Abstract

The onset and progression of cancer is associated with the methylation-dependent silencing of specific genes, however, the mechanism and its regulation have not been established. We previously demonstrated that reduction of mitochondrial DNA content induces cancer progression. Here we found that mitochondrial DNA-deficient LNρ0-8 activates the hypermethylation of the nuclear DNA promoters including the promoter CpG islands of the endothelin B receptor, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, and E-cadherin. These are unmethylated and the corresponding gene products are expressed in the parental LNCaP containing mitochondrial DNA. The absence of mitochondrial DNA induced DNA methyltransferase 1 expression which was responsible for the methylation patterns observed. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase eliminated hypermethylation and expressed gene products in LNρ0-8. These studies demonstrate loss or reduction of mitochondrial DNA resulted in the induction of DNA methyltransferase 1, hypermethylation of the promoters of endothelin B receptor, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, and E-cadherin and reduction of the corresponding gene products.

Keywords: mitochondrial DNA, CpG island hypermethylation, cancer progression, prostate cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a significant health problem, representing the most diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in North American men [1]. It is known that epigenetic changes, defined as heritable changes in gene expression that occur without changes in DNA sequence, contribute to malignant transformation and progression of prostate cancer [2]. One type of epigenetic aberration is DNA methylation (addition of a methyl group to the 5-carbon of cytosine in CpG sequences) which is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT). Alterations in DNA methylation levels can lead to chromosomal instability and transcriptional gene silencing and have been implicated in a variety of human malignancies, including prostate cancer [3]. The role of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and mitochondrial respiratory activity on biological functions, including apoptosis, have been investigated with the use of mtDNA-deficient (ρ0) cells [4]. These mtDNA deficient cell lines are established by long-term exposure to low concentrations of ethidium bromide [5]. We showed evidence that mtDNA depletion determines androgen dependence and induced more progressed cancer [6]. In this study, we examined the relationship between mtDNA, the regulation of selected gene expression and their pattern of methylation. We used an early-stage prostate cancer cell line (LNCaP) to derive mtDNA-depleted cells, mtDNA-reduced cells, and mtDNA-recovered cells and investigated the methylation status of CpG islands within promoters of endothelin B receptor (EDNRB), E-cadherin (CDH1), and O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT). We chose these genes because hypermethylation of the promoter CpG islands of these genes was induced in advanced form of cancer [7-9] but not in the early-stage prostate cancer, such as in LNCaP. Our results indicated that mtDNA content determines the CpG island hypermethylation pattern of the key cancer markers EDNRB, CDH-1, and MGMT and therefore identifies mtDNA as a key epigenetic factor affecting changes in prostate cancer progression.

Materials and Methods

Materials and cell culture

Details of materials cell culture methods are provided in Supplementary information.

Genomic DNA extraction and methylation analysis

Details of Genomic DNA extraction and methylation analysis methods are provided in Supplementary information.

Western blotting

Details of western blotting methods are provided in Supplementary information.

Determination of mtDNA copy number using real-time quantitative PCR

Details of determination of mtDNA copy number using real-time quantitative PCR are provided in Supplementary information.

Amplification of whole mtDNA at the single-cell level

Details of Amplification of whole mtDNA at the single-cell level are provided in Supplementary information.

