Abstract

Variation in penetrance estimates for BRCA1/2 carriers suggests that other environmental and genetic factors may modify cancer risk in carriers. The GSTM1, T1 and P1 isoenzymes are involved in metabolism of environmental carcinogens. The GSTM1 and GSTT1 gene is absent in a substantial proportion of the population. In GSTP1, a single-nucleotide polymorphism that translates to Ile112Val was associated with lower activity. We studied the effect of these polymorphisms on breast cancer (BC) risk in BRCA1/2 carriers. A population of 320 BRCA1/2 carriers were genotyped; of them 262 were carriers of one of the three Ashkenazi founder mutations. Two hundred and eleven were affected with BC (20 also with ovarian cancer (OC)) and 109 were unaffected with BC (39 of them had OC). Risk analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for origin (Ashkenazi vs non-Ashkenazi). We found an estimated BC HR of 0.89 (95% CI 0.65–1.12, P=0.25) and 1.11 (95% CI 0.81–1.52, P=0.53) for the null alleles of GSTM1 and GSTT1, respectively. For GSTP1, HR for BC was 1.36 (95% CI 1.02–1.81, P=0.04) for individuals with Ile/Val, and 2.00 (95% CI 1.18–3.38) for carriers of the Val/Val genotype (P=0.01). An HR of 3.20 (95% CI 1.26–8.09, P=0.01), and younger age at BC onset (P=0.2), were found among Val/Val, BRCA2 carriers, but not among BRCA1 carriers. In conclusion, our results indicate significantly elevated risk for BC in carriers of BRCA2 mutations with GSTP1-Val allele with dosage effect, as implicated by higher risk in homozygous Val carriers. The GSTM1- and GSTT1-null allele did not seem to have a major effect.

Keywords: breast cancer, BRCA1/2, glutathione-S-transferase, GSTP1 polymorphism, modifiers

The variability of cancer risk among BRCA1/2 carriers (Struewing et al, 1997; Ford et al, 1998; Thorlacius et al, 1998; Antoniou et al, 2003) suggests a role for environmental and genetic modifiers. The impaired DNA-repair mechanism in carriers of BRCA1/2 mutation (Boulton, 2006) may result in higher vulnerability to reduced activity of other genes that participate in maintaining genome stability. The glutathione-S-transferase superfamily of enzymes participates in protection against exogenous and endogenous oxidative damage (Hayes and Pulford, 1995). They conjugate xenobiotics, such as herbicides, insecticides and other environmental carcinogens, and anticancer agents (alkylating agents, platinum compounds) to glutathione to facilitate excretion. In addition, endogenous electrophile molecules produced through metabolism of lipid and DNA products of oxidative stress, as well as oxidative metabolites of oestrogen, the catechol oestrogen, are detoxified by these enzymes (Cavalieri et al, 2000; Dawling et al, 2004).

Homozygous absence of both alleles coding for the GSTM1 (Seidegard et al, 1985) and GSTT1 (Pemble et al, 1994) are commonly found in various populations (50 and 20% respectively; Rebbeck, 1997). Elevated DNA adducts, sister-chromatid exchange and somatic genetic mutation have been demonstrated in carriers of null GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotypes (Rebbeck, 1997). In GSTP1 gene, a polymorphism of A315G encodes substitution of the wild-type isoleucine to valine at position 105 (Ile105Val). The valine variant was reported to have a reduced activity when recombinantly expressed in Escherichia coli (Zimniak et al, 1994).

The role of these genes in breast cancer (BC) has been evaluated through numerous case–control studies yielding conflicting results. In a meta-analysis in 1999 (Dunning et al, 1999), the GSTP1 Ile/Val genotype had odds ratio (OR) for BC of 1.6 (P=0.02). GSTM1 was significantly associated with postmenopausal BC and for GSTT1, a moderate effect of 1.5 risk elevation could not be excluded. A recent large case–control study in Shanghai observed an elevated BC risk of approximately 2 among the GSTP1-val homozygotes, which was similar among pre- and postmenopausal women (Egan et al, 2004). The authors also reported an updated meta-analysis based mainly on studies in the Caucasian population, which supports null results for these three polymorphisms. A subsequent pooled analysis based on approximately 2000 cases and controls was also negative for the three GST polymorphisms (Vogl et al, 2004).

