Abstract

Long-term GABAA receptor alterations occur in hippocampal dentate granule neurons of rats that develop epilepsy after status epilepticus in adulthood. Hippocampal GABAA receptor expression undergoes marked reorganization during the postnatal period, however, and the effects of neonatal status epilepticus on subsequent GABAA receptor development are unknown. In the current study, we utilize single cell electrophysiology and antisense mRNA amplification to determine the effect of status-epilepticus induced by lithium-pilocarpine in postnatal day 10 rat pups on GABAA receptor subunit expression and function in hippocampal dentate granule neurons. We find that rats subjected to lithium-pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus at postnatal day 10 show long-term GABAA receptor changes including a two-fold increase in α1 subunit expression (compared with lithium-injected controls) and enhanced type I benzodiazepine augmentation that are opposite of those seen after status epilepticus in adulthood and may serve to enhance dentate gyrus inhibition. Further, unlike adult rats, postnatal day 10 rats subjected to status epilepticus do not become epileptic. These findings suggest age-dependent differences in the effects of status epilepticus on hippocampal GABAA receptors that could contribute to the selective resistance of the immature brain to epileptogenesis.

Keywords: epilepsy, seizure, developing brain, dentate gyrus, benzodiazepine, mRNA amplification

GABAA receptors (GABARs) are heteromeric protein complexes that mediate most fast synaptic inhibition in fore-brain. Many distinct subunit subtypes exist, and their distribution varies in a regional and cell type-specific manner (Wisden et al., 1992; Sperk et al., 1997; Barnard et al., 1998). GABARs can be assembled in different subunit combinations to produce a variety of different receptor compositions, pharmacological profiles, and intrinsic receptor characteristics (Pritchett et al., 1989; Sieghart, 1995; Barnard et al., 1998). Adult rats that develop epilepsy following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (SE) and adult patients with refractory temporal lobe epilepsy demonstrate marked alterations in GABAR properties in hippocampal dentate granule neurons (DGNs; Buhl et al., 1996; Gibbs et al., 1997; Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998, 1999). GABAR subunit expression in DGNs vary during early postnatal development (Laurie et al., 1992; Fritschy et al., 1994; Brooks-Kayal et al., 2001), however, and the effects of neonatal SE on GABARs is not known. Here we examine the effect of SE in postnatal day 10 (P10) rat pups on subsequent GABAR development in DGN and find increased α1 subunit expression and type I benzodiazepine augmentation when the rats reach adulthood. These findings are opposite of those seen after SE in adulthood and could contribute to the selective resistance of the immature brain to epileptogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Lithium-pilocarpine injections

All studies were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and with the approval of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Animal Care and Use Committee. Maximum care was taken to minimize the number of animals used and to minimize their suffering. At P9 Sprague–Dawley rat pups were injected i.p. with either lithium chloride (3 mEq/kg; P10-SE and lithium-control groups) or saline (saline controls). On P10, pups received i.p. injection of either 60 mg/kg pilocarpine (P10-SE group) or saline (lithium and saline control groups). Pups uniformly developed SE within 30 min of pilocarpine injection and seizures continued intermittently for 5– 6 h. A separate set of pups (naive controls) received no injections and was not separated from mother until weaning at P21.

Video and EEG monitoring

As adults (P90 or older) the rats that had SE at P10 were video recorded for 24 h/day for 14 days (n=6) for any discrete alterations in behavior such as wild running, head bobbing, facial clonus, forelimb clonus, or tail stiffening that might indicate behavioral seizures. Three of the adult P10-SE rats that were video monitored were also implanted with electrodes in CA1 and frontal cortex and were video-EEG monitored using previously published methods (Raol et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004).

Isolation of neurons

DGNs were acutely isolated from hippocampal slices using our previously published protocol (Hsu et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2004). DGNs were identified based on their size (approximately 10 μm) and characteristic morphology (oval cell body with a single neuronal process).

Electrophysiology

Recordings were made using the whole cell patch clamp technique as described previously (Hsu et al., 2003). GABA-elicited current was recorded at room temperature. Neurons were voltage-clamped at −20 mV and signals were amplified and saved at 10 kHz using pClamp 8.01 software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) for off-line analysis. Curves were fitted using the Marquardt-Levenberg nonlinear least-squares algorithm.

