Abstract

Retinoic acid–inducible gene (RIG)-I–like receptors (RLRs) are cytosolic RNA helicases that sense viral RNA and trigger signaling pathways that induce the production of type I interferons (IFNs) and proinflammatory cytokines. RLRs recognize distinct and overlapping sets of viruses, but the mechanisms that dictate this specificity were unknown. A new study now provides evidence for size-based discrimination of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) by RLRs and suggests how host cells recognize a variety of RNA viruses.

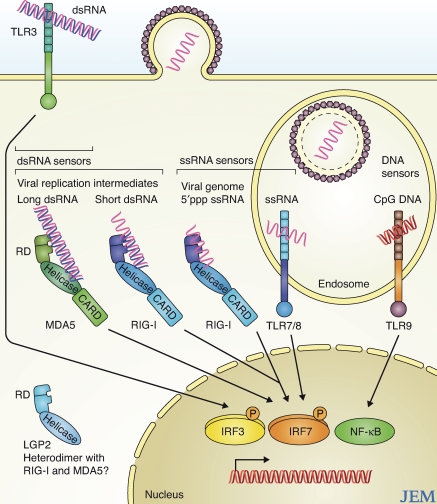

Viruses can initiate intracellular signaling in part through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and RLRs, which then trigger host immune responses. TLRs and RLRs function as pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) that engage specific pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) motifs, including viral RNA. TLR and RLR signaling activates IFN regulatory factors (IRFs) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), resulting in the expression of type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 1) (1). Type I IFNs then induce the expression of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes that have direct antiviral actions and modulate adaptive immunity by enhancing natural killer cell function, activating immature dendritic cells (2–4), and priming the survival and effector functions of T and B cells (5–9).

Figure 1.

Nucleic acid sensor molecules induce type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines. PRRs occupy specific intracellular sites that associate with the niche of different microbial pathogens. MDA5 and RIG-I both serve as cytoplasmic dsRNA receptors but distinguish their ligands in part by size; MDA5 binds to long dsRNA, whereas RIG-I binds short dsRNA. Among the TLRs, TLR3 recognizes dsRNA, TLR7/8 recognizes endosomal ssRNA, and TLR9 binds to endosomal CpG DNA. PRR activation initiates downstream signaling that in turn activates transcription factors, including IRF-3, IRF-7, and NF-κB. The resulting expression of type I IFNs, proinflammatory cytokines, and IFN-stimulated genes affect the innate immune response to confer pathogen resistance and enhance the adaptive immune response to infection.

RIG-I is the prototypical member of the RLR family, which also includes melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5 (MDA5) and laboratory of genetics and physiology 2 (LGP2). All RLRs have a C-terminal RNA helicase domain, whereas RIG-I and MDA5, but not LGP2, contain N-terminal tandem caspase activation recruitment domains (CARDs). Both RIG-I and LGP2 are regulated by a C-terminal repressor domain that is lacking in MDA5 (10). Recent studies have revealed that RIG-I and MDA5 detect different viruses (11, 12). The mechanism of PAMP recognition by RIG-I has been characterized (10, 13–16), but the MDA5 recognition mechanism was unknown. The study by Kato et al. (17) on page 1601 of this issue reveals the nature of MDA5 ligands and provides a basis for how MDA and RIG-I may differentially recognize PAMPs. Here, we discuss these findings in the context of recent advances made in the understanding of PAMP recognition and differentiation by RLRs and TLRs.

TLRs and RLRs direct the front line of immunity

Innate immunity mediated through PAMP recognition by PRRs is the earliest stage of immunity against viral infection. The subsequent modulation of the adaptive immune response by PRR signaling has been studied using cells and mice deficient in specific TLRs, RLRs, or their associated signaling adaptor proteins. Recent studies demonstrated, for example, that the absence of specific TLR pathways impairs adaptive immune responses against a variety of viruses (18, 19). RLR signaling also seems to be critical for the outcome of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), influenza virus, and encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) infection (11, 20, 21). In mice lacking RIG-I, MDA5, or the essential RLR adaptor molecule IFN promoter–stimulator 1, JEV, VSV, influenza virus, and ECMV were more virulent and replicated to higher levels than in wild-type mice, suggesting that RLR pathways are essential for controlling infection by these viruses (11, 21, 22). Innate immune programs can also mediate antiviral immunity independent of adaptive immunity. For example, IRF3 target genes induced by RLR signaling directly control viral replication in infected tissues (23, 24). Thus, depending on the nature of virus infection, TLRs and RLRs may work together or independently to mount an efficient immune response.

