Abstract

Bcl2 not only prolongs cell survival but also suppresses the repair of abasic (AP) sites of DNA lesions. Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) plays a central role in the repair of AP sites via the base excision repair pathway. Here we found that Bcl2 down-regulates APE1 endonuclease activity in association with inhibition of AP site repair. Exposure of cells to nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone results in accumulation of Bcl2 in the nucleus and interaction with APE1, which requires all of the BH domains of Bcl2. Deletion of any of the BH domains from Bcl2 abrogates the ability of Bcl2 to interact with APE1 as well as the inhibitory effects of Bcl2 on APE1 activity and AP site repair. Overexpression of Bcl2 in cells reduces formation of the APE1·XRCC1 complex, and purified Bcl2 protein directly disrupts the APE1·XRCC1 complex with suppression of APE1 endonuclease activity in vitro. Importantly, specific knockdown of endogenous Bcl2 by RNA interference enhances APE1 endonuclease activity with accelerated AP site repair. Thus, Bcl2 inhibition of AP site repair may occur in a novel mechanism by down-regulating APE1 endonuclease activity, which may promote genetic instability and tumorigenesis.

Apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP)2 or abasic sites are the most common form of DNA damage with about 20,000–50,000 sites produced in each cell/day (1, 2). AP sites can result from spontaneous and chemically initiated hydrolysis through various conditions, including ionizing radiation, UV irradiation, oxidative stress, and exposure to cigarette smoking (1–4). Human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (APE1) is a major constituent of the base excision repair (BER) pathway of AP sites of DNA lesions (3). Additionally, APE1 is also named as redox effector factor-1 (1) because of its redox abilities on different redox-regulated transcription factors (3, 5). Two activities of this molecule are split into two functionally independent domains of the protein itself: the N terminus is principally devoted to the redox activity, whereas the C terminus exerts enzymatic activity on the repair of AP sites of DNA lesions (3, 5). APE1 specifically binds to abasic sites and cuts the 5′ phosphodiester bond with its endonuclease activity to produce a DNA primer with 3′ hydroxyl end, which is a required step in the BER repair pathway (3). Therefore, APE1 is an essential endonuclease and plays a central role in the repair of AP sites of DNA lesions.

Bcl2, a major cellular oncogenic protein, plays pivotal roles in enhancing cell survival, retarding G1/S cell cycle transition, and attenuating DNA repair (4, 6, 7). Because overexpression of Bcl2 results in lymphomagenesis in transgenic mice, this suggests that Bcl2, in addition to its survival activity, may also potentially have an oncogenic property (8). However, the mechanism(s) by which Bcl2 facilitates oncogenesis is not fully understood. The oncogenic effect of Bcl2 may result from its multiple cellular properties. Bcl2 was originally discovered as a gene product at the chromosomal breakpoint of t(14;18) (9), which may play a role in genetic instability and tumor development by impeding DNA repair. It has been reported that Bcl2 can enhance benzene metabolite-induced DNA damage and mutagenesis in human promyelocytic HL60 cells (10). Overexpression of Bcl2 not only attenuates the nucleotide excision repair capacity and DNA replication in UV-irradiated HL60 cells (11) but also inhibits γ-ray-induced homologous recombination repair pathways (12). Bcl2 can also suppress DNA mismatch repair by inhibiting E2F transcriptional activity (13). Intriguingly, our recent findings reveal that Bcl2 suppression of DNA mismatch repair occur in a mechanism by directly regulating the heterodimeric hMSH2·hMSH6 complex, which leads to enhanced mutagenesis (14). Thus, the oncogenic activity of Bcl2 may result from its inhibitory effects on multiple DNA repair pathways.

Nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) is the most potent carcinogen contained in cigarette smoke that can induce cellular DNA damage including AP sites of DNA lesions (4, 15, 16). NNK-induced AP sites of DNA lesions, if unrepaired or repaired incorrectly, could be mutagenic, which may lead to mutations and chromosomal breaks with malignant transformation. We previously discovered that Bcl2 potently suppresses the repair of NNK-induced abasic sites of DNA lesions (4). However, the mechanism(s) is not fully understood. Here we found that Bcl2 not only directly interacts with APE1 but also inhibits its endonuclease activity, which leads to suppression of AP site repair.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Bcl2, APE1, XRCC1, and tubulin antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). NNK was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada). Purified recombinant WT, ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, and ΔBH4 Bcl2 mutant proteins were obtained from ProteinX Lab (San Diego, CA). Purified recombinant APE1 protein was purchased from Abnova Corporation (Taipei, Taiwan). Synthetic human Bcl2 siRNA (sense strand sequence, GGAUCCAGGAUAACGGAGGTT) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. All of the reagents used were obtained from commercial sources unless otherwise stated.

Generation of Various Bcl2 Deletion Mutants—To create ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, and ΔBH4 Bcl2 deletion mutants, the 5′ phosphorylated mutagenic primers for various precise deletion mutants were synthesized as follow: ΔBH1, 5′-GGA CGC TTT GCC ACG GTG GTG GAG GTG GAG AGC GTC AAC AGG GAG ATG-3′; ΔBH2, 5′-GAG TAC CTG AAC CGG CAT CTG CAC CGA CCT CTG TTT GAT TTC TCC TGG-3′; ΔBH3, 5′-GCG CTC AGC CCT GTG CCA CCT GTG GAC TTC GCA GAG ATG TCC AGT CAG-3′; ΔBH4, 5′-GGA AGG ATG GCG CAA GCC GGG AGA GCT GGA GAT GCG GAC GCG GCG CCC CTG-3′. The WT-Bcl2/pUC19 construct was used as the target plasmid that contains a unique NdeI restriction site for selection against the unmutated plasmid. The NdeI selection primer is: 5′-GAG TGC ACC ATG GGC GGT GTG AAA-3′. Various Bcl2 BH deletion mutants were created by using a mutagenesis kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions and confirmed by sequencing of the cDNA. The WT and various Bcl2 deletion mutants were then cloned into the pCIneo (Promega) mammalian expression vector.

