Abstract

An a priori pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) target of 40% daily time above the MIC (T >MIC; based on the MIC90 of 0.06 μg/ml for Streptococcus pyogenes reported in the literature) was shown to be achievable in a phase 1 study of 23 children with a once-daily (QD) modified-release, multiparticulate formulation of amoxicillin (amoxicillin sprinkle). The daily T >MIC achieved with the QD amoxicillin sprinkle formulation was comparable to that achieved with a four-times-daily (QID) penicillin VK suspension. An investigator-blinded, randomized, parallel-group, multicenter study involving 579 children 6 months to 12 years old with acute streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis was then undertaken. Children were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive either the amoxicillin sprinkle (475 mg for ages 6 months to 4 years, 775 mg for ages 5 to 12 years) QD for 7 days or 10 mg/kg of body weight of penicillin VK QID for 10 days (up to the maximum dose of 250 mg QID). Unexpectedly, the rates of bacteriological eradication at the test of cure were 65.3% (132/202) for the amoxicillin sprinkle and 68.0% (132/194) for penicillin VK (95% confidence interval, −12.0% to 6.6%). Thus, neither antibiotic regimen met the minimum criterion of ≥85% eradication ordinarily required by the U.S. FDA for first-line treatment of tonsillopharyngitis due to S. pyogenes. The results of subgroup analyses across demographic characteristics and current infection characteristics and by age/weight categories were consistent with the primary-efficacy result. The clinical cure rates for amoxicillin sprinkle and penicillin VK were 86.1% (216/251) and 91.9% (204/222), respectively (95% confidence interval, −11.6% to −0.4%). The results of a post hoc PD analysis suggested that a requirement for 60% daily T >MIC90 more accurately predicted the observed high failure rates for bacteriologic eradication with the amoxicillin sprinkle and penicillin VK suspension studied. Based on the association between longer treatment courses and maximal bacterial eradication rates reported in the literature, an alternative composite PK/PD target taking into consideration the duration of therapy, or total T >MIC, was considered and provides an alternative explanation for the observed failure rate of amoxicillin sprinkle.

Streptococcus pyogenes accounts for approximately 5% to 10% of all pharyngitis cases in adults and 15% to 30% in children, with a peak incidence of infection in persons 5 to 15 years of age (19). Penicillin has long been the drug of choice for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis (2). Despite the development of resistance among respiratory bacterial pathogens, S. pyogenes remains uniformly sensitive to penicillin and ampicillin (28).

Amoxicillin is an accepted alternative to penicillin for the eradication of S. pyogenes due to its well-established safety, efficacy, and narrow spectrum of activity (2, 35). Amoxicillin is the most commonly prescribed antibiotic for the treatment of pharyngitis in the United States (27). Immediate-release amoxicillin is not approved for once-daily (QD) dosing. Two small studies and one larger, more recently conducted, single-center study have evaluated the efficacy of QD administration of immediate-release amoxicillin suspension for 10 days. Two studies found the efficacy to be equivalent to that of 10 days of penicillin V (three times daily [TID] or four times daily [QID]) (16, 38), and one study found QD amoxicillin noninferior to amoxicillin two times daily (BID) for 10 days (7). Two studies have reported on the use of a shorter course of amoxicillin as a treatment for S. pyogenes tonsillopharyngitis, one in children (8) and one in adults (33). In these studies, immediate-release amoxicillin suspension and tablets administered BID for 6 days were found to be as effective as 10 days of penicillin V administered TID (8, 33). However, limitations in these study designs preclude definitive conclusions.

This paper describes a phase 1 pharmacokinetic (PK) study of children that assessed the single-dose administration of an investigational oral amoxicillin sprinkle designed to sequentially deliver an immediate-release and multiple delayed-release pulses of amoxicillin to provide prolonged plasma concentrations of amoxicillin, thereby enabling QD dosing, relative to the administration of immediate-release amoxicillin. Based on a PK/pharmacodynamics (PD) assessment of this phase 1 data and PK data for an oral penicillin VK suspension in the literature, a clinical trial was completed comparing the amoxicillin sprinkle administered QD for 7 days to penicillin VK QID for 10 days in children with tonsillopharyngitis secondary to S. pyogenes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PD assessment.

Although a daily time above the MIC (T >MIC) target for amoxicillin or penicillin against S. pyogenes has not been clearly defined, a target 40% T >MIC PD endpoint for beta-lactam antibiotics has been established for many drug-microbe combinations (5, 9). Therefore, an a priori PD target of 40% daily T >MIC (assuming a MIC90 of 0.06 μg/ml for S. pyogenes, based on reports in the literature [28]) for unbound drug in plasma (amoxicillin unbound fraction, 82% [47], and penicillin VK unbound fraction, 45% [29]) was selected. PD assessments were made for both dose regimens of amoxicillin sprinkle and for the penicillin VK regimen. PK data from a phase 1 study following a single dose of amoxicillin sprinkle and PK data for penicillin VK from published literature (17) were utilized to calculate the daily T >MIC for the regimens. The phase 1 study used a 475-mg amoxicillin sprinkle under fed conditions for children 6 months to 4 years old or 775 mg under fed and fasted conditions for children 5 to 12 years old with an upper respiratory tract infection.

After the results of the clinical trial were available, daily T >MICs were recalculated using the MIC95 level determined from the results for the baseline S. pyogenes isolates in the clinical trial (0.015 μg/ml) (Table 1). A further PD analysis was then performed which involved fitting the daily T >MIC data for amoxicillin sprinkle from the population of subjects in the above-referenced phase 1 study to a log normal distribution and determining the log normal distribution parameters and 95% confidence intervals (using JMP version 5.0.1a). The cumulative distribution of the fitted T >MIC data was then utilized to determine the projected number of therapeutic failures, using the PD target of 40% daily T >MIC, and comparing this to the actual number of failures observed in the clinical trial. The observed number of subjects failing treatment in the clinical trial was then evaluated in relation to the same cumulative T >MIC distribution to determine the theoretical minimum daily T >MIC required to achieve successful eradication of S. pyogenes (i.e., the efficacy cutoff).

TABLE 1.

Parameters following single-dose administration of amoxicillin sprinkle

| Treatment groupa | PK parameter (unit of measure)b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC(0-t) (μg/hr/ml) | Cmax (μg/ml) | Tmax (hr) | t1/2 (hr) | Kel (1/hr) | |

| A (n = 11) | 39.3 | 8.65 | 2.5 | 1.98 | 0.529 |

| B (n = 12) | 34.4 | 8.93 | 2 | 1.6 | 0.456 |

| C (n = 12) | 34.2 | 10.3 | 1.5 | 1.51 | 0.481 |

Treatment A, 475-mg, single-dose amoxicillin sprinkle in children age 6 months to 4 years in a fed state; treatment B, 775-mg, single-dose amoxicillin sprinkle in children age 5 to 12 years in a fed state; treatment C, 775-mg, single-dose amoxicillin sprinkle in children age 5 to 12 years in a fasted state. For AUC(0-t), t1/2, and Kel, n = 10 for treatment A and n = 11 for treatment B.

