Abstract

As C. elegans hermaphrodites age, sperm become depleted, ovulation arrests, and oocytes accumulate in the gonad arm. Large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) foci form in these arrested oocytes that contain RNA-binding proteins and translationally masked maternal mRNAs. Within 65 minutes of mating, the RNP foci dissociate and fertilization proceeds. The majority of arrested oocytes with foci result in viable embryos upon fertilization, suggesting that foci are not deleterious to oocyte function. We have determined that foci formation is not strictly a function of aging, and the somatic, ceh-18, branch of the major sperm protein pathway regulates the formation and dissociation of oocyte foci. Our hypothesis for the function of oocyte RNP foci is similar to the RNA-related functions of processing bodies (P bodies) and stress granules; here, we show three orthologs of P body proteins, DCP-2, CAR-1 and CGH-1, and two markers of stress granules, poly (A) binding protein (PABP) and TIA-1, appear to be present in the oocyte RNP foci. Our results are the first in vivo demonstration linking components of P bodies and stress granules in the germ line of a metazoan. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that formation of oocyte RNP foci is inducible in non-arrested oocytes by heat shock, osmotic stress, or anoxia, similar to the induction of stress granules in mammalian cells and P bodies in yeast. These data suggest commonalities between oocytes undergoing delayed fertilization and cells that are stressed environmentally, as to how they modulate mRNAs and regulate translation.

Keywords: oocyte, processing body, stress granule, RNP, C. elegans, ovulation, fertility, heat shock, osmotic stress, anoxia, major sperm protein

Introduction

Sexual reproduction requires the joining of two products of meiosis, sperm and oocytes. While each of these gametes is haploid, meiosis is regulated differently in the two cell types. Sperm are generally produced by uninterrupted meiotic divisions of spermatids, whereas in humans and most animals, oocytes arrest in prophase I of meiosis for extended lengths of time (Masui and Clarke, 1979). The developmental arrest of oocytes varies from days in Drosophila, to years in Xenopus, and decades in humans. Proper regulation of oocyte maturation, whether over days or decades, is critical; for example, miscarriage and congenital birth defects in humans can result from nondisjunction during meiosis I (Hassold and Hunt, 2001). Defects in both the nucleus and cytoplasm of old-aged eggs have been attributed as causes of fertility problems, though specific, defective mechanisms have not yet been identified (Sherins et al., 1995).

In hermaphroditic nematodes such as C. elegans, oocytes are fertilized in an assembly-line fashion every 23 minutes (McCarter et al., 1999). At first glance, these oocytes do not appear to model the meiotic arrest observed in most animals; however, as hermaphrodites age, the fixed number of sperm eventually becomes depleted and ovulation essentially arrests (McCarter et al., 1999). Thus, although rates of meiotic maturation are high in young animals where sperm are present, rates of maturation decrease drastically in older animals lacking sperm. In old-aged worms, sex-determination mutants that do not generate sperm (so-called “females”, such as fog-2), and related nematodes that exist as male/female species, oocytes can arrest in meiotic prophase for several days. If a sperm-depleted, old-aged hermaphrodite or a female encounters a male, is mated, and obtains a new supply of sperm, meiotic maturation resumes and viable offspring are produced upon fertilization (McCarter et al., 1999).

Several recent studies have begun to elucidate the pathways by which sperm stimulate meiotic maturation in C. elegans. Major sperm protein (MSP) was identified as a secreted signal in sperm that is sufficient to stimulate oocyte maturation, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation, and sheath cell contractions (Miller et al., 2001). While MSP was first identified decades ago as an actin analog that allows sperm motility, more recent studies show that it is also transported from the sperm cytoplasm into the proximal gonad by a membrane-budding mechanism (Klass and Hirsh, 1981; Ward and Klass, 1982; Bottino et al., 2002; Kosinski et al., 2005). MSP signals oocyte meiotic maturation and MAPK activation by antagonizing both the VAB-1 Eph receptor protein tyrosine kinase on oocyte membranes and a sheath cell-dependent pathway involving the POU-homeodomain protein, CEH-18 (Miller et al., 2003). One current model suggests that when MSP is present and binds VAB-1, an inositol triphosphate receptor, ITR-1, is activated, relieving the negative regulation of MAPK activation and oocyte maturation (Corrigan et al., 2005). MSP and VAB-1 also regulate an N-methyl D-aspartate type glutamate receptor, NMR-1. In the presence of sperm, NMR-1 activates a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII), UNC-43, that acts in oocytes to promote oocyte maturation and MAPK activation (Corrigan et al., 2005). Intriguingly, the current data support a model whereby NMR-1 negatively regulates oocyte maturation when sperm are absent. A detailed understanding of the mechanisms by which VAB-1 and NMR-1 pathways regulate oocyte maturation in the absence of MSP awaits further investigation.

Important roles for the CEH-18 pathway, that is parallel to VAB-1 in sensing MSP to regulate oocyte maturation, have also been uncovered. CEH-18 is required for the formation of sheath/oocyte gap junctions (Rose et al., 1997), and two innexins, INX-14 and INX-22, have been identified as functionally essential components of these gap junctions (Whitten and Miller, 2007). Antagonistic Gαo/i and Gαs signaling pathways have been identified that function in the soma to regulate meiotic maturation and sheath/oocyte gap junction communication (Govindan et al., 2006). The CEH-18 pathway also controls rearrangement of the microtubule cytoskeleton in response to the presence of MSP. Increased enrichment of microtubules in cortical locations of oocytes occurs in wild-type animals as a function of time and depletion of sperm; when 4 day-old, sperm-depleted animals are mated, the microtubule organization in oocytes essentially reverses from cortically-enriched to the even, cytoplasmic distribution seen in young hermaphrodites (Harris et al., 2006). The significance of cortical microtubule enrichment in oocytes when sperm are absent is not fully understood; however, since microtubules play critical roles during oogenesis in regulating protein trafficking, cell polarity, and RNA localization, the dramatic changes in their localization are believed to have functional importance for the worm.

In addition to dramatic changes in the cytoskeleton of oocytes when sperm are absent, large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) foci form in oocytes of sperm-depleted worms. Oocyte RNP foci have been observed in old-aged hermaphrodites, fem-1(hc17) females, and unmated C. remanei females (Schisa et al., 2001; Jud et al., 2007; Fig. 1). These foci are cortically localized, reminiscent of the microtubule localization in unmated fog-2(q71) females (Harris, et al., 2006). Several protein components of C. elegans germ granules (P granules) are localized to the large foci, including PGL-1 and GLH-1,-2 (Kawasaki et al., 1998; Gruidl et al., 1996; Schisa et al., 2001). P granules are RNPs localized uniquely to germ cells and germ cell precursors in C. elegans. They localize throughout the cytoplasm of maturing oocytes and early embryo germ cell precursors, and during the remainder of development, they associate with the nuclear envelope (Strome and Wood, 1982; Pitt et al., 2000). In addition to P granule components, RNA-binding proteins that are normally distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm, including MEX-3 and MEX-1, also associate to the large RNP foci in arrested oocytes (Schisa et al., 2001). Several maternal mRNAs that are translationally repressed in oocytes also localize to the RNP foci, including pos-1, skn-1, par-3, and nos-2. Not all mRNAs are highly enriched in the large RNP foci as probes for tubulin and actin mRNA show low or no hybridization to the foci (Schisa et al., 2001). In addition to increased levels of select mRNAs in oocyte foci, high levels of RNA also accumulate in nuclear-associated P granules of pachytene germ cells, and in the gonad central core of old-aged animals with arrested ovulation (Schisa et al., 2001; Fig. 1). We have hypothesized that arrested oocytes that are not fertilized promptly require additional mechanisms to maintain the quality of maternal mRNAs; specifically, RNA-binding proteins within RNP foci may function to modify maternal mRNAs to maintain RNA stability or prevent precocious translation (Jud et al., 2007).

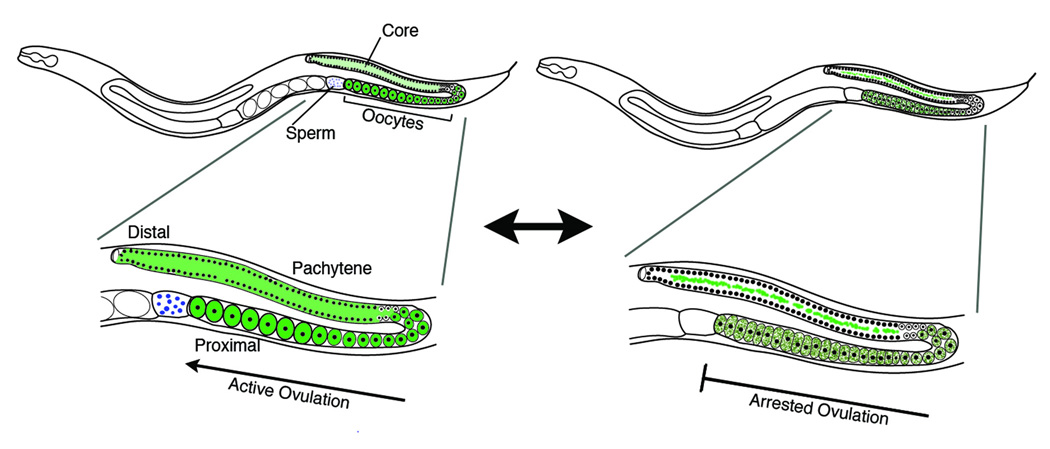

Figure 1.

Schematic showing distribution of RNA (green) in animals on left with active ovulation when sperm are present (blue), contrasted to animals on right with arrested ovulation when sperm are absent. Note distinct RNP foci in gonad core and accumulated oocytes when ovulation is arrested.

Two RNPs with roles in post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression have recently been characterized in several eukaryotic cell types, notably processing bodies (P bodies) in yeast and mammalian cells, and stress granules in mammalian cells (Sheth and Parker, 2003; Kedersha et al., 1999; Kedersha et al., 2005). P bodies were originally described as RNA granules containing RNA decay factors (Bashrikov et al., 1997); they form in all eukaryotic cells with a role in normal RNA metabolism in resting cells. P bodies are dynamic and reversible in their size and number, with increasing numbers observed in yeast cells exposed to osmotic stress, UV stress, or increased cell density (Teixeira, et al., 2005; Brengues et al., 2005). The components of P bodies include mRNA, decapping enzymes (DCP1, DCP2, Dhh1 (RCK/p54), Lsm1–7), and proteins that control deadenylation (Ccr4, Not1–4) and translation (Pat1, Dhh1, CPEB, eIF4E) (reviewed in Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). Recent data provide evidence that two of the four human orthologs of C. elegans MEX-3 localize to processing bodies in human cell lines (Buchet-Poyau et al., 2007). Interestingly, three orthologs of P body proteins in C. elegans (DCP-2, CGH-1/RCK, and CAR-1/RAP55) localize to P body-like foci in somatic cells and germ cells, as well as to P granules (Lall et al., 2005; Navarro et al., 2001; Boag et al., 2005; Audhya et al., 2005). Commensurate with their function, P bodies lack ribosomal subunits and most translation initiation factors, whereas the related RNPs, stress granules, contain small ribosomal subunits and early translation initiation factors (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006).

