Summary

Purpose

To define the changes in gene and protein expression of the neuronal glutamate transporter (EAAT3/EAAC1) in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy as well as in human hippocampal and neocortical epilepsy.

Methods

The expression of EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA was measured by reverse Northern blotting in single dissociated hippocampal dentate granule cells from rats with pilocarpine-induced temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and age-matched controls, in dentate granule cells from hippocampal surgical specimens from patients with TLE, and in dysplastic neurons microdissected from human focal cortical dysplasia specimens. Immunolabeling of rat and human hippocampi and cortical dysplasia tissue with EAAT3/EAAC1 antibodies served to corroborate the mRNA expression analysis.

Results

The expression of EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA was increased by nearly threefold in dentate granule cells from rats with spontaneous seizures compared with dentate granule cells from control rats. EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA levels also were high in human dentate granule cells from patients with TLE and were significantly elevated in dysplastic neurons in cortical dysplasia compared with nondysplastic neurons from postmortem control tissue. No difference in expression of another glutamate transporter, EAAT2/GLT-1, was observed. Immunolabeling demonstrated that EAAT3/EAAC1 protein expression was enhanced in dentate granule cells from both rats and humans with TLE as well as in dysplastic neurons from human cortical dysplasia tissue.

Conclusions

Elevations of EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA and protein levels are present in neurons from hippocampus and neocortex in both rats and humans with epilepsy. Upregulation of EAAT3/EAAC1 in hippocampal and neocortical epilepsy may be an important modulator of extracellular glutamate concentrations and may occur as a response to recurrent seizures in these cell types.

Keywords: Glutamate transporter, EAAT3/EAAC1, Epilepsy, Dentate, Dysplasia

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system and has been implicated as a neurotoxic agent in several neurologic disorders including epilepsy, ischemia, and certain neurodegenerative diseases (1,2). Unbound extracellular glutamate is cleared primarily by sodium-dependent transport of glutamate into glia and neurons (for review, see 3,4), and glutamate transport is thought to be crucial for preventing accumulation of neurotoxic levels of extracellular glutamate. Multiple subtypes of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters have been identified pharmacologically, and four rat (GLAST, GLT-1, EAAC1, and EAAT4) and five human (EAAT1-5) transporters have been identified by molecular cloning (5). The excitatory amino acid transporters EAAT1 (GLAST) and EAAT2 (GLT-1) are expressed primarily in astroglial cells, whereas EAAT3 (EAAC1) and EAAT4 are enriched in neurons. EAAT3/EAAC1 is the most abundant neuronal transporter, and is selectively enriched in neurons of the hippocampus, cerebellum, and basal ganglia (6).

A disturbance in glutamate-mediated excitatory neurotransmission has been implicated as a critical factor in the etiology of many pediatric and adult forms of epilepsy. Several studies have demonstrated changes in glutamate levels in both animal seizure models and human epilepsy patients. For example, elevated extracellular glutamate levels have been observed in the kindling (7,8) and E1 genetic (9) models of epilepsy. In studies of human epilepsy, increased levels of glutamate and glycine have been demonstrated in excised epileptic tissue (10,11), and microdialysis studies have shown increases in extracellular glutamate concentrations before and during seizures (12).

Because a major determinant of extracellular glutamate levels is glutamate uptake, altered glutamate concentrations in epilepsy could result from aberrant expression or function of glutamate transporters. For example, a loss of high-affinity glutamate uptake in kindled rats has been reported 1 week after the last seizure (13). Changes in glutamate transporter expression also have been demonstrated in several animal models of epilepsy both immediately after status epilepticus (SE) (14,15) and in the long term (16–19). Furthermore, several studies have shown regional increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 expression in the kindling (16,20), intraamygdalar kainate (19), and Fe3+-induced rat models of epilepsy (17,18). Interestingly, EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA and protein levels have been reported to be both increased (19) and decreased (15) in different kainic acid seizure models. Rothstein et al. (21) demonstrated that reduction of EAAT3/EAAC1 expression in rats with intraventricular antisense oligonucleotides results in seizures. Increased human EAAT3 protein expression (homologous to rat EAAC1) has been detected by immunocytochemistry in hippocampal tissue from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE; 22,23) and increased EAAT3 mRNA has been seen in dysplastic neurons and giant cells from patients with tuberous sclerosis (24). These results, obtained from both animal models and human studies, suggest a potentially important role for changes in glutamate transport (particularly EAAT31/EAAC1) in several forms of epilepsy.

We hypothesized that EAAT3/EAAC1 glutamate transporter mRNA and protein are differentially expressed in distinct neuronal subtypes in experimental and human epilepsy. To test this hypothesis, we first determined EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA expression in single dissociated hippocampal dentate granule cells in the rat pilocarpine model of TLE and in human patients with intractable TLE. EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA expression also was measured in single microdissected dysplastic neurons from patients with epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia (FCD). Poly (A) mRNA amplified from these single cells was amplified (25), radiolabeled, and used to probe arrays containing EAAT3/EAAC1 cDNA so that expression levels could be determined. Rat and human specimens were then probed with EAAC1 antibodies to determine protein expression in these cells types.

