Abstract

“Candidatus Pelagibacter ubique,” an abundant marine alphaproteobacterium, subsists in nature at low ambient nutrient concentrations and may often be exposed to nutrient limitation, but its genome reveals no evidence of global regulatory mechanisms for adaptation to stationary phase. High-resolution capillary liquid chromatography coupled online to an LTQ mass spectrometer was used to build an accurate mass and time (AMT) tag library that enabled quantitative examination of proteomic differences between exponential- and stationary-phase “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” cells cultivated in a seawater medium. The AMT tag library represented 65% of the predicted protein-encoding genes. “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” appears to respond adaptively to stationary phase by increasing the abundance of a suite of proteins that contribute to homeostasis rather than undergoing a major remodeling of its proteome. Stationary-phase abundances increased significantly for OsmC and thioredoxin reductase, which may mitigate oxidative damage in “Ca. Pelagibacter,” as well as for molecular chaperones, enzymes involved in methionine and cysteine biosynthesis, proteins involved in ρ-dependent transcription termination, and the signal transduction enzyme CheY-FisH. We speculate that this limited response may enable “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” to cope with ambient conditions that deprive it of nutrients for short periods and, furthermore, that the ability to resume growth overrides the need for a more comprehensive global stationary-phase response to create a capacity for long-term survival.

“Candidatus Pelagibacter ubique” is a member of the alphaproteobacterial SAR11 clade, a ubiquitous group of marine bacteria that can account for up to 35% of bacterioplankton populations in the ocean surface (28). With a biovolume of ∼0.01 μm3, this organism is among the smallest known free-living bacteria (35). Malmstrom et al. showed that SAR11 cells account for 50% of the amino acid and 30% of the 3-dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) uptakes in the North Atlantic Ocean (27). Due to their activity and abundance, it is thought that SAR11 organisms could have a large impact on the cycling of carbon and other important nutrients in the oceans.

Most of the ocean surface is a highly oligotrophic environment where low levels of phosphorus, usable forms of nitrogen, and iron limit plankton productivity. Because of this, marine bacteria are thought to shift between periods of growth when nutrients become available and periods of dormancy when they experience nutrient deprivation. The phenomenon of cells becoming viable but not culturable upon entry into stationary phase has been studied extensively with marine gammaproteobacteria of the genus Vibrio (6, 9); otherwise, there is relatively little information available about the strategies used by marine bacteria to respond to nutrient limitation.

Generally, there appears to be a range of mechanisms for adaptation to stationary-phase survival in bacteria. Global responses conferring increased resistance to a multitude of stresses, such as the σS-mediated expression of stationary-phase, survival-specific proteins in Escherichia coli (52) and sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (33), are activated regardless of the specific conditions causing entry into stationary phase. Other organisms lack a global stationary-phase response and instead have multiple stress-specific reactions, each of which can cause a transition into stationary phase (2, 7, 8, 12, 13, 24, 29, 30, 47). One organism studied, Campylobacter jejuni, does not appear to gain any survival advantage upon entry into stationary phase (22).

Genomic analysis of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” revealed that this organism has the vegetative sigma factor σ70 and the heat shock sigma factor σ32; however, it is lacking the stationary-phase sigma factor σS (15). After entering stationary phase, “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” cells undergo a change in cell shape from vibroid to coccoid, with a corresponding decrease in cell volume, and are able to return to both exponential growth and a vibroid cell shape after being transferred to fresh medium (unpublished data). These observations suggest that “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” has a stationary-phase response, whose mechanistic basis is unknown, that leads to increased survivability.

This study had two primary purposes. The first, a practical goal, was to create a comprehensive library of peptide accurate mass and time (AMT) tags so as to increase the accuracy and speed of subsequent proteomic analyses of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” (51). The second was to identify specific proteins that are differentially expressed between the exponential and stationary growth phases, in particular those proteins that may be involved in a global stationary-phase response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures.

Because bacterial protein expression often depends on growth conditions, it is important to analyze cells that are grown under many different conditions in order to acquire a comprehensive library of protein expression. To create a library of peptide AMT tags, six individual batch cultures of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” were grown in sterilized seawater medium amended either with nutrient mix A (50 nM DMSP, 10 μM NH4Cl, 1 μM K2HPO4, 0.3 mg/liter FeCl3, defined carbon mixture [35], and Va vitamins [10]) or with nutrient mix B (10 μM NH4Cl and 1 μM K2HPO4). Samples were grown in either darkness, ambient light, or direct light on a 14-h-on-10-h-off diel cycle, and cells were harvested during either exponential- or stationary-phase growth as outlined in Table 1. Cultures were equilibrated to 4°C to slow protein synthesis and degradation during harvest; cells were harvested by tangential flow filtration at a rate of ∼2 min/liter, using a Millipore Pellicon system with a 30-kDa regenerated cellulose filter. The concentrated cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 48,400 × g for 1 h at 4°C in a Beckman J2-21 centrifuge with a JA-20 rotor; the resulting pellets were stored at −80°C until proteomic analysis was performed.

TABLE 1.

Cultures used for creation of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” AMT tag library

| Sample | Vol (liters) | No. of cells | Nutrient mix | Growth phase | Light regimen | Preparation | Fractionation methoda | No. of peptides detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 1.44 × 1011 | A | Stationary | Ambient | Global, soluble, and insoluble | None | 5,787 |

| 2 | 80 | 5.42 × 1010 | A | Exponential | Ambient | Global | SCX | 6,823 |

| 3 | 20 | 2.94 × 1010 | A | Stationary | Ambient | Global | SCX | 4,338 |

| 4 | 20 | 1.10 × 1010 | A | Stationary | Ambient | Global | 1D SDS-PAGE | 372 |

| 5 | 40 | 2.00 × 1010 | B | Exponential | Diel | Global | None | 139 |

| 6 | 60 | 5.02 × 1010 | A | Exponential | Dark | Global | None | 6,345 |

Prior to reverse-phase HPLC. SCX, strong cation exchange; 1D SDS-PAGE, one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

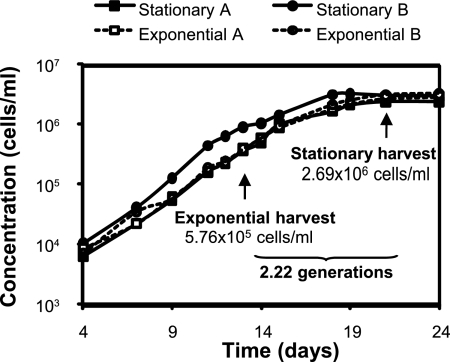

For the comparative analysis of stationary versus exponential growth phase, four “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” cultures were grown in sterile seawater medium amended with nutrient mix A. All four cultures were inoculated from a single stock and grown with aeration at 16°C under ambient light conditions. Two of the cultures were randomly selected and harvested (as outlined in the preceding paragraph) during exponential growth phase, i.e., when cell counts reached ∼5.8 × 105 cells/ml (Fig. 1); the remaining two cultures were harvested after the cells were in stationary phase for 2 to 3 days, i.e., when cell abundance plateaued, at ∼2.7 × 106 cells/ml (Fig. 1). In order to obtain sufficient and comparable amounts of protein mass (∼100 μg of protein by bicinchoninic acid protein assay) from each of the four cultures, exponential-phase cells were harvested from two 40-liter volumes of medium (∼2.3 × 1010 cells/sample), and the stationary-phase cells were harvested from two 10-liter volumes of medium (∼2.7 × 1010 cells/sample).

