Abstract

Eleven mutations have been identified in 23S rRNA that make Haloarcula marismortui resistant to anisomycin, an antibiotic that competes with the amino acid side chains of aminoacyl tRNAs for binding to the A-site cleft of the large ribosomal unit. The correlation observed between the sensitivity of H. marismortui to anisomycin and the affinity of its large ribosomal subunits for the drug indicates that its response to anisomycin is determined primarily by binding of the drug to its large ribosomal subunit. The structures of large ribosomal subunits containing resistance mutations show that these mutations can be divided into two classes: (1) those that interfere with specific drug-ribosome interactions, and (2) those that stabilize the apo- conformation of the A-site cleft of the ribosome relative to its drug-bound conformation. The conformational effects of some mutations of the second kind propagate through the ribosome for considerable distances, and are reversed when A-site substrates bind to the ribosome.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, large ribosomal subunit, 23S rRNA mutation, X-ray crystal structure, Haloarcula marismortui, anisomycin

Introduction

Many antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis bind to the A-site cleft of the large ribosomal subunit. The A-site cleft is the wedge-shaped gap found between the splayed out bases of A2451 and C2452 in the peptidyl transferase centers of the 23S rRNAs of all large ribosomal subunits. (E. coli base numbering will be used here.) When aminoacyl tRNAs bind to the A site, their amino acid side chains occupy the A-site cleft 1–3. It is also a major part of the binding sites of three low-molecular weight antibiotics, anisomycin 4, chloramphenicol 5, and linezolid (US Patent # 6,947,845 B2, see also 6; 7), and a lesser part of the binding sites of several larger antibiotics: sparsomycin, virginiamycin M, tiamulin and clindamycin 4; 5; 8–10. All of these drugs should inhibit protein synthesis at least in part by competing with aminoacyl tRNAs for the A-site cleft. (For review see 11.)

Many mutations have been identified in 23S rRNA that confer resistance to A-site cleft antibiotics like anisomycin (see Table 2), and all of them affect bases found in or close to the A-site cleft, as expected. The surprise is that even though these mutations all alter the structure and/or the properties of an important component of the peptidyl transferase center of the ribosome, the A-site cleft, cells that carry them are viable. To better understand why this is so, we have investigated the structural consequences of several mutations in 23S rRNA that make Haloarcula marismortui resistant to anisomycin.

Table 2.

A-site Cleft Drug Resistance Mutations in Representative Species

| Base | Anisomycin contact? | Anisomycin resistance1 | Anisomycin resistance2 | Linezolid resistance3 | Chloramphenicol resistance4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2030A(2071) | 16.4 | - | - | - | G |

| G2032(2073) | 11.1 | - | - | A,C,U | - |

| G2061(2102) | + | - | - | - | A |

| A2062(2103) | 6.3 | - | - | C | G,C |

| G2447(2482) | + | A, C | C | U | A |

| A2451(2486) | + | - | - | - | - |

| C2452(2487) | ++ | U | U | U | U,A |

| A2453(2488) | + | U, G, C | C | G, C | G |

| C2499(2534) | 7.4 | U | - | U | - |

| U2500(2535) | + | A, C | - | C | C |

| A2503(2538) | + | - | - | - | G |

| U2504(2539) | + | - | - | C | A,G, C |

| G2505(2540) | 4.4 | - | - | - | A |

| G2576(2611) | 7.1 | U | - | - | - |

| G2581(2616) | 12.8 | A | - | - | - |

Bases where mutations are reported are designated using the convention described in Table 1.

This paper

Data obtained in H. halobium 12

In the “Anisomycin contact” column, “+” indicates a small area of contact between the bound drug and the nucleotide, and “++” indicates large contact area. For those nucleotides that do not contact ribosome-bound anisomysin, an approximate distance is given (in Å) for the separation between the atoms in anisomycin and the nucleotide that come closest together. In the “resistance” columns, “−“ indicates that a mutation that causes drug resistance has not been reported at that position. When mutations to resistance have been reported at some position, the relevant base changes are indicated.

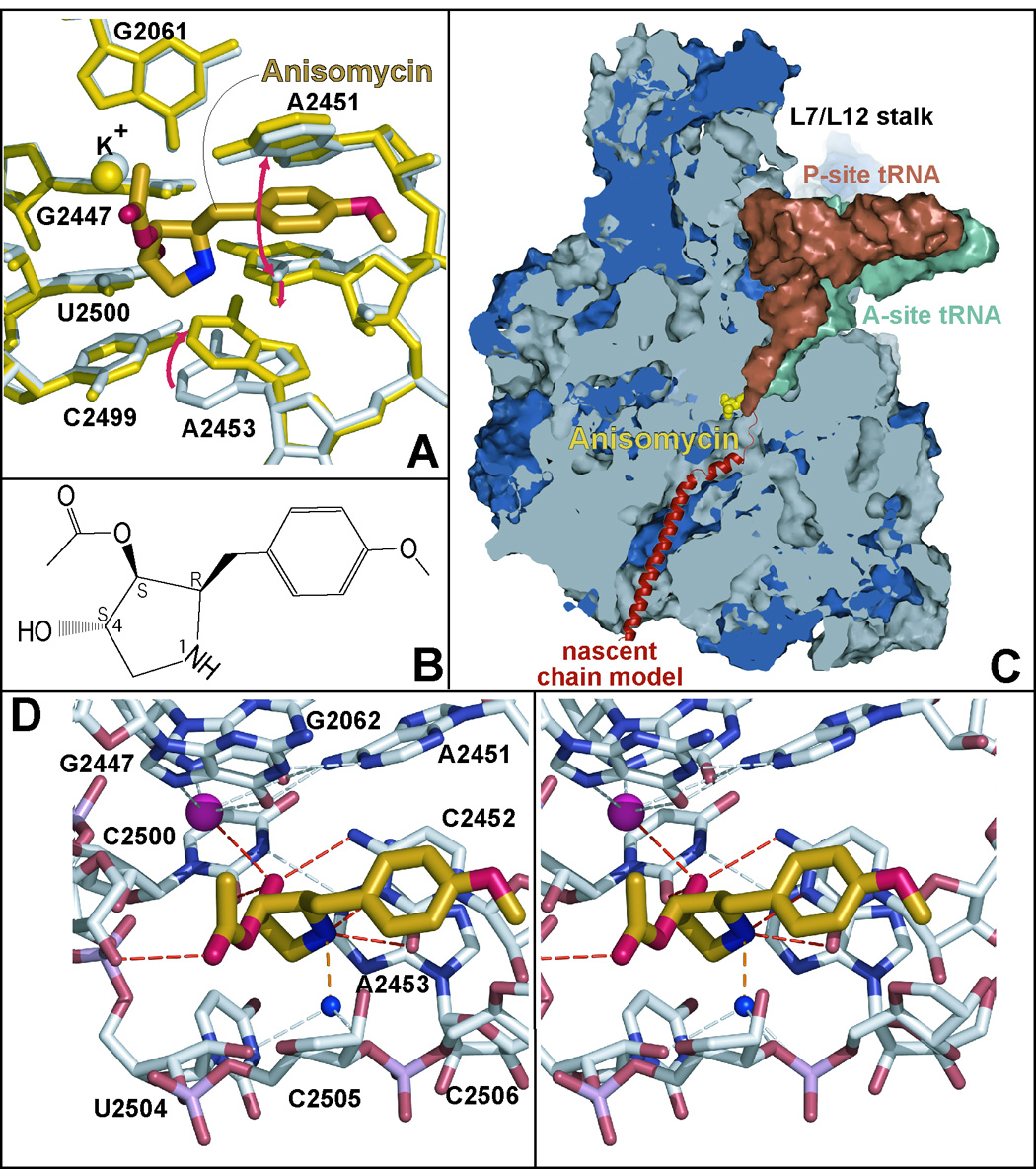

In H. marismortui, the only organism for which a crystal structure of anisomycin bound to the large ribosomal subunit exists, anisomycin binding is associated with a small conformational change that opens the aperture of the A-site cleft (Figures 1A, 1C) 4. The gap opens because A2451 moves away from C2452 in a direction that is roughly normal to the plane of the base of C2452, and the base of C2452 rotates away from its own phosphate group towards the lumen of the peptide exit tunnel. The opening of the A-site cleft is accompanied by a reorientation of A2453 that improves its stacking on C2452 and enables the N1 of A2453 to form a hydrogen bond with the N3 of U2500. Anisomycin binding destabilizes the apo-, or “closed” conformation of the A-site cleft by displacing a water molecule that is hydrogen bonded to both the N3 of C2452 and the O2 of U2500 when the A-site cleft is closed.

Figure 1.

The location in the polypeptide exit tunnel of the large subunit where anisomycin binds to the ribosome and its interactions with its binding site. Figure 1A shows anisomycin (heavy gold structure with its elements in different colors) bound to the ribosome. The conformation of the nucleotides in its binding site when the drug is bound is shown in yellow. Their conformation in the absence of the drug is shown in gray. The most conspicuous base motions associated with drug binding are indicated by red arrows. Bases are numbered so that they correspond with the base numbering of the 23S rRNA of E. coli. In this case, as in all others shown here, structures are superimposed by aligning them on the positions of 50 phosphorus atoms in the peptidyl transferase center. Figure 1B presents the chemical structure of anisomycin. Figure 1C is a cut-away view of the large ribosomal subunit – rRNA’s in gray and the ribosomal proteins in blue – showing the A-site (green) and P-site (dull red) bound tRNAs, and a schematic representation of a nascent polypeptide in the peptide exit tunnel (red). The position occupied by anisomycin (gold) when bound to the ribosome is also shown. Figure 1D is a stereo pair showing the way anisomycin (gold) interacts with its binding site. The dashed lines indicate a potential hydrogen bond (orange), hydrogen bonds to anisomycin (red), and some hydrogen bonds detected within the large ribosomal subunit structure (gray).

