Abstract

In recent years, reports have identified that many eukaryotic proteins contain disordered regions spanning greater than 30 consecutive residues in length. In particular, a number of these intrinsically disordered regions occur in the cytoplasmic segments of plasma membrane proteins. These intrinsically disordered regions play important roles in cell signaling events, as they are sites for protein-protein interactions and phosphorylation. Unfortunately, in many crystallographic studies of membrane proteins, these domains are removed because they hinder the crystallization process. Therefore, a purification procedure was developed to enable the biophysical and structural characterization of these intrinsically disordered regions while still associated with the lipid environment. The carboxyl-terminal domain from the gap junction protein connexin43 attached to the 4th transmembrane domain (TM4-Cx43CT) was used as a model system (residues G178-I382). The purification was optimized for structural analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) because this method is well suited for small membrane proteins and proteins that lack a well-structured three-dimensional fold. The TM4-Cx43CT was purified to homogeneity with a yield of ~6 mg per liter from C41(DE3) bacterial cells, reconstituted in the anionic detergent 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-RAC-(1-glycerol)], and analyzed by circular dichroism and NMR to demonstrate that the TM4-Cx43CT was properly folded into a functional conformation by its ability to form α-helical structure and associate with a known binding partner, the c-Src SH3 domain, respectively.

Gap junctions are integral membrane proteins that serve to directly interconnect the cytoplasm of neighboring cells, allowing the passage of ions, metabolites, and signaling molecules. They provide a pathway for the propagation and/or amplification of signal transduction cascades triggered by cytokines, growth factors, and other cell signaling molecules involved in growth regulation and development. Mammalian gap junction channels are formed by as many as 21 different connexin proteins (1). Of these, connexin43 (Cx43) is the most abundant connexin and best characterized isoform in terms of channel gating properties (2–4), phosphorylation sites (5–7), mechanisms of pH sensitivity (8–11), and overall molecular structure (12). Cx43 is essential for normal cell growth (13), cardiac embryogenesis (14), and glial intercellular communication (15). The functional importance of Cx43 has been illustrated through the identification of mutations that are associated with the human disease oculodentodigital dysplasia (16).

Cx43 is a tetraspan membrane protein with intracellular N- and C-termini. The Cx43 gap junction structure was initially determined by electron crystallography at 18 Å resolution by Unwin and Zampighi (17) and later at 7.5 Å resolution by Unger et al. (18). These studies helped provide the first molecular view towards understanding the architecture of the channel. While the protein used in the Unger et al. (18) study was able to form functional channels (19,20), most of the carboxyl terminal domain (CT) was removed (residues 263–382) to improve the diffraction quality of the two-dimensional crystals (21). Using a soluble version of the CT domain from Cx43 (Cx43CT; residues 255–382), we identified by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) that the Cx43CT is highly flexible and predominately disordered in structure (11,22,23). The Cx43CT structure exemplifies many previous observations that highly flexible or completely unfolded fragments dramatically interfere with the crystallization process (24,25). Based on the estimation that 41% of human membrane proteins have intrinsically disordered regions with more than 30 consecutive residues and these residues are preferentially localized at the cytoplasmic side (26), as well as, intrinsically disordered domains have been identified as playing an important role in cell signaling events (27), novel protein purification strategies need to be developed not only to be able to characterize the structure-function correlates of these intrinsically disordered domains, but to characterize them when attached to the membrane.

Studies of the soluble Cx43CT indicate that the microenvironment of a soluble polypeptide versus that of the same sequence in the context of the native protein embedded in a lipid bilayer may not be the same (23,28). For example, NMR studies indicate that the N-terminus of the soluble Cx43CT is highly flexible in comparison to the C-terminal domain and this maybe affecting the binding affinity of molecular partners interactions, whereas its association with the 4th transmembrane domain would provide the N-terminus with a more rigid and stable conformation. Also, region G261-N300, which is essential for normal pH gating (29), contains a region rich in proline residues. Proline-rich sequences commonly form left-handed type II polyproline helices (30,31), which was not observe in the NMR structure. These differences can be attributed to the constraints afforded by attachment to the membrane. Therefore, a purification and reconstitution protocol was developed to enable the biophysical characterization and structural determination by NMR methods of the CT when attached to the 4th transmembrane domain of Cx43 (TM4-Cx43CT) in detergent micelles. NMR is an ideal spectroscopic tool to characterize the structure and dynamics of intrinsically disordered proteins (32,33), unfortunately, size limitations do not support the feasibility of working with large molecular weight membrane proteins, such as the full-length Cx43. In general, this methodology will also be useful for the purification and reconstitution of other membrane-associated intrinsically disordered domains.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

