Abstract

The function of tissue factor (Tf)-initiated coagulation is hemorrhage control through the formation and maintenance of an impermeable platelet-fibrin barrier. The catalytic processes involved in the clot maintenance function are not well defined, although the rebleeding problems characteristic of individuals with hemophilias A and B suggest a link between specific defects in the Tf-initiated process and defects in the maintenance function. We have previously demonstrated, using a methodology of “flow replacement” (or resupply) of ongoing Tf-initiated reactions with fresh reactants, that procoagulant complexes are produced during Tf-initiated coagulation, which are capable of reinitiating coagulation without input from extrinsic factor Xase activity (Orfeo, T., Butenas, S., Brummel-Ziedins, K. E., and Mann, K. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42887–42896). Here we used Tf-initiated reactions in normal and hemophilia blood or in their corresponding proteome mixtures as sources of procoagulant end products and then varied the resupplying material to determine the identity of the catalysts that drive the new cycle of thrombin formation. The central findings are as follows: 1) the prothrombinase complex (fVa-fXa-Ca2+-membrane) accumulated during the episode of Tf-initiated coagulation is the primary catalyst responsible for the observed pattern of prothrombin activation after resupply; 2) impairments in intrinsic factor Xase function, i.e. hemophilias A and B, result in an impaired capacity to mount a resupply response; and 3) in normal hemostasis the intrinsic factor Xase function contributes to the durability of the resupply response.

The extrinsic or tissue factor (Tf)2-initiated pathway is generally considered the essential pathway of hemorrhage control in vivo. In closed model systems used to study blood coagulation, this pathway is characterized by the successive emergence and overlapping expression of three procoagulant complexes. The first complex forms when pre-existent factor (f) VIIa binds to the membrane-bound protein Tf, forming the extrinsic fXase complex (Tf-fVIIa-Ca2+-membrane). Formation of the extrinsic fXase yields an ∼107-fold increase in enzymatic activity of fVIIa toward its substrates, fIX and fX (1). fXa produced by the extrinsic fXase directly activates amounts of prothrombin (fII) to thrombin (2) sufficient to activate a fraction of the pro-cofactor pools of fV and fVIII and to begin both the activation of platelets and the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin (3). These events establish the reaction conditions necessary for the emergence of the two catalytic complexes required for the amplified rates of thrombin formation that characterize an effective hemostatic response: the intrinsic fXase complex (fVIIIa-fIXa-Ca2+-membrane), a catalyst that is ∼50 times more efficient in converting fX to fXa than the extrinsic fXase (4, 5); and the prothrombinase complex (fVa-fXa-Ca2+-membrane), a catalyst of fII activation that is ∼105-fold more efficient than fXa (6). Over the course of the reaction, the intrinsic fXase produces the vast majority of the fXa found in the prothrombinase complex (7), whereas thrombin generated by the prothrombinase complex drives most of the platelet activation and fibrin formation. The interplay between the extrinsic and intrinsic fXase functions is highlighted in hemophilias A (fVIII deficiency) and B (fIX deficiency), life-threatening hemorrhagic disorders in which fXa generation, and thus ultimately prothrombinase levels, depend on the less efficient extrinsic fXase complex. Consequences of this reliance on the extrinsic fXase observed using in vitro models of hemophilia include impaired rates and maximum levels of thrombin formation (8–10), lower levels of prothrombinase (8), altered patterns of fibrin formation (10), and clot architecture (11). These results indicate that the extrinsic fXase complex cannot sustain normal hemostasis.

Although there is good consensus on the requirement for Tf in the initiation of coagulation and on the primary catalytic complexes that emerge in response to Tf, there is less agreement on the overall mechanism by which Tf functions in vivo. In one view of normal hemostasis, Tf is sequestered outside of blood vessels (12–15), requiring disruption of blood vessel integrity to exert its effects, and within circulating blood cells, requiring specific signaling events to promote its intravascular expression (16, 17). If a sufficient Tf challenge is presented, a full coagulant response follows; if the Tf challenge is insufficient, the procoagulant response is arrested, primarily by the activity of the stoichiometric inhibitor Tf pathway inhibitor (TFPI) (18). Contributing to this conceptual framework are several lines of evidence. 1) Reports from our laboratory and others have indicated that there is little or no Tf-related activity in the blood of healthy individuals (19–21) or in the blood of mice (22). 2) Quantitative assessments of quiescent or ionophore-activated treated platelets showed no detectable Tf activity or antigen and no available Tf on unstimulated mononuclear cells in blood (19). 3) In several in vitro models of Tf-initiated coagulation, the procoagulant response becomes independent of Tf cofactor activity prior to the onset of clot formation (23), suggesting that transient expression of Tf is sufficient to achieve successful hemorrhage control. 4) Numerous studies have implicated fibrin-bound thrombin as a relatively stable, localized, procoagulant product of Tf-initiated coagulation, capable of activating procofactors, cleaving fibrinogen, and activating platelets and thus functioning to propagate thrombus growth (24–31).

In contrast, however, a number of reports have suggested that measurable levels of Tf proteins are constitutively present in blood, either localized on the surface of blood cells or microparticles (32–40) and/or present as a soluble variant (41). Platelet Tf pools have also been suggested (37, 42–45) with Panes et al. (46) recently reporting that activation of platelets leads to de novo synthesis of Tf and its expression. Collectively, these data have been rationalized by advancing a competing hypothesis of overall Tf biology in which the initiating Tf stimulus requires constant supplementation of the ongoing reaction with newly arrived Tf. This hypothesis depends on three interdependent concepts. 1) The developing platelet/fibrin plug isolates the procoagulant complexes initially formed at the site of vascular injury from further supply of fresh reactants, thus eliminating participation of the triggering Tf supply as the reaction proceeds (47). 2) Tf is present in blood at levels below the threshold to support a coagulant response (48) or in some cryptic state, but it accumulates to an effective level on the vascular face of a forming thrombus (39, 41, 46). 3) The maintenance of the coagulation process requires a continual contribution from Tf cofactor activity (extrinsic fXase complex).

Previous work from our laboratory and others (24, 25, 27–30) led us to propose a model of hemorrhage control (23) in which two procoagulant compartments emerge as a consequence of the impermeable barrier formed by platelets and fibrin as follows: an extravascular one, isolated from the blood, with quiescent (reactant-starved) procoagulant catalysts that can respond immediately if the barrier fails; and a vascular side where the accumulated ensemble of procoagulant catalysts, exposed to flowing blood, continues the process of clot growth. On this side, however, these catalysts are exposed to the active anticoagulant properties of the vasculature that eventually neutralize them, rendering the vascular face of the clot inert. Thus, in this model, hemorrhage control involves not only the formation of an effective barrier and appropriate control of clot growth on the vascular side but also involves the presence of a persisting, Tf-independent procoagulant potential on the extravascular side. Potential candidates for this procoagulant aftermath include clot-bound thrombin (24, 29, 30) and/or the prothrombinase complex (23). This construct led us to suggest that the tendency of hemophiliacs to bleed in part reflected the failure to sufficiently populate the extravascular compartment of the formed clot with these procoagulant catalysts.

