Abstract

In the fifth article in his series, Tony Delamothe examines two important factors in judging the success of the UK health system: the satisfaction of its users and how it rates compares with other countries

The previous four articles in this series have dealt with how the founding principles of the NHS have fared over the past 60 years.1 2 3 4 I have judged them against the utopian aspirations of 1940s Britain for a national health service that was universal, equitable, comprehensive, high quality, centrally funded, and free at the point of delivery. Much of my attention has therefore been directed backwards and inwards.

In this article, I want to look outwards. Firstly, I want to capture what the British public thinks of the NHS today. And secondly, I want to see how the NHS compares with other healthcare systems that share many of the NHS’s underlying principles.

What does the UK think of the NHS?

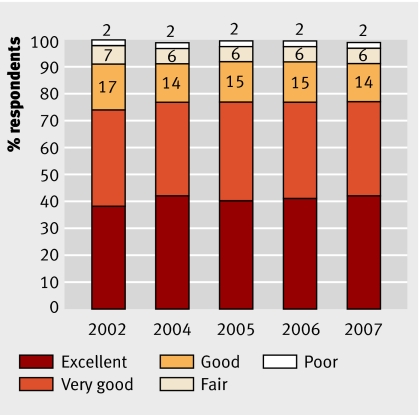

People seem happy with their NHS care, with more than 90% consistently rating their inpatient care as good, very good, or excellent (fig 1).5 In a 2006 survey for the Department of Health, 74% of those who attended a general practice or local healthcare centre were completely satisfied that their main reason for attending had been dealt with. Of the others, 22% were satisfied “to some extent” and only 4% were not satisfied at all.6

Fig 1 Adult patients’ ratings of inpatient care, England, 2002-75

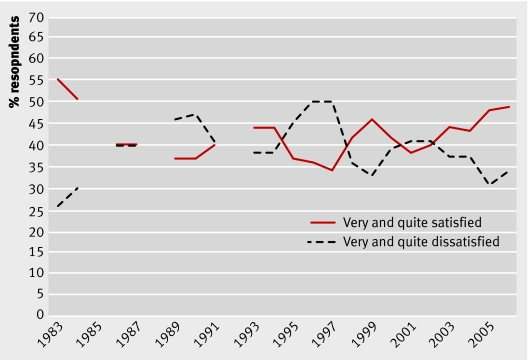

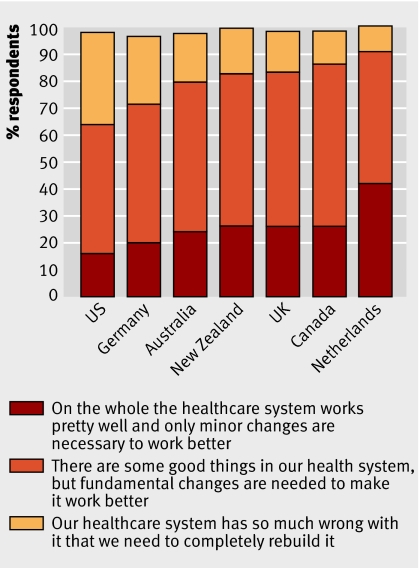

Although the general public tends to have a somewhat lower opinion of the NHS than patients with recent experience of NHS care, British Social Attitudes surveys show net satisfaction with the NHS is at its highest for 20 years (fig 2).7 Net satisfaction varies—between 62% for general practice and 27% for hospitals. Nevertheless, these proportions obscure a deep vein of dissatisfaction with the NHS. In 2007, the Commonwealth Fund found that 15% of the public agreed with the statement that “our healthcare system has so much wrong with it that we need to completely rebuild it” and 57% agreed that “there are some good things in our healthcare system but fundamental changes are needed to make it work better.”8

Fig 2 Satisfaction with “the way in which the NHS runs nowadays,” 1983-20067

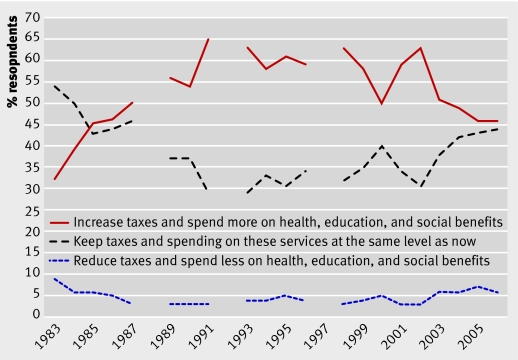

This appetite for radical reform doesn’t extend to overturning its funding base. Public support for a universal, tax funded NHS remains high. In 2006, 74% opposed the idea that the NHS should be available only to those on lower incomes, which would mean lower taxes and most people taking out private medical insurance. This proportion has remained at 71-78% since 1989.7 British Social Attitudes surveys have consistently shown that people rate health as their top priority for extra government spending. Every year since 1984 at least 70% have chosen it as their first or second priority.9

