Abstract

Objective: To assess primary care provider (PCP) attitudes and self-reported behavior with regard to identifying and managing depression in adult patients before and after a chronic disease/collaborative care intervention.

Method: A self-administered cross-sectional survey was conducted in 6 targeted practices among 39 family practice physicians, family nurse practitioners, and residents before and after implementation of a depression in primary care project. In this project, the sites received tools and training in depression screening and guideline-concordant treatment, facilitated referral services for patients to access mental health providers, psychiatric phone consultation, patient education materials, and services of a depression care manager. The project was conducted from June 2003 through June 2006.

Results: Comparison of responses prior to and after the intervention showed that significantly or nearly significantly larger proportions of PCPs endorsed the importance of depression as a patient presenting problem (p = .000), increased provision of supportive counseling (p = .13), more often identified counseling or therapy as effective (p = .07), and more often referred patients to mental health services (p = .001). PCPs also reduced their perception that treating depression is time consuming (p = .000).

Conclusions: After a chronic disease/collaborative care approach to depression treatment in primary care was implemented, PCP attitudes and behaviors about depression treatment were significantly modified. More guideline-concordant care, and increased collaboration with mental health services, was reported. Implications for future primary care depression intervention activities and research are discussed.

Over a decade has passed since the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research issued guidelines about treatment of depression.1 Major depressive disorder has been identified as an important contributor to overall population disability, a significant complication in treating other chronic medical illness, and highly costly in terms of both direct and indirect medical and social costs.2 While most patients receive their only depression care in primary care settings, studies have shown that half go unrecognized or untreated, and those treated rarely receive guideline-concordant care.3–6 In addition, while patients with chronic conditions prefer to receive services in primary care,7 those with depression and other mental health disorders are more likely to have unmet expectations about their medical care, and providers are more likely to find them frustrating patients to care for.5

Studies of primary care depression treatment suggest that multifaceted intervention is likely to be more effective in improving patient outcomes and satisfaction compared to usual care, placebo, or no treatment.6,8–11 Such interventions implement a system of changes, including screening and identification protocols, guidelines for psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, provision of mental health consultation, and often a patient care coordinator or care manager.12–14 However, it has been difficult to replicate and sustain improvements in depression care in real world settings.15 Part of that challenge is to understand the views and beliefs of primary care providers (PCPs) about depression treatment and to determine barriers and targets for practice change specific to different clinical settings.16

This article reports results of a PCP survey conducted among Massachusetts Consortium on Depression in Primary Care (MCDPC) practice settings. The MCDPC was one of 8 intervention sites for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Depression in Primary Care Incentives Grants.17–20 The goal of these grants was to establish sustainable economic and systems changes to improve the treatment of depression in primary care. The MCDPC worked exclusively with Medicaid health plans to implement a chronic care model of depression management among adult Medicaid enrollees in a sample of primary care practices.

METHOD

Six practice sites were involved, including a community health center, 2 hospital-owned outpatient clinics (1 with a family practice residency program), a resident-only internal medicine clinic, and 2 small group family practices. These sites received tools and training in depression screening and guideline-concordant treatment and facilitated referral services for patients to access mental health providers, psychiatric phone consultation, patient education materials, and services of a depression care manager. Collaboration with mental health management organizations and preferred mental health providers involved monitoring of access by patients to mental health services and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant information sharing about patient care. The care manager provided patient phone and inperson contacts including medication monitoring, self-management support, and referral and support to follow through for mental health and other services. The care manager maintained communication with the PCP and enlisted the PCP in all treatment decisions.19

Prior to intervention implementation, a sample of PCPs at each site were asked to complete an anonymous survey that included 4 subscales addressing (1) attitudes about the prevalence of depression and effectiveness of depression treatment in primary care; (2) a rating of their skills in recognizing and treating depression; (3) a rating of the specific behaviors they implemented in their depression treatment (e.g., prescribing medication, referring to mental health services, entering the diagnosis in the chart); and (4) ratings of satisfaction, compensation, and adequacy of time to treat depression. After approximately 2 years of implementation, a follow-up survey was distributed to the same sites.