Aromatic stacking interactions and hydrogen bonding account for most of anisomycin’s affinity and specificity for the A-site of the ribosome 4. The aromatic p-methoxyphenyl group of anisomycin inserts into the enlarged A-site cleft where it stacks on C2452 (Figures 1B, 1D and supplemental material Figure 1). The drug is positioned by hydrogen bonds between its OH4 and both the N4 of C2452 and the O2 of U2500, its N1 and both the O2 of C2452 and N3 of C2452, and its carbonyl group and the 2’ OH of A2503. In addition, anisomycin’s OH4 hydroxyl group coordinates the potassium ion that is bound to the base triple formed by G2061, G2447, and A2451 1, and its N1 may interact with a water molecule that is held in place by hydrogen bonds to the O2’ of U2504, the O1P of U2506, and the O3’ of G2505.

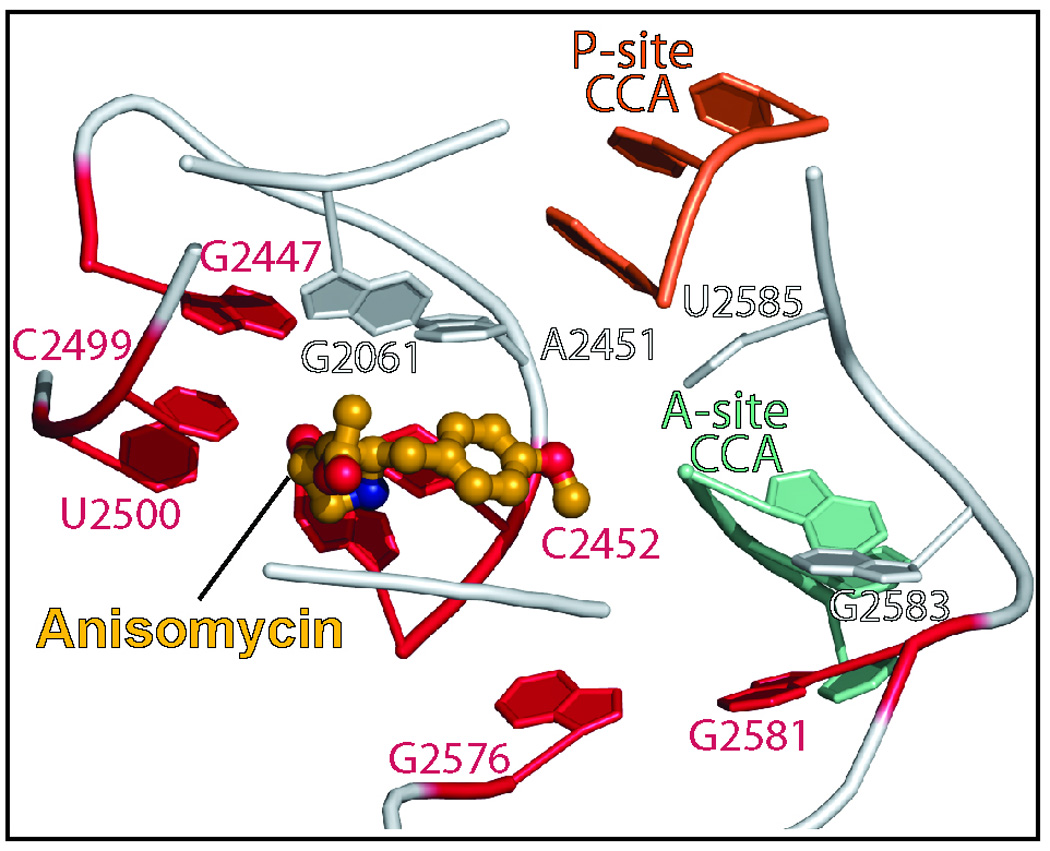

Here we present insights into the basis of anisomycin resistance obtained from the crystal structures of large ribosomal subunits from H. marismortui containing 11 different anisomycin-resistance mutations that alter 7 different nucleotides in 23S rRNA. These mutations include the H. marismortui equivalents of all the anisomycin-resistance mutations identified earlier in Halobacterium halobium 12. Three of the nucleotides altered by these mutations do not contact the drug when it is bound to the ribosome (Figure 2), and half the mutations obtained appear to act by stabilizing the closed, apo- conformation of the A-site cleft relative to its open, drug-bound conformation. The remaining pair of mutants directly alter the structure and/or the properties of the apo- form of the A-site cleft.

Figure 2.

A global view of the positions of the bases the mutation of which cause anisomycin-resistance in H. marismortui. The drug (gold with spherical atoms) is shown surrounded by the bases, the mutation of which lead to drug resistance (red). The backbone connecting bases is indicated in gray. The positions occupied by the CCA end of P-site bound tRNA (orange) and A-site bound tRNA (green) are shown for orientation. E. coli numbering is used for all bases.

Results

Crystalline ribosomes bind anisomycin with an affinity that correlates with drug toxicity

In vitro anisomycin inhibits the protein synthetic activity of ribosomes from both eukaryota and archaea by interacting with their large ribosomal subunits 11; 12. Even though the large ribosomal subunits from H. marismortui are active in peptide bond formation in the crystals described here 3, their affinity for anisomycin need not be the same as the anisomycin affinity of H. marismortui 70S ribosomes in vivo. This issue was addressed by comparing the anisomycin affinity of large ribosomal subunits from H. marismortui in crystals to the drug sensitivity of both the activity of H. marismortui ribosomes in protein synthesis in vitro, and the growth of the intact organism.

The dissociation constant of the crystalline wild type large ribosomal subunit for anisomycin was estimated as described previously 8. Data were collected from large subunit crystals that had been soaked with solutions containing 1 mM, 0.1 mM or 0.01 mM anisomycin (data not shown). Electron density maps computed using the differences in the amplitudes between anisomycin-soaked and apo- data sets as well as the experimental phases available for the apo- structure 13, i.e. (Fwild type + drug − Fwild type) difference maps, showed positive electron density for anisomycin in the expected location when the drug concentration in crystals was 1 mM or 0.1 mM, but no such density when the drug concentration was 0.01 mM. In addition, negative electron density was seen in the anisomycin region of electron density maps computed from amplitude differences between the 0.1 mM and 1 mM data sets with experimental phases of the apo structure, i.e. (Fwild type + 0.1mM aniso − Fwild type + 1mM aniso) difference maps, which indicates that at 1 mM anisomycin there is more drug bound than at 0.1 mM anisomycin. Thus in the crystalline state the dissociation constant (Kd) for the complex anisomycin forms with wild type large ribosomal subunits is of the order of 0.1 mM, which is in the range previously reported for H. marismortui ribosomes in solution 14.

The sensitivity of the protein synthetic activity of ribosomes from wild type strains of H. marismortui to anisomycin was measured using a poly U-directed, phenylalanine incorporation assay (see Materials and Methods). For ribosomes from both the wild type strain of H. marismortui (ATCC 43049), which has three ribosomal RNA cistrons, and DT38, the single rRNA cistron strain of H. marismortui used to obtain the mutations described below 15, the concentration of anisomycin that reduced protein synthesis activity by 50% (IC50) was about 0.13 mM. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of anisomycin for the growth of H. marismortui DT38 cells was found to be ~ 5 µg/ml (~20 µM; Table 1)(see Materials and Methods). The correspondence between the affinity of anisomycin for the large ribosomal subunit from H. marismortui, its IC50 for the inhibition of in vitro protein synthesis systems derived from that organism, and its MIC for the growth of H. marismortui suggests: (1) that anisomycin binds to large ribosomal subunits from H. marismortui with about the same affinity in the crystalline state as it binds to 70S ribosomes from that organism both in vivo and in vitro, and (2) that anisomycin’s capacity to inhibit the growth of H. marismortui is determined by its affinity for the large ribosomal subunit of this organism.

Table 1.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and crystallographically measured drug-ribosome dissociation constants of different H. marismortui strains for anisomycin.

| Strain | MIC (µM) | Kd by X-ray (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| WT (DT38) | 20 | 10–100 |

| G2447(2482)A | 80 | >100 |

| G2447(2482)C | 100 | >100 |

| C2452(2487)U | >1000 | >1000 |

| A2453(2488)U | 100 | >1000 |

| A2453(2488)C | 40 | 10–100 (but > WT) |

| C2499(2534)U | - | >100 |

| U2500(2535)A | >1000 | >100 |

| U2500(2535)C | 40 | 10–100 (but > WT) |

| G2576(2611)U | 100 | >100 |

| G2581(2616)A | 40 | >100 |

MICs and Kd’s were measured for the strains in question and ribosomes derived from them as described in Materials and Methods. Mutant strains are identified by the base in 23S rRNA that is altered as follows: (wild type base, base number in E. coli (base number in H. marismortui) mutant base). MICs are rounded off to one significant figure in recognition of the substantial trial-to-trial variation in the results of such measurements. “-“ implies that an MIC was not measured for the strain in question. Like wild type large subunits, large subunits from strains carrying the mutations A2453(2488)C and U2500(2535)C bind anisomycin appreciably when the anisomycin concentration is 100 µM, but difference electron density maps showed that the occupancy of the drug is lower than wild type, and hence that the Kd of these drug-large subunit complexes must be higher than that of the wild type complex.

Selection of anisomycin-resistance mutations in 23S rRNA

All but one of the anisomycin-resistant mutations described here were spontaneous mutations isolated by plating a strain of H. marismortui that contains a single rRNA cistron (DT38) 15 on media that included enough anisomycin or sparsomycin to inhibit growth (see Materials and Methods). Hundreds of strains containing mutated 23S rRNA genes were isolated, but the number of different 23S rRNA mutations that emerged was small. The selections done on media containing anisomycin yielded only 8 different 23S mutations: G2447C, C2452U, A2453(U, C, G), U2500A, G2576U and G2581A. Two other mutations that confer anisomycin resistance emerged from screens for sparsomycin-resistance: C2499U and U2500C. The last of the mutations examined here, G2447A, was generated by site-directed mutagenesis (see Materials and Methods).

