Abstract

Small fibre neuropathy (SFN), a condition dominated by neuropathic pain, is frequently encountered in clinical practise either as prevalent manifestation of more diffuse neuropathy or distinct nosologic entity. Aetiology of SFN includes pre-diabetes status and immune-mediated diseases, though it remains frequently unknown. Due to their physiologic characteristics, small nerve fibres cannot be investigated by routine electrophysiological tests, making the diagnosis particularly difficult. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) to assess the psychophysical thresholds for cold and warm sensations and skin biopsy with quantification of somatic intraepidermal nerve fibres (IENF) have been used to determine the damage to small nerve fibres. Nevertheless, the diagnostic criteria for SFN have not been defined yet and a ‘gold standard’ for clinical practise and research is not available. We screened 486 patients referred to our institutions and collected 124 patients with sensory neuropathy. Among them, we identified 67 patients with pure SFN using a new diagnostic ‘gold standard’, based on the presence of at least two abnormal results at clinical, QST and skin biopsy examination. The diagnosis of SFN was achieved by abnormal clinical and skin biopsy findings in 43.3% of patients, abnormal skin biopsy and QST findings in 37.3% of patients, abnormal clinical and QST findings in 11.9% of patients, whereas 7.5% patients had abnormal results at all the examinations. Skin biopsy showed a diagnostic efficiency of 88.4%, clinical examination of 54.6% and QST of 46.9%. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis confirmed the significantly higher performance of skin biopsy comparing with QST. However, we found a significant inverse correlation between IENF density and both cold and warm thresholds at the leg. Clinical examination revealed pinprick and thermal hypoesthesia in about 50% patients, and signs of peripheral vascular autonomic dysfunction in about 70% of patients. Spontaneous pain dominated the clinical picture in most SFN patients. Neuropathic pain intensity was more severe in patients with SFN than in patients with large or mixed fibre neuropathy, but there was no significant correlation with IENF density. The aetiology of SFN was initially unknown in 41.8% of patients and at 2-year follow-up a potential cause could be determined in 25% of them. Over the same period, 13% of SFN patients showed the involvement of large nerve fibres, whereas in 45.6% of them the clinical picture did not change. Spontaneous remission of neuropathic pain occurred in 10.9% of SFN patients, while it worsened in 30.4% of them.

Keywords: neuropathy, pain, skin biopsy, quantitative sensory testing, neurophysiology

Introduction

In the last decade, after the availability of new tools for investigating unmyelinated C and thinly myelinated Aδ fibres, small fibre neuropathy (SFN) has been recognized as a distinct nosologic entity. Although small fibres encompass thermal and nociceptive sensation as well as autonomic functions, SFN commonly refers to somatic neuropathy alone and the overlap with the term ‘painful neuropathy’ is accepted. When autonomic dysfunctions prevail, the definition of ‘autonomic neuropathy’ is used. Small fibres are invisible to routine nerve conduction studies and their damage most frequently causes a neuropathic pain syndrome, making the diagnosis of SFN often particularly difficult. In fact, spontaneous and stimulus-evoked positive sensory symptoms frequently dominate the clinical picture and can hide the signs of small fibre loss, namely thermal and pinprick hypoesthesia. Moreover, conditions other than nerve fibre damage may mimic SFN, including venous insufficiency, spinal stenosis, myelopathy and psychosomatic disturbances.

In the literature, the definition of SFN reflected the methods used by the different authors to assess nerve fibre dysfunction, including clinical and neurophysiological findings, changes in thermal and pain thresholds using psychophysical tests and neuropathological examination using nerve biopsy or skin biopsy with intraepidermal nerve fibre (IENF) quantification. Non-conventional neurophysiological techniques, such as cutaneous silent period examination (Osio et al., 2004), and new devices such as laser evoked potentials (LEPs) (Truini et al., 2004) and contact heat evoked potentials (Atherton et al., 2007) have been also used to assess small fibre dysfunction in patients with peripheral neuropathy, with the aim to demonstrate specific findings for diagnosing SFN. Overall, these studies have contributed to increase the awareness on SFN among neurologists and others specialists, such as diabetologists, but did not lead to a definition of the syndrome. Thus, the absence of a diagnostic ‘gold standard’ for SFN remains a limitation in clinical practise and research.

Skin biopsy has been included in the diagnostic work-up of patients with suspected SFN after the availability of antibodies against the protein-gene-product 9.5, a predominantly neuronal form of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase transported with the slow component of the axonal transport (Wilkinson et al., 1989), which allowed demonstrating the extensive innervation of the epidermis. IENF are somatic unmyelinated C-fibres and express the capsaicin receptor, indicating that they are nociceptors (Lauria et al., 2006). Skin biopsy can reliably demonstrate the loss of IENF in SFN, thus confirming the diagnosis when clinical and neurophysiologic examinations are not informative (Lauria et al., 2005; Gibbons et al., 2006). Moreover, this technique has been used to show that small fibres degenerate early in the course of neuropathies associated with diabetes and HIV infection, and that their morphological changes may predict the progression to a more diffuse neuropathy (Lauria et al., 2003; Gibbons et al., 2006; Herrmann et al., 2006). Although the availability of skin biopsy has been a major advance for diagnosing SFN, the correlation between IENF density and neuropathic pain remains unclear. In fact, a complete denervation of the epidermis can be seen in patients both with persisting neuropathic pain and genetic insensitivity to pain (Nolano et al., 2000; Lauria et al., 2006), thus raising the question whether the loss of IENF itself is causally related to pain or it is only an indicator of neuropathy. Data from the literature suggest that a more severe loss of IENF increases the risk to develop neuropathic pain, whereas IENF regeneration can be associated with a decrease in pain intensity (Sommer and Lauria, 2007).

We conducted a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients with sensory neuropathy and identified homogeneous groups of patients according the type of nerve fibre involvement. The first aim of our study was to compare specificity and sensitivity of clinical examination, quantitative sensory testing (QST) and skin biopsy in order to propose a reliable definition of SFN using a multimodal diagnostic approach. The second aim was to analyse the correlation between the different features of neuropathic pain in patients with SFN and the density of IENF to understand whether skin biopsy may predict the clinical picture and the progression of the disease.

Patients and Methods

We screened the clinical files of 486 patients referred to our institutions for suspected sensory neuropathy from January 1, 2004 to May 31, 2007. Patients eligible for the present study did have to fulfil the following criteria: (i) symptoms suggesting sensory neuropathy; (ii) availability of clinical and neuroalgologic examinations, including intensity and characteristics of spontaneous and stimulus-evoked pain; (iii) availability of sensory and motor nerve conduction study (NCS) in at least two sensory and two motor nerves at both upper and lower limbs; (iv) availability of skin biopsy with quantification of IENF density at the proximal thigh and the distal leg; (v) availability of warm and cooling thresholds at the foot assessed by QST. A subgroup of patients underwent also LEPs and laser Doppler flowmetry.

Clinical and neuroalgologic examinations

We aimed at identifying the clinical signs of neuropathy and the quality and intensity of pain. Presence and distribution (e.g. length or non-length dependent) of sensory loss and pain, gait impairment and dysautonomic symptoms (e.g. pupil abnormalities, impotence, impaired bladder function, constipation or diarrhoea, early satiety and gastric fullness, abnormal sweating, flushing, skin decolouration, xerostomia and xerophthalmia, orthostatic hypotension) were recorded. Patients were asked to report whether they experienced thermal allodynia (e.g. taking the shower) and/or pain in the feet while walking, wearing certain shoes or touching the sheets. In all patients, we assessed the diagnosis of restless leg syndrome using the questionnaire revised by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (Allen et al., 2003).

Superficial and proprioceptive sensations were examined in order to identify negative sensory signs (sensory loss) and positive sensory signs (evoked and spontaneous pain, paraesthesias, restless leg syndrome). The neurological examination was performed using cotton gauze (light touch and dynamic mechanic allodynia test), disposable safety needle (hypoalgesia, pinprick hyperalgesia, aftersensation test), glass vials filled with cold and hot water (thermal sensation, allodynia test, aftersensation test) and 128 Hz Rydel-Seiffer tuning fork (vibration at the first metatarsal joints, ankles, knees, first metacarpal joints, elbows). Sense of movement and position of toes and hand fingers were evaluated. Deep tendon reflexes were graded as normal, decreased (if present with reinforcement) or absent. Muscle strength was graded using the Medical Research Council (MRC) score. Positive Romberg's sign and gait abnormalities were recorded.

