Abstract

The lipophilicity of a set of 5-HT2A ligands was determined using immobilized-artificial-membrane chromatography, a method that generates values well-correlated with octanol-water partition coefficients. For agonists, a highly significant linear correlation was observed between binding affinity and lipophilicity. For ligands exhibiting partial agonist or antagonist properties, the lipophilicity was consistently higher than would be expected for an agonist of comparable affinity. The results suggest a possible method for distinguishing agonists from antagonists in high-throughput screening when a direct assay for functional activity is either unavailable or impractical.

Keywords: Lipophilicity, Binding affinity, Functional activity, 5-HT2A receptor

1. Introduction

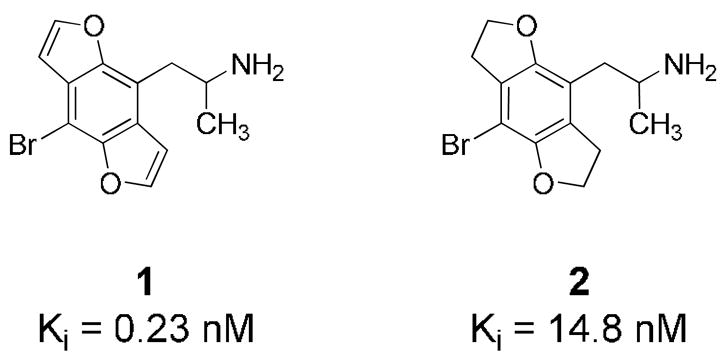

The 5-HT2A receptor, known to play a key role in the action of psychedelics as well as being a therapeutic target for the treatment of schizophrenia, has been a focus of SAR studies in our laboratories for many years. A particularly interesting fact that seemed to invite further investigation into the SAR of this receptor was our previously reported discovery1 of the greatly enhanced in vitro and in vivo potency of benzodifuran agonist 1 (Figure 1) relative to its saturated counterpart 2.

Figure 1.

Binding affinity of benzodifuran 1 and tetrahydrobenzodifuran 2 at [3H]MDL 100,907-labeled rat cortical 5-HT2A receptors.

The increased activity of 1, the first non-ergoline to surpass the potency of the hallucinogen LSD in animal behavioral assays, had not been anticipated based on previous conceptions of the factors determining affinity at the 5-HT2A receptor. In particular, it was difficult to imagine how the difference in activity between 1 and 2 could be explained using a 3-D receptor binding site model, as the shape of the molecule and relative positions of the heteroatoms are virtually identical for the two compounds.

One notable physical difference between 1 and 2 was observed before any pharmacological studies had been initiated: when a sample of the hydrochloride salt of 1 was being dissolved for proton NMR analysis, it went only with difficulty into D2O, in contrast to the behavior of the HCl salt of 2, which dissolved readily. (This difference is not entirely surprising given the fact that the solvent THF is miscible with water, whereas furan is not.) When the data revealing the high potency of 1 were later obtained, we considered three possibilities: that it was highly active due to the decreased hydrogen-bond acceptor ability of the furan oxygen atoms in 1 relative to the dihydrofuran oxygen atoms of 2 (as studies2–4 have suggested that the ether oxygen substituents in 2 and related phenethylamines act as hydrogen-bond acceptors for key threonine and serine residues5 in the 5-HT2A receptor pocket); due to the extended aromaticity of the fused 3-ring system of 1; or due to the increased lipophilicity of 1.

To investigate the first possibility, we decided to synthesize a compound in which the hydrogen-bonding capability at the position of the furan oxygen atoms is further reduced or eliminated. Fluorine has been employed as a bioisostere of oxygen, but is an extremely weak hydrogen bond acceptor.6,7 Therefore the fluoro derivative 3 (Figure 2) was chosen as a synthetic target with diminished H-bonding ability and which would present no additional bulk that might occlude side chains in the receptor pocket. To test the second possibility, that the extended aromaticity of 1 was responsible for its enhanced activity, the carbon analog 4 was also selected for synthesis.

Figure 2.

Fluoro and carbon analogs of benzodifuran 1.

Finally, to test the third possibility and thoroughly investigate the potential role of lipophilicity in the activity of this series, we decided to measure the lipophilicity of 1–4 and a number of related phenethylamine type 5-HT2A receptor ligands.

We chose immobilized-artificial-membrane (IAM) chromatography8 as a convenient technique for quantifying the lipophilicity of 1 and 2, as well as that of a number of comparison compounds known to be active at the 5-HT2A receptor. Immobilized artificial membranes are lipids bonded to silica surfaces via a covalent link at the end of one of the constituent long-chain fatty acids. They mimic cell membranes, and capacity factors k′IAM measured using IAM-packed HPLC columns correlate well with equilibrium partition coefficients of solutes partitioned between liposomes and aqueous buffer solutions. Additionally, Ong et al.9 have reported that, for substituted phenethylamines such as a number of those examined in the current study, there is a linear relationship between the log octanol-water partition coefficient (log P) and the log IAM capacity factors (log k′IAM) with an excellent degree of correlation (r = 0.985). Thus, for this set of compounds, either of these experimental techniques can be considered a valid way to quantify lipophilicity.

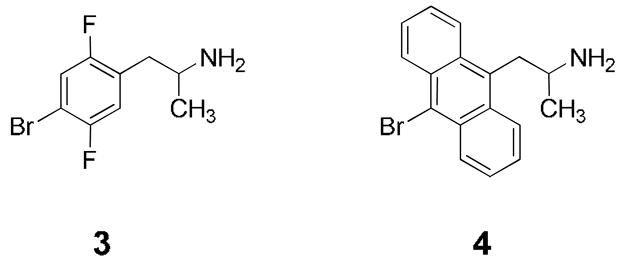

The set of comparison compounds in this study (Figure 3) comprised all those that were immediately accessible in our laboratory and for which 5-HT2A receptor binding and functional activity data were already available or could be readily obtained.