The mutant strains obtained differ significantly in their resistance to the drug (Table 1). Minimal inhibition concentrations were obtained for most of the mutant strains by plating freshly grown cells onto agar plates with increasing concentration of anisomycin. The MICs of these strains correlate well with the anisomycin affinity of their large ribosomal subunits in the crystalline state.

Two resistance mutations interfere directly with anisomycin-ribosome interactions

Almost two thirds of the anisomycin-resistant strains isolated in this study carry a single mutation, C2452U. (Recently this same mutation has been reported to confer anisomycin resistance on Saccharomyces cerevisiae 16 The base of C2452 interacts directly with the bound drug (Figure 1D). Only one other mutation was obtained in a nucleotide that interacts directly with the bound drug, U2500A, and it was isolated only once. Both strains are highly resistant to anisomycin. Their MICs exceed 1 mM (Table 1).

Comparison of the C2452U structure with the wild type, apo- large subunit structure reveals that this mutation is associated with only small conformational adjustments in the A-site cleft region (data not shown). The aperture of the A-site pocket increases somewhat because a water molecule that forms hydrogen bonds with the N3 of C2452 and the O2 of U2500 in the apo- structure disappears as a consequence of the loss of one of its hydrogen bonding partners. The release of this water molecule allows U2452 to improve its stacking on A2453 by moving closer to U2500, and the pairing between A2453 and C2499 appears to be strengthened, as indicated by a diminished separation between the two bases.

Large ribosomal subunits carrying the C2452U mutation do not bind anisomycin appreciably in crystals even when the drug concentration is 1 mM (data not shown). The low affinity of these ribosomes for the drug and the corresponding increase in MIC are consistent with the inability of anisomycin to form one of the hydrogen bonds that stabilizes its binding to the wild type ribosome. The C2452U mutation replaces the N4 of C2452, a hydrogen bond donor, with an O4, a hydrogen bond acceptor, and consequently one of the two hydrogen bonds that the OH4 of anisomycin forms in the wild type complex is lost (Figure 1D).

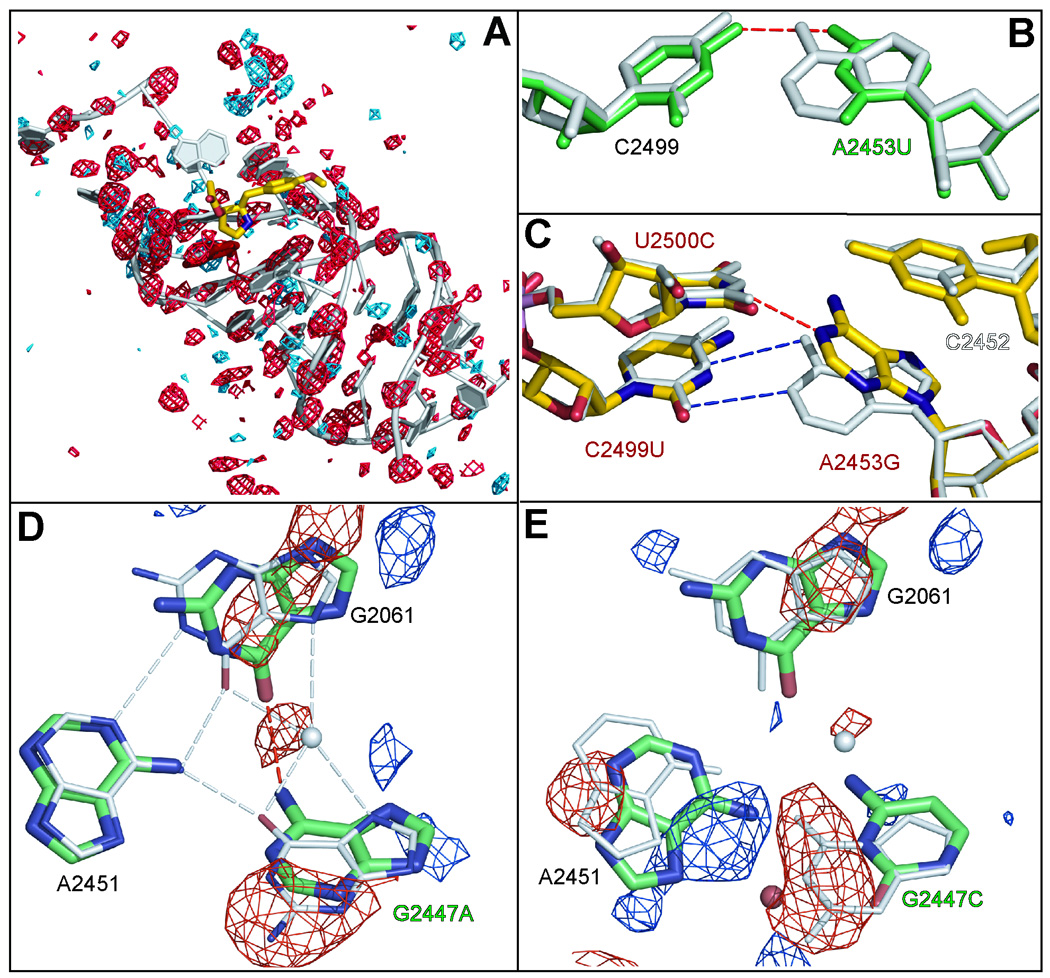

The U2500A mutation is much more disruptive structurally than U2452C; the B-factors of nucleotides in the region rise markedly (Figure 3A). The crystal structure of its large ribosomal subunit reveals not only that an adenosine at position 2500 is incompatible with the formation of one of the two hydrogen bonds to the OH4 of anisomycin that stabilizes the wild type ribosome complex with the drug, but also that its purine ring invades space normally filled by C2452. This insertion pushes C2452 towards its own phosphate group, decreasing the aperture of the A-site cleft.

Figure 3.

The effects of mutations on the structure of the A-site cleft region. Figure 3A shows the difference electron density observed when wild type apo- data are subtracted from data obtained from crystals containing U2500A ribosomes. The contouring is at + 4 sigma (blue) and − 4 sigma (red). The correlation of red features with backbone phosphate groups is indicative of a general disordering of the structure in the neighborhood of the mutation. Figure 3B displays the effect of mutating A2453 (gray structure) to a U (green structure). Figure 3C overlays the wild type apo- structure (gray) with the wild type drug-bound structure (yellow) in the region of A2453, which is immediately below the A-site cleft. The mutations obtained in this region are indicated with red labels. Figure 3D shows how the mutation G2447A disturbs the structure of the (G2061, G2447, A2451) base triple. The mutant structure is in green and the wild type structure is in gray. The (FG2447A − Fwild type) electron difference map is contoured at a level of 6 sigma. The negative electron difference density is displayed in red and the positive density is in blue. Figure 3E is the corresponding figure for the mutation G2447C with the (FG2447C − Fwild type) electron difference density contoured at 4 sigma.

Mutations that stabilize the closed conformation of the A-site cleft confer drug resistance

Six of the 11 mutations identified in this study involve either A2453, the base that swings up under C2452 when anisomycin binds to the wild type ribosome, U2500, the base with which A2453 pairs when it is in the bound, open conformation, or C2499 the base with which A2453 pairs with when the A-site cleft is in the closed, apo- conformation (Figure 3C). With the exception of the mutation U2500A, the drug resistance of which is discussed above, the structural and phenotypic effects of all of these mutations are consistent with the hypothesis that the conformational change A2453 undergoes when anisomycin binds to the wild type ribosome significantly stabilizes the drug-ribosome complex.

When the ribosome is in the closed, apo- conformation, C2499 forms an unusual base pair with A2453, the geometry of which resembles a Watson-Crick AU, suggesting that one of the two bases is protonated or in a rare tautomeric form (Figure 3C). A U at position 2499 ought to pair more stably with A2453 than a C, which in turn should reduce the tendency of A2453 to adopt its induced, open conformation and hence reduce the affinity of the ribosome for the drug. As expected, strains carrying the C2499U mutation are anisomycin-resistant.

Not surprisingly, the structure of large subunits carrying of the C2499U strain is all but indistinguishable from that of the wild type (data not shown). However, there are hints in the mutant structure that the interaction between A2453 and a U at position 2499 is stronger than the interaction between A2453 and C2499 in the wild type ribosome. The distance between the O4 of U2499 and the N6 of A2453 in the mutant structure is slightly shorter than the corresponding distance between the N4 of C2499 and the N6 of A2453 in the wild type structure (2.74 Å vs. 3.07 Å) and similarly the N3 pyrimidine -N1 purine distance in the mutant is 2.82 Å rather than the 3.20 Å it is in wild type. No electron density for anisomycin is seen when the drug is introduced into crystals of these large ribosomal subunits at 0.1 mM, which indicates a significant increase in Kd.

Replacement of the A at position 2453 by a G should also stabilize the closed conformation of the A-site cleft by strengthening the 2453-2499 base pair. (This mutation could also interfere with the interaction between the base at position 2453 and U2500 that stabilizes the drug bound, open conformation.) A strain bearing this mutation emerged from our screens, but we never obtained large ribosomal subunit crystals from this strain that were of sufficient quality to enable us to determine its structural consequences. Cultures of this strain grown on a large scale tended to revert to wild type or to mutate to A2453(C or U).

Mutations that destabilize the open conformation of the A-site cause drug resistance

As in the case of the C2499U mutation, the structure of large subunits carrying the U2500C mutation is virtually indistinguishable from that of the wild type in the absence of anisomycin. The U2500C mutation should not disrupt the hydrogen bond observed between the O2 of the wild type U2500 and the OH4 of ribosome-bound anisomycin. However, if these mutant ribosomes were to adopt the open conformation induced by anisomycin binding, a C at position 2500 would be unable to form a base pair with A2453 the way the U at position 2500 does in the wild type ribosome, and this should destabilize the drug bound, open conformation relative to the apo, closed conformation (Figure 3C).