Patients were diagnosed with mononeuropathy, multiplex mononeuropathy, polyneuropathy and sensory neuronopathy. Polyneuropathy was distinguished in SFN, large fibre neuropathy (LFN) and mixed (large and small) fibre neuropathy (MFN). Intensity of spontaneous pain, allodynia [static mechanical (pressure), dynamic mechanical (brush), heat or cold (thermal)] and hyperalgesia were graded using the 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS). We used the following descriptors for pain: throbbing, lancinating, unpredictable, lightning-like, sharp, shooting, aching, burning, scalding, pruritic (Galer and Jensen, 1997).

In all patients, the aetiology of neuropathy was recorded and further exams were performed when appropriate. In particular, patients were screened for diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, thyroid diseases, hyperlipidemia, malignancies, hepatitis C, HIV infection and use of neurotoxic drugs. When appropriate, serum and urine protein immunofixation, autoantibodies, antibodies against gangliosides and sulphatide, onconeuronal antigens and neoplastic markers were analysed.

Neurophysiological tests

Patients underwent motor and sensory NCS using surface recording electrodes with standard placement. Normal lower values for ulnar and median sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) amplitude and conduction velocity (antidromic technique from fifth to second finger) were >20 μV and >50 m/s, whereas those for sural SNAP amplitude and conduction velocity were >6 μV and >42 m/s. Compound motor action potential (CMAP) amplitude and conduction velocity of peroneal, tibial, ulnar and median nerves were examined. A difference of at least 50% in SNAP and CMAP amplitude was required to define a significant asymmetry between sides. When appropriate, F-wave examination of the same nerves was carried out by delivering 20 random stimuli and minimal latency was corrected by height. Electromyography was performed with standard concentric needle in at least one proximal and one distal muscle of the extremities. A minimum of at least three areas with fibrillation potentials and/or positive sharp waves was required to identify a muscle as having spontaneous activity at rest. Motor unit potential changes and maximal recruitment pattern were evaluated with a semiquantitative recording.

In all patients who had already undergone NCS in other hospitals, we analysed the traces in order to verify the reliability of the examination and referred to the report signed by the neurophysiologist. When the traces were not available or the quality of the recording did not appear reliable or the test had been performed more than 3 months before, we repeated the examination.

Assessment of thermal thresholds

Warm, cold, heat pain and cold pain thresholds were assessed using the Medoc™ device (Medoc™ Thermal Sensory Analyser, TSA-2001, Israel). Thermal thresholds were quantified using a 30 × 30 mm probe at the dorsum of the foot and at the same sites where skin biopsies where taken (see subsequently). Warm and cooling detection thresholds (CDT, WDT) were evaluated with the method of limits, with ramp stimuli of 1°C/s from 32°C. Values were compared with the database of age- and sex-matched normative values. Results above the 95th percentile were considered abnormal. Abnormal sensation (errata sensation, paradoxical thermal sensation and thermal allodynia or hyperalgesia) and presence of aftersensation were recorded during the exams in an ad hoc table. Verbal pain rating [using the 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS)] was used to assess the intensity of cold and heat pain thresholds (CPT and HPT). We calculated warm and cold sensibility index to determine the pain sensitivity range in which thermal sensations were perceived (Jensen et al., 1991). Cold sensibility index was defined as: (cold pain detection threshold − cold threshold)/(cold pain detection threshold − reference temperature). Warm sensibility index was defined as: (warm pain detection threshold − warm threshold)/(warm pain detection threshold − reference temperature).

Skin biopsy

Our two skin biopsy laboratories have been following a yearly quality control programme for all the steps of the procedure that has guaranteed the inter-laboratory agreement on the quantification of IENF density, based on periodic exchange of slides for blind counting. In all patients and control healthy subjects included in the present study, skin biopsies were obtained from the proximal region of the thigh (20 cm below the anterior iliac spine) and the distal region of the leg (10 cm above the lateral malleolus, within the sural nerve territory). Biopsies were taken after local anaesthesia using a 3 mm disposable punch under sterile technique. Three sections randomly chosen from each biopsy were immunoassayed with polyclonal anti-protein-gene-product 9.5 antibodies (Biogenesis Ltd, Poole, UK; 1 : 1000) using the free-floating protocol for bright field immunohistochemistry previously described (Lauria et al., 2004). The linear density of IENF (IENF/mm) was calculated following the rules reported by the guidelines of the European Federation of the Neurological Societies (Lauria et al., 2005).

Laser Doppler flowmetry

Skin blood flow was measured using the laser Doppler flowmetry (PeriFlux™, Perimed PF4, Stockholm, Sweden), which measures skin blood flow in perfusion units (PU), representing the product of velocity and concentration of the moving blood cells within the volume measured. The 780 nm wave length light generated by the laser is directed to the skin using an optic-fibre probe and reflects from the moving blood cells undergoing a shift in frequency (Doppler effect). The thermostatic laser Doppler probes, which include recording and heating elements, heat the underlying skin area while blood perfusion is recorded. All the experiments were performed at room temperatures between 24°C and 27°C, with the subject lying awake in a clinostatic position. The probes were placed at the dorsum of the foot, at the same areas in which skin biopsies were performed (see above), and at the tip of the toe and of second finger of the hand. The probe temperature was 32°C during the baseline measurement. We measured the following parameters: skin temperature; basal cutaneous blood flow recorded continuously throughout the stimulation protocol; vasoconstriction reflexes induced by deep breathing and postural variation (veno-arteriolar reflex); vasodilatation induced by local heating (from 32°C to 44°C for 6 min). Vasoconstriction reflexes induced by deep breathing examine sympathetic adrenergic function, whereas veno-arteriolar reflex and vasodilatation induced by local heating investigate skin axonal reflexes carried by somatic C-fibres.

LEPs

We used a neodymium Laser (Nd: YAP) stimulator (79–119 mJ/mm2, 5 ms, 4 mm, Aδ input) able to elicit pinprick sensation activated by Aδ-fibres and warm sensation carried by C-fibres (38.2–63.7 mJ/mm2, 10 ms, 10 mm, C input). The stimulator with optic-fibre guidance was placed on a skin area of about 6 cm2 at the dorsal aspect of right hand, distal leg and dorsal foot. To determine the laser perceptive thresholds (PT), we delivered series of stimuli at different intensity and recorded the average pain rating for each site. We defined the PT as the lower intensity at which the subjects perceived at least 50% of the stimuli (Truini et al., 2005). Before starting LEPs recording, we delivered noxious laser pulses on the sites to be stimulated with the aim of familiarizing the patients and adjusting the energy of stimulation. This allowed obtaining a moderately painful pinprick sensation, with target pain rating 4 on the 11-point NRS (0 = no sensation, 3 = pain threshold, 10 = worst possible pain). Stimuli were delivered randomly, with intervals of 10–20 s between each consecutive pair of stimuli to avoid central habituation. The N2-P2 complex was recorded using surface disc electrodes from vertex (Cz) referenced to the earlobes (A1-A2). The early N1 component was recorded from T3 and T4 referenced to Fz. The electro-oculographic recording monitored eye movements and blinks. We averaged two series of 10–12 artefact-free trials for each site of stimulation and measured latency and amplitude of the main N2-P2 components and N1. Data were compared with the values obtained in 18 healthy subjects matched for age and sex. We analysed differences of laser PT using the Mann–Whitney test and differences in latency and amplitude of LEPS using the unpaired t-test.

Criteria to diagnose SFN

Patients were diagnosed with SFN when at least two of the following examinations were abnormal: (i) clinical signs of small fibre impairment (pinprick and thermal sensory loss and/or allodynia and/or hyperalgesia), which distribution was consistent with peripheral neuropathy (length or non-length dependent neuropathy); (ii) abnormal warm and/or cooling threshold at the foot assessed by QST; (iii) reduced IENF density at the distal leg.

SFN was ruled out in the presence of: (i) any sign of large fibre impairment (light touch and/or vibratory and/or proprioceptive sensory loss and/or absent deep tendon reflexes); (ii) any sign of motor fibre impairment (muscle waste and/or weakness); (iii) any abnormality on sensorimotor NCS.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann−Whitney test or unpaired t-test, when appropriate. Values <0.05 were considered significant. The diagnostic yield of skin biopsy and QST was estimated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The diagnostic yield of clinical examination, QST and skin biopsy for diagnosing SFN was calculated comparing each test versus the gold standard as defined following the criteria above mentioned (e.g. abnormal findings in at least two of three evaluations).

