Abstract

This study investigated agency and communion attributes in adults’ spontaneous self-representations. The study sample consisted of 158 adults (80 men, 78 women) ranging in age from 20 to 88 years. Consistent with theorising, significant age and sex differences were found in terms of the number of agency and communion attributes. Young and middle-aged adults included significantly more agency attributes in their self-representations than older adults; men listed significantly more agency attributes than women. In contrast, older adults included significantly more communion attributes in their self-representations than young adults, and women listed significantly more communion attributes than men. Significant Age Group × Self-Portrait Display and Sex × Self-Portrait Display interactions were found for communion attributes, indicating that the importance of communion attributes differed across age groups and by sex. Correlational analyses showed significant associations of agency and communion attributes with personality traits and defence mechanisms. Communion attributes also showed significant correlations with four dimensions of psychological well-being.

The concepts of agency and communion are frequently used to describe two basic styles of how individuals relate to their social world (Bakan, 1966; Guisinger & Blatt, 1994; McAdams, 1993). This study examined the implicit expression of agency and communion orientations in adults’ spontaneous self-representations. Specifically, this study had four objectives. First, we examined to what extent adults’ spontaneous self-representations could be categorised in terms of agency- and communion-related attributes. The second objective focused on the examination of age and sex differences in adults’ agency and communion orientations. Third, we examined the associations between adults’ agency- and communion-related attributes and other measures of personality and several dimensions of psychological well-being. Finally, the fourth objective examined the hypothesis that the expression of agency and communion attributes differs across age groups and by sex. Specifically, we examined whether age differences in the ratio between agency and communion attributes are different for women than for men.

Agency and communion as basic behavioural orientations

Bakan (1966) proposed agency and communion as two fundamental modalities of human existence. Agency refers to an individual’s striving to master the environment, to assert the self, to experience competence, achievement, and power. In contrast, communion refers to a person’s desire to closely relate to and cooperate and merge with others (Bakan, 1966). Agency-oriented individuals experience fulfilment through their individual accomplishments and their sense of independence and separateness, whereas communion-oriented individuals experience fulfilment through their relationships with others and their sense of belonging (Guisinger & Blatt, 1994; McAdams, 1993).

Individuals’ agency and communion orientations have been related to a number of different psychological processes, including styles of reasoning, social status evaluations, personality traits, sex-role socialisation, and self-concept. For example, Woike (1994) showed in two studies that agency was associated with a differentiating style of thinking, whereas communion was associated with an integrating style of thinking. Subsequently, Woike, Gershkovich, Piorkowski, and Polo (1999) showed that agentic individuals structured their autobiographical memories using differentiation, whereas communal individuals structured their autobiographical memories in an integrating way.

Other researchers have pointed out that agentic and communal orientations are also expressed in individuals’ cognitive and moral reasoning (e.g., Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, & Tarule, 1986; Gilligan, 1982) and in social perception and group behaviour (e.g., Conway, Pizzamiglio, & Mount, 1996). Belenky et al., for example, described two distinct forms of knowing that depend on the person’s relationship to social objects. Specifically, separate knowing is a form of knowing in which the person distances him or herself from the social object through critical thinking and application of the rules of logic. In contrast, connected knowing refers to a style of understanding and knowing in which the person creates a connection to the social object by acknowledging perceiver-object similarities and taking into account the perspectives of the social object (see also Labouvie-Vief, 1994). Finally, Conway et al. showed in a series of experiments that agency and communion orientations are pervasive in persons’ social perceptions (e.g., perceptions of social status) and in the attribution of personality characteristics to high- and low-status individuals.

Agency and communion are also viewed as basic dimensions of personality (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Wiggins, 1991). Specifically, the development of a strong and independent self and the ability to relate in meaningful ways to others are central concerns of all major personality theories (Guisinger & Blatt, 1994; McAdams, 2000). For example, Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) proposed a model of self and a model of others as the two basic dimensions of Bowlby’s (1988) internal working model of attachment relations. Several studies have shown that these two dimensions parsimoniously describe adults’ attachment styles (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Diehl, Elnick, Bourbeau, & Labouvie-Vief, 1998) and that they relate in meaningful ways to personality traits (Diehl et al., 1998; Shaver & Brennan, 1992). Moreover, trait theorists have acknowledged agency and communion as fundamental coordinates of personality (Wiggins, 1991), and most trait theories incorporate personality factors that are indicative of agency (e.g., dominance, independence, masculinity) or communion (e.g., extraversion, sociability, femininity; see Wiggins & Trapnell, 1996).

Agency and communion have also been strongly associated with sex-role socialisation (Bakan, 1966; Cross & Madson, 1997; Helgeson, 1994) and with self-concept formation (Cross & Madson, 1997; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Helgeson (1994) reviewed the literature on sex-role socialisation and found consistent evidence that men are primarily socialised to be independent, self-sufficient, achievement oriented, adventurous, and risk taking, whereas women are primarily socialised to be nurturing, sensitive, relationship oriented, and help-seeking (see also Cross & Madson, 1997). These characteristics and associated behaviours define the masculine and feminine sex role in many cultures and are traditionally assessed with measures of masculinity and femininity, such as the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI; Bem, 1981) or the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ; Spence, Helmreich, & Stapp, 1974).

Helgeson (1994) also reviewed a large body of research showing that agency/masculinity and communion/femininity tend to be associated with different physical and mental health problems. For example, men show higher rates of externalising disorders (e.g., antisocial behaviour, substance abuse problems) and higher rates of mortality, whereas women show higher rates of internalising disorders (e.g., depression, neuroses) and higher rates of morbidity (see also Feingold, 1994; Gjerde, 1995; Helgeson, 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999; Verbrugge, 1985). This evidence is consistent with findings showing significant sex differences in adults’ coping strategies and defence mechanisms (Diehl, Coyle, & Labouvie-Vief, 1996). Moreover, research has shown that men and women react differently to agency and communion stressors (Smith, Gallo, Goble, Ngu, & Stark, 1998) and that extreme forms of agency and communion, defined as unmitigated agency and unmitigated communion, are related to different physical and mental health problems in men and women (Helgeson & Fritz, 1999, 2000).

In summary, agency and communion are fundamental modalities of human behaviour that influence individuals’ styles of reasoning, their social relationships, personality, and self-concept. Thus, the first objective of the study examined whether adults’ spontaneous self-representations could be categorised in terms of agency and communion. Furthermore, because agency and communion are closely associated with sex-role socialisation, we examined whether agency and communion attributes were differently represented in men’s and women’s self-representations.

Agency and communion across the life span

Traditional views of personality development have put a primary emphasis on agency, individuation, and independence as the hallmark of healthy personality development (Franz & White, 1985). For example, Freud’s (1905/1953) and Erikson’s (1950) stage theories include separation and autonomy as an important step in personality development (Guisinger & Blatt, 1994; Labouvie-Vief, 1994). Moreover, being independent-minded and autonomous in one’s social-emotional reasoning has been defined as a high level of ego development (Loevinger, 1976).

Although agency and independence are valuable goals of individual development, some theorists have argued that being both independent and able to relate in fulfilling ways to others constitutes a more advanced level of development (Blatt & Blass, 1996; Gilligan, 1982; Guisinger & Blatt, 1994). Blatt and Blass, for example, advocate that healthy and mature personality development includes both the development of stable, enduring, and mutually satisfying relationships with others and the development of a differentiated, stable, realistic, and integrated self-concept. Indeed, recent theories of human motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000), personality development (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Blatt & Blass, 1996), and psychological well-being suggest that autonomy and self-acceptance as well as positive relations with others are essential components of a comprehensive conceptualisation of positive psychological health (Ryff & Singer, 1998).