Interestingly, the effect of the U2500C mutation on anisomycin binding is small as is its effect on the MIC (Table 1). Although, anisomycin binding to the large subunit of U2500C can be detected in crystals soaked with 0.1 mM anisomycin, the mutation reduces the affinity of anisomycin as indicated in the negative electron density in the anisomycin region of difference maps computed from (FU2500C + 0.1mM aniso - Fwild type + 0.1mM aniso) amplitudes and experimental phases for the apo wild type structure (data not shown). The MIC for U2500C strains (~ 40 µM (Table 1)) is only twice that of wild type.

Screens for anisomycin resistance also yielded strains carrying the mutations A2453C and A2453U, both of which should affect the structure of the A-site cleft region and its conformational equilibrium similarly. Neither a cytosine nor a uracil at position 2453 should stack on C2452 as effectively as the adenosine they replace, and both should be too far to base pair with either C2499 or U2500, no matter which conformation the A-site cleft region adopts. However, the A2453U mutation has a much more dramatic effect on anisomycin binding and anisomycin MIC than does the A2453C mutation.

The only crystallographic data obtained for large ribosomal subunits containing the mutation A2453C came from crystals that included 0.1 mM anisomycin, and the electron density maps computed from those data include density for the drug. Consistent with this observation the A-site cleft is in the open conformation. However, the electron density for anisomycin is weaker in the maps of mutant subunits soaked with 0.1 mM anisomycin than in the corresponding electron density obtained from wild type ribosomes soaked with the drug at the same concentration. This indicates a modest reduction in the affinity of anisomycin for A2453C large ribosomal subunits compared to wild type subunits, which correlates with a two-fold increase in MICcompared to the wild type.

The difference electron density maps (FA2453U − Fwild type) of large ribosomal subunit crystals carrying the mutation A2453U confirm the replacement of the purine normally found at 2453 by a pyrimidine. In addition the U at 2453 is orientated the same way as A2453 in the apo- conformation of the wild type structure, which means that the A-site cleft is closed. The dissociation constant of the complex ribosomes carrying this mutation form with anisomycin is greater than 1 mM crystallographically; no electron density for anisomycin was detected at that drug concentration. The interaction of these same ribosomes with anisomycin was also examined using the poly U-dependent phenylalanine incorporation assay mentioned earlier. For anisomycin, their IC50 proved to be greater than 1.3 mM, the highest drug concentration tested. Thus this mutation results in an increase in the Kd of ribosome-anisomycin complexes of 10-fold, or greater, and consistent with this observation, the MIC for this strain is 5–10 times higher than that of wild type (Table 1).

The remarkable difference in the anisomycin affinity between ribosomes carrying the mutations A2453U and A2453C may be explained by the single hydrogen bond that forms between the O4 of the U at 2453 and the N4 of C2499, which stabilizes the closed, apo- conformation of the A-site. In addition A2453U causes a modest displacement of the base of C2452 towards its own phosphorus atom, which narrows the aperture of the A-site cleft.

Mutations that alter the position of the K+-that interacts with anisomycin cause drug resistance

As noted earlier, anisomycin interacts with the K+ that is coordinated by the O6 and N7 of both G2061 and G2447, which form a base triple with A2451 1. This base triple rests on top of a second base triple formed by C2063, C2501 and A2450. G2447 is sandwiched between U2500 and C2501, G2061 is wedged between A2062 and C2063, and A2451 is stacked on C2452.

G2447A is the only mutation in the G2061, G2447, A2451 base triple that is viable in E. coli 17. Since this mutation makes E. coli resistant to chloramphenicol, another antibiotic that binds in the A-site cleft 18, it seemed likely that it might also affect the response of H. marismortui to anisomycin, and plausible that other mutations in that base triple might alter anisomycin sensitivity. As expected, the mutation G2447A, which was introduced into H. marismortui by site-directed mutagenesis, confers a low level of anisomycin resistance (Table 1). Consistent with the MIC data, no drug binding to large ribosomal subunits containing this mutation is detected in crystals where the drug concentration is 0.1 mM.

Replacement of G2447 with an A has three structural effects on the base triple, evidence for all of which can be seen in (FG2447A − Fwild type) difference electron density maps (Figure 3D). These maps contain three negative features, one at the position occupied by the N2 of G2447 in the wild type structure, a second at the position normally occupied by a K+, and a third in the region of G2061. The first peak shows that the base at position 2447 in the mutant structure is an A, not a G, as expected. The second peak shows that the K+ that is associated with the wild type base triple has been displaced. The third feature is indicative of a disordering of the position of G2061. (The B factor for G2061 in the mutant structure is about 90 Å2, but its B-factor in the wild type structure is about 55 Å2.) Since in the wild type ribosome the K+ that is displaced in G2447A ribosomes interacts with both G2061 and anisomycin its displacement probably explains both the disordering of G2061 seen in G2447A ribosomes and their reduced affinity for anisomycin.

Unexpectedly a strain bearing the mutation G2447C was isolated in screens for anisomycin resistant strains of H. marismortui. Given the properties of G2447A mutations, it is not surprising to find that G2447C also confers anisomycin-resistance. However, this mutation has a more dramatic effect on ribosome structure than G2447A mutations, as is evident in (FG2447C − Fwild type) difference electron density maps (Figure 3E). There is a conspicuous negative feature that verifies the replacement of the purine at 2447 by a pyrimidine, a negative feature overlying G2061, and negative peak at the position of the K+. G2061 is about as disordered by this mutation as it is by the G2447A mutation; the B factors for G2061 are about the same in the two mutant structures. Furthermore, it again appears that the reason G2061 is disordered and the affinity for anisomycin is reduced is the loss/displacement of the critical K+ ion. The most significant difference between the two mutant structures lies in their effects on the position of A2451, a nucleotide that appears to be involved in activation the α-amine group of the amino acylated tRNA in the A-site before peptidyl transfer reaction 19. A2451 clearly moves away from the peptidyl transferase center when the G at 2447 is changed to a C, but does not move when that same G is changed to an A. (Compare Figures 3D and 3E.)

Some resistance mutations reduce the size of the A-site cleft

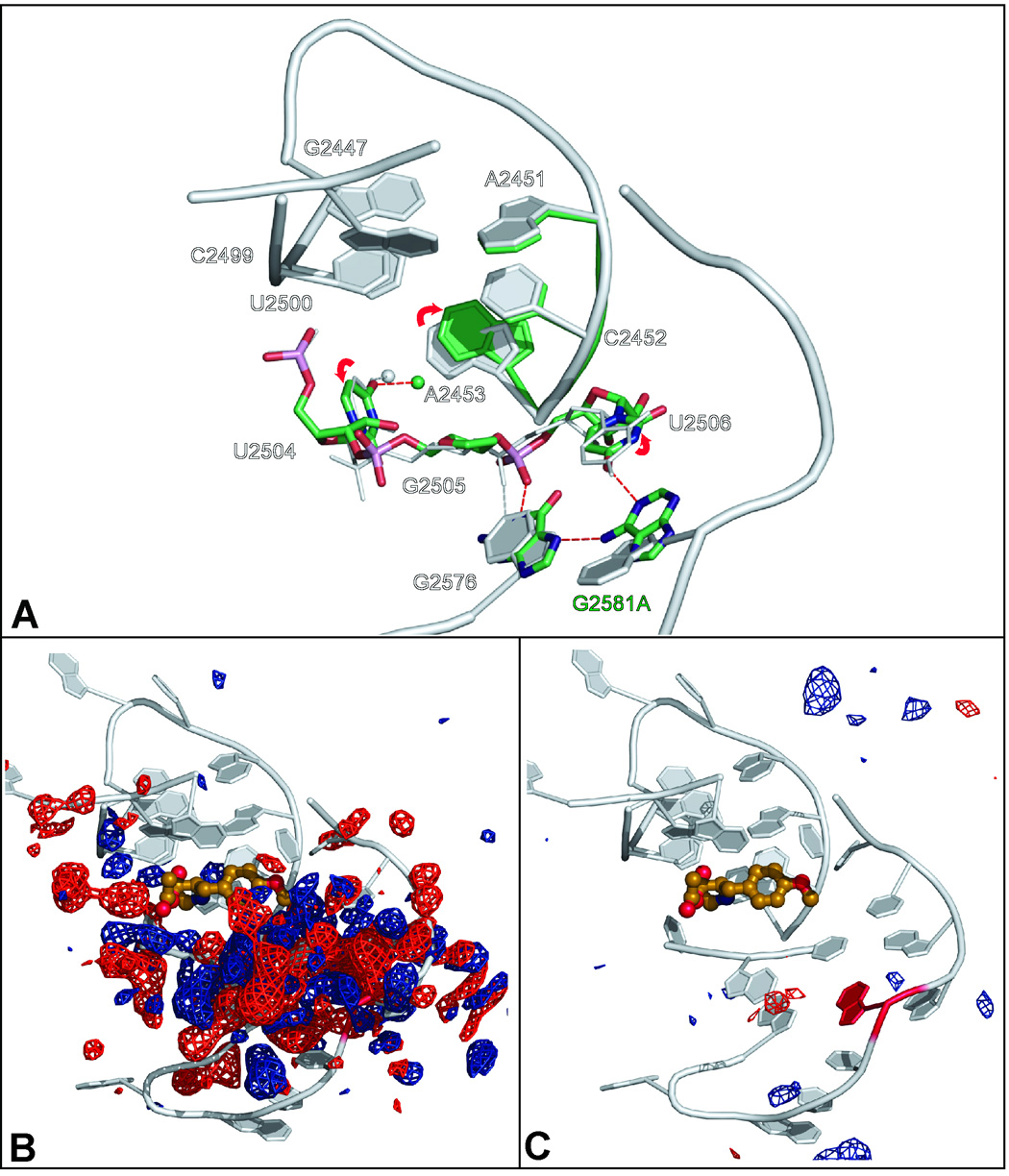

Two of anisomycin-resistant mutations obtained (G2581A and G2576U) alter nucleotides that are remarkably far from the site where the drug binds to the ribosome. The distances of closest approach between atoms in these two nucleotides and atoms in anisomycin are 12.8 Å and 7.1 Å, respectively, and both produce a similar set of conformational changes that propagate through the ribosome from the site of mutation to the A-site cleft.

