Abstract

Mammalian Cdk5 is a member of the cyclin-dependent kinase family that is activated by a neuron-specific regulator, p35, to regulate neuronal migration and neurite outgrowth. p35/Cdk5 kinase colocalizes with and regulates the activity of the Pak1 kinase in neuronal growth cones and likely impacts on actin cytoskeletal dynamics through Pak1. Here, we describe a functional homologue of Cdk5 in budding yeast, Pho85. Like Cdk5, Pho85 has been implicated in actin cytoskeleton regulation through phosphorylation of an actin-regulatory protein. Overexpression of CDK5 in yeast cells complemented most phenotypes associated with pho85Δ, including defects in the repression of acid phosphatase expression, sensitivity to salt, and a G1 progression defect. Consistent with the functional complementation, Cdk5 associated with and was activated by the Pho85 cyclins Pho80 and Pcl2 in yeast cells. In a reciprocal series of experiments, we found that Pho85 associated with the Cdk5 activators p35 and p25 to form an active kinase complex in mammalian and insect cells, supporting our hypothesis that Pho85 and Cdk5 are functionally related. Our results suggest the existence of a functionally conserved pathway involving Cdks and actin-regulatory proteins that promotes reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in response to regulatory signals.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) comprise a large family of proteins whose members are well known as key regulators that promote cell cycle progression in eukaryotic cells (reviewed in ref. 1). Recent studies have highlighted roles for Cdks in postmitotic cells, in gene expression, and in cell regulation beyond cell cycle control (2, 3). Although highly homologous to other members of the Cdk family, mammalian Cdk5 has no known function in proliferative cells. Rather, Cdk5-associated kinase activity is restricted to postmitotic neurons and Cdk5 is required for histogenesis of the central nervous system and neurite outgrowth (2, 4–6). Cdk5 phosphorylates syntaxin 1, Munc18, and synapsin I (7, 8), suggesting a regulatory role for actin cytoskeletal dynamics. In the growth cones of cultured cortical neurons, Cdk5 and its neuron-specific activator, p35, colocalize with actin filaments at the growth cone periphery (5). More recently, p35/Cdk5 was shown to colocalize with two actin-regulatory proteins, the Rho-type GTPase Rac and the Pak1 kinase, in neuronal growth cones (9). Phosphorylation of Pak1 kinase by p35-Cdk5 may contribute to the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton that occurs during neurite outgrowth and neuronal migration.

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, two Cdk complexes, Cln-Cdc28 and Pcl-Pho85, have been implicated in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. The Cdc28 kinase is responsible for cell cycle transitions and can be activated by nine cyclin regulatory subunits, the Clns and the Clbs (reviewed in ref. 3). Inappropriate expression of Cln-Cdc28 kinases leads to altered bud emergence, suggesting a role for Cdc28 in regulating cell polarity and budding (10). The Pho85 Cdk is also activated by multiple cyclins and has roles in both cell cycle control and metabolic processes (3). Although PHO85 is not an essential gene, it is required for viability in some stress conditions, such as growth after starvation (11). In addition, pho85 mutants display a broad spectrum of phenotypes, including slow growth in rich medium, derepressed acid phosphatase activity, hyperaccumulation of glycogen, and defects in G1 progression and actin cytoskeleton regulation (11–15). Consistent with the multifunctional nature of Pho85, 10 genes encoding known or putative Pho85 cyclins (Pcls) have been identified (16). Expression of three of the PCLs—PCL1, PCL2, and PCL9—is cell cycle-regulated with peak transcript levels in G1 phase, whereas expression of other Pho85 cyclins is constant through the cell cycle.

Like Cdk5, Pho85 plays important roles in polarized cell growth and cytoskeletal dynamics. Yeast strains lacking PCL1,2-like cyclins are morphologically abnormal and display phenotypes consistent with a disruption of the actin cytoskeleton (11, 16, 17). Pcl-Pho85 kinases contribute to actin regulation at least in part through phosphorylation of the Rvs167 protein (11). Rvs167 is a modular protein composed of at least three distinct protein-interaction domains and likely functions in multiprotein complexes to regulate actin polarization (17, 18). Among Cdks, Pho85 is most closely related to Cdk5, with 56% identity and 72% similarity at the primary amino acid level. To explore the functional significance of the protein sequence similarity between Pho85 and Cdk5, and their similar roles in the regulation of asymmetric growth, we used in vivo complementation assays and in vitro reconstitution to show that Pho85 and Cdk5 are functional homologues. Our observations led us to propose the existence of a functionally conserved regulatory pathway, involving cyclin-dependent kinases and their targets, that regulates the actin cytoskeleton in response to regulatory stimuli.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Strains and Media.

