Abstract

The high capacity general amino acid permease, Gap1p, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is distributed between the plasma membrane and internal compartments according to availability of amino acids. When internal amino acid levels are low, Gap1p is localized to the plasma membrane where it imports available amino acids from the medium. When sufficient amino acids are imported, Gap1p at the plasma membrane is endocytosed and newly synthesized Gap1p is delivered to the vacuole; both sorting steps require Gap1p ubiquitination. Although it has been suggested that identical trans-acting factors and Gap1p ubiquitin acceptor sites are involved in both processes, we define unique requirements for each of the ubiquitin-mediated sorting steps involved in delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole upon amino acid addition. Our finding that distinct ubiquitin-mediated sorting steps employ unique trans-acting factors, ubiquitination sites on Gap1p, and types of ubiquitination demonstrates a previously unrecognized level of specificity in ubiquitin-mediated protein sorting.

INTRODUCTION

The movement of transmembrane proteins through the secretory pathway to a specific cellular or extracellular destination often requires specific targeting signals in the substrate protein (Harter and Wieland 1996). One signal utilized by transmembrane proteins to direct their intracellular distribution between organelles is ubiquitination. Ubiquitin is a highly conserved 76 amino acid peptide that can be covalently attached to lysine residues in a target protein through a series of coordinated enzymatic reactions (Pickart and Eddins, 2004). Ubiquitin molecules can also be linked to one another through the covalent attachment of one ubiquitin molecule to an exposed lysine residue in another to form ubiquitin chains (Hoppe, 2005). Although there are seven lysine residues in a single ubiquitin polypeptide, lysine 48 and lysine 63 are the most frequently used to form polyubiquitin chains (Peng et al., 2003). Therefore, proteins can be monoubiquitinated (one ubiquitin molecule on a single lysine residue), multiubiquitinated (one ubiquitin molecule on several separate lysine residues), or polyubiquitinated (several ubiquitin molecules in a chain on a single lysine residue).

Ubiquitin modification of transmembrane proteins has been shown to regulate several distinct intracellular processes including endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (McCracken and Brodsky, 2005), sorting in the trans-Golgi (Helliwell et al., 2001), endocytosis from the plasma membrane (Hicke and Riezman, 1996), and entry into the multivesicular endosome (MVE; Katzmann et al., 2001). Therefore, the ubiquitination status of a transmembrane protein can greatly impact its intracellular distribution, degradation, and resulting activity.

The expression, localization, and activity of the high-capacity general amino acid permease in S. cerevisiae, Gap1p, is regulated by amino acids such that it transports available amino acids from the surrounding medium into the cell only when internal amino acid levels are low (Stanbrough et al., 1995; Chen and Kaiser, 2002; Risinger et al., 2006). Previous studies have shown that ubiquitination of Gap1p on two N-terminal lysine residues (9 and 16) is required for redistribution of the permease from the plasma membrane to internal compartments (Soetens et al., 2001). This dynamic, ubiquitin-mediated regulation of Gap1p allows the cell to up-regulate amino acid import rapidly when internal amino acid levels become limiting, while avoiding excess amino acid import that we have found to be lethal (Roberg et al., 1997; Risinger et al., 2006).

Ubiquitin-mediated sorting of Gap1p to the vacuole can occur independently of the ability of Gap1p to be endocytosed by what we will henceforth refer to as “direct sorting” of the permease to the vacuole (De Craene et al., 2001; Helliwell et al., 2001). After newly synthesized Gap1p reaches the trans-Golgi, the permease can be polyubiquitinated on either lysine 9 or 16 by the Rsp5p-Bul1p-Bul2p ubiquitin ligase complex (Helliwell et al., 2001; Soetens et al., 2001). At the trans-Golgi, an ubiquitin-dependent sorting decision is made; nonubiquitinated Gap1p is sorted to the plasma membrane, whereas polyubiquitinated Gap1p is sorted to the multivesicular endosome. Once Gap1p reaches the MVE, the permease can either enter the vacuolar lumen and be degraded or recycle back to the trans-Golgi for another attempt at reaching the cell surface; this recycling step is inhibited by the presence of elevated internal amino acid levels or mutations such as lst4Δ (Chen and Kaiser, 2002; Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). This dynamic, ubiquitin-dependent recycling of Gap1p between the MVE and the trans-Golgi allows for rapid redistribution of the permease upon changing nutritional conditions (Roberg et al., 1997).

It appears that ubiquitination also plays a role in the endocytosis of Gap1p given the requirement of either one of the two ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues in the rapid loss of Gap1p activity at the plasma membrane upon ammonia addition in the Σ1278 strain background (Soetens et al., 2001). Although it has been determined that direct sorting of Gap1p is independent of endocytosis, it is unclear what role ubiquitin-mediated endocytosis plays in delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole independently of direct sorting because all known mutants that affect Gap1p trafficking have been shown to affect direct sorting of the permease. With no known mutant that differentially affects direct sorting and endocytosis of Gap1p, it has been suggested that identical cis- and trans-acting factors are required for both steps of ubiquitin-mediated Gap1p trafficking. Another possibility is that Gap1p endocytosis is a constitutive, ubiquitin-independent process and that the ubiquitin-mediated direct sorting of the permease dictates whether endocytosed Gap1p is redelivered to the plasma membrane or sent to the vacuole for degradation.

The isolation and characterization of mutants that affect the intracellular distribution of Gap1p has relied almost exclusively on the hypothesis that Gap1p activity is high when the permease is localized at the plasma membrane. However, our recent finding that Gap1p can be rapidly and reversibly inactivated at the plasma membrane prompted us to reevaluate this assumption (Risinger et al., 2006). Additionally, the effect of amino acid addition to mutants defective in Gap1p ubiquitination has been previously unstudied as the addition of any single amino acid (other than alanine or phenylalanine) is toxic to mutants defective in ubiquitin-mediated sorting of the permease. Our finding that this toxicity is due to an internal amino acid imbalance and that addition of rich amino acid mixtures (such as Casamino acids) are not toxic has allowed us to observe previously unrecognized differences between bul1/2Δ and GAP1K9R,K16R mutants (Risinger et al., 2006).

In this study, we clearly define the cis- and trans-acting factors for multiple unique ubiquitin-mediated sorting steps involved in delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole: 1) direct sorting from the trans-Golgi to the multivesicular endosome involving Rsp5p-Bul1/2p–dependent polyubiquitination of Gap1p on either lysine 9 or 16, 2) endocytosis involving Rsp5p-Bul1/2p–dependent monoubiquitination of Gap1p on lysine 9 or 16, and 3) endocytosis involving Rsp5p-dependent, Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination of Gap1p on lysine 16.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Plasmids, and Media

All of the yeast strains used in this study are of the S288C background, which expresses high Gap1p activity in SD ammonia medium (Courchesne and Magasanik, 1983).

Plasmids used in this study were pCK137, GAP1−HA in pRS316; pAR51, GAP1K9R-HA in pRS316; pAR58, GAP1K16R-HA in pRS316; pSH55, GAP1K9R,K16R-HA in pRS316; pCK231, CUP1-promoted UBI-c-myc in pRS423; pCK232, CUP1-promoted UBI in pRS423; pAR70, GAP1 in pRS316; pAR71, GAP1K9R in pRS316; pAR72, GAP1K16R in pRS316; pAR73, GAP1K9R,K16R in pRS316; pEC221, ADH1-promoted GAP1 in pRS316; pAR13, ADH1 promoted GAP1-GFP in pRS316; pAR14, ADH1-promoted GAP1K9R,K16R-GFP in pRS316; pAR32, ADH1-promoted GAP1K9R-GFP in pRS316; pAR33, ADH1-promoted GAP1K16R-GFP in pRS316; pAR88, GAP1E583D in pRS316; pAR18, GAP1E583D-HA in pRS316; pAR95, GAP1K9R, E583D in pRS316; pAR89, GAP1K16R,E583D in pRS316; pAR96, GAP1K9R,K16R,E583D in pRS316; pAR93, GAP1K16R,E583D-GFP in pRS316; pAR41, ADH1-promoted GAP1E583D-GFP in pRS316; and pAR134, Ub-GAP1K9R,K16R-HA in pRS316. All GAP1 constructs expressed from the wild-type GAP1 promoter unless otherwise indicated. The levels of GAP1 expressed from the ADH1 promoter are roughly equivalent to the levels of GAP1 expressed from the wild-type GAP1 promoter in minimal ammonia medium (Chen and Kaiser, 2002).