Results

Depleting mtDNA Induces Promoter CpG island Hypermethylation

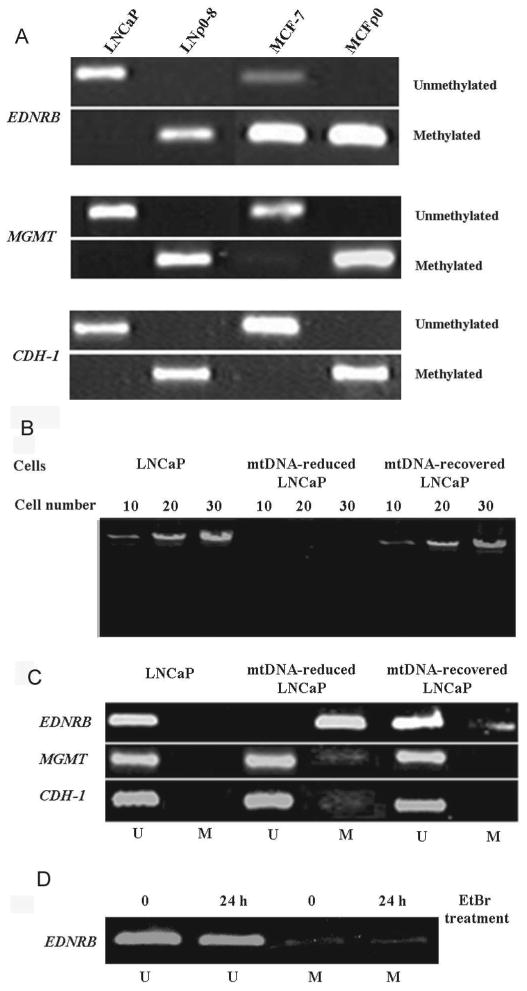

We first investigated whether depletion of mtDNA induces promoter CpG island hypermethylation in LNρ0-8. This cell line lacks mtDNA and was established from early-stage human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP[6]. The methylation status of the target genes (i.e., EDNRB, CDH1, and MGMT) was analyzed using the methylation-specific PCR (MSP) technique. We observed that the EDNRB promoter CpG island in LNρ0-8 cells was completely methylated, yet in LNCaP cells this island was unmethylated (Fig. 1A). We also examined the effects of mtDNA depletion on the methylation status of the target genes in human breast cancer cell line MCF-7. The mtDNA-deficient MCFρ0 cells were established by continuously treating MCF-7 cells with low concentrations of ethidium bromide (EtBr) which is the general method to investigate the effect of mtDNA depletion [10]. The EDNRB promoter CpG island in MCFρ0 cells was strongly methylated, while that in MCF-7 cells was partially unmethylated. Thus like the LNCaP cells, depletion of mtDNA in breast cancer cell line MCF-7 also increased hypermethylation of the EDNRB promoter CpG island.

Fig. 1.

Methylation status of EDNRB, MGMT, and CDH-1 in mtDNA-deficient cells, mtDNA reduced cells and mtDNA recovered cells. (A) Methylation status of CPG islands in EDNRB, MGMT and CDH-1 genes in LNCaP, LNρ0-8, MCF-7, and MCFρ0 cell lines was assayed by MSP. (B-D) LNCaP cells were treated with EtBr (200 ng/ml) for 10 days, resulting in mtDNA-reduced LNCaP cells. EtBr was removed and cells were cultured for another 14 days, resulting in mtDNA-recovered LNCaP cells. (B) mtDNA content was analyzed by nested long-range PCR. (C) Methylation status of EDNRB, MGMT, and CDH-1 was assayed by MSP. (D) LNCaP cells were treated with EtBr (200 ng/ml) for 24h and methylation status of EDNRB, was assayed by MSP.

The influence of mtDNA content on the methylation patterns of other target genes revealed a very similar pattern of methylation activity. MtDNA depletion induced hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands in MGMT and CDH-1. These promoter CpG islands were hypermethylated in both cell lines lacking mtDNA but unmethylated in parental LNCaP and MCF-7 cell lines (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that mtDNA depletion has a profound influence on the methylation of regulatory elements and defines a consistent pattern among the EDNRB, MGMT, and CDH-1 promoters in prostate and breast cancer cell lines.

MtDNA Reduction Induces Promoter CpG island Hypermethylation

To determine whether mtDNA reduction can induce hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands, we reduced then recovered mtDNA by treating cells by adding then removing EtBr from the medium and then investigated the effects of mtDNA content on hypermethylation of promoter CpG island methylation. Treating LNCaP cells with EtBr for 10 days greatly reduced mtDNA content, as detected by long-range PCR (mtDNA-reduced LNCaP, Fig. 1B). When the cells were further cultured in the absence of EtBr for 14 days, they recovered their mtDNA content (mtDNA-recovered LNCaP, Fig. 1B).

