Abstract

Chromosome segregation in mitosis is orchestrated by dynamic interaction between spindle microtubules and the kinetochore. Septin (SEPT) belongs to a conserved family of polymerizing GTPases localized to the metaphase spindle during mitosis. Previous study showed that SEPT2 depletion results in chromosome mis-segregation correlated with a loss of centromere-associated protein E (CENP-E) from the kinetochores of congressing chromosomes (1). However, it has remained elusive as to whether CENP-E physically interacts with SEPT and how this interaction orchestrates chromosome segregation in mitosis. Here we show that SEPT7 is required for a stable kinetochore localization of CENP-E in HeLa and MDCK cells. SEPT7 stabilizes the kinetochore association of CENP-E by directly interacting with its C-terminal domain. The region of SEPT7 binding to CENP-E was mapped to its C-terminal domain by glutathione S-transferase pull-down and yeast two-hybrid assays. Immunofluorescence study shows that SEPT7 filaments distribute along the mitotic spindle and terminate at the kinetochore marked by CENP-E. Remarkably, suppression of synthesis of SEPT7 by small interfering RNA abrogated the localization of CENP-E to the kinetochore and caused aberrant chromosome segregation. These mitotic defects and kinetochore localization of CENP-E can be successfully rescued by introducing exogenous GFP-SEPT7 into the SEPT7-depleted cells. These SEPT7-suppressed cells display reduced tension at kinetochores of bi-orientated chromosomes and activated mitotic spindle checkpoint marked by Mad2 and BubR1 labelings on these misaligned chromosomes. These findings reveal a key role for the SEPT7-CENP-E interaction in the distribution of CENP-E to the kinetochore and achieving chromosome alignment. We propose that SEPT7 forms a link between kinetochore distribution of CENP-E and the mitotic spindle checkpoint.

Chromosome movements during mitosis are governed by the interaction of spindle microtubules with a specialized chromosome domain located within the centromere. This specialized region, called the kinetochore (2), is the site for spindle microtubule-centromere association. In addition to providing a physical link between chromosomes and spindle microtubules, the kinetochore plays an active role in chromosomal segregation through microtubule motors and spindle checkpoint sensors located at or near it (3). During mitosis, attaching, positioning, and bi-orientating, kinetochores with the spindle microtubules play essential roles in chromosome segregation and genomic stability.

CENP-E3 is a microtubule-based kinesin motor protein located on the outer kinetochore and is involved in a stable microtubule-kinetochore attachment (4). CENP-E participates in the chromosome movements from prometaphase to anaphase (5) by tethering the kinetochores to microtubule “plus” ends and moving toward the equator (3, 6), thereby helping mono-oriented chromosomes align at the metaphase plate before bi-orientation (7). A recent study showed that the mammalian septin network cooperates with CENP-E and other effectors to coordinate cytokinesis with chromosome congression and segregation (1). However, whether CENP-E physically interacts with septin and how this interaction might be regulated have remained elusive.

Septins are conserved GTP-binding proteins first discovered in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where they organize into a ring at the bud neck (8). Subsequent genetic and cell biological analyses revealed that septins form a unique cytoskeletal substructure and exist ubiquitously in fungi, animals, and microsporidia but are absent from plants (9, 10). The number of septin proteins in a single organism ranges from two in Caenorhabditis elegans to fourteen in mammals (SEPT1–SEPT14) (11, 12). Analyses of their amino acid sequence similarity indicate that mammalian septins contain highly conserved polybasic and GTP-binding domains and can be classified into four groups (SEPT2, SEPT3, SEPT6, and SEPT7) (13, 14).

Septins purified from yeast, Drosophila, Xenopus, and mammalian cells form filaments with a diameter of 7–9 nm and of variable length (8, 15–18). SEPT7 is thought to be a unique and perhaps irreplaceable subunit that binds SEPT2 and SEPT6 subfamily members (14, 19). Recent cryo-electron microscopic analyses revealed a heterotrimeric human SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7 complex reconstituted in vitro (20). The structure of the SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7 complex exhibits a universal bipolar polymer building block, composed of an extended G domain, which forms oligomers and filaments by conserved interactions between adjacent nucleotide-binding sites and/or the N- and C-terminal extensions.

The requirement of SEPT2 for CENP-E localization to the kinetochore propelled our further investigation into the mechanistic insight underlying CENP-E regulation during mitotic chromosome segregation. Given our recent success in obtaining the full-length human CENP-E cDNA clone and the finding that the original CENP-E clone missed 38 amino acids (21, 22), we conducted a new search for proteins that interact with CENP-E using a yeast two-hybrid assay. This screen has identified SEPT7 as one of several dozen positive clones. Our biochemical studies confirmed that SEPT7 directly interacts with CENP-E via the C-terminal coiled-coil region. This SEPT7-CENP-E interaction is critical for a stable CENP-E localization to the kinetochore and for achieving chromosome alignment at the equator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast Two-hybrid Assay—Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed as previously described (22). Briefly, a CENP-E bait containing amino acids 2131–2701 was inserted into the BamHI-EcoRI sites of pGBKT7 individually to create a fusion with amino acids 1–147 of the Gal4 DNA-binding domain. The resultant pGBKT7/CENP-E C termini were transformed into strain AH109 along with the GAL4 reporter plasmid pCL and the negative control plasmid pGBKT7-Lam. Protein expression was validated by Western blotting using Gal4 and an anti-CENP-E antibody. Specificity of the interaction was independently verified by retransforming the candidate cDNAs back into AH109 along with BD-CENP-E2131–2701. Those cDNAs that can form colonies grown up from Leu-, Trp-, His-, Ade- SD plates were sequenced.

From the candidate positive clones, we selected SEPT7 to perform further research and inserted a series of SEPT7 deletion mutants into pGADT-7 vector. BD-CENP-E2131–2701, and these AD-SEPT7 deletion mutants were co-transformed into AH109 yeast strain to map out the interacting region of SEPT7 with CENP-E2131–2701.

Plasmid Construction and Mutagenesis—The full-length cDNAs of SEPT2/6/7 were obtained by reverse transcriptase-PCR from a HeLa cell library. The following plasmids were used for in vitro and in vivo studies: MBP-tagged full-length and deletion SEPT7 mutants (SEPT1–30, SEPT31–296, and SEPT244–418) were gifts from Dr. Koh-ichi Nagata; MBP-SEPT7297–418, MBP-SEPT2/6 full-length in pMal-C2 vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA); FLAG-SEPT2/6/7 full-length in 3×FLAG vector (Invitrogen); GFP-SEPT7 rescue plasmid and SEPT71–296 plasmid in pEGFP-C1 vector (Clontech), containing four silent mutations in the former four amino acids of the siRNA target sequence, which were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins—CENP-E2131–2701 or SEPT2, SEPT6, SEPT7 full-length and deletion mutants were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) as GST or MBP fusion with 0.3 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside at 30 °C for 3 h of induction and purified as previously described (22, 23).