Stress granules were first identified in the cytoplasm of tomato cells subjected to heat shock as RNPs containing non-translating mRNAs (Nover et al., 1983; Nover et al., 1989). Stress granules can be rapidly induced (15–30 minutes) in mammalian cell culture after exposure to environmental stresses including heat, oxidative stress, osmotic stress, UV irradiation, and hypoxia (Collier and Schlesinger, 1986; Collier et al., 1988; Kedersha et al., 1999; Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). Some of the components of stress granules are also observed in processing bodies, including proteins that function in mRNA decay, initiation of translation, and translational control. Unique components of stress granules in mammalian cells appear to include the stalled 48S preinitiation complexes, poly A binding protein (PABP), and TIA-1/R (Kedersha et al., 2005). Stress granules also differ from P bodies as they can be heterogeneous in shape, while P bodies are more uniformly spheroid foci. Stress granules and P bodies both increase in size and number in response to stress (Kedersha et al., 2005; Teixera et al., 2005; Wilczynska et al., 2005). Interestingly from an evolutionary standpoint, stress granules have not been detected in S. cerevisiae. They have largely been characterized in cell culture systems; however, a limited number of whole animal studies have also documented their formation in response to stress (Mangiardi et al., 2004; Moeller et al., 2004).

Previously, we have reported the formation of large RNP foci in arrested C. elegans oocytes (Schisa et al., 2001; Jud et al., 2007). In this paper, we establish that RNP foci are not toxic to oocyte viability and that at least small oocyte foci form in multiple classes of mutants with defects in ovulation. Our data are consistent with the model that MSP, the sperm signal sufficient to promote ovulation, negatively regulates the formation of RNP foci in oocytes and is sufficient to promote at least partial dissociation of RNP foci. We have examined mutations in the pathway downstream of MSP to determine that the somatic branch of the pathway that regulates oocyte maturation also controls foci formation. Lastly, our results reveal multiple connections among RNPs in arrested oocytes, P bodies, and stress granules. These three RNPs share multiple components and are inducible by multiple environmental stresses.

Methods

Plasmids and Strains

N2 (Bristol variety) is the wild-type strain. Worm cultures were maintained on NGM plates at 15°C, 20°C, or 25°C (Brenner, 1974). The following mutant strains were used: BS5182 [emo-1(oz1) sma-1(e30) V/nT1[unc-?(n754) let-?] (IV;V)], EE67 [him-8(e1489) IV; mup-2(e2346) X], CB4108 [fog-2(q71], DG1604 [fog-2(q71) V; ceh-18(mg57) X], DG1612 [vab-1(dx31)/mIn1[dpy-10(e128) mIs14] II; fog-2(q71) V], PS2582 [itr-1(sy290) unc-24(e138) IV], TX183 [oma-1(zu405te33)/nT1[unc-?(n754) let-?]IV; oma-2(te51)/nT1 V], XM1007 [fog-3(q443) I/hT2[bli-4(e937) let-?(q782) qIs48](I;III); unc-43(n498) IV], KG524 [gsa-1(ce94) I], KG532 [kin-2 (ce179) X], DG1856 [goa-1(sa734) I], BA1 [fer-1(hc1) I]. All strains listed can be obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, http://www.cbs.umn.edu/CGC/.

Construction and integration of gfp:mex-3 fusion

Standard techniques were used to manipulate and amplify DNA. A pie-1 promoter::gfp::mex-3 transgene, pJS114, was created by modification of a previously described pie-1::gfp expression vector (Amiri et al., 2001). The mex-3 coding sequence was PCR amplified from full-length mex-3 cDNA using primers with SpeI adapters at the 5' ends. (Complete primer sequences are available upon request). The mex-3 PCR product was cloned downstream of gfp into the SpeI site of the pie-1 promoter::gfp plasmid. Sequencing was performed to confirm that the mex-3 insert was in the correct orientation and in-frame with the gfp sequence. A unique NotI site was created in the plasmid by mutagenesis of one of two NotI sites. The unc-119(+) genomic fragment was inserted into this NotI site (Maduro and Pilgrim, 1995).

LAP::PAB-1 and LAP::TIA-1

Gateway cloning (Invitrogen) was used to generate both constructs (Landy, 1989). The entire pab-1 ORF was amplified from N2 genomic DNA, and the tia-1 (Y46G5A.13) coding sequence was amplified from cDNA. Both products were recombined into pDONR201. The resulting constructs were recombined into pKC1.01 to generate N-terminal LAP-tagged fusion proteins (Cheesman et al., 2004) expressed under the control of the pie-1 promoter and 3’ UTR. The LAP tag includes GFP and can be used for localization and affinity purification (LAP) of target proteins. The tag is recognized by anti-GFP antibodies, and in figures, we refer to expression as GFP. LAP-tagged lines were generated by the microparticle bombardment method (Praitis et al., 2001).

Viability analysis

To determine the viability of arrested oocytes, two different strains were used: fog-2(q71) and GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71). In either case, the number of accumulated oocytes in the gonad arm was determined using DIC optics; in the case of the second strain, GFP foci were verified in the accumulated oocytes. Matings were set with individual fog-2(q71) females and either wild-type or fog-2(q71) males. In the fog-2 strain, while females lack sperm completely, males are fertile (Schedl and Kimble, 1988). The time needed for the accumulated oocytes to be fertilized and laid was determined empirically, by checking the plates frequently and counting the total number of unfertilized oocytes, embryos, and larvae on the plate. When that number was equal to the number of oocytes accumulated prior to mating, adults were removed from the plates so no additional embryos or oocytes could be laid. Viability of embryos was scored 24 hours later, by counting numbers of hatched larvae vs. unhatched embryos.

Fluorescence microscopy

For SYTO 14 staining to visualize RNA, methods were as previously published (Jud et al., 2007). Antibodies, antisera, and staining protocols were as described: anti-MEX-3 (Draper et al., 1996) (antibody from Dr. James Priess); anti-MAPK-YT (Sigma) (Page et al., 2001), anti-DCP-2 and anti-DCPS (Lall et al., 2005) (antibodies from Dr. Richard Davis), anti-CAR-1 (Boag et al., 2005) (antibodies from Dr. Peter Boag and Dr. Keith Blackwell), anti-PGL-1 (Kawasaki et al., 1998) (antibody from Dr. Susan Strome), anti-CGH-1 C (fixation as for anti-CAR-1 or as for DCP-2; antibodies from Dr. David Greenstein), and anti-GFP (Chemicon). Secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes. In specified experiments, hermaphrodites were purged (ie. depleted) of sperm prior to analysis. Once sperm were depleted, ovulation arrested and the uterus was confirmed to be empty of embyros; this was confirmed using DIC optics at 400x magnification.

GFP expression in GFP::MEX-3, LAP::PAB-1, and LAP::TIA-1 worms was detected in live worms, in controls and after various stresses, mounted in 100mM levamisole on a 3% agarose pad. Images of GFP::MEX-3 and LAP::PAB-1 oocytes were collected using an Olympus Fluoview 300 laser scanning confocal microscope. Images of GFP::MEX-3 in oocytes after osmotic stress and LAP::TIA-1 were collected using an Olympus BX51 compound microscope equipped with epifluorescence.

MSP injection

Recombinant His-tagged MSP, purified in E. coli, was received as a generous gift from Dr. David Greenstein (Miller et al., 2001), and injected into fog-2(q71) and GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) animals using a Nikon inverted diaphot-TMD microscope. MSP was injected at 200 nM into the vulva or the syncytial gonad core. As a negative control, animals were injected with PBS. Injected animals were examined using DIC microscopy post-injection for sheath cell contractions; this confirmed a successful injection. As an additional control, injected animals were stained with anti-MAPK YT antibodies to confirm that MAPK was activated in the proximal oocytes of injected animals (data not shown). Animals in which sheath cell contractions were observed were examined either using direct fluorescence in the GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) animals or fixed and stained using anti-MEX-3 antibodies.

Heat shock, osmotic stress, and anoxia analyses

GFP::MEX-3 worms were subjected to heat shock by placing worms on NGM plates at 34°C for 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9 hours; foci of GFP in oocytes was monitored over time. After the initial time course to determine when foci form, a 3-hour heat shock was used in subsequent experiments. In some experiments, N2 worms were fixed after heat shock and anti-MEX-3 antibodies were used to detect foci. To determine when the foci dissociate after recovery from heat shock, GFP::MEX-3 animals were initially subjected to heat shock for 3 hours, and a time course was performed, examining the GFP distribution at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 minutes post-heat shock. The timeline for recovery was also repeated using anti-MEX-3 antibodies on fixed N2 animals.

In initial osmotic shock experiments, GFP::MEX-3 worms were soaked in various concentrations of NaCl for various amounts of time to determine if any conditions resulted in GFP foci formation. Using 400x magnification, no obvious GFP foci were detected in any worms; however, at 600x magnification, treatment of one hour in 500 mM NaCl resulted in detection of GFP foci in approximately 50% of soaked worms. The recovery timeline was performed using those conditions for the initial salt stress.

The oxygen deprivation (anoxia) experiments were performed as previously described (Padilla et al., 2002). Briefly, young adult animals, approximately 12–24 hours after the L4 to adulthood molt, were placed in an anaerobic biobag chamber (20°C) and exposed to anoxia for 4 or 20 hours. Animals were removed from the anoxic environment, placed on a 3% agarose pad, and immediately visualized using either a spinning disc confocal microscope or a Zeiss Fluorescent Axioscope. Post-anoxia analysis was conducted after 2 hours of recovery in air.

Results

To confirm that formation of RNP foci in oocytes is not deleterious to their ability to eventually give rise to viable embryos, we used two different strains to assay viability of embryos arising from oocytes that had accumulated in the proximal gonad and contained RNP foci. On average, twenty oocytes were present in a single gonad arm prior to mating. Greater than 90% of these oocytes with large RNPs gave rise to viable embryos after being fertilized (n = 122 oocytes; 403 oocytes; see Methods); thus, we conclude that the presence of RNP foci in oocytes is not deleterious to their viability or future embryonic viability.

Dynamic formation and dissociation of RNP foci in oocytes

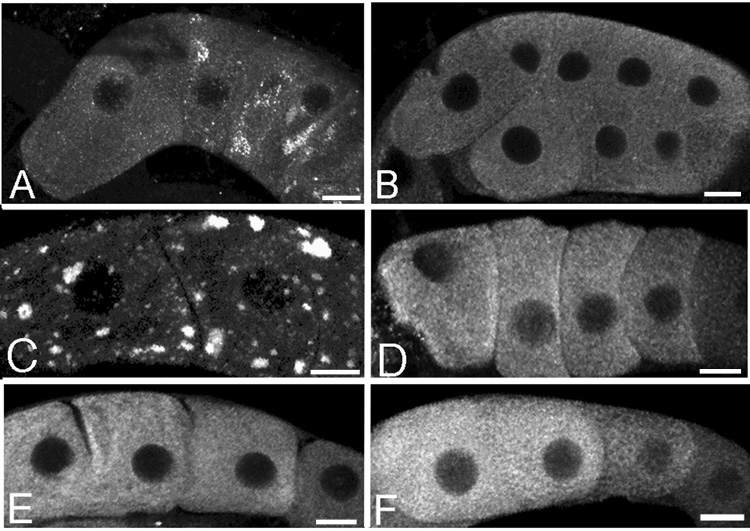

A vital dye that preferentially stains RNA (SYTO 14) was previously used to show that the overall distribution of RNA in old, wild-type worms changes relative to young worms. Specifically, in old, wild-type animals purged of sperm, increased levels of RNA are observed in the nuclear-associated P granules of immature germ cells, in foci in the syncytial gonad core, and in cytoplasmic foci in oocytes (Schisa et al., 2001; Jud et al., 2007). We sought to determine whether similar changes occur in fog-2(q71) worms; these worms are considered females as they never make sperm and ovulation arrests at a young age (Schedl and Kimble, 1988). High levels of RNA were observed in foci near the nuclear envelope (Fig. 2C), and concentrated into large, cytoplasmic foci in the gonad core and oocytes of unmated fog-2(q71) females (n = 40) (Figs. 2C, D).