Figure 3.

Structures of ligands 5–24.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

(All chiral compounds discussed in the current work, either new or previously reported, were synthesized and tested as racemates.)

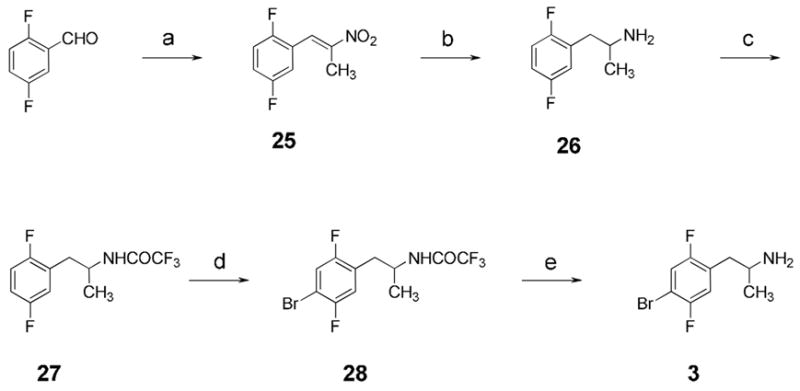

The synthesis of fluorinated analog 3 is depicted in Scheme 1. The chemistry is relatively straightforward, utilizing Henry condensation of 2,5-difluorobenzaldehyde with nitroethane, followed by reduction, protection, bromination, and finally deprotection to afford the target compound. The bromination of 27 is noteworthy, as the two fluorine atoms were found to substantially deactivate the ring toward electrophilic substitution. It was therefore necessary to employ the highly reactive conditions described by Derbyshire et al.,10 in which deactivated arenes were brominated in good yields using a mixture of sulfuric acid, water, bromine, and silver sulfate.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of fluorinated phenethylamine derivative 3.a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) EtNO2, c-hexNH2, HOAc, 91%; (b) NaBH4, BF3·OEt, 77%; (c) (CF3CO)2O, Et3N, 66%; (d) Br2, Ag2SO4, H2SO4, 44%; (e) NaOH, H2O/MeOH, 50%.

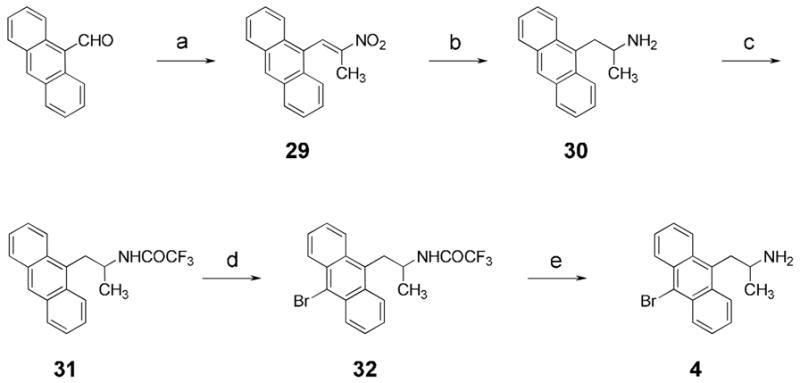

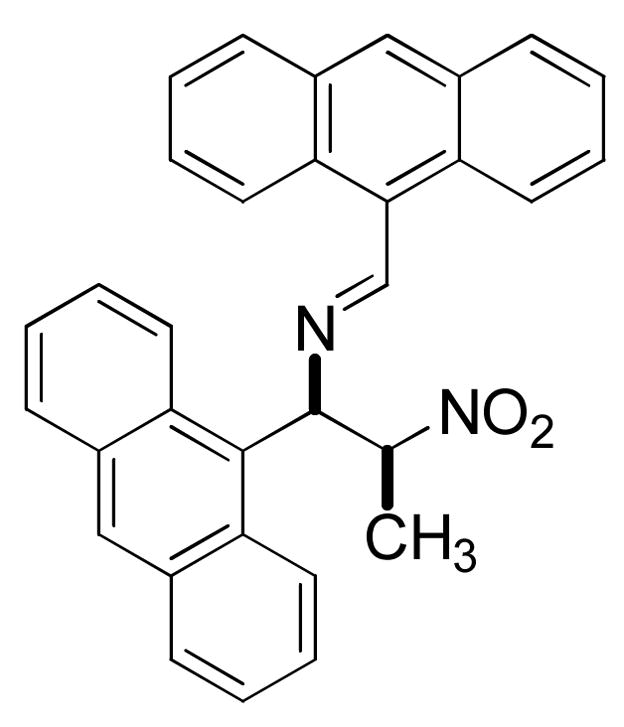

The anthracene derivative 4 was prepared in similar fashion, as shown in Scheme 2. The initial condensation of 9-anthraldehyde with nitroethane proved problematic employing the usual ammonium acetate catalyst; yields of the desired nitropropene 29 were no better than 40%. Spectral data (proton NMR) of the major side product, which accounted for almost all the material not converted to 29, were consistent with a mixture of stereoisomers of the nitroimine in Figure 4.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of anthracene derivative 4.a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) EtNO2, piperidinium acetate, 97%; (b) LiAlH4, 47%; (c) (CF3CO)2O, Et3N, 33%; (d) Bu4NBr3, HOAc, 82%; (e) NaOH, H2O/MeOH, 92%.

Figure 4.

Nitroimine side product observed in NH4OAc-catalyzed Henry condensation of 9-anthraldehyde and nitroethane.

This product is analogous to an imine observed by Shulgin11 as a major side product in the condensation of nitropropane with 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde. Shulgin’s solution to the problem, replacing the ammonium catalyst with a salt of a secondary amine, also worked in this case, increasing the yield of 29 to 97%.

Reduction with lithium aluminum hydride followed by the usual protection, bromination, and deprotection steps completed the synthesis of 4.