METHODS

Patient material and tissue processing

Human FCD and hippocampal sclerosis specimens were obtained from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, and Medical College of Virginia as part of treatment for medically refractory complex partial epilepsy. FCD specimens were resected from four patients (aged 11–28 years; one male, three female patients). One specimen was resected from the dorsolateral prefrontal region, whereas in the remaining three patients, the dysplasia was identified in the temporal neocortex. FCD specimens were characterized histologically by disorganized cortical lamination, large dysplastic neurons scattered throughout the cortical mantle with loss or disruption of radial orientation to the pial surface, and numerous heterotopic neurons in the subcortical white matter. Hippocampal specimens used for immunohistochemistry were from three women (ages, 21–33 years) with complex partial seizures. Hippocampal tissue used for short-term isolation of dentate granule cells was collected from six patients (four men, two women; ages 16–54 years) at the time of temporal lobectomy for the treatment of medically intractable complex partial epilepsy. All hippocampal specimens were characterized histologically by gliosis and cell loss within the CA sectors as well as loss of granule cells in the dentate gyrus, consistent with a histopathologic diagnosis of hippocampal sclerosis.

Two control patient groups were included in the analysis. First, lateral temporal neocortex without histologic evidence of FCD was analyzed from four patients (ages 18–33; two men, two women) undergoing temporal lobectomy for the treatment of medically intractable complex partial epilepsy in the setting of pathologically confirmed hippocampal sclerosis. These patients served as nondysplastic epilepsy controls so that any observed changes in gene or protein expression in cortical dysplasia samples could not be ascribed to the effects of recurrent seizures or antiepileptic drug (AEDs) alone. Second, control hippocampi and lateral temporal neocortex were obtained postmortem from four age-matched patients (two men, two women; ages 31–48 years; mean age, 36) who died of nonneurologic causes (average postmortem interval to autopsy, 12 ± 3 h). These specimens were without histologic evidence of hippocampal sclerosis or FCD. There was no history of seizures or epilepsy. Collection and use of human resected or necropsy material was performed in accordance with the policies of the Institutional Review Boards and Committees on Human Research of University of Pennsylvania, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Medical College of Virginia.

For immunohistochemistry, brain tissue samples obtained intraoperatively or at necropsy were fixed by immersion in 70% ethanol/150 mM NaCl or neutral buffered formalin. Specimens were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 7 μm, and mounted on poly-L-lysine–coated coverslips.

Pilocarpine injections

Pilocarpine injections were performed according to previously published protocols (26,27). Adult rats, ~60–90 days postnatal, were injected first with scopolamine methyl nitrate (1 mg/kg, i.p.) to minimize the peripheral effects of pilocarpine, and subsequently injected 30 min later with pilocarpine (350 mg/kg, i.p.). Pilocarpine injection generally triggered long duration (>30 min) seizures within 10–30 min of injection. Rats that did not exhibit behavioral seizures within 1 h of pilocarpine injection were injected with a second dose of pilocarpine (175 mg/kg, i.p.). Diazepam (DZP, 4 mg/kg, i.p.) in 50% propylene glycol was administered 1 h after the onset of SE to stop seizure activity, and again 3 and 5 h after onset of seizure as needed. Control rats were treated identically to pilocarpine-injected rats, except that a sub-convulsive dose of pilocarpine (35 mg/kg) was administered. Animals were video monitored beginning 2 weeks after pilocarpine injection, and animals documented to have at least two spontaneous seizures (class 3 or higher) were classified as epileptic. To minimize any short-term effects of seizures on transporter expression, epileptic animals were subjected to 24 h of video monitoring to ensure that no seizures occurred in the 24 before use.

Short-term isolation of neurons from the rat and human dentate gyrus

Dentate granule cells were isolated from rat or human hippocampus according to previously published protocols (26,27,39). Immediately after surgical resection, human hippocampal specimens were placed in chilled, oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) solution composed of (in mM): 201 sucrose, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaHPO4, 2 MgCl2, 2 6 CaCl 2, 2 6 NaHCO 3, and 10 dextrose, and rapidly transported to the laboratory (5- to 10-min transit time) from the operating room. Rat brains were rapidly removed immediately after decapitation, and then placed in chilled, oxygenated aCSF. Human and rat hippocampal slices (450 μm) were then cut on a vibratome and incubated for 1 h in an oxygenated medium containing (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 25 glucose, and 20 piperazine-N,N′-bis[2-ethanesulfonic acid] (PIPES), pH adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH at 32°C. Slices were enzymatically digested 20–60 min in 3 mg/ml Sigma protease XXIII in PIPES, thoroughly rinsed, and incubated another 30 min in PIPES medium before dissociation. The dentate gyrus was visualized with dark-field microscopy, 1-mm2 blocks were dissected, and then cells were mechanically dissociated and plated onto 35-mm culture dishes in N-2-hydroxy-ethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethane sulfonic acid (HEPES) medium composed (in mM) of 155 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 3 CaCl2, 0.0005 tetrodotoxin, and 10 HEPES-Na+, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH.