The wild-type (BY263, MATa trp1Δ63 leu2-Δ1 his3Δ200 ura3–52 lys2 ade2) and pho85Δ strains (BY391, pho85∷LEU2, otherwise isogenic to BY263) have been described (16). We used a PCR-based strategy to target a triple-hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag to the N-terminal coding sequence of PCL2 in strain BY263. PCR conditions were as described by using plasmid pFA6a-kanMX6-PGAL1–3HA as template (19). The epitope-tagged allele of PCL2 is expressed from the inducible GAL promoter (strain 263HA- PCL2, BY1116, MATa trp1 leu2 his3 ura3 lys2 ade2 pcl2∷pGAL-HA-PCL2∷Kanr). A pho85 deletion strain carrying the tagged PCL2 allele (pho85HA-PCL2, BY1129) was constructed by crossing strain 263HA-PCL2 to strain BY864 [pho85ΔTRP1 (11)]. Strain BY794 was used to assay complementation of the G1 arrest phenotype in a pho85 cln1 cln2 mutant and had the following genotype: cln1ΔTRP1 cln2ΔLEU2 pho85ΔLEU2 (pMETpho85ts17-HIS3), otherwise isogenic to BY263. A slt2ΔLEU2 pho85ΔTRP1 strain was constructed by mating strains Y782 [slt2ΔLEU2 (20)] and BY864 (pho85ΔTRP1). The resulting diploid strain was transformed with either plasmid pGALCDK5 (see below, pCDK5) or pGAL-PHO85-HIS3 (12), and pho85 slt2 double mutants were recovered by dissecting tetrads on galactose medium. Yeast cells were grown in supplemented minimal medium with either 2% dextrose (SD) or galactose (SG). Low- and high-phosphate SG media were prepared by using phosphate-depleted yeast nitrogen base and KH2PO4 supplements. Salt-containing medium was prepared by addition of NaCl to 0.75 M.

COS-7 and Insect Cell Culture.

COS-7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin. Transient transfections of pCDNA3-based p35, p25, Cdk5, and PHO85 expression constructs in COS-7 cells were performed by using standard calcium phosphate methods. Hi5 insect cells were maintained in Grace’s Insect media and were infected with baculovirus 24 hr before harvesting for lysate preparation.

Plasmids.

To express PHO80 from the GPD promoter in yeast, an HA tagged-PHO80 allele (21) was cloned into vector pBA230v (ATCC no. 87357, 2-μ, TRP1, GPD promoter) to create plasmid pGPDPHO80 (pBA1276). Likewise, plasmid pBA230v-p35 (pBA1277) was constructed by subcloning the p35 gene from plasmid pcDNA3-p35 (see below) into pBA230v. Vectors for expressing CDK5 (pMR438PSS) and antisense CDK5 (CDK5-I, pMR438SSP) from the GAL promoter in yeast have been described (22). A PHO85 expression plasmid was constructed by subcloning the PHO85 gene into a modified pRS426 [2 μ-URA3 (23)] to allow expression from the GAL promoter [pGAL-PHO85-URA3 (pBA1073)]. The ts17 allele of PHO85 was isolated in a screen for temperature-sensitive alleles of PHO85 and was expressed from the MET25 promoter in vector pRS313-Met, a modified version of plasmid pRS313 (23).

The p35 and Cdk5 mammalian expression constructs have been described (5). CMV-p25 (vector expressing an N-terminal deletion mutant of p35) was made by PCR by using a 3′ p35 primer and a 5′ deletion primer. For expression of PHO85 in mammalian cells, an HA-tagged PHO85 gene was cloned into the pCDNA3 mammalian construct vector. Baculovirus constructs for expressing glutathione S-transferase (GST)-Pho85 and GST-Pcl2 were made by subcloning the PHO85 and PCL2 ORFs into vector pAcGHLT-B or -C (PharMingen). The kinase-dead (D151N) allele of PHO85 was constructed by using a two-step PCR strategy and the PHO85 cDNA cloned into pBluescript as a template. Mutagenized PCR fragments were recloned into pBluescript and sequenced; the D151N-containing PHO85 fragment then was cloned into baculoviral vector pAcHLT (PharMingen). GST-Cdk5 and GST-p25 baculoviruses were a gift from John Auperion (Pfizer Diagnostics).

Immunoprecipitation, Western Analysis, and Kinase Assays.

Kinase assays on immunoprecipitates from yeast extracts were performed as described (12) by using purified Pho4 as substrate (see ref. 21). COS-7 and Hi5 insect cells were lysed in ELB lysis buffer plus inhibitors (50 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4/250 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0/0.1% NP-40/5 mM NaF/100 μg/ml PMSF/2 μg/ml aprotinin/1 μg/ml leupeptin/5 mM NaVO3). Lysates were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads or with anti-p35 antibodies, and kinase reactions were performed as described (24). 12CA5 (anti-HA), DC17 (anti-cdk5), and pAb p35 (anti-p35) antibodies were used for Western analysis.

Other Methods.

Measurement of repressible acid phosphatase activity was done as described (25). For photomicroscopy, cells were observed at a magnification of either ×630 or ×1,000 by using Nomarski optics and a Micromax 1300y high-speed digital camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) mounted on a Leica DM-LB microscope. Images from the camera were analyzed with metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Media, PA).

Results

Complementation of pho85Δ Phenotypes by Overexpression of CDK5.

To ask whether Cdk5 can functionally substitute for Pho85 in yeast cells, we used a yeast expression vector in which CDK5 was expressed from the inducible GAL promoter (pCDK5). CDK5 cloned in inverse orientation in the same vector was used as a control plasmid (pCDK5-I). Both plasmids were used to transform a yeast strain deleted for the endogenous PHO85 gene (pho85Δ, BY391), and complementation of various pho85 mutant phenotypes was assessed.