2.2. Receptor Binding and Functional Activity

Previously published Ki values for the ability of the compounds to displace the 5-HT2A antagonist [3H]ketanserin from rat cortical homogenates were used when available. We chose to use data from antagonist-labeled receptors in order to maximize the size of our data set, as more antagonist displacement data were available for 5-HT2A ligands than agonist displacement data. Although it would have been preferable to test all compounds at the same time and with the same radioligand, for practical reasons we chose to use previously published data, although much of it originated in our lab, where available. The remaining compounds were assayed against the antagonist [3H]MDL 100,907,12 again in rat cortical homogenates. Functional activity of test compounds at the 5-HT2A receptor, where not previously known, was determined indirectly using a drug discrimination assay in rats trained to distinguish the 5-HT2A agonist LSD from saline; agonists at the 5-HT2A receptor generally substitute for LSD.13 Compounds exhibiting partial substitution in this assay are termed “partial agonists” here, although it is difficult to distinguish a lack of full efficacy at the receptor from possible disruption of the behavioral assay due to activation of other receptor subtypes. Data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Binding affinity at antagonist-labeled 5-HT2A receptors, lipophilicity, efficacy, and affinity-normalized lipophilicity for 1–4 and selected comparison compounds 5–24.

| Compound (code/name) | Ki (nM) ketanserin | Ki (nM) MDL 100,907 | Lipophilicity (IAM.PC α) | Efficacy* | Affinity-normalized lipophilicity, pLn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, BDFLY | 0.23 ± 0.03 † | 5.188 | A | −0.15 | |

| 2, BFLY | 18 ± 1a | 14.8 ± 1.6 † | 0.893 | A | −0.08 |

| 5, DOI | 19b | 0.965 | A | 0.00 | |

| 6, DOTFM | 33.0 ± 5.0c | 1.009 | A | 0.13 | |

| 7, DOB | 22 ± 3a; 41 ± 5b | 0.608 | A | −0.04 | |

| 8, 2CBFLY | 34 ± 2a | 0.667 | A | −0.04 | |

| 9, DOEt | 100b | 0.678 | A | 0.18 | |

| 10, DOM | 100b | 0.296 | A | −0.18 | |

| 11, psilocin | 323 † | 0.191 | A | −0.13 | |

| 12, Z7d | 351 ± 47 † | 0.312 | A | 0.10 | |

| 13, DMT | 1636 † | 0.262 | A | 0.33 | |

| 14, 2CHFLY | 2300 ± 170a | 0.118 | A | 0.05 | |

| 15, mescaline | 5500 ± 600e | 0.048 | A | −0.16 | |

|

| |||||

| 16, BBOX | 422 ± 16f | 1.116 | B | 0.69 | |

| 17, SBatg | 476 ± 189 † | 0.373 | B | 0.24 | |

| 18, HFLY | 2010 ± 83a | 0.162 | B | 0.16 | |

| 19, 2,5-DMA | 5200b | 0.116 | B | 0.21 | |

|

| |||||

| 20, ritanserin | 1.7 ± 0.2h | 36 ± 6h | 40.233 | C | 1.14 |

| 21, PEd | 59 ± 2 † | 1.887 | C | 0.52 | |

| 22, BisTOMd | 177 ± 26 † | 2.260 | C | 0.82 | |

| 4, ANTH | 313 ± 106 † | 80.076 | C | 2.48 | |

| 3, BDFA | 2505 ± 441 † | 0.808 | C | 0.90 | |

| 23, T70i | 3676 † | 0.154 | C | 0.26 | |

| 24, T72i | 4611 † | 0.147 | C | 0.28 | |

determined indirectly using animal bioassay: A = agonist, B = partial agonist, C = antagonist.

previously unpublished data.

Monte, 1996, ref. 3.

Seggel, 1990, ref. 19.

Nichols, 1994, ref. 22.

Shulgin, 1991, ref. 23.

Monte, 1997, ref. 24.

Monte, 1995, ref. 25.

Parker, 1998, ref. 26.

Johnson et al., 1996, ref. 12.

Blair, 1999, ref. 13.

2.3. Requirements for Receptor Activation

We found that fluoro analog 3 and especially carbon analog 4 bind with reasonable affinity to the 5-HT2A receptor, but the drug discrimination data reveal that they lack agonist activity. Thus the oxygen substituents of 1 and 2 appear to be required for efficacy in the phenethylamine series, and neither the extremely weak hydrogen bonding capability of the fluoro substituents of 3 nor the extended aromaticity of 4 is sufficient for receptor activation.

2.4. Lipophilicity Measurements

Lipophilicity was determined by HPLC using an immobilized-artificial-membrane column containing phosphatidylcholine head groups (IAM.PC). The experimental techniques employed and the characteristics of the IAM.PC surface have been described in detail.8,9,14–16

Measured IAM.PC α values, which are the capacity factors k′IAM divided by the capacity factor of a standard compound, are given in Table 1.

