Abstract

The diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic (AAP) bacteria has been examined in marine habitats, but the types of AAP bacteria in estuarine waters and distribution of ecotypes in any environment are not well known. The goal of this study was to determine the diversity of AAP bacteria in the Delaware estuary and to examine the distribution of select ecotypes using quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays for the pufM gene, which encodes a protein in the light reaction center of AAP bacteria. In PCR libraries from the Delaware River, pufM genes similar to those from Beta- (Rhodoferax-like) or Gammaproteobacteria comprised at least 50% of the clones, but the expressed pufM genes from the river were not dominated by these two groups in August 2002 (less than 31% of clones). In four transects, qPCR data indicated that the gammaproteobacterial type of pufM was abundant only near the mouth of the bay whereas Rhodoferax-like AAP bacteria were restricted to waters with a salinity of <5. In contrast, a Rhodobacter-like pufM gene was ubiquitous, but its distribution along the salinity gradient varied with the season. High fractions (12 to 24%) of all three pufM types were associated with particles. The data suggest that different groups of AAP bacteria are controlled by different environmental factors, which may explain current difficulties in predicting the distribution of total AAP bacteria in aquatic environments.

Several groups of bacteria potentially have the capacity to derive extra energy from light while assimilating organic matter for carbon and energy (13). Among potential photoheterotrophs are the aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic (AAP) bacteria. The abundance of these bacteria varies greatly among aquatic regimes (0 to 20% of total bacterial abundance) (8, 21, 23, 28, 31), with estuaries having some of the highest estimates (28, 38). The reasons for this high variation are not clear, although environmental factors, such as nutrient status (21), light, and particles (38), have been hypothesized to control AAP bacterial communities. The distribution of specific groups of AAP bacteria, which has not yet been examined in depth, may provide some clues.

Culture-dependent and -independent studies suggest that there are habitat-specific types of AAP bacteria. Culture-dependent studies found isolates typical of marine and saline habitats (18), and a recent examination of metagenomic clones from the Global Ocean Sampling revealed differences in the composition of AAP bacterial communities between estuarine and oceanic regimes (41), although only a single location in the estuaries was examined. In oceanic and coastal waters, AAP bacteria belong to the alpha-3 and alpha-4 subclasses of Alphaproteobacteria (Roseobacter and Erythrobacter) (2, 20, 25), and PCR and metagenomic clones from coastal waters (4, 16) contain pufM DNA sequences closely related to those of a gammaproteobacterium in the OM60 clade (6) and to those of Congregibacter litoralis sp. strain KT71 (15). Phylogenetic analyses of pufM and other photosynthesis genes suggested that uncultured AAP bacteria related to Rhodobacter are abundant in the Delaware estuary (37). Additionally, 16S rRNA analyses indicate that Rhodobacter-like bacteria are capable of inhabiting estuarine waters with a wide range of salinities (10). One type of riverine AAP bacterium is related to strictly freshwater Betaproteobacteria, such as Roseateles depolymerans (34) and members of the Rhodoferax clade (11). Although the diversity of AAP bacteria is starting to become clear, we know little about estuarine ecotypes or about the distribution of ecotypes in any environment.

The aim of this work was to examine freshwater and estuarine ecotypes of pufM genes from uncultivated AAP bacteria in the Delaware Estuary. In the Delaware, as in other estuaries, the Betaproteobacteria are abundant and active in freshwater, the Alphaproteobacteria dominate saline habitats, and the Gammaproteobacteria are evenly distributed throughout the salinity gradient (5, 7, 11). We hypothesized that the distribution of specific types of AAP bacteria in the estuary would be similar to that of phylogenetic groups defined by rRNA genes. To determine the dominant types of AAP bacteria, clone libraries of pufM genes and transcripts from the Delaware River and Bay were constructed. Three ecotypes of pufM were targeted using specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) primer pairs, and the abundances of these ecotypes were examined throughout the salinity gradient of the estuary. We found that two of these ecotypes occupied specific ecological regimes repeatedly over several years, regardless of season.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and environmental parameters.

Samples were obtained on six cruises from the main stem of the Delaware estuary at an approximately 1-m depth. Nutrient concentrations were determined using a Perstorp flowthrough analyzer using colorimetric assays as described previously (26). Temperature, oxygen, and salinity (expressed as unitless values on the practical salinity scale) were measured using a CTD 911 Plus device (SeaBird Electronics, Bellevue, WA). Detailed data on temperature, oxygen, salinity, chlorophyll, and nutrient and calculated seston concentrations are provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

In December 2001, DNA was isolated from free-living bacterioplankton of the Delaware River as described previously (9). In August, October, and November 2002 and July 2004, the bacterial size fraction was isolated from whole water by sequential filtration through 3.0- and 0.8-μm polycarbonate filters (147-mm diameter; Poretics). In March 2005, the bacterial size fraction was isolated as described previously (38). DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and further purified using the IsoQuick nucleic acid extraction kit (ISC Bioexpress, Kaysville, UT) or by cetyltrimethylammonium bromide extraction. Samples intended for RNA purification were preserved in RLT buffer with β-mercaptoethanol (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was purified on RNeasy minicolumns according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Qiagen).

Clone libraries of pufM.

Four pufM libraries were constructed with nucleic acids from surface waters of the Delaware estuary (Table 1). Three samples for library construction were obtained from the river (40o7.6′N, 74o48.4′W), 198 km from the mouth of the estuary, and the bay library sample was from surface water 9 km from the mouth of the estuary (38o6.5′N, 75o6.0′W). Amplification conditions consisted of 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 30 s), annealing at temperatures given in Table 1 for 30 s, and extension at 72°C. Extension times for the 1,500-bp pufLM and 200- to 300-bp pufM fragments were 1 min and 30 s, respectively. All reaction mixtures contained final concentrations of reagents as follows: 1× PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.02 U/μl Taq (Promega), 0.1 μM of each primer (MWG, Germany), and 50 to 200 ng template DNA. Each library was generated from a pool of three reaction mixtures which was concentrated on Microcon columns (molecular weight cutoff, 10,000) by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 5 min. Pooled products were electrophoresed through SeaKem agarose (BioWhittaker, Frederick, MD), excised, and cloned into vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as per the manufacturer's instructions for cloning directly from low-melting-point agarose.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in cloning and ecotype-specific qPCR of pufMa