Cell Lines, Plasmids, and Transfections—Various human lung cancer cells were maintained as previously described (4). The pCIneo plasmid containing each Bcl2 mutant cDNA was transfected into H1299 cells using LipfectAMINE™2000 (Invitrogen). Clones stably expressing WT or each of the Bcl2 deletion mutants were selected in a medium containing G418 (0.6 mg/ml). The expression levels of exogenous Bcl2 were analyzed by Western blot analysis. Three separate clones for each mutant expressing similar amounts of exogenous Bcl2 were selected for further analysis.

Preparation of Cell Lysates—Cells were washed with 1× PBS and resuspended in ice-cold 1% CHAPS lysis buffer (1% CHAPS, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 120 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm Na3VO4, 50 mm NaF, and 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol) with a mixture of protease inhibitors (Calbiochem). The cells were lysed by sonication and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was collected as the total cell lysate and used for protein analysis or co-immunoprecipitation as described (6).

Subcellular Fractionation—Subcellular fractionation was performed as described previously (4). Briefly, the cells (2 × 107) were washed once with cold 1× PBS and resuspended in isotonic mitochondrial buffer (210 mm mannitol, 70 mm sucrose, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.5) containing protease inhibitor mixture set I (Calbiochem). The resuspended cells were homogenized with a polytron homogenizer operating for four bursts of 10 s each at a setting of 5 and then centrifuged at 2000 × g for 3 min to pellet the nuclei and unbroken cells. The supernatant was centrifuged at 13,000 ×g for 10 min to pellet mitochondria. The mitochondria was washed with mitochondrial buffer, resuspended with 1% Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer, rocked for 60 min, and then centrifuged at 17,530 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant containing mitochondrial proteins was collected. For nuclear fractionation, the cells were washed with 1× PBS and suspended in 2 ml of Buffer A (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 0.03% Nonidet P-40 with fresh protease inhibitor mixture set I). The samples were incubated on ice until more than 95% of cells could be stained by trypan blue. The samples were then centrifuged at 500 × g at 4 °C for 5 min. The resulting nuclear pellet was washed with Buffer B (50 mm NaCl, 10 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm spermidine, 0.15 mm spermine) and then resuspended in 150 μl of Buffer C (350 mm NaCl, 10 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm spermidine, 0.15 mm spermine) and rocked at 4 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation (14, 000 × g) at 4 °C, the supernatant (nuclear fraction) was collected. Protein (100 μg) from each fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting using a Bcl2 antibody.

Immunofluorescence Staining—The cell were washed with 1× PBS, fixed with cold methanol and acetone (1:1) for 5 min, and then blocked with 10% normal rabbit serum for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were incubated with a rabbit Bcl2 primary antibody for 90 min. After washing, the samples were incubated with Alexa 594 (red)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies for 60 min. The cells were washed with 1× PBS and observed under a fluorescent microscope (Zeiss). Pictures were taken of each sample.

AP Oligonucleotide Assay for APE1 Endonuclease Activity—A 26-mer oligonucleotide (IDT Technologies, Coralville, IA) containing a tetrahydrofuran (F) residue at position 15 was used as the APE1 substrate as described (1, 2). Following 32P labeling, the oligonucleotides were purified using a G25 column and then annealed to a complementary oligonucleotide. Assays using nuclear extract isolated from cells or purified APE1 protein were performed in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 2.5 pmol of labeled double-stranded F oligonucleotide, in 50 mm Hepes, 50 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 1 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 0.05% Triton X-100, pH 7.5. The reactions were allowed to proceed for 15 min in a 37 °C water bath and stopped by adding an equal volume of 96% formamide, 10 mm EDTA, and bromphenol blue. 10 μl of this 40-μl sample was separated with a 20% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 m urea. APE1 endonuclease activity was analyzed by autoradiography.

AP Site Counting in Genomic DNA—Genomic DNA was purified using a DNA isolation kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). The number of AP sites was assessed using a DNA damage quantification (AP site counting) kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.). Aldehyde reactive probe (ARP) reagent (N′-aminooxymethylcarbonylhydrazino-d-biotin) can react specifically with an aldehyde group that is the open ring form of the AP sites. After treating DNA containing AP sites with ARP reagent, AP sites are tagged with biotin residues. By using an excess amount of ARP, all AP sites can be converted to biotin-tagged AP sites. Standard ARP DNA and purified ARP-labeled sample genomic DNA was fixed on a 96-well plate with DNA binding solution. Then the number of AP sites in the sample DNA was determined by the biotin-avidin-peroxidase assay. The absorbance of the samples was analyzed using a microplate reader with a 650-nm filter. Each experiment was repeated three times, and the data represent the means ± S.D. of three determinations.

