Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects up to 22% of the general population. Its aetiology remains unclear. Previously reported cross-sectional associations with psychological distress and depression are not fully understood. We hypothesised that psychosocial factors, particularly those associated with somatisation, would act as risk markers for the onset of IBS. We conducted a community-based prospective study of subjects, aged 25–65 years, randomly selected from the registers of three primary care practices. Responses to a detailed questionnaire allowed subjects’ IBS status to be classified using a modified version of the Rome II criteria. The questionnaire also included validated psychosocial instruments. Subjects free of IBS at baseline and eligible for follow-up 15 months later formed the cohort for this analysis (n = 3732). An adjusted participation rate of 71% (n = 2456) was achieved at follow-up. 3.5% (n = 86) of subjects developed IBS. After adjustment for age, gender and baseline abdominal pain status, high levels of illness behaviour (odds ratio (OR) = 5.2; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 2.5–11.0), anxiety (OR = 2.0; 95% CI 0.98–4.1), sleep problems (OR = 1.6; 95% CI 0.8–3.2), and somatic symptoms (OR = 1.6; 95% CI 0.8–2.9) were found to be independent predictors of IBS onset. This study has demonstrated that psychosocial factors indicative of the process of somatisation are independent risk markers for the development of IBS in a group of subjects previously free of IBS. Similar relationships are observed in other “functional” disorders, further supporting the hypothesis that they have similar aetiologies.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, IBS, Psychosocial, Risk factors, Prospective, Population-based

1. Introduction

The term functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders (FGIDs) describes a group of syndromes related to the GI tract but for which no structural cause has been identified [34]. FGIDs are common both in community and clinic populations [5,18,24]. One of the common FGID symptoms is pain [11,34]. Two recent studies reported similar 12-month prevalence rates of self-reported abdominal pain of 4–5% [11,17].

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which has abdominal pain as its cardinal symptom, is one of the most common FGIDs. It has an estimated prevalence of 8–22% in the general population [14,27,33]. A number of biological triggers for the onset of IBS have been proposed, including bacterial gastroenteritis [25] and alterations of gut microflora [21,29]. However, psychosocial factors are also thought to play an important role and may act as markers of IBS onset, in particular those associated with the process of somatisation, defined as the manifestation of psychological symptoms as bodily disorders [16]. A number of studies have investigated the relationship between psychosocial factors and IBS; two of the most recent showing that subjects with IBS have higher levels of depression, anxiety and neuroticism, compared with subjects free of IBS [18,20]. An association between psychological distress and consulting a physician with IBS symptoms has also been demonstrated [6,30,36]. However it is not known whether psychological distress and other psychosocial factors act as risk markers for IBS onset or are merely associated with the presence of IBS symptoms. In order to elucidate this temporal relationship prospective studies are essential.

The aim of the current study was to test the hypothesis that among a group of subjects free of IBS, psychosocial markers, particularly those associated with the process of somatisation, would predict the onset of IBS at follow-up.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a prospective population-based postal survey that ascertained at baseline participants’ psychosocial status and identified abdominal symptoms using a modified version of the Rome II criteria for IBS [4]. After 15 months all eligible subjects (those who provided full information and agreed to further contact at baseline) who were free of IBS at baseline were followed up with a further postal survey. Methods for recording and classifying IBS were identical to the baseline survey, as was the mailing strategy. Participants reporting IBS at follow-up were identified.

2.2. Study subjects

Individuals aged between 25 and 65 years were randomly selected from the population-based registers of three general practices in socio-economically diverse areas of North West England.

2.3. Baseline questionnaire

All subjects were mailed a full baseline questionnaire. The Rome II criteria for classifying IBS [4], of which we used a modified version, are widely used in both clinic and general population settings to classify IBS [28]. We asked participants to recall any abdominal pain, in the past month rather than over the past year as in the original Rome II criteria, in order to reduce the inaccurate recall that has previously been demonstrated over a 12-month period [19]. Participants were classified as having IBS if they reported having experienced abdominal pain (as described above) and in addition answered yes to at least two of the following questions: (1) “Was your abdominal pain or discomfort relieved by opening your bowels?” (2) “During the past month have you had fewer than three bowel movements a week OR more than three bowel movements a day?” (3) “During the past month have you had hard or lumpy stools OR loose or watery stools?” Subjects free of IBS were sub-classified into one of two groups depending on their abdominal pain status: abdominal pain free or abdominal pain.