When complexed with the Pho80 cyclin, Pho85 phosphorylates and inhibits a transcription factor, Pho4, that is required for induction of acid phosphatase gene expression in response to low phosphate (reviewed in ref. 14). To ask whether Cdk5 can complement the defect in phosphate metabolism seen in a pho85 deletion strain, the pho85Δ cells transformed with pCDK5 or the control vector were cultured in medium with either high inorganic phosphate (7.4 mM) or low phosphate (3.7 μM) and tested for APase activity. As expected, when Pho85 was present, APase expression was repressed in high Pi medium and induced 30-fold in low phosphate medium (Fig. 1A, wt). In the absence of PHO85, APase activity remained high and was insensitive to changes in the level of extracellular phosphate (Fig. 1A, pCDK5-I p230v). Expression of CDK5 in the pho85 strain caused a significant reduction in APase activity in high-phosphate medium (Fig. 1A, pCDK5 p230v). The regulatory response to changes in phosphate was restored to almost wild-type levels by overexpressing the PHO80 cyclin along with CDK5 (Fig. 1A, pCDK5 pPho80). Importantly, APase activity can still be derepressed in low-phosphate medium in pho85 deletion cells expressing Cdk5. We conclude that Cdk5 can functionally substitute for Pho85 to promote phosphorylation of Pho4. Our data suggest that Pho4 phosphorylation is dependent on Pho80-Cdk5 complexes and that these complexes remain sensitive to signals normally interpreted by the Pho80-Pho85 kinase.

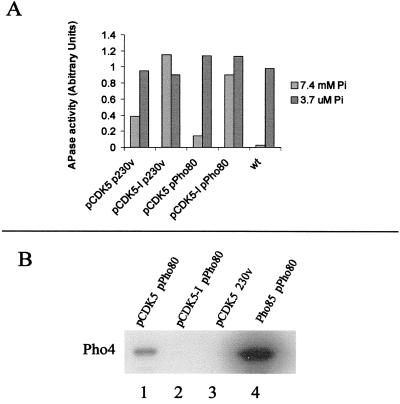

Figure 1.

Biochemical and genetic complementation of the acid phosphatase regulation defect in a pho85Δ mutant by Cdk5 expression. (A) Complementation of defect in acid phosphatase regulation. Acid phosphatase activity was measured in pho85Δ strains containing pCDK5 or pCDK5-I and a PHO80 expression plasmid (pPho80) or a control vector (p230v). Acid phosphatase activity from a wild-type strain is also shown (wt). These strains were grown in repressed (7.4 mM phosphate, shaded bars) and derepressed (3.7 μM phosphate, solid bars) conditions. Values are normalized for cell density (OD600). (B) Pho4 kinase assays with HA-Pho80-Cdk5. HA-Pho80 was immunoprecipitated from yeast extracts and used in kinase assays with Pho4 as substrate. The following strains were used for extract preparation: lane 1, pho85Δ transformed with pCDK5 and pHA-Pho80; lane 2, pho85Δ strain with pCDK5-I and pPho80; lane 3, pho85Δ strain with pCDK5 and pBA230v; lane 4, wild-type strain with pHA-Pho80 (positive control).

We next tested the ability of CDK5 to rescue pho85 mutant phenotypes thought to reflect the requirement for PHO85 in actin cytoskeleton regulation and stress response (11). We used a plating assay to compare the growth of wild-type (BY263) and pho85 deletion strains (BY391) transformed with either the CDK5 expression vector or the control plasmid (pCDK5-I) in the presence of high salt. Transformants were grown in galactose-containing medium to activate CDK5 expression and plated on medium containing 0.75M NaCl. As reported previously (11), wild-type cells were able to form colonies on the salt-containing medium, whereas the pho85 deletion strain carrying the control vector failed to grow (Fig. 2A, pho85, CDK5-I). In contrast, the pho85Δ cells expressing CDK5 formed visible colonies after 5 days of incubation at standard growth temperatures (Fig. 2A, pho85, CDK5).

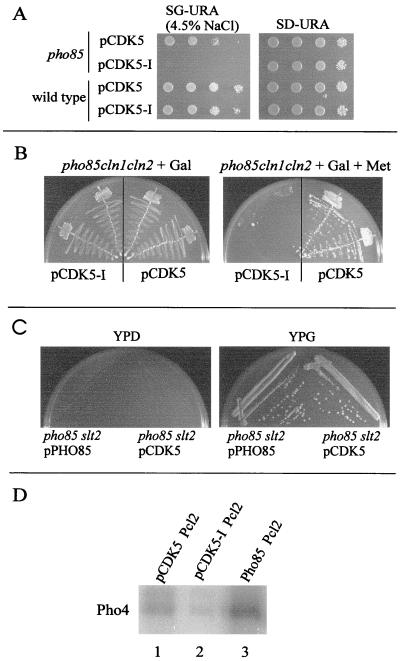

Figure 2.