The promoter methylation pattern correlated with mtDNA content in line with the earlier observations (Fig. 1C). Promoter CpG islands of EDNRB, MGMT, and CDH-1 were not methylated (U) in control LNCaP cells. EtBr treatment, of the LNCaP cells, shifted EDNRB promoter CpG islands to hypermethylated status. We also observed detectable methylation bands representing the MGMT and CDH-1 promoters in cells harboring reduced mtDNA (mtDNA-reduced LNCaP), although the methylation of these CpG islands was only a fraction of the EDNRB signal. Removal of the EtBr from the LNCaP cells resulted in recovery of mtDNA and a corresponding drop in the methylated EDNRB and the appearance of the unmethylated band. Consistent with this, the methylation bands for MGMT and CDH-1 were eliminated in mtDNA-recovered LNCaP. To exclude the possibility that induction of promoter hypermethylation is not due to the pharmaceutical effect of EtBr, LNCaP cells were treated with EtBr for 24h and tested their effect on hypermethylation of CpG island of promoter of EDNRB. 24 h EtBr treatment did not reduce mtDNA content (Data not shown) and could not increase hypermethylation of promoter of EDNRB (Fig. 1D).

To determine if the methylation patterns observed was a more general response, we examined the effect of mtDNA in other cell lines. Next, we investigated whether hypermethylation of EDNRB promoter CpG islands is associated with mtDNA content in prostate cancer cell lines. We used prostate cancer cell lines LNCaP, C4-2, PC-3, DU145, and LNρ0-8 and mtDNA content of these cell lines are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

mtDNA content in prostate cancer cell lines

| Average of mtDNA | |

|---|---|

| ±SD | |

| Cell lines | (X 104) |

| LNCaP | 8.6±2.6 |

| C4-2 | 4.2±2.0 |

| DU145 | 3.0±1.9 |

| PC-3 | 2.1±1.0 |

| LNρ0-8 | 0 |

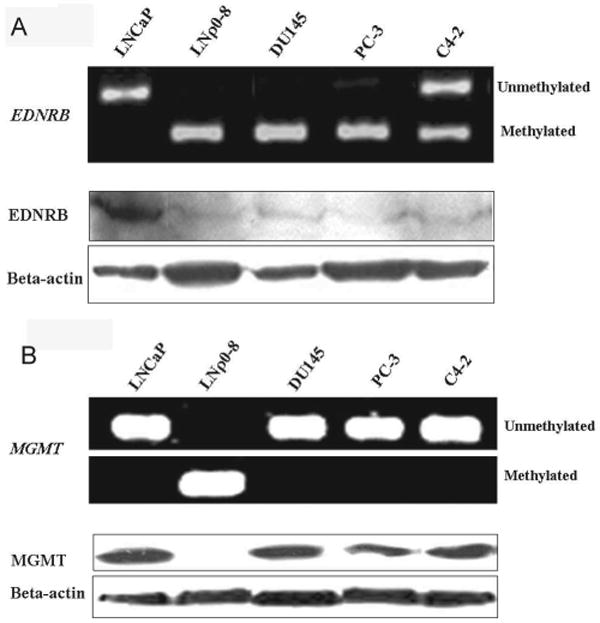

EDNRB promoter CpG islands in LNCaP cells were unmethylated. Half of the EDNRB promoter CpG islands in C4-2 cells were methylated, and half were unmethylated; those in LNρ0-8, DU145, and PC-3 cells were completely methylated (Fig. 3A). Reduced mtDNA in cell lines correlated with induction of methylation of the EDNRB promoter.

Fig. 3.