Values are arithmetic means, except that those for Tmax are the medians. AUC(0-t), area under the concentration-time curve from 0 to the last timepoint with a measurable drug concentration; Cmax, maximum concentration of drug in serum; Tmax, time to maximum concentration of drug in serum; t1/2, half-life; Kel, elimination rate constant.

Clinical trial design.

This was an investigator-blinded, randomized, parallel-group, multicenter clinical study involving children with acute streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. There were four study visits for bacteriological and/or clinical assessments: visit 1 (day 1) was the screening/baseline visit, visit 2 (days 3 to 5) was the during-therapy visit, visit 3 (days 14 to 18) was the test-of-cure (TOC) visit, and visit 4 (days 38 to 45) was the late posttherapy (LPT) visit.

Patients had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria: (i) written informed consent and assent where appropriate; (ii) an age of ≥6 months to 12 years; (iii) a clinical diagnosis of acute tonsillopharyngitis defined as having sore throat (or presumed sore throat based on apparent dysphagia in children unable to describe symptoms) with at least one of a list of symptoms comprising tonsillar or pharyngeal exudates, tender cervical lymph nodes, fever or history of fever treated with antipyretics, odynophagia, uvular edema, pharyngeal erythema of moderate or greater intensity, elevated white blood cell count of >12,000/mm3 or ≥10% bands, and red tongue and prominent papillae (strawberry tongue); and (iv) a positive rapid-screening test for S. pyogenes (Signify Strep A enzyme immunoassay; Inverness Medical Professional Diagnostics Group, Princeton, NJ). For subjects with a positive rapid-screening test, a second swab that was taken simultaneously with the rapid-screen test swab was sent to the central laboratory for culture confirmation of the presence of S. pyogenes.

Patients with any of the following criteria were excluded: (i) chronic (2-week duration) or recurrent (two times per year) odynophagia or enlarged tonsils secondary to viral or proven bacteriological etiology; (ii) known carrier of S. pyogenes; or (iii) previous allergy to, serious adverse reaction to, or intolerance of penicillin or any other member of the beta-lactam class of antimicrobials.

Treatment administered.

At visit 1, patients who met all the eligibility criteria were randomly assigned using computer-generated random numbers in a 1:1 ratio to receive amoxicillin sprinkle (475 mg QD for ages 6 months to 4 years and 775 mg QD for ages 5 to 12 years) for 7 days or penicillin VK suspension (10 mg/kg of body weight QID, maximum dose 250 mg QID) for 10 days. The investigator (or any of the staff involved with reviewing clinical signs and symptoms) remained blinded to the treatment by having assigned personnel (unblinded study site staff) other than the investigator or staff assess signs and symptoms and dispense and/or collect study medication, as well as perform drug accountability. The patient and his or her parent/guardian were instructed by the unblinded study site staff not to discuss any details about the drug they were taking with the investigator or other blinded staff. No instances of accidental unblinding were noted during the course of the study.

Amoxicillin sprinkle was supplied to the investigators in sachets (475 mg for ages 6 months to 4 years and 775 mg for ages 5 to 12 years) for QD administration on days 1 to 7 inclusive and penicillin VK was supplied as a 125 or 250 mg/5 ml suspension for administration at a dose of 10 mg/kg QID (up to the maximum dose of 250 mg QID) for treatment on days 1 to 10 inclusive. Amoxicillin was to be sprinkled over applesauce or yogurt.

Patients were required to be 100% compliant with taking study medication during the first three days of the study, plus they must have had an overall compliance of at least 80% for the entire treatment course to be included in the per-protocol population analyses. Compliance was assessed by use of a study medication compliance diary and verified by a physical count of the amoxicillin sachets or by volume assessment of the penicillin VK suspension.

Analysis populations.

The four analysis populations used for the statistical analyses and data tabulation are presented here: (i) intent to treat (ITT)/safety, all patients who received at least one dose of study drug and who had at least one postbaseline clinical safety assessment; (ii) modified intent to treat (mITT), all ITT/safety patients with a baseline throat swab culture that was positive for S. pyogenes; (iii) per-protocol clinical (PPc), all ITT/safety patients with either a rapid streptococcus A test at baseline or a baseline throat swab culture that was positive for S. pyogenes, excluding those with major protocol violations and those who did not have a clinical assessment at the TOC visit; and (iv) per-protocol bacteriological (PPb), the primary efficacy population, which consisted of all PPc patients with a baseline throat swab culture positive for S. pyogenes and with throat swab culture results available at the TOC visit. Efficacy results for clinical failures that withdrew early from the study and started a new antimicrobial for tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis due to tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis were included in the PPb analyses.

Efficacy assessments and outcome.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the bacteriological outcome at TOC in the PPb population. Secondary efficacy endpoints included (i) bacteriological outcome at the TOC for the mITT and PPc populations; (ii) bacteriological outcome at the LPT visit for the mITT and PPb populations; (iii) clinical outcome in the ITT/safety, mITT, PPc, and PPb populations at TOC; and (iv) clinical outcome in the ITT/safety and PPc populations at LPT.

A throat culture was obtained at TOC, LPT, and/or early withdrawal to confirm the presence or absence of S. pyogenes. The bacteriological response at the TOC visit was assessed using the following categories: (i) eradication, a negative throat culture for S. pyogenes at the TOC visit, irrespective of the clinical response at TOC, and no new antimicrobial therapy was started before the culture was obtained at the TOC visit; (ii) failure, a throat culture that was positive for S. pyogenes at the TOC visit, irrespective of the clinical response; and (iii) presumed failure, no culture results available at the TOC visit, but a new antimicrobial was started for tonsillopharyngitis before the TOC visit.

The bacteriological response at the LPT visit was assessed using the following categories: (i) eradication, a negative throat culture for S. pyogenes at the TOC visit and a negative throat culture for S. pyogenes at LPT or no culture result at LPT but patient was a clinical cure at the LPT visit; (ii) failure, a throat culture that was positive for S. pyogenes at TOC regardless of the outcome at LPT; (iii) secondary failure, eradication at TOC but a throat culture that was positive for S. pyogenes with the same streptococcal strain at the LPT visit (carrier/recolonization); (iv) new infection, eradication at TOC but a culture that was positive for S. pyogenes with a different streptococcal strain at the LPT visit; and (v) presumed failure, no culture results at LPT visit but antibacterial therapy administered between the TOC and LPT visits for the treatment of tonsillopharyngitis.