Complementation of cell stress, polarity, and cell cycle phenotypes in a pho85Δ strain by CDK5 expression. (A) Salt sensitivity. Serial dilutions of log phase cultures of pho85 or wild-type cells expressing either CDK5 or CDK5-I plasmids were plated on SG-URA medium with 0.75 M NaCl or on an SD-URA plate (control) and incubated for 5 days at 30°C. (B) Overexpression of CDK5 in a cln1Δ cln2Δ pho85Δ strain. A cln1Δ cln2Δ pho85Δ strain carrying a pho85 mutant allele (pho85ts17) expressed from the MET25 promoter (BY794) and either pCDK5 (right side of plates) or pCDK5-I (left side of plates) was streaked on a galactose-containing plate plus methionine (+ Gal + Met, Right; repress pho85ts17, induce CDK5) or a galactose-containing plate minus methionine (control, Left) and incubated for 5 days at 30°C. Two independent isolates are shown. (C) Overexpression of CDK5 in a slt2Δ pho85Δ strain. A slt2Δ pho85Δ strain expressing either PHO85 (left side of plates) or CDK5 (right side of plates) from the GAL promoter was streaked onto a yeast extract/peptone/dextrose (YPD) or yeast extract/peptone/galactose (YPG) plate as indicated and incubated for 5 days at 25°C. (D) Pho4 kinase activity associated with HA-Pcl2-Cdk5. Ha-Pcl2 was immunoprecipitated from yeast extracts and used in kinase assays with Pho4 as a substrate. The following strains were used for extract preparation: lane 1, pho85Δ HA-PCL2 with pCDK5; lane 2, pho85Δ HA-PCL2 with pCDK5-I; lane 3, pho85Δ HA-PCL2 with pPHO85 (positive control).

PHO85 is required for G1 progression in the absence of the Cdc28 cyclins, CLN1 and CLN2 (13, 16). We tested the ability of Cdk5 to rescue the cell cycle arrest phenotype of a strain deleted for CLN1, CLN2, and PHO85 (BY794). The inviability of the cln1 cln2 pho85 strain was obviated by expression of a partially defective pho85 allele (pho85ts17). When expression of the PHO85 allele was repressed (in 2 mM methionine), strain BY794 arrested in G1 phase (data not shown and ref. 12). To test for complementation of the cell cycle arrest phenotype by CDK5, BY794 transformants harboring either the CDK5 expression plasmid or the control plasmid were plated on medium containing methionine and galactose to repress expression of the PHO85 allele but allow expression of CDK5. On this medium, transformants expressing CDK5, but not the control plasmid, were able to form colonies (Fig. 2B Right). Thus, CDK5 is able to complement a pho85 deletion strain for the G1 progression seen in strains deleted for other G1 regulators.

We next examined the ability of CDK5 to complement a third pho85Δ defect that may reflect a role for Pho85 in G1 phase progression. Slt2 (Mpk1) is a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase homologue that lies downstream of protein kinase C (PKC1). The PKC-Slt2 pathway is required for maintenance of cell structural integrity during polarized cell growth and is implicated in cell cycle progression during G1 phase (see ref. 26 for review). Our previous work showed that overexpression of the PHO85 cyclins PCL1 and PCL2 suppressed multiple phenotypes associated with deletion of Slt2 (20). We now have found a second genetic relationship between Slt2 and Pho85; although both pho85 and slt2 strains are viable at normal growth temperatures, a slt2 pho85 double mutant is inviable (Fig. 2C, YPD plate). The inviability of the slt2Δ pho85Δ mutant was complemented effectively by expression of either PHO85 or CDK5 from the inducible GAL promoter (Fig. 2C, YPG plate). We conclude that CDK5 is able to complement a pho85 deletion strain for several phenotypes thought to reflect defects in cell morphogenesis and polarity.

Pho85 also functions as a glycogen synthase (Gsy2) kinase when complexed with two related cyclins, Pcl8 and Pcl10; the ability of Pho85 to function as a Gsy2 kinase is highly specific to the Pcl8/10 forms of the enzyme (15). Expression of CDK5 in the pho85 mutant failed to complement the glycogen hyperaccumulation phenotype (data not shown). Our complementation data show that CDK5 can substitute for most functions of Pho85 in vivo; functional complementation of the pho85Δ by Cdk5 may reflect the ability of Cdk5 to interact with only a subset of Pho85 cyclins in yeast.

Activation of Cdk5 Kinase Activity by Pho85 Cyclins in Yeast.

Our complementation tests suggested that Pho85 cyclins can activate Cdk5 toward relevant Pho85 substrates in yeast cells. To confirm the association of Cdk5 and Pho85 cyclins in yeast, cell extracts were made from pho85Δ transformants coexpressing CDK5 with one of the HA-tagged Pho85 cyclins, HA-Pho80 or HA-Pcl2. Association of Cdk5 and Pho80 or Pcl2 was assessed in two ways. First, Cdk5 was immunoprecipitated from yeast extracts with anti-Cdk5 antibodies, and coimmunoprecipitation of HA-Pho80 subsequently was detected by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies (data not shown). Second, an immunoprecipitation-kinase assay was performed by incubation of the Cdk5 immunoprecipitates with radiolabeled ATP and purified Pho4 as a substrate; the Pho4 protein is phosphorylated by both the Pho80-Pho85 and Pcl2-Pho85 kinases in vitro (12, 21). Both HA-Pho80-Cdk5 and HA-Pcl2-Cdk5 showed substantial kinase activity toward Pho4 in vitro (Figs. 1A, lane 1, and 2D, lane 1), although lower amounts of Pho4-directed kinase activity were recovered from Pho80-Cdk5 and Pcl2-Cdk5 immunoprecipitates relative to the comparable Pho85 complexes (Figs. 1A, lanes 1 and 2, and 2D, lanes 1 and 3). The kinase activity required both Cdk5 and either HA-Pho80 or HA-Pcl2. These data show that Cdk5 can be activated by association with Pho85 cyclins in yeast extracts.

