Abstract

The coevolution of environment and living organisms is well known in nature. Here, it is suggested that similar processes can take place before the onset of life, where protocellular entities, rather than full-fledged living systems, coevolve along with their surroundings. Specifically, it is suggested that the chemical composition of the environment may have governed the chemical repertoire generated within molecular assemblies, compositional protocells, while compounds generated within these protocells altered the chemical composition of the environment. We present an extension of the graded autocatalysis replication domain (GARD) model—the environment exchange polymer GARD (EE-GARD) model. In the new model, molecules, which are formed in a protocellular assembly, may be exported to the environment that surrounds the protocell. Computer simulations of the model using an infinite-sized environment showed that EE-GARD assemblies may assume several distinct quasi-stationary compositions (composomes), similar to the observations in previous variants of the GARD model. A statistical analysis suggested that the repertoire of composomes manifested by the assemblies is independent of time. In simulations with a finite environment, this was not the case. Composomes, which were frequent in the early stages of the simulation disappeared, while others emerged. The change in the frequencies of composomes was found to be correlated with changes induced on the environment by the assembly. The EE-GARD model is the first GARD model to portray a possible time evolution of the composomes repertoire.

Keywords: compositional protocell, coevolution, environment, the GARD model, composomes

1. Introduction

All throughout the history of Earth, we can observe processes that change the environment. Such changes can be physical and abiotic, such as the complex feedback mechanisms that lead to the formation of the ice ages (Gildor & Tziperman 2000, 2003). Other environmental changes are caused by the activity of life: there are examples such as the oxygenation of the atmosphere through cyanobacterial photosynthetic activity 2.2 Gyr ago (Des Marais 2000; Catling & Claire 2005), or as recent as the effect of deforestation and usage of fossil fuel on atmospheric levels of CO2 (Houghton et al. 1999). Could protocells be involved in similar processes of environmental change?

The graded autocatalysis replication domain (GARD) model (Segre et al. 1998, 2000) is a quantitative and chemically realistic abstraction of a protocell, in accordance with the lipid world scenario to the origin of life (Segre & Lancet 2000; Segre et al. 2001a). The model tracks the dynamics of the composition of a non-covalent assembly of molecules. The assembly's composition changes due to joining of molecules into the assembly from its surrounding environment and to molecules leaving the assembly to the environment. A rudimentary progeny mechanism is modelled by a simplistic random fission of the assembly, in which each molecule in the assembly is assigned to one of two daughter assemblies with equal probability. An advanced variant of the model, polymer-GARD (P-GARD), also includes, in addition to the join and leave processes, possible production of oligomers within the assembly (Shenhav et al. 2005a).

One of the prerequisites for life is boundaries that separate living systems from the environment (Oparin 1953; Tawfik & Griffiths 1998; Szostak et al. 2001; Monnard & Deamer 2002; Hanczyc et al. 2003; Rasmussen et al. 2003). Most studies of protocellular entities are done in vitro. The nature of these studies, whether investigating possible mechanisms of cellular assembly or an attempt to create protocells in the laboratory, requires a fine tuning of the physical properties of the system. These properties include, for example, the permeability to building blocks, the tendency to grow or the capacity to split while maintaining their internal environment. The fine tuning is done by specific selection of the materials from which micelles or vesicles are made, and even the exact pH and temperature in which the experiments are conducted. The GARD model enables the analysis of a protocellular system, without exactly specifying the primary building blocks of the system. GARD studies employ computer simulations rather than in vitro experiments. Moreover, GARD uses a statistical chemistry approach (Segre & Lancet 1999) for deriving the chemical parameters of the simulation, which allows the use of abstract molecules rather than specific chemical compounds.

The study of the GARD model spans more than a decade. Its first embodiment has shown that simple protocells can undergo homeostatic growth based on kinetic control (Segre et al. 1998). Later, the amphiphile GARD (A-GARD) model, revealed that molecular assemblies, subjected to fission that keeps them out of equilibrium, may assume quasi-stationary compositions—composomes (Segre et al. 2000). Recent extensions to the GARD model include spatio-temporal investigation of multiple assemblies (Naveh et al. 2004; Shenhav et al. 2004), and studying the molecular network structure and dynamics that underlie the emergence of composomes (Shenhav et al. 2005b).

We have proposed that GARD protocells are mesobiotic entities—intermediates between prebiotic and fully-fledged living systems (Shenhav et al. 2003).