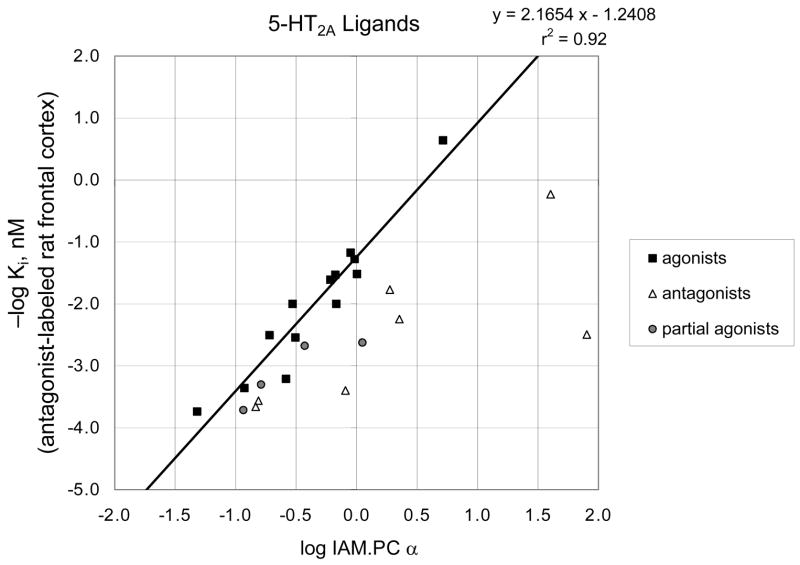

2.5. Correlation of Agonist Lipophilicity with Binding Affinity

When the log binding affinity at antagonist-labeled 5-HT2A receptors is plotted against the log IAM.PC α (corrected capacity factor), the graph shown in Figure 5 results. Receptor affinity and lipophilicity increase moving up and to the right, respectively. The data points for compounds classified as agonists lie very nearly in a straight line (r2 = 0.92). All the antagonists and partial agonists lie to the right of the line, with many of the antagonists lying far to the right.

Figure 5.

Log affinity at antagonist-labeled 5-HT2A receptors versus log IAM.PC α.

The excellent correlation obtained in this graph validates our initial conjecture that the high potency of 1 was related to its increased lipophilicity (compound 1 is the dark square nearest the line in the upper right corner). The graph also indicates clearly that for those compounds that are agonists, the relationship between lipophilicity and binding affinity is linear.

We note that this high correlation of r2 = 0.92 was obtained despite the fact that some data were obtained at different times and with different radioligand antagonists, indicating that any random error introduced must have been relatively small. (In future investigations we plan to determine whether this correlation can be further improved by eliminating these possible sources of variance.)

These data provide new insight into the relationship between lipophilicity and potency in this series. Barfknecht et al.17 observed in 1975 an apparent parabolic relation between log P and log human in vivo potency for a series of hallucinogenic phenethylamines, with an optimal log P of 3.14. The drop in activity with increasing lipophilicity occurred as the 4-alkyl substituent in 4-alkyl-2,5-dimethoxyamphetamines was lengthened. Indeed, in a 1977 study of the activity of phenethylamines in stimulating serotonin receptors in sheep umbilical artery, Nichols et al.18 speculated that the observed drop in activity with increasing log P “might be due to excessive steric bulk in the para position, rather than to increased hydrophobic character per se,” and noted that there appeared to be a sharp limit (5–6 Å) on the length of the para substituent in active compounds. Thirteen years later, Seggel et al.19 showed that this decrease in activity was due not to a lack of affinity (the 4-hexyl compound exhibited a Ki of 2.5 nM for ketanserin-labeled 5-HT2 receptors) but to a lack of efficacy: compounds with long 4-alkyl substituents appeared to be acting as antagonists.

Now that a wider range of agonists, including the exceptionally lipophilic 1, have been examined in the current study, it is clear that for agonists the relationship between lipophilicity (log P or k′IAM) and log in vitro affinity is linear. The log P of compound 1, calculated from the measured k′IAM using the linear relationship mentioned earlier, is approximately 4.09, significantly higher than the 3.14 previously believed to be optimal.

Thus, it would appear that aromatization of 2 to 1 diminishes the strength of hydrogen bonds to the furan oxygen20 (but not to such a degree that the receptor-activating serine residues fail to form H-bonds as with 3) and thereby dramatically increases the lipophilicity of the molecule, resulting in a very active compound.

2.6. Lipophilicity at Isoaffinity as a Potential Correlate of Functional Activity

A key observation from Figure 5 is that the compounds that lack agonist activity in the rat behavioral model, or that are known to be antagonists, lie well to the right of the agonist line, and those that show only partial agonist activity lie closer to the line but still trend to the right of it. In other words, each antagonist is more lipophilic than an agonist with the same affinity would be.

This phenomenon can be quantified by defining a value Ln, the affinity-normalized lipophilicity, as the lipophilicity of the ligand in question divided by the lipophilicity that would be expected for an agonist with the same affinity as determined by the line previously fit to the agonist data.

Then the logarithmic form of the parameter, pLn = −log Ln, becomes a convenient descriptor of how many log units to the left or right of the agonist line a given point lies on a log-log plot such as Figure 5.

It stands to reason that agonists acquire a greater portion of their binding affinity through interaction with relatively hydrophilic amino acid side chains in the receptor pocket than do antagonists. Antagonists in general bind to a greater degree through hydrophobic interactions with the receptor and by definition do not exert critical conformation-changing binding forces on amino acid residues inside the pocket. Thus, in order to have the same affinity as a given agonist, they must generally be more lipophilic than that agonist. The pLn metric quantifies this property and thereby provides an indication of agonist/antagonist properties of ligands if a line for agonists on the affinity-lipophilicity plot has already been determined. A pLn value close to zero indicates that the ligand is likely to be an agonist, and a pLn value greater than about 0.5 indicates the opposite. In the current data set, twelve of the thirteen agonists, and none of the antagonists, have pLn values less than 0.20 (Table 1). Moreover, five of the seven antagonists have pLn values greater than 0.50. The partial agonists tend to lie in between these two limits.