Immunohistochemistry

FCD, hippocampal sclerosis, nondysplastic cortex, and postmortem control tissue sections were probed with a previously characterized, affinity-purified polyclonal antibody raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to the C-terminal region of rabbit EAAC1 (courtesy of J. Rothstein, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Rothstein et al., 1994). Primary antibody labeling was performed overnight at 4°C in 0.1 M TRIS/2% horse serum. Immunolabeling was visualized with the avidin–biotin conjugation method (Vectastain ABC Elite; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.) and 3,3′-diamino-benzidine. Some slides were coverslipped after ethanol/xylene fixation in Permount (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

In situ transcription

Tissue sections were treated with proteinase K (50 μg/ml) at 37°C for 30 min and then washed in DEPC-treated water. Sections were then processed for mRNA amplification beginning with in situ reverse transcription (IST) of cellular poly (A) mRNA into cDNA directly on the tissue section (28). To initiate IST, an oligo-dT (24) primer coupled to a T7 RNA polymerase promoter was annealed to cellular poly (A) mRNA overnight at room temperature. cDNA synthesis was then performed in IST reaction buffer [10 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 120 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 250μM deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP), deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP), deoxyguanosine triphosphate (dGTP), thymidine triphosphate (TTP)] with avian myeloblastosis reverse transcriptase, 0.5 U/μl, (AMVRT, Seikagaku America, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.). Sections were washed in 0.5× SSC buffer.

Microdissection of single neurons

After IST, single neurons from cortical dysplasia, non-dysplastic cortex, and postmortem control sections were microdissected under light microscopy using a glass Femtotip (Eppendorf) and joystick micromanipulator (Fig. 2). Dysplastic neurons in focal cortical dysplasia, were histologically defined as large neurons exhibiting a dysmorphic cell soma and a laterally displaced nucleus that were without clear laminar organization or radial orientation of an apical dendrite toward the pial surface. Heterotopic neurons were identified within the subcortical white matter and were ≥500 μm from the junction of the dysplastic cortex and white matter. Dysplastic (n = 10 cells per case) and heterotopic neurons (n = 10 cells per case) were microdissected from the FCD sections (n = 40 total DN and n = 40 total HN from 4 FCD cases). Pyramidal (control) neurons in layer V were microdissected from the epilepsy specimens without evidence of FCD and from the postmortem cortical specimens (n = 10 cells each per case; n = 40 total nondysplasia neurons and n = 40 total control neurons).

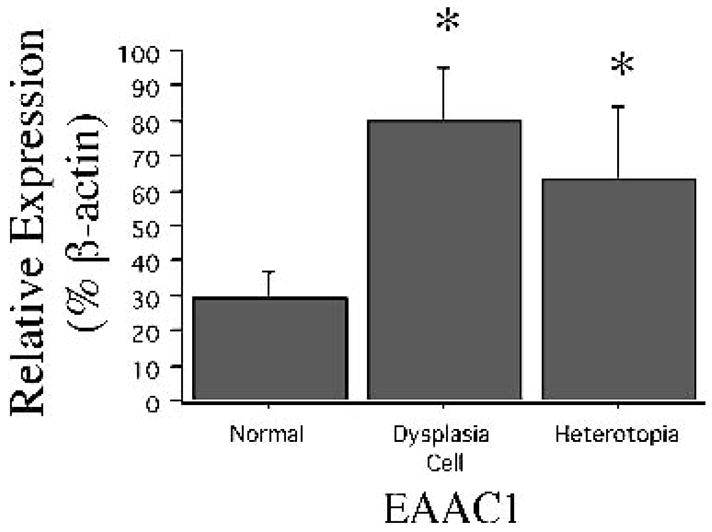

FIG. 2.

Relative EAAT3/EAAC1 abundance is increased in single dysplastic neurons and heterotopic neurons compared with control neurons (n = 30–40 cells in each group). Significant differences (*) between mean percentage hybridization (y-axis, ±SE bar; p < 0.05) are depicted.

mRNA amplification from single neurons

The method for single-cell mRNA amplification from single live cells and fixed brain tissue has been described in detail (24,26,28,39). Dentate granule cells and micro-dissected single neurons were aspirated into a glass microelectrode, transferred to a microcentrifuge tube containing IST buffer and AMVRT, and incubated at 40°C for 90 min to ensure cDNA synthesis in the single dissected cell. Double-stranded template cDNA was generated with T4 DNA polymerase I (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.). mRNA was amplified (aRNA) from the double-stranded cDNA template with T7 RNA polymerase (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI, U.S.A.). aRNA served as a template for a second round of cDNA synthesis with AMVRT, dNTPs, and N(6) random hexamers (Boehringer-Mannheim). cDNA generated from aRNA was made double stranded and served as templates for a second aRNA amplification incorporating [32P]CTP. The size range of radiolabeled aRNA from neurons was assayed on a 1 % agarose denaturing gel. Radiolabeled aRNA was used to probe reverse Northern blot containing candidate cDNAs.