Preparation and Characterization of Antibodies—MBP-tagged SEPT7244–418 protein was expressed and purified as antigens to immunize two Balb/c mice, according to standard protocol. Mouse polyclonal anti-SEPT7 antibody was generated and affinity-purified. To confirm the specificity of the purified antibody, it was preabsorbed by respective recombinant proteins used as antigen. Affinity-purified CENP-E rabbit antibody HpX was described previously (4).

In Vitro GST Pull-down Assay—In vitro pull-down assays were performed with bacterially expressed and purified GST-CENP-E2131–2701 and MBP-SEPT2/6 full-length and SEPT7 full-length and three deletion mutants. GST-CENP-E2131–2701 was used as an affinity matrix to absorb SEPT proteins in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with ice-cold in vitro binding buffer with 1% Triton X-100 added and once with PBS and then boiled for 5 min in Laemmli sample buffer. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE for Coomassie Blue staining or transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting using MBP antibody. Immunoreactive signals were detected with an ECL kit (Pierce) and visualized by autoradiography on Kodak BioMax film.

Co-immunoprecipitation—Mitotic HeLa cells were synchronized by double thymidine block. The cells were then extracted using lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EGTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml pepstatin A). The lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and then incubated with CENP-E polyclonal antibody HpX and SEPT7 polyclonal antibody bound-protein A/G beads at 4 °C for 4 h, respectively. After incubation, the beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and once with PBS. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for Western blotting. The membrane was probed with antibodies against CENP-E, SEPT7, and tubulin followed by ECL detection.

293T cells were transfected with GFP-CENP-E2131–2701 or pEGFP-C1 plus FLAG-SEPT2/6/7 plasmids individually. Thirty-six hours post-transfection, the cells were lysed, and clarified lysates were then incubated with FLAG-M2-agarose beads (Sigma) at 4 °C for 4 h. These beads were washed and boiled in sample buffer followed by fractionation on SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were then transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane and probed for GFP and FLAG, respectively.

Cell Culture and Synchronization—HeLa, MDCK, and 293T cells from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) were maintained as subconfluent monolayers in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 100 units/ml penicillin plus 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C with 10% CO2. The cells were synchronized at G1/S with 5 mm thymidine for 16 h, then washed with PBS three times, and cultured in thymidine-free medium for 12 h to release. After another round of thymidine treatment for 12 h, the cells were released for 9–10 h to enter prometaphase.

RNA Interference—For the siRNA studies, the 21-mer of siRNA duplexes for target GGUGAAUAUUGUGCCUGUCAU in SEPT2 transcripts, ACGACUACAUUGAUAGUAAAUU in SEPT7 transcripts and AAACACUUACUGCUCUCCAGUUU in CENP-E transcripts were synthesized from Dharmacon Research Inc. (Lafayette, CO). HeLa cells and MDCK cells were transfected with 21-mer siRNA oligonucleotides or a scramble control as recently described (22).

Immunofluorescence and Kinetochore Distance Measurement—Cells were transfected with siRNA and GFP-tagged plasmids in 24-well plate by Lipofectamine 2000. For immunofluorescence, HeLa or MDCK cells were seeded onto acid-treated 12-mm coverslips in 24-well plates (Corning, New York). Single thymidine-blocked and released cells were transfected with siRNA of SEPT2, SEPT7, or CENP-E and GFP fusion plasmids as described above. Fixation and staining were done as described (3). In some cases, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min prior to permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100. Antibodies against CENP-E (HpX and mAb154), SEPT7, Mad2, BubR1, and ACA were used at the dilution of 1:500, 1:200, 1:100, 1:250, and 1:500, respectively. The images were acquired using an Axiovert200 inverted Microscope (Carl Zeiss) with Axiovision 3.0 software. The distance between sister kinetochores marked with ACA was measured as described (3, 22).

Quantification of the level of kinetochore-associated protein was conducted as previously described by Johnson et al. (24) and recently reported by Liu et al. (22).

RESULTS

SEPT7 Is a Novel Binding Partner of CENP-E—Our previous studies demonstrate that CENP-E forms a link between attachment of spindle microtubules and the mitotic checkpoint signaling cascade (3). Our recent study revealed that CENP-E localization to the kinetochore is mediated by a Nuf2-CENP-E interaction (22). To further illustrate the molecular regulation of CENP-E in mitosis, the C-terminal tail of CENP-E (CENP-E2131–2701) was chosen as a bait to screen HeLa cDNA library using a GAL4 yeast two-hybrid system as previously described (25). Screening was performed on a total of 1 × 105 clones with 35 positive clones obtained. Following analysis by restriction digests of HaeIII and AluI, we obtained several novel interacting partners of CENP-E. Nucleotide sequencing revealed that one of these interacting partners encodes the C terminus of SEPT7 (amino acids 297–418). Its sequence matches human SEPT7 (accession number NM_001788).

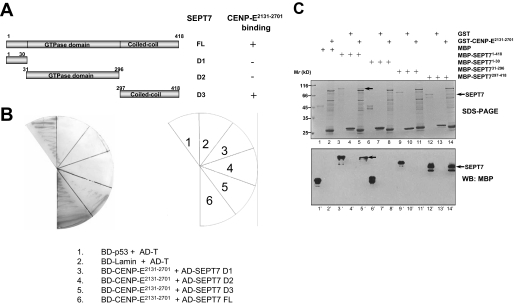

To verify the specificity of interaction between CENP-E and SEPT7 and further define the domain required for this interaction, we used reverse transcriptase-PCR to obtain the full-length cDNA of SEPT7 from HeLa cell library and cloned it into pGAD T7 vector. According to the structure analysis of SEPT7, three SEPT7 deletions were generated as illustrated in Fig. 1A. The SEPT7 full-length and deletion mutants were co-transformed with CENP-E2131–2701 into yeast cells using β-galactosidase activity (lacZ reporter) as a measure of protein-protein interaction. As summarized in Fig. 1B, human SEPT7 binds to CENP-E2131–2701 via its C-terminal coiled-coil region (SEPT7297–418). Thus, our yeast genetic assay suggests that human SEPT7 is a novel potential binding partner for CENP-E.

FIGURE 1.