An intensive mailing strategy was used to boost response rates. At each stage subjects were free to refuse participation. The remaining non-responders were contacted at 2-week intervals over an 8-week period, correspondence involved a reminder postcard to complete the first questionnaire, followed by a mailed second full questionnaire to the non-responders. For those still not responding a short (two page) questionnaire followed, if necessary, by a short telephone questionnaire, and used to characterise any potential non-response bias. The current analysis uses data from the full detailed questionnaire only.

The full baseline questionnaire also included measures of psychosocial status. These measures were:

2.3.1. Estimation of Sleep Problems Scale [13]

This is a validated 4-item scale used to assess recent problems with sleep. Each item is scored in a range of 0–5, giving a total score of between 0 and 20.

2.3.2. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) [7]

This 12-item version of the GHQ measures levels of psychological distress and has been widely used for previous population-based studies [22]. Each item has four possible responses, for scoring purposes these are dichotomised (0 or 1) and the 12 scores added together to give a total GHQ score between 0 and 12. Higher total scores indicate higher levels of psychological distress.

2.3.3. Somatic Symptoms Checklist [26]

This checklist was originally developed and validated as a screening test for somatisation disorder. It contains six basic items regarding lifetime history of symptoms; troubled breathing, frequent pain in fingers or toes, frequent vomiting (when not pregnant), loss of voice, loss of memory and difficulty swallowing. A further 7th item, frequent trouble with menstrual cramps, is included for female participants. However, to avoid spurious associations with the onset of IBS this question was not included in the total score. A second question, “Have you ever had difficulties swallowing or had an uncomfortable lump in your throat that stayed with you for at least an hour?”, was also excluded from the analysis due to a high proportion of missing answers. The total score therefore ranged between 0 and 5 for both males and females.

2.3.4. The Illness Attitudes Scales (IAS) [15]

The IAS measure two particular dimensions, “Health Anxiety” and “Illness Behaviour” [31]. The “Health Anxiety” subscale consists of 11 items (such as “Are you worried that you may get a serious illness in the future?”) and has a total score between 0 and 44, with a general population mean score of 9.1 (standard deviation 6.9). The “Illness Behaviour” subscale consists of six items (such as “How often do you see a doctor?”) and has a total score between 0 and 24, with a general population mean score of 4.7 (standard deviation 4.2).

2.3.5. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) [37]

The HAD scale measures levels of anxiety and depression and concentrates on symptoms experienced in the past week. The 14 items are coded on a 0–3 Likert scale, and anxiety and depression scores are totalled separately. Scores on each subscale of 10–11 represent a high probability of an anxiety or depression disorder being present.

2.3.6. Threatening life events [3]

The 12 items in this inventory gather information on adverse life events experienced within the previous 6 months. The events are associated with a significant long-term contextual threat rating and include questions on personal relationships, employment, illness, and financial and legal problems. It is a modified version of Tennant and Andrew’s 67-item life events inventory [35]. The total score of between 0 and 12 is representative of the number of events experienced.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Those subjects who provided complete data at baseline and follow-up were included in the analysis. For each of the psychological measures, based upon the distribution, participants’ scores were categorised into thirds. This method accounts for the non-Gaussian distribution of these scores. The association between being in the middle or highest third compared to the lowest third (referent group) of the psychosocial scale scores and the onset of IBS was examined using logistic regression. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All factors found to be associated (statistically significant association, or OR < 0.67 or OR ⩾ 1.5 [12]) with the onset of IBS in the univariate model were entered into a multivariate model. This enabled us to examine the relative contribution of these factors to the development of IBS. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were adjusted for age and gender. The multivariate model was also adjusted for baseline abdominal pain status.

To examine the performance of the final model we examined the (1) multiplicative and (2) additive effects of the risk markers we had identified as important predictors of outcome. All factors that remained strong independent predictors in the multivariate model were dichotomised (0 or 1) at the point where an increased risk of the onset of IBS was observed. We then explored whether there were any interactive effects, over and above the individual contributions, of those factors and the onset of IBS. To explore the additive effects of the important variables we explored whether the risk of new IBS increased as the number of factors subjects were exposed to at baseline increased. The analyses of model performance were adjusted for age, gender and baseline abdominal pain status. All statistical analyses were carried out using the STATA statistical software package [32].

