Abstract

Cerebral deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides is a pathological hallmark of Alzheimer disease. Intramembranous proteolysis of amyloid precursor protein by a multiprotein γ-secretase complex generates Aβ. Previously, it was reported that CD147, a glycoprotein that stimulates production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), is a subunit of γ-secretase and that the levels of secreted Aβ inversely correlate with CD147 expression. Here, we show that the levels and localization of CD147 in fibroblasts, as well as postnatal expression and distribution in brain, are distinct from those of integral γ-secretase subunits. Notably, we show that although depletion of CD147 increased extracellular Aβ levels in intact cells, membranes isolated from CD147-depleted cells failed to elevate Aβ production in an in vitro γ-secretase assay. Consistent with an extracellular source that modulates Aβ metabolism, synthetic Aβ was degraded more rapidly in the conditioned medium of cells overexpressing CD147. Moreover, modulation of CD147 expression had no effect on ε-site cleavage of amyloid precursor protein and Notch1 receptor. Collectively, our results demonstrate that CD147 modulates Aβ levels not by regulating γ-secretase activity, but by stimulating extracellular degradation of Aβ. In view of the known function of CD147 in MMP production, we postulate that CD147 expression influences Aβ levels by an indirect mechanism involving MMPs that can degrade extracellular Aβ.

Alzheimer disease is an age-associated neurodegenerative disorder that is clinically manifested by the progressive loss of memory and cognitive functions. An early event in the development of Alzheimer disease is the aggregation and deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ)4 peptides in the brains of affected individuals. Aβ is derived from type I transmembrane protein, termed amyloid precursor protein (APP), through sequential cleavage by β- and γ-secretases (1, 2). γ-Secretase is a multimeric protein complex consisting of presenilin (PS1 or PS2), nicastrin, APH1, and PEN-2 as core subunits (2). The exact functional contribution of each γ-secretase subunit to enzyme activity has not been fully elucidated, but multiple lines of evidence suggest that PS1, a protein that accumulates as endoproteolytically processed N-terminal (NTF) and C-terminal (CTF) fragments, is the catalytic center of γ-secretase, whereas nicastrin appears to facilitate substrate recruitment (3–5). Coexpression of these four transmembrane proteins is sufficient to reconstitute γ-secretase activity in yeast, an organism that lacks orthologous proteins (6). Gene knock-out and small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown studies have demonstrated that Aβ production is compromised in the absence of any one of these core components (7–10). Collectively, these latter studies establish that PS1, nicastrin, APH1, and PEN-2 are necessary and sufficient for γ-secretase processing of APP.

The biogenesis, maturation, stability, and steady-state levels of γ-secretase complex subunits are codependent (reviewed in Ref. 11). For example, limiting expression of any one of the integral components affects the post-translational maturation and stability of the other subunits, indicating that their assembly into high molecular mass complexes is a highly regulated process that occurs during biosynthesis of these polypeptides. In this regard, the heavily glycosylated type I membrane protein nicastrin does not mature and exit the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in cells lacking PS1 expression (12). On the other hand, PS1 fails to undergo endoproteolysis to generate stable NTFs and CTFs in cells lacking nicastrin, APH1a, or PEN-2 expression (11). The use of detergents with dissimilar solubilization properties and different biochemical purification methods has led to discrepant size predictions of the active γ-secretase complexes, with estimates ranging from 250 kDa to 2 MDa (13, 14). Although a recent study has shown that active γ-secretase contains one of each of these four essential components (15), it is notable that the estimated sizes of the γ-secretase complexes exceed the sum of the four integral subunits. Thus, it is generally anticipated that one or more cofactors might associate with the four integral subunits of the γ-secretase complex and that these polypeptides modulate enzyme activity.

Recently, two type I membrane proteins, CD147 and p23, have been shown to co-immunoisolate with the γ-secretase complex and regulate Aβ levels (16, 17). CD147 (also called EMMPRIN (extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer), Basigin, neurothelin, and M6 leukocyte activation antigen) is a multifunctional cell-surface type I transmembrane protein that stimulates matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) secretion (18). p23 (also called TMP21) is a member of the p24 type I transmembrane protein family involved in vesicular trafficking between the ER and Golgi (19). siRNA-mediated knockdown of CD147 or p23 expression causes dose-dependent increases in the levels of secreted Aβ (16, 17). Nevertheless, because only a small fraction of the cellular pool of CD147 or p23 remains complexed with γ-secretase at steady state, the precise mechanisms by which these proteins modulate γ-secretase activity remain obscure. For example, p23 influences Aβ levels by modulating γ-secretase cleavage of APP and by regulating secretory trafficking of APP and possibly APP secretases (20). In this study, we show that CD147 does not directly modulate γ-secretase cleavage of APP substrate in an in vitro γ-secretase assay. Instead, we found evidence for enhanced degradation of Aβ in medium conditioned by cells overexpressing CD147, suggesting the potential involvement of CD147-induced MMP secreted forms in modulating extracellular Aβ levels. Consistent with this indirect mechanism, the absence of PS1 and nicastrin has no effect on CD147 stability and subcellular localization, and CD147 expression fails to influence γ-secretase subunit expression and lipid raft association. A distinct expression pattern and distribution of CD147 and nicastrin in brain further support our view that CD147 regulates extracellular Aβ levels via mechanisms independent of γ-secretase processing of APP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

cDNA Constructs and Oligonucleotides—Human CD147 cDNA was generated by reverse transcription-PCR using total RNA isolated from HEK293 cells. C-terminally Myc/His-tagged CD147 was constructed by subcloning CD147 cDNA into the pAG3-Myc-His vector. The following primers were used to generate RNA duplexes using a Silencer siRNA construction kit (Ambion): CD147 siRNA, AAGACCTTGGCTCCAAGATACCCTGTCTC and AAGTATCTTGGAGCCAAGGTCCCTGTCTC; and scrambled siRNA, AACTCTTCCGCGTAGCAAAGACCTGTCTC and AATCTTTGCTACGCGGAAGAGCCTGTCTC. The cDNA encoding C-terminally Myc-tagged APP (APPswe-6Myc) (a kind gift from Dr. Alison Goate) (21) was subcloned into the pCB6 vector. An expression plasmid encoding truncated Notch1 (mNotchΔE) was kindly provided by Dr. Jeffrey S. Nye.

Cell Lines—Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HEKswe cells were maintained in the presence of 200 μg/ml G418 (22). HEK293 cells were transfected with CD147-Myc-His plasmid, and stable transfectants were selected as pools in the presence of 200 μg/ml Zeocin. PS1-/-/PS2-/- and NCT-/- cells stably expressing PS1 or nicastrin were generated by retroviral infections of MEFs and selected in the presence of 4 μg/ml puromycin as described previously (23). CD147 and scrambled siRNA duplexes were transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and analyzed after 48 h.

