Abstract

Caspase 8 is a critical upstream initiator of programmed cell death but, paradoxically, has also been shown to promote cell migration. Here, we show that tyrosine 380 in the linker loop of human caspase 8 is a critical switch determining caspase 8 function. Our studies show that, in addition to its cytosolic distribution, caspase 8 is recruited to lamella of migrating cells. Although the catalytic domain of caspase 8 is sufficient for recruitment and promotion of cell migration, catalytic activity per se is not required. Instead, we find that integrin-mediated adhesion promotes caspase 8 phosphorylation on tyrosine 380. Accordingly, mutation of this site compromises localization to the periphery and the potentiation of cell migration. Mechanistically, this linker region of caspase 8 acts as a Src homology 2 binding site. In particular, tyrosine 380 is critical for interaction with Src homology 2 domains. The results identify a novel mechanism by which caspase 8 is recruited to the lamella of a migrating cell, promoting cell migration independent of its protease activity.

Caspase 8 is an apical protease that is recruited to the death-inducing signaling complex following ligation of death receptors, such as CD95 (1). The activation of caspase 8 requires dimerization, which leads to cleavage of the procaspase 8 zymogen (2), and initiates the extrinsic apoptosis cascade. Accordingly, cells deficient in caspase 8 have severe defects in apoptosis in response to death receptor agonists (3, 4).

Initial evidence that caspase 8 had broader function than simply inducing apoptosis was provided by findings that caspase 8 knock-out mice are embryonic lethal due to defects in cardiac maturation (4). Subsequent studies using tissue-specific knock-out of caspase 8 have provided additional evidence. In the case of T cells, for example, alterations in proliferation and signaling have been observed (5–7). Caspase 8 expression has also been linked to integrin-mediated cell migration, with loss of caspase 8 being associated with defects in cell motility (8, 9).

We previously observed caspase 8 to be recruited to a complex with unligated integrins, leading to non-canonical activation of the procaspase zymogen (10). In contrast to these results, we reported that cell stimulation with survival-promoting growth factors such as epidermal growth factor led to Src-mediated phosphorylation of caspase 8 on tyrosine 380, inhibiting apoptotic function (11). Because epidermal growth factor and other growth factors are known to stimulate integrin-mediated cell migration as well as survival (12), we speculated that phosphorylation might act as a switch controlling caspase 8 function. Our studies revealed that tyrosine 380 was phosphorylated during integrin-mediated cell adhesion and, moreover, that mutation of this residue abrogated recruitment to lamellae and caspase-8 mediated promotion of cell migration. Mechanistically, tyrosine 380 appears critical for binding to Src homology 2 (SH2)2 domains, providing an explanation for recruitment of this procaspase zymogen to the membrane. The results may have important implications in cell fate determination among migratory cells in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Caspase 8 Expression—NB7 cells deficient in caspase 8 were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, glutamine, and minimal amino acids. Other cells were cultured in low glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented as described above. Human endothelial cells were cultured in M199 with endothelial cell supplement, 10% fetal bovine serum, minimal essential amino acids, and glutamine. DNA for caspase 8 was a gift from Guy Salvesen, The Burnham Institute for Medical Research. Full-length caspase 8-GFP, the Y380F (11) and C360A (13) mutants, and truncated GFP constructs were constructed as previously described (14). NB7 neuroblastoma cells deficient in caspase 8 (13) were transfected using the FuGENE reagent as described. Stable cell lines were selected by selection under G418 (500 μg/ml) and repeated FACs sorting for GFP-positive cells. Caspase 8 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting for caspase 8. Transient expression was performed by transfecting 1 μg of plasmid DNA cells as described.

Immunofluorescence Studies—Cells were permitted to attach to coverslips coated with fibronectin for 1 h, such that they were confluent. Cells were then wounded with a pipette tip and cells allowed to begin to migrate into the wound for 1 h. Alternatively, cells were plated at subconfluence and allowed to migrate randomly. In either case, cells were fixed and permeabilized in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Nonidet P-40-1% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and then blocked at room temperature for 90 min in the presence 3% BSA-PBS solution (PBS/BSA). Cells were then stained with polyclonal antibody to caspase 8 (BD Biosciences) (1:100) or polyclonal antibody specific for pY380 (1:100) (11) for 1 h. After washing several times in PBS/BSA, the cells were exposed to secondary antibody specific for rabbit (1:300)(Sigma). In some cases, cells were coincubated with TOPRO (500 ng/ml) to stain DNA and resolve nuclei. Samples were mounted and imaged on a Nikon cS1 confocal microscope.

