Abstract

Vibrio vulnificus is a human and animal pathogen that carries the highest death rate of any food-borne disease agent. It colonizes shellfish and forms biofilms on the surfaces of plankton, algae, fish, and eels. Greater understanding of biofilm formation by the organism could provide insight into approaches to decrease its load in filter feeders and on biotic surfaces and control the occurrence of invasive disease. The capsular polysaccharide (CPS), although essential for virulence, is not required for biofilm formation under the conditions used here. In other bacteria, increased biofilm formation often correlates with increased exopolysaccharide (EPS) production. We exploited the translucent phenotype of acapsular mutants to screen a V. vulnificus genomic library and identify genes that imparted an opaque phenotype to both CPS biosynthesis and transport mutants. One of these encoded a diguanylate cyclase (DGC), an enzyme that synthesizes bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP). This prompted us to use this DGC, DcpA, to examine the effect of elevated c-di-GMP levels on several developmental pathways in V. vulnificus. Increased c-di-GMP levels induced the production of an EPS that was distinct from the CPS and dramatically enhanced biofilm formation and rugosity in a CPS-independent manner. However, the EPS could not compensate for the loss of CPS production that is required for virulence. In contrast to V. cholerae, motility and virulence appeared unaffected by elevated levels of c-di-GMP.

Bacteria use diverse small-molecule signaling pathways to relate extracellular environmental conditions to their intracellular physiological status and adapt accordingly (7). A novel information relay paradigm uses the second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP) (34, 35, 73, 74). c-di-GMP is known to regulate many distinct cellular processes in bacteria, including cellulose production (75-77), biofilm formation (3, 7, 73, 79), rugose colony morphology (46, 47, 69), motility (11, 31, 38), and virulence factor production (6, 17, 42, 47, 78, 85). In general, increases in intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations enhance the expression of adhesion factors while repressing motility and virulence gene expression.

The proteins responsible for the synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP are diguanylate cyclases (DGC) and phosphodiesterases (PDE), respectively (77). DGC contain a conserved GGDEF domain (14, 35, 73, 74) that is commonly amalgamated with other well-recognized regulatory motifs, such as GAF, PAS, REC, HAMP, PBPb, CBS, and the N-terminal receiver domain of two-component signal transduction systems (19, 20, 30, 35, 67, 99). For example, GAF is a noncatalytic GTP-binding domain that was first discovered as a conserved region in cyclic nucleotide PDE (9), and a study investigating the enzymatic activity of proteins containing the GGDEF and GAF domains determined that they possessed DGC activity (79).

Vibrio vulnificus is a marine bacterium that is pathogenic to humans and animals (48, 81, 83). It colonizes shellfish and has been found attached to plankton, algae, eels, and fish (5, 8, 41, 50, 56, 59). Infection occurs via wound contamination or ingestion of contaminated shellfish. The fatality rate of susceptible patients with primary septicemia is greater than 50%, and it carries the highest death rate of any food-borne disease agent (86). The capsular polysaccharide (CPS) mediates resistance of the bacteria to complement-mediated bacteriolysis and phagocytosis (48). Hence, the CPS is essential for virulence.

V. vulnificus can generate morphologically and physiologically distinct phase variants (opaque, translucent, smooth, and rugose). The role of the CPS in phase variation and biofilm formation has been investigated to some degree. Translucent variants have little or no CPS (29, 72, 91-93, 97), yet they were shown to produce better biofilms than the parental opaque colonies (36). It was also observed that a defined CPS mutant yielded rugose colonies in a reversion assay, suggesting that the rugose phenotype in V. vulnificus can develop independently of capsule production (24). Rugose variants also produce the most robust biofilms (24). Thus, the CPS likely does not contribute to biofilm formation or rugose colony development in V. vulnificus.

In other bacteria, increased colonization, biofilm formation, and rugosity often correlate with increased exopolysaccharide (EPS) production (1, 12, 18, 33, 43, 44, 51, 69, 70, 95, 96). A previous study examining the effect of adenylate cyclase (cya) on CPS production revealed that a cya mutant, although initially translucent and acapsular, became partially opaque if cells were cultured for more than 24 h (39). Furthermore, although an ntrC mutant was shown to express significantly less CPS than the wild type (wt), the mutant remained opaque (37). These observations suggested that V. vulnificus was able to produce an EPS in addition to the CPS, but no such polysaccharide has ever been detected and the roles of other factors in the aforementioned developmental pathways have not been investigated.

A greater understanding of biofilm formation by the organism could provide insight into approaches to decrease the Vibrio load in filter feeders and control the occurrence of invasive disease. Here, we took advantage of the translucent phenotype of three V. vulnificus mutants that were deficient in CPS biosynthesis and transport to sequentially screen a genomic library of strain 27562 and identify genes that restored opacity to each of the mutants. One gene, designated dcpA (for diguanylate cyclase protein A), coded for a member of the GGDEF domain-containing protein family of diguanylate cyclases (DGC) that synthesize c-di-GMP. This prompted us to use DcpA to examine the effect of increased levels of c-di-GMP on biofilm formation, rugose colony formation, motility, and virulence in V. vulnificus. Increased intracellular c-di-GMP levels induced the production of an EPS that was structurally different from the CPS. Biofilm formation and rugose colony development were also dramatically enhanced, and neither pathway was dependent on CPS production. However, in contrast to V. cholerae, motility and virulence were unaffected by increases in c-di-GMP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Sigma). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations when indicated: ampicillin (AP), 100 μg/ml; rifampin (RF), 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 160 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (CM), 6 μg/ml; isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 1 mM; l-arabinose (l-Ara), 0.02%. Plasmid DNA purifications were performed with a Sigma Plasmid Miniprep kit (Sigma). Plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by electroporation. E. coli S17.1 and S17.1λπ were used as donor strains for conjugation of the plasmids into V. vulnificus. Genomic DNA was extracted with the DNAZOL reagent (Invitrogen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was done at The Centre for Applied Genomics at The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| V. vulnificus | ||

| 27562 | Type strain; clinical isolate from Florida | Institut Pasteur |

| 27562-T | Naturally translucent variant of 27562 | This study |

| wzy::Tn10 | Acapsular mutant of 27562 with a Tn insertion in the wzy CPS polymerase | 58 |

| rmlC::Tn10 | Acapsular mutant of 27562 with a Tn insertion in the rmlC epimerase | 58 |

| Δwzc | Acapsular mutant of 27562 with a disruption of the wzc tyrosine autokinase required for CPS transport | This study |

| wzy::Tn10C | wzy::Tn10 complemented with the wt wzy gene | 58 |

| rmlC::Tn10C | rmlC::Tn10 complemented with the wt rmlC gene | 58 |

| ΔwzcC | Δwzc complemented with the wt wzc gene | This study |

| CMCP6 | Clinical isolate from Korea | 10 |

| YJ016 | Clinical isolate from Taiwan | 10 |

| 1003 | Clinical isolate from Louisiana | 24 |

| V. cholerae N16961 | Clinical strain from Bangladesh | Institut Pasteur |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 | Deficient in cellulose and biofilm production | 21 |

| E. coli | ||

| S17.1 | Donor strain for conjugation | 80 |

| S17.1λπ | Donor strain for conjugation | 80 |

Genomic library construction.

Genomic DNA from V. vulnificus strain ATCC 27562 was digested with Sau3AI and fractionated on a 0.7% low-melting-point agarose gel. Fragments of 4 to 6 kb were purified by gelase digestion (Epicenter Technologies) by following the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA fragments were ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs) into the BamHI site of cloning vector p222, a derivative of pUC19 that carries the RP4 origin of conjugative transfer in the HindIII site. Ligations were incubated overnight at 16°C and transformed into S17.1. Transformants were selected on LB-AP plates. Sixty-eight percent of the clones contained an insert with an average size of 3 kb. The average genome size of the two sequenced V. vulnificus strains is 5.2 Mb. Thus, 2,496 clones, representing approximately twofold genome coverage, were used for conjugation to V. vulnificus strain 27562.

Isolation of strain ATCC 27562-T.

V. vulnificus ATCC 25762 was streaked onto an LB-RF plate and grown overnight at 37°C. A single, isolated colony was inoculated into 5 ml of LB-RF and incubated with shaking at 37°C for 16 h, followed by static incubation at 25°C for 6 days. Bacteria were then streaked onto LB-RF plates to identify and isolate translucent colonies.

