Abstract

Public health initiatives to distribute nicotine replacement therapy free of charge as a means of promoting smoking cessation are ongoing. Are there enough smokers interested in using nicotine replacement therapy to have a substantial impact on the prevalence of smoking if this aid were distributed free to all interested smokers? We conducted a telephone survey of 825 randomly selected daily smokers aged 18 years or older who had smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day at some point in their lives. Overall, 58.9% of the respondents said they would be interested in nicotine replacement therapy if it were offered for free. Of those interested, almost all (93.8%) said that they would use the nicotine replacement therapy to help them quit for good. There were differences in the levels of interest: smokers who intended to quit were more interested in using the nicotine replacement therapy than those who planned to reduce or maintain their smoking.

Nicotine replacement therapy significantly increases a smoker's chances of quitting.1 It is widely available in Canada and can be obtained over the counter, usually at a cost to the consumer. Several public health initiatives have explored the advantages of free distribution of nicotine replacement therapy as a means of promoting smoking cessation.2,3 Based on the popularity of these mass distribution efforts, it has been suggested that giving free nicotine replacement therapy to all interested smokers could have an important impact on the prevalence of smoking.2

This statement assumes that a substantial proportion of smokers would actually be interested in receiving free nicotine replacement therapy and would use it in an attempt to quit. Previous studies4,5 have reported a high level of interest among smokers; however, their results may reflect a response bias rather than a true intention to use nicotine replacement therapy. Health care professionals need to know how receptive smokers are to using nicotine replacement therapy. We sought to evaluate smokers' attitudes by asking novel questions about their interest in receiving free nicotine replacement therapy and what they would do if they received it.

Methods

The study, conducted across Canada, enrolled daily smokers aged 18 years or older who had smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day at some point in their lives (a level judged to define an established smoker).6 Of 15 958 households contacted by random digit dialing, we estimated that 1372 contained at least one adult daily smoker. We interviewed 889 people (a response rate of 64.8%) and found that 825 had smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day, meeting our inclusion criteria for analysis. Sample sizes are reported as unweighted values. Results of statistical tests, means and proportions are reported based on weighted data. We obtained ethics approval for this study from the ethics review committee of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

We asked the participants if they would be interested in nicotine replacement therapy if it was offered free of charge. To further explore smokers' level of interest, we asked the interested respondents for what purpose they would use nicotine replacement therapy (e.g., to quit for good, to stop temporarily or for help in places where smoking is not permitted), for how long they would be willing to use it to stay off cigarettes and how soon they would use it if it was sent to their homes.