Co-immunoprecipitation—PS1-/-/PS2-/- cells stably expressing either vector or PS1 were lysed in buffer containing 1% CHAPSO, 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, and a mixture of protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of proteins from the post-nuclear supernatants were used for co-immunoisolation using the PS1NT antibody as described previously (24).

Protein Analysis, Immunostaining, and Detergent-resistant Membrane (DRM) Isolation—Total protein lysates from cultured cells and mouse brain harvested during embryonic and postnatal developmental stages were prepared essentially as described previously (25). Antibodies against γ-secretase subunits, APP, and organelle markers have been described (26). Goat anti-CD147 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-human CD147 (Chemicon) monoclonal antibodies were used to detect CD147. Immunofluorescence staining and isolation of DRMs from Lubrol WX lysates of cultured cells by discontinuous flotation density gradients were performed as described (26, 27). Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 30-μm sagittal sections of 2-month-old C57BL/6J mouse brain with rabbit anti-nicastrin (SP718; 1:1000) or goat anti-CD147 (1:5000) antibody as described (28).

In Vitro γ-Secretase Assays—Membranes prepared from HEK293 cells transfected with either scrambled or CD147 siRNA were used to examine γ-secretase activity using C100-FLAG substrate as described previously (14). Briefly, cells were homogenized 10 times using a glass-Teflon homogenizer in buffer containing 10 mm MOPS, 10 mm KCl, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixture. The homogenate was subjected to centrifugation at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was saved, and the pellet was passed through one more round of homogenization. Pooled supernatants were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer and centrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The pellet-containing membranes were used for in vitro γ-secretase activity assay in the presence or absence of 1 μm L685,458 to establish the specificity of the assay.

Aβ Digestion Assay Using Synthetic Aβ—9 μl of culture medium was incubated with 6 ng of synthetic Aβ40 or Aβ42 for 14 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the reaction mixtures were resolved by gradient SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting using monoclonal antibody 6E10.

Assay for Aβ-degrading Metalloproteases in Culture Medium—The culture medium from either HEK293 cells or HEK293 cells stably overexpressing CD147 was incubated with metalloprotease-specific inhibitors to indirectly identify the type of Aβ-degrading metalloproteases induced by CD147. 30 μl of conditioned medium from HEKswe cells (as the source of secreted Aβ) was incubated overnight in a 37 °C incubator with 30 μl of conditioned medium from either naïve HEK293 cells or CD147-overexpressing cells. To inhibit the degradation of Aβ during the incubation, different protease inhibitors were included as indicated. The final concentrations of the inhibitors used were 10 mm 1,10-phenanthroline (Aldrich), 5 mm EDTA, 2.5 μm thiorphan (Sigma), 10 μm Nap (a kind gift from Dr. Malcolm Leissring), 100 μm actinonin, and 50 μm GM6001 (BIOMOL International). Aβ remaining intact at the end of the incubation period was analyzed by Western blotting and quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) following the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen).

Zymography Analysis of Conditioned Medium—6 μl of conditioned medium from either naïve HEK293 cells or CD147-overexpressing cells was mixed with nonreducing sample buffer and fractionated on a 7.5% SDS gel containing 0.1% gelatin. After electrophoresis, the gel was developed and stained with Coomassie Blue as described previously (29).

RESULTS

Stability of CD147 Is Not Affected in the Absence of γ-Secretase Core Components—If CD147 is a bona fide component of γ-secretase, one would anticipate that the behavior of the polypeptide with respect to regulated stability would be similar to that already established for other core components of the complex, i.e. that the stability and maturation of γ-secretase subunits are co-regulated. To examine the stability of CD147 in cells lacking PS1/PS2, we employed fibroblasts derived from PS1-/-/PS2-/- embryos and their wild-type (WT) littermates. As reported previously (9, 12), maturation of endogenous nicastrin was impaired, and the steady-state levels of endogenous PEN-2 were significantly reduced in PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs compared with WT MEFs. In contrast and for reasons that are presently not clear, endogenous CD147 levels were elevated in PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs (Fig. 1A, first and second lanes). To address the possibility that the observed difference in the levels of CD147 may be a result of cell-to-cell variation in the MEFs analyzed, we generated stable pools of PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs overexpressing human PS1 by retroviral infection. Stable expression of PS1 in PS1-/-/PS2-/- cells restored mature glycosylation of nicastrin and stabilized PEN-2, but did not markedly affect CD147 protein levels (Fig. 1A, third and fourth lanes). Similarly, CD147 levels were not reduced in NCT-/- or APH1ab-/- MEFs compared with WT MEFs, as would be expected if this polypeptide were a γ-secretase component (data not shown). Thus, the stability of CD147 is not co-regulated in a manner such as PS1, nicastrin, APH1, and PEN-2, indicating that CD147 is unlikely to be an integral subunit of the γ-secretase complex.

FIGURE 1.

Subcellular localization of CD147 in the absence of γ-secretase subunit expression. A, comparison of the steady-state levels of CD147 and γ-secretase subunits. Total cell lysates from WT and PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs and PS1-/-/PS2-/- pools stably transduced with retrovirus harboring empty vector or human PS1 cDNA were probed with the indicated antibodies. Similar results were obtained in two independent pools of stably transduced cells. FL, full-length; mat, mature; imm, immature; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. B, co-immunoprecipitation analysis of CD147 with γ-secretase subunits. PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs stably overexpressing empty vector or human PS1 were lysed in 1% CHAPSO, co-immunoprecipitated using the PS1NT antibody as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and probed with the indicated antibodies. Note that the endogenous γ-secretase components nicastrin and PEN-2 co-immunoprecipitated with PS1; CD147 was not detected as part of the immunoprecipitated complex. Similar results were obtained in co-immunoprecipitation analysis of mouse N2a neuroblastoma cells and HEK293 cells. C, analysis of the indicated PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs pools by double immunofluorescence staining with anti-CD147 antibody (green) and antibody against GM130 (cis-Golgi) or cadherin (cell surface) (red). The right panels represent image overlays. Scale bar = 10 μm. These images are representative of two independent experiments, and similar results were observed in analysis of NCT-/- MEFs.