Clinical assessments were conducted at each study visit. The investigator documented the presence or absence of the following signs and symptoms of tonsillopharyngitis: sore throat, odynophagia, fever or history of fever, chills, strawberry tongue, uvular edema, pharyngeal erythema, pharyngeal exudates, cervical lymphadenopathy (enlargement of the periauricular, submandibular, submental, anterior and/or posterior cervical lymph nodes), and tender lymph nodes. In addition, if the sign/symptom was present, the investigator assessed the intensity as mild (except for pharyngeal erythema), moderate (except for chills), or severe, with the exception of sore throat, strawberry tongue, and pharyngeal exudates, which were assessed as either present or absent according to definitions provided.

Based on the evaluation of the signs and symptoms of tonsillopharyngitis, the clinical response at the TOC and LPT visits was assessed using the following categories. (i) Cure was defined as the resolution of baseline clinical signs/symptoms and no appearance of new signs/symptoms at the TOC visit and no further antimicrobial therapy required for tonsillopharyngitis. A response of cure at LPT visit required a cure at TOC, continued resolution of baseline clinical signs/symptoms, no appearance of new signs/symptoms at the LPT visit, and no further antimicrobial therapy required for tonsillopharyngitis. (ii) Failure was defined as the persistence of baseline clinical signs/symptoms, including the appearance of new signs/symptoms or progression of the infection requiring additional antimicrobial therapy or a change in treatment regimen at the TOC visit. At the LPT visit, failure was defined as failure at TOC or the occurrence of signs/symptoms of a new infection that required the initiation of new antimicrobial therapy for the indication between the TOC and LPT visits. (iii) Indeterminate was the category assigned when circumstances, such as missing posttreatment information or early discontinuation of treatment for reasons that were not drug related, precluded classification as clinical cure or failure.

PFGE.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) testing was performed on both the baseline and LPT visit isolates for all patients who had cultures that were positive at baseline, negative at TOC, and positive at the LPT visit for S. pyogenes. The PFGE testing was performed to determine if the culture isolates from the baseline and LPT visits were concordant or different using established interpretation criteria (46). Patients with concordant strains of S. pyogenes were determined to have persistent colonization or recurrence of the baseline organism, whereas those patients with discordant strains of S. pyogenes were determined to have a new infection with a new strain of S. pyogenes.

Statistical methods.

All data analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 8.02. All statistical tests, where considered relevant, were two sided and were interpreted at a 0.05 significance level. Patient demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment group for all study centers combined. Continuous (quantitative) variables such as age and weight were summarized using mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum, and the treatment groups were compared with respect to mean age and weight using analysis of variance with treatment group and region of the United States where enrollment occurred (Northeast, Midwest, etc.) as the main effects. Categorical (qualitative) variables, such as gender, race, ethnicity, age group, physical examination findings, clinical assessment of signs and symptoms of tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis, and number of previous episodes of tonsillopharyngitis in the previous 12 months, were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and the treatment groups were compared (if appropriate) by using a Cochran Mantel-Haenszel test.

The two treatment groups were compared with regard to compliance during the first 3 days on study medication and with regard to overall compliance during the 10-day treatment course by using a Cochran Mantel-Haenszel test for qualitative categories and by means of an analysis of variance for the summary statistics. The treatment group differences in satisfactory bacteriological outcome (i.e., bacteriological response of eradication for the PPb population and eradication or presumed eradication for other analysis populations) rates were compared by calculating the Cochran Mantel-Haenszel point estimate and two-sided 95% confidence interval for the difference in satisfactory bacteriological outcome rates. The primary efficacy analysis was performed using the PPb population. A treatment-by-region interaction (homogeneity of the odds ratio across U.S. regions) was tested using the Breslow-Day test. If an interaction existed, an exploratory analysis was to be performed to find the source of this interaction. For the secondary efficacy variables of bacteriological and clinical outcomes at the TOC and LPT visits, the tests between the two treatment groups were performed with the same analysis model as used for the primary efficacy analysis. A satisfactory bacteriological outcome of 90% in each treatment arm and a maximum difference between test and standard treatments of a δ value of 10% were assumed. These assumptions were consistent with those of other studies for the tonsillitis/pharyngitis indication. A sample size of 150 PPb patients per treatment arm was chosen to ensure with 80% power that the test treatment would be considered noninferior if the endpoint of the two-sided 95% confidence interval for the treatment difference was −10% or greater.

RESULTS

PK/PD assessment.

Twenty-three children were included in the PK phase 1 trial: 11 children (6 months to 4 years old) received a 475-mg amoxicillin sprinkle in a fed state (treatment A) and 12 children (5 to 12 years old) received a 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle in a fed state (treatment B) and a 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle in a fasted state (treatment C). Single-dose PK parameters for 475 mg and 775 mg of amoxicillin sprinkle under fed and/or fasted conditions are presented in Table 1. Under fed conditions, relative to the MIC90 of 0.06 μg/ml reported in the literature, the mean daily percentages of T >MIC were 63.8%, 58.3%, and 49.3% for children 6 months to 4 years old receiving a 475-mg amoxicillin sprinkle under fed conditions (treatment A) and children 5 to 12 years old receiving a 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle under fed (treatment B) and fasted (treatment C) conditions, respectively. Based on PK data in the literature (17), the mean daily percentage of T >MIC for 10 mg/kg of penicillin, relative to a MIC90 of 0.06 μg/ml, was 41.0% under fasted conditions.

The MIC range of amoxicillin and penicillin for the 396 S. pyogenes strains isolated at baseline from children in the clinical trial was <0.004 to 0.012 μg/ml, with a MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml for both amoxicillin and penicillin, lower than the MIC90 of 0.06 μg/ml reported in the literature.

