Summary of Recent Advances

Integrins are α/β heterodimeric adhesion glycoprotein receptors that regulate a wide variety of dynamic cellular processes such as cell migration, phagocytosis and growth and development. X-ray crystallography of the integrin ectodomain revealed its modular architecture and defined its metal-dependent interaction with extracellular ligands. This interaction is regulated from inside the cell (inside-out activation), through the short cytoplasmic α and β integrin tails, which also mediate biochemical and mechanical signals transmitted to the cytoskeleton by the ligand-occupied integrins, which effect major changes in cell shape, behavior and fate. Recent advances in the structural elucidation of integrins and integrin binding cytoskeleton proteins are the subject of this review.

Introduction

Integrin-mediated cell adhesion plays a central role in the formation and remodeling of tissues and organs in multicellular organisms [1]. Integrins bind extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins through their large ectodomain, and engage via their short cytoplasmic tails the cytoskeleton. These integrin-mediated linkages on either side of the plasma membrane are dynamically-linked; the cytoskeleton controls affinity and avidity of the integrin ectodomain and thus modulate the ECM, and integrin binding to ECM changes the shape and composition of the cytoskeleton beneath [2]. Forces generated as a result of cytoskeleton contraction or ECM rigidity are applied across the plasma membrane through integrins, and contribute to the conformational changes in these receptors and their anchoring proteins, and to the nature of the biochemical signals initiated. The composition and morphology of integrin-dependent adhesions (focal complexes/ podosomes, focal adhesions and fibrillar adhesions) vary with the cell type, matrix and integrin, and may switch from one adhesion contact to another. In motile cells, high affinity integrin-based focal complexes form in protrusive lamellepodia. The rearward pull of actin filaments by myosin motors, applies force on the initial ECM-integrin-cytoskeleton linkages, eliciting fast accumulation of anchoring proteins that transform focal complexes into focal adhesions, with larger contact developing on stiffer matrix, thus directing cell movement [3,4]. Focal adhesions disassemble at the trailing edge, disengaging ECM from integrins, which recycle to the leading edge, establishing new matrix interactions thus allowing cell advancement. Focal adhesions can also transform into fibrillar adhesions that can modify the structure and rigidity of the ECM, contributing to tissue remodeling and repair.

In this communication, we review the structure of integrins in their unliganded and ligand-occupied states, evaluate the conformational rearrangements associated with integrin activation, and describe the structures, conformations and adhesion dynamics of key cytoskeleton anchoring proteins that transduce outside-in integrin signaling.

Crystallographic and NMR studies of the integrin ectodomain

Structure of the αA domain

The 18 α- and 8 β-subunits of integrins assemble into 24 distinct receptors in mammals, and segregate into two groups, one containing and the other lacking an extra von Willebrand factor type A domain (vWFA, known as αA or αI in integrins) in their α-subunits. αA mediates divalent-cation binding to extracellular ligands in αA-containing integrins [5]. αA is a GTPase-like domain in which the catalytic site at the apex is replaced with a conserved metal-ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS), which is occupied by a divalent cation. αA exists naturally in two conformations closed (low affinity) and open (high affinity)[6,7]. The open form is distinguished from the closed form by inward movement of the n-terminal α1, restructuring of the F-strand/α7 loop (F/α7 loop) and a 2-turn downward movement of the c-terminal α7 helix (reviewed in [8]). These tertiary changes produce rearrangements in the 3 surface loops that form MIDAS, which allow occupancy of MIDAS by an acidic residue from an exogenous ligand that provides the sixth coordination site for the bound metal ion, replacing a water molecule. The closed and open states exist in an equilibrium that favors the former by a ratio of ∼10:1 [9]. Mutations that deform the c-terminal α7 helix [10], its hydrophobic contacts with the central strand [11] or that favor its downward displacement, generate high affinity or intermediate states [12].

Crystal structure of the αVβ3 ectodomain

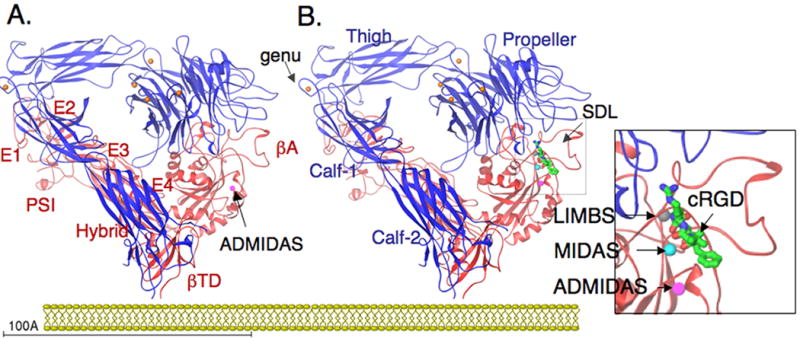

The crystal structure of the ectodomain from the αA-lacking integrin, αVβ3, was determined in unliganded (in the presence of Ca2+ or Mn2+) and ligand-bound states [13-15](Figure 1A, B). αV consists of four domains: an n-terminal seven-bladed β-propeller, an Ig-like Thigh domain and two large β-sandwich domains, Calf1 and Calf-2. The β-subunit comprises an n-terminal cysteine-rich PSI (Plexin-Semaphorin-Integrin) domain in which an Ig-like “Hybrid” domain is inserted in its c-terminal loop (the Hybrid domain contains in turn an αA-like domain (βA domain) inserted between its two β-sheets). PSI is followed by four EGF-like domains and a membrane proximal novel tail domain (β-TD). The propeller and βA domains assemble into a “head” structure, which accounts for formation of the αβ heterodimer. Glycosylation sites in the propeller may also contribute to the stability of the heterodimer [16]. The integrin head sits on top of an α and a β “legs”, formed respectively of the Thigh and Calf domains from the αV-subunit and the PSI, Hybrid, EGF1-4 and βTD domains from the β3-subunit. An unexpected feature of the integrin structure is that the legs are bent at both “knees” (located between the Hybrid and Calf-1 domains in αV and between EGF1 and EGF2 in β3). The bent conformation is stabilized primarily by multiple contacts between the upper (PSI-Hybrid-βA, EGF1) and lower (EGF2-4, βTD) leg domains of the β3-subunit. Several contacts of a mixed nature are also present between the largely parallel lower leg domains of αV (Calf domains) and β3 (EGF2-4, βTD).

Figure 1. Crystal Structure of the integrin 〈V®3 ectodomain.

(A) Ribbon diagram of the structure of the unliganded αVβ3 [13]. The protein is bent at a flexible region (genu, arrow), occupied by a metal ion (orange sphere). Four metal ions occupy the base of the propeller (indicated in orange) and an ADMIDAS ion is found in bA (purple sphere). EGF1 and EGF2 are not visible in the structure; their approximate location is indicated. (B) Ribbon diagram of the same structure in complex with the high affinity ligand cRGD [14]; peptide is shown as a ball-and-stick model, with carbons in green, amides in blue and oxygens in red. The specificity-determining loop (SDL) is indicated. Two extra metal ions occupy MIDAS and LIMBS (indicated in the insert). The ectodomain lacks TM segments. Its orientation with respect to a hypothetical membrane approximates the CyoEM structure of full-length aIIbb3 reported by Adair and Yager [31].

The unliganded βA domain is largely superimposible on that of unliganded αA domain but for 2 small insertions between strands BC and DD', that are responsible respectively for its ligand binding specificity (through a specificity determining loop, SDL) and for its association (through a 310 helix) with the propeller domain (Figure 2A). In some integrins, SDL also contributes to heterodimer formation. The βA MIDAS is unoccupied by a metal ion. Adjacent to MIDAS is an ADMIDAS, occupied by a favored Ca2+, which links the top of the activation-sensitive n-terminal α1 helix and the c-terminal F/α7 loop, stabilizing the unliganded state. Five metal ions bind the αV-subunit, one in each of four hairpin loops at the base of the propeller, and a fifth within Calf-1 in close proximity of the α-genu. The βA domain from Pactulous, a neutrophil-specific non metal binding single chain β2-subunit like protein of unknown function, lacks SDL and critical residues in the 310 helix, MIDAS and ADMIDAS, accounting for the inability of this domain to heterodimerize with integrin α-subunits or bind integrin ligands [17].