Discriminating between self- and viral RNAs

It is thought that the innate immune system protects the host from infection in a nonspecific way. However, several studies have revealed that PAMP ligand recognition exhibits specificity. This, along with differences in cellular location likely serve to distinguish self-RNA from nonself PAMP RNA, thus avoiding type I IFN induction in response to components of host nucleic acids. For example, TLR7 recognizes a specific motif within uridine-rich ribonucleotide sequences (25, 26), which are hypothesized to be unique to RNA viruses. TLR9 recognizes DNA PAMP ligands and triggers signaling through the MyD88 adaptor protein to induce type I IFN production (27). The recognition of nonself DNA ligands by TLR9 might also be sequence dependent, and some studies have implicated the sugar-base-backbone sequence of PAMP DNA as a recognition factor (28–30).

RLRs have been shown to recognize viral RNA as nonself PAMPs. Unlike TLRs, which are found either on the cell surface or within membrane-bound vesicles, RLRs are found in the cytoplasm where cellular RNA is also present (1). RIG-I preferentially recognizes single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) over dsRNA (15, 31). ssRNAs containing a terminal 5′ triphosphate (ppp), but not 5′OH or a 5′-methylguanosine cap, bind to the RIG-I repressor domain and promote a conformational change that activates RIG-I signaling (10, 13–16). RNA ligands of RIG-I are longer than 23 nucleotides, have a linear structure, and contain a uridine- or adenosine-rich ribonucleotide sequence (31–33). Host mRNA, tRNA, miRNA, snRNA, and rRNA are not ideal RIG-I ligands because their length, structure, 5′ end modifications, and interactions with ribonucleoproteins limit their recognition. Self-RNAs therefore do not typically trigger innate immune programs or type I IFN expression (34).

The mechanism by which MDA5 recognizes nonself RNA is less clear. MDA5 triggers innate immune signaling in response to EMCV infection and synthetic dsRNA, such as poly I:C (11, 20). But ssRNA viruses such as Dengue virus and West Nile virus, as well as Reovirus, a dsRNA virus, have also been shown to trigger signaling partially via MDA5 (12, 35). However, in these studies, MDA5 appeared only to amplify type I IFN production as compared with RIG-I, whose actions were essential to initiate innate immunity (12).

The study by Kato et al. (17) in this issue describes a plausible mechanism of RNA ligand recognition by MDA5, providing new insights into the differential roles of RLRs. The study reveals that MDA5 binding to dsRNA does not depend on its 5′ end modification, but rather on its length. dsRNAs with lengths of 2, 3, and 4 kb were shown to increasingly activate MDA5 signaling, whereas RIG-I recognized ssRNA and, to a lesser extent, short dsRNA motifs. These results help explain how reovirus can trigger both RIG-I and MDA5 signaling. The genome of reovirus comprises at least 10 segments of dsRNA that vary in length, including long (3.9 kbp), medium (2.2 kbp), and short (1.2 kbp) RNA segments. Kato et al. show that RIG-I and MDA5 recognize the short and long dsRNA segments of the reovirus genome, respectively. In the case of EMCV infection, the authors show that the viral genome forms long dsRNA via its antisense replication intermediate, and this dsRNA is recognized by MDA5 but not by RIG-I. On the other hand, VSV, which triggers RIG-I–dependent immunity, forms medium-length dsRNA replication intermediates that are not recognized by MDA5. Kato et al. propose a model for PAMP recognition by MDA5 in which only long dsRNA viral genomes or stable long duplex viral RNAs formed during virus replication serve as MDA ligands. This model might explain why MDA5 ignores self-dsRNA, which is typically not present as long duplex RNAs.

How do RIG-I and MDA5 recognize a broad spectrum of PAMPs?