Here we report studies in closed model systems of normal and hemophilia coagulation that define the key components that constitute the reservoir of procoagulant activity remaining after an episode of Tf-initiated coagulation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—FVII, fX, fIX, and fII were isolated from fresh frozen human plasma using the methods of Bajaj et al. (49), and were purged of trace contaminants and traces of active enzymes as described (18). Human fV and antithrombin (AT) were isolated from freshly frozen plasma (50, 51), and human fVa was made as described (52). Human α-thrombin was prepared as described (53). Recombinant fVIII and recombinant Tf (residues 1–242) were provided as gifts from Drs. Shu Len Liu and Roger Lundblad (Hyland Division, Baxter Healthcare Corp., Duarte, CA). Recombinant human fVIIa was provided as a gift from Dr. Ula Hedner (Novo Nordisk, Denmark). Recombinant full-length TFPI was provided as a gift from Dr. S. Hardy (Chiron Corp., Emeryville, CA). Human fXa was prepared as described previously (54). Corn trypsin inhibitor (CTI) was isolated from popcorn (8, 55), and the preparation of the Tf/lipid reagent was performed as described elsewhere (8). 1,2-Dioleolyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (PS) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL), and EDTA was purchased from Sigma. Phospholipid vesicles (PCPS) composed of 75% PC and 25% PS were prepared as described (56). Spectrozyme TH was purchased from American Diagnostica, Inc. (Greenwich, CT). d-Phe-Pro-ArgCH2Cl (FPRck) was prepared in house. Monoclonal anti-fIX (α-fIX-91) and anti-fX (α-bfX-2b) antibodies were obtained from the Biochemistry Antibody Core Laboratory (University of Vermont), as was the polyclonal burro anti-human prethrombin 1 antibody. Benzenesulfonyl-d-Arg-Gly-Arg-ketothiazole (C921-78) was provided as a gift by Dr. U. Sinha (Portola Pharmaceuticals Inc., South San Francisco, CA). Dansylarginine-N-[3-ethyl-1,5-pentanediyl]amide (DAPA) was purchased from Hematologic Technologies Inc. (Essex Junction, VT). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay thrombin-AT (TAT) kit (Enzygnost TAT) was purchased from Behring (Marburg, Germany).

Whole Blood Model—The protocol used is a modification (23) of Rand et al. (57). Healthy control individuals and one hemophilia A individual were recruited and advised according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Vermont Human Studies Committee. Informed written consent was obtained from all individuals. The healthy individuals selected exhibited normal values for the parameters of blood coagulation, protein levels, and platelet counts. The hemophilia A donor was a young man, 27 years old, who has functionally severe fVIII deficiency (fVIII:C < 1%). He tested positive for hepatitis C and has a history of bleeding and joint pain and routinely self-administered recombinant fVIII products when symptomatic. His blood was drawn 5 days after the most recent fVIII injection. His fVIII level on the day of the experiment was 1%.

Blood was drawn by venipuncture and immediately delivered into reagent-loaded tubes. The equivalent of acquired hemophilia B was induced by including the inhibitory monoclonal antibody α-fIX-91 in the tubes as described previously (10, 58). At 50 μg/ml, α-fIX-91 prolonged the activated partial thromboplastin time of normal plasma from 38 to 115 s. The activated partial thromboplastin time for commercial factor IX-deficient plasma (<1% of factor IX; George King Biomedical, Overland Park, KS) was 112 s. In general, 2 sets of aliquots of CTI-treated blood were initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent. One set was quenched at 1-min intervals, whereas the other was incubated for 20 min. At 20 min this set of unquenched aliquots, which in CTI-blood all showed visible clots at ∼4 min, was resupplied with an equal volume of freshly drawn blood containing CTI alone (0.1 mg/ml) or in “acquired hemophilia B” experiments with CTI (0.1 mg/ml) + α-fIX-91 (0.1 mg/ml) or CTI (0.1 mg/ml) + 320 nm C921-78. Alternatively, resupply experiments were conducted with the addition of an equal volume of a solution containing CTI (0.1 mg/ml), AT (3.4 μm), and fII (1.4 μm) (fII/AT/CTI) in 20 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl at pH 7.4 (HBS) + 2 mm CaCl2 ± α-fIX-91 (0.1 mg/ml). Resupplied tubes were then successively quenched at 1-min intervals. TAT levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and fibrinopeptide A (FPA) levels as described previously (59). In all cases, CTI-treated phlebotomy blood in the absence of added Tf reagent did not clot for at least 23 min. Previous investigations have detailed the progress of Tf-initiated reactions in CTI-treated blood (3, 23, 57, 59).

Synthetic Coagulation Proteome Model—The procedure used is a modification of Lawson et al. (60) and van't Veer and Mann (18). Platelets were prepared by the method of Mustard et al. (61). Relipidated Tf at 5 pm final concentration was added to a mixture of fII, fV, fVII, fVIIa, fVIII, fIX, fX, fXI, TFPI, and AT (all at mean physiologic concentrations) (62) in HBS with 2 mm CaCl2 containing 2 μm PCPS or 2 × 108 platelets/ml. In the acquired hemophilia B format, α-fIX-91 (0.1 mg/ml) was included. Resupply was conducted at 20 min post-initiation (23) or at longer intervals by the addition of an equal volume of a freshly constituted, Tf-free mixture containing procofactors, zymogens, and inhibitors in HBS + 2 mm CaCl2 containing 2 μm PCPS to an ongoing reaction. Alternatively, resupply was conducted with an equal volume of a solution containing 1.4 μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, and 2 μm PCPS (fII/AT/PCPS) ± 0.7 nm fVIII in HBS and 2 mm CaCl2. In the acquired hemophilia B format, α-fIX-91 was included in the resupply mixture. Thrombin generation over time was measured in a chromogenic assay using Spectrozyme TH and a THERMOmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Menlo Park, CA).

Inhibition of the Resupply Response in the Synthetic Coagulation Proteome—Two inhibitory antibodies, α-bfX-2b (63) and α-fIX-91 (10, 58), were evaluated. α-bfX-2b blocks the activity of human fXa in the prothrombinase complex toward fII but not the assembly of the prothrombinase complex. α-fIX-91 inhibits the rate of fX activation by preformed intrinsic fXase complex by ∼80% when present at 100 μg/ml and by ∼90% when present at 200 μg/ml.3 With either antibody, a 30-s incubation was sufficient to achieve a maximal level of suppression. Antibodies were added to ongoing Tf-initiated reactions after 18 min, with resupply conducted 2 min later using an equal volume the Tf-free, procofactor/zymogen/inhibitor mixture without additional antibody. C921-78 has been reported to specifically and reversibly inhibit fXa and fXa when associated with fVa on membranes (prothrombinase) (64) with a KD for fXa of ∼14 pm and for fXa in prothrombinase of ∼22 pm. DAPA is a reversible, active site directed inhibitor of thrombin and meizothrombin, with a KD of 20–40 nm (65, 66). Resupply experiments evaluating these inhibitors were conducted by including them into the resupply mixtures.

Measuring Prothrombinase Levels and Stability in Synthetic Coagulation Proteome Reactions—Synthetic coagulation proteome mixtures at 37 °C containing either 2 μm PCPS or 2 × 108 platelets/ml and initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent were assessed for the level of prothrombinase activity present at 20 min, the normal resupply time, and at selected longer intervals post-initiation. Prothrombinase levels were measured using a DAPA-based methodology (65). Aliquots of the synthetic coagulation proteome reaction mixture were diluted 300–1000-fold into a solution containing 2 μm PCPS, 20 nm fVa, 1.4 μm fII, and 3 μm DAPA in HBS + 2 mm CaCl2. PCPS and fVa concentrations present in the synthetic coagulation proteome reaction at 20 min are maintained in this assay to avoid dilution-driven disassociation of the prothrombinase complex present in the reaction aliquot. Initial rates of increase in DAPA fluorescence because of formation of meizothrombin and thrombin from prothrombin were translated into prothrombinase concentrations by reference to a standard curve constructed by varying the fXa concentration from 1 to 10 pm in the presence of 2 μm PCPS, 20 nm fVa, 1.4 μm fII, and 3 μm DAPA in HBS + 2 mm CaCl2.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blotting—Resupply time course samples were quenched into an equal volume of 50 mm EDTA, 50 μm FPRck in HBS, and 4-μl aliquots (potentially containing 100 ng fII) were made 2% in SDS and 2% in β-mercaptoethanol and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (67). Protein species were separated on 4–12% linear gradient gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) as described previously (18). FII and its activation products were probed for using a polyclonal burro anti-human prethrombin 1 antibody. Reactive bands were detected using goat anti-equine horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL) with a chemiluminescence reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and Kodak X-OMat film.