This study received ethical approval from both the South Manchester and East Cheshire Local Research Ethics Committees.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline data

A total of 6094 subjects provided complete information on IBS status, of who 14% (n = 844) had IBS and 86% (n = 5250) were free of IBS.

3.2. Follow-up response rates and study subjects

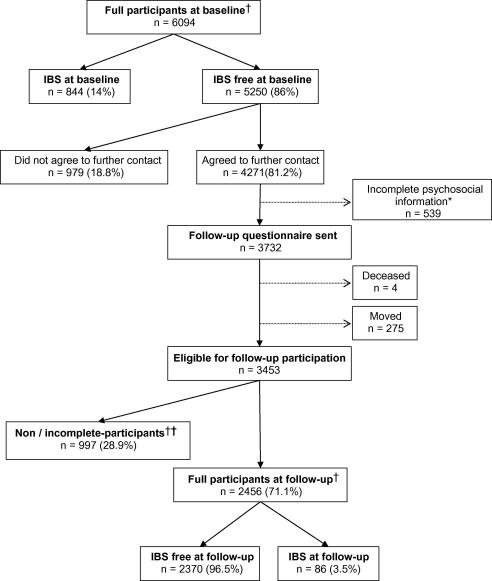

Of the 5250 subjects free of IBS at baseline 3732 were eligible for follow-up 15 months later (see Fig. 1). After adjusting for those who had moved or died (n = 279), 83% of subjects participated at follow-up and 2456 (71%) provided complete follow-up information that allowed us to classify their IBS status.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study participation. ∗Incomplete psychosocial information at baseline = not eligible for participation in follow-up. †Full participants are those who completed a long questionnaire and provided complete data at follow-up. †† Breakdown of non/incomplete participants at follow-up: unable to classify due to incomplete data or completion of a short or telephone questionnaire n = 403, non-participants n = 594.

3.3. Prevalence of IBS at follow-up

As shown in Table 1, of the 2456 who were free of IBS at baseline and on whom we had complete follow-up information, 86 subjects reported IBS (prevalence 3.5%) at follow-up. The onset rate of IBS was significantly higher in both women (4.6% compared to 2.1% in men; χ2 test for difference p < 0.01) and younger subjects (median age of 44.1 years compared to 47.7 years; p = 0.01). Of all subjects who were free of IBS at baseline 327 (13.3%) reported having abdominal pain. The rate of new IBS at follow up was higher among subjects with some abdominal pain (n = 25, 7.6%) when compared to those with no abdominal pain (n = 61, 2.9%).

Table 1.

Baseline measures and IBS status of full participants at follow-up

| IBS free at FU (n = 2370) |

IBS at FU (n = 86) |

p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1069 | 97.9 | 23 | 2.1 | <0.01 |

| Female | 1301 | 95.4 | 63 | 4.6 | |

| Total | 2370 | 86 | |||

| Median |

95% CI |

Median |

95% CI |

||

| Age | 47.7 | 47.0–48.4 | 44.1 | 39.4–47.2 | 0.01 |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

| Baseline APb status | |||||

| AP free | 2068 | 97.1 | 61 | 2.9 | <0.01 |

| AP | 302 | 92.4 | 25 | 7.6 | |

| Total | 2370 | 86 | |||

| Median |

95% CI |

Median |

95% CI |

||

| Psychosocial scales | |||||

| Sleep problems | 5 | 4–5 | 8 | 6–9 | <0.01 |

| GHQ | 0 | 0–0 | 1.5 | 0–2.6 | <0.01 |

| Somatic Symptoms | 0 | 0–0 | 1 | 1–1 | <0.01 |

| Health Anxiety | 9 | 8–9 | 11 | 8–14 | 0.01 |

| Illness Behaviour | 4 | 4–4 | 8 | 6–8 | <0.01 |

| HAD Anxiety | 5 | 5–5 | 8 | 6–9 | <0.01 |

| HAD Depression | 2 | 2–3 | 4 | 3–5 | <0.01 |

| Life Eventsc | 0 | 0–1 | 1 | 0–1 | 0.01 |

All values are by Mann–Whitney U test except gender and baseline abdominal pain status, which were by χ2 test.

AP, abdominal pain.

Life events score for 6 months prior to completion of the follow-up questionnaire.