The current observations advance our understanding of how MDA5 discriminates between potential RNA ligands, but several questions about recognition of RNA by RIG-I and MDA5 still remain. It is widely accepted that ssRNA viruses generate dsRNA during their replication process (36, 37). However, only MDA5 recognizes EMCV (8 kb), whereas RIG-I recognizes other viruses with lengthy RNA genomes, such as VSV (11 kb), JEV (11 kb), and hepatitis C virus (9.6 kb). MDA5's failure to recognize these latter viruses may be due to their inability to form long or perhaps stable dsRNA. It is also possible that recognition by MDA5 depends on specific compartmentalization of the PAMP RNA with MDA5, as differences in the subcellular site of viral genome replication may influence the PAMP–MDA5 interaction.

The mechanism by which MDA5 discriminates between PAMP ligands in terms of their length is also unclear. Kato et al. demonstrate that MDA5 binds long, capped, di- or mono-5′ phosphate dsRNA, whereas RIG-I binds to short dsRNA or 5′ppp uncapped ssRNA. When RIG-I binds to 5′ppp ssRNA, it changes conformation, which disrupts the inhibitory interaction between the RIG-I repressor domain and the CARDs. This alteration results in the initiation of downstream signaling by the CARDs and exposes a 17- or 30-kD trypsin-resistant fragment corresponding to the RIG-I repressor domain, thereby marking the activation of RIG-I (10, 15, 16). However, poly I:C binding to RIG-I promotes a distinct conformational change that results in a 66-kD trypsin-resistant fragment, indicating that PAMP-bound RIG-I undergoes a distinct conformational change depending on the nature of its ligand. Structural studies validate that RIG-I prefers ssRNA ligands, whereas dsRNA binds only inefficiently to RIG-I, possibly due to constrains imposed by the location of basic residues within the RNA binding groove of its repressor domain. The charged residues are proposed to anchor 5′ppp ssRNA within the pocket, which would be less amenable to binding dsRNA ligands (15, 16). These observations suggest that RIG-I may have two ways to distinguish different RNA species: efficient recognition of 5′ppp ssRNA through its repressor domain (10, 15, 16) and comparably inefficient recognition and binding of dsRNA (10, 15). By extension, these conformational alterations of RIG-I might provide clues about how dsRNA ligands interact with MDA5 to stimulate its activation. Thus, MDA5 might become active upon binding long dsRNA through a ligand-induced conformation change that places its CARD into a signaling-active conformation. This might involve dsRNA interactions with its helicase domain and C-terminal region in a fashion similar to the binding of poly I:C to RIG-I.

Kato et al. and others have demonstrated that although very short dsRNA (20–30 bp) fail to trigger RIG-I–dependent signaling (15, 17), longer dsRNAs ranging from ∼70 kb to 2 kb can at least weakly engage RIG-I. These data suggest that the length of dsRNAs may dictate the interaction with the RIG-I helicase domain and/or repressor domain in a manner that supports a RIG-I–dsRNA complex. However, the mechanism of length discrimination of dsRNA PAMPs by these RLRs has not yet been revealed.

The third RLR family member, LGP2, has been defined as a regulator of RIG-I signaling based on its suppression of RIG-I function when overexpressed in cultured cells (10, 38, 39). However, recent studies imply that LGP2 may also function as either a positive or negative regulator of RLR signaling by forming a heterodimer with RIG-I or MDA5 when bound to RNA ligand (40, 41). Such interactions between the RLRs may also broaden their PAMP recognition profiles to accommodate other ligands, including ssRNA or dsRNA of varied length and composition, or even DNA–RNA duplexes. Structure and function analyses of RNA interactions with RLRs or heteromeric RLR complexes will further define the molecular basis of self- versus nonself discrimination.

The RLR repressor domain determines ligand specificity

The RLRs are adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding proteins that hydrolyze ATP as a result of binding RNA ligand (15). However, the role of the ATPase activity in the function of RLRs is not fully understood. RLRs contain multiple domains, including two domains known as the Walker A motif and the Walker B (also known as the DExD/H-Box) motif, each located within the helicase domain (42). Walker A and B motifs comprise an ATP binding region wherein specific amino acid residues contact the γ-phosphate of the nucleotide and mediate ATP hydrolysis upon substrate binding (43–45). Mutant RIG-I with an inactive Walker A motif retains ssRNA binding function but fails to trigger downstream signaling (15, 46). Thus, ATP hydrolysis is not essential for PAMP binding but is required for downstream signaling.