Strains were grown at 24°C in minimal (SD) medium unless otherwise noted. SD medium is composed of Difco (Detroit, MI) yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and without ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose, and 0.5% ammonium sulfate (adjusted to pH 4.0 with HCl). Casamino acid medium contains SD with Casamino acids (Difco) added from a 10% stock (pH 4.0) to a final concentration of 0.25%.

Screen for Gap1p Ubiquitination Mutants

GAP1 mutations were generated by mutagenic PCR using pEC221 (PADH1-GAP1) as a template and the methods described previously (Sevier and Kaiser, 2006) with modifications. A fragment including the entire GAP1 open reading frame (ORF) as well as 500 base pairs of the ADH1 promoter and 600 base pairs of the GAP1 3′ UTR was amplified in four 50-μl reactions with AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer-Cetus, Norwalk, CT) and 0.3 mM MnCl2. PCR products were transformed along with gapped pEC221 plasmid (lacking the GAP1 ORF) into CKY482 (gap1Δ ura3-52) and gap-repaired plasmids were isolated by selection for Ura+ transformants. Glycine-sensitive transformants were identified by replica plating onto SD with 1 mM glycine at 30°C. Plasmids were isolated from glycine-sensitive colonies, retransformed into CKY482, and retested for glycine sensitivity. Plasmids conferring sensitivity to glycine arose at a frequency of ∼10−3.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting of Gap1p

For the detection of Gap1 protein levels and monoubiquitination, cultures were grown in SD medium with or without the addition of 0.25% Casamino acids at the indicated temperature to early exponential phase. About 4 × 107 cells were collected and lysed in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, with 1 mM EDTA, pH 8, and protease inhibitors by agitation with glass beads. Proteins were solubilized by the addition of 4× sample buffer (4% SDS, 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 20 mM DTT, 0.02% bromophenol blue) resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE, and detected by immunoblot using rabbit anti-Gap1p antibody and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled sheep anti-rabbit serum (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

For the detection of Gap1p polyubiquitination, Gap1p−HA was immunoprecipitated and then detected by immunoblotting by following an adaptation of the protocol described by Laney and Hochstrasser (2002). A pep4Δ doa4Δ strain expressing the indicated GAP1−HA allele was also transformed with the indicated CUP1 promoted UBI allele and cultured in SD medium with 1 μM CuSO4 to exponential phase. Cells (n = 2 × 108) were collected on 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filters, suspended in 200 μl SDS buffer (1% SDS, 45 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, and 50 mM NEM containing protease inhibitors), and lysed with glass beads. Lysates were diluted in 700 μl of Triton buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM Na-EDTA, and 10 mM NEM with protease inhibitors), and centrifuged at 14,000 × g at 4°C. Immunoprecipitation was carried out by overnight incubation at 4°C with 10 μl of rat anti-HA [3F10] (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), followed by a 2-h incubation at 4°C upon addition of 60 μl of a 50% suspension of protein G-Sepharose 4 fast flow (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The beads were washed five times with 1% Triton in PBS, and immunoprecipitates were solubilized by incubation in sample buffer for 1 h at 37°C and resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE. Antibodies used were rabbit anti-Gap1p and mouse anti-myc [9E10] (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), HRP-coupled sheep anti-rabbit serum (Amersham Pharmacia), and HRP-coupled sheep anti-mouse serum (Amersham Pharmacia).

Fluorescence Microscopy

GAP1-GFP–expressing cells were cultured overnight in SD medium with or without the addition of 0.25% Casamino acids to exponential phase at 24°C. For latrunculin A treatment, 1 × 107 cells were centrifuged into 50 μl of SD medium and treated with 40 μM latrunculin A (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in EtOH for 20 min before Casamino acid addition. For cycloheximide chases, 50 μg/ml cycloheximide was added to cultures for 20 min before Casamino acid addition. For FM4-64 localization, cells were washed and suspended in prechilled SD medium (pH 7) containing 40 μM FM4-64 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and 50 μg/ml cycloheximide and incubated for 20 min at 4°C to load the plasma membrane with the dye. Cells were then spun at 4°C and suspended in 24°C SD medium containing 0.25% Casamino acids and cycloheximide. For all microscopy experiments, cells were harvested, resuspended in 300 mM Tris, pH 8, with 1.5% NaN3, and visualized using a fluorescence microscope at the indicated time after amino acid addition. Images were captured with a Nikon E800 microscope (Melville, NY) equipped with a Hamamatsu digital camera (Bridgewater, NJ). Image analysis was performed using Improvision OpenLabs 2.0 software (Lexington, MA).

Amino Acid Uptake Assays

Strains were cultured to 4–8 × 106 cells/ml and washed with nitrogen-free medium by filtration on a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filter before amino acid uptake assays were performed as described previously (Roberg et al., 1997).

Equilibrium Density Centrifugation and Antibodies

Yeast cellular membranes were fractionated by equilibrium density centrifugation on continuous 20–60% sucrose gradients containing EDTA as described (Kaiser et al., 2002). NEM (50 mM) was added to the lysis buffer to stabilize polyubiquitinated Gap1p against cysteine proteases. Antibodies used were: rabbit anti-Gap1p and HRP-coupled sheep anti-rabbit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Fractions were assayed for GDPase and immunoblotted for Pma1p as controls for proper separation of Golgi and plasma membrane fractions.

Internal Monoubiquitination Assay

Strains containing the sec6-4 temperature-sensitive mutation were grown at the permissive temperature of 24°C in SD medium with 3 mM glutamine to repress GAP1 expression. In exponential phase, cells were collected on 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filters, washed, and resuspended in SD medium prewarmed to either 24 or 36°C. Cells (n = 2 × 107) collected at the indicated time after medium shift were lysed and immunoblotted for Gap1p.

RESULTS

Bul1/2p-independent Monoubiquitination on Lysine 16 Is Sufficient for Delivery of Gap1p to the Vacuole

