Abstract

The ligand specificity of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) is determined by the alternative splicing of exons 8 (IIIb) or 9 (IIIc). Exon IIIb is included in epithelial cells, whereas exon IIIc is included in mesenchymal cells. Although a number of cis elements and trans factors have been identified that play a role in exon IIIb inclusion in epithelium, little is known about the activation of exon IIIc in mesenchyme. We report here the identification of a splicing enhancer required for IIIc inclusion. This 24-nucleotide (nt) downstream intronic splicing enhancer (DISE) is located within intron 9 immediately downstream of exon IIIc. DISE was able to activate the inclusion of heterologous exons rat FGFR2 IIIb and human β-globin exon 2 in cell lines from different tissues and species and also in HeLa cell nuclear extracts in vitro. DISE was capable of replacing the intronic activator sequence 1 (IAS1), a known IIIb splicing enhancer and vice versa. This fact, together with the requirement for DISE to be close to the 5′-splice site and the ability of DISE to promote binding of U1 snRNP, suggested that IAS1 and DISE belong to the same class of cis-acting elements.

Alternative splicing of a given pre-mRNA can lead to changes in the open reading frame of the mature mRNA, imparting tremendous diversity to the proteome (1-3). The protein isoforms encoded by alternative splicing can have significantly different activities. A salient example of this is the production of different isoforms of the fibroblast growth factor receptor-2 (FGFR2),4 where isoform FGFR2(IIIb) has a high affinity for FGF7 or keratinocyte growth factor while isoform FGFR2(IIIc) preferentially binds FGF2 (Basic FGF) (4, 5). These isoforms arise because of the alternative inclusion of exon 8 (IIIb) or exon 9 (IIIc). This alternative splicing event is regulated in a cell type-specific manner such that epithelial cells produce FGFR2(IIIb) and mesenchymal cells produce FGFR2(IIIc). This tissue-specific exon choice is the outcome of complex regulation involving multiple cis elements and trans factors (6-8).

cis-Acting elements within FGFR2 transcripts activate exon IIIb, repress IIIc, or do both simultaneously in epithelial cells (see Ref. 6 and references within). In contrast to this multifaceted regulation in epithelial cells, the only cis elements known to be active in mesenchymal cells are silencers of exon IIIb (7). Therefore, the choice of exon IIIc in these cells was presumed to be by default, i.e. mediated solely by the splice sites flanking the exon (8). More recently Mauger and Garcia-Blanco have shown that the factor SFRS1 (also known as ASF/SF2) activates exon IIIc by binding an exonic splicing enhancer (ESE) and antagonizing hnRNP H/F proteins that bind an overlapping silencer.5

In this article, we revise this simple model in light of the identification of an intronic enhancer element that was absolutely required for the efficient inclusion of the rat FGFR2 IIIc. This enhancer was localized to a phylogenetically conserved region of intron 9 just downstream of exon IIIc. This newly identified enhancer, named downstream intronic splicing enhancer (DISE) spans 24 nt that are essential for its activity. Our characterization of DISE and its properties revealed that it was capable of activating heterologous FGFR2 exons IIIb and the human β-globin exon 2 when it was placed just downstream of these exons. The activity of DISE was critically dependent on its distance from the 5′-splice site and its intronic location. Finally, we show here that DISE was also capable of replacing a known IIIb splicing enhancer, IAS1, located in intron 8 and vice versa. We propose that DISE belongs to a class of ISEs that inhabit intronic regions immediately downstream of the exons they regulate.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction—Minigenes pI-11-FS (8), pI12-IIIb-WT (9), human β-globin (10), pRint (11, 12), and pRIIIcI2 (12) have all been previously described. All substitutions and deletions were introduced using chimeric PCR, and all products were confirmed by sequencing. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Cell Culture and Transfections—Rat DT3 and AT3 cells were cultured in low glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone). HeLa cells, human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells, and murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were cultured in High Glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Stable transfection and selection of stable cell lines with G418 was performed as described previously (13). Transient transfections of MEFs were carried out by the following protocol: 1 day prior to transfection, MEFs were plated at a density of 300,000 cells per well of a Falcon six-well plate (BD Biosciences). The following day, 1000 ng of test minigene constructs were added to 100 μl of OptiMEM (Invitrogen). 5 μl of Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) premixed with 100 μl of OptiMEM was then added to the DNA-OptiMEM mixture. The mix was incubated at room temperature for 15-20 min, after which an additional 800 μl of OptiMEM was added, and the transfection mixture was gently overlaid on cells. The transfection mixture was left on cells for 2-4 h, after which it was replaced by Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. At 48 h from the start of transfections, cells were harvested, and RNA was extracted for RT-PCR analysis. All stable and transient transfections were performed in triplicate for each construct.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR Assay—Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers and MMLV-RT (Invitrogen) using the manufacturer's instructions. PCR using T7 and SP6 primers were performed as described previously (8). PCR products were loaded directly on a 5% polyacrylamide non-denaturing gel for analysis. Gels were run at 100 V for 3-4 h, dried using a gel dryer, and exposed to Amersham Biosciences Hyperfilm-MP or Molecular Dynamics phosphorimager screens. Quantification of PCR products was performed with ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). In each case, RT-PCR products were corrected for molar equivalence. Percentage of a specific product in each lane was calculated by taking the arbitrary units for the product of interest as the numerator and the sum of the arbitrary units of all products in the same lane as the denominator. For example, to calculate percent single inclusion, the following formula was used: ((single inclusion product)/(double inclusion product + single inclusion product + skipped product)) × 100. Each was the result of the average of triplicate samples with error bars representing S.D.

Western Blot—Transfected cells from overexpression and knockdown studies were harvested, and cell lysates prepared and Western blot performed as described elsewhere (6). The goat polyclonal anti TIA1 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and the PTB antibody was described elsewhere (14). A dilution of 1:2,000 with the blocking buffer was used for both the antibodies.