Recent studies revealed that the RIG-I repressor domain, in addition to binding to the RIG-I CARDs, forms a complex with the helicase domain linker region that likely stabilizes RNA ligand binding (10, 15, 16). Moreover, it seems that motifs in the RLR helicase domain could also be involved in RNA substrate binding according to structure and function studies of other DExD/H-Box RNA helicases (42). Such studies indicate that the RNA binding sites and the Walker A and B motifs mediate specific interactions (47). These observations present a model in which a repressor domain–helicase domain internal complex forms an RNA binding pocket whose association with PAMP RNA may serve to initiate the ATPase activity of RIG-I, which then triggers a conformation change that allows innate immune signaling. The repressor–helicase domain interaction of RLRs may thus be the key determinant of PAMP discrimination by RIG-I and MDA5 (15, 17). It also seems that RIG-I ATPase activity is involved in the unwinding of dsRNA (15). The importance of this activity for innate immune function is unclear, but it might support RIG-I interaction with dsRNA ligands by catalyzing their conversion to ssRNAs.

Future perspectives

The breadth of PRRs expressed in different cells and tissues and their distinct intracellular distribution provide the means for PAMP detection and immune activation against a variety of microbial pathogens at the local site of infection or in the “microbial niche.” These include the membrane-associated cytosolic replication sites of RNA viruses, extracellular sites of microbe interaction, and endosomal sites of microbial trafficking and metabolism (Fig. 1). The recent identification of the DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) protein as a cytoplasmic sensor of microbial DNA (48) suggests the existence of other PRRs that detect cytosolic PAMP DNA. It is reasonable to speculate that, similar to TLRs and RLRs, the cytoplasmic DNA sensor molecules also exhibit ligand specificity to cover a variety of DNA PAMPs in association with their specific microbial niche, thus providing a further basis for self- versus nonself discrimination. Understanding the processes of PAMP ligand recognition within each microbial niche will provide a foundation for the design of appropriate vaccines, adjuvants, and immunotherapies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stacy M. Horner and David M. Owen for critical reading and discussions.

T.S., M.G., and the Gale laboratory are supported by funds from the State of Washington, National Institutes of Health (grants AI060389, AI40035, DA024563, and AI057568), and by the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund.