Construction and complementation of the Δwzc mutant strain.

Primers wzcFKO (5′-GGGGGGAATTCCGCATCGCTGGAAAGGTGA-3′) and wzcRKO (5′-GGGGGGAATTCGCAAGTCCGATAGGCC-3′) were used to amplify a 1,377-bp internal fragment of wzc from genomic DNA of V. vulnificus strain 27562 (the EcoRI site is underlined). The PCR product was cut with EcoRI and cloned into the same site of suicide plasmid pSW23 (13). The pSW23::Δwzc plasmid was transformed into E. coli S17.1λπ and then conjugated to strain 27562 to create Δwzc. Cointegrants were selected on LB-RF-CM plates. Proper plasmid cointegration was confirmed by PCR and phenotypic characterization of the expected translucent phenotype.

To complement the Δwzc mutant strain, the wzc gene was amplified from genomic DNA of V. vulnificus strain 27562 with primers wzcBspHI (5′-CCTCATGAACGAGACAATGACAACAC-3′) and wzcNcoI (5′-CCCCATGGTTACGCTTTATTACTCTCACCAT-3′) and the product was cut with BspHI and NcoI and cloned into the NcoI site of pBAD24T. The pBAD24T plasmid was created by inverse PCR with primers pTRC99a-3Not (5′-AAAAGCGGCCGCTTCTCCTTACGCATCTGTGC-3′) and pTRC99a-4Not (5′-AAAAGCGGCCGCAATACCGCATCAGGCGCTC-3′) with pBAD24 (26) as the template. The origin of conjugative transfer (oriT) from the RP4 plasmid was amplified with primers oriT1Not (5′-CTGCGGCCGCCTTTTCCGCTGCATAACCCTG-3′) and oriT2Not (5′-CTGCGGCCGCCGGCCAGCCTCGCAGAGC-3′). Both products were cut with NotI and ligated to create pBAD24T. Plasmids containing the insert in the correct orientation were identified, transformed into S17.1, and then conjugated to Δwzc. Transconjugants were selected on LB-RF-CM-AP plates. Expression of wzc was induced with l-Ara.

Sequential screening of the genomic library.

The library plasmids were first screened in the V. vulnificus wzy::Tn10 mutant (58) as follows. E. coli S17.1 donor and V. vulnificus recipient cultures were grown overnight in LB-AP and LB-RF, respectively. The next day, bacteria were diluted 100 times in fresh medium and grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.7. One milliliter of each was centrifuged and washed twice in LB medium. The pellets were combined in 100 μl of LB medium and conjugated overnight without antibiotic selection on LB medium plates. On the following day, cells were resuspended in 5 ml of LB medium. One milliliter of the resuspension was pelleted and resuspended in 100 μl of fresh LB medium, and transconjugants were selected on LB-RF-AP plates. Opaque clones were selected and grown in fresh LB-RF-AP. Plasmids were isolated from pooled cells and transformed into E. coli S17.1 donor cells. These cells were conjugated to the rlmC::Tn10 mutant (58), and opaque clones were selected as described above. Selected cells were pooled, and plasmid DNA was again isolated and transformed into E. coli S17.1 donor cells for a final round of selection following conjugation to the Δwzc mutant strain. The plasmid obtained after this final round of selection was sequenced.

Cloning of dcpA and VCA0956 into pBAD24T.

The dcpA gene was amplified with primers BspHI-1294Falt (5′-TCATGATTAGATATTCAACTCGTCC) and XbaI-1294R (5′-TCTAGATTAAGTCTCACTCATACCTGAC) from V. vulnificus strain 27562 genomic DNA. The VCA0956 gene was amplified with primers NcoI-VCA0956F (5′-AAGACCATGGGTGATGACAACTGAAGATTTCA) and XbaI-VCA0956R (5′-TTTTTCTAGATTAGAGCGGCATGACTCGATTGC) from V. cholerae strain N16961 genomic DNA. The PCR products were digested with the indicated enzymes (restriction sites are underlined) and cloned into the NcoI and XbaI sites of the conjugative expression vector pBAD24T. Correct clones were verified by restriction digestion and sequencing. Expression of dcpA and VCA0956 was induced with arabinose.

Complementation of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 was transformed with pBAD24T::VCA0956, pBAD24T::dcpA, or the vector alone. Cellulose production by each strain was assessed via calcofluor (Fluorescent Brightener 28; Sigma) binding as previously described (21). Briefly, transformants were streaked onto LB agar plates containing 200 μg/ml calcofluor and incubated overnight at 37°C. The plates were then incubated at room temperature for an additional 48 h. Cell fluorescence was monitored under UV light. Images were captured with a Nikon D70S digital camera.

Biofilms assays.

Biofilm assays were adapted from the original protocol of O'Toole and Kolter (60, 61). Clones identified from the sequential screen were picked, inoculated into culture tubes containing 3 ml of fresh LB-RF-AP, and grown overnight. Cultures were adjusted to 106 CFU ml−1 in fresh medium, and 150 μl was inoculated into 96-well microtiter plates (2 wells per strain). Microtiter plates were statically incubated for 24 h at 30°C. Following measurement of the planktonic cell density at OD600 with a BioTek PowerWave 340 microplate spectrophotometer, medium was carefully removed and the wells were stained with 150 μl of 0.1% crystal violet (CV) solution for 20 min. The stained wells were then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 130 mM NaCl, 5 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) and biofilms were resolubilized in 150 μl of isopropanol-acetone (4:1). The OD595 of each well was then measured. The ODCV/ODcells ratio was calculated to determine the relative level of biofilm formation.

Colony morphology assays.

For colony morphology assays, the protocol of Lim et al. (46) was followed. Strains were grown overnight in LB broth containing the appropriate antibiotics at 30°C with shaking. The next day, bacteria were diluted 200-fold in fresh medium and 2 μl was spotted onto LB agar plates containing the appropriate antibiotics. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days, and the colonies were photographed with a Kodak DX6400 digital camera.

Motility assays.

LB medium-Difco agar (0.3%) plates were prepared with appropriate antibiotics. Serial dilutions from overnight cultures were adjusted to 108 CFU/ml in fresh LB medium with appropriate antibiotics, and 1 μl was dropped onto the surface of each swarming plate. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the diameters of the swarming colonies were measured.

In vitro and in vivo segregation assays for plasmid p1270.

Strains of V. vulnificus containing p1270 were assayed to determine if the plasmid would segregate from the bacteria in the absence of antibiotic selection. Single colonies of strains carrying p1270 were grown to an OD600 of 1.0 in LB-AP. The cultures were diluted to 105 CFU/ml in 5 ml of LB medium without AP selection and grown at 37°C with shaking. Samples were plated at the beginning of the experiment and at 3-h time points thereafter, up to 24 h after inoculation. Samples were plated on LB medium to quantify the total number of bacteria and on LB-AP to quantify the number of plasmid-containing bacteria. Plasmid maintenance was calculated by dividing the number of plasmid-containing bacteria recovered by the total number of bacteria recovered. Experiments were done in triplicate.

In vivo segregation assays were performed as follows. Five-week-old female ICR mice (Charles River) housed under pathogen-free conditions were pretreated with an intraperitoneal injection of 250 μg of iron-dextran per g of body weight 60 min before inoculation with the bacterial strains. Groups of five mice were injected subcutaneously in the lower flank with 105 bacteria suspended in 0.1 ml of PBS (81). Mice showed clear signs of septicemia between 10 and 12 h postinoculation and were euthanized. The subcutaneous skin lesions were aseptically removed, homogenized in 5 ml PBS, diluted, and plated on LB and LB-AP plates. Plasmid maintenance was calculated as described above. Experiments were done in triplicate.

Antiserum production, slide agglutination assays, and 50% lethal dose (LD50) determinations.

The production of antisera to formalin-killed whole cells of V. vulnificus strain 27562, slide agglutination assays, and LD50 determinations were performed as previously described (58).

HMWP extraction and detection.

High-molecular-weight polysaccharide (HMWP) was extracted as previously described (58) and detected by immunostaining with antiserum against formalin-killed whole cells of V. vulnificus 27562 (58) or Alcian blue staining of acidic polysaccharides as described by Pelkonen et al. (65, 66).

Bioinformatic analyses.

Homology searches were conducted by BLAST (2) analysis, and protein parameters and domain predictions were determined with ProtParam (22) and the PROSITE research tool from the Expert Protein analysis system (32).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of dcpA has been deposited at GenBank under accession number EU683890.