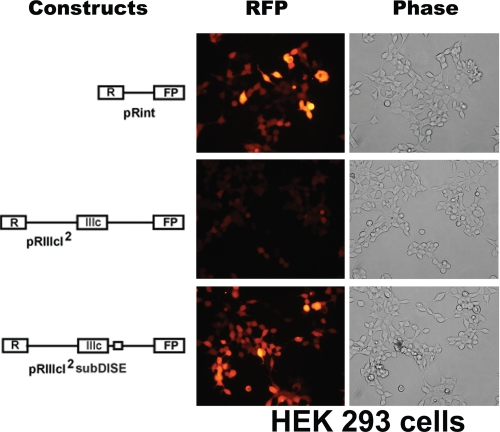

Fluorescence Microscopy—HEK293 cells were stably transfected with pcDNA6-based RFP reporter constructs, pRint, pRIIIcI2, or pRIIIcI2subDISE. After blasticidin selection, cells were imaged using an Olympus IX71 epifluorescence microscope and Olympus DP70 digital camera with identical exposure times (Olympus Technologies, Ltd.).

In Vitro Splicing—For Fig. 8, the reactions for in vitro splicing experiments were performed as previously described (10). Briefly, plasmid DNA containing the entire human β-globin sequence was digested with BsrBI (NEB) that cuts upstream of the T7 promoter and downstream of the gene. After purification by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, 1 μg of the linearized template was used for each in vitro transcription reaction with T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion).

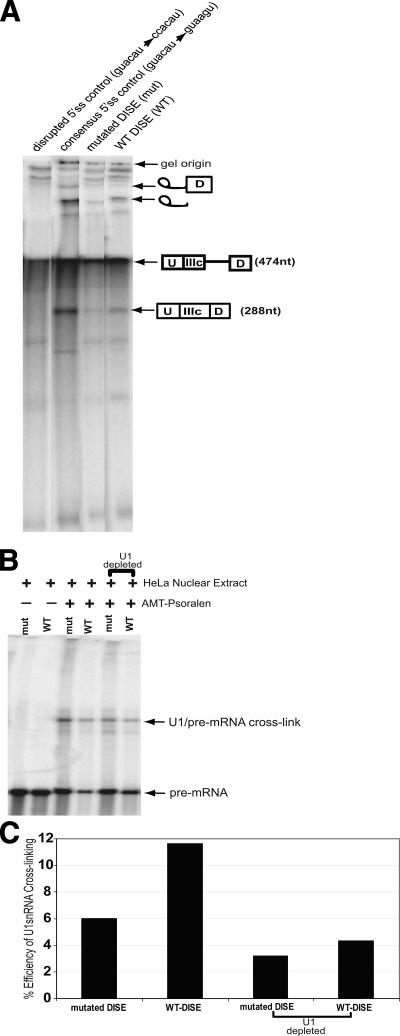

FIGURE 8.

DISE can activate a constitutive exon in an in vitro splicing system. A, schematic of the human β-globin constructs used in the in vitro experiments (see “Experimental Procedures”). In the β-globin-R1 construct, 45 nt in β-globin intron 2 were substituted with the R1 region from FGFR2, and in the β-globin-R1mut construct, the 45 nt of R1 were mutated by transversions. B, denaturing polyacrylamide gel shows the products of a reverse RNase protection assay (10) used to detect the levels of spliced β-globin transcripts derived from the constructs in A. Reactions for each construct were performed in triplicate, and splicing was stopped after 30 or 60 min of incubation. The RNase protection products for fully spliced (123), partially spliced (12), or unspliced RNAs (1, 2, and 3) are indicated to the right of the gel. C, splicing efficiencies were calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate reactions.

After DNase treatment, the radiolabeled transcripts from the above described constructs were then added to HeLa nuclear extract and incubated at 30 °C for splicing to occur. A reverse RNase protection assay (RPA) was used to detect spliced and unspliced products (10). Samples were run on a denaturing 10% polyacrylamide/8 m urea gel and exposed to Amersham Biosciences Hyperfilm-MP or Molecular Dynamics phosphorimager screens. ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics) was used to quantify splicing efficiency as previously described (10). The splicing efficiency of the fully spliced β-globin product (1 + 2 + 3) was calculated by the following formula: (moles (1 + 2 + 3)/(moles (1 + 2 + 3) + moles 3)) × 100. The splicing efficiency of the partially spliced β-globin product (1 + 2) was calculated by the following formula: (moles (1 + 2)/(moles (1 + 2) + moles 2)) × 100.

For Fig. 9A, the FGFR2 pre-mRNAs were transcribed in vitro from HindIII-linearized pDP19 (Invitrogen)-based plasmids into which the FGFR2 minigene sequence had been subcloned. In the controls which were used in Fig. 9A, the endogenous 5′-splice site was mutated from gtacat (WT) to gtaagt (consensus) or from gt to cc (non-consensus) using chimeric PCR. After DNase treatment, 100,000 cpm of each transcript was used in a conventional in vitro splicing reaction. Purified products were resolved on a denaturing 15% polyacrylamid/8 m urea gel and exposed to Amersham Biosciences Hyperfilm-MP or Molecular Dynamics phosphorimager screens.

FIGURE 9.

DISE affects splicing via enhanced binding of U1 snRNA. A, denaturing poly-acrylamide gel showing the products of a conventional in vitro splicing experiment performed with HeLa nuclear extracts, using the pre-spliced FGFR2 minigenes (UIIIc-D) with either WT-DISE (WT) or mutated DISE (mut) as substrates. WT with the 5′-splice site mutated to either the consensus sequence or a non-consensus sequence were used as controls in this experiment. The pre-spliced substrate (UIIIc-D), the fully spliced product (UIIIcD), and the splicing intermediates are indicated on the right side of the gel. Lanes, which were cropped for clarity, are all from the same gel. B, denaturing polyacrylamide gel showing the products of an U1 snRNA cross-linking reaction using AMT-Psoralen. Radioactively labeled FGFR2 pre-spliced substrates (UIIIc-D) with either the WT-DISE (WT) or mutated-DISE (mut) were incubated with HeLa nuclear extract in either the presence or absence of AMT-Psoralen. U1-depleted HeLa nuclear extract was used as a control. After UV irradiation, RNA was isolated and resolved on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The position of the uncross-linked RNA and the product of cross-linking to U1 snRNA are indicated. C, quantification of cross-linking efficiency of the experiment shown in B. Cross-linked and uncross-linked products were quantified with ImageQuant, and the % efficiency of U1 snRNA cross-linking was calculated as the fraction of cross-linked RNA out of total RNA (cross-linked + uncross-linked) (see “Experimental Procedures”).

