Introduction

Schizophrenia is a devastating neuropsychiatric illness. The overall cost of schizophrenia was estimated to be $62. 7 billions in the US in 2002 (Wu et al. 2005). Findings suggest that structural and functional brain abnormalities (Walter et al. 2007;Kuperberg et al. 2007) coexist and are possibly related in the pathological processes underlying the illness.

Structural brain studies employing neuroimaging, particularly Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), have demonstrated that patients with schizophrenia show consistent and reproducible structural brain abnormalities. Cortical loss associated with schizophrenia is progressive (van Haren et al. 2007), more intense in the early course of the disease (Cahn et al. 2002), and related to clinical outcome (Cahn et al. 2002;Cahn et al. 2006).

Even though initial studies reported a general loss of brain volume and subsequent ventricular enlargement (Lawrie and Abukmeil 1998;Shenton et al. 2001), it is now believed that cortical atrophy preferentially affects a subset of brain regions in schizophrenia. Modern automatic segmentation techniques of structural MRI, combined with whole brain rater independent voxel based analyses, demonstrated that regional gray matter atrophy is more intense in regions such the prefrontal cortex, superior temporal gyrus, caudate and the medial temporal lobe (Anderson et al. 2002;Kwon et al. 1999;van Haren et al. 2007;Chua et al. 2007;Hirayasu et al. 2001). Importantly, such regional atrophy has been related to clusters of clinical symptoms. For instance, progressive prefrontal gray matter atrophy is related to more pronounced negative symptoms (Mathalon et al. 2001) or reduced insight (Sapara et al. 2007). The volume of frontal parietal and temporal regions is linked to reality distortion (Whitford et al. 2005) and finally, abnormalities in the superior temporal gyrus are associated with both psychotic and negative symptoms (Crespo-Facorro et al. 2004a;Crespo-Facorro et al. 2004b) and abnormalities in visual and auditory evoked potentials (Egan et al. 1994),.

Of the wide range of clinical symptoms and deficits observed in schizophrenia, higher cognitive deficits are of particular importance since they are strongly associated with poor prognosis (Hofer et al. 2005). Schizophrenic patients show significant deficits in executive function, working memory, and episodic memory (Boeker et al. 2006). These deficits are correlated with well documented patterns of functional neuroimaging (Callicott et al. 2003). It is still unclear if the cognitive profile observed on neuropsychological test performance or the abnormal functional imaging studies implicating in part the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex are a consequence of a specific structural atrophy of the prefrontal cortex, as suspected by some primate (Goldman-Rakic 1999), and post-partum studies (Selemon et al. 2002) or reflect dysfunctional larger neural networks (Zhou et al. 2007;Wolf et al. 2007).

In the current study, we aimed to investigate the relationship between regional prefrontal atrophy and higher cognitive neuropsychological performance of participants with schizophrenia. Specifically, we hypothesized that gray matter atrophy to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, in particular Brodmann area 9 (BA9), will be associated with poor neuropsychological performance on tests that index executive functioning, attention, and word fluency in subjects with schizophrenia compared to matched controls.

Material and methods

Participants

Fourteen participants (11 men, mean age = 40±7 years) and thirteen controls (11 men, mean age = 35±8 years) were enrolled in this study. The majority of participants with schizophrenia came from regional community mental health clinics and a local homeless shelter. Occasionally participants were recruited from the inpatient units operated by the Department of Psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry and Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Charleston, SC. Patients met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID). At the time of the study, patients were free of psychotropic medications (antipsychotics, neuroleptics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, anticholinergics or stimulants) for at least 2 weeks. All patients were judged clinically competent to give informed written consent.

Exclusion criteria for schizophrenia subjects included past history of epilepsy or other neurological disorders, subjects who demonstrated severe exacerbation of their psychosis or the catatonic subtype, subjects currently diagnosed with Substance Dependence (DSM-IV) or Major Depressive Disorder (Calgary depression rating scale > 9) and tobacco smokers with greater than 2 packs per day use.

Control subjects were recruited from the local community through advertisements, and matched with schizophrenia subjects based on gender, race, smoking habits, handedness, and socio-economic status including personal level of education. Many of the patients could not reliably report their parental education level so we could not match based upon it. Control subjects did not meet any active DSM-IV-TR Axis I criteria for psychotic, anxiety, mood, substance abuse or dependence disorder, nor did they have any history of neurological disorder. They did on occasion report a history of substance abuse similar to some individuals of our patient sample.