| Target | Samples | Forward primer | Reference | Reverse primer | Reference | Length (bp)b | Temp (°C)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pufM genes | River, Dec. 2001 | pufLF (CTKTTCGACTTCTGGGTSGG) | 24 | pufM750R (CCCATGGTCCAGCGCCAGAA) | 1 | 1,500 | 58 |

| All pufM genes | River, Aug. 2002 | pufLF | 24 | pufM750R | 1 | 1,500 | 58 |

| All pufM genes | River, Aug. 2002 cDNA | pufM557F (CGCACCTGGACTGGAC) | 1 | pufM750R | 1 | 233 | 58 |

| All pufM genes | Bay, Aug. 2002 | pufM557F | 1 | pufM_WAW (AYNGCRAACCACCANGCCCA) | 40 | 277 | 56 |

| Rhodoferax-like pufM genes | All qPCR samples | RfxF2 (TGGACGGCCGCATTCTCA) | This study | RfxR2 (GCTCAATTTCGCGTTCACCACCAA) | This study | 156 | 60 |

| Rhodobacter-like pufM genes | All qPCR samples | RbaF1 (TGGACGAACCTGTTCAGC) | This study | RbaR1 (CAACTCGCGGTCGCC) | This study | 152 | 50 |

| gammaproteobacterial pufM genes | All qPCR samples | DelMGF1 (ACCGCCGCCTTCTCCAT) | This study | DelMGR1 (CTAGCTCCCGATCGCCACCATA) | This study | 151 | 57 |

| 16S rRNA genes, all bacteria | All qPCR samples | BACT1369F (CGGTGAATACGTTCYCGG) | 36 | PROK1541R (AAGGAGGTGATCCRGCCGCA) | 36 | 192 | 60 |

The sequence of each primer is next to the name in parentheses.

PCR product length in base pairs.

Annealing temperature.

cDNA from the August 2002 river RNA was generated using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen), primed with the reverse primer pufM750R (Table 1). The RNA was treated with DNase I (Invitrogen) at 24°C as per the manufacturer's recommendations. The DNA-free RNA was divided into four reaction mixtures which included all reagents except the RT. Template denaturation and priming were performed as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Three reaction mixtures then received 5 U each of the RT, and the fourth reaction mixture was the no-RT control. First-strand synthesis was at 42°C for 20 min. Following PCR amplification with pufM557F and pufM750R (Table 1), the reactions were examined by gel electrophoresis to confirm that no product was generated in the no-RT control and that the correct-sized product was amplified. The three RT-PCRs were pooled and cloned as described above.

All clone libraries were screened for inserts by colony PCR with the M13 primer sequences flanking the pCR2.1 cloning site. Amplification was carried out with 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 to 90 s. After they were checked by gel electrophoresis, PCR products were purified using the QiaQuick centrifugation method and eluted in 30 μl of elution buffer (Qiagen). The clones from the August 2002 river cDNA and bay DNA libraries were sequenced using BigDye 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, CA) on a Spectrumedix 24-capillary SCE2410 apparatus. The pufLM products from the December 2001 and August 2002 libraries were sequenced from purified plasmid DNA using both the M13F and M13R primers.

Sequences were analyzed and edited using the SeqMan program (DNAStar, Madison, WI). Libraries of pufLM were checked for chimeric clones using the Bellerophon program (17). To detect chimeric clones in the pufM libraries, sequence alignments of the full-length and C-terminal and N-terminal regions were constructed. Phylogenetic trees were generated from the three alignments and manually compared for differences in branch patterns. Sequences of individual clones that did not branch as expected based on the full-length alignment were inspected for chimera formation. From each library, five clones or fewer were rejected as chimeras. The estimated diversities of the clones (Chao I) in the libraries were determined using the DOTUR software package (27). Comparative sequence analyses were performed using the Megalign (DNAStar), MEGA 3.1 (22), BLAST-X, version 2.2.9 (3), and batch BLAST-X (GreenGenes [greengenes.lbl.gov]) software programs.

qPCR of pufM ecotypes.

Three primer sets were designed to amplify specific ecotypes of pufM in qPCR reactions (Table 1). The first type, Rhodoferax-like pufM, was designed to target genes in hypothesized representative freshwater AAP bacteria. The primers were designed to match exactly to sequence coding for the N-terminal end of the DelRiverFos06H03 product (37). The second primer pair, Rhodobacter-like pufM, was designed against an estuarine type of pufM in the fosmid clone DelRiverFos13D03 (37). The last set, the Delaware marine group, was designed to target a dominant group (37%) of pufM genes in the Delaware Bay library (August 2002) constructed in this study. To determine the abundances of all bacteria in whole water and free-living bacterial fractions, qPCR was performed using the BACT1 primer pair as described by Suzuki et al. (36). Template inhibition was checked by performing qPCR assays on serially diluted environmental DNA samples. Regardless of the DNA purification method, the efficiency of amplification ranged from 82 to 88%, as determined by the slope of the regression of logfold DNA dilution with threshold cycle values.

Amplification of all pufM genes was done under the following conditions: 10 min of denaturation and activation of the enzyme at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C (15 s), annealing at the temperatures specified in Table 1 (45 s), and extension and detection at 72°C (45 s). Reactions targeting the 16S rRNA gene were conducted for 30 cycles of amplification. All products were detected by an Applied Biosystems 7500 PCR system using Sybr green I fluorescence. Amplification reactions contained the following: 1× brilliant Sybr green master mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), 80 pg/μl DNA, 0.096 μM (each) primer, and water to a 12.5-μl final reaction volume. All reactions were completed with a dissociation step to check for nonspecific amplification.

Standards were purified fosmid and plasmid clones. The Rhodobacter-like and Rhodoferax-like pufM standards were DelRiverFos13D03 and DelRiverFos06H03, respectively. The standard for the Delaware marine group (gammaproteobacterial pufM) was plasmid clone DB_2E03 from the general pufM library constructed from the August 2002 bay sample. The plasmid was linearized with NotI restriction endonuclease (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA), electrophoresed through agarose, and purified with the GeneClean spin system (Bio101). All standard DNA concentrations were determined using PicoGreen (Invitrogen) fluorescence. Standard reaction mixtures contained approximately 10 to 106 copies and resulted in lines with slopes of −3.4 to −3.8 (average, −3.6 ± 0.2), corresponding to an average amplification efficiency of 90% ± 6%. The standard DNA for the 16S rRNA gene analysis was genomic DNA from Escherichia coli strain EPI300 (Epicentre, Madison, WI). Reactions targeting 16S rRNA genes contained 103 to 108 copies of standard DNA.