Identification and characterization of a novel SEPT7-CENP-E interaction. A, schematic drawing shows SEPT7 and its fragments that encode various bait clones used for yeast two-hybrid assay for CENP-E binding activity. B, yeast cells were co-transformed with a CENP-E bait construct (CENP-E2131–2701) and the indicated prey constructs. An example of such an experiment in which cells were selected on supplemented minimal plates lacking uracil, tryptophan, leucine, and histidine is presented. C, reconstitution of CENP-E-SEPT7 interaction using recombinant proteins. GST-CENP-E2131–2701 purified on glutathione beads were used as an affinity matrix for absorbing MBP-tagged SEPT7 and its fragments as described under “Materials and Methods.” GST-agarose beads (GST) were used as control. After washing, proteins bound to agarose beads were boiled in sample buffer and fractionated on a SDS-PAGE gel (upper panel, Coomassie Blue-stained) and analyzed by Western blotting (WB, lower panel) using MBP antibody. An aliquot of purified MBP and MBP-tagged SEPT7 fusion proteins were loaded on an adjacent well as a positive control. Arrows (lanes 5 and 14) indicate SEPT7 proteins absorbed by CENP-E2131–2701 (upper panel). Immunoblotting with an anti-MBP antibody confirmed that full-length and C-terminal coiled-coil SEPT7 bind to CENP-E (lanes 5′ and 14′, arrows).

To validate the genetic interaction between CENP-E and SEPT7 seen in our yeast two-hybrid assay and test whether SEPT7 directly binds to CENP-E2131–2701 in vitro, we generated bacterially recombinant GST-CENP-E2131–2701, MBP-tagged fusion proteins of SEPT7 full-length and the deletion mutants as outlined in Fig. 1A. Aliquots of MBP-tagged fusion proteins of SEPT7 and its deletion mutants were incubated with agarose beads immobilized with GST-CENP-E2131–2701. As shown in Fig. 1C, immunoblotting using MBP antibody confirmed that the full length and C terminus coiled-coil region of SEPT7297–418 interact with GST-CENP-E2131–2701 (lanes 5 and 14, arrows). Neither the conserved N terminus (lane 8) nor the GTPase domain (lane 11) of SEPT was retained on the GST-CENP-E affinity matrix, confirming the selectivity of SEPT7-CENP-E interaction. Thus, we conclude that SEPT7 physically interacts with CENP-E via its C terminus tail.

SEPT7 Forms a Cognate Complex with CENP-E—To characterize the biochemical properties of SEPT7 protein and illustrate its subcellular distribution, we began by generating a mouse polyclonal anti-SEPT7 antibody purified from SEPT7 affinity matrix. Specific reactivity to SEPT7 was confirmed using cell lysates of MDCK cells transiently transfected to express various SEPT isoforms. As shown in Fig. 2A, the anti-SEPT7 antibody specifically recognized both endogenous and exogenous SEPT7 (lane 3) but not other septins. This selectivity was validated using cell lysates from other cell lines such as HeLa, U2OS, and 293 (data not shown). This reactivity was lost upon preincubation of the antibody with recombinant protein of SEPT7 (Fig. 2B, lane 2). Thus, the mouse SEPT7 antibody bears isoform-specific reactivity.

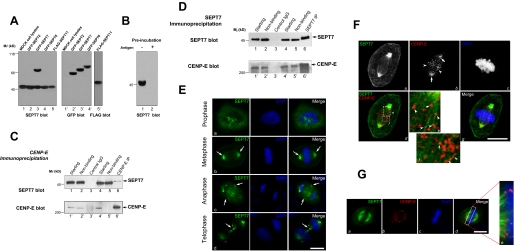

FIGURE 2.

SEPT7 interacts with CENP-E in vivo. A, characterization of a SEPT7-specific mouse antibody. Lysates from MDCK cells transiently expressing GFP-tagged SEPT2, SEPT6, SEPT7, and FLAG-SEPT11 were separated on a SDS-PAGE and then subjected to Western blotting using anti-SEPT7 antibody (left), GFP antibody, or FLAG antibody (right). B, validation of SEPT7 antibody. Preincubation of SEPT7 antibody with recombinant protein (+) failed to recognize SEPT7 in HeLa cell lysates. C, SEPT7 forms a cognate complex with CENP-E in vivo. Extracts from thymidine-synchronized mitotic HeLa cells were incubated with antibodies against CENP-E. Control immunoprecipitation was performed using a nonspecific rabbit IgG antibody from the same mitotic extract. Starting fractions, nonbinding fractions, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using CENP-E, SEPT7 antibody. Arrows indicate that SEPT7 (upper panel) and CENP-E (lower panel) were co-immunoprecipitated. D, CENP-E forms a cognate complex with SEPT7 in mitotic cells. Extracts from thymidine-synchronized mitotic HeLa cells were incubated with antibodies against SEPT7. Control immunoprecipitation was performed using a nonspecific rabbit IgG antibody from the same mitotic extract. Starting fractions, nonbinding fractions, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using CENP-E, SEPT7 antibody. Arrows indicate SEPT7 (upper panel) and CENP-E (lower panel) were co-immunoprecipitated. E, distribution of SEPT7 to mitotic apparatus in dividing cells. Fixed MDCK cells were stained with SEPT7 antibodies and DAPI. Note that SEPT7 appeared as filamentous structure from metaphase to telophase. The scale bar represents 10 μm. F, connection of SEPT7 filaments with CENP-E at the kinetochore. Fixed MDCK cells were stained with SEPT7 and CENP-E antibodies along with DAPI. Magnified view (inset) shows that CENP-E situates at the tip of SEPT7 filaments. The scale bar represents 10 μm. G, termination of SEPT7 filaments at the kinetochore marked by CENP-E. MDCK cells were pre-extracted before fixation, followed by triple labeling of SEPT7, CENP-E, and DAPI. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

To confirm the interaction between CENP-E and SEPT7 observed in our pull-down assay and test whether CENP-E forms a complex with SEPT7, we used anti-CENP-E antibody to immunoprecipitate soluble CENP-E and its potential partner proteins from lysates of mitotically arrested HeLa cells. Immunoblotting with anti-CENP-E antibody confirmed a successful precipitation of CENP-E, and immunoblotting against SEPT7 demonstrated that SEPT7 was co-precipitated with CENP-E (Fig. 2C, lane 6). Neither CENP-E nor SEPT7 was precipitated with control IgG (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 3′), and no tubulin was detected in any of the immunoprecipitates (data not shown). Reciprocal precipitation with an anti-SEPT7 mouse antibody confirmed the presence of a complex of SEPT7 and CENP-E in the precipitate (Fig. 2D, lanes 6 and 6′). Neither CENP-E nor SEPT7 was precipitated with control IgG (Fig. 2D, lanes 3 and 3′). Thus, we conclude that SEPT7 and CENP-E can form a complex in vivo.

