Abstract

In the final article of his series on the NHS, Tony Delamothe looks at the effects of recent reforms and assesses the threat to its founding principles

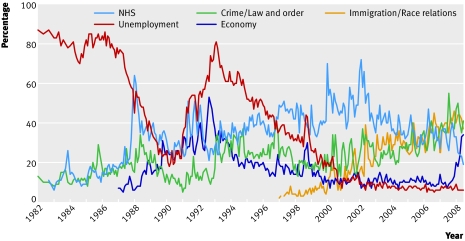

This week the NHS celebrates its 60th birthday. It should be its most benign anniversary in recent memory. Satisfaction levels are high,1 and the British public now rates the economy, crime, and race relations as more important problems than the NHS (figure).2 Increasing satisfaction with the NHS probably explains why the numbers of people buying private medical insurance have been falling since 2002.3 Last year the service made a surplus of at least £2bn (€2.5bn; $4bn) and is expected to make a further surplus this year.4 Productivity in hospitals is finally going up,5and the NHS is now the third most popular employer for UK graduates, after the BBC and Apple.6 Politically, it’s hard to detect any major difference between the policies of the Labour or Conservative parties towards the NHS, both of whom are falling over each other to be regarded as the natural custodians of the nation’s most cherished institution.

Public opinion on the biggest issues facing the United Kingdom, 1982-20082

Yet many working in the NHS are fearful of the ultimate consequences of recent policy changes, which have been driven by values very different from those that underpinned the NHS for most of its 60 years. Workers worry that the days of the NHS as proxy state religion are numbered (box 1), and they don’t like the alternatives.

Box 1 Losing our religion

“Thanks to the nurses and Nye Bevan

The NHS is quite like heaven.”

J B S Haldane (1964)

“Intrinsically the National Health Service is a church. It is the nearest thing to the embodiment of the Good Samaritan that we have in any respect of our public policy.”

Barbara Castle (1976)

“The National Health Service is the closest thing the English have to a religion, with those who practice in it regarding themselves as a priesthood. This made it quite extraordinarily difficult to reform.”

Nigel Lawson (1992)

“The model of health care as a secular church represents the tradition maintained and carefully tended over the decades by the disciples of Aneurin Bevan. Creating the NHS was seen as an act of social communion, celebrating the fact that all citizens were equal in the sight of a doctor”

Rudolf Klein (1995)

“The NHS is like a theological institution. Its adherents, most of the population of the United Kingdom, believe in it passionately . . . Like theological belief, belief in the NHS rests on assertions, apparently revealed truths—and woe betide those who try to say otherwise.”

Julia Neuberger 1999

“The NHS has taken on an iconic status in the eyes of both government and the electorate as politics has become less readily defined by ideology. Few may want to believe in the market or the state any more, or in socialism or capitalism, but most people seem able and willing to believe in the NHS.”

Anna Coote, 2004.

Of supermarkets and super markets

There was no inkling of the changes ahead when Tony Blair’s Labour government was elected in 1997. At −16%, net satisfaction with the NHS was at an all time low,7 and half the population rated the NHS as “the most important issue facing Britain today” (figure). To quote Labour’s election campaign song, things could only get better.8

Labour had no grand plans for health care when it came to power, other than to reverse some of the Conservatives’ recent changes. “First of all we’ll get rid of that Conservative internal market that has caused so much damage in the National Health Service, “promised Mr Blair in the run-up to the election. “We’ve had enough of running it like a supermarket—it’s not a supermarket, it’s a public service.”9

But the internal market, with its separation between purchasers and providers of health care, remained. Extra money began trickling in to the NHS to patch it up after years of government tightfistedness, but it was the publication of the NHS Plan in 2000 that marked the real beginning of the Blair government’s “adaptive evolutionary journey” into health care.10 11

The trickle of extra money became a flood when the government committed to raising healthcare spending to European levels. At about this time, a series of health service scandals convinced the government that as well as being altruistic and principled, healthcare providers could “also occasionally be inefficient, variable in quality, self interested, and unresponsive to patients’ preferences.”10 Trust in professionals to get on with the job was replaced by an intensive command and control regime of national targets, inspection and regulation, and published league tables. Such a regime had worked with teachers but proved less successful with doctors. A different blend of carrot and sticks would be needed.