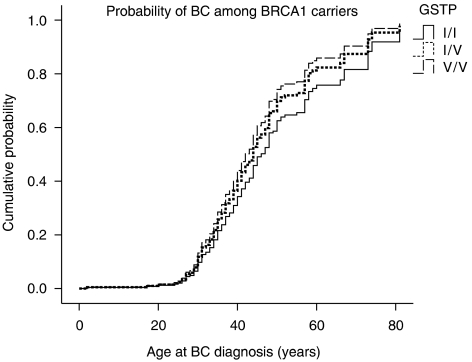

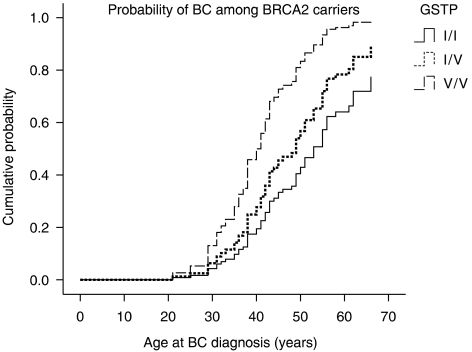

In this study, we report the effect of these polymorphisms on BC risk and age at onset among BRCA1/2 carriers (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Probabilities of BC with age according to GSTP1 genotypes (Ile/Ile, Ile/Val, Val/Val) among BRCA1 carriers (analyses were adjusted to origin, Ashkenazi vs non-Ashkenazi).

Figure 2.

Probabilities of BC with age according to GSTP1 genotypes (Ile/Ile, Ile/Val, Val/Val) among BRCA2 carriers (analyses were adjusted to origin, Ashkenazi vs non-Ashkenazi).

METHODS

Subjects and methods

Study population

The study population has been reported previously (Kadouri et al, 2004a). In summary, blood samples from 320 BRCA1/2 carriers were collected through two centres: 240 carriers were identified by the oncology department and the cancer genetic clinic in the Hadassah Medical Centre in Jerusalem, Israel, and 80 at the cancer genetic carrier clinic in the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. Cases were tested on the basis of a family history of BC and/or ovarian cancer (OC), or on the basis of their Ashkenazi origin. All the cases from Jerusalem were of Ashkenazi origin; of them all, but one, carried one of the three Ashkenazi founder mutations (132 cases: 185delAG, 32 cases: 5382insC in BRCA1 and 75 cases: 6174delT in BRCA2, one carried other BRCA2 mutations). The carriers from UK included 23 carriers of the Ashkenazi founder mutations (12 cases: 185delAG, 5 cases: 5382insC and 5 cases: 6174delT and two carriers of both 185delAG and 6174delT) and 56 carriers of other mutations (47 BRCA1; 9 BRCA2, specific mutation have been reported elsewhere; Kadouri et al, 2004b). Of the 320 carriers, 191 were affected with BC, 39 with OC and 20 with both cancers. Seventy of the mutation carriers were unaffected.