RNA measurement

Relative expression of GABAR mRNAs within individual acutely isolated DGNs were measured using antisense RNA amplification and reverse northern blotting as previously described in detail (Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998, 1999). The relative abundance of total GABAR subunit mRNA was calculated as the sum of the hybridization signal for all subunit cDNAs on the blot for each cell divided by the hybridization signal for β-actin cDNA on that blot. The effect of group on the various outcomes as measured repeatedly across different cells was analyzed using a longitudinal mixed effects model (SAS Proc Mixed models; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) which accounts for potential within-subject correlation associated with making repeated measures from individual animals.

Timm’s and Cresyl Violet staining

The staining was performed using previously published methods (Sloviter, 1982; Raol et al., 2003).

RESULTS

Rats do not become epileptic after SE at postnatal day 10 (P10-SE)

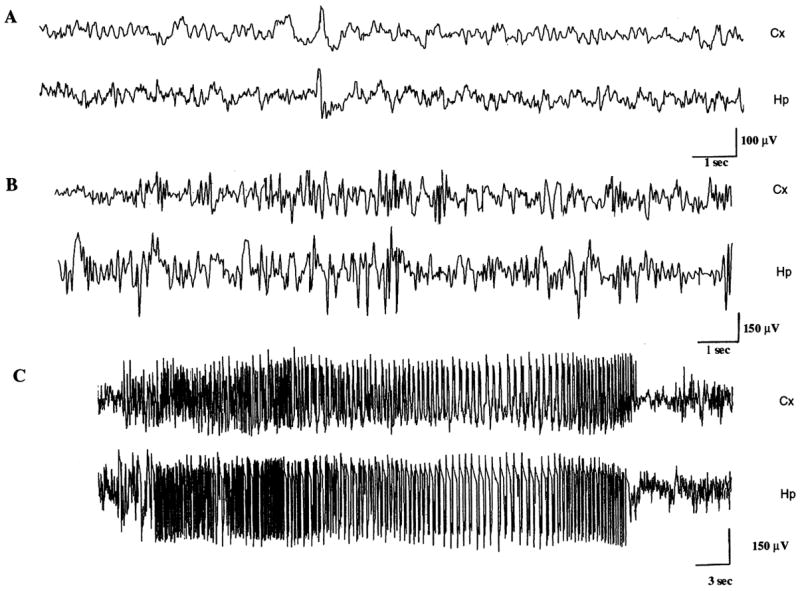

No evidence of behavioral or electrographic seizures was seen during prolonged video and EEG monitoring of adult animals previously subjected to P10-SE (Fig. 1A). Further no interictal epileptiform abnormalities were found in any of the P10-SE animals. This contrasted markedly to the uniform development of spontaneous seizures in adult rats subjected to SE (Fig. 1B, C; see also Gibbs et al., 1997; Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998). No hippocampal cell loss or mossy fiber sprouting was visualized using light microscopy in any of the P10-SE rats (n=6) or controls (n=6).

Fig. 1.

Rats experiencing SE at P10 do not develop spontaneous seizures. (A) Representative hippocampal (Hp) and cortical (Cx) electroencephalogram tracing from an adult rat that had experienced SE 3 months earlier at P10. Note the absence of inter-ictal epileptiform discharges or electrographic seizures. (B, C) Representative Hp and Cx electroencephalogram tracing from a rat 1 month after experiencing SE in adulthood. Note the presence of inter-ictal epileptiform discharges (B) and an electrographic seizure (C).