Results

Diagnosis and aetiology

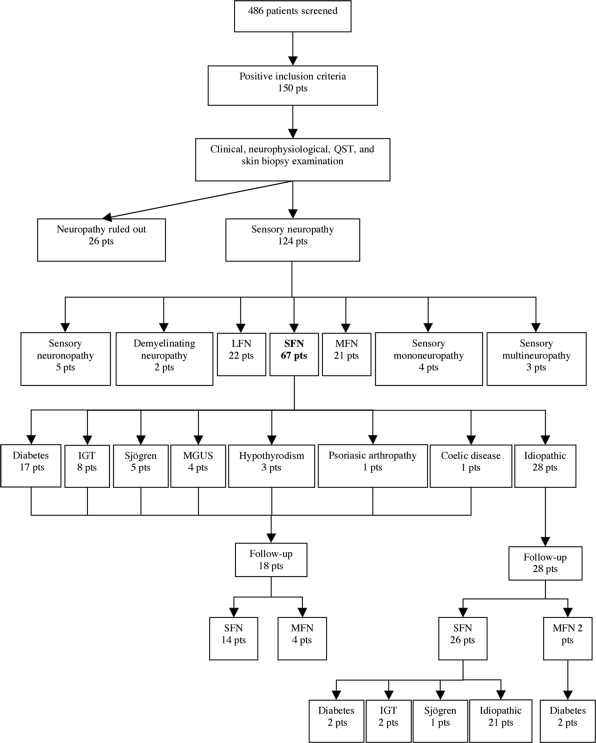

A total of 150 patients (77 women and 73 men) met the entry criteria for the study. Sensory neuropathy was diagnosed in 124 patients (61 women and 63 men) with age ranging from 22 to 84 years [mean 60 ± 14 SD]. Basing on clinical, neurophysiological, QST and skin biopsy findings, we classified the patients as affected by SFN (54%), LFN (17.7%), MFN (16.9%), sensory neuronopathy (4%), demyelinating sensory neuropathy (1.6%), sensory mononeuropathy (3.2%) and multiplex mononeuropathy (2.4%). We could define the aetiology of neuropathy in 66 patients (53.2%), whereas it remained unknown in 58 patients (47%). Neuropathy was associated with diabetes in 23 patients (18.5%), IGT in eight patients (6%), monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) in eight patients (6%), Sjögren's syndrome in five patients (4%), hepatitis C virus in four patients (3.2%), anti-myelin associated glycoprotein antibodies in two patients (1.6%), sensory Guillain-Barré syndrome in two patients (1.6%), other rheumatological diseases (undifferentiated connective tissue disorders, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasic arthropathy) in six patients (4.8%), anti-neoplastic drugs in two patients (1.6%), hypothyroidism in three patients (2.4%), nerve entrapment in two patient (1.6%), celiac disease in one patient (0.8%). Figure 1 details the diagnostic categories based on the type of nerve fibre involvement and the aetiology of SFN.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the various categories of sensory neuropathies diagnosed after clinical examination, nerve conduction studies, QST and skin biopsy. The aetiology of SFN at first observation and at 2-year follow-up is detailed.

In 26 patients with sensory disturbances in the feet, the diagnosis of neuropathy was ruled out after clinical and neurophysiological examination, QST and skin biopsy. In seven of them with progressive gait impairment and chronic back pain, electromyography showed neurogenic changes of motor unit potentials suggesting lumbosacral radiculopathy and spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed lumbar spine stenosis. In six patients complaining of spontaneous pain with atypical distribution (e.g. pain throughout the body, transient pain in different regions of the body), a defined psychiatric illness (e.g. psychotic depression) was diagnosed. Finally, three patients were diagnosed with venous insufficiency in the legs.

Clinical findings

Neuropathic pain dominated the clinical picture in 110 patients, whereas 14 patients complained of non-painful paraesthesias. Overall, 31 patients (28.2%) had spontaneous pain and nine patients (8.2%) had evoked pain alone, whereas the remaining 70 patients (63.6%) complained of both spontaneous and evoked pain. Evoked pain alone was characterized by static light touch allodynia in four patients and dynamic mechanic allodynia in five patients, associated with warm allodynia in one of them. Considering the quality of pain, patients were divided into the following three larger groups: burning pain (69.2%), sharp pain (30.7%) and ‘sunburn-like’ pain (24.4%). Paroxysmal pain dominated the clinical picture in 4.5% of patients and it was associated with ongoing burning pain in 10.9% of patients. Pain was described as pruritic in 4.4% of patients, deep aching in 2.2% of patients and cold in 1.1% of patients (Table 1). Five patients (4%) with MFN fulfilled the criteria for restless leg syndrome. In the SFN group, 40 patients (59.7%) had both spontaneous and evoked pain, 26 patients (38.8%) had only spontaneous pain and only one patient had evoked pain alone (dynamic mechanic and warm allodynia).

Table 1.

Features and intensity of spontaneous pain in different types of painful sensory neuropathy

| SFN | LFN | MFN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pts (%) | VAS | No. pts (%) | VAS | No. pts (%) | VAS | |

| Burning pain | 36 (53.7) | 6.5 | 3 (13) | 4.5 | 12 (60) | 6.5 |

| Sharp pain | 11 (16.4) | 7.2 | 9 (39) | 5.2 | 3 (15) | 4.5 |

| Sunburn pain | 8 (11.9) | 8.0 | 0 | – | 2 (10) | 5.5 |

| Paroxysmal paina | 3 (4.5) | 9 | 2 (8.7) | 7.5 | 1 (5) | 9.4 |

| Pruritic pain | 4 (5.9) | 6.8 | 0 | – | 0 | – |

| Deep aching pain | 3 (4.5) | 5.2 | 5 (21.7) | 4.8 | 1 (5) | 6.4 |

| Cold pain | 2 (3) | 6.5 | 1 (4.3) | 4.0 | 1 (5) | 5.3 |

aPain intensity measured with VAS during the attacks.

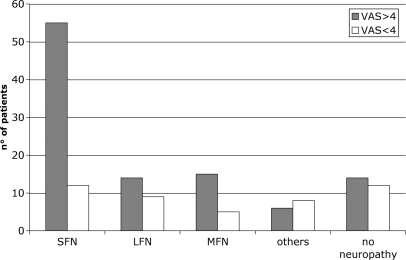

The intensity of neuropathic pain at VAS was >4 in 91 patients (82.7%) and <4 in 19 patients (17.3%). When comparing the different subtypes of neuropathy, we found that pain was much more frequent in patients with SFN than in the other groups and its intensity was >4 at VAS in most cases (Fig. 2). NCS results were normal in SFN patients, whereas revealed an axonal sensory neuropathy in patients with LFN and MFN (Table 2). In all patients with LFN and MFN, clinical examination showed signs of large fibre impairment, whereas evoked pain was present in 77.6% of patients. Clinical examination revealed pinprick and thermal hypoesthesia in 52.2% and evoked pain in 59.7% of patients with SFN (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between intensity of neuropathic pain and type of neuropathy in 124 patients. ‘Others’ include mononeuropathies and sensory neuronopathies. ‘No neuropathy’ include patients in whom the diagnosis of neuropathy was ruled out.

Table 2.

Sensory and motor NCS results in different types of painful sensory neuropathy

| SFN (n = 67) | LFN (n = 23) | MFN (n = 20) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median nerve | |||

| SNAP (µV) | 22.9 ± 2 | 6.5 ± 5 | 5.5 ± 4 |

| SCV (m/s) | 55.1 ± 3 | 52 ± 2 | 50 ± 1.5 |

| CMAP (mV) | 12.2 ± 3.4 | 10 ± 2.3 | 9 ± 1.8 |

| MCV (m/s) | 52.8 ± 2 | 52.2 ± 2.3 | 50.2 ± 2 |

| DL (ms) | 3.5 ± 1 | 3.6 ± 1 | 3.9 ± 1.4 |

| F-wave (ms) | 26.5 ± 3 | 26.5 ± 2 | 26 ± 3 |

| Ulnar nerve | |||

| SNAP (µV) | 35.0 ± 7 | 12.0 ± 4 | 14.0 ± 3 |

| SCV (m/s) | 54.2 ± 4 | 50.1 ± 3 | 49.1 ± 2 |

| CMAP (mV) | 6.8 ± 2 | 5.4 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 |

| MCV (m/s) | 54.2 ± 5.3 | 52.2 ± 4 | 49.2 ± 3 |

| F-wave l (ms) | 27.5 ± 3.2 | 27.2 ± 2 | 26.2 ± 2 |

| Sural nerve | |||

| SNAP (µV) | 18.2 ± 3.5 | 2.3 ± 3.7 | 5.0 ± 8.2 |

| SCV (m/s) | 42.5 ± 2.4 | 41.6 ± 1.2 | 42 ± 1.8 |

| Peroneal nerve | |||

| CMAP (mV) | 5.0 ± 2 | 4.5 ± 1.8 | 4.2 ± 0.9 |

| MCV(m/s) | 49.2 ± 2 | 48.2 ± 3 | 46.2 ± 2 |

| DL (ms) | 3.9 ± 1 | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 3.8 ± 1.2 |

| F-wave l (ms) | 48.3 ± 3 | 49 ± 2 | 48 ± 3 |

| Tibial nerve | |||

| CMAP(mV) | 5.8 ± 1 | 4.6 ± 3 | 5.9 ± 1 |

| MCV(m/s) | 54.2 ± 4 | 48.4 ± 2 | 49.2 ± 2 |

| DL (ms) | 4.8 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 4.8 ± 1 |

| F-wave l (ms) | 50.2 ± 5.3 | 50 ± 4.6 | 50 ± 3.7 |

Value are expressed as mean ± SD. MCV = motor conduction velocity; DL = distal latency; SCV = sensory conduction velocity.