RESULTS

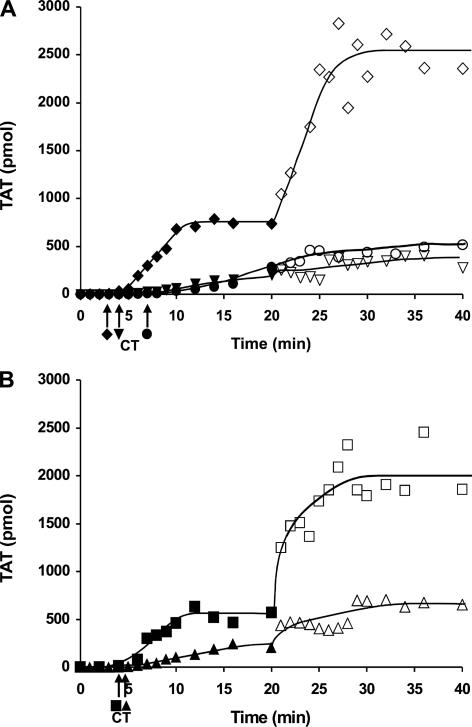

Resupply of Tf-initiated Reactions in Contact Pathway Inhibited Blood—Fig. 1 presents a series of resupply experiments in contact pathway inhibited phlebotomy blood (CTI-treated blood) probing the mechanism of the resupply effect. We have previously shown (23), using inhibitory antibodies against Tf and fVIIa, that the observed prothrombin activation following resupply is independent of the Tf-fVIIa complex. Fig. 1, panel A, shows representative control time courses of TAT formation for CTI-treated blood from a healthy individual after initiation with 5 pm Tf reagent and after resupply of the ongoing reaction. Consistent with our earlier report (23), the resupply response here is characterized by the absence of a lag phase in the resumption of thrombin formation with an increased rate of TAT formation (∼3-fold) relative to that observed as a consequence of Tf initiation. Western blot analysis (not shown) of the Tf-initiated and resupply time courses indicated that prothrombin consumption was complete between 10 and 15 min after Tf initiation and in less than 10 min after resupply. Fig. 1, panel B, presents an experiment in which CTI-treated blood from a different healthy individual was initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent and then resupplied at 20 min with an equal volume of a solution containing only fII/AT/CTI. The resupply mixture was designed to define the magnitude of the contribution to the resupply response of the clot incorporated prothrombinase complex produced during the initial 20 min. Resupply with only the fII/AT/CTI solution resulted in a time course of TAT formation that displayed the two key features of resupply with blood as follows: the absence of a lag phase and an increased maximum rate of fII activation (∼4-fold) relative to that observed in response to Tf. Consistent with this pattern of increased reactivity, Western blot analysis (not shown) of the fII/AT/CTI resupply time course showed that fII consumption was nearly complete by 10 min, compared with ∼16 min in this case for the Tf-initiated CTI-treated blood. These results suggest that the prothrombinase complex formed during the initial process of Tf-initiated coagulation is the primary contributor to the resupply response. They indicate that Tf-dependent processes were not necessary to restart a coagulant response in clotted blood, consistent with our previous report (23). In addition they indicate that renewed thrombin generation upon resupply could be initiated without contributions from clot-bound thrombin.

FIGURE 1.

Resupply of contact pathway inhibited blood. Time courses of TAT formation in response to the addition of 5 pm Tf reagent to CTI-treated phlebotomy blood are shown (closed symbols), along with time courses of TAT formation in response to resupply at 20 min (open symbols). Panel A, Tf-initiated CTI-blood from a healthy individual (♦) resupplied with an equal volume of freshly drawn blood from the same individual (⋄); Tf-initiated acquired hemophilia B blood (•) (CTI-treated blood to which 0.1 mg/ml α-fIX-91 was added) resupplied with acquired hemophilia B blood (○); Tf-initiated blood from an individual with severe hemophilia A (1% fVIII) (▾) resupplied with freshly drawn CTI-treated blood from the same individual (▿). Panel B, Tf-initiated blood from a healthy individual (▪) resupplied with an equal volume of a mixture containing only 1.4 μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, and 0.1 mg/ml CTI (□); Tf-initiated acquired hemophilia B blood (▴) resupplied with an equal volume of a mixture containing only 1.4 μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, 0.1 mg/ml CTI, and 100 μg/ml α-fIX-91 (▵). CT, clot time. TAT levels at each time are expressed as total picomoles to normalize for the volume change.

Prothombinase levels in CTI-blood can be estimated from rates of TAT formation (8, 57); extrapolations from initial rates of TAT formation upon resupply with CTI-blood indicate that prothrombinase levels at the point of resupply range from 100 to 250 pm (three different donors). Estimates of prothrombinase levels from resupply experiments conducted with fII/AT/CTI were similar. This approach potentially underestimates the concentration of prothrombinase because it assumes equivalence between the rate of fII consumption and the rate of TAT formation. Computational modeling of the resupply response (23) suggests that the rate of TAT formation is about ∼40% the rate of fII consumption over the 1st min of resupply, suggesting that prothrombinase levels may be ∼2.5-fold higher (250–600 pm) than initially calculated.

To explore the importance of the intrinsic fXase complex to the emergence and function of the catalysts required for the resupply response, a series of experiments was conducted with hemophilia blood. Fig. 1, panel A, also shows an experiment in which CTI-treated blood from a healthy individual was supplemented with α-fIX-91 to generate acquired hemophilia B blood (10, 58). The addition of 5 pm Tf reagent to this blood and then resupply at 20 min with a fresh batch of acquired hemophilia B blood was then carried out and TAT formation measured. As reported previously for this model system for hemophilia blood, the major effect on the Tf-initiated process is the absence of the propagation phase of thrombin generation (10, 58). In this instance, the immediate rate of TAT formation observed post clot time in acquired hemophilia B blood was ∼1/9th that observed with phlebotomy blood from a healthy individual not treated with α-fIX-91. When resupplied at 20 min, acquired hemophilia B blood did not display a burst in fII consumption. Over the first 5 min post-resupply, the rate of TAT formation appeared to be unaltered from that observed at the end of the Tf-initiated phase and then appeared to decrease slightly over the following 15 min. Time courses of TAT formation for CTI-treated phlebotomy blood from an individual with severe hemophilia A (1% fVIII) in response to Tf initiation (Fig. 1, panel A) and subsequent resupply after 20 min are also shown in Fig 1, panel A. fVIII deficiency yielded impaired rates of TAT formation in response to the Tf stimulus, consistent with a previous report (8), and an attenuated resupply response characterized by little or no change in the rate of TAT formation relative to the Tf-initiated process.

Fig. 1, panel B, shows a complementary experiment in which acquired hemophilia B blood produced from a different healthy donor was initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent and then resupplied with a solution containing fII/AT/CTI + 0.1 mg/ml α-fIX-91. A slight increase in the rate of TAT formation upon resupply was observed, but overall TAT formation remains attenuated. Western blot analyses indicated that fII consumption was incomplete in both the Tf-initiated and resupply reactions (not shown).

The observation that both fVIII deficiency and induced functional fIX deficiency lead to an impaired resupply response suggests that fXa produced by the extrinsic fXase alone cannot support the formation of the ensemble of catalysts required for the resupply response. Prothrombinase levels at the point of resupply in CTI hemophilia blood were 4–8% of those observed with normal CTI-blood. In a previous study, the maximum prothrombinase levels in Tf-initiated hemophilia A blood were estimated to be less than 5% of the levels observed in normal blood (8).