FIG. 1.

Growth curves for duplicate samples of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” harvested at either mid-exponential or early stationary phase. Approximately 100 μg of protein was produced from each of two 10-liter samples drawn from sterilized seawater medium at stationary phase and each of two 40-liter samples drawn from the medium at exponential phase.

Sample preparation.

Proteins were prepared as outlined by Adkins et al. (1). Due to low cell concentrations, all samples were prepared for global analysis; the sole exception was AMT tag library sample 1 (Table 1), which had enough biomass to permit global, soluble, and insoluble preparations. For global analysis, cells were lysed by bead beating in 100 mM NH4HCO3 buffer (pH, ∼8). Proteins were eluted and denatured with 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 5 mM dithiothreitol at 60°C for 30 min. For soluble and insoluble analyses, cell pellets were treated as described above, and the lysate was centrifuged. The supernatant (soluble preparation) was transferred to a fresh tube, and the remaining pellet was resuspended in 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS) in 50 mM NH4HCO3, and 5 mM dithiothreitol at 60°C for 30 min (insoluble preparation). For all analyses, the denatured proteins were diluted with buffer to reduce the salt concentration and digested with trypsin for 3 h at 37°C. Cleanup was performed by passing the samples through a C18 SPE column (5). The sample solutions were then concentrated in a Speed-Vac machine to a volume of ∼50 to 100 μl, quick-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until needed for analysis.

Building a library of AMT tags by LC-MS/MS.

Trypsinized proteins from “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” samples grown under a variety of conditions (Table 1) were fractionated by strong cation-exchange chromatography following the method of Adkins et al. (1). Approximately 25 fractions from each sample were collected; each was dried under vacuum and dissolved in 30 μl of 25 mM NH4HCO3. Aliquots containing 10 μg of protein were analyzed by capillary liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) (1) on a Thermo model LTQ ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific Corp., San Jose, CA), using data-dependent fragmentation on the top 10 ions per duty cycle and a 100-min LC gradient. A total of 135 LC-MS/MS analyses were performed using “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” cultures. The resulting MS/MS spectra were matched using the SEQUEST algorithm with predicted tryptic peptides from a protein file for “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” containing 1,398 protein entries compiled from annotation of the “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” genome (15). A standard parameter file allowing for a potential oxidation of the methionine residue and a mass error window of 3 m/z units for precursor mass and 0 m/z units for fragmentation mass was used. The searches also allowed for all possible peptide termini, i.e., they were not limited to tryptic termini. Peptide identifications were considered acceptable if they passed the thresholds determined by Washburn et al. (48) and, additionally, registered a discriminant score of at least 0.9 (42) and a Peptide Prophet score of at least 0.9 (21). The discriminant score is representative of the quality of the SEQUEST identification and is based on a combination of XCorr, delCn, tryptic state, and the difference between the observed elution time and the predicted LC normalized elution time (NET) for the peptide sequence (32, 42). The Peptide Prophet score, which also considers XCorr and delCn SEQUEST scores but does not discriminate between enzymatic states or take elution time into account, incorporates a parameter that measures the probability of identification by random chance. Both scores are normalized to a scale of 0 to 1, with 1 corresponding to an uncertainty-free identification. Peptide identifications were stored in an AMT tag database, along with the calculated monoisotopic masses from the identified sequences and the LC NET determined from a neural network algorithm (32).

Analysis of exponential- and stationary-phase “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” samples by LC-MS.

Each of the protein samples harvested from the four “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” cultures grown for the comparative analysis of stationary (two samples) versus exponential (two samples) growth phase was digested with trypsin as described in “Sample preparation,” and 10 μg of protein from each of these preparations was analyzed in triplicate (12 analyses in total) on a custom-built capillary high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system coupled via electrospray ionization (ESI) to a ThermoFisher Scientific LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Reverse-phase capillary HPLC columns were manufactured in-house by slurry packing a 3-μm Jupiter C18 stationary phase (Phenomenex, Torrence, CA) into a 60-cm length of 360-μm-outer-diameter by 75-μm-inner-diameter fused silica capillary tubing (Polymicro Technologies Inc., Phoenix, AZ). The mobile phases consisted of 0.2% acetic acid and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in water (A) and of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in 90% acetonitrile-10% water (B). The HPLC system was equilibrated at 10,000 lb/in2 with 100% mobile phase A. A mobile-phase selection valve was switched 50 min after injection to create a near-exponential gradient as mobile phase B displaced phase A in a 2.5-ml active mixer in a manner similar to that described by Doneanu et al. (11). Split flow controlled the gradient speed, operating under constant pressure (10,000 lb/in2). Flow through the capillary HPLC column equilibrated to 100% mobile phase A was ∼400 nl/min. The HPLC column was coupled to the mass spectrometer by use of an in-house-manufactured ESI interface with homemade 150-mm-outer-diameter by 20-mm-inner-diameter chemically etched electrospray emitters (23). The heated capillary temperature and spray voltage were 200°C and 2.2 kV, respectively. Data were acquired for 100 min, beginning 65 min after sample injection (15 min into the gradient). MS spectra (automatic gain control, 1 × 106) were recorded over the range of 400 to 2,000 m/z at a resolving power of 100,000, followed by data-dependent ion trap MS/MS spectra (automatic gain control, 1 × 104) of the three most abundant ions, using a collision energy of 35%. A dynamic exclusion time of 60 s was used to avoid reexamining previously analyzed ions. Relative abundances were generated by deconvoluting the peptide signal measurements from the Orbitrap instrument; the area under each peptide peak with a signal-to-noise ratio of >5:1 was integrated and recorded as the peptide's signal strength. In a typical analysis under the conditions just described, the peptides' signals vary by 4 to 5 orders of magnitude, with lower limits of detection ranging from 1 to 100 attomoles, depending on the specific peptide, the capillary column used, and the sample loaded on the column. Absolute abundances or concentrations of individual peptides or proteins cannot readily be deduced from the strengths of their signals due to protein-dependent variations in peptide production from the tryptic digestion, as well as peptide-to-peptide variations in ionization efficiency.

Peptide features from the 12 LC-MS analyses, consisting of the monoisotopic mass and the NET, were aligned and then matched to the same information for peptides in the AMT tag database, using a tolerance of ±6 ppm for mass and 0.025% for the LC NET. The mass deisotoping and alignment process was performed using Decon2LS, and the matching process was performed using VIPER (http://ncrr.pnl.gov/software/).