3.4. Psychosocial factors as predictors of the onset of IBS

Scores on each of the baseline psychosocial measures were higher, reflecting a poorer psychosocial state, in those who reported IBS at follow-up compared to those who remained symptom free (Table 1). When we quantified those relationships using logistic regression (Table 2) we found that, in univariate analysis adjusted for age and gender, participants scoring in the highest third of the Illness Behaviour Scale were seven times more likely to develop IBS, whilst scoring in the top-third of the Estimation of Sleep Problems and HAD Anxiety scales were associated with a threefold increase and the Somatic Symptom Checklist with over a 2-fold increase, in the risk of developing IBS. Being in the highest third of the GHQ, Health Anxiety, HAD Depression and Threatening Life Event scales were also associated with reporting IBS at follow-up. In addition, those subjects who reported abdominal pain at baseline were 2.6 times (OR = 2.59; 95% CI 1.6–4.2) more likely to develop IBS at follow-up. Since having some abdominal pain at baseline may act to confound the relationship between psychosocial factors and IBS at follow up we adjusted for this factor in subsequent analyses.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of baseline psychosocial measures and new onset IBS at follow-up

| Factor | Category | IBS free (n = 2370) |

IBS (n = 86) |

Univariatec |

Multivariated |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Potential confounding factors | |||||||||

| Gender | Male | 1069 | 45.1 | 23 | 26.7 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| Female | 1301 | 54.9 | 63 | 73.3 | 1.97 | 1.3–3.1 | 1.55 | 0.9–2.6 | |

| Age (years) | 25–39 | 659 | 27.8 | 35 | 40.7 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 40–52 | 824 | 34.8 | 31 | 36.1 | 0.80 | 0.5–1.3 | 0.72 | 0.4–1.2 | |

| 53–65 | 887 | 37.4 | 20 | 23.3 | 0.54 | 0.3–0.9 | 0.40 | 0.2–0.7 | |

| Baseline APa status | AP free | 2068 | 87.3 | 61 | 70.9 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| AP | 302 | 12.7 | 25 | 29.1 | 2.59 | 1.6–4.2 | 1.89 | 1.2–3.2 | |

| Psychosocial Scales | |||||||||

| GHQ | 0 | 1348 | 56.9 | 37 | 43.0 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 1–2 | 453 | 19.1 | 15 | 17.5 | 1.14 | 0.6–2.1 | 0.80 | 0.4–1.6 | |

| 3–12 | 569 | 24.0 | 34 | 39.5 | 2.03 | 1.3–3.3 | 0.83 | 0.4–1.6 | |

| Sleep Problems | 0–3 | 950 | 40.1 | 17 | 19.8 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 4–8 | 779 | 32.9 | 31 | 36.0 | 2.01 | 1.1–3.7 | 1.44 | 0.7–2.8 | |

| 9–20 | 641 | 27.0 | 38 | 44.2 | 3.09 | 1.7–5.5 | 1.59 | 0.8–3.2 | |

| Somatic Symptoms | 0 | 1328 | 56.0 | 29 | 33.7 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 1 | 697 | 29.4 | 35 | 40.7 | 2.03 | 1.2–3.4 | 1.53 | 0.9–2.6 | |

| 2–5 | 345 | 14.6 | 22 | 25.6 | 2.60 | 1.5–4.7 | 1.56 | 0.8–2.9 | |

| Health Anxiety | 0–6 | 890 | 37.6 | 29 | 33.7 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 7–13 | 832 | 35.1 | 21 | 24.4 | 0.76 | 0.4–1.4 | 0.55 | 0.3–1.02 | |

| 14–44 | 648 | 27.3 | 36 | 41.9 | 1.70 | 1.0–2.8 | 0.80 | 0.4–1.5 | |

| Illness Behaviour | 0–3 | 996 | 42.0 | 12 | 14.0 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 4–7 | 856 | 36.1 | 29 | 33.7 | 2.73 | 1.4–5.4 | 2.56 | 1.2–5.3 | |

| 8–24 | 518 | 21.9 | 45 | 52.3 | 7.41 | 3.9–14.2 | 5.22 | 2.5–11.0 | |

| HAD Anxiety | 0–4 | 1006 | 45.0 | 23 | 26.7 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 5–7 | 667 | 28.1 | 17 | 19.8 | 1.11 | 0.6–2.1 | 0.96 | 0.5–1.9 | |

