Abstract

An efficient two-step recombination method for markerless gene deletion and insertion that can be used for repetitive genetic modification in Yersinia pestis was developed. The method combines λ Red recombination and counterselective screening (sacB gene) and can be used for genetic modification of Y. pestis to construct live attenuated vaccines.

Suicide vectors introduced by conjugation or electrotransformation have been used to generate knockout mutants in Yersinia spp. (3, 13, 18, 20). The transformation efficiency in Yersinia for these plasmids is typically low, which makes introducing mutations difficult and laborious. Thus, developing an easy and highly efficient method to generate mutations in the chromosome of Yersinia pestis would be a useful tool to facilitate research on this pathogen.

The λ Red system is a simple method for disrupting chromosomal genes using PCR products in Escherichia coli (7, 14, 15) and Salmonella enterica (12). Subsequently, Derbise et al. introduced an improvement by using long flanking sequences to disrupt genes in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (9). However, disrupting genes by either method leaves antibiotic markers (17) or FLP recombination target (FRT) site scars in the bacterial chromosome (7). Antibiotic resistance markers cannot be used when working with a select agent, such as Y. pestis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, unpublished report), or for construction of live vaccines. The presence of FRT scars, typically 82 to 85 bp in length, could become problematic if one were to use this system to introduce multiple mutations. In the standard system, each incoming PCR product encodes a selectable antibiotic resistance marker flanked by FLP sites, the source of FRT scars. Therefore, the scars could serve as recombinational hot spots at each successive step in strain construction, reducing the frequency of obtaining the desired insertion (7). Use of the Flp recombinase in a cell that carries two nearby scars could lead to an unwanted deletion of the intervening sequence (7). Finally, the presence of multiple scars in the chromosome could lead to chromosomal rearrangements or deletions resulting from recombination events between FRT scars, even in the absence of the Flp recombinase (7). This latter possibility is of concern to the FDA and could therefore hinder licensure of a live bacterial vaccine possessing multiple mutations constructed using this method.

Some researchers have successfully used suicide vectors to disrupt genes in Y. pestis (1, 18). We were unable to delete the relA and spoT genes from Y. pestis using either suicide vectors or the standard λ Red method. Here, we have combined elements of both systems to develop a highly efficient method for introducing gene deletions free of antibiotic markers and FRT scars and for markerless gene insertion.

Tables 1 and 2 list the bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotide primers used in this study. Y. pestis strains were grown in heart infusion broth (HI broth) and on plates containing HI broth, Congo red, and agar at 30°C (1). For screening, Y. pestis electroporants were spread or streaked onto Tryptose blood agar (TB agar) plates containing 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol (Cm) and/or 5% sucrose. Y. pestis was grown at 30°C for 24 h with shaking (liquid media) or for 48 h (solid media). General DNA isolation and enzymatic manipulation were performed as described previously (19). The targeted region of each of the final constructs was verified for the expected DNA sequence by PCR and DNA sequence analyses.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype or annotationa | Source, reference, or derivation |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| E. coli TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| Y. pestis strains | ||

| KIM6+ | Pgm+; pMT1 pPCP1; cured of pCD1 | 1 |

| χ10003 | ΔrelA233 | Y. pestis KIM6+ |

| χ10004 | ΔrelA233 ΔspoT85 Y. pestis KIM6+ | This study |

| χ10020 | ΔrelA233 ΔPspoT::spoT-1::TT araC PBADspoT+1 Y. pestis KIM6+ | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | For cloning and sequencing | 22 |

| pKD46 | λ Red recombinase expression plasmid | 7 |

| pKD3 | Template for amplifying the cat gene | 7 |

| pRE112 | Template for amplifying the sacB gene | 10 |

| pYA3700 | TT araC PBAD cassette plasmid; Apr | 6 |

| pYA4373 | The cat-sacB cassette was inserted in the PstI and SacI sites of pUC18 | pUC18 |

| pYA4452 | The ′gmk-rpoZ (the spoT upstream sequence from −1 to −749 bp) and spoT′ (585 bp of the N-terminal fragment of the spoT gene from the start codon TTG) were put into SphI and PstI sites and XhoI and EcoRI sites of pYA3700, respectively | pYA3700 |

| pYA4453 | The cat-sacB cassette from pYA4373 was ligated into the PstI site of pYA4452 | pYA4452 |

| pYA4566 | The ′barA-y0809-y0810-mazG′ fragments ligated by overlapping PCR and containing restriction endonuclease sites (PstI and SacI) near the center of the fragment were cloned into EcoRI and HindIII sites of pUC18 | pUC18 |

| pYA4567 | The ′barA-y0809-y0810-mazG′ fragments ligated by overlapping PCR without any exogenous intervening sequences were cloned into EcoRI and HindIII sites of pUC18 | pUC18 |

| pYA4568 | The cat-sacB cassette from pYA4373 was ligated into PstI and SacI sites of pYA4566 | pYA4566 |

