Abstract

Study Objectives:

Chronic primary insomnia has been hypothesized to result from conditioned arousal or the inability to initiate normal sleep processes. The event-related potentials (ERPs) N1, P2, and N350 are useful indexes of arousal. The objective is to compare these ERPs in primary chronic psychophysiological insomniacs (INS) and good sleepers (GS) during multiple recordings.

Participants:

Participants were 15 INS (mean age = 46 years, SD = 7.5) and 16 GS (mean age = 37 years, SD = 10.1).

Methods and Procedure:

Following a multistep clinical evaluation, INS and GS participants underwent 4 consecutive nights of PSG recordings (N1 to N4). ERPs were recorded on the 3rd and 4th nights in the sleep laboratory (N3 and N4). ERPs recordings were made during wake on both nights (in the evening and upon awakening), with the addition of sleep-onset recordings on N4. Auditory stimuli consisted of “standard” and “deviant” tones.

Statistical Analysis:

Repeated measures ANOVAs were computed for each ERP for each recording for each type of stimulus.

Results:

The amplitude of P2 and N350 was greater for the deviant than for the standard stimulus in both groups. The amplitude of N1 was larger in INS than GS in the morning and the evening. While the amplitude of N350 was larger in GS than in INS at sleep onset, the amplitude of P2 was greater in INS than in GS at that time.

Conclusion:

Signs of greater cortical arousal in psychophysiological insomnia individuals are observed, especially upon awakening in the morning. However, at sleep onset, difficulties from disengaging from wake processes and some inability at initiating normal sleep processes appear also present in individuals with insomnia compared to good sleepers.

Citation:

Bastien CH; St-Jean G; Morin CM; Turcotte I; Carrier J. Chronic psychophysiological insomnia: hyperarousal and/or inhibition deficits? An ERPs investigation. SLEEP 2008;31(6):887-898.

Keywords: Psychophysiological insomnia, arousal, inhibition, event-related potentials, wake, sleep onset, sleep

RECENT EPIDEMIOLOGICAL REVIEWS INDICATE THAT BETWEEN 30% AND 48% OF ADULTS COMPLAIN OF INSOMNIA SYMPTOMS,1 WHILE CLOSE TO 10% SUFFER of an insomnia syndrome (severe and chronic insomnia complaints).2 Although many precipitating factors3 and maintaining factors4 have been suggested, the underlying cortical mechanisms linked to the perpetration of chronic insomnia remain poorly understood.

The neurocognitive model5 suggests that insomnia sufferers developed conditioned cortical arousal from the association of sleep related stimuli and encountered sleep difficulties. High cortical arousal would be present at the peri-onset of sleep and persist during sleep and be one of the perpetrating factors of chronic insomnia. Providing empirical evidence to this theory, recent studies using spectral analysis (PSA) have shown that β activity is increased in primary insomnia relative to good sleepers, both around the sleep-onset period and during NREM sleep.6–9 These findings, which are not always correlated with impairments of the macrostructure of sleep, are nevertheless consistent with psychological findings that insomniacs are hypervigilant and ruminative at night10–12 and with the presumed contributing role of attentional processes and information processing factors to insomnia.13

On the other hand, a second theory, the psychobiological model, put forward by Espie,14 suggests that high cortical arousal in insomnia sufferers may not be sufficient to maintain sleep difficulties. Rather, processes such as the inhibitory influence of attention and intention on “normal sleep processes” would deregulate and breach the automaticity of normal unattended sleep initiation. Alternatively, it would be an inability to de-arouse or disengage from active wake processing that interferes with the normal initiation of sleep processes in insomnia sufferers. Thus higher cortical arousal might be present at any time before sleep onset and during the night, but another process, inhibition of arousal, might be absent or deficient as insomnia sufferers attempt to fall asleep or return to sleep during the night. Although high cortical activity, as measured with PSA, has been reported in chronic insomnia sufferers, less is known about the hypothesized possible de-arousal deficiency in insomnia sufferers.

Few experimental designs have been aimed at eliciting or measuring on-going arousal and/or inhibition processes, in individuals with insomnia. Studies have generally failed to find differences between insomnia individuals and good sleepers on physiologic measures.14,15 Studying insomnia individuals and good sleepers during a 24-h period, Bonnet and Arand16 observed higher physiologic activation level in various autonomic measures in insomnia individuals relative to good sleepers both prior to and during sleep. More recently, Marchetti and colleagues17 used a very elegant design (Induced Change Blindness protocol-ICB) and have reported that individuals suffering from psychophysiological insomnia show attention biases, detecting faster changes in sleep related stimuli (having quicker reaction time) compared to good sleepers and delayed sleep phase syndrome individuals. Although these authors pointed out that it remains uncertain if attention biases are solely due to generalized cognitive arousal in insomnia or if they reflect distress and preoccupation markers specific to sleep disorders, these results support the presence of cognitive arousal processes in insomnia and suggest, to some extent, that some inhibition processes might be deficient in sleep disorders suffering individuals. Although reaction time may reflect actual cognitive arousal, the cortical processes linked to this ‘arousal’ remain unconfirmed and unknown. Furthermore, empirical evidence supporting deficits in cortical inhibition in insomnia individuals compared to good sleepers is still very limited.

By recording electrical activity elicited on the scalp, event-related potentials (ERPs) offer high temporal resolution (about 0.1 ms). This technique provides information about the precise timing of dynamic neural mechanisms of different cognitive processes. ERPs are recognized as sensitive indices of vigilance,18 i.e. as measures of attention and inhibition of information processing in wake and sleep. In that regard, the “N1-P2” complex (respective latency of about 100 and 200 ms after stimulus onset) is greatly influenced by the attention of the participant. During wake, as an individual is attentive to the presentation of auditory stimuli, a large N1 and a small P2 can be observed. From wake to sleep, as one is less attentive, the amplitude of N1 usually decreases and the amplitude of P2 usually increases. It has also been shown that P2, following non-target stimuli, increases with age, suggesting it may represent an inability to inhibit or withdraw attention from irrelevant stimuli.19 At sleep onset, a negative wave peaking at about 350 ms (N350) appears and is related to the normal initiation of sleep processes.18 Although the N350 is part of the K complex20–22 and can also be overlapped with vertex sharp waves,21 it also appears independently of these events. As such, at sleep onset, in the absence of K complexes and vertex sharp waves, the presence of N350 usually reflects the inhibition of information processing, the inhibition of cortical arousal.

Using an oddball paradigm, recent preliminary studies from Devoto et al.23,24 suggested a state of hyperarousal in insomnia individuals compared to good sleepers. More recently, Sforza and Haba-Rubio,25 with a similar paradigm, did not observe any signs of hyperarousal, from evening to morning, in insomnia individuals relative to good sleepers. While participants were instructed to pay attention to the auditory stimulation (target stimuli generating a “P3”), hyperarousal would equally, if not most likely, be measured with nonpertinent stimuli or while individuals are asked to ignore or to not pay attention to the stimulation. Surprisingly, up to now, little effort has been made at studying the information processing linked to nonpertinent, standard stimuli. Although very informative, previous ERPs protocols did not measure signs of inhibition in the on-going level of information processing of insomnia sufferers. In addition, limited single daily recordings (evening and/or morning) were usually used. Cortical activity, just like sleep onset and sleep, is a dynamic process, not a static one. Repeated recordings are thus essential to capture the variability linked to this activity.