Psoralen-mediated UV Cross-linking—RNase H-mediated U1 inactivation was also performed as described elsewhere (15). Briefly, U1 snRNA was depleted from the HeLa nuclear extracts using either an oligonucleotide complementary to the first 15 nucleotides of U1 snRNA or a noncomplementary, unrelated oligonucleotide as a control. The U1 snRNA depletion was confirmed by running proteinase K-treated HeLa nuclear extracts on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and staining with ethidium bromide. Then the radioactively labeled pre-mRNAs (10 fmol) were incubated with 4.2 μl of HeLa nuclear extract (∼5.8 μg protein/μl). After a 5-min incubation at 30 °C, reactions were placed on ice and AMT-Psoralen (Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 20 μg/μl. Reactions were then transferred to a prechilled 96-well plate and irradiated with 365-nm UV light for 10 min on ice. RNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The cross-linked products were then resolved on a 5% polyacrylamide, 8 m urea gel at 50 watts for 1.5 h. Gels were visualized by a PhosphorImager and quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). The % efficiency of U1 snRNA cross-linking was calculated as the fraction of cross-linked RNA out of total RNA (cross-linked + uncross-linked).

RESULTS

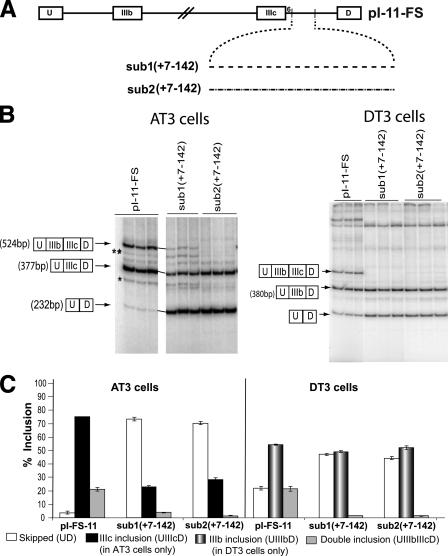

The 5′-End of FGFR2 Intron 9 Contains an Enhancer That Activates Exon IIIc Inclusion—Phylogenetic analysis of FGFR2 intron 9 across six species of mammals, encompassing five different orders, revealed high sequence conservation of the first ∼110 nt (supplemental Fig. S1). We decided to investigate the presence of a cis element in these conserved and previously understudied intronic sequences immediately downstream of exon IIIc. The pI-11-FS minigene, which had previously been shown to recapitulate FGFR2 splicing regulation (Fig. 1A) (8), was used to evaluate the function of these sequences. We substituted nt +7 to +142 of intron 9 in pI-11-FS with two different and unrelated sequences, sub1 and sub2, which come from FGFR2 intron 8 and contain no known regulatory cis elements (13). pI-11-FS, sub1(+7-142) and sub2(+7-142) were transfected in AT3 cells and stable populations of AT3 cells bearing these minigene reporters were established. In these cell lines, exon IIIc is usually included to high levels, as seen with pI-11-FS RNAs. The great majority (75%) of these transcripts were single inclusion products and essentially all of these included exon IIIc (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Another 20% of the transcripts included both exons IIIb and IIIc (double inclusion) and a small fraction (<5%) skipped both exons (Skipped (UD)) (Fig. 1C). Therefore the fraction of pI-11-FS transcripts that included exon IIIc in AT3 cells was ∼95%. In contrast, sub1(+7-142) and sub2(+7-142) transcripts did not include exon IIIc efficiently (< 30%) (Fig. 1, B and C and data not shown).

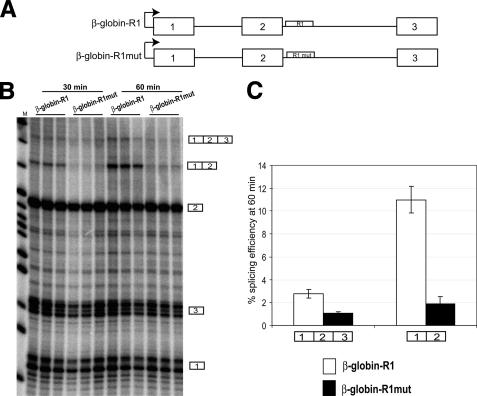

FIGURE 1.

An enhancer of exon IIIc within FGFR2 intron 9. A, schematics of minigene constructs pI-11-FS, sub1(+7-142), and sub2(+7-142) (see “Experimental Procedures”). B, representative gels showing products of RT-PCR reactions primed in exons U and D from total RNA extracted after transfection of the above minigenes in AT3 and DT3 cells, respectively. The double inclusion (U-IIIb-IIIc-D), single inclusion (U-IIIc-D), and skipped (U-D) products are indicated, as are the single inclusion bands UIIIcD and UIIIbD in AT3 and DT3 cells, respectively. Bands ** and * represent double inclusion and single inclusion products, respectively, derived from the use of a cryptic 5′-splice site within exon IIIc (miniIIIc). C, % inclusion for exon IIIc and IIIb from the indicated reporter transcripts in AT3 and DT3 cells, respectively, was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent the S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (U-D), single inclusion (UIIIcD in AT3 cells and UIIIbD in DT3 cells) and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products.

We also transfected these minigene reporters in DT3 cells, which include exon IIIb in the endogenous FGFR2 transcripts. Indeed, essentially all of the single inclusion pI-11-FS transcripts contained exon IIIb. Inefficient inclusion of exon IIIc in these cells was noted among pI-11-FS transcripts that included both exons IIIb and IIIc (double inclusion in Fig. 1C). We noted that sub1(+7-142) and sub2(+7-142) RNAs had a major effect on the level of double inclusion transcripts (Fig. 1C). The data also suggested that substitution of nt +7 to +142 led to a modest decline in overall exon IIIb inclusion (Fig. 1C); however, all of this effect was noted among double inclusion products (see “Discussion”).