To further confirm the above findings, we also performed co-immunoprecipitation analyses in PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs. Aliquots of 1% CHAPSO lysates of PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs stably overexpressing human PS1 were immunoprecipitated with the PS1 N-terminal antiserum PS1NT. The resulting immune complexes were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-CD147 antibody. The blots were then sequentially reprobed with antibodies against nicastrin, PEN-2, and PS1 CTFs. The results show efficient co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous γ-secretase core components nicastrin and PEN-2 with human PS1 expressed in PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs (Fig. 1B). In contrast, CD147 failed to co-immunoprecipitate with PS1, nicastrin, and PEN-2 under these conditions (Fig. 1B). Thus, we conclude that CD147 is not a stoichiometric subunit of the γ-secretase complex.

Subcellular Localization of CD147 Is Unaffected by the Absence of γ-Secretase Core Components—Several studies have demonstrated that the integral components of γ-secretase cooperatively mature and exit the ER. CD147 is a type I membrane protein that is principally localized to the cell surface (30). To examine the subcellular localization of CD147 in the absence of γ-secretase core components, we performed confocal microscopic analysis of CD147 in PS1-/-/PS2-/- and NCT-/- MEFs. There was no observable difference in the overall distribution of CD147 between PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs and those expressing human PS1. Co-staining with organelle markers GM130, a cis-Golgi-associated protein, and cadherin, a cell-surface protein, showed similar CD147 localization in the Golgi and at the cell surface (Fig. 1C). Similar results were obtained in NCT-/- cells (data not shown). Thus, the subcellular localization of CD147 is not dependent on the expression of PS1 or nicastrin.

DRM Association of CD147 and the Core Components of the γ-Secretase Complex Is Not Codependent—We and others (27, 31) have reported that the PS1 NTF and CTF, mature nicastrin, APH1, and PEN-2 are localized within detergent-insoluble membrane microdomains, which are enriched in the lipid raft markers flotillin-2 and prion protein. Interestingly, we found that the assembly of core components precedes DRM association of the γ-secretase complex. For example, in NCT-/- fibroblasts, the low levels of APH1 and PEN-2 that escape degradation reside in non-raft domains (27). Therefore, we investigated whether DRM association of CD147 is dependent on the presence of γ-secretase complex components. To this end, we analyzed DRM association of CD147 in PS1-/-/PS2-/- and NCT-/- MEFs and compared these profiles with that of either WT MEFs or NCT-/- MEFs stably overexpressing nicastrin, respectively. By sucrose density gradient fractionation, we found that CD147 was enriched in Lubrol WX-resistant membrane fractions of WT MEFs (Fig. 2A). However, DRM association of CD147 was unchanged in PS1-/-/PS2-/- and NCT-/- cells (Fig. 2). Thus, expression of γ-secretase subunits does not regulate lipid raft association of CD147.

FIGURE 2.

DRM association of CD147 is not dependent on the presence of γ-secretase core components. A, WT and PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs were solubilized in 0.5% Lubrol WX at 4 °C for 30 min. The lysates were then subjected to flotation centrifugation on discontinuous sucrose gradients as described previously (27). The gradients were harvested from the top (fractions 1–12; top to bottom), and the distribution of PS1, CD147, syntaxin-6, and flotillin-2 was determined by fractionating 60-μl aliquots of gradient fractions 4–12. B, NCT-/- MEFs stably infected with retrovirus harboring empty vector or WT nicastrin cDNA were lysed and fractionated as described above. Note that fractions 1–3 contained no detectable signal for any protein analyzed. The raft marker flotillin-2 was recovered primarily in fractions 4 and 5, and the non-raft protein γ-adaptin was recovered in detergent-soluble fractions 9–12. The data are representative of two independent experiments; moreover, DRM fractionation was performed in WT, NCT-/-, and APH1ab-/- MEFs with similar results. FL, full-length.

Several lines of evidence in cell culture and mouse brain indicate that lipid raft microdomains are the principal sites of amyloidogenic processing of APP (26, 31). Therefore, we considered the possibility that the levels of CD147 might affect the association of PS1 with DRMs and thereby influence APP processing in lipid rafts. To address this issue, we prepared membranes from HEK293 cells with different levels of CD147 expression. We observed that neither elevated nor lowered expression of CD147 had a discernible effect on the DRM association of endogenous PS1 (Fig. 3). Thus, we find it implausible that CD147 modulates lipid raft localization of γ-secretase.

FIGURE 3.

DRM association of PS1 is not affected by CD147 overexpression or depletion. A, HEK293 cells transfected with an empty vector and stably transfected cells overexpressing CD147 were lysed in 0.5% Lubrol WX and analyzed by flotation on sucrose gradients. Lipid raft localization of CD147, PS1 NTF, and flotillin-2 was analyzed by Western blotting. B, HEK293 cells transfected with CD147 or scrambled siRNA were fractionated as described above to analyze DRM distribution of PS1 and CD147.

Postnatal Expression and Distribution of CD147 in Brain Show Lack of Correlation with Nicastrin—Our failure to document that CD147 levels, subcellular localization, and DRM association are co-regulated by the core components of γ-secretase in cultured cells was perplexing and prompted us to assess the expression patterns of CD147 in brain, arguably a more relevant setting. Unfortunately, little information is available pertaining to CD147 expression in brain, and hence, we sought to characterize the expression profile of CD147 relative to the γ-secretase core components PS1 and nicastrin in mouse brain during postnatal developmental stages. Western blot analyses of total brain lysates showed that CD147 protein levels were remarkably low at embryonic day 15, but readily detectable at birth. CD147 expression increased by 3.5-fold between postnatal days 0 and 7 and remained at this high level through 12 months of age (Fig. 4, A and B). A completely different expression pattern was observed for the γ-secretase core components PS1 and nicastrin, with high levels of expression occurring between embryonic day 15 and postnatal day 7 and then gradually declining after postnatal day 14 (Fig. 4, A and B). These results reveal that the developmental expression patterns of the γ-secretase core components PS1 and nicastrin do not correlate with that of CD147.

FIGURE 4.

Uncorrelated protein expression profile between CD147 andγ-secretase integral components in mouse brain. A, lysates from mouse brains harvested at the indicated stages of embryonic (E), postnatal (P), and adult development were analyzed by immunoblotting. mo, month; yr, year. B, signal intensities of CD147 and nicastrin were determined from three independent samples and normalized to N-cadherin levels. For comparison, the normalized expression level of each protein at postnatal day 0 was set to 1, and the level of expression relative to postnatal day 0 was plotted. C, shown is the immunocytochemistry for nicastrin and CD147 in the hippocampus and overlying cortex of 2-month-old C57BL/6J mouse brain. D and E, higher magnifications are shown of the cortex and pyramidal cell layer in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Nicastrin immunoreactivity was essentially restricted to neuronal cell bodies in the cortex and hippocampus, whereas CD147 immunoreactivity was excluded mainly from the cell bodies. Intense CD147 immunoreactivity was found in the CA1 stratum oriens (so), stratum radiatum (sr), and also stratum lacunosum-moleculare (slm). Note that anti-CD147 antibody also labeled blood vessels. DG, dentate gyrus; gcl, granule cell layer; ml, molecular layer; sp, stratum pyramidale. Scale bar = 100 μm. These images are representative of two independent experiments.