Differential expression analysis.

Two measures of differential expression were used in this study. The first measure was applied to proteins whose peptides were detected in at least 10 of the 12 analyses of the four growth samples (i.e., three replicates each of the two stationary-phase and two exponential-phase samples), with the additional constraint that a peptide be detected in at least two of the three replicate analyses of each sample. This conservative rule was adopted to minimize the effect of missing signals on the normalization procedure to follow. Each signal strength measured for a given peptide was mapped into M/A space (4) as follows:

|

|

where xi,j is the ith peptide's signal strength measured in the jth analysis and “baseline” is the ith peptide's average signal strength across all 10 to 12 analyses. Use of a common baseline for each peptide assumes that its 10 to 12 measured signals are drawn from the same parent population; this global-scale assumption, which has been made previously in proteomics (4), is commonly made in mRNA expression analyses where arrays are designed to target a large or complete set of open reading frames (34). The resulting Mi,j values were normalized to M′i,j by linear regression (4) to correct for linear dependence on the magnitude of the measured peptide signals and then converted back to log2-normalized signals by means of the following formula:

|

For each peptide, the log2-normalized signals from a given growth phase were averaged arithmetically to give the base 2 logarithm of the geometric mean of the normalized signal strengths for that peptide in that growth phase, as follows:

|

where n = 4, 5, or 6. The log2 relative signal strength of the peptide in the two growth phases was calculated by subtracting the log2 geometric mean of exponential-phase signals from the log2 geometric mean of stationary-phase signals to give the base 2 logarithm of the ratio of the two means, i.e., log2 (geometric meanstationary-phase signal/geometric meanexponential-phase signal). For a protein with only one qualifying peptide, the antilog2 of this peptide's log2 ratio of geometric means was taken as the protein's relative abundance; for a protein with two or more qualifying peptides, the antilog2 of the arithmetic average of these peptides' log2 ratios of geometric means was taken as the protein's relative abundance.

The second measure of differential expression used in this study was applied to four proteins where all identified peptides were found almost exclusively in the stationary phase (see Table 4). Since the absence of peptides identified in the exponential growth phase precluded calculation of relative abundances in this small number of cases, the number of unique peptides detected for a given protein in at least four of the six analyses of the two stationary-phase growth samples, with the additional constraints that a peptide be detected in at least two of the three replicate analyses of each sample and that there be at least five such peptides per protein, is reported as a measure of the degree of differential expression.

TABLE 4.

Proteins up-regulated upon entry into stationary phase (i.e., stationary-phase abundance is more than exponential-phase abundance) or detected exclusively in stationary-phase samples

| GenBank accession no. | Protein description | Gene | Ratioa | SE | No. of peptidesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins up-regulated in stationary phase | |||||

| YP_266440 | o-Acetylhomoserine (thiol)-lyase | metY | 10.95 | 8.85 | 3 |

| YP_265628 | Response regulator consisting of a CheY-like receiver domain and a Fis-type HTH domain | 4.46 | 0.97 | 1 | |

| YP_266172 | Homocysteine S-methyltransferase | mmuM | 4.34 | 1.18 | 1 |

| YP_266188 | Short-chain dehydrogenase, unknown specificity | 3.62 | 1.64 | 1 | |

| YP_266457 | Transcriptional repressor | nrdR | 3.52 | 3.26 | 1 |

| YP_265758 | Imidazoleglycerol-phosphate dehydratase | hisB | 3.38 | 1.22 | 1 |

| YP_265661 | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | sucA | 3.29 | 1.07 | 1 |

| YP_266342 | SurA | surA | 3.28 | 2.66 | 1 |

| YP_265764 | Bacterial protein export chaperone | secB | 2.82 | 0.46 | 1 |

| YP_265433 | Probable periplasmic serine protease DO-like precursor | htrA | 2.80 | 0.85 | 2 |

| YP_266237 | Nonspecific DNA-binding protein Hbsu | hupA/hupB | 2.71 | 1.34 | 3 |

| YP_265545 | H+-transporting two-sector ATPase (subunit b′) | atpB | 2.71 | 2.30 | 1 |

| YP_266396 | Single-strand binding protein | ssb | 2.55 | 2.18 | 3 |

| YP_265773 | Transcription termination factor | rho | 2.52 | 2.43 | 8 |

| YP_265670 | Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | asd | 2.50 | 0.46 | 1 |

| YP_265825 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.33 | 0.24 | 1 | |

| YP_265586 | 10-kDa chaperonin | groES | 2.27 | 1.11 | 3 |

| YP_266222 | Histidinol dehydrogenase | hisD2 | 2.26 | 0.24 | 1 |

| YP_266186 | Unknown protein | 2.26 | 0.94 | 1 | |

| YP_266219 | Glycine betaine/l-proline transport ATP-binding protein | proV | 2.25 | 1.72 | 1 |

| YP_265562 | Probable cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide II | coxB | 2.18 | 0.92 | 3 |

| YP_266735 | Acetylornithine deacetylase | argE | 2.15 | 0.36 | 1 |

| YP_265504 | Thioredoxin reductase | trxB | 2.10 | 1.51 | 3 |

| YP_266299 | ATP-dependent Clp proteinase regulatory chain X | clpX | 2.10 | 0.38 | 1 |

| YP_266354 | 2-Dehydro-3-deoxy-phosphooctonate aldolase | kdsA | 2.10 | 1.71 | 2 |

| YP_265501 | Type II secretion, type IV pilus retraction ATPase | pilT | 2.07 | 2.15 | 5 |

| YP_266520 | 30S ribosomal protein S19 | rpsS | 2.02 | 1.40 | 4 |

| Proteins detected exclusively in stationary phase | |||||

| YP_266580 | OsmC-like protein | osmC | 9 | ||

| YP_266023 | Uncharacterized protein conserved in bacteria | 7 | |||

| YP_266581 | Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase | bhmT | 5 | ||

| YP_265760 | ATP-dependent protease, heat shock | hslU | 5 |

Mean (average peptide abundance in stationary phase/average peptide abundance in exponential phase).

Number of peptides meeting the criteria for quantification.

RESULTS

In the text to follow, a protein whose abundance in the stationary growth phase is found to be higher or lower than its abundance in the exponential growth phase is referred to as up- or down-regulated, respectively.

AMT tag library.