In the wild type ribosome G2581 is in the syn configuration, but when G2581 is mutated to A, the A adopts the anti configuration (Figure 4A). Difference electron density maps computed using data from wild type crystals as the reference reveal massive shifts in the positions of surrounding nucleotides that extend from the site of mutation to the A-site cleft (Figure 4B). As Figure 4A shows, this syn-anti change results in U2506 moving away from and G2576 moving towards the (mutated) A2581. As a result, a new hydrogen bond forms between the N7 of G2576 and N6 of the (mutated) A2581, and a shift in the position of the backbone of bases 2504-2507 takes place that removes U2504 from the anisomycin binding site. In the wild type large ribosomal subunit, U2504 forms part of the wall that constrains the position of the non-aromatic end of ribosome-bound anisomycin. Mediated by a water molecule that is hydrogen bonded to the O4 of U2504, the displacement of U2504 from the anisomycin binding pocket is correlated with movement of A2453 towards C2452 and retraction of C2452 from the anisomycin binding pocket, which narrows the aperture of the A-site cleft. These changes account for the electron density differences shown in Figure 4B, leaving no significant difference density in difference electron density maps computed using the amplitudes measured from G2581A crystals and the amplitudes computed from the rebuilt G2581A structure. (Compare Figure 4B with Figure 4C.)

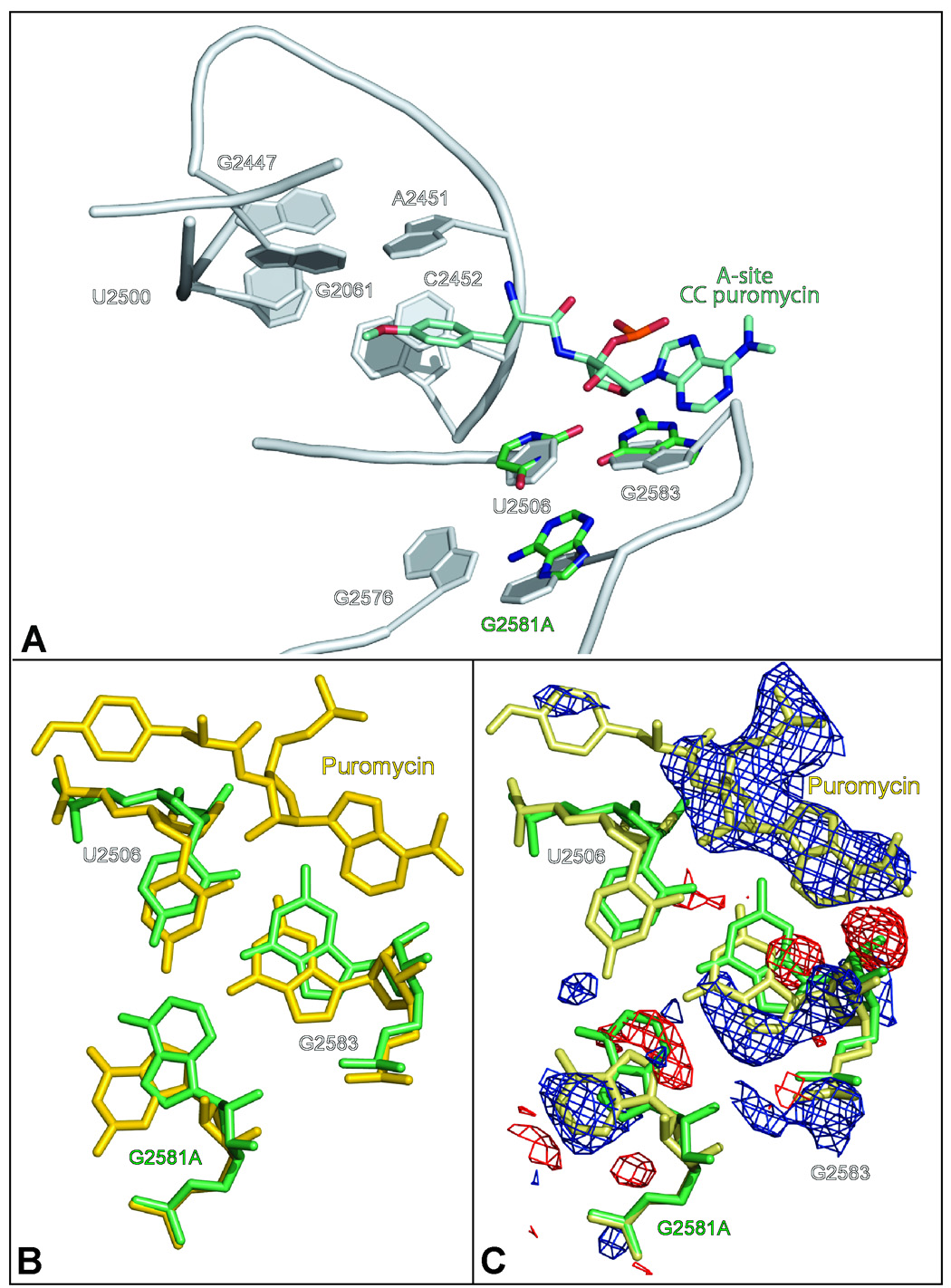

Figure 4.

The effects of the mutation G2581A on the structure of the large ribosomal subunit from H. marismortui. Figure 4A compares the structure of the G2581A mutant (green) with the wild type apo structure (gray). Hydrogen bonds characteristic of the mutant are indicated by red dashed lines while hydrogen bond characteristic of the wild type structure of shown as gray dashed lines. Figure 4B shows the (FG2581A − Fwild type) electron density difference map computed from the amplitudes observed in G2581A crystals and the amplitudes obtained from wild type crystals. Contours are drawn at +4 sigma (blue) and − 4 sigma (red). The underlying structure is shown in gray. Figure 4C corresponds to Figure 4B, but the difference electron density map (FG2581A − FG2581A calculated) difference electron map shown was obtained using the observed amplitudes obtained from G2581A crystals and calculated amplitudes obtained from the refined structure for the mutated ribosome. Differences are contoured at the same levels as in Figure 4B.

The effect of the G2576U mutation on the conformation of the A-site cleft region is similar to that of the mutation G2581A, but even larger (data not shown). The backbone of 2504-2507 is more bent. U2504 is further out of the anisomycin binding pocket. A2453 is closer to C2452, and C2452 is even more retracted from the anisomycin binding pocket. The loss of the hydrogen bond normally seen between the N1 of G2576 and the O2P phosphate of G2505 leaves the sugar phosphate backbone from 2506 to 2504 unhinged, and the B-factors for all the nucleotides in the anisomycin binding pocket rise 1.5 fold, indicative of increased disorder in the anisomycin pocket.

Binding of A-site substrate analogs to the ribosome reverses the conformational consequences of the mutation G2581A

The conformational change of the 2581 base from syn to anti not only narrows the A-site crevice but also disrupts a nearby wobble base pair between G2583 and U2506 by pushing both bases away from A2581. This puts the base of G2583 into the space that A75 of aminoacyl tRNAs occupy when bound to the ribosomal A site (Figures 5A, 5B). The occlusion of this site should interfere with protein synthesis, yet G2581A strains grow with about the same generation time as wild type. To gain insight into this apparent contradiction, crystals of large ribosomal subunits containing the G2581A mutation were exposed to an analog of an A-site tRNA substrate, CC-puromycin, at a concentration of 1 mM. Interestingly, the difference electron map calculated using the apo- G2581A structure as the reference indicated that the A at position 2581 adopts the wild type syn conformation when CC-puromycin is bound to the ribosome (Figure 5C), restoring the binding site for A-site substrates. However, a difference electron density map computed by differencing data from the same crystal and data from a wild type structure suggests that the A at position 2581 is in the anti configuration (data not shown). These findings indicate that approximately half of the large ribosomal subunits in the crystals studied have CC-puromycin bound and the purine at 2581 in the syn- configuration. In the remaining half, there is no CC-puromycin bound and the purine at 2581 is in the anti- configuration.

Figure 5.

The effect of A-site substrate binding on the conformation of large ribosomal subunits containing the mutation G2581A. Figure 5A compares the conformation of the 2581 region of wild type ribosomes (gray) with that of the G2581A mutant (green). Also included in the figure is CC-puromycin (bluegreen) as reference for the binding site of amino acylated tRNA to the A-site. Figure 5B compares the structure of G2581A mutant (green) and CC-puromycin bound to large ribosomal subunit of wild type (gold). Figure 5C compares the structures of G2581A mutant (green) with CC-puromycin bound to G2581A (khaki) with overlaid (FG2581A − FG2581A CC-puromycin) difference electron density, which was computed by using as amplitudes the differences observed between the data obtained from G2581A crystals that included the analog and data obtained from G2581A crystals that lack the analog. Positive features were contoured at +4 sigma (blue), and negative features at − 4 sigma (red).

Discussion

The structures presented above support two conclusions, one that is likely to be generally applicable, and the other one more specific to H. marismortui. The general conclusion is that the structures and properties of the ribosomal sites to which substrates and antibiotics bind can be modulated by sequences that are a nucleotide or two outside them. The effects of the mutations G2576U and G2581A on the structure of the large ribosomal subunit from H. marismortui and on its interaction with anisomycin illustrate this point. It follows that, in the absence of ligands at least, the structures of the active sites of ribosomes from different species are unlikely to be identical even though the sequences in those sites are highly conserved because of the existence of sequence variations in the surrounding. (The degree to which ligand binding reduces these species-dependent variations in the structures of active sites remains to be determined.)

