 5a) and the pERK1/2 expression (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, when LPS and CSE were simultaneously added to 16-HBE cell cultures increases of the pERK : tERK ratio (Fig. 5a) and of pERK1/2 expression (Fig. 5b) were observed, suggesting that CSE did not interfere with ERK phosphorylation processes.

Figure 4.

Effect of cigarette smoke extract (CSE) on nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation (n = 5). 16-HBE cells, cultured in the presence and in the absence of CSE 10% and of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/ml) for 18 hr, were used for evaluating the NF-κB pathway. (a) NF-κB activity was evaluated using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. Data are expressed as the ratio of phosphorylated NF-κB (pNF-κB) to total NF-κB (tNF-κB); *P < 0·05. (b) Representative Western blot performed on cytoplasmic (C) and nuclear (N) extracts. Lane 1 = baseline; lane 2 = CSE 10%; lane 3 = LPS (1 μg/ml); lane 4 = CSE 10% and LPS (1 μg/ml). Membranes were then stripped and incubated with goat polyclonal anti-β-actin.

Figure 5.

Effect of cigarette smoke extracts (CSE) on extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) activation (n = 5). 16-HBE cells, cultured in the presence and in the absence of CSE 10% and of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/ml) for 18 hr, were used to assess the ERK1/2 pathway. (a) ERK1/2 activation was evaluated using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. Data are expressed as the ratio of phosphorylated ERK1/2 (ERK1/2) to total ERK1/2 (tERK1/2); *P < 0·05. (b) Representative Western blot of pERK1/2. Lane 1 = baseline; lane 2 = CSE 10%; lane 3 = LPS (1 μg/ml); lane 4 = CSE 10% and LPS (1 μg/ml). Membranes were then stripped and incubated with goat polyclonal anti-β-actin.

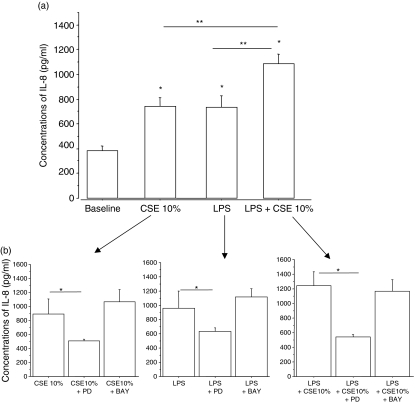

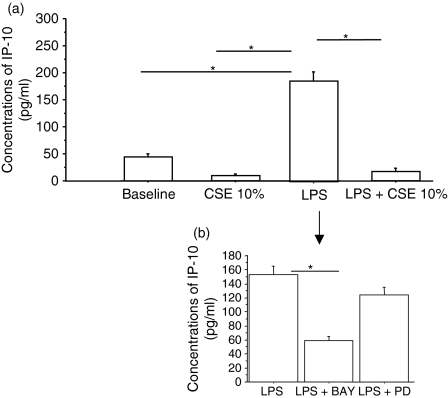

Effects of CSE on IL-8 and IP-10 release

The activation of NF-κB and ERK pathways induces the expression of proinflammatory mediators. To assess whether CSE affect the cytokine release profile of 16-HBE cells, IL8 and IP-10 concentrations were measured in the culture supernatants. Following stimulation with LPS, the release of both IL-8 (Fig. 6a) and IP-10 (Fig. 7a) was significantly increased. Surprisingly, while CSE exposure induced the release of IL-8 (Fig. 6a), it decreased the spontaneous release of IP-10 (Fig. 7a). The combined presence of both LPS and CSE inhibited IP-10 release (Fig. 7a) while it significantly further increased the release of IL-8 (Fig. 6a). The ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059, but not the inhibitor of NF-κB BAY117082, reduced the release of IL-8 (Fig. 6b). Conversely, the inhibitor of NF-κB, BAY117082, but not the inhibitor of ERK1/2, PD98059, reduced the release of IP-10 (Fig. 7b). Neither inhibitor induced a significant alteration of the constitutive production of IL-8 (baseline = 404 ± 155; baseline + BAY117082 = 539 ± 212; baseline + PD98059 = 343 ± 93) (n = 3). Moreover, the block of TLR4 activation was unable to reduce IL-8 production generated by the stimulation with CSE and LPS in combination (LPS + CSE, IL-8 = 1053 ± 189; CSE + LPS + TLR4 blocking, IL-8 = 1042 ± 158) suggesting that IL-8 release may be sustained in the presence of a block of TLR4 by other pathways.