TT, transcription terminator.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this work

| Oligonucleotide primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Cm-F | 5′CGCGGATCCAACTTCATTTAAATGGCGCGCCTTACG3′ (BamHI) |

| Cm-R | 5′CGAACTGCAGGGCGCGCCTACCTGTGACGGAAG3′ (PstI) |

| SacB-F | 5′CGGGGATCCGCCCTTATGTGTAAAGGGCAAAGTGTATACTTTG3′ (BamHI) |

| SacB-R | 5′CGGGAGCTCTTATTTGTTAACTGTTAATTGTCCTTG3′ (SacI) |

| relA-U1 | 5′CGGAAGCTTCATCATGCGCGCGCGAAGACTGTATTTG3′ (HindIII) |

| relA-U2 | 5′GAGCTCGGTACCAGCCTGCAGGCATGCAACTTCTCCCTACTTTGCGACCTCT3′ (SacI and PstI) |

| relA-D1 | 5′GCATGCCTGCAGGCTGGTACCGAGCTCGCTTTTTAATCTGGACGGCGATTAC3′ (PstI and SacI) |

| relA-D2 | 5′CGGGAATTCCTAATCGCATGGCAAACGTCATCAAAG3′ (EcoRI) |

| relA-U3 | 5′TCGCCGTCCAGATTAAAAAGCAACTTCTCCCTACTTTGCGACCTCTG3′ |

| relA-D3 | 5′CAGAGGTCGCAAAGTAGGGAGAAGTTGCTTTTTAATCTGGACGGCGA3′ |

| relA-V1 | 5′ATGCTCAAGTATCAGTTTATCGGCTTCCAG3′ |

| relA-V2 | 5′GTGGGGAATAACCTGAATAGTCGCACCC3′ |

| Cm-V | 5′GTTGTCCATATTGGCCACGTTTA3′ |

| spoT-U1 | 5′CTTGAGCATGCCAAAGTATTTGAAAATTACTACG3′ (SphI) |

| spoT-U2 | 5′GAAACTGCAGAGGCAGACTCGCAGTCTAATTAACG3′ (PstI) |

| spoT-P1 | 5′CGGCTCGAGGGAGTGAAACGTTGTACCTGTTTGAAAGCCT3′ (XhoI) |

| spoT-P2 | 5′CGGGAATTCGATAGAGTGCTTCAAAACCCAG3′ (EcoRI) |

| spoT-V1 | 5′AGGGTATATCAACCTAATCAACTGAAACG3′ |

| spoT-V3 | 5′CAGAGAGTTTACGCCCATTTCCTAATGCATG3′ |

| araC-V | 5′CATCCACCGATGGATAATCGGGTA3′ |

The sequences of restriction endonuclease sites are underlined, and the restriction endonuclease(s) is shown in parentheses after the sequence. The nucleotides in boldface type show the reverse complementary region between primers relA-U2 and relA-D1. The nucleotides in italic boldface type show the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the TTG start codon.

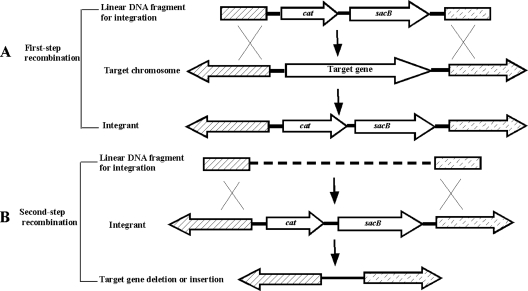

A general outline of our method is shown in Fig. 1. Deletion of a target gene is accomplished in two steps. In the first step (Fig. 1A), a linear DNA fragment carrying the cat (chloramphenicol resistance gene) and sacB genes flanked by long stretches (∼500 bp) of DNA homologous to the regions flanking the deletion site is prepared. The DNA fragment is electroporated into the desired host containing plasmid pKD46, which encodes the genes required for λ Red recombination (Table 1) (7). The targeted gene is then replaced by homologous recombination. Cells carrying the desired insertion/deletion are selected on media containing Cm. In the next step (Fig. 1B), a second DNA fragment encoding the desired deletion is prepared and used to electroporate pKD46-containing host cells. Replacement of the cat-sacB cassette is selected for on media containing sucrose (13). Sucrose-resistant electroporants are then screened for sensitivity to chloramphenicol and by PCR for the deletion. This process can be repeated as many times as necessary to construct a strain with multiple deletion mutations. When all the mutations have been made, pKD46 can be removed by growing the mutant at 37°C in the appropriate medium (3).