The more specific conclusion concerns the conformational flexibility of the A-site cleft region in the large subunit of the H. marismortui ribosome. In all the structures of the large ribosomal subunit from this organism that have a ligand bound in the A-site cleft, the cleft is wider than it is in the apo- structure, i.e. it adopts an open conformation, and in some cases the aperture of the cleft is opened wider than it is when anisomycin is bound 4; 19. The positions of C2452 and A2453 vary in these open complexes. In some of them A2453 remains in its apo- position because C2452 has moved so far towards A2453 it sterically prevents A2453 from swinging towards U2500 as it does in the anisomycin complex (see pdb #1VQN 19).

It is likely that there are several conformational states available to the A-site cleft in the H. marismortui ribosome, and that they are in equilibrium with each other. In the absence of A-site cleft ligands, the closed conformation is favored, but when the concentration of anisomycin is high enough, the anisomycin variant of the open conformation dominates because it is the one to which the drug binds best. It is possible that the increases in the B-factors of nucleotides in the A-site cleft region associated with several of the anisomycin-resistance mutations described above are indicative of changes in relative conformational energies that disfavor the anisomycin-bound state. It remains to be seen whether the A-site cleft regions of the ribosomes from other species are as variable conformationally as the A-site cleft region in H. marismortui.

Given the observed variability of the position of A2453 in the different open conformations of the A-site cleft region in H. marismortui, the energetic importance of the conformation it adopts when anisomycin binds to the ribosome might be questioned. However, the observation that mutations in A2453, C2499 and U2500, which disfavor the anisomycin-bound conformation of A2453 result in the reduction of anisomycin binding argues that the relocation of A2453 observed when anisomycin binds is important for drug binding.

In all of the crystal structures of large ribosomal subunits from eubacteria the A-site cleft adopts a conformation close to that seen in H. marismortui when anisomycin is bound. In the structure of the apo- 70S ribosome from T. thermophilus 20 the A site cleft is occupied by the base of U2506, which stacks on C2452, an arrangement so far unique to that organism that could by itself explain why its A-site cleft is open. However, in both the apo- large ribosomal subunit structure from Deinoccocus radiodurans 21, and the apo- 70S ribosome structure from E. coli 22 the A-site cleft is empty. Thus the A-site cleft may always be open in eubacterial ribosomes.

It follows that if the conformation of the A-site cleft controlled drug specificity, eubacteria ought to be more sensitive to A-site cleft antibiotics than archaea because none of the free energy of drug binding should have to be expended to drive eubacterial ribosomes into the appropriate (open) conformational state. However, eubacteria are resistant to anisomycin, but sensitive to chloramphenicol and linezolid, while archaea, like eukaryotes, are more sensitive to anisomycin than they are to the other two 11; 14.

One of our aims at the outset of these studies was to find anisomycin-resistant mutations that would make H. marismortui more like E. coli both in sequence and in response to A-site cleft antibiotics. However, all the mutations reported above alter nucleotides that are the same in both organisms, and none of the anisomycin-resistant strains of H. marismortui tested are more sensitive to chloramphenicol than the parent strain (data not shown). In this context it is worth noting that while eukaryotes like Saccharomyces cerevisiae respond the same way to A-site cleft antibiotics as H. marismortui, two of the bases identified as important for anisomycin binding in this study differ between these two organisms 23. S. cerevisiae has U’s at positions 2453 and 2499 instead of the A and the C found at those positions in both E. coli and H. marismortui. This observation is puzzling because taken separately, both A2453U and C2499U confer anisomycin resistance on H. marismortui, but S. cerevisiae is sensitive to the drug. The sequence differences that cause the differences in response to A-site cleft to antibiotics that distinguish eukaryotes (and archaea) from eubacteria have yet to be identified experimentally.

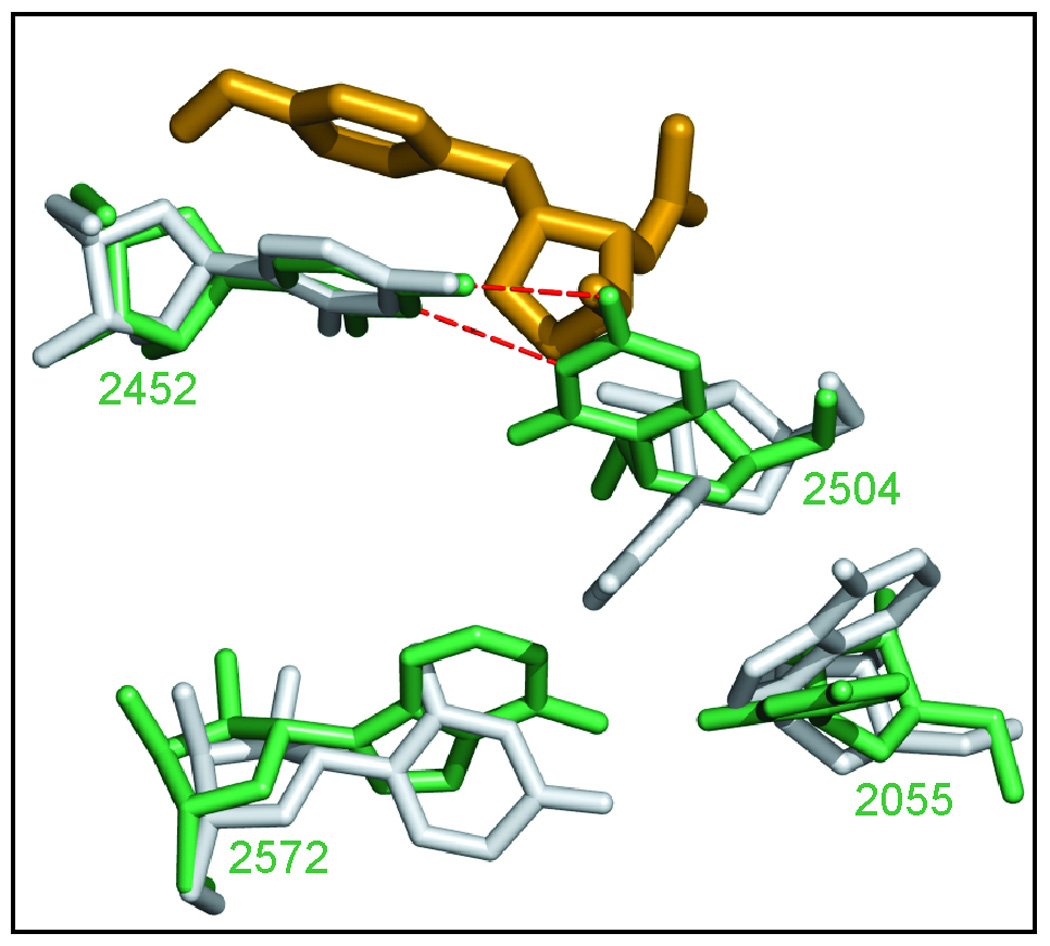

Comparisons of known large subunits structures suggest that the orientation of U2504 may be crucial for determining the response of ribosomes to A-site cleft antibiotics. In large ribosomal subunits from E. coli, T. thermophilus, and D. radiodurans U2504 is oriented so that it can form a base pair with C2452 (Figure 6). When this pair forms, not only does the hydrogen bond seen in H. marismortui large ribosomal subunit/anisomycin complexes between the OH4 of anisomycin and the N4 of C2452 become impossible, but U2504 occupies space anisomycin would fill if it were to bind to these prokaryotic ribosomes the same way it binds to H. marismortui ribosomes. In the H. marismortui large ribosomal subunit, U2504 is oriented at roughly right angles to the base of C2452, with which it does not pair.

Figure 6.

A hypothesis for the structural difference that controls the response of different species to A-site cleft antibiotics. The structure of the T. thermophilus large ribosomal subunit in the neighborhood of C2504 (green) 20 is compared to the structure of that same region in H. marismortui (gray) with anisomycin bound (gold).

The extensive overlap between the sets of 23S rRNA mutations that cause resistance to anisomycin in halophilic archaea and the mutations that cause linezolid and/or chloramphenicol resistance in archaea and eubacteria (Table 2) is powerful evidence that these antibiotics interact with the same part of the ribosome. However, when full account is taken of the details of how anisomycin interacts with the ribosome, the conformational differences that exist in the A-site cleft region between ribosomes from different species, and the differences in chemical structure that exist between A-site cleft antibiotics, the high degree of overlap becomes puzzling rather than enlightening. For example, the mutations G2447A, G2447C and C2452U all cause anisomycin resistance by eliminating specific interactions between the bound drug and the ribosome. How could those same mutations have the same effect on the interaction of the ribosome with chloramphenicol and linezolid, which are chemically different?

The structures published for chloramphenicol and linezolid bound to the ribosome, which ought to resolve conundrums of the sort just identified, are uninformative. The 3.5 Å resolution structure available for the complex chloramphenicol forms with the large ribosomal subunit from Deinococcus radiodurans 5 demonstrates unequivocally that chloramphenicol is an A-site cleft antibiotic, but it contains enough stereochemical infelicities to make one reluctant to attempt a detailed interpretation. A 3.0 Å resolution structure exists for the same antibiotic bound to the large ribosomal subunits from H. marismortui4, but in this structure the drug is not bound in the A-site cleft, which renders it irrelevant in the present context. (The significance of that second binding site is discussed elsewhere 4.) There is also a roughly 3.0 Å resolution structure for linezolid bound to the large ribosomal subunit of H. marismortui available in the patent literature (US Patent # 6,947,845 B2). The structure is not well-refined, and thus like the D. radiodurans chloramphenicol structure mentioned above, it does little more than prove that linezolid is an A-site cleft antibiotic.

The recent work of Schmeing and coworkers has shown not only that the amino acid side chains of A-site bound aminoacyl tRNAs occupy the A-site cleft, but also that the conformation of the A site varies during the elongation cycle 19. These observations suggest that anisomycin-resistant mutations in 23S rRNA, many of which affect the conformational properties of the A-site cleft, ought to have an impact on protein synthesis. While we have not carried out a systematic study of the growth characteristics of the mutant strains discussed above because of the difficulties experienced in obtaining reproducible generation time estimates, two of them clearly grow much more slowly than wild type: G2447A and A2453G.