This study was funded by the NIMH (R21- MH065630-01A1) and approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Clinical and Neuropsychological evaluation

Subjects were rated rated using the Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al. 1989), the Schedule for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Mueser et al 1994)., the Calgary Depression Scale (Addington et al. 1994), the Simpson Angus Scale (Simpson, Angus, 1970). They also underwent 3 separate neuropsychological testings to explore executive functions. The first was the Trail Making Test (TMT) A and B (Reitan and Wolfson 1985), In Part A, participants connect numbers printed on a page sequentially as quickly as possible, providing a measure of attention and psychomotor speed. Part B is similar except that numbers must be alternated with letters, a more complex task that has been considered to require cognitive flexibility and maintenance of a complex response set. The TMT Part A of the test measures psychomotor speed and attention, Part B measures the ability to shift strategy and assess executive function and visuospatial working memory, reflecting the activity of frontal lobes. Subjects also underwent the Controlled Word Association Task (COWAT) (Benton et al. 1994) where they were introduced a letter and are asked to generate words that start with that particular letter. The COWAT tests verbal fluency, aspects of working memory, cognitive speed and effortful self-initiation, (Strauss, Sherman, & Spreen, 2006). Finally, subjects performed the computerized version of Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) (Nelson 1976). In this test, the subject was asked to match test cards to reference cards according to the color, shape, or number of stimuli on the cards. Feedback is provided after each match, enabling the subject to acquire the correct rule of classification. After a fixed number of correct matches, the rule is changed without notice, and the subject must shift to a new mode of classification. The WCST measures cognitive flexibility, that is the ability to alter a behavioral response mode in the face of changing contingencies (set-shifting).

Finally, the subjects also completed the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) (Marin et al. 1991). The AES is a valid tool to discriminate apathy from standard measures of depression and anxiety. Since conceptually, apathy is defined as lack of motivation not attributable to diminished level of consciousness, cognitive impairment, or emotional distress, the addition of this scale was used to further characterize potential frontal lobe impairments.

All participants were instructed to refrain from use of substances such as caffeine that could impact their performance on the day of the assessment. Participants were asked not to smoke in the hour preceding all behavioral and biological study assessments

MRI scanning

All subjects underwent brain imaging using a 3T MRI scanner with a SENSE coil (Intera, Philips Medical Systems; Bothell, WA). T1-weighted structural images encompassing the whole brain were collected from all subjects using the following parameters, TR = 11. 23 ms, TE = 5. 7 ms, slice thickness = 1mm, gap = 0mm, field of view (FOV) = 256mm, number of slices = 160, matrix = 256 × 256.

Voxel based morphometry

T1 images were transformed into Analyze format using the software MRIcro (Rorden and Brett 2000). Optimized VBM analysis was performed using SPM5 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk). Images were spatially normalized and “modulated” in order to preserve the total amount of signal in the images(Good et al. 2001), therefore areas that are expanded during warping are correspondingly reduced in intensity. Spatially normalized images were then re-sliced to an isotropic 1mm and underwent segmentation of gray and white matter using SPM5, estimating the probability of each voxel being gray matter. Images were smoothed with an isotropic gaussian kernel of 10mm to minimize inter-individual gyral variability.

Normalized, segmented and smoothed images were submitted to voxel-wise statistical comparison. We investigated differences in gray and white matter volume between patients with schizophrenia and controls employing a voxel-wise non-parametric Brunner Munzel test, using the software NPM(Rorden et al. 2007) (http://www.sph). Contrasts were defined in order to estimate the probability of each voxel being gray matter. Voxel-wise analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons through false discovery rate threshold of 5%(Genovese et al. 2002).

We also performed a region of interest (ROI) analysis to investigate differences in gray matter volume in the Brodmann areas 9 and 46 (BA9 and BA 46, respectively) between subjects and controls, and their relationship with neuropsychological performance. First, the areas corresponding to BA9 and BA46 were selected and extracted from the Brodmann area map inbuilt in MRIcro (Rorden and Brett 2000). Then, the mean gray matter volume of BA9 and of BA46 weres extracted from each individual using the software Marsbar(Brett et al. 2002).