Some theorists (e.g., Gutmann, 1994; Jung, 1933/1962; Labouvie-Vief, 1994) have also suggested that with increasing age and maturation the dialectic tension between agency/individuation and communion/relatedness may change, resulting in a more balanced relationship between the two orientations and perhaps a more androgynous and overall more communal orientation. In particular, Gutmann (1994) suggested that with increasing age men incorporate more feminine characteristics into their behaviour, whereas women show an increasing shift toward masculine behaviours. Although empirical evidence for this suggestion is limited, several studies have reported findings that are consistent with this proposition. Helson and Moane (1987) and Haan (1977), for example, reported longitudinal findings showing that women who changed in a positive way during early and middle adulthood showed increases in agency-related behaviours (e.g., independence, social assertiveness) and simultaneous decreases in communion-related behaviours (e.g., femininity). In a complementary fashion, Haan (1977), Levinson, Darrow, Klein, Levinson, and McKee (1978), and Livson (1981) reported findings for male samples showing that positive changes during the middle years often involved the re-evaluation of agentic/masculine behaviours and goals and the adoption of more communal/feminine behaviours such as nurturance and self-exploration. Other studies, however, have failed to provide similar support and suggest that overall adults may become more communal as they age (Diehl et al., 1996). Although the exact reasons are mostly unexplored, theorists like Labouvie-Vief (1994) seem to suggest that an age-related decline in agentic cognitive abilities may be responsible for the increased communal orientation in older men and women.

Agency and communion and the balance between the two orientations have also been studied in the context of generativity (Ackerman, Zuroff, & Moskowitz, 2000; MacDermid, Franz, & DeReus, 1998), because theories of generativity (Erikson, 1950, 1982; McAdams & de St. Aubin, 1992) suggest that agentic and communal motives are essential for generative behaviour. Thus, from a life-span developmental perspective it is of interest to examine whether older adults show a greater balance between agency and communion than young adults. The present study investigated this question and tested whether there were sex-specific age differences in the ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes. In a cross-sectional study such as the present one, sex-specific age differences in the ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes should result in a significant Age Group × Sex interaction.

Agency and communion and self-representations

Agency and communion also have been linked to theories of self-concept formation. Indeed, theorising about the cultural embeddedness of individuals’ self-concept suggests that Western cultures promote the development of an independent or agentic view of self, whereas Asian and African cultures foster the development of an interdependent or communal view of self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Although there are many reasons for this distinction (see Baumeister, 1987; Gergen, 1991; Markus & Kitayama, 1991), these different conceptualisations have profound consequences for the cognitive, emotional, and motivational functioning of the individual (Cross & Madson, 1997). For example, according to the independent view of self, a person is socialised to express his or her unique needs, desires, and abilities and is encouraged to develop his or her distinct potential. In contrast, the interdependent view of self emphasises the fundamental connectedness of the individual with and responsibility for the physical and social environment and promotes the self in relations with others (Cross & Madson, 1997; Markus & Kitayama, 1991).

Thus, individuals’ understanding of their own person is influenced from early on by the surrounding culture, and these influences manifest themselves in a person’s self-construal and self-representation. However, studies that examine the content of adults’ self-representations with regard to agency and communion orientations have been relatively recent (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Because this study assessed participants’ self-representations in five social roles, the obtained data was particularly suitable for examining agency and communion orientations in adults’ spontaneous self-representations.

Study objectives

The basic assumption of this study was that agency and communion are basic organising dimensions of adults’ self-concept and can therefore be assessed using adults’ spontaneous self-representations. Specifically, agency-oriented individuals were expected to describe themselves primarily in terms of their achievements, sense of autonomy, and desire for power and independence, whereas communion-oriented persons were expected to describe themselves primarily in terms of their relations with and concerns for others. Using a sample of young, middle-aged, and older adults, the first objective examined the distribution of agency- and communion-related attributes in study participants’ spontaneous self-representations.

The second objective focused on the examination of age and sex differences in adults’ agency and communion orientations. In accordance with several theories of adult development (Erikson, 1982; Gutmann, 1994; Labouvie-Vief, 1994), we hypothesised that young and middle-aged adults would report more agency-related attributes as part of their spontaneous self-representations compared to older adults. In contrast, older adults were expected to include more communion-related attributes in their self-descriptions compared to young and middle-aged adults. Consistent with the literature on sex-role socialisation (Cross & Madson, 1997; Eagly, 1987; Maccoby, 1990; Ruble & Martin, 1998), we also hypothesised that women would include more communion-related attributes in their self-representations than men, whereas men were expected to include more agency-related self-descriptors in their self-representations than women. Because our measurement approach permitted the distinction between central and peripheral self-attributes, we also hypothesised that women would have more communion-related representations in the centre of their self-portrait display, whereas men would have more agency-related representations.

The third objective examined the relations of adults’ agency and communion orientations with measures of personality and dimensions of psychological well-being. Although there has been a good deal of research on the role of agency and communion, information on the associations of these constructs with personality and psychological well-being have been ambiguous (Helgeson, 1994; Helgeson & Fritz, 1999). The most systematic information comes from the work of Helgeson and Fritz (1999), who have shown that agency tends to be positively associated with self-esteem and well-being, whereas communion tends to be positively associated with perceived support and support provision. Given these previous findings, we expected that agency would show significant positive correlations with extraversion, openness to experience, and two dimensions of psychological well-being (i.e., environmental mastery, autonomy). Communion attributes were expected to show positive associations with agreeableness and conscientiousness and with several dimensions of psychological well-being (i.e., positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life).

The fourth objective investigated the question whether the relative importance of agency attributes compared to communion attributes increases across age groups in women, and whether the opposite pattern holds for men. Based on previous empirical findings, two scenarios seemed to be plausible. First, an Age Group × Sex interaction seemed to be reasonable, suggesting that across age groups the ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes differed in different directions for men and women. Alternatively, a main effect of age group also seemed to be plausible, suggesting that the relative importance of agency attributes compared to communion attributes would decrease for both sexes in similar ways.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of 158 adults (80 men, 78 women) ranging in age from 20–88 years. Participants were recruited in a mid-sized urban area in southern Colorado through newspaper announcements and announcements at local civic organisations. The majority of the young adults (61.5%) were recruited through announcements at the University of Colorado.

The study sample was divided into three age groups: young adults (n = 52; age range = 20–39 years), middle-aged adults (n = 51, age range = 40–59 years), and older adults (n = 55, age range = 60–88 years). In each age group, men and women were represented in about equal numbers. Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations for key demographic and health variables separate by age group.

Table 1.

Sample description: Means and standard deviations of sociodemographic and health variables

| Age group

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adults (n = 52)

|

Middle-aged adults (n = 51)

|

Older adults (n = 55)

|

||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Age (in years) | 28.68 | 6.19 | 48.06 | 5.10 | 74.43 | 7.61 |

| Education (in years) | 15.08 | 1.87 | 16.26 | 2.36 | 16.02 | 3.48 |

| Annual income (in $1000) | 42.50 | 30.00 | 65.00 | 30.00 | 42.50 | 5.00 |

| Physical health rating | 4.90 | 0.93 | 5.18 | 0.89 | 5.46 | 0.77 |

| Vision rating | 4.64 | 1.27 | 4.45 | 1.14 | 4.95 | 0.78 |

| Hearing rating | 4.98 | 0.87 | 4.94 | 1.10 | 4.47 | 1.23 |

| Life satisfaction rating | 4.42 | 0.72 | 4.69 | 0.76 | 5.07 | 0.66 |

The majority of the participants (89.2%) were Caucasian, reported to be in good health (M = 5.18, SD = 0.89; 1 = very poor, 6 = very good), and to be satisfied with their lives (M = 4.73, SD = 0.76; 1 = extremely unhappy, 6 = extremely happy). Sixty-seven percent of the young adults were full-time or part-time employed, and 27% were full-time students. Of the middle-aged adults, 92% were either full- or part-time employed; the majority of older adults (87%) were retired, yet all of them reported that they were actively involved in volunteer activities. Of the young adults, 58% were single and 35% were married. Of the middle-aged adults, 77% were married, 21% were separated or divorced, and the remainder were single. Of the older adults, 56% were married and 31% were widowed.