Migration Assay—Twelve-well dishes were coated with 2 μg/ml of fibronectin overnight in PBS (pH 8.0). NB7 cells were allowed to attach for 2 h at confluent density (500,000 cells/well), and then monolayers were wounded twice with a conditioned pipette tip (1500-μm wounds) at 90° angles to generate a “cross-roads” wound. Six regions were measured microscopically, the wound was permitted to close for 20 h, the six regions were re-measured, and the mean wound closure calculated. The cross-roads assay permitted the same regions to be relocated and measured after the incubation period.

Immunoprecipitaiton and Immunoblot Analysis—Cells were lysed in complete radioimmunoprecipitation (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, and 1% Nonidet P-40 containing complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) as well as 50 mm NaF and 5 mm Na3VO4 centrifuged briefly to remove debris. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay. For immunoblot analysis, 25 μg of protein was boiled in Laemmli buffer and resolved on 10% gel. For immunoprecipitation analysis 500 μg of protein was incubated with 2 μgof specific antibody (BD Bioscience anti-caspase 8) or 2 μg of glutathione S-transferase-SH2 fusion protein for 1 h. Complexes were precipitated with 25 μl of protein A/G (Pierce) or glutathione beads (GE Healthcare), respectively. Beads were washed three times, eluted in boiling Laemmli buffer, and then resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Gels were immunoblotted with rabbit antisera to caspase 8 (1:2000; generated at the University of California San Diego) or Src 416 1:300 (Millipore) or with monoclonal antibody to GFP (Covance) or pY380 (11) as previously described (1:250).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Caspase 8 has previously been reported to promote cell motility (8, 9). To investigate this further, we used an immunofluorescence approach to determine the subcellular location of caspase 8 in a migrating cell. We noted that cells reconstituted for caspase 8 expression exhibited enhanced migration relative to cells lacking caspase 8 (8 supplemental material). By immunofluorescence analysis, we observed that caspase 8 was recruited to the leading lamellae or pseudopodia of migrating cells as they entered a wound (Fig. 1, A and B, wound is toward the top of the figure). The translocation to lamella or pseudopodia was not unique to the NB7 cell lines studied; it was found to translocate to the lamella among migrating carcinoma cells as well as normal endothelial cells attaching and spreading on extracellular matrix substrates (supplemental material).

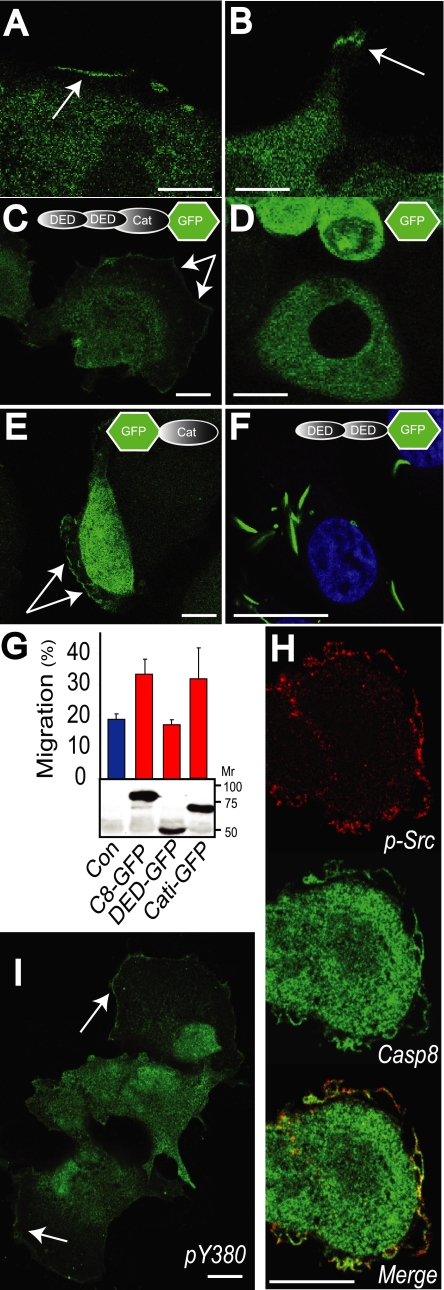

FIGURE 1.