When the minigenes with a deletion of nt +7 to +142 were transfected in AT3 cells, we noted a marked decrease in exon IIIc inclusion (data not shown), which was consistent with the results of the substitution analysis presented above. Nonetheless, this deletion, which significantly decreased the size of the third intron in pI-11-FS (from 187 to 51 nt), led to the use of a cryptic 5′-splice site within exon IIIc (data not shown). The use of this site produces a smaller exon, which we call miniIIIc. This product was detected even among splicing products of pI-11-FS (U-miniIIIc-D and U-IIIb-miniIIIc-D are indicated by * and **, respectively, in Fig. 1B). This site is equivalent to the human IIIc cryptic 5′-splice site shown to be activated in a patient with Crouzon's syndrome (16). In calculating percentages of exon IIIc inclusion, we do not take into account the miniIIIc contributions because these are minimal.

Because the action of this ISE was observed most clearly in AT3 cells, which include exon IIIc efficiently, we carried out all of subsequent experiments in AT3 cells, except where specifically noted.

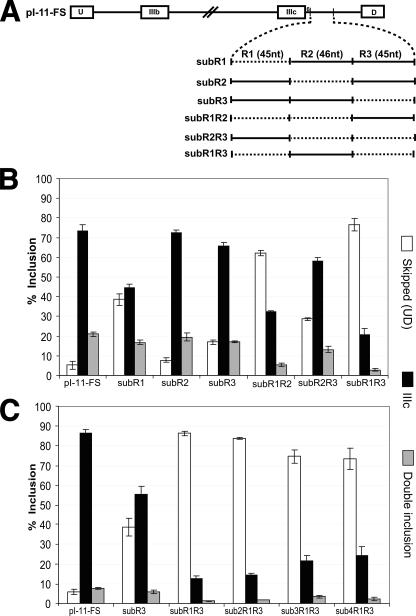

All of the data presented above indicated that nt +7 to +142 of intron 9 harbor one or more ISE element(s) required for efficient inclusion of exon IIIc. To characterize the location of the ISE(s), we arbitrarily divided nt +7 to +142 of intron 9 into regions R1, R2, and R3, of 45, 46, and 45 nt, respectively (Fig. 2A) and constructed substitutions of each. Among the single substitutions, replacement of R1 (subR1) led to a significant fall in IIIc inclusion from 73 to 44%, while substitution of R2 (subR2) or R3 (subR3) did not have a large effect on IIIc inclusion (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that region R1 was necessary for efficient IIIc inclusion. We also tested double substitutions and found that replacement of R1 and R3 (subR1R3) resulted in the most dramatic decrease in IIIc inclusion from 73 to 21% (Fig. 2B). We also noted that replacement of R2 and R3 (subR2R3) decreased IIIc inclusion only very modestly, indicating that R1 was sufficient to account for the majority of the enhancer activity observed in nt +7 to +142.

FIGURE 2.

The ISE lies within the R1 region of intron 9. A, schematic of constructs used in sections B and C. Substitutions are shown schematically by the broken horizontal line. The solid horizontal line indicates sequences from the rat FGFR2 gene. The vertical solid lines indicate the boundaries of regions R1, R2, and R3. B and C, % inclusion for exon IIIc from the indicated reporter transcripts in AT3 cells was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent the S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD), IIIc (UIIIcD), and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products.

The decrease in IIIc inclusion with subR1R3 minigene relative to subR1 suggested that an element within R3 could partially compensate for the absence of R1. Therefore, to sensitize our assay for R1 action, we made all further intron 9 substitution constructs in the context of subR3.

To rule out the possibility that exon IIIc inclusion was decreased in subR1 by the inadvertent introduction of a silencer, we made three other constructs in which the substitution sequences were derived from downstream regions of rat FGFR2 intron 9 (minigenes sub2R1R3 and sub3R1R3) or from human β-globin intron 2 sequences (sub4R1R3) (Fig. 2C). All of these substitutions of R1 in the context of subR3 behaved similarly to subR1R3 essentially ruling out that the effect of substituting R1 could be explained by the inadvertent introduction of a silencer. These data indicate that R1 contains an enhancer element (or elements), which is necessary for efficient exon IIIc inclusion.

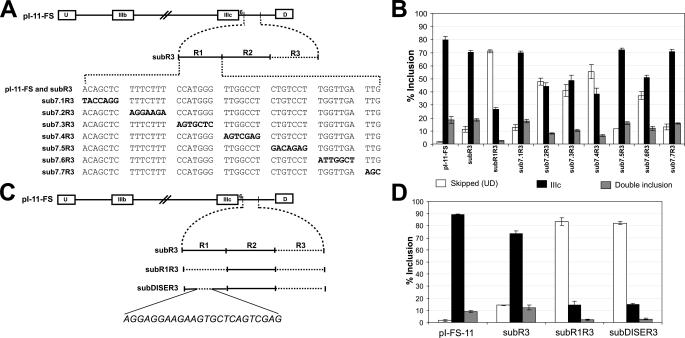

To characterize the boundaries of the enhancer, we scanned the R1 region with six 7-nt substitutions (sub7.1R3 through sub7.6 in Fig. 3A). Additionally, the last three nt of R1 were substituted in sub7.7R3. sub7.1R3, sub7.5R3, and sub7.7R3 had the same levels of IIIc inclusion as subR3 transcripts. In contrast, sub7.2R3, sub7.3R3, and sub7.4R3, which are adjacent and span from +14 to +34 of intron 9, and sub7.6R3 (substitution of +42 to +48) led to decreased IIIc inclusion (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, when substitutions 7.2 and 7.6 were combined into the same minigene (sub7.26R3) IIIc inclusion was down to ∼36%, which was significantly lower than the levels observed with either sub7.2R3, 43%, or sub7.6R3, 45%, alone (data not shown). These results suggested that R1 contained either a bipartite ISE or two elements that co-existed within R1. As noted below, we have data that suggest that the +42-48 sequence contains a second and separable element of secondary importance. Based on these data we tentatively defined nt +14 to +34 as the DISE.

FIGURE 3.

DISE spans nt +11 to +34 of FGFR2 intron 9. A, schematic showing the scanning 7-nt substitutions made in the constructs used in section B. B,% inclusion for exon IIIc from the indicated reporter transcripts in AT3 cells was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD), IIIc (UIIIcD), and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products. C, schematic showing the constructs used in section D. DISE was defined as the 24-nt region spanning nucleotides +11 to +34 of the rat FGFR2 intron 9. The sequence shown in italics is the mutated sequence in the subDISER3 minigene. D, % inclusion for exon IIIc from the indicated reporter transcripts in AT3 cells was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD), IIIc (UIIIcD), and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products.