ROI and neuropsychological data were exported to SPSS v12. We transformed the results of the neuropsychological evaluation and the mean BA9 and BA46 gray matter volumes into Z-Scores, i. e, standardized scores that express the number of standard deviations away from the mean of the control group. Finally, we used a simple regression analysis to examine the relationship between the neuropsychological and MRI data. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0. 05.

Results

There was not a significant difference in gender distribution (Pearson’s Chi square=0. 008, p=0. 927) or age (t(24)=1. 8, p=0. 1) between controls (n=13) and patients (n=14). There were also no differences in the frequency of smokers between groups (Pearson’s Chi square=0. 06, p=0. 9), marital status (Pearson’s Chi square=1. 081, p=0. 792), handedness (Pearson’s Chi square=1. 63, p=0. 65) and race (Pearson’s Chi square=2. 3, p=0. 5). There was no difference in time of education in years between groups ((t(24)=1. 9, p=0. 07). These results reflect successful matching of groups.

As expected, there was a significant difference in the frequency of subjects employed between groups (Pearson’s Chi square=13, p=0. 01). More control subjects were employed than patients. Ten out of 13 controls (77%) were employed full time, and 3 were unemployed (23%) versus 1 out of 14 patients (7%) employed full time, 2 (14%) part time and 11 unemployed (79%). One patient had co-morbid anxiety disorder NOS. Four patients (28%) and 4 controls (30%) had a previous history of polysubstance abuse including alcohol, opiates, cocaine, amphetamine or inhalants.

Neuropsychological evaluation

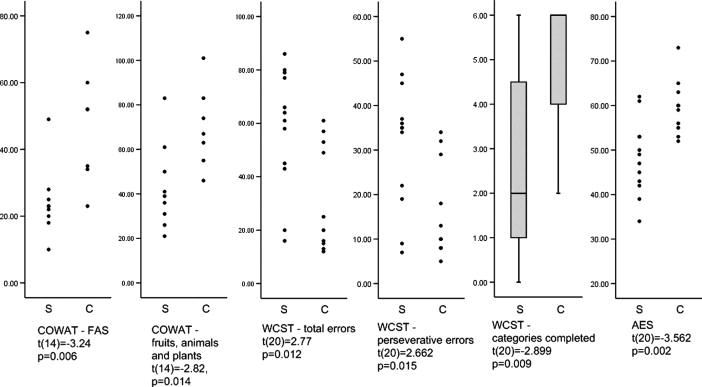

As a group, patients exhibited poorer performance in the COWAT (FAS t(14)=−3. 24, p=0. 006; fruits animal and plants t(14)=−2. 82, p=0. 014). Patients also exhibited a poorer performance on the WCST (total errors t(20)=2. 77, p=0. 012; perseverative errors t(20)=2. 662, p=0. 015; categories completed t(20)=−2. 899, p=0. 009). Patients also presented with a lower score on the AES (t(20)=−3. 562, p=0. 002). These results are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of scores on neuropsychological tests in which patients with schizophrenia exhibited a statistically significant poorer performance.

Voxel based morphometry

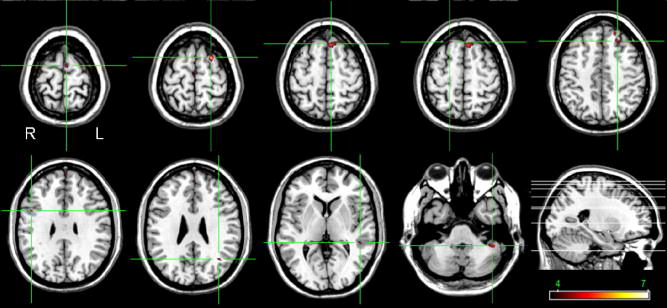

Voxel-wise analysis revealed a significant decrease from controls in gray matter volume in patients with schizophrenia in the left supplementary motor area (x=−5, y=−2, z=71; Z=4. 35; Brodmann area -BA- 6), left superior frontal gyrus (−24, 6, 66; 6. 38; BA6), left superior frontal gyrus (−9, 28, 59; 4. 43; BA8), right superior frontal gyrus (19, 32, 59; 4. 43; BA8), left middle frontal gyrus (−24, 32, 46; 4. 6; BA9), right opercular area (46, 8, 30; 4. 25; BA44), left angular gyrus (−38, −60, 27; 4. 44; BA39), left superior temporal gyrus (−50, −36, 4; 3. 95; BA22), and left cerebellar hemisphere (−45, −43, −41; 4. 21) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Areas of reduced gray matter volume in patients with schizophrenia are shown in ‘hot’, overlaid on a normal brain (highlighted by cross-hairs). The color bar represents the Z-scores.