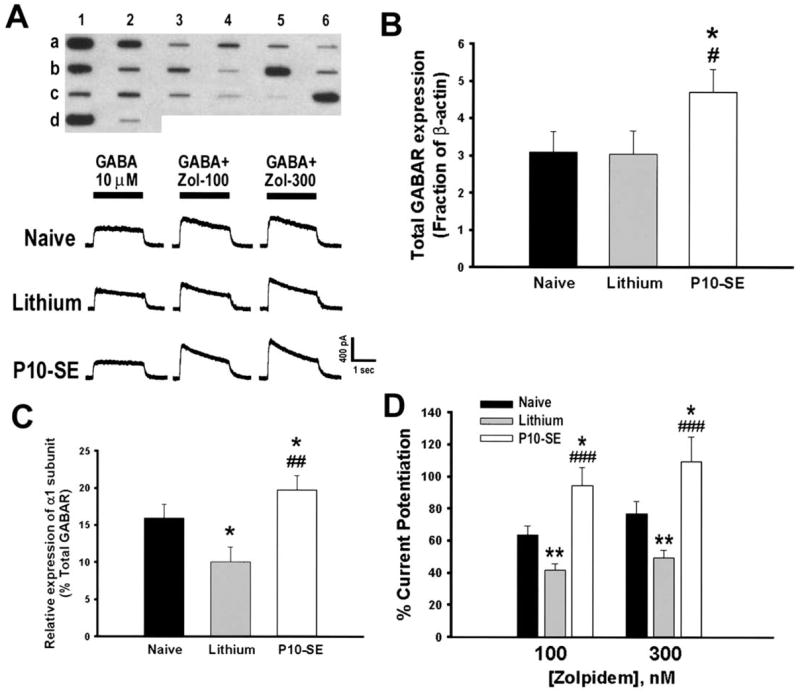

GABAR properties after P10-SE

Expression of 16 GABAR subunits (α1– 6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, π, θ) mRNAs was examined in each DGN isolated from the four groups (Fig. 2A). GABAR expression was similar in the lithium- and saline-control groups, and only the former is presented. Overall GABAR mRNA expression (total GABAR) relative to β-actin expression was increased in DGNs from P10-SE rats compared with DGNs from lithium- or naive-controls (Fig. 2B; P=0.04). Mean relative expression (as a percent of total GABAR) of α1 subunit mRNA in DGNs from P10-SE rats was also significantly increased compared with either control group (Fig. 2C; P=0.001). Of additional note, the levels of α1 subunit mRNA were lower in the lithium-control group compared with naive-controls (Fig. 2C; P=0.05), consistent with an effect of neonatal handling on α1 subunit expression as has been previously reported (Hsu et al., 2003). No other significant change was found in expression of any of the other 15 subunits examined.

Fig. 2.

P10-SE altered GABAR subunit expression and pharmacology. (A) Top panel: Representative reverse northern blot from a single DGN isolated from a P10-SE rat. The slot-blot contains cDNAs encoding GABAR subunit α1–α6 (a1–6), β1–β3 (b1–3), γ1–γ3 (b4 – 6), δ, ε, π and θ (c1–4), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; c5), neurofilament-L (NF-L, c6), β-actin (d1), pBluescript (d2). Bottom panels: Representative responses to 10 μM GABA application alone and co-application with zolpidem (100 and 300 nM) in DGNs isolated from naive control, lithium control and P10-SE rats. (B) Total GABAR mRNA expression was increased in P10-SE rats compared with controls (effect of group: F=3.11; P=0.04; pair-wise comparison to naive * P<0.05, lithium # P<0.05, SAS Proc Mixed models; n=21 cells total from nine rats for P10-SE [1–4 cells/rat]; 24 cells total from eight rats for naive-controls [1–6 cells/rat]; 18 cells total from eight rats for lithium-controls [1–4 cells/rat]). (C) Relative expression of α1 subunit mRNA was increased in DGNs from P10-SE rats compared with controls (effect of group: F=7.28; P=0.001; pair-wise comparison to naive * P<0.05, lithium ## P<0.01, SAS Proc Mixed models). (D) GABA current potentiation by zolpidem, a BDZ1 receptor specific positive modulator, was significantly increased in DGNs from P10-SE rats compared with DGNs from naive or lithium control rats. Each cell was treated with 100 nM and 300 nM zolpidem which was pre-applied alone for 30 s before co-applying drug with 10 μM GABA for 2 s. Cells were washed with drug-free recording solution for 2 min between applications to reduce the effects of current run-down and/or desensitization (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01 compared with naive; ### P<0.001 compared with lithium; one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer test for pair-wise post hoc comparison; n=18 cells from four rats for P10-SE, 31 cells from seven rats for lithium-controls and 15 cells from three rats for naives). Note also handling-induced differences in α1 mRNA expression and zolpidem potentiation between lithium- and naive-control groups as has been previously reported (Hsu et al., 2003).

GABAR pharmacology is largely determined by receptor subunit composition. GABARs containing an α1 subunit are more highly augmented by type I benzodiazepine agonists such as zolpidem than GABARs containing any other α-subtype (Pritchett et al., 1989; Barnard et al., 1998), although GABARs containing other α-subunits can respond to zolpidem at high concentrations (Goldstein et al., 2003). There was significantly more augmentation of GABA-induced currents by 100 nM zolpidem in DGNs from P10-SE rats (94.6±11.4%) compared with DGNs from either lithium-control rats (41.8±4.2%) or naive-control rats (63.9±5.3%; Fig. 2D). As α1 was the only subunit to show a significant increase in relative expression after P10-SE, the greater zolpidem augmentation of GABA currents in DGNs from P10-SE rats most likely reflects an increased number of α1 containing GABARs on the membrane of these cells. The GABA concentration-response curve demonstrated no difference in the GABA EC50 or maximum GABA current density between DGNs isolated from pilocarpine-treated animals (P10-SE; EC50 29.55±4.82 μM), lithium-controls (EC50 33.37±7.17 μM) or naive-controls (27.92±6.68 μM).