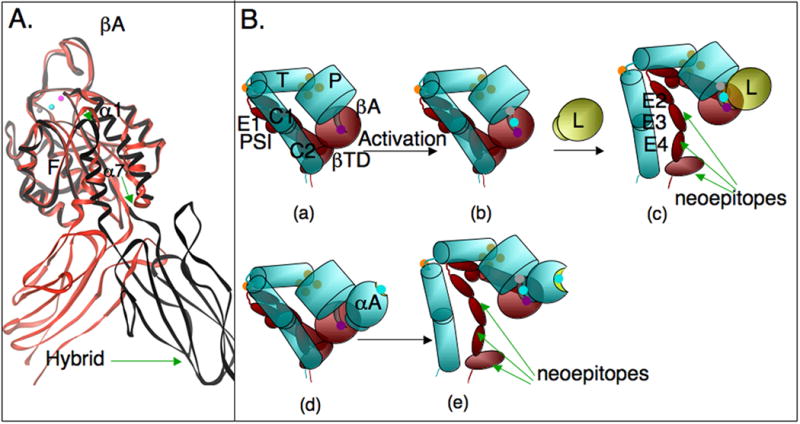

Figure 2. Conformational regulation in integrins.

(A) Conformational differences in two cRGD-bound ®A domains, one (in red) taken from the cRGD-bound 〈V®3 ectodomain (shown in Figure 1B), and the second (in black) from structure of legless αIIb®3 containing the PSI/Hybrid/®A and propeller domains [19]. cRGD is not shown, but the metal ion triplet (ADMIDAS, MIDAS and LIMBS) indicative of the high affinity state are superimposible, consistent with the absence of differences in the 3 surface loops that form the ligand-binding site. The 〈1 helix straightens in association with a further restructuring of the F/α7 loop (arrow head), a one-turn downward movement 〈7 and a large swing-out of the free hybrid domain (green arrows). (B) Conformational effects of the 〈A domain in 〈A-containing integrins on activation. Inside out activation is much more likely to induce expression of extension/swing-sensitive neoepitopes in the absence of extrinsic ligand in 〈A-containing integrins, which contain their own endogenous ligand in 〈A (ligand-relay hypothesis, see text). Inside-out activated 〈A-lacking integrins generally require exogenous ligand to display such epitopes. The common domains in 〈A-lacking- (a-c) and containing (d-e) integrins are schematically reproduced to scale from the ribbon diagrams shown in Figure 1. P, propeller domain; T, Thigh domain, C1,C2, Calf domains 1 and 2; EGF-like domains 1-4 are labeled, E1-4. The 〈A domain in the lower panel is a schematic, in which the inactive 〈A (with a shallow MIDAS occupied by a metal ion, cyan sphere, d) is not engaged with low affinity ®A (depicted with an ADMIDAS only metal ions, purple, d). Activation (depicted by the triple metal in ®A, b, e) rapidly engages the covalently bound 〈A ligand, exposing hidden eiptopes (e), the nature of which depends on the degree of ligand-induced extension (deadbolt model). Exogenous ligand (L, yellow sphere) would be required to produce similar changes in αA-lacking integrins (b, c). These differences likely impact dynamic interaction under flow.

Crystal structure of the integrin ectodomain in complex with ligands

The structure of liganded αVβ3 ectodomain was determined after diffusing the high affinity cyclic pentapeptide, cilengitide, which contains the prototypical Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD), into preformed integrin crystals in the presence of 5 mM Mn2+. RGD inserts into a crevice between the propeller and βA domains, with the R and D side chains exclusively contacting the propeller and βA domains, respectively, and bringing these two domains closer together [14]. The ligand D contacts a metal ion occupied MIDAS in a strikingly similar manner to that previously found in αA.

The activating inward movement of α1 helix and rearrangement of the F/α7 loop seen in liganded αA are also observed in liganded βA, leading to similar although much less dramatic changes in the three surface loops coordinating MIDAS and the SDL loop. Metal coordination at ADMIDAS changes significantly, such that it no longer locks the α1 helix to the F/α7 loop, allowing the activating movements in both. The restructuring of the F/α7 loop is associated with loss of contact between an invariant Asn339 at the top of the α7 helix and the F/α7 loop residue Ser334, which may explain the activating effect of an Asn339Ala mutation in β2 and β3 integrins [18]. The inward movement of α1 carrier ADMIDAS with it, moving it closer to MIDAS, thus helping stabilize the new metal ion at MIDAS. A third MIDAS ion stabilizing site, LIMBS (ligand-associated metal binding site) is found 6Å away, in the liganded structure. The downward two-helical turn of the α7 helix observed in the liganded αA is not present in the liganded βA bent structure. However, in the crystal structure of RGD-bound αIIbβ3 head, from which the leg domains (Thigh/Calf1-2 and EGF1-4/βTD domains) were truncated [19], a one-helical turn downward of the α7 helix is observed, associated with a large outward displacement of the Hybrid domain relative to βA, separating the integrin knees by ∼70Å (Figure 2A).

Rearranging the F/α7 loop with artificial disulphides designed to link the F/α7 loop residue M335 to the F-strand residue V332, or deletion of one turn from α7, independent of the position of the deletion, produced high affinity integrins [20,21]. The choice of M335 and V332 were based on a modeled high affinity βA conformation in which the predicted Cα distances between these two residues is ∼3.4Å, compared to ∼10Å in unliganded and liganded bent structures. However this inter-Cα distance remained ∼10Å (in fact increasing to a Cε-CG2 distance of 13Å) in the high affinity legless αIIbβ3 structure [19], suggesting that the generated high affinity state is caused by unknown tertiary changes. Thus, absent direct structural data, deductions from the impact of artificial disulphides on protein conformation should be made with caution. Of note also is that the tertiary change produced did not constitutively express genuextension-sensitive epitopes in the respective full-length integrin; Mn2+ plus ligand were required [20]. Similar findings were found in αLβ2, in which αA is stabilized in the high affinity state [22].

Models of inside-out integrin activation

The interpretation of the above structural and biochemical findings continue to be the subject of lively debate [8]. By analogy with high affinity αA state, a “switchblade” model proposed that the head structure with the large (∼80°) Hybrid swing-out represents the high affinity state of βA (although the high affinity state in aA is characterized by a 2-helical turn movement vs. one in βA; a downward one-helical turn in αA led to an intermediate affinity state). Constraints by the folded leg domains in the bent ligand-occupied structure must have prevented the Hybrid swing-out needed to pull the α7 helix down and switch βA to high affinity. To provide the necessary space for the Hybrid swing-out, the model suggests that the integrin should first fully extend its knees, converting the bent into a linear asymmetric conformation, described as such in 2D EM images [23]. Full genuextension also relieves the steric hindrance by the plasma membrane expected in the bent conformation. An alternate model, the deadbolt [24], incorporates structural features in βA that are lacking in αA (absence of a metal ion in MIDAS in the unliganded state, presence of an ADMIDAS that strategically links the conformationally-sensitive α1 helix and F/α7 loop, and proximity of the novel βTD to the βA and Hybrid domains), unaccounted for in the switchblade model, to suggest that elastic deformation of the F/α7 loop is possible with only modest quaternary changes at the βTD interface with βA and possibly Hybrid domains. This movement disrupts ADMIDAS, triggering the activating changes in α1 helix and F/α7 loop, in the absence of a one-turn downward movement of α7. The bound ligand provides the energy for the Hybrid swing out, which may be associated with various degrees of genuextension that may be linked to the magnitude and nature of the outside-in mechanochemcial signals generated. Thus, although Hybrid swings and knee-jerk responses are acknowledged conformational changes in both models, they are considered necessary for activation in the switchblade model but a feature of outside-in signaling in the deadbolt model. Experimental evidence in support of the deadbolt model including derivation of the 3D EM structure of the bent ectodomain stably bound to a physiologic ligand (see below) have been reviewed [8]. Interruption of the βTD/βA contact was activating in a β2-integrin [25], but not in a β3-integrin [26]. Differences in the relative contribution of the βTD contact with βA (van der Waals contact in β3) and Hybrid domains may account in part for these differences (the βTD/βA interface in the inactive state is likely more robust in β2 vs. β3, caused by the longer contacting loop in β2). Further structural analysis will be required to evaluate the activating roles of these contacts in other integrins.