The objectives of the present study were to use the ERPs oddball paradigm protocol to study the behaviors of the N1, P2, and N350 waves in response to both standard and deviant stimuli during wake (evening and morning) and sleep onset in chronic insomnia sufferers and good sleepers. ERPs recordings took place on 2 consecutive days. Cortical activity was assessed as nonpertinent stimuli were presented; participants received the instruction to ignore the presentation of auditory stimuli.

Two general hypotheses were formulated: (1) if insomnia individuals show signs of hyperarousal, they should display a larger N1 and a smaller P2 to standard and deviant stimuli compared to good sleepers; (2) if insomnia individuals have difficulties inhibiting cortical arousal, a smaller N350 will be observed at sleep onset in these individuals relative to good sleepers.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 31 adults, including 15 individuals suffering from chronic insomnia (10 men and 5 women; 46.3 y [7.6]) and 16 self-defined good sleepers (6 men and 10 women; 36.8 y [10.2]). Participants had a mean age of 41.4 y (SD = 10.1; range = 25 to 55 y). Participants had a mean education level of 14.0 y (SD = 3.9) and were predominantly married (61.3%). The majority of participants were employed (87.1%). The mean duration of insomnia was 11.6 y (SD = 9.8) for the insomnia sufferers group.

Good Sleepers (GS)

Participants included in the GS group reported being satisfied with their sleep and (a) did not have subjective complaints of sleep difficulties, (b) did not meet diagnostic criteria for insomnia, and (c) did not use sleep-promoting medication. They also had to report a sleep efficiency of 85% or more on the sleep diaries as well as no sleep difficulty of a higher level then “mild” on the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; score less than 8).

Insomnia Participants (INS)

The individuals suffering from chronic insomnia had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) presence of a subjective complaint of insomnia, defined as difficulty initiating (sleep-onset latency > 30 min) and/or maintaining sleep (time awake after sleep onset > 30 min) present at least 3 nights per week; (b) insomnia duration ≥ 6 months; (c) insomnia or its perceived consequences causing marked distress or significant impairment of occupational or social functioning (e.g., problem of concentration); and (d) presence of a subjective complaint of at least one negative daytime consequence attributed to insomnia (e.g., fatigue, mood disturbances). In addition to the above mentioned criteria, individuals with insomnia met the criteria for psychophysiological insomnia as described by Edinger and colleagues.26

Exclusion criteria for all participants were: (a) presence of a significant current medical (e.g., cancer, diabetes) or neurological disorder (e.g., dementia, Parkinson disease), which compromises sleep; (b) presence of a major psychopathology (e.g., major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders); (c) alcohol or drug abuse during the past year; (d) evidence of another sleep disorder such as sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index >15) or periodic limb movements during sleep (myoclonic index with arousal >15); (e) a score of 23 or higher on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)27; (f) use of psychotropic or other medications known to alter sleep (e.g., bronchodilators); and (g) use of a sleep-promoting agent (e.g., benzodiazepines). For the participants with insomnia, the criteria are consistent with those of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2)28 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)29 for chronic and primary insomnia.30 Participants of the INS group that used a sleep-promoting medication on occasional basis (≤twice a week) were enrolled in the study after a 2-week withdrawal period.

Recruiting, Screening, and General Procedure

All participants were recruited through newspaper advertisements. Following a telephone interview, eligible participants from both groups were mailed questionnaires aimed at evaluating the presence of psychological symptoms (BDI; Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI);27,31 sleep (2 weeks of daily sleep diaries); and severity of sleep disturbances (Insomnia Severity Index)12. Upon receipt of questionnaires, prospective participants were invited for a clinical interview at the research center. Upon arrival, informed consent was obtained. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I)32 and the Insomnia Diagnostic Interview (IDI)12 were then administered. These evaluations were conducted respectively by a clinical psychologist and a sleep specialist. After the clinical evaluation, included participants were further invited to undergo 4 consecutive nights of polysomnography (PSG) recordings at the sleep laboratory. Each participant received an honorarium for his or her participation in the study.

MATERIALS

Insomnia Diagnostic Interview

The Insomnia Diagnostic Interview12 is conducted in a semistructured format and assesses the presence of insomnia and potential contributing factors. It is designed to identify (a) the nature of the complaint, (b) the sleep–wake schedule, (c) insomnia severity, (d) daytime consequences, (e) the natural history of insomnia, (f) environmental factors, (g) medication use, (h) sleep hygiene factors, (i) the presence of other sleep disorders, (j) the patient's medical history and general health status, and (k) a functional analysis for antecedents, consequences, precipitating, and perpetuating factors.

Sleep Diary

The sleep diary12 is a daily journal used to assess subjective sleep quality. The various sleep-wake parameters derived for this study were sleep-onset latency (SOL); wake after sleep onset (WASO); early morning awakening (EMA); frequency of awakenings (FNA); total wake time (TWT); total sleep time (TST); time in bed (TIB); and finally, sleep efficiency (SE), defined as the ratio of TST divided by TIB, expressed as a percentage. The sleep diary is usually completed upon arising each morning for a 2-week baseline period in order to provide a stable index of sleep complaints.12 In addition, our participants completed the sleep diary each morning upon awakening in the sleep laboratory. A mean was calculated for each of the derived variables.

Insomnia Severity Index

The ISI12 is a reliable and valid brief self-report instrument that yields a quantitative index of perceived insomnia severity.33 The ISI comprises 7 items targeting the severity of sleep disturbances, the satisfaction relative to sleep, the degree of impairment of daytime functioning caused by the sleep disturbances, the noticeability of impairment attributed to the sleep problem as well as the degree of distress and concern related to the sleep problem. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, and the total score ranges from 0 to 28. A higher score reveals more severe insomnia. The ISI partly reflects the diagnostic criteria outlined in the DSM-IV.29

Polysomnographic (PSG) and Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) Recordings

Participants spent 4 consecutive nights in the sleep laboratory. Participants were instructed to arrive at the sleep laboratory at around 20:00 each night for electrode montage and preparation. Participants were asked to refrain from alcohol, drugs, excessive caffeine, and nicotine before coming to the laboratory. Bedtime was determined according to reported bedtime on the sleep diary. For all participants, lights-out was initiated after a biocalibration. Time in bed was determined according to usual time in bed of participants from the sleep diary, with no less than a fixed 8 h of PSG recordings.