Figure 6.

Effect of cigarette smoke extracts (CSE) on interleukin-8 (IL-8) release by bronchial epithelial cells (n = 5). 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of CSE 10% and of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/ml) for 18 hr. The supernatants were collected and used for evaluating IL-8 (a) concentrations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. In some experiments (n = 3) 16-HBE cells were preincubated for 30 min with PD98059 (25 μm) or BAY117082 (50 μm) (b). *P < 0·05 versus baseline, **P < 0·05 versus CSE or LPS alone.

Figure 7.

Effect of cigarette smoke extracts (CSE) on interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) release by bronchial epithelial cells (n = 5). 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of CSE 10% and of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/ml) for 18 hr. The supernatants were collected and used to evaluate IP-10 concentrations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (a). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. In some experiments (n = 3) 16-HBE were preincubated for 30 min with PD98059 (25 μm) or BAY117082 (50 μm) (b); *P < 0·05.

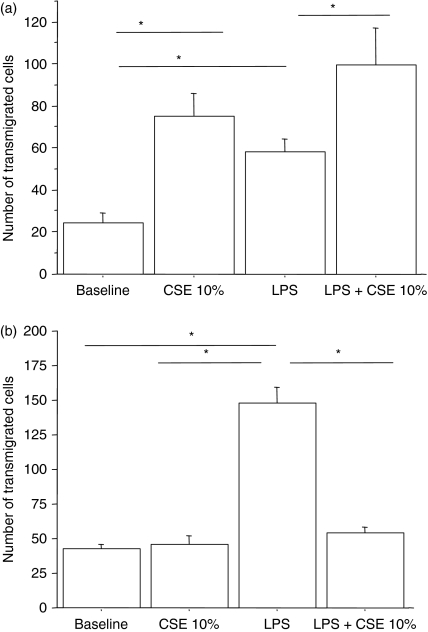

Effects on neutrophil and lymphocyte chemotaxis

Since the stimulation of 16-HBE cells with cigarette smoke and/or LPS promoted the release of the chemokine IL-8, we assessed whether stimulated 16-HBE cells generated a chemotactic activity toward neutrophils. Interestingly, following stimulation with CSE alone and in combination with LPS, 16-HBE released soluble mediators with chemotactic activity toward neutrophils (Fig. 8a). The presence of anti-IL-8 significantly reduced the chemotactic activity toward neutrophils, demonstrating that the IL-8 released following stimulation with cigarette smoke and LPS is biologically active and plays an important role in the chemotactic activity for neutrophils (Table 1). Finally, because the exposure to CSE negatively interfered with the IP-10 release by 16-HBE cells and because it is well known that IP-10 exerts a chemotactic activity toward lymphocytes, we assessed the effect of CSE on the chemotaxis toward lymphocytes. While LPS induced a significant chemotactic activity toward lymphocytes, CSE did not. The combined exposure to CSE and LPS dramatically reduced the lymphocyte chemotaxis activity generated by LPS stimulation (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8.

Effect of cigarette smoke extract (CSE) on neutrophil and lymphocyte chemotactic activities released by bronchial epithelial cells (n = 5). 16-HBE cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of CSE 10% and of lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 1 μg/ml) for 18 hr. Cell supernatants were collected and were used to stimulate chemotaxis toward neutrophils (a) and lymphocytes (b) using a micro-chamber (see Materials and methods for details). Data are expressed as number of transmigrated cells; *P < 0·05.