The AMT tag library includes peptide sequences identified using the algorithm SEQUEST, accurate peptide masses determined from the identified peptide sequences, and the observed capillary HPLC elution times. Six “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” batch cultures were harvested at various stages of growth under a variety of conditions (Table 1). Proteins from these cultures were extracted, digested with trypsin, fractionated by strong cation-exchange chromatography, separated by capillary HPLC, and detected by electrospray MS. The AMT tag library created from these analyses comprises 10,957 unique peptides identified from 64,424 tandem mass spectra. The number of tandem mass spectra for a specific peptide can be quite large because (i) replicate analyses of a large number of samples have been performed; (ii) the peptide in question can be present in more than one cation-exchange fraction of each sample; (iii) in any given HPLC-MS analysis, spectra corresponding to each of several charge states of the peptide can be generated; and (iv) if the peptide elutes from the chromatographic column into the ion source over a long time relative to the mass spectrometer's duty cycle, multiples of each of these different charge-state spectra can be produced. The AMT tags assigned to the peptides in this database make it possible, without labeling, to identify peptides in high-sensitivity, capillary LC-Orbitrap MS analyses of protein digests and to quantify relative peptide abundances. Collectively, the peptides in the “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” AMT tag library account for 889 proteins (more than two peptides or three spectra per protein), or 65% of the organism's annotated protein-encoding genes; they cover 25% or more of the amino acid sequence in nearly two-thirds of the 889 proteins and no less than 2% in the remaining one-third.

Exponential- and stationary-phase proteomes.

The AMT tag library enabled quantitative comparisons of protein expression in cells harvested during the exponential and stationary growth phases (Fig. 1). Peptides were identified by matching their masses and NET to the entries in the AMT tag library; a protein was considered identified when one of its peptides was detected at a signal-to-noise ratio of >∼5:1 in 3 or more of the 12 analyses of samples prepared from the exponential- and stationary-phase growth cultures or when two or more of its peptides were detected in at least 1 of the 12 analyses. Applying these rules, the cells grown to mid-exponential phase yielded 2,617 peptides corresponding to 458 proteins, or 33% of the “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” predicted protein-encoding genes, whereas cells grown to early stationary phase yielded 3,536 peptides corresponding to 605 proteins, or 44% of the predicted protein-encoding genes. Taken together, cells from the two growth phases yielded a total of 3,895 unique peptides corresponding to 616 proteins, or 45% of the predicted protein-encoding genes.

The 20 most highly detected proteins from the two growth states, as determined by the number of tandem spectra in which they were identified (50), are listed in Table 2. Most of these proteins have housekeeping functions, such as oxidative phosphorylation, transcription, translation, or protein folding. The ABC-type amino acid transporter YhdW and a second putative ABC transporter for sugars, YP_266190, combined to register the greatest number of peptides from both growth phases. Other transporters, e.g., PotD, TauA, and LivJ, for amino acids, sugars, and other small molecules, were also among the more frequently detected proteins. The second most frequently detected protein in both growth states was a putative porin. An o-acetylhomoserine (thiol)-lyase, MetY, which is involved in cysteine and methionine metabolism, and the transcription termination factor Rho were two of the most frequently detected proteins in stationary phase while being among the least frequently detected proteins in exponential phase.

TABLE 2.

Proteins most frequently detected (as measured by spectral counts) in the exponential and stationary phases by capillary LC-Orbitrap MS/MS

| GenBank accession no. | Gene | Protein description | Spectral count

|

Function | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential phase | Stationary phase | ||||

| YP_266366 | yhdW | ABC transporter | 1,478 | 2,162 | Transport |

| YP_265784 | Putative porin | 1,127 | 1,360 | Channels/pores | |

| YP_266744 | potD | Spermidine/putrescine-binding protein | 1,025 | 1,079 | Transport |

| YP_266283 | smoM | Mannitol-binding protein | 959 | 1,069 | Transport |

| YP_265655 | atpD | F1-ATP synthase beta chain | 514 | 643 | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| YP_266190 | Probable ABC sugar transporter | 471 | 524 | Transport | |

| YP_266537 | tufB | Translation elongation factor EF-Tu | 360 | 761 | Translation |

| YP_266228 | tauA | Taurine transport system | 318 | 564 | Transport |

| YP_265690 | dctP | TRAP dicarboxylate transporter | 254 | 540 | Transport |

| YP_266501 | rpoA | DNA-directed RNA polymerase | 253 | 457 | Transcription |

| YP_266530 | rpoB | DNA-directed RNA polymerase | 213 | 283 | Transcription |

| YP_265587 | groEL | 60-kDa chaperonin | 196 | 551 | Protein folding and processing |

| YP_266237 | hupA/hupB | DNA-binding protein Hbsu | 187 | 360 | Cell structure and organization |

| YP_266529 | rpoC | DNA-directed RNA polymerase | 169 | 264 | Transcription |

| YP_265793 | dnaK | Chaperone protein | 145 | 277 | Protein folding and processing |

| YP_266552 | rpsD | Ribosomal protein S4 | 135 | 138 | Ribosomal proteins |

| YP_265656 | atpA | H+-transporting two-sector ATPase | 127 | 163 | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| YP_265812 | nusA | Transcription termination factor | 120 | 224 | Transcription regulation |

| YP_265733 | hflK | Probable integral membrane proteinase | 115 | 254 | Protein folding and processing |

| YP_265816 | pnp | Polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase | 109 | 186 | Nucleotide metabolism |

| YP_266531 | rplL | Ribosomal protein L7/L12 (L8) | 96 | 261 | Ribosomal proteins |

| YP_266440 | metY | o-Acetylhomoserine (thiol)-lyase | 94 | 749 | Amino acid biosynthesis |

| YP_265773 | rho | Transcription termination factor Rho | 80 | 189 | Transcription regulation |

Differential expression.

For proteins whose peptides were detected at least four times in both the exponential and stationary growth phases, an average relative abundance (see “Differential expression analysis” in Materials and Methods) of ≥2 was taken as significant evidence of differential expression. Alternatively, for four proteins, detection of five or more peptides exclusively in the two samples from the stationary growth phase was taken as significant evidence of differential expression. Based on these two rules, the degrees to which “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” expressed at least 52 of the 616 proteins detected in this experiment were significantly different between the exponential and stationary growth phases (Tables 3 and 4).

TABLE 3.

Proteins down-regulated in stationary phase (i.e., stationary phase abundance is less than exponential-phase abundance)

| GenBank accession no. | Product | Gene | Ratioa | SE | No. of peptidesb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YP_266101 | Formate dehydrogenase alpha subunit | fdhF | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1 |

| YP_266102 | NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase beta subunit | fdsB | 0.22 | 0.09 | 2 |

| YP_266682 | Cold shock DNA-binding domain protein | cspL | 0.28 | 0.25 | 3 |

| YP_266492 | Unknown protein | 0.29 | 0.07 | 1 | |

| YP_266570 | Unknown protein | 0.30 | 0.10 | 1 | |

| YP_265460 | Cell division protein | ftsZ | 0.31 | 0.13 | 1 |

| YP_265469 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large chain | carB | 0.33 | 0.25 | 5 |

| YP_266197 | 2-Hydroxyhepta-2,4-diene-1,7-dioate isomerase | hpcE | 0.34 | 0.10 | 1 |

| YP_266589 | Phosphate ABC transporter, periplasmic phosphate-binding protein | pstS | 0.35 | 0.11 | 2 |