During this phase, Westminster devolved some of its powers to new governing bodies in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, and early in the new century these countries began to pursue radically different healthcare policies from England’s (box 2).12 Most of what follows relates to the English reforms. In England, the Blair government reached for market solutions for elective care and diagnostic services, going far beyond the Conservatives’ wildest dreams. Competition, patient choice, and market contestability were the new buzz words, and the mechanisms to provide them were payment by results, practice based commissioning, foundation trusts, and the greater use of private providers. To increase their responsiveness to users, services were meant to be devolved as locally as possible. That these individual interventions actually added up to a “system reform programme,” however, only became obvious in retrospect.13

Place your bets

Since devolution, each country has developed a different model for its health service, as Greer describes12:

“Scotland has bet on professionalism in which it tries to align organisation with the existing structure of medicine. This means reducing layers of management and replacing them with clinical networks, increasing the role of professionals in rationing and resource allocation.

England has bet on markets in which independent trusts, similar to private firms, will contract with each other for care while approximately thirty regulatory organisations will ensure quality. Competition, management, and regulation will be the keys to getting value from health spending while severing the link between frontline health services and the Minister.

Wales has bet on localism.This means integrating health and local government in order to coordinate care and focus on determinants of health rather than treating the sick. It tries to use localism as the lever to make the NHS into a national Health service rather than a national Sickness service.

Northern Ireland, in and out of devolution, has continued to bet on permissive managerialism. This is a system that focuses on keeping services going in tough conditions and otherwise produces little overall policy and enforces less. It provides stability in difficult conditions—at the cost of no policy and with the benefit of local experimentation and variation.”

When Gordon Brown replaced Mr Blair as prime minister in 2007, his initial silence regarding market reforms, along with his earlier misgivings about a free market in health care, fuelled speculation that his government would throw Blair’s plans into reverse. But it emerged he had no plan B, and it was full steam ahead with the Blairite reforms. Setting out his plans for public sector reform earlier this year, Mr Brown confirmed: “A greater diversity of providers, more choice, and in many areas more competition will continue to ensure that services that fail to deliver are legitimately challenged and standards are forced upwards.”14

The relatively abrupt switch from a model based on social solidarity (socialism) to one based on choice and competition (capitalism) left many fearful for the survival of the NHS in ways that decades of underfunding hadn’t. How could the founding principles that seemed the embodiment of social solidarity survive in so alien a world? Yet at key moments since 1997 the Labour government has endorsed the founding principles, even using them recently to justify its unpopular opposition to copayments for drugs not provided by the NHS.

To what extent might they be endangered? At least theoretically, the market reforms should not endanger the principle of universality or that of a centrally funded service, free at the point of delivery. Introducing competition into the market, its proponents argued, would increase efficiency, making the available money go further. Moving services away from hospitals (expensive) into the community (cheap) would save money. Payment by results, according to a fixed national tariff, would have providers competing on quality, thereby driving quality up.

Where problems with the reforms might be predicted is over the principles of equity and comprehensiveness. The inevitable consequence of pushing decision making to as local a level as possible is that localities will come to different decisions and services will differ around the country. This would have been anathema to NHS architect, Aneurin Bevan, who pushed for central rather than local control as the only way to guarantee the same service for all.

What happened next?

Much has been claimed for the effects of the market reforms—both good and ill—but until now reliable information has been scarce. Fortunately, a comprehensive assessment of the effects of the reforms has just been published by the Audit Commission and the Healthcare Commission.13

The two commissions found no evidence that the reforms had produced their intended effects. Substantial service improvement occurred where system reforms hadn’t been implemented, and places that had implemented more of the reforms weren’t performing any better than places that had implemented few.

Foundation trusts

If anything, things are moving in the opposite direction to that which was intended. The hoped for transfer of power from hospitals to local providers isn’t happening. Foundation trusts are getting stronger than primary care trusts, whose commissioning function has been weakened by two reorganisations. The foundation trusts can hardly be blamed; they’re merely responding to incentives built into the system. Payment by results gives hospitals a clear incentive to expand their elective activity and thereby their income. Surpluses are required to achieve a low risk rating with the foundation trusts’ regulator, a prerequisite for borrowing money for further investment. By the end of the first six months of 2007-8, the trusts had accumulated cash surpluses of £1.5bn.

The commissions could find no good evidence that foundation trusts were delivering higher quality care as a result of their status: data from the Healthcare Commission suggest that although foundation trusts are generally higher performers, they started from a better position in terms of service delivery, efficiency, and financial standing.