Here, using a novel extension of GARD, The environment exchange polymer-GARD (EE-GARD) Model, we examine the intricacy of coevolution of GARD protocells and their surrounding environment. This coevolutionary process shows that the repertoire of composomes manifested by a GARD assembly along many generations may change as a result of alteration of the surrounding environment, which is induced by the assembly.

2. Computational tools and methods

The simulations and all the analyses were conducted on a Pentium IV 2.8 GHz processor with Matlab v. 7.1. The simulations were implemented using the ‘direct method’ stochastic chemistry algorithm (Gillespie 1976, 1977), where equations (3.2a), (3.2b) and (3.4) were used to calculate the probabilities (rates) of the different possible reactions. The analyses made extensive use of routines (k-mean, silhouette, principal component, two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) provided in Matlab's Statistics Toolbox 5.2.

Classifying a trace of compositional vectors was conducted using a two-phase scheme. The first phase marks each generation as being in a drift (D) state, if its average similarity to its predecessor and successor is below 0.9, using H(n, n′)=(n·n′)/(‖n‖·‖n′‖) as measure for similarity between vectors n and n′. The second phase classifies to composomes the generations that are not marked as being in drift states. The classification is done by the following procedure.

Apply 100 times k-means clustering on the non-drift vectors with k=2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 and 12, using Matlab's ‘cosine’ distance measure.

For each k value, calculate the silhouette of the best result (the one with smallest sum of distances) using, again, Matlab's cosine distance measure.

Calculate the silhouette score for k=1, which is the average distance of the non-drift vectors from the mean of these vectors.

Find the best k value, i.e. k that has the highest silhouette.

Classify the non-drift generations according to the classifications of the best k-means result of the best k value.

k-Means clustering was also used to find the ‘change modes’ of the environment. For each generation, g, the vector Δe(g)=e(g+1)−e(g−1) represents the change in the composition of the environment. These change vectors were then classified 100 times using k-means clustering with k equal to the number of different composomes discovered in the specific run. The ‘change mode’ of each generation is its classification by the best k-means result (the one with smallest sum of distances).

3. The environment exchange polymer-GARD model

The A-GARD model (Segre et al. 2000; Shenhav et al. 2004) describes a single amphiphilic assembly in an environment containing a finite monomer repertoire of size NG. The internal molecular counts are (or in vector form ). Molecules join and leave the assembly with spontaneous rates kf and kb, which are typically taken to be equal for all molecular species. The model introduces mutually catalytic rate enhancements, exerted by molecules within the assembly on the join/leave reactions. Using a statistical chemistry approach (Segre & Lancet 1999), the values of the rate enhancement exerted by molecules of type j on molecules of type i (βi,j) are drawn from a lognormal distribution, which is an approximation of the receptor affinity distribution (Lancet et al. 1993; Rosenwald et al. 2002) modified for catalytic rate enhancement (Lancet et al. 1994; Segre et al. 2001b). The characteristic equations that describe an assembly's growth, in terms resembling continuous concentrations, are (Segre et al. 2000)

| (3.1) |

where N is the assembly size and ρ is the concentration of monomers in the external surroundings of the assembly. The equivalent rate equations for join (Ji) and leave (Li) reactions, which are used for simulations with discrete molecules, rather than molecular concentrations, are (Shenhav et al. 2004)

| (3.2a) |

| (3.2b) |

where ei is the tally of monomers in the environment near the assembly.

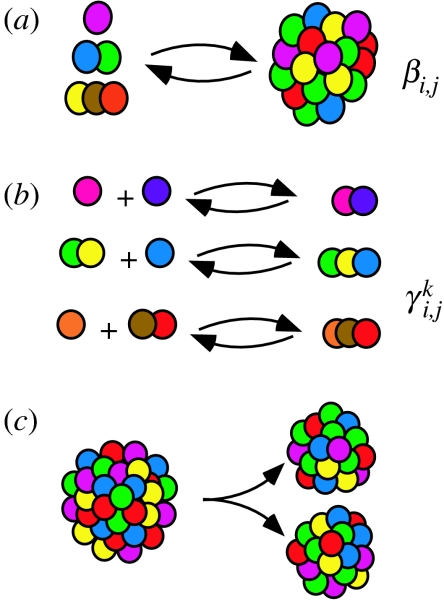

The P-GARD model (Shenhav et al. 2005a) also includes, in addition to the join and leave reactions of A-GARD (figure 1a), endogenously catalysed formation of covalent bonds between molecules within the assembly. That is, we also consider reactions of the form