To confirm the specificities of the Rhodoferax pufM primer sets, 24 PCR products from representative samples of the entire estuary were cloned and sequenced as described above. The pufM genes amplified by the Rhodoferax-like pufM qPCR primers were on average 88% similar to DelRiverFos06H03 (data not shown). To test the specificity of the gammaproteobacterial pufM primer pair, MG1-F/R, 12 PCR products using this primer pair and DNA from the Delaware Bay (9 km from the mouth of the estuary) collected in August 2002 were cloned and sequenced. All tested clones were 92 to 95% similar to pufM of HTCC2080 and 94 to 98% similar to the dominant type of marine pufM in the Delaware Bay (data not shown). Specificity of the Rhodobacter primer set was tested by comparing the sequences of primers RbaF1 and RbaR1 to those of 426 pufM sequences from the Delaware estuary, Sargasso, Mediterranean, and Red seas, Monterey Bay, and isolates in the Rhodobacter, Roseobacter, and Erythrobacter genera (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The best matches to the forward primer (>78% similar with no mismatches at the 3′ end) were Rhodobacter-like pufM genes from the DNA and RNA libraries from the Delaware Bay and River and the pufM genes of the Oregon Coast isolate R2A163 (35), Rhodobacter blasticus, and the Southern Ocean Roseobacter isolate SO3 (25). The reverse primer matched well to Rhodobacter-like pufM genes from the DNA and RNA libraries from the Delaware Bay and River and to the pufM genes of Rhodobacter capsulatus, Rhodobacter blasticus, and Rhodobacter sphaeroides, as well as to those of Roseobacter isolates R2A163 and OCH114, Roseobacter denitrificans, Roseobacter litoralis, and Roseobacter isolate BS90.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of all pufM clones were deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers EU191236 to EU191609.

RESULTS

Diversity and composition of Delaware estuary pufM libraries.

We constructed three pufM libraries from bacterial nucleic acids from the freshwater end of the Delaware estuary and one from the mouth of the bay (Table 2). Protein sequences were grouped at the 97%-similarity levels as recommended for protein-encoding genes (27). The four libraries were composed of 21 to 33 groups, with coverage ranging from 57 to 79%. The Chao I richness estimates for these four libraries were not statistically different from each other (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Composition and diversity of pufM PCR and RT-PCR libraries from the Delaware estuary in December 2001 and August 2002a

| Library | Total no. of clones | No. of groups | % Coverageb | Chao I |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2001 river | 76 | 33 | 57 | 65 (43, 129) |

| August 2002 river | 95 | 23 | 76 | 37 (26, 79) |

| August 2002 river RNA | 96 | 21 | 79 | 31 (22, 74) |

| August 2002 bay | 107 | 26 | 76 | 61 (36, 152) |

Groups were defined at 3% amino acid sequence divergence. The Chao I index was calculated using the DOTUR software program. Numbers in parentheses are 95% confidence limits.

Percent coverage was calculated with the formula [1 − (n/N)] × 100, where n is the number of singleton clones and N is the total number of sequences.

We compared the Delaware River and Bay clones to known pufM genes using BLASTX (Table 3). The December river library was dominated by clones (88% of all clones) closely related to pufM of DelRiverFos06H03, which is hypothesized to be representative of freshwater AAP Betaproteobacteria (37). The August river DNA library also contained pufM genes related to the betaproteobacterial DelRiverFos06H03 and other freshwater pufM genes from Lake Fryxell. Approximately half of the August river pufM genes were related to the pufM gene of the cultured gammaproteobacterium Congregibacter litoralis KT71 (15), but the average similarity of the amino acid sequences was only 92% (Table 3). The genes similar to Rhodobacter and Rhodobacter-like pufM genes, including that of the hypothesized estuarine type in fosmid clone DelRiverFos13D03 (37), comprised less than 5% of the cloned pufM genes in both river DNA libraries (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

BLAST analysis of Delaware estuary pufMa

| Library | Top BLASTX hit | Accession no. | Phylogenetic groupb | % of clones | Avg % identityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2001 river | DelRiverFos06H03 | AAX48200 | Beta | 88 | 99 |

| Roseateles depolymerans | BAB19668 | Beta | 4 | 94 | |

| Lake Fryxell c1 | AAO62372 | Alpha-1 | 3 | 96 | |

| Lake Fryxell c7 | AAO62378 | Alpha-3 | 1 | 100 | |

| Rhodobacter blasticus | BAA22642 | Alpha-3 | 1 | 93 | |

| Thiocapsa roseopersicina | CAD66535 | Gamma | 1 | 93 | |

| Thiocystis gelatinosa | BAA22650 | Gamma | 1 | 90 | |

| August 2002 river | Congregibacter litoralis KT71 | ZP_01104362 | Gamma | 51 | 92 |