A standard PSG montage was used, including electroencephalographic (EEG; including C3, C4, O1, O2, Fz, Cz, Pz), electromyographic (EMG; chin) and electro-oculographic (EOG; left and right supraorbital ridge of one eye and the infraorbital ridge of the other) recordings. This placement allowed for eye movement artifact and blinks to be subtracted from ongoing EEG.34 Electrodes were referred to linked mastoids with a forehead ground and inter-electrode impedance was maintained below 5 kOhms. In addition, respiration and tibialis EMG were monitored during the first night of PSG recording in order to rule out sleep apnea and periodic limb movements. Participants diagnosed with another sleep disorder were excluded and referred to an appropriate sleep specialist. A Grass Model 15A54 amplifier system (Astro-Med Inc., West Warwick, USA; gain 10000; band pass 0.3-100 Hz) was used. While PSG signals were digitized at a sampling rate of 512 Hz using commercial software product (Harmonie, Stellate System, Montreal, Canada), ERPs environment was controlled with the InstEP Systems (V4.2) using the same sampling rate. Sleep recordings were scored visually (Luna, Stellate System, Montreal, Canada) by qualified technicians according to standard criteria35 using 20-sec epochs. Reliability checks were conducted by an independent scorer to insure a minimum of 85% inter-scorer agreement. In addition of being the screening night for sleep disorders other than insomnia, Night 1 constituted an adaptation night. Clinical sleep data were derived from Nights 2 and 3. Auditory stimuli were presented within the hour before going to bed and 15 min after awakening on the 3rd and 4th PSG nights, as well as at sleep onset and all night long on the 4th night. Thus, the sequence of ERPs recordings was as followed: evening 3 (E3), morning 3 (M3), evening 4 (E4), sleep onset (SO) and finally, morning 4 (M4). The present study reports data on wake (evening and morning) and sleep onset ERPs recordings only.

Objective measures of sleep included were SOL (defined as the moment from lights off with the intention to sleep to the first consecutive minute of stage 2), WASO, TST, sleep efficiency (%; total sleep time/total recording time), and proportion (%) of stage 2, 3, 4, and REM latency to REM sleep.

ERPs Protocol

For the pairing of individuals as well as for calibration purposes, each participant received an audiometric evaluation establishing normal hearing levels (15 dB ISO; 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz). Auditory tone pips were presented trough ear inserts (« eartone inserts ») attached to auditory apparel « E-A-RTONE » from Auditory Systems, and their generation was controlled by the Presentation Software (Neurobehavioral Sciences).

Oddball: The N1, P2, and N350 waves were recorded with auditory stimuli consisting of a standard and a deviant tone. Standard stimuli had an intensity of 70 dB, a duration of 50 ms, a rise-and-fall time of 2 ms, a frequency of 2000 Hz, and a probability of 0.85. Deviant stimuli had an intensity of 90 dB, duration of 50 ms, a rise-and-fall time of 2 ms, a frequency of 1500 Hz, and a probability of 0.15. The inter-stimulus interval was kept constant at 2 sec. The oddball paradigm included 100 stimuli per block and 3 blocks of stimuli, for a total of about 9 min of stimulus presentation, were delivered during wake. At least one block of stimuli was delivered at sleep onset. Time between blocks varied between 1 min and 3 min. Again, during the presentation of tones, participants were instructed to completely ignore the tones and to not pay attention to them. During wake, participants were allowed to read a book/magazine during the presentation of the auditory tone pips. If excessive eye movements were displayed, the participants were instructed to stare at a fixed red line on the wall.

Data Analysis

Continuous EEG (Fz, Cz, and Pz sites) was recorded and stored for off-line analysis. ERPs collected in wake and sleep onset were averaged separately. Each ERP trial was binned according to stimulus category (standard and deviant) and then averaged off-line. Sweeps of 650 ms were reconstructed with 50 ms prior to stimulus onset (baseline) and 600 ms post stimulus onset for the detection of ERPs.

The amplitude and latency of N1, P2, and N350 were measured for each block of sound presentation for each stimulus (standard and deviant) at each time period. N1 was defined as the most negative peak between 60 and 110 ms after stimulus onset; P2 was defined as the most positive peak between 120 and 200 ms after stimulus onset; and N350 was defined as a negative peak appearing between 250 and 350 ms after stimulus onset. A particular attention was given to Cz, since all studied ERPs are usually maximum in amplitude at this site. The EEG was corrected for EOG artifacts and then averaged time-locked to the stimulus. Trials with remaining artifacts (e.g., eye movements; head or body movements; amplifier saturation) were rejected off-line during the averaging procedure (± 100 μV). Digital filtering was conducted with a band pass of 0.01-30 Hz for 12 dB. At sleep onset, any sweep containing high amplitude waves (e.g., vertex sharp waves), movement time or any sign of stage 2 sleep were excluded from further analysis and only artifact-free sweeps were included.

Statistical Analyses

First, one-way ANOVAs and chi-square were computed to compare groups on sociodemographic, psychological, and sleep characteristics. Then, a total of 6 repeated measures ANOVAs were performed. The first 4, including 3 within-subject factors (recording time, 5 levels; electrode site, 3 levels; auditory stimuli, 2 levels) and one between-subject independent factor (group, 2 levels), were computed on measures of N1 and P2 (amplitude and latency). Since N350 measures were taken only at sleep onset, the last 2 repeated measures ANOVAs performed on amplitude and latency values of this particular ERP included only 2 within-subject factors (electrode site, 3 levels; auditory stimuli, 2 levels) and one between-subject independent variable (group, 2 levels). When the sphericity condition was violated, a Greenhouse-Geisser correction to degrees of freedom was applied. To investigate 2- or 3-way significant interactions, simple effects tests were completed. Significance levels were set at 0.05 for the family of tests. To investigate specifically some hypotheses, paired-samples t-tests were performed for GS and INS independently to compare the effect of the deviant and standard stimulus on ERPs amplitude and latency (significance level set at 0.05). Then, other paired-samples t-tests were performed on both groups to measure the recording time effect on ERPs amplitude and latency. For these analyses, significance level was set at 0.05/10 = 0.005, since 10 simple effects were needed to decompose each 2-way interaction. Cohen's d was calculated for each statistical analysis in order to assess the magnitude of the effect of the results (d > 0.80 were considered as adequate).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Statistical analyses showed that INS and GS were similar according to gender, χ2(1, N=31) = 2.64, P = 0.10, but that GS were younger than INS, F1, 29 = 8.48, P < 0.01.

Because of this significant difference and because some authors have also suggested that the amplitude of ERPs (especially the P2) may be related to the age of participants,19 we investigated the inclusion of “age” as a covariate in the analyses to determine if this variable would impact further analyses. Frigon and Laurencelle36 argued that a significant difference between groups on covariate does not constitute a sufficient condition to include this covariate in the statistical model: rather it is its statistical contribution to the explanation of the dependent variable variance. Consequently, preliminary ANCOVAs with age were computed to investigate the statistical contribution of age. Results revealed for the 6 ANCOVAs (3 waves × 2 parameters) age was significant only for the latency of N350 (P = 0.04). All others P-values raged from 0.22 to 0.58 (M = 0.42). Since age could only affect between-groups hypothesis (within-groups and interaction not being affected by age adjustments) and the inclusion of a nonsignificant covariate reduces the statistical power of between-groups hypothesis, age was not included in the ANOVAs.

As expected, compared to GS, INS had higher scores on the ISI, F1, 29 = 84.00, P < 0.001, this higher score being indicative of greater severity of insomnia symptoms. Also, INS expressed more depressive and anxious symptoms as reported on the BDI, F1, 29 = 13.82, P = 0.001, and BAI, F1, 29 = 12.32, P < 0.01. Nonetheless, all participants remained under the clinical threshold for psychiatric syndrome. Compared to GS, INS reported lower SE, t15.00 = −5.83, P < 0.001, longer TWT, t16.25 = 5.19, P < 0.001, and shorter TST, t20.03 = −4.48, P < 0.001, on the 2 weeks of sleep diaries preceding the laboratory recordings. These results are depicted in Table 1. F and Ps could not be inserted in the table as many tests were used (chi square, F and T-tests).