Caspase 8 is recruited to the periphery of migrating and spreading cells. A and B, NB7 cells expressing caspase 8 were allowed to attach to a fibronectin substrate at confluence for 1 h, and the monolayer was wounded and cells allowed to migrate into the wound for a further 2 h. Cells were then fixed and stained for caspase 8 (green signal). To assess the localization of caspase 8 in live cells, caspase 8-GFP fusion proteins were expressed in caspase 8-deficient NB7 cells and imaged (green signal). The localization of full-length GFP-caspase 8 containing both death effector (DED) and catalytic (Cat) domains (C), the GFP protein alone (D), and the GFP-tagged inactive mutant of the catalytic domain C360A (E) are shown in live cells. F, cells expressing GFP-death effector domains were fixed in paraformaldehyde and stained with the nuclear stain TOPRO (blue signal) for contrast. G, the migration of NB7 cells expressing caspase 8 mutants into a wound was assessed after 20 h. Caspase 8-deficient NB7 cells or NB7 cells transiently expressing full-length GFP-caspase 8, GFP-death effector domains, or caspase 8 cells were seeded on a fibronectin substrate at confluence and wounded and the wound allowed to close for 20 h. Data shown are the means ± S.E. from six determinations in a representative assay. To confirm the expression of the caspase 8 constructs in the NB7 cells, lysates were separated via PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-GFP to resolve the GFP tag (lower panel). H, cells expressing the C8-GFP construct were fixed and stained for active Src using antisera to Src pY416 as a reporter (red channel). I, immunofluorescence staining for caspase 8 using pY380-specific antisera was performed in randomly migrating COS7 cells (green signal). The bars shown in each image A–F and H–I are 10 μm.

To extend and confirm these results, we constructed GFP-tagged caspase 8 proteins and reconstituted physiological levels of expression of these constructs in the caspase 8-deficient NB7 neuroblastoma cells. We observed localization of GFP-tagged caspase 8 to the lamellae (Fig. 1C) but no recruitment of GFP alone (Fig. 1D). Using the GFP-tagged truncation mutants, we observed that expression of the catalytic domain was sufficient for recruitment to lamella. However, caspase catalytic activity per se was not necessary for the localization, as a C360A mutant of caspase 8 that is enzymatically inert was recruited to membrane ruffles similar to the holoprotein (Fig. 1E). By contrast, GFP-tagged amino-terminal death effector domains did not localize to the periphery but instead were found to form “death effector filaments” in the cytosol, as previously reported (14) (Fig. 1F). Accordingly, expression of the catalytic domain promoted neuroblastoma cell migration, whereas expression of the death effector domains did not (Fig. 1G). The results are important, as the death effector domains are critical for interactions with the death-inducing signaling complex, downstream of the ligation of death receptors such as CD95 (1). In this case, however, recruitment of caspase 8 to the periphery via the catalytic domain would leave the death effector domains available to interact with other proteins. This may have important implications for regulating cell fate during cell migration.

We previously reported that stimulation of cells with epidermal growth factor leads to caspase 8 phosphorylation on tyrosine 380 by the kinase Src (11). Interestingly, among migrating cells, we observed co-staining of Src and caspase 8 in the leading lamellae, indicating that Src and C8 can selectively colocalize during cell migration (Fig. 1H). Extending this observation, we found a selective enrichment of phosphorylated caspase 8 at the leading edge of migrating cells using our pY380 antisera (11) (Fig. 1I). Consistent with our previous observations, no cleavage of caspase 8 was seen.

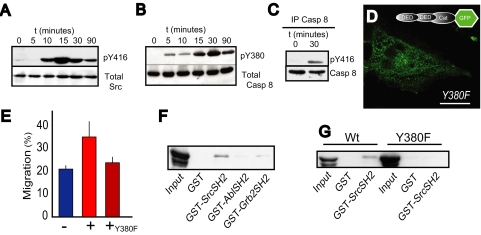

Integrin-mediated substrate attachment, and associated cell “spreading” via the extension of lamella, promotes Src activation (15) as well as the recruitment of caspase 8 to the periphery (supplemental material). Attachment leads to Src activation in the NB7 cells, as reported by antisera to pY416 in the Src kinase activation loop (Fig. 2A) (15). Therefore, we tested whether substrate attachment influenced caspase 8 phosphorylation on tyrosine 380. As shown (Fig. 2B), caspase 8 phosphorylation was observed in a time-dependent manner following fibronectin attachment but caspase 8 remained unphosphorylated in nonadherent cells (left lane). The data suggested that phosphorylation of Tyr-380 may be important for localization to the periphery. Consistent with this, attachment to a fibronectin substrate induced the formation of a co-precipitable Src- and caspase 8-containing complex that was absent among nonadherent cells (Fig. 2C). To evaluate the role of Tyr-380 more directly, we generated a GFP-tagged Y380F mutant refractory to Src phosphorylation (11) and examined its localization in NB7 cells. In contrast to wild-type caspase 8, Y380F did not efficiently localize to lamella (Fig. 2D) or promote migration (Fig. 2E). In agreement, Y380F caspase 8 did not associate with Src (11).3 The results together implicate Tyr-380 as a critical residue mediating caspase 8 recruitment to lamella leading to enhanced cell migration.