Bcl2 Silence—This is a technique for down-regulating the expression of a specific gene in living cells by introducing a short homologous double-stranded RNA. H460 cells expressing high levels of endogenous Bcl2 were transfected with Bcl2 siRNA (10 nm) using LipofectAMINE™ 2000. A control siRNA (nonhomologous to any known gene sequence) was used as a negative control. The levels of Bcl2 expression were analyzed by Western blotting. Specific silencing of the targeted Bcl2 gene was confirmed by at least three independent experiments.

RESULTS

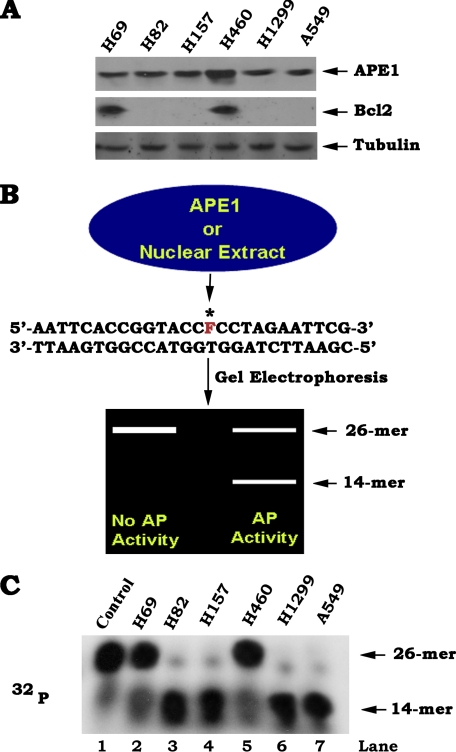

Expression of Endogenous Bcl2 Is Associated with Decreased APE1 Endonuclease Activity in Various Human Lung Cancer Cells—APE1 is a multifunctional DNA repair enzyme that mainly functions as an abasic endonuclease in the BER pathway (1–3). Intriguingly, APE1 is widely expressed in both small cell lung cancer and nonsmall cell lung cancer cells (Fig. 1A), suggesting that APE1 may play a role in regulating DNA repair in human lung cancer cells. Bcl2, a major antiapoptotic and/or oncogenic protein, is found to co-express with APE1 in H69 and H460 but not in other lung cancer cells tested (Fig. 1A). We previously discovered that Bcl2 can suppress the repair of abasic sites of DNA lesions (4). However, the mechanism(s) remains enigmatic. To test whether endogenous expression of Bcl2 may potentially regulate APE1 function, AP endonuclease activity was measured in various lung cancer cells. A 26-mer 32P-labeled, AP site mimetic, double-stranded F oligonucleotide was used as an APE1 substrate as described (1, 2). As shown in Fig. 1B, the cleaved product should be observed as a 14-mer fragment that will indicate the AP endonuclease repair activity. By contrast, the uncleaved oligonucleotide correlating to no activity should be observed as a 26-mer fragment. Thus, the AP endonuclease activity was determined by the amount of cleaved product (14-mer). 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extract isolated from various human lung cancer cells. Decreased levels of AP endonuclease activity (i.e. smaller amount of cleaved 14-mer products and greater amount of uncleaved 26-mer oligonucleotides) were observed in both H460 and H69 cells that express high levels of endogenous Bcl2 as compared with the other cell lines that express undetectable levels of Bcl2 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that Bcl2 may play a negative role in regulating APE1 endonuclease activity.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of endogenous Bcl2 in human lung cancer cells is associated with decreased APE1 endonuclease activity. A, expression levels of endogenous Bcl2 and APE1 in various human lung cancer cells were analyzed by Western blot. B, schematic representation of AP oligonucleotide endonuclease assay. Radiolabeled 26-mer oligonucleotide containing a tetrahydrofuran AP site mimic (F) at position 15 in the labeled strand reacts with APE1 protein or nuclear extract isolated from cells in assay buffer. After the reaction is stopped, the fragments are denatured and analyzed on a DNA gel. If there is no AP endonuclease activity at the AP site, the unreacted product migrates as a 26-mer, whereas AP endonuclease activity is shown as a 14-mer fragment. C, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extract (5 μg) isolated from various human lung cancer cells. AP endonuclease activity was measured and analyzed by autoradiography in various human lung cancer cells. Lane 1 is the 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotide-only control without treatment.

