Abstract

Biphenyl dioxygenase from the psychrotolerant bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain Cam-1 (BPDOCam-1) was purified and found to have an apparent  for biphenyl of 1.1 ± 0.1 s−1 (mean ± standard deviation) at 4°C. In contrast, BPDOLB400 from the mesophile Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 had no detectable activity at this temperature. At 57°C, the half-life of the BPDOCam-1 oxygenase was less than half that of the BPDOLB400 oxygenase. Nevertheless, BPDOCam-1 appears to be a typical Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707-type dioxygenase.

for biphenyl of 1.1 ± 0.1 s−1 (mean ± standard deviation) at 4°C. In contrast, BPDOLB400 from the mesophile Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 had no detectable activity at this temperature. At 57°C, the half-life of the BPDOCam-1 oxygenase was less than half that of the BPDOLB400 oxygenase. Nevertheless, BPDOCam-1 appears to be a typical Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707-type dioxygenase.

The cold-tolerant bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain Cam-1, previously isolated from Arctic soil, transforms polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) with up to four chloro substituents at 7°C at higher rates than Burkholderia xenovorans LB400, a well-characterized PCB-degrading mesophilic bacterium (2, 14). At 50°C, PCB removal by Cam-1 was diminished, but that by LB400 was not (14). The degradation of PCBs by these two strains is further distinguished by their respective congener preferences. LB400 preferentially degrades ortho-substituted PCBs with up to six chloro substituents (6). In contrast, the congener preference of Cam-1 is similar to that of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707, preferentially degrading para-substituted PCBs with up to four chloro substituents (6). A third well-characterized mesophilic PCB-degrading bacterium, Pandoraea pnomenusa B-356 (previously Comamonas testosteroni B-356), preferentially transforms meta-substituted congeners with up to four chloro substituents (1).

The first enzyme of the biphenyl/PCB-degrading pathway, biphenyl dioxygenase (BPDO), is one of the major determinants of the aerobic PCB-degrading capabilities of bacteria (17). Accordingly, the PCB-degrading capabilities of strains LB400 and B-356 largely reflect those of BPDOLB400 and BPDOB356, respectively (7). BPDO is a three-component dioxygenase comprising a reductase, a ferredoxin, and an oxygenase component (iron-sulfur protein [ISP]) of α3β3 constitution. The α-subunit contains a Rieske FeS cluster and, within the active site, a mononuclear iron center. BPDO utilizes NADH to activate O2 and catalyze the 2,3-dihydroxylation of biphenyl. A crystal structure of ISPB356, the oxygenase component of BPDOB356, in complex with 2,6-dichlorobiphenyl has provided insight into the determinants of congener preference in BPDOs (7). For instance, Phe336 of ISPLB400 decreases the preference of this enzyme for di-para-substituted congeners (7). Moreover, BPDOs have been engineered to improve their PCB-degrading capabilities (3, 5, 18).

The oxygenase component of BPDOCam-1 shares 99%, 95%, and 70% amino acid sequence identities with those of BPDOKF707, BPDOLB400, and BPDOB356, respectively. Indeed, the α-subunits of ISPCam-1 and ISPKF707 differ by a single residue at position 178 (Ala in ISPCam-1 and Val in ISPKF707) (13). To better understand the differences between the various BPDOs and their influence on the temperature dependence of PCB degradation by the parent strains (14), BPDOCam-1 was heterologously produced and purified. The biphenyl- and PCB-transforming activities of BPDOCam-1 were evaluated and compared with the data for BPDOLB400, BPDOB356, and BPDOKF707. The impact of temperature on the activities and stabilities of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 were also compared to evaluate whether the former is cold adapted.

Reconstitution of BPDOCam-1.