Impact of the αA domain on conformational activation

The crystal structure of an αA-containing integrin has not been determined to accurately position αA in the integrin head- the αA domain is inserted between blades 2 and 3 of the propeller domain on the same face that interacts with the βA domain. We have proposed that αA acts as an endogenous ligand for βA: an invariant Glu at the flexible c-terminus of the α7 helix could coordinate the MIDAS metal in the βA domain, when αA is in the open high affinity state. In this “ligand-relay” model [27], active βA can drive the conformational equilibrium of αA in favor of the high affinity state, which can then bind exogenous ligands through its own MIDAS (Figure 2B). Extensive biochemical studies now support this model [8]. High-affinity αA-containing integrins, generated by activating mutations within the βA domain or by the activating metal ion Mn2+ have been shown in many studies (see for example [18,21]), to express genuextension- and Hybrid swing-out sensitive epitopes in the absence of physiologic ligand. These findings led to the development of the switchblade model, based largely on studies in αA-containing integrins. However, αA-lacking integrins with activating βA domain mutations express such epitopes only in the presence of physiologic ligand. The ligand-relay model offers perhaps the correct explanation for these findings. The high affinity βA in αA-containing integrins will rapidly be occupied by the covalently linked αA ligand, and thus express swing-out/extension epitopes, consistent with the deadbolt model. Therefore, introduction of an αA domain in a subgroup of integrins, in addition to providing the respective integrins with the capacity to preferentially recognize glutamate rather than aspartate residues in integrin-binding ligands [7], it also predisposes this subgroup to more readily assume extended conformations in response to inside-out activation in the absence of extrinsic physiologic ligand (Figure 2B).

Electron microscopy (EM) of negatively stained ectodomain and full-length integrins

Transmission EM and single particle image analysis combined with molecular modeling or tomography have been used to investigate the structures of negative-stained unliganded and fibronectin-bound integrin ectodomains [28-30] alone or in complex with extension-sensitive monoclonal antibodies (mAb) [23], and of frozen-hydrated full-length integrins [31]. Initial biophysical studies of the αVβ3 ectodomain using gel filtration yielded a calculated stokes radius of 57Å in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+, a metal ion known to stabilize several membrane-bound integrins in their low affinity state and which has been used to generate the structure of unliganded bent αVβ3 [14]. Exchanging 1mM Mn2+ for Ca2+ increased the Stokes radius to 60Å and further to 64Å by the addition of high affinity c-RGD, leading to the conclusion that ligand and Mn2+-induce a jack-knife genu-linear conformation.

Assessment of negative-stain EM of two-dimensional (2D) averaged projections of manually selected particles identified bent (in Ca2+) and reportedly linear (in Mn2+) forms of the ectodomain, leading the conclusion that Mn2+-induces a jack-knife genuextension, that could account for the observed increase in Stokes radius. In the presence of cRGD, a greater proportion of the linear form was observed even in Ca2+. A follow up random conical tilt study imaged the structure of manually selected images representing the negative-stained α5β1 head that also contains the upper leg domains (Thigh, Hybrid and PSI), at two tilt angles [29]. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction showed that the Hybrid domain assumed the same acute angle relative to βA found in the unliganded bent X-ray structure in the presence of either Ca2+ or Mn2+, demonstrating that the acute angle observe din the full ectodomain is not caused by head-leg contacts. In the presence of c-RGD ligand, an ∼80° swing-out of the Hybrid domain relative to βA was observed, demonstrating that the Hybrid swing-out is induced or stabilized by ligand. These findings were extended in an electron tomography study of manually selected negatively-stained detergent-extracted full-length human αIIbβ3 bound to RGD peptide and imaged at 23 tilt angles. This study also revealed Hybrid domain swing-out in an extended integrin conformation, although it was not possible to determine if the conformation is linear, since the averages do not display density for the leg domains [32]. 2D projections of negative-stained ectodomains from αA-lacking- or containing integrins showed images consistent with at least three conformations: a bent state and reportedly linear states without or with the Hybrid swing-out [23]. Two extension-sensitive mAbs bound to the lower β-leg domains of the linear conformation, irrespective of whether the Hybrid domain was swung in or out, showing that the genu and Hybrid movements are not sequentially linked. Inspection of the published 2D images of integrin ectodomains [23,28], shows that it is difficult to confirm linearity, in part due to the lack of clearly visible density corresponding to several leg domains.

3D particle reconstruction of negatively-stained αVβ3 ectodomain in its unliganded state (in 1mM Ca2+) and bound stably to a five-domain fibronectin III ligand in solution (in 0.2mM Mn2+), revealed that both structures assume a compact state; only a minority of particles assumed a more extended form. This compact conformation closely resembled the bent X-ray structure, enabling molecular docking, with a moderate 11±4° swing-out of the hybrid domain. Vogel's group have used stressed molecular dynamic analysis of αVβ3 to model what happens when force is applied at the integrin ligand-binding site when bound by the fibronectin III 10 domain [33]. The model suggests that a hybrid swing-out does occur as a result of changes in the α1 and α7 helices of the βA domain, but that this swing is only some 20°, yet sufficient to transition the integrin head to the high-affinity conformation, consistent with the above study.

The finding that the bent conformation stably binds physiologic ligand is not consistent with the 2D imaging studies of complete ectodomains or detergent-extracted full-length liganded integrin presented above. The lower Mn2+ concentration used to form the complex, sample and model bias and use of a single angle to visualize particles were main arguments used to dispel these positive findings [34]. The concentration of Mn2+ used was sufficient however to form a stable ectodomain-ligand complex in solution, an accepted definition of the integrin high affinity state. Sample bias was excluded by using an automated selection routine, in addition to the manual selection used exclusively in the studies imaging complete ectodomains or full-length structures [23,28,32]. Model bias was inferred from the failure to observe density in the β-genu in the unliganded state (the β-genu was not included in the search model). Failure to observe known density is found in multiple techniques, however and could reflect flexibility. For instance, the density for fibronectin III 9 domain is missing in 3D images of legless α5β1 [29], and several leg domains were not visible in the tomography study [32]. The β-genu becomes visible in fibronectin-bound state [30], despite use of the same search model, suggesting that ligand binding stabilizes this region. We have also tried to bias the data sets, collected by the automatic particle selection routine, using the genu-linear model [13]; still, none of the views resembled the linear integrin conformation. Further, we also subjected a set of particles subjected to model-free alignment, classification, and averaging using SPIDER, with identical results. Third, we imaged the particles at a single angle, since their random orientation on the carbon grid provided complete coverage of the Euler angles, with no tilting required. 3D image reconstruction proceeded by a projection-matching algorithm, which is typical where particles are randomly oriented. In contrast, the random conical reconstruction algorithm works best where the particles have a preferred orientation on the grid. In the final analysis, the significance of the 3D study by Adair et al [30] is that a bent conformation can bind stably to physiologic ligand in solution, inviting alternate models to knee-jerk extension to explain induction of a stable ligand-competent (high affinity) state. The difficulty in assessing structures of large conformationally-rich modular proteins from manual selection of sets of 2D images, where differences could be due to particles with different structures or different orientations, suggests that a further 3D reconstruction analysis step of imaged particles may well be a requirement in such cases.

CryoEM and biophysical studies of full-length integrin αIIbβ3

Of note is that the conformations deduced from negative-stained integrins resemble only broadly the 3D 20-Å structure of unliganded full-length αIIbβ3 derived by electron cryomicroscopy and single particle image reconstruction [31]. In the cryoEM structure, the integrin head appears to be readily accessible to bind ligand, and is not sterically-hindered by the plasma membrane as commonly depicted in drawings in which the Calf-2 domain is perpendicular to the plane of the plasma membrane. It remains to be determined if some of the multiple conformations described from 2D images of negatively-stained complete ectodomains and full-length integrins are artifacts induced by drying or the non-physiologic solutions used, as has been recently observed in the head domains of myosin filaments [35]. Alternatively, the presence of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains may limit the conformational space in full-length integrins.

Additional information on the structural changes in high affinity integrins has been emerging from biophysical techniques such as FRET using a small integrin ligand as donor and lipophilic membrane-inserted probe as acceptor [36,37]. For α4β1, the distance of closest approach between membrane-to-ligand binding site was ∼50Å between resting and Mn2+- or reducing agent-activated integrins, and 25Å between resting and chemokine-activated integrins. As the theoretical fully extended length of the integrin is > 200Å [13], it is hard to explain this distance in terms of a jack-knife linearized conformation-even if native integrins do not emerge orthogonally from the membrane [31]. These findings support earlier studies showing that mAbs to head and leg domains of platelet integrin αIIbβ3 continue to cross-compete even after platelets are activated with saturating concentrations of various agonists known to switch the integrin into high affinity [38]. A recent visualization of αIIbβ3 using atomic force microscopy hints at what may in the future be achieved in analyzing structure and dynamic changes in native integrins [39].