Table 1.

Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by anti-interleukin-8 (n = 6)

| Baseline | 15 ± 3% |

| CSE 10% | 55 ± 17% |

| LPS | 49 ± 8% |

| LPS+CSE 10% | 56 ± 12% |

CSE, cigarette smoke extracts; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Discussion

Cigarette smoke exposure represents the major risk factor for COPD, which is characterized by progressive and largely irreversible airway obstruction sustained by a massive infiltration/activation into the lungs of inflammatory cells that establish complex and highly dynamic interactions with resident epithelial cells.17 Recurrent infections of the airways play a crucial role in the progression of COPD and in the decline of respiratory function.1–3 In the present study we created an experimental model reproducing a situation of a smoker subject exposed to microbial products using a bronchial epithelial cell line to better understand whether the exposure to cigarette smoke alters the normal response of the epithelium to infections. We demonstrate that CSE increase the expression of TLR4 and the ability to bind LPS and orientate the activation of TLR4 toward an increased release of IL-8 and a reduced release of IP-10 with a preferential activation of ERK rather than the NF-κB pathway. These events lead to an increased neutrophil chemotaxis and to a reduced lymphocyte chemotaxis, so altering the balance between the innate and adaptive responses generated by the epithelium upon microbial stimulation.

The surface of the airway epithelium represents a battleground in which the host intercepts signals from pathogens and activates epithelial defences against infections. A prerequisite for the initiation of host responses is the recognition of pathogens by the host immune system. Tremendous progress in this field was the discovery that the 10 germline-encoded human TLRs comprising the TLR family act as transmembranous pattern recognition receptors, detecting a large variety of conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns.6 Airway epithelial cells express TLR1 to TLR5 as well as TLR9 proteins in an intracellular compartment18 and are sufficiently activated by a broad variety of TLR ligands released by pathogens and also by endogenous stimuli such as necrotic cells, heat-shock proteins and extracellular matrix breakdown products.19 The present study confirmed that both TLR2 and TLR4 are expressed in bronchial epithelial cells and showed for the first time an effect of CSE in increasing TLR4 but not TLR2 protein expression. The TLRs play a crucial role for the convergence of innate and adaptive responses; TLR4 activation mainly promotes T helper type 1 (Th1) responses20 while TLR2 activation mainly promotes Th2 responses.21 The selective increased expression of TLR4 caused by cigarette exposure in our study may represent an important mechanism by which a prevalent Th1 response, one of the typical features of COPD pathogenesis, may occur. This effect exerted by CSE is biologically relevant because we confirmed the increased TLR4 protein expression by both flow cytometry and Western blot analysis, excluding non-specific increase of autofluorescence of the cells, and because we showed that CSE did not induce cell apoptosis. Furthermore, flow cytometry analyses performed with permeabilized and non-permeabilized cells clarified that CSE not only promote an externalization of TLR4 but also increase the total TLR4 protein expression. To better understand whether the increased expression of TLR4 led to different functional effects, we first assessed whether CSE exposure affected the LPS binding by bronchial epithelial cells. Our results clearly demonstrated that when epithelial cells are exposed to CSE, they increase their ability to bind LPS. Furthermore, TLR4 on 16-HBE cells is functionally active because the exposure to LPS alone and in combination with CSE further increased the expression of TLR4. Both CSE and LPS were able to induce TLR4 protein without inducing TLR4 messenger RNA suggesting that the increased TLR4 protein expression may be achieved by a stabilization of the messenger RNA or by prolonged persistence of the protein.

