Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Ureteric stenting is a common urological procedure. Forgotten stents have a well-documented morbidity and mortality. Therefore, we asked the question, is a stent register an important factor in reducing the number of lost or overdue stents?

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a retrospective review of 203 patients who had ureteric stents inserted in the operating theatre, for the 5-year period 1 December 1998 to 1 December 2003. We analysed all stent cards, patient notes and theatre logs; where no record of stent removal was found, we contacted the patient, their GP or their local hospital.

RESULTS

A total of 191 patients were identified from the stent card register. An additional 12 patients were found from the theatre logs, but with no record in the stent card register. Of the 203 patients, 8 had bilateral stents. The most common indication for stenting was stone disease. Of the 203 patients, 11 had overdue stents and 51 had no record of the stents ever being removed. The 51 presumed ‘forgotten’ stents were traced, and it was found that 42 patients had had their stents removed by other hospitals, and 9 patients died with stents in situ, but before they were due for removal.

CONCLUSIONS

Our current stent card tracking system is ineffective, because it was infrequently reviewed. However, despite overdue and ‘forgotten’ stents which were removed by other hospitals, no patients came to any real harm and we had no lost stents. Our stent register system did not appear to play any role in terms of preventing stent loss, and it seems likely that there are other more effective safeguards in place to prevent this from happening. However, if a stent register was required at all, a computerised system would be preferable. Alternatively, patients could share some of the responsibility of stent tracking with their clinicians.

Keywords: Ureteric stents, Information systems, Registries

Ureteric stenting is a common method used for temporary and long-term drainage of an obstructed upper urinary tract. In our unit, we use Cook Sof-Flex® Multi-Length stents (Cook Urological Incorporated, Spencer, IN, USA). According to the stent manufacturer, Sof-Flex® Multi-Length stents should be removed or replaced within 6 months of insertion. Overdue or forgotten stents cause significant morbidity and mortality, e.g. urinary sepsis, encrusted stents and stent fractures.1–5 Therefore, ureteric stent registers are often used as a tracking system.6

In our unit, we use a stent card register. A stent card is completed for each stent inserted in theatre, and can be used to recall patients with stents overdue for removal. However, the register is time consuming to update and, hence, is infrequently reviewed. In addition, stents are often removed at other hospitals, and there is no reliable means of deleting this group of patients from the register.

Therefore, we asked the question, is a stent register an important factor in reducing the number of lost or overdue stents?

Patients and Methods

Patients who had ureteric stents inserted in the operating theatre at Epsom General Hospital (EGH) during the period 1 December 1998 to 1 December 2003 were identified from the stent card register and theatre logs retrospectively.

All the corresponding patient notes were reviewed for the following: (i) indication for stenting; (ii) duration of stent in situ; (iii) documentation of stent removal; and (iv) documentation of stent complications. We then followed up the missing stents by either contacting the patient, their GP or their local hospital.

Results

For the 5-year period studied, 203 patients had stents inserted in theatre. Of these, 191 (94.1%) patients were identified from the stent card register alone, and an additional 12 (5.9%) patients were found from the theatre logs, but with no record on the stent card register. Of the 203 patients, 8 had bilateral stents.

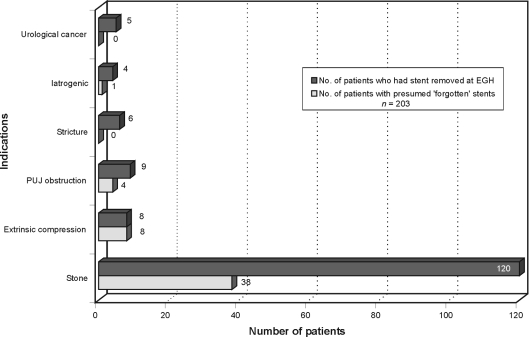

We found stone disease to be the most common indication for stenting, accounting for 158 of the 203 (77.8%) stents inserted. Other indications included 16 (7.9%) for extrinsic compression, 13 (6.4%) for pelvic-ureteric junction (PUJ) obstruction, 6 (3.0%) for strictures, 5 (2.5%) for iatrogenic reasons and 5 (2.5%) for urological cancer (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Indications for ureteric stenting.