Table 3.

Clinical findings and features of evoked pain in 67 patients with SFN

| No. of patients (%) | NRS | |

|---|---|---|

| Pinprick hypoesthesia | 25 (37.7) | – |

| Warm hypoesthesia | 12 (17.9) | – |

| Cold hypoesthesia | 5 (7.4) | – |

| Static light touch allodynia | 4 (5.9) | 7 |

| Dynamic mechanic allodynia | 1 (1.5) | 5 |

| Warm allodynia | 14 (20.9) | 8 |

| Cold allodynia | 18 (26.8) | 7 |

| Hyperalgesia | 13 (19.4) | 5 |

| Aftersensation | 8 (11.9) | 4 |

The intensity of evoked pain was measured by the 11-point NRS. Percentage refers to the dominating clinical finding, since all patients showed more than one single type of sensory defect and pain.

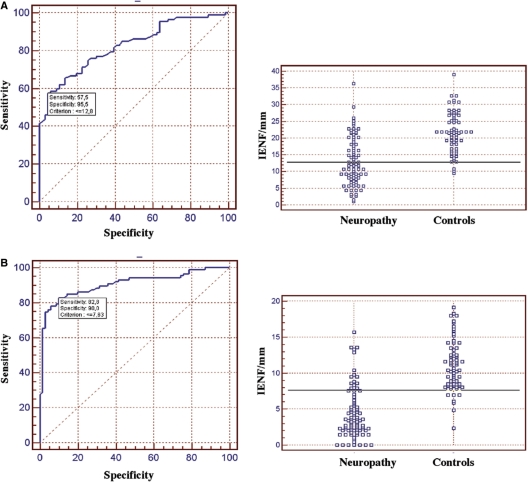

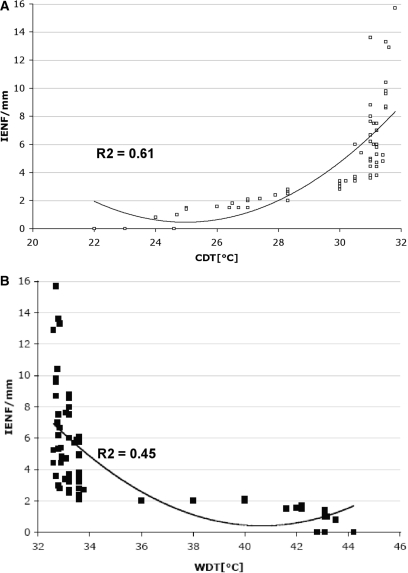

Skin biopsy findings

The cut-off values of IENF density were calculated using the ROC curve analysis comparing patients with 47 healthy subjects. Values of 12.8 IENF/mm at proximal thigh and 7.63 IENF/mm at distal leg were associated with specificity of 57.5 and 90% and sensibility of 95.5 and 82.8%, respectively (Fig. 3). Spearman's correlation between laboratories for IENF density quantification was 0.87. IENF density at the distal leg was abnormal in 59 patients (88%) with SFN and in 17 patients (81%) with MFN, whereas it was normal in all patients with LFN (Table 4). IENF density at the distal leg was normal in six patients with psychiatric illness (9.92 ± 2.5), in seven patients with lumbar stenosis (9.3 ± 2.3) and in three patients with venous insufficiency (12.5 ± 0.14).

Fig. 3.

ROC analysis of IENF density at the proximal thigh (A) and the distal leg (B) in 110 patients with painful sensory neuropathy and 47 healthy controls. At the proximal thigh, the cut-off value was 12.8 IENF/mm (SE = 0.035, area under the curve = 0.825 and 95% CI = 0.756–0.882). At the distal leg, the cut-off value was 7.63 IENF/mm (SE = 0.026, area under the curve = 0.906 and 95% CI = 0.849–0.947).

Table 4.

Mean density (±SD) of IENF at proximal thigh (Pth) and distal leg (Dl) in healthy controls and patients with SFN, MFN and LFN

| No. | Pth | Dl | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | 47 | 21.7 ± 4.9 | 9.8 ± 3.6 |

| SFN | 67 | 12.9 ± 6.9 | 4.4 ± 3.6 |

| MFN | 21 | 12.8 ± 7.9 | 4.3 ± 3.1 |

| LFN | 22 | 21.5 ± 6.3 | 11.0 ± 2.6 |

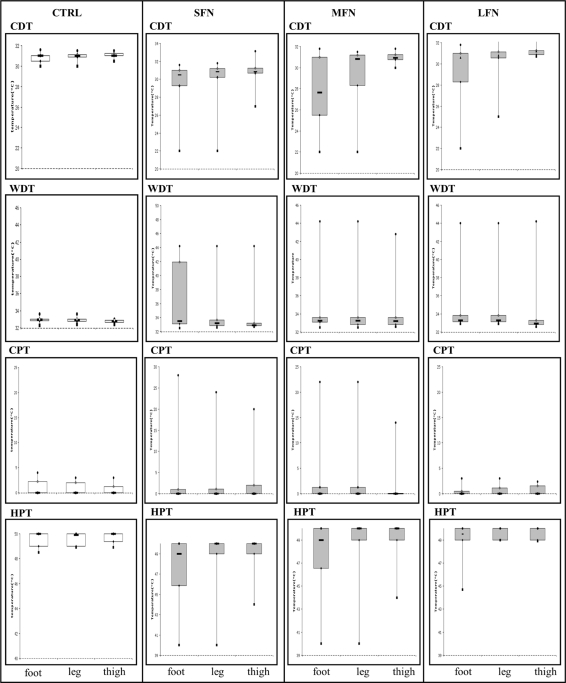

QST findings

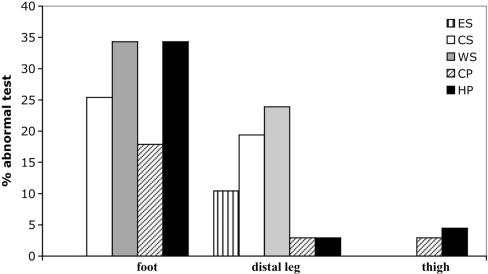

CDT, WDT, CPT and HPT were measured in all patients with neuropathy and in 24 healthy controls (Fig. 4). Sensory threshold for at least one thermal modality was abnormal in 38 patients (57.5%) with SFN, in 10 patients (47.6%) with MFN and in 12 patients (54.4%) with LFN, comparing with healthy subjects. In all patients, both WDT and CDT were altered at foot and distal leg, whereas WDT was abnormal also at the proximal thigh in 5.5% of SFN and MFN patients and CPT in 1.4% of patients.

Fig. 4.

QST at dorsal foot, distal leg and proximal thigh in healthy controls (CTRL) and patients with SFN, MFN and LFN. Box plots represent the median value with 25th and 75th percentiles.

In the group of SFN, 31 patients (46.2%) had abnormal CDT (17 at foot, 13 at distal leg, none at proximal thigh), and seven patients (10.4%) had errata perception paraesthesias or warm sensation (all at distal leg). Twelve patients (14.9%) had cold allodynia (12 at foot, two at distal leg and two at proximal thigh) with lower cold sensibility index (0.169) than patients without cold allodynia (20.21) and healthy subjects (30.8). Twenty-three patients (34%) had abnormal WDT (23 at foot, 16 at distal leg and five at proximal thigh). Twenty-two patients (32.8%) had heat hyperalgesia with mean intensity of 7.3 ± 1.5 at the 11-point NRS (22 at foot, two at distal leg, three at proximal thigh), and only one had heat allodynia (T<40°C) at foot, with lower warm sensibility index (−0.95) than SFN patients without warm allodynia (−6.26) and healthy subjects (15.8) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Distribution of abnormal QST findings in 67 patients with SFN. ES = errata sensation; CS = cold sensation; WS = warm sensation; CP = cold pain; HP = heat pain.