| 8–21 | 637 | 26.9 | 46 | 53.5 | 3.01 | 1.8–5.0 | 2.00 | 0.98–4.1 | |

| HAD Depression | 0–2 | 1203 | 50.8 | 32 | 37.2 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 3–5 | 659 | 27.8 | 22 | 25.6 | 1.31 | 0.8–2.3 | 0.83 | 0.4–1.6 | |

| 6–21 | 508 | 21.4 | 32 | 37.2 | 2.35 | 1.4–3.9 | 0.73 | 0.4–1.5 | |

| Life Eventsb | 0 | 1165 | 50.6 | 33 | 40.2 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – |

| 1 | 624 | 27.1 | 18 | 22.0 | 0.99 | 0.6–1.8 | 0.82 | 0.4–1.5 | |

| 2–9 | 514 | 22.3 | 31 | 37.8 | 1.96 | 1.2–3.2 | 1.21 | 0.7–2.1 | |

Note: missing data (n = 71) are not included in this analysis.

AP, abdominal pain.

Life events during the 6 months prior to completion of the follow-up questionnaire.

All univariate models are adjusted for age and gender.

The multivariate model includes all variables.

In multivariate analysis (Table 2) subjects reporting higher levels of somatic symptoms, sleep problems and anxiety (as measured by the HAD scale) at baseline had an increased odds of reporting IBS at follow-up. However, the confidence intervals around these estimates included unity, although they approached significance. A high score on the Illness Behaviour Scale remained the best predictor of outcome.

3.5. Model assessment

We then examined the risk of developing IBS by a combination of one or more of the associated psychosocial risk markers (scoring in the highest third of the HAD Anxiety Scale and Estimated Sleep Problems Scale and in the highest two-thirds of the Somatic Symptoms Checklist and Illness Behaviour Scale). First we explored whether these variables interacted with each other in predicting outcome. No interactive effects were observed (e.g. illness behaviour and sleep: OR = 0.69; 95% CI 0.2–2.5). We then examined the additive effects of these variables. In this analysis of those subjects exposed to none of the risk markers (n = 534) only one subject (1.2%) reported IBS at follow-up. We therefore classified subjects exposed to none or one of these factors as the referent group. We observed a linear increase in the odds of developing IBS with increasing number of factors subjects were exposed to at baseline (see Table 3). Indeed, exposure to two or more of those factors identified 80.2% (n = 69) of all subjects reporting IBS at follow-up.

Table 3.

Additive effects of psychosocial risk markers in the onset of IBS

| Number of factorsb | Group size | New IBS |

ORa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||||

| 0 | 534 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | – |

| 1 | 70 | 16 | 18.6 | ||

| 2 | 637 | 25 | 29.0 | 2.59 | 1.4–4.9 |

| 3 | 402 | 27 | 31.4 | 4.43 | 2.4–8.3 |

| 4 | 182 | 17 | 19.8 | 6.33 | 3.1–13.0 |

All values are adjusted for age, gender and baseline abdominal pain status.

Scoring in the highest third of the HAD Anxiety Scale and Estimated Sleep Problems Scale and in the highest two-thirds of the Somatic Symptoms Checklist and Illness Behaviour Scale.

3.6. Methodological issues

We were concerned with the possible effects of non-participation bias on our results. Table 4 compares the baseline characteristics of all full participants (n = 2456) with all non-participants (n = 1976). The non-participants were those subjects who had returned a baseline questionnaire but who refused further contact (n = 979) and those who were non/incomplete participants at follow-up (n = 997) (see Fig. 1). Non-participants were more likely to be younger males. In addition they had significantly different HAD depression (p = 0.01) and illness behaviour scores (p = 0.03) although no differences were observed in baseline abdominal pain status between the two groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of baseline measures between non-participantsa and full-participants at follow-up

| Non-participantsa (n = 1976) |

Full participants (n = 2456) |

P-valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 934 | 47.3 | 1092 | 44.5 | 0.06 |

| Female | 1042 | 52.7 | 1364 | 55.5 | |

| Total | 1976 | 100 | 2456 | 100 | |

| Median |

95% CI |

Median |

95% CI |

||

| Age | 44.3 | 43.6–45.2 | 47.6 | 46.9–48.3 | <0.01 |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