Structures of cytoskeletal proteins in complex with integrin cytoplasmic tails

Integrins are often on cells subjected to mechanical stress, e.g. in muscle, or endothelial cells under flow conditions, and such stress is known to have profound effects on cell behaviour and phenotype [40]. The short integrin cytoplasmic tails play a key role in switching the ectodomain to the ligand-competent state, then translate conformational changes in the ligand-bound receptor into mechanical and biochemical signals, through interactions with cytoskeletal, adaptor and signaling proteins. The process of integrin activation and signalling through the cytoplasmic domains, has gained more definition in the past years, as details of the structures of the cytoskeletal proteins talin1 [41,42], tensin [43], vinculin [44-46], α-actinin [47,48] and filamin [49] have been determined, together with some of their interactions with the integrin cytoplasmic domains, and with one another [47,50].

Structural basis of inside-out integrin activation-role of talin

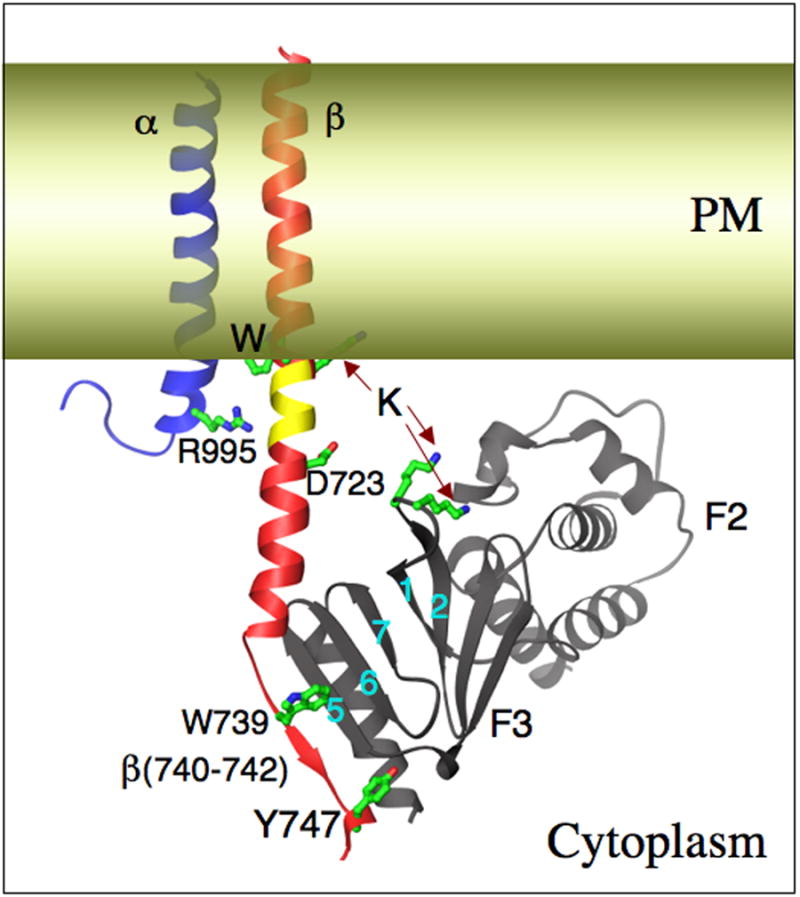

The actin-binding protein talin plays essential roles in inside-out integrin activation [51], early coupling of extracellular ligand-bound integrins to the cytoskeleton [52], and in reinforcing the integrin-cytoskeleton linkage through recruitment of other proteins such as paxillin, vinculin, α-actinin, tensin and zyxin [53]. Talin is found very early together with high affinity integrins in short-lived focal adhesion complexes at the tips of protruding lamellepodia, before other cytoskeletal proteins are detected [3]. Talin is Recruitment of talin to the plasma membrane to the vicinity of target integrins takes place in part through an association with RIAM, a target of the small G-protein Rap1; Rap1 itself is activated by PKC or Rap1-GEF and is recruited to the plasma membrane in response to chemokine or growth factor receptor activation [54,55]. RIAM, PIP2 [56], calpain [57] among others, unmask the integrin-binding site in the trilobed FERM (4.1, ezrin, radixin and moeisin) domain in the talin head. The structure of the phosphotyrosine-binding (PTD)-like β-sandwich F3 lobe of FERM with the cytoplasmic tail of the integrin β3-tail has been determined [41,42]. An NPxY motif of β3 forms a reverse turn, with tyrosine (747 in β3) inserting into a hydrophobic pocket in F3, an interaction stabilized by a tryptophan (W739 in β3). Residues upstream of NPxY form a β-strand that augments the S5-7 β-sheet from talin F3 [41](Figure 3). F3 also makes a second hydrophobic interaction upstream with the α-helical membrane-proximal segment of cytoplasmic β3, which faces β-strands S1-2 and S6-7 of the F3 lobe. Lysine residues in the flexible S1-S2 loop of F3 are predicted to contact the cytosolic surface of the plasma membrane (Figure 3). Modeling the structure of F3/cytoplasmic β3 complex on a previous NMR structure of cytoplasmic αIIb/β3 complex [58], suggests that this second membrane proximal engagement by talin F3 disrupts a salt bridge between the cytosolic tails (R995 and D723, Figure 3) [59], which normally stabilizes the inactive state, providing a kinetic pathway for inside-out activation. Consistent with these findings are mutagenesis studies [42] and loss of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between α/β cytoplasmic tails fused to CFP and YFP at their c-termini [60]. The extent of cytoplasmic tail separation necessary to induce inside-out integrin activation is unclear however. Although >100Å separation has been proposed in the FRET study, altered orientation of the tails and/or the presence of at least the trilobed FERM domain of talin could interrupt FRET without actual separation. The new structure also explains the inability of other PTB domains that interact with the NPxY motif but not the membrane proximal helix of β3-tail to activate integrins.

Figure 3. Integrin activation by talin.

The talin F2 and F3 domains, the latter in complex with an integrin ®3 cytoplasmic tail peptide [42]. Key interactions observed or proposed are shown (see text fro details). F3 engages the NPxY-containing membrane distal part of β3-tail (in red), which becomes ordered. A second interaction with the cytosolic membrane-proximal helix disrupts the stabilizing R995-D723 salt-bridge (in inactive integrins), pulls an intramembranous segment (indicated in yellow) into the cytoplasm, aided perhaps by proposed electrostatic interactions between F3 and the acidic lipid head groups in the lipid bilayer (in yellow). The net result is a shortening of the TM segment, which likely disrupts intramembranous α/β packing, leading to activation of the ectodomain.

The PTB domain from the actin-binding protein tensin binds the β-tail in a talin-like manner, but with lower affinity; the positively charged tyrosine pocket, explains why the interaction is indifferent to tyrosine phosphorylation [43]. The recruitment of tensin is critical in formation of fibrillar adhesions [2]. Crystal structure of the Ig-like 21 domain (IgFLN21) from the actin cross-linking homodimer filamin 1, in complex with integrin β-tail, reveals that the ser/thr-rich membrane distal segment of the β-tail forms an extended β-strand that interacts with strands C and D of IgFLN21. The binding interface extends to the NPxY binding site for talin head [49], precluding the simultaneous binding of both talin and filamin to the β-tail from the same integrin. This competition for binding by filamin may negatively-regulate talin-induced integrin activation, and may explain the known inhibitory role of filamin on cell migration [61].

Formation and transformation of focal contacts

While F3 binding to the integrin proximal β3-tail is sufficient to switch the ectodomain into the ligand-competent state, it does not mediate integrin linkage to the cytoskeleton at focal complexes [62]; a second interaction between the rod domain of talin, formed of multiple amphipathic helical bundles, and ligand-occupied integrin β-tails appears necessary [63]. The structural basis of this integrin-talin rod interaction is unknown; multivalent ligand and force applied on the early matrix-integrin-talin complexes by Rho-activated actomyosin motors may expose a binding-site in the β3-tail for the talin rod [52,64]. The adapter protein paxillin, which is incorporated together with talin in early focal complexes, may link talin to the integrin α-cytoplasmic tail (see below), enhancing resistance of matrix-integrin-talin complexes to mechanical stress [65]. This may explain why paxillin is often found in slow moving membrane protrusions.