RESULTS

Identification of DcpA, a DGC.

We previously used transposon mutagenesis to identify two genes, wzy and rmlC, that participate in the biosynthesis of the group IV CPS in V. vulnificus strain 27562 (58). The wzy gene codes for a polymerase that is required for CPS polymerization, and rmlC codes for an epimerase that participates in the biosynthesis of rhamnose, a component of the CPS of V. vulnificus strain 27562 (25). We also constructed a third mutant strain, the Δwzc mutant, which contained a disruption in the wzc gene that is required for the transport of group I and IV CPS to the bacterial surface (15, 64, 94). The wzy::Tn10, rmlC::Tn10, and Δwzc mutants are acapsular and avirulent and appear translucent on solid medium. Complementation experiments demonstrated that the wt wzy, rmlC, and wzc genes restored opacity to the corresponding knockouts, but they were incapable of complementing the translucent phenotype of the other mutants.

Increased biofilm formation often correlates with increased EPS production in other bacterial species. Increased EPS production can manifest itself as an opaque phenotype in a normally translucent background. We took advantage of the translucent phenotype of the wzy::Tn10, rmlC::Tn10, and Δwzc mutants to visually investigate if V. vulnificus produced an EPS in addition to CPS. A genomic library from wt V. vulnificus strain 27562 was screened in the wzy::Tn10 translucent background to isolate clones with an opaque phenotype. This step eliminated the selection of plasmids containing the intact rmlC and wzc genes. Plasmid DNA was extracted from opaque clones and screened in the rlmC::Tn10 background in a second round, and clones that had an opaque phenotype were selected. This step eliminated the selection of plasmids containing the intact wzy and wzc genes. Plasmid DNA was extracted from these opaque clones and screened in the Δwzc background in a final “filter” round for clones that had an opaque phenotype. This step precluded the selection of plasmids containing the intact wzy and rmlC genes. Since the rmlC, wzy, and wzc genes are required for group I and IV CPS biosynthesis and transport (89), opaque clones identified at the end of the screen were anticipated somehow either to produce wt CPS in a wzy-, rmlC-, and wzc-independent manner or to produce an EPS that was different from CPS. We obtained several opaque clones from our screen. The plasmid from one of these clones (p1270) contained a 1,859-bp insert with two partial open reading frames and one complete open reading frame, orf1270b; orf1270b was 1,140 bp and coded for a 379-amino-acid protein. To demonstrate that orf1270b alone was responsible for inducing the opaque phenotype, orf1270b was cloned into expression vector pBAD24T and transferred to the translucent wzy::Tn10, rmlC::Tn10, and wzc mutants. All three strains reverted to an opaque phenotype. A BlastP search and PROSITE analysis indicated that Orf1270b harbored an I site and GAF and GGDEF domains that are typically found as part of modular DGC enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of the signaling molecule c-di-GMP (Fig. 1) (19, 35, 79). The PSLpred (4), CELLO (98), and LOCtree (57) algorithms were used to predict the subcellular location of the protein. In each instance, Orf1270b was predicted to be a cytoplasmic protein with a confidence value of greater than 90%. The presence of the I site and the GGDEF and GAF domains in Orf1270b prompted us to test Orf1270b for DGC activity. DGC activity was assayed by complementation of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344, which fails to produce cellulose or form biofilms. Cellulose production and biofilm formation can be restored in strain SL1344 if the intracellular c-di-GMP levels are increased, and this strain has been previously used to demonstrate the DCG activity of several GGDEF domain-containing proteins (21). VCA0956, a cytoplasmic DGC from V. cholerae (84), was cloned into pBAD24T and served as a positive control. The empty plasmid, pBAD24T::orf1270, and pBAD24T::VCA0956 were transformed into S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344. Induction of cellulose production was monitored by bacterial fluorescence on calcofluor agar plates. While pBAD24T alone had no effect on cellulose production (Fig. 2A), the expression of VCA0956 and orf1270 restored the cellulose production defect of strain SL1344 (Fig. 2B and C, respectively). The ability of Orf1270b to stimulate cellulose production in SL1344 similarly to VCA0956 and its homology to DGC supported a DGC activity for the protein. The orf1270b gene was designated dcpA, for diguanylate cyclase protein A.

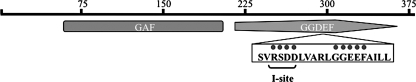

FIG. 1.

Domain architecture of DcpA. DcpA is a two-domain protein. The GAF (amino acids 66 to 200) and GGDEF (amino acids 215 to 370) domains are delimited by the gray rectangle and arrow, respectively. The corresponding amino acids of the GGEEF sequence and I site in DcpA are marked by dots below the GGDEF motif. The black bar represents the total length of the protein, at 379 amino acids.

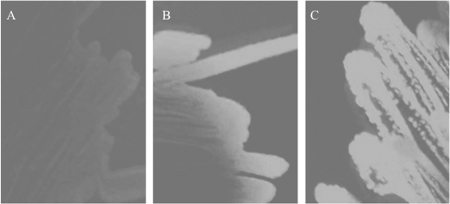

FIG. 2.

Restoration of cellulose production in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 by DcpA. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 is deficient in cellulose production, and strain SL1344 carrying the empty pBAD24T vector does not fluoresce on calcofluor agar plates (A). The VCA0956 gene from V. cholerae N16961, previously shown to encode a DGC, was cloned into pBAD24T and transformed into strain SL1344 (B). The dcpA gene was also cloned into pBAD24T and transformed into strain SL1344 (C). Fluorescence is clearly visible in panels B and C.

c-di-GMP regulates the production of an EPS.

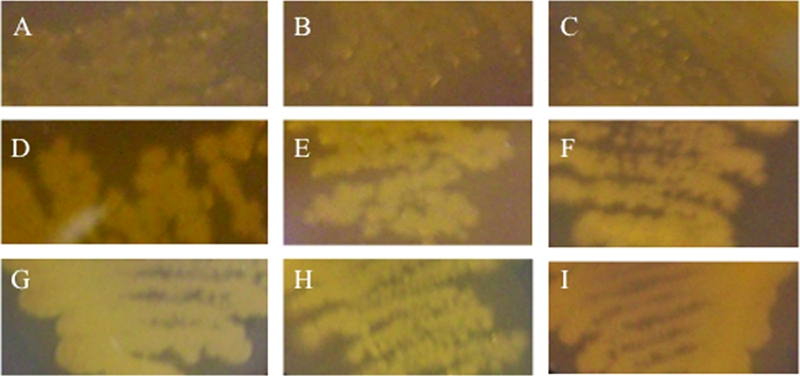

c-di-GMP is known to regulate many distinct cellular processes in bacteria, and VCA0956 has also been shown to induce EPS production (3, 47, 84). We elected to use DcpA and VCA0956 to examine the effect of increased levels of c-di-GMP on polysaccharide production in V. vulnificus. The pBAD24T::orf1270b and pBAD24T::VCA0956 plasmids were conjugated to the translucent wzy::Tn10, rmlC::Tn10, and Δwzc mutants (Fig. 3A to C). Strains carrying either pBAD24T::orf1270b (Fig. 3D to F) or pBAD24T::VCA0956 (Fig. 3G to I) had an opaque phenotype on solid medium and failed to agglutinate with antisera to wt cells. This suggested that an EPS, rather than wt CPS, was being produced and that increased levels of c-di-GMP induced its synthesis.

FIG. 3.

Effects of DcpA and VCA0956 on the translucent phenotype of V. vulnificus CPS mutants. The CPS biosynthesis mutants wzy::Tn10 (A) and rmlC::Tn10 (B) and the CPS transport mutant Δwzc (C), which carried the pBAD24T plasmid, appear translucent on solid medium. The same strains carrying pBAD24T::dcpA (D to F) or pBAD24T::VCA0956 (G to I) appear opaque under inducing conditions.