Next, we also observed remarkable differences in the cellular distributions of nicastrin and CD147 in adult mouse brain using immunohistochemical staining. We found that nicastrin immunoreactivity was restricted mainly to neuronal cell bodies throughout the cortex and to pyramidal as well as granule cells in the hippocampus (Fig. 4C). CD147 immunoreactivity was excluded from neuronal cell bodies, and punctate CD147 staining was seen mainly in neuronal processes. Intense CD147 staining was observed in the CA1 region of the hippocampus and upper layers of the cortex, whereas CA2 was only weakly labeled, and the dentate gyrus region was not labeled (Fig. 4C). The striking difference in CD147 immunoreactivity at the junction of the CA1 and CA2 regions was reproducible in all sections examined from multiple animals. The mutually exclusive pattern of nicastrin and CD147 distribution was particularly obvious in the pyramidal cell layer of the hippocampus, where nicastrin was found in the cell body and CD147 immunoreactivity was found largely in the neuronal processes within the stratum oriens, stratum radiatum, and stratum lacunosum-moleculare (Fig. 4E). These results do not exclude the possibility of an interaction between CD147 and γ-secretase components present at low levels in neuronal processes, but strongly suggest that CD147 is involved mainly in functions other than the regulation of the γ-secretase complex in neurons.

CD147 Depletion Increases Extracellular Aβ Independent of α- and β-Secretase Processing of APP—Consistent with the report by Zhou et al. (16), transfection of CD147 siRNA at increasing concentrations revealed a dose-dependent increase in Aβ levels in the medium of HEK293 cells transiently overexpressing human WT APP695 (Fig. 5A). In these studies, we found no significant change in the levels of full-length APP, APP CTFs, or secreted APPα (Fig. 5A) These results suggest that the increase in secreted Aβ associated with the depletion of CD147 expression is independent of α- and β-secretase processing of APP. To confirm these data, we analyzed the effect of siRNA-mediated knockdown of CD147 expression on secreted Aβ levels in cells stably expressing APPswe. We observed a small but consistent increase in secreted Aβ levels in cells transfected with CD147 siRNA compared with those transfected with control siRNA, whereas the steady-state levels of α- and β-CTFs remained unchanged (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results indicate that siRNA-mediated depletion of CD147 expression increases the levels of Aβ in medium without significant changes in the levels of APP CTFs, the penultimate substrates of γ-secretase, hence arguing against an effect on β- or α-secretase processing of full-length APP.

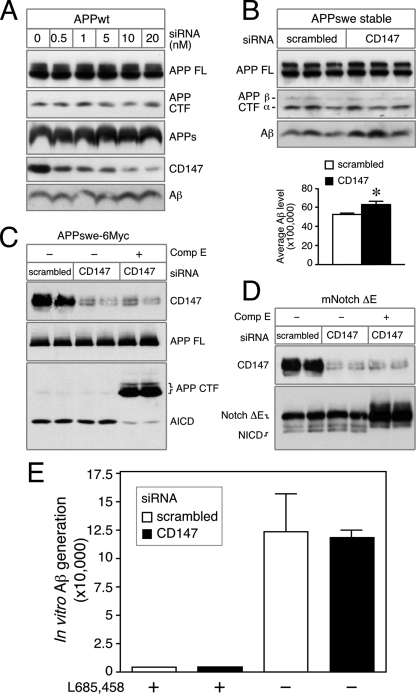

FIGURE 5.

Increase in Aβ levels associated with the depletion of CD147 is independent of APP secretase activities. A, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with increasing doses of CD147 siRNA together with WT APP695 cDNA. 50 μg of total cell lysates was analyzed by Western blotting to examine the levels of full-length (FL) APP, APP CTF, and CD147. The levels of secreted APP (APPs) and Aβ conditioned medium were analyzed by immunoblotting. B, HEKswe cells were transfected with scrambled or CD147 siRNA and analyzed as described above. The levels of Aβ were quantified by ELISA and plotted (mean ± S.E., n = 3; *, p < 0.02). C, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with either scrambled or CD147 siRNA duplex and a plasmid encoding APP-swe-6Myc. Compound E (Comp E; 10 nm) was added as indicated to inhibit γ-secretase activity. D, conditions were the same as described for C except that cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding mNotchΔE instead of APP. E, membranes prepared from siRNA-treated cells were used in an in vitro assay to monitor γ-secretase processing of recombinant C100-FLAG substrate (14). The reactions were performed in the presence or absence of 1 μm L685,458 to establish the specificity of the assay. Aβ40 generated by γ-secretase cleavage of the substrate was quantified by ELISA and plotted (mean ± S.E., n = 3).

In addition to the extracellular release of Aβ, γ-secretase cleavage of APP CTFs at the “ε-site” releases the APP intracellular domain (AICD) from the membrane. Similarly, ε-cleavage of Notch releases the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). To examine the potential influence of CD147 on ε-cleavage of substrates, we first asked whether depletion of CD147 has any effect on AICD production. We found that there was no quantitative difference in the levels of AICD generated by cleavage of C-terminally epitope-tagged APP (APP695-6Myc) in transfected HEK293 cells following siRNA-mediated depletion of CD147 expression (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, CD147 depletion had no discernible effect on the generation of the NICD following γ-secretase cleavage of N-terminally truncated Notch (mNotchΔE) at the ε-site (Fig. 5D). Pretreatment of transfected cells with Compound E markedly diminished the production of the AICD and NICD, establishing the specificity of these commonly used cell-based γ-secretase assays. Thus, we conclude that CD147 does not modulate ε-cleavage of substrates by the γ-secretase.