| YP_265911 | Acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase carboxyl transferase subunit beta | accD | 0.36 | 0.06 | 1 |

| YP_266419 | Probable ABC transporter inner membrane protein | sbmA | 0.37 | 0.19 | 1 |

| YP_266373 | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | ilvD | 0.39 | 0.22 | 4 |

| YP_266499 | Ribosomal large subunit pseudouridine synthase C | rluC | 0.39 | 0.07 | 1 |

| YP_265631 | Arginase | speB1 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 1 |

| YP_266255 | Adenylylsulfate reductase membrane anchor | aprM | 0.41 | 0.16 | 2 |

| YP_266502 | Ribosomal protein S11 | rpsK | 0.44 | 0.16 | 2 |

| YP_266473 | Sarcosine oxidase | soxB | 0.47 | 0.08 | 1 |

| YP_266397 | DNA gyrase subunit A | gyrA | 0.47 | 0.23 | 2 |

| YP_266506 | 50S ribosomal protein L15 | rplO | 0.47 | 0.14 | 2 |

| YP_266121 | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase | purF | 0.48 | 0.26 | 1 |

| YP_266355 | Enolase | eno | 0.49 | 0.05 | 1 |

Mean (average peptide abundance in stationary phase/average peptide abundance in exponential phase).

Number of peptides meeting the criteria for quantification.

Twenty-one proteins were found to be down-regulated during stationary growth, i.e., expressed at lower levels in the stationary phase than in the exponential phase (Table 3). These proteins are involved in a variety of functions, including carbon metabolism, translational control, and amino acid biosynthesis. Thirty-one proteins were found to be up-regulated in the stationary growth phase, i.e., expressed at higher levels in the stationary phase than in the exponential phase (Table 4). Roles for these proteins include amino acid biosynthesis, signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, stress responses, and protein folding.

DISCUSSION

Application of label-free quantification.

For marine bacteria such as “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” that are difficult to grow in culture, acquiring sufficient protein for qualitative analysis is laborious, and this is even more so for accurate quantitative analyses. In working with such organisms, an AMT tag library provides increased sensitivity for identification and label-free quantification of low-abundance peptides. While building an AMT tag library is initially time- and sample-intensive, it ultimately allows for quantitative comparisons without the need for MS/MS, thus alleviating the need for large amounts of protein in subsequent experiments.

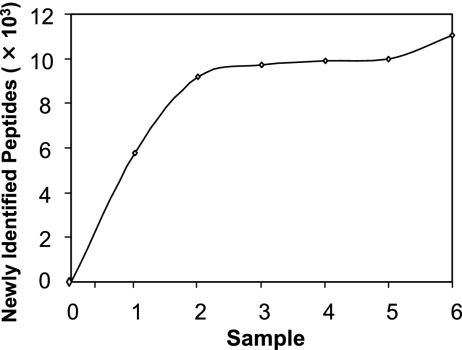

In addition to increasing sensitivity, a high-resolution AMT tag library provides accurate peptide identifications over a broad range of conditions (40, 51). Six cultures were grown under a variety of conditions to build the AMT tag library used in this study; this library comprised 10,957 unique peptides corresponding to 889 proteins, or 65% of the protein-encoding genes. Of these proteins, 45 were identified as hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins, supporting the annotation of their genes as protein-encoding genes. An AMT tag library is considered mature when the analysis of new samples fails to identify new proteins. Given the size of the “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” genome and the fact that sample 6, which came from cells grown in the dark, produced only a slight increase in newly identified peptides (Fig. 2), the AMT tag library generated for this study was taken to be close to maturity; however, as new conditions that lead to the expression of more genes are discovered, newly identified peptides from “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” will be added to the AMT tag library.

FIG. 2.

Growth in coverage of the AMT tag library with additional culture conditions/samples.

Comparison of exponential- and stationary-phase proteomes.

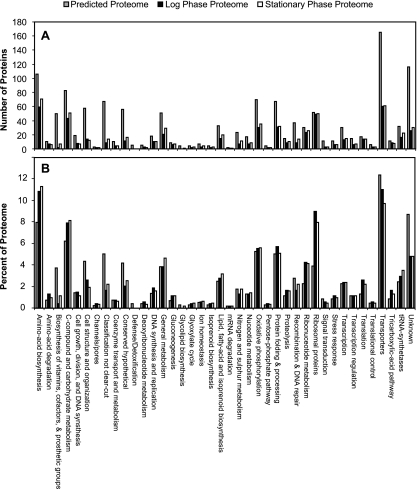

The majority of the detected proteome (92%) showed no measurable differences in expression between the two growth conditions. This observation suggests that despite a lowering of its growth rate, most of the cell's metabolic processes remained active in early stationary phase. Specifically, proteins involved in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, protein synthesis, purine metabolism, ribosome structure, and translation showed no measurable changes in their levels. Of the proteins that exhibited differential expression, few of them clustered into clear-cut pathways that were turned on or off upon entry into stationary phase. Figure 3A shows the number of proteins detected in each functional group for either the predicted proteome or the expressed proteome in exponential or stationary phase; Fig. 3B shows the same data as percentages of the total number of proteins predicted or detected in each growth phase. Of the 116 genes annotated as encoding hypothetical or conserved hypothetical proteins, only 39% were detected in this experiment, suggesting that a portion of these are either misannotated or nonfunctional or that they code for functionally specific proteins that were not expressed under the culture conditions used in this experiment. It was observed that proteins involved in the metabolism of ribonucleotides, ribosomes, carbon compounds, and carbohydrates and in the biosynthesis of amino acids were observed more frequently than expected from their percentage of the predicted protein coding sequences; this observation seems reasonable since the roles these proteins play in housekeeping functions would dictate their presence at higher copy numbers in the cell.

FIG. 3.

Total predicted proteome (blue), detected exponential-phase proteome (red), and detected stationary-phase proteome (yellow) of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique,” grouped by functional category. Bar heights represent the numbers of proteins or percentages of total proteins (the number of proteins in each functional category divided by the total number of proteins detected for that proteome) for this experiment.

Proteins of interest. (i) Stress response proteins.

OsmC and thioredoxin reductase (TrxB) were observed to be up-regulated in stationary phase in “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique.” The up-regulation of OsmC coincides with stationary-phase increases in OsmC that have been observed in E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3, 17). Genomic annotation indicates that “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” contains neither a catalase nor a superoxide dismutase (commonly involved in defense against free radicals); however, osmotically inducible OsmC has been shown to defend against oxidative stress by using its highly reactive cysteine thiols to mediate the reduction of organic hydroperoxides (26). Alignment of the “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” and E. coli osmC genes reveals that their reactive cysteines are conserved. Although OsmC was detected in both growth phases, its relative abundance was higher in stationary phase than in exponential phase. In addition to the three peptides that satisfied the first rule for quantification, detection of 21 of the protein's other peptides exclusively in stationary phase provided additional support for up-regulation of this protein in the stationary phase. This observation suggests that while OsmC may be necessary in both growth phases for defense against oxidative damage (e.g., from exposure to high visible and UV light irradiance in oxic surface waters), greater amounts of this protein are required to protect a cell as its growth rate slows and it enters stationary phase.