SEPT7 Co-distributes with CENP-E to the Kinetochore of Mitotic Cells—A recent report claimed that SEPT2 and SEPT6 distribute along the mitotic spindle in metaphase MDCK and HeLa cells (1). Because biochemical studies demonstrate a stable SEPT2/6/7 complex, we carried out an immunofluorescence study to ascertain the subcellular localization of SEPT7 in mitotic cells. As shown in Fig. 2E, SEPT7 is distributed mainly in the cytoplasm of prometaphase cell (row a), and becomes organized into spindle appearance in metaphase cells (row b, arrows). There was minor deposition of SEPT7 along the plasma membrane in metaphase cells. In anaphase cells, whereas SEPT7 remained associated with the mitotic spindle, a majority relocated to central spindle with dramatic concentration to cleavage furrow (row c, arrows). SEPT7 remained associated with the midbody in telophase cells (row d, arrows). From metaphase to telophase, SEPT7 distribution is reminiscent of microtubules.

Our ultrastructural study demonstrated that CENP-E is a constituent of the corona fibers and intertwines with spindle microtubules (4). The biochemical interaction between SEPT7 and CENP-E together with SEPT7 distribution propelled us to evaluate their spatial relationship in dividing cells. To this end, fixed and permeabilized MDCK cells were doubly stained with an anti-SEPT7 mouse antibody and an anti-CENP-E rabbit antibody. As shown in Fig. 2F, SEPT7 distributes along the spindle with a heavy deposit at the poles. In addition, SEPT7 staining was also apparent near the plasma membrane, consistent with the fact that SEPT7 also interacts with actin filaments. Examination of CENP-E labeling in the same cells revealed that a typical kinetochore localization in addition to a minor spindle pole deposition (Fig. 2F, panel b, arrows). Higher magnification of the merged image revealed that CENP-E distributes along the SEPT7 filaments (Fig. 2F, panel e, arrowheads). Careful examination of enlarged image suggests that some SEPT7 filaments appear to terminate at the kinetochore marked by CENP-E (Fig. 2F, panels d and f, arrows).

To examine whether any SEPT7 filaments terminate at the kinetochore marked by CENP-E, we carried out immunofluorescence labeling of pre-extracted cells in which cytoplasmic SEPT7 and spindle pole-associated CENP-E were removed by the pre-extraction protocol, whereas the ultrastructure of spindle apparatus is intact (4). As shown in Fig. 2G, SEPT7 distributes along the spindle with CENP-E marked at its end (panel d). Higher magnification views (boxed area) revealed that CENP-E, marked in red, is readily apparent adjacent to the tip of SEPT7 filaments intertwining with kinetochore (magnified view; panel e). Thus, we conclude that CENP-E distributes along SEPT7 filaments on the mitotic spindle and at the kinetochore.

SEPT7 Forms a Link between SEPT Filaments and CENP-E—Recent studies show that human septins, SEPT2, SEPT6, and SEPT7, can exist in both rod-like monomers and dimers as well as polymerized filaments comprising of laterally arranged septin core subunits SEPT2/6/7 (26). If CENP-E binds to SEPT7 in a polymeric form, immunoprecipitation of SEPT7 would bring down other septin isoforms in addition to CENP-E. To validate this hypothesis, we used anti-FLAG antibody to immunoprecipitate FLAG-tagged septins and GFP-tagged CENP-E from mitotic lysates of 293T cells transiently transfected to express GFP-tagged CENP-E2131–2701 and FLAG-tagged SEPT2, SEPT6, SEPT7, and SEPT11, respectively. Immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody confirmed a successful precipitation of SEPT2, SEPT6, and SEPT7, and immunoblotting against GFP demonstrated that GFP-CENP-E2131–2701 was co-precipitated (Fig. 3A, lanes 5′–7′). However, CENP-E was never recovered in anti-SEPT11 immunoprecipitates, indicating the specificity of the CENP-E-SEPT7 interaction (Fig. 3A, lane 8′).

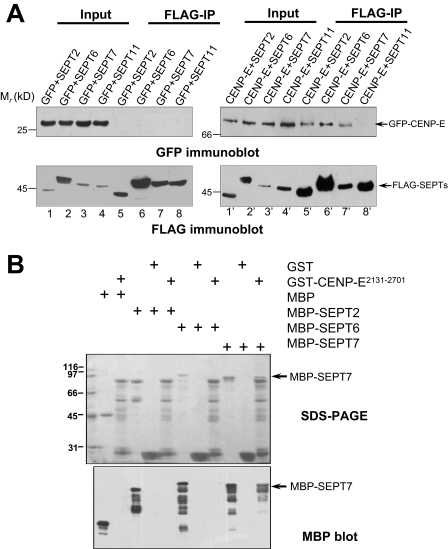

FIGURE 3.

CENP-E interacts with SEPT2/6/7 complex by a direct contact with SEPT7. A, co-immunoprecipitation of CENP-E2131–2701 and SEPT2/6/7/11 from transfected 293T cells. 293T cells co-transfected with GFP-CENP-E2131–2701 (CENP-E) and FLAG-SEPT2/6/7 or 11 were extracted and subjected to immunoprecipitations using monoclonal antibody to FLAG (right). Control immunoprecipitations were performed using cell lysates from pEGFP-C1 (GFP) and FLAG-tagged SEPT2/6/7 or 11 co-transfected 293T cells (left). Immunoprecipitation were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using FLAG antibody and GFP antibody, respectively. B, GST-CENP-E2131–2701 purified on glutathione beads were used as affinity matrix for absorbing MBP-tagged SEPT2/6/7; GST-agarose beads were used as control. After washing, the proteins bound to agarose beads were boiled in sample buffer and fractionated on SDS-PAGE gel (upper panel, Coomassie Blue-stained) and analyzed by Western blotting (lower panel) using an anti-MBP antibody. Arrows indicate SEPT7 absorbed by CENP-E2131–2701 affinity matrix.

Recent structural biological studies show that SEPT2/6/7 forms hexameric filaments, and neighboring hexamers make longitudinal contact via SEPT7 (20). If the SEPT7-CENP-E interaction forms the link between SEPT filaments and CENP-E, other SEPT isoforms such as SEPT6 and SEPT2 would not need to have a direct contact with CENP-E. To test this hypothesis, we did a GST pull-down assay to confirm the direct interaction among this complex. As shown in Fig. 3B, both the SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analyses show that only SEPT7 but not SEPT2 and SEPT6 physically interacts with GST-CENP-E2131–2701. Thus, we conclude that a direct SEPT7-CENP-E interaction may link SEPT2/6/7 filaments to CENP-E at the kinetochore.