Effect of Coexpression of CDK5 and Its Mammalian Activator p35 in Yeast.

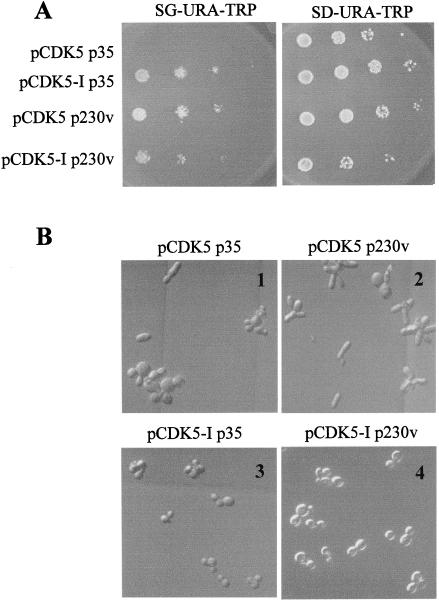

Unlike Pho85, which associates with multiple cyclins, Cdk5 has been shown to be activated only by p35 or its homologue p39. Because p35 shows no obvious sequence similarity to Pho85 cyclins, we decided to ask whether the ability of Cdk5 to complement pho85 mutant defects could be enhanced by coexpression of p35 in yeast. A p35 expression plasmid was used to transform a pho85 deletion strain expressing CDK5 from the GAL promoter. Surprisingly, we found that coexpression of p35 and Cdk5 caused a dramatic growth inhibition (Fig. 3A, pCDK5 p35, SG-URA-TRP plate), with arrest occurring throughout the cell cycle (data not shown). We also examined the morphology of yeast cells expressing either p35 or Cdk5 or coexpressing both proteins. Expression of p35 in either pho85Δ or wild-type cells caused no obvious growth phenotype or morphological abnormalities (Fig. 3B, 3; not shown for wild-type). By contrast, expression of either Cdk5 or both p35 and Cdk5 caused dramatic morphological abnormalities, with many elongated cells in the culture (Fig. 3B, 1 and 2). The elongated cell defect does not account for the growth arrest phenotype of cells expressing both p35 and Cdk5 because cells expressing Cdk5 alone showed a high percentage of elongated cells but had no significant growth defect (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of Cdk5 and p35 overexpression in pho85Δ cells. (A) Growth arrest caused by coexpression of Cdk5 and p35. pho85Δ strains transformed with pCDK5 or pCDK5-I with either a plasmid expressing p35 (p35) or an empty vector (230v) were grown in SD medium, serially diluted, and plated on glucose (SD-URA-TRP, Right) or galactose (SG-URA-TRP, Left) medium. (B) Morphology of pho85Δ cells overexpressing Cdk5 and p35. Cells were grown in raffinose-containing medium (noninducing) to an OD600 of ≈0.1, and then galactose was added to a final concentration of 2% to induce expression of CDK5 and p35. Cells were cultured for 24 hr and viewed at ×630 magnification and photographed. 1, pCDK5 + p35; 2, pCDK5 + vector; 3, pCDK5-I + p35; 4, pCDK5-I + vector.

Activation of Pho85 in COS-7 and Insect Cells by Cdk5 Activators.