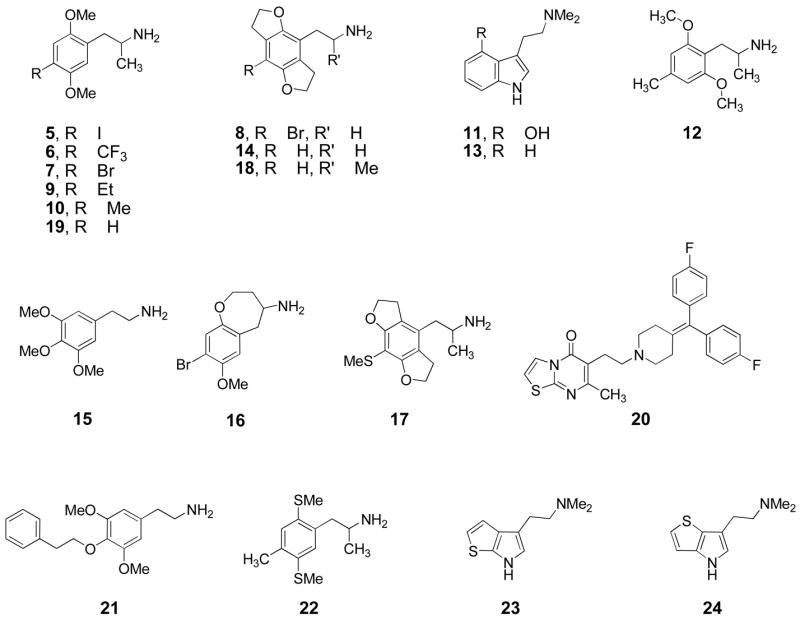

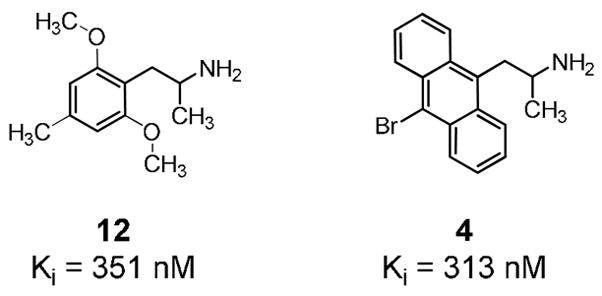

In the current data set, comparison of agonist 12 and antagonist 4 is particularly instructive (Figure 6). They have nearly identical affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor (313 nM vs. 351 nM) but 4 is ~2.5 log units more lipophilic than 12. Thus, it binds to the receptor by virtue of its lipophilicity and lacks appropriate functional groups, such as the 2- and 6-alkoxy substituents of 12, to activate the receptor.

Figure 6.

Binding affinity of agonist 12 and antagonist 4 at antagonist-labeled rat cortical 5-HT2A receptors.

We should emphasize that the data do not support the conclusion that antagonists are on average more lipophilic than agonists; for example antagonist 3 is far less lipophilic than agonist 1. Rather, it is the affinity-normalized lipophilicity pLn, calculable only after a function relating lipophilicity to binding affinity for a set of agonists has been determined, that appears to be an indicator of functional activity.

3. Conclusions

The data support the conclusion that the enhanced potency of 1 over 2 is due to the fact that the lipophilicity is increased while key elements of the 5-HT2A pharmacophore (the furan oxygen substituents) are retained. For the full set of 5-HT2A receptor ligands examined, the correlation between lipophilicity and binding affinity is a good linear fit for agonists. This correlation allows the specification of a new parameter, the affinity-normalized lipophilicity Ln, as a potential indicator of agonist versus antagonist activity. Further work is planned to verify the current findings by increasing the size of the data set as well as measuring efficacy directly by second-messenger detection; we also plan to explore the scope of the method for additional 5-HT2A ligand chemotypes and determine whether it can be extended to other monoamine receptors. If so, it may prove useful in high-throughput screening, allowing agonists to be distinguished from antagonists in cases where functional activity of ligands cannot easily be measured directly.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

All reagents were commercially available and were used without further purification unless otherwise indicated. Anhydrous THF was obtained by distillation from benzophenone-sodium under nitrogen. Melting points were taken on a Mel-Temp apparatus and are uncorrected. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded using a 500 MHz Varian VXR-500S spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported in δ values ppm relative to tetramethylsilane as an internal reference for those spectra obtained in CDCl3, and relative to the HDO resonance, assigned the value of 4.630 ppm, for those spectra obtained in D2O. Elemental analyses were performed by H. D. Lee at the Purdue University Microanalysis Laboratory and are within 0.4% (absolute) of the calculated values. Most reactions were carried out under an inert atmosphere of dry argon or nitrogen.

4.1.1 1-(2,5-Difluorophenyl)-2-nitropropene (25)

A mixture of 2.0 g (14 mmol) of 2,5-difluorobenzaldehyde, 2.2 g (29 mmol) of nitroethane, and 1.4 g (14 mmol) of cyclohexylamine in 12 mL of acetic acid was heated and stirred at 80 °C under argon for 5 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, poured into 200 mL of water, and extracted 3x with CH2Cl2. The pooled extracts were washed twice with water and once with 5% aqueous NaOH. The resulting solution was dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated to leave 2.55 g (91%) of 25 as a clear yellow oil which crystallized on standing overnight under vacuum. An analytical sample gave light yellow plates from hexane: mp 48–49.5 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.39 (s, 3, CH3), 7.08 (m, 1, ArH), 7.14 (m, 2, ArH), 8.03 (s, 1, vinylic H). Anal. Calcd for C9H7F2NO2: C, 54.28; H, 3.54; N, 7.03. Found: C, 54.01; H, 3.61; N, 6.93.

4.1.2. 1-(2,5-Difluorophenyl)-2-aminopropane (26)

In a dry round-bottomed flask were placed 2.51 g of sodium borohydride and 105 mL of dry THF. The flask was cooled to 0 °C under argon and 10.4 mL of boron trifluoride diethyl etherate was added via syringe. After the addition, the flask was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 15 min. A solution of 2.77 g of 25 in 35 mL of THF was added dropwise via syringe, and the reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 5.5 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature, quenched carefully by the (initially dropwise) addition of water (175 mL), acidified with 90 mL of 2 M HCl, and heated at 80–85 °C for 2 h. After cooling to room temperature, most of the THF was removed under reduced pressure and the remaining material was washed once with Et2O. The aqueous layer was separated, made strongly alkaline with 10% aqueous NaOH, and extracted three times with Et2O. The Et2O extracts were dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated, yielding 1.83 g (77%) of the crude amine 26 as a yellow oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.13 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.4 Hz), 1.88 (bs, 2, NH2), 2.60 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 7.7, 13.3 Hz), 2.71 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 5.7, 13.3 Hz), 3.21 (sextet, 1, ArCH2CH, J = 6.3 Hz), 6.86–6.93 (complex m, 2, ArH), 6.98 (dt, 1, ArH, J = 4.5, 8.9 Hz). The amine was converted to the trifluoroacetamide 58 without further characterization.