ISPCam-1 and ISPLB400, the oxygenase components of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400, respectively, were produced in Escherichia coli strain C41(DE3) (15) by using derivatives of pT7-6a and pT7-7a, respectively (8, 13). The ISPs were purified and handled anaerobically in a glovebox, concentrated to 20 to 30 mg/ml, and flash frozen as beads in liquid nitrogen essentially as described previously (7, 11). The yields of ISPLB400 and ISPCam-1 were approximately 15 and 23 mg/liter of cell culture, respectively, and the R values (A280/A323) and iron and sulfur content of these preparations indicated that the ISPs contained essentially their full complements of Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] clusters and mononuclear iron centers (11). BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 were reconstituted by using His-tagged ferredoxin from LB400 (Ht-BphFLB400) and His-tagged reductase from B-356 (Ht-BphGB356) (4, 10). The specific activities of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 were 3.1 ± 0.4 (mean ± standard deviation) and 0.27 ± 0.01 U/mg, respectively, at 25°C. The sequences of BphFLB400 and BphFCam-1 are identical, and the results of a previous study indicate that exchanging electron transfer components between closely related BPDOs, including using Ht-BphGB356, does not significantly affect enzyme activity (10). Thus, differences in the activities and steady-state parameters of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 reflect differences in the respective ISPs of these systems.

A comparative analysis of BPDOCam-1 reactivity.

The steady-state parameters of BPDO for biphenyl were evaluated by following the consumption of O2 as previously described (7, 11). All experiments were performed by using air-saturated 50 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES), pH 6.0, and the assay mixtures contained 0.6 μM ISP, 3.6 μM Ht-BphFLB400, 1.8 μM Ht-BphGB356, 320 μM NADH, and 0.5 to 160 μM biphenyl. Under all conditions studied, the steady-state consumption of O2 by BPDO as a function of biphenyl concentration obeyed Michaelis-Menten kinetics with the fitted parameters shown in Table 1. Moreover, the hydroxylation of biphenyl was well coupled to O2 activation. That is, in the presence of 160 μM biphenyl and excess NADH, the amount of O2 consumed by BPDOCam-1 corresponded to the amount of biphenyl utilized (Table 2) and no H2O2 was detected upon the addition of catalase to these reaction mixtures. At 25°C, the steady-state utilization of biphenyl by BPDOCam-1 was remarkably similar to that of BPDOB356 (apparent kcat [ ] = 4.1 ± 0.2 s−1 and

] = 4.1 ± 0.2 s−1 and  = 20 ± 4 μM [7]) and different from that of BPDOLB400 previously measured under similar conditions. More particularly, the

= 20 ± 4 μM [7]) and different from that of BPDOLB400 previously measured under similar conditions. More particularly, the  values of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOB356 for biphenyl are 10 times higher than that of BPDOLB400, while the apparent specificities (

values of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOB356 for biphenyl are 10 times higher than that of BPDOLB400, while the apparent specificities ( /

/ ) of the former are approximately 1/10 that of BPDOLB400. This is true of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 at 10°C as well. However, BPDOLB400 did not detectably transform biphenyl at 4°C.

) of the former are approximately 1/10 that of BPDOLB400. This is true of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 at 10°C as well. However, BPDOLB400 did not detectably transform biphenyl at 4°C.

TABLE 1.

Effect of temperature on the reactivities of purified BPDOs with biphenyla

| Temp (°C) | BPDOCam-1

|

BPDOLB400

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

(s−1) (s−1) |

(μM) (μM) |

(s−1) (s−1) |

(μM) (μM) |

|

| 4 | 1.1 (0.1) | 18 (3) | ND | NA |

| 10 | 2.2 (0.1) | 11 (1) | 0.26 (0.01) | 1.6 (0.3) |

| 25 | 4.6 (0.2) | 29 (3) | 0.4 (0.1)b | 0.18 (0.03)b |

Values in parentheses represent standard errors (n = 3 or 4). ND, not detected; NA, data not available.

Data taken from Gomez-Gil et al., in which assay mixtures contained 0.6 μM ISP, 3.6 μM Ht-BphFLB400, 1.8 μM Ht-BphGB356, 350 μM NADH, and 0.1 to 150 μM biphenyl (7).

TABLE 2.