Thioredoxin (TrxA) and thioredoxin reductase (TrxB) were detected in both stationary and exponential phases in this study, but TrxB was up-regulated in stationary-phase samples. Studies involving trxB mutants in E. coli have shown that the reduction of TrxA by TrxB is required for defense against H2O2 damage and possibly to repair damaged proteins in stationary phase (44). The up-regulation of TrxB in stationary phase in “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” may be necessary for improved recycling of TrxA to its reduced form in order to enhance protection of the cell as the growth rate lowers and oxidative damage accumulates.

(ii) Amino acid biosynthesis proteins.

Higher levels of expression were observed in exponential phase for several enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of amino acids. Specifically, the relative levels of proteins involved in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids, glycine, and arginine were observed to be higher in exponential phase, whereas the relative abundances of proteins that participate in the biosynthesis of cysteine, methionine, and histidine were found to be greater in stationary phase.

The following three enzymes included in cysteine and methionine biogenesis from organic sulfur sources were found to be more abundant in stationary-phase cells: o-acetylhomoserine (thiol)-lyase (MetY), homocysteine S-methyltransferase (MmuM), and betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BhmT). An analysis of upstream regulatory regions in the “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” genome revealed two conserved motifs (AkTTGAACnnTATTGT and AAGyACTAAAAA) upstream of each of the genes metY, mmuM, and bhmT (Daniel Smith, unpublished data). The presence of these motifs suggests that these genes share a common regulatory mechanism. Genomic annotation indicates that genes required for assimilatory sulfate reduction (cysDNHIJ) are missing from “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” (46a), suggesting that this organism is unable to utilize inorganic sulfate for the synthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids and, instead, must rely on reduced sulfur compounds from the environment. On the basis of this inference, the culture medium in which the cells for this study were grown included DMSP as a source of reduced sulfur compounds. As of yet, the reason for the up-regulation of these genes in stationary phase is unclear. We speculate that it could be that higher production of these proteins during stationary phase is necessary to support the expression of other stationary-phase-specific proteins, such as the stress response protein OsmC mentioned earlier, that have specific requirements for cysteine or methionine. In addition to the conserved regulatory motifs mentioned earlier, the discovery that an additional, albeit weaker, upstream motif was shared with these genes (metY, mmuM, and bhmT), the metX-metW-gloB operon (also involved in cysteine and methionine biosynthesis), and osmC bolsters the hypothesis that proteins involved in the production of methionine and cysteine support the stationary-phase expression of OsmC.

Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase, which is involved in the synthesis of valine, leucine, and isoleucine, and carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, which catalyzes the conversion of glutamine to carbamoyl-phosphate, a precursor in the biosynthetic pathways of arginine and pyrimidine, were detected at higher levels in the exponential phase than in the stationary phase. In the latter case, only the enzyme's larger subunit, CarB, was measured at a higher relative abundance during exponential growth; the smaller subunit, CarA, was detected, but not with sufficient signal strength to permit quantitative comparison between the two growth phases.

Sarcosine oxidase, which catalyzes the reaction of sarcosine with water and oxygen to produce glycine, was also found in greater relative abundance in exponential phase. A toxic by-product of this reaction is formaldehyde, which spontaneously degrades to formate. Formate is removed from the cell as CO2 with the production of the reduced cofactor NADH by formate dehydrogenase, two subunits of which were also detected in greater abundance in exponential phase.

The multifunctional enzyme 2-hydroxyhepta-2,4-diene-1,7-dioate isomerase, which is responsible for the addition or removal of a CO2 molecule from a variety of substrates involved in the metabolism of amino acids, nucleotides, and vitamins, was also detected at higher levels in the exponential phase than in the stationary phase.

(iii) Chaperones and proteases.

As in many other bacteria, molecular chaperones were up-regulated in stationary phase in “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique,” probably reflecting the survival value of functions that maintain protein stability and activity during prolonged periods where new protein synthesis is suspended or very limited. SurA is essential for stationary-phase survival in E. coli (45) and is necessary for correctly folding certain outer membrane and periplasmic proteins (25). It follows that SurA could play a similar role in “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique.” The DO-like periplasmic serine protease HtrA has been shown to provide thermal and oxidative stress resistance to heat, ethanol, puromycin, and NaCl in Lactococcus lactis and Porphyromonas gingivalis (14, 37). Spiess et al. (41) also showed that HtrA is involved in protein folding and the degradation of misfolded proteins at low temperatures. By extension, therefore, it seems likely that HtrA would be up-regulated upon entry of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” into stationary phase in order to function as a chaperone in the periplasmic space.

Two two-component ATP-dependent chaperones/proteases were found to be up-regulated in stationary-phase samples. HslU and ClpX are both members of the AAA+ superfamily of Clp ATPases and have been shown to act both as chaperones and as proteolytic molecules (39, 49). In E. coli, HslU is known to act in concert with HslV (detected in stationary-phase samples, but not at a level that met the criteria used in this study for significance) to prevent the aggregation of SulA, thereby increasing SulA's ability to inhibit the cell division protein FtsZ (38). “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” does not have a sulA homologue, but FtsZ did show down-regulation in stationary phase (Table 3). While a direct link between HslVU and the decreased expression of FtsZ cannot be made at this time, the expression of members of the Clp family of chaperones/proteases in stationary phase suggests that they are involved in posttranslational regulation of cell function, either by increasing the efficiency of stationary-phase-specific proteins or by degradation of exponential-phase proteins, such as FtsZ, that are no longer necessary for cell processes.

Cytoplasmic proteins involved in protein folding and stabilization that were also observed to be up-regulated in stationary phase included the bacterial export chaperone SecB and the chaperone GroES.

(iv) Proteins involved in transcriptional repression.

Regulatory molecules generally have low copy numbers, making them more difficult to detect than high-copy-number enzymatic proteins. Despite this, we were able to quantify the differential expression of the following two regulatory proteins that are likely involved in repression of transcription upon entry into stationary phase: the transcription termination factor Rho and the transcriptional repressor NrdR. Rho-dependent transcription termination is important for cell survival when translation becomes uncoupled from transcription, for example, when cells experience amino acid limitation or environmental stress. Harinarayanan and Gowrishankar (19) showed that this uncoupling results in the formation of loop structures when the naked RNA transcript binds with a single strand of DNA and displaces the other DNA strand. These loop structures are detrimental and can lead to cell death. Transcriptional termination by Rho prevents the synthesis of unused RNA transcripts and thus the formation of the harmful loop structures, thereby prolonging the life of the cell. Scenarios involving either amino acid limitation or environmental stress are likely for “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” upon entry into stationary phase in a nutrient-limited environment and are supported by the observation of proteins involved in these processes being up-regulated in stationary phase. It is probable that Rho plays a role in cell survival upon entry into stationary phase of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique,” but further study into the operons affected by ρ-dependent termination will be needed to confirm this.