A total of 23 PCPs completed the preintervention survey, and 24 completed the postintervention survey (only 8 completed the survey at both time points due to staff turnover). Analysis was thus conducted as if each time point was an independent cross-sectional survey. To check if differences found between the 2 samples could be due to sampling bias, and not actual change in responses, separate analyses were conducted for the 8 respondents who participated at both time points to determine if the patterns of differences were similar. Analysis included basic frequencies and χ2 tests. Because of limited power and small sample size, results p ≤ .2 were examined as trends. The total response rate at each time point represents approximately 65% of all eligible PCPs. The institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School approved the study, and the project was conducted from June 2003 through June 2006.

RESULTS

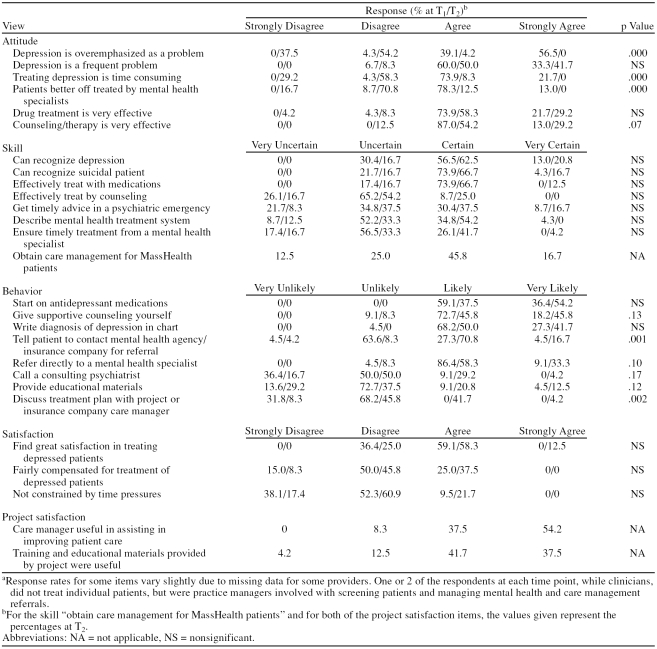

Overall, 39 PCPs participated at one of the time points. The majority (29) were family practice M.D.s, while 3 were family nurse practitioners and 7 were residents (5 family practice and 2 internal medicine); 61% (N = 24) were female. Distributions of the PCP responses for 10 of the 25 items were found to be significantly or nearly significantly different prior to the depression intervention versus postintervention (Table 1). PCPs after intervention more “strongly disagreed” or “disagreed” that depression is an overemphasized problem (91.6% [N = 22] postintervention vs. 4% [N = 1] preintervention) and more “strongly disagreed” or “disagreed” that depression treatment is time consuming (87.5% [N = 21] postintervention vs. 4% [N = 1] pre-intervention). They also were less likely to “agree” or “strongly agree” that patients were better off being treated by mental health specialists (12% [N = 3] post-intervention vs. 91% [N = 21] preintervention).

Table 1.

Comparison of Primary Care Provider Views About Depression Treatment Before and After a Collaborative Care Intervention (T1: N = 23, T2: N = 24)a

Substantial differences, 2 reaching significance and 4 others trending to significance, were found on 6 of the 8 items about PCP practice behaviors. In response to the item, “Tell the patient to contact his/her community mental health agency or insurance company for a referral to a mental health specialist,” 87.5% (N = 21) of the respondents reported being “likely” or “very likely” to tell the patient to obtain a mental health referral post-intervention, compared to 31.8% (N = 7) at baseline (p = .001), while one third (N = 8) versus 9% (N = 2) were “very likely” to refer directly to a mental health specialist (p = .10). In addition, 45.9% (N = 11) postintervention versus 0% at baseline were “likely” or “very likely” to discuss a patient's depression treatment plan with a care coordinator; p = .002 (at follow-up, this included the project-funded care manager). PCPs were also much more likely postintervention to provide supportive counseling themselves (45.8% [N = 11] “very likely” vs. 18.2% [N = 4] at baseline), provide educational materials (33.3% [N = 8] “likely” or “very likely” vs. 13.6% [N = 3] at baseline), or use a psychiatric consultant (33.4% [N = 8] “likely” or “very likely” vs. 9.1% [N = 2] at baseline).