| (3.3) |

where Ai and Aj are arbitrary molecular species (monomers or oligomers) present in the assembly and AiAj is the covalent oligomer formed from Ai and Aj (figure 1b). Similar to the join and leave reactions, there are basal rates for covalent bond formation (kpl) and bond dissociation reactions (kbr). We assume catalysis may be exerted on these reactions too, whereby the catalysing molecule may be any molecule (monomer or oligomer), Ak, present in the assembly. The catalytic coefficients specifying the degree to which a compound Ak catalyses the covalent association of Ai and Aj is denoted by . The rate equations for bond formation (Pi,j) reactions, acknowledging the discrete nature of molecules in the assembly, are

| (3.4) |

Figure 1.

The polymer-GARD model (P-GARD). The model consists of three different types of chemical process. (a) A non-covalent reaction of transfer of a molecule (join or leave) between the environment and an assembly. While in the model without polymers (A-GARD; Segre et al. 2000) this kind of reaction regards only monomers, P-GARD also includes the join and leave of oligomers. The join/leave reactions are assumed to be catalysed, in a graded fashion, by molecules in the assembly. The amount of catalysis exerted by a molecule of type j on the join/leave of a molecule of type i is βi,j. (b) Endogenous reaction of covalent bond formation between two molecules (monomers or oligomers) in the assembly. In the simulations described in the manuscript, the length of the oligomers is limited to up to three monomers, a trimer. That is, the formation of a dimer from two monomers, formation of a trimer from a dimer and a monomer or from a monomer and a dimer. In parallel to the catalysis of join/leave reactions, the polymerization reactions are assumed to be catalysed, also in a graded fashion, by molecules in the assembly. The amount of catalysis exerted by a molecule of type k on the formation of a covalent bond between molecules of types i and j is . (c) Fission (split) of the assembly to two daughter assemblies. P-GARD (like A-GARD) does not take into account the internal structure of the assembly. Thus, the fission is modelled by randomly assigning each molecule of the parent assembly to one of the daughter assemblies. The size of the assembly upon fission, in a realistic chemical scenario, is not strict and may depend on the assembly's structure and molecular components. Yet, in the model, for simplicity the assembly is assumed to split once it holds more than 2N0 molecules.

In previous work, the values of were derived from the values of βi,k and βj,k, suggesting a strong correlation between catalysis exerted on the non-covalent join/leave reaction and the catalysis on reactions of covalent bond formation/dissociation (Shenhav et al. 2005a). Here, we consider an alternative approach, whereby the values of are generated using a statistical chemistry approach as described for β.

Early version of P-GARD and most A-GARD simulations considered an assembly embedded in an infinitely large environment, such that the concentrations or tally of molecules surrounding the assembly are constant (buffered). The EE-GARD model presented here regards a finite environment, whereby molecules that join/depart the assembly affect the tallies ei of molecules in the environment.

As previously described (Segre et al. 2000, 2001b), a GARD assembly is assumed to undergo occasional fission, which serves as a rudimentary Oparin/Morowitz-style progeny mechanism (Oparin 1953; Oparin 1957; Morowitz 1967). For simplicity, the exact structure of the assembly is not modelled. Fission is assumed to happen when the size of the assembly (N) reaches a threshold value; that is, when the assembly just exceeds 2N0 molecules. In a fission (or split), the assembly is divided into two daughter assemblies, where each molecule of the parent assembly is assigned to one of the daughter assemblies with equal probability (figure 1c). While the decision to split is not stochastic, the size N exceeds 2N0, the fission process itself is stochastic with 50% probability for each molecule in the assembly to be allocated to each daughter assembly. Generally, in simulations of GARD, only one of the daughter assemblies, arbitrarily selected, is followed. In the case of infinite or constant environments, the other daughter assembly is ignored, whereas in the environment exchange case, the other progeny is presumed to disintegrate and its molecular constituents are added to the environmental tallies.

Forcing one of the progenies to disintegrate was introduced for practical reasons: a simpler model as well as a more computationally efficient simulation. Moreover, in a realistic scenario, disintegration of assemblies, not necessarily upon fission, or some other control mechanism on the population growth, is required in order to avoid exponential growth of the population. Future expansions of the model may, indeed, consist of populations EE-GARD assemblies following the preliminary studies with populations of GARD assemblies without polymers (Segre et al. 2000; Naveh et al. 2004; Shenhav et al. 2004). Accommodating for multiple assemblies in such future models is particularly important for studying possible coevolution of protocells rather than a single protocell and its environment.