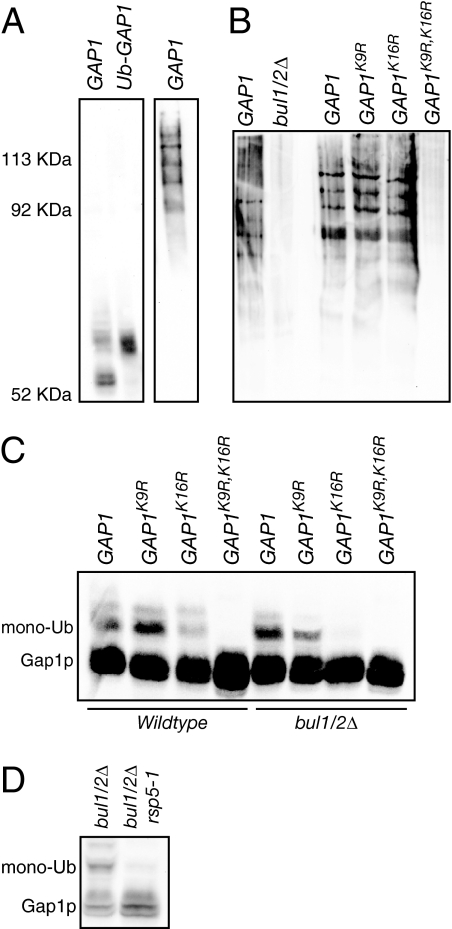

Previous work showed that Gap1p is polyubiquitinated in wild-type yeast cells, but receives only lower molecular weight modification consistent with the addition of one or two ubiquitin molecules (hereafter referred to as “monoubiquitination”) in the absence of the redundant BUL1 and BUL2 gene products (Helliwell et al., 2001; Soetens et al., 2001). Moreover, all Gap1p ubiquitination is prevented after mutation of lysine residues at position 9 and 16, indicating that these are the primary ubiquitin acceptor sites on Gap1p (Soetens et al., 2001). We found that both the unmodified and the monoubiquitinated forms of Gap1p could be detected by immunoblotting cell lysates with Gap1p antiserum (Figure 1A). Additionally, the low-molecular-weight modification of Gap1p observed in wild-type cell lysates comigrated with a form of Gap1p that was covalently fused to a single ubiquitin molecule, further suggesting that the identity of this upper band is indeed monoubiquitinated Gap1p protein (Figure 1A). Higher molecular weight ubiquitin modification of Gap1p could only be detected by immunoblotting for myc-tagged ubiquitin from Gap1p immunoprecipitates. The relative mobilities of the unmodified, monoubiquitinated, and polyubiquitinated protein are shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination of Gap1p occurs on either lysine 9 or 16, whereas Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination only occurs on lysine 16. (A) Lysates were prepared from gap1Δ (CKY482) expressing GAP1−HA (pCK137) or the Ub-GAP1K9R,K16R-HA fusion protein (pAR134) and immunoblotted with Gap1p antiserum (left), whereas pep4Δ doa4Δ gap1Δ (CKY1031) expressing Pcup1-myc-UBI (pCK231) and GAP1−HA (pCK137) were grown in SD medium + 1 μM CuSO4, Gap1p was immunoprecipitated with rat anti-HA (3F10), and forms of polyubiquitinated Gap1p were resolved by SDS/PAGE and detected by immunoblotting with anti-myc (9E10) (right). (B) pep4Δ doa4Δ gap1Δ (CKY1031) or bul1Δ bul2Δ pep4Δ doa4Δ gap1Δ (CKY1032) expressing Pcup1-myc-UBI (pCK231) and either GAP1−HA (pCK137), GAP1K9R-HA (pAR51), GAP1K16R-HA (pAR58), or GAP1K9R,K16R-HA (pSH55) were grown in SD medium + 1 μM CuSO4. Gap1p was immunoprecipitated with rat anti-HA (3F10) and forms of polyubiquitinated Gap1p were resolved by SDS/PAGE and detected by immunoblotting with anti-myc (9E10). The samples were adjusted to contain equivalent amounts of Gap1p as determined by immunoblotting with Gap1p antiserum. (C) Lysates were prepared from gap1Δ (CKY482) or bul1Δ bul2Δ gap1Δ (CKY701) expressing GAP1 (pAR70), GAP1K9R (pAR71), GAP1K16R (pAR72), or GAP1K9R,K16R (pAR73) and immunoblotted with Gap1p antiserum. Forms of Gap1p with one or two added ubiquitin molecules are labeled “monoub.” (D) Lysates were prepared from bul1Δ bul2Δ (CKY698), or bul1Δ bul2Δ rsp5-1 (CKY714) grown at 37°C and immunoblotted with Gap1p antiserum.

We examined single and double lysine mutants to determine how the different types of ubiquitin modifications were distributed between the two potential acceptor sites. The high-molecular-weight polyubiquitin conjugates of Gap1p, detected by probing Gap1p immunoprecipitates with antibodies to myc-tagged ubiquitin, were present for either of the single lysine mutants but not for the double mutant of lysines 9 and 16 (Figure 1B). In addition, monoubiquitin conjugates, detected on immunoblots of whole cell lysates with Gap1p antibody, were also present for either of the single mutants but not for the double lysine mutant (Figure 1C). It is worth noting that Gap1p appears to run as a doublet even in the nonubiquitinated Gap1pK9R,K16R mutant. The fact that this doublet is observed in a Gap1pK9R,K16R mutant along with the fact that the upper band migrates lower than the monoubiquitinated form of Gap1p suggests that it is not a result of ubiquitin modification. At this time, we are unsure as to the significance of this doublet as we have observed that it does not collapse upon phosphatase treatment and is present in all growth conditions we have tested.

In addition to the finding that no polyubiquitin conjugates were able to form in a bul1/2Δ double mutant (Figure 1B), we also observed the Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitin conjugates that formed on wild type or Gap1pK9R were unable to form on Gap1pK16R (Figure 1C). Although these monoubiquitin conjugates on lysine 16 did not depend on the Bul1/2p proteins, they still required the Rsp5p ubiquitin ligase for their formation (Figure 1D). Taken together, these results show that Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination of Gap1p in wild-type cells can use either lysine 9 or lysine 16 as an acceptor site, whereas the monoubiquitination that takes place in a bul1/2Δ strain can use only lysine 16 as an acceptor site.

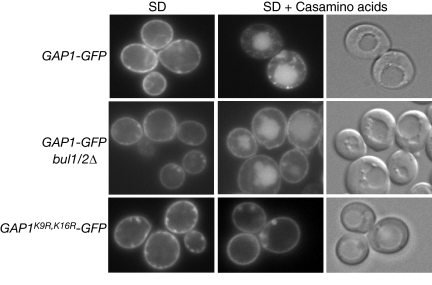

In a bul1/2Δ double mutant, intracellular trafficking of Gap1p from the Golgi to the vacuole is blocked completely (Helliwell et al., 2001; Soetens et al., 2001), but it is not known what if any effect monoubiquitination of Gap1p that occurs in this strain might have on intracellular trafficking. In wild-type cells, Gap1p-GFP was located primarily at the plasma membrane when grown on minimal medium, but was located primarily in the vacuolar lumen when grown in the presence of amino acids (Figure 2), a condition that blocks completely the recycling of Gap1p from the MVE to the plasma membrane (Chen and Kaiser, 2002; Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). A double lysine mutant (Gap1pK9R,K16R-GFP) is located at the plasma membrane even in the presence of amino acids (Figure 2), indicating that no trafficking of Gap1p to the vacuole could occur in the total absence of ubiquitin modification. However, we found that Gap1p-GFP was delivered to the vacuole in a bul1/2Δ mutant grown in the presence of amino acids (Figure 2). Evidently lysine 16 monoubiquitination is necessary and sufficient for Gap1p to be delivered to the vacuole under these conditions as Gap1pK9R-GFP was delivered to the vacuole in a bul1/2Δ mutant, whereas Gap1pK16R -GFP was not (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Monoubiquitination of Gap1p is sufficient for delivery to the vacuole. gap1Δ (CKY482) or bul1Δ bul2Δ gap1Δ (CKY701) expressing PADH1-GAP1-GFP (pAR13) or PADH1-GAP1K9R,K16R-GFP (pAR14) were grown in SD medium with or without addition of 0.25% Casamino acids and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Localization of Gap1p-GFP to the vacuoles in wild-type and bul1Δ bul2Δ strains is evident by comparison to the DIC images, which show the location of the vacuoles by their different refractive properties from the cell body.

Figure 3.

Monoubiquitination of Gap1p is necessary and sufficient for endocytosis. (A) gap1Δ (CKY482) expressing PADH1-GAP1-GFP (pAR13) was treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for 20 min before addition of 0.25% Casamino acids. At the indicated time after amino acid addition, cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. (B) gap1Δ (CKY482) or bul1Δ bul2Δ gap1Δ (CKY701) expressing PADH1-GAP1-GFP (pAR13), PADH1-GAP1K9R-GFP (pAR32), or PADH1-GAP1K16R-GFP (pAR33) were grown in SD medium with 0.25% Casamino acids for 5 h and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. This experiment was performed in the absence of cycloheximide to allow direct sorting of newly synthesized Gap1p to the vacuole. No additional change in Gap1p localization was observed at later time points (up to 24 h) after amino acid addition, suggesting a steady-state distribution of Gap1p in the presence of amino acids. Where latrunculin A treatment is indicated (+Lat A), cells were incubated in the presence of 40 μM latrunculin A for 20 min before amino acid addition.