The activation of TLRs activates downstream multiple intracellular signals so we first explored the effect on the NF-κB pathway. It has been shown that TLRs promote NF-κB activation by a classical pathway and by an alternative pathway.5 The classical pathway involves, following the activation of TLRs, the activation of MyD88 adaptor molecule, which in turn leads, via phosphorylation events, to the degradation of the inhibitor of NF-κB (I-κB). This phenomenon allows NF-κB translocation to the nucleus and its binding to DNA, so promoting the transcription of proinflammatory mediators. According to previous reports,22 both CSE and LPS activate the NF-κB pathway but the increased binding of LPS as a result of the presence of cigarette smoke does not lead to further activation of NF-κB. Other pathways in the absence of NF-κB activation may also sustain the proinflammatory activities generated by TLR4 activation. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that a splice variant of the MyD88 adaptor molecule, lacking a region that is important for interleukin receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK-4) recruitment, was not able to activate NF-κB but was still able to activate other signals (Jun N-terminal kinase; JNK).23 Moreover, a recent study using a microarray approach has demonstrated that nicotine induces IL-8 production in bronchial epithelial cells through ERK1/2 and JNK but not through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling.24 On the basis of these findings, we further investigated the intracellular events induced by TLR4 activation – exploring ERK1/2, JNK and p38 pathways. In our preliminary experiments the patterns of activation of p38 and of JNK upon stimulation with the different stimuli were not always the same (data not shown): ERK showed a constant pattern of activation (always the same response to the same stimulus) upon stimulation with CSE and LPS either alone or in combination in our experimental model. For this reason we decided to continue the study selecting ERK from among the MAPK.

According to previous reports,25 LPS induces ERK pathway activation while CSE, upon prolonged stimulation,11 is not able to activate the ERK pathway. Interestingly, when the cells were exposed to both CSE and LPS a significant activation of the ERK pathway was observed in the absence of a significant NF-κB activation, supporting the concept that CSE differentially regulate LPS-induced signalling. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that β-arrestin 2 positively regulates LPS-induced ERK1/2 activation and IL-8 production while negatively regulating LPS-induced NF-κB activation in fibroblasts.26 Further experiments are needed to assess whether CSE induce a differential regulation of LPS signalling via selective recruitment of β-arrestins. Taken together, all these findings suggest that a specific biological response, i.e. IL-8 production, may be achieved in particular experimental conditions (such as cigarette smoke exposure) through non-conventional or uncommon pathways.

Consequently, we explored whether the presence of CSE altered the proinflammatory profile of LPS-stimulated airway epithelial cells by assessing the release of IL-8 and IP-10. We selected these two mediators because, although they are both associated with chronic airway inflammation, their pathophysiological roles are different. Interleukin-8 is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils, and so triggers innate immunity responses, while IP-10 attracts monocytes and lymphocytes,9 so promoting activation of adaptive responses. In addition, IL-8 has been shown to be proangiogenic and profibrotic whereas IP-10 has angiostatic27 and antifibrotic properties.28 Here, we demonstrate that CSE increase both the release of IL-8 and the effect of LPS in the release of IL-8. These findings apparently contrast with those of a previous report,22 which demonstrated a down-regulatory effect of CSE in the LPS-induced release of IL-8. This discrepancy may be related to the different experimental models. In particular, the inhibition exerted by CSE on LPS-induced IL-8 production was present upon 15 min of CSE stimulation and upon 4 hr of stimulation with LPS, while in our model we stimulated the cells with both LPS and CSE for 18 hr.

Conversely, in our experimental model, when the bronchial epithelial cells were exposed to CSE, the constitutive and the LPS-induced release of IP-10 decreased. In this regard, IP-10 has been found to be increased in the bronchiolar epithelium of patients with COPD but not in the bronchiolar epithelium of smokers,29 suggesting that cigarette smoke alone is not sufficient to increase IP-10 expression. One possible explanation may be that CSE may reduce the release of IP-10, which would interfere with the activation of signals that are crucially involved in the expression of IP-10. In this regard it has been demonstrated that hyaluronan fragments activate two distinct molecular pathways to induce IL-8 and IP-10 in airway epithelial cells. Hyaluronan-induced IL-8 requires the MAPK pathway, whereas hyaluronan-induced IP-10 utilizes the NF-κB pathway.9 Although in numerous experimental models IL-8 production is dependent on NF-κB activation, we show that IL-8 release by 16-HBE cells is dependent on ERK1/2 activation while the IP-10 release is sustained by NF-κB activation because a specific inhibitor of ERK1/2 attenuates the IL-8 release while a specific inhibitor of NF-κB attenuates the IP-10 release.