| DelRiverFos06H03 | AAX48200 | Beta | 16 | 98 | |

| Lake Fryxell c1 | AAO62372 | Alpha-1 | 15 | 93 | |

| Lake Fryxell c8 | AAO62379 | Alpha-1 | 8 | 89 | |

| Blastomonas sp. strain NT12 | BAA25728 | Alpha-4 | 7 | 95 | |

| Rhodobacter blasticus | BAA22642 | Alpha-3 | 2 | 95 | |

| DelRiverFos13D03 | AAX48162 | Alpha-3 | 1 | 98 | |

| August 2002 river cDNA | DelRiverFos06H03 | AAX48200 | Beta | 30 | 94 |

| Lake Fryxell c1 | AAO62372 | Alpha-1 | 19 | 94 | |

| Blastomonas natatoria | BAA25728 | Alpha-4 | 14 | 90 | |

| Congregibacter litoralis KT71 | ZP_01104362 | Gamma | 14 | 92 | |

| Roseiflexus sp. strain RS-1 | ZP_01355478 | Green non-sulfur | 7 | 72 | |

| DelRiverFos13D03 | AAX48162 | Alpha-3 | 4 | 98 | |

| Jannaschia sp. strain CCS1 | YP_508114 | Alpha-3 | 4 | 94 | |

| Roseococcus thiosulfatophilus | AAL57746 | Alpha-1 | 3 | 86 | |

| Porphyrobacter neustonensis | BAA25904 | Alpha-4 | 3 | 93 | |

| Lake Fryxell c8 | AAO62379 | Alpha-1 | 1 | 92 | |

| Rhodobacter veldkampii | BAC54030 | Alpha-3 | 1 | 92 | |

| August 2002 bay | EBAC000-29C02 | AAM48603 | Gamma | 37 | 95 |

| Congregibacter litoralis KT71 | ZP_01626201 | Gamma | 32 | 95 | |

| Rhodobacter blasticus | BAA22642 | Alpha-3 | 21 | 89 | |

| Roseobacter sp. strain SYOP2 | AAT79391 | Alpha-3 | 3 | 98 | |

| Porphyrobacter sanguineus | BAA25723 | Alpha-4 | 3 | 87 | |

| Jannaschia sp. strain CCS1 | YP_508114 | Alpha-3 | 2 | 95 | |

| Blastomonas sp. strain NT12 | BAA77030 | Alpha-4 | 1 | 90 | |

| Hawaii envhot3 | AAL02391 | Gamma | 1 | 95 |

All pufM genes were compared to database sequences (January 2007) using BLASTX. Sequences similar to those boldfaced in the table were targeted by qPCR in this study.

Phylogenetic group assignment of each top BLAST hit was based on 16S rRNA for cultured bacteria and on pufM for uncultured bacteria. Alpha, beta, and gamma refer to subclasses of the Proteobacteria. Lake Fryxell clone 1 and 7 pufM phylogenetic affiliations were assigned to the alpha-1 and alpha-3 subclasses of Proteobacteria (19). The pufM gene in clone EBAC000-29C02 was assigned to the Gammaproteobacteria (15).

Average pufM product percent amino acid identity to the top BLASTX hit for all clones in each library is noted.

The composition of the river cDNA library was similar to that of its DNA counterpart except that the gammaproteobacterial gene did not dominate (Table 3). Approximately 30% of the pufM transcripts in the river sample were closely related to DelRiverFos06H03 pufM, with a corresponding average amino acid similarity of 94% (Table 3), and another 20% were similar to Lake Fyxell pufM genes. Only 4% of pufM in cDNA clones was similar to estuarine DelRiverFos13D03 pufM. Genes most similar to those of the Gammaproteobacteria comprised approximately 14% of the cDNA library.

In contrast to the river DNA libraries, the August bay DNA library was dominated by genes similar to the pufM genes from the Monterey Bay BAC clone EBAC000-29C02 (37% of all clones) and Congregibacter litoralis KT71 (32%) (Table 3). The pufM genes in Delaware Bay clones similar to the pufM gene in the Monterey Bay BAC clone ranged in similarity from 84 to 98%, with an average of 95% (Table 3). Products of the Congregibacter-like pufM genes were on average 95% similar at the amino acid level. The remaining 27% of the bay library was composed of clones with genes similar to the pufM genes from cultured representatives in the alpha-3 and alpha-4 (Roseobacter and Erythrobacter) subclasses of the Proteobacteria. In the bay library, no pufM gene was related to that of the estuarine DelRiverFos13D03 fosmid clone, and there were no freshwater representatives in this library.

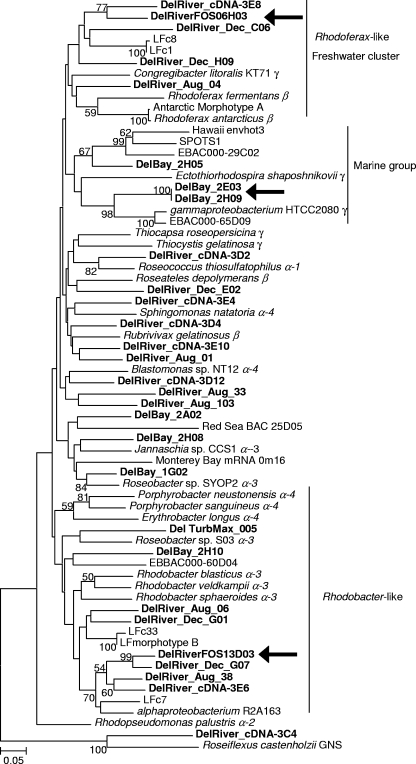

We further examined the relationships of the Delaware estuary pufM genes and transcripts with other pufM genes by constructing a phylogenetic tree with dominant members of the Delaware estuary libraries (Fig. 1). The tree contained a cluster of Rhodoferax-like freshwater pufM sequences, comprised of Delaware River pufM genes and transcripts as well as pufM sequences from Lake Fryxell (19). The remaining clusters in the tree contained pufM genes from cultured and uncultured representatives isolated from marine and coastal environments. One group contained pufM genes similar to those of the alpha-3 (Rhodobacter- and Roseobacter-like) and alpha-4 (Erythrobacter-like) subgroups of Proteobacteria. The hypothesized estuarine type of pufM, DelRiverFos13D03 fosmid clone, and river DNA and cDNA clones fell in this group. The pufM clones from the August 2002 bay and March 2005 turbidity maximum (66 km from the mouth of the bay) samples also clustered with these sequences. The last cluster of pufM genes, the Delaware marine group, was composed of genes from Delaware Bay clones and from the hypothesized gammaproteobacterial Monterey Bay bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones, EBAC000-29C02 and -65D09. The Delaware marine group cluster also contained the pufM gene from the gammaproteobacterium HTCC2080, isolated from oligotrophic oceanic waters (6), and a pufM clone from San Pedro Channel (SPOTS1).

FIG. 1.

Relationships of pufM genes in the Delaware River and Bay. Delaware clones from the river (DelRiver), turbidity maximum (Del TurbMax) and bay (DelBay) are in bold. Lake Fryxell clones are abbreviated “LF.” Alpha-, beta-, and gammaproteobacterial clusters are designated on the basis of the 16S rRNA gene. α-2, α-3, and α-4 refer to subclasses of Alphaproteobacteria. Delaware cDNA clones are indicated (cDNA). Fosmid clones described previously (38) are marked DelRiverFOS. Ecotypes targeted by qPCR are indicated by arrows (100% match of primers to fosmid or plasmid sequences). The scale bar represents 5 nucleotide substitutions per 100 positions. Chloroflexus aurantiacus was the outgroup.

Quantitative mapping of pufM ecotypes.