Effects of DAC on methylation of EDNRB CpG islands and EDNRB protein levels. LNCaP cells were cultured for 72 h with or without DAC (10 μM). (A) Methylation status of EDNRB CPG islands was assayed by MSP. (B) Protein levels of EDNRB were detected by Western blotting; beta-actin was used as a protein loading control.

Examining protein expression of EDNRB in these cell lines revealed that only LNCaP cells expressed detectable EDNRB (Fig. 3A). Expression of EDNRB protein was inversely correlated with promoter CpG islands hypermethylation. Similar analysis revealed that the MGMT promoter CpG islands were hypermethylated only in LNρ0-8 cells and were not methylated in LNCaP, DU145, PC-3, and C4-2 cells (Fig. 3B). Further MGMT was expressed in all four cell lines from the unmethylated MGMT promoters (i.e., LNCaP, DU145, PC-3, and C4-2) (Fig. 3B). The present studies did not attempt to titrate the level of mtDNA levels to determine if the extent of EDNRB expression was more sensitive than expression of the MGMT protein.

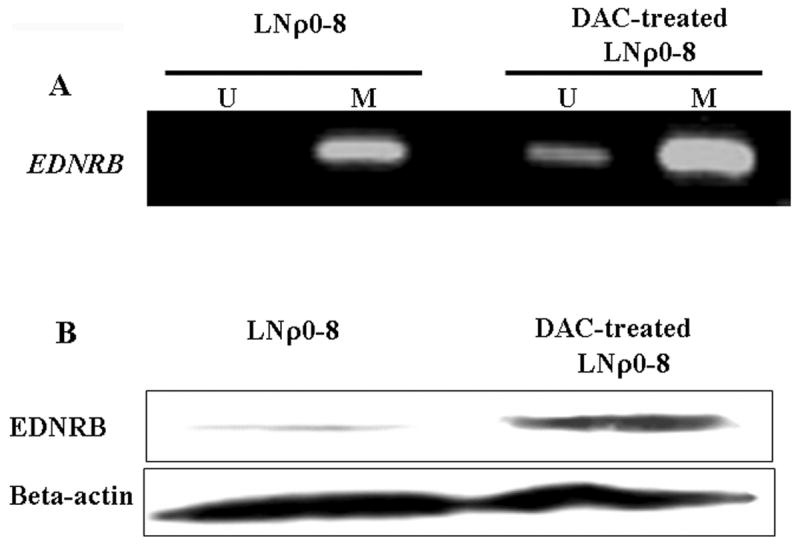

Induction of DNMT1 by mtDNA Depletion Leads to Hypermethylation of Promoter CpG Island

To further characterize the participation of the methyl transferase activity in the response to changes in mtDNA content, we examined the effect of specific inhibitors. 5-azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (DAC) are known to inhibit activity of DNMT (i.e., the enzyme responsible for DNA methylation) and thereby reduce promoter methylation [11]. We treated LNρ0-8 with DAC for 72 hours and used MSP method to examine the methylation status of the EDNRB promoter. DAC treatment caused the appearance of a band representing unmethylated promoter CpG islands (Fig. 4A) and expression of EDNRB protein (Fig. 4B) in LNCaP, indicating that DNMT is involved in promoter hypermethylation and silencing of EDNRB that is induced by reduction of mtDNA content. These data support a model that the loss or reduction of mtDNA leads to an up-regulation of DNMT protein (methyl transferase) and hypermethylation of EDNRB promoter CpG islands.

Fig. 4.