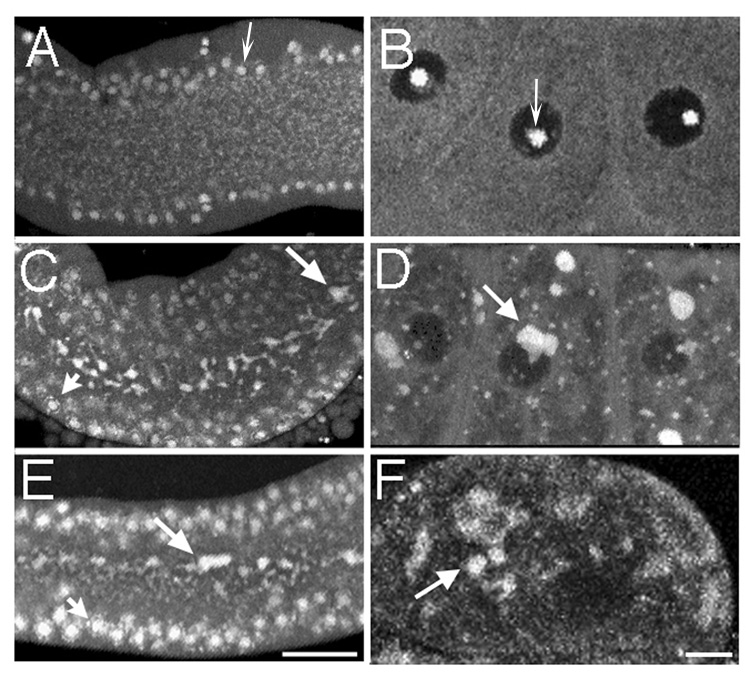

Figure 2.

RNA foci form in the gonad core and oocytes in response to an absence of sperm or heat shock. (A–F) Fluorescence micrographs of the gonad core (on left) and oocytes (on right) stained with SYTO 14 (white) to visualize RNA. (A,B) RNA is distributed evenly throughout the core and oocyte cytoplasm of young wild-type animals. Concave arrows indicate examples of strongest staining in presumptive nucleoli of immature germ cells surrounding the core of the germline and of oocytes. In this, and all images, the proximal oocytes are oriented to the left. (C,D) RNA is concentrated into discrete foci in the core and oocytes of young, fog-2(q71) animals (long arrows). RNA also accumulates at the location of nuclear-associated P granules (short arrow). (E,F) RNA is visible in foci in the core and oocytes of young, wild-type animals after 3 hours of heat shock (long arrows). RNA also accumulates at the location of nuclear-associated P granules (short arrow). Scale bar corresponds to 85 µm in panel E, and 7 µm in panel F.

In order to better characterize the RNP foci, a GFP::MEX-3 translational reporter was generated; MEX-3 is one of several putative RNA-binding proteins localized in the RNP foci (Schisa et al., 2001). The GFP::MEX-3 strain is non-rescuing (R. Ciosk, Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, unpublished observation); however, the GFP expression mimics the expression pattern observed with the anti-MEX-3 antibody in the distal germline, oocytes and embryos (data not shown; Draper et al., 1996). The GFP::MEX-3 strain was used to visualize the distribution of MEX-3 in proximal oocytes of hermaphrodites over time; GFP accumulation changed from evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of oocytes, to concentrated in discrete foci at 89–91 hours after the fourth larval stage at 23°C (referred to as post-L4) (n = 28) (data not shown). The redistribution of GFP::MEX-3 coincided with the time when adult hermaphrodites become depleted of sperm. The distribution of MEX-3 was next examined in the fog-2(q71) female strain where sperm are never produced. In young fog-2(q71) females, small foci of MEX-3 formed in the most proximal oocytes in 80% of animals at 8 hours post-L4 at 23°C (n = 14); however, MEX-3 remained diffusely cytoplasmic in the more distal oocytes in these young females (Fig. 3B). At 12 hours post-L4 at 23°C, foci were present in nearly all of the arrested oocytes in all animals (n = 21) (data not shown), and at 24 hours post-L4 at 23°C, the foci were approximately 0.5–1 µm (n = 29) (Fig. 3C). The largest foci were generally observed in the most proximal oocytes. The foci were often enriched at the cell cortex and in some cases, at the nuclear envelope. Individual confocal slices of top focal planes and mid-focal planes of the same oocytes demonstrated this localization pattern (Figs. 3F, G). The foci dramatically increased in size as the amount of time an oocyte was arrested increased. At 3 days post-L4 at 23°C, the foci in fog-2(q71) oocytes were as large as 10 µm (n = 34) (Fig. 3E).

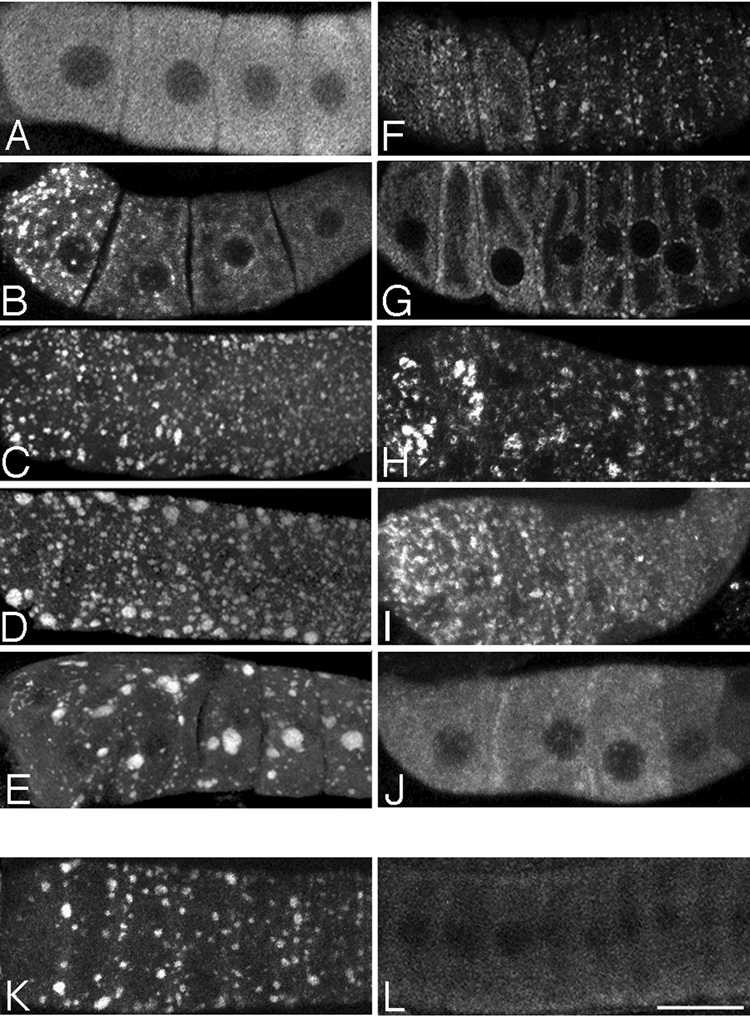

Figure 3.

MEX-3 localizes to dynamic cytoplasmic foci in oocytes in response to an absence of sperm or heat shock. (A–J) Fluorescence micrographs of oocytes immunostained for the MEX-3 protein. (A) MEX-3 is distributed evenly throughout the oocyte cytoplasm in young wild-type animals. (B) MEX-3 foci form within 8 hours post-L4 in fog-2(q71) animals. (C–E) The foci increase in size as a function of time; note the progressively larger foci at time points 24, 48, and 72 hours post L4. (F,G) Foci localize cortically and to the nuclear envelope of oocytes in an old, sperm-depleted hermaphrodite in 1 µm, top focal plane and mid-focal plane confocal slices. (H) MEX-3 foci increase in size after heat shock of fog-2(q71) animals 1 day post-L4; compare to panel C. (I) MEX-3 foci decrease somewhat in size after recovery of heat shock fog-2(q71) animals. (J) MEX-3 foci in heat shock, fog-2(q71) animals dissociate after recovery and mating, and MEX-3 is detected throughout the cytoplasm. (K,L) GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) worms express GFP foci pre-mating (K), and dissociation of foci occurs within 65 minutes of mating (L). Scale bar for A–L corresponds to 15 µm.

We previously observed that the formation of large RNP foci in oocytes was reversible within six hours of mating (Schisa et al., 2001). To better characterize how quickly foci dissociate after animals with arrested ovulation are replenished with sperm, either GFP::MEX-3 hermaphrodites purged of sperm (n = 12) or GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) females (n = 20) with GFP foci in oocytes, were isolated and the distribution of GFP was again assessed at multiple times post-mating. The GFP foci appeared identical to the MEX-3 foci observed by antibody staining (compare Fig. 3D to Fig. 3K), and they dissociated approximately 65 minutes after males mated with either the purged hermaphrodites or females (Fig. 3L; data not shown). The RNA that appears concentrated into large foci in oocytes and the gonad core of fog-2(q71) animals also appeared to dissociate within 65 minutes of mating into a fog-2(q71) female (data not shown). The fact that RNP formation is reversible and dynamic suggests the RNPs may function to maintain oocytes when fertilization is delayed and that their formation is tightly regulated.

Sperm negatively regulate the formation of RNP foci

The formation of large cytoplasmic RNP foci in oocytes was previously observed in old-aged hermaphrodites and in a temperature-sensitive, female strain, fem-1(hc17), that makes no sperm at high temperatures and has arrested ovulation (Schisa et al., 2001). To determine if it is the absence of sperm or arrested ovulation that activates the formation of RNP foci, several mutants with defects in sperm or ovulation were examined. In contrast to fog-2(q71) females that make no sperm, fer-1(hc1) animals make nonfunctional, non-motile sperm that are fertilization defective (Ward and Miwa, 1978). In fer-1(hc1) animals at the restrictive temperature, concomitant with the first several ovulations, sperm increasingly are swept from the spermatheca into the uterus and do not return to the spermatheca (Ward and Miwa, 1978). No MEX-3 foci were detected in oocytes of fer-1(hc1) animals at 45 hours post-hatching at 25°C, a time when sperm are present in the spermatheca (n = 31) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In fer-1(hc1) hermaphrodites at 88 hours post-hatching at 25°C, over 150 oocytes have been ovulated and, on average, only 13 sperm remain in the spermatheca (Ward and Miwa, 1978). When we examined fer-1(hc1) hermaphrodites at 112 hours post-hatching at 25°C, large MEX-3 foci were visible in oocytes (n = 63) (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1B). These results suggest that even fertilization-defective sperm are capable of signaling to oocytes to negatively regulate the formation of RNP foci. However, when these sperm become depleted, as in old-aged wild type and presumably at 112 hours post-hatching in fer-1(hc1), MEX-3 foci form.