4. Results

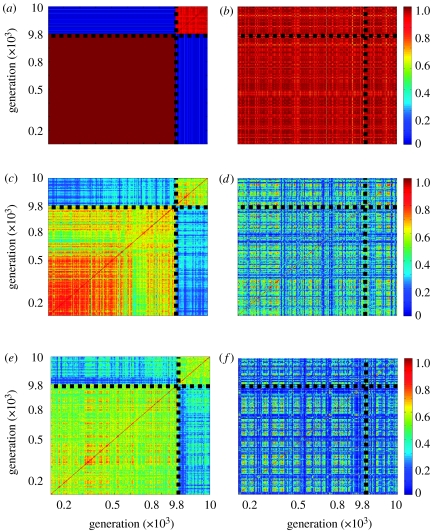

We have conducted two sets of 80 simulations, each 10 000 generations long, of an EE-GARD model restricted to oligomers with maximal length of three monomers. One set of simulations used a finite small environment, while the other, the control set, had an infinite supply of monomers in the environment (constant tally). The simulations in each set had the same parameters, but for a different random seed to create the β and γ values. Figure 2 shows time autocorrelation diagrams of the dynamic behaviour observed in these simulations. The long-term correlations seen in figure 2a,b indicate a strong quasi-stationary composition (composome) that prevailed for a long period. Such strong composomes were observed in approximately 10% of the simulations. For other sets of β and γ values (figure 2c–f), the composomes lasted several generations at most. This dynamic, observed here for trimers, is reminiscent of that previously reported for simulations limited to dimers only (Shenhav et al. 2005a). In simulations conducted with a finite environment (figure 2a,c,e), the compositional similarity within 800 early generations and within the 200 latest generations was much larger than the compositional similarity of these two periods towards each other. Notably, in the runs with an infinite environment (figure 2b,d,f), the similarity between the early and late periods was indistinguishable from the similarity within the periods.

Figure 2.

Compositional time autocorrelation diagrams (‘carpets’) of environmental exchange polymer-GARD model (EE-GARD). The drawing depicts the compositional dynamics for three different sets of β and γ catalytic rate enhancements (sets no. 37, 47 and 72), with (a,c,e) finite and (b,d,f) infinite environments. Each diagram portrays the correlation within early generations (100–900) and within late generations (9800–10 000) as well as the correlation between generations in these two periods. Intermediate generations (900–9800) are not shown in order to grasp the details in the short scale as well as the long-scale dynamics. Each point in the two-dimensional diagram is coloured by its correlation measure, H(ng, ng′), as defined in § 2, where ng and ng′ are the composition vectors at generation g and g′, respectively. The colour scale, signifying the range of H values, is shown on the right. Red indicates high correlation (H=1) and dark blue reflects low correlation (H=0). Red squares on the diagonal represent quasi-stationary compositions (composomes). In the simulations with a finite environment, the correlations between early and late generations are small (bluish rectangle), while in the simulations with an infinite environment the correlations between early and late generations are not different from the correlations within early or late generations. Each simulation used ten different monomer species (a total of 1110 different molecular species, including all possible 100 dimers and 1000 trimers). The initial tallies (total molecular counts) in the environment (ei) were 1000 monomers and zero dimers and trimers. These tallies were kept constant to imitate an infinite environment. The parameters of the simulation were: kf=10−2, kb=10−6, kpl=10−2, kbr=0 and N0=200.These constants were taken in order to facilitate the computational constraint and do not necessarily reflect a specific chemical scenario. The β and γ values were randomly picked from a lognormal distribution with μ=−4 and σ=4, which are suggested to be chemically realistic (Segre et al. 2000).