General practices

Attempts to encourage practice based commissioning—meant to push decision making closer to the patient—have succeeded with only a minority of general practitioners. Nevertheless, 96% of practices received incentive payments for practice based commissioning in 2006-7, although 52% commissioned no new services. Primary care trusts were disappointed that general practices seemed more interested in providing new services themselves than in commissioning them from elsewhere, paying themselves from their commissioning budgets in the process. Incentives were also offered to general practices to provide patients with choice. The proportion of practices who received the maximum payment for this far outstripped the proportion of patients who could recall being offered a choice. It’s hard to escape the image of natives stripping the market’s missionaries of their trinkets, while never getting round to converting to their religion.

Some of the commissions’ implied criticisms of general practitioners seem over harsh. Their report lists the six most important factors influencing patient choice of hospital (in decreasing order): cleanliness, quality of care, waiting times, staff friendliness, reputation of hospital, and location.13 It then states that “Patients need choices presented to them on the basis of fact rather than anecdote or personal GP preference.” However, since the government currently collects data on only waiting times and hospital acquired infections, might not a general practitioner’s advice on the quality of care and reputation of hospital be useful? Regrettably (from the commissions’ point of view), some patients expect their general practitioners to “choose where they should go to receive their treatment after considering their condition and issues such as quality and outcomes, thus negating the need for the patient themselves to consider these factors.” The commissions’ solution: patients’ appetites for information to support patient choice need to be stimulated.

Patients

With their current low appetite for choice, patients aren’t fulfilling their historic destiny as the lever of change in the new healthcare market. Ever more carefully worded patient questionnaires have failed to uncover a vast, choice hungry constituency (table 1). In a Picker Institute survey of inpatients in 2006, on behalf of the Healthcare Commission, the three questions about choice were deemed to be among the 10 least important aspects of a hospital’s service out of the 82 inquired about.17 The Picker Institute reportedly told the commission that patients had so little interest in choice that there would be no point in asking more questions about it in the 2007 survey. 18

Patients’ responses (%) to surveys asking if they were given a choice about which hospital they were referred to, 2004-615 16

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 26 | 26 | 27 |

| No, but I would have liked a choice | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| No, but I did not mind | 58 | 57 | 55 |

Instead, what patients want is “a high quality, local hospital that they could access,” according to the commissions’ report.13 Its overall verdict is sobering: “Given that patient choice is having a limited impact on the quality of elective care to date, so far as we can identify, and given that patients have very little outcome data on healthcare providers, there needs—at least for the foreseeable future—to be a much greater focus on commissioning, contracting and regulatory processes for elective as well as non-elective care to really drive improvement. Choice alone does not appear to be strong enough to deliver this change.”

Diverse suppliers

A key part of the reforms was the transformation of the NHS from a monopoly provider of services to a system of competing different healthcare providers. To allow choice and competition it’s necessary to have spare capacity. The awareness that capacity needed expanding predated the market reforms and probably arose as the government found that devoting more money to the NHS in the late 1990s wasn’t reducing waiting lists as expected. That was because with bed occupancy rates high, the service was already working flat out. There followed a concordat with the private healthcare sector, allowing the NHS to negotiate with them over their spare capacity.

Later in the government’s adaptive evolutionary journey came the recognition that non-NHS suppliers could also be used as competitors to incumbents. Independent sector treatment centres were a particularly controversial example, for many of the reasons summarised in the commissions’ report (box 3). What the report doesn’t say is that some primary care trusts were leant on to contract with these centres and that clinical negligence claims against centres were transferred back to the public sector in 2004.19 20

Box 3 Going spare

According to the report of the Audit Commission and Healthcare Commission, “Many of the NHS’ concerns about the ISTC [independent sector treatment centre] programme stem from the cost of the programme. The costs to the DH [Department of Health] of establishing the first and second phases of the ISTC programme was £146 million at the end of 2006/07. In addition to these set-up costs, payments to ISTCs were set around 11 per cent higher than the equivalent cost in the NHS, to encourage entry into the market and to cover the cost of new buildings and refurbishments. Moreover, the Wave 1 contracts also provided ISTCs with a guaranteed revenue stream for a period of five years and were structured on a ‘Take or Pay’ basis, so ISTCs were paid at the guaranteed activity levels, regardless of whether the activity was undertaken. This meant that, where patients were not referred or chose not to be treated at the ISTCs, PCTs who were contractually obliged to pay for activity that did not take place, lost money. The cost of guaranteeing activity that was not performed in ISTCs is classified as commercially sensitive so cannot be calculated.”13

Twenty four treatment centres from the first wave are now operational, but half the phase two contracts have been cancelled, largely because the NHS doesn’t require their extra capacity. The commissions consider that further large-scale entry of the independent sector to this market at present is unlikely, given that there won’t be central assistance with set-up costs.