| Baseline APc status | |||||

| AP free | 1698 | 85.9 | 2129 | 86.7 | 0.47 |

| AP | 278 | 14.1 | 327 | 13.3 | |

| Total | 997 | 100 | 2456 | 100 | |

| Median |

95% CI |

Median |

95% CI |

||

| Psychological scales | |||||

| Sleep Problems | 5 | 4–5 | 5 | 4–5 | 0.20 |

| GHQ | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0.36 |

| Somatic Symptoms | 0 | 0–0 | 0 | 0–0 | 0.14 |

| Health Anxiety | 9 | 8–9 | 9 | 8–9 | 0.75 |

| Illness Behaviour | 4 | 4–4 | 4 | 4–4 | 0.03 |

| HAD Anxiety | 5 | 5–5 | 5 | 5–5 | 0.12 |

| HAD Depression | 3 | 2–3 | 2 | 2–3 | 0.01 |

| Life Eventsd | 1 | 0–1 | 1 | 1–1 | 0.07 |

Non-participants include subjects who did not agree to further contact at baseline (n = 979) and those who were non/incomplete responders at follow-up (n = 997).

All values are by Mann–Whitney U test except gender baseline abdominal pain status, which are by χ2 test.

AP, abdominal pain.

Life events during the 6 months prior to completion of the baseline questionnaire.

4. Discussion

We have conducted a prospective study among subjects free of IBS, the first to have specifically considered psychosocial risk markers for the onset of IBS in a community sample. Individuals in the oldest age group were significantly less likely to develop IBS at follow-up. After adjustment for age we have shown that high levels of illness behaviour, somatic symptoms, sleep problems, anxiety, depression, psychological distress, and health anxiety predicted the onset of IBS. Those who reported all four of these markers at baseline were six times more likely to report IBS when compared to those who were exposed to none or one marker. Due to the episodic nature of IBS it is unclear whether we have identified the ”first ever (incident)” or “new (recurring)” episodes of the disorder, and we are unable to determine this in the current study. Nevertheless we have demonstrated that among subjects free of IBS at the time of assessment, psychosocial factors are strong predictors of developing IBS 15-months later.

When interpreting our results it is important to consider a number of methodological issues. First, measurement of psychosocial markers was by standardised, well-validated scales. Any misclassification with respect to these is likely to be random and independent of the outcome. Since such misclassification would make a relationship more difficult to observe any reported relationships are probably underestimates rather than overestimates.

Second, the overall population prevalence of FGIDs, including IBS, is relatively stable over 12–20 months but the actual individuals suffering at any particular time point may vary due to the combination of both the onset and resolution of symptoms [33]. Due to this fluctuating nature of the disorder it is probable that some participants’ symptoms will have resolved in the intervening 15 months between baseline and follow-up. We will therefore not have ascertained the complete IBS case-load at follow-up. However this is unlikely to have any impact on the internal comparisons between psychosocial exposures and symptom onset 15 months later.

Third, non-participation bias must be considered. We had complete information on 71% of those baseline participants eligible for follow-up. However we were concerned about the effects of subjects who either refused further contact at baseline or those who were non/incomplete responders at follow-up. Since the only conceptual difference between these two groups is the time of refusal we grouped them together as “non-participants”. Non-participants were more likely to be younger males, to have higher scores on the HAD Depression scale, and lower scores in the illness behaviour scale. The illness behaviour scale was the strongest predictor of outcome. For this to impact on the current findings we would have to hypothesise that the relationship between illness behaviour scores and the onset of IBS was different among those who did and did not participate. That seems unlikely. However, we may have overestimated the prevalence of new IBS. If we assume all non-participants would have remained symptom free at follow-up we would have found a minimum prevalence of 1.9% (95% CI 1.6–2.3).

Finally, three out of four (Somatic Symptoms Checklist, Estimated Sleep Problems and HAD Anxiety scales) of the factors identified in the multivariate analysis had confidence intervals that approach significance, but that include unity. However, as reported in this manuscript the best estimate from the available data indicated that these factors contributed to the outcome. We therefore included these factors in our final model.