DNA encoding the TM4-Cx43CT (G178-I382) was cloned by PCR from a G2A plasmid containing the Rattus norvegicus Cx43 gene and ligated into the E. coli pET-14b expression vector (N-terminal 6x His-tag and thrombin cleavage site) (Novagen) using the restriction enzymes Nde1 and Xho1. All constructs were verified by the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s DNA Sequencing Core Facility.

Protein expression and purification

The E. coli strains BL21(DE3) (Novagen), Rosetta-2(DE3) (Novagen), C41(DE3) (Lucigen, (34)), and C43(DE3) (Lucigen, (34)) were transformed with the TM4-Cx43CT expression plasmid (see above) and then inoculated into 1 L of Luria Bertani medium (LB), enriched minimal media (35), or ISOGRO media (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were incubated at 37°C with continuous agitation. At an optical density of 0.6 at 600 nm, 1.0 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added, and growth was allowed to proceed for 4 hrs (typical optical density ~ 1.6). The cells were harvested by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 45 min), washed with PBS buffer, and stored at −20°C.

Cells were suspended in 1x PBS buffer with a bacterial protease inhibitor cocktail (250 µl/5g cells; Sigma-Aldrich) and disrupted with three passages through either an Emulsiflex or a French pressure cell at 15,000 psi. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (1,000 × g for 30 min) and a pellet containing the inclusion bodies was collected by a high-speed centrifugation step (25,000 × g for 45 min). The pellet was resuspended in 8 M urea, 1x PBS (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, and 20 mM imidazole and placed on a rocker at 4°C for ~2 hrs. The suspension was centrifuged again (25,000 × g for 45 min) and the supernatant was loaded onto a HisTrap HP affinity chromatography column using an ÄKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare). The TM4-Cx43CT polypeptides were eluted at 300 mM imidazole using a step gradient of 20, 40, 80, 100, 300, and 500 mM imidazole. Prior to the 300 mM imidazole elution step, four column volumes of a buffer containing 8 M urea, 1x PBS (pH 8.0), 1% Triton X-100, and 10% ethanol was used to wash the bound 6x His-tag TM4-Cx43CT. Fractions containing the TM4-Cx43CT were identified by SDS-PAGE. An estimate of the amount of TM4-Cx43CT after the HisTrap HP column when compared to BSA on a SDS-PAGE was ~6.0 mg/L of bacterial culture. The samples were pooled and dialyzed overnight at 4°C using a 10 kDa Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassette (Pierce) against 1 M urea, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM EDTA. The precipitate was collected and centrifuged (300 × g for 5 min), washed once with water, and resuspended in 500 µL of 20 mM MES buffer (pH 5.8), 100 mM NaCl, and 8% 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-RAC-(1-glycerol)] (LPPG) at 42°C for 30 min. Previously, we determined that a detergent concentration of 8% and a temperature of 42°C were the most optimal conditions in terms of producing high quality NMR spectra and increasing sample lifetimes for membrane proteins (36). All proteins were analyzed by Coomassie blue stained 15% SDS-PAGE gels.

NMR experiments

NMR data were acquired at 42°C using a 600 MHz Varian INOVA NMR spectrometer fitted with a cryo-probe at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s NMR Shared Resource Facility. Gradient-enhanced two-dimensional 15N-HSQC experiments (37) were used to observe all backbone amide resonances in 15N-labeled TM4-Cx43CT. Data were acquired with 1024 complex points in the direct dimension and 256 complex points in the indirect dimension. Sweep widths were 10,000 Hz in the proton dimension and 2500 Hz in the nitrogen dimension. NMR spectra were processed using NMRPipe (38) and analyzed using NMRView (39).