DISCUSSION

The current study demonstrates that rats experiencing pilocarpine-induced SE at P10 respond differently than those subjected to SE in adulthood (Table 1). Unlike rats experiencing SE as adults, P10-SE rats do not become epileptic and the alterations in hippocampal GABARs in P10-SE rats are of lesser magnitude and in the opposite direction from those seen in adult SE rats. DGNs from P10-SE rats show increased expression of GABAR α1 subunit mRNA and enhanced zolpidem augmentation of GABA-mediated currents compared with controls. In contrast, GABAR α1 subunit expression in DGNs is decreased after SE in adulthood and zolpidem potentiation of GABA-mediated currents is reduced (Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998). Further, the α4, β3 and δ subunits are all up-regulated and the β1 subunit is down-regulated in adult SE rats, while none of these subunits are changed following P10 SE. Taken together these findings demonstrate that the effects of SE on GABARs are highly age-dependent and suggest that the immature dentate may have a selective resistance to GABAR changes after SE compared with the adult.

Table 1.

Consequences of pilocarpine-induced SE

| P10-SE | Adult-SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior | ||

| Spontaneous seizure | No | Yes2,12 |

| Anatomy | ||

| Hippocampal cell loss | No | CA1, CA3, hilar DG12 |

| Mossy fiber sprouting | No | Yes12 |

| DGN GABAR function | ||

| Current density | No change | Increased2 |

| Zolpidem augmentation | Increased | Decreased2 |

| DGN subunit mRNA expression | ||

| Total GABAR mRNA | Increased | Increased2 |

| GABAR α1-subunit | Increased | Decreased2 |

| GABAR α4-subunit | No change | Increased2 |

| GABAR δ-subunit | No change | Increased2 |

Rats do not develop epilepsy after pilocarpine-induced SE at P10 (Fig. 1) in contrast to the nearly uniform development of spontaneous recurrent seizures in rats experiencing SE as adults (Gibbs et al., 1997; Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998; Shumate et al., 1998). This relative protection from development of epilepsy after P10 SE could be related, in part, to the increased GABAR α1 subunit expression. Dentate gyrus serves as a gate in the hippocampal circuit (Heinemann et al., 1992), and the increased GABAR expression in DGN following P10 SE could augment dentate gyrus inhibition and prevent excessive excitation from propagating into hippocampus. In addition, the up-regulation of α4 and δ subunits and the associated increase in zinc inhibition of GABA-currents that are hypothesized to result in a “failure of inhibition” in dentate after adult SE (Buhl et al., 1996; Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998) did not occur after P10 SE. Thus, it is possible that age-dependent differences in SE-induced GABAR effects could contribute to the selective resistance of the immature brain to epileptogenesis. As both anatomical and molecular consequences of SE vary based on the age at which it occurs (Table 1), however, further studies will be needed to determine whether differential effects on GABAR properties contribute to this difference in the rate of later epilepsy development.

The mechanisms regulating GABAR expression are not well understood. GABAR α1 subunit expression in DGNs increases markedly during the first postnatal month (Laurie et al., 1992; Brooks-Kayal et al., 2001). Several lines of evidence suggest that neuronal activity (Meinecke and Rakic, 1990; Huntsman et al., 1994; Holopainen and Lauren, 2003), specifically synaptic signaling through the NMDA selective glutamate receptor (Memo et al., 1991; Harris et al., 1995; Zhu et al., 1995) may be critical for stimulating GABAR α1 receptor subunit expression. Thus the increased α1 subunit expression after P10 SE could be an “over-maturation” of DGN GABARs due to the excessive neuronal activity associated with SE. On the contrary, the diminished α1 expression after SE in adulthood suggests a regression of mature DGN to a more immature state. Determining whether this difference is due to a derangement of “normal” developmental cues for GABAR expression or due to signaling mechanisms that are unique to SE will require additional investigation. These findings reinforce the need for better understanding of age-related differences in the consequences of SE and the mechanisms underlying these differences in order to develop optimal therapeutic approaches for the treatment of epilepsy throughout the lifespan.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (NS-38595 to A.R.B.-K. and NS-83572 to D.A.C.). Statistical support provided by the CHOP MRD-DRC (P30 HD 26979).