Genotyping

DNA was salt-extracted from blood samples by standard methods. GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotypes were determined by PCR amplification and agarose-gel electrophoresis. The INFA5 (5′--ggcacaacaggtagtaggcg--3′, 5′-gccacaggagcttctgacac-3′) gene was used as an internal control; this method conclusively identifies the null genotypes (homozygous deletion of the gene). Homozygous non-deleted and heterozygous genotypes were not distinguished from each other. The GSTP1 (Ile105Val) genotypes were determined by PCR–RFLP. For all PCR reactions, 25 ng of genomic DNA was used in a 15-μl reaction mixture containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 6 pM of each primer, 0.5 U of Amplitaq Gold polymerase (The Perkin Elmer Corp. Norwalk, CT, USA) and were run in a Hybaid Touchdown PCR machine. Primers were as follows: GSTM1, 5′--ctgccctacttgattgatggg--3′, 5′--ctggattgtagcagatcatgc--3′; GSTT1, 5′--ttccttactggtcctcacatctc--3′, 5′--tcaccggatcatggccagca--3′; GSTP1: 5′--acccagggctctatggggaa--3′, 5′--tgagggcacaagaagcccct--3′. Annealing temperature was 55°C for GSTM1 and GSTP1, and 66°C for GSTT1. Assignment of the GSTP1 Ile (ACA TCT) and Val (ACG TCT) genotype was made by digestion of the PCR products on the basis of the RFLP with BsmAI (New England Biolabs, Hertfordshire, UK). All PCR products were separated on 3% agarose gels with 2 μl/100 ml of ethidium bromide. Affected and unaffected samples were randomly located in the plates, a control sample was localised in each plate and five of the samples were genotyped twice with 100% concordance for the three genes. Call rates were high with one sample that could not be genotyped at all and an additional failure in GSTT1 and GSTP1 genotypes.

Statistical analysis

The effects of GST genotypes on BC risk in mutation carriers were evaluated using a COX proportional hazards model. Participants were followed up retrospectively from date of birth to several possible outcomes. The outcome in women affected with BC was recorded as the age at first BC diagnosis. Women unaffected with BC were censored at the date of OC diagnosis, prophylactic surgery, date of last follow upor death. Since distributions of age and disease status were different in the Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi populations, the analyses were adjusted for ethnic origin. Although selection of participants is partly based on outcome, this method of analysis was used previously for risk estimation in carriers (Rebbeck et al, 1999; Levy-Lahad et al, 2001; Kadouri et al, 2004a). In our study (Kadouri et al, 2001) on the modifying effect of the androgen receptor-CAG-repeat length in BRCA carriers, we compared COX proportional hazard models to a variant of the log rank designed to overcome selection bias by comparison of outcome to expected penetrance according to the literature. Since estimated risks were almost similar in both methods, in the current paper we have used COX proportional hazards models. The GSTM1 and GSTT1 genotypes were classified as either null (i.e., homozygous deletion) or non-deleted (i.e., heterozygous or homozygous for the presence of the gene). For GSTP1 polymorphism, where there were more than two genotypes, ORs were compared with the more common genotype, the Ile homozygous genotype. Comparison of ages at BC onset were calculated by ANOVA. We adjusted the P-values for multiple comparisons following HOLM's procedure both for pairwise comparisons of origin (Ashkenazi/non-Ashkenazi) with the GST genotypes and for the COX regression models as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. GSTM1, T1 and P1 allele frequencies and BC HR in BRCA1/2 carriers (adjusted for origin, Ashkenazi vs non-Ashkenazi).

| Genotype | BC− (n=109) no. (%) | BC+ (n=211) no. (%) | Average age at BC onset (years) | Breast cancer HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSTM1 (n=320) | |||||

| Present | 46 (42.2) | 106 (50.2) | 41.4 | 1 | |

| Null | 63 (57.8) | 105 (49.8) | 42.9 | 0.89 (0.65–1.12) | 0.25a |

| GSTT1 (n=319) | |||||

| Present | 84 (77.8) | 158 (74.9) | 42.5 | 1 | |

| Null | 24 (22.2) | 53 (25.1) | 41.3 | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 0.53b |

| GSTP1 (n=319) | |||||

| Ile/Ile | 76 (70.6) | 121 (57.3) | 42.1 | 1 | |

| Ile/Val | 29 (26.6) | 74 (35.1) | 42.6 | 1.36 (1.02–1.81) | 0.04c |

| Val/Val | 3 (2.8) | 16 (7.6) | 40.5 | 2.00 (1.18–3.38) | 0.01d |

BC−, no BC; BC+, with BC; CI, confidence interval; HI, hazard ratio.