4.1.3. N-Trifluoroacetyl-1-(2,5-difluorophenyl)-2-aminopropane (27)

To a solution of 1.3 g (7.6 mmol) of crude 26 in 100 mL of CH2Cl2 under argon was added 1.26 mL (9.13 mmol) of triethylamine. A solution of 3.27 mL (23.2 mmol) of trifluoroacetic anhydride in 10 mL of CH2Cl2 was added dropwise via syringe with stirring. The solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 min, and the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure. The residue was partitioned between Et2O and water. The Et2O phase was dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated, and the residue (2.06 g) was recrystallized from EtOAc-hexane, yielding 1.33 g (66%) of 27 as beige crystals: mp 90–92 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.27 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.87 (d, 2, ArCH2, J = 6.9 Hz), 4.29 (septet, 1, ArCH2CH, 7.1 Hz), 6.23 (bs, 1, NH), 6.87–6.95 (complex m, 2, ArH), 7.02 (dt, 1, ArH, J = 4.4, 9.3 Hz). Anal. Calcd for C11H10F5NO: C, 49.45; H, 3.77; N, 5.24. Found: C, 49.17; H, 3.52; N, 5.01.

4.1.4. N-Trifluoroacetyl-1-(4-bromo-2,5-difluorophenyl)-2-aminopropane (28)

To 3.66 g of water in a 100 mL round-bottomed flask was added 41.6 g of 98% sulfuric acid. To the warm stirred solution was added 1.22 g of crystalline 27. When all the solid had dissolved, the flask was cooled to room temperature, and 0.76 g of elemental bromine was added, followed by 0.76 g of silver sulfate. The mixture was stirred 1 h at room temperature and then poured carefully over ice. The quenched mixture was partitioned between Et2O and H2O, and the Et2O phase was washed three times with H2O and twice (carefully) with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated. The solid residue (2.35 g) was dissolved in 1.2 mL of hot EtOAc and diluted with 160 mL of warm hexane. On cooling, 0.694 g (44%) of 28 precipitated as white crystals: mp 128–130 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.27 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.7 Hz), 2.85 (d, 2, ArCH2, J = 6.7 Hz), 4.28 (septet, 1, ArCH2CH, J = 7.1 Hz), 6.13 (bs, 1, NH), 6.97 (dd, 1, ArH, J = 6.2, 8.3 Hz), 7.29 (dd, 1, ArH, J = 5.6, 8.7 Hz). Anal. Calcd for C11H9BrF5NO: C, 38.17; H, 2.62; N, 4.05. Found: C, 37.99; H, 2.49; N, 3.82.

4.1.5. 1-(4-Bromo-2,5-difluorophenyl)-2-aminopropane hydrochloride (3)

A solution of 2 g of NaOH in 10 mL of H2O was added to a solution of 0.500 g of amide 28 in 40 mL of methanol. The mixture was stirred under argon for 24 h at room temperature. The methanol was removed by rotary evaporation and the remaining mixture was partitioned between Et2O and H2O. The Et2O phase was washed with H2O, dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated. The residue was dissolved in 2 mL of EtOH and acidified with 1 mL of 2 M anhydrous HCl in ethanol. Dilution with Et2O produced a fine white precipitate of 0.205 g (50%) of the hydrochloride salt: mp 193–194 °C. 1H NMR (D2O) δ 1.12 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.7 Hz), 2.75 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 7.3, 14.2 Hz), 2.81 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 6.6, 14.2 Hz), 3.47 (sextet, 1, ArCH2CH, J = 6.8 Hz), 7.04 (dd, 1, ArH, J = 6.4, 8.7 Hz), 7.31 (dd, 1, ArH, J = 5.8, 9.0 Hz). Anal. Calcd for C9H11BrClF2N: C, 37.72; H, 3.87; N, 4.89. Found: C, 37.63; H, 3.69; N, 4.68.

4.1.6. 1-(9-Anthracenyl)-2-nitropropene (29)

A mixture of 4.0 g of 9-anthraldehyde, 33 mL of nitroethane, and 2.81 g of piperidinium acetate in a round-bottomed flask under an argon atmosphere was placed into an oil bath already heated to 90 °C and stirred for exactly 30 min. The flask was removed from the oil bath and cooled under running water, then poured into 200 mL water. The mixture was extracted twice with CH2Cl2. The organic phases were combined, washed with water, dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated, yielding 4.95 g (97%) of 29 as bright orange crystals, quite clean by proton NMR. An analytical sample was recrystallized from THF/hexane: mp 142–142.5 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.01 (s, 3, CH3), 7.54 (pentet, 4, ArH, J = 7 Hz), 7.90 (d, 2, ArH, J = 8.5 Hz), 8.07 (d, 2, ArH, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.54 (s, 1, ArH), 8.79 (s, 1, vinylic H). Anal. Calcd for C17H13NO2: C, 77.55; H, 4.98; N, 5.32. Found: C, 77.35; H, 4.76; N, 5.15.