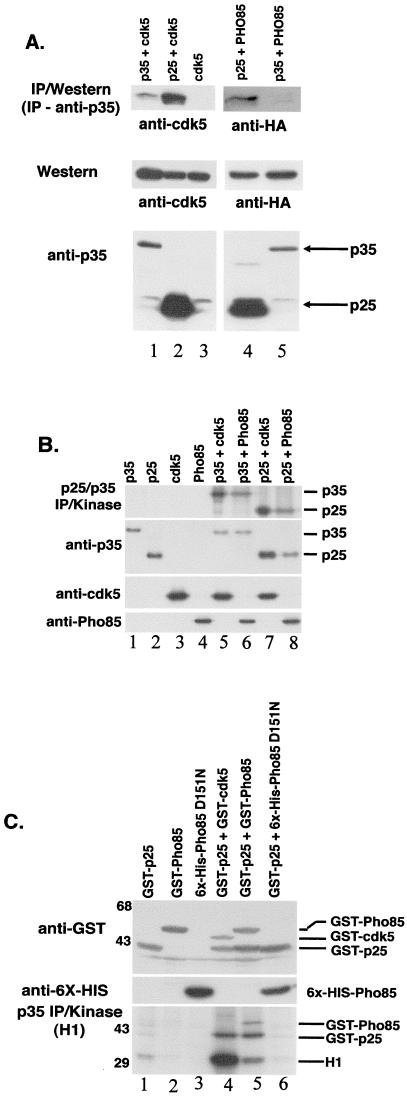

Our yeast experiments showed that Cdk5 can functionally substitute for Pho85 and that Cdk5 can be activated by Pho85 cyclins in vivo. We next sought to test for functional activation of Pho85 by Cdk5 activator proteins in mammalian cells. We expressed an HA-tagged version of Pho85 in COS-7 cells that were cotransfected with vectors expressing either p35 or p25, an amino-terminally truncated derivative of p35. A more robust interaction between Pho85 and p25 might be expected because p25 represents a highly stabilized form of p35 and still contains the binding and activation domains of p35 (27). Western blotting with anti-Cdk5, anti-p35, and anti-HA antibodies was used to visualize levels of the expressed proteins in the transfectants (Fig. 4A Middle and Bottom). p25/p35 was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts made from the various transfectants; immunoblotting with anti-HA antiserum revealed that comparable amounts of Pho85 and Cdk5 could be coimmunoprecipitated with p25 from transfected cell extracts (Fig. 4A). As for Cdk5, a small amount of Pho85 also could be detected in a p35 immunoprecipitation reaction. The association between p25/p35 and Pho85 was detected only when p25 or p35 also was transfected (data not shown). To ask whether the association of Pho85 with p25 or p35 resulted in an active Cdk complex, we performed kinase assays on the p25-Pho85 and p35-Pho85 immunoprecipitates. Pho85 phosphorylated both p25 and p35 in the immunoprecipitation reaction and was as effective as Cdk5 in this assay (Fig. 4B); the kinase activity was dependent on transfection of both the activator (p35 or p25) and the Cdk (Pho85 or cdk5, Fig. 4B). Together, these data show that Pho85 can associate with and phosphorylate both p35 and p25 in mammalian cells.

Figure 4.

Activators of Cdk5 bind and activate Pho85 in mammalian and insect cells. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of p35/p25 with Pho85. p35 antibodies were used to generate immunoprecipitates from lysates of COS-7 cells that had been transiently transfected with various combinations of CMV-p35, CMV-p25, CMV-cdk5, and CMV-HA-PHO85 as indicated at the top. Immunoblots were reacted by blotting with either anti-cdk5 (DC17) antibodies (Left) or anti-HA (12CA5) antibodies to detect HA-Pho85 (Right). Lanes: 1, p35+cdk5; 2, p25+cdk5; 3, cdk5 alone; 4, p25+PHO85; 5, p35+PHO85. Levels of Cdk5, HA-Pho85, and p25/35 expression in the extracts used in the immunoprecipitation reactions are shown (Middle and Bottom). (B) Phosphorylation of p25 and p35 by Pho85. Immunoprecipitation-kinase reactions were performed with anti-p35 antibodies by using lysates from COS-7 cells transfected with the following vector combinations: lane 1, CMV-p35; lane 2, CMV-p25; lane 3, CMV-cdk5; lane 4, CMV-HA-Pho85; lane 5, p35+cdk5; lane 6, p35+Pho85; lane 7, p25+cdk5; lane 8, p25+Pho85. The positions of migration of phosphorylated p35 and p25 are shown to the right. Levels of protein expression were confirmed by Western blotting with anti-p35, anti-cdk5, or anti-HA (Pho85) antibodies as indicated to the left. (C) Activation of Pho85 by p25 in insect cells. Lysates from Hi5 insect cells infected with baculoviral vectors expressing various combinations of GST-p25, GST-Pho85, 6XHis-Pho85D151N, and GST-Cdk5 were incubated with glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose beads to pull down the GST-tagged proteins. Kinase reactions were performed on the GSH precipitates with Histone H1 as substrate. The following proteins were present in the lysates: lane 1, GST-p25; lane 2, GST-Pho85; lane 3, 6XHis-Pho85D151N; lane 4, GST-p25+GST-cdk5; lane 5, GST-p25+GST-Pho85; lane 6, GST-p25+6XHis-Pho85D151N. The positions of migration of phosphorylated GST-Pho85, GST-p25, and Histone H1 (H1) are indicated to the right. Levels of protein expression in the lysates are shown by anti-6X-HIS Western blotting (Middle, to detect the Pho85D151N protein) and anti-GST blotting (Top).

We also studied the association of p25 and Pho85 by using baculoviral expression in cultured insect cells. Baculoviral vectors expressing GST fusions to p25 and Pho85 were used to coinfect insect cells. Consistent with our COS cell transfection experiment, a p25-Pho85 complex was detected in lysates from the infected insect cells by coimmunoprecipitation with anti-p35 antiserum (data not shown). We used glutathione-Sepharose beads to purify the p25-Pho85 complex and assayed the kinase activity by using a known in vitro Cdk5 substrate, Histone H1. When GST-Pho85 was expressed alone in insect cells, no phosphorylation of Histone H1 or GST-Pho85 was seen in the immunoprecipitation-kinase reaction (Fig. 4C, lane 2). Likewise, GST-p25 is associated with only small amounts of Histone H1 kinase activity when expressed alone (Fig. 4C, lane 1). When GST-Pho85 was coexpressed with GST-p25, phosphorylation of Histone H1, GST-p25, and GST-Pho85 was seen in the kinase reaction (Fig. 4C, lane 5). No kinase activity was associated with the p25-Pho85 complexes when a kinase-dead allele of Pho85 was coexpressed with GST-p25 (Fig. 4C, lane 6). We conclude that Pho85 can be activated by association with the Cdk5 activator, p25/35, to phosphorylate substrates normally phosphorylated by Cdk5 in vitro.