When presented with a forced choice between three options regarding taxes and social spending, fewer than 10% favour reducing taxes and government spending on health, education, and social benefits (fig 3).7 Social solidarity still trumps private interest when it comes to the public’s attitudes towards the NHS.10

Fig 3 UK public’s choice regarding taxation and social spending, 1983-20069

Comparison with other healthcare systems

Life expectancy and infant mortality are too blunt to be used to measure the performance of health systems, as many non-medical factors may affect them. Economic, demographic, social, and cultural factors may be just as relevant as medical factors to health outcomes.2 11 For example, smoking, lack of exercise, obesity, and alcohol may account for half the preventable years of life lost in the UK.12

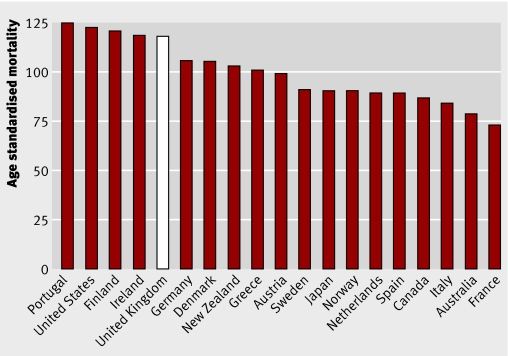

More sensitive measures have therefore been devised. A current favourite is mortality amenable to health care, defined as deaths that should not occur in the presence of timely and effective health care.13 In a recent survey of European countries, women in the UK had the third highest, and men the fifth highest, mortality from amenable causes (fig 4).14

Fig 4 Age standardised mortality in men (per 100 000) from causes amenable to health care, 2002-314

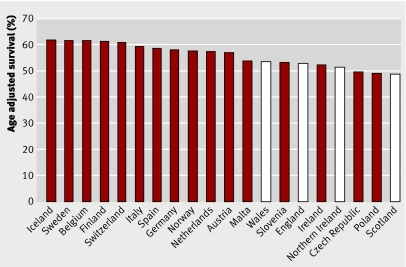

For cancer, survival rate is the preferred global index of the quality of care as it reflects speed and accuracy of diagnosis as well as timely access to effective treatment and clinical experts.15 In a recent study of age adjusted relative cancer survival in 21 European countries England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales came in the bottom third (fig 5).16

Fig 5 Age adjusted five year relative survival, all malignancies, women diagnosed 2000-216

There is a mini-industry in conducting comparative studies of healthcare systems, with the most controversial in recent memory being the one published by WHO in 2000. (It ranked the UK 18th in the world.17) Even if its multiple imperfections hadn’t ruled it out of consideration,18 its age would. Fortunately, there’s a more rigorous and recent comparison, produced by the Commonwealth Fund, a private US foundation with a mission to promote a high performing healthcare system.11 19

It grouped indicators of health processes and outcomes into five broad categories: long, healthy, and productive lives; quality; access; equity; and efficiency. The first four of these would have been instantly recognisable to Bevan as founding principles for the NHS. Based on data assembled by the Commonwealth Fund between 2004-6, the UK emerged in first place, ahead of Germany, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States (table).

Summary scores of health system performance in six countries, 2007*11

| Australia | Canada | Germany | New Zealand | UK | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy lives | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6 |

| Quality care | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 5 |

| Right care | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Safe care | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Coordinated care | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Patient centred care | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Access | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Efficiency | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Equity | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Overall ranking | 3.5 | 5 | 2 | 3.5 | 1 | 6 |

*1=highest ranking, 6=lowest ranking.

The UK was marked down on patient centred care, access (general practice opening hours and delays for tests and elective surgery), and healthy lives (mortality amenable to health care and healthy life expectancy at 60). The UK had moved up to first place from third place in two previous surveys partly reflecting its efforts “to implement a health information system that supports physicians’ efforts to provide quality health care and a payment system for primary care physicians that rewards high quality.” Some of the British government’s recent initiatives—targeting waiting lists and general practices’ opening hours—should bolster the UK’s ratings.

Despite the UK winning best in show this time around, not everyone is happy. But, as former banker Derek Wanless reminds us in his 2001 report to the UK Treasury, unhappiness with health systems remains a constant, regardless of the funding system and how much money is spent.12 In a comparative study in 2007 of public opinion on the extent of change required in their healthcare system, the UK fell in the middle of seven countries (fig 6).8

Fig 6 Public opinion on extent of change required by health systems, 20078

Unique spectacle

My rating of the NHS against its founding principles has shown a decidedly mixed picture. On a universal, centrally funded service, free at the point of delivery the NHS delivers according to plan, with the exception of (increasingly vestigial) patients’ charges.2 4 The government has achieved this by fudging the issue of what healthcare needs are covered by the NHS,3 not even (in England) mandating the implementation of decisions made by the agency it expressly set up to make these decisions (the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). What’s provided is far less than what 21st century consumers would deem comprehensive and is of widely varying quality. Along any axis you choose—whether geographic, socioeconomic, or age—the distribution of health care is inequitable. Some inequalities among health outcomes—for example, life expectancy and infant mortality—are actually increasing.3

And yet after meticulous comparison with the experience of similar countries, the United Kingdom emerges in first place. Who’s right and who’s wrong? Is this discrepancy somehow analogous to an outwardly successful person who nevertheless falls far short of his or her internal values. If so, what is the right response if these values still have credence?