cDNA array analysis

Linearized plasmid EAAC1 (courtesy M. Hediger) and GLT-1 (courtesy B. Kanner) cDNAs were adhered to nylon membranes via UV-crosslinking. Neurofilament, β-actin, and α-internexin (courtesy R. McKay) cDNAs were included as “housekeeping genes” to serve as positive hybridization controls. pBlueScript plasmid cDNA was used to define background levels of hybridization. Blots were hybridized (24 h) in 6× SSPE buffer, 5× Denhardt’s solution, 50% formamide, 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS), and salmon sperm DNA, 200 μg/ml, at 42°C. Slot blots were washed in 2× SSC and were then apposed to a phosphorimaging screen cassette for 24–48 h to generate an autoradiograph.

Statistical analysis

EAAT3/EAAC1 and EAAT2/GLT-1 mRNA expression was determined in single short-term isolated dentate granule cells from pilocarpine treated rats at the latent phase (24 h after SE) and epileptic phase (2 weeks or more after pilocarpine injection) after onset of spontaneous seizures; in dentate granule cells from humans with TLE; in dysplastic and heterotopic neurons from humans with neocortical epilepsy; and in pyramidal (control) neurons in layer V from the epilepsy specimens without evidence of FCD, and the postmortem cortical specimens. The hybridization intensity of each aRNA–cDNA hybrid was determined by densitometry of the slot–blot phosphorimage generated from whole-section or single-cell aRNA probes (ImageQuant 5.0 software). Nonspecific (background) hybridization to pBluescript (PBS) plasmid cDNA was subtracted from that of each aRNA-cDNA hybrid. The relative abundance of EAAT3/EAAC1 and EAAT2/GLT-1 mRNAs was expressed as a percentage of β-actin hybridization intensity within the same cells. Differences in relative abundance of these mRNAs were determined by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni correction and Fischer’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). To control for possible changes in β-actin expression, relative abundances also were calculated relative to a second housekeeping protein (neurofilament L), and statistics results were similar with both methods of calculation.

RESULTS

EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA is increased in rat and human dentate granule cells and human dysplastic neurons