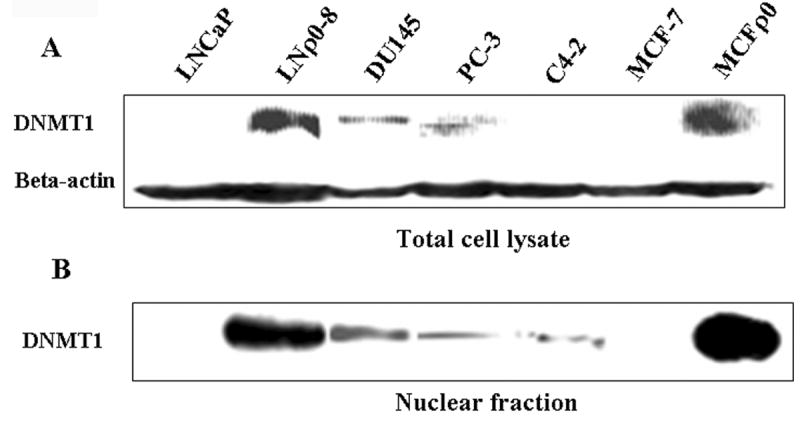

DNMT1 levels in prostate and breast cancer cell lines. DNMT1 protein levels were detected in total cell lysates and nuclear fractions of LNCaP, LNρ0-8, DU145, PC-3, C4-2, MCF-7, and MCFρ0 by Western blotting; beta-actin was used as a protein loading control.

Region-specific hypermethylation and increased levels of DNMT1 expression and activity are associated with the malignant phenotype [12]. Also, the abnormal expression of DNMT1 in murine and human fibroblasts promotes many features of transformation [13]. Therefore, we examined if the expression of DNMT1 in total cell lysates and nuclear extracts of LNCaP, LNρ0-8, DU145, PC-3, C4-2, MCF-7, and MCFρ0 could be measured. In total cell lysates, DNMT1 was not observed in LNCaP, C4-2, or MCF-7 cells; it was slightly but significantly expressed in DU145 and PC-3 cells and highly expressed in LNρ0-8 and MCFρ0 cells. In nuclear extracts, DNMT1 was not detected in LNCaP or MCF-7 cells; it was present in small but significant amounts in DU145, PC-3, and C4-2 cells and in large amounts in LNρ0-8 and MCFρ0 cells. These data provide additional support for cellular events in which the level of mtDNA has a profound impact on the expression of DNMT1 and the subsequent hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands. In the current model, the loss or reduction of mtDNA leads to increased nuclear levels of methyl transferase and hypermethylation of key regulatory elements.

Discussion

Our study provides the first evidence that mtDNA content contributes to regulating hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands. Both of the mtDNA-deficient cell lines (i.e., LNρ0-8 and MCF-ρ0) established from prostate cancer cell line LNCaP and the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 showed increase in the hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands of EDNRB, MGMT, and CDH-1. Overall, a reduction of mtDNA content induced hypermethylation, and recovery of mtDNA reduced hypermethylation. We also demonstrate a direct link between mtDNA reduction, DNMT1 expression, and the hypermethylation of promoter CpG islands. Thus, reduction of mtDNA in prostate and breast cancers may lead to hypermethylation of promoters of genes associated with cancer progression (e.g., EDNRB, CDH1, and MGMT); supporting the idea that mtDNA content may play a significant role in cancer progression.

Silencing of several genes is associated with cancer progression. Endothelin-1 is a vasoactive peptide produced in advanced prostate cancer [14]. Although its role in carcinogenesis is still largely unknown, endothelin B receptor (EDNRB) is silenced in prostate cancer through CpG island methylation [15]. The extent of hypermethylation of the CpG island in EDNRB correlates with the grade and stage of the primary prostate cancer [9]. Also, decreased production of CDH-1, a component of E-cadherin/catenin cell adhesion complex, is associated with poorly differentiated and late-stage prostate cancer and is closely linked to progression [8]. The CDH-1 promoter is hypermethylated in prostate cancer cells and it is likely that hypermethylation accounts for the reduced expression [16]. Finally, the extent of MGMT silencing through CpG island hypermethylation is also associated with the grade or stage of breast cancer [7].