4.1.7. 1-(9-Anthracenyl)-2-aminopropane (30)

A solution of 4.55 g of 29 in 160 mL of anhydrous THF was added dropwise under argon to a stirred suspension of 4.00 g of LiAlH4 in 160 mL of anhydrous THF. The mixture was stirred and heated at reflux for 42 h. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and slowly quenched, sequentially, with 4.5 mL of 2-propanol, 4.5 mL of 15% aqueous NaOH, and 16 mL of water. The resulting solids were filtered off and the filtrate was evaporated. The residue was partitioned between 200 mL of Et2O and 200 mL of 0.5 M HCl. The aqueous phase was washed twice with Et2O and basified with aqueous NaOH, then extracted 3x with Et2O. The Et2O extracts were dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated, yielding 1.90 g (47%) of the crude free amine 30 as a viscous tan oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.28 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.2 Hz), 3.54 (sextet, 1, ArCH2CH, 6.7 Hz), 3.66 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 7.6, 14.2 Hz), 3.71 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 6.0, 14.2 Hz), 7.47 (t, 2, ArH, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.51 (t, 2, ArH, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.01 (d, 2, ArH, J = 8 Hz), 8.33 (d, 2, ArH, J = 9 Hz), 8.37 (s, 1, ArH). This product was converted to the trifluoroacetamide derivative 31 without further characterization.

4.1.8. N-Trifluoroacetyl-1-(9-anthracenyl)-2-aminopropane (31)

A solution of 1.88 g (8 mmol) of the crude amine 30 and 1.12 mL (0.810 g, 8 mmol) of triethylamine in 100 mL of dichloromethane was placed under argon and cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. Trifluoroacetic anhydride (2.26 mL, 16 mmol) was added dropwise via syringe with stirring. The ice bath was removed and the solution was stirred another 2 h, after which the reaction mixture was worked up as described previously. Recrystallization of the crude material from EtOAc/hexane gave 0.869 g (33%) of 31 as a yellow crystalline solid: mp 203–204 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.21 (d, 3, CH3, J = 7 Hz), 3.78 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 9, 14 Hz), 4.07 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 5.5, 14 Hz), 4.54 (broad septet, 1, ArCH2CH, J = 8 Hz), 6.36 (bs, 1, NH), 7.48 (t, 2, ArH, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.57 (t, 2, ArH, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.03 (d, 2, ArH, J = 8.5 Hz), 8.39 (d, 2, ArH, J = 9 Hz), 8.42 (s, 1, ArH). Anal. Calcd for C19H16F3NO: C, 68.88; H, 4.87; N, 4.23. Found: C, 68.82; H, 4.76; N, 4.08.

4.1.9. N-Trifluoroacetyl-1-(10-bromoanthracen-9-yl)-2-aminopropane (32)

A solution of 0.500 g of 31 in 20 mL warm acetic acid was cooled to room temperature and 0.786 g tetrabutylammonium tribromide was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction mixture was partitioned between Et2O and H2O. The Et2O phase was separated, washed with H2O and brine, dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated. The solid yellow residue was recrystallized from EtOAc/hexane to give 0.507 g (82%) of 32 as a fine yellow crystalline solid: mp 215–216 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.19 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.5 Hz), 3.77 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 9.5, 14.5 Hz), 4.10 (dd, 1, ArCH2, J = 5.5, 14.5 Hz), 4.52 (broad septet, 1, ArCH2CH, J = 7 Hz), 6.36 (bs, 1, NH), 7.62 (m, 4, ArH), 8.45 (bs, 2, ArH), 8.64 (m, 2, ArH). Anal. Calcd for C19H15BrF3NO: C, 55.63; H, 3.69; N, 3.41. Found: C, 55.65; H, 3.48; N, 3.19.

4.1.10. 1-(10-Bromoanthracen-9-yl)-2-aminopropane hydrochoride (4)

A solution of 2.4 g of NaOH in 12 mL of H2O was added to a solution of 0.350 g of amide 32 in 60 mL of methanol. The mixture was stirred under argon for 24 h at room temperature. The methanol was removed by rotary evaporation and the remaining mixture was partitioned between Et2O and H2O. The Et2O phase was washed with H2O, dried with MgSO4, filtered, and evaporated, leaving the free amine as a yellow solid. The solid was dissolved in 6 mL EtOH and neutralized with 2 M anhydrous HCl in ethanol. Et2O (100 mL) was slowly added. The hydrochloride salt precipitated and was collected by filtration and washed with Et2O. Yield 0.276 g (92%) of the hydrochloride salt as fine lemon-yellow crystals: mp >290 °C (dec.) 1H NMR (1:1 v/v DMSO-d6:D2O) δ 1.11 (d, 3, CH3, J = 6.4 Hz), 3.76 (sextet, 1, ArCH2CH, J = 7.6 Hz), 3.98 (m, 2, ArCH2), 7.75 (m, 4, ArH), 8.42 (d, 2, ArH, J = 7 Hz), 8.60 (d, 2, ArH, J = 7 Hz). Anal. Calcd for C17H17BrClN: C, 58.23; H, 4.89; N, 3.99. Found: C, 58.28; H, 4.88; N, 3.87.

4.2. Pharmacology—Radioligand Competition Assays in Rat Brain Homogenate

The procedure of Johnson et al.21 was employed with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 male Sprague Dawley whole rat brains (unstripped) were purchased from Harlan Bioproducts for Science, Inc. and dissected over dry ice. The frontal cortex tissue was homogenized (Kinematica Polytron, setting “4,” 2 × 20 seconds) in 4 volumes (w/v) of ice-cold 0.32 M sucrose and centrifuged at 36,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The pellet was again suspended in the same volume of sucrose, homogenized (Kinematica Polytron, setting “4,” 20 seconds), separated into aliquots of 4.5 mL, and stored at −70 °C.