Our results are supported by a previous finding from this research group that reported high scores on the illness behaviour scale and GHQ to be strong risk markers for the onset of abdominal pain [11]. However, we have gone further in this study by investigating a more homogeneous population, using a clinically meaningful definition (i.e. strict criteria for IBS rather than more general abdominal pain), and using a range of markers of distress. In the current study general psychological distress (measured by the GHQ) was associated with the outcome. However this relationship was explained by other markers of psychological distress in the multivariate model. Since abdominal pain is also strongly associated with psychosocial status it may act as a confounder in the relationship between psychosocial status and the onset of IBS. In this study our aim was to examine psychosocial factors as risk markers for the onset of IBS and we therefore adjusted for the potential confounding effect of abdominal pain. This allowed us to consider the effect of psychosocial exposures on the onset of IBS, independent of prior abdominal pain status. Both high levels of illness behaviour and reporting a greater number of somatic symptoms are indicative of the process of somatisation. Research into other chronic unexplained pain syndromes, in particular chronic widespread pain (CWP), has reported similar risk markers for symptom onset [22]. In addition to having similar risk markers, as might be expected, it has been demonstrated that these disorders co-occur in the general population. One recent study reported that in a sample of 587 subjects, 27% were found to have one or more of IBS, CWP, chronic orofacial pain and chronic fatigue, and 1% was reported to have all four [1]. As this was a cross-sectional study the authors were unable to consider the aetiology of these syndromes; however they did examine common factors across the disorders and reported that high levels of health anxiety, somatic symptoms and recent adverse life events were common to all. A second study [8] lends further support to the existence of overlap of IBS with other functional disorders; in a group of subjects with chronic fatigue syndrome a point prevalence of IBS was reported to be 63%. The point prevalence of CWP amongst the group of subjects with IBS in our study was 33% (n = 28) and one could hypothesise that the relationships we have observed are with CWP. Although the numbers are small we repeated the multivariate analysis stratified by the presence of CWP at follow-up. In those who did not have co-occurring CWP the results were similar to those reported here for the onset of IBS. However, depression and threatening life events were additional markers for predicting those subjects who reported both IBS and CWP at follow-up.

Why psychosocial risk markers manifest in somatic symptoms is unclear. It is likely that specific biological mechanisms moderate the relationships between these markers and symptom onset. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (the predominant stress–response axis of the body) has been shown to be associated with the onset of CWP [23]. The HPA axis has many functions and is intimately linked with pain. Clinic studies have suggested that the HPA axis may also be altered in patients with IBS and other FGIDs [2]. Whether these alterations are a consequence of having IBS or precede the onset of symptoms is unclear and requires further investigation. Other studies have demonstrated that psychological factors are important predictors in the development of IBS following a diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis [9,10]. We have added to these reports by providing evidence for a role of psychosocial factors in the onset of IBS in the general population setting, whether different mechanisms underlie these subgroups of IBS remains to be clarified.

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated that in a group of subjects free of IBS the reporting of higher levels of somatic symptoms, illness behaviour, sleep problems and anxiety are independent predictors of IBS onset. In order to develop treatment and prevention strategies future work is needed that can explain how these psychosocial markers result in IBS.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Arthritis Research Campaign, Chesterfield, UK (Grant Ref. No. 17552). The authors thank the doctors, staff and participants at the three general practices in the South Manchester and Cheshire areas for their help and participation in the study. Thanks also to Professor Alan Silman for his helpful comments on early drafts of the manuscript and to Karen Schafheutle, Stewart Taylor and Richard Jones for data collection and administration.

References

- 1.Aggarwal V.R., McBeth J., Zakrzewska J.M., Lunt M., Macfarlane G.J. The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have common associated factors? Int J Epidemiol. 2005 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohmelt A.H., Nater U.M., Franke S., Hellhammer D.H., Ehlert U. Basal and stimulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders and healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:288–294. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000157064.72831.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugha T., Bebbington P., Tennant C., Hurry J. The List of Threatening Experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychol Med. 1985;15:189–194. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002105x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossman D.A., Carazziari E., Talley N.J. Rome II: a multinational consensus document on functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut. 1999;45:II1–II81. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drossman D.A., Li Z., Andruzzi E., Temple R.D., Talley N.J., Thompson W.G. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Digest Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drossman D.A., McKee D.C., Sandler R.S., Mitchell C.M., Cramer E.M., Lowman B.C. Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome. A multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:701–708. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg DP, Williams P. A user’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: Nfer-Nelson; 1988.