Table 1.

Means (SD) of Sociodemographic Data of Insomnia Sufferers and Good Sleepers

| Insomnia sufferers n = 15 | Good sleepers n = 16 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 5 | 10 |

| Male | 10 | 6 |

| Age (years) | 46.27 (7.60)* | 36.81 (10.19) |

| Insomnia duration (months) | 138.80 (117.90) | |

| Education (years) | 13.80 (4.18) | 14.13 (3.72) |

| Questionnaires | ||

| ISI | 16.13 (4.69)** | 2.69 (3.42) |

| BDI | 7.20 (4.13)** | 2.44 (2.94) |

| BAI | 9.08 (7.43)** | 1.93 (2.49) |

| Sleep diaries (2 weeks) | ||

| SE | 71.04 (15.24)** | 94.38 (2.97) |

| TWT | 153.20 (87.62)** | 31.12 (25.71) |

| TIB | 502.15 (33.25) | 481.54 (43.00) |

| TST | 343.63 (86.69)** | 454.48 (42.34) |

Significant difference between INS and GS (P < 0.05).

Significant difference between INS and GS (P < 0.01).

Objective and Subjective Sleep Measures

Table 2 shows mean objective and subjective sleep measures for laboratory nights 2 and 3. Analyses revealed that INS and GS differed on all objective measures of SOL, WASO, TST, and SE. These results indicated that INS took longer to fall asleep, were awake longer after sleep onset, slept less and had a lower SE than GS. Similarly, on subjective measures, INS compared to GS had longer WASO, shorter TST, and lower SE, but both groups were equivalent on SOL. Concerning total time or proportion of sleep stages, the only between group difference was the total time spent in REM, GS spending more time in this stage than INS.

Table 2.

Means (SD) of Laboratory Sleep Parameters of Insomnia Sufferers and Good Sleepers

| INS | GS | F | P | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep diary | |||||

| SOL | 58.13 (104.59) | 13.56 (17.24) | 2.83 | 0.10 | 0.59 |

| WASO | 62.15 (69.90) | 13.84 (33.91) | 6.12 | 0.02 | 0.88 |

| TST | 317.58 (110.84) | 417.75 (44.34) | 11.18 | < 0.01 | −1.19 |

| SE (%) | 69.71 (23.68) | 92.23 (8.47) | 12.74 | 0.001 | −1.27 |

| PSG data | |||||

| SOL | 16.73 (19.41) | 6.38 (3.70) | 4.38 | 0.04 | 0.74 |

| WASO | 80.27 (41.68) | 28.92 (29.83) | 15.71 | < 0.001 | 1.42 |

| TST | 356.81 (38.87) | 403.92 (35.54) | 12.43 | 0.001 | −1.26 |

| SE (%) | 78.67 (9.72) | 91.41 (6.94) | 17.82 | <0.001 | −1.51 |

| Stage 1 | |||||

| Total time (min) | 18.27 (9.10) | 16.86 (9.94) | 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.15 |

| Proportion (%) | 5.24 (2.57) | 4.30 (2.82) | 0.94 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Stage 2 | |||||

| Total time (min) | 225.53 (39.07) | 246.99 (37.25) | 2.45 | 0.13 | −0.56 |

| Proportion (%) | 62.74 (6.87) | 61.01 (6.45) | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.26 |

| Stage 3 | |||||

| Total time (min) | 21.97 (15.96) | 33.44 (21.24) | 2.86 | 0.10 | −0.61 |

| Proportion (%) | 6.37 (4.89) | 8.27 (5.06) | 1.11 | 0.30 | −0.38 |

| Stage 4 | |||||

| Total time (min) | 3.32 (5.66) | 6.85 (9.00) | 1.68 | 0.20 | −0.47 |

| Proportion (%) | 0.97 (1.66) | 1.67 (2.23) | 0.97 | 0.33 | −0.36 |

| REM | |||||

| Total time (min) | 87.72 (17.74) | 99.78 (14.70) | 4.27 | < 0.05 | −0.74 |

| Proportion (%) | 24.66 (5.75) | 24.74 (3.78) | 0.002 | 0.96 | −0.02 |

INS = Insomnia sufferers, GS = Good sleepers, SOL = Sleep-onset latency, WASO = Wake after sleep onset, TST = Total sleep time, SE = Sleep efficiency.

ERPs Amplitudes

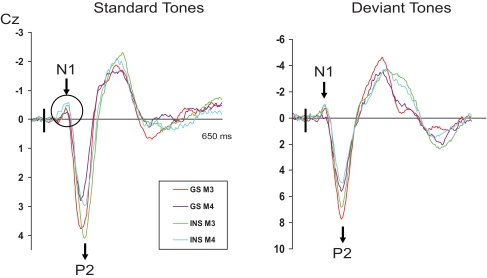

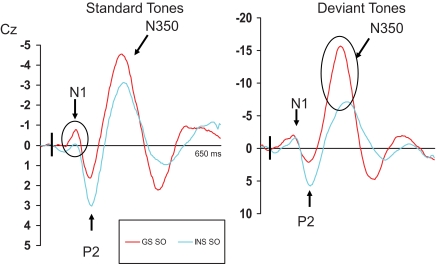

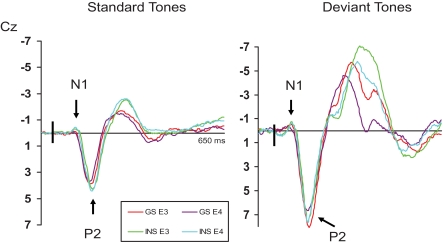

Repeated measures ANOVAS were computed on measures of amplitude of all 3 ERPs (N1, P2, and N350). Following the analyses of variance, when significant interactions including the independent variable “group” were found, simple effects were performed to reveal the between groups differences. The results of the different statistical analyses are provided in Table 3. Mean amplitudes of N1, P2, and N350 for both groups are displayed in Table 4. In addition, ERPs for INS and GS at Cz are illustrated in Figures 1 through 3, presenting data obtained on both mornings (Figure 1), on both evenings (Figure 2), and at sleep onset (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of Variance for ERPs Amplitude and Latency

| Source | df | Amplitude |

Latency |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | ||

| N1 | |||||

| Group (G) | 1 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 5.72 | 0.02 |

| Recording Time (R) | 4 | 4.44 | <0.01 | 5.00 | <0.01 |

| R × G | 4 | 2.35 | 0.06 | 1.27 | 0.29 |

| Electrode Site (E) | 2 | 7.14 | <0.01 | 1.76 | 0.19 |

| E × G | 2 | 3.65 | 0.03 | 1.73 | 0.20 |

| Auditory Stimuli (A) | 1 | 29.23 | <0.001 | 6.40 | 0.02 |

| A × G | 1 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.63 | 0.43 |

| R × E | 8 | 0.92 | 0.47 | 1.39 | 0.24 |

| R × E × G | 8 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.88 |

| R × A | 4 | 3.04 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.92 |

| R × A × G | 4 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 3.59 | 0.84 |