Reactivities of purified BPDOs with selected biphenyls at 25°Ca

| Congener | BPDOCam-1

|

BPDOLB400b

|

BPDOB356b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of congener removal (nmol·min−1) | H2O2/O2 | Rate of congener removal (nmol·min−1) | H2O2/O2 | Rate of congener removal (nmol·min−1) | H2O2/O2 | |

| Biphenyl | 95 (9) | ND | 12 (4) | ND | 55.3 (0.6) | ND |

| 2,2′-Dichlorobiphenyl | 3.2 (0.3) | 0.36 (0.01) | 15 (4) | ND | 15 (1) | 0.6 (0.2) |

| 3,3′-Dichlorobiphenyl | 8 (2) | 0.40 (0.05) | 6 (2) | 0.3 (0.1) | 32.2 (0.2) | 0.20 (0.04) |

| 4,4′-Dichlorobiphenyl | 2.6 (0.1) | 0.26 (0.05) | 3.9 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.2) | 9 (5) | 0.4 (0.2) |

O2 consumption (H2O2/O2 ratios) values are based on the assumption that the amount of O2 detected upon catalase addition corresponds to 50% of H2O2 produced. The rates of congener removal and H2O2/O2 ratios are based on data obtained after 1.5 min for biphenyl and after 3 min for dichlorobiphenyls. Values in parentheses represent standard errors (n = 3 or 4). ND, not detected.

Data taken from Gomez-Gil et al., in which assay mixtures contained 50 μM of each congener (7).

In studying the congener preference of BPDOCam-1, it was found that the enzyme depleted biphenyls in the following order of apparent maximal rates at 25°C: biphenyl ≫ 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl > 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl ≈ 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl (Table 2). Thus, as with the steady-state kinetic parameters of biphenyl utilization, the congener preference of BPDOCam-1 is similar to that of BPDOB356 (biphenyl > 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl > 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl ≈ 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl) and distinct from that of BPDOLB400 (biphenyl > 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl > 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl > 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl) (7, 11). Consistent with what has been reported for BPDOB356 and BPDOLB400, the utilization of O2 by BPDOCam-1 in the presence of 68 μM 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl, 80 μM 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl, or 40 μM 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl was not fully coupled (Table 2). The extent of uncoupling between O2 and dichlorobiphenyl utilization was dependent on both the isozyme and the PCB congener. For example, BPDOCam-1 was significantly more uncoupled in the presence of 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl than BPDOLB400 (Table 2). Moreover, the uncoupling was not necessarily lowest for dichlorobiphenyls that were depleted at the highest rates.

In general, the congener preference data reported for the purified BPDOs are consistent with those reported for the parent strains in whole-cell assays, except that whole cells of strains Cam-1 and B-356 depleted 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl very poorly, if at all. Thus, in contrast to the purified BPDOs, cells of strain Cam-1 did not detectably transform 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl (14) and B-356 cells depleted 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl better than 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl (1, 11). While these data might reflect the low sensitivity of the whole-cell assay, it is possible that PCB transformation by whole cells is determined by other factors, such as PCB transport across cell membranes and the presence of other PCB-transforming enzymes in the cell. Finally, differences in apparent congener preference between whole cells and purified BPDO might reflect the enzyme's relative protection against oxidative damage in whole cells. Notably, whole-cell assays are typically conducted over much-longer periods of time (hours) than enzyme assays (minutes).

To investigate the poor transformation of 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl by whole cells and to facilitate comparisons of results for BPDOCam-1 with whole-cell data for BPDOKF707 (18), PCB removal by E. coli C41(DE3) cells freshly transformed with pT7-7a (bphAEFGCam-1) was tested (Table 3) as described previously (7). These data are consistent with the results of previous studies of Pseudomonas sp. strain Cam-1 (14) but differ from the current data obtained with purified BPDOCam-1, which removed 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl and 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyls at similar rates. Importantly, these experimental results establish that in whole cells of E. coli, BPDOKF707 and BPDOCam-1 have the same apparent preference for 3,3′-dichlorobiphenyl and 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyls and that both enzymes transform these congeners at significantly higher rates than biphenyl (18). These data further indicate that the congener preferences of BPDOCam-1, BPDOKF707, and BPDOB356 are quite similar.

TABLE 3.

Depletion of biphenyls by E. coli cells containing BPDOCam-1

| Congener | % Depletion ata:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 3 h | 6 h | |

| Biphenyl | 59 (10) | 100 (0) |

| 2,2′-Dichlorobiphenyl | 38 (1) | 64 (3) |

| 3,3′-Dichlorobiphenyl | 95 (1) | 100 (0) |

| 4,4′-Dichlorobiphenyl | 99 (1) | 98 (1) |

Values in parentheses represent standard errors (n = 3).