To confirm that mtDNA depletion induced promoter CpG island hypermethylation in LNCaP cells, we performed two sets of experiments. First, we used additional target cells (i.e., breast cancer cell line MCF-7) to evaluate reproducibility of the effect observed in prostate cancer cell lines; induction of promoter CpG island hypermethylation was also observed in breast cancer cell lines. Second, we utilized the system where mtDNA content was reduced (by treatment with EtBr) and followed by a subsequent recovery by removing EtBr [17]. In each of these studies, induction of CpG island hypermethylation reversibly correlated with mtDNA content. These results indicate that mtDNA depletion correlated strongly with hypermethylation of CpG islands in promoters of EDNRB, CDH1, and MGMT.

The androgen-independent human prostate cancer cell line C4-2 was established by inoculation of androgen-dependent LNCaP cells in a castrated mouse [18]. C4-2 cells are androgen-independent, highly tumorigenic, and have a proclivity to metastasize to bone [18]. Other androgen-independent cell lines, such as DU-145 and PC-3, were also utilized [19]. LNCaP is a very early-stage prostate cancer cell line, C4-2 is more progressed, and PC-3 and DU145 are most progressed of those examined. Quantitation of mtDNA revealed that its content in these cell lines varied in the following order: LNCaP>C4-2>DU145>PC-3>LNρ0-8. Thus, these studies indicate that mtDNA reduction is associated with CpG island hypermethylation and predicts that the threshold of mtDNA content needed to induce hypermethylation of the EDNRB promoter, a putative cancer-progression gene, lies between the mtDNA content found in LNCaP cells and that in C4-2 cells.

The CpG island hypermethylation described here is induced by DNMTs. Specific inhibitors of DMNT, such as DAC, block CpG island hypermethylation [11] and restore production of the gene products. As expected, DAC blocked hypermethylation of EDNRB promoter CpG islands, and the treatment also resulted in restored production of EDNRB in LNρ0-8 cells. It is very likely, therefore, that CpG island hypermethylation in LNρ0-8 cells was due to DNMT activity. In mammalian cells, CpG hypermethylation is carried out by three active DNMTs: DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B. DNMT1 mediates replication-coupled maintenance of DNA methylation patterns, whereas DNMT3A and DNMT3B are considered de novo methylases that are critical in the dynamic methylation process [20].

We investigated whether mtDNA depletion induced changes in DNMT1 gene product. DNMT1 expression is associated with the malignant phenotype [12], and the addition of exogenous DNMT1 protein to murine and human fibroblasts promoted many features of transformation [13]; therefore, we investigated whether mtDNA depletion induced changes in DNMT1 production. Our results indicated that mtDNA depletion resulted in increased expression of DNMT1 production and increases in CpG island hypermethylation. Although it has not yet been well studied, DNMT1 expression is regulated through the pRb/E2F [21] and STAT3 pathways [22]. The depletion of mtDNA has been shown to activate NF-κB [23, 24], ERK [25], and AKT [26] pathways.

MtDNA depletion causes the inhibition of functions of mitochondrial respiratory chains (MRC) and reduces membrane potential and inhibition of MRC may be the cause for hypermethylation. We used oligomycin A, an inhibitor of complex V and FCCP, an uncoupler to reduce membrane potential to investigate this. Both of the reagents up to three days induced no change on DNMT1 expression and hypermethylation of EDNRB promoter (data not shown). It took us at least 7 days before we could see EDNRB hypermethylation after ethidium bromide addition but we could not keep cells alive after four days treatment with oligomycin A or FCCP. Therefore, it may be possible that reduction of MRC for a longer period of time might be needed to induce expression of DNMT1. Alternatively, it is still possible that mtDNA depletion itself affect hypermethylation independent of MRC activities. Further investigation will be needed to find out the mechanistic link starting from mtDNA depletion to EDNRB expression.

The replication and transcription of mtDNA is controlled by its D-loop region. Mutations of this region, which are very common in cancer cells [27], result in decreased copy number and repressed gene expression. MtDNA mutations other than those in the D-loop region also result in mtDNA depletion [28] as well as mutations in Nuclear-encoded proteins. A recent report showed that nuclear-encoded p53 associates with and regulates polymeraseγ in mitochondria to regulates mtDNA replication [29]. P53 mutations are very common in cancer cells, so it is likely that p53 mutations disrupt regulation of mtDNA leading to cancer progression. Detection of mtDNA content is potentially an important prognostic tool, and regulation of mtDNA content in cancer therapy may be an important target for preventing cancer progression.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 2.