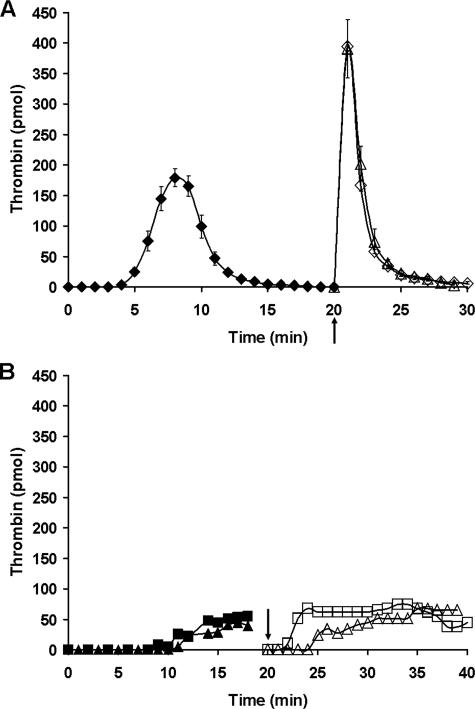

Resupply of Tf-initiated Synthetic Coagulation Proteome Mixtures—To further explore the catalytic requirements underlying the resupply response, experiments were conducted using the synthetic coagulation proteome. Fig. 2, panel A, presents a compilation of proteome experiments using PCPS membranes that compare thrombin generation for resupply conducted with either the complete proteome mixture or a mixture containing only fII/AT/PCPS. Consistent with the resupply response observed in CTI-treated blood, the time courses of thrombin generation produced by the different resupply mixtures showed substantial overlap. Western blot analysis (not shown) indicated that fII consumption was complete at ∼1 min after resupply with either resupply mixture. Fig. 2, panel B, presents time courses of thrombin formation for acquired hemophilia B proteome mixtures. Incorporation of α-fIX-91 at 0.1 or 0.2 mg/ml into the reaction mixture prior to Tf initiation resulted in a delayed onset of thrombin production, with an ∼10-fold reduction in the maximum rate of that process when compared with uninhibited reactions. Resupply of these acquired hemophilia B proteome reactions at 20 min with proteome mixtures containing either 0.1 or 0.2 mg/ml α-fIX-91 showed a delay in the onset of thrombin formation followed by the establishment of a steady state level of thrombin representing 10–15% of the maximum thrombin level observed in the control resupply (Fig. 2, panel A). The maintenance of a relatively low but constant level of thrombin in both Tf-initiated and resupply acquired hemophilia B proteome reactions is consistent with the slow accumulation of TAT observed in the CTI-treated blood hemophilia models (e.g. Fig. 1, panel A). When the acquired hemophilia B proteome reactions (Tf-initiated or resupply) are followed beyond 20 min, thrombin levels decline and eventually become undetectable, reflecting the depletion of fII and the ongoing inhibition of residual thrombin by AT. In general, the acquired hemophilia B proteome mixture recapitulates the dynamic features of the resupply response observed in hemophilia blood.

FIGURE 2.

Resupply of the synthetic coagulation proteome. Panel A, average time courses of thrombin generation are presented for reactions initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent (♦, n = 4) and for those then resupplied after 20 min with either an equal volume of starting material (complete synthetic coagulation proteome mixture + 2 μm PCPS but no Tf (⋄), n = 12) or an equal volume of a mixture containing only 1.4 μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, 2 μm PCPS (▵), n = 3. Data are mean ± S.D. for indicated number of experiments. Panel B, time courses of thrombin formation are presented for “acquired hemophilia” synthetic coagulation proteome mixtures that have been initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent: 0.1 mg/ml α-fIX-91 (▪); 0.2 mg/ml α-fIX-91 (▴). Resupply of each ongoing reaction after 20 min was conducted with an equal volume of starting material without Tf containing either 0.1 mg/ml (□) or 0.2 mg/ml, respectively (▵), α-fIX-91. Thrombin levels at each time are expressed as total picomoles of active thrombin to normalize for the volume change. Arrows indicate the resupply time.

Catalysts Contributing to the Resupply Response in the Synthetic Coagulation Proteome—A series of experiments were conducted probing the catalytic requirements of the resupply response by testing the ability of inhibitors directed against fIXa, fXa, and thrombin to suppress thrombin formation during resupply. Proteome mixtures were initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent in the absence of inhibitors, whereas the resupply reactions were conducted in the presence of the inhibitors.

Fig. 3 shows an experiment in which the inhibitory antibody α-fIX-91 was added to ongoing reactions 18 min after Tf initiation, with resupply conducted 2 min later. Shown are time courses for control resupply and resupplies conducted after the 2-min preincubation of the reacting proteome with 0.1 mg/ml or 0.2 mg/ml α-fIX-91. No effect on thrombin generation was observed, indicating that intrinsic fXase activity was not required to achieve the burst of thrombin production observed upon resupply.

FIGURE 3.

Resupply of the synthetic coagulation proteome: the effect of an inhibitory α-fIX antibody. Time courses of thrombin formation are presented for synthetic coagulation proteome mixtures that have been initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent (♦) and then resupplied after 20 min with an equal volume of synthetic coagulation proteome, 2 μm PCPS without Tf. Shown are normal resupply control (⋄), resupply after 0.1 mg/ml (□) or 0.2 mg/ml (▵) α-fIX-91 was added 2 min prior to resupply (see arrow). Thrombin levels at each time are expressed as total picomoles of active thrombin to normalize for the volume change.

Fig. 4 presents a similar experiment in which α-bfX-2, an antibody capable of blocking prothrombin activation by prothrombinase (63), was added to ongoing Tf-initiated reactions 2 min prior to resupply. Shown are time courses for control resupply, resupply after the 2-min preincubation with 0.1 mg/ml α-bfX-2, and resupply with only fII/AT/PCPS after the 2-min preincubation with 0.1 mg/ml α-bfX-2. The presence of α-bfX-2 delayed the onset of thrombin generation and suppressed the maximum level of thrombin, with the inhibition more pronounced when the resupply was conducted with the partial mixture. Also shown is the time course of thrombin generation after resupply with a proteome mixture containing the active site-directed, reversible fXa inhibitor C921-78. In the presence of 160 nm C921-78, the onset of thrombin generation was delayed 11 min, with maximum levels of thrombin reaching only ∼7% of the control resupply.

FIGURE 4.

Resupply of the synthetic coagulation proteome: the effect of inhibitors targeting fXa and fXa in the prothrombinase complex. Time courses of thrombin generation are presented for reactions initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent (♦) and then resupplied at 20 min with an equal volume of synthetic coagulation proteome, 2 μm PCPS without Tf: control resupply (⋄); 320 nm C921-78 included in the synthetic coagulation proteome, 2 μm PCPS resupply mixture (○); 0.1 mg/ml α-bfX-2 added 2 min prior to resupply with synthetic coagulation proteome, 2 μm PCPS (□); and 0.1 mg/ml α-bfX-2 added 2 min prior to resupply with 1.4 μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, 2 μm PCPS (▵). The arrow indicates the time of α-bfX-2 addition. Thrombin generation over the initial 20 min is presented as the mean ± S.D. of four determinations. Thrombin levels at each time are expressed as total moles of active thrombin to normalize for the volume change.