To examine the distribution of pufM genes along the salinity gradient of the estuary, we designed qPCR primers to target three major groups of pufM genes hypothesized to be abundant in the estuary (Table 1). One was the pufM gene of the fosmid clone DelRiverFos06H03, thought to be representative of freshwater AAP bacteria (37). The second type, Rhodobacter-like, was hypothesized to be ubiquitous throughout the estuary. This ecotype comprised less than 5% of the clones in DNA libraries from either end of the estuary (Table 3), but genes related to pufM from DelRiverFos13D03 and other Rhodobacter-like pufM genes made up approximately 10% of the August river cDNA library. Additionally, since Rhodobacter species are associated with particles (12) and a large proportion of estuarine AAP bacteria are associated with particles (38), we hypothesized that pufM genes in this clade would be abundant throughout the estuary.

The third ecotype targeted by qPCR, the Delaware marine group, was a dominant pufM sequence in the Delaware Bay library, comprising 37% of the clones (Table 3), and was similar to genes from Monterey Bay BAC clones and the gammaproteobacterium HTCC2080 (6). It was distinct, however, from the second-most-abundant gammaproteobacterial pufM gene in the Delaware Bay library. This pufM clade, comprising 32% of the Delaware Bay clones, was a loose cluster of genes that were on average 95% similar to pufM of Congregibacter litoralis. This type of pufM gene was not targeted by qPCR, since these sequences did not fall in a tight cluster.

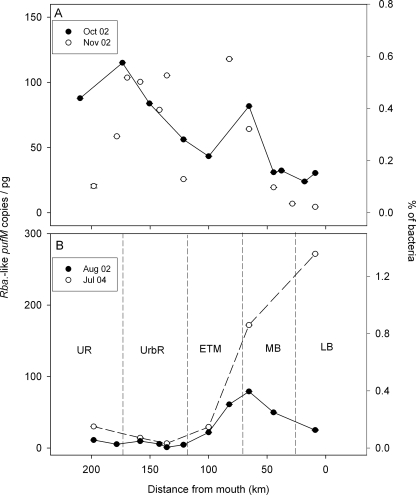

Two of the pufM types varied consistently with salinity in the Delaware estuary (Fig. 2). The Delaware marine group was restricted to waters with a salinity of >11 (Fig. 2A). The abundance of this pufM gene covaried significantly with salinity (r = 0.57; P < 0.001; n = 49) and was inversely correlated to nitrate concentrations (r = −0.69; P < 0.001; n = 27). At the mouth of the bay in 2002, this gene ranged from 50 to 125 copies/pg of total bacterial DNA, corresponding to 0.25 to 0.63% of bacteria, assuming 2 fg DNA per bacterial cell. This pufM gene was not detected at significant levels in July 2004. In contrast, the Rhodoferax-like pufM ecotype was restricted to waters with a salinity of <5, and its abundance was inversely correlated with salinity (r = −0.65; P < 0.001; n = 49) and chlorophyll (r = −0.41; P < 0.01; n = 39) regardless of the season (Fig. 2B). Additionally, this freshwater pufM sequence positively correlated with nitrate (r = 0.51; P < 0.01; n = 27) and phosphate concentrations (r = 0.58; P < 0.01; n = 27). In three transects, maximum abundances of Rhodoferax-like pufM were similar to those of the marine group, ranging from 40 to 150 copies/pg, which corresponds to 0.2 to 0.75% of the total bacterial community. In August 2002, this type was not abundant even in the least-saline stations, reaching only 20 copies/pg (Fig. 2B). The hypothesized estuarine Rhodobacter-like pufM gene was ubiquitous in the estuary but did not vary consistently through the salinity gradient (Fig. 3). This pufM gene was more abundant in the lower-salinity waters of the estuary (125 km to 200 km from the mouth) during October and November 2002 (Fig. 3A), whereas in August 2002 and July 2004, the Rhodobacter-like pufM gene was more abundant in the higher-salinity stations (Fig. 3B). In the riverine section of the estuary, Rhodobacter-like pufM genes were not as abundant as Rhodoferax-like pufM, reaching only 120 copies/pg DNA or about 0.6% of all bacteria (Fig. 3A). The abundance was not significantly correlated with nutrient concentrations (r < 0.31; P > 0.05; n = 27) or chlorophyll (r = 0.12; P > 0.05; n = 38).

FIG. 2.

Distribution of two pufM ecotypes normalized to pg of total DNA in the Delaware estuary. Ecotypes targeted by qPCR were Delaware marine group (gammaproteobacterial) (A) or Rhodoferax-like (betaproteobacterial) (B) pufM genes. Error bars show the standard errors for four qPCRs. The average salinity for all four transects is plotted in panel B. The percentage of bacteria was calculated assuming 2 fg DNA per bacterial cell.

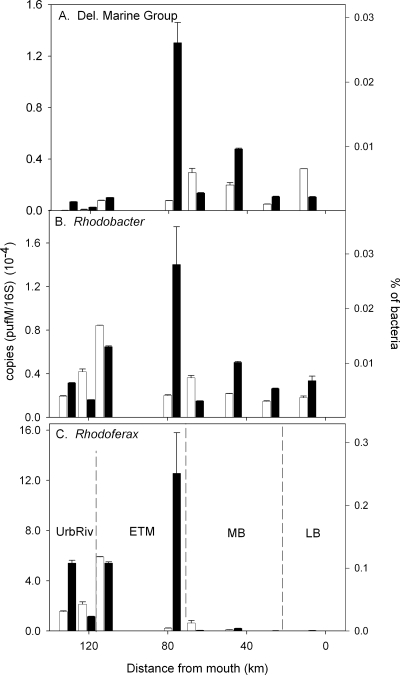

FIG. 3.

Distribution of Rhodobacter-like pufM ecotypes, normalized to pg of total DNA, in the Delaware estuary in autumn (A) or summer (B). Error bars, each based on the standard error for four qPCRs, are smaller than the symbols. Dashed vertical lines in panel B delineate the five regions of the estuary: LB, lower bay (0 to 25 km); MB, midbay (25 to 70 km); ETM, turbidity maximum (70 to 115 km); UrbR, urban river (115 to 175 km); UR, upper river (175 to 215 km). The percentage of bacteria was calculated assuming 2 fg DNA per bacterial cell.