There’s a second discrepancy evident in this attempt at an NHS scorecard: the gap between patients’ rating of the NHS and the public’s, with patients generally more positive. This raises the question of what influences people’s attitudes to an institution in the absence of direct experience of it. Pointing the finger at the media seems too easy, given that the media are often only the conduit by which strong opinions, of whatever complexion, are conveyed to the public. Writing of his time as minister of health in the early 1960s, Enoch Powell may have got nearer the truth: “One of the most striking features of the National Health Service is the continual, deafening chorus of complaint which rises day and night from every part of it, a chorus only interrupted when someone suggests that a different system altogether might be preferable, which would involve the money coming from some less (literally) palpable source. The universal Exchequer financing of the service endows everyone providing as well as using it with a vested interest in denigrating it, so that it presents what must be the unique spectacle of an undertaking that is run down by everyone engaged in it.”20

If things don’t seem quite that bad now, hardly a week goes by without the government, or one of an array of special interest groups, publicly criticising one or other aspect of the NHS, apparently motivated by the laudable aim of improving the service. Often there’s an ulterior motive that advances the critic’s agenda more than the public good. Nevertheless, patients and staff suffer collateral damage, and innocent bystanders assume there must be some substance to the criticisms because of the noise. But as long as people’s net satisfaction rating of their 274 million visits a year to primary care services is 62%, and 91% of 17 million hospital inpatients rate their care as excellent, very good, or good, it’s hard for the negativity to have much of an impact. For some, this resilience is frustrating.

Next week, in the final article of this series, I will be assessing the currents swirling around the NHS as it celebrates its 60th birthday, and what these could mean for its founding principles.

I have benefited greatly from discussions with John Appleby and Jon Ford.

Competing interests: None declared.

This is the fifth of six articles marking 60 years of the NHS

References

- 1.Delamothe T. Founding principles. BMJ 2008;336:1216-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delamothe T. Universality, equity, and quality of care. BMJ 2008;336:1278-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delamothe T. A comprehensive service. BMJ 2008;336:1344-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delamothe T. A centrally funded health service, free at the point of delivery. BMJ 2008;336:1410-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healthcare Commission. National survey of adult inpatients 2007 www.healthcarecommission.org.uk/healthcareproviders/nationalfindings/surveys/healthcareproviders/surveysofpatients/acutecare/surveyofadultinpatients2007.cfm

- 6.Department of Health. National survey of local health services 2006 London: DoH, 2007

- 7.British Social Attitudes Information System. www.britsocat.com

- 8.Commonwealth Fund. 2007 International health policy survey in seven countries. www.commonwealthfund.org/surveys/surveys_show.htm?doc_id=568326

- 9.Appleby A, Alvarez-Rosete A. Public responses to NHS reform. In Park A, Curtice J, Thomson K, Bromley C, Phillips M, Johnson M, eds. British social attitudes: two terms of new labour: the public’s reaction London: NCSR, 2005:109-33.

- 10.British Medical Association. A rational way forward for the NHS in England London: BMA, 2007

- 11.American College of Physicians. Achieving a high-performance health care system with universal access: what the United States can learn from other countries. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:55-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wanless D. Securing our future health: taking a long-term view (interim report). London: HM Treasury, 2001

- 13. Nolte E, McKee M. Measuring the health of nations: analysis of mortality amenable to health care. BMJ 2003;327:1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolte E, McKee CM. Measuring the health of nations: updating an earlier analysis. Health Affairs 2008;27:58-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leatherman S, Sutherland K. The quest for quality: refining the NHS reforms. London: Nuffield Trust, 2008

- 16.Verdecchia A, Francisci S, Brenner H, Gatta G, Micheli A, Mangone L, et al. Recent cancer survival in Europe: a 2000-02 period analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:784-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. World health report 2000. Health systems: improving performance Geneva: WHO, 2000

- 18.Davis K, Schoen C, Schoenbaum SC, Doty MM, Holmgren AL, Kriss JL, et al. Mirror, mirror on the wall: an international update on the comparative performance of American health care Commonwealth Fund, 2007. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publications_show.htm?doc_id=482678

- 19.Williams A. Science or marketing at WHO? A commentary on “World Health 2000.” Health Econ 2001;10:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Powell JE. A new look at medicine and politics London: Pitman, 1966:16.