References

- 1.Akira, S., S. Uematsu, and O. Takeuchi. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 124:783–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Veer, M.J., M. Holko, M. Frevel, E. Walker, S. Der, J.M. Paranjape, R.H. Silverman, and B.R.G. Williams. 2001. Functional classification of interferon-stimulated genes identified using microarrays. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69:912–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stetson, D.B., and R. Medzhitov. 2006. Antiviral defense: interferons and beyond. J. Exp. Med. 203:1837–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theofilopoulos, A.N., R. Baccala, B. Beutler, and D.H. Kono. 2005. Type I interferons (alpha/beta) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:307–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrack, P., J. Kappler, and T. Mitchell. 1999. Type I interferons keep activated T cells alive. J. Exp. Med. 189:521–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tough, D.F., P. Borrow, and J. Sprent. 1996. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science. 272:1947–1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogasawara, K., S. Hida, Y.M. Weng, A. Saiura, K. Sato, H. Takayanagi, S. Sakaguchi, T. Yokochi, T. Kodama, M. Naitoh, et al. 2002. Requirement of the IFN-alpha/beta-induced CXCR3 chemokine signalling for CD8(+) T cell activation. Genes Cells. 7:309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Bon, A., N. Etchart, C. Rossmann, M. Ashton, S. Hou, D. Gewert, P. Borrow, and D.F. Tough. 2003. Cross-priming of CD8(+) T cells stimulated by virus-induced type I interferon. Nat. Immunol. 4:1009–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braun, D., I. Caramalho, and J. Demengeot. 2002. IFN-alpha/beta enhances BCR-dependent B cell responses. Int. Immunol. 14:411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito, T., R. Hirai, Y.M. Loo, D. Owen, C.L. Johnson, S.C. Sinha, S. Akira, T. Fujita, and M. Gale. 2007. Regulation of innate antiviral defenses through a shared repressor domain in RIG-I and LGP2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:582–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato, H., O. Takeuchi, S. Sato, M. Yoneyama, M. Yamamoto, K. Matsui, S. Uematsu, A. Jung, T. Kawai, K.J. Ishii, et al. 2006. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 441:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loo, Y.M., J. Fornek, N. Crochet, G. Bajwa, O. Perwitasari, L. Martinez-Sobrido, S. Akira, A. Garcia-Sastre, M.G. Katze, and M. Gale Jr. 2008. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J. Virol. 82:335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hornung, V., J. Ellegast, S. Kim, K. Brzozka, A. Jung, H. Kato, H. Poeck, S. Akira, K.K. Conzelmann, M. Schlee, et al. 2006. 5 ′-triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 314:994–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pichlmair, A., O. Schulz, C.P. Tan, T.I. Naslund, P. Liljestrom, F. Weber, and C.R.E. Sousa. 2006. RIG-I-mediated antiviral responses to single-stranded RNA bearing 5 ′-phosphates. Science. 314:997–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahasi, K., M. Yoneyama, T. Nishihori, R. Hirai, H. Kumeta, R. Narita, J. Gale, F. Inagaki, and T. Fujita. 2008. Nonself RNA-sensing mechanism of RIG-I helicase and activation of antiviral immune responses. Mol. Cell. 29:428–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui, S., K. Eisenacher, A. Kirchhofer, K. Brzozka, A. Lammens, K. Lammens, T. Fujita, K.K. Conzelmann, A. Krug, and K.P. Hopfner. 2008. The C-terminal regulatory domain is the RNA 5′-triphosphate sensor of RIG-I. Mol. Cell. 29:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato, H., O. Takeuchi, E. Satho, R. Hirai, T. Kawai, K. Matsushita, A. Hiiragi, T.S. Dermody, T. Fujita, and S. Akira. 2008. The length-dependent recognition of double-stranded RNAs by RIG-I and MDA5. J. Exp. Med. 205:1601–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Jung, A., H. Kato, Y. Kumagai, H. Kumar, T. Kawai, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2008. Lymphocytoid choriomeningitis virus activates plasmacytoid dendritic cells and induces a cytotoxic T-cell response via MyD88. J. Virol. 82:196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyama, S., K.J. Ishii, H. Kumar, T. Tanimoto, C. Coban, S. Uematsu, T. Kawai, and S. Akira. 2007. Differential role of TLR- and RLR-signaling in the immune responses to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. J. Immunol. 179:4711–4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gitlin, L., W. Barchet, S. Gilfillan, M. Cella, B. Beutler, R.A. Flavell, M.S. Diamond, and M. Colonna. 2006. Essential role of mda-5 in type IIFN responses to polyriboinosinic: polyribocytidylic acid and encephalomyocarditis picornavirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:8459–8464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar, H., T. Kawai, H. Kato, S. Sato, K. Takahashi, C. Coban, M. Yamamoto, S. Uematsu, K.J. Ishii, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2006. Essential role of IPS-1 in innate immune responses against RNA viruses. J. Exp. Med. 203:1795–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakash, A., E. Smith, C.K. Lee, and D.E. Levy. 2005. Tissue-specific positive feedback requirements for production of type I interferon following virus infection. J. Biol. Chem. 280:18651–18657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen, J., S. VanScoy, T.F. Cheng, D. Gomez, and N.C. Reich. 2008. IRF-3-dependent and augmented target genes during viral infection. Genes Immun. 9:168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiscott, J. 2007. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 282:15325–15329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diebold, S.S., C. Massacrier, S. Akira, C. Paturel, Y. Morel, and C.R.E. Sousa. 2006. Nucleic acid agonists for toll-like receptor 7 are defined by the presence of uridine ribonucleotides. Eur. J. Immunol. 36:3256–3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gantier, M.P., S. Tong, M.A. Behlke, D. Xu, S. Phipps, P.S. Foster, and B.R.G. Williams. 2008. TLR7 is involved in sequence-specific sensing of single-stranded RNAs in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 180:2117–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klinman, D.M. 2004. Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutz, M., J. Metzger, T. Gellert, P. Luppa, G.B. Lipford, H. Wagner, and S. Bauer. 2004. Toll-like receptor 9 binds single-stranded CpG-DNA in a sequence- and pH-dependent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:2541–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas, T., J. Metzger, F. Schmitz, A. Heit, T. Muller, E. Latz, and H. Wagner. 2008. The DNA sugar backbone 2′ deoxyribose determines toll-like receptor 9 activation. Immunity. 28:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kindrachuk, J., J.E. Potter, R. Brownlie, A.D. Ficzycz, P.J. Griebel, N. Mookherjee, G.K. Mutwiri, L.A. Babiuk, and S. Napper. 2007. Nucleic acids exert a sequence-independent cooperative effect on sequence-dependent activation of Toll-like receptor 9. J. Biol. Chem. 282:13944–13953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito, T., D.M. Owen, F. Jiang, J. Marcotrigiano, and M. Gale Jr. 2008. Innate immunity induced by composition-dependent RIG-I recognition of hepatitis C virus RNA. Nature. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Marques, J.T., T. Devosse, D. Wang, M. Zamanian-Daryoush, P. Serbinowski, R. Hartmann, T. Fujita, M.A. Behlke, and B.R.G. Williams. 2006. A structural basis for discriminating between self and nonself double-stranded RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 24:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, D.H., M. Longo, Y. Han, P. Lundberg, E. Cantin, and J.J. Rossi. 2004. Interferon induction by siRNAs and ssRNAs synthesized by phage polymerase. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:321–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kohler, A., and E. Hurt. 2007. Exporting RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:761–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fredericksen, B.L., B.C. Keller, J. Fornek, M.G. Katze, and M. Gale. 2008. Establishment and maintenance of the innate antiviral response to west nile virus involves both RIG-I and MDA5 signaling through IPS-1. J. Virol. 82:609–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber, F., V. Wagner, S.B. Rasmussen, R. Hartmann, and S.R. Paludan. 2006. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J. Virol. 80:5059–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Targett-Adams, P., S. Boulant, and J. McLauchlan. 2008. Visualization of double-stranded RNA in cells supporting hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 82:2182–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoneyama, M., M. Kikuchi, K. Matsumoto, T. Imaizumi, M. Miyagishi, K. Taira, E. Foy, Y.M. Loo, M. Gale, S. Akira, et al. 2005. Shared and unique functions of the DExD/H-box helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in antiviral innate immunity. J. Immunol. 175:2851–2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komuro, A., and C.M. Horvath. 2006. RNA- and virus-independent inhibition of antiviral signaling by RNA helicase LGP2. J. Virol. 80:12332–12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkataraman, T., M. Valdes, R. Elsby, S. Kakuta, G. Caceres, S. Saijo, Y. Iwakura, and G.N. Barber. 2007. Loss of DExD/H box RNA helicase LGP2 manifests disparate antiviral responses. J. Immunol. 178:6444–6455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murali, A., X. Li, C.T. Ranjith-Kumar, K. Bhardwaj, A. Holzenburg, P. Li, and C.C. Kao. 2008. Structure and function of LGP2, a DExD/H helicase that regulates the innate immunity response. J. Biol.Chem. 283:15825–15833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanner, N.K., and P. Linder. 2001. DExD/H box RNA helicases: from generic motors to specific dissociation functions. Mol. Cell. 8:251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Story, R.M., I.T. Weber, and T.A. Steitz. 1992. The structure of the E. coli recA protein monomer and polymer. Nature. 355:318–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bell, C.E. 2005. Structure and mechanism of Escherichia coli RecA ATPase. Mol. Microbiol. 58:358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiese, C., J.M. Hinz, R.S. Tebbs, P.B. Nham, S.S. Urbin, D.W. Collins, L.H. Thompson, and D. Schild. 2006. Disparate requirements for the Walker A and B ATPase motifs of human RAD51D in homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:2833–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoneyama, M., M. Kikuchi, T. Natsukawa, N. Shinobu, T. Imaizumi, M. Miyagishi, K. Taira, S. Akira, and T. Fujita. 2004. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caruthers, J.M., and D.B. Mckay. 2002. Helicase structure and mechanism. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12:123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takaoka, A., Z. Wang, M.K. Choi, H. Yanai, H. Negishi, T. Ban, Y. Lu, M. Miyagishi, T. Kodama, K. Honda, et al. 2007. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 448:501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]