Table 1.

Correlations among presence of sperm, MAPK activation, microtubule cortical enrichment, and MEX-3 foci in oocytes

| Strain | Sperm present | MAPK activation | MEX-3 foci | Microtubule cortical enrichment* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Wild type, depleted of sperm | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| fog-2(q71) | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| fer-1(hc1) | Yes/No | ND | No/Yes | ND |

| mup-2(e2346) | Yes | ND | Not large | ND |

| emo-1(oz1) | Yes | Yes1 | Not large | ND |

| oma-1(zu405te33);oma-2(te51) | Yes | No2 | No | Yes |

| itr-1(sy290gf) unc-24(e138) | Yes | Less than wt3 | No | ND |

| unc-43(n498); fog-3(q443) | No | More than fog-23 | Yes | ND |

| ceh-18((mg57);fog-2(q71) | No | No1 | No | No |

| vab-1(dx31):fog-2(q71) | No | No1 | Yes | Yes |

| gsa-1(ce94gf), purged | No | Yes2 | No | No |

| kin-2(ce179), purged | No | Yes2 | No | No |

| goa-1(sa734), purged | No | Yes2 | No | No |

Corrigan et al., 2006

ND not determined

To determine if defective or absent sperm are essential as a cue to activate or prevent repression of foci formation, two strains defective in ovulation were examined: emo-1(oz1) is ovulation-defective, and mup-2(e2346) lacks sheath cell contractions (Iwasaki et al., 1996; Myers et al., 1996). In each of these strains, sperm are present and unaffected. The distribution of MEX-3 in the oocytes of these strains was variable, ranging from no foci, to small or intermediate-sized foci (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1C; data not shown). No foci were observed as large as those in the proximal oocytes of fog-2(q71) females (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that small RNP foci can form in the presence of normal sperm, although they do not in wild type, and that arrested or decreased rates of ovulation may be sufficient to promote the formation of at least small foci.

In addition to being correlated with arrested ovulation and an absence of sperm, the formation of RNP foci also appeared to be correlated with an absence of activated MAPK. In young, wild-type hermaphrodites with no large oocyte RNP foci, sperm are present, ovulation is active, and MAPK is activated in the most proximal 1–3 oocytes (Page et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2001; Figs. 4A, B; Table 1). In females where sperm are absent, ovulation arrests, and MAPK is not activated in the proximal oocytes, foci are present (Page et al., 2001; Miller et al., 2001; Figs. 4C, D; Table 1). To try to distinguish whether sperm, activated MAPK, or both negatively regulate foci formation, we analyzed the distribution of MEX-3 in mutants where MAPK activity was uncoupled from the presence of sperm. In oma-1(zu405te33); oma-2(te51) and itr-1(sy290gf) unc-24(e138) mutants, sperm are present, but the frequency of MAPK activation is significantly reduced, and ovulation is arrested or decreased two-fold, respectively (Figs. 4F, H; Detwiler et al., 2001; Corrigan et al., 2005). Large foci of MEX-3 were not detected in the most proximal oocytes of either of these strains (n = 49, 74) (Figs. 4E, G; Table 1). Interestingly, MEX-3 foci were observed in more distal germ cells of oma-1(zu405te33); oma-2(te51) (n = 15) (data not shown). In contrast, in unc-43(n498gf); fog-3(q443) females, sperm are not present, and MAPK activation frequency is elevated compared to fog-2(q71) (Fig. 4J, compare to Fig. 4D; Corrigan et al., 2005; Govindan et al., 2006). In these animals, large foci of MEX-3 were observed in the proximal oocytes (n = 22) (Fig. 4I; Table 1). Taken together, these results suggest that while MAPK activity is often correlated with the presence of sperm and the absence of foci, the presence or absence of sperm can regulate the formation of RNP foci in oocytes, independent of MAPK activation.

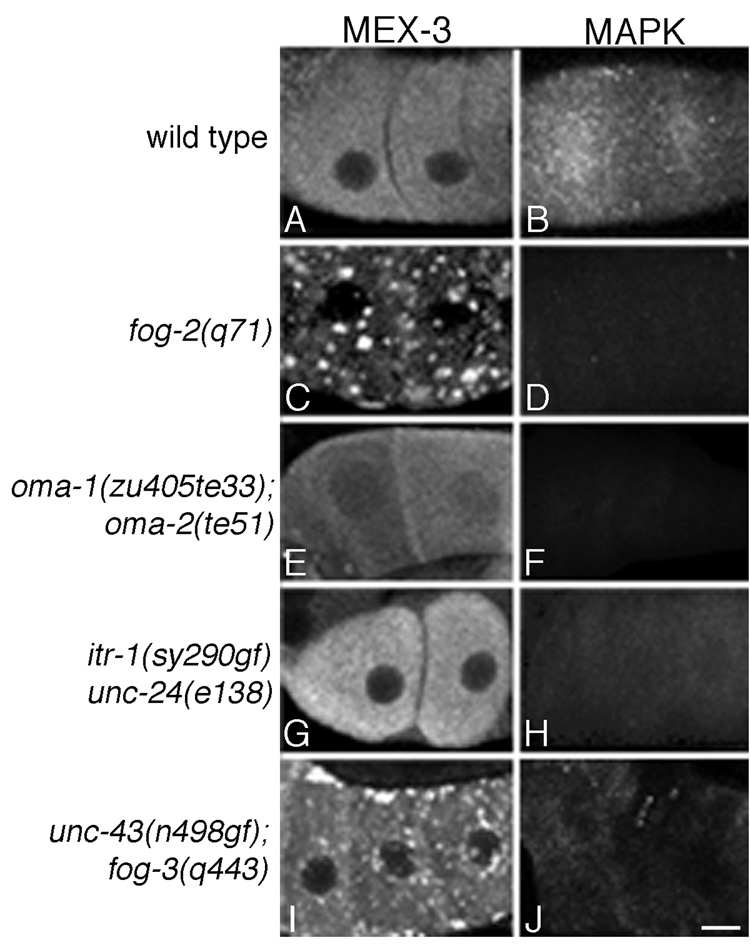

Figure 4.

MEX-3 foci are negatively regulated by sperm, independent of MPK-1 MAPK activation. (A, C, E, G, I) Fluorescence micrographs of wild-type and mutant oocytes immunostained for the MEX-3 protein. (B, D, F, H, J) MAPK-YT staining of wild-type and mutant oocytes. (A–D) In wild type and fog-2(q71) females, MAPK activation is inversely correlated with MEX-3 foci formation. (E–H) In oma-1(zu405te33); oma-2(te51) and itr-1(sy290gf) unc-24(e138) hermaphrodites, the frequency of activated MAPK is reduced relative to wild type; yet, no MEX-3 foci are detected in proximal oocytes. (I–J) In unc-43(n498gf); fog-3(q443) females, the frequency of activated MAPK is elevated relative to fog-2(q71); however, MEX-3 foci form. All MAPK activation patterns have previously been reported elsewhere (Detwiler et al., 2001; Corrigan et al., 2005; Govindan et al., 2006). Scale bar corresponds to 7 µm.

Major sperm protein is sufficient for dissociation of RNP foci

Major sperm protein (MSP) is a signal in sperm sufficient to promote meiotic maturation, ovulation, sheath contractions, and MAPK activation (Miller et al., 2001). Since mating triggers the dissociation of RNP foci in oocytes within 65 minutes (Fig. 3L), we asked if MSP is sufficient to promote dissociation of foci. MSP was injected into the vulva of GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) females that had arrested oocytes with large GFP foci or fog-2(q71) females. The distribution of GFP or MEX-3 at 60–90 minutes post-injection suggested that many of the foci in the most proximal oocytes had dissociated (data not shown; Fig. 5A). As an alternative method of introducing MSP protein into the gonad, we also injected MSP into the gonad syncytial core; these injections resulted in a more robust dissociation of MEX-3 foci in all of the accumulated oocytes, including distal oocytes (Fig. 5B). In contrast, after injection of MSP into the uterus, the foci persisted in the more distal oocytes, even at later time points post-injection (data not shown), suggesting that the MSP signal may not have reached the distal cells. To confirm the MSP signaling pathway regulates the RNP foci in oocytes, we examined downstream effectors in the MSP pathway, initially focusing on vab-1 and ceh-18 (Miller et al., 2003). VAB-1 functions as an Ephrin receptor protein tyrosine-kinase for MSP on oocyte membranes (Miller et al., 2003). CEH-18 localizes to sheath cell nuclei and controls sheath cell function, in part, by regulating sheath/oocyte gap junctions (Rose et al., 1997; Govindan et al., 2006). CEH-18 also regulates rearrangement of the microtubule cytoskeleton in response to the presence of MSP (Harris et al., 2006). In oocytes of vab-1(dx31); fog-2(q71) females, large MEX-3 foci were observed (n = 30) (Fig. 5C). In contrast, in ceh-18(mg57); fog-2(q71) females, no MEX-3 foci were detected (n = 50) (Fig. 5D). We interpret the failure of foci to form in the ceh-18(mg57); fog-2(q71) females as consistent with the idea that CEH-18 is required for foci formation in the absence of MSP signaling.

Figure 5.

MSP and MSP signaling genes regulate MEX-3 foci formation in oocytes. (A–F) Fluorescence confocal micrographs of mutant oocytes immunostained for the MEX-3 protein. (A–B) Confocal images of fog-2(q71) females after microinjection of MSP protein, via either the vulva (A), or the syncytial gonad core (B) show MSP promotes the dissociation of MEX-3 foci. (C) Confocal image of vab-1(dx31); fog-2(q71) oocytes shows no inhibition of MEX-3 foci formation in unmated females. (D–F) Confocal images of unmated ceh-18(mg57); fog-2(q71) females, purged gsa-1(ce81gf), and purged kin-2(ce179rf) hermaphrodites show an absence of MEX-3 foci, even in the absence of sperm. Hermaphrodites were purged by allowing sufficient time for all sperm to become depleted and ovulation to arrest (see Methods). Scale bars correspond to 7 µm.