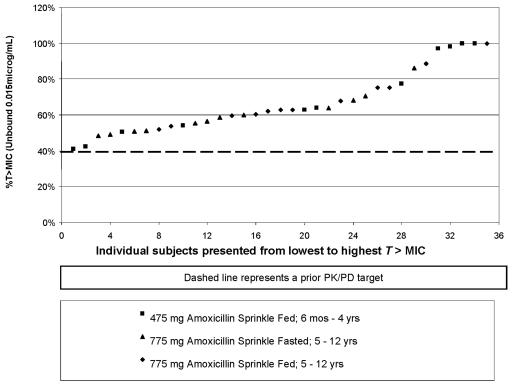

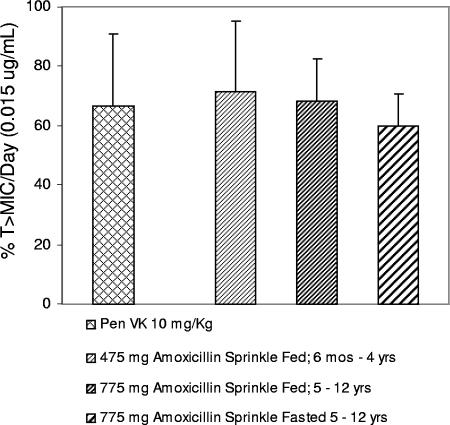

The daily T >MIC was recalculated based on the MIC95 (0.015 μg/ml) determined in the clinical trial. The individual results for the 23 children in the phase 1 study for percentage of T >MIC (using the MIC95 of 0.015 mg/ml) for the three treatments are shown in Fig. 1, which clearly demonstrates no trends for age, dose, or food intake with dosing. From those results, the average daily T >MIC for QD amoxicillin sprinkle was confirmed to be similar to that of QID penicillin determined from PK data in the literature (17) (Fig. 2). The daily T >MIC for both treatment regimens exceeded the target 40% daily T >MIC anticipated to be predictive of efficacy. The daily percentages of T >MIC achieved were 71.6%, 68.3%, 59.9%, and 66.5% for the 475-mg amoxicillin sprinkle (ages 6 months to 4 years, fed state), the 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle (ages 5 to 12 years, fed state), the 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle (ages 5 to 12 years, fasted state), and 10 mg/kg of penicillin VK QID, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Plot of percentages of T >MIC for individual subjects versus sequence number. Daily T >MIC for amoxicillin sprinkle QD was determined for individual subjects from a phase 1 study in pediatric patients with upper respiratory tract infections and was based on the MIC95 (0.015 μg/ml) determined in the phase 3 clinical trial. The numbers of children receiving amoxicillin sprinkle were as follows: 6 months to 4 years old, 475 mg, fed, n = 11; 5 to 12 years old, 775 mg, fed, n = 12; 5 to 12 years old, 775 mg, fasted, n = 12.

FIG. 2.

Daily T >MIC was based on the MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml from the clinical trial and unbound drug concentrations in plasma. Daily T >MIC for amoxicillin sprinkle QD was determined from the results of a phase 1 study in pediatric patients with upper respiratory tract infections. Daily T >MIC for penicillin (Pen VK) QID was based on data in the literature (17). The numbers of children receiving amoxicillin sprinkle were as follows: 6 months to 4 years old, 475 mg, fed, n = 11; 5 to 12 years old, 775 mg, fed, n = 12; 5 to 12 years old, 775 mg, fasted, n = 12. Values displayed are the means ± standard deviations of the results.

Clinical trial.

A total of 579 children were randomly assigned to the study medication groups (amoxicillin sprinkle, 290 patients, and penicillin VK, 289 patients). Of patients in the penicillin VK treatment group, 13.6% discontinued prior to completing the study, versus 11.1% in the amoxicillin sprinkle treatment group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Patient disposition

| Disposition, reason | No. of patients (%) receiving or discontinuing treatment

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin sprinkle | Penicillin VK | ||

| Randomized group assignment | 290 | 289 | 579 |

| Treated | 287 (100.0) | 287 (100.0) | 574 (100.0) |

| Completed study | 255 (88.9) | 248 (86.4) | 503 (87.6) |

| Prematurely discontinued study | 32 (11.1) | 39 (13.6) | 71 (12.4) |

| Reason for premature discontinuation | |||

| Insufficient therapeutic effect | 13 (4.5) | 8 (2.8) | 21 (3.7) |

| Adverse event | 13 (4.5) | 11 (3.8) | 24 (4.2) |

| Patient lost to follow-up | 4 (1.4) | 7 (2.4) | 11 (1.9) |

| Consent withdrawn | 2 (0.7) | 8 (2.8) | 10 (1.7) |

| Patient noncompliance | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) |

| Protocol violations | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.3) |

The demographic characteristics of the two treatment groups are summarized for the ITT/safety populations in Table 3. In the amoxicillin sprinkle ITT/safety population (n = 284), 3.9% of children had received an antimicrobial within 30 days of study entry, compared to 5.7% in the penicillin VK population (n = 282) (P = 0.33). The number of episodes of tonsillopharyngitis in the 12 months prior to study entry was zero in 68.3% of the amoxicillin sprinkle group and 63.8% of the penicillin VK group (P = 0.49). The percentages of subjects experiencing one, two, or three episodes of tonsillopharyngitis in the prior 12 months for the amoxicillin sprinkle population were 19%, 7.7%, and 3.2% and for the penicillin VK group were 22%, 8.9%, and 3.9%, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Demographic and baseline characteristics for ITT/safety population of patients with tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis secondary to Streptococcus pyogenes infection

| Demographic or baseline characteristic (unit of measure) | Amoxicillin sprinkle (n = 284) | Penicillin VK (n = 282) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 54.9 | 46.5 | 0.04 |

| Male | 45.1 | 53.5 | |

| Race (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 75.0 | 78.0 | 0.08 |

| African American | 11.6 | 8.5 | |

| Asian/Oriental | 2.1 | 0.4 | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.7 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 10.6 | 13.1 | |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 85.6 | 83.3 | |

| Hispanic | 14.4 | 16.7 | 0.49 |

| Age group (%) | |||

| 6 mo to 2 yr | 9.5 | 6.4 | 0.70 |

| 3 to 4 yr | 11.3 | 11.7 | |

| 5 to 7 yr | 38.7 | 37.6 | |

| 8 to 12 yr | 40.5 | 44.3 | |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (2.78) | 7.0 (2.80) | 0.22 |

| Median (range) | 7.0 (0.5-12) | 7.0 (0.5-12) | |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| 6 mo to 4 yrs (475-mg amoxicillin sprinkle) | |||

| No. in group | 58 | 51 | |

| Mean (SD) | 15.92 (3.65) | 15.60 (3.35) | 0.65 |

| Median (range) | 16.10 (8.9-24.0) | 16.10 (9.0-24.5) | |

| 5 yrs to 12 yrs (775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle) | |||

| No. in group | 224 | 231 | |

| Mean (SD) | 31.71 (12.13) | 32.07 (11.81) | 0.74 |

| Median (range) | 28.33 (15.6-82.7) | 29.03 (14.1-71.2) |

P value was calculated by using a Cochran Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by region of the United States.

The baseline characteristics of the infections are summarized in Table 4. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups in the occurrence of previous tonsillopharyngitis episodes or antimicrobial therapy or in the distribution of characteristics of the current infection for the ITT/safety population.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of current infection in ITT population

| Characteristic/key factor | % of patients treated with:

|

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin sprinkle (n = 284) | Penicillin VK (n = 282) | ||

| Sore throat | 97.2 | 98.9 | 0.13 |

| Odynophagia | |||

| Mild | 40.8 | 37.9 | 0.26 |

| Moderate | 41.5 | 45.4 | |

| Severe | 8.8 | 5.0 | |

| Fever | |||

| Mild | 35.6 | 33.0 | 0.99 |

| Moderate | 27.5 | 24.5 | |

| Severe | 7.4 | 10.3 | |

| Strawberry tongue | 22.9 | 23.0 | 1.0 |

| Uvular edema | |||

| Mild | 33.6 | 35.4 | 0.91 |

| Moderate | 16.6 | 17.1 | |

| Severe | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| Pharyngeal erythema | |||

| Moderate | 76.1 | 83.0 | 0.06 |

| Severe | 17.6 | 10.6 | |

| Pharyngeal exudates | 33.8 | 29.1 | 0.22 |

| Tender lymph nodes | |||

| Mild | 47.5 | 47.2 | 0.93 |

| Moderate | 18.7 | 20.9 | |

| Severe | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| Cervical adenopathy | |||

| Mild | 52.1 | 44.0 | 0.55 |

| Moderate | 22.9 | 28.0 | |

| Severe | 2.5 | 3.2 | |

| Distribution of adenopathy | |||

| Periauricular | 1.4 | 2.4 | |

| Submandibular | 34.5 | 32.1 | |

| Submental | 3.6 | 4.2 | |

| Anterior | 70.9 | 74.5 | |

| Posterior | 15.5 | 11.3 | |

P value was calculated by using a Cochran Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by region.