FIGURE 2.

Phosphorylated caspase 8 associates with Src via the SH2 domain. A, NB7 neuroblastoma cells were allowed to attach to and spread on fibronectin-coated surfaces, lysed, and subjected to immunoblot analysis for active Src using anti-pY416 antisera. B, similarly, NB7 cells stably reconstituted for caspase 8 were allowed to attach to fibronectin-coated surfaces and subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti pY380 antisera to detect phospho-caspase 8. C, cells were allowed to attach and spread on fibronectin substrate for 30 min and then lysed in radioimmune precipitation buffer and the complexes subjected to immunoprecipitation using monoclonal antibodies specific for caspase 8. Immunoprecipitated complexes were resolved on 10% SDS gels and subjected to immunoblot analysis using rabbit antisera to p416 (active Src) or caspase 8 to confirm the immunoprecipitation. D, NB7 cells were reconstituted with GFP-C8 bearing the Y380F mutant and allowed to attach to fibronectin-coated surfaces, and the localization of C8 was assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy. E, the NB7-Y380F cells were assessed for their capacity to migrate in a wounding assay, as described above. Data shown are the means ± S.E. from six determinations in a representative assay. F, human embryonic kidney cells expressing active Src kinase (Y527F) were transfected with caspase 8. Cells lysates were then subjected to pull down with 2 μg of GST-SH2 domains from Abl, Grb2, or Src to isolate the phospho-caspase 8. G, similarly, human embryonic kidney(Y527F) cells were transfected with either wild-type caspase 8 or the Y380F mutant and then subjected to pulldown analysis with the GST-SrcSH2 fusion protein, resolved on 10% SDS gels, and immunoblotted to detect caspase 8.

Tyrosine 380 is present within a linkage region in the catalytic domain of caspase 8, between the p10 and p18 subunits. The site is subject to proteolytic cleavage during caspase dimerization and the initiation of programmed cell death (2). No cleavage of caspase 8 is associated with recruitment to the membrane, suggesting that phosphorylation of Tyr-380 prevents caspase recognition of this site. Although our previous work supports the concept that Tyr-380 phosphorylation inhibits caspase 8 activation (11), this site is not located within either of the “caspase recognition” sites identified in the linker, and thus it seems unlikely to interfere with caspase recognition. However, phosphorylation-induced conformational changes could act distal to Tyr-380, preventing C8 activation or proteolysis. Alternatively, phosphorylation on Tyr-380 could promote interactions of this region of the caspase with other proteins, providing steric barriers to peptide cleavage.

The observation of the Src-caspase 8 complex supported the concept that caspase 8 could be sequestered within a signaling complex (Fig. 2C). Motif searches on caspase 8 revealed Tyr-380 as both a putative Src phosphorylation site (11) and a putative SH2 binding site (SEEQP-pYLEM DLSS). To directly test whether this region of C8 could interact with the SH2 domain of Src, we generated recombinant SH2 domains fused to GST for use in pulldown assays. Using this approach, we were able to isolate a caspase 8-containing complex associated with the Src SH2 domain (Fig. 2F). In contrast to Src, the SH2 domains of Abl and Grb2 were not able to pull down caspase 8. These results indicate that certain SH2 domains, such as that present in Src, can interact with caspase 8. To determine whether the putative binding site at Tyr-380 was necessary for this interaction, we next used the Src SH2 domain to probe lysates from target cells expressing wild-type or Y380F caspase 8. Although expressed at high levels, the Y380F mutant was not isolated in pulldown assays using the Src SH2 domain. Thus, consistent with our previous results implicating Tyr-380 in localization and cell migration, Tyr-380 is essential for interactions with SH2 domains.