Significant differences between age groups were found for the following demographic and health variables: annual family income, F(2, 157) = 4.33, p < .05, life satisfaction, F(2, 157) = 11.18, p < .001, physical health, F(2, 157) = 5.44, p < .01, and self-reported hearing, F(2, 157) = 3.67, p < .05. Middle-aged adults’ annual income was significantly higher than young and older adults’ income. Older adults were, on average, more satisfied with their lives than young and middle-aged adults. On average, older adults rated their overall physical health better than young adults; however, older adults reported having poorer hearing than young adults.

Procedure

Participants attended two 2-hour testing sessions that were scheduled 1 week apart. In compliance with university policy, young and middle-aged adults who were recruited through the university participant pool received course credit for their participation.1 Middle-aged and older adults who were recruited from the community volunteered their time and did not receive any monetary compensation.

The first session was conducted individually, whereas the second session was held in small groups with an average of four participants per session. Group sessions were conducted with members of the same age group only. Between testing sessions, participants filled out two self-report questionnaires, which they returned to the tester in Session 2. Testing was conducted by specially trained graduate research assistants either at the research laboratory or at a location in the community (e.g., the senior citizen centre or participants’ homes).

Measures

The study protocol included a personal data form, a self-representation task, two measures of personality, and a measure of psychological well-being. To control for order of administration effects, the self-concept representation task was administered in a counterbalanced fashion.2 The remaining measures were administered in the same order.

Assessment of Agency and Communion Orientations

Using the procedure developed by Harter and Monsour (1992), indices of agency and communion were derived from adults’ spontaneous self-representations. Participants were asked to provide, separately for each of five role-specific self-representations (e.g., self with family, self with close friend, self with colleagues, self with significant other, self with a disliked person), up to six attributes that described their own person in the respective role. Participants were instructed to describe themselves as honestly and accurately as possible and were encouraged to include negative and positive attributes. Participants were also told that the words they chose to describe themselves could be different or the same across roles. Participants also rated each attribute as positive or negative.

After self-attributes for each role were completed, the examiner transferred the attributes onto a summary sheet. Participants were then asked to indicate for each self-descriptor how important it was in terms of their self-definition for the given role. To facilitate participants’ ratings, they were shown a self-portrait display consisting of three concentric circles. The centre circle was labelled “most important”, the middle circle less “important”, and the outer circle “least important”. After participants rated each attribute in terms of its importance, they transcribed each descriptor into the corresponding circle of the self-portrait display.

Trained coders rated the attributes in participants’ self-portrait display in terms of agency and communion using the definitions in Appendix A. To rate the self-attributes as either agentic or communal, coders were given a list of agency and communion words (see Appendices B and C) that were derived from the Bem Sex Role Inventory (Bem, 1981), the Masculinity and Femininity Scale of the Adjective Checklist (Gough & Heilbrun, 1965), and the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (Spence et al., 1974). If a particular self-attribute was not on the list of agency and communion words, coders were instructed to read the definitions for agency and communion and to rate the word like a word on the list with a similar meaning. Self-descriptors that were not codable as agency or communion attributes were rated as neutral.

Using this coding procedure, the following variables were derived from participants’ self-portrait display: total number of agency and communion words; number of agency and communion words in each circle of the self-portrait display; and number of positive and negative agency and communion words in each circle of the self-portrait display. Coders were trained to a criterion agreement of .80 (i.e., Pearson Product–Moment correlation) or higher. Agreement for the three pairs of coders was .96, .96, and .97, resulting in an average agreement of .96. Disagreements between raters were resolved by consensus ratings. Rater drift was examined after 50% of the self-portrait displays had been coded. All inter-rater correlations were greater than .80; therefore, raters did not receive any additional training.

Measures of Personality

Two measures of personality were included in this study. The first one, the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992), assessed five broad personality dimensions, whereas the second, the Defense Mechanisms Inventory (DMI; Ihilevich & Gleser, 1993), assessed five defence mechanisms as expressed in participants’ reactions to situation-specific vignettes.

NEO Five-Factor Inventory

The short version of the NEO-Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), the NEO-FFI, was used to assess five broad dimensions of personality (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The five factor scales are neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. Each factor is assessed with 12 items to which participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). The coefficients of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) in this study were .87, .76, .70, .84, and .75 for neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, respectively.

Defense Mechanisms Inventory

The DMI (Ihilevich & Gleser, 1993) was used to assess participants’ defence mechanisms. The inventory produces scores for five types of defence, which are determined from participants’ responses to 10 age- and sex-appropriate vignettes. For each vignette, there are four clusters of responses referring to a person’s actual reaction, impulsive reaction, thoughts, and feelings. Within each cluster, participants select their most and least favoured response from five choices, each representing a different defence mechanism: turning against object, projection, principalisation, reversal, and turning against self.

Turning against object represents a defence in which a person uses aggression to achieve mastery over a psychologically demanding situation. In contrast, projection involves the attribution of undesired qualities of the self to others in the absence of validating evidence. Principalisation assesses a person’s tendency to transform conflict into a truism or lesson that may be learned from an otherwise frustrating experience. Reversal measures an individual’s inclination to downplay the negative aspects of a situation and to give it a neutral or positive meaning. Finally, turning against self describes a person’s tendency to resolve psychological conflict by directing aggressive behaviours, feelings, or fantasies toward the self. This defence mechanism also includes the attribution of fault and responsibility to oneself without sufficient reason.

The DMI has good psychometric properties (Ihilevich & Gleser, 1993), including internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent and divergent validity. Estimates of internal consistency in this study were .82, .65, .73, .85, and .78 for turning against object, projection, principalisation, turning against self, and reversal, respectively.

Psychological Well-Being

Participants’ psychological well-being was assessed using the Short Psychological Weil-Being Scales by Ryff (1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). This self-report inventory measures six dimensions of psychological well-being derived from the literature on life-span development, mental health, and personal growth (Ryff, 1989, 1995). The six dimensions are self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relations with others, personal growth, purpose in life, and autonomy. Estimates of internal consistency for these scales were .91, .89, .88, .84, .87, and .87, respectively.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Adults’ spontaneously generated self-representations could be categorised in terms of agency and communion. Participants’ self-portrait displays contained a total of 4553 self-attributes; 39.16% (1783 words) were agency-related attributes, 59.67% (2717 words) were communion-related attributes, and 1.16% (53 words) were coded as neutral. Participants rated 53.11 % of the agency-related attributes as positive and 46.89% as negative. The overwhelming majority (92.49%) of the communion-related attributes were rated as positive.