Methylation status and protein levels of EDNRB (A) and MGMT (B) in prostate cancer cell lines. Methylation status of CPG islands in EDNRB (A) and MGMT (B) in LNCaP, LNρ0-8, DU145, PC-3, and C4-2 were assayed by MSP. Protein levels of EDNRB (A) and MGMT (B) were detected by Western blotting; beta-actin was used as a protein loading control.

Table 2.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions for MSP analysis

| Gene name | Methylation type | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| MGMT | U | TTTTGTGTTTTGATGTTTGTAGGTTTTTGT | AACTCCACACTCTTCCAAAAACAAAACA |

| M | TTTCGACGTTCGTAGGTTTTCGC | GCACTCTTCCGAAAACGAAACG | |

|

| |||

| ENDRB | U | TGGTGAAGAGGTTGTGGGTGGTATTAGTG | ACCTACTCCAAAAACATCCAATAACCA |

| M | CGAAGAGGTTGCGGGCGGTATTAGCG | TACTCCAAAAACGTCCGATAACCG | |

|

| |||

| CDH-1 | U | TAATTTTAGGTTAGAGGGTTATTGT | CACAACCAATCAACAACACA |

| M | TTAGGTTAGAGGGTTATCGCGT | TAACTAAAAATTCACCTACCGAC | |

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Thomas J. Kelly for his advice during preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Mrs. Margaret E. Brenner for reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tobacco Settlement at State of Arkansas and NIH grant CA100846 to MH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li LC, Carroll PR, Dahiya R. Epigenetic changes in prostate cancer: implication for diagnosis and treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:103–115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baylin SB, Makos M, Wu JJ, Yen RW, de Bustros A, Vertino P, Nelkin BD. Abnormal patterns of DNA methylation in human neoplasia: potential consequences for tumor progression. Cancer Cells. 1991;3:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandel NS, Schumacker PT. Cells depleted of mitochondrial DNA (rho0) yield insight into physiological mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:173–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00783-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King MP, Attardi G. Human cells lacking mtDNA: repopulation with exogenous mitochondria by complementation. Science. 1989;246:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.2814477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higuchi M, Kudo T, Suzuki S, Evans TT, Sasaki R, Wada Y, Shirakawa T, Sawyer JR, Gotoh A. Mitochondrial DNA determines androgen dependence in prostate cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2006;25:1437–1445. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munot K, Bell SM, Lane S, Horgan K, Hanby AM, Speirs V. Pattern of expression of genes linked to epigenetic silencing in human breast cancer. Human Pathology. 2006;37:989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul R, Ewing CM, Jarrard DF, Isaacs WB. The cadherin cell-cell adhesion pathway in prostate cancer progression. British Journal of Urology. 1997;1:37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1997.tb00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yegnasubramanian S, Kowalski J, Gonzalgo ML, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, Walsh PC, Bova GS, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG. Hypermethylation of CpG islands in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer. Cancer Research. 2004;64:1975–1986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King MP, Attardi G. Injection of mitochondria into human cells leads to a rapid replacement of the endogenous mitochondrial DNA. Cell. 1988;52:811–819. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90423-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka M, Hibasami H, Nagai J, Ikeda T. Effect of 5-azacytidine on DNA methylation in Ehrlich's ascites tumor cells. Australian Journal of Experimental Biology & Medical Science. 1980;58:391–396. doi: 10.1038/icb.1980.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patra SK, Patra A, Zhao H, Dahiya R. DNA methyltransferase and demethylase in human prostate cancer. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2002;33:163–171. doi: 10.1002/mc.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Issa JP, Herman J, Bassett DE, Jr, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Expression of an exogenous eukaryotic DNA methyltransferase gene induces transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:8891–8895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8891. see comment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirtskhalaishvili G, Nelson JB. Endothelium-derived factors as paracrine mediators of prostate cancer progression. Prostate. 