Temperature dependence of BPDO activity.

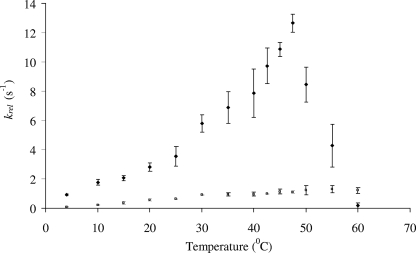

The dependence of BPDO activity on temperature was investigated by performing the standard activity assay at temperatures from 4 to 60°C (Fig. 1). In the results of the standard assay, the concentration of biphenyl exceeded the BPDOs'  for this substrate by approximately an order of magnitude. Studies of BPDOB356 indicate that this is also the case for O2 (

for this substrate by approximately an order of magnitude. Studies of BPDOB356 indicate that this is also the case for O2 ( = 28 μM [11]). The relative activities of the enzymes should therefore be essentially unaffected by temperature-dependent changes in the solubility of the two substrates. At any given temperature between 4 and 45°C, the activity of BPDOCam-1 was higher than that of BPDOLB400. As noted above, at 4°C, the activity of BPDOLB400 did not differ significantly from the background rate, whereas BPDOCam-1 transformed biphenyl at a significant rate (Table 1). Further, the highest observed activity of BPDOCam-1 occurred at a lower temperature than that of BPDOLB400 (47°C versus 55°C). The thermodynamic parameters were derived from Arrhenius plots (9, 12) by using the data up to 42.5°C and 35°C for BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400, respectively (Table 4). The free energy of activation (ΔG‡) of BPDOCam-1 is lower than that of BPDOLB400, consistent with the former's higher

= 28 μM [11]). The relative activities of the enzymes should therefore be essentially unaffected by temperature-dependent changes in the solubility of the two substrates. At any given temperature between 4 and 45°C, the activity of BPDOCam-1 was higher than that of BPDOLB400. As noted above, at 4°C, the activity of BPDOLB400 did not differ significantly from the background rate, whereas BPDOCam-1 transformed biphenyl at a significant rate (Table 1). Further, the highest observed activity of BPDOCam-1 occurred at a lower temperature than that of BPDOLB400 (47°C versus 55°C). The thermodynamic parameters were derived from Arrhenius plots (9, 12) by using the data up to 42.5°C and 35°C for BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400, respectively (Table 4). The free energy of activation (ΔG‡) of BPDOCam-1 is lower than that of BPDOLB400, consistent with the former's higher  . However, determination of the apparent steady-state parameters of the two BPDOs at 10°C revealed that their respective catalytic efficiencies (

. However, determination of the apparent steady-state parameters of the two BPDOs at 10°C revealed that their respective catalytic efficiencies ( /

/ ) were not significantly different (see Table 1).

) were not significantly different (see Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Effects of increasing temperature on the biphenyl-degrading activities of ISPCam-1 (♦) and ISPLB400 (□) (n = 3; error bars indicate standard deviations). krel, relative kcat.

TABLE 4.

Thermodynamic parameters of ISPCam-1 and ISPLB400 with biphenyl at 25°Ca

| Source of ISP | ΔG‡ (kJ mol−1) | ΔH‡ (kJ mol−1) | TΔS‡ (kJ mol−1 K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. strain Cam-1 | 69.9 (0.05) | 38 (2) | −32 (2) |

| B. xenovorans LB400 | 74.2 (0.07) | 48 (5) | −26 (5) |

ΔG‡, free energy of activation; ΔH‡, enthalpy of activation; TΔS‡, product of temperature and entropy of activation. Values in parentheses represent standard errors (n = 3 or 4).