We estimated the contribution of these three ecotypes to the bacterial community as a whole and to the AAP bacterial community. In the entire data set, the sum of the three types of AAP bacteria comprised up to 1.6% of bacteria, with an average of 0.14% (calculated from data in Fig. 2 and 3), assuming one copy of pufM per genome and two 16S rRNA genes or 2 fg DNA per bacterial cell (14, 28). These estimates were also compared to the total AAP bacterial abundance estimated previously (38) by pufM qPCR (Table 4). In five cruises, the three types of pufM comprised on average 5.7% of all bacteria containing the pufM gene (Table 4). In the middle portions of the estuary, the contribution of the three pufM types to the total bacterial and AAP bacteria community averaged about 0.08% and 4.3%, respectively. In the lower bay and upper river, the three types of AAP bacteria examined in this study were more abundant and comprised 12 and 8% of the AAP bacterial community, respectively (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Contributions of three ecotypes to total AAP bacterial communities in the Delaware estuarya

| Regionb (nc) | % of bacteria (±SE) containing pufM

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodobacter-like | Rhodoferax-like | Marine group | Sum | |

| Lower bay (7) | 3.1 (0.15) | 0.0049 (0.006) | 8.8 (0.21) | 12.0 (4.6) |

| Midbay (15) | 3.9 (0.11) | 0.044 (0.25) | 2.0 (0.13) | 6.0 (1.7) |

| Turb. max. (9) | 2.8 (0.20) | 0.19 (0.037) | 0.017 (0.0018) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| Urban river (18) | 1.9 (0.06) | 1.5 (0.11) | 0.0047 (0.0067) | 3.5 (0.72) |

| Upper river (6) | 2.8 (0.031) | 5.0 (0.058) | 0.00010 (0.000014) | 7.8 (2.6) |

| Entire estuary (55) | 2.9 (0.55) | 1.1 (0.79) | 1.7 (2.9) | 5.7 (0.90) |

The Rhodobacter-like, Rhodoferax-like, and marine group (gammaproteobacterial) pufM genes were compared to the total AAP bacterial community by normalizing to total pufM abundance (36). “Sum” is the total of the three percentages.

Regions were defined as in reference 37 by distance from the mouth of the bay: lower bay (0 to 25 km), Midbay (25 to 70 km), turbidity maximum (Turb. max.) (70 to 115 km), urban river (115 to 175 km), or upper river (175 to 215 km).

n, number of samples in each region from five cruises (August, October, and November 2002, July 2004, and March 2005).

Particle-associated pufM genes.

To determine if specific groups of AAP bacteria were associated with particles, we estimated abundances of particle-attached pufM-containing bacteria by subtracting values in the free-living fraction from those of the corresponding whole water during a transect in 2005 (Fig. 4). The variation of the three pufM types in the total community throughout the estuary in 2005 was similar to that for pufM in the free-living fraction in 2002 and 2004 (Fig. 2 and 3). However, in contrast to previous transects, Rhodoferax-like pufM was more abundant than the other two ecotypes. The estimated fraction of bacteria comprising the three pufM ecotypes was 10-fold less in 2005 than in 2002 to 2004, in part due to how the bacteria were collected (whole water or GF/D filtration versus 0.8-μm polycarbonate filtration). About 80 km from the mouth of the bay (Fig. 4), particle-associated AAP bacteria were a very large fraction of the total, probably because of high particle concentrations (38). But overall, the average (± standard error) percentages of particle-associated pufM genes were 22% ± 36%, 12% ± 31%, and 24% ± 38% for the Delaware marine group, Rhodobacter-like, and Rhodoferax-like types, respectively (calculated from data in Fig. 4). These percentages do not differ significantly (analysis of variance, P > 0.05) and are also not statistically different from 39% ± 18%, the average percentage of total AAP bacteria associated with particles in the Delaware Estuary (38).

FIG. 4.

Distribution of three pufM ecotypes in whole water and the free-living bacterial fraction in March 2005. Abundance of Delaware marine group (A), Rhodobacter-like (B), or Rhodoferax-like (C) pufM genes was normalized to 16S rRNA gene abundance. The percentage of bacteria was calculated assuming two 16S rRNA gene copies per bacterial cell.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to examine relationships among estuarine AAP bacteria and to determine if ecotypes inferred from phylogenetic analyses varied systematically within the salinity gradient of the estuary. We hypothesized that the distribution of AAP bacterial types would follow the patterns of bacterial groups previously determined using the 16S rRNA gene. Groups of freshwater, brackish, and marine ecotypes of pufM sequences were determined by phylogenetic analyses, and these patterns were confirmed by qPCR abundance estimates through the estuary. In contrast to our initial hypothesis, the distribution of the three types of pufM genes did not coincide entirely with the patterns of Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria typically observed in studies of rRNA genes in estuaries.

Salinity probably influenced the distribution of the betaproteobacterial Rhodoferax-like AAP bacteria in the estuary. The hypothesized freshwater pufM genes clustered with pufM genes from organisms originally isolated from low-salinity environments, such as Rhodoferax and Roseateles, and from uncultured bacteria from the Delaware River and Lake Fryxell. In this study, Rhodoferax-like pufM genes were restricted to waters with a salinity of <5. These data are supported by the observation that Rhodoferax-like pufM genes are restricted to estuarine or freshwaters in the Global Ocean Sampling data set (41). The distribution of this group of pufM genes is consistent with the distribution of Betaproteobacteria in the Delaware and other estuaries (5, 7, 11). This restriction to low-salinity waters, however, may be in part explained by the inverse relationship between nutrient concentrations and salinity in the Delaware (r = −0.75; P < 0.001; n = 27) and other estuaries (39).

Unexpectedly, our qPCR results indicated that the abundance of the gammaproteobacterial AAP bacteria covaried with salinity. Studies using 16S rRNA gene clone libraries or fluorescence in situ hybridization indicate that the Gammaproteobacteria do not vary systematically with salinity (7, 10). The distribution observed in this study may be related to the trophic status of these waters (as indicated by nitrate concentrations), not just salinity. In the Delaware estuary, the positive relationship between gammaproteobacterial AAP bacteria and salinity may be due in fact to nitrate, because there is an inverse relationship between nitrate concentrations and salinity in the estuary (r = −0.75; P < 0.001; n = 27).