Six patients (30%) with MFN had abnormal CDT (six at foot, four at distal leg, none at proximal thigh) and three patients (15%) had errata perception paraesthesias or warm sensation (all at distal leg). Four patients (5.9%) had cold allodynia (three at foot, one at distal leg, one at proximal thigh). Eight patients (40%) had abnormal WDT (eight at foot, three at distal leg, one at proximal thigh). One patient (5%) had heat allodynia (at foot), while seven (35%) had heat hyperalgesia with NRS mean 7.4 ± 1.5 (seven at foot, three at distal leg, one at proximal thigh).

Five patients (21.7%) with LFN had abnormal CDT (three at foot, three at distal leg, none at proximal thigh), and one patient had errata perception paraesthesias or warm sensation (at distal leg). No patient had cold allodynia. Eight patients (34.8%) had abnormal WDT (six at foot, two at distal leg, none at proximal thigh). Three patients (13%) had heat hyperalgesia with NRS mean 6.66 ± 1.5 (at foot and distal leg).

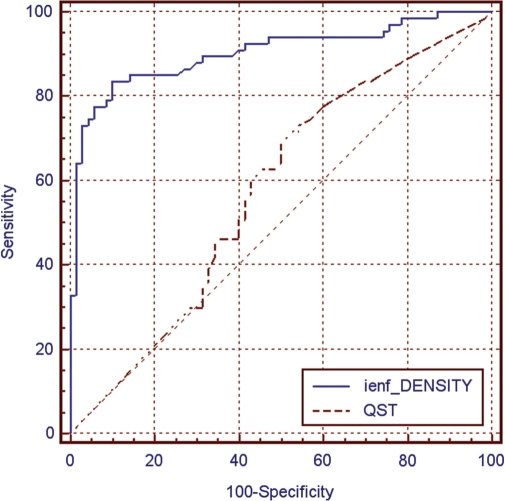

Diagnostic yield of skin biopsy, QST and clinical findings in SFN

The diagnosis of SFN was based on abnormal clinical and skin biopsy findings in 43.3% of patients, on abnormal clinical and QST findings in 11.9% of patients and on abnormal skin biopsy and QST findings in 37.3% of patients. Only 7.5% of patients showed abnormal results at all the three examinations. We calculated the diagnostic efficiency (weighed summation of specificity and sensibility) of clinical examination, QST and skin biopsy against the proposed gold standard for the diagnosis of SFN. Skin biopsy showed a diagnostic efficiency of 88.4%, clinical examination of 54.6% and QST of 46.9% (Table 5). ROC analysis confirmed the significantly higher performance of skin biopsy comparing with QST (Fig. 6).

Table 5.

Diagnostic efficiency of clinical examination, QST and skin biopsy at the distal leg against the diagnostic ‘gold standard’ for small fibre neuropathy

| Clinical examination (%) | QST (%) | Skin biopsy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensibility | 62.6 | 56.7 | 88 |

| Specificity | 46 | 36.5 | 88.8 |

| Positive predictive value | 55.3 | 48.7 | 89.4 |

| Negative predictive value | 53.7 | 44.2 | 87.5 |

Fig. 6.

ROC analysis in 67 patients with SFN comparing the diagnostic yield of skin biopsy with quantification of IENF and QST at the distal leg. Area under the ROC was 0.904 for IENF density (SE = 0.027; 95% CI = 0.841–0.947) and was 0.576 for QST (SE = 0.049; 95% CI = 0.488–0.660). Difference between areas was 0.328 (SE = 0.053; 95% CI = 0.225–0.431; P < 0.001).

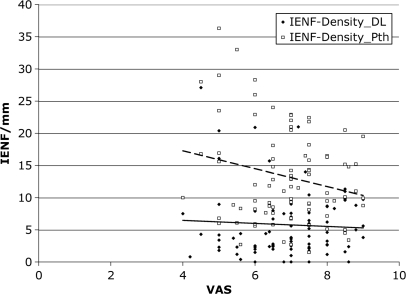

Correlation between skin biopsy, intensity of pain and QST in patients with SFN

We found a trend toward an inverse correlation between intensity of pain and IENF density at the proximal thigh, but not at the distal leg (Fig. 7). IENF density at distal leg was significantly lower (P = 0.003) in patients with pure spontaneous pain (n = 31) than in patients with pure evoked pain (n = 9). We found a significant (P < 0.0001) inverse correlation between IENF density and all the thermal thresholds at the dorsum of the foot and at the distal leg (Fig. 8), whereas at the proximal thigh there was a significant correlation only with warm and HPT (P < 0.005), but not with cold threshold.

Fig. 7.

Correlation between intensity of pain measured by the VAS and the linear innervation density of the epidermis (IENF/mm) at proximal thigh (Pth) and distal leg (Dl) in 67 patients with SFN. No significant correlation was found.

Fig. 8.

Correlation analysis of IENF density (IENF/mm), (CDT; A) and (WDT; B) at the distal leg in patients with SFN. Data did not show a normal distribution. Non-parametric Mann−Whitney U-test demonstrated the significant correlation between IENF/mm and both CDT (P < 0.0001) and WDT (P < 0.0001) at the distal leg.

Autonomic signs and functional tests in SFN

Clinical signs of autonomic dysfunction were present in 32 patients (47.8%) with SFN: 18 patients had hypo-anidrosis, 12 patients had flushing or other vasomotor dysfunctions and two patients had Adie's pupils with post-ganglionic hypersensibility to 0.1% pilocarpine test. Laser Doppler flowmetry was abnormal in 51 patients (76.1%), whereas 16 patients (32.9%) showed abnormal temperature and basal cutaneous blood flow with inverted hand-foot gradient. Vasoconstriction reflexes to deep breathing at the foot were abnormal in 11 patients (16.4%) and veno-arteriolar reflex was abnormal in 18 patients (26.8%). Vasodilatation response to local heating was reduced in 42 patients (38.8%): in 26 patients at the foot, in 20 patients at the distal leg and one patient at the proximal thigh.

LEPs in SFN

We analysed 10 patients with SFN and 18 healthy subjects. PT was determined for Aδ and C-nociceptors at the dorsal aspect of right hand, distal leg and dorsal foot. Late-Aδ LEPs induced a pinprick sensation at the irradiated sites both in healthy subjects and SFN patients. The PT did not differ between controls and patients at the dorsal aspect of the hand, whereas it was significantly higher in patients at the lower limb (P < 0.0007 at dorsal foot; P < 0.0009 at distal leg; Mann–Whitney test). Ultralate-C LEPs evoked a warm sensation at the irradiated sites in 16 healthy subjects and in six patients with SFN. Two healthy subjects and four SFN patients perceived burning pinprick and were excluded from the analysis.

Reproducible late-Aδ LEPs were recorded in all healthy subjects and in most SFN patients after stimulation of hand, foot and distal leg. Conversely, reproducible ultralate-C LEPs could be recorded in most healthy subjects and SFN patients at the distal leg, but only in few controls and patients at the foot. The N2-P2 complex could not be recorded after Aδ-fibre stimulation at the dorsal foot in two patients and the distal leg in one patient. The N2-P2 complex was delayed in latency in one patient after stimulation at both foot and distal leg. In the other patients, latency and peak-to-peak amplitude of N2-P2 complex did not differ from healthy subjects (Table 6).

Table 6.