| E × A | 2 | 2.17 | 0.14 | 2.36 | 0.10 |

| E × A × G | 2 | 1.30 | 0.28 | 1.10 | 0.34 |

| R × E × A | 8 | 1.97 | 0.08 | 0.54 | 0.70 |

| R × E × A × G | 8 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 1.15 | 0.33 |

| Error | 1 | (7.06) | (1575.92) | ||

| P2 | |||||

| Group (G) | 1 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.07 | 0.79 |

| Recording Time (R) | 4 | 16.27 | <0.001 | 2.06 | 0.09 |

| R × G | 4 | 2.51 | <0.05 | 1.86 | 0.12 |

| Electrode Site (E) | 2 | 72.98 | <0.001 | 3.50 | 0.05 |

| E × G | 2 | 0.18 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.48 |

| Auditory Stimuli (A) | 1 | 117.05 | <0.001 | 2.53 | 0.12 |

| A × G | 1 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 5.94 | 0.02 |

| R × E | 8 | 3.41 | <0.01 | 1.77 | 0.15 |

| R × E × G | 8 | 1.50 | 0.16 | 1.88 | 0.07 |

| R × A | 4 | 3.22 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.40 |

| R × A × G | 4 | 3.18 | 0.02 | 1.30 | 0.28 |

| E × A | 2 | 21.00 | <0.001 | 1.52 | 0.23 |

| E × A × G | 2 | 2.07 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.83 |

| R × E × A | 8 | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.81 | 0.50 |

| R × E × A × G | 8 | 1.78 | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.77 |

| Error | 1 | (124.65) | (2917.18) | ||

| N350 | |||||

| Group (G) | 1 | 14.40 | 0.001 | 11.27 | <0.01 |

| Electrode Site (E) | 2 | 40.99 | <0.001 | 5.47 | 0.01 |

| E × G | 2 | 3.62 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.67 |

| Auditory Stimuli (A) | 1 | 144.85 | <0.001 | 4.51 | 0.04 |

| A × G | 1 | 19.05 | <0.001 | 5.53 | 0.03 |

| E × A | 2 | 21.80 | <0.001 | 0.05 | 0.95 |

| E × A × G | 2 | 8.03 | 0.001 | 0.69 | 0.50 |

| Error | 1 | (28.45) | (11000.87) | ||

Note. Values enclosed in parentheses represent mean square errors.

Table 4.

ERPs Mean (SD) Amplitude of Insomnia Sufferers and Good Sleepers

| Fz | N1 |

P2 |

N350 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Deviant | Standard | Deviant | Standard | Deviant | ||

| M3 | INS | −0.64 (0.50) | −1.05 (0.85) | 4.35 (1.52) | 6.98 (2.74) | ||

| GS | −0.42 (0.79) | −1.21 (1.13) | 4.20 (2.44) | 7.72 (2.78) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.33 | 0.16 | 0.07 | −0.27 | |||

| M4 | INS | −0.78 (0.47) | −0.65 (1.93) | 3.59 (1.68) | 6.37 (3.00) | ||

| GS | −0.53 (0.41) | −0.67 (1.08) | 3.03 (2.49) | 5.81 (3.87) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.57 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.16 | |||

| E3 | INS | −0.52 (0.69) | −1.18 (1.66) | 4.76 (1.76) | 6.89 (3.66) | ||

| GS | −0.39 (0.79) | −0.93 (1.75) | 4.58 (4.67) | 8.76 (4.65) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.17 | −0.15 | 0.05 | −0.45 | |||

| E4 | INS | −0.62 (0.63) | −0.94 (1.29) | 4.83 (1.55) | 7.66 (2.26) | ||

| GS | −0.47 (0.48) | −1.01 (0.71) | 4.38 (3.29) | 7.90 (4.01) | |||

| Cohen's d | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.85 | −0.07 | |||

| SO | INS | −0.43 (0.90) | −1.21 (1.78) | 3.34 (2.28) | 6.00 (3.10) | −2.85 (1.83) | −6.83 (3.47) |

| GS | −1.00 (0.82) | −1.88 (1.34) | 2.86 (2.57) | 4.91 (4.07) | −3.70 (2.02) | −10.67 (2.79)* | |

| Cz | |||||||

| M3 | INS | −0.72 (0.59) | −1.34 (1.07) | 4.41 (1.55) | 7.23 (2.48) | ||

| GS | −0.43 (0.78) | −0.89 (1.21) | 4.16 (2.46) | 8.09 (3.53) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.49 | −0.39 | 0.12 | 0.76 | |||

| M4 | INS | −0.84 (0.58) | −1.23 (1.46) | 3.57 (1.66) | 5.92 (2.90) | ||

| GS | −0.43 (0.27)* | 0.65 (1.17) | 3.00 (2.39) | 6.23 (4.13) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.91 | −0.44 | 0.28 | −.09 | |||

| E3 | INS | −0.49 (0.71) | −1.11 (10.42) | 4.60 (1.68) | 7.76 (3.18) | ||

| GS | −0.37 (0.75) | −0.75 (1.10) | 4.50 (2.54) | 9.00 (4.95) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.16 | −0.28 | 0.05 | −.30 | |||

| E4 | INS | −0.66 (0.57) | −1.30 (1.78) | 4.59 (1.67) | 7.99 (2.28) | ||

| GS | −0.33 (0.42) | −0.83 (0.84) | 4.25 (3.03) | 8.03 (4.25) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.66 | −0.34 | 0.14 | −.01 | |||

| SO | INS | −0.32 (1.04) | −1.89 (2.19) | 3.26 (2.24) | 6.22 (3.36) | −3.29 (2.06) | −8.44 (3.56) |

| GS | −0.94 (0.70)* | −2.49 (1.60) | 2.54 (2.90) | 3.91 (4.78) | −3.46 (2.03) | −16.07 (6.60)* | |

| Cohen's d | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.56 | 0.01 | −0.98 | |

| Pz | |||||||

| M3 | INS | −0.54 (.50) | −1.00 (1.15) | 2.56 (1.18) | 4.24 (1.97) | ||

| GS | −0.25 (0.48) | −0.44 (1.24) | 2.33 (1.51) | 5.16 (2.30) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.59 | −0.47 | 0.17 | −0.43 | |||

| M4 | INS | 0.65 (0.47) | −1.03 (1.41) | 1.98 (1.32) | 3.83 (1.98) | ||

| GS | −0.25 (0.30)* | −0.34 (1.20) | 1.81 (1.12) | 3.73 (2.56) | |||

| Cohen's d | −1.01 | −0.53 | 0.14 | 0.04 | |||

| E3 | INS | −0.40 (0.55) | −0.80 (1.65) | 2.65 (1.57) | 5.13 (2.07) | ||

| GS | −0.14 (.50) | −0.71 (.99) | 2.48 (1.52) | 5.38 (3.46) | |||

| Cohen's d | −0.49 | −0.07 | 0.11 | −0.09 | |||

| E4 | INS | −0.53 (0.40) | −1.08 (2.00) | 2.36 (1.37) | 4.76 (2.11) | ||

| GS | −0.08 (0.48)* | −0.62 (1.03) | 2.10 (1.19) | 4.56 (2.60) | |||

| Cohen's d | −1.02 | −0.29 | 0.20 | 0.08 | |||

| SO | INS | −0.45 (0.76) | −1.59 (1.68) | 1.77 (1.74) | 4.00 (2.98) | −1.96 (1.20) | −5.57 (2.50) |

| GS | −0.43 (0.69) | −1.88 (1.55) | 1.14 (1.16) | 1.38 (2.70)* | −2.60 (1.58) | −10.25 (4.10)* | |

| Cohen's d | −0.03 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.92 | 0.46 | 1.38 | |

INS = Insomnia sufferers; GS = Good sleepers.