SEPT2/6/7 Complex Is Essential for a Stable Kinetochore Localization of CENP-E—It has been reported that SEPT2 depletion results in disrupted kinetochore localization of CENP-E and aberrant mitotic progression (1). Because SEPT2/6/7 form filaments in hexameric repeats (20), depletion of SEPT7 could result in disruption of SEPT2/6/7 hexamers and aberrant distribution of CENP-E. To assess the functional role of SEPT7 in mitosis, we introduced siRNA oligonucleotide duplexes to SEPT7 by transfection into MDCK and HeLa cells, respectively. Trial experiments revealed that treatment of HeLa cells and MDCK cells with 100 nm siRNA for 24–48 h produced optimal suppression of the target proteins. As shown in Fig. 4A, Western blotting with anti-SEPT7 antibody revealed that the siRNA oligonucleotide caused optimal suppression of SEPT7 protein levels at 48 h.

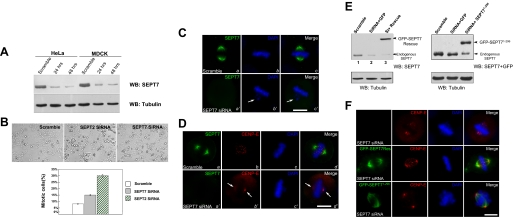

FIGURE 4.

Depletion of SEPT7 destabilized CENP-E localization to the kinetochore and resulted in chromosomes misalignment. A, efficiency of siRNA on suppression of SEPT7. HeLa cells and MDCK cells were transfected with 100 nm SEPT7 siRNA for optimal suppression of target protein different intervals and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. Upper panel, immunoblot against SEPT7; Lower panel, immunoblot againstα-tubulin. A scramble oligonucleotide was used as a control. WB, Western blotting. B, phase contrast images of control cells, and cells treated with SEPT2 siRNA and SEPT7 siRNA (upper panels). Mitotic cells were defined by the absence of a nuclear envelope and the presence of condensed chromosomes. Mitotic index is expressed as the percentage of the total cell population that in mitosis at the 48 h after the transfection. An average of 200 cells from three separate experiments was surveyed to obtain the mitotic index. The error bars represent S.E. (n = 3 preparations). C, repression of SEPT7 by siRNA resulted in chromosome misalignment. MDCK cells were transfected with SEPT7 siRNA oligonucleotide (SEPT7 siRNA) and scramble control (Scramble) for 48 h followed by fixation and DNA staining. The cells were then examined under a fluorescence microscope to sort out the phenotypes. Arrows indicates misaligned chromosomes caused by SEPT7 depletion (panels b′ and c′). The scale bar represents 10 μm. D, repression of SEPT7 resulted in loss of kinetochore-associated CENP-E. Immunofluorescence assay of MDCK cells transfected with control siRNA (Scramble) or SEPT7 siRNA (SEPT7 siRNA). Forty-eight hours after the transfection, these cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for SEPT7, CENP-E, and DNA (DAPI). Arrows indicate relocation of CENP-E from kinetochore to spindle poles caused by SEPT7 depletion (panels b′ and d′). The scale bar represents 10 μm. E, efficiency of restoration of SEPT7 in siRNA-treated cells. HeLa cells were transfected with 100 nm SEPT7 siRNA. Twelve hours later, the cells were transfected with pEGFP-C1 or GFP-SEPT7 rescue plasmid (rescue) or GFP-SEPT71–296 (lacked CENP-E binding region). Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, GFP-C1 or GFP-SEPT7 rescue plasmid transfected cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with SEPT7 antibody. F, expression of siRNA-resistant SEPT7 restored CENP-E localization to kinetochore in the absence of endogenous SEPT7. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids and siRNA as in E. Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, the cells were fixed and stained with an anti-GFP and CENP-E antibodies in addition to nuclear dye DAPI. Note that the kinetochore localization of CENP-E in HeLa cells transiently transfected to express siRNA-resistant SEPT7 (central panels) but not CENP-E-binding deficiency SEPT7 (bottom panels). The scale bar represents 10 μm.

Because SEPT2, SEPT6, and SEPT7 form a stable complex and repression of SEPT2 results in chromosome misalignment, we examined whether suppression of SEPT7 also exhibits any aberrant mitotic phenotypes. As shown in Fig. 4B, suppression of SEPT2 and SEPT7 resulted in an accumulation of mitotic cells (viewed as a rounded conformation), consistent with the previous assessment on SEPT2 (1). The mitotic index in SEPT2-depleted and SEPT7 siRNA-treated cells was dramatically increased at 48 h after the transfection (30 ± 3% for SEPT2 siRNA; 16 ± 2% for SEPT7 siRNA), compared with that of scramble control (7 ± 1%). The reduction in total SEPT7 content was also reflected in loss of SEPT7 at the mitotic spindle, as demonstrated by indirect immunofluorescence with antibody against SEPT7 (Fig. 4C, panel a′). Examination of chromosome configuration revealed that a loss of SEPT7 results in chromosome segregation defects, because many SEPT7-repressed cells contain misaligned chromosomes (Fig. 4C, panel b′, arrow).

Because SEPT2 and SEPT7 form a stable and evolutionarily conserved polymeric filamentous complex, we next examined the effect of repressing SEPT7 on the localization of CENP-E to the kinetochore. In control cultures, the tip of SEPT7 filaments localized with CENP-E at the kinetochores (Fig. 4D, Scramble panels). In cells in which SEPT7 had been suppressed, the levels of kinetochore-bound CENP-E appeared reduced (Fig. 4D, SPET7 siRNA panels). Instead, the CENP-E labeling was mainly visualized at the spindle poles (Fig. 4D, SPET7 siRNA panels, arrows). Quantitation of normalized pixel intensities showed that, when SEPT7 was reduced to <10% of its control value, CENP-E levels were reduced to ∼39%, indicating that SEPT7 is required for a stable kinetochore localization of CENP-E.