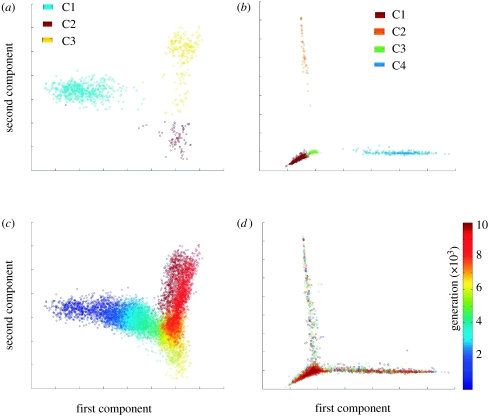

To objectively and automatically detect the composomes, each run was subjected to k-means clustering. Thus, each of the 10 000 generations in a compositional dynamics trace was classified as being in a particular composomal state, Ci, or in the drift state, D, where the assembly was not in any composomal state. We performed a principal component analysis of the composition vectors of the 10 000 generations. The projection of these vectors, to the plane that is defined by the first and second principal components, showed that in many of the runs these components separated the different composomes that emerged during the run (figure 3a,b). Using a colouring scheme based on the time course of the simulation, a clear association between the position of the projection and the generation is observed in the finite environment simulations (figure 3c), while with an infinite environment such association is not seen (figure 3d). This association implies that in the environmental exchange case the propensity to find a certain composome varies with time.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of P-GARD simulations. The diagrams show a projection of 10 000 composition vectors (each 1110 long) of the assembly, n(g) for a single P-GARD simulation to the plane that is defined by the two main components calculated by PCA (first component, abscissa; second component, ordinate). (a) Projection of the composition vectors in an EE-GARD simulation with a finite environment using β and γ set no. 47 (portrayed in figure 2c). The different colours indicate the different composome classifications (assemblies in drift state are not shown). The analysis shows separation between the three composomes. The first and second components capture 31 and 20% of the variance, respectively. (b) Same as (a) for the simulation with an infinite environment using β and γ set no. 72 (figure 2f). The first and second components capture 50 and 29% of the variance, respectively. (c) Same as (a) with a colouring scheme that reflects time progression rather than composome classifications (including generations in drift state). (d) Same as (b) with the colouring scheme of (c).

The repertoires of composomes manifested early (generations 100–1100) and late (generations 9000–10 000) in the simulations were compared, so as to assess the stability of these repertoires along the time axis. For the runs with an infinite environment, the null hypothesis that the two repertoires come from the same distribution had a p-value above 0.99 for 45 runs, and in none of the 80 runs this hypothesis could have been rejected with a p-value below 0.08, using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. This suggests that the repertoire of composomes manifested in a GARD system, without environmental exchange, is rather stationary over many generations. An opposite depiction emerged from similar analysis over the 80 runs with the environmental exchange (finite environment). For 60 runs, the null hypothesis that early and late repertoires are similar was in fact rejected (p-value below 0.08). Thus, EE-GARD shows a change in time of the repertoire of composomes.