Significant difference between INS and GS (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

ERPs results for good sleepers and psychophysiological insomnia sufferers during morning recordings. GS = Good sleepers; INS = psychophysiological insomnia sufferers; M3 = third morning of PSG recordings and first morning of ERPs recordings; M4 = fourth morning of PSG recordings and second morning of ERPs recordings. Significant between groups difference is illustrated with the black circle.

Figure 3.

ERPs results for good sleepers and psychophysiological insomnia sufferers during sleep-onset recordings. GS = Good sleepers; INS = psychophysiological insomnia sufferers; SO = sleep-onset recordings taking place on the fourth evening of PSG recordings. Between groups significant differences are illustrated with the black circles.

Figure 2.

ERPs results for good sleepers and psychophysiological insomnia sufferers during evening recordings. GS = Good sleepers; INS = psychophysiological insomnia sufferers; E3 = third evening of PSG recordings and first evening of ERPs recordings; E4 = fourth evening of PSG recordings and second evening of ERPs recordings.

N1

The repeated measures ANOVA on N1 amplitude values showed significant main effects of recording time, electrode site, auditory stimuli, and a significant Recording Time × Auditory Stimuli interaction. No significant effect of group was found but Electrode Site × Group interaction and Recording Time × Group interaction approached significance. Between-groups analysis showed that INS displayed a higher N1 amplitude than GS following a standard stimulus on E4 at Pz, F1, 29 = 7.97, P < 0.01; and on M4 at Cz, F1, 29 = 6.56, P = 0.02, and Pz, F1, 29 = 8.03, P < 0.01. On the other hand, the amplitude of N1 following a standard stimulus at SO at Cz was larger in GS than in INS, F1, 29 = 4.40, P = 0.04.

P2

As for N1, repeated measures ANOVAS on P2 amplitude resulted in significant effects for the recording time, electrode site, and auditory stimuli. Furthermore, Recording Time × Group, Recording Time × Electrode Site, Recording Time × Auditory Stimuli, Electrode Site × Auditory Stimuli, and Recording Time × Auditory Stimuli × Group interactions were significant. Simple effects revealed that the amplitude of P2 differed between the two groups only at SO following a deviant stimulus at Pz, F1, 29 = 6.58, P = 0.02, INS presenting a larger wave. On E4 at Fz following a standard stimulus, although the result approached significance, F1, 29 = 3.82, P = 0.06, the effect size obtained was large (d = 0.85) suggesting a larger amplitude in INS.

N350

Analyses on the amplitude of N350 at SO indicated significant results for all main effects, including groups, and all interactions. Analysis comparing groups showed that GS had a larger amplitude following a deviant stimulus at all 3 sites: Fz, F1, 29 = 11.58, P < 0.01; Cz, F1, 29 = 19.38, P < 0.01; and Pz, F1, 29 = 14.52, P < 0.01.

ERPs Latencies

For results of the repeated measures ANOVAs, see Table 3. Again, when significant interactions were found including “group” simple effects were used to assess differences between INS and GS.

N1

N1 latency varied between 61.07 and 82.81 ms. Analyses on latency measures of N1 revealed significant main effect for recording time, auditory stimuli, and group. No significant interactions were found. Therefore, INS generally had a longer N1 latency than GS.

P2

P2 latency varied between 123.83 and 147.27 ms. The latency of P2 presented no significant main effect although electrode site approached significance. Only one significant interaction was found, Auditory Stimuli × Group, resulting in a longer P2 latency in INS than GS following the standard tone but for the deviant one, GS presented the longest latency.

N350

The latency of N350 varied between 253.47 and 296.35 ms. Latency measures of N350 at SO showed significant results for main effects electrode site, auditory stimuli, and group. The Auditory Stimuli × Group interaction was also significant. The group effect generally indicates a longer latency in INS. Although, the significant interaction specifies that whereas the N350 latency of GS remains similar according to the type of stimulation, INS presented a longer latency following the deviant tone than the standard one.

Auditory Stimuli

Since the effect of “auditory stimuli” was significant in the previous analyses of amplitude and latency of ERPs, t-tests were performed on Cz values only to precise the differences between standard and deviant tones. In INS, the amplitude of N1 was influenced by the type of stimulus only on the third morning and evening, t14 = −2.52, P = 0.02 and t14 = −2.16, P < 0.05 respectively, and at SO, t14 = −2.82, P = 0.01, where the deviant tone produced a larger response compared to the standard one. Furthermore, all P2 and all N350 amplitude measures were significantly larger following the deviant stimulus compared to the standard one. For P2, analyses resulted in t values ranging from 3.43 to 8.31, P < 0.05; and for N350, t14 = −6.36, P < 0.001. Measures of latency of N1, P2 and N350 did not differ according to the type of stimulation in INS.

In GS, the amplitude of N1 differed according to the stimulation at SO only, t15 = −3.76, P < 0.01. The amplitude of P2 always differed, except for SO, with t values ranging from 5.96 to 8.89, P < 0.001. The amplitude of N350 also differed at SO, t15 = −9.49, P < 0.001. The differences constantly express a larger response for the deviant stimulus. The latencies of N1, P2, and N350 never differed according to standard or deviant stimuli in GS.

Recording Time

Evaluating if the response to the stimulation is maintained or fluctuates according to the recording time (for example, evening vs morning), t-tests on Cz values revealed within groups differences. Since N350 was recorded only at SO, it was not included in these analyses.

INS showed no difference in the amplitude of N1 according to the recording time. For P2 following the standard stimulus, the amplitude was significantly larger on the fourth evening than the subsequent morning, t14 = −4.53, P < 0.001. Differences in latency were noticed for N1 following a standard stimulus, E3, t14 = −3.49, P < 0.01; and M4, t14 = −4.46, P = 0.001, producing shorter latencies than SO. No differences were found between recording times for the latency of P2.

GS showed more differences of their response according to recording time. Following a deviant stimulus, the amplitude of N1 was larger at SO than on all the other recording times: M3, t15 = 3.80, P < 0.01; M4, t15 = 4.19, P < 0.01; E3, t15 = 4.66, P < 0.001; and E4, t15 = 3.68, P < 0.01. On the other hand, the amplitude of P2 was smaller at SO after a deviant tone compared to any other times, M3, t15 = 5.16, P < 0.001; M4, t15 = 3.80, P < 0.01; E3, t15 = 4.20, P < 0.01; and E4, t15 = 6.57, P < 0.001. Moreover, following a deviant tone, P2 was larger on the fourth evening than the next morning, t15 = −4.78, P < 0.001. In addition, following a standard stimulus, P2's amplitude was smaller at SO than on the third evening and morning, t15 = 3.60, P < 0.01 and t15 = 3.56, P < 0.01, respectively. Latency measures of N1 following a standard stimulus differed between E4 and SO, t15 = −4.08, P < 0.01, being longer at SO, whereas the latency of P2 did not differ.