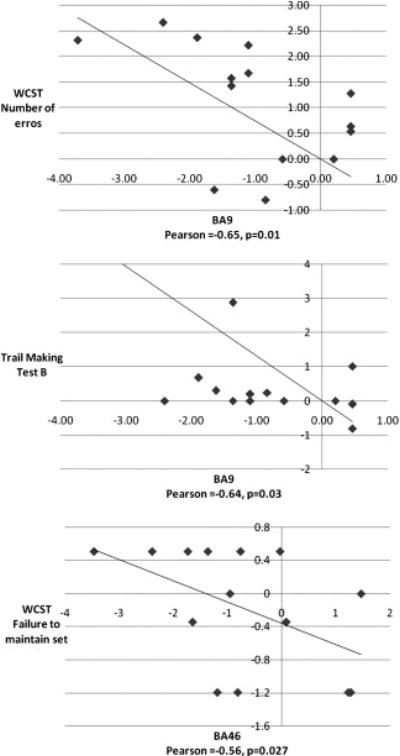

Among subjects with schizophrenia, standardized individual gray matter volume of BA9 was significantly negatively correlated with standardized individual performance on the WCST (number of total errors, Pearson’s correlation coefficient=−0. 65, p=0. 01) and time of completion in the TMT-B (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=−0. 64, p=0. 03) (figure 3). The standardized volume of BA46 was, in turn, correlated with the standardized performance on the WCST (failure to maintain set score, Pearson’s correlation coefficient=−0. 56, p=0. 027). When age was used as a covariate, we observed that the standardized BA9 volume was still significantly correlated with time of completion in the TMT-B (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=−0. 7, p=0. 03) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Standardized gray matter volume reduction of BA9 in patients with schizophrenia (in the form of Z scores, relative to controls) correlates with the standardized impaired performance on the WCST subscale and TMT-B tests.

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia that the relative impairment in mental flexibility usually seen in schizophrenia is directly related to a relative reduction of gray matter volume in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. We also report regional gray matter atrophy in prefrontal cortex, superior temporal gyrus and cerebellum, consistent with proposed neuronal networks implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

It is well recognized that subjects with schizophrenia exhibit a large spectrum of neuropsychological impairments (Elvevag and Goldberg 2000). In particular, subjects with schizophrenia show profound deficits in higher cognitive functions, such as attention, executive function, language and memory (Bilder et al. 1992;Riley et al. 2000). Neurocognitive deficits are related to the natural history of schizophrenia, but are possibly an independent contributor to the morbidity associated with the disease. They can herald the onset of psychotic symptoms, but can also remain relatively stable over the course of the disease (Friedman et al. 2001). Interestingly, impairments in neuropsychological performance persists even after the remission of psychotic or negative symptoms (Heaton et al. 2001;Harvey et al. 1996). These observations suggest that impaired cognitive performance is an inherent feature of schizophrenia, even though it is not yet clear how its underlying mechanisms are related to the pathophysiology of the disease. Most studies investigating regional brain abnormalities related to schizophrenia have observed significant differences in ‘archicortical’ structures, such as the superior and middle frontal gyrus, whilst ‘paleocortical’ structures such as the orbital frontal cortex have been less implicated (Manschreck et al. 2000). There are also indications that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex exerts a hierarchical control of ventral prefrontal cortex (Tan et al. 2006). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may primarily show deficit when faced with conditions of increased task difficulty (Tan et al. 2006) and some of these deficits are tied to specific genetic markers (Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2007). Nevertheless, whilst there seems to be a consistent link between frontal abnormalities and neurocognitive deficits, there is a possibility that these abnormalities are just part of a larger account of symptoms. Indeed, recent evidence suggests that networks of which the frontal lobes are a part are impaired in subjects with schizophrenia (Zhou et al. 2007;Wolf et al. 2007). This indicates that functional abnormalities are possibly more widespread than hypothesized in earlier literature with a cumulative effect on the prefrontal region.