We next asked whether proteins in the Gαo/i and Gαs signaling pathways affect formation of RNP foci in oocytes. The antagonistic Gαo/i and Gαs protein signaling pathways function in the soma, like ceh-18, to negatively regulate meiotic maturation and MAPK activation (Govindan et al., 2006). We predicted that since goa-1, a heteromeric Gαo/i protein subunit, and kin-2, a protein kinase A regulatory subunit, negatively regulate meiotic maturation and MAPK activation in the absence of sperm, RNP foci would not form in oocytes in goa-1(sa734) or kin-2(ce179rf) animals lacking sperm. In contrast, gsa-1, a heteromeric Gαs protein subunit, promotes meiotic maturation; therefore, we predicted gain-of-function gsa-1 mutations would be similar to goa-1 loss-of-function mutations. In gsa-1(ce81gf) animals lacking sperm, no MEX-3 foci were observed (n = 44) (Fig. 5E). Similarly, in kin-2(ce179rf) and goa-1(sa734) animals lacking sperm, MEX-3 appeared uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of the proximal oocytes (n = 14, 23) (Fig. 5F; data not shown). Interestingly, small foci of MEX-3 were detected in more distal oocytes of purged kin-2(ce179rf) animals (data not shown). Overall, we conclude that the somatic, antagonistic G protein signaling pathways are important in regulating the formation of RNP foci in oocytes.

Oocyte RNP foci contain orthologs of processing body proteins

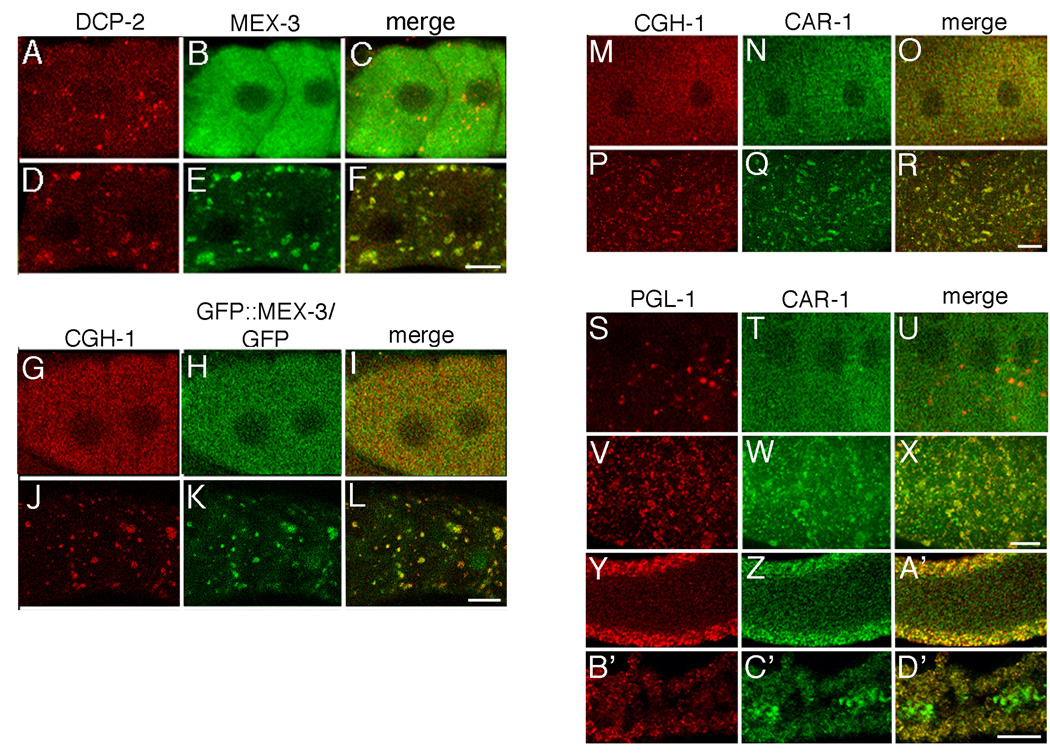

Our hypothesis for the function of RNP foci in oocytes is they control RNA stability or translational repression of maternal mRNAs when fertilization is delayed. This proposed role is quite similar to the roles of somatic cell RNPs that regulate mRNA turnover and translational repression in yeast and mammalian cells, called processing bodies (P bodies) (Sheth and Parker, 2003). One group of conserved proteins localized to P bodies is a subset of decapping enzymes and enhancers of decapping enzymes, including Dcp1p, Dcp2p, DcpSp, and Dhh1p in yeast (Parker and Sheth, 2007). Two C. elegans orthologs of these proteins, DCP-2 and the ortholog of Dhh-1, CGH-1, localize to P body-like, cytoplasmic foci in somatic and germline precursor blastomeres in C. elegans embryos. DCP-2 and CGH-1 also associate with P granules in immature germ cells and oocytes (Navarro et al., 2001; Lall et al., 2005). We first examined the localization of DCP-2 in wild-type animals and, as previously described, detected low levels of punctate, perinuclear staining in pachytene-stage germ cells and diffuse, cytoplasmic staining with small foci in maturing, wild-type oocytes (n = 124) (Fig. 6A; data not shown; Lall et al., 2005). In arrested oocytes of fog-2(q71) animals, in contrast, large cytoplasmic foci of DCP-2 were observed that co-localized with MEX-3 (n = 152) (Figs. 6D–F). Substructure within the foci was evident, and distinct DCP-2 and MEX-3 foci were also present (Fig. 6F). The expression of DCPS, which localizes throughout the cytoplasm of embryos but not in cytoplasmic bodies (Lall et al., 2005) was also examined; DCPS did not localize to the large MEX-3 foci in fog-2(q71) oocytes nor to any detectable foci (n = 18) (data not shown). We next examined the co-localization of MEX-3 with CGH-1, using the GFP::MEX-3 strain. In wild-type animals, CGH-1 was generally cytoplasmic throughout the proximal oocytes with a few small cytoplasmic foci detected (n = 32) (Fig. 6G). In arrested oocytes, the distribution of CGH-1 changed into larger, cortically-localized foci that partially co-localized with the GFP foci in the GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) strain (n = 33) (Fig. 6J–L).

Figure 6.

Processing body proteins localize to oocyte RNP foci in the absence of sperm. (A–C, G–I, M–O, and S–U) Single confocal images of wild-type or GFP::MEX-3 oocytes. (D–F, J–L, P–R, and V–X) Single confocal images of fog-2(q71) or GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) oocytes. (A–C) In the presence of sperm, DCP-2, is perinuclear and in small cytoplasmic foci (A), whereas MEX-3 is diffusely cytoplasmic (B). (D–F) In the absence of sperm, large cytoplasmic foci form containing DCP-2 (D) and MEX-3 (E). (C, F) Merged images of DCP-2 and the oocyte RNP foci marker, MEX-3. (G–I) In wild-type oocytes, CGH-1 is diffusely cytoplasmic and in small foci, while MEX-3, as visualized using a GFP antibody in the GFP::MEX-3 strain, is diffusely cytoplasmic. (J–L) In arrested oocytes of the GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) strain, CGH-1 is concentrated into large foci that partially co-localize with GFP foci. (M–R) CGH-1 and CAR-1 co-localize in wild-type and fog-2(q71) oocytes. (P–R) Increased numbers and size of CGH-1 and CAR-1 foci are evident in fog-2(q71) oocytes. (S–X) PGL-1 and CAR-1 localize in small and large foci of wild-type and fog-2(q71) worms. (S,V) The P granule marker, PGL-1, becomes concentrated into larger foci in fog-2(q71) oocytes. (T,W) The number and size of oocyte foci containing the P body protein, CAR-1, also increases. (U,X) Merged images of PGL-1 and CAR-1 show more co-localization in arrested oocytes than wild-type oocytes. (Y–D’) PGL-1 and CAR-1 in the gonad core of wild-type and fog-2(q71) animals. (Y-A’) PGL-1 (red) and CAR-1 (green) co-localize to P granules of germ nuclei. PGL-1 is detectable in a small number of faint foci in the core, and CAR-1 is detectable in small foci throughout the cytoplasmic core. (B’–D’) CAR-1, but not PGL-1, becomes concentrated in larger discrete foci in the core of fog-2(q71) animals. Scale bar corresponds to 7 µm in panels F, L, R, X and 85 µm in panel D’.

Since CGH-1 genetically and physically interacts with CAR-1, the C. elegans ortholog of yeast Scd6p (Rap55 in mammalian cells), CAR-1 was examined next (Boag et al., 2005; Audhya et al., 2005). Members of the Scd6 family of proteins are components of P bodies and contain two Sm-like domains that are predicted to bind RNA (reviewed in Decker and Parker, 2006). CAR-1 co-localizes with P granules in the germline, is concentrated in additional, small cytoplasmic foci in the gonad core, and localizes to foci in both somatic and germline embryonic blastomeres (Boag et al., 2005; Audhya et al., 2005). The distribution of CAR-1 changed from being mostly cytoplasmic and localized in a few small, cytoplasmic foci in wild-type oocytes (n = 42) (Fig. 6N) to large, cortically-localized, CGH-1-containing foci in arrested oocytes (n = 54) (Figs. 6P–R). To examine the distribution of CAR-1 with a previously published marker of the RNP foci, CAR-1 was also examined in a co-staining experiment with PGL-1 (Schisa et al., 2001). In wild-type oocytes CAR-1 was distributed throughout the cytoplasm and in small foci that occasionally co-localized with PGL-1 foci (n = 74) (Fig. 6S–U). In arrested oocytes, increased numbers of cytoplasmic CAR-1 foci were detected that partially co-localized with larger PGL-1 foci (n = 110). Distinct CAR-1 foci that lacked PGL-1 were also detected (Fig. 6V–X). Dramatic changes were observed in the gonad core, with much larger foci of CAR-1 concentrated unevenly throughout the core of fog-2(q71) animals (n = 110) (Figs. 6B’–D’). Taken together, we conclude that the components of RNP foci in arrested oocytes include orthologs of several proteins in yeast and mammalian cell P bodies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Components observed in cytoplasmic foci of oocytes

| P body components | Stress granule components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress | PGL-1 | RNA | MEX-3 | DCP-2 | CGH-1 | CAR-1 | PAB-1 | TIA-1 |

| Arrested ovulation | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Heat shock | − | + | + | + | + | ND | + | + |

| Osmotic shock | ND | − | + | ND | ND | ND | − | − (nuclear) |

| Anoxia | ND | ND | + | − | ND | ND | + | + |

Oocyte foci contain orthologs of stress granule proteins and are induced by environmental stresses