CD147 Effect on Aβ Levels Is Not Mediated through Direct Modulation of γ-Secretase Activity—CD147 has been implicated in many cellular functions, including the induction of MMPs (18) and cell-surface trafficking of the monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 (32). Therefore, we asked whether the influence of CD147 on extracellular Aβ levels could be mediated through direct modulation of γ-secretase, as was reported previously (16), or by an indirect mechanism unrelated to γ-secretase processing of APP β-CTFs. To this end, we asked whether we could recapitulate the cell-based findings of a role for CD147 in Aβ production in a well established in vitro reconstitution system that employs detergent-solubilized membranes in conjunction with a purified C100 substrate (14). The rationale for using the in vitro assay is that it selectively reports on Aβ production by γ-secretase cleavage of recombinant C100-FLAG substrate, thereby formally ruling out the potential influence of CD147 on trafficking of APP or the β-CTF, exocytosis or endocytosis of Aβ, and stability of extracellular Aβ, which might account for the increase in Aβ levels in the conditioned medium of CD147-depleted cells observed in both our experiments and the earlier study. As an internal control for the enzyme selectivity in this in vitro assay, we incubated parallel reactions with L685,458, a potent transition-state isostere inhibitor of γ-secretase. Surprisingly, the in vitro Aβ assays revealed that membranes isolated from CD147-depleted HEK293 cells did not increase Aβ production compared with those of control siRNA (Fig. 5E). Compared with the obvious increase in extracellular Aβ levels followed by CD147 depletion in intact cells, the results obtained from in vitro Aβ assays were unanticipated. The above results strongly suggest that the regulatory function of CD147 on extracellular Aβ levels is unlikely mediated through its proposed role as a regulatory subunit of the γ-secretase complex, which modulates intramembranous proteolysis of substrates.

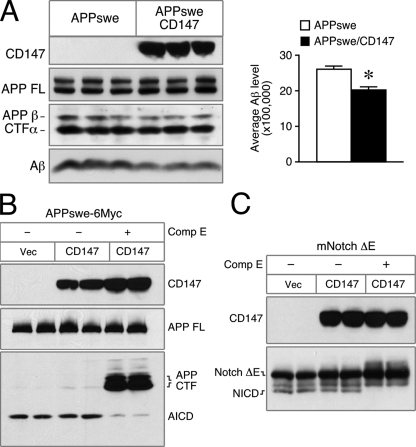

Reduced Stability of Synthetic Aβ in Medium Conditioned by HEK293 Cells Overexpressing CD147—The series of preceding experiments failed to confirm the proposal that CD147 plays a role in Aβ production by modulating γ-secretase levels and activity. Hence, we were left with the scenario that CD147 modulates extracellular Aβ levels via an indirect mechanism that engages a known functional attribute of the polypeptide. Among the diverse functions assigned to CD147 in diverse physiological and pathological systems, a major function of CD147 is to stimulate production of a set of MMPs, some of which are shed into the extracellular space. Thus, we reasoned that MMPs that are regulated/induced by CD147 might modulate extracellular Aβ levels. To address this possibility, we generated stable HEK293 cells overexpressing CD147 and observed a small decrease in Aβ in the conditioned medium compared with that of parental HEK293 cells (Fig. 6A). As we had predicted based on siRNA studies, overexpression of CD147 had no effect on the levels of AICD or NICD production in cells transfected with APP695-6Myc or mNotchΔE, respectively (Fig. 6, B and C).

FIGURE 6.

Decrease in Aβ levels associated with CD147 overexpression is independent of APP secretase activities. A, overexpression of CD147 reduces Aβ in conditioned medium. Total cell lysate and the conditioned medium from HEK293 cells stably expressing either APPswe or APPswe and Myc-tagged CD147 were used to analyze the levels of full-length (FL) APP and Aβ. Total Aβ levels in the conditioned medium were quantified by ELISA and plotted (mean ± S.E., n = 3; *, p < 0.0005). B, HEK293 cells were transiently cotransfected with an empty vector (Vec) or with Myc-tagged CD147 cDNA along with APPswe-6Myc. Compound E (Comp E;10 nm) was added as indicated to inhibit γ-secretase activity. C, conditions were the same as described for B except that cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding mNotchΔE instead of APP. AICD and NICD experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

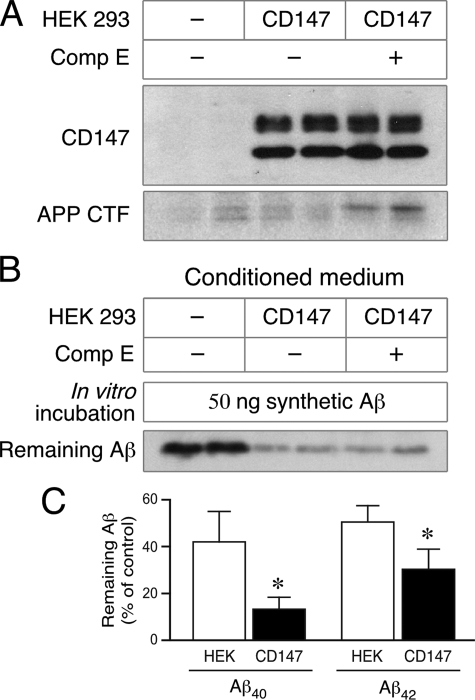

To investigate whether the observed decrease in extracellular levels of Aβ is mediated through CD147 induction of MMPs that are known to be capable of degrading Aβ (29, 33–36), we examined the stability of synthetic Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides in the conditioned medium of HEK293 cells transfected with an empty vector or stable CD147 cells. For this assay, we incubated aliquots of conditioned medium (containing undetectable levels of endogenous Aβ) with 50 ng of synthetic Aβ40 peptides at 37 °C overnight and performed Western blotting to detect synthetic Aβ40 remaining in the reaction. Surprisingly, there was considerable loss of synthetic Aβ in the reactions containing culture medium from CD147-overexpressing cells compared with HEK293 cells (Fig. 7B). After 14 h of incubation in vitro, the medium conditioned by CD147-overexpressing cells degraded significantly higher levels of input Aβ (nearly 90 and 70% of input Aβ40 and Aβ42, respectively, by the medium of CD147 cells versus 60 and 50% of input Aβ40 and Aβ42 by the medium of naïve HEK293 cells). To further rule out any contribution of γ-secretase to extracellular degradation of synthetic Aβ potentiated by CD147 overexpression, we treated stable CD147 cells treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor Compound E prior to collecting the conditioned medium. In vitro Aβ degradation assays showed that the medium conditioned by stable CD147 cells degraded Aβ to the same degree regardless of the differences in their γ-secretase activity, i.e. treated or not with Compound E (Fig. 7, A and B). Thus, CD147-mediated extracellular degradation of Aβ levels by CD147 is independent of γ-secretase activity.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of Aβ40 and Aβ42 degradation by the conditioned medium from HEK293 or HEK293 cells overexpressing CD147. A and B, CD147 potentiation of extracellular Aβ degradation is independent of γ-secretase activity. Naïve HEK293 cells or CD147-overexpressing cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 10 nm Compound E (Comp E) overnight, and their conditioned media were collected. A, Western blots of detergent lysates show CD147 overexpression and an increase in endogenous APP CTFs by Compound E treatment. B, aliquots of the conditioned media were mixed with 50 ng of synthetic Aβ40, and the mixtures were incubated at 37 °C. After a 14-h incubation, the mixtures were resolved on a Tris/Tricine gel and blotted with 26D6 to detect the remaining Aβ40 peptides. C, synthetic Aβ40 or Aβ42 was incubated for 14 h with medium conditioned by naïve HEK293 cells or cells stably overexpressing CD147. Aβ40 and Aβ42 remaining intact at the end of the incubation period were quantified by Western blotting, and the percentage of Aβ remaining was calculated relative to the levels in reactions containing fresh culture medium (mean ± S.E., n = 8; *, p < 0.001).