Corresponding P-values after correction for multiple comparisons are as follows: a0.50, b0.53, c0.12 and d0.03.

RESULTS

The frequency of the GSTM1- and GSTT1-null and GSTP1 alleles in our Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi populations were as follows: GSTM1 null in 52.1 vs 55.2% (P=0.77) and GSTT1 null in 10.5 vs 26.6% (P=0.03), respectively. GSTP1 Ile/Ile, Ile/Val and Val/Val were found in 64.6, 30.4 and 4.9% of the Ashkenazi population, compared with 49.1, 40.4 and 10.5% in non-Ashkenazi, respectively (P=0.03), and all were in Hardy–Weinberg in both populations.

Table 1 shows the frequencies of the GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 genotypes in BRCA1/2 carriers both with and without BC, and the corresponding hazard ratios (HR). The GSTM1- and GSTT1-null genotypes were not associated with BC risk. Frequency of the GSTM1-null allele was non-significantly lower in BC cases (49.8%) than in BC-free BRCA1/2 mutation carriers (57.8%), and the estimated HR was 0.89 (95% CI 0.65–1.12, P=0.25). The corresponding frequencies for the GSTT1-null allele were 25.1 and 22.2% in BC cases and in BC-free carriers with a non-significant HR of 1.11 (95% CI 0.81–1.52, P=0.53). There was, however, evidence of increasing BC risk with increasing number of GSTP1-Val alleles; the HR for developing BC was 1.36 (95% CI 1.02–1.81, P=0.04) and 2.00 (95% CI 1.18–3.38, P=0.01), respectively, for Ile/Val heterozygotes and Val/Val homozygotes, as compared with that for Ile/Ile homozygotes (see P-values after correction for multiple comparisons in the footnote of Table 1).

In a separate analysis for the role of GSTP1 genotypes in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers (Table 2, Figure 2), a significant effect was found among the BRCA2 carriers. The HR for developing BC was 1.50 (95% CI 0.86–2.59, P=0.6) and 3.20 (95% CI 1.26–8.09, P=0.01), respectively, for Ile/Val heterozygotes and Val/Val homozygotes, as compared with that for Ile/Ile homozygotes. Younger mean age of 41.2 years at BC onset was found among Val/Val homozygotes as compared with 46.6 years in Ile/Ile homozygotes (P=0.2). In BRCA1 carriers, the effect of the GSTP1-Val allele was non-significant (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2. GSTP1 allele frequencies and BC HR in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers (adjusted for origin, Ashkenazi vs non-Ashkenazi)a.

| BRCA1 (n=228) | BRCA2 (n=90) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSTP1 | BC− (n=78) no. (%) | BC+ (n=150) no. (%) | Breast cancer HR (95% CI, P) | BC− (n=29) no. (%) | BC+ (n=61) no. (%) | Breast cancer HR (95% CI, P) |

| Ile/Ile | 53 (67.9) | 86 (57.3) | 1 | 22 (75.9) | 35 (57.4) | 1 |

| Age at BC | 40.5 years | 46.6 years | ||||

| Ile/Val | 22 (28.2) | 54 (36) | 1.22 (0.87–1.72, P=0.24) | 7 (24.1) | 20 (32.8) | 1.50 (0.86–2.59, P=0.15) |

| Age at BC | 42.6 years | 42.6 years | ||||

| Val/Val | 3 (3.9) | 10 (6.7) | 1.38 (0.71–2.70, P=0.15) | 0 | 6 (9.8) | 3.20 (1.26–8.09, P=0.01) |

| Age at BC | 40.1 years | 41.2 years | ||||

BC−, no BC; BC+, with BC; CI, confidence interval; HI, hazard ratio.

aCompound heterozygotes were excluded from these analyses.