Either Bul1/2p-dependent or -independent Pathways Are Sufficient for Gap1p Endocytosis

To assess the role of endocytosis in Bul1/2p-independent delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole, we took advantage of the ability of the actin inhibitor latrunculin A to rapidly and selectively block endocytosis (Ayscough et al., 1997). Endocytosis of Gap1p-GFP was visualized while blocking new synthesis of Gap1p-GFP by adding cycloheximide to cells, after which the addition of amino acids amino acids resulted in redistribution of Gap1p-GFP from the plasma membrane to the vacuole within 60 min (Figure 3A). When latrunculin A was added to cycloheximide-treated cells before amino acid addition, endocytic traffic was blocked and Gap1p-GFP remained at the plasma membrane for more than 120 min (Figure 3A). In contrast, Gap1p-GFP accumulated in the vacuole when amino acids were added to latrunculin A–treated cells without cycloheximide pretreatment, illustrating that latrunculin A does not block the trafficking of newly synthesized Gap1p-GFP to the vacuole through the nonendocytic, direct biosynthetic pathway (Figure 3B). Importantly, latrunculin A blocked delivery of Gap1p-GFP to the vacuole in the bul1/2Δ mutant not treated with cycloheximide, demonstrating that Bul1/2p-independent trafficking to the vacuole was due to endocytosis (Figure 3B).

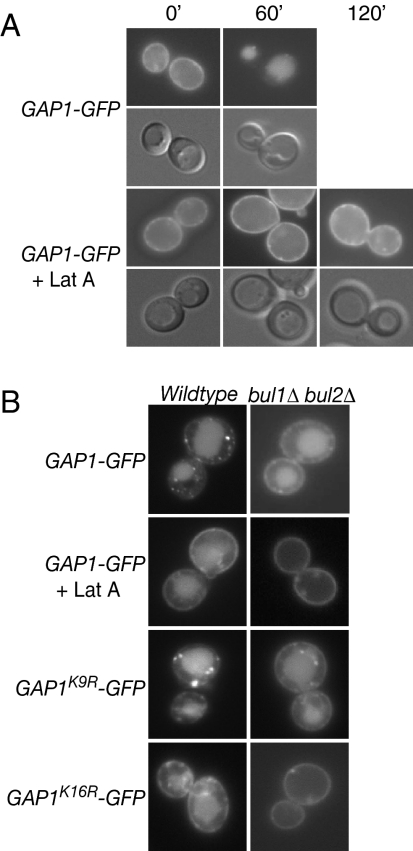

We determined that Gap1pK16R-GFP was able to be endocytosed in a wild-type strain background (Figure 4) but not in bul1/2Δ (Figure 3B), indicating that there is also a Bul1/2p-dependent route by which Gap1p can be endocytosed. Indeed, we find that the single GAP1K16R or bul1/2Δ mutations allow the permease to be effectively endocytosed, albeit with a possible delay compared with endocytosis in a wild-type strain (Figure 4), whereas a GAP1K16R bul1/2Δ double mutant inhibits any delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole (Figure 3B). We also demonstrated that Gap1p follows the canonical endocytic pathway between loss of plasma membrane localization and delivery to the vacuole by colocalization of the permease with the lypophilic dye FM4-64, which is commonly used as a marker of endocytic vesicles on route to the vacuole (Figure 5). Thus we have delineated distinct requirements for ubiquitin-dependent trafficking from the Golgi to the vacuole (direct sorting) and the plasma membrane to the vacuole (endocytosis): direct sorting is specified by Rsp5p-Bul1/2p–dependent polyubiquitination that can occur on either lysine 9 or lysine 16, whereas endocytosis can be specified by either Rsp5p-Bul1/2p–dependent monoubiquitination on lysine 9 (and presumably lysine 16) or by Rsp5p-dependent, Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination that occurs specifically on lysine 16.

Figure 4.

Bul1/2p-dependent and -independent pathways for ubiquitin-mediated endocytosis of Gap1p. gap1Δ (CKY482) or gap1Δ bul1Δ bul2Δ (CKY701) expressing PADH1-GAP1-GFP (pAR13) or PADH1-GAP1K16R-GFP (pAR33) were grown in SD medium. Cells were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for 20 min before addition of 0.25% Casamino acids. At the indicated time after amino acid addition, cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Figure 5.

Gap1p colocalizes with endocytic vesicles. gap1Δ (CKY482) expressing PADH1-GAP1-GFP (pAR13) was grown in SD medium. Cells were incubated on ice for 30 min in the presence of the lipophilic dye FM4-64 in SD medium (pH 7.0) and then washed and suspended in SD medium containing 0.25% Casamino acids. At the indicated time after amino acid addition and FM4-64 washout, Gap1p and FM4-64 were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Cells were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for 20 min before amino acid addition and removal of FM4-64.

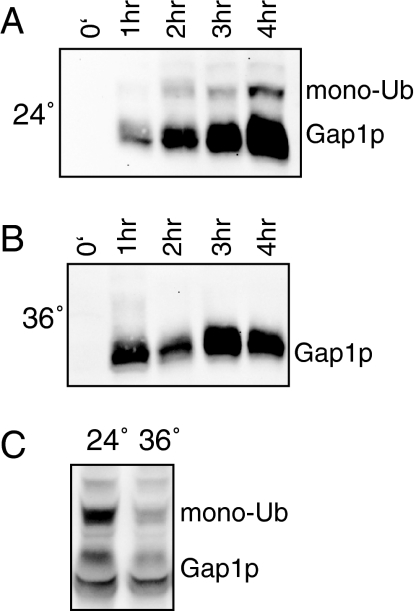

Bul1/2-independent Monoubiquitination Does Not Occur before Gap1p Delivery to the Plasma Membrane

Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination is necessary for direct sorting of Gap1p to the vacuole independently of the endocytic pathway (Figure 3B and Helliwell et al., 2001). This result implies that that Bul1/2p-dependent modification of Gap1p by addition of polyubiquitin chains occurs before Gap1p has been delivered to the plasma membrane, probably in the Golgi. We wondered whether Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination of Gap1p failed to occur in intracellular compartments before delivery of the permease to the plasma membrane or whether this modification could occur in the Golgi but was insufficient for direct sorting of Gap1p from the Golgi to vacuole. To determine where in the cell monoubiquitination occurs in a bul1/2Δ mutant, we utilized a sec6-4 temperature-sensitive mutation that, at the restrictive temperature of 36°C, blocks fusion of post-Golgi secretory vesicles with the plasma membrane (Novick et al., 1980; Walworth and Novick, 1987). We grew a sec6-4 bul1/2Δ mutant at the permissive temperature of 24°C in SD medium containing 3 mM glutamine to repress GAP1 transcription. Cells were then transferred to SD medium without glutamine to induce a pulse of GAP1 expression at the permissive or restrictive temperature. Figure 6 shows that, as expected, some of the newly synthesized Gap1p is modified by monoubiquitination at the permissive temperature of 24°C, but that no ubiquitin modification is evident at the restrictive temperature of 36°C. Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination of Gap1p was not inhibited at 36°C in a bul1/2Δ strain, demonstrating that this modification was not intrinsically temperature sensitive (Figure 6C). These results show that Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination of Gap1p does not occur before delivery of Gap1p to the plasma membrane.

Figure 6.

Bul1/2p-independent ubiquitination does not occur before delivery of Gap1p to the plasma membrane. sec6-4 bul1Δ bul2Δ (CKY1033) was grown in SD medium with 3 mM glutamine at 24°C. In early exponential phase, cells were filtered, washed, and suspended in SD medium at (A) 24°C or (B) 36°C. Lysates were prepared at the indicated time after media and temperature shift and immunoblotted with Gap1p antiserum. (C) bul1Δ bul2Δ (CKY698) was grown in SD medium at 24 or 36°C. Lysates were immunoblotted with Gap1p antiserum.