Discussion

We have made two sets of observations that lead us to propose that mammalian Cdk5 and budding yeast Pho85 are functional homologues. First, Cdk5 can interact with Pcls in yeast cells to form functional Pcl-Cdk5 complexes that complement many defects associated with deletion of PHO85. Second, Pho85 can interact with the Cdk5 activators p35 and p25 in mammalian or insect cells; when bound to Cdk5 activators, Pho85 phosphorylated proteins that are known substrates of p25/35-Cdk5 in vitro. Despite the high conservation of the Cdk family, the biochemical and genetic complementation that we observe appears specific to Cdk5 and Pho85 and their activators. Neither the endogenous CDC28 gene nor overexpression of CDC28 can functionally compensate for the absence of Pho85 in yeast (ref. 28; D.H. and B.A., unpublished data). Expression of CDK5 fails to rescue a CDC28 deficiency in yeast, although expression of other mammalian Cdks will complement a cdc28 mutant phenotype (22). Likewise, other mammalian Cdks (Cdk2) cannot form functional complexes with p35/25 in mammalian cells (29).

Our complementation assays in yeast show that Cdk5 can be activated by Pho85 cyclins to form active kinase complexes that respond to signals normally sensed by the Pho85 Cdk. When yeast cells are grown in phosphate-rich medium, the Pho4 transcription factor is phosphorylated by the Pho80-Pho85 and is predominantly cytoplasmic, thus preventing expression of acid phosphatase genes (reviewed in ref. 14). Phosphate-dependent regulation of Pho80-Pho85 requires the Cdk inhibitor, Pho81. Like the p16INK4 family of mammalian Cdk inhibitors, Pho81 contains several copies of the ankyrin motif, which are required for the inhibitory activity of the protein in vitro (30). When complexed with the Pho80 cyclin, Cdk5 not only allowed significant repression of APase activity in high-phosphate but also promoted derepression in low-phosphate medium. These results imply that, like the Pho80-Pho85 kinase, the Pho80-Cdk5 kinase can respond to the inhibitory effect of Pho81. Perhaps proteins similar to Pho81 may function to regulate the activity of Cdk5 in mammalian cells.

Although there is no primary sequence similarity between p35 and other cyclins, the predicted tertiary structure of p35 is similar to cyclins and it may activate Cdk5 by a comparable mechanism (31, 32). Consistent with a cyclin-like mechanism for p25/35, we found that Pho85 and Cdk5 can be activated by either Pcls or p25/p35. Activation of Pho85 and Cdk5 appears specific to the Pcl/p35-type proteins. There is no evidence that Pho85 can be activated by other cyclins (16), and Cdk5 cannot be activated by cyclins A, E, or D, although binding of Cdk5 to D-type cyclins can be detected (reviewed in ref. 2). Together, these results allow p25/p35 to be classified functionally as a Pcl-type cyclin. The specificity of p35/Pcl for activation of Pho85 and Cdk5 suggests that Pho85 and Cdk5 may share common regulatory features. For example, some cyclin-Cdk complexes, such as human cyclin B-Cdc2 and yeast Cdc28 kinases, require phosphorylation at a conserved residue in the so-called T loop of the kinase for full activity (reviewed in ref. 1). In contrast, p35-Cdk5 and Pho85 kinases do not require T loop phosphorylation for activity (ref. 33; M. Donoviel, D.H., and B.A., unpublished data).

As discussed above, the ability of Cdk5 to complement pho85 mutant phenotypes in yeast suggests that, when activated by Pho85 cyclins, Cdk5 is able to recognize and phosphorylate bona fide Pho85 substrates in vivo. Likewise, when Pho85 is activated by p25 after coexpression in insect cells, it acquires the ability to phosphorylate the Cdk5 substrates, Histone H1 and p25. These observations support a substrate-targeting role for p35 and the Pho85 cyclins, consistent with previous work on Pho85 and other Cdks (15). Although Cdk5 rescued pho85 mutant phenotypes when expressed alone or with Pho85 cyclins in yeast, coexpression of CDK5 with its mammalian activator protein p35 caused inviability in a pho85Δ strain. We suggest that, without p35, Cdk5 is bound and activated by Pho85 cyclins, which then direct Cdk5 to Pho85 substrates, allowing functional complementation of the pho85Δ strain. When p35 is also expressed in yeast, Cdk5 may preferentially interact with p35 but the p35-Cdk5 complex may be unable to phosphorylate relevant Pho85 substrates. Pho85 substrates or other proteins may be inappropriately sequestered or targeted by the p35-Cdk5 kinase in yeast, causing the morphological and cell growth defects that we observed.