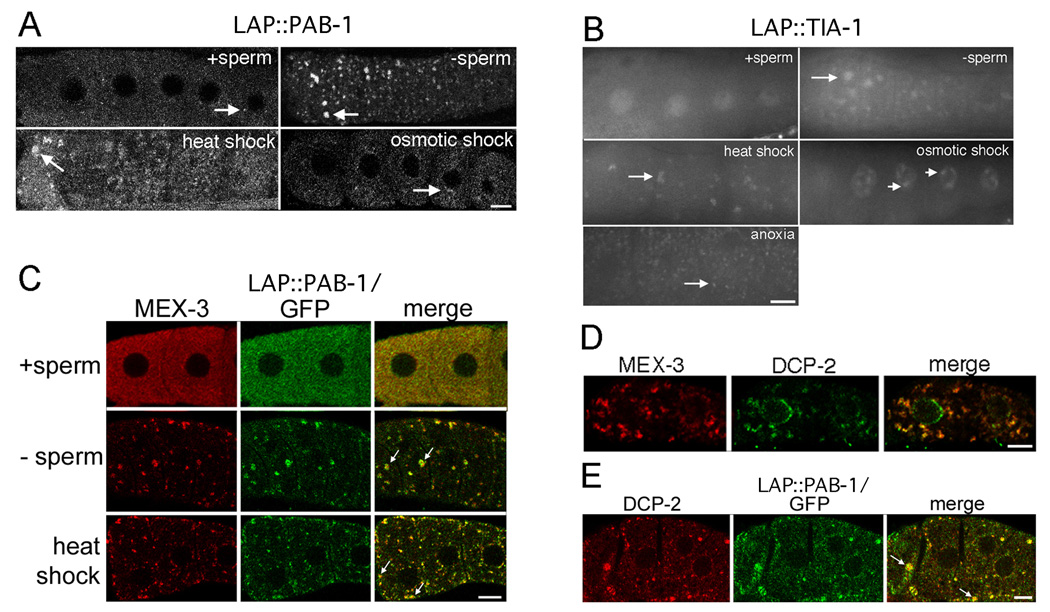

The RNP foci in arrested oocytes appeared to have similarities with P bodies as noted above; however, they also seemed to share characteristics with stress granules, RNPs that form in response to environmental stresses such as heat shock, oxidative stress, and osmotic stress (Collier and Schlesinger, 1986; Collier et al., 1988; Kedersha et al., 1999). In order to help determine whether oocyte RNP foci function more like P bodies or stress granules, we set out to determine the distribution of poly (A) binding protein in young and old, sperm-depleted, wild-type oocytes. Poly (A) binding protein is considered to be a general marker for stress granules (Kedersha et al., 2005). We constructed a LAP::PAB-1 strain to examine the localization of C. elegans poly (A) binding protein (PAB-1). The distribution of LAP::PAB-1 was generally even throughout the cytoplasm of wild-type oocytes; slightly higher accumulation of protein was observed in small foci near the nuclear envelope of some cells, consistent with the location of nuclear-associated P granules (n = 41) (Fig. 7A). When LAP::PAB-1 worms were depleted of sperm, larger oocyte foci were observed; the largest foci were observed in the most proximal oocytes and localized cortically (n = 40) (Fig. 7A). To determine if the large foci of PAB-1 co-localized with MEX-3, co-staining for GFP and MEX-3 was performed in LAP::PAB-1 worms depleted of sperm; many foci showing co-localization of PAB-1 with MEX-3 were observed. Some of the foci of PAB-1 appeared to be within larger foci of MEX-3; in many cases, the foci of MEX-3 and PAB-1 appeared to be adjacent or docked onto one another, similar to that described by Kedersha et al., for the proximity of P bodies to stress granules (n = 107) (Fig. 7C; Supplementary Figs. 2D, E) (Kedersha et al., 2005). By increasing the magnification four-fold, distinct substructure within the foci was obvious (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Since the RNP foci in arrested oocytes appeared to include one marker of stress granules, we next analyzed the localization of TIA-1, another protein considered to be a marker for stress granules (Kedersha et al., 1999). TIA-1 is preferentially localized to the nucleus of most cells (Fig. 7B); however, it also shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm (Kedersha et al., 1999). Similar to the localization of LAP::PAB-1 in old, wild-type oocytes depleted of sperm, LAP::TIA-1 protein was concentrated in cytoplasmic foci (n = 36) (Fig. 7B), and it co-localized with MEX-3 (data not shown; n = 45).

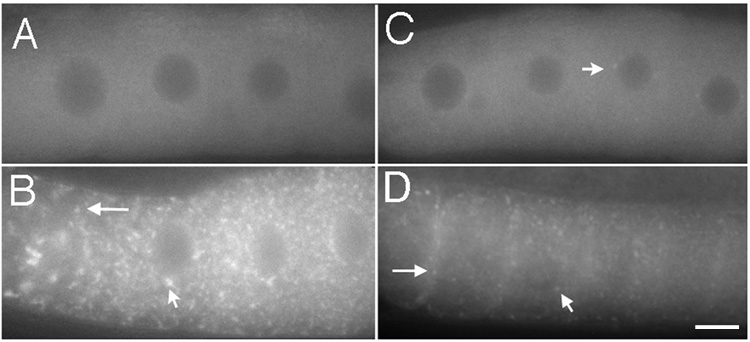

Figure 7.

Oocyte RNP foci include stress granule proteins and are induced by environmental stresses. (A) Confocal images showing expression of LAP::PAB-1 in proximal oocytes of live animals. Note lack of large foci when sperm are present, large foci when sperm are absent or after heat shock, and only small, rare foci after osmotic shock. Arrows indicate largest foci in each image. (B) Fluorescence micrographs showing expression of LAP::TIA-1 in proximal oocytes of live animals. Note mainly nuclear expression when sperm are present, large cytoplasmic foci when sperm are absent or after heat shock or anoxia, and nuclear foci after osmotic shock. Long arrows indicate cytoplasmic foci, and short arrows indicate nuclear foci. (C) Single confocal slices of fixed LAP::PAB-1 animal stained for MEX-3 and GFP. GFP foci incompletely co-localize with MEX-3 foci when sperm are absent or after heat shock. Docking of GFP foci with MEX-3 foci is apparent in several instances (arrows). (D) Single confocal slice of wild-type animal after heat shock, co-stained for MEX-3 and DCP-2, shows incomplete co-localization of a P body protein and MEX-3 in heat shock-induced foci. (E) Single confocal slice of fixed LAP::PAB-1 purged worms stained for DCP-2 and GFP. P body proteins and stress granule proteins appear to incompletely co-localize and dock adjacent to one another in arrested oocytes (arrows). Scale bars correspond to 7 µm.

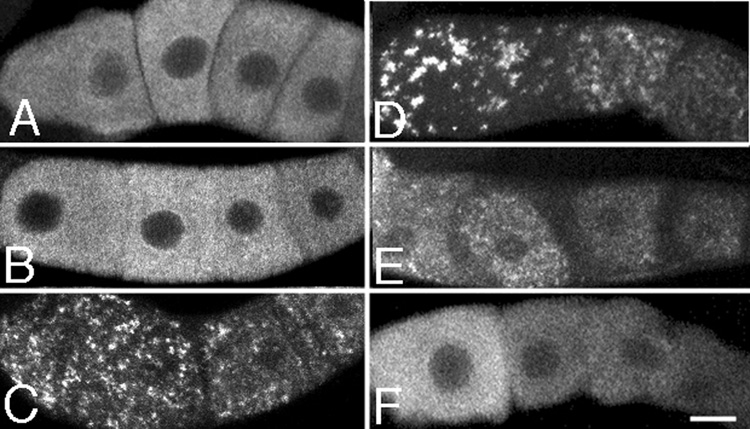

Because orthologs of P body and stress granule proteins localized to large foci in arrested C. elegans oocytes, and P bodies and stress granules increase in size and number in response to heat stress (Nover et al., 1983; Nover et al., 1989; Kedersha et al., 2005), we tested whether heat shock could induce the formation of MEX-3 foci in non-arrested oocytes. After one hour at 34°C, no obvious oocyte foci had formed (n = 30) (Figs. 8A, B). After 2 and 3 hours at 34°C, small foci of MEX-3 were visible (n = 30) (Fig. 8C; data not shown). After five hours of heat shock, the foci in the most proximal oocytes had increased in size in nearly all of the worms (n = 28) (Fig. 8D); however, after 7 hours of heat shock, the foci had decreased in size in some of the animals (n = 25) (data not shown), and after 9 hours of heat shock, nearly all of the worms had died (n = 25). The formation of the heat shock-induced MEX-3 foci was reversible. After 20 and 40 minutes of recovery post-heat shock, the MEX-3 foci remained large (data not shown; n = 18). However, after 60 minutes many of the foci had disappeared or decreased in size (n = 22) (Fig. 8E). The foci continued to decrease in size and number, such that at 90 minutes of recovery, nearly all of the foci had disappeared (n = 16) (Fig. 8F).

Figure 8.

MEX-3 localizes to dynamic cytoplasmic foci in oocytes in response to heat shock. (A–F) Confocal images of oocytes in control and heat-shocked worms, immunostained for the MEX-3 protein. (A–B) MEX-3 is distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm of control animals (A) and animals heat-shocked for one hour (B). (C–D) MEX-3 becomes concentrated into discrete foci after 2 hours of heat shock (C); the foci increase in size as a function of time until 5 hours of heat shock when they reach maximal size (D). (E–F) MEX-3 foci decrease in size and number after 60 (E) and 90 minutes of recovery (F), post-heat shock. Scale bar corresponds to 7 µm.

To distinguish whether heat shock and arrested ovulation promote the formation of foci additively, we heat shocked 1- and 3-day post-L4, fog-2(q71) animals. In each case, the average size of the MEX-3 foci was greater in the heat shocked animal (6.1 µm and 8.8 µm, for 1- and 3-days post-L4 respectively) compared to the same stage fog-2(q71) animal (0.8 µm and 6.8 µm) (compare Fig. 3H to Fig. 3C; data not shown). We next compared MEX-3 foci in fog-2(q71) and wild-type animals that had been heat-shocked for 3 hours and then allowed to recover for 90 minutes. In contrast to nearly undetectable foci after 90 minutes recovery post-heat shock in wild-type animals (Fig. 8F), we found that the foci in fog-2(q71) animals appeared to decrease in size to some extent after recovery from heat shock but were still easily detectable in 95% of the animals (n = 32) (Fig. 3I, compare to 3H and 3C). After mating the fog-2(q71) animals during the recovery period, MEX-3 was detected at increased levels in the cytoplasm in 87% of animals, and fewer RNP foci were observed (n = 30) (Fig. 3J). In the remaining 13% of animals, some of which may not have been successfully mated, foci were still predominant. Therefore, it appears sperm are required to dissociate most of the material in the extra large MEX-3 foci of fog-2(q71) animals after heat shock.

To determine if the stress of heat-shock induces all of the changes in the germline observed when ovulation is arrested, we analyzed the distribution of RNA and other RNA-binding proteins. After 3 hours of heat shock, the distribution of RNA, as detected by SYTO 14 staining, appeared similar to that observed when ovulation is arrested. Large RNA foci were present in the gonad central core and oocytes, and RNA was present at high levels on nuclear-associated P granules in pachytene-stage germ cells (n = 285) (compare Figs. 2E, F to Figs. 2C, D). The stress granule markers, LAP::PAB-1 and LAP::TIA-1, also formed foci in oocytes in greater than 75% of animals after heat shock (n = 70, 66) (Figs. 7A, B). Some of the foci were large, similar to the size of GFP::MEX-3 foci (compare to Fig. 8C); however, most were smaller and only visible at high magnification. To confirm that the stress granule protein foci induced by heat shock co-localized with the MEX-3 foci observed after heat shock (Figs. 8C and D), LAP::PAB-1 and LAP::TIA-1 animals were co-stained with MEX-3 and GFP after heat shock; incomplete co-localization of the two proteins was observed in both cases (n = 76, 53) (Fig. 7C; data not shown). In several oocytes, it appeared as if the MEX-3 foci were docked onto the LAP::PAB-1 or LAP::TIA-1 foci. Finally, we asked if P body proteins also localized into foci after heat shock and found that DCP-2 co-localized with MEX-3 in large oocyte foci in 49% of animals (Fig. 7D) (n = 43). DCP-2 was also detected in discrete foci in the gonad core after heat shock, but not in animals with arrested ovulation (data not shown; n = 162, 181). Like DCP-2, CGH-1 was observed in large foci in oocytes and in the core after heat shock (n = 50); however, CGH-1 was also present in large foci in the gonad core of animals with arrested ovulation (n = 33) (data not shown). In contrast, the P granule protein PGL-1 appeared to be largely cytoplasmic and absent from large foci in oocytes after heat shock (data not shown; n = 335). Taken together, we conclude that heat shock induces formation of RNP foci in non-arrested oocytes that are similar to those induced by arrested ovulation; the foci components include: MEX-3, PAB-1, TIA-1, DCP-2, CGH-1 and RNA (Table 2).