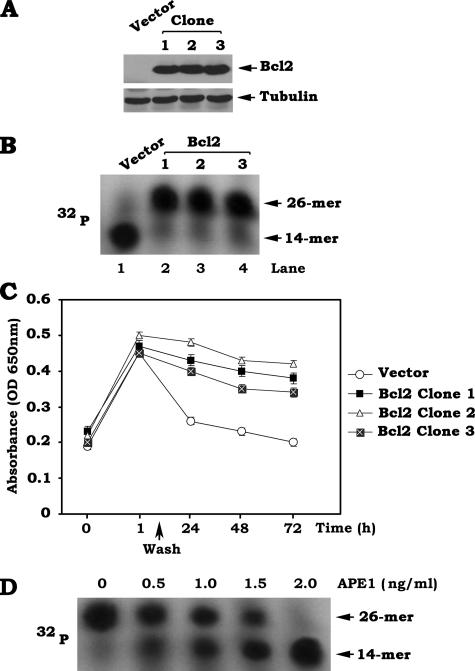

Overexpression of Exogenous Bcl2 Down-regulates APE1 Activity and Potently Suppresses AP Site Repair—To directly test effects of Bcl2 on APE1 function and AP site repair, Bcl2 was stably overexpressed in H1299 cells that do not express detectable levels of endogenous Bcl2. A majority of the 26-mer oligonucleotides was cleaved into 14-mer products after incubation with the nuclear extract isolated from vector-only control cells, indicating a strong AP endonuclease activity in vector-only H1299 cells (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, overexpression of Bcl2 prevents the 26-mer oligonucleotides from cleavage (Fig. 2, A and B). These findings suggest that Bcl2 suppresses APE1 endonuclease activity. Similar results were obtained from three independent clones expressing similar levels of exogenous Bcl2, indicating that these findings are reliable. Because APE1 endonuclease activity is essential for AP site repair, Bcl2-mediated inhibition of APE1 endonuclease activity may suppress AP site repair. To test this possibility, Bcl2-overexpressing H1299 cells or vector-only control cells were treated with NNK for 60 min. The cells were then washed and incubated with normal cell culture medium for various times up to 72 h. AP sites of DNA lesions in genomic DNA were assessed using a DNA damage quantification (AP site counting) kit and analyzed using a microplate reader with a 650-nm filter as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results reveal that NNK significantly enhances the AP sites of DNA lesions in both WT Bcl2-expressing and vector-only control cells within 60 min (Fig. 2C). After removal of NNK from the culture medium, AP sites of DNA lesions in vector-only control cells are significantly reduced within 24 h, indicating that most AP sites are repaired in vector-only control cells (Fig. 2C). By contrast, increased AP sites of DNA lesions are observed in Bcl2-overexpressing cells as compared with vector-only control cells after 24 h (Fig. 2C), suggesting that overexpression of Bcl2 potently inhibits the repair of NNK-induced AP sites of DNA lesions. Similar results were obtained from three independent clones expressing similar levels of exogenous Bcl2 (Fig. 2C). To test whether purified APE1 protein can restore the endonuclease activity in Bcl2 expressing extracts, increasing concentrations (i.e. 0.5–2.0 ng/ml) of purified APE1 protein were added to the nuclear extract(s) isolated from Bcl2-overexpressing H1299 cells in assay buffer. The results reveal that the addition of purified APE1 results in a dose-dependent increase in the production of the cleaved fragments (i.e. 14-mer) with a gradual decrease of the uncleaved 26-mer oligonucleotides (Fig. 2D), indicating that the addition of active APE1 is able to restore the endonuclease activity in Bcl2-expressing extracts.

FIGURE 2.

Overexpression of exogenous Bcl2 suppresses APE1 endonuclease activity in association with decreased AP site repair. A, Bcl2/pCIneo DNA construct was stably transfected into H1299 human lung cancer cells. Expression levels of Bcl2 were determined by Western blotting. B, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotide was incubated with nuclear extract (5 μg) isolated from vector-only control cells or three stable clones expressing similar levels of exogenous Bcl2. APE1 endonuclease activity was analyzed by autoradiography. C, vector-only control cells or three stable clones expressing similar levels of exogenous Bcl2 were treated with NNK (5 μm) for 60 min. The cells were washed and incubated in regular culture medium for various times up to 72 h. The AP sites were analyzed using an AP site counting kit. The data represent the means ± S.D. of three separate determinations. D, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extract (5 μg) isolated from Bcl2-overexpressing H1299 cells in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations (0.5–2 ng/ml) of purified APE1. APE1 endonuclease activity was analyzed by autoradiography.

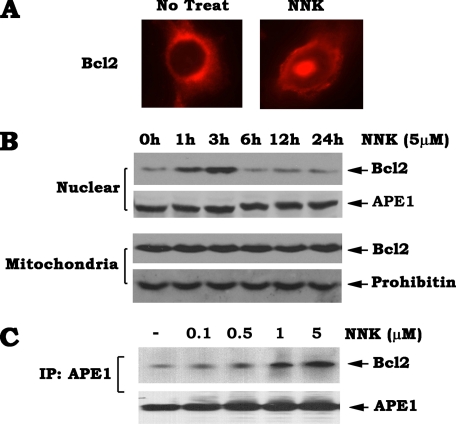

Exposure of Cells to the DNA-damaging Agent NNK Promotes Bcl2 Accumulation and Association with APE1 in Nucleus—Bcl2 is primarily localized in the outer mitochondrial membranes with minor expression in nuclear and endoplasmic reticulum membrane systems (17, 18). Recent reports indicate that Bcl2 also resides in the nucleoplasm and functions within the nucleus (4, 19, 20). We have previously demonstrated that the nuclear-localized Bcl2 has no antiapoptotic activity but is able to suppress DNA repair (4). To test how Bcl2 regulates APE1 following DNA damage, H460 cells expressing high levels of endogenous Bcl2 and APE1 were exposed to NNK (5 μm) for 60 min. Subcellular distribution of Bcl2 was then examined by immunofluorescent staining. Consistent with our previous findings (4), the majority of Bcl2 is localized in cytoplasm, and only a small proportion is located in the nucleus in untreated cells. Intriguingly, Bcl2 is accumulated in nucleus after exposure of cells to NNK for 60 min (Fig. 3A). To further confirm this, subcellular fractionation was carried out to isolate mitochondrial and nuclear fractions. The results reveal that nuclear Bcl2 expression is enhanced within 60 min (Fig. 3B). After 3 h, the increased levels of nuclear Bcl2 are gradually reduced to the same level as the no treatment control (i.e. after the 6-h time point; Fig. 3B), indicating that NNK-enhanced nuclear Bcl2 expression occurs in a time-dependent manner. By contrast, the levels of mitochondrial Bcl2 show no significant change in the time course experiment (Fig. 3B, lower panel). Thus, increased nuclear Bcl2 may not result from a movement from mitochondria into nucleus. This effect on Bcl2 following exposure of cells to NNK may occur through a transcriptional or other unknown mechanism(s). Further study is required to demonstrate this possibility.