One reason why anisomycin-resistant strains of H. marismortui might be more viable than anticipated is that aminoacyl tRNAs, the normal substrates for the A-site cleft, interact far more extensively with the ribosome than low molecular weight molecules like anisomycin. Thus a mutation that alters the relative stabilities of different conformations of the A-site cleft enough to raise an organism’s MIC for anisomycin may not alter the affinity of aminoacyl tRNAs for the ribosomal A site enough to disrupt protein synthesis. The capacity of CC-puromycin to trap G2581A ribosomes in a conformation compatible with protein synthesis illustrates this point. Here too an equilibrium exists between (at least) two conformational states, one in which the purine at 2581 is in the syn configuration and a second in which it is in the anti configuration. Because CC-puromycin (and, presumably, aminoacyl tRNA) can bind to the ribosome only when the A-site cleft region is in its 2581-syn conformation, it is the only conformation seen when those ligands are bound to the ribosome, even when the G at 2581 is replaced with an A, which favors the 2581-anti conformation. The structure of the mutant modeled with complete occupation of CC-puromycin and syn configuration of G2581A is nearly identical to the wild type structure.

Similar substrate-driven conformational effects have been reported in other contexts. In E. coli ribosomes mutations at position 2451 have a large, inhibitory effect on the peptidyl transferase activity of the ribosome when assayed using puromycin as the A-site substrate, but their effects are much smaller when assayed using intact aminoacyl tRNAs, which interacts far more extensively with the ribosome than puromycin 24.

One of the motivations for the study reported here was an interest in the effect mutations in the (2061, G2447, A2451) triple have on ribosome structure. Even though many base triples can be drawn on paper that are nearly isosteric with the one found at that position in the apolarge ribosomal subunit of H. marismortui, only a single mutation in this triple has ever been found in E. coli: G2447A 17. It has a slow-growth phenotype that is associated with modest effects on stop codon read through and -1 frameshifting 17; 18; 25. However, interestingly, when aminoacyl tRNA concentrations are limiting, the G2447A mutation causes a 14-fold reduction in peptidyl transferase activity. We now know that the structural consequences of this mutation are modest. The position of A2451, the nucleotide closest to the peptidyl transferase center, is unaffected, as is the A-site cleft. Unlike E. coli, H. marismortui tolerates a second mutation in the triple, G2447C, that does affect the A-site cleft directly. A2451 moves so far from the position seen in wild type ribosomes that the hydrogen bond it makes with substrates in the peptidyl transferase center should no longer form 19. Nevertheless, cells containing this mutation grow more or less normally. In crystals of large subunits containing this mutation C-puromycin does not bind at a concentration of 1mM, but CC-puromycin does, and preliminary analysis of this complex suggests that A2451 moves back towards its wild type position (data not shown).

Methods

Spontaneous mutations

Strains resistant to anisomycin were selected using H. marismortui strain DT38, which contains a single rrn operon (rrnA) that has a G2099(2058)A mutation [numbering of mutation: H. marsimortui (E. coli)] in its 23S rRNA gene 15. Cultures were grown either at 37°C in 23% MGM medium 26 or at 42°C in DT media 15. 23% MGM contains: 1 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L peptone, and 23% saltwater solution. 30% salt water stock solution contains: 240 g/L NaCl, 30 g/L MgCl2·6H2O, 35 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 7 g/L KCl, and 5 mM CaCl2. The pH of media was adjusted to 7.5 using 1 M Tris. DT media contains: 214 g/L of NaCl, 17 g/L of MgSO4·7H2O, 3 g/L of trisodium citrate·2 H2O, 1.7 g/L of KCl, 0.23 g/L of CaCl2·2H2O, 4.3 g/L of yeast extract (Difco), 8.5 g/L of bacteriological peptone (Oxoid), 3.4 g/L of glucose, and 5.2 g/L of Tris, pH was adjust with HCl to 7.2. After autoclaving and cooling, 1.7 ml/L sterile filtered trace elements (0.0218 g of MnCl2·4H2O and 0.486 g of FeCl3·6H2O per 100 ml) is added to media. Strains were plated on 23% MGM or DT media that included 15 g/L of agar. Cultures in logarithmic growth with an absorbance at 600 nm between 0.6–1.5 [measured on a Varian, Cary 1Bio UV-visible Spectrometer or on a Beckman, DU 640] were plated directly, or briefly centrifuged and resuspended in a tenth the original volume, before plating on 23% MGM plates or on DT plates in top agar. Mutant strains were selected on plates that contained either 10 or 20 mg/L (36.7 – 75.4 uM) of anisomycin (Sigma) or 10 mg/L sparsomycin (Sigma). After 1 to 3 weeks first colonies appeared, which were allowed to grow up to two months before PCR sequencing, and further culturing. The occurrence of a spontaneous anisomycin resistant mutant was 1 to out of 109 cells. All of the anisomycin resistant strains isolated in this study carry a single mutation in domain V of 23S rRNA, as determined by PCR sequencing of domain V. Inspection of difference electron density maps of entire large ribosomal subunits revealed no mutational changes outside of domain V.

Mutant strains were maintained in 23% MGM or DT media in the absence of antibiotics. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for the different mutants were determined by plating logarithmic phase cultures onto MGM or DT media plates containing 1–300 mg/L anisomycin. The slow growth phenotype (5–8 hours) and the inconsistency in the determined generation time of H. marismortui wild type prevented us from determining absolute growth rate for any of the anisomycin resistant mutants.

Site-directed mutagenesis

For site-directed mutagenesis in H. marismortui the plasmid LR11 plasmid was created using the Invitrogen Gateway system: LR11 includes an origin of replication for E. coli, a mevanolin resistance gene, an ampicillin resistance gene and an H. marismortui rrnA operon with a G2482(2447)A mutation [numbering: H. marsimortui (E. coli)] in the 23S rRNA gene; a mutation that confirms anisomycin resistance. LR11 was transformed into DT38, a single rrnA operon with G2099(2058)A mutation in the 23S sequence according to Dyall-Smith 26. The homologous recombination was forced by plating onto anisomycin containing plates. After a month several colonies appear with no mevanolin resistant gene, but carrying G2482(2447)A and G2099(2058)A mutation in their 23S rRNA sequence.

Preparation of 50S subunits

To accumulate sufficient quantities of mutant ribosomes, multiple 2 L cultures of DT media were grown at 42°C for each mutant. The purity of the cultures was monitored by PCR-sequencing at different stages of the growth. Large ribosomal subunits were prepared from only from cultures containing cells that all had the same 23S rRNA sequence. Subunits were crystallized and stabilized as previously described for wild type 13; 19; 27. Crystals were soaked with antibiotic or substrate in buffer B (12 % PEG 6000, 20% ethylene glycol, 1.7 M NaCl, 0.5 M NH4Cl, 1 mM CdCl2, 100 mM K CH3COO, 6.5 mM CH3COOH pH 6.0, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and with either 30 mM MgCl2 or 21 mM MgCl2 and 30 mM SrCl2 or no MgCl2 and 100 mM SrCl2) for several hours with one exchange of soaking solution at 4°C. The antibiotic concentrations used were 0.01 mM, 0.1 mM, or 1 mM anisomycin; or 1 mM in the case of C-puromycin, and CC-puromycin.

In vitro translation assay

The capacity of ribosomes isolated from different strains of H. marismortui to carry out mRNA-directed protein synthesis was measured using the poly U-directed phenylalanine incorporation assay described previously 3. In the version of that assay used here 70S ribosomes were employed instead of separated 50S and 30S ribosomal subunits.

Crystallography

Data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory) on beam line X29 and at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory) on beam line 24-ID-C as previously described 13. After data processing with HKL2000, difference maps were calculated with CNS to located bound anitbiotics. A ligand-free large ribosomal subunit with protein sequences adjusted according to the H. marismortui genome 28 served as a starting model for refinement (3CC2.pdb). The refinement in CNS 29 included rigid body refinement, minimization, and B-factor refinement. Structures were visualized in the program O 30, and figures were generated using the program PyMol 31.

The data obtained from wild type subunit crystals soaked with 1 mM anisomycin in this study are superior to those associated with the anisomycin-ribosome structure reported earlier (1K73; 4) both in resolution (~3.0 Å vs. 2.77 Å) and in completeness (90.9 % vs. 99.9 %). For that reason the 1 mM anisomycin structure determined in this study was used as the reference, drug-bound structure in this paper.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Crystallographic statistics of data collection

| Crystal | Anisomycin soak | Res(Å) | I/sigma | R merge | Complete | Redundancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1 mM | 50.0-277 (2.84-2.77) | 12.43 (2.09) | 10.6 (86) | 99.9 (99.8) | 6.8 |

| C2487U | 100 uM | 50.0-3.00(3.12-3.00) | 10.0(2.18) | 11.0(58.1) | 78.3(69.5) | 3.19 |

| T2535A | 100 uM | 50.0-2.85(2.96-2.85) | 11.00(1.74) | 10.7(74.7) | 88.1(90.0) | 1.76 |

| C2534T | 100 uM | 50.0-3.42(3.55-3.42) | 10.76(1.63) | 18.0(96.5) | 99.2(99.5) | 6.60 |

| T2535C | 100 uM | 50.0-3.00(3.12-3.00) | 13.12(2.67) | 13.4(72.2) | 99.9(100) | 6.30 |

| G2611U | - | 50.0-2.55 (2.64-2.55) | 14.25 (1.96) | 8.3 (76) | 98.9 (97.2) | 6.05 |

| A2488U | - | 50.0-2.97 (3.05-2.97) | 11.34 (1.58) | 16.8 (100) | 99.5(98.8) | 6.90 |

| A2488C | 100 uM | 50.0-3.11(3.21-3.11) | 8.7(1.82) | 13.8(61) | 85.5(85.0) | 2.64 |

| G2482A | 100 uM | 50.0-2.95(3.06-2.95) | 12.4(1.56) | 9.1(71.1) | 97.7(96.9) | 5.52 |

| G2482C | 100 uM | 50.0-2.80(2.90-2.80) | 14.86(1.42) | 12.9(96.0) | 99.9(99.4) | 6.85 |

| G2616A | 100 uM | 50.0-2.90(3.00-2.90) | 11.03(1.65) | 14.4(95.8) | 98.3(83.0) | 6.50 |

| G2616A | 1 mM (CCP) | 50.0-2.85(2.96-2.85) | 14.08(1.95) | 9.4(75.0) | 99.1(100) | 4.83 |

all data were collected at wavelength ranging from 1.07 to 1.1 Å

Table 4.