Additionally, different groups of gammaproteobacterial AAP bacteria may be adapted to different trophic conditions. AAP bacteria in the OM60 clade of Gammaproteobacteria appear to be comprised of two groups based on individual gene phylogeny and synteny, and these groups occupy distinct habitats (41). In the Delaware estuary, there were two types of gammaproteobacterial pufM genes, which are similar to pufM genes in other estuarine and coastal communities. The first type, the most abundant one in the Delaware Bay library, is similar to the pufM gene from the gammaproteobacterium HTCC2080 (6) and the Monterey Bay BAC clone EBAC000-65D09 (4) (Fig. 1). This type accounts for 37% of the pufM genes amplified by the Delaware marine group qPCR primers (Table 3). The second type, related to Congregibacter litoralis (15), comprised a large portion of the pufM genes and mRNA transcripts from the Delaware River and approximately one-third of pufM clones from the Delaware Bay. Unfortunately, the average percent similarity of Delaware estuary pufM genes to the C. litoralis pufM gene was low (Table 3), resulting in this cluster being too loose to be examined by a single qPCR assay.

The qPCR data indicated that the Rhodobacter-like ecotype covaried with salinity and that there was a seasonal influence on this relationship. This seasonal difference is not explained by nitrate, since nitrate concentrations are always highest in the urban river and at the turbidity maximum of the estuary, regardless of season (29). Instead, it may be partly explained by the broad range of Rhodobacter- and Roseobacter-like AAP genes amplified by this primer set. The nucleotide sequences of the forward and reverse Rba qPCR primers match, on average, 64 and 86%, respectively, to nucleotide sequences of representative Rhodobacter and Roseobacter pufM genes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Subgroups of bacteria in the Rhodobacter group, particularly those related to Sagittula stellata and Ruegeria spp., vary systematically with season and inorganic nitrogen and particulate organic matter concentrations in a salt marsh creek (12), although pufM genes have not been found in cultured representatives of these bacterial subgroups. More data on AAP bacteria in the Rhodobacter clade are needed.

Other environmental factors probably influence the survival of specific groups of AAP bacteria in the estuary. Light attenuation in the turbidity maximum of the Delaware estuary is high, and low light availability may negatively influence some AAP bacteria. This, along with increasing allochthonous nutrient loads, may in part explain the low abundance of the Delaware marine group in the Delaware River. This group may be representative of AAP bacteria that are adapted to more oligotrophic, clearer waters, such as those of coastal areas and open oceans (6, 15). Additionally, top-down factors, such as grazing, could also preferentially remove certain ecotypes, such as the betaproteobacterial Rhodoferax, from the midestuary. Some Betaproteobacteria are fast-growing, large cells which are controlled by grazing pressure (32). Since the cell size of AAP bacteria can be large in coastal and oceanic environments (8, 31), preferential grazing on larger cells (30) may help to explain the abundance of certain types of AAP bacteria.

Detrital particle concentrations also appear to be important in affecting the distribution of AAP bacteria, since our qPCR results indicated that a large fraction of all three types of AAP bacteria was associated with particles. The association of AAP bacteria with particles may be due to oxygen availability (38). In culture, Congregibacter litoralis forms aggregates and grows optimally in semiaerobic conditions (15). Additionally, the betaproteobacterial isolate Roseateles depolymerans increases production of bacteriochlorophyll a and reaction center proteins under microaerobic conditions (0.2 to 2% oxygen) (33). The particle attachment preference of total AAP bacteria (38), as well as the findings in this study, suggest that association with particles is common among all AAP bacteria, particularly in coastal and estuarine environments. Particle attachment by AAP bacteria may even be common in the open ocean, since in the Sargasso Sea, the estimated AAP abundance was twofold lower in free-living bacterioplankton (<0.8 μm) than in the 3- to 20-μm fraction (41).

The qPCR assays targeted three pufM types hypothesized to be ecologically interesting based on the clone library results and a previous fosmid library study of AAP bacteria (37). In total, the three groups examined by qPCR comprised on average only 5.7% of all pufM genes in the estuary, much lower than what we expected based on the clone library results. This difference may reflect the well-known problems with trying to use clone library results for quantitative analyses, and it also suggests a higher diversity of AAP bacteria than what was captured in the four PCR libraries constructed for this study.

This study was the first to examine how specific types of AAP bacteria vary with respect to environmental parameters such as salinity and nutrients. The distribution of the betaproteobacterial pufM types within the estuary as determined by qPCR was consistent with what we expected based on its phylogenetic affiliation. However, the estuarine distribution of the alpha-3-proteobacterial Rhodobacter-like and gammaproteobacterial pufM genes did not coincide with what had previously been observed in studies using the 16S rRNA gene. Further investigations into the distribution and activity of these and other types of AAP bacteria, such as those containing the gammaproteobacterial pufM genes, may provide further clues to potentially diverse ecological adaptations by AAP bacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Vanessa Michelou, Ogugua Anene-Maidoh, and the captain and crew of the R/V Cape Henlopen and R/V Hugh R. Sharp for assistance with sample collection. Chris Sommerfield and Jon Sharp provided valuable support as chief scientists of cruises in the Delaware estuary.