The talin- and actin binding protein vinculin and the focal adhesion tyrosine kinase FAK are incorporated next into focal adhesion complexes, strengthening the ECM-cytoskeleton contacts across the integrin. Cryptic vinculin binding sites (VBS) exposed in the talin rod [46] in cooperation with talin-bound actin [66], activate vinculin by destabilizing its autoinhibitory head-tail intramolecular interaction [67]. Co-crystal and NMR structures of talin-derived VBS peptides in complex with the D1 (Vh1) helical bundle subdomain of the vinculin head show the α-helical VBS inserting and replacing helix 1 of D1 [50,68]. Increasing force, exerted at the adhesion site by actomyosin contractility, likely exposes more talin VBSs (up to 11 sites), leading to more vinculin recruitment. The vinculin tail domain also interacts with paxillin leucine-rich LD motifs [69]. Both interactions likely contribute to the conversion of focal complexes into focal adhesions. FAK plays an important role in signaling networks at focal contacts [70]. It is recruited to ECM-bound integrins through interaction of its c-terminal four-helical bundle FAT domain with paxillin LD motifs [71,72]. FAK also binds, through the F1 lobe in its n-terminal FERM domain, with the integrin β-tail, an interaction that destabilizes the autoinhibitory state, thus accessing FAK to activation by Src [73]. This interaction has not been structurally characterized. FAK is also involved in recruiting the adaptor protein p130Cas, a primary mechanical force sensor [74](see below).

Recruitment of the actin-bundling homodimer α-actinin is a later event in formation of focal adhesions [3,75]. A cryoEM study suggests that the region between the spectrin-like α-actinin R1 and R2 repeats in the central α-actinin domain (consisting of four tandem triple-helical bundle repeats) interacts with the proximal helical integrin β-tail already complexed with the talin head, presumably by engaging the opposite side of the β-tail helix [76]. Mechanical stress exerted by integrin ligation transmitted to the R4 repeat of α-actinin, likely swings out helix 3 from the triple-helical bundle. The now accessible helix inserts into the vinculin D1 subdomain in a similar manner to talin, but with an inverted orientation relative to talin, eliciting distinct activating structural changes in vinculin [47,68]. Recruitment of zyxin, through a biochemically- but not structurally defined n-terminal interaction with R2/3 repeats of α-actinin [77] enhances Arp2/3-independent actin assembly in focal adhesions through interactions with Ena/VASP family of proteins [78].

a-integrin-cytoskeleton interactions

The integrin α-cytoplasmic tail is not a passive player in integrin activation or signaling. An interaction between talin and the αIIb cytoplasmic tail has been described [79], but remains structurally uncharacterized. Further, at least one cytosolic protein, the EF-hand containing calcium and integrin binding protein 1 (CIB1) interacts with hydrophobic residues in the membrane-proximal region of αIIb cytoplasmic tail [80], and interferes with talin binding to an αIIb tail peptide [81], thus potentially acting as a negative regulator of talin-induced integrin activation. The α4- (and α9)-subunits of ligand-occupied integrins also enhance integrin-cytoskeleton links formed under shear force [65], by indirectly binding to talin through the cytoskeleton adaptor paxillin. The structures of paxillin in complex with talin or the integrin α4-tail have not been determined. The α4-paxillin interaction is inhibited by phosphorylation of the α4-tail at the leading edge by type I PKA, which is anchored to the α4 tail [82]. This releases paxillin-mediated inhibition of Rac, thus allowing vectorial formation of lamellepodia [83]. Association of the a second Rap1 effector, RAPL, with the αL (CD11a) cytoplasmic tail may act cooperatively with, or perhaps independently of, talin bound to the β2-tail to activate and cluster integrins [84]. Integrin clustering also induces activation of the T cell protein-tyrosine phosphatase (TCPTP) through its association with the integrin α1 cytoplasmic tail; TCPTP-mediated dephosphorylation of the EGF receptor associated with integrin clusters inhibits anchorage-independent cell proliferation [85].

Force sensing and transmission at focal adhesions

Detailed velocity maps for F-actin, α-actinin, integrin, talin, vinculin, zyxin, paxillin and paxillin-binding kinase FAK (focal adhesion kinase) in migrating cells have been developed using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy to capture high-resolution high contrast images of fluorescent-tagged focal adhesion protein clusters in the lamellar region at the base of protruding lamellepodia [86,87]. Both studies find that actin filaments undergo vigorous retrograde movement as a result of continuous pulling by myosin II, while the ECM-bound integrins remain largely stationary. The efficiency of motion transmission from F-actin to proteins within focal adhesions decreased from actin-binding proteins to focal adhesion core proteins (FAK, paxillin, zyxin) to integrin. The actin-binding proteins α-actinin displayed the highest coupling to F-actin motion, consistent with its late incorporation into focal adhesions. Talin/vinculin were only partial coupled to F-actin motion, identifying these as a site of slippage clutch in the F-actin/integrin link, consistent with previous studies [52,53]. Thus, loose connectivity of talin/vinculin with F-actin prevents force produced by actomyosin contraction to be transmitted to the ECM through integrins, while stronger associations with F-actin allows force to be transmitted across integrins to the ECM. Extracellular force applied on the bound integrins would also promote tighter coupling of integrins to F-actin motion, through bound talin-vinculin. The impact of force on matrix-integrin bond dynamics has been reviewed recently [88].

New findings have identified the cytoskeleton protein p130Cas as a primary sensor and transducer of externally applied force into biochemical signals [74]. Cas has an n-terminal SH3 domain that binds FAK (which may link it to the integrin β-tail and/or α-tail through paxillin), a central Cas substrate domain and a c-terminal Src binding domain. Mechanical extension of the central domain in vitro greatly enhanced its phosphorylation by Src, without a change in Src activity. The stretched Cas substrate domain was detected at sites of high traction in vivo using a conformation-sensitive antibody. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Cas associates with Crk and C3G, leading to Rap1 activation and ERK signaling [89]. The linkage of Cas to the integrin through FAK suggests that only very modest extensions of the Cas substrate domain are sufficient to convert mechanical force into biochemical signals.

Outside-in signaling

The short integrin cytoplasmic tails lack enzymatic activity, and so depend on recruitment of adaptor molecules and signaling proteins for effector functions [2]. A prominent biochemical event in integrin outside-in signaling is protein tyrosine phosphorylation due to activation of Src and FAK family protein tyrosine kinases [52,64,90,91]. Src and its inhibitory Csk are constitutively bound to the integrin β-tails: Src through its SH3 domain to the β-tail c-terminus. Integrin binding to ligand induces Src activation, through Csk dissociation, Src transphosphorylation (in clustered integrins) and/or recruitment of tyrosine phosphatases (e.g. receptor tyrosine phosphatase RPTPα, or PTP-1B [91,92]. Syk kinases, which are involved in inducing Rac-dependent lamellepodia formation, are recruited to clustered integrins by direct interaction of its SH2 domain with the integrin β-tail c-terminus and are activated by Src within seconds after integrin-fibrinogen interaction in platelets [93]. Src-induced phosphorylation of the NPxY motif dissociates ligand-bound integrin β-tails from the talin F3 lobe [94]. The released talin head may recruit and activate phosphatidylinositol (4) phosphate 5 kinase type Iγ(PIPKIγ)[95-97], generating PIP2 which coactivate a number of focal adhesion proteins, including vinculin and talin. The released liganded integrins may further activate Syk in focal complexes, or bind tensin, converting focal- into fibrillar adhesions. Src phosphorylation of FAK activates this important signaling and scaffold protein, and its phosphorylation of p130Cas is essential in converting mechanical force into biochemical signals [74]. Extracellular ligand-bound integrins recruit Shp2, which down-regulates FAK thus permitting the late incorporation of α-actinin into focal adhesions [98]. The ser/thr kinase ILK binds directly to and may phosphorylate integrin β1- and β3-tails [99]. Ser/thr phosphorylation of the integrin β-tail impairs its binding to filamin but not to talin, consistent with the respective structures [42,49], an act that may favor cell motility.

Ligand-bound integrins also actively suppress the activation of other integrins in the same cell [100] utilizing different signalling pathways: PKA to suppress α5β1 and αVβ3, when α2β1 is ligated, but PKCα to suppress α2β1, when α5β1 is ligated. This trans-inhibitory mechanism may regulate cellular responses to complex extracellular matrices. The spatiotemporal and structural basis of the interaction of integrin cytoplasmic-tails with the growing list of signaling molecules including cytosolic and receptor kinases (Src, FAK, Syk, ILK and PKC) and phosphatases [101] remains to be determined.