In the ITT/safety population, 97.2% of patients in the amoxicillin sprinkle group and 83.7% of patients in the penicillin VK group were 100% compliant with their study medication during the first 3 days of the study. Over the entire treatment period, 95.4% of patients in the amoxicillin sprinkle group and 90.4% of patients in the penicillin VK group were at least 80% compliant with their study medication.

Primary efficacy results.

The results of the primary efficacy analysis, bacteriological outcome at the TOC visit in the PPb population, are presented in Table 5. Although the bacteriological outcome at the TOC visit was similar for the amoxicillin sprinkle (65.3%) and the penicillin VK (68.0%) treatment groups, amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 7 days failed to demonstrate noninferiority to penicillin VK QID for 10 days (95% confidence interval, −12.0% to 6.6%). No treatment-by-region interaction existed, as demonstrated by the Breslow-Day test (P = 0.59).

TABLE 5.

Bacteriological outcomes at the TOC visit in PPb population and clinical outcomes at TOC visit in PPc population

| Efficacy endpoint and outcome | No. (%) of patients treated with:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin sprinkle | Penicillin VK | |

| Bacteriological outcome at TOC | ||

| No. in population | 202 | 194 |

| Eradication | 132 (65.3) | 132 (68.0) |

| Total failures | 70 (34.7) | 62 (32.0) |

| Failure due to persistence | 59 (29.2) | 56 (28.9) |

| Presumed failurea | 11 (5.4) | 6 (3.1) |

| Bacteriological outcome at LPT | ||

| No. in population | 195 | 181 |

| Eradication at TOC and at LPTb | 108 (55.4) | 103 (56.9) |

| Total failures at LPT visits | ||

| Failure at TOCc | 68 (34.9) | 58 (32.0) |

| Presumed failured | 8 (4.1) | 7 (3.9) |

| Eradication at TOC with failure at LPT, same strain | 9 (4.6) | 9 (4.4) |

| New infection at LPTe | 2 (1.0) | 4 (2.2) |

| Clinical outcome at TOC | ||

| No. in population | 251 | 222 |

| Clinical cure | 216 (86.1) | 204 (91.9) |

| Clinical failure | 30 (12.0) | 14 (6.3) |

| Indeterminate | 5 (2.0) | 4 (1.8) |

Presumed failures included those patients who started a new antimicrobial for the treatment of tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis before the TOC visit.

Patients with eradication at TOC and at LPT included those with a bacteriological response of eradication at TOC and presumed eradication at LPT.

Failure at TOC was carried forward as a failure at LPT.

Presumed failure included those patients who started a new antimicrobial for the treatment of tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis between the TOC and LPT visit.

One subject in the penicillin VK group is included in this outcome although no PFGE was performed.

The bacteriological outcome at the TOC visit was also analyzed by subgroups of the PPb population based on demographic (gender, age, race, and ethnicity) and current infection (antimicrobial therapies within 30 days of study entry, S. pyogenes infections within 12 months of study entry, and current infection signs and symptoms) characteristics. In general, the rate of satisfactory bacteriological outcome at the TOC visit across demographic characteristics and current infection characteristics was consistent with the outcome at the TOC visit for the primary efficacy population (i.e., the overall PPb population), although not all categories within a subgroup were equally represented.

The results of the secondary efficacy analysis of bacteriological outcome at the LPT in the PPb population are presented in Table 5. The total bacteriologic failures at TOC plus LPT visits were 43.6% for amoxicillin sprinkle and 40.3% for penicillin VK.

Clinical outcome.

The results of the secondary efficacy analysis of clinical outcome at the TOC visit in the PPc population are presented in Table 5. As observed for the bacteriological efficacy analyses, amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 7 days failed to demonstrate noninferiority to penicillin VK QID for 10 days at TOC (95% confidence interval, −11.6% to −0.4%).

PFGE testing.

Twenty-three PPb patients (amoxicillin sprinkle, 11, and penicillin VK, 12) were found to have cultures that were positive at baseline, negative at TOC, and positive at the LPT visit for S. pyogenes. PFGE testing was performed to determine if the isolates from these patients at the baseline and LPT visits were concordant or discordant strains of S. pyogenes. Seventeen of 23 (75%) patients (amoxicillin sprinkle, 9, and penicillin VK, 8) were determined to have concordant baseline and LPT visit strains of S. pyogenes and were considered to have persistent colonization or recurrence of the baseline organism (carrier/recolonization). All 17 patients were considered clinical cures by the treating physician. Six of 23 (25%) patients (amoxicillin sprinkle, 2, and penicillin VK, 4) with discordant strains of S. pyogenes were determined to have a new infection with a new strain of S. pyogenes.

Alternative PK/PD modeling.

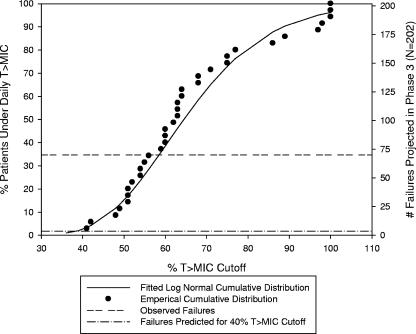

One possible explanation for the high failure rate in the clinical trial was that the range of actual T >MICs in patients in the clinical trial was not accurately predicted by the T >MIC distribution observed in the small population in the phase 1 study. The daily T >MIC data from the phase 1 study in pediatric patients was therefore fitted to a log normal distribution. The scale and shape factors of the fitted distribution and the 95% confidence intervals for these parameters are described in the Fig. 3 legend. The cumulative distribution of the phase 1 daily T >MIC data predicted that >95% of patients would exceed a 40% daily T >MIC with the regimens utilized in the clinical trial, assuming a MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml. Based solely on this predicted target attainment, the corresponding projected number of failures should have been less than 10 (2%) for the completed clinical trial. However, based on the number of failures actually observed in this trial, the required daily T >MIC was recalculated to be nearly 60% of the daily dosing interval for effective therapy. That is, approximately 65% of patients are predicted to exceed a 60% daily T >MIC cutoff.

FIG. 3.