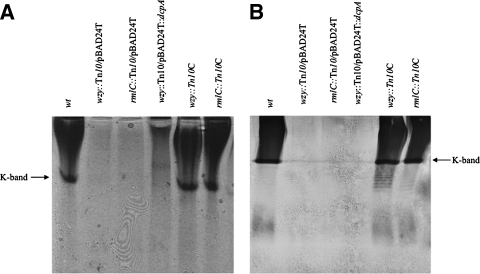

HMWP was extracted from the wt, wzy::Tn10, rlmC::Tn10, and wzy::Tn10/pBAD24T::dcpA strains and detected by Alcian blue staining. The high-molecular-weight CPS and K band previously observed in strain 27562 (58) were detected in wt cells (Fig. 4A). No such material was observed in preparations from wzy::Tn10 or rmlC::Tn10. Complementation of both the wzy::Tn10 and rmlC::Tn10 mutants with the corresponding wt genes (designated wzy::Tn10C and rmlC::Tn10C, respectively) restored the production of the CPS and the K band and opacity to these translucent mutants. Interestingly, a high-molecular-weight EPS that appeared to be different from the CPS produced by the wt strain was detected in wzy::Tn10/pBAD24T::dcpA by Alcian blue staining, and the K band was absent. Furthermore, the EPS was not visible in the wzy::Tn10 or rmlC::Tn10 mutant that lacked pBAD24T::dcpA. This suggested that this EPS was expressed at a low level or not at all in V. vulnificus under the conditions used here and that increased levels of c-di-GMP induced the production of the EPS.

FIG. 4.

Alcian blue staining and immunoblotting of V. vulnificus HMWP. HMWP extracted from the indicated strains was separated on a nondenaturing 40% polyacrylamide gel and detected by Alcian blue staining (A) or by denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and detected by immunoblotting with antiserum to formalin-killed whole cells of strain 27562 (B). The K band described previously (58) is indicated.

To verify that the observed EPS was structurally different from the CPS, HMWP from the strains above was also analyzed by immunoblotting with antisera to formalin-killed whole cells of strain 27562 (Fig. 4B). Immunoblotting results paralleled those obtained by Alcian blue detection, with one exception. Again, CPS and the K band were readily detected in wt, wzy::Tn10C, and rmlC::Tn10C cells while no such material was observed in preparations from the wzy::Tn10 or rmlC::Tn10 strain. Of note, while wzy::Tn10/pBAD24T::dcpA appeared opaque on solid medium and an EPS was detected by Alcian blue staining, no such material was detectable in this strain by immunoblotting. These results were confirmed by slide agglutination assays. Antisera clearly agglutinated the wt, wzy::Tn10C, and rmlC::Tn10C strains, but no agglutination was observed for wzy::Tn10, rmlC::Tn10, or wzy::Tn10 carrying pBAD24T::dcpA (data not shown). These results suggested that the observed c-di-GMP-regulated EPS was structurally different from the CPS.

c-di-GMP regulates biofilm formation in V. vulnificus.

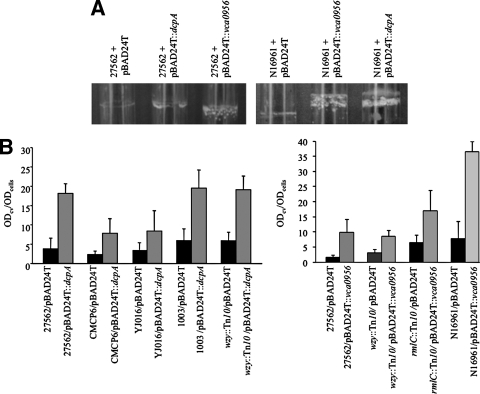

c-di-GMP has been shown to induce biofilm formation in V. cholerae (46, 84). This prompted us to use DcpA and VCA095 to examine the effect of elevated c-di-GMP levels on biofilm formation in V. vulnificus and V. cholerae. V. vulnificus 27562 and V. cholerae N16961 carrying the empty vector, pBAD24T::dcpA, or pBAD24T::VCA0956 were visually assayed for biofilm formation in culture tubes under inducing conditions. Overexpression of either dcpA or VCA0956 resulted in an increase in biofilm formation in both backgrounds (Fig. 5A). We then transferred pBAD24T::dcpA to strains 27562, CMCP6, YJ016, and 1003 and determined the levels of biofilm formation under inducing conditions by quantitative CV staining (Fig. 5B). Although there was no statistically significant difference between the amounts of biofilm formed by the parental strains tested here, the total amount of biofilm produced by the parental strains was consistently highest for strain 1003, followed by strains 27562, YJ016, and CMCP6. The total amount of biofilm produced by the parental strains harboring pBAD24T::dcpA was again the greatest for strain 1003, followed by strains 27562, YJ016, and CMCP6. However, the effect of pBAD24T::dcpA on biofilm formation was the most dramatic in strain 27562, where a 4.8-fold increase in biofilm formation was observed, followed by 3.4-, 3.3-, and 2.4-fold increases in strains CMCP6, 1003, and YJ016, respectively. These results suggested that c-di-GMP enhanced biofilm formation in V. vulnificus; however, the total amount of biofilm produced by various V. vulnificus isolates was strain dependent. Finally, there was no statistically significant difference between the amounts of biofilm formed by the wt and wzy::Tn10 mutant strains. This supported a previous report in which the CPS was found to inhibit biofilm formation in V. vulnificus (36). To confirm that the CPS was not required for biofilm formation as measured by CV staining, pBAD24T::dcpA was transferred to the wzy::Tn10 mutant strain and biofilm formation was quantified. The expression of dcpA increased biofilm formation to similar degrees in the wt and wzy::Tn10 mutant strains. Similar relative increases in biofilm formation were observed when VCA0956 was expressed by the wt, wzy::Tn10, and rmlC::Tn10 strains. These results verified that biofilm formation is regulated by c-di-GMP in V. vulnificus and that it was not dependent on the production of a CPS under the conditions tested here.

FIG. 5.

c-di-GMP induces biofilm formation by V. vulnificus and V. cholerae. (A) Biofilm formation in culture tubes by V. vulnificus and V. cholerae expressing dcpA or VCA0956. Cells carrying the empty pBAD24T vector or pBAD24T containing dcpA or VCA0956 were grown overnight under inducing conditions. (B) Quantification of biofilm formation by CV staining. The black bars indicate the level of biofilm formation for the various parental strains carrying the empty pBAD24T vector, while the adjacent gray bars indicated the level of biofilm formation in the same strain carrying pBAD24T that contains the indicated DGC. Microtiter plates were stained with CV 24 h after inoculation and static growth at 30°C. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations.

c-di-GMP regulates rugose colony formation.