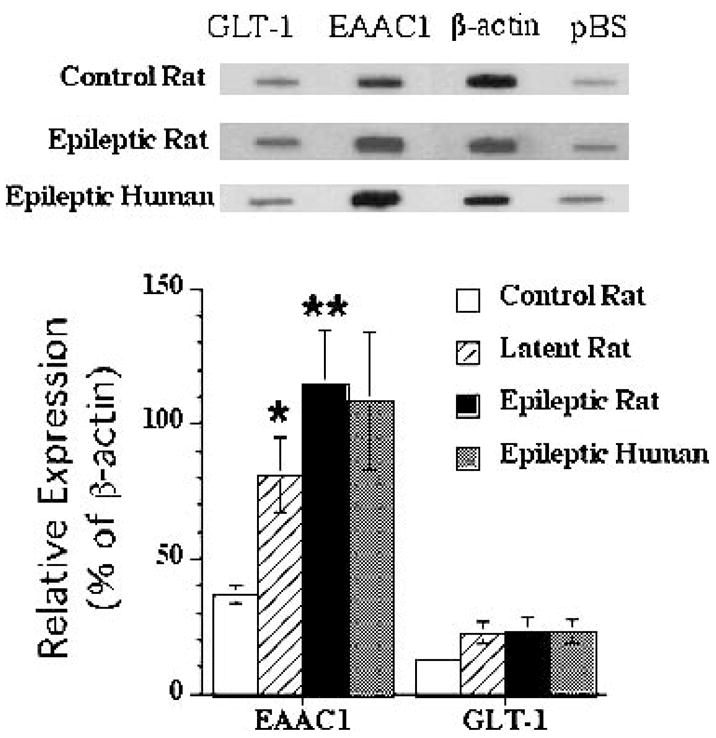

EAAT3/EAAC1 was a medium-abundance mRNA in single control rat dentate granule cells (36.7 ± 3.2% of β-actin; n = 16 cells). During the latent phase after pilocarpine treatment (24 h after SE), there was a twofold increase in EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA in rat dentate granule cells (relative expression, 80.9 ± 13.8% of β-actin; n = 14 cells; p < 0.05; Fig. 1) when compared with control levels. After development of spontaneous seizures (two or more weeks after initial treatment with pilocarpine), EAAC1 mRNA expression was further increased compared with control and latent-phase levels. EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA expression in dentate granule cells from spontaneously epileptic rats (114.7 ± 25.5% of β-actin; n = 23 cells) was nearly 3 times that observed in controls (p < 0.01; Fig. 1). In contrast, although low levels of EAAT2/GLT-1 mRNA were identified in all dentate granule cells, no difference in relative expression was seen between the groups (12.5 ± 1.4%, 22.3 ± 4.1%, and 23.0 ± 5.3% of β-actin expression in control, latent, and chronically epileptic dentate granule cells, respectively). In humans with TLE (n = 37 cells isolated from six different patients), EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA expression in single dentate granule cells was 3 times greater than that observed in control rat (108.5 ± 25.5% of β-actin; Fig. 1), and the relative abundance of EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA was similar in dentate granule cells from rats and humans with epilepsy (no statistical analysis performed between rat and human; short-term isolated control human dentate granule cells were not available for comparison). In contrast, the levels of EAAT2/GLT-1 expression were comparable between dentate granule cells from human epilepsy specimens (23.1 ± 4.5% of β-actin) and both epileptic and control rats. EAAT3/EAAC1 was a medium-abundance mRNA in control human cortical neurons obtained from both postmortem and nondysplastic epilepsy specimens, and its expression did not differ between these two groups (not shown). In contrast, a greater than threefold higher level of EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA expression was detected in dysplastic and heterotopic neurons compared with control neurons (Fig. 2). Low-abundance EAAT2/GLT-1 mRNA was present in the vast majority of cortical neurons, but did not differ between control, dysplastic, and heterotopic neurons (17 ± 3%, 19 ± 4%, and 14 ± 2 % of β-actin expression in control, dysplastic, and heterotopic neurons, respectively).

FIG. 1.

Top, representative cDNA array probed with aRNA from single dentate granule cells from control, latent period, and epileptic rats and from humans with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Note increase in hybridization intensity to EAAC1 cDNA in latent period and epileptic dentate granule cells with no change in β-actin, EAAT2/GLT-1, or pBS hybridization. Bottom, graphic representation of relative EAAT3/EAAC1 expression (percent of β-actin expression) in dentate granule cells from control, latent, and epileptic rats after pilocarpine treatment, as well as in dentate granule cells from six patients with TLE (n = 36 cells). Significant differences (*) between mean percentage hybridization in control and epileptic rat dentate granule cells are noted (y-axis, ±SE bar; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). There is no change in EAAT2/GLT-1 mRNA expression in the latent or epileptic phases. Statistics were not performed comparing rat and human cells.

Immunohistochemical localization of EAAT3/EAAC1 in rat TLE, human TLE, and cortical dysplasia

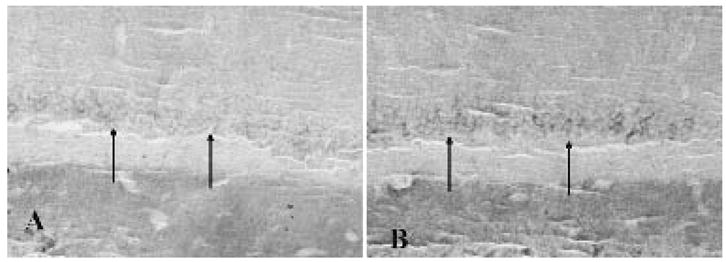

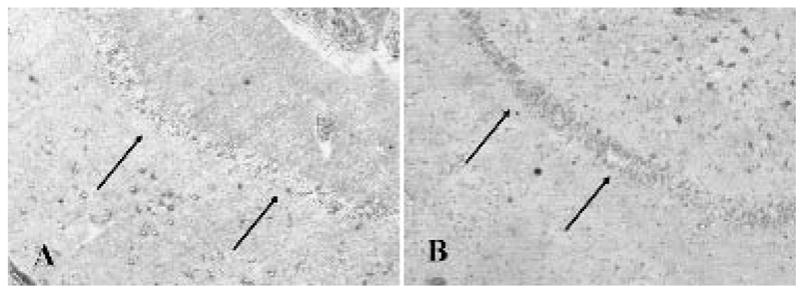

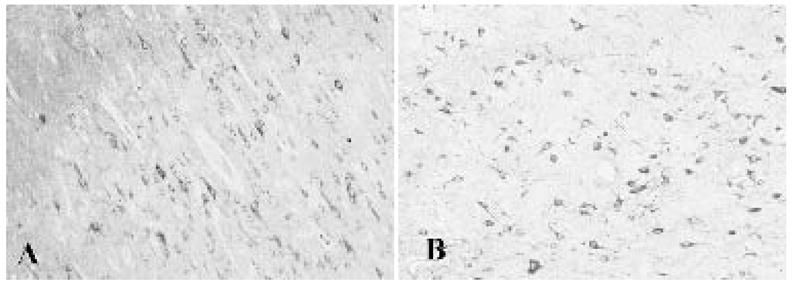

In control rat hippocampus, pyramidal neurons in CA1-3 and a small percentage of dentate granule cells exhibited EAAT3/EAAC1 immunoreactivity (Fig. 3). Although dissociated human control dentate granule cells were not available for mRNA analysis, fixed postmortem control hippocampal specimens were analyzed for EAAT3/EAAC1 protein expression. In human control hippocampi, many CA1-3 pyramidal neurons were EAAT3/EAAC1 immunoreactive, and modest EAAT3/EAAC1 staining was noted in the dentate gyrus (Fig. 4). In contrast, robust EAAT3/EAAC1 immunolabeling was identified in the dentate granule cells of rat (Fig. 3) and human (Fig. 4) epilepsy specimens, with intensely EAAT3/EAAC1 immunoreactive dentate granule cells noted throughout the length and width of the dentate gyrus.