PD endpoint assessment of projected failures based on different percentage of T >MIC PD endpoints (using phase 1 data) using unbound drug at a MIC of 0.015 μg/ml. The daily T >MIC data for amoxicillin sprinkle from a separate phase 1 study were fitted to a log normal distribution, and the log normal distribution parameters and 95% confidence intervals were determined (using JMP version 5.0.1a). The cumulative distribution of the fitted T >MIC data was then utilized to determine the projected number of therapeutic failures assuming a 40% T >MIC. The scale parameter estimate was 4.17, with a 95% confidence interval of 4.08 to −4.25. The shape parameter estimate was 0.25, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.21 to −0.31.

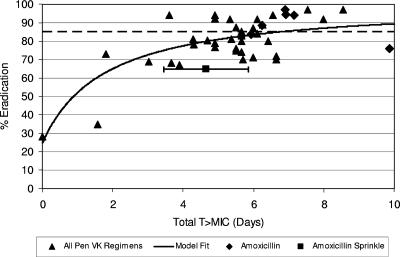

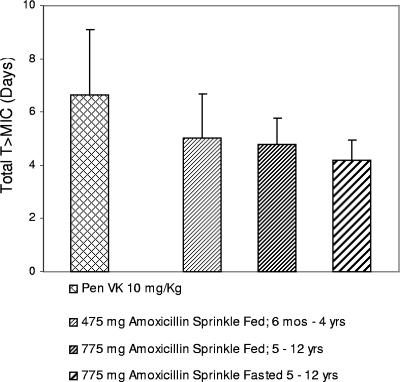

Another, alternative PK/PD target, based on T >MIC achieved over the duration of therapy, i.e., total T >MIC, was explored. The bacteriological eradication results from 36 trials evaluating various penicillin dose regimens as treatments for tonsillopharyngitis due to S. pyogenes were assessed in relation to total T >MIC (assuming a MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml) achieved, and a model was fitted (4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20-26, 30-32, 34, 37-45, 49, 50). The data are shown in Fig. 4. The total T >MICs of amoxicillin sprinkle and six dosing regimens of immediate-release amoxicillin are presented in the figure also (1, 8, 10, 16, 33, 38). Based on this assessment, the rates of eradication of S. pyogenes for penicillin and amoxicillin were predicted to be 75% at a total T >MIC of 3.45 days, 77% at 3.88 days, 80% at 4.70 days, 85% at 6.72 days, 88% at 8.69 days, and 90% at 10.6 days. The 475-mg and 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle dosing regimens used in the clinical trial (QD for 7 days) would produce total T >MIC95 of 5.01 ± 1.67 (mean ± standard deviation) days and 4.78 ± 1.00 days, respectively, whereas the dosing regimen for penicillin (QID for 10 days) would produce a total T >MIC95 of 6.65 ± 2.42 days (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Plot of eradication rate versus T >MIC (assuming a MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml) achieved over the duration of therapy, i.e., total T >MIC, for various penicillin (Pen VK) dose regimens (▴) (4, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 30, 31, 32, 34, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 49, 50) compared to those achieved by amoxicillin sprinkle (▪, with 95% confidence interval shown as a bar) (based on average of both doses) and various amoxicillin dose regimens (♦) (1, 8, 11, 16, 33, 38) for the treatment of tonsillopharyngitis due to S. pyogenes. Model fit is based on penicillin VK data. The dashed line is at 85% eradication per U.S. FDA criterion standard.

FIG. 5.

Total T >MIC (days) was based on the MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml from the clinical trial and unbound-drug concentrations in plasma. Total T >MIC for amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 7 days was determined from the results of a phase 1 study in pediatric patients with upper respiratory tract infections. Total T >MIC for penicillin (Pen VK) QID for 10 days was based on data in the literature (17). The numbers of children receiving amoxicillin sprinkle were as follows: 6 months to 4 years old, 475 mg, fed, n = 11; 5 to 12 years old, 775 mg, fed, n = 12; 5 to 12 years old, 775 mg, fasted, n = 12. Values displayed are the means ± standard deviations of the results.

DISCUSSION

Based on a phase 1 PK/PD analysis, the amoxicillin sprinkle and penicillin VK treatment regimens used in this study were predicted to exceed a 40% target daily T >MIC coverage against S. pyogenes. However, in a clinical trial, neither the amoxicillin sprinkle administered QD for 7 days nor penicillin VK QID for 10 days met the minimum U.S. FDA criterion of ≥85% bacteriological eradication at TOC ordinarily required for first-line therapy (48). In fact, the rates of satisfactory bacteriological outcome in the amoxicillin sprinkle and penicillin VK treatment groups were 65.3% and 68.0%, respectively, corroborating literature reports of a trend to increasing rates of failure of penicillin in children (6). Because the failure to achieve the a priori PK/PD drug attainment target could not explain the low bacteriological eradication rates observed for amoxicillin sprinkle QD and penicillin VK QID in the clinical trial, alternative PK/PD modeling was undertaken. One analysis suggested that a requirement for 60% daily T >MIC more closely fit the observed results in the clinical trial.

Another alternative PK/PD target explored was total T >MIC, a composite parameter based on the overall T >MIC achieved over the duration of therapy. This alternative approach is supported by a review (15) that emphasized the importance of the aggregate time penicillin remains at effective bactericidal levels. We evaluated this alternative model and found that it suggested that the amoxicillin sprinkle failure rate might be explainable, since the dosing regimens of 475-mg amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 7 days and 775-mg amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 7 days provided 5.0 and 4.8 days of total T >MIC, respectively, while the model suggested a need for 6.7 days to achieve an eradication rate of 85%. However, this alternative total T >MIC model did not predict the observed penicillin failure rate; penicillin QID for 10 days achieved a total T >MIC of 6.6 days.

We considered using tonsillar antibiotic levels rather than plasma levels of drug in our model; however, there is limited literature available on amoxicillin concentrations in tonsillar tissue. The data presented generally describe tonsillar tissue concentrations from tissue biopsy homogenates, which underestimate the interstitial-tissue concentrations of amoxicillin. Beta-lactams are known to distribute almost exclusively from plasma into the interstitial-space fluid of well-perfused tissues due to their hydrophilic properties. This is especially so for compounds with low protein binding, such as amoxicillin (the protein-bound fraction is 22%). Furthermore, it is the free, unbound drug that distributes into the interstitial spaces and exerts antimicrobial activity. Thus, amoxicillin concentrations in the interstitial spaces of the tonsillar tissue are expected to be similar to plasma concentrations of amoxicillin not bound by plasma protein; the unbound plasma concentration of amoxicillin is considered an adequate representation of expected amoxicillin exposure in the interstitial spaces of the tonsillar tissue.