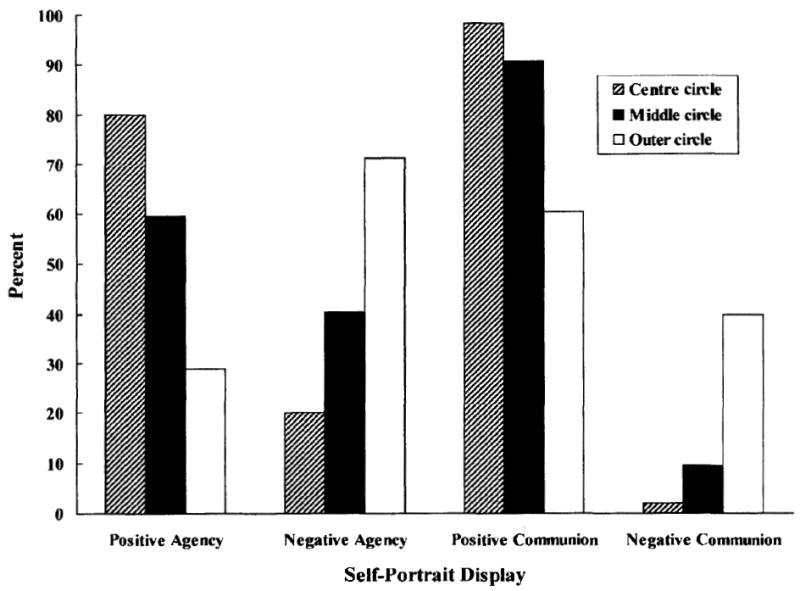

Figure 1 shows the distribution of agency- and communion-related attributes across the circles of the self-portrait display. As can be seen in Figure 1, the majority of positive agency and communion words were placed in the centre circle of the self-portrait display. In contrast, the majority of negative agency- and communion-related attributes were placed in the outer circle of the self-portrait display. This main effect of self-portrait assignment was significant for positive agency words, F(2, 152) = 22.23, P < .001, η2 = .23, negative agency words, F(2, 152) = 60.65, p < .001, η2 = .45, and negative communion words, F(2, 152) = 14.93, p < .001, η2 = .17. For positive communion words, the main effect of self-portrait assignment was qualified by a significant Age Group × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction, F(4, 304) = 2.73, p < .05, η2 = .04, and a significant Sex × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction, .F(2, 152) = 5.46, p < .01, η2 = .07. Follow-up analyses showed, for the Age Group × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction, that middle-aged and older adults assigned significantly more positive communion words to the centre circle of the self-portrait display than young adults. Follow-up analyses for the Sex × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction showed that women assigned significantly more positive communion words to the centre circle and significantly fewer to the outer circle than men.3

Figure 1.

Distribution of agency- and communion-related attributes across circles of the self-portrait display.

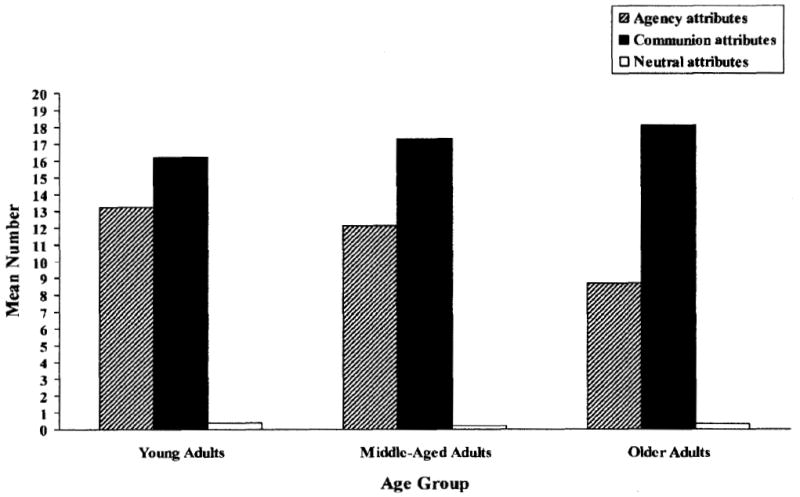

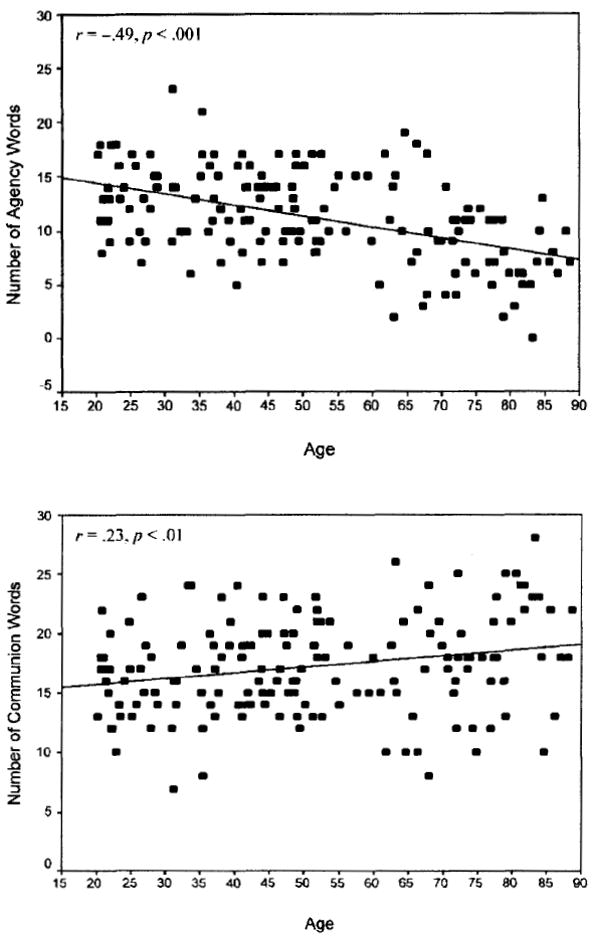

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the mean total number of agency- and communion-related attributes across age groups. Consistent with the focus on role-specific self-representations, the majority of spontaneously generated self-descriptors were classified as communion-related attributes (M = 17.20, SD = 4.06). To a lesser extent, adults’ self-representations reflected agency-related attributes (M = 11.28, SD = 4.15) and only a small number of attributes were classified as neutral (M = 0.34, SD = 0.70). The correlation between the total number of agency-related self-representations and participants’ age was −.49, p < .001; the correlation between the total number of communion-related self-representations and participants’ age was .23, p < .01. Figure 3 shows the association between age and the total number of agency-related (top panel) and communion-related (bottom panel) self-representations.

Figure 2.

Mean number of agency- and communion-related attributes across age groups.

Figure 3.

Relationship between age and agency attributes (top panel) and age and communion attributes (bottom panel).

Age and sex differences in agency-related attributes

A 3 (age group: young vs. middle-aged vs. old) × 2 (sex: men vs. women) × 3 (self-portrait assignment: centre vs. middle vs. outer circle) mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine age and sex differences in the total number of agency-related attributes.4 Age group and sex were between-subjects factors, whereas self-portrait assignment was a within-subjects factor. Self-portrait assignment was included to examine whether the importance of agency words in participants’ self-portrait differed by age group or sex.

This analysis showed significant main effects of age group, F(2, 152) = 28.25, p < .001, η2 = .27, sex, F(1, 152) = 9.58, p < .01, η2 = .06, and self-portrait assignment, F(2, 152) = 12.11, p < .001, η2 = .14. None of the interactions with self-portrait assignment reached the .05 level of significance. The means and standard deviations resulting from this analysis are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Age and sex differences in number of agency-related attributes

| Centre circle

|

Middle circle

|

Outer circle

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Young adults | ||||||

| Men (n = 25) | 3.80 | 2.58 | 3.96 | 2.64 | 6.04 | 3.09 |

| Women (n = 27) | 3.59 | 3.02 | 3.56 | 2.69 | 5.56 | 2.79 |

| Middle-aged adults | ||||||

| Men (n = 25) | 4.28 | 2.42 | 3.28 | 2.23 | 5.24 | 2.52 |

| Women (n = 26) | 3.62 | 2.58 | 3.08 | 1.65 | 4.73 | 3.23 |

| Older adults | ||||||

| Men (n = 30) | 3.30 | 2.07 | 2.93 | 2.18 | 3.50 | 2.40 |

| Women (n = 25) | 2.08 | 2.12 | 1.96 | 1.74 | 2.96 | 1.99 |

Post hoc analyses using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) method showed for the main effect of age group that young (M = 13.23, SD = 3.64) and middle-aged (M = 12.10, SD = 3.14) subjects included significantly more agency attributes in their self-representations than older adults (M = 8.49, SD = 3.98). Post hoc analyses with regard to the main effect of sex showed that men (M = 11.96, SD = 3.82) listed significantly more agency words in their self-representations compared to women (M = 10.45, SD = 4.32). Post hoc analyses with regard to self-portrait assignment showed that the outer circle (M = 4.65, SD = 2.88) contained significantly more agency words than the middle circle (M = 3.13, SD = 2.27) and the centre circle (M = 3.44, SD = 2.53).