Finally, while the difference was not significant, more PCPs (90.4% [N = 19]) “strongly disagreed” or “disagreed” that they were not constrained by time pressures in treating depression prior to the intervention compared to 78.3% (N = 18) postintervention. Analysis of the small group of matched responses (N = 8) revealed the same pattern of significant changes, suggesting that the results reflected changed attitudes and behaviors, and not simply different samples of providers.

DISCUSSION

While limited in terms of design and power, our findings tell us that a number of attitudes of PCPs, and their self-reported practice behaviors, changed substantially after implementation of a comprehensive primary care depression treatment improvement intervention. Differences between baseline and postintervention responses were consistent when the 2 samples were examined independently and when the small group of PCPs who participated at both data collection time points was examined. This leads us to conclude that the responses reflect true differences in attitudes and behaviors, not just sampling bias between the 2 time points. Further, the reasons for substantial staff turnover at the sites during the 2-year period appeared to be unrelated to the intervention (pregnancy leaves, retirements, job changes due to family circumstances, graduation of third-year residents, etc.).

The intervention involved (1) PCP training on depression symptoms, screening and monitoring tools, and medication management; (2) provision of a depression care manager to support patients and PCPs; (3) telephone access to a consulting psychiatrist; and (4) improved access to mental health referrals for patients. In addition, ongoing problem-solving/academic detailing support was offered to each practice site. The intervention resulted in improved attitudes of PCPs toward the significance of depression in primary care, more acceptance of the PCP role in treating depression, and more willingness to provide both personal counseling and referral of patients to mental health services. Importantly, despite a common concern of PCPs that depression treatment is too time consuming,18 the data show that PCPs postintervention significantly disagreed that depression care is time consuming or that time pressures constrained their ability to treat depression. On the basis of written comments by respondents to the open-ended part of the survey, we concluded that the primary reason PCPs found depression care less burdensome was that a care manager was provided to assist with patient management and mental health referrals.

Importantly, the intervention appeared to assist PCPs in changing actual practice behaviors (e.g., providing counseling, referring to mental health services, providing educational materials, using a care manager), although only slightly more PCPs reported using antidepressant medications or writing the diagnosis in the chart. It is also puzzling that there was no detectible change in PCP report of skills about recognizing depression or recognizing suicide risk. A major emphasis of the intervention was to provide a standard screening tool, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),21 to assist with diagnosis and monitoring of patient improvement. In addition, explicit training and written materials on assessing and handling suicide risk were provided. Further, some PCPs specifically commented on the usefulness of the PHQ-9 tool in assessing patients and reported using the PHQ-9 for patients beyond the targeted intervention group. This lack of reported change in skills may be due to social response bias inherent in self-reporting one's clinical skills. Focus groups conducted in the planning stages of the project, however, also confirmed that PCPs feel they have a good handle on how to detect depression in their patients, and they were not very enthusiastic about adopting a standard tool.18 Nevertheless, use of the PHQ-9 in our intervention also seemed to assist communication among the PCPs, the care manager, and mental health providers because it provided a quick summary of the severity and type of patient symptoms.

Overall, the patterns of change in this study suggest that PCPs gained a greater appreciation for their own role in depression care management and at the same time truly embraced a collaborative care model in which use of mental health consultation and referrals increased. Importantly, the focus on enabling PCPs to screen for and manage depression within the context of a chronic disease/collaborative model was not perceived as overly burdensome. In fact, PCPs noted improvements in perceptions about how much time depression care takes. That this was due primarily to the use of a depression care manager to support the PCPs and patients has important implications for organizing and financing primary care depression treatment. Future studies require documentation of the cost effectiveness of using such physician extenders in routine care.