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

All circular dichroism (CD) experiments were performed using an AVIV model-2055 spectrophotometer (Lakewood, NJ) fitted with a Peltier temperature control system in a 0.1 mm quartz cuvette. CD spectra were recorded for the TM4-Cx43CT (175 µM) and soluble Cx43CT (175 µM) in the exact same buffer (including 8% LPPG in the soluble Cx43CT sample) and temperature described above. Wavelengths were set from 190 to 280 nm. The response time (time constant), scan rate, and bandwidth were 1 sec, 50 nm/min, and 1.0 nm, respectively. Five scans were collected, baseline subtracted, averaged, and smoothed using an adjacent averaging window of 5. Analysis of the TM4-Cx43CT spectra was performed using the Provencher and Glockner method in the CD analysis software DICHROWEB (www.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/cdweb/html/home.html) (40,41). A normalized root mean square deviation of 0.044 was obtained from comparison of the raw and fitted data.

Results and discussion

Expression and purification of the TM4-Cx43CT

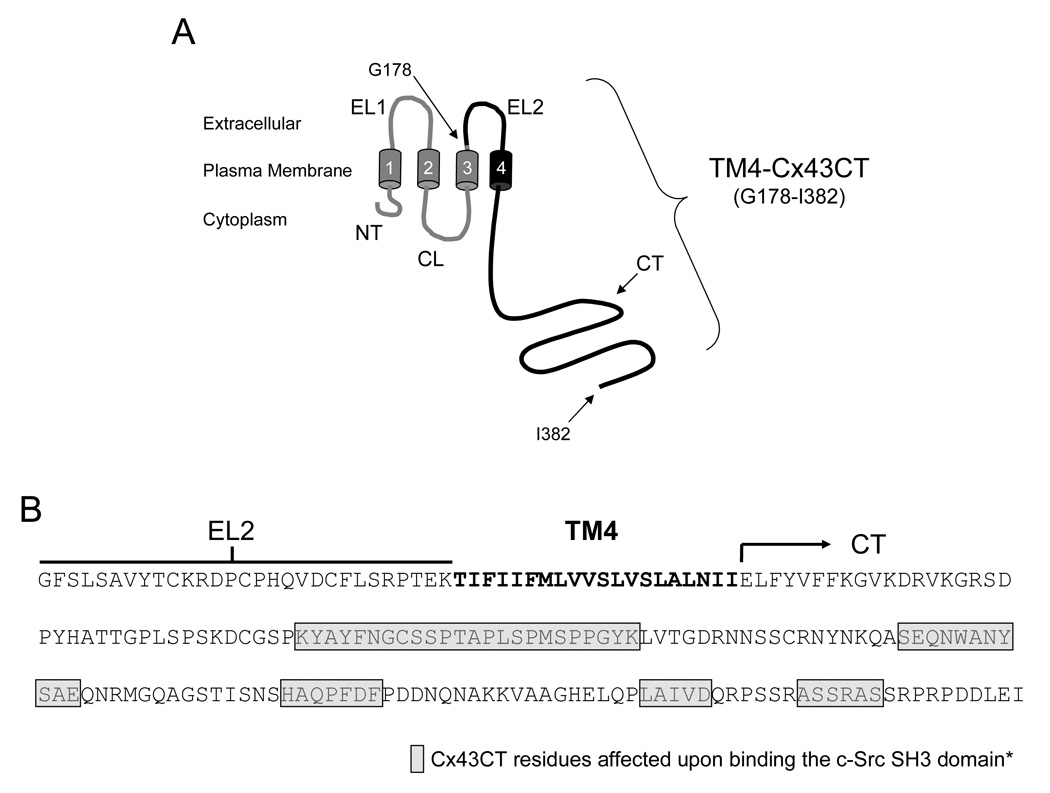

The TM4-Cx43CT was cloned into the pET-14b expression vector with the 6x His-tag at the N-terminus because previous studies have shown that C-terminal tags interfere with Cx43 molecular partner interactions and cellular distribution (42,43). An illustration of the Cx43 structure identifying the TM4-Cx43CT portion used in this study and the amino acid sequence of the TM4-Cx43CT construct has been provided in Fig. 1. Expression conditions of the TM4-Cx43CT were tested using the following four E. coli DE3 strains: BL21, Rosetta-2, C41, and C43. The C41, C43, and Rosetta-2 strains are derivatives of BL21(DE3) and were utilized for either their unique ability to express normally toxic membrane proteins (C41 and C43; (34)) or express eukaryotic proteins that contain codons rarely used in E. coli (Rosetta-2).

Fig. 1.

Model of the TM4-Cx43CT construct. A) Schematic diagram of full length Cx43. The black coloring represents the TM4-Cx43CT portion. The abbreviations are as follows: NT, N-terminus; CL, cytoplasmic loop; CT, C-terminus; EL1 and EL2, extracellular loops 1 and 2; 1–4, transmembrane segments 1–4. B) Amino acid sequence of the TM4-Cx43CT construct. The EL2 (line), TM4 (bold), and the CT (arrow) domains have been labeled. The asterisk denotes that the study used to determine the Cx43CT residues affected by the c-Src SH3 domain used a soluble version of the Cx43CT without the TM4 domain (28).