In an attempt to identify key abnormalities that potentially underlie some of the symptoms of schizophrenia, many studies have investigated how the brains of subjects with schizophrenia differ from the brains of healthy individuals. Interestingly, there is an abundance of findings, particularly from structural neuroimaging studies. For instance, in a recent review Antonova et al have highlighted that many different structures have been observed to be abnormal in schizophrenia but most studies lack hypothesis-driven analyses about the relationship between structure and function(Antonova et al. 2004). Moreover, some methodological issues can be raised such as the lack of correction for multiple comparisons or the use of rater dependent manual morphometry. Finally, and of crucial importance, there is inherent variability in test performance, which can yield differences between groups that are not necessarily related to the effects of schizophrenia per se, but rather related to variation in other parameters (e. g., substance use history, physical health, etc. ). Therefore, we suggest that the standardization of the patient results, in comparison to results from controls, is possibly a better approach when evaluating the effects of the disease.

In this manuscript, we have attempted to overcome some of the shortcomings related to studies regarding brain structure and behavioral performance. First, we decided to employ a voxel based morphometry (VBM) technique, to avoid rater dependent bias. VBM depends on correct tissue categorization and is significantly more conservative than manual morphometry given the number of corrections for multiple comparisons that occur in the manual method that result in a higher risk of false negatives. Conversely, positive findings are likely an authentic representation of the effects of the disease. Results can be further trusted when consistent with those found across independent laboratories and reported in existing literature. Indeed, our results are consistent with those of other investigators (e. g., references). Furthermore, ROI analyses can be performed using automated anatomical libraries, such as the AAL (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al. 2002), which are rater independent and are not the result of a priori definition of significant regions.

Second, we have carefully selected a group of subjects to match the demographics of our patient sample. An extremely difficult problem when inferring cognitive function from brain structure is failure to account for alternative explanations for results such as education, cultural exposure, or deprivation related to the disease. Even more complicated are the confounds induced by substance abuse, which plagues people with schizophrenia. Are cognitive deficits related to atrophy that is the result of a mechanism of the disease, or are both structure and behavior a result of life style and personal history and experiences? To control for this problem and limit its effects on our results, we aimed to precisely match our control group, so factors outside of the diagnosis of schizophrenia would be evenly balanced. It also happened that despite having some of our controls meet criteria for a history of substance abuse, the results show significant differences that are likely attributable to the primary psychotic disorder studied. Third, as a result of the matching group of controls, we standardized the results from brain structure and from cognitive performance to the control group. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the relative differences in brain structure and behavior within the patient group while also taking into account sources of error and other variability from both groups. Finally, we focused our analysis on a specific hypothesis and did not revert to an exploratory assessment of the relationships among various cognitive tests and diverse brain regions. The frontal lobe, particularly the prefrontal cortex, has been consistently shown to be abnormal in schizophrenia. Kraepelin suggested that frontal lobe abnormalities underlie emotion, volition and judgment in schizophrenia (Kraepelin 1919). Hence, we hypothesized that dorsolateral frontal lobe atrophy, particularly in BA9, would help explain the relative impairment in mental flexibility and set-shifting in unmedicated subjects with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls with similar ethnic and socio-economic background.

The results presented here are in general accordance with findings from MRI and neuropsychological literature that suggest that cognitive impairments in patients with schizophrenia are related to abnormal structure and function of the prefrontal lobe. Abnormal fMRI activation in the middle frontal gyrus is associated with impaired contextual processing (Holmes et al. 2005; MacDonald, III et al. 2005), whilst reduced anterior cingulate volume is associated with executive dysfunction (Szeszko et al. 2000) and reduced dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex is related to deficits in executive attention and abstraction (Seidman et al. 1994). Interestingly, Zuffante et al (Zuffante et al. 2001) did not observe a significant relationship between working memory and the volume of gray matter in BA 46 in subjects with schizophrenia, but suggested that BA9 could be associated with memory deficits as opposed to BA 46, as now supported by our findings. Similarly, in the largest study to date, albeit in a medicated sample of schizophrenia patients and with a stepwise multiple regression approach, Antonova et al (2005) did not find any relationship between WCST or Trail B and prefrontal cortex volume.