The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases recently stated that preliminary investigations suggest that orally administered amoxicillin given as a single daily dose for 10 days is an antibiotic regimen with an effectiveness comparable to that of orally administered penicillin VK given TID for 10 days (35). If confirmed by additional investigations, QD amoxicillin could become an alternative regimen for the treatment of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. This assessment was based on the results of two small studies reporting that a QD dose of immediate-release amoxicillin (50 mg/kg QD to a maximum 750 mg QD) for 10 days was as effective in the eradication of S. pyogenes as penicillin V TID or QID for 10 days. (16, 38) However, the small number of patients in each of those studies (80 or fewer patients per treatment group in each study) precluded definitive conclusions. In another, more recently published study, the noninferiority of immediate-release amoxicillin QD (750 mg QD for subjects <40 kg or 1,000 mg QD for subjects ≥40 kg) compared to immediate-release amoxicillin BID (375 mg BID for subjects <40 kg or 500 mg BID for subjects ≥40 kg) for 10 days was assessed. In that larger, investigator-blinded, single-center study (7), the reported bacteriological failure rates were 20.1% and 15.5% following treatment with amoxicillin QD and BID regimens, respectively, demonstrating higher failure rates than acceptable under current U.S. FDA standards for first-line therapy.

For the amoxicillin sprinkle QD regimen studied here and based on total T >MIC considerations, it may be that the bacteriological eradication rate would have been higher following 10 days of therapy rather than the 7 days used. Amoxicillin sprinkle was designed to provide plasma concentrations of amoxicillin that were prolonged relative to the plasma concentrations with immediate-release amoxicillin. The predicted total T >MICs (assuming a MIC95 of 0.015 μg/ml) for the 475-mg and 775-mg amoxicillin doses for 10 days are 7.2 and 6.8 days, respectively, exceeding the total T >MIC target of 6.7 days required for an eradication rate of 85% as suggested by the alternative total T >MIC model (Fig. 4). The total T >MIC expected to be achieved by amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 10 days is greater than that which would be achieved by the QD administration of 750 mg of immediate-release amoxicillin in the results of studies previously described, and thus, amoxicillin sprinkle QD for 10 days would be expected to have a higher eradication rate than that reported in the literature for 750 mg of immediate-release amoxicillin QD for 10 days. The results of recently completed studies of a QD modified-release amoxicillin tablet formulation, similar to the amoxicillin sprinkle formulation studied here, in the treatment of tonsillopharyngitis secondary to S. pyogenes in adolescents and adults lend credence to the importance of duration of therapy and total T >MIC achieved by the modified-release amoxicillin formulations. A 7-day treatment course with the 775-mg amoxicillin tablet QD failed to demonstrate noninferiority to 250 mg of penicillin VK QID for 10 days. However, in the results of a second study, a 775-mg amoxicillin tablet QD for 10 days was noninferior to 250 mg of penicillin VK QID for 10 days (amoxicillin tablet eradication rate, 85.0%, and penicillin VK eradication rate, 83.4%) (3).

In summary, neither this amoxicillin sprinkle formulation administered QD for 7 days nor 10 mg/kg of penicillin VK suspension QID for 10 days meet the minimum criterion of ≥85% eradication rate ordinarily required by the U.S. FDA for first-line treatment of tonsillopharyngitis due to S. pyogenes. A daily T >MIC of 40% for the dosing interval, widely accepted as a relevant PD endpoint, was achieved with both drug regimens, and yet both regimens produced unsatisfactory eradication rates.

Considering daily T >MIC in isolation, an alternative PK/PD target of 60% daily T >MIC more closely predicted the results in the clinical trial and described in the literature for eradication of S. pyogenes with penicillin and amoxicillin in the pediatric population. The effect of total T >MIC achieved for the duration of therapy was also considered and would appear to be an important contributor to the efficacies of penicillin and amoxicillin in terms of bacterial eradication.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguilar, A., J. C. Tinoco, M. Macias, L. Huicho, J. Levy, H. Trujillo, P. Lopez, M. Pereira, S. Maqbool, Z. A. Bhutta, R. A. Sacy, and S. Deacon. 2000. Clinical and bacteriologic efficacy of amoxycillin b.d. (45 mg/kg/day) versus amoxycillin t.d.s (40 mg/kg/day) in children with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. J. Chemother. 12:396-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisno, A. L., M. A. Gerber, J. M. Gwaltney, Jr., E. L. Kaplan, and R. H. Schwartz. 2002. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block, S. L. 2007. Safety and efficacy of amoxicillin PULSYS 775 mg PO QD for 10 days compared to penicillin VK 250 mg QID for 10 days in the treatment of Streptococcus pyogenes tonsillitis and/or pharyngitis in adolescents and adults, abstr. 199a. Abstr. 45th Ann. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am., San Diego, CA, 4 to 7 October 2007.