Bidirectional signal traffic across integrin TM domains- the missing link

The integrin α and β TM domains are 25–29 amino acids long, 3-5 residues longer than typical TM domains of type I membrane proteins. They also contain a conserved Trp-Lys/Arg dipeptide, which could provide an alternate cytoplasmic anchor, producing α and β TM domains of typical length by placing an apolar 4-5 residue α-helical segment within the cytoplasm (colored yellow in Figure 3). Glycosylation studies provided experimental support for the long and short integrin TM domains [102], and mutagenesis studies showed that mutations that shorten the TM domains are uniformly activating [103]. The apolar 4-5 residue α-helical segment is predicted to become cytoplasmic as a result of the second interaction of the talin head with the membrane-proximal integrin β-tail (Figure 3). Thus it appears that the α/β TM segments of inactive integrins are long, tilted and in contact, stabilized by electrostatic as well as hydrophobic interactions between the α- and β- cytoplasmic tails immediately adjacent to the plasma membrane. Talin binding disrupts this α /β tail ‘clasp’, and pulls the apolar helical segment into the cytoplasm, leading to tail (and TM) separation, shortened TM domains and inside-out integrin activation (reviewed in [8]. Remarkably, Vinogradova et al [104], proposed, based on NMR studies with isolated α and β peptides in liposomes, that talin binding activates by pushing the membrane-proximal α/β helices into the lipid bilayer, which now seems an unlikely scenario based on the new β3-tail/talin head structure [42].

Adair and Yeager proposed [31], and Gottschalk and Kessler [105-107] modeled an interaction within the integrin α/β TM helices, that confined integrins into a low affinity configuration. These predictions were supported by both directed and non-selective mutation analysis [103,108]. A recent pharmacological approach has also shown that perturbing the intramembranous helix-helix contact can prime integrin αIIbβ3 [109]. It is still unclear how this separation of intramembranous helices in the native heterodimer mechanically translates to conformational change beyond the extracellular membrane surface. Since the TM domains mediate both inside-out activation and outside-in signaling, it is likely that different structural changes in addition to TM separation may be needed to channel distinctly different signals and outcomes. These may include associations with other transmembrane adaptors or signaling proteins, including formation of integrin homo-multimers [110]. Much work is still needed to elucidate the structural basis of integrin signal transmission across the plasma membrane.

Conclusions and perspective

It has long been a major challenge to build supramolecular structures that account for the myriad mechanochemcial interactions taking place at the matrix-integrin-cytoskeleton interface in living cells. Bit by bit, however, the molecular players involved are beginning to take shape, the mechanics of force and biochemical signal transmission being placed in structural contexts, and new techniques are continuously being developed to image these dynamic interactions. This task will continue to be complicated by the modular nature of the large proteins involved and the long list of potential interactions revealed by biochemical and domain analysis: Many focal adhesion proteins appear to have multiple binding partners, acting at different times and locations, with their affinity for one over another being regulated by phosphorylation or other signals. Given the pace of the progress made in the past few years, one is optimistic that the above goal will eventually be achieved, with important implications for biology, material science and human health.

Acknowledgments

Work from the authors' laboratories was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

• • of outstanding interest

- 1.Hynes RO. Integrins: a family of cell surface receptors. Cell. 1987;48:549–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix--cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:793–805. doi: 10.1038/35099066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaidel-Bar R, Ballestrem C, Kam Z, Geiger B. Early molecular events in the assembly of matrix adhesions at the leading edge of migrating cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4605–4613. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel V, Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michishita M, Videm V, Arnaout MA. A novel divalent cation-binding site in the A domain of the beta 2 integrin CR3 (CD11b/CD18) is essential for ligand binding. Cell. 1993;72:857–867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90575-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JO, Bankston LA, Arnaout MA, Liddington RC. Two conformations of the integrin A-domain (I-domain): a pathway for activation? Structure. 1995;3:1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JO, Rieu P, Arnaout MA, Liddington R. Crystal structure of the A domain from the alpha subunit of integrin CR3 (CD11b/CD18) Cell. 1995;80:631–638. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnaout MA, Mahalingam B, Xiong JP. Integrin Structure, Allostery, And Bidirectional Signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:381–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li R, Rieu P, Griffith DL, Scott D, Arnaout MA. Two functional states of the CD11b A-domain: correlations with key features of two Mn2+-complexed crystal structures. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1523–1534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong JP, Li R, Essafi M, Stehle T, Arnaout MA. An isoleucine-based allosteric switch controls affinity and shape shifting in integrin CD11b A-domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38762–38767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huth JR, Olejniczak ET, Mendoza R, Liang H, Harris EA, Lupher ML, Jr, Wilson AE, Fesik SW, Staunton DE. NMR and mutagenesis evidence for an I domain allosteric site that regulates lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 ligand binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5231–5236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimaoka M, Xiao T, Liu JH, Yang Y, Dong Y, Jun CD, McCormack A, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Takagi J, et al. Structures of the alphaL I Domain and Its Complex with ICAM-1 Reveal a Shape-Shifting Pathway for Integrin Regulation. Cell. 2003;112:99–111. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Diefenbach B, Zhang R, Dunker R, Scott DL, Joachimiak A, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3. Science. 2001;294:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.1064535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Frech M, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3 in complex with an Arg-Gly-Asp ligand. Science. 2002;296:151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. A Novel Adaptation of the Integrin PSI Domain Revealed from Its Crystal Structure. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40252–40254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isaji T, Sato Y, Zhao Y, Miyoshi E, Wada Y, Taniguchi N, Gu J. N-glycosylation of the beta-propeller domain of the integrin alpha5 subunit is essential for alpha5beta1 heterodimerization, expression on the cell surface, and its biological function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33258–33267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Specific glycosylation sites on α5β1 that regulate dimerization and transport.

- 17.Sen M, Legge GB. Pactolus I-domain: Functional switching of the Rossmann fold. Proteins. 2007;68:626–635. doi: 10.1002/prot.21458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng M, Foo SY, Shi ML, Tang RH, Kong LS, Law SK, Tan SM. Mutation of a Conserved Asparagine in the I-like Domain Promotes Constitutively Active Integrins {alpha}Lbeta2 and {alpha}IIbbeta3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18225–18232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao T, Takagi J, Coller BS, Wang JH, Springer TA. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo BH, Takagi J, Springer TA. Locking the beta3 integrin I-like domain into high and low affinity conformations with disulfides. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10215–10221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang W, Shimaoka M, Chen J, Springer TA. Activation of integrin beta-subunit I-like domains by one-turn C-terminal alpha-helix deletions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2333–2338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu C, Shimaoka M, Zang Q, Takagi J, Springer TA. Locking in alternate conformations of the integrin alphaLbeta2 I domain with disulfide bonds reveals functional relationships among integrin domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2393–2398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041618598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishida N, Xie C, Shimaoka M, Cheng Y, Walz T, Springer TA. Activation of Leukocyte beta(2) Integrins by Conversion from Bent to Extended Conformations. Immunity. 2006;25:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. New insights into the structural basis of integrin activation. Blood. 2003;102:1155–1159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta V, Gylling A, Alonso JL, Sugimori T, Ianakiev P, Xiong JP, Arnaout MA. The {beta}-tail domain ({beta}TD) regulates physiologic ligand binding to integrin CD11b/CD18. Blood. 2006 doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-056689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu J, Boylan B, Luo BH, Newman PJ, Springer TA. Tests of the extension and deadbolt models of integrin activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11914–11920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700249200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso JL, Essafi M, Xiong JP, Stehle T, Arnaout MA. Does the integrin alphaA domain act as a ligand for its betaA domain? Curr Biol. 2002;12:R340–342. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 2002;110:599–511. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takagi J, Strokovich K, Springer TA, Walz T. Structure of integrin alpha5beta1 in complex with fibronectin. EMBO J. 2003;22:4607–4615. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adair BD, Xiong JP, Maddock C, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA, Yeager M. Three-dimensional EM structure of the ectodomain of integrin {alpha}V{beta}3 in a complex with fibronectin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:1109–1118. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Recombinant extracellular domains of avb3 as crystallized (Ref 13) remains bent when bound to a macromolecular fibronectin fragment. But an increase in angle of 11± 4 degrees between the hybrid and βA domain is seen.

- 31.Adair BD, Yeager M. Three-dimensional model of the human platelet integrin alpha IIbbeta 3 based on electron cryomicroscopy and x-ray crystallography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14059–14064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212498199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • TEM study revealing that the transmembrane helices of αIIb and β3 pack closely in situ, and that the receptor does not depart the membrane orthogonally. Evidence for a partially bent structure in a context more native than ref. 13.