Age and sex differences in communion-related attributes

A 3 (age group) × 2 (sex) × 3 (self-portrait assignment) mixed model ANOVA was performed to examine age and sex differences in the total number of communion attributes. Again, self-portrait assignment was included to examine whether the assignment of communion-related attributes to different circles of the self-portrait differed by age group or sex.

This analysis showed significant main effects of age group, F(2, 152) = 4.37, p < .05, η2 = .05, sex, F(1, 152) = 11.03, p < .01, η2 = .07, and self-portrait assignment, F(2, 152) = 325.70, p < .001, η2 = .60. In addition, there was a significant Age Group × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction, F(4, 304) = 2.90, p < .05, η2 = .04, and a significant Sex × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction, F(2, 152) = 3.64, p < .05, η2 = .05. The Age Group × Sex interaction and the three-way interaction failed to reach the .05 level of significance. The means and standard deviations resulting from this analysis are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Age and sex differences in number of communion-related attributes

| Centre circle

|

Middle circle

|

Outer circle

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Young adults | ||||||

| Men (n = 25) | 7.60 | 3.69 | 5.64 | 3.12 | 1.92 | 1.87 |

| Women (n = 27) | 9.41 | 3.95 | 5.85 | 3.10 | 1.89 | 1.91 |

| Middle-aged adults | ||||||

| Men (n = 25) | 9.40 | 3.56 | 5.28 | 2.28 | 1.76 | 2.15 |

| Women (n = 26) | 11.62 | 3.95 | 4.92 | 2.76 | 1.58 | 1.72 |

| Older adults | ||||||

| Men (n = 30) | 10.33 | 3.99 | 5.17 | 2.46 | 1.63 | 1.45 |

| Women (n = 25) | 12.08 | 5.16 | 6.00 | 4.26 | 1.52 | 1.69 |

Post hoc analyses showed for the main effect of age group that older adults (M = 18.25, SD = 4.70) included significantly more communion-related attributes in their self-representations than young adults (M = 16.19, SD = 3.78). This main effect, however, was qualified by a significant Age Group × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction. Specifically, middle-aged (M = 10.53, SD = 3.89) and older adults (M = 11.13, SD = 4.60) listed significantly more communion words in the centre circle of their self-portrait display compared to young adults (M = 8.54, SD = 3.90). Thus, middle-aged and older adults considered, on average, more communion words as most important for their self-representations than younger adults.

Post hoc analyses with regard to the main effect of sex showed that women’s self-representations (M = 18.26, SD = 4.09) included significantly more communion-related attributes compared to men’s (M = 16.30, SD = 3.74); t(157) = −3.14, p < .01. However, this main effect was qualified by a significant Sex × Self-Portrait Assignment interaction. In particular, women (M = 11.00, SD = 4.48) included significantly more communion-related attributes in the centre circle of their self-portrait display than men (M = 9.19, SD = 3. 89). There were no significant sex differences with regard to the other circles of the self-portrait display.

Post hoc analyses with regard to the main effect of self-portrait assignment showed that the centre circle (M = 10.08, SD = 4.27) contained significantly more communion words than the middle circle (M = 5.47, SD = 3.02) and the outer circle (M = 1.72, SD = 1.78). The difference between the mean number of communion words in the middle circle and the outer circle was also significant.

Associations between agency and communion orientations and measures of personality

Associations between agency and communion orientations and measures of personality were examined in two ways. First, the correlations between the total number of agency and communion words and measures of personality were calculated. Second, because agency- and communion-related words assigned to the centre circle of the self-portrait display may be of particular importance to adults’ self-definitions, we also examined the associations between the number of agency and communion words in the centre circle and measures of personality. Table 4 shows the resulting correlations with the five factors of the NEO-FFI and the five defence mechanisms assessed by the DMI.

Table 4.

Correlations between agency and communion attributes and measures of personality (N = 158)

| Agency attributes

|

Communion attributes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Self-portrait display | Centre circle | Self-portrait display | Centre circle |

| NEO-Five Factor Inventory | ||||

| Neuroticism | −.01 | .03 | .14 | −.02 |

| Extraversion | −.01 | −.02 | .01 | .17* |

| Openness to experience | .23** | .19* | −.12 | .01 |

| Agreeableness | −.27** | −.19* | .25** | .29** |

| Conscientiousness | −.18* | .04 | .09 | .19* |

| Defence Mechanisms Inventory | ||||

| Turning against object | .42*** | .30*** | −.28*** | −.27** |

| Projection | .24** | .19* | −.14 | −.15 |

| Principalisation | −.09 | −.09 | .09 | .11 |

| Turning against self | −.30*** | −.21** | .23** | .10 |

| Reversal | −.32*** | −.23** | .16* | .25** |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

As can be seen in Table 4, the total number of agency words showed a significant positive correlation with openness to experience and significant negative correlations with agreeableness and conscientiousness. The number of agency words in the centre circle of the self-portrait display correlated positively with openness to experience and negatively with agreeableness. Thus, adults who included a greater number of agency-related attributes in their self-representations tended to be more open to new experiences, less agreeable with others, and less conscientious in their actions. In contrast, the total number of communion words and the number of communion words in the centre circle correlated positively with agreeableness. In addition, the number of communion words in the centre circle of the self-portrait display also correlated significantly with conscientiousness. Thus, adults who included a greater number of communion-related attributes in their self-representations tended to be more agreeable with others and more conscientious in their actions.

The total number of agency words and the number of agency words in the centre circle showed significant positive correlations with the defence mechanisms turning against object and projection and significant negative correlations with turning against self and reversal. In contrast, the total number of communion words showed a significant negative correlation with the defence mechanisms turning against object and significant positive correlations with the defence mechanisms turning against self and reversal. With the exception of the correlation with turning against self, this pattern also held for the number of communion words included in the centre circle of the self-portrait display.

Associations between communion and agency and psychological well-being

Table 5 shows the bivariate correlations between the number of agency and communion words and adults’ scores on six dimensions of psychological well-being. As can be seen in Table 5, none of the correlations for agency words reached the .05 level of significance. For the number of communion words assigned to the centre circle of the self-portrait display four of the six correlations were statistically significant. Specifically, the number of communion words in the centre circle showed positive correlations with self-acceptance, environmental mastery, positive relations with others, and purpose in life. Thus, adults who assigned a larger number of communion words to the centre circle of their self-portrait display tended to have higher scores on these dimensions of psychological well-being.

Table 5.

Correlations between agency and communion attributes and scales of psychological well-being (N = 158)

| Agency attributes

|

Communion attributes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Self-portrait display | Centre circle | Self-portrait display | Centre circle |

| Self-acceptance | −.04 | −.01 | −.02 | .20* |

| Environmental mastery | −.09 | −.01 | .01 | .23** |

| Positive relations with others | −.11 | −.10 | .12 | .23** |

| Personal growth | .11 | .11 | −.01 | .14 |

| Purpose in life | −.01 | .02 | .01 | .19* |

| Autonomy | −.06 | .05 | −.10 | .09 |

p < .05;

p < .01.