Ectopic Expression of siRNA-resistant SEPT7 Restored the CENP-E Association with the Kinetochore and Chromosome Congression in SEPT7-depleted Cells—If SEPT7 is a determinant for CENP-E localization to the kinetochore, expression of siRNA-resistant SEPT7, in the absence of endogenous SEPT7 should retain the association of CENP-E with the kinetochore. To this end, HeLa cells were transfected with SEPT7 siRNA, followed by a second transfection of GFP, GFP-tagged siRNA-resistant full-length SEPT7, and GFP-SEPT71–296 after 12 h. As shown in Fig. 4E, endogenous SEPT7 protein level was reduced by SEPT7 siRNA to ∼10% of the control (Fig. 4E, arrow). However, the protein levels of exogenous SEPT7 (both full-length and CENP-E-binding-deficient mutant SEPT71–296) were fully restored (Fig. 4E, arrowhead).

Significantly, only expression of siRNA-resistant full-length SEPT7, but not the CENP-E-binding deficient SEPT71–296 mutant, restored CENP-E localization to the kinetochore and corrected the chromosome misalignment defects (Fig. 4F). Thus, we concluded that SEPT7 is required for a stable kinetochore localization of CENP-E and chromosome congression in mitosis.

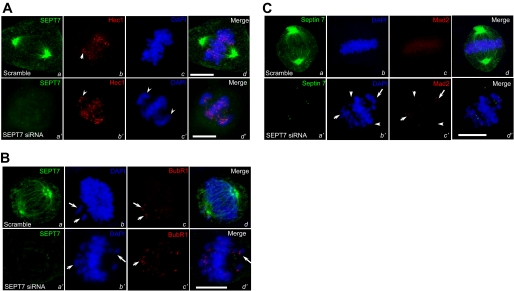

Suppression of SEPT7 Does Not Alter the Assembly of Ndc80 Complex to the Kinetochore but Activates Spindle Checkpoint—Kinetochore assembly is orchestrated in a spatio-temporal fashion during the cell division cycle (27). Our recent study demonstrated that Ndc80 complex specifies the assembly of CENP-E to the kinetochore via a direct Nuf2-CENP-E interaction (22). To examine whether suppression of SEPT7 alters kinetochore assembly of Ndc80 complex, we carried out immunofluorescence staining of Hec1 and SEPT7 in siRNA-treated MDCK cells. In control scramble siRNA-treated sample (Fig. 5A, panels a–d), SEPT7 distributes along the spindle with a heavy deposit at the poles in addition to deposit to the plasma membrane. Although suppression of SEPT7 prevented chromosome alignment at the equator as evidence by the misaligned chromosome (Fig. 5A, panel c′, arrowheads), the distribution of Hec1 to kinetochore was not altered (Fig. 5A, panel b′, arrowheads). Therefore, we conclude that SEPT7 is not essential for localization of Ndc80 complex to the kinetochore.

FIGURE 5.

Repression of SEPT7 activates spindle assembly checkpoint. A, repression of SEPT7 altered the kinetochore localization of Hec1. MDCK cells were transfected with SEPT7 siRNA oligonucleotide (SEPT7 siRNA) and scramble control (Scramble). 48 h after the transfection, these cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for SEPT7, Hec1, and DNA (DAPI). The scale bar represents 10 μm. B, suppression of SEPT7 resulted in deposition of BubR1 labeling on the misaligned chromosomes. MDCK cells were transfected with SEPT7 siRNA oligonucleotide (SEPT7 siRNA) and scramble control (Scramble). 48 h after the transfection, these cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for SEPT7, BubR1, and DNA (DAPI). The scale bar represents 10 μm. C, suppression of SEPT7 resulted in retention of Mad2 labeling on the misaligned chromosomes. MDCK cells were transfected with SEPT7 siRNA oligonucleotide (SEPT7 siRNA) and scramble control (Scramble). After 48 h transfection, SEPT7-repressed cells were followed by fixation and were stained for SEPT7, Mad2, and DNA (DAPI). The scale bar represents 10 μm.

BubR1 is a spindle assembly checkpoint component interacting with CENP-E (3). To examine whether suppression of SEPT7 alters kinetochore localization of BubR1, we carried out immunofluorescence staining of BubR1 and SEPT7 in siRNA-treated MDCK cells. In control scramble siRNA-treated sample (Fig. 5B, panels a--d), BubR1 marks the kinetochore of lagging chromosomes as a checkpoint sensor (Fig. 5B, panel c, arrows). Although suppression of SEPT7 prevented chromosome alignment at the equator as evidenced by the misaligned chromosome (Fig. 5A, panel c′, arrowheads), in contrast to that of Hec1, the distribution of BubR1 was only apparent to the kinetochores of lagging chromosome (Fig. 5B, panel b′, arrows), suggesting the possibility of spindle assembly checkpoint activation in the absence of SEPT7.

The fact that repression of SEPT7 reduced CENP-E localization to the kinetochore and resulted in deposition of BubR1 labeling in the misaligned chromosome propelled us to assess whether the spindle assembly checkpoint is activated in SEPT7-repressed cells. Early studies have established the faithfulness of Mad2 labeling at the kinetochore as an accurate reporter of spindle checkpoint activation (3). Consistent with our previous observations, a high level of Mad2 labeling was observed on the misaligned chromosomes (Fig. 5C, panel c′, arrows) but not on chromosomes near the spindle equator (Fig. 5C, panel c′, arrowheads). As expected, the kinetochores of aligned chromosomes of control metaphase cells exhibit no apparent Mad2 labeling (Fig. 5C, panel c). The higher level of Mad2 labeling in the kinetochores of lagging chromosomes in SEPT7-repressed cells indicate that association of CENP-E with kinetochore in prometaphase cells is necessary for silencing spindle-checkpoint signaling from misaligned chromosomes.

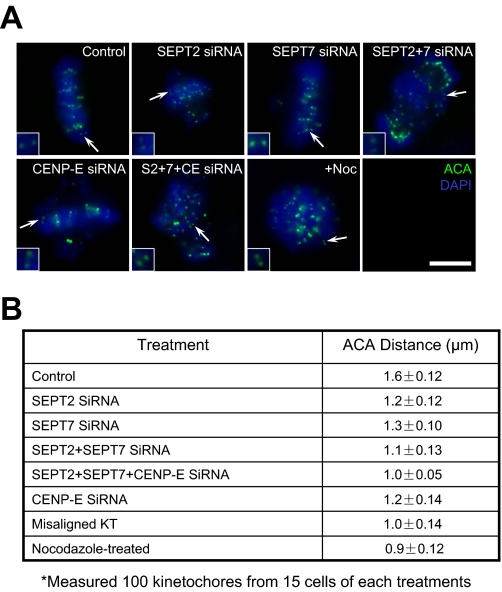

SEPT2/6/7 Complex Collaborates with CENP-E to Stabilize Kinetochore-Microtubule Attachment—Previous studies established that CENP-E is essential for stabilizing kinetochore-microtubule attachments (3, 22), and elimination of SEPT2 liberates CENP-E association with the kinetochore (1). Our finding that the SEPT2/6/7 complex was required for CENP-E maintenance at metaphase kinetochores propelled us to test whether depletion of septin could affect the functional activity of microtubule capturing. The distance between sister kinetochores marked by ACA has been used as an accurate reporter for judging the tension developed across the kinetochore pair (3, 21). In this case, the shortened distance often reflects aberrant microtubule attachment to the kinetochore, in which less tension is developed across the sister kinetochore. Therefore, we measured ACA distance in >100 kinetochore pairs in which both kinetochores were in the same focal plane, in each siRNA-treated cells including SEPT2, SEPT7, CENP-E, SEPT2+SEPT7, SEPT2+SEPT7+CENP-E, and control cells. Nocodazole-treated cells were used as a negative control in which kinetochore pairs were presumably under no tension.