We further characterized the margins of DISE by scanning the R1 region with 3-nt transversions. The results from these were fully consistent with those obtained with the 7-nt transversions with one salient exception (data not shown). Substitution of +11 to +13 (CTC to AGG) led to a modest decrease in exon IIIc inclusion (data not shown), and this was not easily reconciled with the lack of effect observed with sub7.1R3 (Fig. 3A). Although we have not explained these paradoxical results, we believe that in some contexts, nt +11 to +13 play a role in enhancer function, and therefore we extended our definition of DISE to span nt +11 to +34. To test this directly, we substituted these 24 nt in minigene subDISER3 (Fig. 3C). Indeed, replacement of these 24 nt resulted in a decrease in IIIc inclusion that was equivalent to that seen by replacing the complete R1 region (compare subDISER3 with subR1R3 in Fig. 3D). Based on these results, we concluded that DISE was necessary for efficient inclusion of exon IIIc and accounted for the most important enhancing activity found in region R1.

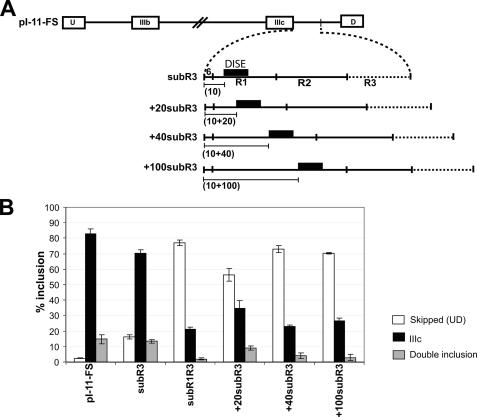

DISE Activity Depends on Its Intronic Location—The fact that DISE spans nt +11 to +34 of intron 9 led us to question whether its activity depended on proximity to the 5′-splice site. We increased the distance between DISE and the 5′-splice site by 20, 40, and 100 nt in the +20subR3, +40subR3, and +100subR3, minigenes, respectively (Fig. 4A). The insertion sequences used to distance DISE from the 5′-splice site were derived from downstream regions of intron 9 that had been previously used in the minigene sub2R1R3. Addition of 20 nt between the 5′-splice site and DISE was sufficient to reduce exon IIIc single inclusion from 70 to 34%, and addition of 40 nt reduced this further to levels observed with the negative control subR1R3 (Fig. 4B). We concluded from these data that exon activation by DISE requires proximity to the 5′-splice site.

FIGURE 4.

DISE activity depends on its proximity to exon IIIc. A, schematic showing the insertions made to distance DISE from the 5′-splice site in the constructs used in section B. B, % inclusion for exon IIIc from the indicated reporter transcripts in AT3 cells was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD), IIIc (UIIIcD), and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products.

The experiment above did not address whether DISE had to be downstream of a 5′-splice site (intronic location) or if it could also act when placed upstream of the splice site (exonic location). This question was not satisfactorily answered since DISE in an exonic context behaved like an exonic splicing silencer (ESS) (data not shown). Nonetheless, our results show that the effect of DISE on exon inclusion is strictly dependent on its distance to an upstream 5′-ss and suggest that DISE will not act as an ESE.

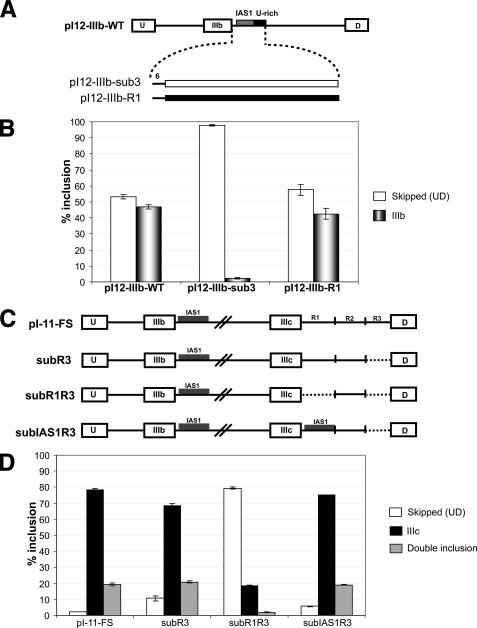

DISE and IAS1 Are Interchangeable Elements—Next, we asked whether or not DISE could activate another weak exon, and we tested this using the rat FGFR2 exon IIIb. Although it is found in the same transcript and is a cognate of FGFR2 IIIc, exon IIIb has evolved very different splice site sequences and regulation (17). Exon IIIb offered an additional advantage, because it is also activated by a well-characterized ISE, IAS1 (18-20). IAS1 is similar to DISE in size and location relative to the 5′-splice site, but is quite different in sequence. Thus, using exon IIIb, we could test not only whether DISE could work in a heterologous context, but also whether or not it could replace a known ISE.

To test whether or not DISE could activate exon IIIb we used the single exon (IIIb) minigene, pI12-IIIb-WT, which reports on IIIb inclusion in DT3 cells (9). We substituted nt +7 to +51 of FGFR2 intron 8, which includes IAS1, with either the R1 region of intron 9 or a size control (pI12-IIIb-R1 and pI12-IIIb-sub3, respectively, in Fig. 5A). No IIIb inclusion was observed in the case of pI12-IIIb-sub3 transcripts, but with pI12-IIIb-R1, inclusion of exon IIIb was very close to that seen with pI12-IIIb-WT (Fig. 5B). These results show that when DISE was placed downstream of exon IIIb, it was capable of substituting for IAS1 and promoting inclusion of this exon in DT3 cells. Whereas IAS1 has been defined in human FGFR2 as a 24-nt element downstream of exon IIIb (18-20), the boundaries of IAS1 in rat have not been well defined. Sequence alignment revealed that in rat FGFR2, the consensus IAS1 was followed by a 19-nt U-rich stretch that is not present in the human gene (data not shown). We substituted the 24-nt rat IAS1 consensus sequence with the 24-nt DISE or a size-matched control and showed that DISE could partially recover the loss of the 24-nt rat IAS1 (data not shown). These data demonstrated that DISE could activate a second weak exon and that it could replace a known ISE. These data also support the hypothesis that region R1 contained a second and separable element of secondary importance.