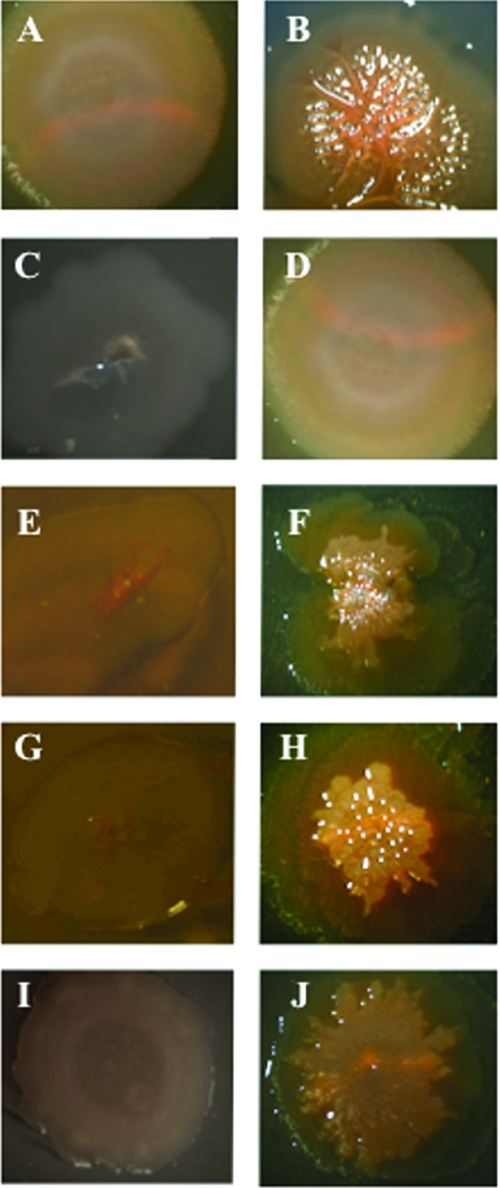

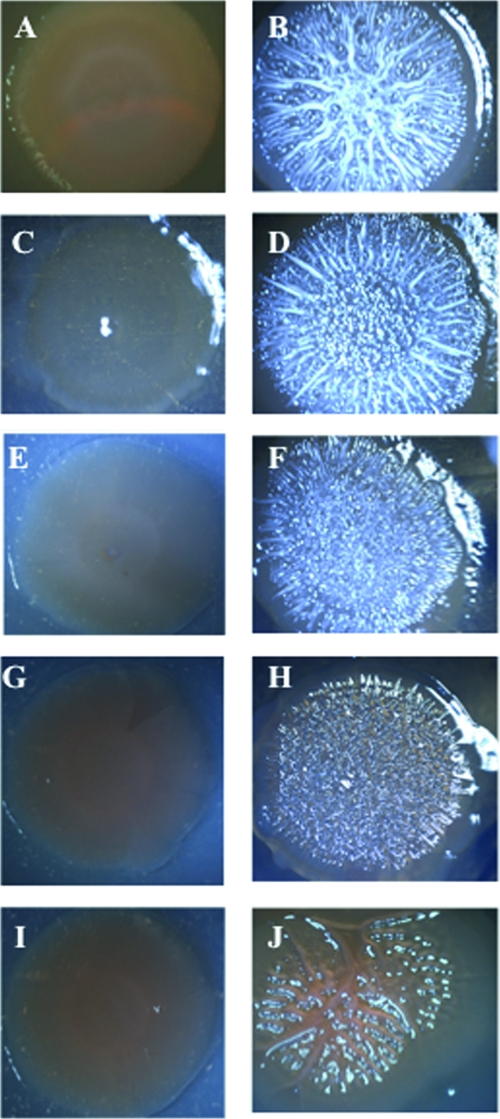

To ascertain if c-di-GMP also stimulated rugose colony formation in V. vulnificus, we performed comparative colony morphology analysis on different isogenic mutants of strain 27562 that carried pBAD24T::dcpA. Parental cells carrying the empty vector had a flat, opaque, featureless appearance (Fig. 6A). The presence of pBAD24T::dcpA in the wt background resulted in the formation of wrinkled, raised, opaque colonies that typify the rugose phenotype (Fig. 6B). To determine if rugose colony development, like biofilm formation, was independent of CPS production, we elected to examined the effect of pBAD24T::dcpA on colony morphology in the absence of CPS production with three acapsular mutants, wzy::Tn10, rmlC::Tn10, and 27562-T. 27562-T is a spontaneous translucent variant of strain 27562. The three acapsular mutants appear translucent on solid medium (Fig. 6C, E, G, and I). Expression of the wt wzy gene in the wzy::Tn10 mutant restored the smooth, opaque appearance of the parental strain (Fig. 6D). The presence of pBAD24T::dcpA in wzy::Tn10 resulted in a wrinkled, opaque colony morphology (Fig. 6F) that was similar to that of the wt strain containing pBAD24T::dcpA. The pBAD24T::dcpA plasmid also induced rugose colony development in the rmlC::Tn10 and 27562-T translucent backgrounds to yield wrinkled, opaque colonies (Fig. 6H and J). Similar results were obtained when VCA0956 was expressed in the V. vulnificus wt, wzy::Tn10, and rmlC::Tn10 strains (Fig. 7A to F) or when dcpA was expressed in V. cholerae N16961 (Fig. 7G to J). These results suggested that c-di-GMP stimulated rugose colony formation and this phenotype was not dependent upon the presence of CPS.

FIG. 6.

Colony morphologies of V. vulnificus 27562 variants expressing dcpA. All colonies were grown on LB agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics for 72 h at 30°C. Panels: A, wt strain carrying pBAD24T; B, wt strain carrying pBAD24T::dcpA; C, wzy::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T; D, wzy::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T::wzy; E, wzy::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T; F, wzy::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T::dcpA; G, rmlC::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T; H, rmlC::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T::dcpA; I, strain 27562-T carrying pBAD24T; J, strain 27562-T carrying pBAD24T::dcpA. The colony images are representative of three biological replicates. Images were captured with an AxioCam MRc5 (Zeiss) digital camera attached to a dissecting microscope.

FIG. 7.

Colony morphologies of V. vulnificus 27562 variants and V. cholerae N16961 expressing VCA0956 or dcpA. All colonies were grown on LB agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics for 72 h at 30°C. Panels: A, strain 27562 carrying pBAD24T; B, strain 27562 carrying pBAD24T::VCA0956; C, wzy::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T; D, wzy::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T::VCA0956; E, rmlC::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T; F, rmlC::Tn10 mutant strain carrying pBAD24T::VCA0956; G, strain N16961 carrying pBAD24T; H, strain N16961 carrying pBAD24T::VCA0956; I, strain N16961 carrying pBAD24T; J, strain N16961 carrying pBAD24T::dcpA. The colony images are representative of three biological replicates. Images were captured with an AxioCam MRc5 (Zeiss) digital camera attached to a dissecting microscope.

Increased c-di-GMP levels do not affect the motility of V. vulnificus.

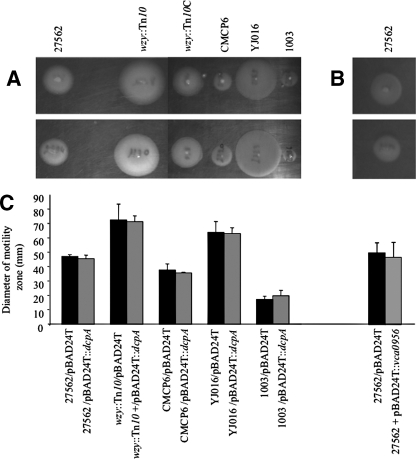

c-di-GMP has been reported to inhibit motility in V. cholerae (46). To test if increased production of c-di-GMP affected the motility behavior of V. vulnificus, we measured the motility zones of wt and mutants strains carrying either pBAD24T::dcpA or the empty vector on LB soft-agar plates. A representative assay is shown in Fig. 8A. The different parental strains (top row) exhibited various degrees of relative motility, and there was no definitive correlation between motility and biofilm-forming capacity. For example, while strain YJ016 exhibited nearly fourfold greater motility than strain 1003, there was no statistically significant difference between their biofilm-forming capacities (Fig. 5). The motility profile of each background strain remained essentially unchanged in the presence of pBAD24T::dcpA (Fig. 8A, bottom row, and C). To verify this, VCA0956 was also expressed in the wt strain (Fig. 8B and C). Again, bacterial motility was unaffected. Thus, in contrast to V. cholerae, increased levels of c-di-GMP did not affect the motility of V. vulnificus. However, the motility of the wzy::Tn10 mutant strain was 1.5-fold greater than that of the wt strain, while the motility of the wzy::Tn10C strain was equal to that of the wt strain. These results suggested that CPS production inhibited motility.

FIG. 8.

Motility phenotypes of various V. vulnificus strains expressing dcpA or VCA0956. (A) Overnight cultures of the indicated strains carrying pBAD24T (top row) or pBAD24T::dcpA (bottom row) were adjusted to 108 CFU/ml, and 1-μl aliquots were inoculated onto motility plates. Images were taken with a Bio-Rad Gel Doc 2000 imaging system following overnight incubation at 37°C. (B) Same as panel A but with strain 27562 carrying either pBAD24T (top) or pBAD24T::VCA0956 (bottom). (C) Quantitative measurement of the mobility of the same strains. The diameter of the net migration is shown. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Increased c-di-GMP levels do not affect virulence in V. vulnificus.