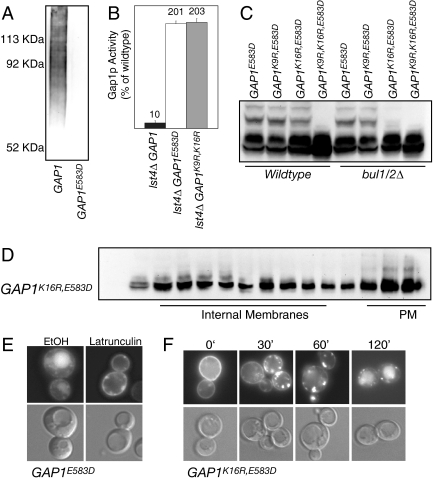

A Point Mutation in the C-terminal Tail of Gap1p Blocks Both Polyubiquitination and Direct Sorting of Gap1p from the Golgi to Vacuole

We isolated cis-acting mutations that prevent ubiquitination of Gap1p by exploiting the fact that ubiquitination defective mutants of Gap1p fail to properly down-regulate Gap1p activity in response to amino acids thus rendering yeast cells sensitive to high levels of amino acids in the growth medium (Risinger et al., 2006). In our collection of amino acid–sensitive GAP1 mutants we identified a point mutation in the C-terminal cytosolic tail (Gap1pE583D) that failed to receive polyubiquitin chains in an otherwise wild-type strain (Figure 7A). Mutants deficient in direct sorting of Gap1p to the vacuole allow Gap1p to be delivered to the plasma membrane even in the presence of a lst4Δ mutant, which completely blocks recycling of Gap1p from the MVE to the plasma membrane (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser 2006). We found that Gap1pE583D could be delivered to the plasma membrane in a lst4Δ mutant, indicating that this mutant is impaired in direct sorting of the permease from the trans-Golgi to the MVE (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

A cis-acting mutant that specifically blocks Gap1p polyubiquitination. (A) pep4Δ doa4Δ gap1Δ (CKY1031) expressing Pcup1-myc-UBI (pCK231) and either GAP1−HA (pCK137) or GAP1E583D-HA (pAR18) was grown in SD medium +1 μM CuSO4. Gap1p was immunoprecipitated with rat anti-HA (3F10) and separated by SDS/PAGE. Ubiquitinated forms of Gap1p were detected by immunoblotting with anti-myc (9E10). Levels of unmodified Gap1 were equivalent in all lanes. (B) The Gap1p activity of lst4Δ gap1Δ (CKY702) expressing GAP1 (pAR70), GAP1E583D (pAR88), or GAP1K9R,K16R (pAR73) was measured by assaying the rate of uptake of [14C]-citrulline. (C) Lysates from gap1Δ (CKY482) or bul1Δ bul2Δ gap1Δ (CKY701) expressing GAP1E583D (pAR88), GAP1K9R,E583D (pAR95), GAP1K16R,E583D (pAR89), or GAP1K9R,K16R,E583D (pAR96) were immunoblotted with Gap1p antiserum. (D) Membranes from gap1Δ (CKY482) expressing GAP1K16R,E583D (pAR89) were fractionated on 20–60% sucrose density gradients containing EDTA. Fractions were collected, proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE, and Gap1p was detected by immunoblotting with Gap1p antiserum. The location on the gradient for fractionation of markers for Golgi and endosome (internal membranes) and plasma membrane (PM) are indicated. (E) gap1Δ (CKY482) expressing PADH1-GAP1E583D-GFP (pAR41) was treated with either 40 μM latrunculin A or vehicle (EtOH) for 20 min before addition of 0.25% Casamino acids. Five hours after amino acid addition cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy. (F) gap1Δ (CKY482) expressing PADH1-GAP1K16R,E583D-GFP (pAR93) was treated for 20 min with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide, followed by addition of 0.25% Casamino acids. At the indicated time after amino acid addition, cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy.

Although the Gap1pE583D mutant did not receive Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination, we determined that it still could be monoubiquitinated (Figure 7C). By mutating the potential acceptor lysine residues in the context of a Gap1pE583D mutation, we found that, as with wild-type Gap1p, monoubiquitination occurred by two genetically separable pathways; Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination on lysine 16 as well as by Bul1/2p-dependent monoubiquitination on lysine 9 or 16 (Figure 7C). The form of Gap1pK16R,E583D that had received Bul1/2p-dependent monoubiquitination on lysine 9 was found primarily in plasma membrane containing fractions, indicating that this modification was likely involved in mediating Bul1/2p-dependent endocytosis (Figure 7D). Indeed, delivery of Gap1pE583D to the vacuole in the presence of amino acids was abolished upon addition of the endocytosis inhibitor latrunculin A (Figure 7E). Gap1pK16R,E583D displayed no defects in endocytosis when compared with the Gap1pK16R mutant (compare Figures 4 and 7F), indicating that Bul1/2p-dependent monoubiquitination on lysine 9 was sufficient to direct endocytosis.

The properties of the GAP1E583D mutant contribute to our understanding of ubiquitin-mediated Gap1p trafficking in two ways. First, the fact that this mutation lies in the cytosolic C-terminal domain but prevents Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination of the N-terminal domain suggests that the N- and C-terminal domains of Gap1p interact in some way to form a substrate for the Rsp5p/Bul1/2p ubiquitin ligase complex. Second, although Gap1pE583D is unable to receive Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination, the mutant protein retains the ability to receive Bul1/2p-dependent monoubiquitination. Thus the Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination event in the Golgi and monoubiquitination event at the plasma membrane exhibit different requirements for recognition of cis-acting signals on the Gap1p protein.

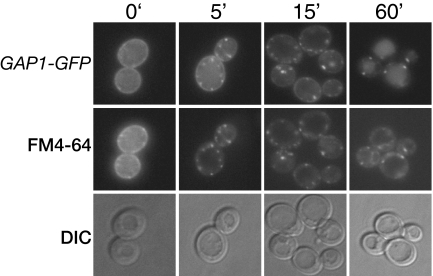

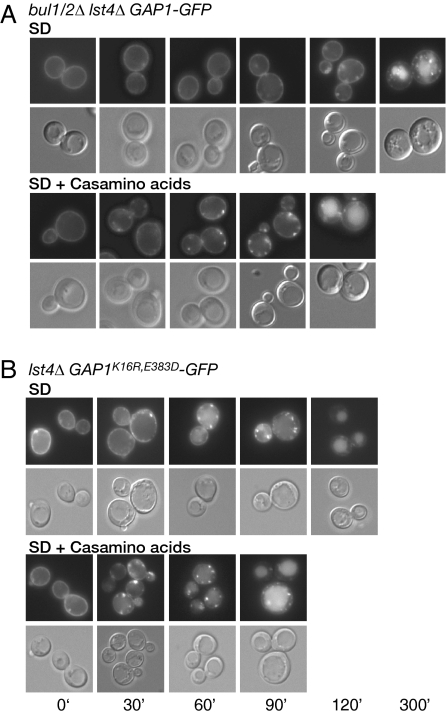

Amino Acids Appear to Enhance Gap1p Endocytosis Independently of Ubiquitin Addition

We wanted to determine the effect of exogenously added amino acids on each of the two genetically separable pathways for ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of Gap1p. We monitored Gap1p endocytosis by following the disappearance of Gap1p-GFP from the plasma membrane after addition of cycloheximide to stop de novo synthesis of Gap1p. The existence of a pathway for recycling of endocytosed Gap1p from the MVE back to the plasma membrane (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006) presents a significant complication for such assays that rely on measuring changes in the distribution of Gap1p-GFP. When the recycling pathway is active, as for example in a wild-type strain grown in the absence of exogenous amino acids, the permease can be recycled faster then it is endocytosed, which would lead to a gross underestimate of Gap1p internalization over time. This effect can be seen in Figure 2, which shows that the steady-state distribution of Gap1p-GFP in a bul1/2Δ double mutant is equally divided between the plasma membrane and vacuole when recycling is blocked by the presence of amino acids, but is entirely at the plasma membrane when the recycling is active in the absence of exogenous amino acids.

To eliminate all recycling of Gap1p, we used a lst4Δ mutant that blocks this redelivery to the plasma membrane even in the absence of amino acid levels (Chen and Kaiser, 2002; Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). Accordingly, we used a bul1/2Δ lst4Δ triple mutant to follow Bul1/2p-independent endocytosis (Figure 8A). This experiment is feasible because bul1/2Δ is epistatic to lst4Δ for initial delivery of Gap1p-GFP to the plasma membrane, allowing us to begin the experiment with most of Gap1p-GFP at the cell surface.

Figure 8.