For each experiment one aliquot of frontal cortex tissue was thawed and diluted with 25 volumes (w/v) of 50 mM Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Aldrich Chemicals) buffer, adjusted to pH 7.4 by HCl. The tissues were homogenized (Kinematica Polytron, setting “4,” 20 seconds) and incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C in a shaking water bath. The homogenate was then centrifuged twice at 36,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 minutes, with the pellet being resuspended in 25 volumes of Tris-HCl buffer in between. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended with 25 volumes of Te Pac buffer (0.5 mM Na2EDTA, 10.0 μM pargyline, 5.7 mM CaCl2, 0.1% Na2Ascorbate), homogenized using the Kinematica as above, and incubated for 10 minutes at 37 °C in a shaking water bath. The homogenate was then placed in an ice bath to cool. Binding was initiated by adding 800 μL of homogenate tissue to assay tubes containing 100 μL of [3H]MDL 100,907 (0.2 nM) and 100 μL of the competing drug solution or H2O. Non-specific binding was determined in the presence of cinanserin (10 μM). Binding assays were incubated for 15 minutes at 37 °C in a shaking water bath. Incubation was stopped by rapid vacuum filtration through GF/C filters using a Brandel Cell Harvester (Brandel Instruments, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The filters were washed twice with 5 mL aliquots of ice-cold Tris-HCl buffer, allowed to air dry and placed into scintillation vials containing 10 mL of Ecolite scintillation cocktail (ICN Biomedicals). Eight hours later the radioactivity was measured using liquid scintillation spectroscopy (Packard model 4430) at 37% efficiency. EC50 (nM) values were calculated from at least three experiments, each done in triplicate, by using GraphPad PRISM™.

4.3. Immobilized Artificial Membrane Chromatography

The retention times (tR, in minutes) were measured on an IAM.PC.DD column (Regis Technologies, Morton Grove, IL) using a mobile phase of 10 mM PBS buffered at pH 7.4. k′IAM was calculated from k′IAM = (tR − t0)/t0, where t0 is the retention time of an unretained compound, i.e., citric acid.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant DA02189 from NIDA. The authors also wish to thank Kim Hauer and Olga Lapina for the acquisition of IAM chromatography data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Parker MA, Marona-Lewicka D, Lucaites VL, Nelson DL, Nichols DE. J Med Chem. 1998;41:5148–5149. doi: 10.1021/jm9803525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westkaemper RB, Glennon RA. In: NIDA Research Monograph 146, Hallucinogens: An Update. Lin GC, Glennon RA, editors. NIDA; Rockville, MD: 1994. pp. 263–283. NIH Publication No. 94-3872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monte AP, Marona-Lewicka D, Parker MA, Wainscott DB, Nelson DL, Nichols DE. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2953–2961. doi: 10.1021/jm960199j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLean TH, Parrish JC, Braden MR, Marona-Lewicka D, Gallardo-Godoy A, Nichols DE. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5794–5803. doi: 10.1021/jm060656o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson MP, Wainscott DB, Lucaites VL, Baez M, Nelson DL. Brain Res. 1997;49:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunitz JD, Taylor R. Chem Eur J. 1997;3:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Some literature examples of fluorine-for-oxygen bioisosteric substitution: Kozikowski AP, Fauq AH, Powis G, Melder DC. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4528–4531.Kozikowski AP, Wu JP. Tet Lett. 1990;31:4309–4312.Andersen SM, Ebner M, Ekhart CW, Gradnig G, Legler G, Lundt I, Stütz AE, Withers SG, Wrodnigg T. Carbohydr Res. 1997;301:155–166.Appendino G, Tron GC, Cravotto G, Palmisano G, Annunziata R, Baj G, Surico N. Eur J Org Chem. 1999:3413–3420.Xu Y, Qian L, Prestwich GD. J Org Chem. 2003;68:5320–5330. doi: 10.1021/jo020729l.Shibata N, Ishimaru T, Nakamura M, Toru T. Syn Lett. 2004;14:2509–2512.Niida A, Tomita K, Mizumoto M, Tanigaki H, Terada T, Oishi S, Otaka A, Inui KI, Fujii N. Org Lett. 2006;8:613–616. doi: 10.1021/ol052781k.

- 8.Pidgeon C, Ong S, Liu H, Qiu X, Pidgeon M, Dantzig AH, Munroe J, Hornback WJ, Kasher JS, Glunz L, Szczerba T. J Med Chem. 1995;38:590–594. doi: 10.1021/jm00004a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong S, Liu H, Pidgeon C. J Chromat A. 1996:113–128. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derbyshire DH, Waters WA. J Chem Soc. 1950:573–577. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shulgin AT. Experientia. 1963;19:127–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02171586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson MP, Siegel BW, Carr AA. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1996;354:205–209. doi: 10.1007/BF00178722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blair JB, Marona-Lewicka D, Kanthasamy A, Lucaites VL, Nelson DL, Nichols DE. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1106–1111. doi: 10.1021/jm980692q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong S, Pidgeon C. Anal Chem. 1995;67:2119–2128. doi: 10.1021/ac00109a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Ong S, Glunz L, Pidgeon C. Anal Chem. 1995;67:3550–3557. doi: 10.1021/ac00115a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang CY, Cai SJ, Liu H, Pidgeon C. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1996;23:229–256. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barfknecht CF, Nichols DE, Dunn WJ., III J Med Chem. 1975;18:208–210. doi: 10.1021/jm00236a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols DE, Shulgin AT, Dyer DC. Life Sciences. 1977;21:569–576. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(77)90099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seggel MR, Yousif MY, Lyon RA, Titeler M, Roth BL, Suba EA, Glennon RA. J Med Chem. 1990;33:1032–1036. doi: 10.1021/jm00165a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsuda M, Touhara H, Nakanishi K, Kitaura K, Morokuma K. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:7189–7196. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson MP, Mathis CA, Shulgin AT, Hoffman AJ, Nichols DE. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;35:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90228-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols DE, Frescas S, Marona-Lewicka D, Huang X, Roth BL, Gudelsky GA, Nash JF. J Med Chem. 1994;37:4346–4351. doi: 10.1021/jm00051a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shulgin A, Shulgin A A. PIHKAL. Transform Press; Berkeley, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monte AP, Waldman SR, Marona-Lewicka D, Wainscott DB, Nelson DL, Sanders-Bush E, Nichols DE. J Med Chem. 1997;40:2997–3008. doi: 10.1021/jm970219x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monte AP. PhD Thesis. Purdue University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker MA. PhD Thesis. Purdue University; 1998. [Google Scholar]