DISCUSSION

As expected, psychophysiological insomnia sufferers showed more symptoms of depression and anxiety than good sleepers. Not surprisingly, between groups differences were also observed on objective measures of sleep onset, wake after sleep onset, total sleep time and sleep efficiency as well as on subjective measures of wake after sleep onset, total sleep time and sleep efficiency during the laboratory nights. In addition, subjective measures of sleep were closely corroborated by objective polysomnography. As such, insomnia sufferers took longer to fall asleep, were awake longer during the night and slept less than good sleepers, as they reported on sleep diaries. As our inclusion criteria for insomnia participants aimed at selecting only psychophysiological insomnia sufferers, our selection procedure appeared to be quite sensitive and reflecting the criteria set forward by Edinger et al.26

Event-Related Potential

N1 and P2 Main Results

Main results suggest that insomnia sufferers had larger N1 amplitude on the fourth morning and evening, and larger P2 amplitude at sleep onset, compared to good sleepers. The stimulus, standard or deviant, had no effect generally on N1 amplitude in both groups, even though the deviant tone produced larger P2 than the standard one. As for the latency measures of N1, insomnia individuals showed the longest latencies. However, the between group difference in the latency of P2 varied according to the stimulation, being longer in insomnia sufferers than controls following the standard stimulus and, following the deviant one, the relation was inverted.

Psychophysiological insomnia sufferers showed more signs of hyperarousal than good sleepers did. In that regard, the amplitude of N1 was larger in insomnia sufferers than in good sleepers. In addition, and surprisingly, hyperarousal was more present in the morning than in the evening (N1) in psychophysiological insomnia sufferers. While this observed increased hyperarousal in the morning might interfere with daily information processing and tasks (memory processes, attention), the lack of increased arousal during the evening appears to contradict previous literature. In that regard, the neurocognitive model5 suggests that high conditioned cortical arousal would be present at the peri-onset of sleep and persist during sleep. Although the N1 amplitude did not significantly differ at all times between good sleepers and psychophysiological insomnia sufferers, it was nonetheless consistently larger in the latter than in the former during evening and morning recordings. Recently, Yang and Lo37 observed a larger N1 in insomnia sufferers than in good sleepers during sleep. As such, hyperarousal appears to be present during sleep in insomnia individuals. In our study, N1 latency was longer in insomnia sufferers than in good sleepers. Usually a shorter latency is indicative of a greater disruption from the stimulus, this one being more intrusive.18 On the other hand, a longer latency from wake to sleep is usually observed in individuals and is indicative of sleep processes taking over wake processes. As such, even if good sleepers, according to N1 latency, appeared more disrupted by the stimulus than insomnia sufferers, the latency shift in N1 in insomnia individuals may indicate that these latter individuals appear to display usual signs of sleepiness. However, good sleepers show compensatory mechanisms that allow them not to be so disturbed by stimuli and disengage from wake to sleep processes as shown by the large N350. In that regard, N350 amplitude was always larger in good sleepers than in insomnia sufferers. Individuals with insomnia lack the inhibition mechanism usually associated with sleep, a large N350, even though they seemingly display some signs of sleepiness (delayed N1 during sleep onset).

Our results may suggest that hyperarousal might also express itself differently in the present study. Hyperarousal might be reflected through other information processing indices such as the amplitude of P2 during the evening or the morning. In that regards, the greater P2 amplitude in insomnia sufferers observed at these different recording times suggest that these individuals may have difficulties closing channels to nonpertinent stimulation. Similar results have been previously observed by Oades et al.38 in ADHD and Tourette disorders children, these authors suggesting that some enhanced information processing of nonpertinent stimuli is reflected through an increased in P2 amplitude. Although we certainly do not exert that insomnia sufferers and attention deficit/hyperactive individuals are alike, these two disorders might however share some features (reported lack of concentration and attention during the day, restlessness, and, of course, sleep difficulties); it might be that to a lesser extent, insomnia sufferers exhibit greater processing of nonpertinent stimuli. Our protocol was designed so that participants had to ignore all stimulation. We were aiming at targeting the processing of nonpertinent/irrelevant stimuli and how participants were able to withdraw their attention from these stimuli. The greater P2 observed in insomnia sufferers might thus represent the inability to discard irrelevant stimuli, irrelevant stimuli then interfering with the initiation or maintenance of sleep.

N350

Our results confirm the hypothesis that psychophysiological insomnia individuals do have difficulties inhibiting cortical arousal, smaller N350 at sleep onset being observed in these individuals relative to good sleepers. Furthermore, the amplitude of N350 remains unchanged from evening to sleep onset in psychophysiological insomnia individuals while it almost doubles from wake to sleep in good sleepers. Hull and Harsh39 had previously observed similar results while studying the amplitude of N350 during wake and at sleep onset in bad sleepers. These authors had suggested that bad sleepers had a decreased ability to inhibit cortical arousal during sleep onset. In accordance with Espie's theory,14 in addition to the presence of hyperarousal, an inability to de-arouse or disengage from active wake processing might interfere with the normal initiation of sleep processes in insomnia sufferers. As mentioned earlier, the presence of N350 at sleep onset, in the absence of K complexes and vertex sharp waves, usually reflects the inhibition of information processing, the inhibition of cortical arousal. Our results, like those of Hull and Harsh39 thus suggest that psychophysiological insomnia sufferers are unable to disengage from wake processes and inhibit further information processing (even though irrelevant such as the standard tone). This lack of inhibition might interfere with the initiation or maintenance of sleep. Thus, in addition to a state of hyperarousal, psychophysiological insomnia individuals also display signs of inhibitory deficits at sleep onset.

Recording Time or Multiassessment Protocol Results

The recording time had some impact on the amplitudes of ERPs within groups, and especially for good sleepers. In psychophysiological insomnia sufferers, P2 was larger on the fourth evening than the following morning after a standard stimulus. On the other hand, in good sleepers, larger N1 and smaller P2 were observed at sleep onset than at any other times for the deviant stimulus. Furthermore, following the standard stimulus, P2 was smaller at sleep onset than on the previous evening and following morning recordings. It thus appears that cortical arousal is more variable in good sleepers than in psychophysiological insomnia sufferers. Our results are in accordance with the observations of Sforza and colleagues25 who failed to observe any changes in cortical arousal from evening to morning in insomnia sufferers. It is possible that a complex state of hyperarousal interacting with inhibition deficits at sleep onset is always present in insomnia sufferers and is evidenced by the sleep quality of the previous night. In that regard, Devoto et al.23,24 reported that the amplitude of P300 varied with the quality of sleep in insomnia sufferers, they did not however compare morning recordings with evening ones. It is well known that the quality of sleep do affect information processing (for example, see deprivation study from Gosselin et al.40). Considering the variability in sleep patterns of insomnia sufferers and the subjective daily consequences reported, more sophisticated protocols and multiple objective recordings are required to determine the extent of quality of sleep on daily functioning. In that regards, our results surely suggest that multiple recordings are more adequate to capture and detect changes (even subtle ones) in cortical activity, in both good sleepers and insomnia individuals.