DISCUSSION

Our results do not show a major effect of the null genotypes of the GSTM1 and GSTT1 on BC risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. However, the GSTP1-Val/Val allele was associated with approximately twofold BC risk in BRCA1/2 carriers. In BRCA2 carriers, a significant HR of 3.2 was found in homozgotes for the Val allele, whereas the effect among BRCA1 carriers was non-significant. To our knowledge this is the first report of an effect of GST polymorphism in BRCA1/2 carriers. A major limitation of our study is the survival bias due to inclusion of individuals while alive. This is an important consideration also regarding previous genetic risk modifiers reported among BRCA1/2 carriers, since the effect of these modifiers on survival is unknown. The effect of the GST-Val allele on BC prognosis contradicted in previous studies (Goode et al, 2002; Yang et al, 2005). Therefore, larger studies based on incident cases are warranted.

The GSTP1 isoenzyme is highly expressed in the mammary epithelium, both in normal and in tumor cells (Forrester et al, 1990; Kelley et al, 1994). It has been shown that methylation of the promoter (Arai et al, 2006) and low expression of the GSTP1 gene is associated with poor prognosis in BC patients treated with chemotherapy (Arai et al, 2006). In addition to its role in detoxifying electrophilic molecules from exogenous exposures, the GSTP1 gene has an important role in the metabolism of estradiol derivatives (Cavalieri et al, 2000; Dawling et al, 2004). It reduces the concentration of oestrogen quinones, thereby reducing the potential of these oxidative oestrogen metabolites to induce DNA damage. It is possible that in cells, which are deficient in functional BRCA1 or BRCA2, key proteins in DNA-damage repair, the DNA will be vulnerable to oxidative damage. The role of the BRCA2 protein in DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair is well established (Boulton, 2006). The BRCA2 protein has a distal role in the DNA-repair machinery (Boulton, 2006). It forms a complex with the RAD51 protein, which is essential for DNA repair through homologous recombination (Davies et al, 2001). However, the direct function of BRCA1 in DSB repair is less clear, although a more proximal role in sensing and regulation of cellular response to DNA damage has been suggested by several recent papers (Boulton, 2006). More importantly, BRCA1 upregulates the expression of genes involved in antioxidant response, including GST genes (Bae et al, 2004). In accordance, BRCA1 deficiency conferred sensitivity to several oxidising agents in cell lines (Bae et al, 2004). The lack of effect in BRCA1 carriers could be related to the already high oxidative stress in cells deficient in the BRCA1 protein; the addition of low active GSTP1 does not significantly add to the process of tumorigenesis. However in BRCA2 carriers, low level of active GSTP1 results in higher DNA damage properly sensed by BRCA1, but ineffectively corrected by the BRCA2 complex.

Several modifier genes were reported in carriers of BRCA1/2 mutation. A modifying effect has been confirmed by two or more separate studies for two of these modifiers. Interestingly, in both genes, the effect differed among BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. A rare polymorphism in the RAD51 gene was associated with BC risk in BRCA2 carriers (Levy-Lahad et al, 2001; Wang et al, 2001; Kadouri et al, 2004a). Recently, a large study among approximately 8500 mutation carriers confirmed a modifying effect for the homozygous, but not the heterozygous, RAD51 135 g/c polymorphism (Antoniou et al, 2007). On the other hand, a polymorphic CAG-repeat length in the AIB1, a coactivator of the oestrogen receptor, was found to modify BC risk in BRCA1 carriers (Rebbeck et al, 2001; Kadouri et al, 2004b). Two recent, large studies did not observe a modifying effect for the AIB1-CAG repeat among BRCA1/2 carriers (Hughes et al, 2005; Spurdle et al, 2006). It is possible that these larger studies included heterogeneous population both genetically and clinically; therefore, association may be either lost or exaggerated. Indeed, distributions of three polymorphisms previously reported by us, the AR-CAG repeat (Kadouri et al, 2001), RAD51-g/c-SNP (Kadouri et al, 2004a) and the AIB1-polyglutamine chain length (Kadouri et al, 2004b), as well as the GSTP1 in the current study, were significantly different among Ashkenazi Jews as compared with British Caucasian women. Since we included two distinct populations, we were able to effectively adjust for origin.