FIGURE 5.

DISE and IAS1 are interchangeable. A, schematic showing the insertions made in pI12-IIIb-WT to create constructs pI12-IIIb-sub3 and pI12-IIIb-R1 used in section B. B, % inclusion for exon IIIb from the indicated reporter transcripts in DT3 cells was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD) and single inclusion (UIIIbD) products. C, schematic showing the constructs used in section D. D, % inclusion for exon IIIc from the indicated reporter transcripts in AT3 cells was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent the S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD), IIIc (UIIIcD), and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products.

The experiment above showed that DISE could substitute for IAS1, and we wanted to test whether or not the reciprocal would hold true. We created a version of the subR3 minigene where DISE was replaced by nt +7 to +51 of rat FGFR2 intron 8 (subIAS1R3) (Fig. 5C). As shown before, pI-11-FS and subR3 transcripts incorporated exon IIIc efficiently (∼79 and ∼69%, respectively, for single IIIc inclusion) but substitution subR1R3 transcripts did not (∼20%) (Fig. 5D). Transcripts where IAS1 replaced DISE, however, recovered inclusion very efficiently (∼75%) (Fig. 5D). Therefore, we concluded that the general enhancing activity of IAS1 and DISE were functionally interchangeable.

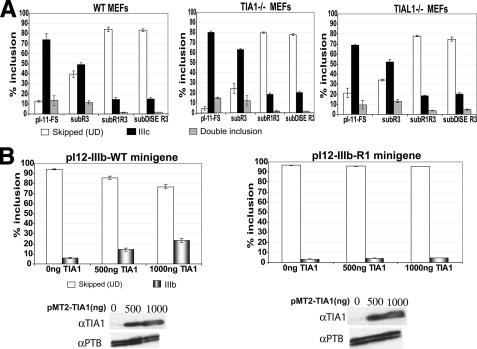

Human IAS1 has been proposed to act by binding the trans-acting factor TIA1 (T-cell-restricted intracellular antigen 1) (20) or the TIA1-like factor TIAL1 (also known as TIAR), which can substitute for TIA1 in some assays (21). Because IAS1 was able to substitute for DISE, we asked whether or not TIA1 (or TIAL1) was required for DISE action. To this end, we evaluated the action of DISE in MEFs derived from the WT, TIA1-/-, and TIAL1-/- mice (Fig. 6A). The double knockouts are embryonic lethal, and no MEFs are available. Levels of IIIc inclusion comparable to the WT were observed when the pI-11-FS construct was stably transfected in either TIA1-/- MEFs or the TIAL1-/- MEFs. This suggested that neither TIA1 nor TIAL1 are essential for the inclusion of FGFR2 exon IIIc. Because there is a compensatory overproduction of TIAL1 in the TIA1-/- MEFs (and vice versa) and also because both these trans factors are known to have redundant targets (21), we decided to perform siRNA knockdowns of these proteins, both individually and in combination. For this we chose HeLa cells that include the FGFR2 exon IIIc. Even upon robust knockdowns of TIA1 and TIAL1, both individually and in combination, no significant effect on the inclusion of FGFR2 exon IIIc was observed (data not shown). This suggested to us that unlike the IAS1 enhancer, the intronic element DISE does not require TIA1 or TIAL1 for its activity, and hence it acts via a different trans-acting factor. To further test this hypothesis, we asked whether the TIA1 overexpression affected the action of IAS1 and DISE, differentially. These experiments were performed in HEK293 cells, which include exon IIIc and repress exon IIIb. We transfected these cells with the pI12-IIIb-WT, minigene that reports on the inclusion of exon IIIb and had been used earlier in one of our experiments (Fig. 5). A dose-dependent increase in the inclusion of exon IIIb in HEK293 cells was observed with increasing amounts of TIA1 expression (Fig. 6B). This dose-dependent increase in IIIb inclusion upon TIA1 overexpression was abolished when IAS1 was replaced by R1 (minigene pI12-IIIb-R1)). Similar results were also obtained when TIAL1 was overexpressed in HEK293 cells (data not shown). These data suggest that DISE exerts its effect on the upstream exon by a mechanism that does not involve TIA1 and TIAL1 and that is therefore distinct from that employed by IAS1. The results of this experiment provide an independent confirmation of our hypothesis that IAS1 and DISE intronic elements act via different trans-acting factors.

FIGURE 6.

DISE does not require TIA1 or TIAL1. A, quantification of the transfections performed in WT MEFs, TIA1-/- MEFs, and TIAL1-/-MEFs. The % inclusion for exon IIIc from the indicated reporter transcripts was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD), IIIc (UIIIcD), and double inclusion (UIIIbIIIcD) products. B, % inclusion of exon IIIb with the pI12-IIIb-WT and pI12-IIIb-R1 minigene transcripts in HEK293 cells. The schematics for pI12-IIIb-WT and pI12-IIIb-R1 minigenes have been shown in Fig. 5A. Exon IIIb inclusion was calculated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.D. of triplicate transfections. The legend indicates the skipped (UD) and single inclusion IIIb (UIIIbD) products. The Western blots of the TIA1 overexpression are shown. PTB was used as the loading control.

DISE Is Functional in Human Cells—Given the extensive conservation of the R1 region between rats and humans, we speculated that DISE would be functional in human cells. To confirm that the DISE element that we had identified in rat cells was also essential for the inclusion of the rat exon IIIc in human cells, we decided to test the DISE activity in HEK293 cells. We did this using fluorescence-based reporters, which have been shown by our laboratory to be surrogates for exon IIIc inclusion (12). HEK293 cells, transfected with a control pRint minigene, which contains the open-reading frame of DsRed dimer variant of RFP (22) bifurcated by a constitutive intron, produce high levels of RFP (Fig. 7). On the other hand, transfection with the pRIIIcI2 reporter that contains exon IIIc and parts of its flanking introns produced low levels of RFP in HEK293 (Fig. 7). This result is consistent with the observation that HEK293 cells include exon IIIc efficiently, and this inclusion interrupts the RFP open-reading frame (Fig. 7). Transfection with the pRIIIcI2subDISE minigene, which is identical to pRIIIcI2 except that the 24 nt that form DISE have been substituted as described above (Fig. 3C), led to high levels of RFP expression (Fig. 7). This increase could be completely explained by the marked reduction in inclusion of exon IIIc observed using RT-PCR (data not shown). These data show that DISE was active in human cells, and its activity could be measured using different reporter transcripts and methodologies.