FIG. 1.

Schematic strategy for markerless deletion of a target chromosomal gene by two-step recombination. Cross-grained regions represent homology between the integration cassettes and sequences flanking the target gene. (A) A DNA fragment carrying the cat-sacB genes flanked by two long regions homologous to the DNA sequences bordering the target site is integrated into the chromosome to disrupt or delete the target gene(s). (B) A DNA fragment carrying the desired deletion or insertion flanked by two long regions homologous to the DNA sequences bordering the target sites directs replacement of the cat-sacB genes through homologous recombination.

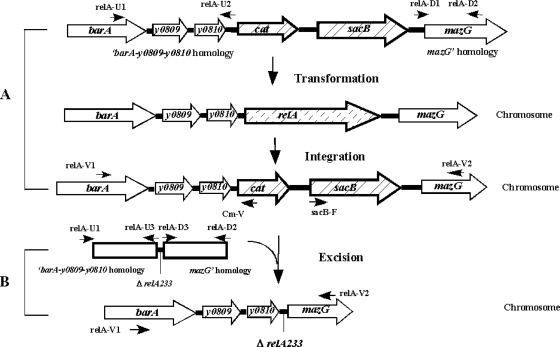

To demonstrate the feasibility of this system, we constructed a relA gene deletion in Y. pestis strain KIM6+ as outlined in Fig. 2. Plasmids encoding relA deletion cassettes with and without a cat-sac cassette insertion were constructed by overlapping PCR (Table 1). To prepare a red+ host, plasmid pKD46 was electroporated into Y. pestis KIM6+ (5). Y. pestis KIM6+(pKD46) cells were electroporated with 1 μg of PCR-amplified, gel-purified cat-sacB fragment flanked by long regions homologous to genes just upstream and downstream of relA. Approximately 1,000 Cmr transformants were obtained. We randomly picked 30 colonies and verified that all had the expected insertion by PCR (data not shown). Electrocompetent cells were prepared from a sucrose-sensitive isolate and electroporated with approximately 1 μg of a linear DNA containing the ΔrelA233 deletion and DNA sequences flanking the relA gene.

FIG. 2.

Construction of a ΔrelA mutation in Y. pestis KIM6+. (A) A DNA fragment encoding a cat-sacB cassette flanked by long regions homologous to genes just upstream and downstream of relA is introduced into Y. pestis KIM6+(pKD46). Selection on media containing chloramphenicol yields a strain in which relA is replaced by the cat-sacB cassette. The positions of oligonucleotide primers, such as relA-U1, relA-D1, relA-V1, and Cm-V, are indicated. (B) A DNA fragment containing the relA233 deletion and flanking regions adjacent to relA is introduced into the Y. pestis KIM6+(pKD46) cat-sacB strain. After selection on media containing sucrose, the cat-sacB cassette is replaced by the fragment containing the ΔrelA233 deletion.

We obtained ∼300 sucrose-resistant colonies and randomly selected 30 colonies. Twenty-six were PCR positive for the expected deletion, an efficiency of ∼86%. A single colony isolate was chosen and designated ΔrelA233 KIM6+(pKD46). Plasmid pKD46 was cured by growth at 37°C to yield strain χ10003.

To further validate this methodology, we introduced a second deletion, ΔspoT85, into strain ΔrelA233 KIM6+(pKD46) using a similar strategy. The efficiency at each step was similar to those reported above. Plasmid pKD46 was cured from a single colony isolate of the resulting strain to yield χ10004. These results show that this is a highly efficient method for introducing one or more gene deletions into Y. pestis.

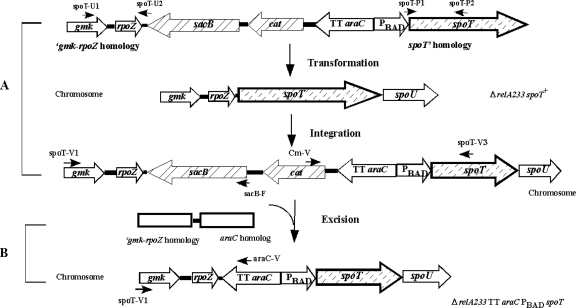

Because of our interest in studying the effects of spoT on virulence in Y. pestis, we wanted to construct a strain in which spoT expression could be regulated at will. The spoT gene is expressed in an operon after rpoZ (8). We inserted the arabinose-regulated PBAD promoter (11) between the rpoZ and spoT genes as outlined in Fig. 3. To ensure translation of spoT, we included the ribosome-binding sequence from the E. coli K-12 araB gene (GGAGTG) (21) 5 bp upstream of the start codon. The yields from this construction were similar to those described above.