- 32.Iwasaki K, Mitsuoka K, Fujiyoshi Y, Fujisawa Y, Kikuchi M, Sekiguchi K, Yamada T. Electron tomography reveals diverse conformations of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 in the active state. J Struct Biol. 2005;150:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puklin-Faucher E, Gao M, Schulten K, Vogel V. How the headpiece hinge angle is opened: new insights into the dynamics of integrin activation. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:349–360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • • Thoughtful molecular dynamics study under stressed and relaxed conditions of αVβ3. When liganded FN III 10 is modeled onto the structure and “pulled”, using the 1JV2 and 1LG5 PDB structures as basis, the α1 helix on the beta domain undergoes a small inward movement, and the “hinge” between beta and hybrid swings some 20 degrees. The group concludes that this is sufficient movement for activation, and supports the whole molecule data obtained in ref. 30, while questioning the use of bilaterally amputated integrins in structural studies.

- 34.Luo BH, Springer TA. Integrin structures and conformational signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig R, Woodhead JL. Structure and function of myosin filaments. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chigaev A, Buranda T, Dwyer DC, Prossnitz ER, Sklar LA. FRET detection of cellular alpha4-integrin conformational activation. Biophys J. 2003;85:3951–3962. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chigaev A, Waller A, Zwartz GJ, Buranda T, Sklar LA. Regulation of cell adhesion by affinity and conformational unbending of alpha4beta1 integrin. J Immunol. 2007;178:6828–6839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This and the next paper use FRET between a lipophilic membrane acceptor and an a4b1 mimetic to shows a change in distance between integrin head and membrane: inactive-to-active 2.5 nm to 7.5 nm – ie. shorter than the combined length of the calf domains. Although this is apparently incompatible with a change from a “folded” to fully “extended” structures, it is a signal-averaging technique, and so equivocal. Interestingly, the FRET signal, and hence the mean distance of binding site from membrane does not change when the receptor affinity is increased using PMA.

- 38.Calzada MJ, Alvarez MV, Gonzalez-Rodriguez J. Agonist-specific structural rearrangements of integrin alpha IIbbeta 3. Confirmation of the bent conformation in platelets at rest and after activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39899–39908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205886200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hussain MA, Agnihotri A, Siedlecki CA. AFM imaging of ligand binding to platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3 receptors reconstituted into planar lipid bilayers. Langmuir. 2005;21:6979–6986. doi: 10.1021/la046943h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • An initial effort to using new technologies.

- 40.Ingber DE. Mechanosensation through integrins: cells act locally but think globally. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1472–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530201100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Alvarez B, de Pereda JM, Calderwood DA, Ulmer TS, Critchley D, Campbell ID, Ginsberg MH, Liddington RC. Structural determinants of integrin recognition by talin. Mol Cell. 2003;11:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wegener KL, Partridge AW, Han J, Pickford AR, Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH, Campbell ID. Structural basis of integrin activation by talin. Cell. 2007;128:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • • Elegant description of the interaction of talin with the β3 cytoplasmic domain.

- 43.McCleverty CJ, Lin DC, Liddington RC. Structure of the PTB domain of tensin1 and a model for its recruitment to fibrillar adhesions. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1223–1229. doi: 10.1110/ps.072798707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bakolitsa C, Cohen DM, Bankston LA, Bobkov AA, Cadwell GW, Jennings L, Critchley DR, Craig SW, Liddington RC. Structural basis for vinculin activation at sites of cell adhesion. Nature. 2004;430:583–586. doi: 10.1038/nature02610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borgon RA, Vonrhein C, Bricogne G, Bois PR, Izard T. Crystal structure of human vinculin. Structure. 2004;12:1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gingras AR, Vogel KP, Steinhoff HJ, Ziegler WH, Patel B, Emsley J, Critchley DR, Roberts GC, Barsukov IL. Structural and dynamic characterization of a vinculin binding site in the talin rod. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1805–1817. doi: 10.1021/bi052136l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bois PR, Borgon RA, Vonrhein C, Izard T. Structural dynamics of alpha-actinin-vinculin interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6112–6122. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.14.6112-6122.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 48.Kelly DF, Taylor DW, Bakolitsa C, Bobkov AA, Bankston L, Liddington RC, Taylor KA. Structure of the alpha-actinin-vinculin head domain complex determined by cryo-electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiema T, Lad Y, Jiang P, Oxley CL, Baldassarre M, Wegener KL, Campbell ID, Ylanne J, Calderwood DA. The molecular basis of filamin binding to integrins and competition with talin. Mol Cell. 2006;21:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • • A second elegant study from Cambell and Calderwood, showing that filamin interaction (with β7 cytoplasmic domain) has different structural consequences from talin interaction. The binding sites partially overlap, and the authors show biochemically that they compete. This reveals a new mechanism of integrin-cytoskeletal regulation.

- 50.Izard T, Evans G, Borgon RA, Rush CL, Bricogne G, Bois PR. Vinculin activation by talin through helical bundle conversion. Nature. 2004;427:171–175. doi: 10.1038/nature02281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, Ginsberg MH, Calderwood DA. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang G, Giannone G, Critchley DR, Fukumoto E, Sheetz MP. Two-piconewton slip bond between fibronectin and the cytoskeleton depends on talin. Nature. 2003;424:334–337. doi: 10.1038/nature01805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giannone G, Jiang G, Sutton DH, Critchley DR, Sheetz MP. Talin1 is critical for force-dependent reinforcement of initial integrin-cytoskeleton bonds but not tyrosine kinase activation. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:409–419. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lafuente EM, van Puijenbroek AA, Krause M, Carman CV, Freeman GJ, Berezovskaya A, Constantine E, Springer TA, Gertler FB, Boussiotis VA. RIAM, an Ena/VASP and Profilin ligand, interacts with Rap1-GTP and mediates Rap1-induced adhesion. Dev Cell. 2004;7:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han J, Lim CJ, Watanabe N, Soriani A, Ratnikov B, Calderwood DA, Puzon-McLaughlin W, Lafuente EM, Boussiotis VA, Shattil SJ, et al. Reconstructing and deconstructing agonist-induced activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1796–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martel V, Racaud-Sultan C, Dupe S, Marie C, Paulhe F, Galmiche A, Block MR, Albiges-Rizo C. Conformation, localization, and integrin binding of talin depend on its interaction with phosphoinositides. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21217–21227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan B, Calderwood DA, Yaspan B, Ginsberg MH. Calpain cleavage promotes talin binding to the beta 3 integrin cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28164–28170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vinogradova O, Velyvis A, Velyviene A, Hu B, Haas T, Plow E, Qin J. A structural mechanism of integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3) “inside-out” activation as regulated by its cytoplasmic face. Cell. 2002;110:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hughes PE, Diaz-Gonzalez F, Leong L, Wu C, McDonald JA, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Breaking the Integrin Hinge. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6571–6574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim M, Carman CV, Springer TA. Bidirectional transmembrane signaling by cytoplasmic domain separation in integrins. Science. 2003;301:1720–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1084174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calderwood DA, Huttenlocher A, Kiosses WB, Rose DM, Woodside DG, Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Increased filamin binding to beta-integrin cytoplasmic domains inhibits cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1060–1068. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanentzapf G, Brown NH. An interaction between integrin and the talin FERM domain mediates integrin activation but not linkage to the cytoskeleton. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:601–606. doi: 10.1038/ncb1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moes M, Rodius S, Coleman SJ, Monkley SJ, Goormaghtigh E, Tremuth L, Kox C, van der Holst PP, Critchley DR, Kieffer N. The integrin binding site 2 (IBS2) in the talin rod domain is essential for linking integrin beta subunits to the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17280–17288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The sites in the talin tail revealed, which after binding of the talin head domain regulate propagation of the ECM-cytoskeleton signaling path.