Have they fulfilled their purpose? In 2005 the Department of Health, predicted that they might provide up to 15% of elective surgical procedures; the Audit Commission’s estimate for 2007-8 is 1.8%. Frequently repeated anecdotes attest that the centres instilled the fear of competition into NHS providers, which hence upped their game, but the commissions “found it hard to demonstrate this conclusively through data analysis.” The results of independent research are expected to throw more light on this later this year.

Simon Stevens, former health adviser to Mr Blair, may be right that most primary care has been privately provided since 1911, with only the contractual types of private provider differing.11 Yet a very different sort of private provider has been winning the majority of primary care contracts recently. Local suppliers have been underbid by subsidiaries of large multinational corporations, apparently prepared to subsidise “loss leaders” to gain a foothold in the English market.21 Initially, they targeted general practices that had failed or had severe doctor shortages. Now they seem to be winning contracts ahead of highly competent, local teams.21

In addition, the private sector might be used to “turn around” failing NHS hospitals, according to a recent government announcement. There is a precedent for this: the Tribal group took over Birmingham’s Good Hope Hospital in 2003 and lifted its performance rating from zero to one star. After the new owners failed to stem huge overspends, however, the hospital was taken over by the nearby Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust.22

The competitive landscape

The commissions’ report notes many things going astray in the market free for all. It regrets the absence of “any regional or central oversight to ensure that commissioner and provider plans are based on similar, sound assumptions.” Without it, many hospital trusts are planning to expand activity, even though there is a drive to move more care out of hospitals. The result could be services simultaneously developed by different organisations, leading to over capacity and subsequent waste and inefficiencies.

The report quotes a departmental directive that calls for NHS bodies to work together when this is in the best interest of patients. But how could this happen when providers are meant to be at each others’ throats for the market to work properly? Confused? You’re not alone. The most poignant sentence of the report reads: “Some staff, including NHS managers, are still not clear how to manage the tension between collaboration, which is often in the best interests of the patient, and competition, which can also lead to improvements for patients.”

Payment by results—which pays providers for the number and type of patients treated—must add appreciably to administrative costs. Yet its impact on overall efficiency, according to the commissions, has so far been “questionable.” Moving contracts between suppliers, even if it ultimately saves money, has its costs. Of a primary care trust’s experience of tendering its genitourinary medical service, the report comments, “The process of going out to tender and subsequently selecting a provider had a significant financial cost to the PCT [primary care trust] in terms of diverting management time and opportunity costs.” Multiplying those costs by all the services tendered by all the primary care trusts comes to a very big number.

The report is silent on the overall costs of establishing and running the new healthcare market. In the run up to the 1997 general election the Labour party estimated that the creation of the Conservative’s internal market had added £1.5bn to the NHS’s management costs.23 Now that it is in power, might it provide estimates of what its reform programme has cost, and how much of its extra spending on the NHS it comprises? Claims for the need to preserve secrecy around contracts with private sector suppliers is a worrying omen (box 3), given that they are proliferating.

The commissions conclude that the government’s reform programme hasn’t yet delivered, although it may be too early to write it off completely. Recent commentators, however, have sounded a note of caution about the limits of market based reforms to improve the efficiency of healthcare systems.24 Don Berwick and Sheila Leatherman, two close observers of the NHS, wrote: “Policy has focused on market forces and choice. Private companies with values far different from those of the NHS are being invited into delivery and commissioning. As Americans, we know dependence on market forces for constructive change is playing with fire.”25 European experience is no more encouraging. According to international public health academics, Allyson Pollock and Sylvia Godden, “Recent evaluations of Europe-wide attempts to improve health system efficiency by introducing consumer choice through market competition found no concrete evidence that the introduction or extension of choice ‘works.’”19

Searching for the next big thing

As if tacitly agreeing that England’s current model of choice and competition won’t deliver, some of the people I talked to in preparing this series have shifted their attention to what may be the next big thing —integrated care organisations.26 27 These would entail “collaboration between practices, specialists, and their clinical teams in both the commissioning and provision of care,” emulating some of the integrated delivery systems in the United States, such as the not for profit health maintenance organisation Kaiser Permanente and the government funded Veterans Health Administration. Integrated care organisations would then compete for patients. It’s argued that such arrangements would address the needs of patients with chronic illness, whose care is unaffected by the current reforms. A choice of such organisations would need to be available in a relatively small area for meaningful competition to be possible. Pilot programmes are expected to be announced in health minister Ara Darzi’s final report on the future of the NHS.