FIG. 3.

Construction of an arabinose-regulated spoT gene in Y. pestis KIM6+. The transcription terminator (TT) araC PBAD-Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence was inserted upstream of the spoT gene in the chromosome of ΔrelA233 KIM6+(pKD46). The steps involved are analogous to those described in the legend to Fig. 2. The positions of oligonucleotide primers, such as spoT-U1, spoT-P1, spoT-V1, and Cm-V, are indicated. (A) Insertion of sacB-cat TT araC PBAD-SD spoT just after rpoZ. (B) Excision of the sacB-cat cassette.

HHS/CDC regulations dictate that antibiotic markers cannot be introduced into select agents, such as wild-type Y. pestis. Therefore, for these studies, we used the pCD1-cured KIM strain, Y. pestis KIM6+, which is not a select agent. However, due to the fact that the final constructs are marker-free after curing pKD46, plasmid pCD1 can be reintroduced into these strains to evaluate the effects of the introduced mutations on virulence.

We have described a strategy to generate scarless deletion and insertion mutations into the Y. pestis chromosome with high efficiency. In addition, we have eliminated the need to introduce a plasmid such as pCP20 that carries the Flp recombinase (4) which constitutes an additional electroporation and subsequent plasmid curing cycle. By obviating this need, plasmid pKD46 does not have to be cured and reintroduced for each mutagenic step. Therefore, multiple genes can be successively deleted more rapidly than with the traditional λ Red method. While this new method should be applicable to any Y. pestis strain, we note that for workers using Y. pestis strains that carry plasmid pCD1, curing of plasmid pKD46 should be done in medium containing 2.5 mM calcium (2). We have also successfully applied our strategy to other gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovars Typhi, Typhimurium, and Paratyphi A, demonstrating the broad utility of this method.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kenneth Roland for critically reading the manuscript and modifying the language.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI57885.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bearden, S. W., T. M. Stagees, and R. D. Perry. 1998. An ABC transporter system of Yersinia pestis allows utilization of chelated iron by Escherichia coli SAB11. J. Bacteriol. 180:1135-1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brubaker, R. R. 1972. The genus Yersinia: biochemistry and genetics of virulence. Curr. Top. Microbiol. 57:111-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cathelyn, J. S., S. D. Crosby, W. W. Lathem, W. E. Goldman, and V. L. Miller. 2006. RovA, a global regulator of Yersinia pestis, specifically required for bubonic plague. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:13514-13519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conchas, R. F., and E. Carniel. 1990. A highly efficient electroporation system for transformation of Yersinia. Gene 87:133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtiss, R., III, and W. Kong. 2006. Regulated bacterial lysis for gene vaccine vector delivery and antigen release. European patent WO 2004/020643 (patent no. 1537214).

- 7.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng, W., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, A. Boutin, G. F. Mayhew, P. Liss, N. T. Perna, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, J. D. Fetherston, L. E. Lindler, R. R. Brubaker, G. V. Plano, S. C. Straley, K. A. McDonough, M. L. Nilles, J. S. Matson, F. R. Blattner, and R. D. Perry. 2002. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis KIM. J. Bacteriol. 184:4601-4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derbise, A., B. Lesic, D. Dacheux, J. M. Ghigo, and E. Carniel. 2003. A rapid and simple method for inactivating chromosomal genes in Yersinia. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38:113-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards, R. A., L. H. Keller, and D. M. Schifferli. 1998. Improved allelic exchange vectors and their use to analyze 987P fimbria gene expression. Gene 207:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzman, L.-M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husseiny, M. I., and M. Hensel. 2005. Rapid method for the construction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine carrier strains. Infect. Immun. 73:1598-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaniga, K., I. Delor, and G. R. Cornelis. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy, K. C. 1998. Use of bacteriophage λ recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:2063-2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy, K. C., K. G. Campellone, and A. R. Poteete. 2000. PCR-mediated gene replacement in Escherichia coli. Gene 246:321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reference deleted.

- 17.Pouillot, F., C. Fayolle, and E. Carniel. 2007. A putative DNA adenine methyltransferase is involved in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis pathogenicity. Microbiology 153:2426-2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson, V. L., P. C. Oyston, and R. W. Titball. 2005. A dam mutant of Yersinia pestis is attenuated and induces protection against plague. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 252:251-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 20.Skrzypek, E., P. L. Haddix, G. V. Plano, and S. C. Straley. 1993. New suicide vector for gene replacement in Yersiniae and other Gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid 29:160-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith, B. R., and R. Schleif. 1978. Nucleotide sequence of the L-arabinose regulatory region of Escherichia coli K12. J. Biol. Chem. 253:6931-6933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]