LEP analysis in patients with SFN and in healthy controls

| Nd SFN: YAP stimulator input | Hand (dorsum) | Foot (dorsum) | Distal leg | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT (mJ/mm2) | N2 wave latency (ms) | P2 wave latency (ms) | Amplitude (μV) | PT (mJ/mm2) | N2 wave latency (ms) | P2 wave latency (ms) | Amplitude (μV) | PT (mJ/mm2) | N2 wave latency (ms) | P2 wave latency (ms) | Amplitude (μV) | |

| Aδ-fibres | ||||||||||||

| SFN No.10 | 106.9 ± 15.9 | 211.8 ± 8.5 | 300.1 ± 31.1 | 11.4 ± 5.4 | 152.6 ± 29.4 | 281.4 ± 27.3a | 362.1 ± 29.2a | 11.25 ± 5.8a | 147.4 ± 26.2 | 281.3 ± 25.9b | 346.4 ± 29.6b | 18.3 ± 3.2b |

| Controls No.18 | 99 ± 8.4 | 213.5 ± 9.3 | 299.2 ± 34.7 | 19.0 ± 8.0 | 101.8 ± 15 | 285.1 ± 16.9 | 371.8 ± 23.6 | 15.7 ± 7.2 | 103.3 ± 13.6 | 274.6 ± 17.3 | 331 ± 23.9 | 18.4 ± 6.6 |

| P | ns | ns | ns | ns | <0.0007 | ns | ns | ns | <0.0009 | ns | ns | ns |

| C-fibres | ||||||||||||

| SFN No.6 | 40.3 ± 3.3 | 906.5 ± 62.4 | 1015 ± 39.4 | 11.8 ± 6.4 | 60.5 ± 4.5 | 1602 ± 121.6c | 1692 ± 74c | 5.6 ± 1.1c | 58.6 ± 5.36 | 1417.6 ± 106e | 1488 ± 125e | 6.3 ± 1e |

| Controls No.16 | 38.6 ± 1.6 | 902.8 ± 46.3 | 979.4 ± 45 | 10.6 ± 4 | 44.58 ± 4.5 | 1557 ± 142.8d | 1638.8 ± 151.5d | 7.2 ± 2.2d | 43 ± 4.7 | 1445 ± 129.8f | 1536 ± 127f | 7 ± 2f |

| P | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | <0.0013 | ns | ns | ns |

All results are given as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis for PT was performed with Mann–Whitney test, whereas analysis of latency and amplitude was performed with paired t-test.

Significant statistical difference was set at P < 0.05. Aδ-LEPs were detected in aeight patients (foot) and bnine patients (distal leg); C-LEPs were detected in ctwo patients and dsix subjects (foot), and in efive patients and f12 subjects (distal leg). N2-P2 waves were absent or delayed in four patients (see text).

Natural course of SFN

We could follow-up 46 of 67 patients (68.5%) with SFN over a mean period of 22.3 ± 7.4 (SD) months (range 6–32), including the 28 patients formerly diagnosed with idiopathic SFN. Patients with idiopathic SFN underwent follow-up screening to assess a potential aetiology, which was found in seven of them (25%): four patients developed diabetes, two patients had IGT and one patients was diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome.

In six patients (13%), clinical and NCS follow-up demonstrated the involvement of large nerve fibres thus changing the diagnosis in MFN. Four of them had a known aetiology (diabetes in two patients and MGUS in two patients), whereas two patients with initially idiopathic SFN developed diabetes (Fig. 1). Spontaneous remission of neuropathic pain occurred in five patients (10.9%). Conversely, 14 patients (30.4%) experienced a worsening of pain intensity. In 21 patients (45.6%), clinical and neurophysiological evaluations did not differ from the first observation.

Discussion

The need of reliable criteria for the diagnosis of SFN comes both from clinical practise and research. Small fibres, which can be early affected in systemic diseases like diabetes, are invisible to neurophysiological investigations and their impairment can cause a chronic neuropathic pain syndrome predominantly involving the feet. Degeneration of small nerve fibres can predict the progression to a more diffuse neuropathy (Lauria et al., 2003; Gibbons et al., 2006; Herrmann et al., 2006), making the early diagnosis of SFN important for the correct treatment of patients. Recent studies have also suggested that subclinical involvement of most distal large sensory fibres can occur in SFN (Herrmann et al., 2004; Sharma et al., 2007).

SFN encompasses several aetiologies, including diabetes and pre-diabetes conditions, hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia, statin and anti-retroviral therapy (McManis et al., 1994; Moore et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2001; Lo et al., 2003; Sumner et al., 2003; Orstavik et al., 2006), immune-mediated and connective tissue disorders (Hoitsma et al., 2002; Brannagan et al., 2005; Gondim et al., 2005; Mori et al., 2005; Goransson et al., 2006; Gorson et al., 2008), infective diseases (Kaida et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2007), paraneoplastic syndromes (Oki et al., 2007) and genetic diseases (Stögbauer et al., 1999; Dutsch et al., 2002; Nolano et al., 2006). In several patients, the aetiology may remain unknown (Hoitsma et al., 2004; De Sousa et al., 2006). Therefore, patients complaining of symptoms suggesting SFN must be diagnosed for at least three main reasons. First, the definition of the diagnosis can lead to a focused screening on its aetiology. Second, early disease modifying or symptomatic treatments can be started. Third, the awareness of the disease can increase patients’ compliance, which is particularly important in the treatment of neuropathic pain.

In the last decade, the interest in the field of SFN has increased much, new diagnostic tools have been developed and several reviews have been published (Santiago et al., 1999; Al-Shekhlee et al., 2002; Lacomis, 2002; Said, 2003; Hoitsma et al., 2004; Lauria, 2005; Fink and Oaklander, 2006; Goodman, 2007; Horowitz, 2007). Nevertheless, relatively few studies have investigated into details homogeneous groups of patients with SFN and compared the yield of the different diagnostic tools available (Holland et al., 1998; Schuller et al., 2000; Dutsch et al., 2002; Brannagan et al., 2005; Zambelis et al., 2005; Goransson et al., 2006; Orstavik et al., 2006; Sorensen et al., 2006a, b; Gorson et al., 2008; Walk et al., 2007). In particular, there has been little emphasis on the value of clinical examination. The general view of SFN is that of a quite stereotypical neuropathic syndrome, though little is known about the different features of pain, the prevalence of somatic and autonomic abnormalities, and its natural course (Hoitsma et al., 2004).

Our study provided a comprehensive analysis of a large group of patients with painful neuropathy, among whom 67 patients with pure SFN were identified. SFN was defined using narrow criteria, based on clinical examination, QST and skin biopsy rather than on the description of symptoms and signs alone. Skin biopsy showed the highest sensibility, specificity and positive and negative predictive values, confirming the result of several previous studies (Lauria et al., 2005; Gibbons et al., 2006; Loseth et al., 2006; Walk et al., 2007). Our findings confirmed the concordance between skin biopsy and sensory examination previously observed in patients with SFN (Herrmann et al., 2004; Walk et al., 2007). Therefore, this technique, introduced in clinical practise only about one decade ago, demonstrated to provide reliable diagnostic information when there is little or no clinical evidence of neuropathy, such as it may happen in patients complaining of burning feet, and to distinguish conditions mimicking a neuropathy. Reduced epidermal innervation density has been used as mandatory criteria for diagnosing SFN (Holland et al., 1998).

Nevertheless, our study showed that skin biopsy results can be normal in about 10% of patients in whom SFN is diagnosed by clinical and QST examination. This finding emphasizes that a multimodal approach to SFN using the gold standard, we have proposed can better describe the diagnostic spectrum possibly encountered in clinical practise.

Interestingly, clinical examination with evaluation of negative (hypoesthesia) and positive (evoked pain) signs correlated with the diagnosis of SFN in about half of patients, showing a higher diagnostic efficiency than QST. This finding strengthens the assumption that a thorough clinical evaluation should drive the diagnostic work-up in patients with peripheral neuropathy (England et al., 2005). SFN is commonly considered a condition in which most patients have a normal clinical examination. Conversely, we have demonstrated that it happens only in about one-third of patients that is the group in which the diagnosis was achieved by skin biopsy and QST alone. Distribution and course of sensory symptoms and clinical signs can help in differentiating length-dependent sensory axonopathies from non-length-dependent sensory neuronopathies (Sghirlanzoni et al., 2005). However, in patients with non-length-dependent pattern of sensory disturbances limited to small fibre impairment, the presence of abnormal findings at clinical and QST examination alone may not rule out a myelopathy, which should be taken into account in the differential diagnosis of SFN.

Assessment of thermal thresholds using psychophysical techniques has been widely used to investigate the function of small nerve fibres. However, this approach proved to be more useful in population studies than in single patients (Shy et al., 2003; Hansson et al., 2007). The expected correlation between cold and/or warm threshold, conveyed by Aδ and C-fibres, respectively, and IENF density was found in some (Pan et al., 2003; Pittenger et al., 2004; Shun et al., 2004; Sorensen et al., 2006a; Quattrini et al., 2007), but not all (Holland et al., 1997; Facer et al., 1998; Periquet et al., 1999) the previous studies. However, no study has previously analysed skin biopsy and QST within the same area. We observed a significant inverse correlation between IENF density and thermal thresholds at the distal leg, namely at the site commonly used to diagnose SFN with skin biopsy. Thus, the lack of concordance reported in some studies might be ascribed also to the different site where QST was performed, besides the relatively less homogeneity of the study population comparing with our study. Nevertheless, assessment of small fibre damage using QST showed a lower diagnostic efficiency than both clinical examination and skin biopsy. In particular, the low value of specificity, which is an important parameter when diagnosis or treatment may be harmful to patients, reflects the known difficult of psychophysical tests to correctly identify whether in individual subjects results are normal or abnormal (Hansson et al., 2007).