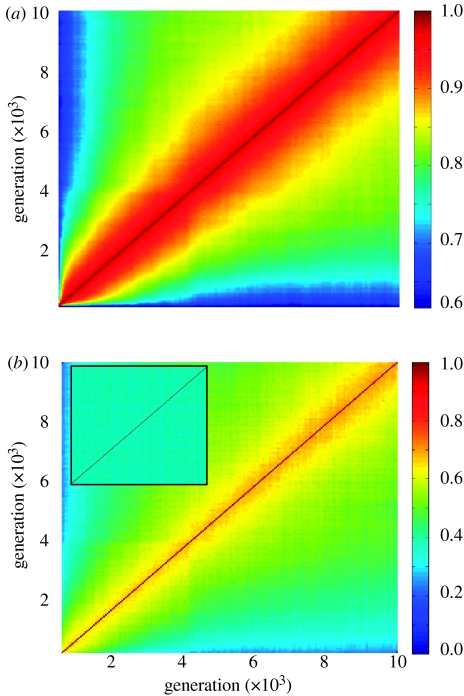

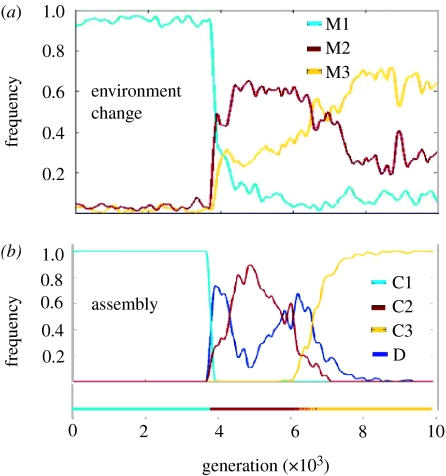

The dynamics of the composition of the environment was examined. Figure 4a portrays the average time autocorrelation diagrams of the chemical composition in the environment. It shows that typically the similarity between the environments in two generations, g1 and g2, decreases as the number of generations between g1 and g2 increases. The composition of the assembly in different generations (figure 4b) follows the same trend, where the internal similarity changes more rapidly and to a larger extent. This dynamic is different from the dynamics with an infinite environment, where the average similarity between the compositions in two different generations generally does not depend on the number of generations between these two generations (figure 4b, inset). We further explored the linkage between the composome state of the assembly and the change in the chemical repertoire of the environment, due to the environmental exchange with the assembly. The change in the environment, Δe(g), was estimated by the difference of the environment vectors of the predecessor, e(g−1), and the successor, e(g+1). The sequence of environmental changes was subjected to the same clustering procedure that was used for detection and analysis of composomes. That is, each of the 10 000 Δe(g) vectors was classified as being in a particular ‘change mode’, Mi. Figure 5a shows the frequency (as a function of time) of these modes. The frequencies of the composomes, which were seen during the same simulation, are shown in figure 5b. The time correlation between the frequencies of the environmental change modes and the frequencies of the composomes is significant (0.84 for M1–C1, 0.48 for M2–C2 and 0.29 M3–C3). This suggests that the change modes of the environment and the composome coevolve, where the environment induces the composomes in the assembly, while the composomes govern the change mode of the environment.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the average autocorrelation of the compositions in the environment (a) and within the assembly (b), over 80 simulations with different β and γ sets of EE-GARD with a finite environment. For each simulation, two autocorrelation diagrams, as described in figure 2, were generated. One autocorrelation diagram was based on the internal compositions of the assembly, and the other used the composition of the surrounding environment. The average of the 80 autocorrelation diagrams of the environment is portrayed in (a), and the average of the diagrams of the internal compositions is portrayed in (b). The correlations were calculated for every 50th generation, thus losing most of the local information, in order to get a broad view of all 10 000 generations. The inset in (b) shows the same analysis for the 80 simulations with an infinite environment.

Figure 5.

Frequencies of environment change modes and composomes. The diagram shows the frequencies (after lowess smoothing with a window of 301 generations) of the (a) change modes and (b) composomes as a function of the simulation progression for the simulation with a finite environment using β and γ set no. 37 (figure 2a). The frequencies of the change mode M1 and composome C1 have a high correlation (0.84). A certain degree of correlation is also seen between M2 and C2 (0.48) or M3 and C3 (0.29).

5. Discussion

We have suggested that GARD assemblies may constitute a crucial intermediate step towards fully-fledged living systems (Shenhav et al. 2003). The present study brings forth the issue of possible changes that such assemblies, which are possibly compositional protocells, may elicit in their environment and, in turn, the effect that such changes may have on the evolution of these protocells. We have devised the EE-GARD model, which includes a mechanism for generating novel molecular species within a protocell via oligomer formation, as well as an exchange of molecules between the protocell and its finite environment. We have shown that, without environmental exchange, GARD assemblies tend to have a steady repertoire of composomes over long periods of time. In contrast, in the presence of environmental exchange, the composome repertoire is not stationary, and changes over time are much longer than the typical composomal lifetime. This long-term change, which is observed here for the first time, may be considered an evolutionary process, whereby previously high-probability composomes disappear and other composomes emerge. Moreover, this evolutionary process corresponds to changes imposed on the environment by the GARD assembly. This implies that compositional protocells may coevolve with their environment.

The results of the present work go beyond the specific GARD embodiment. While compositional protocells were simulated here, other kinds of protocells or replicators, which have both a capacity to generate novel molecular species and a potential to exchange their content with the environment, may portray a similar dynamics. Such coevolution may be a key to more detailed future in silico studies of protocellular evolution.

Footnotes

One contribution of 13 to a Theme Issue ‘Towards the artificial cell’.