FIGURE 7.

A fluorescence-based reporter system can detect DISE function in human kidney cells. Schematic of the fluorescence (RFP)-based splicing reporters, pRint, pRIIIcI2, and pRIIIcI2subDISE, is shown on the left (constructs), with corresponding fluorescent (RFP) and white light (Phase) images.

DISE Enhances Exon Inclusion in a Heterologous System by Acting Directly on Splicing—Because some splicing regulatory elements impart their action by affecting transcription, we asked whether DISE action requires transcriptional coupling (23). We showed that DISE was active in HeLa cells (data not shown), and thus we used nuclear extracts from HeLa cells to carry out in vitro splicing reactions. We utilized the constitutively spliced human β-globin gene in these experiments. We substituted 45 nucleotides of β-globin intron 2 with either the R1 region of FGFR2(β-globin-R1) or a matched size control in which R1 was mutated using the same transversions as described in Fig. 3A, which were now introduced in tandem, (β-globin-R1mut) (Fig. 8A). The splicing efficiency of partially spliced β-globin exons 1 and 2 and of the fully spliced product, exons 1, 2, and 3 were measured (see “Experimental Procedures”). At 60 min, we observed a DISE enhancer effect on the formation of both spliced products (Fig. 8, B and C). In in vitro transcription splicing-coupled reactions DISE activation was no stronger than that observed in the conventional splicing reactions (data not shown). We concluded that DISE action does not require transcriptional coupling, and DISE exerted its action directly on the splicing reaction.

DISE Enhances Splicing via Increased Binding of U1 snRNA—Our previous experiments demonstrated that DISE needs to be present near the 5′-splice site to be able to exert its effect on enhancing exon inclusion and that it acts via a mechanism different from that of other FGFR2 intronic enhancer, IAS1 (Figs. 4 and 6, respectively). Because neither TIA1 nor its related factor TIAL1 were essential for the inclusion of FGFR2 exon IIIc, we wanted to investigate the mechanism by which DISE exerts its effect on exon inclusion.

We performed in vitro splicing reactions with single intron FGFR2 pre-spliced templates. These pre-spliced templates had only the FGFR2 intron 9, because the adenoviral U exon had been pre-spliced to the FGFR2 IIIc exon. In this experiment, transcripts in which the exon IIIc 5′-splice site sequence had been mutated to disrupt the invariant GU dinucleotide to a CC dinucleotide (lane 1, Fig. 9A) or mutated to create a 5′-splice site consensus sequence (lane 2) were used as a negative and positive controls, respectively. An enhanced formation of splicing intermediates spliced products was observed with transcripts that had WT-DISE (WT) compared with a matched size control that had a mutated DISE sequence (mut) (Fig. 9A).

We asked whether or not DISE enhanced splicing by facilitating U1snRNP binding to the 5′-splice site. Psoralen-mediated cross-linking experiments were performed using the above mentioned transcripts and HeLa nuclear extracts in either the presence or absence of AMT-Psoralen (Fig. 9B). Because of variable recovery of RNAs in this experiment, we normalized the level of a psoralen-dependent band to the level of pre-mRNA. When the U1 snRNA was depleted from the HeLa nuclear extracts, there was a significant decrease in the psoralen-dependent band, and therefore we assume that this represents a U1-pre-mRNA cross-link. Quantification of the level of this U1-pre-mRNA cross-linked band relative to levels of pre-mRNA indicated an enhanced efficiency of U1 snRNA cross-linking for WT-DISE transcripts compared with the DISE-mutated control (Fig. 9C). Together, these experiments argue that DISE affects FGFR2 exon IIIc inclusion by promoting U1 snRNP binding to an otherwise weak 5′-splice site.

DISCUSSION

Although identified almost 15 years ago (24), ISEs have not been subjected to the same extensive analysis as exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) (1, 2, 25). Hence our current understanding of ISEs and the mechanisms by which they exert their effects is still incomplete. In this article, we describe the identification and characterization of DISE, an intronic enhancer that activates exon IIIc in FGFR2 transcripts. This exon, which is included in mesenchyme, has been shown to be critical for normal development in mice and humans. Indeed a number of mutations that lead to skeletal abnormalities in patients with Crouzon/Pfeiffer/Jackson-Weiss group syndromes tend be clustered within exon IIIc and the intronic regions around it (26). Thus, it follows that DISE function must be critical for normal skeletal development.

Some ISEs act in a tissue-restricted manner (e.g. nova-dependent intronic enhancers) (27), while others act on constitutive exons (28). Both DISE and the ISE found downstream of FGFR2 exon IIIb (IAS1) (18) can function in both mesenchymal and epithelial cells, indicating that neither is sufficient for the cell type-specific inclusion of these exons. The fact that IAS1 can substitute for DISE and vice versa is consistent with this more general role (Fig. 5). The regulation of these exons, however, requires these two enhancers. In mesenchymal cells, IAS1 is countered by intronic and exonic splicing silencers and exon IIIb is not included (7, 9, 29, 30). Similarly, in epithelial cells, an ESS, which binds members of the Fox family of proteins, opposes the action of DISE, and exon IIIc is silenced (6).