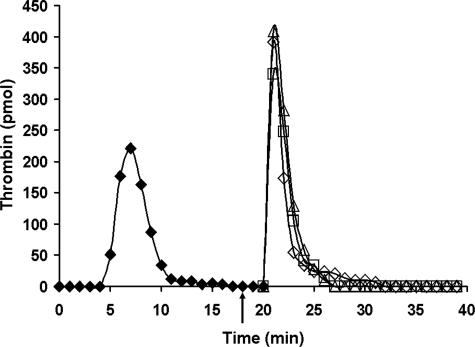

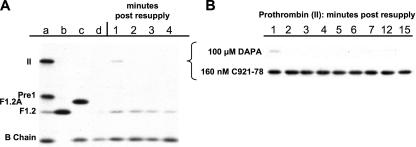

Fig. 5 presents an experiment in which the ability of the reversible thrombin inhibitor DAPA to block the resupply response was assessed and compared with that of C921-78. Resupply time course samples were analyzed by Western blotting to follow fII consumption, thereby distinguishing blockade of the resupply response by DAPA from the expected direct inhibition of newly produced α-thrombin. Fig. 5, panel A, presents an immunoblot showing the first 4 min of the control resupply reaction. Fig. 5, panel A, lanes a–c, displays the relative mobility of fII, reaction intermediates (F1.2A, pre-1), and end products (F1.2, B chain). Fig. 5, panel A, lane d, represents the 20-min time point, which was sampled immediately prior to resupply. It shows the expected absence of prothrombin. Because the primary antibody used has reduced reactivity toward thrombin when complexed with AT (TAT), this major product species is not detected by this analysis. In the absence of inhibitors, prothrombin consumption is greater than 95% complete at 1-min post-resupply, with the increase in the B chain reflecting the presence of active thrombin immediately after resupply (e.g. see Fig 2, panel A).

FIGURE 5.

Resupply of the synthetic coagulation proteome: the effect of a reversible thrombin inhibitor. Western blot analyses comparing the effects of a reversible thrombin inhibitor and a reversible inhibitor of fXa on prothrombin activation. Synthetic coagulation proteome mixtures initiated with 5 pm Tf reagent were resupplied at 20 min with an equal volume of synthetic coagulation proteome, 2 μm PCPS/without Tf ± inhibitors and then sampled at 1-min intervals for analysis by immunoblotting using a polyclonal burro anti-human prethrombin 1 antibody. Panel A, control resupply (no inhibitor). Lanes a–c, standards including II, prothrombin (Mr = 72,000); pre1, prethrombin1(Mr = 50,000; residues 156–579); F1.2A (Mr = 47,000; residues 1–320); F1.2 (Mr = 40,000; residues 1–271); B chain, α-thrombin B chain (Mr = 30,000; residues 321–579). Lane d is the 20-min sample taken immediately prior to resupply. Lanes 1–4, time points post-resupply. Panel B, composite Western blot showing only the time course of prothrombin antigen levels after resupply in the presence of each inhibitor. Prothrombin levels are shown for the first 15 min after resupply with proteome mixtures containing either DAPA (100 μm final) or C921-78 (160 nm final).

Fig. 5, panel B, is a composite of two immunoblots that analyzed resupply time courses when the resupplies were conducted with proteome mixtures containing either DAPA or C921-78. It presents only the lanes displaying fII for the first 15 min after resupply. C921-78 (160 nm final) proved effective in blocking prothrombin activation; densitometric analysis indicated that blockade by C921-78 allowed at most ∼10% prothrombin consumption over 15 min. In contrast, the presence of 100 μm DAPA did not appear to achieve any detectable suppression of fII consumption during resupply. This concentration of DAPA (∼5000 × Ki for α-thrombin) suppressed prothrombin consumption by greater than 98% when present at the onset of the Tf-initiated reaction (data not shown), presumably by blocking the initial thrombin-dependent activation of fV and fVIII (2, 68).

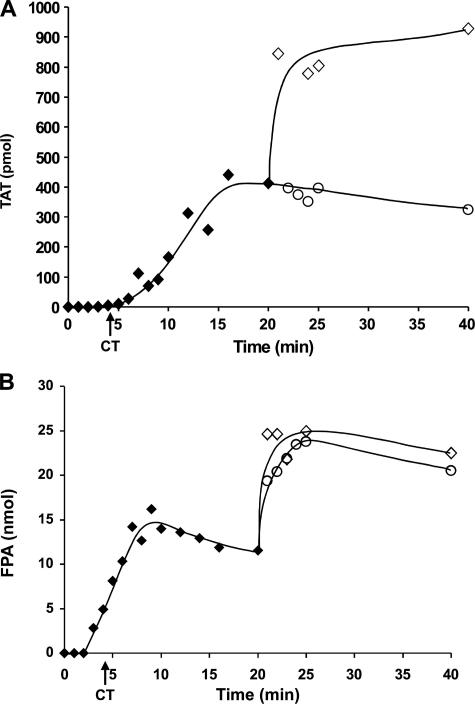

Inhibition of the Resupply Response in Contact Pathway Inhibited Blood—Fig. 6 presents a representative experiment in which ongoing Tf-initiated reactions in CTI-treated blood were resupplied at 20 min with CTI-treated blood or CTI-treated blood containing C921-78 (160 nm final). TAT (Fig. 6, panel A) and FPA, an initial product of α-thrombin cleavage of fibrinogen (69, 70) (Fig. 6, panel B), levels were measured at each time point. Consistent with previous reports on FPA formation in Tf-initiated, CTI-treated blood (57, 59), significant FPA generation (40–50%) is observed prior to clot time, with peak FPA levels achieved prior to 20 min and then declining slightly as a result of proteolysis.

FIGURE 6.

Resupply of contact pathway inhibited blood: the effect of an inhibitor targeting fXa and fXa in the prothrombinase complex. Time courses of TAT formation (panel A) and FPA release (panel B) after the addition of 5 pm Tf reagent to CTI-treated blood are shown (♦) as are resupply time courses of TAT (panel A) and FPA (panel B) formation for CTI-treated blood (⋄) and CTI-treated blood + C921-78 (160 nm final) (○). Analyte levels are expressed as the total picomoles of TAT or FPA versus time to normalize for volume change. CT = clot time.

The presence of C921-78 in the resupply blood effectively suppressed new formation of TAT; Western blot analysis confirmed that prothrombin consumption was minimal (<10% at 20 min post-resupply; data not shown). Suppression of prothrombin consumption and TAT production by C921-78 is consistent with the prothrombinase complex being the primary catalyst driving the resupply response, as predicted both from studies using the synthetic coagulation proteome and studies in which Tf-initiated CTI-blood was resupplied with the fII/AT/CTI mixture.

FPA release (Fig. 6, panel B) upon resupply with CTI-blood reached maximum levels within the 1st min, with greater than 90% of the potential pool of FPA released, indicating near quantitative conversion of the new supply of fibrinogen to fibrin 1. When the resupply blood contained C921-78, FPA release over the 1st min was somewhat attenuated, reaching ∼70% the level observed in the absence of C921-78.

The release of FPA coincident with resupply with CTI-blood containing C921-78 implies the presence of α-thrombin as the new supply of blood is mixed with the clotted blood. We have previously shown using a fibrinogen cleavage assay that the concentration of active thrombin in sera prepared from 20-min time points prior to resupply is less than 30 pm (23). The concentration of α-thrombin required to generate a given rate of FPA release in blood can be estimated (57, 71); in this case, the observed change in FPA concentration in the 1st min (Fig. 6, panel B) when the resupply blood contains C921-78 yields an α-thrombin concentration in the range of 5 nm, whereas in the control resupply the minimum estimated thrombin concentration is ∼8 nm.

Two potential sources of low nanomolar levels of α-thrombin are as follows: clot-bound thrombin persisting from the initial episode of Tf-initiated clotting, and newly formed thrombin produced from pre-existing, clot-bound prothrombinase complex despite the presence of C921-78. The estimated concentration of prothrombinase immediately prior to resupply with CTI-blood in this experiment was ∼400 pm, yielding projected initial rates of α-thrombin formation in the absence of C921-78 of ∼4 nm/s under the conditions of the resupply regimen. Thus during resupply with CTI-blood, independent of any contributions from clot-bound thrombin, prothrombinase-derived thrombin sufficient to generate the observed rate of FPA release is produced within seconds.