One further question still unaddressed is whether the innervation density of the epidermis influences features and intensity of neuropathic pain. Indeed, two opposite conditions—acquired painful neuropathy and congenital insensitivity to pain—are characterized by loss of IENF (Nolano et al., 2000; Lauria et al., 2006). Data from the literature appears somewhat discordant. Skin denervation causes pinprick and pain sensory loss that recover after nerve regeneration (Lauria et al., 1998; Simone et al., 1998; Nodera et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2006). Reduced density of IENF at the distal leg, which is typically found in patients with painful neuropathy, correlated with pain intensity in some (Polydefkis et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2007) but not all (Herrmann et al., 2006; Sorensen et al., 2006b) the studies. We found that patients with SFN complained of more severe pain than those with involvement of large sensory fibres. The features of neuropathic pain reflected the predominant impairment of Aδ and C-fibre, since spontaneous pain, thermal allodynia and hyperalgesia were most frequently reported (Baron, 2006). Moreover, IENF density at the distal leg was significantly lower in patients with pure spontaneous pain than in patients with pure evoked pain. Nevertheless, we did not find any significant correlation between IENF density at the lower limb and intensity of pain. Therefore, our understanding remains that a more severe loss of IENF may increase the risk to develop neuropathic pain, whereas IENF regeneration may be associated with a decrease in pain intensity (Sommer and Lauria, 2007).

Autonomic dysfunction is a common finding in patients with SFN, but it is likely underestimated in clinical practise. A previous study (Novak et al., 2001) reported a higher frequency of vascular deregulation in the lower limbs than cardiovascular autonomic impairment. Similarly, we found that SFN is associated with clinical signs of dysautonomia, which were most commonly limited to sweating and peripheral vascular impairment. Functional examination of small fibres by laser Doppler flowmetry confirmed the impairment of reflex mechanisms ensuring vasoconstriction and vasodilatation of peripheral blood vessels in most patients with SFN.

Among non-conventional neurophysiological tests, LEPs have been proposed to investigate SFN (Truini et al., 2004). We did not find significant differences in latency and amplitude of late and ultralate LEPs, reflecting Aδ and C fibre activation, respectively. Therefore, we could not explore any possible correlations with IENF density, clinical findings or QST results, which have been previously investigated only in single case reports (Perretti et al., 2003; Chiang et al., 2005). However, ultralate LEPs, which reflect the activation of the same class of fibres innervating the epidermis, cannot be recorded in all healthy subjects. Since damage to C-fibres implies the disappearance or the decrease in amplitude of the evoked potentials, there is need of comparative studies involving larger population of controls and patients.

Finally, we could examine the clinical course of SFN in a large cohort of patients over a follow-up period of 2 years. A potential aetiology could be determined in 25% of patients with a former diagnosis of idiopathic SFN. In most of them, diabetes or IGT was discovered. This finding emphasizes the importance of glucose tolerance test in the diagnostic work-up of patients with painful neuropathy (Sumner et al., 2003). Follow-up investigations revealed the progression to MFN only in a small number of patients. In most patients with SFN, the clinical picture did not change, but one-third of them experienced a worsening of neuropathic pain intensity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Enrica Diozzi for the technical support on laser evoked potential and nerve conduction studies. This work has been supported in part by unrestricted grants from BERCO S.p.A., Copparo and Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CMAP