FIGURE 3.

DNA-damaging agent NNK promotes Bcl2 nuclear accumulation and interaction with APE1. A, H460 cells expressing high levels of endogenous Bcl2 were treated with NNK (5 μm) for 60 min. Subcellular distribution of Bcl2 was examined by immunofluorescent staining using a rabbit antibody against human Bcl2 and Alexa 594 (red)-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies for 60 min. The samples were observed under a fluorescent microscope (Zeiss). B, H460 cells were treated with NNK (5 μm) for various times. Subcellular fractionation was performed to isolate nuclear and mitochondrial fractions. The levels of Bcl2 in the nuclear or mitochondrial fraction were analyzed by Western blotting using a Bcl2 antibody. C, H460 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of NNK for 1 h. A co-immunoprecipitation (IP) experiment was performed in isolated nuclear extract using APE1 antibody. Bcl2 and APE1 were analyzed by Western blot.

To test for a direct interaction between Bcl2 and APE1 in nucleus, a co-immunoprecipitation was performed using isolated nuclear extract and an agarose-conjugated APE1 antibody. The results reveal that NNK-induced DNA damage promotes Bcl2 to associate with APE1 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C, upper panel). Thus, Bcl2 suppression of APE1 activity and AP site repair may occur in a novel mechanism by a direct interaction with APE1.

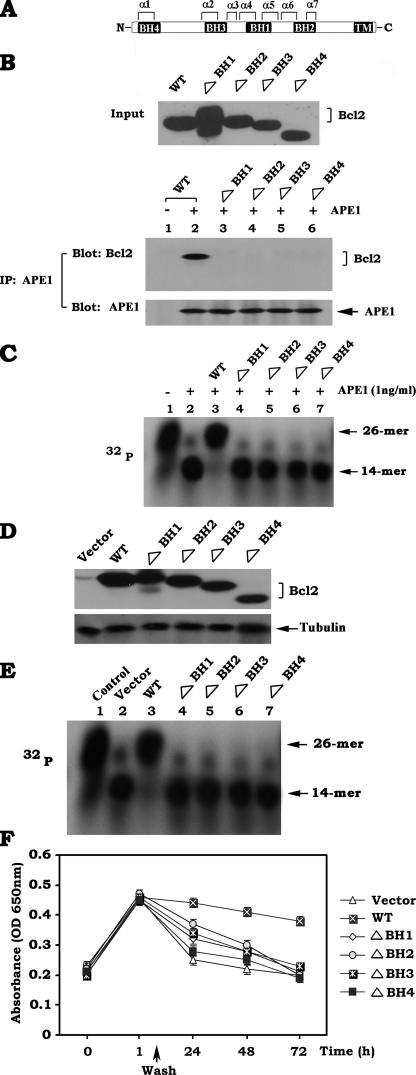

Bcl2 Directly Interacts with APE1 via Its BH Domains, and Deletion of Any of the BH Domains from Bcl2 Results in Loss of the Ability of Bcl2 to Suppress APE1 Endonuclease Activity and AP Site Repair—Bcl2 family members share homology in the BH domains including BH1, BH2, BH3, and BH4 (21). To assess whether Bcl2 directly binds to APE1 via its BH domains, purified recombinant APE1 protein (10 ng) was incubated with purified recombinant WT, ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, or ΔBH4 Bcl2 deletion mutants (10 ng each) in 1% CHAPS lysis buffer at 4 °C for 2 h. The APE1-associated Bcl2 was co-immunoprecipitated with an agarose-conjugated APE1 antibody. The results demonstrate that APE1 is able to associate with WT but not with any of the ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, and ΔBH4 Bcl2 mutants (Fig. 4B, lower panel), indicating that all BH domains are essential for Bcl2 to interact with APE1. Because WT Bcl2 could not be immunoprecipitated by the APE1 antibody in the absence of APE1 (Fig. 4B, lower panel, lane 1 versus lane 2), this suggests that the binding of Bcl2 to APE1 is specific in this assay. To test whether Bcl2 protein directly affects APE1 endonuclease activity in vitro, a 32P-labeled, AP site mimetic, double-stranded F oligonucleotide was incubated with purified, active APE1 (1 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of purified recombinant WT or each of the BH deletion Bcl2 mutant proteins (1 ng/ml each) in the assay buffer as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results reveal that purified APE1 efficiently cleaves the 26-mer oligonucleotides into a 14-mer fragment (Fig. 4C, lane 2). The addition of purified WT Bcl2 protein prevents the 26-mer oligonucleotide from cleavage induced by APE1 (Fig. 4C, lane 3), suggesting that Bcl2 can directly inhibit APE1 endonuclease activity in vitro. Intriguingly, all of the BH deletion Bcl2 mutant proteins fail to suppress APE1-induced cleavage of 26-mer oligonucleotide (Fig. 4C, lanes 4–7), indicating that deletion of any of the BH domains abrogates the capacity of Bcl2 to inhibit APE1 endonuclease activity. To functionally test this in vivo, APE1 endonuclease activity and AP sites of DNA lesions were compared in cells expressing WT or each of the BH deletion mutants. The results indicate that higher levels of APE1 endonuclease activity and accelerated AP site repair were observed in cells expressing each of the BH deletion mutants as compared with WT Bcl2-expressing cells (Fig. 4, D–F). This supports the notion that the binding of Bcl2 to APE1 via its BH domains may be required for the effect of Bcl2 on APE1 activity and AP site repair.