Finally, we investigated the respective half-lives of ISPCam-1 and ISPLB400 at 57°C by following the characteristic absorbance of the iron-sulfur cluster of these proteins: this temperature was chosen because the enzymes lost activity at a significant rate above 50°C. Briefly, a sample of each ISP was diluted to 2.2 μM in MES buffer (pH 6.0) preequilibrated to 57°C. The sample was incubated at 57°C, and its absorbance was continuously monitored at 323 nm, where a decrease in absorbance reflects loss of the Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] cluster and, thus, loss of ISP function. The half-lives of ISPCam-1 and ISPLB400 were 16 ± 2 min and 38 ± 8 min, respectively. The longer half-life of ISPLB400 at 57°C is consistent with the higher relative kcat of BPDOLB400 that was observed at temperatures above 50°C.

The principal distinguishing characteristic of cold-adapted enzymes is a significant decrease of their enthalpy of activation (ΔH‡) with respect to that of their mesophilic homologues (5 to 42 kJ mol−1), which contributes to a higher  at lower temperatures (12). Cold-adapted enzymes also tend to be less thermostable than their mesophilic homologues. Thus, comparison of these two characteristics of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 could be interpreted to indicate that BPDOCam-1 is cold adapted. However, several considerations argue that ISPCam-1 is not cold adapted. First, the difference in ΔH‡ of the two reactions (10 kJ mol−1) is at the low end of that which distinguishes mesophilic from psychrophilic enzymes. Second, the steady-state kinetic parameters of BPDOCam-1 for biphenyl at 25°C are similar to those reported for a mesophilic enzyme, BPDOB356, determined under similar conditions (7, 11). Third, the specificities of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 for biphenyl (

at lower temperatures (12). Cold-adapted enzymes also tend to be less thermostable than their mesophilic homologues. Thus, comparison of these two characteristics of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 could be interpreted to indicate that BPDOCam-1 is cold adapted. However, several considerations argue that ISPCam-1 is not cold adapted. First, the difference in ΔH‡ of the two reactions (10 kJ mol−1) is at the low end of that which distinguishes mesophilic from psychrophilic enzymes. Second, the steady-state kinetic parameters of BPDOCam-1 for biphenyl at 25°C are similar to those reported for a mesophilic enzyme, BPDOB356, determined under similar conditions (7, 11). Third, the specificities of BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 for biphenyl ( /

/ ) are not significantly different at 10°C, contrary to what has been observed in other cold-adapted enzymes (9). Fourth, the α-subunit of ISPCam-1, which encompasses the BPDO active site, is almost identical to that of another mesophilic enzyme, ISPKF707.

) are not significantly different at 10°C, contrary to what has been observed in other cold-adapted enzymes (9). Fourth, the α-subunit of ISPCam-1, which encompasses the BPDO active site, is almost identical to that of another mesophilic enzyme, ISPKF707.

Overall, our data suggest that BPDOCam-1 is a typical KF707-type enzyme. Nishi et al. (16) reported that Pseudomonas putida KF715 encodes a KF707-type BPDO on a 90-kbp conjugative element (16). Thus, it is conceivable that such an element was transferred to a psychrotolerant Pseudomonas species, such as Cam-1. It is nonetheless possible that ISPCam-1 is less stable than ISPKF707 and ISPLB400. In particular, the β-subunits of ISPLB400 and ISPKF707 differ by a single residue and they differ from the β-subunit of ISPCam-1 by the same five residues (Arg16, Pro33, Gln34, Pro40, and Phe79 in ISPCam-1). Inspection of the crystallographic structure of ISPB356 reveals that all five residues occur at or very close to subunit interfaces. Perhaps the most intriguing of these is Pro33 in ISPCam-1, which is an arginine residue in ISPLB400, ISPKF707, and ISPB356. In ISPB356, this arginine is involved in an extensive network of hydrogen bonds involving residues at the interface of adjacent β-subunits. The loss of this network in ISPCam-1 could influence this enzyme's thermostability.