Increased c-di-GMP levels negatively regulate virulence gene expression in V. cholerae (47, 85). To ascertain if increased c-di-GMP levels affected the virulence of V. vulnificus, the virulence of the wzy::Tn10 and wt strains carrying either pUC19oriT or p1270 was tested in vivo. We opted to use p1270 since the effect of this plasmid on EPS production, biofilm formation, rugosity, and motility in V. vulnificus was the same as that of pBAD24T::dcpA but the expression of dcpA did not require induction (not shown). The CMCP6 and YJ016 strains were used as controls, and their respective LD50s of 6.8 × 103 and <101 are in agreement with those reported previously (16, 40). The LD50 of strain 27562 was 2.4 × 104. This increased to 4.2 × 107 for the acapsular wzy::Tn10 mutant. Whereas virulence was restored to the wzy::Tn10 mutant following complementation with the wt wzy gene (LD50 = 1.4 × 104), the presence of p1270 did not significantly alter its attenuated phenotype (LD50 = 2.6 × 108) or the virulence of the wt strain (LD50 = 3.2 × 104). Hence, the c-di-GMP-regulated EPS could not compensate for the loss of CPS production that is required for V. vulnificus virulence in vivo. To verify that the lack of effect was not due to plasmid loss during the course of infection, the maintenance of p1270 in the wt strain in the absence of antibiotic selection was monitored in vitro over a 12-h time course (the length of the in vivo experiment) and following a 12-h course of infection in mice. Strains were grown with shaking at 37°C in LB broth without antibiotic selection, and samples were plated every 3 h onto two media. To quantify the number of plasmid-containing bacteria, dilutions were spread onto plates containing AP. To quantify the total number of bacteria in the culture, an equal aliquot was spread onto plain LB medium plates. The plasmid was maintained in the wt strain in the absence of antibiotic selection, as shown by the number of CFU per milliliter being not significantly different from the number of CFU per milliliter obtained following plating on selective medium (95% ± 2%). Similar results were obtained in vivo (93% ± 5%). Since there was no significant decrease in the number of plasmid-containing bacteria relative to the total number of bacteria after 12 h of growth in vitro or in vivo, this suggested that the plasmid was efficiently segregating to the bacterial progeny and DcpA was being expressed in most of the cells during the course of the experiment. Thus, increased levels of c-di-GMP appeared to have little effect on the virulence of V. vulnificus.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies of V. vulnificus have demonstrated that while the CPS is essential for virulence (48, 97), it is not required for biofilm formation (36) or rugose colony development (24). We sought to identify factors that participate in these developmental pathways. The sequential screening strategy we used led to our identification of DcpA, a member of the DGC protein family that synthesizes c-di-GMP. Although we did not directly demonstrate that the expression of dcpA caused an increase in the intracellular c-di-GMP concentration, bioinformatic analysis indicated that DcpA had a domain structure that was typical of cytoplasmic DGC and its phenotypic effect on EPS production, biofilm formation, and rugosity in V. vulnificus, and cellulose production in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 was similar to that of the well-characterized V. cholerae cytoplasmic DGC VCA0956 (3, 46, 79, 84). Furthermore, like VCA0956, DcpA enhanced biofilm formation and rugosity in V. cholerae. These observations supported the DGC activity proposed for DcpA. The clone containing the dcpA gene was only one of the clones that we recovered from our screen. Other cytoplasmic DGC are likely to be identified among the remaining clones, as they would presumably have a phenotypic effect similar to that of DcpA.

We used DcpA and VCA0956 to examine the effects of increased c-di-GMP levels on the physiology of V. vulnificus. We showed that increasing the intracellular c-di-GMP levels induced the expression of an EPS that is distinct from the wt CPS. A specific environmental cue is likely required to induce EPS production, as the EPS was not observed in strains unless dcpA was present in multiple copies or overexpressed. Increased DcpA activity likely bypassed the required input. This, in turn, led to increased levels of c-di-GMP and triggered the synthesis of the EPS. Our genomic analyses of the YJ016 and CMCP6 genomes indicated that they both contained at least four putative polysaccharide biosynthesis regions, in addition to their CPS loci, that are greater than 3 kb in size. One of these likely encodes the enzymes that synthesize the c-di-GMP-regulated EPS.

Increased c-di-GMP levels also enhanced biofilm formation and rugosity in V. vulnificus. The linkage of EPS production, biofilm formation, and rugose colony development is well documented. Biofilms provide a stable protective milieu for growth and a means to facilitate transmission by acting as a source for the dissemination of large numbers of microorganisms (27, 45, 88). Biofilms are sheathed in a hydrated matrix of EPS that are produced by the resident microorganisms. EPS production increases biofilm formation and bacterial survival under specific stress conditions (49, 52, 82, 87, 95). V. vulnificus associates asymptomatically with filter feeders, such as oysters (28, 90), and it has been shown to exist as an interconnected network of cells in a mucous layer on the skin of eels that survive infection (50). This is believed to be a survival mechanism for the bacteria between infections, allowing them to endure low salinity and the presence of antimicrobials in waters posttreatment. It is tempting to speculate that the c-di-GMP-regulated EPS we observed is one of the factors that participate in biofilm formation and rugose colony development, and we are currently investigating this possibility.

Although increased c-di-GMP levels resulted in enhanced biofilm formation in V. vulnificus, the degree of induction and the final level of biofilm formed were strain specific. This was in agreement with the results of a previous report showing that biofilm development varied considerably among V. vulnificus isolates (53). The differential biofilm-forming capacities of V. vulnificus strains could be due to differences in the expression or activity of downstream effector proteins such as the proteins that bind the c-di-GMP and transduce the signal to systems that regulate the expression of adhesion factors like polysaccharides (12, 18, 33, 95, 96), pili (60, 62, 71), or adhesion proteins (54, 55).

In general, increases in c-di-GMP concentrations enhance the expression of adhesion factors, biofilm formation, and rugosity while repressing motility and virulence gene expression (3, 23, 42, 47, 68, 84, 85). Our studies indicated that while increased c-di-GMP levels impacted biofilm formation and rugosity in V. vulnificus, motility and virulence were unaffected. There are several possible explanations for this. It is conceivable that the effect of c-di-GMP on target pathways in V. vulnificus is dependent upon the precise cytoplasmic concentration of c-di-GMP. Alternatively, different DGC may have different subcellular locations, and the local concentration of c-di-GMP, rather than its total cytoplasmic concentration, is critical for the regulation of specific developmental pathways. Indirect evidence for the localization of c-di-GMP activity came from the observation that the DGC PleD in Caulobacter crescentus is sequestered at the cell pole (63). However, it remains a formal possibility that the motility and virulence pathways of V. vulnificus are not subject to c-di-GMP regulation.