FIGURE 4.

Bcl2 directly interacts with APE1 via the BH domains of Bcl2, and deletion of any of the BH domains from Bcl2 results in loss of the ability of Bcl2 to suppress APE1 endonuclease activity as well as AP site repair. A, schematic representation of the BH domains in Bcl2 protein. B, purified recombinant APE1 (10 ng) was incubated with purified WT, ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, or ΔBH4 Bcl2 deletion mutants (10 ng each) in 1% CHAPS lysis buffer at 4 °C for 2 h. The APE1-associated Bcl2 was co-immunoprecipitated (IP) with APE1 antibody. The APE1-associated Bcl2 was analyzed by Western blot. C, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with APE1 (1 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of purified, recombinant WT, ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, or ΔBH4 Bcl2 mutant protein (1 ng/ml) for 15 min. APE1 activity was analyzed by autoradiography. Lane 1 is the 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotide-only control without treatment. D, WT, ΔBH1, ΔBH2, ΔBH3, and ΔBH4 Bcl2 mutants were stably transfected into H1299 cells. Expression levels of Bcl2 were analyzed by Western blot. E, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extract isolated from vector-only cells or H1299 cells expressing WT or each of the BH deletion Bcl2 mutants. APE1 endonuclease activity was analyzed by autoradiography. Lane 1 is the 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotide-only control without treatment. F, vector-only control cells or H1299 cells expressing WT or each of the BH deletion Bcl2 mutants were treated with NNK (5 μm) for 60 min. The cells were washed and incubated in regular culture medium for various times up to 72 h. The AP sites were analyzed using an AP site counting kit. The data represent the means ± S.D. of three separate determinations.

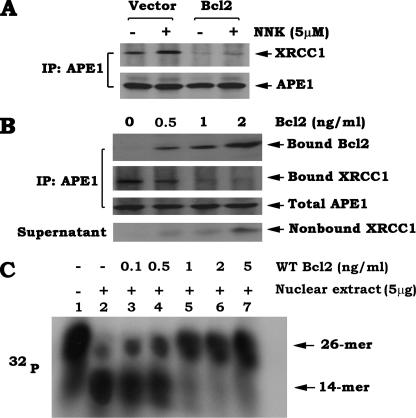

Overexpression of Bcl2 in Cells Inhibits Formation of the APE1·XRCC1 Complex, and Purified Bcl2 Directly Disrupts the APE1·XRCC1 Interaction in Association with a Dose-dependent Inhibition of APE1 Endonuclease Activity in Vitro—It has been reported that a physical interaction between APE1 and XRCC1 significantly enhances APE1 endonuclease activity (22). Because Bcl2 not only directly interacts with APE1 but also suppresses APE1 endonuclease activity in association with inhibition of AP site repair (Figs. 2, 3, 4), Bcl2 may affect the functional interaction between APE1 and XRCC1 via binding to APE1. To test this, association of APE1·XRCC1 was compared in Bcl2-overexpressing H1299 cells and vector-only control cells in the absence and presence of NNK. The results reveal that decreased levels of the APE1·XRCC1 complex were observed in the Bcl2-overexpressing cells as compared with vector control cells with or without NNK treatment, suggesting that expression of Bcl2 inhibits formation of the APE1·XRCC1 complex in cells (Fig. 5A). To further test whether Bcl2 can directly dissociate the APE1·XRCC1 complex in vitro, the APE1·XRCC1 complex was co-immunoprecipitated from H1299 parental cells expressing undetectable levels of endogenous Bcl2 using an APE1 antibody. The immune complex was incubated with increasing concentrations of purified, recombinant Bcl2 at 4 °C for up to 2 h, and proteins released from the complex were identified in the supernatant following centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min. Surprisingly, Bcl2 directly disrupts the APE1·XRCC1 complex in vitro because the addition of purified Bcl2 results in decreased levels of bound XRCC1 on beads and increased levels of nonbound XRCC1 in the supernatant (Fig. 5B). Functionally, the addition of increasing concentrations (0.1–5 ng/ml) of purified, recombinant Bcl2 protein to the nuclear extract(s) isolated from H1299 parental cells results in a dose-dependent reduction in the production of the cleaved fragments (i.e. 14-mer) with a gradual increase of the uncleaved 26-mer oligonucleotides (Fig. 5C). Thus, in addition to a direct binding to APE1, Bcl2-mediated attenuation of APE1 endonuclease activity may also occur, at least in part, through disrupting a functional APE1·XRCC1 association.

FIGURE 5.

Overexpression of Bcl2 in cells inhibits formation of the APE1·XRCC1 complex, and purified Bcl2 directly disrupts the APE1· XRCC1 interaction in association with inhibition of APE1 endonuclease activity in vitro. A, vector-only control cells or Bcl2-overexpressing H1299 cells were treated with NNK (5 μm) for 60 min and disrupted in 1% CHAPS lysis buffer. Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using an agarose-conjugated APE1 antibody. The APE1-associated XRCC1 and total APE1 were then analyzed by Western blot. B, the APE1·XRCC1 complex was co-immunoprecipitated from H1299 parental cells that express undetectable levels of endogenous Bcl2 using an agarose-conjugated APE1 antibody and incubated with increasing concentrations of purified Bcl2 (0.5–2 ng/ml) in 1% CHAPS lysis buffer at 4 °C for 2 h. The samples were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 min. The resulting supernatant and immunocomplex beads were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Bcl2 and XRCC1 that bound to APE1, total APE1, or nonbound XRCC1 present in the supernatant were then analyzed by Western blot. C, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extract isolated from H1299 parental cells in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations (0.1–5 ng/ml) of purified, recombinant Bcl2. APE1 endonuclease activity was analyzed by autoradiography. Lane 1 is the 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotide-only control without treatment.