FIG. 3.

A: Modest staining in the dentate gyrus granule cell layer in control rats (arrows). B: Increased immunolabeling of the dentate gyrus granule cell layer in rats receiving pilocarpine after the onset of spontaneous seizures (arrows).

FIG. 4.

A: Modest staining in the dentate gyrus granule cell layer in humans without epilepsy (arrows). B: Increased labeling of the dentate gyrus granule cell layer in patients with medically intractable temporal lobe epilepsy (arrows).

EAAT3/EAAC1 immunoreactivity was identified in pyramidal neurons in layers III, V, and VI of control cerebral cortex (Fig. 5). Most EAAT3/EAAC1-positive neurons exhibited a pyramidal morphology, although a few nonpyramidal or multipolar cells in superficial layers were stained. Many but not all dysplastic and heterotopic neurons in the FCD specimens were robustly EAAT3/EAAC1 immunolabeled. EAAT3/EAAC1 labeling was within the somatodendritic domains of all neurons (Fig. 5). Labeling of astrocytes in was not observed in any specimen.

FIG. 5.

A: EAAT3/EAAC1 staining in control cortex is modest and enriched in pyramidal cells. B: Increased expression of EAAT3/EAAC1 in focal cortical dysplasia. Note selective enrichment in larger dysplastic neurons.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated rapid and long-lasting epilepsy-associated increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 gene and protein expression. These changes appear selective for EAAT3/EAAC1 and occur in different neuronal subtypes and in different forms of epilepsy in both rodent and human. In dentate granule cells in a rat model of TLE, we demonstrated high levels of EAAT3/EAAC1 mRNA and protein expression, comparable to those present in dentate granule cells from hippocampal tissue resected from patients with intractable TLE. Epilepsy-associated increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 expression are not limited to hippocampal neurons and also are present in dysplastic and heterotopic neurons from patients with intractable neocortical epilepsies secondary to cortical dysplasia. These results suggest that altered EAAT3/EAAC1 glutamate transporter expression may occur in a variety of cell types in various forms of epilepsy. Furthermore, our data from animals in the latent period, after pilocarpine-induced SE but before onset of spontaneous seizures, demonstrate that increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 expression occur during the process of epileptogenesis itself. Finally, the upregulation of EAAT3/EAAC1 appears to be selective, as there is no evidence of any epilepsy-associated changes in EAAT2/GLT-1 expression.

EAAT3/EAAC1 is the primary neuronal glutamate transporter in the forebrain. It is selectively enriched in neurons of the hippocampus and is localized in a somatodendritic fashion on postsynaptic spines and somas in a perisynaptic distribution (6). EAAC1/EAAT3 is rarely found presynaptically, except on presynaptic inhibitory terminals, where the may provide a source of glutamate for local synthesis of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (29,30). Under normal conditions, EAAT3/EAAC1 function affects total extracellular glutamate levels to a lesser degree than the primary glial glutamate transporter GLT-1/EAAT2 (31), which is a more active determinant of extracellular glutamate levels in forebrain (21,32).

It is noteworthy that in the current study, levels of expression of EAAT2/GLT-1 mRNA were observed in all dentate granule cells and cortical neurons sampled (Fig. 1). GLT-1 mRNA was originally detected by in situ hybridization in a subset of hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells (33). Other observations suggested that neurons express GLT-1. For example, neurons in culture express GLT-1 protein (26,34) and neuronal expression is observed after a hypoxic–ischemic insult in vivo (35), but there is essentially no evidence that GLT-1 protein is expressed in intact brain tissue (29,36). Thus it seems that neurons express low levels of GLT-1 mRNA that are not efficiently translated into detectable protein, although this could provide a mechanism to translate new glutamate transporters rapidly when needed. Alternatively, we are amplifying a variant of GLT-1, caused by differential RNA splicing, that is not recognized by the antibodies used in earlier studies.