Supporting the mechanism of FPA release by clot-bound thrombin, there is no evidence of significant prothrombin activation during the 1st min after resupply in the presence of C921-78 in either the synthetic coagulation proteome (Fig. 4) or CTI-blood (Fig. 6, panel A). However the detection limit for α-thrombin in the synthetic coagulation proteome format is ∼2.8 nm, whereas detection of less than 20 nm newly formed TAT would be difficult given the pre-existing levels of TAT (∼400 nm) in the clotted blood prior to resupply. Thus the detection of ∼5 nm newly produced α-thrombin in either system appears problematic. On the other hand, computational modeling of the resupply response in the presence of C921-78 (not shown) predicts an average level of ∼5 nm α-thrombin over the 1st min, reflecting the presteady state competition between fII and C921-78 for occupancy of the available prothrombinase. Thus, transient production of relatively low levels of α-thrombin (<1% of potential prothrombin pool) by prothrombinase during resupply in the presence of C921-78 is not ruled out by the empirical data and is consistent with computational predictions.

Collectively, these studies of Tf-initiated reactions in blood and the synthetic coagulation proteome indicate that the resupply response at 20 min can be explained primarily by the persistence of the prothrombinase complex in these reacting mixtures. The function of the intrinsic fXase complex appears critical to the formation during the Tf-initiated reaction of a level of prothrombinase complex sufficient to mount a resupply response. Clot-bound thrombin may be present, but its contribution to the process of renewed prothrombin activation and blood clotting upon resupply at 20 min is not essential.

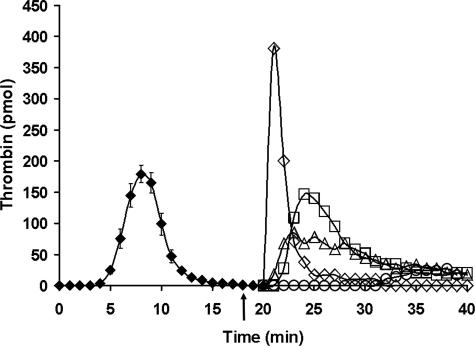

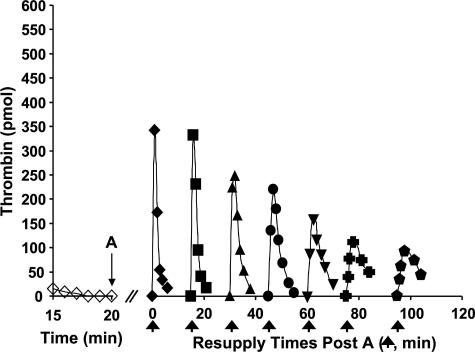

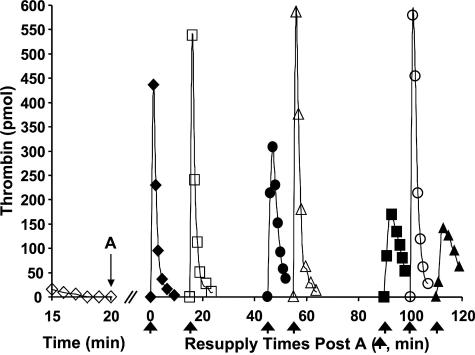

Stability of the Resupply Response in the Synthetic Coagulation Proteome—Fig. 7 depicts a study testing the stability of the resupply response over longer time intervals. A Tf-initiated synthetic coagulation proteome mixture was subdivided after 20 min, with individual aliquots then resupplied at different times. Resupply was conducted with only the fII/AT/PCPS mixture. Time course of thrombin generation at the extended times are presented with reference to the resupply conducted 20 min post-Tf initiation, which is defined as time 0 in the figure. When resupply of an aliquot that was incubated for an additional 15 min was conducted, the resulting time course of thrombin generation appeared unaltered. However, with more prolonged periods before resupply, time courses showed progressively decreasing maximum thrombin levels, with resupplied reactions taking longer to reach those maximum levels. At 95 min later than the usual resupply time of 20 min, peak thrombin levels were reduced to ∼1/3 those observed at 20 min, and the time to peak thrombin levels extended to between 3 and 4 min.

FIGURE 7.

Resupply of the synthetic coagulation proteome: stability of the

response. A 5 pm Tf-initiated reaction mixture was subdivided

after 20 min (A), and the seven separate aliquots resupplied either

immediately (20 min → t = 0, (♦)) or after an additional

15 (▪), 30 (▴), 45 (•), 60 (▾), 75

( ), or 95

(

), or 95

( ) min of incubation.

Resupply was conducted with an equal volume of a solution consisting of 1.4

μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, 2 μm PCPS.

Thrombin levels for the final 5 min of the Tf-initiated episode are also shown

(⋄). Thrombin levels are expressed as total picomoles of active thrombin

to normalize for the volume change. An arrow indicates the resupply

time for each aliquot.

) min of incubation.

Resupply was conducted with an equal volume of a solution consisting of 1.4

μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, 2 μm PCPS.

Thrombin levels for the final 5 min of the Tf-initiated episode are also shown

(⋄). Thrombin levels are expressed as total picomoles of active thrombin

to normalize for the volume change. An arrow indicates the resupply

time for each aliquot.

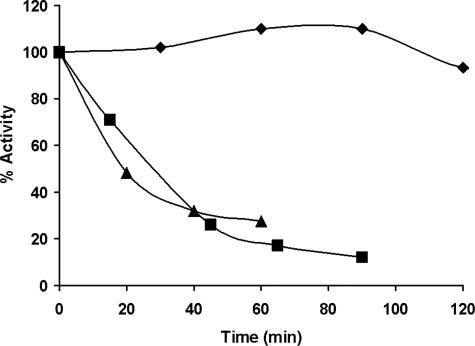

The data in Fig. 7 suggest that the prothrombinase concentration is declining over time. To test this more directly, the prothrombinase concentration present after 20 min in Tf-initiated proteome mixtures was measured and then reassessed at several later times. Fig. 8 presents the results of a representative experiment measuring prothrombinase levels in reaction mixtures constituted with PCPS membranes or platelets. Prothrombinase concentrations are expressed as a percentage of the concentration measured at 20 min post-Tf initiation. At 20 min post-initiation, the estimated prothrombinase concentration in the PCPS-supported reaction was ∼1.3 nm, whereas that in the platelet-supported reaction was ∼2.2 nm. Prothombinase concentrations in both reaction systems declined by about 70–80% over 60 min, with the overall rate of decline appearing somewhat greater than the rate at which the fII activating potential decreases (Fig. 7). In contrast, in the absence of AT, a mixture containing 1 nm prothombinase and equivalent PCPS and fVa appeared stable over this time frame.

FIGURE 8.

Stability of the prothrombinase complex formed in the synthetic coagulation proteome after Tf initiation. Synthetic coagulation proteome mixtures containing either 2 μm PCPS (▪) or 2 × 108 platelets/ml (▴) were treated with 5 pm Tf reagent and incubated for 20 min, and then aliquots were assayed immediately (20 min → t = 0) and at the indicated times thereafter for prothrombinase activity. Data from a representative experiment are shown with the prothrombinase concentrations expressed as a percentage of the prothrombinase activity present at 20 min. A time course presenting the stability of prothrombinase in a purified system composed of 1 nm fXa, 20 nm fVa, and 2 μm PCPS is also presented (♦).

The prothrombinase levels present 20 min after Tf initiation were lower in CTI-blood than in the proteome mixtures. A probable explanation for this difference is the presence of the other inhibitors in blood compared with the defined proteome mixture. In particular α1-proteinase inhibitor, which exhibits significant fXa inhibitory activity (72, 73), may suppress fXa levels during the Tf-initiated phase, thus reducing the final levels of prothrombinase in the system.

Fig. 9 presents an experiment similar to the one presented in Fig. 7 in which a Tf-initiated synthetic coagulation proteome mixture was subdivided after 20 min and then resupplied at various times later. In this case, the resupply mixtures alternated between fII/AT/PCPS (Fig. 9, closed symbols) and fII/AT/PCPS + fVIII (open symbols). The resupply response to the fII/AT/PCPS mixture showed the previously observed pattern of declining activity as the time prior to resupply increased. However, inclusion of fVIII into the resupply mixture yielded time courses of thrombin generation that appeared unaltered, even after an additional 100 min of incubation prior to resupply.