Abbreviations

- DGN

dentate granule neuron

- GABAR

GABAA receptor

- P10

postnatal day 10

- SE

status epilepticus

References

- Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, Braestrup C, Bateson AN, Langer SZ. International Union of Pharmacology: XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA. Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Lin DD, Rikhter TY, Holloway KL, Coulter DA. Human neuronal gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: coordinated subunit mRNA expression and functional correlates in individual dentate granule cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8312–8318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08312.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Kelly ME, Coulter DA. gamma aminobutyric acid (A) receptor subunit expression predicts functional changes in hippocampal dentate granule cells during postnatal development. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1266–1278. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl E, Otis T, Mody I. Zinc-induced collapse of augmented inhibition by GABA in a temporal lobe epilepsy model. Science. 1996;271:369–373. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Paysan J, Enna A, Möhler H. Switch in the expression of rat GABAA-receptor subtypes during postnatal development: an immunohistochemical study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5302–5324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05302.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JW, 3rd, Shumate MD, Coulter DA. Differential epilepsy-associated alterations in postsynaptic GABA(A) receptor function in dentate granule and CA1 neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1924–1938. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PA, Elsen PE, Ying S-W, Ferguson C, Homanics GE, Harrison NL. Prolongation of hippocampal miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in mice lacking the GABA(A) receptor α1 subunit. J Neurophysiol. 2003;88:3208–3217. doi: 10.1152/jn.00885.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris B, Costa E, Grayson D. Exposure of neuronal cultures to K+ depolarization or to N-methyl-D-aspartate increases the transcription of genes encoding the α1 and α5 GABA(A) receptor subunits. Mol Brain Res. 1995;28:338–342. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00240-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Beck H, Dreier JP, Ficker E, Stabel J, Zhang CL. The dentate gyrus as a regulated gate for the propagation of epileptoform activity. In: Ribak CE, Gall CM, Mody I, editors. The dentate gyrus and role in seizures. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. pp. 273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen IE, Lauren HB. Neuronal activity regulates GABAA receptor subunit expression in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. Neuroscience. 2003;118(4):967–974. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu FC, Zhang GJ, Raol Y, Valentino RJ, Coulter DA, Brooks-Kayal AR. Repeated neonatal handling with maternal separation permanently alters hippocampal GABA(A) receptors and behavioral stress responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12213–12218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2131679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntsman M, Isackson P, Jones E. Lamina-specific expression and activity-dependant regulation of seven GABA(A) receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey visual cortex. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2236–2259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02236.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie DJ, Wisden W, Seeburg PH. The distribution of 13 GABA (A) receptor subunits in the rat brain: III. Embryonic and postnatal development. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4151–4172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04151.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinecke D, Rakic P. Developmental expression of GABA and the subunits of the GABA(A) receptor complex in an inhibitory synaptic circuit in the rat cerebellum. Dev Brain Res. 1990;55:73–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90107-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memo M, Bovolin P, Costa E, Grayson D. Regulation of GABA(A) receptor subunit expression by activation of NMDA-selective glutamate receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett DB, Luddens H, Seeburg PH. Type I and type II GABA(A)-benzodiazepine receptors produced in transfected cells. Science. 1989;245:1389–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.2551039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raol Y, Budreck EC, Brooks-Kayal AR. Epilepsy after early life seizures can be independent of structural hippocampal injury. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:503–511. doi: 10.1002/ana.10490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS. A simplified Timm stain procedure compatible with formaldehyde fixation and routine paraffin embedding of rat brain. Brain Res Bull. 1982;8:771–774. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(82)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumate MD, Lin DD, Gibbs JW, 3rd, Holloway KL, Coulter DA. GABA(A) receptor function in epileptic human dentate granule cells: comparison to epileptic and control rat. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:114–128. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. Structure and pharmacology of gamma-aminobutyric acid-A receptor subtypes. Pharmacol Rev. 1995;47:181–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperk G, Schwarzer C, Tsunashima K, Fuchs K, Sieghart W. GABAA receptor subunits in the rat hippocampus: I. Immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits. Neuroscience. 1997;80:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W, Laurie D, Monyer M, Seeburg P. The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1040–1062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-01040.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Raol Y, Hsu F, Brooks-Kayal AR. Selective alterations in glutamate receptors and transporters in hippocampal dentate granule neurons after seizures in the developing brain. J Neurochem. 2004;88:91–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Vicini S, Harris B, Grayson D. NMDA-mediated modulation of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor function in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7692–7701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07692.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]