In conclusion, in the present study we report a modifying effect of the GSTP1 gene in BRCA2 but not BRCA1 carriers. Carriers of homozygous Val/Val allele, a less active variant of the GSTP1 protein, had an approximately threefold risk for BC and younger age at onset as compared with Ile/Ile carriers. This adds to the mounting evidence suggesting differences in molecular mechanisms involved in normal function and tumor formation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. These positive results obtained from a small population of BRCA2 carriers should prompt a larger study in other populations as well.

Acknowledgments

LK was supported by Barclay fellowship through the British Council, for which we are most grateful. We thank the Radlett Synagogue Community for its tremendous support for this study. ZKJ was supported by a legacy from the late Marion Silcock. This work was supported by the Institue of Cancer Research, UK.

References

- Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyjord JE, Hopper JL, Loman N, Olsson H, Johannsson O, Borg A, Pasini B, Radice P, Manoukian S, Eccles DM, Tang N, Olah E, Anton-Culver H, Warner E, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Tulinius H, Thorlacius S, Eerola H, Nevanlinna H, Syrjakoski K, Kallioniemi OP, Thompson D, Evans C, Peto J, Lallo F, Evans DG, Easton DF (2003) Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 72: 1117–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou AC, Sinilnikova OM, Simard J, Leone M, Dumont M, Neuhausen SL, Struewing JP, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Barjhoux L, Hughes DJ, Coupier I, Belotti M, Lasset C, Bonadona V, Bibnon Y, (GEMO), Rebbeck TR, Wagner T, Lynch HT, Domchek SM, Nathanson KL, Garber JE, Weitzel J, Narod SA, Tomlinson G, Olopade OL, Godwin A, Isaacs C, Jakubowska A, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Byrski T, Huzarski T, Peock S, Cook M, Baynes C, Murray A, Rogers M, Daly PA, Dorkins H, (EMBRACE), Schmutzler RK, Versmold B, Engel C, Meindl A, Arnold N, Niederacher D, Deissler H, (GCHBOC), Spurdle AB, Chen X, Waddell N, Cloonan N, (kConFab), Kirchhoff T, Offit K, Freidman E, Kaufmann B, Laitman Y, Galore G, Rennert G, Leibkowicz F, Raskin L, Andrulis IL, Ilyushik E, Ozcelik H, Devilee P, Vreeswijk MPG, Greene MH, Prindiville SA, Osorio A, Benitez J, Zikan M, Szabo CI, Kilpovaara O, Nevanlinna H, Hamann U, Durocher F, Arason A, Couch FJ, Easton DF, Chenevix-Trench G, (CIMBA) (2007) RAD52 135G-C modifies breast cancer risk among BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from a combined analysis of 19 studies. Am J Hum Genet 81: 1186–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai T, Miyoshi Y, Kim SJ, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S (2006) Association of GSTP1 CpG islands hypermethylation with poor prognosis in human breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat 200: 169–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae I, Fan S, Meng Q, Rih JK, Kim HJ, Kang HJ, Xu J, Goldberg ID, Jaiswal AK, Rosen EM (2004) BRCA1 induces antioxidant gene expression and resistance to oxidative stress. Cancer Res 64: 7893–7909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton SJ (2006) Cellular functions of the BRCA tumor suppressor proteins. Biochem Soc Trans 34: 633–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri E, Frenkel K, Liehr JG, Rogan E, Roy D (2000) Estrogens as endogenous genotoxic agents: DNA adducts and mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 27: 75–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AA, Masson JY, McIlwraith MJ, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Venkitaraman AR, West SC (2001) Role of BRCA2 in control of the RAD51 recombination and DNA repair protein. Mol Cell 7: 273–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawling S, Hachey DL, Roodi N, Parl FF (2004) In vitro model of mammary estrogen metabolism: structural and kinetic differences between catechol