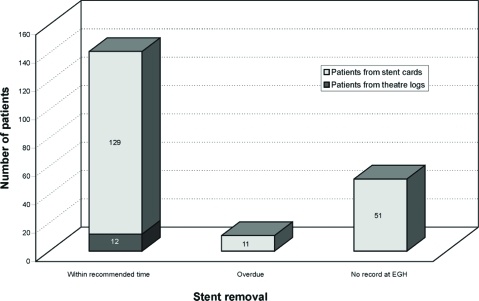

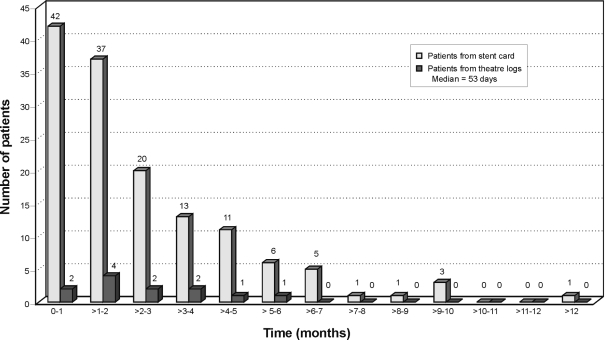

The majority of patients (141 [69.5%] consisting of 129 cases from the stent card register and 12 cases from the theatre logs) had stents removed within 6 months, i.e. within the manufacturer's recommendations, while 11 (5.4%) were overdue and 51 (25.1%) had no record of stent removal by our hospital (Fig. 2). A more detailed breakdown of the duration of stents in situ is shown in Figure 3, with a median time of 53 days.

Figure 2.

Length of time stents in situ.

Figure 3.

Time distribution of stents left in situ.

Of the 11 patients who had overdue stents, two developed simple urinary tract infections which were treated with oral antibiotics, one had an encrusted stent which was easily removed in the day-surgery unit, and the remaining 8 patients had no complications.

The 51 cases of presumed ‘forgotten’ stents were traced by contacting the patient, their GP or their local hospital. The indications for stent insertion in these cases included 38 for stone disease, 8 for extrinsic compression, 4 for PUJ obstruction, and 1 for iatrogenic causes (Fig. 1). It was found that 42 (82.4%) patients had had their stents removed by other hospitals, but within 6 months of their stents being inserted, with the time in situ ranging from 12–158 days. The indications for stent removal included 24 (57.1%) following definitive treatment or investigation (16 ureteroscopies, 5 retrograde studies, 2 extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy [ESWL], and 1 percutaneous nephrolithotomy [PCNL]), 15 (35.7%) for passed stones and 3 (7.1%) had stents changed. The timing of stent removal was appropriate in each case.

In 5 of the 42 cases, no referral had been made for stent removal at other hospitals prior to discharge from EGH, and patients were required to make their own arrangements to have their stents removed. The remaining 37 patients had their follow-up arranged prior to discharge. None of the 42 patients were subsequently followed up at EGH.

A total of 9 patients died with stents in situ, but before they were due for removal, of whom 1 died of urinary sepsis, 1 died of ischaemic heart disease and 7 died of malignancy.

Discussion

Using the current stent card system as a register, we found the majority of stents were inserted as a temporary measure to relieve stone obstruction. We achieved a 94.1% success rate of recording stents inserted in our theatres, but 5.9% had no record of stent insertion on the register. This was most likely due to human error and theatre staff not familiar with the stent card register and hence stent cards were not filled in. More importantly, until we conducted this study, the stent card register had failed to flag up 11 (5.4%) patients who had overdue stents, and 51 (25.1%) patients had no record of stent removal by our hospital. It became clear that the register was infrequently up-dated due to the cards requiring manual review which was time consuming. Moreover, stents were often removed at other hospitals, and there were no reliable means of removing this group of patients from the register. Interestingly, despite a total of 30.5% of overdue and presumed ‘forgotten’ stents, it had not led to any real harm or actual stent losses. The mortality was largely due to other medical reasons, and before the stents were due for removal. The patient that died from urinary sepsis originally presented with obstructed, infected kidneys secondary to ureteric stones, and stents were inserted to relieve the obstruction; despite this and intravenous antibiotics, the patient died 4 days later.

From our experience, it seems likely that there are other safeguards (e.g. booking or referring patients for stent removal at discharge) in place which have been effective, and certainly the stent card register did not appear to play any role in preventing stent loss due to ‘forgotten’ or overdue stents. Interestingly, all the stents recorded in the theatre logs but not on the stent card register were removed within the recommended time. This might imply that we do not need a stent card register at all.