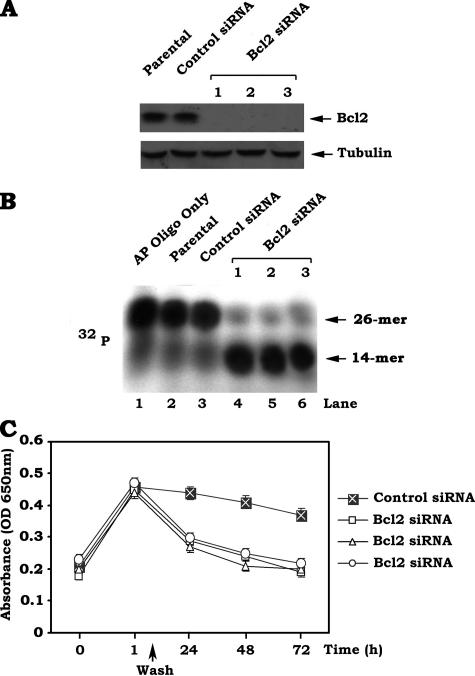

Specific Knockdown of Bcl2 Expression by RNA Interference Enhance APE1 Endonuclease Activity and Promotes AP Site Repair—To test a physiological role for Bcl2 in regulating APE1 activity and the repair of AP sites, a gene silencing approach was employed to specifically deplete the endogenous Bcl2 from H460 cells that express high levels of endogenous Bcl2. Recent studies have demonstrated that transfection of cells with siRNA concentrations greater than 100 nm frequently produces nonspecific off-target effects, and a concentration of 20–100 nm only occasionally produces off-target effects (23). However, siRNA concentrations of 10–20 nm generally do not exert nonspecific effects (24). To minimize nonspecific effects, we chose 10 nm of Bcl2 siRNA in the RNA interference experiment. The results reveal that transfection of Bcl2 siRNA significantly reduces the expression level of endogenous Bcl2 by more than 95% in H460 cells (Fig. 6A). This effect of siRNA on Bcl2 expression is highly specific because the control siRNA has no effect (Fig. 6A). Importantly, depletion of Bcl2 from H460 cells expressing high levels of endogenous Bcl2 up-regulates APE1 endonuclease activity (i.e. increased amount of the cleaved, 14-mer products) in association with accelerated AP site repair (Fig. 6, B and C). These findings provide strong evidence that physiologically expressed Bcl2 in cells is able to suppress AP site repair through a mechanism involving the inhibition of APE1 endonuclease activity.

FIGURE 6.

Depletion of endogenous Bcl2 expression by RNA interference results in elevated APE1 endonuclease activity and accelerated AP site repair. A, H460 cells expressing high levels of endogenous Bcl2 were transfected with Bcl2 siRNA (i.e. 10 nm) or control siRNA. Expression levels of Bcl2 were analyzed by Western blot. B, 32P-labeled 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotides were incubated with nuclear extract isolated from H460 parental cells or H460 cells expressing control siRNA or Bcl2 siRNA. APE1 endonuclease activity was analyzed by autoradiography. Lane 1 is the 26-mer AP site mimetic oligonucleotide-only control without treatment. C, H460 cells expressing control siRNA or Bcl2 siRNA were treated with NNK (5 μm) for 60 min. The cells were washed and incubated in regular culture medium for various times up to 72 h. AP sites were analyzed using an AP site counting kit. The data represent the means ± S.D. of three separate determinations.

DISCUSSION

One of the most prevalent lesions in DNA is the AP site, which is the product of DNA glycosylases and the first DNA intermediate in the process of BER. If left unrepaired, AP sites are potentially genotoxic and/or mutagenic (25). APE1, the second enzyme in BER pathway, initiates the repair of AP sites (22). Growing evidence indicates that Bcl2 can suppress the repair of various types of DNA damage, including AP sites of DNA lesions, in association with increased genetic instability (4, 10–13, 26). However, the molecular mechanism(s) by which Bcl2 regulates AP site repair remains elusive. Here we found that overexpression of Bcl2 suppresses APE1 endonuclease activity with decreased AP site repair (Fig. 2). Conversely, depletion of endogenous Bcl2 by RNA interference from H460 cells expressing high levels of endogenous Bcl2 enhances APE1 endonuclease activity in association with accelerated AP site repair (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that the inhibitory effect of Bcl2 on AP site repair may occur, at least in part, through down-regulating APE1 endonuclease activity.

Bcl2 is mainly localized in mitochondrial membranes to maintain the mitochondrial integrity. Mounting evidence indicates that Bcl2 has also been found in the nucleoplasm and functions within the nucleus (4, 19, 20). Intriguingly, the nuclear Bcl2 does not have antiapoptotic function but still has ability to regulate DNA repair (4). APE1 is mainly localized in the nucleus, but cytoplasmic APE1 can also be observed in some cell types (3). Here we found that NNK-induced DNA damage signal can stimulate Bcl2 accumulation in nucleus, which subsequently interacts with APE1 (Fig. 3). This may be a potential mechanism by which Bcl2 down-regulates APE1 activity with suppression of AP site DNA repair.