estrogen 2- and 4-hydroxyestradiol. Chem Res Toxicol 17: 1258–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning AM, Healey CS, Pharoah PD, Teare MD, Ponder BA, Easton DF (1999) A systematic review of genetic polymorphisms and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8: 843–854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan KM, Cai Q, Shu XO, Jin F, Zhu TL, Dai O, Gao YT, Zheng W (2004) Genetic polymorphisms in GSTM1, GSTP1 and GSTT1 and the risk of breast cancer: Shanghai Breast Cancer Study and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton MR, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, Bishop DT, Weber B, Lenoir G, Chang-Claude J, Sobol H, Teare MD, Struewing J, Arason A, Scherneck S, Peto J, Rebbeck TR, Tonin P, Neuhausen S, Barkardottir R, Eyfjord J, Lynch H, Ponder BA, Gayther SA, Zelada-Hedman M, the Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (1998) Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet 62: 676–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester LM, Hayes JD, Millis R, Barnes D, Harris AL, Schlager JJ, Powis G, Wolf CR (1990) Expression of glutathione s-transferase and cytochrome P450 in normal and tumor breast tissue. Carcinogenesis 11: 2163–2170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode EL, Dunning AM, Kuschel B, Healey CS, Day NE, Ponder BA, Easton DF, Pharoah DP (2002) Effect of germ-line genetic variation on breast cancer survival in a population-based study. Cancer Res 62: 3052–3057 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JD, Pulford DJ (1995) The glutathione S-transferase supergene family: regulation of GST and the contribution of isoenzymes to cancer chemoprotection and drug resistance. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 30: 445–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DJ, Ginolhac SM, Coupier I, Barjhoux L, Gaborieau U, Bressac-de-Paillerets B, Chompret A, Bignon YJ, Uhrhammer N, Lasset C, Giraud S, Sobol H, Hardouin A, Berthet P, Peyrat JP, Fournier J, Nogues C, Lidereau R, Muller D, Fricker JP, Longy M, Toulas C, Guimbaud R, Yannoukakos D, Mazoyer S, Lynch HT, Lenoir GM, Goldgar DE, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Sinilnikova OM (2005) Breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and polyglutamine repeat length in the AIB1 gene. Int J Cancer 117(2): 230–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadouri L, Easton DF, Edwards S, Hubert A, Kote-Jarai Z, Glaser B, Durocher F, Abeliovich D, Peretz T, Eeles R (2001) CAG and GGC repeat polymorphism in the androgen receptor gene and breast cancer susceptibility in BRCA1/2 carriers and non-carriers. Br J Cancer 85: 36–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadouri L, Kote-Jarai Z, Easton EF, Hubert A, Hamoudi R, Glaser B, Abeliovich D, Peretz T, Eeles RA (2004b) Polyglutamine repeat length in the AIB1 gene modifies breast cancer susceptibility in BRCA1 carriers. Int J Cancer 108: 399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadouri L, Kote-Jarai Z, Hubert A, Durocher F, Abeliovich D, Glaser B, Hamburger T, Eeles RA, Peretz T (2004a) A single nucleotide polymorphism in the RAD51 gene modifies breast cancer risk in BRCA2 but not in BRCA1 carriers or non-carriers. Br J Cancer 90: 2002–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley MK, Engqvist-Goldstein A, Montali JA, Whealey JB, Schmidt Jr DE, Kauvar LM (1994) Variability of glutathione S-transferase isoenzyme patterns in matched normal and cancer human breast tissue. Biochem J 3: 843–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Lahad E, Lahad A, Eisenberg S, Dagan E, Paperna T, Kasinetz L, Catane R, Kaufman B, Beller U, Renbaum P, Gershoni-Baruch R (2001) A single nucleotide polymorphism in the RAD51 gene modifies cancer risk in BRCA2 but not BRCA1 carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 3232–3236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemble S, Schroeder KR, Spenser SR, Meyer DJ, Hallier