Amino acids enhance Gap1p endocytosis through both Bul1/2p-dependent and -independent pathways. Endocytosis was followed in either the absence (SD) or the presence (SD + Casamino acids) of exogenous 0.25% Casamino acids. Cells were visualized by microscopy and fluorescence and DIC images of representative cells are shown at different times after addition of 50 μg/ml cycloheximide to prevent new synthesis of Gap1p-GFP. (A) Bul1/2p-independent endocytosis was followed in bul1Δ bul2Δ lst4Δ GAP1-GFP (CKY1034). (B) Bul1/2p-dependent endocytosis was followed in a lst4Δgap1Δ mutant (CKY702) expressing PADH1-GAP1K16R,E583D-GFP (pAR93).

Because a lst4Δ mutation prevents delivery of Gap1p to the cell surface in strains that have wild-type BUL1/2 function, conditions for observing Bul1/2p-dependent endocytosis were more difficult to achieve. For this purpose we took advantage of the GAP1E583D mutant, which we showed blocks Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination and internal sorting of Gap1p, but apparently does not interfere with Bul1/2p-dependent monoubiquitination and endocytosis at the plasma membrane (Figure 7). Moreover, by mutation of lysine 16 we should eliminate all Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination. Accordingly, Bul1/2p-dependent endocytosis was determined by following the internalization of Gap1pK16R,E583D-GFP in a lst4Δ background (Figure 8B).

Figure 8B shows that, in the absence of amino acid addition, vacuolar delivery of Gap1pK16R,E583D-GFP in a lst4Δ mutant is complete in ∼120 min, whereas Figure 8A shows it takes more than 300 min for Gap1p-GFP to be delivered to the vacuole in a bul1/2Δ lst4Δ triple mutant. Thus, although both Bul1/2p-dependent and -independent processes contribute to endocytosis in wild-type cells, the Bul1/2p-dependent ubiquitination event may make a greater contribution. We also found that endocytosis of Gap1pK9R-GFP was indistinguishable from that of Gap1p-GFP (data not shown). Therefore, when lysine 16 is present, the additional presence of lysine 9 does not appear to have a drastic effect on ubiquitin-mediated endocytosis, further suggesting Bul1/2-dependent endocytosis can occur via monoubiquitination on lysine 16 as well as lysine 9.

Figure 8 also suggests that addition of Casamino acids to the medium may enhance the loss of Gap1p from the plasma membrane through both the Bul1/2p-dependent and -independent endocytosis pathways. We wondered whether amino acids might stimulate the ubiquitination of Gap1p at the plasma membrane. To test for this possibility, we prepared cell extracts from strains grown under identical conditions to those shown in Figure 8 and immunoblotted lysates with Gap1p antiserum to ascertain the fraction of Gap1p that was ubiquitinated over time. The amount of monoubiquitinated Gap1p for all strains and time points was similar to that shown in Figures 1C and 7C and was not altered significantly by the presence of Casamino acids (data not shown). A caveat in the interpretation of such experiments is that the steady-state amount of ubiquitinated Gap1p may not accurately reflect the rate of ubiquitin addition because the ubiquitin modified species is expected to be targeted to the vacuole and thus be degraded more rapidly than nonubiquitinated Gap1p. To stabilize ubiquitinated Gap1p at the plasma membrane, we took advantage of the ability of latrunculin A to block endocytosis of ubiquitinated Gap1p and thus prevent its degradation in the vacuole. We repeated the immunoblotting experiments after adding latrunculin A to cells, but again the presence amino acids had no discernable effect on the amount of monoubiquitinated Gap1p (data not shown). Thus, although amino acids appear to enhance Gap1p endocytosis through both Bul1/2p-dependent and -independent pathways, we could not find a corresponding effect on the amount of ubiquitinated Gap1p. Our preliminary findings suggest that amino acids exert their effect on endocytosis of Gap1p not by increasing the amount of monoubiquitinated Gap1p but by increasing the probability by which monoubiquitinated Gap1p is endocytosed. At present we do not have any other information on what endocytic components might be regulated by the presence of amino acids.

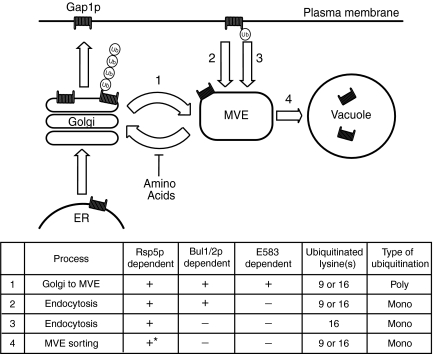

DISCUSSION

Conjugation of ubiquitin to the cytoplasmic portion of integral membrane proteins can be used as a covalent tag to direct thus modified proteins along specific intracellular sorting pathways. Examples from a variety of different eukaryotic species have identified three different types of membrane-trafficking steps that can be subject to regulation by ubiquitination: endocytic trafficking from the plasma membrane to the endosome (Kolling and Hollenberg, 1994; Hicke and Riezman, 1996; Terrell et al., 1998), trafficking from the trans-Golgi to the endosome (Helliwell et al., 2001), and sorting into the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport)-dependent inwardly budding vesicles of the MVE (Katzmann et al., 2001, 2004; Reggiori and Pelham 2001). Gap1p permease is unusual in that it is subject to all three of these ubiquitin-dependent sorting events in its overall partitioning between the plasma membrane and the vacuole. In this article we compare the requirements for ubiquitin-dependent sorting of Gap1p in the Golgi and at the plasma membrane with respect to both cis-acting sequences within Gap1p as well as the components in the Rsp5p ubiquitin ligase complex (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Different requirements for ubiquitination at different stages of intracellular trafficking of Gap1p. Gap1p is sorted to the vacuole by four distinct ubiquitin-dependent mechanisms. (1) Direct sorting of Gap1p from the Golgi to the MVE as a result of Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination on either lysine 9 or 16, which is blocked in bul1/2Δ, GAP1E8583D, GAP1K9R,K16R, or upon cycloheximide treatment. (2) Endocytosis of Gap1p as a result of Bul1/2p-dependent monoubiquitination on lysine 9 or 16, which is blocked in bul1/2Δ, GAP1K9R,K16R, or upon latrunculin A treatment. (3) Endocytosis of Gap1p as a result of Bul1/2p-independent monoubiquitination on lysine16, which is blocked in GAP1K16R or upon latrunculin A treatment. (4) Delivery into the vacuolar lumen by budding into the MVE and fusion with the vacuole. Our finding that Gap1p is delivered to the vacuolar lumen in bul1/2Δ, GAP1K9R, GAP1K16R, or GAP1E583D mutants suggests that monoubiquitination on lysine 9 or 16 is sufficient for MVE sorting. *We cannot directly determine whether Rsp5p is required for MVE sorting of Gap1p because Rsp5p is required for Gap1p to reach the endosome. However, findings that Rsp5p is required for MVE sorting of other cargo that reach the endosome in an Rsp5p-independent manner makes it likely that Rsp5p is involved in MVE sorting of Gap1p as well (Katzmann et al., 2004; McNatt et al., 2006).

At the trans-Golgi, Gap1p can be polyubiquitinated by the Rsp5p-Bul1p-Bul2p ubiquitin ligase complex and then directly sorted to the vacuole. The Bul proteins have also shown to be required for polyubiquitination of the tryptophan permease Tat2p independently of delivery to the plasma membrane, further demonstrating the activity of the Rsp5p-Bul1p-Bul2p ubiquitin ligase complex in direct sorting of cargo (Umebayashi and Nakano, 2003). The polyubiquitination of Gap1p requires either lysine 9 or lysine 16 of the permease because the extent of polyubiquitination is not altered by a single mutation of either lysine residue, but ubiquitination is eliminated entirely when both lysine residues are mutated. In addition to these acceptor lysine residues in the N-terminal cytosolic segment of Gap1p, the C-terminal cytosolic segment also participates in the recognition of Gap1p by the ubiquitin ligase complex as shown by the ability of a point mutation in the C-terminal segment (GAP1E583D) to completely block polyubiquitination of Gap1p. Evidently, the N- and C-terminal cytosolic portions of Gap1p coassemble to form a complex signal for recognition by the Rsp5p-Bul1p-Bul2p ubiquitin ligase complex.