Large-scale genome sequencing has unearthed something unexpected regarding c-di-GMP signaling. The number of GGDEF and EAL domain proteins encoded in bacterial genomes is highly variable. For example, no GGDEF or EAL domain proteins are found in the genome of Helicobacter pylori; E. coli has an intermediate number (from 3 to 23 GGDEF and EAL domain proteins), and V. vulnificus encodes more than 80 of these proteins (35). These observations raise some interesting questions. What triggers these signaling pathways, and what are the receptor and effecter mechanisms involved? How is the c-di-GMP signaling network connected to other signaling networks (e.g., quorum sensing) in the bacteria? Are there other enzymes besides GGDEF and EAL/HYP proteins that can synthesize and degrade c-di-GMP? Does the variability in the number of GGDEF and EAL proteins correlate with the range of environmental stimuli sensed by, and cellular functions affected in, different bacteria? How do bacteria with a large number of these signaling components minimize cross talk to control the specificity and robustness of c-di-GMP signaling and achieve a single desired response? The phenotypic effects of increased c-di-GMP levels on V. vulnificus are consistent with the hypothesis that c-di-GMP signaling controls these developmental pathways in a wide range of bacteria, and the large number of c-di GMP-related proteins suggests that this signaling molecule plays an important role in V. vulnificus. However, the study of the physiological impact of c-di-GMP signaling on V. vulnificus physiology is still in its infancy. This is the first study to demonstrate that c-di-GMP regulates biofilm formation and rugose colony development in V. vulnificus, two important physiological responses that likely participate in the survival and propagation of the bacterium. The study of c-di-GMP signaling in V. vulnificus should lead to a greater understanding of how this bacterium regulates the biosynthesis of its adhesion arsenal in response to environmental cues and may provide insight into approaches to decrease the Vibrio load in filter feeders to control the occurrence of invasive disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and a Premier's Research Excellence Award (PREA) to D.A.R.-M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, A., M. H. Rashid, and D. K. Karaolis. 2002. High-frequency rugose exopolysaccharide production by Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5773-5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyhan, S., A. D. Tischler, A. Camilli, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J. Bacteriol. 188:3600-3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhasin, M., A. Garg, and G. P. Raghava. 2005. PSLpred: prediction of subcellular localization of bacterial proteins. Bioinformatics 21:2522-2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisharat, N., V. Agmon, R. Finkelstein, R. Raz, G. Ben-Dror, L. Lerner, S. Soboh, R. Colodner, D. N. Cameron, D. L. Wykstra, D. L. Swerdlow, and J. J. Farmer III. 1999. Clinical, epidemiological, and microbiological features of Vibrio vulnificus biogroup 3 causing outbreaks of wound infection and bacteraemia in Israel. Lancet 354:1421-1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouillette, E., M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, D. K. Karaolis, and F. Malouin. 2005. 3′,5′-Cyclic diguanylic acid reduces the virulence of biofilm-forming Staphylococcus aureus strains in a mouse model of mastitis infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3109-3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camilli, A., and B. L. Bassler. 2006. Bacterial small-molecule signaling pathways. Science 311:1113-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1996. From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vibrio vulnificus infections associated with eating raw oysters—Los Angeles, 1996. JAMA 276:937-938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charbonneau, H., R. K. Prusti, H. LeTrong, W. K. Sonnenburg, P. J. Mullaney, K. A. Walsh, and J. A. Beavo. 1990. Identification of a noncatalytic cGMP-binding domain conserved in both the cGMP-stimulated and photoreceptor cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:288-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatzidaki-Livanis, M., M. K. Jones, and A. C. Wright. 2006. Genetic variation in the Vibrio vulnificus group 1 capsular polysaccharide operon. J. Bacteriol. 188:1987-1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christen, M., B. Christen, M. G. Allan, M. Folcher, P. Jeno, S. Grzesiek, and U. Jenal. 2007. DgrA is a member of a new family of cyclic diguanosine monophosphate receptors and controls flagellar motor function in Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:4112-4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croxatto, A., J. Lauritz, C. Chen, and D. L. Milton. 2007. Vibrio anguillarum colonization of rainbow trout integument requires a DNA locus involved in exopolysaccharide transport and biosynthesis. Environ. Microbiol. 9:370-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demarre, G., A. M. Guerout, C. Matsumoto-Mashimo, D. A. Rowe-Magnus, P. Marliere, and D. Mazel. 2005. A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPα) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res. Microbiol. 156:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dow, J. M., Y. Fouhy, J. F. Lucey, and R. P. Ryan. 2006. The HD-GYP domain, cyclic di-GMP signaling, and bacterial virulence to plants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 19:1378-1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drummelsmith, J., and C. Whitfield. 1999. Gene products required for surface expression of the capsular form of the group 1 K antigen in Escherichia coli (O9a:K30). Mol. Microbiol. 31:1321-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan, J. J., C. P. Shao, Y. C. Ho, C. K. Yu, and L. I. Hor. 2001. Isolation and characterization of a Vibrio vulnificus mutant deficient in both extracellular metalloprotease and cytolysin. Infect. Immun. 69:5943-5948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fouhy, Y., J. F. Lucey, R. P. Ryan, and J. M. Dow. 2006. Cell-cell signaling, cyclic di-GMP turnover and regulation of virulence in Xanthomonas campestris. Res. Microbiol. 157:899-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman, L., and R. Kolter. 2004. Two genetic loci produce distinct carbohydrate-rich structural components of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. J. Bacteriol. 186:4457-4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galperin, M. Y. 2004. Bacterial signal transduction network in a genomic perspective. Environ. Microbiol. 6:552-567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galperin, M. Y., A. N. Nikolskaya, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García, B., C. Latasa, C. Solano, F. G.-D. Portillo, C. Gamazo, and I. Lasa. 2004. Role of the GGDEF protein family in Salmonella cellulose biosynthesis and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 54:264-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gasteiger, E., C. Hoogland, A. Gattiker, S. Duvaud, M. R. Wilkins, R. D. Appel, and A. Bairoch. 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server, p. 571-607. In J. M. Walker (ed.), The proteomics protocols handbook. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

- 23.Goodman, A. L., B. Kulasekara, A. Rietsch, D. Boyd, R. S. Smith, and S. Lory. 2004. A signaling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev. Cell 7:745-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grau, B. L., M. C. Henk, and G. S. Pettis. 2005. High-frequency phase variation of Vibrio vulnificus 1003: isolation and characterization of a rugose phenotypic variant. J. Bacteriol. 187:2519-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunawardena, S., G. P. Reddy, Y. Wang, V. S. Kolli, R. Orlando, J. G. Morris, and C. A. Bush. 1998. Structure of a muramic acid containing capsular polysaccharide from the pathogenic strain of Vibrio vulnificus ATCC 27562. Carbohydr. Res. 309:65-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzman, L.-M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall-Stoodley, L., and P. Stoodley. 2005. Biofilm formation and dispersal and the transmission of human pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 13:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harwood, V. J., J. P. Gandhi, and A. C. Wright. 2004. Methods for isolation and confirmation of Vibrio vulnificus from oysters and environmental sources: a review. J. Microbiol. Methods 59:301-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilton, T., T. Rosche, B. Froelich, B. Smith, and J. Oliver. 2006. Capsular polysaccharide phase variation in Vibrio vulnificus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6986-6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoch, J. A. 2000. Two-component and phosphorelay signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:165-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang, B., C. B. Whitchurch, and J. S. Mattick. 2003. FimX, a multidomain protein connecting environmental signals to twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185:7068-7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hulo, N., A. Bairoch, V. Bulliard, L. Cerutti, E. De Castro, P. S. Langendijk-Genevaux, M. Pagni, and C. J. A. Sigrist. 2006. The PROSITE database. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:D227-D230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson, K. D., M. Starkey, S. Kremer, M. R. Parsek, and D. J. Wozniak. 2004. Identification of psl, a locus encoding a potential exopolysaccharide that is essential for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 186:4466-4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jenal, U. 2004. Cyclic di-guanosine-monophosphate comes of age: a novel secondary messenger involved in modulating cell surface structures in bacteria? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenal, U., and J. Malone. 2006. Mechanisms of cyclic-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40:385-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joseph, L. A., and A. C. Wright. 2004. Expression of Vibrio vulnificus capsular polysaccharide inhibits biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 186:889-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim, H. S., M. A. Lee, S. J. Chun, S. J. Park, and K. H. Lee. 2007. Role of NtrC in biofilm formation via controlling expression of the gene encoding an ADP-glycero-manno-heptose-6-epimerase in the pathogenic bacterium, Vibrio vulnificus. Mol. Microbiol. 63:559-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim, Y. K., and L. L. McCarter. 2007. ScrG, a GGDEF-EAL protein, participates in regulating swarming and sticking in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 189:4094-4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim, Y. R., S. Y. Kim, C. M. Kim, S. E. Lee, and J. H. Rhee. 2005. Essential role of an adenylate cyclase in regulating Vibrio vulnificus virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 243:497-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim, Y. R., S. E. Lee, C. M. Kim, S. Y. Kim, E. K. Shin, D. H. Shin, S. S. Chung, H. E. Choy, A. Progulske-Fox, J. D. Hillman, M. Handfield, and J. H. Rhee. 2003. Characterization and pathogenic significance of Vibrio vulnificus antigens preferentially expressed in septicemic patients. Infect. Immun. 71:5461-5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenig, K. L., J. Mueller, and T. Rose. 1991. Vibrio vulnificus. Hazard on the half shell. West. J. Med. 155:400-403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulasakara, H., V. Lee, A. Brencic, N. Liberati, J. Urbach, S. Miyata, D. G. Lee, A. N. Neely, M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, F. M. Ausubel, and S. Lory. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:2839-2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumar, A. S., K. Mody, and B. Jha. 2007. Bacterial exopolysaccharides—a perception. J. Basic Microbiol. 47:103-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee, V. T., J. M. Matewish, J. L. Kessler, M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, and S. Lory. 2007. A cyclic-di-GMP receptor required for bacterial exopolysaccharide production. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1474-1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leriche, V., R. Briandet, and B. Carpentier. 2003. Ecology of mixed biofilms subjected daily to a chlorinated alkaline solution: spatial distribution of bacterial species suggests a protective effect of one species to another. Environ. Microbiol. 5:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim, B., S. Beyhan, J. Meir, and F. H. Yildiz. 2006. Cyclic-diGMP signal transduction systems in Vibrio cholerae: modulation of rugosity and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 60:331-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim, B., S. Beyhan, and F. H. Yildiz. 2007. Regulation of Vibrio polysaccharide synthesis and virulence factor production by CdgC, a GGDEF-EAL domain protein, in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 189:717-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linkous, D. A., and J. D. Oliver. 1999. Pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mah, T. F., and G. A. O'Toole. 2001. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 9:34-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marco-Noales, E., M. Milan, B. Fouz, E. Sanjuan, and C. Amaro. 2001. Transmission to eels, portals of entry, and putative reservoirs of Vibrio vulnificus serovar E (biotype 2). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4717-4725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsukawa, M., and E. P. Greenberg. 2004. Putative exopolysaccharide synthesis genes influence Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 186:4449-4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matz, C., D. McDougald, A. M. Moreno, P. Y. Yung, F. H. Yildiz, and S. Kjelleberg. 2005. Biofilm formation and phenotypic variation enhance predation-driven persistence of Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:16819-16824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McDougald, D., W. H. Lin, S. A. Rice, and S. Kjelleberg. 2006. The role of quorum sensing and the effect of environmental conditions on biofilm formation by strains of Vibrio vulnificus. Biofouling 22:133-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Méndez-Ortiz, M. M., M. Hyodo, Y. Hayakawa, and J. Membrillo-Hernandez. 2006. Genome-wide transcriptional profile of Escherichia coli in response to high levels of the second messenger 3′,5′-cyclic diguanylic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8090-8099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monds, R. D., P. D. Newell, R. H. Gross, and G. A. O'Toole. 2007. Phosphate-dependent modulation of c-di-GMP levels regulates Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 biofilm formation by controlling secretion of the adhesin LapA. Mol. Microbiol. 63:656-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris, J. G., Jr. 2003. Cholera and other types of vibriosis: a story of human pandemics and oysters on the half shell. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nair, R., and B. Rost. 2005. Mimicking cellular sorting improves prediction of subcellular localization. J. Mol. Biol. 348:85-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakhamchik, A., C. Wilde, and D. A. Rowe-Magnus. 2007. Identification of a Wzy polymerase required for group IV capsular polysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Vibrio vulnificus. Infect. Immun. 75:5550-5558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oliver, J. D. 1989. Vibrio vulnificus, p. 570-600. In M. P. Doyle (ed.), Food-borne bacterial pathogens. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, NY.