ISEs appear to be quite versatile in terms of location within an intron and perhaps within a transcript. The U-rich ISEs, which interact with TIA1 and/or TIAL1 (e.g. IAS1) (31), and the G-rich ISEs, which are presumed to act via hnRNP H (32), are found immediately downstream of the 5′-splice sites. Nonetheless, Berget and co-workers (28) showed that the G-rich ISE found downstream of the cTNT microexon could activate a heterologous exon when placed either downstream or upstream. Nova-dependent enhancers are generally found either downstream of a Nova-activated exon or upstream of the subsequent constitutive exon (27). The action of these ISEs appears to be local, enhancing the intron that harbors the YCAY Nova sites (27). Recent findings suggest that some ESEs can include distal exons (33), and the mechanisms proposed for this phenomenon could easily apply to ISEs. Indeed, the cTNT ISE was shown to activate the splicing of the upstream intron (28). DISE appears to be an enhancer that acts locally. Nonetheless, we show that substitution of DISE led to a decrease in total exon IIIb inclusion (U-IIIb-IIIC-D + U-IIIb-D) (Fig. 1C). While this could be interpreted as a distal effect on exon IIIb inclusion, we believe that substitution of DISE affected double inclusion indirectly. The fact that DISE substitution increases skipping of both alternative exons (increased levels of U-D) and does not change the levels of U-IIIb-D suggests the existence of a DISE sensitive intermediate in the splicing pathway that can produce either double inclusion or skipped products. If exons IIIb and IIIc splice to each other first (U-intron-IIIb-IIIc-intron-D), this three exon intermediate could skip or include IIIb-IIIc. Thus we believe that DISE mediated its effect only on the exon immediately upstream. Indeed, this conclusion is consistent with the distance dependence we observed for exon IIIc activation (Fig. 4).

Whereas DISE and IAS1 are interchangeable and both act by recruiting U1 snRNP (Fig. 9 and Ref. 20), DISE does not act via either TIA1 or TIAL1. This suggests the existence of other trans-acting factors in the mesenchymal cells that act in a similar general manner to enhance the recognition of the weak 5′-splice site. The identification of these trans factors is currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul Anderson for the generous gift of MEFs and the TIA and TIAR overexpression plasmids. We also thank Joshua Lacsina for help in preparation of one the constructs used in this study. The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the Garcia-Blanco laboratory for helpful discussions. We also thank Caroline Le Sommer, David Mauger, and October Sessions for useful suggestions during the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM63090 (to M. A. G. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: FGFR2, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; RT, reverse transcriptase; ISE, intronic splicing enhancer; TIA1, T-cell restricted intracellular antigen 1; TIAL1, TIA1-like; PTB, polypyrimidine tract-binding protein; ESS, exonic splicing silencer; ESE, exonic splicing enhancer; mut, mutation; nt, nucleotides; WT, wild type; HEK, human embryonic kidney cells; MEF, murine embryonic fibroblasts; DISE, downstream intronic splicing enhancer; IAS1, intronic activator sequence 1; snRNA, small nuclear RNA.

M. A. Garcia-Blanco, unpublished results.

References

- 1.Black, D. L. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72 291-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Blanco, M. A., Baraniak, A. P., and Lasda, E. L. (2004) Nat. Biotechnol. 22 535-546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matlin, A. J., Clark, F., and Smith, C. W. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 386-398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miki, T., Bottaro, D. P., Fleming, T. P., Smith, C. L., Burgess, W. H., Chan, A. M., and Aaronson, S. A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 246-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dell, K. R., and Williams, L. T. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267 21225-21229 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baraniak, A. P., Chen, J. R., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 1209-1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carstens, R. P., Wagner, E. J., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 7388-7400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carstens, R. P., McKeehan, W. L., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 2205-2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner, E. J., Baraniak, A. P., Sessions, O. M., Mauger, D., Moskowitz, E., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 14017-14027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natalizio, B. J., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2005) Methods 37 314-322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonano, V., Oltean, S., Brazas, R., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2006) Rna 12 2073-2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oltean, S., Sorg, B. S., Albrecht, T., Bonano, V. I., Brazas, R. M., Dewhirst, M. W., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 14116-14121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baraniak, A. P., Lasda, E. L., Wagner, E. J., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 9327-9337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner, E. J., Carstens, R. P., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (1999) Electrophoresis 20 1082-1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merendino, L., Guth, S., Bilbao, D., Martinez, C., and Valcarcel, J. (1999) Nature 402 838-841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Gatto, F., and Breathnach, R. (1995) Genomics 27 558-559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mistry, N., Harrington, W., Lasda, E., Wagner, E. J., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2003) Rna 9 209-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Del Gatto, F., and Breathnach, R. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 4825-4834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Gatto, F., Plet, A., Gesnel, M. C., Fort, C., and Breathnach, R. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 5106-5116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Del Gatto-Konczak, F., Bourgeois, C. F., Le Guiner, C., Kister, L., Gesnel, M. C., Stevenin, J., and Breathnach, R. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 6287-6299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Guiner, C., Gesnel, M. C., and Breathnach, R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 10465-10476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell, R. E., Tour, O., Palmer, A. E., Steinbach, P. A., Baird, G. S., Zacharias, D. A., and Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 7877-7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstrohm, A. C., Greenleaf, A. L., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2001) Gene (Amst.) 277 31-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black, D. L. (1992) Cell 69 795-807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blencowe, B. J. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25 106-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oldridge, M., Zackai, E. H., McDonald-McGinn, D. M., Iseki, S., Morriss-Kay, G. M., Twigg, S. R., Johnson, D., Wall, S. A., Jiang, W., Theda, C., Jabs, E. W., and Wilkie, A. O. (1999) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64 446-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ule, J., Stefani, G., Mele, A., Ruggiu, M., Wang, X., Taneri, B., Gaasterland, T., Blencowe, B. J., and Darnell, R. B. (2006) Nature 30 580-586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlo, T., Sterner, D. A., and Berget, S. M. (1996) Rna 2 342-353 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Gatto, F., Gesnel, M. C., and Breathnach, R. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res. 24 2017-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner, E. J., and Garcia-Blanco, M. A. (2002) Mol Cell 10 943-949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Guiner, C., Lejeune, F., Galiana, D., Kister, L., Breathnach, R., Stevenin, J., and Del Gatto-Konczak, F. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 40638-40646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han, K., Yeo, G., An, P., Burge, C. B., and Grabowski, P. J. (2005) PLoS Biol. 3 e158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fededa, J. P., Petrillo, E., Gelfand, M. S., Neverov, A. D., Kadener, S., Nogues, G., Pelisch, F., Baralle, F. E., Muro, A. F., and Kornblihtt, A. R. (2005) Mol. Cell 19 393-404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.