Bcl2 family members share homology in regions designated the BH domains BH1, BH2, BH3, and BH4 (21). Structure-function studies with Bcl2 deletion mutants reveal that APE1 directly interacts with Bcl2 and that all of the BH domains in Bcl2 are required for this interaction (Fig. 4, A and B). Because the BH1, BH2, and BH3 domains form the surface binding pocket of Bcl2 (27), our findings suggest that in addition to the BH4 domain, the integrity of the surface binding pocket of Bcl2 is also important for Bcl2 to associate with APE1. Functionally, deletion of any of the BH domains abolishes the capacity of Bcl2 to suppress APE1 endonuclease activity as well as AP site repair (Fig. 4), indicating that the physical Bcl2-APE1 binding is required for the effects of Bcl2 on APE1 and AP site repair.

XRCC1 acting as both a scaffold and a modulator of the different activities involved in BER provides a link between the incision and sealing steps of the AP site repair process. Intriguingly, XRCC1 not only physically interacts with APE1 but also potently stimulates its enzymatic activity (22). Because overexpression of Bcl2 in cells or the addition of purified Bcl2 to the APE1·XRCC1 complex directly disrupts APE1·XRCC1 association (Fig. 5), this supports the notion that the inhibitory effect of Bcl2 on APE1 function may result from its physical binding to APE1 and/or subsequent disruption of the APE1·XRCC1 complex.

In summary, our findings have uncovered a novel molecular mechanism by which Bcl2 suppresses AP site repair through inhibition of APE1 endonuclease activity. NNK-induced AP sites of DNA lesions facilitate Bcl2 accumulation in nucleus and interaction with APE1 via its BH domains, leading to decreased APE1 activity and attenuation of AP site repair. Because AP sites are mutagenic, Bcl2-mediated suppression of AP site repair may facilitate mutagenesis, genetic instability, and/or cancer development.

This work was supported by NCI, National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA112183, by a Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Clinical Innovator Award, and a Fu Rong Scholarship. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AP site, apurinic/apyrimidinic or abasic site; APE1, apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1; NNK, nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1y-butanone; BER, base excision repair; BH, Bcl2 homology; siRNA, small interfering RNA; WT, wild type; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; CHAPS, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid; ARP, aldehyde reactive probe.

References

- 1.Kelley, M., and Parsons, S. (2001) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 3 671-683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau, J., Weatherdon, K., Skalski, V., and Hedley, D. (2004) Br. J. Cancer 91 1166-1173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tell, G., Damante, G., Caldwell, D., and Kelley, M. (2005) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7 367-384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin, Z., May, W. S., Gao, F., Flagg, T., and Deng, X. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 14446-14456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xanthoudakis, S., Miao, G., and Curran, T. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91 23-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng, X., Gao, F., Flagg, T., Anderson, J., and May, W. S. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 4421-4434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng, X., Gao, F., Flagg, T., and May, W. S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 153-158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linette, G. P., Hess, J. L., Sentman, C. L., and Korsmeyer, S. J. (1995) Blood 86 1255-1260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsujimoto, Y., Cossman, J., Jaffe, E., and Croce, C. M. (1985) Science 229 1390-1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo, M., Shiah, S., Wang, C., and Chuang, S. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 55 894-901 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu, Y., Naumovski, L., and Hanawalt, P. (1997) Cancer Res. 57 1650-1653 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saintigny, Y., Dumay, A., Lambert, S., and Lopez, B. (2001) EMBO J. 20 2596-2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youn, C. K., Cho, H., Kim, S., Kim, H., Kim, M., Chang, I., Lee, J., Chung, M., Hahm, K., and You, H. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7 137-147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou, Y., Gao, F., Wang, Q., Zhao, J., Flagg, T., Zhang, Y., and Deng, X. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 9279-9287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorquera, R., Castonguay, A., and Schuller, H. (1994) Carcinogenesis 15 389-394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mijal, R., Thomson, N., Fleischer, N., Pauly, G., Moschel, R., Kanugula, S., Fang, Q., Pegg, A., and Peterson, L. (2004) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 17 424-434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hockenbery, D., Nunez, G., Milliman, C., Schreiber, R., and Korsmeyer, S. (1990) Nature 348 334-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu, W., Cowie, A., Wasfy, G., Penn, L. Z., Leber, B., and Andrews, D. (1996) EMBO J. 15 4130-4141 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoetelmans, R., van Slooten, H., Keijzer, R., Erkeland, S., van de Velde, C., and Dierendonck, J. (2000) Cell Death Differ. 7 384-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schardle, C., Li, S., Re, G., Fan, W., and Willinghamm, M. (1999) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 47 151-158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelekar, A., and Thompson, C. (1998) Trends Cell Biol. 8 324-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidal, A., Boiteux, S., Hickson, I., and Radicella, J. (2001) EMBO J. 20 6530-6539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullen, B. (2006) Nat. Methods 3 677-681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semizarov, D., Frost, L., Sarthy, A., Kroeger, P., Halbert, D., and Fesik, S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 6347-6352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loeb, L. (1985) Cell 40 483-484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chebonnel-Lasserre, C., Gauny, S., and Kronenberg, A. (1996) Oncogene 13 1489-1497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castelli, M., Reiners, J., and Kessel, D. (2004) Cell Death Differ. 11 906-914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]