If a stent register was required at all, a computerised system would be preferable.1,4,7,8 Ather et al.8 reviewed a computerised stent tracking system which automatically alerted patients and clinicians before the stents became overdue for removal. They concluded it lowered the incidence of overdue stents from 12.5% using the stent card system to 1.2% during a 1-year period with the computerised system.8 In our unit, 90% of stents were inserted by urologists in theatre, and the remaining 10% inserted by interventional radiologists. By using a computerised database accessible by all those responsible for inserting stents, there would be a universal database of all stents inserted that could be used to track stents. Certainly, this system would have alerted us to the overdue and presumed ‘forgotten’ stents. However, it does not solve the fundamental problem of human error of not registering patients onto the system, and it would not be able to separate the true forgotten stents from the group of patients that had their stents removed by other hospitals. Nonetheless, the computerised system still forms a fail-safe mechanism by automatically sending reminders to follow up overdue or presumed ‘forgotten’ stents.

Alternatively, we could consider providing more information for patients regarding their treatment9 and they could share the responsibility with their clinicians regarding tracking of their stents. We found that 5 patients organised their own further treatment and stent removal with their local hospitals and no stents were forgotten. This suggests that having patients play an active role in their treatment, by getting them to take responsibility for tracking of their stent, may be an effective means of reducing, or even preventing, stent loss. Certainly, there is evidence in other disciplines of medicine where patients adopt an active role in decision making and treatment which improves the effectiveness of clinical care.10

One way this could be achieved is with an information booklet, not too dissimilar from the yellow anticoagulation booklets. This would include essential information detailing the date and side of stent insertion, the indications and a planned date for removal. In addition, there could be details of whom patients should contact if their stents are not removed within the recommended time, and patients should be aware of complications from the stents. A copy of the information could also be sent to the GP so they can also keep a record and establish computerised reminders to check that stents have been removed when patients attend their practice.

In addition to the benefit of having patients take an active role in the management of their stents, involving the GP acts as an extra fail-safe in the prevention of lost stents. However, there are limitations, and these include a certain group of patients that would not be able, or willing, to share the responsibility, and because of the long interval between stent insertion and recommended removal, some patients may simply forget about their stents.

Conclusions

Our current stent card tracking system is ineffective, because it was infrequently reviewed and difficult to update. However, despite the overdue stents and presumed ‘forgotten’ stents being removed by other hospitals, no patients came to any real harm and we had no lost stents.

The stent register system did not appear to play any role in terms of preventing stent loss, and it seems likely that there are other, more effective, safeguards in place to prevent this problem. However, if a stent register was required at all, a computerised system would be preferable or, alternatively, patients could share the responsibility with the clinicians regarding tracking of their stents.

References

- 1.Lawrentschuk N, Russell JM. Ureteric stenting 25 years on: routine or risky? Aust NZ J Surg. 2004;74:243–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2004.02947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter S, Ringel A, Shalev M, Nissenkorn I. The indwelling ureteric stent: a ‘friendly’ procedure with unfriendly high morbidity. BJU Int. 2000;85:408–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00543.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolley D. Ureteric stents, far from ideal. Lancet. 2000;356:872–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02674-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh I, Gupta NP, Hemal AK, Aron M, Seth A, Dogra PN. Severely encrusted polyurethane ureteral stents: management and analysis of potential risk factors. Urology. 2001;58:526–31. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh V, Srinivastava A, Kapoor R, Kumar A. Can the complicated forgotten indwelling ureteric stents be lethal? Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:541–6. doi: 10.1007/s11255-004-4704-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finney RP. Experience with new double J ureteral catheter stent. J Urol. 1978;120:678–81. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCahy PJ, Ramsden PD. A computerized ureteric stent retrieval system. Br J Urol. 1996;77:147–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.87626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ather MH, Talati J, Biyabani R. Physician responsibility for removal of implants: the case for a computerized program for tracking overdue double-J stents. Tech Urol. 2000;6:189–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi HB, Newns N, Stainthorpe A, MacDonagh RP, Keeley FX, Jr, Timoney AG. The development and validation of a patient-information booklet on ureteric stents. BJU Int. 2001;88:329–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ. 1999;318:318–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7179.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]