2000;44:77–87. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000615)44:1<77::aid-pros10>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson JB, Lee WH, Nguyen SH, Jarrard DF, Brooks JD, Magnuson SR, Opgenorth TJ, Nelson WG, Bova GS. Methylation of the 5′ CpG island of the endothelin B receptor gene is common in human prostate cancer. Cancer Research. 1997;57:35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graff JR, Herman JG, Lapidus RG, Chopra H, Xu R, Jarrard DF, Isaacs WB, Pitha PM, Davidson NE, Baylin SB. E-cadherin expression is silenced by DNA hypermethylation in human breast and prostate carcinomas. Cancer Research. 1995;55:5195–5199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amuthan G, Biswas G, Zhang SY, Klein-Szanto A, Vijayasarathy C, Avadhani NG. Mitochondria-to-nucleus stress signaling induces phenotypic changes, tumor progression and cell invasion. Embo J. 2001;20:1910–1920. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu HC, Hsieh JT, Gleave ME, Brown NM, Pathak S, Chung LW. Derivation of androgen-independent human LNCaP prostatic cancer cell sublines: role of bone stromal cells. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:406–412. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Culig Z, Klocker H, Eberle J, Kaspar F, Hobisch A, Cronauer MV, Bartsch G. DNA sequence of the androgen receptor in prostatic tumor cell lines and tissue specimens assessed by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Prostate. 1993;22:11–22. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990220103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li E. Chromatin modification and epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3:662–673. doi: 10.1038/nrg887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCabe MT, Davis JN, Day ML. Regulation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by the pRb/E2F1 pathway. Cancer Research. 2005;65:3624–3632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Wang HY, Woetmann A, Raghunath PN, Odum N, Wasik MA. STAT3 induces transcription of the DNA methyltransferase 1 gene (DNMT1) in malignant T lymphocytes. Blood. 2006;108:1058–1064. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-007377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswas G, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Zaidi M, Avadhani NG. Mitochondria to nucleus stress signaling: a distinctive mechanism of NFkappaB/Rel activation through calcineurin-mediated inactivation of IkappaBbeta. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;161:507–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higuchi M, Manna SK, Sasaki R, Aggarwal BB. Regulation of the activation of nuclear factor kappaB by mitochondrial respiratory function: evidence for the reactive oxygen species-dependent and -independent pathways. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2002;4:945–955. doi: 10.1089/152308602762197489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amuthan G, Biswas G, Ananadatheerthavarada HK, Vijayasarathy C, Shephard HM, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial stress-induced calcium signaling, phenotypic changes and invasive behavior in human lung carcinoma A549 cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:7839–7849. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelicano H, Xu RH, Du M, Feng L, Sasaki R, Carew JS, Hu Y, Ramdas L, Hu L, Keating MJ, Zhang W, Plunkett W, Huang P. Mitochondrial respiration defects in cancer cells cause activation of Akt survival pathway through a redox-mediated mechanism. Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;175:913–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512100. see comment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carew JS, Huang P. Mitochondrial defects in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2002;1:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner CJ, Granycome C, Hurst R, Pohler E, Juhola MK, Juhola MI, Jacobs HT, Sutherland L, Holt IJ. Systematic segregation to mutant mitochondrial DNA and accompanying loss of mitochondrial DNA in human NT2 teratocarcinoma Cybrids. Genetics. 2005;170(4):1879–1885. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Achanta G, Sasaki R, Feng L, Carew JS, Lu W, Pelicano H, Keating MJ, Huang P. Novel role of p53 in maintaining mitochondrial genetic stability through interaction with DNA Pol gamma. EMBO Journal. 2005;24:3482–3492. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.