Mutations that block Gap1p polyubiquitination (i.e., a bul1Δ bul2Δ double mutant or a cis-acting GAP1E583D mutation) appear to prevent all ubiquitination at the trans-Golgi. Thus, we have not been able to ascertain whether monoubiquitination of Gap1p would be sufficient for Golgi to endosome sorting. To test whether a single ubiquitin molecule appended to Gap1p would be sufficient to direct Gap1p sorting from the Golgi to the endosome, we appended the ubiquitin coding sequence to the 5′ end of the GAP1 gene. The idea was to produce a type of ubiquitin fusion protein that has been shown to be sufficient to direct delivery of CPS into the MVE (Katzmann et al., 2004) or endocytosis of Ste2p (Terrell et al., 1998). The Ub-GAP1 hybrid gene produced a fusion protein that had the same mobility on SDS-PAGE as monoubiquitinated Gap1p but was unable to receive the addition of polyubiquitin chains to the in-frame ubiquitin or the normal ubiquitin-accepting lysine residues (Figure 1A and data not shown). Both the Ub-GAP1 and Ub-GAP1K9R,K16R fusion constructs were constitutively trafficked from the Golgi to the plasma membrane (data not shown), leading to the conclusion that not only is an N-terminal fusion to ubiquitin not sufficient for direct sorting of Gap1p from the Golgi to endosome, but that addition of the extra ubiquitin sequence to the N-terminus of Gap1p interferes with the normal polyubiquitination and sorting of wild-type Gap1p. Thus, whether or not monoubiquitination of lysine 9 or lysine 16 would be sufficient to target Gap1p from the Golgi to endosome remains an open question.

Gga1p and Gga2p are conserved adaptor proteins involved in protein sorting that have been shown to colocalize with Golgi and endosomal markers and contain ubiquitin-binding motifs (Puertollano and Bonifacino, 2004; Scott et al., 2004). Scott et al. found that a gga1Δ gga2Δ double mutant slowed delivery of Gap1p to the vacuole in the presence of glutamate suggesting that the Gga proteins are involved in trafficking of Gap1p to the vacuole. The GAP1E583D mutant, which specifically blocks sorting of Gap1p from the trans-Golgi to the endosome but does not greatly affect the extent of Gap1p endocytosis provides a useful standard of comparison to evaluate whether the loss of Gga function impairs direct sorting of Gap1p from the Golgi to the endosome. The most stringent test we have for a defect in Golgi-to-endosome trafficking of Gap1p is to evaluate Gap1p permease activity in the context of a lst4Δ mutant. A lst4Δ mutant has very little Gap1p at the plasma membrane and only ∼2% of the permease activity as wild type because a lst4Δ mutant effectively blocks recycling of Gap1p from the endosome (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). In contrast, mutants such as bul1Δ bul2Δ and GAP1E583D, which prevent Gap1p ubiquitination at the Golgi and inhibit delivery of Gap1p to the endosome, exhibit high Gap1p activity in a lst4Δ genetic background. We found that a gga1Δ gga2Δ lst4Δ triple mutant exhibits very low Gap1p activity, similar to that of a lst4Δ single mutant, confirming a previous analysis showing that Gap1p-GFP is localized to intracellular compartments in the triple mutant (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). These data indicate that if the Gga proteins do participate in direct sorting of polyubiquitinated Gap1p from the trans-Golgi to the endosome, their role in this process is much less important than the ubiquitin modification of Gap1p. The behavior of gga1Δ gga2Δ mutants evaluated here and shown previously is most consistent with a requirement for the Gga protein in efficient delivery of ubiquitinated Gap1p into the interior of the MVE (Puertollano and Bonifacino, 2004; Scott et al., 2004).

In contrast to polyubiquitination at the Golgi, which can take place on either lysine 9 or lysine 16 and depends on the presence of a functional Bul protein, monoubiquitination and endocytosis of Gap1p at the plasma membrane can take place by two distinct processes; both processes require Rsp5p but one requires Bul1/2p and can apparently occur on lysine 16 or lysine 9, whereas the other process does not require Bul1/2p and can only occur on lysine 16. The GAP1E583D allele, which does not receive Bul1/2p-dependent polyubiquitination but can be modified and endocytosed by either Bul1/2p-dependent or -independent processes, shows that monoubiquitination of Gap1p is sufficient for either route of endocytosis. In this respect, ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of Gap1p is like all other ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis processes documented in yeast and mammalian cells (Staub and Rotin, 2006).

To explore the specificity of the type of ubiquitin required for recognition by the endocytosis machinery, we monitored localization of the ubiquitin-Gap1pK9R,K16R fusion protein upon amino acid addition. We determined that this N-terminal ubiquitin tag was insufficient for endocytosis of Gap1p, because the recombinant protein remained at the plasma membrane in the presence elevated amino acid levels (data not shown). Our finding that the fusion of ubiquitin to the N-terminus of Gap1p is an insufficient substitute for the monoubiquitination of lysine residues less than twenty amino acids away further demonstrates the specificity required for the proper ubiquitination and sorting of Gap1p.

Comparison of the requirements for Gap1p ubiquitination at the Golgi with ubiquitination at the plasma membrane reveals interesting differences in the activity of the Rsp5p-Bul1p-Bul2p ubiquitin ligase complex in these two locations. In the Golgi, this complex adds polyubiquitin chains and is blocked by a GAP1E583D mutation, whereas in the plasma membrane a related ubiquitin ligase complex only adds one or two ubiquitin molecules and is not blocked by a GAP1E583D mutation. Evidently the Rsp5p-Bul1p-Bul2p ubiquitin ligase complex recognizes different features of Gap1p and can act either processively or nonprocessively depending on whether Gap1p is located in the Golgi or at the plasma membrane. A precedent for a similar type of dual activity is found in the APC E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is required for entry into anaphase in cell cycle progression. APC binding to substrate can result in either mono- or polyubiquitination of the substrate protein depending on D box sequences in the substrate protein that stabilize interaction with APC (Prakash et al., 2005). For example, the APC substrates securin and geminin have a more processive interaction with APC than cyclin A, dictating the order in which these substrates are polyubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome and assuring proper progression through the cell cycle.

In the S288C genetic background, the abundance of intracellular amino acids controls the overall distribution of Gap1p between the plasma membrane and the vacuole. We showed previously that the most significant effect of amino acids on the trafficking of Gap1p is to inhibit recycling of Gap1p from the endosome to the plasma membrane, a step that apparently is not intrinsically dependent on ubiquitin modification of Gap1p (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). Earlier work on Gap1p regulation in the Σ1278b genetic background, in which Gap1p is down-regulated by ammonia, indicated that the presence of ammonia in the medium causes an increase in Gap1p ubiquitination and endocytosis from the plasma membrane (Springael and Andre, 1998). Accordingly, we checked for changes in the amount of Gap1p ubiquitination in the S288C genetic background, in response to the presence of amino acids in the growth medium. We found previously that amino acids do not significantly increase the amount of Gap1p polyubiquitination in the Golgi (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). Similarly, when we quantified the amount of monoubiquitinated Gap1p produced by either the Bul1/2p-dependent or -independent pathways for endocytosis, we did not detect an appreciable difference in the amount of Gap1p monoubiquitination in the presence or absence of exogenous amino acids. Nevertheless, we did find that Casamino acids in the medium increased by about twofold the rate of endocytosis of Gap1p by either the of the endocytic pathways. Thus, although ubiquitination is necessary for endocytosis of Gap1p, a different rate-limiting step of the endocytic pathway appears to be influenced by amino acids. We do not know what the regulated step is, but an attractive possibility is that the average conformation of Gap1p itself changes when exogenous amino acids are present in the medium and that this conformational state is optimal for entry of Gap1p into the endocytic pathway.