- 8.Gomborone J.E., Gorard D.A., Dewsnap P.A., Libby G.W., Farthing M.J. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in chronic fatigue. J R College Phys Lond. 1996;30:512–513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gwee K.A., Graham J.C., McKendrick M.W., Collins S.M., Marshall J.S., Walters S.J. Psychometric scores and persistence of irritable bowel after infectious diarrhoea. Lancet. 1996;347:150–153. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gwee K.A., Leong Y.L., Graham C., McKendrick M.W., Collins S.M., Walters S.J. The role of psychological and biological factors in postinfective gut dysfunction. Gut. 1999;44:400–406. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halder S.L., McBeth J., Silman A.J., Thompson D.G., Macfarlane G.J. Psychosocial risk factors for the onset of abdominal pain. Results from a large prospective population-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1219–1225. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harkness E.F., Macfarlane G.J., Nahit E.S., Silman A.J., McBeth J. Mechanical injury and psychosocial factors in the work place predict the onset of widespread body pain: a two-year prospective study among cohorts of newly employed workers. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1655–1664. doi: 10.1002/art.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins C.D., Stanton B.A., Niemcryk S.J., Rose R.M. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:313–321. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones R., Lydeard S. Irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. Br Med J. 1992;304:87–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6819.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kellner R. Abridged manual of the illness attitude scale. New Mexico: Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University of New Mexico; 1987.

- 16.Kleinman A., Kleinman J. Somatisation: the interconnectedness in Chinese society among culture, depressive experiences and meaning of pain. In: Kleinman A., editor. Culture and depression. Studies in the anthropology of cross culture psychiatry of affect and disorder. University of California Press; London: 1985. pp. 429–490. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koloski N.A., Talley N.J., Boyce P.M. Does psychological distress modulate functional gastrointestinal symptoms and health care seeking? A prospective, community Cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:789–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koloski N.A., Talley N.J., Boyce P.M. Epidemiology and health care seeking in the functional GI disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2290–2299. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linton S.J., Gotestam K.G. A clinical comparison of two pain scales: correlation, remembering chronic pain, and a measure of compliance. Pain. 1983;17:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locke G.R., III, Weaver A.L., Melton L.J., III, Talley N.J. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malinen E., Rinttila T., Kajander K., Matto J., Kassinen A., Krogius L. Analysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCR. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:373–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McBeth J., Macfarlane G.J., Benjamin S., Silman A.J. Features of somatization predict the onset of chronic widespread pain: results of a large population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:940–946. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<940::AID-ANR151>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McBeth J., Silman A.J., Gupta A., Chiu Y.H., Ray D., Morriss R. Moderation of psychosocial risk factors through dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis in the onset of chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain: findings of a population-based prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:360–371. doi: 10.1002/art.22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell C.M., Drossman D.A. Survey of the AGA membership relating to patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1282–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(87)91099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neal K.R., Hebden J., Spiller R. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms six months after bacterial gastroenteritis and risk factors for development of the irritable bowel syndrome: postal survey of patients. BMJ. 1997;314:779–782. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7083.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Othmer E., DeSouza C. A screening test for somatization disorder (hysteria) Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:1146–1149. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.10.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saito Y.A., Locke G.R., Talley N.J., Zinsmeister A.R., Fett S.L., Melton L.J., III A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816–2824. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saito Y.A., Talley N.J., Melton J., Fett S., Zinsmeister A.R., Locke G.R. The effect of new diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome on community prevalence estimates. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:687–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1350-1925.2003.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Si J.M., Yu Y.C., Fan Y.J., Chen S.J. Intestinal microecology and quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1802–1805. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i12.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith R.C., Greenbaum D.S., Vancouver J.B., Henry R.C., Reinhart M.A., Greenbaum R.B. Psychosocial factors are associated with health care seeking rather than diagnosis in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:293–301. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90817-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Speckens A.E., Spinhoven P., Sloekers P.P.A., Bolk J.H., van Hemert A.M. A validation study of the Whitely Index, the Illness Attitude Scales, and the Somatosensory Amplification Scale in general medical and general practice patients. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:95–104. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00561-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stata Statistical Software. Stata (Release 8.0). TX: Stata Corporation; 2003.

- 33.Talley N.J., Weaver A.L., Zinsmeister A.R., Melton L.J., III Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165–177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talley N.J., Zinmeister A.R., van Dyke C. Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:927. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tennant C., Andrews G. A scale to measure the stress of life events. Aust NZ J Psychiat. 1976;10:27–32. doi: 10.3109/00048677609159482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehead W.E., Bosmajian L., Zonderman A.B., Costa P.T., Schuster M.M. Symptoms of psychological distress associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:709–714. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]