Results

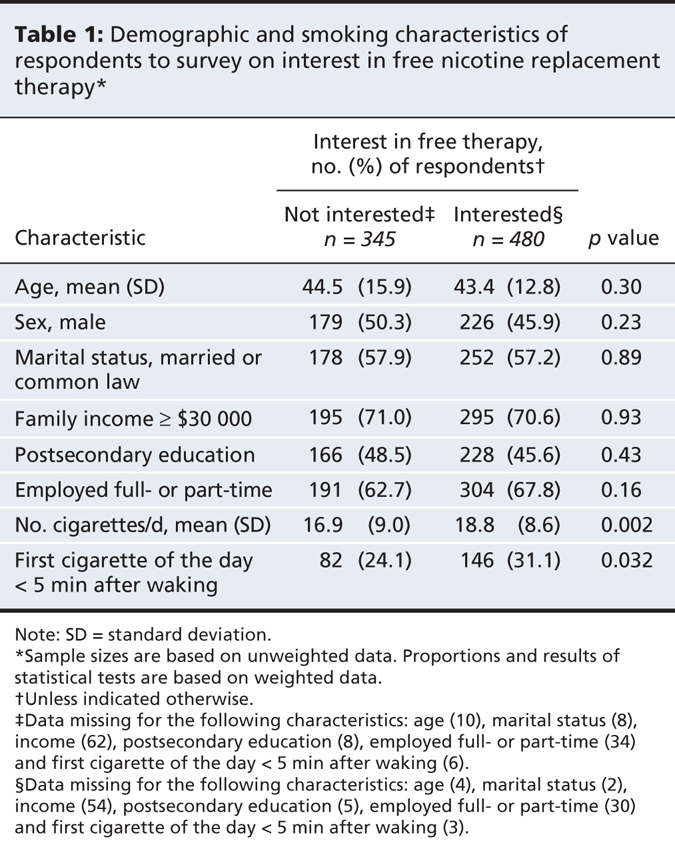

Demographic and smoking characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1. More than half (58.9%, weighted [480/825]) said they would be interested in nicotine replacement therapy if it were offered for free. Interest was not significantly related to demographic characteristics, but those interested in nicotine replacement therapy smoked more heavily than those not interested. Almost all of those interested (93.8%, weighted [447/480]) said that they would use the nicotine replacement therapy to help them quit for good. Of those who would use it to quit, most (80.6%, weighted [358/447]) said they would use it as long as needed to stay off cigarettes. Furthermore, of those interested and intending to use nicotine replacement therapy to quit, 61.1% (weighted [275/447]) said they would use it within a week if it was sent to their homes, implying a concrete commitment to receiving it. Finally, we found that prior use of nicotine replacement therapy was predictive of future interest: smokers who had used it in the past were more interested in receiving free nicotine replacement therapy than were those who had never used it (74.5% v. 44.6%; p < 0.001). In addition, smokers who said they intended to quit smoking were more likely to say they would be interested in nicotine replacement therapy (67.3%) than those intending to reduce (57.8%) or to maintain their smoking (42.4%) (p < 0.001).

Table 1

Interpretation

Our findings suggest that a substantial population of smokers would be willing to participate in public health initiatives to reduce the prevalence of smoking through the distribution of free nicotine replacement therapy. Furthermore, our results provide new information regarding what recipients would do with nicotine replacement therapy: many of the respondents in our survey said they would use it to quit smoking, continue to use it for as long as needed to quit smoking and begin use soon after receiving it. These responses provide confidence about the utility of mass distribution of nicotine replacement therapy.

As we expected, participants who intended to quit smoking were more interested in nicotine replacement therapy than those who intended to reduce or maintain their smoking. However, it is unclear why 42% of the respondents who intended to continue smoking the same amount said they would be interested in free nicotine replacement therapy. This finding perhaps reflected an eventual but not immediate intention to quit. Also interesting was our finding that prior use of nicotine replacement therapy predicted future interest in using it again, which could indicate 1 of 3 factors. First, prior users of nicotine replacement therapy are more positive about using it because they found it helpful in a past attempt to quit. Second, prior users may have a better knowledge of the expense associated with nicotine replacement therapy and thus be more appreciative of the opportunity to receive it free of charge. Finally, both past use and future interest could be driven by the respondents' general attitudes toward nicotine replacement therapy, such as whether it is helpful or dangerous.

The primary limitation of our study is that self-reports of intended behaviours do not always predict what people will actually do. Further research is needed to explore whether smokers who say they are interested in receiving free nicotine replacement therapy will actually consent to receiving it and use it to attempt to quit smoking.

This research has important policy implications. Our findings suggest that a substantial proportion of smokers are interested in nicotine replacement therapy and would agree to receive it free of charge as part of a public health initiative to reduce the prevalence of smoking. In addition, even smokers who have used nicotine replacement therapy in the past will most likely be receptive to recommendations by health professionals to use it as a way to successfully quit smoking.

@@ See related research paper by Eisenberg and colleagues, page 135, and related commentary by Ebbert and Hays, page 123

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Une version française de ce résumé est disponible à l'adresse www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/179/2/145/DC1

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Both authors were involved in the conception and design of the survey and the interpretation of the data. John Cunningham conducted the analyses. Both authors were involved in the drafting and revision of the article, and both approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: Funding for this study was provided through an arms-length educational grant from Johnson and Johnson Consumer Group of Companies. Beyond approving the theme of the survey, the company had no input on the content or execution of the survey or the preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: Peter Selby is an advisory board member with Pfizer Inc. and Sanofi-Aventis, a study consultant and adviser on the behavioural program for smoking cessation with VCC Inc., and a consultant with Johnson and Johnson Consumer Health Care, Pfizer Inc. and Sanofi-Aventis. He has also received speaker fees from Johnson and Johnson Consumer Health Care, Pfizer Inc. and Sanofi-Aventis. No competing interests declared for John Cunningham.

Correspondence to: Dr. John A. Cunningham, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 33 Russell St., Toronto ON M5S 2S1; john_cunningham@camh.net

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes JR. Motivating and helping smokers to stop smoking. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:1053-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Cummings KM, Fix B, Celestino P, et al. Reach, efficacy and cost-effectiveness of free nicotine medication giveaway programs. J Public Health Manag Pract 2006;12: 37-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Selby P, Zawertailo L, Dragonetti R, et al. Stop Smoking Therapy for Ontario Patients (STOP Study): methods for free NRT distribution. 13th World Conference on Tobacco OR Health; 2006 Jul 12–15; Washington (DC).

- 4.Giardina TD, Hyland A, Bauer UE, et al. Which population-based interventions would motivate smokers to think seriously about stopping smoking? Am J Health Promot 2004;18:405-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Shiffman S, Hughes J, Ferguson SG, et al. Smokers' interest in using nicotine replacement to aid smoking reduction. Nicotine Tob Res 2007;9:1177-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cunningham JA, Selby P. Past attempts and future intentions: quitting and reducing cigarette use in a representative sample of Canadian daily smokers. 13th annual meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; 2007 Feb 21–24; Austin (TX).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.