We can deduce that a fourth sorting step for Gap1p that may require ubiquitination of Gap1p is entry into the MVE. Before reaching the vacuole, ubiquitinated membrane proteins are delivered to endosomes where multiprotein complexes termed ESCRT-I, II, and III work in a coordinated manner to concentrate cargo into invaginations in the membrane that eventually bud off as vesicles inside of the endosome (Hurley and Emr, 2006). The MVE then fuses with the vacuole, delivering the inwardly budding vesicles and their membrane protein cargo into the lumen of the vacuole where these proteins can be degraded by vacuolar hydrolases. We know that Gap1p follows the ESCRT directed pathway into MVEs, because Gap1p that is delivered to the vacuole appears in the lumen of this organelle rather than the limiting vacuolar membrane, and this delivery requires the function of the ESCRT genes (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006). However, we have not been able to design an explicit test for the need of Gap1p ubiquitination for entry into vesicles, which bud into the interior of the MVE, because Gap1p must be ubiquitinated at either in the Golgi or at the plasma membrane as a prerequisite for delivery to the limiting membrane of the MVE in the first place. Assuming that some form of ubiquitination is necessary for Gap1p entry into inwardly budding MVE vesicles, it appears that the requirements for the type of ubiquitination are not stringent. We have shown here that Gap1p can enter the MVB pathway bearing either poly- or monoubiquitin modification on either lysine 9 or lysine 16. It is also worth noting that deubiquitination of Gap1p does not appear to be necessary for entry into the MVE pathway because a doa4Δ pep4Δ mutant ectopically expressing ubiquitin accumulates copious quantities of polyubiquitinated Gap1p in the vacuolar lumen (Rubio-Texeira and Kaiser, 2006).

There is precedence for alternative forms of ubiquitination of a given protein leading to distinct functional consequences. For example, modification of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) by either monoubiquitination, polyubiquitination, or SUMOlation leads to different activities of PCNA (Prakash et al., 2005). DNA damage induces mono- or polyubiquitination of PCNA, triggering error-prone or error-free translesion DNA synthesis respectively, whereas SUMOlation inhibits DNA repair in the absence of DNA damage (Hoege et al., 2002; Papouli et al., 2005; Pfander et al., 2005). This multifaceted regulation of PCNA function through ubiquitin modification allows coordination of lesion bypass and recombinational repair during DNA synthesis with the extent and duration of DNA damage in the cell.

The different types of Gap1p ubiquitination that occur in the Golgi or the plasma membrane show that the Rsp5p ubiquitin ligase complex catalyzes different types ubiquitination reactions in the context of different organelles. This finding also suggests that the machinery responsible for sorting of Gap1p in the exocytic and endocytic pathways may read different kinds of ubiquitination on Gap1p differently. A more complete understanding of how this emerging ubiquitin code for Gap1p is written and read will depend on identifying components, in addition to Bul1p and Bul2p, that control the organelle specificity the Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase complex activity, as well as the components of the membrane trafficking machinery that sort Gap1p according to the type of ubiquitin modification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Kaiser lab for helpful discussion and encouragement. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM56933 to C.A.K.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0627) on April 23, 2008.

REFERENCES

- Ayscough K. R., Stryker J., Pokala N., Sanders M., Crews P., Drubin D. G. High rates of actin filament turnover in budding yeast and roles for actin in establishment and maintenance of cell polarity revealed using the actin inhibitor latrunculin-A. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137(2):399–416. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E. J., Kaiser C. A. Amino acids regulate the intracellular trafficking of the general amino acid permease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99(23):14837–14842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232591899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne W. E., Magasanik B. Ammonia regulation of amino acid permeases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1983;3(4):672–683. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.4.672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Craene J. O., Soetens O., Andre B. The Npr1 kinase controls biosynthetic and endocytic sorting of the yeast Gap1 permease. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(47):43939–43948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter C., Wieland F. The secretory pathway: mechanisms of protein sorting and transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1286(2):75–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(96)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell S. B., Losko S., Kaiser C. A. Components of a ubiquitin ligase complex specify polyubiquitination and intracellular trafficking of the general amino acid permease. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153(4):649–662. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.4.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L., Riezman H. Ubiquitination of a yeast plasma membrane receptor signals its ligand-stimulated endocytosis. Cell. 1996;84(2):277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80982-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoege C., Pfander B., Moldovan G. L., Pyrowolakis G., Jentsch S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature. 2002;419:135–141. doi: 10.1038/nature00991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe T. Multiubiquitylation by E4 enzymes: ‘one size’ doesn't fit all. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30(4):183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. H., Emr S. D. The ESCRT complexes: structure and mechanism of a membrane-trafficking network. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:277–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser C. A., Chen E. J., Losko S. Subcellular fractionation of secretory organelles. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:325–338. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51855-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann D. J., Babst M., Emr S. D. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell. 2001;106(2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann D. J., Sarkar S., Chu T., Audhya A., Emr S. D. Multivesicular body sorting: ubiquitin ligase Rsp5 is required for the modification and sorting of carboxypeptidase S. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15(2):468–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-07-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolling R., Hollenberg C. P. The ABC-transporter Ste6 accumulates in the plasma membrane in a ubiquitinated form in endocytosis mutants. EMBO J. 1994;13(14):3261–3271. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06627.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laney J. D., Hochstrasser M. Assaying protein ubiquitination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 2002;351:248–257. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)51851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken A. A., Brodsky J. L. Recognition and delivery of ERAD substrates to the proteasome and alternative paths for cell survival. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;300:17–40. doi: 10.1007/3-540-28007-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNatt M. W., McKittrick I., West M., Odorizzi G. Direct binding to Rsp5 mediates ubiquitin-independent sorting of Sna3 via the multivesicular body pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:697–706. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick P., Field C., Schekman R. Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1980;21(1):205–215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papouli E., Chen S., Davies A. A., Huttner D., Krejci L., Sung P., Ulrich H. D. Crosstalk between SUMO and ubiquitin on PCNA is mediated by recruitment of the helicase Srs2p. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Schwartz D., Elias J. E., Thoreen C. C., Cheng D., Marsischky G., Roelofs J., Finley D., Gygi S. P. A proteomics approach to understanding protein ubiquitination. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21(8):921–926. doi: 10.1038/nbt849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfander B., Moldovan G. L., Sacher M., Hoege C., Jentsch S. SUMO-modified PCNA recruits Srs2 to prevent recombination during S phase. Nature. 2005;436:428–433. doi: 10.1038/nature03665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart C. M., Eddins M. J. Ubiquitin: structures, functions, mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695(1–3):55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S., Johnson R. E., Prakash L. Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:317–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puertollano R., Bonifacino J. S. Interactions of GGA3 with the ubiquitin sorting machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6(3):244–251. doi: 10.1038/ncb1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F., Pelham H. R. Sorting of proteins into multivesicular bodies: ubiquitin-dependent and -independent targeting. EMBO J. 2001;20(18):5176–5186. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger A. L., Cain N. E., Chen E. J., Kaiser C. A. Activity-dependent reversible inactivation of the general amino acid permease. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:4411–4419. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberg K. J., Rowley N., Kaiser C. A. Physiological regulation of membrane protein sorting late in the secretory pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137(7):1469–1482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Texeira M., Kaiser C. A. Amino acids regulate retrieval of the yeast general amino acid permease from the vacuolar targeting pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3031–3050. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott P. M., et al. GGA proteins bind ubiquitin to facilitate sorting at the trans-Golgi network. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6(3):252–259. doi: 10.1038/ncb1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevier C. S., Kaiser C. A. Disulfide transfer between two conserved cysteine pairs imparts selectivity to protein oxidation by Ero1. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:2256–2266. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soetens O., De Craene J. O., Andre B. Ubiquitin is required for sorting to the vacuole of the yeast general amino acid permease, Gap1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276(47):43949–43957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbrough M., Rowen D. W., Magasanik B. Role of the GATA factors Gln3p and Nil1p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the expression of nitrogen-regulated genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92(21):9450–9454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub O., Rotin D. Role of ubiquitylation in cellular membrane transport. Physiol. Rev. 2006;86(2):669–707. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrell J., Shih S., Dunn R., Hicke L. A function for monoubiquitination in the internalization of a G protein-coupled receptor. Mol. Cell. 1998;1(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umebayashi K., Nakano A. Ergosterol is required for targeting of tryptophan permease to the yeast plasma membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161(6):1117–1131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walworth N. C., Novick P. J. Purification and characterization of constitutive secretory vesicles from yeast. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105(1):163–174. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]