FIGURE 9.

Resupply of the synthetic coagulation proteome: the effect of fVIII on the stability of the response. A 5 pm Tf-initiated reaction mixture was subdivided after 20 min (A), and the eight separate aliquots subsequently resupplied at different times with an equal volume of a mixture containing 1.4 μm fII, 3.4 μm AT, 2 μm PCPS either without fVIII (closed symbols) or with 0.7 nm fVIII (open symbols). The resulting time courses of thrombin generation are presented. Resupply with the mixture without fVIII was conducted immediately (20 min → t = 0(♦), and 45 (•), 90 (▪), and 110 min (▴) later). Resupply with the mixture supplemented with fVIII was conducted at 15 (□), 55 (▵), and 100 min (○) after the subdivision of the Tf-initiated reaction. Thrombin levels for the final 5 min of the Tf-initiated episode are also shown (⋄). Thrombin levels are expressed as total picomoles of active thrombin to normalize for the volume change. An arrow indicates the resupply time for each aliquot.

Collectively, the studies defining prothrombinase levels and stability in ongoing Tf-initiated proteome mixtures, while supporting the central role for prothrombinase in the resupply response, also indicate that a functioning intrinsic fXase complex is important to the long term stability of the response.

DISCUSSION

The studies presented here were directed at identifying persisting catalytic species formed during an episode of Tf-initiated blood coagulation that have the potential to restart or maintain the clotting process. The identities of such end products of the Tf-initiated process are of interest both from the point of view of understanding the biochemical mechanism of hemorrhage control and as potential therapeutic targets for managing thrombotic disorders and surgical interventions. We used Tf-initiated reactions in normal and hemophilia blood or in their corresponding proteome mixtures as sources of procoagulant end products and then varied the resupplying material to determine the identity of the catalysts that drive the new cycle of fII activation. The central findings are as follows: 1) prothrombinase complexes accumulated during the episode of Tf-initiated coagulation are the primary catalysts responsible for the observed pattern of fII activation; 2) impairments in intrinsic fXase function, i.e. hemophilias, result in a depressed capacity to mount a resupply response; and 3) intrinsic fXase function contributes to the long term stability of the resupply response.

It has been reported that clot-bound thrombin can activate the procofactors fV and fVIII (29) as well as cleave fibrinogen (26, 27) and activate platelets (30). In the experimental systems used here, at 20 min post Tf-initiation, both fV and fVIII have already been quantitatively converted to their active cofactor forms (18, 57, 60), with fVIIIa levels reduced substantially because of its spontaneous inactivation (7, 74). Resupply with only fII/AT does not provide clot-bound thrombin with any targets whose activation could account for the rapid reinitiation of thrombin formation that occurs. When resupply is done with blood, targets become available for clot-bound thrombin, but this sequestered thrombin is in principle competing with the burst of thrombin that is released into the added blood by the pre-existing prothrombinase complex. The persistence of the prothrombinase complex would appear to dominate potential contributions from clot-bound thrombin in reinitiating coagulation.

Clot-bound thrombin has been implicated as an important agent in the normal wound healing processes, where its role may be critical because defects in thrombin production have been linked to wound healing problems in hemophilia (75). Data from this study could not be used to distinguish between contributions from clot-bound thrombin and prothrombinase-derived thrombin to the observed rate of fibrinogen cleavage upon resupply with CTI-blood. Further studies are required to establish the actual level of clot-bound thrombin at the time of resupply and, more importantly, to establish the relative stabilities of clot-bound thrombin and factor IXa and the prothrombinase complex within clotted CTI-treated blood. Kumatu and Hayashi (76) have reported significant decay of clot-bound thrombin activity as plasma-derived clots age. One could speculate that, in the context of normal hemostasis, the primary role of clot-bound thrombin involves its cytokine and growth factor-like activities, whereas clot-associated prothrombinase complex is the central catalyst of hemorrhage control.

We have shown that the resupply response is dependent upon the stability of the prothrombinase complex. We have also shown that the ability to form new intrinsic fXase upon resupply, accomplished experimentally by including fVIII with the fII/AT resupply solution, is by itself sufficient to counteract the decay in the prothrombinase activity. Thus in hemophilias A and B, the defect in intrinsic fXase function leads both to diminished levels of prothrombinase and to the absence of the repopulating function of the intrinsic fXase with respect to prothrombinase levels. The impairment to the restoration of the barrier is thus 2-fold. After hemophiliacs clot, the initial population density of the prothrombinase complex is lower. Thus, the absolute level of prothrombinase as it decays, relative to that in a normal individual, is significantly lower in the hemophiliac, resulting in a less robust response to any re-injury. In addition, any challenge to the barrier during this period of decay in prothrombinase activity is exacerbated in hemophilia A and B, because the normal mechanism to rapidly renew the declining prothrombinase population via efficient fXa formation is lacking.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. S. L. Liu, R. Lundblad, U. Hedner, S. Hardy, and W. Ruf for providing us with recombinant proteins. We also thank Dr. U. Sinha for C921-78 and M. Whelihan and B. Elmer for technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant PPG HL46703 (Project 1) (to K. G. M.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Tf, tissue factor; f, factor; AT, antithrombin; C921-78, benzenesulfonyl-d-Arg-Gly-Arg-ketothiazole; CTI, corn trypsin inhibitor; DAPA, dansylarginine-N-[3-ethyl-1,5-pentanediyl]amide; FPA, fibrinopeptide A; FPRck, d-Phe-Pro-ArgCH2Cl; PC, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; PS, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-3-glycero-3-[phospho-l-serine]; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor; TAT, thrombin-antithrombin complex.