Statistics of model refinement

| Crystal | Anisomycin soak | Res(Å) | R cryst | Rfree | bond | angle | Pdb deposit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1 mM | 50.0-2.70 | 20.1 | 24.4 | 0.007 | 1.1 | 3CC4 |

| C2487U | 100 uM | 30-2.70 | 18.3 | 22.6 | 0.007 | 1.0 | 3CC7 |

| T2535A | 100 uM | 50.0-2.75 | 18.2 | 23.2 | 0.007 | 1.0 | 3CCE |

| C2534T | 100 uM | 50-3.3 | 20.8 | 28.7 | 0.008 | 1.1 | 3CCJ |

| T2535C | 100 uM | 50.0-2.90 | 17.4 | 22.2 | 0.007 | 1.0 | 3CCL |

| G2611U | - | 30.0-2.55 | 20.0 | 24.2 | 0.007 | 1.0 | 3CCM |

| A2488U | - | 50-2.90 | 18.7 | 23.2 | 0.007 | 1.0 | 3CCQ |

| A2488C | 100 uM | 50-3.0 | 18.5 | 24.7 | 0.005 | 1.0 | 3CCR |

| G2482A | 100 uM | 50.0-2.95 | 18.3 | 24.0 | 0.007 | 1.1 | 3CCS |

| G2482C | 100 uM | 50.0-2.80 | 17.9 | 22.2 | 0.007 | 1.1 | 3CCU |

| G2616A | 100 uM | 50.0-2.90 | 17.8 | 22.6 | 0.007 | 1.1 | 3CCV |

| G2616A | 1 mM (CCP) | 50.0-2.75 | 19.2 | 24.0 | 0.007 | 1.1 | 3CD6 |

Acknowledgements

We thank Laryssa Vasylenko for her technical assistance, Jimin Wang for helpful discussions during structure refinement, Nigel Grindley, Cathy Joyce, Michael L. Dyall-Smith, and Kate Porter for helpful advice on cloning and transformation of H. marismortui, the staff of the CSB core facility for computational support. We are also indebted to Yorgo Modis and the staff of beam line X29 (National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory) and beam line 24-ID-C (Advanced Light Source, Argonne National Laboratory) for their support with data collection. This work was supported by grants from the NIH: PO1 GM022778 (to P.B.M. and T.A.S.), and F32-GM067354 (to S.J.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession numbers. Coordinates and structure factors relevant to this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers: 3CC2 (starting model for refinement), 3CC4 (wild type ribosomal subunit with bound anisomycin), 3CC7, 3CCE, 3CCJ, 3CCL, 3CCM, 3CCQ, 3CCR, 3CCS, 3CCU, 3CCV, and 3CD6 (anisomycin resistant large ribosomal subunits). (See table 4 for description of mutant structures.)

References

- 1.Nissen P, Hansen J, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA. The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis. Science. 2000;289:920–930. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen JL, Schmeing TM, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Structural insights into peptide bond formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11670–11675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172404099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmeing TM, Seila AC, Hansen JL, Freeborn B, Soukup JK, Scaringe SA, Strobel SA, Moore PB, Steitz TA. A pre-translocational intermediate in protein synthesis observed in crystals of enzymatically active 50S subunits. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:225–230. doi: 10.1038/nsb758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen JL, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Structures of five antibiotics bound at the peptidyl transferase center of the large ribosomal subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlunzen F, Zarivach R, Harms J, Bashan A, Tocilj A, Albrecht R, Yonath A, Franceschi F. Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature. 2001;413:814–821. doi: 10.1038/35101544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leach KL, Swaney SM, Colca JR, McDonald WG, Blinn JR, Thomasco LM, Gadwood RC, Shinabarger D, Xiong LQ, Mankin AS. The site of action of oxazolidinone antibiotics in living bacteria and in human mitochondria. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:393–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin AH, Murray RW, Vidmar TJ, Marotti KR. The oxazolidinone eperezolid binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit and competes with binding of chloramphenicol and lincomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2127–2131. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu D, Blaha G, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Structures of MLSBK antibiotics bound to mutated large ribosomal subunits provide a structural explanation for resistance. Cell. 2005;121:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson DN, Harms JM, Nierhaus KH, Schlunzen F, Fucini P. Species-specific antibiotic-ribosome interactions: implications for drug development. Biol. Chem. 2005;386:1239–1252. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlunzen F, Pyetan E, Fucini P, Yonath A, Harms JM. Inhibition of peptide bond formation by pleuromutilins: the structure of the 50S ribosomal subunit from Deinococcus radiodurans in complex with tiamulin. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:1287–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gale EF, Cundliffe E, Reynolds PE, Richmond MH, Waring MJ. The Molecular Basis of Antibiotic Action. 2nd edit. London: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. Antibiotic inhibitors of ribosomal function; pp. 402–547. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hummel H, Bock A. 23S Ribosomal-RNA Mutations in Halobacteria Conferring Resistance to the Anti-80S Ribosome Targeted Antibiotic Anisomycin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2431–2443. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.6.2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ban N, Nissen P, Hansen J, Moore PB, Steitz TA. The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 Å resolution. Science. 2000;289:905–920. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz JL, Marin I, Urena D, Amils R. Functional-Analysis of seven Ribosomal Systems from Extremely Halophilic Archaea. Can. J. Microbiol. 1993;39:311–317. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu D, Blaha G, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Gene replacement in Haloarcula marismortui: construction of a strain with two of its three chromosomal rRNA operons deleted. Extremophiles. 2005;9:427–435. doi: 10.1007/s00792-005-0459-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakauskaite R, Dinman JD. rRNA mutants in the yeast peptidyltransferase center reveal allosteric information networks and mechanisms of drug resistance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sato NS, Hirabayashi N, Agmon I, Yonath A, Suzuki T. Comprehensive genetic selection revealed essential bases in the peptidyl-transferase center. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15386–15391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson J, Kim DF, O'Connor M, Lieberman KR, Bayfield MA, Gregory ST, Green R, Noller HF, Dahlberg AE. Analysis of mutations at residues A2451 and G2447 of 23S rRNA in the peptidyltransferase active site of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9002–9007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151257098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmeing TM, Huang KS, Strobel SA, Steitz TA. An induced-fit mechanism to promote peptide bond formation and exclude hydrolysis of peptidyl-tRNA. Nature. 2005;438:520–524. doi: 10.1038/nature04152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selmer M, Dunham CM, Murphy FV, Weixlbaumer A, Petry S, Kelley AC, Weir JR, Ramakrishnan V. Structure of the 70S ribosome complexed with mRNA and tRNA. Science. 2006;313:1935–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.1131127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson DN, Schluenzen F, Harms JM, Yoshida T, Ohkubo T, Albrecht R, Buerger J, Kobayashi Y, Fucini P. X-ray crystallography study on ribosome recycling: the mechanism of binding and action of RRF on the 50S ribosomal subunit. EMBO J. 2005;24:251–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berk V, Zhang W, Pai RD, Cate JHD. Structural basis for mRNA and tRNA positioning on the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15830–15834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607541103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannone JJ, Subramanian S, Schnare MN, Collett JR, D'Souza LM, Du YS, Feng B, Lin N, Madabusi LV, Muller KM, Pande N, Shang ZD, Yu N, Gutell RR. The Comparative RNA Web (CRW) Site: an online database of comparative sequence and structure information for ribosomal, intron, and other RNAs. BMC Bioinformatics. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Youngman EM, Brunelle JL, Kochaniak AB, Green R. The active site of the ribosome is composed of two layers of conserved nucleotides with distinct roles in peptide bond formation and peptide release. Cell. 2004;117:589–599. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregory ST, Carr JF, Rodriguez-Correa D, Dahlberg AE. Mutational analysis of 16S and 23S rRNA genes of Thermus thermophilus. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:4804–4812. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.4804-4812.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyall-Smith M. The Halohandbook, Protocols for Halobacterial genetics. 2004 ver. 4.9. ( http://www.haloarchea.com)

- 27.Ban N, Freeborn B, Nissen P, Penczek P, Grassucci RA, Sweet R, Frank J, Moore PB, Steitz TA. A 9 Å resolution x-ray crystallographic map of the large ribosomal subunit. Cell. 1998;93:1105–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baliga NS, Bonneau R, Facciotti MT, Pan M, Glusman G, Deutsch EW, Shannon P, Chiu YL, Gan RR, Hung PL, Date SV, Marcotte E, Hood L, Ng WV. Genome sequence of Haloarcula marismortui: A halophilic archaeon from the Dead Sea. Genome Res. 2004;14:2221–2234. doi: 10.1101/gr.2700304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved Methods for Building Protein Models in Electron-Density Maps and the Location of Errors in These Models. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLano WL. The PyMol molecular graphics system. San Carlos, CA, USA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloss P, Xiong LQ, Shinabarger DL, Mankin AS. Resistance mutations in 23 S rRNA identify the site of action of the protein synthesis inhibitor linezolid in the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:93–101. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiong LQ, Kloss P, Douthwaite S, Andersen NM, Swaney S, Shinabarger DL, Mankin AS. Oxazolidinone resistance mutations in 23S rRNA of Escherichia coli reveal the central region of domain V as the primary site of drug action. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5325–5331. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.19.5325-5331.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mankin AS, Garrett RA. Chloramphenicol Resistance Mutations in the Single 23s Ribosomal-Rna Gene of the Archaeon Halobacterium-Halobium. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3559–3563. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3559-3563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.