Together, our studies identify Tyr-380 as a critical residue effecting interaction with SH2 domains, localization to the cell periphery, and promotion of cell migration. The phosphorylation of Tyr-380 may occur following epidermal growth factor stimulation or expression of active Src kinase (11), both of which are known to induce cell migration. However, here we show that phosphorylation also occurs spontaneously during cell attachment to substrate, consistent with integrin-mediated Src activation (15). Although inhibition of Src by expression of dominant negative variants or by pharmacological inhibitors blocks cell migration,4 this occurs in both C8-expressing and -deficient cell lines, consistent with multiple roles for Src in migration. However, it appears that the selective promotion of cell migration by caspase 8 requires the activity of Src or a Src family kinase.

Our results demonstrate association of the Src SH2 domain, but not the SH2 domains of Abl or Grb2, with caspase 8. The simplest model for C8-mediated enhancement of cell migration would be simply direct binding of caspase 8 to Src, thereby maintaining Src in an “open,” and therefore active, confirmation (16). However, we observe only a slight elevation of active Src in C8-expressing cells,3 and therefore we believe it is likely that caspase 8 may potentiate cell migration via other mechanisms. To this end, we expect that a methodical screen of SH2 domains that interact selectively with pY380 will be useful in further elucidating the mechanisms by which caspase 8 influences migration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Guy Salvesen and Jill Lahti for the gift of reagents.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by NCI, National Institutes of Health Grant CA107263 (to D. S.). This work was also supported by grants from the Italian Association for Cancer Research and the International Association for Cancer Research (AICR 07-0461) (to D. B.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement”in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: SH2, Src homology 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter.

D. Barilla, unpublished observations.

D. Stupack, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Muzio, M., Chinnaiyan, A. M., Kischkel, F. C., O'Rourke, K., Shevchenko, A., Ni, J., Scaffidi, C., Bretz, J. D., Zhang, M., Gentz, R., Mann, M., Krammer, P. H., Peter, M. E., and Dixit, V. M. (1996) Cell 85 817–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pop, C., Fitzgerald, P., Green, D. R., and Salvesen, G. S. (2007) Biochemistry 46 4398–4407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juo, P., Kuo, C. J., Yuan, J., and Blenis, J. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8 1001–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varfolomeev, E. E., Schuchmann, M., Luria, V., Chiannilkulchai, N., Beckmann, J. S., Mett, I. L., Rebrikov, D., Brodianski, V. M., Kemper, O. C., Kollet, O., Lapidot, T., Soffer, D., Sobe, T., Avraham, K. B., Goncharov, T., Holtmann, H., Lonai, P., and Wallach, D. (1998) Immunity 9 267–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang, T. B., Ben-Moshe, T., Varfolomeev, E. E., Pewzner-Jung, Y., Yogev, N., Jurewicz, A., Waisman, A., Brenner, O., Haffner, R., Gustafsson, E., Ramakrishnan, P., Lapidot, T., and Wallach, D. (2004) J. Immunol. 173 2976–2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su, H., Bidere, N., Zheng, L., Cubre, A., Sakai, K., Dale, J., Salmena, L., Hakem, R., Straus, S., and Lenardo, M. (2005) Science 307 1465–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arechiga, A. F., Bell, B. D., Leverrier, S., Weist, B. M., Porter, M., Wu, Z., Kanno, Y., Ramos, S. J., Ong, S. T., Siegel, R., and Walsh, C. M. (2007) J. Immunol. 179 5291–5300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helfer, B., Boswell, B. C., Finlay, D., Cipres, A., Vuori, K., Bong Kang, T., Wallach, D., Dorfleutner, A., Lahti, J. M., Flynn, D. C., and Frisch, S. M. (2006) Cancer Res. 66 4273–4278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnhart, B. C., Legembre, P., Pietras, E., Bubici, C., Franzoso, G., and Peter, M. E. (2004) EMBO J. 23 3175–3185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stupack, D. G., Puente, X. S., Boutsaboualoy, S., Storgard, C. M., and Cheresh, D. A. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155 459–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cursi, S., Rufini, A., Stagni, V., Condo, I., Matafora, V., Bachi, A., Bonifazi, A. P., Coppola, L., Superti-Furga, G., Testi, R., and Barila, D. (2006) EMBO J. 25 1895–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliceiri, B. P. (2001) Circ. Res. 89 1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stupack, D. G., Teitz, T., Potter, M. D., Mikolon, D., Houghton, P. J., Kidd, V. J., Lahti, J. M., and Cheresh, D. A. (2006) Nature 439 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel, R. M., Martin, D. A., Zheng, L., Ng, S. Y., Bertin, J., Cohen, J., and Lenardo, M. J. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141 1243–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitra, S. K., and Schlaepfer, D. D. (2006) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18 516–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Courtneidge, S. A. (1985) EMBO J. 4 1471–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.