To determine if heat shock is the only environmental stress that can induce the formation of RNP foci, we next asked whether osmotic stress could induce the formation of large RNP foci in C. elegans oocytes. Osmotic stress induces an increase in the number and size of P bodies in yeast and induces the formation of stress granules in cell culture (Teixeira et al., 2005; Kedersha et al., 1999). Cytoplasmic GFP::MEX-3 foci formed in oocytes of worms that were treated with 500 mM NaCl; after 60 minutes in high salt, nearly 50% of worms had oocytes with MEX-3 foci (n = 17) (Fig. 9B). Smaller, less obvious foci were detected in an additional 20% of animals. The induction of the GFP::MEX-3 foci was reversible as they disappeared in 70% of worms within 90 minutes of recovery, after the original osmotic stress (n = 16) (Fig. 9C). We stained worms after a 60-minute osmotic shock with the RNA dye, SYTO14, and did not detect accumulation of RNA in foci in the central core, on nuclear-associated P granules, or in oocyte foci (data not shown; n = 76). Similarly, no large foci of LAP::PAB-1 or LAP::TIA-1 were observed in the oocyte cytoplasm after osmotic shock (n = 23) (Figs. 7A, B). Small LAP::PAB-1 foci in the cytoplasm that appeared to be nuclear-associated were detected; however, GFP appeared only slightly enriched in these foci, compared to controls (n = 22) (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, although no cytoplasmic foci of LAP::TIA-1 were observed after osmotic shock, discrete foci within nuclei were detected in over 50% of worms (n = 23) (Fig. 7B). When we asked if the localization of P body proteins changed after osmotic shock, we found that the distributions of DCP-2 and CGH-1 did not appear to change (data not shown) (n = 124, 26). Overall, it appears that while osmotic stress induces the formation of cytoplasmic foci of MEX-3 in approximately half of treated animals, neither stress granule nor P body proteins are induced to localize to cytoplasmic foci (Table 2).

Figure 9.

GFP::MEX-3 expressing gonads show foci formation after osmotic shock and anoxia. (A) GFP::MEX-3 is cytoplasmic in control, wild-type oocytes. (B) GFP foci appear after 1 hour of osmotic shock; in all panels, short arrows indicate nuclear-associated foci and long arrows indicate cortical foci. (C) GFP foci dissociate within 60 minutes of recovery after osmotic shock; however, nuclear-associated foci perdure (short arrow). (D) Cortical and nuclear-associated GFP foci form after 20 hours of anoxia. Scale bar corresponds to 7 µm.

The final environmental stress we examined was anoxia since oxygen deprivation induces the formation of stress granules in mammalian cells (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). In animals subjected to 4 and 20 hours of anoxia, over 90% of the animals formed small cytoplasmic foci of GFP::MEX-3 (n = 11, 22) (Fig. 9D; data not shown). To determine if the foci induced by oxygen deprivation were more similar to those induced by heat shock or osmotic stress, we next determined if the anoxia-induced foci included P body proteins or stress granule proteins. Worms were co-stained after 20 hours of anoxia with DCP-2 and MEX-3; however, no large foci containing DCP-2 and MEX-3 were detected (data not shown; Table 2). In contrast, when LAP::TIA-1 worms were subjected to anoxia, the GFP signal was detected in cytoplasmic foci that were slightly smaller than the foci seen after heat shock or in the absence of sperm (Fig. 7B). Taken together, these data suggest that formation of foci in arrested oocytes may play a similar role as P bodies and/or stress granules that increase in size or form in response to multiple environmental stresses.

Discussion

Formation of large P body-like RNP foci in arrested oocytes

In most metazoans, oocytes arrest in meiosis for variable periods of time prior to fertilization. In humans, problems with fertility are associated with extended periods of meiotic arrest or increased age of oocytes (Navot et al., 1991; Schramm et al., 2002). Yet many women successfully conceive and deliver babies using oocytes that have been arrested for decades, thus suggesting mechanisms exist to maintain the viability of these special cells that may break down as a function of time. In C. elegans, dramatic changes in the localization of RNPs in oocytes occur when sperm are absent and ovulation arrests. Several translationally repressed mRNAs, P granule proteins, and RNA-binding proteins needed in early embryogenesis are concentrated in large cytoplasmic foci in arrested oocytes of old, wild-type worms depleted of sperm (Schisa et al., 2001; Jud et al., 2007). In this paper, we show that similar RNP foci also form in young female animals, and they contain orthologs of P body proteins and stress granule components.

Numerous examples of cells with specialized subcellular zones for aspects of RNA biogenesis and function have been documented. Cajal bodies and nuclear speckles have roles in RNA processing and splicing in the nucleus, while stress granules and P bodies have roles in RNA decay and regulation of translation initiation in the cytoplasm (reviewed in Handwerger and Gall, 2006; Parker and Sheth, 2007). Specialized RNA granules in the germ line of many metazoa contain proteins involved in initiation and regulation of translation and mRNA decay, consistent with their likely role in regulating expression of maternal mRNA (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). In C. elegans, RNA has previously been observed at increased levels on P granules of females lacking sperm, and in the gonad core and oocytes of old, wild-type hermaphrodites (Schisa et al., 2001; Jud et al., 2007). Here, we show high levels of RNA are present not only on P granules, but also in foci in the core and oocytes of young female worms (Figs. 2C, D), similar to old, wild-type hermaphrodites. The changes in RNA localization throughout the germ line, in multiple examples where ovulation is arrested, suggest that delays in fertilization of oocytes require modifications to maternal mRNAs that will be needed in early embryogenesis. During an extended period of quiescence, maternal mRNAs may need to be packaged differently or form different mRNPs in order to maintain their stability or translational repression. Interestingly, when ovulation is arrested, the gonad core and pachytene germ cells, in addition to the oocytes, exhibit dramatic changes in the localization of RNA and RNA-binding proteins (Fig. 2, Fig. 6; data not shown). Earlier studies, showing increased levels of RNA and decreased levels of PGL-1, GLH-1, and GLH-2 on P granules of pachytene germ cells in fem-1 females, first hinted at these types of changes in response to arrested ovulation (Schisa et al., 2001). Modifications of RNPs in the syncytial gonad core may be important for oocyte viability when ovulation is arrested. Since maternal mRNAs will need to be maintained for an extended time, formation of larger foci throughout the germ line may be necessary for RNA stability or continued repression of translation.

In arrested oocytes, the subcellular localization of RNP foci is cortical and variably perinuclear (Figs. 3F, G); this pattern is strikingly similar to the localization of microtubules observed in unmated females (Harris et al., 2006). These observations, combined with the fact that microtubules play important roles in protein trafficking and RNA localization, raise the possibility that the dynamic changes in the microtubule cytoskeleton when ovulation is arrested are required for the RNP foci to assemble at the cell cortex. Additional support for the idea that microtubules and RNP foci are concomitantly regulated comes from two observations: one, MSP signaling in C. elegans controls both reorganization of oocyte microtubules and RNP foci (Harris et al., 2006; Figs. 5A, B), and two, disruption of microtubules stimulates P body formation in yeast (Sweet et al., 2007).

The oocyte RNP foci characterized in this paper share several characteristics with two, well-described RNPs, P bodies and stress granules. The oocyte RNPs are dynamic, forming within 8 hours post-L4 in fog-2(q71) females, between 89–91 hours post-L4 in old, wild-type animals, and within 2 hours after heat shock (Fig. 3; data not shown). P bodies and stress granules are also quite dynamic. Formation of P bodies occurs within 10 and 15 minutes of glucose deprivation and osmotic shock, respectively (Teixeira et al., 2005); formation of stress granules in the human cell line, DU145, is observed within 20 minutes in response to heat shock (Kedersha et al., 1999). Oocyte RNP foci also form reversibly; they appear to dissociate within 65 minutes of mating into sperm-depleted animals (Figs. 3K, L). P bodies and stress granules also form reversibly; P body proteins are no longer seen in foci after a 10-minute exposure to cycloheximide (Teixeira et al., 2005). Disassembly of GFP-TIA-1 stress granules occurs within 60–90 minutes of recovery (Kedersha et al., 2000). The dynamic and reversible nature of RNP foci likely reflects their function. In both P bodies and stress granules, some of the nontranslating mRNA has been shown to return to polysomes and be translated after cells are allowed to recover from the stress (Nover et al., 1989; Brengues et al., 2005; Bhattacharyya et al., 2006). Although our experiments do not address this question directly for RNP foci in C. elegans oocytes, correlative data suggest that only nontranslating mRNAs are present in the foci (Schisa et al., 2001).

The components of P bodies include mRNA, the decapping enzymes Dcp2 and Dhh1, and RAP55 (Ingelfinger et al., 2002; Sheth and Parker, 2003; Bloch et al., 2006). Our results examining the orthologs of these three proteins demonstrate that in each case, the localization of the protein changes dramatically in oocytes of females with arrested ovulation. The P body proteins also co-localize, at least partially, with previously defined markers of oocyte foci, MEX-3 and PGL-1 (Fig. 6; Schisa et al., 2001). DCP-2 co-localizes with MEX-3 in large foci in arrested oocytes and appears to occupy subdomains within some of the larger MEX-3 foci (Fig. 6F), and CGH-1 co-localizes with GFP in GFP::MEX-3; fog-2(q71) worms (Fig. 6L). Supporting the idea that MEX-3 co-localizes with P bodies, a recent study has identified two human orthologs of MEX-3 that localize to P bodies in cultured cells (Buchet-Poyau et al., 2007). CAR-1, the ortholog of RAP55, co-localizes tightly with CGH-1 in the oocyte RNP foci (Fig. 6R) and incompletely co-localizes with PGL-1 (Fig. 6X; Boag et al., 2005; Audhya et al., 2005). DCP-2, CAR-1, and CGH-1 have previously been shown to partially co-localize with P granules; therefore, their redistribution into large foci in arrested oocytes could simply represent a redistribution of P granules within oocytes. However, in wild-type oocytes a large amount of CAR-1 and CGH-1 is localized to distinct, P body-like foci and is diffusely cytoplasmic (Boag et al., 2005; Navarro et al., 2001). In arrested oocytes, a greater proportion of the P body proteins appear to localize with P granule proteins. This appearance could be explained by the aggregation of cytoplasmic P granules with P bodies into the larger RNP foci. The different distribution of these proteins may reflect novel functions required in arrested oocytes to maintain an essentially quiescent state for a prolonged period of time.