What role might epilepsy-associated increases in EAAC1/EAAT3 expression play in dentate granule cell function? One hypothesis is that enhanced EAAC1/EAAT3 expression might be an important compensatory change designed to enhance clearance of glutamate from the synaptic cleft under conditions of increased and potentially damaging excess extracellular glutamate, which can occur during seizures (12). Indeed, expression of GLT-1/EAAT2, the major determinant of extracellular glutamate in normal brain, does not been appear to be consistently upregulated under these same conditions (14,37). Increased EAAT3/EAAC1 may augment GABA metabolism, particularly if occurring in GABAergic interneurons, although interneurons were not specifically examined in the current study. This hypothesis is supported by studies in the rat in which reduction in EAAC1 mRNA expression by antisense oligonucleotide administration results in seizures, likely as a consequence of diminished presynaptic GABA release, leading to impaired inhibition (6). Increased EAAT3/EAAC1 expression in dentate granule cells, which are excitatory neurons, might also serve to enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission in epilepsy as a compensatory mechanism in response to recurrent synchronous excitation. Increased expression of both GABA and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the synthetic enzyme that converts glutamate to GABA, has been reported in dentate granule cells of animals with TLE (26,38). Further, recent evidence suggests that GABAergic fast synaptic inhibition can occur from dentate gyrus to CA3 (40), and may be enhanced after kindling (41). Taken together, these findings provide a potential mechanism by which the epilepsy-associated increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 in dentate granule cells shown in the current study might facilitate inhibitory synaptic function between dentate gyrus and CA3. Similar hypotheses also can be applied to FCD and neocortical epilepsy. Enhanced excitation has been proposed as a mechanism for seizure initiation in FCD, and a paucity of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons also has been reported in cortical dysplasia specimens (42). Thus increased EAAT3/EAAC1 expression in dysplastic and heterotopic neurons might serve to remove excess extracellular glutamate or augment inhibitory synaptic transmission.

An alternative hypothesis is that epilepsy-associated increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 expression may not be compensatory, and might instead promote epileptogenesis by increasing extracellular glutamate levels by one of several potential mechanisms. For example, if increased EAAT3/EAAC1 results in increased intracellular glutamate, more glutamate might be available for packaging into synaptic vesicles, resulting in enhanced glutamate release. Conversely, increased extracellular glutamate also could occur if there is a reversal of the direction of EAAT3/EAAC1 glutamate transport (from internally to externally rectifying) during epileptogenesis. Reversal of neuronal glutamate transport has been demonstrated in other pathologic conditions such as hypoxia (43), but it remains unclear if a similar phenomenon occurs in the epileptic brain. These hypotheses remain largely speculative, and clearly, more additional studies will be required to define the physiologic role that altered EAAT3/EAAC1 expression plays in hippocampal and cortical neuronal function.

In summary, our data suggest that selective increases in EAAT3/EAAC1 glutamate transport occur in association with epilepsy. These changes occur within individual neurons of a variety of types, both hippocampal and cortical, and are present in both human tissue and animal models of epilepsy. A pivotal question for further study is whether these changes contribute to epileptogenesis or are a compensatory response to neuronal injury.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Kathryn Holloway, Ann-Christine Duhaime, and Gordon Baltuch for their assistance in obtaining the human tissue included in this study, and Dr. Jeffrey Rothstein for providing the EAAC1 antibody. This work was supported by funding from NIMH MH01658, NINDS NS39938, the Esther A. and Joseph Klingenstein Fund, and Parents Against Childhood Epilepsy (PBC); NINDS NS29868 and NS36465 (M.B.R.), NINDS NS32403 and NS38572 (D.A.C.), and NINDS NS38595 (A.B.K.).