References

- Catling D.C, Claire M.W. How Earth's atmosphere evolved to an oxic state: a status report. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005;237:1–20. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.06.013 [Google Scholar]

- Des Marais D.J. Evolution—when did photosynthesis emerge on earth? Science. 2000;289:1703–1705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gildor H, Tziperman E. Sea ice as the glacial cycles' climate switch: role of seasonal and orbital forcing. Paleoceanography. 2000;15:605–615. doi:10.1029/1999PA000461 [Google Scholar]

- Gildor H, Tziperman E. Sea-ice switches and abrupt climate change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2003;361:1935–1942. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2003.1244. doi:10.1098/rsta.2003.1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie D.T. General method for numerically simulating stochastic time evolution of coupled chemical-reactions. J. Comput. Phys. 1976;22:403–434. doi:10.1016/0021-9991(76)90041-3 [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie D.T. Master equations for random walks with arbitrary pausing time distributions. Phys. Lett. A. 1977;64:22–24. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(77)90513-8 [Google Scholar]

- Hanczyc M.M, Fujikawa S.M, Szostak J.W. Experimental models of primitive cellular compartments: encapsulation, growth, and division. Science. 2003;302:618–622. doi: 10.1126/science.1089904. doi:10.1126/science.1089904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton R.A, Hackler J.L, Lawrence K.T. The US carbon budget: contributions from land-use change. Science. 1999;285:574–578. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.574. doi:10.1126/science.285.5427.574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet D, Sadovsky E, Seidemann E. Probability model for molecular recognition in biological receptor repertoires—significance to the olfactory system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:3715–3719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3715. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.8.3715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet D, Kedem O, Pilpel Y. Emergence of order in small autocatalytic sets maintained far from equilibrium—application of a probabilistic receptor affinity distribution (RAD) model. Ber. Bunsen-Ges. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1994;98:1166–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Monnard P.-A, Deamer D.W. Membrane self-assembly processes: steps toward the first cellular life. Anat. Rec. 2002;268:196–207. doi: 10.1002/ar.10154. doi:10.1002/ar.10154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morowitz H.J. Biological self-replicating systems. In: Snell F.M, editor. Progress in theoretical biology. vol. 1. Academic Press; London, UK: 1967. pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, B., Sipper, M., Lancet, D. & Shenhav, B. 2004. Lipidia: an artificial chemistry of self-replicating assemblies of lipid-like molecules. In Proc. Artificial Life IX, Boston, MA, USA, pp. 466–471.

- Oparin, A. I. 1953 The origin of life (Transl. S. Morgulis), 2nd edn. New York, NY: Dover Publications.

- Oparin, A. I. 1957 The origin of life on the earth (Transl. A. Synge). London, UK: Oliver and Boyd.

- Rasmussen S, Chen L.H, Nilsson M, Abe S. Bridging nonliving and living matter. Artif. Life. 2003;9:269–316. doi: 10.1162/106454603322392479. doi:10.1162/106454603322392479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald S, Kafri R, Lancet D. Test of a statistical model for molecular recognition in biological repertoires. J. Theor. Biol. 2002;216:327–336. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.2538. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2002.2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Lancet D. A statistical chemistry approach to the origin of life. Chemtracts Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999;12:382–397. [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Lancet D. Composing life. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:217–222. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd063. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvd063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Lancet D, Kedem O, Pilpel Y. Graded autocatalysis replication domain (GARD): kinetic analysis of self-replication in mutually catalytic sets. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 1998;28:501–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Ben-Eli D, Lancet D. Compositional genomes: prebiotic information transfer in mutually catalytic noncovalent assemblies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:4112–4117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4112. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.8.4112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Ben-Eli D, Deamer D.W, Lancet D. The lipid world. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2001a;31:119–145. doi: 10.1023/a:1006746807104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre D, Shenhav B, Kafri R, Lancet D. The molecular roots of compositional inheritance. J. Theor. Biol. 2001b;213:481–491. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav B, Segre D, Lancet D. Mesobiotic emergence: molecular and ensemble complexity in early evolution. Adv. Complex Syst. 2003;6:15–35. doi:10.1142/S0219525903000785 [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav, B., Kafri, R. & Lancet, D. 2004. Graded artificial chemistry in restricted boundaries. In Proc. Artificial Life IX, Boston, MA, USA, pp. 501–506.

- Shenhav B, Bar-Even A, Kafri R, Lancet D. Polymer GARD: computer simulation of covalent bond formation in reproducing molecular assemblies. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2005a;35:111–133. doi: 10.1007/s11084-005-5578-z. doi:10.1007/s11084-005-5578-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenhav B, Solomon A, Lancet D, Kafri R. Early systems biology and prebiotic networks. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005b;3380:14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Szostak J.W, Bartel D.P, Luisi P.L. Synthesizing life. Nature. 2001;409:387–390. doi: 10.1038/35053176. doi:10.1038/35053176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik D.S, Griffiths A.D. Man-made cell-like compartments for molecular evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:652–656. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-652. doi:10.1038/nbt0798-652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]