Another protein involved in transcriptional repression, NrdR, was also found to be up-regulated during stationary phase. This protein is involved in the repression of ribonucleotide reductase genes that are responsible for the reduction of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides (18), and the gene is located in a gene cluster that is conserved in proteobacteria (36). It has been suggested that NrdR acts on ribonucleotide reductase genes in response to many factors, including oxidative stress, stress to the replication machinery, or the cell cycle (16, 43). In E. coli and P. aeruginosa, NrdR represses the nrdAB operon in stationary phase or when the deoxynucleoside triphosphate pool is low (20, 31, 46). The “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” genome also contains a nrdAB operon, but neither protein was detected at a significant level in this experiment. While it cannot be said with certainty that NrdR acts on the nrdAB operon in “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique,” it makes sense that this protein would be involved in the repression of transcription and cell cycle upon entry into stationary phase.

Conclusions.

A key goal of this study was to identify adaptive mechanisms used by “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” to survive stationary phase. The advantage of an AMT tag library is that once it is constructed, subsequent quantitative comparisons of proteomic variation require relatively little protein. The AMT tag library built in this study covers 65% of the possible proteome, a level that is quite comprehensive based on our experience but where we can predict that coverage of the coding sequences will increase as additional studies are conducted under different cultivation conditions.

Planktonic marine bacteria subsist at very low nutrient concentrations and, as a result, may often suffer restricted growth in their natural environment; consequently, their adaptations to nutrient limitation are a matter of significance to marine microbiologists. It was found in this study that while the expression of most “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” proteins changed immeasurably upon entry into stationary phase, a small suite of proteins did up-regulate appreciably. Many of the 31 proteins detected in greater abundance in stationary phase than in exponential phase are known stress response proteins or regulatory molecules. In particular, proteins associated with protein refolding, transcription termination factors, and proteins involved in mitigating oxidative damage appear to be important to the ability of “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” to survive in stationary phase. These findings suggest that “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” employs a relatively simple program of proteome remodeling to endure periods of growth limitation and, furthermore, that by its simple nature this adaptive response enables “Ca. Pelagibacter ubique” to adjust quickly to fluctuations in the availability of nutrients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cliff Pereira and Jack Giovanni for their assistance with statistical analysis and Larry Wilhelm and Daniel Smith for their help with bioinformatics.