References

- 1.Greenamyre JT. The role of glutamate in neurotransmission and in neurologic disease. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:1058–63. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520100062016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi DW. Excitotoxic cell death. J Neurobiol. 1992;23:1261–76. doi: 10.1002/neu.480230915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sims KD, Robinson MB. Expression patterns and regulation of glutamate transporters in the developing and adult nervous system. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1999;13:169–97. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v13.i2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dabolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson MB, Dowd LA. Heterogeneity and functional properties of subtypes of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters in the mammalian central nervous system. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;37:69–115. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60948-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maragakis NJ, Rothstein JD. Glutamate transporters in neurologic disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:365–70. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang WQ, Hudson PM, Sobotka TJ, et al. Extracellular concentrations of amino acid transmitters in ventral hippocampus during and after the development of kindling. Brain Res. 1991;540:315–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minamoto Y, Itano T, Tokuda M, et al. In vivo microdialysis of amino acid neurotransmitters in the hippocampus in amygdaloid kindled rat. Brain Res. 1992;573:345–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janjua NA, Kabuto H, Mori A. Increased plasma glutamic acid in a genetic model of epilepsy. Neurochem Res. 1992;17:293–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00966673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry TI, Hansen S. Amino acid abnormalities in epileptogenic foci. Neurology. 1981;31:872–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.7.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherwin A, Robitaille Y, Quesney F, et al. Excitatory amino acids are elevated in human epileptic cerebral cortex. Neurology. 1988;38:920–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.During MJ, Spencer DD. Extracellular hippocampal glutamate and spontaneous seizure in the conscious human brain. Lancet. 1993;341:1607–10. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leach MJ, O’Donnell RA, Collins KJ, et al. Effect of cortical kindling on [3H]D-aspartate uptake and glutamate metabolism in rats. Epilepsy Res. 1987;1:145–8. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(87)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland ML, Delaney T, Noebels JL. Subtype specific down-regulation of glutamate transporter gene expression in three models of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38(suppl 8):5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simantov R, Crispino M, Hoe W, et al. Changes in expression of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters in rat hippocampus following kainate-induced seizure activity. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;55:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller HP, Levey AI, Rothstein JD, et al. Alterations in glutamate transporter protein levels in kindling-induced epilepsy. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1564–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doi T, Ueda Y, Tokumara J, et al. Sequential changes in glutamate transporter mRNA levels during Fe3+-induced epileptogenesis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;75:105–12. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueda Y, Willmore LJ. Sequential changes in glutamate transporter protein levels during Fe3+-induced epileptogenesis. Epilepsy Res. 2000;39:201–9. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ueda Y, Doi T, Tokumara J, et al. Collapse of extracellular glutamate regulation during epileptogenesis: down-regulation and functional failure of glutamate transporter function in rats with chronic seizures induced by kainic acid. J Neurochem. 2001;76:892–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghijsen WEJM, da Silva Aresta Belo AI, Zuiderwijk M, et al. Compensatory change in EAAC1 glutamate transporter in rat hippocampus CA1 region during kindling epileptogenesis. Neurosci Lett. 1999;276:157–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00824-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, et al. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;20:589–602. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathern GW, Mendoza D, Lozada A, et al. Hippocampal GABA and glutamate transporter immunoreactivity in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1999;52:453–72. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tessler S, Danbolt NC, Faull RLM, et al. Expression of the glutamate transporters in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1999;88:1083–94. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White R, Hua Y, Scheithauer B, et al. Selective alterations in glutamate and GABA receptor subunit mRNA expression in dysplastic neurons and giant cells of cortical tubers. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:67–78. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200101)49:1<67::aid-ana10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crino PB, Dichter MA, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Embryonic neuronal markers in tuberous sclerosis: single cell molecular pathology. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14152–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate M, Jin H, et al. Selective changes in single cell GABAA receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1166–72. doi: 10.1038/2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibbs J, Shumate M, Coulter D. Differential epilepsy-associated alterations in postsynaptic GABAA receptor function in dentate granule and CA1 neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1924–38. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.4.1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kacharmina JE, Crino PB, Eberwine J. Preparation of cDNA from single cells and subcellular regions. Methods Enzymol. 1999;303:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)03003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothstein JD, Martin L, Levey AI, et al. Localization of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters. Neuron. 1994;13:713–25. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furuta A, Martin LJ, Lin CLG, et al. Cellular and synaptic localization of the neuronal glutamate transporters excitatory amino acid transporter 3 and 4. Neuroscience. 1997;81:1031–42. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson MB. The family of sodium-dependent glutamate transporters: a focus on the GLT-1/EAAT2 subtype. Neurochem Int. 1999;33:479–91. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(98)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, et al. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276:1699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torp R, Danbolt NC, Babale E, et al. Differential expression of two glial glutamate transporters in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:936–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mennerick S, Dhond RP, Benz A, et al. Neuronal expression of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 in hippocampal microcultures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4490–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04490.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin LJ, Brambrink AM, Lehmann C, et al. Hypoxia-ischemia causes abnormalities in glutamate transporters and death of astroglia and neurons in newborn striatum. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:335–48. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaudhry FA, Lehre KP, Campagne MVL, et al. Glutamate transporters in glial plasma membranes: highly differentiated localizations revealed by quantitative ultrastructural immunocytochemistry. Neuron. 1995;15:711–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akbar MT, Torp R, Danbolt NC, et al. Expression of glial glutamate transporters GLT-1 and GLAST is unchanged in the hippocampus in fully kindled rats. Neuroscience. 1997;78:351–9. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sloviter R, Dichter M, Rachinsky TL, et al. Basal expression and induction of glutamate decarboxylase and GABA in excitatory granule cells of the rat and monkey hippocampal dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:593–618. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960930)373:4<593::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, et al. Human neuronal γ-aminobutyric acid A receptors: coordinated subunit mRNA expression and functional correlates in individual dentate granule cells. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8312–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08312.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker MC, Ruiz A, Kullmann DM. Monosynaptic GABAergic signaling from dentate to CA3 with a pharmacological and physiological profile typical of mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2001;29:703–15. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gutierrez R, Heinemann U. Kindling induces transient fast inhibition in the dentate gyrus-CA3 projection. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:1371–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spreafico R, Battaglia G, Arcelli P, et al. Cortical dysplasia: an immunocytochemical study of three patients. Neurology. 1998;50:27–36. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rossi DJ, Oshima T, Attwell D. Glutamate release in severe brain ischaemia is mainly by reversed uptake. Nature. 2000;403:316–21. doi: 10.1038/35002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]