Stress granules differ from P bodies in several ways: they are stalled translation initiation complexes and contain portions of the small ribosomal subunit; they require eIF2α phosphorylation; and they form only in cells subjected to environmental stresses (Kedersha et al., 2005). In our efforts to characterize the RNP foci in arrested oocytes, we tried to determine whether they are more similar to P bodies or stress granules. When we asked whether two proteins considered markers for stress granules localize to MEX-3 foci in arrested oocytes, we found both did. Not only do the stress granule proteins PAB-1 and TIA-1 co-localize with MEX-3 in foci (Fig. 7C, data not shown), but so do the P body proteins, DCP-2 and CGH-1 (Figs. 6F, L). These results suggested that P body and stress granule proteins are present within the same large RNP structure. Co-staining of DCP-2 and GFP in LAP::PAB-1 purged worms verified that P body proteins and stress granule proteins appear to incompletely co-localize and dock adjacent to one another in arrested oocytes (Fig. 7E; Supplementary Figs. 2F–I) (n = 70). Previous studies have also suggested a close relationship between P bodies and stress granules. In real-time fluorescence imaging studies, stress granules appear relatively fixed, but processing bodies are highly motile; when a motile P body encounters a stress granule, it transiently tethers itself or “docks” on the stress granule (Kedersha et al., 2005). In other studies, proteins such as RAP55 move between P bodies and stress granules, depending on the condition/ environment of the cell (Bloch et al., 2006). Our data, therefore, are consistent with previous studies, and to our knowledge are the first in vivo demonstration linking stress granule proteins and processing body proteins in the germ line of a metazoan.

MSP signaling negatively regulates RNP foci in oocytes

RNP foci form reversibly as a part of normal development in C. elegans. The initial observation of RNP foci formation in oocytes was in old animals that had been depleted of sperm and had arrested ovulation (Schisa et al., 2001). Analyses of several feminized mutants, fem-1(hc17), fog-2(q71), and fer-1(hc1), demonstrate that old age is not required for RNP foci formation; rather, an absence of sperm and arrested ovulation are tightly correlated with their formation in oocytes (Schisa et al., 2001; Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs. 1A, B). Examination of additional mutants where sperm are present but ovulation is arrested indicate that the presence of sperm may be sufficient to prevent the formation of large RNP foci in oocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1C; data not shown); however, small foci of MEX-3 are observed in oocytes when either sheath cell contractions fail or ovulation fails for other reasons. These observations suggest that regardless of the component that fails in signaling ovulation, sperm, oocyte, or sheath cell, a common mechanism may be triggered in arrested oocytes. Our results are consistent with the idea that all oocytes undergoing a delay in fertilization require additional protective mechanisms to maintain their viability during prolonged quiescence, and formation of MEX-3 foci is part of that mechanism. The failure to detect large MEX-3 foci in mutants where sperm are present is consistent with the idea that sperm negatively regulate foci formation. Moreover, providing a new supply of sperm to a sperm-depleted animal is sufficient to dissociate MEX-3 foci (Figs. 3K, L).

The component of sperm that promotes MAPK activation in oocytes, meiotic maturation, and ovulation is major sperm protein (MSP) (Miller et al., 2001). Using microinjection of MSP into the vulva of female worms, we have shown that MSP is sufficient to partially dissociate MEX-3 foci (Fig. 5A). However, the effect of MSP injection is not identical to the effect of mating into female worms. Within approximately 65 minutes of mating, foci are no longer detectable in any of the accumulated oocytes (Fig. 3L), while at a similar time point after injection of MSP, foci remain visible in the more distal oocytes (Fig. 5A). Several caveats may explain this observation. One possibility is simply the limitations of injection experiments; by injecting recombinant MSP protein into the vulva, we are only approximately simulating the process of mating where a male deposits whole sperm into the female. Another explanation may be the fact that endogenous MSP is secreted from sperm, and transits to oocytes and sheath cells in vesicles (Kosinski et al., 2005). The importance of the vesicles for MSP function is not well understood but is clearly lacking in our injection experiments. Interestingly, when we inject MSP into the gonad core, instead of the vulva, we observe dissociation of MEX-3 foci in nearly all of the accumulated oocytes (Fig. 5B). Although injection of MSP via this route has not been previously shown to regulate meiotic maturation, and the organization of the oocytes within the gonad was altered suggesting possible non-specific effects of the injection, this result is consistent with the idea that delivering recombinant MSP directly into the germline elicits more robust signaling to dissociate RNP foci in oocytes.

Additional evidence that the MSP signaling pathway negatively regulates RNP foci formation comes from our analyses of mutants in the MSP pathway. Two branches of the MSP pathway have been resolved in several recent studies; one pathway involves the VAB-1 Eph receptor protein tyrosine kinase on oocyte membranes, and the other is a sheath cell-dependent pathway involving the POU-homeodomain protein, CEH-18 (Miller et al., 2003; Corrigan et al., 2005; Govindan et al., 2006). Examination of vab-1(dx31); fog-2(q71) animals demonstrated that MEX-3 foci form in ooctyes similar to that observed in fog(q71) animals (Fig. 5C); however, MEX-3 foci failed to form in a ceh-18(mg57); fog-2(q71) female (Fig. 5D). Therefore, we conclude that MSP signaling through the sheath cells is required to promote or relieve the negative regulation of RNP foci formation. Additional analyses of three mutants, kin-2(ce179), gsa-1(ce81gf), and goa-1(sa734), in the absence of sperm (Figs. 5E, F; data not shown) are consistent with the idea that a G protein signaling pathway, that is sensitive to MSP in the somatic sheath cells, regulates RNP foci formation.

Throughout our experiments studying the regulation of RNP foci formation in oocytes, we were struck by many similarities to the regulation of cytoskeleton rearrangements in oocytes (Harris et al., 2006). The first similarity is the sperm-dependent, dynamic, and reversible change that occurs in both the microtubule cytoskeleton and RNP foci. In the absence of sperm, microtubules in oocytes are enriched at the proximal and distal cortices, as are large RNP foci. The presence of sperm or MSP promotes the remodeling of microtubules into a dispersed, net-like distribution, and also dissociates the large RNP foci (Harris et al., 2006; Fig. 3J; Figs. 5A, B). The similarities in distribution, and sensitivity to the presence of MSP, suggests a functional relationship between the microtubule cytoskeleton and RNP foci (Table 1). A second similarity further supports this idea. While MSP signaling activates MAPK activation in oocytes (Miller et al., 2001), high MAPK levels are required neither for oocyte microtubule reorganization, nor for the negative regulation of RNP foci (Table 1). Experiments using pharmacological inhibitors of MAPK or reduction of mpk-1 activity suggest that MAPK activation is not essential for MSP-dependent reorganization of microtubules (Harris et al., 2006). Our data show that in two mutants where sperm are present, but MAPK is at lower levels than wild type, no RNP foci form, and in one mutant where sperm are absent but MAPK levels are higher than in fog-2(q71), RNP foci form (Figs. 4E–J). These observations are consistent with MSP regulating foci formation independent of MAPK activation; however, they do not exclude the possibility that MAPK activation contributes to the negative regulation of RNP foci in wild-type animals.

Oocytes respond to arrested ovulation and environmental stresses in similar ways

The RNP foci that form in arrested oocytes are similar to stress granules and P bodies not only in their components, but also in how they can be induced. We have demonstrated that MEX-3 foci form in oocytes of animals subjected to heat-shock (Figs. 8C, D), and the foci increase in size as the time of exposure to heat shock increases. Interestingly, HeLa cells exposed to heat shock for 15 and 30 minutes form stress granules but not P bodies; however, one hour of heat shock results in the disappearance of stress granules and the appearance of P bodies (Kedersha et al., 2005). Thus the dynamics of all three RNPs, oocyte RNP foci, stress granules, and P bodies, change as a function of the length of time of cellular stress. Stated another way, it seems that there are multiple mechanisms that can induce oocyte foci to form, including lack of sperm, arrested ovulation, heat shock, anoxia, and osmotic shock. These inputs can have an additive effect on the size of the RNP foci (Fig. 3H). However, if foci have formed in response to both a lack of sperm and heat shock, lowering the temperature is not sufficient to dissociate all of the RNP material (Fig. 3I).

In addition to MEX-3, the oocyte foci that form in response to heat shock include PAB-1 and TIA-1, two common components of stress granules (Fig. 7C; data not shown; Table 2), and DCP-2, a P body protein (Fig. 7D). Heat shock also induces the formation of large RNA foci in oocytes, very similar to those that form in arrested oocytes when sperm are depleted (Fig. 2F). Thus, compared to the components of RNP foci in arrested oocytes, the components of heat shock-induced foci are nearly identical (Table 2). The only difference we have detected is that the P granule component, PGL-1, associates with foci in arrested oocytes but becomes evenly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of heat shock oocytes. Although we do not know the significance of this difference, it is reminiscent of the cytoplasmic distribution of PGL-1 observed in glh mutants (Kawasaki et al., 1998; Kuznicki et al., 2000). Overall, the fact that heat shock induces such similar changes in RNPs in oocytes, suggests that the prolonged quiescence observed when ovulation arrests may require cellular responses most often observed in stressed cells. Since these changes in RNPs affect the stability and translational repression of mRNAs, perhaps it should not be surprising that similar cellular mechanisms occur in these disparate cell types. For both cells exposed to a stress and oocytes waiting to be fertilized, it is imperative that “specialized” mRNAs are maintained or preserved. Many examples in Xenopus, for example, where maternal mRNAs are stored for years, show the necessity of regulating stability and translation of maternal mRNAs (Davidson, 1986).

The small foci that form in oocytes after osmotic stress or anoxia have fewer components in common with RNP foci in arrested oocytes or after heat shock (Table 2). For example, although both hypotonic and hyperosmotic stress induces an increase in the number and size of P bodies in yeast (Uesono and Toh-e, 2002), P body proteins were not detected in large cytoplasmic foci after osmotic shock (data not shown). One possible explanation for the differences observed among the different stresses is that the method of applying the stress was not efficient or optimal to observe responses in oocytes. In our osmotic stress experiments, we soaked the worms in a high salt solution for one hour. We performed a short time course and dose response curve, and within the ranges, the most dramatic changes in GFP::MEX-3 distribution, or largest foci, were observed after one hour in 500mM NaCl. Thus, we used those parameters consistently when examining the distribution of the other potential foci components. Although it is difficult to interpret negative data, the fact that RNA was not observed in foci at high levels may be significant. Interestingly, although neither PAB-1 nor TIA-1 was observed in cytoplasmic foci after osmotic shock, TIA-1 was reproducibly observed in nuclear foci (Fig. 7B). The appearance of the nuclear foci was somewhat reminiscent of mini-Cajal bodies that have been observed in the germinal vesicle of oocytes after heat shock (Handwerger et al., 2002). A second possible explanation for the differences observed among the different stresses is that they are meaningful and that oocytes do not respond identically to different types of cellular stresses. Clearly, in the many stress granule studies performed in cell culture, variable responses are observed. Depending on the type of cell line, different stresses are effective in inducing stress granule formation. Moreover, different components are observed within stress granules in different cell lines (Kedersha et al., 1999; Touririere et al., 2003).