K. G. Mann, M. Gissel, and T. Orfeo, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Komiyama, Y., Pedersen, A. H., and Kisiel, W. (1990) Biochemistry 29 9418-9425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orfeo, T., Brufatto, N., Nesheim, M. E., Xu, H., Butenas, S., and Mann, K. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 19580-19591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brummel, K. E., Paradis, S. G., Butenas, S., and Mann, K. G. (2002) Blood 100 148-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad, S. S., Rawala-Sheikh, R., and Walsh, P. N. (1992) Semin. Thromb. Hemostasis 18 311-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mann, K. G., Krishnaswamy, S., and Lawson, J. H. (1992) Semin. Hematol. 29 213-226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nesheim, M. E., Taswell, J. B., and Mann, K. G. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254 10952-10962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hockin, M. F., Jones, K. C., Everse, S. J., and Mann, K. G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 18322-18333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cawthern, K. M., van't Veer, C., Lock, J. B., DiLorenzo, M. E., Branda, R. F., and Mann, K. G. (1998) Blood 91 4581-4592 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman, M., and Monroe, D. M., III (2001) Thromb. Haemostasis 85 958-965 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butenas, S., Brummel, K. E., Branda, R. F., Paradis, S. G., and Mann, K. G. (2002) Blood 99 923-930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolberg, A. S., Allen, G. A., Monroe, D. M., Hedner, U., Roberts, H. R., and Hoffman, M. (2005) Br. J. Haematol. 131 645-655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drake, T. A., Morrissey, J. H., and Edgington, T. S. (1989) Am. J. Pathol. 134 1087-1097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilcox, J. N., Smith, K. M., Schwartz, S. M., and Gordon, D. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 2839-2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fleck, R. A., Rao, L. V., Rapaport, S. I., and Varki, N. (1990) Thromb. Res. 59 421-437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman, M., Colina, C. M., McDonald, A. G., Arepally, G. M., Pedersen, L., and Monroe, D. M. (2007) J. Thromb. Haemost. 5 1403-1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brand, K., Fowler, B. J., Edgington, T. S., and Mackman, N. (1991) Mol. Cell. Biol. 11 4732-4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osterud, B. (2001) Semin. Hematol. 38 2-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van't Veer, C., and Mann, K. G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 4367-4377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butenas, S., Bouchard, B. A., Brummel-Ziedins, K. E., Parhami-Seren, B., and Mann, K. G. (2005) Blood 105 2764-2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santucci, R. A., Erlich, J., Labriola, J., Wilson, M., Kao, K. J., Kickler, T. S., Spillert, C., and Mackman, N. (2000) Thromb. Haemostasis 83 445-454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berckmans, R. J., Neiuwland, R., Boing, A. N., Romijn, F. P., Hack, C. E., and Sturk, A. (2001) Thromb. Haemostasis 85 639-646 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day, S. M., Reeve, J. L., Pedersen, B., Farris, D. M., Myers, D. D., Im, M., Wakefield, T. W., Mackman, N., and Fay, W. P. (2005) Blood 105 192-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orfeo, T., Butenas, S., Brummel-Ziedins, K. E., and Mann, K. G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42887-42896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis, C. W., Markham, R. E., Jr., Barlow, G. H., Florack, T. M., Dobrzynski, D. M., and Marder, V. J. (1983) J. Lab. Clin. Med. 102 220-230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogg, P. J., and Jackson, C. M. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 3619-3623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naski, M. C., and Shafer, J. A. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265 1401-1407 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weitz, J. I., Hudoba, M., Massel, D., Maraganore, J., and Hirsh, J. (1990) J. Clin. Investig. 86 385-391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendayan, P., Boccalon, H., Dupouy, D., and Boneu, B. (1994) Thromb. Haemostasis 71 576-580 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar, R., Beguin, S., and Hemker, H. C. (1994) Thromb. Haemostasis 72 713-721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar, R., Beguin, S., and Hemker, H. C. (1995) Thromb. Haemostasis 74 962-968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fredenburgh, J. C., Stafford, A. R., Pospisil, C. H., and Weitz, J. I. (2004) Biophys. Chem. 112 277-284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi, H., Satoh, N., Wada, K., Takakuwa, E., Seki, Y., and Shibata, A. (1994) Am. J. Hematol. 46 333-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giesen, P. L., Rauch, U., Bohrmann, B., Kling, D., Roque, M., Fallon, J. T., Badimon, J. J., Himber, J., Riederer, M. A., and Nemerson, Y. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 2311-2315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamant, M., Nieuwland, R., Pablo, R. F., Sturk, A., Smit, J. W., and Radder, J. K. (2002) Circulation 106 2442-2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berckmans, R. J., Nieuwland, R., Tak, P. P., Boing, A. N., Romijn, F. P., Kraan, M. C., Breedveld, F. C., Hack, C. E., and Sturk, A. (2002) Arthritis Rheum. 46 2857-2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balasubramanian, V., Grabowski, E., Bini, A., and Nemerson, Y. (2002) Blood 100 2787-2792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muller, I., Klocke, A., Alex, M., Kotzsch, M., Luther, T., Morgenstern, E., Zieseniss, S., Zahler, S., Preissner, K., and Engelmann, B. (2003) FASEB J. 17 476-478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falati, S., Liu, Q., Gross, P., Merrill-Skoloff, G., Chou, J., Vandendries, E., Celi, A., Croce, K., Furie, B. C., and Furie, B. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197 1585-1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chou, J., Mackman, N., Merrill-Skoloff, G., Pedersen, B., Furie, B. C., and Furie, B. (2004) Blood 104 3190-3197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.del Conde, I., Shrimpton, C. N., Thiagarajan, P., and Lopez, J. A. (2005) Blood 106 1604-1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogdanov, V. Y., Balasubramanian, V., Hathcock, J., Vele, O., Lieb, M., and Nemerson, Y. (2003) Nat. Med. 9 458-462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zillmann, A., Luther, T., Muller, I., Kotzsch, M., Spannagl, M., Kauke, T., Oelschlagel, U., Zahler, S., and Engelmann, B. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281 603-609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siddiqui, F. A., Desai, H., Amirkhosravi, A., Amaya, M., and Francis, J. L. (2002) Platelets (Abingdon) 13 247-253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Camera, M., Frigerio, M., Toschi, V., Brambilla, M., Rossi, F., Cottell, D. C., Maderna, P., Parolari, A., Bonzi, R., De Vincenti, O., and Tremoli, E. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23 1690-1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwertz, H., Tolley, N. D., Foulks, J. M., Denis, M. M., Risenmay, B. W., Buerke, M., Tilley, R. E., Rondina, M. T., Harris, E. M., Kraiss, L. W., Mackman, N., Zimmerman, G. A., and Weyrich, A. S. (2006) J. Exp. Med. 203 2433-2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panes, O., Matus, V., Saez, C. G., Quiroga, T., Pereira, J., and Mezzano, D. (2007) Blood 109 5242-5250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hathcock, J. J., and Nemerson, Y. (2004) Blood 104 123-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jesty, J., and Beltrami, E. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25 2463-2469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bajaj, S. P., Rapaport, S. I., and Prodanos, C. (1981) Prep. Biochem. 11 397-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katzmann, J. A., Nesheim, M. E., Hibbard, L. S., and Mann, K. G. (1981) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78 162-166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffith, M. J., Noyes, C. M., and Church, F. C. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260 2218-2225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nesheim, M. E., Katzmann, J. A., Tracy, P. B., and Mann, K. G. (1981) Methods Enzymol. 80 249-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lundblad, R. L., Kingdon, H. S., and Mann, K. G. (1976) Methods Enzymol. 45 156-176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krishnaswamy, S., Church, W. R., Nesheim, M. E., and Mann, K. G. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262 3291-3299 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hojima, Y., Pierce, J. V., and Pisano, J. J. (1980) Thromb. Res. 20 149-162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins, D. L., and Mann, K. G. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258 6503-6508 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rand, M. D., Lock, J. B., van't Veer, C., Gaffney, D. P., and Mann, K. G. (1996) Blood 88 3432-3445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Butenas, S., Brummel, K. E., Paradis, S. G., and Mann, K. G. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23 123-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brummel, K. E., Butenas, S., and Mann, K. G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 22862-22870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawson, J. H., Kalafatis, M., Stram, S., and Mann, K. G. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 23357-23366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mustard, J. F., Perry, D. W., Ardlie, N. G., and Packham, M. A. (1972) Br. J. Haematol. 22 193-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalafatis, M., Egan, J. O., van't Veer, Cawthern, K. M., and Mann, K. G. (1997) Crit. Rev. Eukaryotic Gene Expression 7 241-280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Church, W. R., Messier, T. L., Tucker, M. M., and Mann, K. G. (1988) Blood 72 1911-1921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Betz, A., Wong, P. W., and Sinha, U. (1999) Biochemistry 38 14582-14591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hibbard, L. S., Nesheim, M. E., and Mann, K. G. (1982) Biochemistry 21 2285-2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okamoto, S., and Hijikata-Okunomiya, A. (1993) Methods Enzymol. 222 328-340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Butenas, S., van't Veer, C., and Mann, K. G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 21527-21533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shafer, J. A. (1988) Clin. Lab. Sci. 26 1-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doolittle, R. F. (1994) in Haemostasis and Thrombosis (Bloom, A. L., Forbes, C. D., Thomas, D. P., and Tuddenham, E. G. D., eds) pp. 491-513, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, UK

- 71.Mihalyi, E. (1988) Biochemistry 27 976-982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ellis, V., Scully, M., MacGregor, I., and Kakkar, V. (1982) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 701 24-31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gitel, S. N., Medina, V. M., and Wessler, S. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259 6890-6895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fay, P. J., Beattie, T. L., Regan, L. M., O'Brien, L. M., and Kaufman, R. J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 6027-6032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoffman, M., Harger, A., Lenkowski, A., Hedner, U., Roberts, H. R., and Monroe, D. M. (2006) Blood 108 3053-3060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Komatsu, Y., and Hayashi, H. (2000) Biol. Pharm. Bull. 23 502-505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]