- 4.Block, S. L., J. A. Hedrick, and R. D. Tyler. 1992. Comparative study of the effectiveness of cefixime and penicillin V for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 11:919-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley, J. S., M. N. Dudley, and G. L. Drusano. 2003. Predicting efficacy of antiinfectives with pharmacodynamics and Monte Carlo simulation. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22:982-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casey, J. R., and M. E. Pichichero. 2004. Meta-analysis of cephalosporin versus penicillin treatment of group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis in children. Pediatrics 113:866-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clegg, H. W., A. G. Ryan, S. D. Dallas, E. L. Kaplan, D. R. Johnson, H. J. Norton, O. F. Roddey, E. S. Martin, R. L. Swetenburg, E. W. Koonce, M. M. Felkner, and P. M. Giftos. 2006. Treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis with once-daily compared with twice-daily amoxicillin. A non inferiority trial. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25:761-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, R., C. Levy, C. Doit, F. De La Rocque, M. Boucherat, F. Fitoussi, J. Langue, and E. Bingen. 1996. Six-day amoxicillin vs. ten-day penicillin V therapy for group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 15:678-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig, W. A. 1998. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtin-Wirt, C., J. R. Casey, P. C. Murray, C. T. Cleary, W. J. Hoeger, S. M. Marsocci, M. L. Murphy, and A. B. Francis. 2003. Efficacy of penicillin vs. amoxicillin in children with group A beta hemolytic streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. Clin. Pediatr. 42:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dajani, A. S., S. L. Kessler, R. Mendelson, D. L. Uden, and W. M. Todd. 1993. Cefpodoxime proxetil vs. penicillin V in pediatric streptococcal pharyngitis/tonsillitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 12:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derrick, C. W., and H. C. Dillon. 1974. Therapy for prevention of acute rheumatic fever. Circulation 50:38. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Disney, F. A., B. B. Breese, A. B. Francis, J. L. Green, and W. B. Talpey. 1979. The use of cefaclor in the treatment of beta-haemolytic streptococcal throat infections in children. Postgrad. Med. J. 55:50-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Disney, F. A., H. Dillon, J. L. Blumer, B. A. Dudding, S. E. McLinn, D. B. Nelson, and S. M. Selbst. 1992. Cephalexin and penicillin in the treatment of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal throat infections. Am. J. Dis. Child 146:1324-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eagle, H., R. Fleischman, and A. D. Musselman. 1950. Effect of schedule of administration on the therapeutic efficacy of penicillin. Am. J. Med. 9:280-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feder, H. M., Jr., M. A. Gerber, M. F. Randolph, P. S. Stelmach, and E. L. Kaplan. 1999. Once-daily therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis with amoxicillin. Pediatrics 103:47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita, K., H. Sakata, K. Murono, H. Hasegawa, M. Takimoto, and H. Yoshioka. 1983. Comparative pharmacological evaluation of oral bezathine penicillin G and phenoxymethyl penicillin potassium in children. Pediatr. Pharmacol. 3:37-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gau, D. W., R. F. Horn, R. M. Solomon, P. Johnson, and D. A. Leigh. 1972. Streptococcal tonsillitis in general practice. A comparison of cephalexin and penicillin therapy. Practitioner 208:276-281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerber, M. A. 2005. Diagnosis and treatment of pharyngitis in children. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 52:729-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerber, M. A., M. F. Randolph, J. Chanatry, L. L. Wright, L. R. Anderson, and E. L. Kaplan. 1986. Once daily therapy for streptococcal pharyngitis with cefadroxil. J. Pediatr. 109:531-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gervaix, A., L. Brighi, D. S. Halperin, and S. Suter. 1995. Cefetamet pivoxil in the treatment of pharyngotonsillitis due to group A beta-hemolytic streptococci: preliminary report. J. Chemother. 7(suppl. 1):21-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginsburg, C. M., G. H. McCracken, Jr., S. D. Crow, J. B. Steinberg, and F. Cope. 1980. A controlled comparative study of penicillin V and cefadroxil therapy of group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. J. Int. Med. Res. 8:82-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginsburg, C. M., G. H. McCracken, Jr., J. B. Steinberg, S. D. Crow, B. F. Dildy, F. Cope, and T. Zweighaft. 1982. Treatment of group A streptococcal pharyngitis in children: results of a prospective, randomized study of four antimicrobial agents. Clin. Pediatr. 21:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldfarb, J., E. Lemon, J. O'Horo, and J. L. Blumer. 1988. Once-daily cefadroxil versus oral penicillin in the pediatric treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin. Ther. 10:178-182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gooch, W. M., III, E. Swenson, M. D. Higbee, D. M. Cocchetto, and E. C. Evans. 1987. Cefuroxime axetil and penicillin V compared in the treatment of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin. Ther. 9:670-677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henness, D. M. 1982. A clinical experience with cefadroxil in upper respiratory tract infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 10(Suppl. B):125-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.IMS America, Ltd. 2003. National disease and therapeutic index: data, January, 2003. IMS America, Ltd., Ambler, PA.

- 28.Kaplan, E. L., D. R. Johnson, M. C. Del Rosario, and D. L. Horn. 1999. Susceptibility of group A beta-hemolytic streptococci to thirteen antibiotics: examination of 301 strains isolated in the United States between 1994 and 1997. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:1069-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacGowan, A., and R. Wise. 2001. Establishing MIC breakpoints and the interpretation of in vitro susceptibility tests. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:17-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsen, J. M., O. Torstenson, S. E. Siegel, and H. Bacaner. 1974. Use of available dosage forms of cephalexin in clinical comparison with phenoxymethyl penicillin and benzathine penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 6:501-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milatovic, D., D. Adam, H. Hamilton, and E. Materman. 1993. Cefprozil versus penicillin V in treatment of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1620-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nemeth, M. A., W. M. Gooch III, J. Hedrick, E. Slosberg, C. H. Keyserling, and K. J. Tack. 1999. Comparison of cefdinir and penicillin for the treatment of pediatric streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin. Ther. 21:1525-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peyramond, D., H. Portier, P. Geslin, R. Cohen, et al. 1996. 6-Day amoxicillin versus 10-day penicillin V for group A beta-haemolytic streptococcal acute tonsillitis in adults: a French multicentre, open-label, randomized study. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 28:497-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pichichero, M. E., F. A. Disney, G. H. Aronovitz, W. B. Talpey, J. L. Green, and A. B. Francis. 1987. Randomized, single-blind evaluation of cefadroxil and phenoxymethyl penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:903-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pickering, L. K. (ed.). 2006. Red book: 2006 report of the committee on infectious diseases, 26th ed. Group A streptococcal infections, p. 495-496. Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, IL.

- 36.Reference deleted.

- 37.Schwartz, R. H., R. L. Wientzen, Jr., F. Pedreira, E. J. Feroli, G. W. Mella, and V. L. Guandolo. 1981. Penicillin V for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. A randomized trial of seven vs ten days' therapy. JAMA 246:1790-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shvartzman, P., H. Tabenkin, A. Rosentzwaig, and F. Dolginov. 1993. Treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis with amoxycillin once a day. BMJ 306:1170-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stillerman, M. 1970. Comparison of cephaloglycin and penicillin in streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 11:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stillerman, M. 1986. Comparison of oral cephalosporins with penicillin therapy for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 5:649-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stillerman, M., and H. D. Isenberg. 1970. Streptococcal pharyngitis therapy: comparison of cyclacillin, cephalexin, and potassium penicillin V. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2:270-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stillerman, M., H. D. Isenberg, and M. Moody. 1972. Streptococcal pharyngitis therapy: comparison of cephalexin, phenoxymethyl penicillin and ampicillin. Am. J. Dis. Child. 123:457-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stromberg, A., A. Schwan, and O. Cars. 1988. Five versus ten days treatment of group A streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial with phenoxymethylpenicillin and cefadroxil. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 20:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tack, K. J., J. A. Hedrick, E. Rothstein, M. A. Nemeth, C. Keyserling, M. E. Pichichero, et al. 1997. A study of 5-day cefdinir treatment for streptococcal pharyngitis in children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 151:45-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takker, U., O. Dzyublyk, T. Busman, and G. Notario. 2003. Comparison of 5 days of extended-release clarithromycin versus 10 days of penicillin V for the treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis/tonsillitis: results of a multicenter, double-blind, randomized study in adolescent and adult patients. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 19:421-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thummel, K., and D. Shen. 2001. Design and optimization of dosage regimens: pharmacokinetic data, p. 1917-2023. In J. Hardman, L. Limbird, and A. Gilman (ed.), Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 10th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

- 48.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 1998. Guidance for industry: streptococcal pharyngitis and tonsillitis—developing antimicrobial drugs for treatment. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Washington, DC. http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/2562dft.pdf.

- 49.Zwart, S., M. M. Rovers, R. A. de Melker, and A. W. Hoes. 2003. Penicillin for acute sore throat in children: randomized, double-blind trial. BMJ 327:1324-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwart, S., A. P. E. Sachs, G. J. H. M. Ruijs, J. W. Gubbels, A. W. Hoes, and R. A. de Melker. 2000. Penicillin for acute sore throat: randomized double blind trial of seven days versus three days treatment of placebo in adults. BMJ 320:150-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]