In this manuscript, we aimed to investigate the structural correlates of the neuropsychological profile of patients with unmedicated schizophrenia, many for several weeks to months. Hence, we aimed to investigate the cognitive performance of all patients when they were free of medication for at least two weeks in order to obtain an authentic description of the neuropsychological impairments related to schizophrenia and not to the effects on ongoing medication. However, we did not evaluate the effects of the treatment on the neurocognitive decline related to schizophrenia. Hence, some questions remain open. Does treatment confer a neuroprotective effect with regards to the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Are duration of the disease or duration of treatment independent predictors of neuropsychological performances? Furthermore, is duration of non-treated disease a determining factor for brain atrophy and related cognitive decline? These issues should be evaluated by further studies.

In summary, the results from our study support the general consensus that patients with schizophrenia exhibit significant neurocognitive impairments involving memory, attention and executive functions, including volition and corroborate the initial insight from Kraepelin. Specifically, the abnormalities in the prefrontal cortex may be specifically responsible for some of these symptoms including set-shifting and mental flexibility. Further studies evaluating structural and prefrontal connectivity, in conjunction with performance on neurocognitive tests, will possibly indicate if impaired performance on neuropsychological tests results from abnormalities of the frontal area alone, or are a result of altered networks involving the frontal and extra-frontal areas.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Patient ID | age | gender | race | Handedness | Educastion | Marital Status | Employment | smoking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | M | AA | RH | 7 to 12th | never married | unemployed | smoker |

| 2 | 49 | F | AA | RH | 7 to 12th | never married | unemployed | smoker |

| 3 | 39 | M | C | RH | partial | never married | unemployed | smoker |

| 4 | 45 | M | C | RH | < 6th | divorced or annulled | unemployed | smoker |

| 5 | 23 | M | AA | A | 7 to 12th | never married | unemployed | does not smoke |

| 6 | 49 | M | AA | RH | high school | separated | part time worker | smoker |

| 7 | 39 | M | C | LH | 7 to 12th | divorced or annulled | unemployed | smoker |

| 8 | 39 | F | C | RH | partial | married or cohabitating | part time worker | smoker |

| 9 | 39 | M | AS | RH | 7 to 12th | never married | unemployed | smoker |

| 10 | 32 | M | AA | RH | college | never married | full time worker | smoker |

| 11 | 36 | F | C | Unknown | . | divorced or annulled | . | smoker |

| 12 | 34 | M | AA | RH | 7 to 12th | never married | unemployed | smoker |

| 13 | 45 | M | AA | A | high school | never married | unemployed | smoker |

| 14 | 49 | M | AA | RH | 7 to 12th | never married | unemployed | does not smoke |

| Patient ID | PANSS possxs | PANSS negsxs | PANSS gensxs | PANSS supsxs | PANSS Total | Calgary Depression Total | SANS Total | Apathy Evaluation Scale Total |

| 1 | 21 | 13 | 39 | 9 | 82 | 2 | 33 | 61 |

| 2 | 31 | 18 | 42 | 7 | 98 | 3 | 57 | 45 |

| 3 | 38 | 23 | 56 | 17 | 134 | 4 | 54 | 43 |

| 4 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 42 |

| 5 | 20 | 15 | 38 | 5 | 78 | 2 | 43 | . |

| 6 | 16 | 28 | 37 | 5 | 86 | 5 | 62 | 49 |

| 7 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 23 | 53 |

| 8 | 33 | 13 | 42 | 6 | 94 | 5 | 35 | 50 |

| 9 | 28 | 18 | 37 | 6 | 89 | 1 | 58 | 62 |

| 10 | 22 | 19 | 35 | 3 | 79 | 1 | 22 | 34 |

| 11 | 7 | 18 | 40 | 4 | 69 | . | . | . |

| 12 | 32 | 37 | 70 | 12 | 151 | 4 | 79 | 53 |

| 13 | 21 | 32 | 45 | 5 | 103 | 12 | 68 | 47 |

| 14 | 21 | 21 | 43 | 6 | 91 | 1 | 62 | 39 |

Gender: M = male, F = female

Race: African American = AA, Caucasian = C, Asian = As

Handedness: Right handed = RH, Left handed = LH, Ambidextrous = A

Education: 7 to 12th = 7 to 12 without graduating high school, <6th = 6th grade or less, college = graduated after 4 year of college, high school = high school graduate of GED, partial = partial college or technical school completion.