Age and sex differences in the ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes

A 3 (age group) × 2 (sex) ANOVA with the ratio between the total number of agency- and communion-related attributes as dependent variable was performed to examine age and sex differences. This analysis yielded a significant main effect for age group, F(2, 152) = 9.12, p < .001, η2 = .11, and a significant main effect for sex, F(2, 152) = 5.75, p <.05, η2 = .04. The Age Group × Sex interaction did not reach the .05 level of statistical significance. The means and standard deviations resulting from this analysis are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Age and sex differences in the ratio between agency and communion attributes

| Men

|

Women

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | M | SD | M | SD |

| Young adults (n = 52) | 1.03 | 0.59 | 0.83 | 0.48 |

| Middle-aged adults (n = 51) | 0.82 | 0.28 | 0.68 | 0.31 |

| Older adults (n = 55) | 0.65 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.46 |

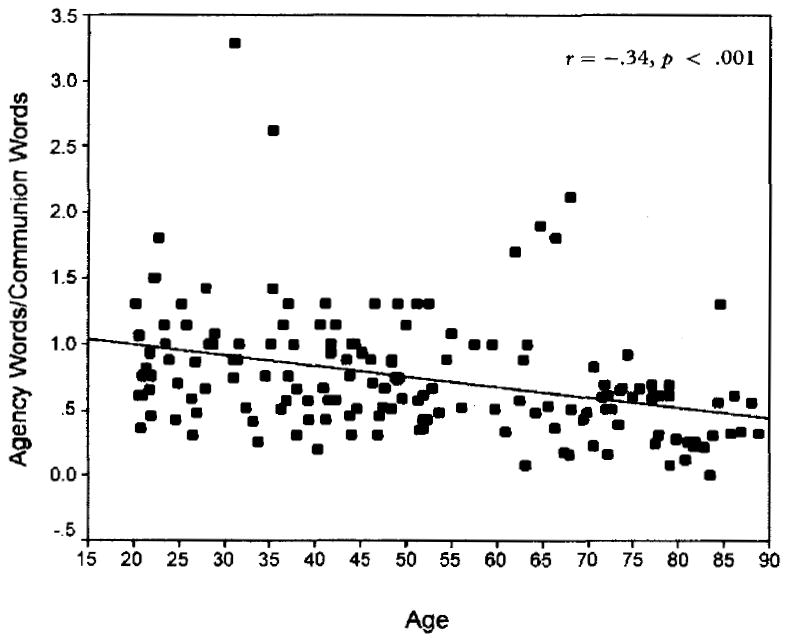

Post hoc analyses for the main effect of age group showed that the mean ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes was significantly smaller for older adults (M = .57, SD = .45) than for younger adults (M = .93, SD = .54). The mean differences between young and middle-aged adults and middle-aged and older adults were not statistically significant. Figure 4 shows the association between age and the ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes. Follow-up analyses for the main effect of sex revealed that the mean ratio was significantly smaller for women (M = .67, SD = .44) than the mean ratio for men (M = .82, SD = .47), t(157) = 2.08, p < .05.

Figure 4.

Relationship between age and the ratio between agency- and communion-related attributes.

Discussion

This study used an adult life-span sample to examine agency and communion orientations in individuals’ spontaneous self-representations. Findings showed that the content of adults’ spontaneous self-representations could be reliably coded in terms of agency and communion. This suggests that these “two fundamental modalities” (Bakan, 1966, p. 14) structure adults’ self-construals and are (more or less) consciously available in their self-representations. This general finding is of interest because this study did not use the usual self-report measures to assess agency and communion (see Helgeson & Fritz, 1999). Rather, the approach taken in this study was indirect and showed that agency and communion are implicit dimensions along which adults structured their role-specific self-representations (Blatt & Blass, 1996).

Unlike most research on agency and communion, the results reported here were obtained with a sample covering the whole adult life span (see also Helgeson & Fritz, 1999; McAdams, Hoffman, Mansfield, & Day, 1996, Study 2 and 3; Smith et al., 1998). As expected, the total number of agency-related attributes in adults’ self-representations was negatively correlated with age, whereas the total number of communion-related attributes showed a positive association with age. This suggests that with increasing age, adults seem to incorporate more other-related attributes into their self-representations and seem to downplay the attributes that are indicative of achievement, independence, and power. This interpretation was further supported by findings from content analyses showing that the reduction in agency-related attributes with age was mostly due to a smaller number of negative agency words (e.g., angry, arrogant, aggressive, cynical, vindictive). In contrast, positive agency words (e.g., confident, creative, determined, forceful, self-reliant) were included with the same frequency across age groups.

Overall, the distribution of attributes in adults’ self-representations showed that about 40% were agency-related, whereas about 60% were communion-related. The majority of positive agency and communion attributes were placed in the centre of adults’ self-portraits. This latter finding is consistent with a large body of literature documenting the positivity bias in self-representations in the service of self-affirmation and self-enhancement (Steele, 1988; Swann, 1990). This finding also lends further support to the validity of the procedure used in the present research.

Age and sex differences in agency and communion attributes

Analyses of variance provided support for our hypotheses regarding age and sex differences. With regard to age differences, young and middle-aged adults included a significantly larger number of agency attributes in their self-representations than older adults. Conversely, older adults listed more communion-related attributes as part of their self-representations than young adults. These findings are consistent with general theorising on adult development (Blatt & Blass, 1996; Erikson, 1950, 1982; Franz & White, 1985; Labouvie-Vief, 1994) and with research on generativity in adulthood (Ackerman et al., 2000; MacDermid et al., 1998; McAdams et al., 1996). Moreover, these findings are consistent with research on the developmental tasks defined by different life periods, which indicates that the focus in early adulthood is on gaining independence from the family of origin and on committing to a professional career and stable interpersonal relationships (Arnett, 2000). In contrast, developmental tasks in middle and late adulthood are related to using one’s professional status to mentor others, to raise and guide the next generation, to draw on significant others in coping with the challenges of the ageing process, and to provide support to others as they negotiate the diverse challenges in their lives (see Aldwin & Levenson, 2001; Antonucci, Akiyama, & Merline, 2001; Lachman & James, 1997; MacDermid et al., 1998).

With regard to sex differences, findings from this study showed that men included more agency-related attributes in their self-representations than women. Conversely, women included more communion-related attributes in their self-representations than men. These findings are consistent with a large body of research on sex-role socialisation (Eagly, 1987; Helgeson, 1994; Maccoby, 1990; Ruble & Martin, 1998). In describing the different self-construals of men and women, Cross and Madson (1997) stated that “The social, institutional, and cultural environment of the United States promotes development of independence and autonomy in men and interdependence and relatedness in women” (p. 5).

For communion-related attributes, the main effects of age and sex were qualified by significant interactions with self-portrait assignment. In particular, middle-aged and older adults listed significantly more communion attributes in the centre of their self-portrait display than young adults; similarly, women included significantly more communion attributes in the centre of their self-portrait display than men. These findings underscore the importance of relatedness for adults’ self-definitions and suggest that this importance increases as individuals grow older (Carstensen, 1993).

Associations of agency and communion with personality and psychological well-being

Examination of the associations of agency- and communion-related attributes with personality traits and defence mechanisms yielded a number of interesting findings. Specifically, the number of agency attributes showed a positive association with openness to experience and negative associations with agreeableness and conscientiousness. This means that individuals who listed more agency-related attributes in their self-representations tended to score higher on a personality dimension indicative of a person’s willingness to entertain novel ideas and to endorse unconventional values. Conversely, these individuals tended to score lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness, suggesting that they were less sympathetic toward others and more inclined to follow their own impulses (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

In contrast, communion attributes showed positive correlations with extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. This means that individuals who include more communion-related attributes in their self-representations tended to be socially more outgoing, more sympathetic toward others, and more purposeful and self-controlled in their behaviour (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Overall, the magnitude of the intercorrelations was modest, but provided evidence for the convergent validity of the agency and communion assessment used in this study (see also McAdams et al., 1996).

In terms of the associations of agency and communion with defence mechanisms, our analyses revealed significant positive associations of the total number of agency attributes with turning against object and projection, and significant negative correlations with turning against self and reversal. This means that individuals who included more agency-related attributes in their self-representations tended to endorse strategies of conflict management that direct aggressive impulses toward others and assign undesirable qualities to others. Conversely, these individuals tended to be less inclined to direct feelings of conflict toward their own person or to reinterpret the negative aspects of a given situation. These correlations are consistent with the general definition of agency orientation and indicate that high agency scores often tend to be associated with antagonistic behaviour and with more externalising defences.