Although the combined data reported here suggest that BPDOCam-1 is not cold-adapted, the differences between BPDOCam-1 and BPDOLB400 nevertheless account for the differences between their respective parental strains, Cam-1 and LB400. Thus, whole cells of Cam-1 remove certain PCB congeners at higher rates than LB400 cells at 7°C (14). Furthermore, PCB removal by LB400 increased at high temperature; in contrast, high temperature inhibited PCB removal by Cam-1. Both observations are consistent with the higher  of BPDOCam-1 for biphenyl at low temperature and the low thermal stability of BPDOCam-1 compared to that of BPDOLB400. Overall, the current data indicate that a distinguishing feature of KF707- and LB400-type enzymes is the formers' superior ability to degrade PCBs at low temperatures.

of BPDOCam-1 for biphenyl at low temperature and the low thermal stability of BPDOCam-1 compared to that of BPDOLB400. Overall, the current data indicate that a distinguishing feature of KF707- and LB400-type enzymes is the formers' superior ability to degrade PCBs at low temperatures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada Strategic grant 224153-99 (to L.D.E. and J.B.P.) and Discovery grants (to W.W.M. and L.D.E.). E.R.M. and N.Y.R.A. were recipients of NSERC postgraduate scholarships.

Michel Sylvestre (Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique-Santé, Université du Québec) provided the expression system for Ht-BphGB356. Manon M. J. Couture provided the expression system for Ht-BphFLB400.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barriault, D., C. Pelletier, Y. Hurtubise, and M. Sylvestre. 1997. Substrate selectivity pattern of Comamonas testosteroni B-356 towards dichlorobiphenyls. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 39:311-316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bopp, L. H. 1986. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruhlmann, F., and C. Wilfred. 1999. Tuning biphenyl dioxygenase for extended substrate specificity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 63:544-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couture, M. M.-J., C. L. Colbert, E. Babini, F. I. Rosell, G. Mauk, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 2001. Characterization of BphF, a Rieske-type ferredoxin with low reduction potential. Biochemistry 40:84-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furukawa, K. 2000. Engineering dioxygenases for efficient degradation of environmental pollutants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 11:244-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson, D. T., D. L. Cruden, J. D. Haddock, G. J. Zylstra, and J. M. Brand. 1993. Oxidation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400 and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J. Bacteriol. 175:4561-4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez-Gil, L., P. Kumar, D. Barriault, J. T. Bolin, M. Sylvestre, and L. D. Eltis. 2007. Characterization of biphenyl dioxygenase of Pandoraea pnomenusa B-356 as a potent polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 189:5705-5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofer, B., L. D. Eltis, D. N. Dowling, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Genetic analysis of a Pseudomonas locus encoding a pathway for biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. Gene 130:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoyoux, A., I. Jennes, P. Dubois, S. Genicot, F. Dubail, J. M. Francois, E. Baise, G. Feller, and C. Gerday. 2001. Cold-adapted β-galactosidase from the Antarctic psychrophile Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1529-1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurtubise, Y., D. Barriault, and M. Sylvestre. 1998. Involvement of the terminal oxygenase β subunit in the biphenyl dioxygenase reactivity pattern toward chlorobiphenyls. J. Bacteriol. 180:5828-5835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imbeault, N. Y. R., J. B. Powlowski, C. L. Colbert, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 2000. Steady-state kinetic characterization and crystallization of a polychlorinated biphenyl-transforming dioxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12430-12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonhienne, T., C. Gerday, and G. Feller. 2000. Psychrophilic enzymes: revisiting the thermodynamic parameters of activation may explain local flexibility. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1543:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Master, E. R., and W. W. Mohn. 2001. Induction of bphA, encoding biphenyl dioxygenase, in two polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading bacteria, psychrotolerant Pseudomonas strain Cam-1 and mesophilic Burkholderia strain LB400. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2669-2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Master, E. R., and W. W. Mohn. 1998. Psychrotolerant bacteria isolated from Arctic soil that degrade polychlorinated biphenyls at low temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4823-4829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miroux, B., and J. E. Walker. 1996. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 260:289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishi, A., K. Tominaga, and K. Furukawa. 2000. A 90-kilobase conjugative chromosomal element coding for biphenyl and salicylate catabolism in Pseudomonas putida KF715. J. Bacteriol. 182:1949-1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pieper, D. H. 2005. Aerobic degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67:170-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suenaga, H., T. Watanabe, M. Sato, Ngadiman, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Alteration of regiospecificity in biphenyl dioxygenase by active-site engineering. J. Bacteriol. 184:3682-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]