Further, in the current medical care environment of limited resources, future studies may want to identify which components of the collaborative care model itself, or implementation approaches for supporting the intervention in the field, relate most strongly to the improvements in attitude and self-reported behavior among participating providers. Prior work6,8–11 has demonstrated that implementation of only pieces of the collaborative care model does not result in significant improvements in patient management, but there is a need for more evidence about which combinations of intervention activities and which types of implementation assistance are needed to sustain successful experimental interventions.16

Our findings provide strong support for further dissemination and institutionalization of a chronic care/collaborative model for depression management in primary care. This model appears to garner strong PCP acceptance, and increased collaboration with mental health services, on behalf of patients who typically do not access, or are reluctant to access, mental health systems. While analysis of patient outcomes was beyond the scope of this article, continued effort to document patient outcomes and satisfaction will also be necessary to demonstrate how the collaborative care model improves efficiency and quality of primary care treatment of depression.

Footnotes

The study was supported by grant 048172 from the Depression in Primary Care Initiative, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors acknowledge the work of Gail Sawosik, M.B.A., Project Coordinator, and Deborah Ruth Mockrin, L.I.C.S.W., Care Manager, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Massachusetts Medical School, both of whom assisted with data collection and practice detailing. Mss. Sawosik and Mockrin report no conflicts of interest regarding the information presented in this study. The authors also thank the participating practice sites (all located in Massachusetts): Benedict Family Medicine, Hahnemann Family Health Center, Holyoke Community Health Center, Lincoln Primary Care Clinic, Lincoln St. Family Medicine, and Shrewsbury Family Medicine.

The authors have no potential, perceived, or real conflicts of interest regarding the information presented in this study.

REFERENCES

- Clinical Practice Guideline Number 5. Depression in Primary Care, vol 1. Detection and Diagnosis. Rockville, Md: US Dept Health Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. 1993 AHCPR Publication 93–0550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez AD. The Global Burden of Disease. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Callahan EJ, Bertakis KD, and Azari R. et al. Association of higher costs with symptoms and diagnosis of depression. J Fam Pract. 2002 51:540–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak KA, Taylor LvH, and Katzelnick DJ. et al. Antidepressant medication management and Health Plan Employer Data Information Set (HEDIS) criteria: reasons for nonadherence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63:727–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Jackson JL, Chamberlin J.. Depressive and anxiety disorders in patients presenting with physical complaints: clinical predictors and outcome. Am J Med. 1997;103:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, and Rutter C. et al. Randomized trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000 320:550–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, VonKorff M.. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Millbank Q. 1996;74:511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, and Pearson SD. et al. Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Arch Fam Med. 2000 9:345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Von Korff M, and Lin E. et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995 273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Taylor-Vaisey A, and Dietrich AJ. et al. Interventions to improve provider diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2000 41:39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Sherbourne C, and Schoenbaum M. et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care. JAMA. 2000 283:212–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulberg HC.. Treating depression in primary care practice: applications of research findings. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:535–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE.. Evidence review: efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigone MP, Gaynes BN, and Rushton JL. et al. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 1992 136:765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katon W, Unutzer J.. Collaborative care models for depression: time to move from evidence to practice. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2304–2305. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGruy FV.. A note on the partnership between psychiatry and primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1487–1489. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Rollman BL, and Schulberg HC. et al. A clinical framework for depression treatment in primary care. Psychiatr Ann. 2002 9:545–553. [Google Scholar]

- Upshur CC.. Crossing the divide: primary care and mental health integration. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2005;32:341–355. doi: 10.1007/s10488-004-1663-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belnap BH, Kuebler J, and Upshur C. et al. Challenges of implementing depression care management in the primary care setting. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006 33:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollman BL, Weinreb L, and Korsen N. et al. Implementation of guideline-based care for depression in primary care. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006 33:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB.. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]