As shown in Fig. 6A, depletion of SEPT2, SEPT7, CENP-E, SEPT2+SEPT7, or SEPT2+SEPT7+CENP-E resulted in errors in chromosome alignment at the equator. Control kinetochores exhibited a separation of 1.6 ± 0.12 μm, whereas the distance between kinetochores was 1.2 ± 0.12 μm in SEPT2-depleted cells, 1.3 ± 0.10 μm in SEPT7-depleted cells, 1.1 ± 0.13 μm in cells depleted both SEPT2 and SEPT7, and 1.2 ± 0.14 μm in CENP-E-depleted cells. Simultaneous depletion of SEPT2, SEPT7, and CENP-E did result in dramatic shortening of the inter-kinetochore distance (1.0 ± 0.05 μm), comparable with 0.9 ± 0.12 μm in nocodazole-treated cells, indicating that CENP-E interacts synergistically with the SEPT2/6/7 complex in stabilizing microtubule-kinetochore association. Thus, we conclude that CENP-E collaborates with the SEPT2/6/7 complex in stabilizing the kinetochore-microtubule attachment.

FIGURE 6.

Depletion of SEPT2/7 releases the tension across sister kinetochores. A, immunofluorescence assay of control siRNA-treated HeLa cells (scramble), SEPT2 siRNA-treated cells, SEPT7 siRNA-treated cells, CENP-E siRNA-treated cells, SEPT2 and SEPT7 siRNA-treated cells, SEPT2 and SEPT7 and CENP-E siRNA (SEPT2 + 7+CE siRNA) and nocodazole-treated (Noc) cells. After 48 h transfection, the cells were fixed and stained for ACA (green) and DNA (blue). The scale bar represents 10 μm. B, statistic analyses of ACA distance in the aforementioned siRNA-treated cells. Basic principle of measuring the ACA double-dot distance is to choose those couples whose ACA spots have almost similar fluorescence intensity, which indicates the ACA couple localize at the same focal plane. Each value was calculated from over 100 kinetochores selected from at least 15 different cells.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that SEPT7 physically interacts with CENP-E and is essential for a stable association of CENP-E with kinetochores. The failure of stable bipolar attachment strongly indicates that septin filaments function in one or more steps of the centromere-microtubule interaction, including initial capture and spindle microtubule stabilization or formation of matured attachments. This reinforces and extends previous observations of CENP-E function in mitotic chromosome movements and the mitotic checkpoint in mammalian cells (3, 28, 29).

Previous studies indicated that some chromosomes fail to align properly at the metaphase plate after SEPT2 depletion, corresponding with the loss of proper kinetochore localization of CENP-E (1). This suggests that mammalian SEPT isoforms might form a novel scaffold at the midplane of the mitotic spindle that coordinates several key steps in mammalian mitosis. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying SEPT-CENP-E interaction and the functional relevance have remained elusive. X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopic analyses of human SEPT complex consisting of SEPT2-SEPT6-SEPT7 just became available during the course of this study (20). It was shown that the predicted coiled-coils of SEPT7 are not involved in or required for complex and/or filament formation. The asymmetrical heterotrimers associate head-to-head to form a hexameric unit that is nonpolarized along the filament axis. In this model, the neighboring hexamer makes longitudinal contact using SEPT7. Because the coiled-coil of SEPT7 is involved in its binding with CENP-E, the SEPT7-CENP-E interaction may provide a link between microtubule lattices and SEPT filaments. In this case, the function of septin filaments may serve as a “safety thread” to ensure the plus-end directed translocation of CENP-E molecules. We had attempted to address the specificity of SEPT7-CENP-E interaction by overexpressing CENP-E-binding domain of SEPT7 in MDCK cells. Although the deletion mutant of SEPT7 was expressed and localized to the spindle, the mutant failed to result in any phenotypic changes.4 It is likely that mutant SEPT7 is not as sufficient as the full-length SEPT7 to assemble into filaments to absorb CENP-E and subsequently exhibit a “dominant negative” effect.

Given the fact that suppression of SEPT7 prevents CENP-E distribution to the kinetochore but accumulation at the spindle poles, we propose that septin filaments may act as a scaffold to ensure a faithful translocation of CENP-E on the microtubule to the kinetochore. To this end, it would be necessary to develop an in vitro reconstitution system in which CENP-E motility can be assessed in the presence of septin filaments. Our study shown here aims to provide an outline so further mechanistic studies of septin-CENP-E-microtubule interaction can be pursued. In addition, it would be of great interest to study how septin filament dynamics is regulated to facilitate microtubule-based motility using this in vitro system.

Recently, an elegant study revealed that Xenopus CENP-E kinesin motility is regulated by Mps1/TTK-mediated phosphorylation, which releases the auto-inhibition exerted by the N/C interaction of the CENP-E molecule (30). Given the interaction between CENP-E and Mps1/TTK and the essential role of TTK/Mps1 kinase activity for CENP-E distribution to the kinetochore (31, 32), it is tempting to speculate that TTK/Mps1 phosphorylates CENP-E and triggers its plus-end-directed kinesin motility essential for its translocation to the kinetochore in mitosis. This speculation becomes even more plausible given the fact that a decrease of ATP level is correlated to the departure of CENP-E from the kinetochore to the pole (33).

It has been reported that the interaction between CENP-E and BubR1 might activate BubR1 kinase activity, which is important to activate the spindle checkpoint (29). The interaction of CENP-E localized at the kinetochore with microtubule will silence BubR1 signaling (28). The deficiency of CENP-E, caused by the suppression of SEPT7, at the kinetochore is insufficient to satisfy the spindle checkpoint, which results in a mitotic arrest seen in our experimentation (Fig. 4B). The preferential labeling of checkpoint proteins MAD2 and BubR1 at the kinetochore of the misaligned chromosome supports the notion of spindle checkpoint activation in the SEPT7-suppressed cells.