What proteins might be misregulated in yeast cells expressing p35-Cdk5-altered Cdk5/Pho85 kinases? Like Cdk5, Pho85 is involved in regulating the actin cytoskeleton, and the altered kinases may be sequestering Pho85 target proteins that normally are required for proper actin regulation during G1 progression. The G1-specific forms of Pho85 contribute to actin regulation through interaction with the Rvs167 protein. Two mammalian homologues of Rvs167, amphiphysin I and II, are involved in endocytosis at nerve termini and bind to proteins required for endocytosis such as dynamin and clathrin (34). There are several functional parallels between amphiphysins and yeast Rvs167. Depletion of amphiphysin I by using antisense oligonucleotides leads to growth cone collapse and defects in endocytosis in neurons, and deletion of rvs167 causes morphological and endocytotic defects in yeast (11, 35). Like Cdk5, amphiphysin I has been implicated in interactions with actin and actin-binding proteins to promote cytoskeletal polarization during neurite outgrowth (reviewed in ref. 34). Pho85 and Rvs167 are also required for proper actin cytoskeletal regulation during polarized bud growth in yeast (11, 35). Finally, protein complex formation involving amphiphysin I is regulated by phosphorylation (36), and protein complexes involving Rvs167 may be regulated by Pho85-dependent phosphorylation (11, 17). Thus, after the Pho85-Rvs167 paradigm, amphiphysins are putative targets for Cdk5 in neuronal cells. Together, our observations lead us to propose the existence of a functionally conserved regulatory pathway, involving Pho85/Cdk5 and their targets, that regulates the actin cytoskeleton in response to regulatory stimuli. Given the functional homology of Cdk5 and Pho85, studies of Pho85 and Cdk5 function in yeast and neuronal cells are likely to be mutually informative.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Colwill and Helena Friesen for comments on the manuscript and Carol Hoover for technical help. D.H. is a Research Fellow of the National Cancer Institute of Canada and is supported by funds provided by the Terry Fox Run. J.M. holds a Doctoral Award from the Medical Research Council of Canada and G.P. is a Ryan Fellow. This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute of Canada, with funds from the Canadian Cancer Society (to B.A.) and grants from the National Institutes of Health (to L.-H.T.). B.A. is a Scientist of the Medical Research Council of Canada, and L.-H.T. is an assistant investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a Rita Allen Foundation Scholar, and a recipient of an Ester A. and Joseph Klingenstein Fund.

Abbreviations

- Cdk

cyclin-dependent kinase

- Pcl

Pho85 cyclin

- HA

hemagglutinin

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Morgan D O. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao C Y, Zelenka P S. BioEssays. 1997;19:307–315. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews B, Measday V. Trends Genet. 1998;14:66–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01322-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K-Y, Qi Z, Yu Y P, Wang J H. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:951–958. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(97)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolic M, Dudek H, Kwon Y T, Ramos Y F, Tsai L H. Genes Dev. 1996;10:816–825. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.7.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paglini G, Pigino G, Kunda P, Morfini G, Maccioni R, Quiroga S, Ferreira A, Caceres A. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9858–9869. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09858.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shuang R, Zhang L, Fletcher A, Groblewski G E, Pevsner J, Stuenkel E L. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4957–4966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsubara M, Kusubata M, Ishiguro K, Uchida T, Titani K, Taniguchi H. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21108–21113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikolic M, Chou M M, Lu W, Mayer B J, Tsai L-H. Nature (London) 1998;395:194–198. doi: 10.1038/26034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lew D J, Reed S I. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:1305–1320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.6.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J, Colwill K, Aneliunas V, Tennyson C, Moore L, Ho Y, Andrews B. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1310–1321. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Measday V, Moore L, Ogas J, Tyers M, Andrews B. Science. 1994;266:1391–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.7973731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espinoza F H, Ogas J, Herskowitz I, Morgan D O. Science. 1994;266:1388–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.7973730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenburg M E, O’Shea E K. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang D, Moffat J, Wilson W A, Moore L, Roach P J, Andrews B J. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3289–3299. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Measday V, Moore L, Retnakaran R, Lee J, Donoviel M, Neiman A, Andrews B. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1212–1223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colwill K, Field D, Moore L, Friesen J, Andrews B. Genetics. 1999;152:881–893. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wendland B, Emr S D, Reizman H. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:513–522. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longtine M S, McKenzie A, Demarini D J, Shah N G, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle J R. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madden K, Sheu Y-J, Baetz K, Andrews B, Snyder M. Science. 1997;275:1781–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaffman A, Herskowitz I, Tjian R, O’Shea E. Science. 1994;263:1153–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.8108735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyerson M, Enders G H, Wu C L, Su L K, Gorka C, Nelson C, Harlow E, Tsai L H. EMBO J. 1992;11:2909–2917. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. Genetics. 1989;12:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai L H, Takahashi T, Caviness V S J, Harlow E. Development. 1993;119:1029–1040. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.4.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirst K, Fisher F, McAndrews P C, Goding C R. EMBO J. 1994;13:5410–5420. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gustin M C, Albertyn J, Alexander M, Davenport K. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1264–1300. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1264-1300.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lew J, Huang Q-Q, Qi Z, Winkfein R J, Aebersold R, Hunt T, Wang J H. Nature (London) 1994;371:423–426. doi: 10.1038/371423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santos R C, Waters N C, Creasy C L, Bergman L W. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5482–5491. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai L H, Delalle I, Caviness V S J, Chai T, Harlow E. Nature (London) 1994;371:419–423. doi: 10.1038/371419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider K R, Smith R L, O’Shea E K. Science. 1994;266:122–126. doi: 10.1126/science.7939631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang D, Chun A C S, Zhang M, Wang J H. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12318–12327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown N R, Noble M E M, Endicott J A, Garman E F, Wakatsuki S, Mitchell E, Rasmussen B, Hunt T, Johnson L N. Structure. 1995;3:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi Z, Huang Q Q, Lee K Y, Wang J H. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10847–10854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wigge P, McMahon H T. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauer F, Urdaci M, Aigle M, Crouzet M. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5070–5084. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.5070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slepnev V I, Ochoa G C, Butler M H, Grabs D, deCamilli P D. Science. 1998;281:821–824. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]