In comparison, the total number of communion attributes showed significant negative correlations with turning against object and projection, and significant positive correlations with turning against self and reversal. This means that individuals who included more communion-related attributes in their self-representations tended to direct their aggressive impulses toward their own person and were more likely to downplay the negative aspects of a given situation. Overall, these correlations are consistent with the description of communion-oriented individuals as being concerned about interpersonal harmony, being accommodating to others, and being able to focus on the bright side of difficult situations. These findings also suggest that communion-oriented individuals may use developmentally more mature defence mechanisms when confronted with challenging situations. This finding is consistent with results from several studies showing positive associations between age and mature coping strategies (see Diehl et al., 1996; Helson & Wink, 1987; Vaillant, 1993).

Examination of the associations of agency and communion attributes with dimensions of psychological well-being showed only significant correlations for communion-related attributes. Specifically, individuals who included more communion-related attributes in the centre circle of their self-portrait display tended to have (a) a more positive attitude toward their own person (i.e., self-acceptance); (b) a greater sense of mastery and competence in managing the environment (i.e., environmental mastery); (c) warm, satisfying, and trusting relationships with others (i.e., positive relations with others); and (d) a deeper sense of meaning for their present or past life (i.e., purpose in life). Although the significant correlations were small in magnitude, they are consistent with a large body of research showing that being socially embedded and having meaningful relationships with others has a number of beneficial effects in terms of physical and mental health (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Ryff & Singer, 1998).

Finally, findings from an analysis of variance failed to support the hypothesis that with increasing age the relative importance of agency attributes compared to communion attributes increases for women, whereas the opposite pattern can be expected for men. Instead, we found that across age groups both men and women tended to include more communion-related attributes in their self-representations. This finding is consistent with Erikson’s (1950, 1982) notion of an increasing focus on others and increasing concerns with generativity over the course of adulthood. Although we did not measure our participants’ concern about generativity, this finding is consistent with findings from studies on the role of agency and communion in the context of generative behaviour (Ackerman et al., 2000; MacDermid et al., 1998; McAdams et al., 1996).

Limitations

This study has several strengths, including the use of a heterogeneous adult life-span sample and the use of role-specific self-representations to obtain a measure of individuals’ agency and communion orientations. Despite these strengths, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, because the assessment of agency and communion was done in the context of a secondary analysis, this study did not include another measure of these constructs. Thus, we were not able to examine the convergent validity of our measure directly with an established measure of agency and communion. However, the obtained correlations with personality factors, defence mechanisms, and dimensions of psychological well-being were consistent with the theoretical meaning of these constructs and comparable to correlations obtained with established measures of agency and communion (Ackerman et al., 2000; McAdams et al., 1996).

Second, although the self-concept assessment in terms of role-specific self-representations can be considered one of the strengths of this study, it also needs to be acknowledged that this approach, by definition, may have biased adults’ spontaneous self-representations in favour of communal attributes. Although this method artifact cannot be ruled out, our data show that study participants nevertheless included a considerable number of agentic attributes in their self-representations. Additional studies are needed to address this issue and to determine the effect of specific instructional sets on the content of adults’ spontaneous self-representations (see Labouvie-Vief, Chiodo, Goguen, Diehl, & Orwoll, 1995).

Third, the cross-sectional nature of the reported data confounds the effects of age and cohort and thus limits the developmental conclusions that can be drawn from this study (Schaie, 1994). Only under the assumption that the effect of cohort on adults’ self-representations is negligible can the age differences found in this study be interpreted as being indicative of age-related change. A more detailed knowledge about the change trajectories of agency and communion orientations in adulthood and their associations with markers of physical and psychological health requires longitudinal data.

Concluding remarks

In summary, this study showed that agency and communion were implicit dimensions of adults’ spontaneous self-representations. Findings with regard to age differences showed that middle-aged and older adults included significantly more communion attributes in their self-representations, suggesting that relatedness may become more important with age. Findings with regard to sex differences were consistent with the literature on sex-role socialisation, showing that men tend to emphasise agency-related/independent self-representations, whereas women tend to emphasise communion-related/ interdependent self-representations. Findings from correlational analyses showed significant associations with broad factors of personality, defence mechanisms, and dimensions of psychological well-being, lending support to the convergent validity of the assessment used in this study.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this study was in part supported by grant AG19328 from the National Institute on Aging to Manfred Diehl.

Appendix A

Definition of agency and communion for rater training

According to the psychologist David Bakan (1966), agency and communion are two fundamental modalities that human beings display in their orientation toward the world around them. In the following, we are providing prototypical definitions of both terms. You need to use these definitions when you rate the attributes in study participants’ self-portrait displays. Please note that agency and communion can be expressed in a positive and a negative form.

Agency

Agency refers to a person’s striving to be separate from others, to master the environment, and to assert, protect, and expand the self. Individuals who score high on agency are usually powerful and autonomous “agents,” they are highly individualistic, they like to dominate and lead, they want to be a force to be reckoned with. In its positive form, high agency orientation is found in skillful leaders who enjoy challenging tasks, are ambitious, self-confident and creative, and can lead a project to success—even in the face of obstacles. In its negative form, high agency orientation is expressed by “hunger for power and dominance” and is often expressed by reckless, abrasive, and selfish/self-centred behaviour toward others.

Communion

Communion refers to a person’s striving to lose his or her own individuality by merging with others. Individuals who score high on communion enjoy participating in something that is larger than the self. They enjoy relating to other persons in warm, close, intimate, and loving ways. In its positive form, high communion orientation is found in persons who can easily give up or delay their individual needs and wishes for the common good. They are usually great team players and can collaborate with others smoothly and in constructive ways. Also, they are usually good in understanding others’ feelings and are able to respond with empathy and thoughtful understanding. In its negative form, high communion orientation is found in persons who always want to please others and are extremely dependent on the approval and opinion of others. These individuals are devastated if their needs for “union and merging with others” are not reciprocated by these others and they feel rejected and worthless. These individuals, in general, have given up any kind of sense of individuality and self-worth. In Appendices B and C are lists of words that you can consult in rating the descriptors in study participants’ self-portrait diagrams. Although this list is not exhaustive, it contains the most frequent agency and communion words that we were able to identify in the relevant literature.

Appendix B

| Agency words | |||||

| Conquer | Dominant | Inventive | Master | Enterprising | Opportunistic |

| Controlling | Forceful | Outspoken | Overcome | Independent | Sharp-witted |

| Creative | Resourceful | Shrewd | Productive | Restless | Stern |

| Explorer | Sophisticated | Strong | Persuasive | Stubborn | Tough |

| Advocate | Wise | Vindictive | Analytical | Arrogant | Competitive |

| Understand (seeks to) | Autocratic | Decisive | Winning/Winner | Conceited | Leader |

| Aggressive | Confident | Determined | Ambitious | Cynical | Secure |

| Adventurous | Deliberate | Individualistic | Assertive | Intelligent/Smart | Self-reliant |

| Autonomous | Foresighted | Self-sufficient | Clever | Hard-headed | Risk taker |

| Courageous | Industrious | Energetic | Daring | Ingenious | Angry |

Appendix C

| Communion words | |||||

| Loving | Grateful | Praising | Intimate (seeks intimacy) | Tactful | |

| Sentimental | |||||

| Unite with others | Conscientious | Sincere | Caring | Neat | Submissive |

| Nurturing | Creative | Talkative/sharing experiences | |||

| Cooperative | Religious | Timid | Encouraging | Home-oriented | Worrying |

| Communicate | Appreciative | Cheerful | Sharing | Considerate | Compassionate |

| Affectionate | Contended | Flatterable | Charming | Dependent | Gullible |

| Altruistic | Emotional | Loyal | Enticing | Fearful | Shy |

| Gentle | Fickle | Tender | Kind | Forgiving | Yielding |

| Loyal | Friendly | Role model | Sensitive | Frivolous | Interested |

| Sociable | Helpful | Understanding | Sympathetic | Jolly | Warm |

| Modest | |||||

Footnotes

In an earlier study (Diehl, Hastings, & Stanton, 2001), we addressed concerns about the fact that some participants received a compensation (i.e., extra credit) for their participation, whereas others (mostly middle-aged and older adults) did not. Specifically, we performed a series of analyses in which we compared the scores of those participants who had received extra credit to the scores of those participants who had not received compensation. Nineteen out of 24 comparisons (79.2%) did not reveal any significant differences (p < .05) between the two groups; 3 comparisons showed higher scores for the compensated participants, whereas 2 comparisons showed higher scores for the noncompensated group. On the basis of these results, we believe it is reasonable to conclude that the compensation to some of the participants did not bias the findings in any major way (see also Gribbin & Schaie, 1976).