- 64.Cluzel C, Saltel F, Lussi J, Paulhe F, Imhof BA, Wehrle-Haller B. The mechanisms and dynamics of (alpha)v(beta)3 integrin clustering in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:383–392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alon R, Feigelson SW, Manevich E, Rose DM, Schmitz J, Overby DR, Winter E, Grabovsky V, Shinder V, Matthews BD, et al. Alpha4beta1-dependent adhesion strengthening under mechanical strain is regulated by paxillin association with the alpha4-cytoplasmic domain. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:1073–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen H, Choudhury DM, Craig SW. Coincidence of actin filaments and talin is required to activate vinculin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40389–40398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bois PR, O'Hara BP, Nietlispach D, Kirkpatrick J, Izard T. The vinculin binding sites of talin and alpha-actinin are sufficient to activate vinculin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:7228–7236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fillingham I, Gingras AR, Papagrigoriou E, Patel B, Emsley J, Critchley DR, Roberts GC, Barsukov IL. A vinculin binding domain from the talin rod unfolds to form a complex with the vinculin head. Structure. 2005;13:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown MC, Turner CE. Paxillin: adapting to change. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1315–1339. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arold ST, Hoellerer MK, Noble ME. The structural basis of localization and signaling by the focal adhesion targeting domain. Structure. 2002;10:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00717-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayashi I, Vuori K, Liddington RC. The focal adhesion targeting (FAT) region of focal adhesion kinase is a four-helix bundle that binds paxillin. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nsb755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lietha D, Cai X, Ceccarelli DF, Li Y, Schaller MD, Eck MJ. Structural basis for the autoinhibition of focal adhesion kinase. Cell. 2007;129:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sawada Y, Tamada M, Dubin-Thaler BJ, Cherniavskaya O, Sakai R, Tanaka S, Sheetz MP. Force sensing by mechanical extension of the Src family kinase substrate p130Cas. Cell. 2006;127:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • • A nice study that idetifies p130Cas as a primary sensor and transducer of force at focal adhesions.

- 75.Laukaitis CM, Webb DJ, Donais K, Horwitz AF. Differential dynamics of alpha 5 integrin, paxillin, and alpha-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1427–1440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kelly DF, Taylor KA. Identification of the beta1-integrin binding site on alpha-actinin by cryoelectron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2005;149:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li B, Trueb B. Analysis of the alpha-actinin/zyxin interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33328–33335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fradelizi J, Noireaux V, Plastino J, Menichi B, Louvard D, Sykes C, Golsteyn RM, Friederich E. ActA and human zyxin harbour Arp2/3-independent actin-polymerization activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:699–707. doi: 10.1038/35087009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knezevic I, Leisner TM, Lam SC. Direct binding of the platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3 (GPIIb-IIIa) to talin. Evidence that interaction is mediated through the cytoplasmic domains of both alphaIIb and beta3. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16416–16421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamniuk AP, Ishida H, Vogel HJ. The interaction between calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1 and the alphaIIb integrin cytoplasmic domain involves a novel C-terminal displacement mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26455–26464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuan W, Leisner TM, McFadden AW, Wang Z, Larson MK, Clark S, Boudignon-Proudhon C, Lam SC, Parise LV. CIB1 is an endogenous inhibitor of agonist-induced integrin alphaIIbbeta3 activation. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:169–175. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lim CJ, Han J, Yousefi N, Ma Y, Amieux PS, McKnight GS, Taylor SS, Ginsberg MH. Alpha4 integrins are type I cAMP-dependent protein kinase-anchoring proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:415–421. doi: 10.1038/ncb1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nishiya N, Kiosses WB, Han J, Ginsberg MH. An alpha4 integrin-paxillin-Arf-GAP complex restricts Rac activation to the leading edge of migrating cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:343–352. doi: 10.1038/ncb1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katagiri K, Maeda A, Shimonaka M, Kinashi T. RAPL, a Rap1-binding molecule that mediates Rap1-induced adhesion through spatial regulation of LFA-1. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mattila E, Pellinen T, Nevo J, Vuoriluoto K, Arjonen A, Ivaska J. Negative regulation of EGFR signalling through integrin-alpha1beta1-mediated activation of protein tyrosine phosphatase TCPTP. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:78–85. doi: 10.1038/ncb1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brown CM, Hebert B, Kolin DL, Zareno J, Whitmore L, Horwitz AR, Wiseman PW. Probing the integrin-actin linkage using high-resolution protein velocity mapping. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:5204–5214. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • • This study and the one by Hu et al (ref 87) reveal the power of new methodologies in examining motion of structural and regulatory focal-adhesion proteins with actomyosin motors at focal adhesions in live cells.

- 87.Hu K, Ji L, Applegate KT, Danuser G, Waterman-Storer CM. Differential transmission of actin motion within focal adhesions. Science. 2007;315:111–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1135085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Evans EA, Calderwood DA. Forces and bond dynamics in cell adhesion. Science. 2007;316:1148–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1137592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Defilippi P, Di Stefano P, Cabodi S. p130Cas: a versatile scaffold in signaling networks. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Sarkar S, Brugge JS, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Src kinase activation by direct interaction with the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13298–13302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336149100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arias-Salgado EG, Lizano S, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Specification of the direction of adhesive signaling by the integrin beta cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29699–29707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.von Wichert G, Jiang G, Kostic A, De Vos K, Sap J, Sheetz MP. RPTP-alpha acts as a transducer of mechanical force on alphav/beta3-integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:143–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Woodside DG, Obergfell A, Leng L, Wilsbacher JL, Miranti CK, Brugge JS, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Activation of Syk protein tyrosine kinase through interaction with integrin beta cytoplasmic domains. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1799–1804. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ling K, Doughman RL, Iyer VV, Firestone AJ, Bairstow SF, Mosher DF, Schaller MD, Anderson RA. Tyrosine phosphorylation of type Igamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase by Src regulates an integrin-talin switch. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1339–1349. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Pereda JM, Wegener KL, Santelli E, Bate N, Ginsberg MH, Critchley DR, Campbell ID, Liddington RC. Structural basis for phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase type Igamma binding to talin at focal adhesions. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8381–8386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413180200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lee SY, Voronov S, Letinic K, Nairn AC, Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Regulation of the interaction between PIPKI gamma and talin by proline-directed protein kinases. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:789–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ling K, Doughman RL, Firestone AJ, Bunce MW, Anderson RA. Type I gamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase targets and regulates focal adhesions. Nature. 2002;420:89–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.von Wichert G, Haimovich B, Feng GS, Sheetz MP. Force-dependent integrin-cytoskeleton linkage formation requires downregulation of focal complex dynamics by Shp2. Embo J. 2003;22:5023–5035. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Legate KR, Montanez E, Kudlacek O, Fassler R. ILK, PINCH and parvin: the tIPP of integrin signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:20–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Orr AW, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ, Deckmyn H, Schwartz MA. Matrix-specific suppression of integrin activation in shear stress signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4686–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Revealing study, which explains how ligation of one integrin can suppress the activation of others: different pathways are activated involving PKA when α2β1 activation suppresses avb3, and PKCα when a5b1 .suppresses α2β1.

- 101.Ginsberg MH, Partridge A, Shattil SJ. Integrin regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stefansson A, Armulik A, Nilsson I, von Heijne G, Johansson S. Determination of N- and C-terminal borders of the transmembrane domain of integrin subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21200–21205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Partridge AW, Liu S, Kim S, Bowie JU, Ginsberg MH. Transmembrane domain helix packing stabilizes integrin alpha IIbbeta 3 in the low affinity state. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vinogradova O, Vaynberg J, Kong X, Haas TA, Plow EF, Qin J. Membrane-mediated structural transitions at the cytoplasmic face during integrin activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4094–4099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400742101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gottschalk KE. A coiled-coil structure of the alphaIIbbeta3 integrin transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains in its resting state. Structure. 2005;13:703–712. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gottschalk KE, Kessler H. A computational model of transmembrane integrin clustering. Structure. 2004;12:1109–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gottschalk KE, Kessler H. Evidence for hetero-association of transmembrane helices of integrins. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:253–258. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luo BH, Carman CV, Takagi J, Springer TA. Disrupting integrin transmembrane domain heterodimerization increases ligand binding affinity, not valency or clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3679–3684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409440102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yin H, Slusky JS, Berger BW, Walters RS, Vilaire G, Litvinov RI, Lear JD, Caputo GA, Bennett JS, DeGrado WF. Computational design of peptides that target transmembrane helices. Science. 2007;315:1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.1136782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • • An intriguing new pharmacological approach to structural and functional analysis of protein transmembrane domains.

- 110.Li R, Mitra N, Gratkowski H, Vilaire G, Litvinov R, Nagasami C, Weisel JW, Lear JD, DeGrado WF, Bennett JS. Activation of integrin alphaIIbbeta3 by modulation of transmembrane helix associations. Science. 2003;300:795–798. doi: 10.1126/science.1079441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]