All healthcare reforms have been driven by laudable attempts to make the available money go further, yet whether each round of reforms yields appreciable net savings is moot. What isn’t disputed is the toll they exact from the staff who undergo them. In their review of the quality initiatives undertaken in the NHS since 1997, Sheila Leatherman and Kim Sutherland commented that “there is often a political imperative to reform the system, sometimes in ways that are unrealistically ambitious and costly both in terms of financial resources and staff goodwill, in order ‘to make one’s mark.’ Too often this results in unceasing serial change with reform fatigue and subsequent cynicism in the health service.”28 The commissions’ report on the market reforms calls for “a prolonged moratorium on any further national top down reorganisation of NHS commissioners.”

Just as these messages were being delivered, the ink was drying on Lord Darzi’s final report, described by the current secretary of state for health as a “once in a generation review” of the NHS in England.

As Lord Darzi’s report endorses the founding principles of the NHS, the “ends” of the NHS seem likely to survive—as they have for the past 60 years—despite the “means” being in constant flux. The most thoughtful birthday present the NHS could receive would be an assurance that after implementation of the Darzi inspired reforms there will be an extended period of calm before the next round of reforms is unleashed.

I have greatly benefited from discussions with John Appleby, Jennifer Dixon, Jon Ford, Iona Heath, Rudolf Klein, Allyson Pollock, Richard Smith, Simon Stevens, and Nick Timmins. I also thank the BMA library for its exemplary service.

Competing interests: None declared.

Cite this as: BMJ 2008;337:a524

This is the last of six articles marking 60 years of the NHS

References

- 1.Delamothe T. How the NHS measures up. BMJ 2008;336:1469-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Political Monitor Trends: The most important issues facing Britain today Ipsos MORI. www.ipsos-mori.com/content/political-monitor-trends-the-most-important-issues.ashx

- 3.Hawe E. OHE compendium of health statistics 2008 19th ed. Abingdon: Radcliffe, 2008

- 4.Timmins N. Row as NHS surplus exceeds £2bn. Financial Times 2008. June 6.

- 5.Timmins N. NHS productivity in hospitals rises. Financial Times 2008. May 12.

- 6.Top employer ranking 2008. Financial Times 2008. (graduate recruitment supplement) May 1:8.

- 7.British Social Attitudes Information System. www.britsocat.com

- 8.Appleby A, Alvarez-Rosete A. Public responses to NHS reform. In: Park A, Curtice J, Thomson K, Bromley C, Phillips M, Johnson M, eds. British social attitudes: two terms of new labour: the public’s reaction London: NCSR, 2005:109-33.

- 9.Delamothe T. When Blair went to market. BMJ 2007;335:1100 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens S. Reform strategies for the English NHS. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:37-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowper A. The business of reform and the future market. Br J Health Care Manage 2006;12:361-6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greer SL. Four way bet: how devolution has led to four different models for the NHS London: Constitution Unit, 2004

- 13.Healthcare Commission, Audit Commission. Is the treatment working? Progress with the NHS system reform programme. London: Audit Commission, 2008

- 14.Brown G. Time for the third act in public sector reform. Financial Times 2008. March 10.

- 15.Healthcare Commission. Primary care trusts survey of patients 2005 www.healthcarecommission.org.uk/nationalfindings/surveys/healthcareprofessionals/surveysofnhspatients/primarycare.cfm

- 16.Department of Health. National survey of local health services 2006. www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Statistics/StatisticalWorkAreas/Statisticalhealthcare/DH_073494

- 17.Boyd J. The 2006 inpatients importance study report Picker Institute Europe,2007. www.nhssurveys.org/survey/486

- 18.Carvel J. Hospital choice irrelevant, say patients. Guardian 2007. May 14.

- 19.Pollock AM, Godden S. Independent sector treatment centres: evidence so far. BMJ 2008;336; 421-424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Pollock AM. NHS plc London: Verso, 2005

- 21.Cole A. Private practice. BMJ 2008;336:1406-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timmins N. Latest cure failed its first clinical trial. Financial Times 2008. June 5.

- 23.Webster C. The National Health Service: a political history Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002

- 24.Nichols LM, Ginsburg PB, Berenson RA, Christianson J, Hurley RE. Are market forces strong enough to deliver efficient health care systems? Confidence is waning. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:8-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berwick DM. Leatherman S. Steadying the NHS. BMJ 2006;333:254-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Light D, Dixon M. Making the NHS more like Kaiser Permanente. BMJ 2004;328:763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ham C. Competition and integration in the English National Health Service. BMJ 2008;336:805-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leatherman S, Sutherland K. The quest for quality: refining the NHS reforms London: Nuffield Trust, 2008