Loss or gain of whole chromosomes, the form of chromosomal instability most commonly associated with human cancers, is expected to arise from the failure to accurately segregate chromosomes in mitosis. Septin abnormalities have been found in human tumor cells (11). Disruption of septin function in different stages of mitosis could potentially lead to chromosome instability and changes in ploidy common to cancers. Recent studies show that cells and mice with reduced levels of CENP-E developed aneuploidy and chromosomal instability in vitro and in vivo. Given the finding that chromosomal instability both drives tumorigenesis and inhibits tumorigenesis depending on the level of genomic damage that is induced, it would be necessary to illustrate whether septin abnormality promotes tumorigenesis in animals bearing chromosomal instability.

In sum, we established an interrelationship between the SEPT2/6/7 complex and CENP-E in the orchestration of spindle plasticity and mitotic progression. We propose that the SEPT2/6/7 complex forms a link between the kinetochore distribution of CENP-E and the mitotic checkpoint via a direct SEPT7-CENP-E contact. Because CENP-E is absent from yeast, we reason that metazoans evolved an elaborate spindle checkpoint machinery to ensure faithful chromosome segregation in mitosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Koh-ichi Nagata for reagents and members of our groups for insightful discussion during the course of this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-56292, CA89019, and CA92080 (to X. Y.). This work was also supported by Chinese Project 973 Grants 2002CB713700, 2006CB943600, and 2007CB914503; Chinese Academy of Science Grants KSCX1-YW-R65 and KSCX2-YW-H-10; and Chinese Natural Science Foundation Grants 39925018, 30500183, 30121001, and 90508002 (to X. Y.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: CENP-E, centromere-associated protein E; GST, glutathione S-transferase; ACA, anti-centromere antibodies; SEPT, septin; siRNA, small interfering RNA; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MDCK, Madin-Darby canine kidney; MBP, maltose-binding protein; DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

M. Zhu and X. Yao, unpublished observations.

References

- 1.Spiliotis, E. T., Kinoshita, M., and Nelson, W. J. (2005) Science 307 1781-1785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleveland, D. W., Mao, Y., and Sullivan, K. F. (2003) Cell 112 407-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao, X., Abrieu, A., Zheng, Y., Sullivan, K. F., and Cleveland, D. W. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2 484-491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao, X., Anderson, K. L., and Cleveland, D. W. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 139 435-447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yen, T. J., Compton, D. A., Wise, D., Zinkowski, R. P., Brinkley, B. R., Earnshaw, W. C., and Cleveland, D. W. (1991) EMBO J. 10 1245-1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood, K. W., Sakowicz, R., Goldstein, L. S., and Cleveland, D. W. (1997) Cell 91 357-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor, T. M., Lampson, M. A., Hergert, P., Cameron, L., Cimini, D., Salmon, E. D., McEwen, B. F., and Khodjakov, A. (2006) Science 311 388-391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byers, B., and Goetsch, L. (1976) J. Cell Biol. 69 717-721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper, J. A., and Kiehart, D. P. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 134 1345-1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macara, I. G., Baldarelli, R., Field, C. M., Glotzer, M., Hayashi, Y., Hsu, S. C., Kennedy, M. B., Kinoshita, M., Longtine, M., Low, C., Maltais, L. J., McKenzie, L., Mitchison, T. J., Nishikawa, T., Noda, M., et al. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13 4111-4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall, P. A., Jung, K., Hillan, K. J., and Russell, S. E. (2004) J. Pathol. 206 269-278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson, E. A., Kalikin, L. M., Steels, J. D., Estey, M. P., Trimble, W. S., and Petty, E. M. (2007) Mamm. Genome 18 796-807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kartmann, B., and Roth, D. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114 839-844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinoshita, M. (2003) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 134 491-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Field, C. M., al-Awar, O., Rosenblatt, J., Wong, M. L., Alberts, B., and Mitchison, T. J. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 133 605-616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frazier, J. A., Wong, M. L., Longtine, M. S., Pringle, J. R., Mann, M., Mitchison, T. J., and Field, C. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143 737-749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu, S. C., Hazuka, C. D., Roth, R., Foletti, D. L., Heuser, J., and Scheller, R. H. (1998) Neuron 20 1111-1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinoshita, M., Field, C. M., Coughlin, M. L., Straight, A. F., and Mitchison, T. J. (2002) Dev. Cell 3 791-802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Versele, M., and Thorner, J. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164 701-715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sirajuddin, M., Farkasovsky, M., Hauer, F., Kuhlmann, D., Macara, I. G., Weyand, M., Stark, H., and Wittinghofer, A. (2007) Nature 449 311-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xue, Y., Liu, D., Fu, C., Dou, Z., Zhou, Q., and Yao, X. (2006) Chin. Sci. Bull. 51 1836-1847 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, D., Ding, X., Du, J., Cai, X., Huang, Y., Ward, T., Shaw, A., Yang, Y., Hu, R., Jin, C., and Yao, X. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 21415-21424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao, X., Ding, X., Guo, X., Zhou, R., Forte, J. G., Teng, M., and Yao, X. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 13584-13592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, V. L., Scott, M. I. F., Holt, S. V., Hussein, D., and Taylor, S. S. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117 1577-1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lou, Y., Yao, J., Zereshki, A., Dou, Z., Ahmed, K., Wang, H., Hu, J., Wang, Y., and Yao, X. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 20049-20057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Low, C., and Macara, I. G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 30697-30706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu, H., and Yao, X. (2008) Cell Res. 18 218-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao, Y., Desai, A., and Cleveland, D. W. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 170 873-880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao, Y., Abrieu, A., and Cleveland, D. W. (2003) Cell. 114 87-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espeut, J., Gaussen, A., Bieling, P., Morin, V., Prieto, S., Fesquet, D., Surrey, T., and Abrieu, A. (2008) Mol. Cell 29 637-642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dou, Z., Ding, X., Zereshki, A., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, F., Sun, J., Huang, H., and Yao, X. (2004) FEBS Lett. 572 51-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrieu, A., Magnaghi-Jaulin, L., Kahana, J. A., Peter, M., Castro, A., Vigneron, S., Lorca, T., Cleveland, D. W., and Labbé, J. C. (2001) Cell 106 83-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeLuca, J. G., Dong, Y., Hergert, P., Strauss, J., Hickey, J. M., Salmon, E. D., and McEwen, B. F. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16 519-531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]