This work was supported by a Marine Microbiology Initiative investigator award from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Portions of this research were also supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Biological and Environmental Research and performed at the Environmental Molecular Science Laboratory, a DOE national scientific user facility located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins, J. N., H. M. Mottaz, A. D. Norbeck, J. K. Gustin, J. Rue, T. R. Clauss, S. O. Purvine, K. D. Rodland, F. Heffron, and R. D. Smith. 2006. Analysis of the Salmonella typhimurium proteome through environmental response toward infectious conditions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5:1450-1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Martinez, C. E., R. L. Baldini, and S. L. Gomes. 2006. A Caulobacter crescentus extracytoplasmic function sigma factor mediating the response to oxidative stress in stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 188:1835-1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atichartpongkul, S., S. Loprasert, P. Vattanaviboon, W. Whangsuk, J. D. Helmann, and S. Mongkolsuk. 2001. Bacterial Ohr and OsmC paralogues define two protein families with distinct functions and patterns of expression. Microbiology 147:1775-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callister, S. J., R. C. Barry, J. N. Adkins, E. T. Johnson, W. J. Qian, B. J. Webb-Robertson, R. D. Smith, and M. S. Lipton. 2006. Normalization approaches for removing systematic biases associated with mass spectrometry and label-free proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 5:277-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callister, S. J., M. A. Dominguez, C. D. Nicora, X. Zeng, C. L. Tavano, S. Kaplan, T. J. Donohue, R. D. Smith, and M. S. Lipton. 2006. Application of the accurate mass and time tag approach to the proteome analysis of sub-cellular fractions obtained from Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1. Aerobic and photosynthetic cell cultures. J. Proteome Res. 5:1940-1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaiyanan, S., S. Chaiyanan, C. Grim, T. Maugel, A. Huq, and R. R. Colwell. 2007. Ultrastructure of coccoid viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae. Environ. Microbiol. 9:393-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, P. F., S. J. Foster, E. Ingham, and M. O. Clements. 1998. The Staphylococcus aureus alternative sigma factor sigmaB controls the environmental stress response but not starvation survival or pathogenicity in a mouse abscess model. J. Bacteriol. 180:6082-6089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, M. E., Q. He, Z. He, K. H. Huang, E. J. Alm, X. F. Wan, T. C. Hazen, A. P. Arkin, J. D. Wall, J. Z. Zhou, and M. W. Fields. 2006. Temporal transcriptomic analysis as Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough transitions into stationary phase during electron donor depletion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5578-5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colwell, R. R., P. R. Brayton, D. J. Grimes, D. B. Roszak, S. A. Huq, and L. M. Palmer. 1985. Viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae and related pathogens in the environment: implications for release of genetically engineered microorganisms. Nat. Biotechnol. 3:817. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, H. C., and R. R. L. Guillar. 1958. Relative value of ten genera of micro-organisms as food for oyster and clam larvae. USFWS Fish Bull. 58:293-304. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doneanu, C. E., D. A. Griffin, E. L. Barofsky, and D. F. Barofsky. 2001. An exponential dilution gradient system for nanoscale liquid chromatography in combination with MALDI or nano-ESI mass spectrometry for proteolytic digests. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 12:1205-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duwat, P., B. Cesselin, S. Sourice, and A. Gruss. 2000. Lactococcus lactis, a bacterial model for stress responses and survival. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55:83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster, J. S., A. K. Singh, L. J. Rothschild, and L. A. Sherman. 2007. Growth-phase dependent differential gene expression in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and regulation by a group 2 sigma factor. Arch. Microbiol. 187:265-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foucaud-Scheunemann, C., and I. Poquet. 2003. HtrA is a key factor in the response to specific stress conditions in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 224:53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovannoni, S. J., H. J. Tripp, S. Givan, M. Podar, K. L. Vergin, D. Baptista, L. Bibbs, J. Eads, T. H. Richardson, M. Noordewier, M. S. Rappe, J. M. Short, J. C. Carrington, and E. J. Mathur. 2005. Genome streamlining in a cosmopolitan oceanic bacterium. Science 309:1242-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gon, S., and J. Beckwith. 2006. Ribonucleotide reductases: influence of environment on synthesis and activity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8:773-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordia, S., and C. Gutierrez. 1996. Growth-phase-dependent expression of the osmotically inducible gene osmC of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 19:729-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grinberg, I., T. Shteinberg, B. Gorovitz, Y. Aharonowitz, G. Cohen, and I. Borovok. 2006. The Streptomyces NrdR transcriptional regulator is a Zn ribbon/ATP cone protein that binds to the promoter regions of class Ia and class II ribonucleotide reductase operons. J. Bacteriol. 188:7635-7644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harinarayanan, R., and J. Gowrishankar. 2003. Host factor titration by chromosomal R-loops as a mechanism for runaway plasmid replication in transcription termination-defective mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 332:31-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrick, J., and B. Sclavi. 2007. Ribonucleotide reductase and the regulation of DNA replication: an old story and an ancient heritage. Mol. Microbiol. 63:22-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller, A., A. I. Nesvizhskii, E. Kolker, and R. Aebersold. 2002. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 74:5383-5392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly, A. F., S. F. Park, R. Bovill, and B. M. Mackey. 2001. Survival of Campylobacter jejuni during stationary phase: evidence for the absence of a phenotypic stationary-phase response. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2248-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly, R. T., J. S. Page, Q. Luo, R. J. Moore, D. J. Orton, K. Tang, and R. D. Smith. 2006. Chemically etched open tubular and monolithic emitters for nanoelectrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 78:7796-7801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler, C., S. Wolff, D. Albrecht, S. Fuchs, D. Becher, K. Buttner, S. Engelmann, and M. Hecker. 2005. Proteome analyses of Staphylococcus aureus in growing and non-growing cells: a physiological approach. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 295:547-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lazar, S. W., and R. Kolter. 1996. SurA assists the folding of Escherichia coli outer membrane proteins. J. Bacteriol. 178:1770-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lesniak, J., W. A. Barton, and D. B. Nikolov. 2003. Structural and functional features of the Escherichia coli hydroperoxide resistance protein OsmC. Protein Sci. 12:2838-2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malmstrom, R. R., R. P. Kiene, M. T. Cottrell, and D. L. Kirchman. 2004. Contribution of SAR11 bacteria to dissolved dimethylsulfoniopropionate and amino acid uptake in the North Atlantic ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4129-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris, R. M., M. S. Rappe, S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, W. A. Siebold, C. A. Carlson, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. SAR11 clade dominates ocean surface bacterioplankton communities. Nature 420:806-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mouery, K., B. A. Rader, E. C. Gaynor, and K. Guillemin. 2006. The stringent response is required for Helicobacter pylori survival of stationary phase, exposure to acid, and aerobic shock. J. Bacteriol. 188:5494-5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee, R., and D. Chatterji. 2005. Evaluation of the role of sigma B in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338:964-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nordlund, P., and P. Reichard. 2006. Ribonucleotide reductases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:681-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petritis, K., L. J. Kangas, P. L. Ferguson, G. A. Anderson, L. Pasa-Tolic, M. S. Lipton, K. J. Auberry, E. F. Strittmatter, Y. Shen, R. Zhao, and R. D. Smith. 2003. Use of artificial neural networks for the accurate prediction of peptide liquid chromatography elution times in proteome analyses. Anal. Chem. 75:1039-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips, Z. E., and M. A. Strauch. 2002. Bacillus subtilis sporulation and stationary phase gene expression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59:392-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quackenbush, J. 2002. Microarray data normalization and transformation. Nat. Genet. 32(Suppl.):496-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rappe, M. S., S. A. Connon, K. L. Vergin, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2002. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 418:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodionov, D. A., and M. S. Gelfand. 2005. Identification of a bacterial regulatory system for ribonucleotide reductases by phylogenetic profiling. Trends Genet. 21:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy, F., E. Vanterpool, and H. M. Fletcher. 2006. HtrA in Porphyromonas gingivalis can regulate growth and gingipain activity under stressful environmental conditions. Microbiology 152:3391-3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seong, I. S., J. Y. Oh, J. W. Lee, K. Tanaka, and C. H. Chung. 2000. The HslU ATPase acts as a molecular chaperone in prevention of aggregation of SulA, an inhibitor of cell division in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 477:224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seong, I. S., J. Y. Oh, S. J. Yoo, J. H. Seol, and C. H. Chung. 1999. ATP-dependent degradation of SulA, a cell division inhibitor, by the HslVU protease in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 456:211-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith, R. D., G. A. Anderson, M. S. Lipton, L. Pasa-Tolic, Y. Shen, T. P. Conrads, T. D. Veenstra, and H. R. Udseth. 2002. An accurate mass tag strategy for quantitative and high-throughput proteome measurements. Proteomics 2:513-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spiess, C., A. Beil, and M. Ehrmann. 1999. A temperature-dependent switch from chaperone to protease in a widely conserved heat shock protein. Cell 97:339-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strittmatter, E. F., L. J. Kangas, K. Petritis, H. M. Mottaz, G. A. Anderson, Y. Shen, J. M. Jacobs, D. G. Camp II, and R. D. Smith. 2004. Application of peptide LC retention time information in a discriminant function for peptide identification by tandem mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 3:760-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun, L., and J. A. Fuchs. 1992. Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase expression is cell cycle regulated. Mol. Biol. Cell 3:1095-1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takemoto, T., Q. M. Zhang, and S. Yonei. 1998. Different mechanisms of thioredoxin in its reduced and oxidized forms in defense against hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 24:556-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tormo, A., M. Almiron, and R. Kolter. 1990. surA, an Escherichia coli gene essential for survival in stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 172:4339-4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Torrents, E., A. Poplawski, and B. M. Sjoberg. 2005. Two proteins mediate class II ribonucleotide reductase activity in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: expression and transcriptional analysis of the aerobic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 280:16571-16578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46a.Tripp, H. J., J. B. Kitner, M. S. Schwalbach, J. W. H. Dacey, L. J. Wilhelm, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2008. SARII marine bacteria require exogenous reduced sulfur for growth. Nature 452:741-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viswanathan, P., M. Singer, and L. Kroos. 2006. Role of sigmaD in regulating genes and signals during Myxococcus xanthus development. J. Bacteriol. 188:3246-3256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Washburn, M. P., D. Wolters, and J. R. Yates III. 2001. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 19:242-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wawrzynow, A., D. Wojtkowiak, J. Marszalek, B. Banecki, M. Jonsen, B. Graves, C. Georgopoulos, and M. Zylicz. 1995. The ClpX heat-shock protein of Escherichia coli, the ATP-dependent substrate specificity component of the ClpP-ClpX protease, is a novel molecular chaperone. EMBO J. 14:1867-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, B., N. C. VerBerkmoes, M. A. Langston, E. Uberbacher, R. L. Hettich, and N. F. Samatova. 2006. Detecting differential and correlated protein expression in label-free shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 5:2909-2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimmer, J. S., M. E. Monroe, W. J. Qian, and R. D. Smith. 2006. Advances in proteomics data analysis and display using an accurate mass and time tag approach. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 25:450-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zinser, E. R., and R. Kolter. 2004. Escherichia coli evolution during stationary phase. Res. Microbiol. 155:328-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]