A recent report has linked MMP-2 and MMP-9 to Aβ degradation (29). To examine the possibility that these two enzymes might be involved in Aβ degradation in the conditioned medium of CD147-overexpressing cells, we performed gelatin-substrate zymography (Fig. 8A). We failed to detect differences in the levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities in the culture medium of CD147-overexpressing cells relative to that of naïve HEK293 cells. This result ruled out the contribution of these two enzymes and indicated that other protease(s) likely contribute to enhanced Aβ degradation in CD147-conditioned medium. Therefore, we mixed several metalloprotease inhibitors with the conditioned medium from CD147-overexpressing cells and then incubated these mixtures with Aβ secreted from HEKswe cells for 15 h at 37 °C (Fig. 8B). As a control, we used the conditioned medium from naïve HEK293 cells in the absence of inhibitors. Each of the inhibitors used in this assay showed different levels of inhibition of Aβ degradation. EDTA and 1,10-phenanthroline exhibited the highest level of inhibition, indicating metalloprotease(s) are involved in Aβ degradation. Thiorphan and Nap, a neprilysin inhibitor and an insulin-degrading enzyme inhibitor, respectively, as well as two MMP inhibitors, actinonin and GM6001, also inhibited Aβ degradation. Although these results cannot identify a single enzyme activity that is responsible for enhanced Aβ degradation in the conditioned medium of CD147-overexpressing cells, they could imply that one or more metalloproteases or MMPs are involved in this degrading activity. At present, the identity of the protease(s) in the conditioned medium of CD147-overexpressing cells is elusive, but it remains an active subject of investigation.

FIGURE 8.

Assays of CD147-dependent proteases that degrade Aβ in the medium. A, gelatin-substrate zymography shows no difference in MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities in culture medium from CD147-overexpressing cells relative to medium conditioned by naïve HEK293 cells. Lanes 2 and 3 contain recombinant MMP-9 and MMP-2, respectively. B, conditioned medium from CD147-overexpressing cells was incubated with secreted Aβ (medium from HEKswe cells) as described under “Experimental Procedures” in the presence or absence of different protease inhibitors. The conditioned medium from naïve HEK293 cells was used as a control in the absence of protease inhibitor. The levels of remaining Aβ were either visualized by Western blotting or quantified by ELISA and plotted. Note that for unknown reason, the levels of Aβ in medium containing 1,10-phenanthroline (1,10-phen) were consistently underestimated by ELISA. These experiments were repeated three times.

DISCUSSION

CD147 was previously identified as a protein associated with γ-secretase complex in detergent-solubilized HeLa cell membranes (16). These earlier studies revealed that siRNA knockdown of CD147 caused a dose-dependent increase in secreted Aβ levels. Remarkably, the mechanism(s) by which CD147 expression modulated extracellular Aβ levels were not determined at the time of publication, and information has not emerged in the interim in this regard. In this study, we have provided a detailed examination of the potential regulatory role of CD147 in the γ-secretase complex and now offer several novel insights. First, we have provided several lines of in vitro and in vivo evidence to suggest that CD147 expression, stability, and localization are regulated independently of the core subunits of γ-secretase. Furthermore, we failed to observe a detectable interaction between CD147 and γ-secretase complex subunits using a co-immunoprecipitation condition widely used by several groups to immunoaffinity purify the active γ-secretase complex (for example, see Ref. 14). Second, although we confirmed that depletion of CD147 in a human cell line modulates extracellular Aβ levels similarly as reported previously in Chinese hamster ovary cells (16), we failed to demonstrate that CD147 modulates Aβ production in an in vitro γ-secretase reconstitution assay. Moreover, we have shown that overexpression or depletion of CD147 expression failed to affect AICD or NICD generation in transfected cells. Thus, we have formally ruled out direct modulation of γ-secretase by CD147. Third, we have reported that medium conditioned by cells overexpressing CD147 had higher levels of Aβ-degrading activities, indicating that the function of CD147 in modulating MMPs may be responsible for the elevated degradation of extracellular Aβ. Collectively, these results suggest that the dose-dependent increase of Aβ in the conditioned medium of CD147-depleted cells observed in both our studies and the previous report (16) is mediated through CD147-dependent Aβ-degrading MMPs in the culture medium rather than direct modulation of γ-secretase activity, as was proposed previously.

In agreement with the data presented in the previous report by Zhou et al. (16), we found that depletion of CD147 in cultured HEK293 cells led to an increase in the steady-state levels of Aβ in the conditioned medium, but without discernible changes in the levels of CTFs derived from α- and β-secretase processing of APP. Although these findings suggested a role for CD147 in the modulation of γ-secretase processing of APP CTFs, additional studies were required to validate this notion. However, CD147 expression had no effect on the levels of AICD or NICD production in transfected cells. More important, in vitro γ-secretase assays performed using membranes purified from cells in which CD147 was depleted failed to show an increase in Aβ production, thus formally ruling out direct modulation of γ-secretase activity by CD147. In this regard, CD147 differs from p23/TMP21, another type I membrane protein that co-purified with γ-secretase complexes and was found to regulate γ-secretase activity (17). We recently reported that depletion of p23 elevated Aβ production in the same in vitro γ-secretase assay employed in the CD147 experiments described above (20). Thus, unlike the case of p23 depletion, which caused an increase in Aβ levels in both intact cells and in vitro assays, depletion of CD147 failed to exert any influence on Aβ production in vitro. This unexpected finding prompted us to explore alternative interpretations of the data that emerged from CD147 knockdown studies showing increased levels of Aβ in the conditioned medium described here and in the earlier report (16).