E, Bolt HM, Ketterer B, Taylor JB (1994) Human glutathione S-transferase o (GSTT1): cDNA cloning and characterization of a genetic polymorphism. Biochem J 300: 271–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbeck TR (1997) Molecular epidemiology of the human glutathione S-transferase genotypes GSTM1 and GSTT1 in cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 733–743 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbeck TR, Kantoff PW, Kirthivas K, Neuhausen S, Blackwood MA, Godwin AK, Daly MB, Narod SA, Garber JE, Lynch HT, Weber BL, Brown M (1999) Modification of BRCA1-associated breast cancer risk by the polymorphic androgen-receptor CAG repeat. Am J Hum Genet 64: 1371–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbeck TR, Wang Y, Kantoff PW, Krithivas K, Neuhausen SL, Godwin AK, Daly MB, Narod SA, Brunet JS, Vesprini D, Gaeber JE, Lynch HT, Weber BL, Brown M (2001) Modification of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast cancer risk by AIB1 genotype and reproductive history. Cancer Res 61(14): 5420–5424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidegard J, DePierre JW, Pero RW (1985) Hereditary interindividual differences in the glutathione transferase activity towards trans-stilbene oxide in resting human mononuclear leukocytes are due to a particular isozyme(s). Carcinogenesis 6: 1211–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurdle AB, Antoniou AC, Kelemen L, Holland H, Peock S, Cook MR, Smith PL, Greene MH, Simard J, Plourde M, Southey MC, Godwin AK, Beck J, Miron A, Daly MB, Santella RM, Hopper JL, John EM, Andrulis IL, Durocher F, Struewing JP, Easton DF, Chenvix-Trench G, Australian Breast Cancer Family Study, Australian Jewish Breast Cancer Study, Breast Cancer Family Registry, Interdisciplinary Health Research, International Team on Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer and Epidemiological Study of Familial Breast Cancer (2006) The AIB1 polyglutamine repeat does not modify breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15(1): 76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholdes S, Baker SM, Berlin M, McAdams M, Timmerman MM, Brody LC, Tucker MA (1997) The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med 336: 1401–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorlacius S, Struewing JP, Hartge P, Olafsdottir GH, Sigvaldason H, Tryggvadottir L, Wacholder S, Tulinius H, Eyfjord JE (1998) Population-based study of risk of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA2 mutations. Lancet 352: 1337–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl FD, Taioli E, Maugard C, Zheng W, Ribeiro Pinto LF, Ambrosone C, Parl FF, Nedelcheva-Kristensen V, Rebbeck TR, Brennan P, Boffetta P (2004) Glutathione S-transferase M1, T1, and P1 and breast cancer: a pooled analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 1473–1479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WW, Spurdle AB, Kolachana P, Bove B, Modan B, Ebbers SM, Suthers G, Tucker MA, Kaufman DJ, Doody MM, Tarone RE, Daly M, Levavi H, Pierce H, Chetrit A, Yechezkel GH, Chenevix-Trench G, Offit K, Godwin AK, Struewing JP (2001) A single nucleotide polymorphism in the 5′ untranslated region of RAD51 risk of cancer among BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 10: 955–960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Shu X, Ruan Z, Cai Q, Jin F, Gao Y, Zheng W (2005) Genetic polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferases genes (GSTM1, GSTT1 GSTP1) and survival after chemotherapy for invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer 103: 52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimniak P, Nanduri B, Pikula S, Bandorowicz-Pikula J, Singhal SS, Srivastava SK, Awasthi S, Awasthi YC (1994) Naturally occurring human glutathione S-transferase GSTP1 isoforms with isoleucine and valine in position 105 differ in enzymic properties. Eur J Biochem 224: 893–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]