Analyses reported elsewhere showed that the order of administration did not prime participants to create their self-representations in specific ways (Diehl et al., 2001).

Tables containing the means and standard deviations from these analyses can be obtained from the first author.

Following the suggestion of one reviewer, we also performed the analyses with age as a continuous variable. These analyses yielded virtually identical results. Because this study focused on age and sex differences, we opted to present the findings as mean-level data.

Contributor Information

Manfred Diehl, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA.

Stephanie K. Owen, University of Oregon, Eugene, USA

Lise M. Youngblade, University of Florida, Gainesville, USA

References

- Ackerman S, Zuroff DC, Moskowitz DS. Generativity in midlife and young adults: Links to agency, communion, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2000;50:17–41. doi: 10.2190/9F51-LR6T-JHRJ-2QW6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin CM, Levenson MR. Stress, coping, and health at midlife: A developmental perspective. In: Lachman ME, editor. Handbook of midlife development. New York: Wiley; 2001. pp. 188–214. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Akiyama H, Merline A. Dynamics of social relationships in midlife. In: Lachman ME, editor. Handbook of midlife development. New York: Wiley; 2001. pp. 571–598. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakan D. The duality of human existence: Isolation and communion in Western man. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz L. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:226–244. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. How the self became a problem: A psychological review of historical research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachment as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky MF, Clinchy BM, Goldberger NR, Tarule JM. Women’s mays of knowing. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. Bem Sex Role Inventory professional manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Blass RB. Relatedness and self-definition: A dialectic model of personality development. In: Noam GG, Fischer KW, editors. Development and vulnerability in relationships. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1996. pp. 309–338. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent–child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In: Jacobs JE, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: vol. 40. Developmental perspectives on motivation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1993. pp. 209–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway M, Pizzamiglio MT, Mount L. Status, communality, and agency: Implications for stereotypes of gender and other groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:25–38. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. RevisedNEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Coyle N, Labouvie-Vief G. Age and sex differences in strategies of coping and defense across the life span. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:127–139. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Elnick AB, Bourbeau LS, Labouvie-Vief G. Adult attachment styles: Their relations to family context and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1656–1669. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl M, Hastings CT, Stanton JM. Self-concept differentiation across the adult life span. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:543–654. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. The life cycle completed. New York: Norton; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:429–456. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz CE, White KM. Individuation and attachment in personality development: Extending Erikson’s theory. Journal of Personality. 1985;53:224–256. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In: Strachey J, editor. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 7. London: Hogarth Press; 1953. Original work published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Gergen KJ. The saturated self: Dilemmas of identity in contemporary life. New York: Basic Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan C. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde PF. Alternative pathways to chronic depressive symptoms in young adults: Gender differences in developmental trajectories. Child Development. 1995;66:1277–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough HG, Heilbrun AL. The adjective checklist manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Gribbin K, Schaie KW. Monetary incentive, age, and cognition. Experimental Aging Research. 1976;2:461–468. doi: 10.1080/03610737608258003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger S, Blatt S. Individuality and relatedness. American Psychologist. 1994;49:104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann D. Reclaimed powers: Men and women in later life. 2. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Haan N. Coping and defending: Processes of self-environment organization. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Monsour A. Developmental analysis of conflict caused by opposing attributes in the adolescent self-portrait. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS. Relation of agency and communion to well-being: Evidence and potential explanations. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:412–428. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Fritz HL. Unmitigated agency and unmitigated communion: Distinctions from agency and communion. Journal of Research in Personality. 1999;33:131–158. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Fritz HL. The implications of unmitigated agency and unmitigated communion for domains of problem behavior. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1031–1057. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helson R, Moane G. Personality change in women from college to midlife. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:176–186. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helson R, Wink P. Two concepts of maturity examined in the findings of a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;53:531–541. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihilevich D, Gleser GC. Defense mechanisms: Their classification, correlates, and measurement with the Defense Mechanisms Inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jung CG. In: Modem man in search of a soul. Dell WS, Baynes CF, editors. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World; 1962. Original work published 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G. Psyche and Eros: Mind and gender in the life course. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie-Vief G, Chiodo LM, Goguen LA, Diehl M, Orwoll L. Representations of self across the life span. Psychology and Aging. 1995;10:404–415. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.10.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, James JB, editors. Multiple paths of midlife development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DJ, Darrow CN, Klein EB, Levinson MH, McKee B. The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Ballantine; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Livson FB. Paths to psychological health in the middle years: Sex differences. In: Eichorn DH, Clausen JA, Haan N, Honzik MP, Mussen PH, editors. Present and past in middle life. New York: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 195–221. [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger J. Ego development: Conceptions and theories. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist. 1990;45:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermid S, Franz CE, DeReus L. Adult character: Agency, communion, insight, and the expression of generativity in mid-life adults. In: Colby A, James J, Hart D, editors. Competence and character through life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1998. pp. 205–229. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. The stories we live by. New York: Harper Collins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP. The person: An integrated introduction to personality psychology. 3. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, de St Aubin E. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62:1003–1015. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Hoffman BJ, Mansfield ED, Day R. Themes of agency and communion in significant autobiographical scenes. Journal of Personality. 1996;64:339–375. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender differences in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Sheldon KM, Gable SL, Roscoe J, Ryan RM. Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL. Gender development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 5. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 933–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW. Developmental designs revisited. In: Cohen SH, Reese HW, editors. Life-span developmental psychology: Methodological contributions. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1994. pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Brennan KA. Attachment styles and the “Big Five” personality traits: Their connections with each other and with romantic relationship outcomes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1992;18:536–545. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW, Gallo LC, Goble L, Ngu LQ, Stark KA. Agency, communion, and cardiovascular reactivity during marital interaction. Health Psychology. 1998;17:537–545. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL, Stapp J. The Personality Attributes Questionnaire: A measure of sex role stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. Journal Supplement Abstract Service Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology. 1974;4:43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Steele C. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 21. New York: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB., Jr . To be adored or to be known? The interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification. In: Higgins ET, Sorrentino RM, editors. Handbook of motivation and cognition: Foundations of social behavior. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford; 1990. pp. 408–448. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant GE. The wisdom of the ego. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM. Gender and health: An update on hypotheses and evidence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985;26:156–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS. Agency and communion as conceptual coordinates for the understanding and measurement of interpersonal behavior. In: Grove & WM, Cicchetti D, editors. Thinking clearly about psychology: Vol 1. Personality and psychopathology. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1991. pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins JS, Trapnell PD. A dyadic-interactional perspective on the five-factor model. In: Wiggins JS, editor. The five-factor model of personality: Theoretical perspectives. New York: Guilford; 1996. pp. 88–162. [Google Scholar]