Many different cellular functions have been ascribed to CD147, including induction of several metalloproteases (37), cell adhesion (38), retinal cell development (39), T-cell activation (40, 41), and calcium mobilization (42). The ability of CD147 to induce multiple MMPs, including MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-3, has been well documented, and this is the basis of the alternative name EMMPRIN (18). Thus, we reasoned that the influence of CD147 on Aβ levels might be mediated through an indirect mechanism involving extracellular MMPs that degrade Aβ in the cultured medium. Indeed, studies that directly assessed the stability of synthetic Aβ peptides demonstrated enhanced Aβ degradation when incubated with medium conditioned by cells overexpressing CD147. Incubation of CD147 cells with Compound E, a potent γ-secretase inhibitor, did not have any discernible effect on the Aβ-degrading activity in the conditioned medium, formally ruling out any connection between γ-secretase activity and CD147-mediated Aβ-degrading activity (Fig. 7). Inhibitory profiles from EDTA and 1,10-phenanthroline strongly suggest the involvement of metalloprotease, whereas partial inhibition of Aβ degradation by GM6001 and actinonin might indicate that more than one MMP is involved in the degradation.

Studies by independent groups previously demonstrated that subunits of the γ-secretase complex cooperatively mature and traffic through the secretory pathway; incomplete assemblies are incapable of exiting the ER and are eventually degraded (reviewed in Ref. 11). In contrast to the well established codependent stability of the core γ-secretase subunits, we have shown that the stability or subcellular localization of CD147 in the Golgi and plasma membrane was unaffected in cells lacking either PS1/PS2 or nicastrin expression. It is also evident from our studies that the postnatal developmental expression profile of CD147 in mouse brain markedly differs from those of PS1 and nicastrin. Furthermore, unlike the overlapping neuronal distribution observed for nicastrin and PS1 in all major areas of adult rat brain (28), we found non-overlapping cellular distributions of CD147 and nicastrin in neurons within the cortex and hippocampus (Fig. 4D). Based on these data alone, it is implausible that all γ-secretase complexes in these neurons are bound to CD147 or subject to CD147 modulation. Nevertheless, our results cannot exclude the possibility that CD147 localized largely at the cell surface/neuronal processes modulates a small subset of active γ-secretase localized in these neuronal compartments.

How can we reconcile with the apparently discrepant data that CD147 co-purifies with the γ-secretase complex, but is not involved in the regulation of its enzyme activity? Both CD147 and the γ-secretase complex localize to cholesterol- and sphingolipid-enriched membrane microdomains, raising the possibility that co-purification in certain detergents might not necessarily represent bona fide protein-protein interaction, but rather co-isolation of several proteins that are tightly packed in membrane rafts. In this regard, CD147 interacts with caveolin-1 in a cholesterol-dependent manner and has been shown to be a potent modulator of lipid rafts in T-lymphocytes (43, 44). Nonetheless, we have demonstrated that membrane raft distribution of CD147 and γ-secretase occurs independently of one another, ruling out a role for CD147 in lipid raft targeting of the γ-secretase complex.

Despite the strengths of our findings, it remains plausible that transient interactions between distinct subcellular populations of CD147 and γ-secretase may be of physiological relevance. In this regard, the interaction of nicastrin and Rer1p, a transmembrane protein that is located primarily in the cis-Golgi and functions in the retrieval of a variety of ER membrane proteins lacking KKXX or KDEL signals, has recently been demonstrated (45). Similarly, it remains to be determined whether CD147, localized primarily at the cell surface, is involved only in the targeting to or retention of a very small pool of γ-secretase complexes at the cell surface in a manner not dissimilar from the reported CD147-dependent trafficking of the monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT4 to the cell surface (32). In any event, although the significance of the potential CD147·γ-secretase complex interaction is not yet apparent, our data unambiguously demonstrate that CD147 regulates secreted Aβ levels by mediating proteolytic degradation in the extracellular milieu. Further studies to identify and characterize the protease(s) responsible for CD147-dependent extracellular turnover of Aβ are critical and may provide the foundation for novel therapeutic targets focused on enhancing Aβ degradation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Wim Annaert and Bart De Strooper (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology, Belgium) for the gift of PS1-/-/PS2-/- MEFs and Drs. Tong Li and Philip C. Wong (The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore) for the gift of NCT-/- and APH1ab-/- MEFs. We thank Dr. Toshio Kitamura (University of Tokyo) for providing retroviral vector and packaging cells. We thank M. Sekiguchi and K. Watanabe for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AG021495 and AG019070 (to G. T.) and AG026660 (to Y.-M. L.). This work was also supported by Grants-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas 17025046 and 18023037 from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to N. I.), by an Alzheimer's Association investigator-initiated research grant (to G. T.) and new investigator research grant (to K. S. V.), and by grants from the American Health Assistance Foundation (to G. T. and S. S. S.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Aβ, β-amyloid; APP, amyloid precursor protein; PS, presenilin; NTF, N-terminal fragment; CTF, C-terminal fragment; siRNA, small interfering RNA; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; CHAPSO, 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonic acid; DRM, detergent-resistant membrane; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; WT, wild-type; AICD, APP intracellular domain; NICD, Notch intracellular domain; Tricine, N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