- 60.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:449-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paranjpye, R. N., and M. S. Strom. 2005. A Vibrio vulnificus type IV pilin contributes to biofilm formation, adherence to epithelial cells, and virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:1411-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paul, R., S. Weiser, N. C. Amiot, C. Chan, T. Schirmer, B. Giese, and U. Jenal. 2004. Cell cycle-dependent dynamic localization of a bacterial response regulator with a novel di-guanylate cyclase output domain. Genes Dev. 18:715-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peleg, A., Y. Shifrin, O. Ilan, C. Nadler-Yona, S. Nov, S. Koby, K. Baruch, S. Altuvia, M. Elgrably-Weiss, C. M. Abe, S. Knutton, M. A. Saper, and I. Rosenshine. 2005. Identification of an Escherichia coli operon required for formation of the O-antigen capsule. J. Bacteriol. 187:5259-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pelkonen, S., and J. Finne. 1989. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of capsular polysaccharides of bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 179:104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pelkonen, S., J. Hayrinen, and J. Finne. 1988. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the capsular polysaccharides of Escherichia coli K1 and other bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 170:2646-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ponting, C. P., and L. Aravind. 1997. PAS: a multifunctional domain family comes to light. Curr. Biol. 7:R674-R677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pratt, J. T., R. Tamayo, A. D. Tischler, and A. Camilli. 2007. PilZ domain proteins bind cyclic diguanylate and regulate diverse processes in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 282:12860-12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rashid, M. H., C. Rajanna, A. Ali, and D. K. Karaolis. 2003. Identification of genes involved in the switch between the smooth and rugose phenotypes of Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 227:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rashid, M. H., C. Rajanna, D. Zhang, V. Pasquale, L. S. Magder, A. Ali, S. Dumontet, and D. K. Karaolis. 2004. Role of exopolysaccharide, the rugose phenotype and VpsR in the pathogenesis of epidemic Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reisner, A., J. A. Haagensen, M. A. Schembri, E. L. Zechner, and S. Molin. 2003. Development and maturation of Escherichia coli K-12 biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 48:933-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roberts, I. S. 1996. The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:285-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Römling, U., and D. Amikam. 2006. Cyclic di-GMP as a second messenger. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:218-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Römling, U., M. Gomelsky, and M. Y. Galperin. 2005. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ross, P., Y. Aloni, C. Weinhouse, D. Michaeli, P. Weinberger-Ohana, R. Meyer, and M. Benziman. 1985. An unusual guanyl oligonucleotide regulates cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. FEBS Lett. 186:191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ross, P., Y. Aloni, H. Weinhouse, D. Michaeli, P. Weinberger-Ohana, R. Mayer, and M. Benziman. 1986. Control of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. A unique guanyl oligonucleotide is the immediate activator of the cellulose synthase. Carbohydr. Res. 149:101-117. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ross, P., H. Weinhouse, Y. Aloni, D. Michaeli, P. Weinberger-Ohana, R. Mayer, S. Braun, E. de Vroom, G. A. van der Marel, J. H. van Boom, and M. Benziman. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ryan, R. P., Y. Fouhy, J. F. Lucey, B. L. Jiang, Y. Q. He, J. X. Feng, J. L. Tang, and J. M. Dow. 2007. Cyclic di-GMP signalling in the virulence and environmental adaptation of Xanthomonas campestris. Mol. Microbiol. 63:429-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ryjenkov, D. A., M. Tarutina, O. V. Moskvin, and M. Gomelsky. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J. Bacteriol. 187:1792-1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Simon, R., U. B. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Starks, A. M., T. R. Schoeb, M. L. Tamplin, S. Parveen, T. J. Doyle, P. E. Bomeisl, G. M. Escudero, and P. A. Gulig. 2000. Pathogenesis of infection by clinical and environmental strains of Vibrio vulnificus in iron-dextran-treated mice. Infect. Immun. 68:5785-5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stewart, P. S. 2001. Multicellular resistance: biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 9:204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Strom, M. S., and R. N. Paranjpye. 2000. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbes Infect. 2:177-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tischler, A. D., and A. Camilli. 2004. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 53:857-869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tischler, A. D., and A. Camilli. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate regulates Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 73:5873-5882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Todd, E. C. 1989. Costs of acute bacterial foodborne disease in Canada and the United States. International J. Food Microbiol. 9:313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wai, S. N., Y. Mizunoe, A. Takade, S. I. Kawabata, and S. I. Yoshida. 1998. Vibrio cholerae O1 strain TSI-4 produces the exopolysaccharide materials that determine colony morphology, stress resistance, and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3648-3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wai, S. N., Y. Mizunoe, and S. Yoshida. 1999. How Vibrio cholerae survive during starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 180:123-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Whitfield, C. 2006. Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:39-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wright, A. C., R. T. Hill, J. A. Johnson, M. C. Roghman, R. R. Colwell, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 1996. Distribution of Vibrio vulnificus in the Chesapeake Bay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:717-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wright, A. C., J. L. Powell, J. B. Kaper, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 2001. Identification of a group 1-like capsular polysaccharide operon for Vibrio vulnificus. Infect. Immun. 69:6893-6901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wright, A. C., J. L. Powell, M. K. Tanner, L. A. Ensor, A. B. Karpas, J. G. Morris, Jr., and M. B. Sztein. 1999. Differential expression of Vibrio vulnificus capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 67:2250-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wright, A. C., L. M. Simpson, J. D. Oliver, and J. G. Morris, Jr. 1990. Phenotypic evaluation of acapsular transposon mutants of Vibrio vulnificus. Infect. Immun. 58:1769-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wugeditsch, T., A. Paiment, J. Hocking, J. Drummelsmith, C. Forrester, and C. Whitfield. 2001. Phosphorylation of Wzc, a tyrosine autokinase, is essential for assembly of group 1 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 276:2361-2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:4028-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yip, E. S., B. T. Grublesky, E. A. Hussa, and K. L. Visick. 2005. A novel, conserved cluster of genes promotes symbiotic colonization and sigma-dependent biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1485-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yoshida, S., M. Ogawa, and Y. Mizuguchi. 1985. Relation of capsular materials and colony opacity to virulence of Vibrio vulnificus. Infect. Immun. 47:446-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu, C.-S., C.-J. Lin, and J.-K. Hwang. 2004. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins for gram-negative bacteria by support vector machines based on n-peptide compositions. Protein Sci. 13:1402-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhulin, I. B., B. L. Taylor, and R. Dixon. 1997. PAS domain S-boxes in archaea, bacteria and sensors for oxygen and redox. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:331-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]