PANSS possxs = Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale, positive scale

PANSS negsxs = Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale, negative scale

PANSS gensxs = Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale, general psychophathology scale

PANSS supsxs = Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale, supplement

Acknowledgments

Study funded by NIMH MH065630-01A1 (ZN). The authors would like to thank Drs Scott Christie and Patricia Nnadi and their clinical teams; Crisis Ministries Homeless Shelter, Charleston, SC; and the South Carolina Department of Mental Health for their assistance in recruiting participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Anderson JE, Wible CG, McCarley RW, Jakab M, Kasai K, Shenton ME. An MRI study of temporal lobe abnormalities and negative symptoms in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;58:123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00372-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonova E, Sharma T, Morris R, Kumari V. The relationship between brain structure and neurocognition in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:117–145. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual Aphasia Examination. AJA Associates; Iowa City: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bilder RM, Lipschutz-Broch L, Reiter G, Geisler SH, Mayerhoff DI, Lieberman JA. Intellectual deficits in first-episode schizophrenia: evidence for progressive deterioration. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18:437–448. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeker H, Kleiser M, Lehman D, Jaenke L, Bogerts B, Northoff G. Executive dysfunction, self, and ego pathology in schizophrenia: an exploratory study of neuropsychology and personality. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M, Anton JL, Valabregue R, Poline JB. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox [abstract]. Presented at the 8th International Conferance on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain; June 2–6, 2002; Sendai, Japam. Available on CD-ROM in NeuroImage, Vol 16, No 2. 2002. Ref Type: Conference Proceeding. [Google Scholar]

- Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, van Haren NE, Schnack HG, van der Linden JA, Schothorst PF, van Engeland H, Kahn RS. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1002–1010. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn W, van Haren NE, Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Caspers E, Laponder DA, Kahn RS. Brain volume changes in the first year of illness and 5-year outcome of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:381–382. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Mattay VS, Verchinski BA, Marenco S, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Complexity of prefrontal cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia: more than up or down. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:2209–2215. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua SE, Cheung C, Cheung V, Tsang JT, Chen EY, Wong JC, Cheung JP, Yip L, Tai KS, Suckling J, McAlonan GM. Cerebral grey, white matter and csf in never-medicated, first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Kim JJ, Chemerinski E, Magnotta V, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P. Morphometry of the superior temporal plane in schizophrenia: relationship to clinical correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004a;16:284–294. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Nopoulos PC, Chemerinski E, Kim JJ, Andreasen NC, Magnotta V. Temporal pole morphology and psychopathology in males with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2004b;132:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MF, Duncan CC, Suddath RL, Kirch DG, Mirsky AF, Wyatt RJ. Event-related potential abnormalities correlate with structural brain alterations and clinical features in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1994;11:259–271. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvevag B, Goldberg TE. Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is the core of the disorder. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000;14:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JI, Harvey PD, Coleman T, Moriarty PJ, Bowie C, Parrella M, White L, Adler D, Davis KL. Six-year follow-up study of cognitive and functional status across the lifespan in schizophrenia: a comparison with Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1441–1448. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using false discovery rate. GENOVESE2002. Neuroimage. 2002;15(4):870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. Ref Type: Magazine Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. The physiological approach: functional architecture of working memory and disordered cognition in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:650–661. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good CD, Johnsrude IS, Ashburner J, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage. 2001;14:21–36. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Lombardi J, Leibman M, White L, Parrella M, Powchik P, Davidson M. Cognitive impairment and negative symptoms in geriatric chronic schizophrenic patients: a follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Gladsjo JA, Palmer BW, Kuck J, Marcotte TD, Jeste DV. Stability and course of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:24–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayasu Y, Tanaka S, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, DeSantis MA, Levitt JJ, Wible C, Yurgelun-Todd D, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, McCarley RW. Prefrontal gray matter volume reduction in first episode schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:374–381. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer A, Baumgartner S, Bodner T, Edlinger M, Hummer M, Kemmler G, Rettenbacher MA, Fleischhacker WW. Patient outcomes in schizophrenia II: the impact of cognition. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes AJ, MacDonald A, III, Carter CS, Barch DM, Andrew SV, Cohen JD. Prefrontal functioning during context processing in schizophrenia and major depression: an event-related fMRI study. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraepelin E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Livingstone; Edinburgh: 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Deckersbach T, Holt DJ, Goff D, West WC. Increased temporal and prefrontal activity in response to semantic associations in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:138–151. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon JS, McCarley RW, Hirayasu Y, Anderson JE, Fischer IA, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Shenton ME. Left planum temporale volume reduction in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:142–148. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie SM, Abukmeil SS. Brain abnormality in schizophrenia. A systematic and quantitative review of volumetric magnetic resonance imaging studies. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:110–120. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AW, III, Carter CS, Kerns JG, Ursu S, Barch DM, Holmes AJ, Stenger VA, Cohen JD. Specificity of prefrontal dysfunction and context processing deficits to schizophrenia in never-medicated patients with first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:475–484. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manschreck TC, Maher BA, Candela SF, Redmond D, Yurgelun-Todd D, Tsuang M. Impaired verbal memory is associated with impaired motor performance in schizophrenia: relationship to brain structure. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin RS, Biedrzycki RC, Firinciogullari S. Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res. 1991;38:143–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathalon DH, Sullivan EV, Lim KO, Pfefferbaum A. Progressive brain volume changes and the clinical course of schizophrenia in men: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:148–157. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Straub RE, Lipska BK, Verchinski BA, Goldberg T, Callicott JH, Egan MF, Huffaker SS, Mattay VS, Kolachana B, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Genetic evidence implicating DARPP-32 in human frontostriatal structure, function, and cognition. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:672–682. doi: 10.1172/JCI30413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson HE. A modified card sorting test sensitive to frontal lobe defects. Cortex. 1976;12:313–324. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(76)80035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Neuropsychology Press; Tucson: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Riley EM, McGovern D, Mockler D, Doku VCO, Ceallaigh S, Fannon DG, Tennakoon L, Santamaria M, Soni W, Morris RG, Sharma T. Neuropsychological functioning in first-episode psychosis--evidence of specific deficits. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Bonilha L, Nichols T. Rank-order versus mean based statistics for neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorden C, Brett M. Stereotaxic display of brain lesions 29. Behav Neurol. 2000;12:191–200. doi: 10.1155/2000/421719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapara A, Cooke M, Fannon D, Francis A, Buchanan RW, Anilkumar AP, Barkataki I, Aasen I, Kuipers E, Kumari V. Prefrontal cortex and insight in schizophrenia: a volumetric MRI study. Schizophr Res. 2007;89:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman LJ, Yurgelun-Todd D, Kremen WS, Woods BT, Goldstein JM, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Relationship of prefrontal and temporal lobe MRI measures to neuropsychological performance in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;35:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selemon LD, Kleinman JE, Herman MM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Smaller frontal gray matter volume in postmortem schizophrenic brains. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1983–1991. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeszko PR, Bilder RM, Lencz T, Ashtari M, Goldman RS, Reiter G, Wu H, Lieberman JA. Reduced anterior cingulate gyrus volume correlates with executive dysfunction in men with first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2000;43:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan HY, Sust S, Buckholtz JW, Mattay VS, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Egan MF, Weinberger DR, Callicott JH. Dysfunctional prefrontal regional specialization and compensation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1969–1977. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain 19. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haren NE, Hulshoff Pol HE, Schnack HG, Cahn W, Mandl RC, Collins DL, Evans AC, Kahn RS. Focal Gray Matter Changes in Schizophrenia across the Course of the Illness: A 5-Year Follow-Up Study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter H, Vasic N, Hose A, Spitzer M, Wolf RC. Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia compared to healthy controls and patients with depression: Evidence from event-related fMRI. Neuroimage. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitford TJ, Farrow TF, Gomes L, Brennan J, Harris AW, Williams LM. Grey matter deficits and symptom profile in first episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DH, Gur RC, Valdez JN, Loughead J, Elliott MA, Gur RE, Ragland JD. Alterations of fronto-temporal connectivity during word encoding in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;154:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Ball DE, Kessler RC, Moulis M, Aggarwal J. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1122–1129. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Liang M, Jiang T, Tian L, Liu Y, Liu Z, Liu H, Kuang F. Functional dysconnectivity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in first-episode schizophrenia using resting-state fMRI. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuffante P, Leonard CM, Kuldau JM, Bauer RM, Doty EG, Bilder RM. Working memory deficits in schizophrenia are not necessarily specific or associated with MRI-based estimates of area 46 volumes. Psychiatry Res. 2001;108:187–209. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]