This work was supported by DOE grant DE-FG02-97ER62479 and NSF MCB-0453993.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 May 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achenbach, L. A., J. Carey, and M. T. Madigan. 2001. Photosynthetic and phylogenetic primers for detection of anoxygenic phototrophs in natural environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2922-2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allgaier, M., H. Uphoff, A. Felske, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 2003. Aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis in Roseobacter clade bacteria from diverse marine habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5051-5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Meyers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Béjà, O., M. T. Suzuki, J. F. Heidelberg, W. C. Nelson, C. M. Preston, T. Hamada, J. A. Eisen, C. M. Fraser, and E. F. DeLong. 2002. Unsuspected diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Nature 415:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvier, T. C., and P. A. del Giorgio. 2002. Compositional changes in free-living bacterial communities along a salinity gradient in two temperate estuaries. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:453-470. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho, J. C., M. D. Stapels, R. M. Morris, K. L. Vergin, M. S. Schwalbach, S. A. Givan, D. F. Barofsky, and S. J. Giovannoni. 2007. Polyphyletic photosynthetic reaction centre genes in oligotrophic marine Gammaproteobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1456-1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cottrell, M. T., and D. L. Kirchman. 2004. Single-cell analysis of bacterial growth, cell size, and community structure in the Delaware estuary. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 34:139-149. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cottrell, M. T., A. Mannino, and D. L. Kirchman. 2006. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the Mid-Atlantic Bight and the North Pacific Gyre. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:557-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cottrell, M. T., L. A. Waidner, L. Yu, and D. L. Kirchman. 2005. Bacterial diversity of metagenomic and PCR libraries from the Delaware River. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1883-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crump, B. C., E. V. Armbrust, and J. A. Baross. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of particle-attached and free-living bacterial communities in the Columbia river, its estuary, and the adjacent coastal ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3192-3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crump, B. C., C. S. Hopkinson, M. L. Sogin, and J. E. Hobbie. 2004. Microbial biogeography along an estuarine salinity gradient: combined influences of bacterial growth and residence time. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1494-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dang, H. Y., and C. R. Lovell. 2002. Seasonal dynamics of particle-associated and free-living marine Proteobacteria in a salt marsh tidal creek as determined using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Environ. Microbiol. 4:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eiler, A. 2006. Evidence for the ubiquity of mixotrophic bacteria in the upper ocean: implications and consequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:7431-7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogel, G. B., C. R. Collins, J. Li, and C. F. Brunk. 1999. Prokaryotic genome size and SSU rDNA copy number: estimation of microbial relative abundance from a mixed population. Microb. Ecol. 38:93-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs, B. M., S. Spring, H. Teeling, C. Quast, J. Wulf, M. Schattenhofer, S. Yan, S. Ferriera, J. M. Johnson, F. O. Glöckner, and R. Amann. 2007. Characterization of a marine gammaproteobacterium capable of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:2891-2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu, Y., H. Du, N. Z. Jiao, and Y. Zeng. 2006. Abundant presence of the gamma-like proteobacterial pufM gene in oxic seawater. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 263:200-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber, T., G. Faulkner, and P. Hugenholtz. 2004. Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 20:2317-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imhoff, J. F. 2001. True marine and halophilic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 176:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karr, E. A., W. M. Sattley, D. O. Jung, M. T. Madigan, and L. A. Achenbach. 2003. Remarkable diversity of phototrophic purple bacteria in a permanently frozen Antarctic lake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4910-4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koblížek, M., O. Béjà, R. R. Bidigare, S. Christensen, B. Benitez-Nelson, C. Vetriani, M. K. Kolber, P. G. Falkowski, and Z. S. Kolber. 2003. Isolation and characterization of Erythrobacter sp. strains from the upper ocean. Arch. Microbiol. 180:327-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolber, Z. S., F. G. Plumley, A. S. Lang, J. T. Beatty, R. E. Blankenship, C. L. VanDover, C. Vetriani, M. Koblížek, C. Rathgeber, and P. G. Falkowski. 2001. Contribution of aerobic photoheterotrophic bacteria to the carbon cycle in the ocean. Science 292:2492-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lami, R., M. T. Cottrell, J. Ras, O. Ulloa, I. Obernosterer, H. Claustre, D. L. Kirchman, and P. Lebaron. 2007. High abundances of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria in the South Pacific Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4198-4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagashima, K. V. P., A. Hiraishi, K. Shimada, and K. Matsuura. 1997. Horizontal transfer of genes coding for the photosynthetic reaction centers of purple bacteria. J. Mol. Evol. 45:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oz, A., G. Sabehi, M. Koblížek, R. Massana, and O. Béjà. 2005. Roseobacter-like bacteria in Red and Mediterranean Sea aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:344-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preen, K., and D. L. Kirchman. 2004. Microbial respiration and production in the Delaware Estuary. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 37:109-119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schloss, P. D., and J. Handelsman. 2005. Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1501-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwalbach, M. S., and J. A. Fuhrman. 2005. Wide-ranging abundances of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the world ocean revealed by epifluorescence microscopy and quantitative PCR. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50:620-628. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharp, J. H., C. H. Culberson, and T. M. Church. 1982. The chemistry of the Delaware Estuary: general considerations. Limnol. Oceanogr. 27:1015-1028. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherr, B. F., E. B. Sherry, and J. McDaniel. 1992. Effect of protistan grazing on the frequency of dividing cells in bacterioplankton assemblages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2381-2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieracki, M. E., I. C. Gilg, E. C. Thier, N. J. Poulton, and R. Goericke. 2006. Distribution of planktonic aerobic anoxygenic photoheterotrophic bacteria in the northwest Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51:38-46. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Šimek, K., K. Horna'k, J. Jezbera, M. Mašín, J. Nedoma, J. M. Gasol, and M. Schauer. 2005. Influence of top-down and bottom-up manipulations on the R-BT065 subcluster of Betaproteobacteria, an abundant group in bacterioplankton of a freshwater reservoir. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2381-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suyama, T., T. Shigematsu, T. Suzuki, Y. Tokiwa, T. Kanagawa, K. V. P. Nagashima, and S. Hanada. 2002. Photosynthetic apparatus in Roseateles depolymerans 61A is transcriptionally induced by carbon limitation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1665-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suyama, T., T. Shigematsu, S. Takaichi, Y. Nodasaka, S. Fujikawa, H. Hosoya, Y. Tokiwa, T. Kanagawa, and S. Hanada. 1999. Roseateles depolymerans gen. nov., sp. nov., a new bacteriochlorophyll a-containing obligate aerobe belonging to the beta-subclass of the Proteobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:449-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki, M. T., M. S. Rappe, Z. W. Haimberger, H. Winfield, N. Adair, J. Strobel, and S. J. Giovannoni. 1997. Bacterial diversity among small-subunit rRNA gene clones and cellular isolates from the same seawater sample. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:983-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki, M. T., L. T. Taylor, and E. F. DeLong. 2000. Quantitative analysis of small-subunit rRNA genes in mixed microbial populations via 5′-nuclease assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4605-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waidner, L. A., and D. L. Kirchman. 2005. Aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis genes and operons in uncultured bacteria in the Delaware River. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1896-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waidner, L. A., and D. L. Kirchman. 2007. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria attached to particles in turbid waters of the Delaware and Chesapeake estuaries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3936-3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshiyama, K., and J. H. Sharp. 2006. Phytoplankton response to nutrient enrichment in an urbanized estuary: apparent inhibition of primary production by overeutrophication. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51:424-434. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yutin, N., M. T. Suzuki, and O. Béjà. 2005. Novel primers reveal wider diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8958-8962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yutin, N., M. T. Suzuki, H. Teeling, M. Weber, J. C. Venter, D. B. Rusch, and O. Béjà. 2007. Assessing diversity and biogeography of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in surface waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans using the Global Ocean Sampling expedition metagenomes. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1464-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.