References

- 1.Vassar, R. (2004) J. Mol. Neurosci. 23 105-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwatsubo, T. (2004) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14 379-383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe, M. S., Xia, W., Ostaszewski, B. L., Diehl, T. S., Kimberly, W. T., and Selkoe, D. J. (1999) Nature 398 513-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, Y.-M., Xu, M., Lai, M. T., Huang, Q., Castro, J. L., DiMuzio-Mower, J., Harrison, T., Lellis, C., Nadin, A., Neduvelil, J. G., Register, R. B., Sardana, M. K., Shearman, M. S., Smith, A. L., Shi, X. P., Yin, K. C., Shafer, J. A., and Gardell, S. J. (2000) Nature 405 689-694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah, S., Lee, S. F., Tabuchi, K., Hao, Y. H., Yu, C., LaPlant, Q., Ball, H., Dann, C. E., III, Sudhof, T., and Yu, G. (2005) Cell 122 435-447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edbauer, D., Winkler, E., Regula, J. T., Pesold, B., Steiner, H., and Haass, C. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5 486-488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Strooper, B., Saftig, P., Craessaerts, K., Vanderstichele, H., Guhde, G., Annaert, W., Von Figura, K., and Van Leuven, F. (1998) Nature 391 387-390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li, T., Ma, G., Cai, H., Price, D. L., and Wong, P. C. (2003) J. Neurosci. 23 3272-3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma, G., Li, T., Price, D. L., and Wong, P. C. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25 192-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takasugi, N., Tomita, T., Hayashi, I., Tsuruoka, M., Niimura, M., Takahashi, Y., Thinakaran, G., and Iwatsubo, T. (2003) Nature 422 438-441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vetrivel, K. S., Zhang, Y. W., Xu, H., and Thinakaran, G. (2006) Mol. Neurodegener. 1 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leem, J. Y., Vijayan, S., Han, P., Cai, D., Machura, M., Lopes, K. O., Veselits, M. L., Xu, H., and Thinakaran, G. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 19236-19240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimberly, W. T., LaVoie, M. J., Ostaszewski, B. L., Ye, W., Wolfe, M. S., and Selkoe, D. J. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 6382-6387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, Y.-M., Lai, M. T., Xu, M., Huang, Q., DiMuzio-Mower, J., Sardana, M. K., Shi, X. P., Yin, K. C., Shafer, J. A., and Gardell, S. J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 6138-6143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato, T., Diehl, T. S., Narayanan, S., Funamoto, S., Ihara, Y., De Strooper, B., Steiner, H., Haass, C., and Wolfe, M. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 33985-33993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou, S., Zhou, H., Walian, P. J., and Jap, B. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 7499-7504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, F., Hasegawa, H., Schmitt-Ulms, G., Kawarai, T., Bohm, C., Katayama, T., Gu, Y., Sanjo, N., Glista, M., Rogaeva, E., Wakutani, Y., Pardossi-Piquard, R., Ruan, X., Tandon, A., Checler, F., Marambaud, P., Hansen, K., Westaway, D., St. George-Hyslop, P., and Fraser, P. (2006) Nature 440 1208-1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabison, E. E., Hoang-Xuan, T., Mauviel, A., and Menashi, S. (2005) Biochimie (Paris) 87 361-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenne, N., Frey, K., Brugger, B., and Wieland, F. T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 46504-46511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vetrivel, K. S., Gong, P., Bowen, J. W., Cheng, H., Chen, Y., Carter, M., Nguyen, P. D., Placanica, L., Wieland, F. T., Li, Y.-M., Kounnas, M. Z., and Thinakaran, G. (2007) Mol. Neurodegener. 2 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, J., Brunkan, A. L., Hecimovic, S., Walker, E., and Goate, A. (2004) Neurobiol. Dis. 15 654-666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim, S. H., Ikeuchi, T., Yu, C., and Sisodia, S. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 33992-34002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onishi, M., Kinoshita, S., Morikawa, Y., Shibuya, A., Phillips, J., Lanier, L. L., Gorman, D. M., Nolan, G. P., Miyajima, A., and Kitamura, T. (1996) Exp. Hematol. 24 324-329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, Y. W., Luo, W. J., Wang, H., Lin, P., Vetrivel, K. S., Liao, F., Li, F., Wong, P. C., Farquhar, M. G., Thinakaran, G., and Xu, H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 17020-17026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thinakaran, G., Borchelt, D. R., Lee, M. K., Slunt, H. H., Spitzer, L., Kim, G., Ratovitsky, T., Davenport, F., Nordstedt, C., Seeger, M., Hardy, J., Levey, A. I., Gandy, S. E., Jenkins, N. A., Copeland, N. G., Price, D. L., and Sisodia, S. S. (1996) Neuron 17 181-190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vetrivel, K. S., Cheng, H., Kim, S. H., Chen, Y., Barnes, N. Y., Parent, A. T., Sisodia, S. S., and Thinakaran, G. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 25892-25900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vetrivel, K. S., Cheng, H., Lin, W., Sakurai, T., Li, T., Nukina, N., Wong, P. C., Xu, H., and Thinakaran, G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 44945-44954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kodam, A., Vetrivel, K. S., Thinakaran, G., and Kar, S. (2008) Neurobiol. Aging 29 724-738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin, K.-J., Cirrito, J. R., Yan, P., Hu, X., Xiao, Q., Pan, X., Bateman, R., Song, H., Hsu, F. F., Turk, J., Xu, J., Hsu, C. Y., Mills, J. C., Holtzman, D. M., and Lee, J.-M. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 10939-10948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang, W., Chang, S. B., and Hemler, M. E. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15 4043-4050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng, H., Vetrivel, K. S., Gong, P., Meckler, X., Parent, A., and Thinakaran, G. (2007) Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 3 374-382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson, M. C., Meredith, D., and Halestrap, A. P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 3666-3672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Backstrom, J. R., Lim, G. P., Cullen, M. J., and Tokes, Z. A. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16 7910-7919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwata, N., Higuchi, M., and Saido, T. C. (2005) Pharmacol. Ther. 108 129-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White, A. R., Du, T., Laughton, K. M., Volitakis, I., Sharples, R. A., Xilinas, M. E., Hoke, D. E., Holsinger, R. M., Evin, G., Cherny, R. A., Hill, A. F., Barnham, K. J., Li, Q. X., Bush, A. I., and Masters, C. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 17670-17680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan, P., Hu, X., Song, H., Yin, K., Bateman, R. J., Cirrito, J. R., Xiao, Q., Hsu, F. F., Turk, J. W., Xu, J., Hsu, C. Y., Holtzman, D. M., and Lee, J.-M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 24566-24574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sameshima, T., Nabeshima, K., Toole, B. P., Yokogami, K., Okada, Y., Goya, T., Koono, M., and Wakisaka, S. (2000) Int. J. Cancer 88 21-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho, J. Y., Fox, D. A., Horejsi, V., Sagawa, K., Skubitz, K. M., Katz, D. R., and Chain, B. (2001) Blood 98 374-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshimoto, M., Sagara, H., Masuda, K., and Hirosawa, K. (1998) Exp. Eye Res. 67 331-340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasinrerk, W., Fiebiger, E., Stefanova, I., Baumruker, T., Knapp, W., and Stockinger, H. (1992) J. Immunol. 149 847-854 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch, C., Staffler, G., Huttinger, R., Hilgert, I., Prager, E., Cerny, J., Steinlein, P., Majdic, O., Horejsi, V., and Stockinger, H. (1999) Int. Immunol. 11 777-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang, Y., Jiang, J., Dou, K., and Chen, Z. (2005) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 84 59-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang, W., and Hemler, M. E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 11112-11118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staffler, G., Szekeres, A., Schutz, G. J., Saemann, M. D., Prager, E., Zeyda, M., Drbal, K., Zlabinger, G. J., Stulnig, T. M., and Stockinger, H. (2003) J. Immunol. 171 1707-1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spasic, D., Raemaekers, T., Dillen, K., Declerck, I., Baert, V., Serneels, L., Fullekrug, J., and Annaert, W. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176 629-640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.