Conclusion

It appears that insomnia sufferers display both signs of hyperarousal and inhibition deficits at the peri-onset of sleep. Both cortical mechanisms may interact to interfere with sleep initiation. Further studies using larger samples, multi-assessment protocols such as ours and, targeting nightly awakening, could be informative on the interference of cortical arousal and inhibition deficits on the ability to return to sleep during the night. Other studies combining PSA and ERPs would also inform us on the cortical activity/activation in these individuals and especially for the sleep-onset period. This period, which was defined in the present study as the moment from lights off to the first consecutive minute of stage 2, could be adequately divided according to α and θ waves (stage 1a and 1b) to evaluate the impact of irrelevant stimulation on cortical activity during the progression from wake to sleep in insomnia individuals. Inhibition deficits at sleep onset or the inability to disengage could also translate in reported daily consequences, such as distraction and poor concentration. Elegant protocols such as the one used by Marchetti and colleagues17 coupled with ERPs protocols targeting inhibition and distraction during the day might also provide objective confirmation of such deficits. Furthermore, using the current protocol with paradoxical insomnia sufferers would help quantify suggested cortical activation in this group41 and help disentangle the respective features of both psychophysiological and paradoxical insomnia sufferers.

ABBREVIATIONS LIST

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- E3

evening 3

- E4

evening 4

- EEG

electroencephalography, electroencephalographic

- EMA

early morning awakening

- EMG

electromyographic

- EOG

electro-oculographic

- ERPs

event-related potentials

- FNA

frequency of awakenings

- GS

good sleepers

- ICB

induced change blindness

- ICDS-2

International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd ed.

- INS

primary chronic psychophysiological insomniacs

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- M3

morning 3

- M4

morning 4

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- PSA

power spectral analysis

- PSG

polysomnography, polysomnographic

- REM

rapid eye movement

- SCID-I

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

- SD

standard deviation

- SO

sleep onset

- SOL

sleep-onset latency

- TIB

time in bed

- TST

total sleep time

- TWT

total wake time

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (# 49500) and Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (4538) to C.H. Bastien.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Morin has received research support from Sanofi-Aventis, has participated in speaking engagements for Sanofi-Aventis and Takeda, and is on the advisory board of Neurocrine Biosciences, Sepracor, Takeda, Sanofi-Aventis, and Eli Lilly. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ohayon MM. Epidemiological of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Grégoire JP, Mérette C. Epidemiology of insomnia: Prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviours. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastien CH, Vallièeres A, Morin CM. Precipitating factors of insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2004;2:50–62. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0201_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morin CM, Espie CA. Insomnia: A clinical guide to assessment and treatment. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlis ML, Giles DE, Mendelson WB, Bootzin RR, Wyatt JK. Psychophysiological insomnia: the behavioural model and a neurocognitive perspective. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:179–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1997.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamarche CH, Ogilvie RD. Electrophysiological changes during the sleep onset period of psychophysiological insomniacs, psychiatric insomniacs, and normal sleepers. Sleep. 1997;20:724–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merica H, Blois R, Gaillard J. Spectral characteristics of sleep EEG in chronic insomnia. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:826–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlis ML, Smith MT, Andrews PJ, Orff H, Giles D. Beta/gamma EEG activity in patients with primary and secondary insomnia and good sleeper controls. Sleep. 2001;24:110–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastien CH, Bonnet MH. Do increases in beta EEG activity uniquely reflect insomnia? A commentary on “Beta EEG activity and insomnia”. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:377–79. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:869–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spielman AJ, Glovinsky P. The varied nature of insomnia. In: Hauri PJ, editor. Case studies in insomnia. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin CM. Psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. Insomnia. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacMahon KMA, Broomfield NM, Marchetti LM, Espie CA. Attention bias for sleep-related stimuli in primary insomnia and delayed sleep phase syndrome using the dot-probe task. Sleep. 2006;29:1420–1427. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espie CA. Insomnia: Conceptual issues in the development, persistence, and treatment of sleep disorders in adults. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:215–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mendelson WB, James SP, Garnett D, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE. A psychophysiological study of insomnia. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19:267–84. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. 24-hour metabolic rate in insomniacs and matched normal sleepers. Sleep. 1995;19:453–56. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.7.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchetti LM, Biello SM, Broomfield NM, MacMahon KMA, Espie CA. Who is pre-occupied with sleep? A comparison of attention bias in people with psychophysiological insomnia, delayed sleep phase syndrome and good sleepers using the induced change blindness paradigm. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:212–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell K, Colrain IM. Event-related potential measures of the inhibition of information processing: II. The sleep onset period. Int J Psychophysiol. 2002;46:197–214. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(02)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Larrea L, Lukaszewicz AC, Mauguiere F. Revisiting the oddball paradigm–nontarget vs neutral stimuli and the evaluation of ERP attentional effects. Neuropsychologia. 1992;30:723–41. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(92)90042-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bastien C, Campbell K. The evoked K-Complex – All-or-none phenomenon. Sleep. 1992;15:236–45. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastien CH, Crowley KE, Colrain IM. Evoked potentials components unique to Non-REM sleep: Relationship to evoked K-complexes and vertex sharp waves. Int J Psychophysiol. 2002;46:257–74. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(02)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colrain IM. The K-complex: A seven-decade history. Sleep. 2005;25:255–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devoto A, Violani C, Lucidi F, Lombardo C. P300 amplitude in subjects with primary insomnia is modulated by their sleep quality. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devoto A, Manganelli S, Lucidi F, Lombardo C, Russo PM, Violani C. Quality of sleep and P300 amplitude in primary insomnia: a preliminary study. Sleep. 2005;28:859–63. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.7.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sforza E, Haba-Rubio J. Event-related potentials in patients with insomnia and sleep-related breathing disorders: Evening-to-morning changes. Sleep. 2006;29:805–13. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, et al. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine work group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–96. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Classification of Sleep Disorders Diagnostic and Coding Manual (ICSD-2) Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lacks P, Morin CM. Recent advances in the assessment and treatment of insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:586–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–7. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, First M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bastien CH, Vallièeres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gratton G, Coles MGH, Donchin E. A new method for off-line removal of ocular artefact. Electrencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1983;55:468–84. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rechtschaffen A, Kales AA. Manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles: Brain Information/Brain Research Institute, UCLA; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frigon J, Laurencelle L. Analysis of covariance: a proposed algorithm. Educ Psychol Meas. 1993;53:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang C-M, Lo H-S. ERP evidence of enhanced excitatory and reduced inhibitory processes of auditory stimuli during sleep in patients with primary insomnia. Sleep. 2007;30:585–92. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oades RD, Diitman-Balcar A, Schepker R, Eggers C, Zerbin D. Auditory event-related potentials (ERPs) and mismatch negativity (MMN) in healthy children and those with attention-deficit or Tourette/tic symptoms. Biol Psychol. 1996;43:163–85. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(96)05189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hull J, Harsh J. Behavioral and ERP changes during the transition to sleep in good and poor sleepers. Sleep Res. 1994;23:221. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gosselin A, De Koninck J, Campbell K. Total sleep deprivation and novelty processing: implications for frontal lobe functioning. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:211–22. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krystal AD, Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Marsh GR. NREM sleep EEG frequency spectral correlates of sleep complaints in primary insomnia subtypes. Sleep. 2002;25:630–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]