The missing activation of NF-κB, together with conserved activation of the ERK1/2 pathway when 16-HBE cells are exposed to the combined presence of LPS and CSE, may contribute to the increased IL-8 release and to the reduced IP-10 release observed in this specific context.

The finding that CSE preferentially promote the release of IL-8 rather than the release of IP-10 prompted us to explore the effects in neutrophil and lymphocyte chemotaxis.

We demonstrate that CSE and LPS, alone or in combination, lead not only to an increased release of IL-8 but also to an increased chemotactic activity toward neutrophils. The chemotactic activity is related to the presence of biologically active IL-8 because an anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody significantly reduced the neutrophil chemotaxis. With regard to lymphocyte chemotaxis, the presence of CSE abrogates the chemotactic activity toward lymphocytes that is generated by LPS stimulation. Collectively these findings support the concept that the presence of CSE alters the normal activation of TLR4, which is physiologically finalized to generate balanced chemotactic activities toward neutrophils and lymphocytes, promoting preferential neutrophil recruitment.

Neutrophils are the front-line defensive cells of the immune system and are strongly involved in the pathogenesis of COPD. Smokers without COPD exhibit increased numbers of neutrophils within the airways and the number of neutrophils is increased in stable COPD patients and further increased during acute exacerbations.30 In this regard, it has been demonstrated that neutrophil elastase promotes the expression of mucin and the differentiation of epithelial cells into goblet cells, so promoting mucous metaplasia in chronic bronchitis. Furthermore, neutrophil elastase is actively involved in the protease/antiprotease imbalance, a phenomenon which leads to lung tissue destruction in emphysema.

In conclusion, the current study unveils new potential mechanisms by which cigarette smoke might contribute to the development of COPD. The CSE increase the expression of specific receptors of the innate immunity and modify the functional activation of these receptors, generating an imbalance between cytokines with opposite functions, such as IL-8 and IP-10. The prevalence of IL-8 may in turn sustain the influx of neutrophils into the airways while the reduced levels of IP-10 may compromise the influx of lymphocytes finalized to efficiently and specifically limit microbial invasion and to restrain the harmful effects of prolonged neutrophil activation. All these events may contribute to the generation of a negative feedback, inducing in the airway epithelial cells a proinflammatory functional phenotype that is a prelude to the perpetuation and to the amplification of inflammation and to the development/progression of COPD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Italian National Research Council, by GlaxoSmithKline and by PRIN-MIUR 2003062087.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CSE