compound motor action potential

- CDT

cold detection threshold

- CPT

cold pain thresholds

- HPT

heat pain thresholds

- IENF

intraepidermal nerve fibres

- IGT

impaired glucose tolerance

- LEPs

laser evoked potentials

- LFN

large fibre neuropathy

- MFN

mixed (large and small) fibre neuropathy

- MGUS

monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- NCS

nerve conduction study

- NRS

numerical rating scale

- PT

perceptive thresholds

- QST

quantitative sensory testing

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SFN

small fibre neuropathy

- SNAP

sensory nerve action potential

- VAS

visual analogue scale

- WDT

warm detection threshold

References

- Al-Shekhlee A, Chelimsky TC, Preston DC. Review: small-fiber neuropathy. Neurologist. 2002;8:237–53. doi: 10.1097/00127893-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Montplaisi J. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–19. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton D, Facer P, Roberts K, Misra V, Chizh B, Bountra C, et al. Use of the novel contact heat evoked potential stimulator (CHEPS) for the assessment of small fibre neuropathy: correlations with skin flare responses and intra-epidermal nerve fibre counts. BMC Neurol. 2007;3:21–30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R. Mechanisms of disease: neuropathic pain- -a clinical perspective. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2006;2:95–106. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannagan TH, 3rd, Hays AP, Chin SS, Sander HW, Chin RL, Magda P, et al. Small-fiber neuropathy/neuronopathy associated with celiac disease: skin biopsy findings. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1574–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.10.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HY, Chen CT, Chien HF, Hsieh ST. Skin denervation, neuropathology, and neuropathic pain in a laser-induced focal neuropathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa EA, Hays AP, Chin RL, Sander HW, Brannagan TH 3rd. Characteristics of patients with sensory neuropathy diagnosed with abnormal small nerve fibres on skin biopsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:983–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.091074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutsch M, Marthol H, Stemper B, Brys M, Haendl T, Hilz MJ. Small fiber dysfunction predominates in Fabry neuropathy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19:575–86. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, Miller RG, Asbury AK, Carter GT, et al. Distal symmetric polyneuropathy: a definition for clinical research: report of the American academy of neurology, the American association of electrodiagnostic medicine, and the American academy of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Neurology. 2005;64:199–207. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149522.32823.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facer P, Mathur R, Pandya S, Ladiwala U, Singhal B, Anand P. Correlation of quantitative tests of nerve and target organ dysfunction with skin immunohistology in leprosy. Brain. 1998;121:2239–47. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.12.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink E, Oaklander AL. Small-fiber neuropathy: answering the burning questions. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2006;2006:pe7. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2006.6.pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Neurology. 1997;48:332–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons CH, Griffin JW, Polydefkis M, Bonyhay I, Brown A, Hauer PE, et al. The utility of skin biopsy for prediction of progression in suspected small fiber neuropathy. Neurology. 2006;66:256–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194314.86486.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondim F, Brannagan T, Sander H, Chin R, Latov N. Peripheral neuropathy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Brain. 2005;128:867–79. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman B. Approach to the evaluation of small fiber peripheral neuropathy and disorders of orthostatic intolerance. Semin Neurol. 2007;27:347–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goransson LG, Tjensvoll AB, Herigstad A, Mellgren SI, Omdal R. Small-diameter nerve fiber neuropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:401–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorson KC, Herrmann DN, Thiagarajan R, Brannagan T, Chin RL, Kinsella LJ, et al. Non-length dependent small fiber neuropathy/ganglionopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:163–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.128801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson P, Backonja M, Bouhassira D. Usefulness and limitations of quantitative sensory testing: clinical and research application in neuropathic pain states. Pain. 2007;129:256–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann DN, Ferguson ML, Pannoni V, Barbano RL, Stanton M, Logigian EL. Plantar nerve AP and skin biopsy in sensory neuropathies with normal routine conduction studies. Neurology. 2004;63:879–85. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000137036.26601.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann DN, McDermott MP, Sowden JE, Henderson D, Messing S, Cruttenden K, et al. Is skin biopsy a predictor of transition to symptomatic HIV neuropathy? A longitudinal study. Neurology. 2006;66:857–61. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000203126.01416.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoitsma E, Marziniak M, Faber CG, Reulen JP, Sommer C, De Baets M, et al. Small fibre neuropathy in sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2002;359:2085–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08912-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoitsma E, Reulen JP, de Baets M, Drent M, Spaans F, Faber CG. Small fiber neuropathy: a common and important clinical disorder. J Neurol Sci. 2004;227:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland NR, Crawford TO, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, Griffin JW, McArthur JC. Small-fiber sensory neuropathies: clinical course and neuropathology of idiopathic cases. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:47–59. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland N, Stocks A, Hauer P, Cornblath D, Griffin J, McArthur J. Intraepidermal nerve fibre density in patients with painful sensory neuropathy. Neurology. 1997;48:708–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz SH. The diagnostic workup of patients with neuropathic pain. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TS, Bach FW, Kastrup J, Dejgaard A, Brennum J. Vibratory and thermal thresholds in diabetics with and without clinical neuropathy. Acta Neurol Scand. 1991;84:326–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1991.tb04963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida K, Kamakura K, Masaki T, Okano M, Nagata N, Inoue K. Painful small-fibre multifocal mononeuropathy and local myositis following influenza B infection. J Neurol Sci. 1997;151:103–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomis D. Small-fiber neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:173–88. doi: 10.1002/mus.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G. Small fibre neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:591–7. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000177330.35147.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Borgna M, Morbin M, Lombardi R, Mazzoleni G, Sghirlanzoni A, et al. Tubule and neurofilament immunoreactivity in human hairy skin: markers for intraepidermal nerve fibers. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:310–6. doi: 10.1002/mus.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Cornblath DR, Johansson O, McArthur JC, Mellgren SI, Nolano M, et al. EFNS guidelines on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:747–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, McArthur JC, Hauer PE, Griffin JW, Cornblath DR. Neuropathological alterations in diabetic truncal neuropathy: evaluation by skin biopsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:762–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.5.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Morbin M, Lombardi R, Borgna M, Mazzoleni G, Sghirlanzoni A, et al. Axonal swellings predict the degeneration of epidermal nerve fibers in painful neuropathies. Neurology. 2003;61:631–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000070781.92512.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Morbin M, Lombardi R, Capobianco R, Camozzi F, Pareyson D, et al. Expression of capsaicin receptor immunoreactivity in human peripheral nervous system and in painful neuropathies. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11:262–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2006.0097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YL, Leoh TH, Loh LM, Tan CE. Statin therapy and small fibre neuropathy: a serial electrophysiological study. J Neurol Sci. 2003;208:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loseth S, Lindal S, Stalberg E, Mellgren SI. Intraepidermal nerve fibre density, quantitative sensory testing and nerve conduction studies in a patient material with symptoms and signs of sensory polyneuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:105–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManis P, Windebank A, Kiziltan M. Neuropathy associated with hyperlipidemia. Neurology. 1994;44:2185–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RD, Wong WM, Keruly JC, McArthur JC. Incidence of neuropathy in HIV-infected patients on monotherapy versus those on combination therapy with didanosine, stavudine and hydroxyurea. AIDS. 2000;14:273–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200002180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Iijima M, Koike H, Hattori N, Tanaka F, Watanabe H, et al. The wide spectrum of clinical manifestations in Sjogren's syndrome-associated neuropathy. Brain. 2005;128:2518–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodera H, Barbano RL, Henderson D, Herrmann DN. Epidermal reinnervation concomitant with symptomatic improvement in a sensory neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:507–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolano M, Crisci C, Santoro L, Barbieri F, Casale R, Kennedy WR, et al. Absent innervation of skin and sweat glands in congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:1596–601. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolano M, Provitera V, Perretti A, Stancanelli A, Saltalamacchia A, Donadio V, et al. Ross syndrome: a rare or a misknown disorder of thermoregulation? A skin innervation study on 12 subjects. Brain. 2006;129:2119–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak V, Freimer ML, Kissel JT, Sahenk Z, Periquet IM, Nash SM, et al. Autonomic impairment in painful neuropathy. Neurology. 2001;56:861–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oki Y, Koike H, Iijima M, Mori K, Hattori N, Katsuno M, et al. Ataxic vs painful form of paraneoplastic neuropathy. Neurology. 2007;69:564–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266668.03638.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orstavik K, Norheim I, Jorum E. Pain and small-fiber neuropathy in patients with hypothyroidism. Neurology. 2006;67:786–91. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234035.13779.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osio M, Zampini L, Muscia F, Valsecchi L, Comi C, Cargnel A, et al. Cutaneous silent period in human immunodeficiency virus-related peripheral neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2004;9:224–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2004.09400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C, Tseng T, Lin Y, Chiang M, Lin W, Hsieh S. Cutaneous innervation in Guillain-Barré syndrome: pathology and clinical correlations. Brain. 2003;126:386–397. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periquet MI, Novak V, Collins MP, Nagaraja HN, Erdem S, Nash SM, et al. Painful sensory neuropathy: prospective evaluation using skin biopsy. Neurology. 1999;53:1641–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.8.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perretti A, Nolano M, De Joanna G, Tugnoli V, Iannetti G, Provitera V, et al. Is Ross syndrome a dysautonomic disorder only? An electrophysiologic and histologic study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00323-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger GL, Ray M, Burcus NI, McNulty P, Basta B, Vinik AI. Intraepidermal nerve fibers are indicators of small-fiber neuropathy in both diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1974–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polydefkis M, Yiannoutsos CT, Cohen BA, Hollander H, Schifitto G, Clifford DB, et al. Reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Neurology. 2002;58:115–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattrini C, Tavakoli M, Jeziorska M, Kallinikos P, Tesfaye S, Finnigan J, et al. Surrogate markers of small fiber damage in human diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes. 2007;56:2148–54. doi: 10.2337/db07-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Said G. Small fiber involvement in peripheral neuropathies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:601–2. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000093103.34793.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago S, Espinosa ML, Perez-Conde MC, Merino M, Ferrer T. [Small fiber dysfunction in peripheral neuropathies] Rev Neurol. 1999;28:543–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuller TB, Hermann K, Baron R. Quantitative assessment and correlation of sympathetic, parasympathetic, and afferent small fiber function in peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol. 2000;247:267–72. doi: 10.1007/s004150050582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sghirlanzoni A, Pareyson D, Lauria G. Sensory neuron diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:349–61. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70096-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma KR, Saadia D, Facca AG, Resnick S, Ayyar DR. Diagnostic role of deep tendon reflex latency measurement in small-fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:223–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2007.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shun CT, Chang YC, Wu HP, Hsieh SC, Lin WM, Lin YH, et al. Skin denervation in type 2 diabetes: correlations with diabetic duration and functional impairments. Brain. 2004;127:1593–605. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shy ME, Frohman EM, So YT, Arezzo JC, Cornblath DR, Giuliani MJ, et al. Quantitative sensory testing: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2003;60:898–904. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058546.16985.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone D, Nolano M, Johnson T, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy W. Intradermal injection of capsaicin in humans produces degeneration and subsequent reinnervation of epidermal nerve fibers: Correlation with sensory function. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8947–8959. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08947.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG, Ramachandran P, Tripp S, Singleton JR. Epidermal nerve innervation in impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes-associated neuropathy. Neurology. 2001;57:1701–4. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG, Russell J, Feldman EL, Goldstein J, Peltier A, Smith S, et al. Lifestyle intervention for pre-diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1294–9. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Lauria G. Skin biopsy in the management of peripheral neuropathy. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:632–42. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70172-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen L, Molyneaux L, Yue DK. The level of small nerve fiber dysfunction does not predict pain in diabetic Neuropathy: a study using quantitative sensory testing. Clin J Pain. 2006a;22:261–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000169670.47653.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen L, Molyneaux L, Yue DK. The relationship among pain, sensory loss, and small nerve fibers in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006b;29:883–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stögbauer F, Young P, Kuhlenbäumer G, Kiefer R, Timmerman V, Ringelstein E, et al. Autosomal dominant burning feet syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67:78–81. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.67.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumner CJ, Sheth S, Griffin JW, Cornblath DR, Polydefkis M. The spectrum of neuropathy in diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. Neurology. 2003;60:108–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.60.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truini A, Galeotti F, Romaniello A, Virtuoso M, Iannetti GD, Cruccu G. Laser-evoked potentials: normative values. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:821–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truini A, Romaniello A, Galeotti F, Iannetti GD, Cruccu G. Laser evoked potentials for assessing sensory neuropathy in human patients. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:25–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walk D, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Davey C, Kennedy WR. Concordance between epidermal nerve fiber density and sensory examination in patients with symptoms of idiopathic small fiber neuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;255:23–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KD, Lee KM, Deshpande S, Duerksen-Hughes P, Boss JM, Pohl J. The neuron-specific protein PGP 9.5 is a ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase. Science. 1989;246:670–3. doi: 10.1126/science.2530630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambelis T, Karandreas N, Tzavellas E, Kokotis P, Liappas J. Large and small fiber neuropathy in chronic alcohol-dependent subjects. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2005;10:375–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Kitch D, Evans S, Hauer P, Raman S, Ebenezer G, et al. Correlates of epidermal nerve fiber densities in HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2007;68:2113–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264888.87918.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]