cigarette smoke extract

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- IP-10

interferon-inducible protein 10

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

References

- 1.Sethi S, Murphy TF. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2000: a state-of-the-art review. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:336–63. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.336-363.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson R. Evidence of bacterial infection in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Semin Respir Infect. 2000;15:208–15. doi: 10.1053/srin.2000.18070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson R. Bacteria, antibiotics and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:995–1007. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.17509950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang G, Ghosh S. Molecular mechanisms of NF-κB activation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide through Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:453–7. doi: 10.1179/096805100101532414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imler JL, Hoffmann JA. Toll receptors in innate immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:304–11. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ. Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature. 2000;406:782–7. doi: 10.1038/35021228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sha Q, Truong-Tran AQ, Plitt JR, Beck LA, Schleimer RP. Activation of airway epithelial cells by toll-like receptor agonists. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:358–64. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0388OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton LM, Davies DE, Wilson SJ, Kimber I, Dearman RJ, Holgate ST. The bronchial epithelium in asthma – much more than a passive barrier. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2001;56:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boodoo S, Spannhake EW, Powell JD, Horton MR. Differential regulation of hyaluronan-induced IL-8 and IP-10 in airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L479–86. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00518.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su Y, Han W, Giraldo C, De Li Y, Block ER. Effect of cigarette smoke extract on nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:819–25. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.5.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luppi F, Aarbiou J, van Wetering S, Rahman I, de Boer WI, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. Effects of cigarette smoke condensate on proliferation and wound closure of bronchial epithelial cells in vitro: role of glutathione. Respir Res. 2005;6:140. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cozens AL, Yezzi MJ, Yamaya M, et al. A transformed human epithelial cell line that retains tight junctions post crisis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1992;28A:735–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02631062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pace E, Siena L, Ferraro M, et al. Role of prostaglandin E2 in the invasiveness, growth and protection of cancer cells in malignant pleuritis. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2382–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pace E, Profita M, Melis M, et al. LTB4 is present in exudative pleural effusions and contributes actively to neutrophil recruitment in the inflamed pleural space. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:519–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2003.02387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace E, Gjomarkaj M, Melis M, Profita M, Spatafora M, Vignola AM, Bonsignore G, Mody CH. Interleukin-8 induces lymphocyte chemotaxis into the pleural space. Role of pleural macrophages. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1592–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9806001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong L. Expression of functional toll-like receptor 2 and 4 on alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:241–5. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0078OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettersen CA, Adler KB. Airways inflammation and COPD: epithelial–neutrophil interactions. Chest. 2002;121:142S–50S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5_suppl.142s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hippenstiel S, Opitz B, Schmeck B, Suttorp N. Lung epithelium as a sentinel and effector system in pneumonia – molecular mechanisms of pathogen recognition and signal transduction. Respir Res. 2006;7:97. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beg AA. Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors: implications for regulating inflammatory and immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:509–12. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins SC, Jarnicki AG, Lavelle EC, Mills KH. TLR4 mediates vaccine-induced protective cellular immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of IL-17-producing T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:7980–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dillon S, Agrawal A, Van Dyke T, et al. A Toll-like receptor 2 ligand stimulates Th2 responses in vivo, via induction of extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:4733–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laan M, Bozinovski S, Anderson GP. Cigarette smoke inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced production of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing the activation of activator protein-1 in bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:4164–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns K, Janssens S, Brissoni B, Olivos N, Beyaert R, Tschopp J. Inhibition of interleukin 1 receptor/Toll-like receptor signaling through the alternatively spliced, short form of MyD88 is due to its failure to recruit IRAK-4. J Exp Med. 2003;197:263–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai JR, Chong IW, Chen CC, Lin SR, Sheu CC, Hwang JJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway was significantly activated in human bronchial epithelial cells by nicotine. DNA Cell Biol. 2006;25:312–22. doi: 10.1089/dna.2006.25.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddi K, Phagoo SB, Anderson KD, Warburton D. Burkholderia cepacia-induced IL-8 gene expression in an alveolar epithelial cell line: signaling through CD14 and mitogen-activated protein kinase. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:297–305. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000076661.85928.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan H, Luttrell LM, Tempel GE, Senn JJ, Halunshka PV, Cook JA. β Arrestin 1 and 2 differentially regulate LPS-induced signalling and pro-inflammatory gene expression. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:3092–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keane MP, Belperio JA, Arenberg DA, Burdick MD, Xu ZJ, Xue YY, Strieter RM. IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis via inhibition of angiogenesis. J Immunol. 1999;163:5686–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tager AM, Kradin RL, LaCamera P, et al. Inhibition of pulmonary fibrosis by the chemokine IP-10/CXCL10. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:395–404. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0175OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saetta M, Mariani M, Panina-Bordignon P, et al. Increased expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligand CXCL10 in peripheral airways of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1404–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’ Donnel R, Breen D, Wilson S, Djukanovic R. Inflammatory cells in COPD. Thorax. 2006;61:448–54. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.024463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]