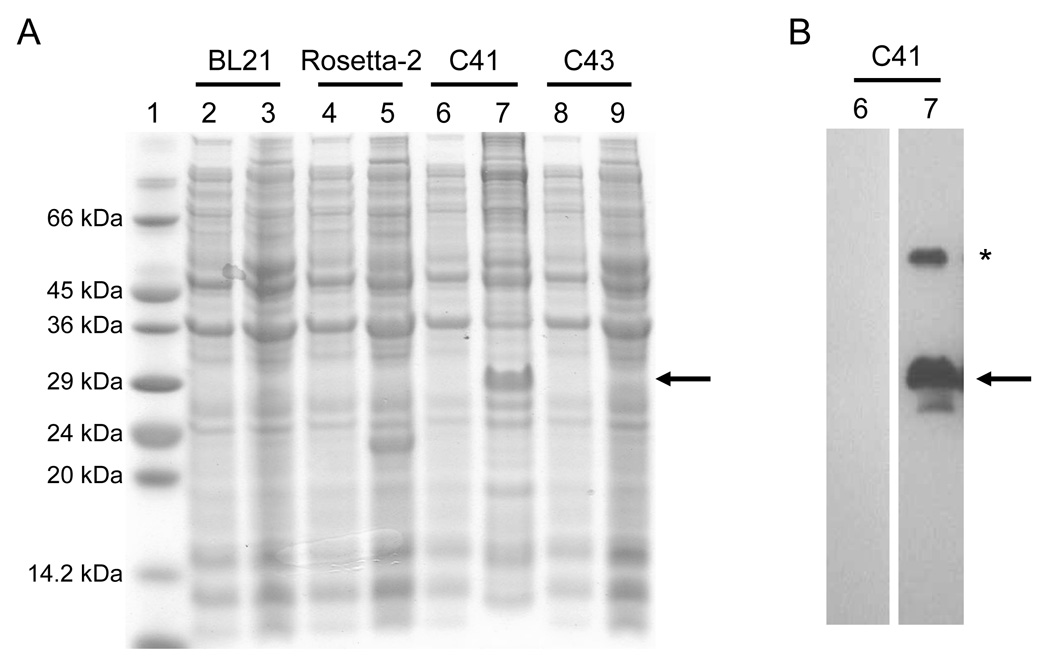

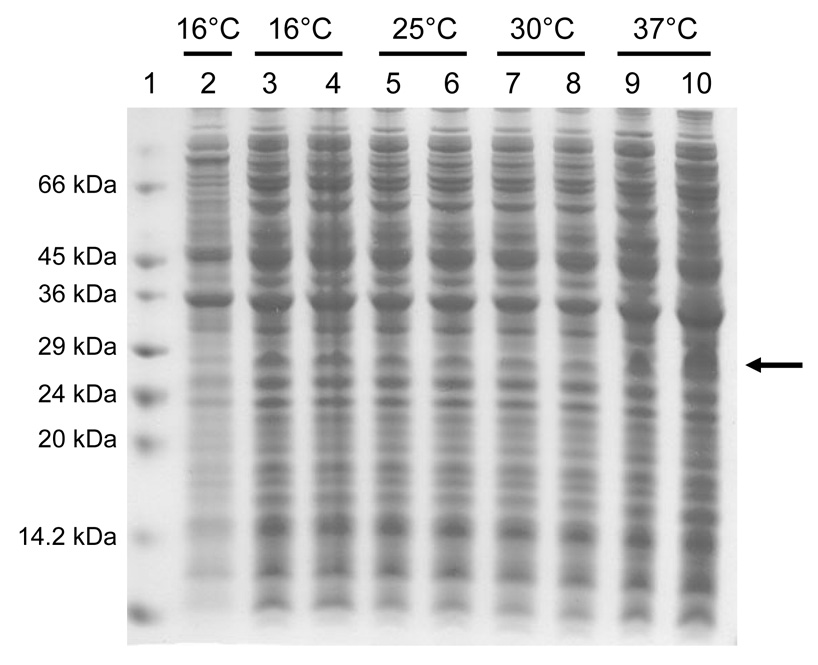

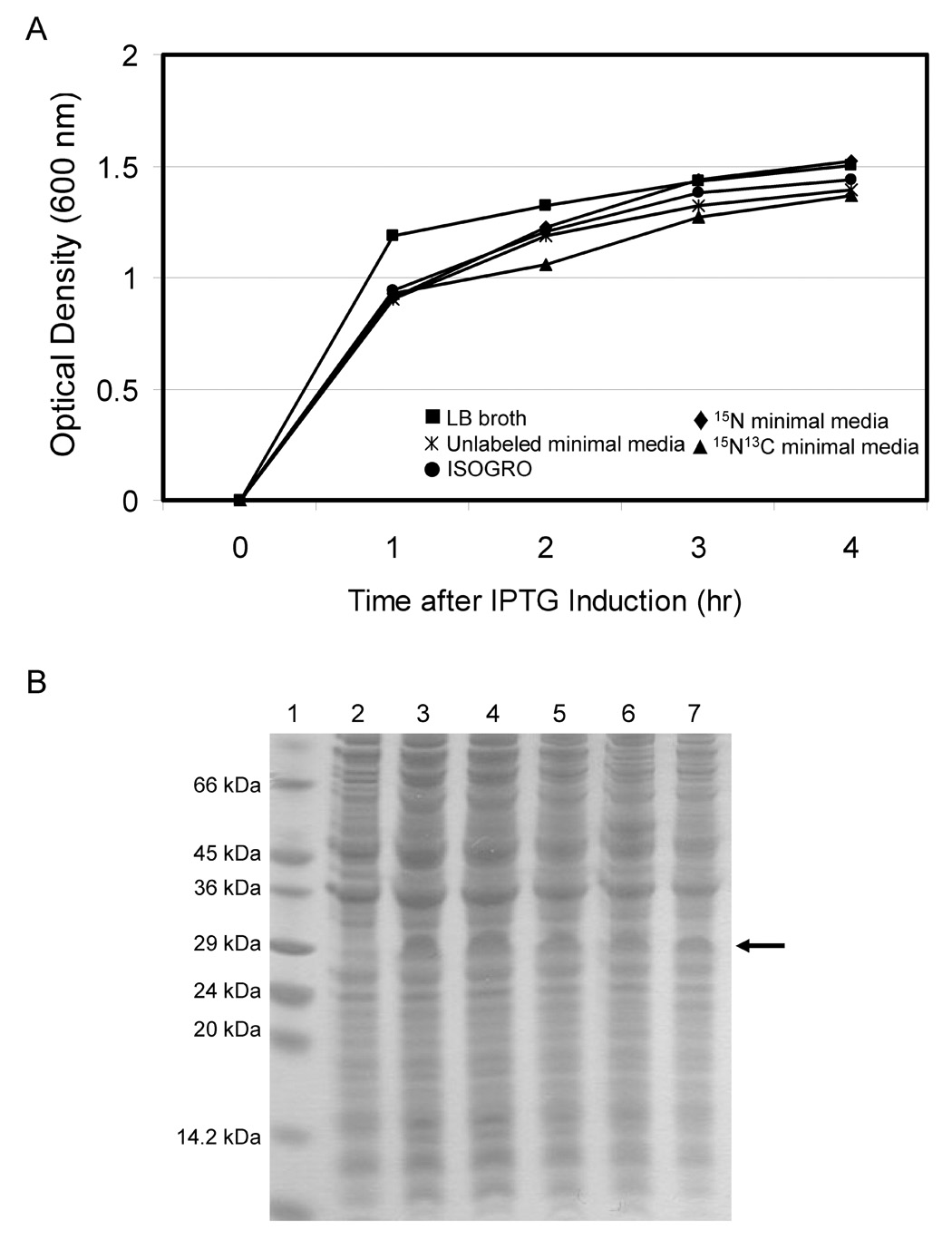

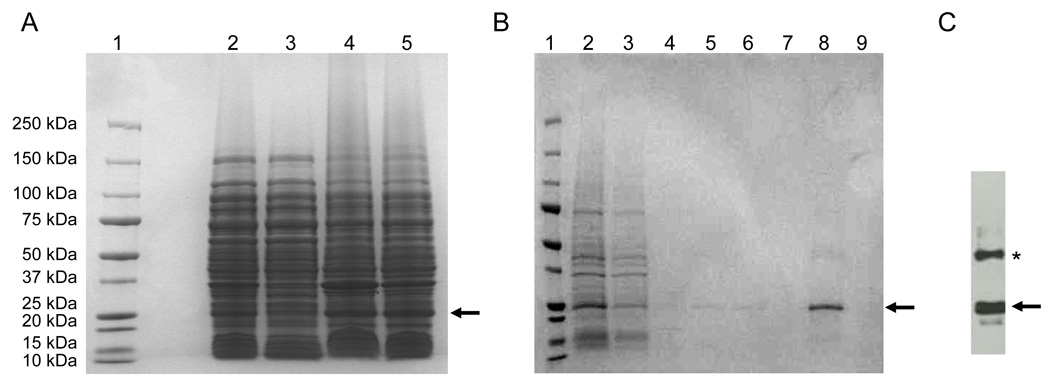

The expression profile for the 6x His-tagged TM4-Cx43CT construct is displayed in Fig. 2A. Interestingly, only the C41(DE3) bacterial strain was capable of expressing the TM4-Cx43CT. The estimated molecular weight for the TM4-Cx43CT construct is 24.9 kDa and this was confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the western blot contained a small amount of TM4-Cx43CT dimers (see * in Fig. 2B). This is consistent with previous studies which have demonstrated that the Cx43CT domain has the ability to dimerize (44). Next, we identified the optimal temperature and IPTG concentration for expression of the TM4-Cx43CT (Fig. 3). While a small amount of expression was evident at 16°C, and none at 25°C and 30°C, the only temperature capable of supporting enhanced expression was 37°C. Additionally, decreasing the levels of IPTG at 37°C correlated with a decrease in expression of the TM4-Cx43CT. Using the optimized expression conditions (i.e. E. coli C41(DE3) strain, 1 mM IPTG, at 37°C), the growth and expression of the TM4-Cx43CT in different minimal media that are necessary for NMR structural determination was tested (Fig. 4). Both the bacterial growth curves (Fig. 4A) and expression levels (Fig. 4B) indicate that the amount of TM4-Cx43CT obtained from the different minimal media is the same as the LB medium. This demonstrates the feasibility of performing NMR structural studies with purified TM4-Cx43CT. Next, the 6x His-tagged TM4-Cx43CT was purified as outlined in the ‘Materials and methods’ section. Fig. 5A illustrates the progression of the TM4-Cx43CT purification prior to the affinity chromatography step and Fig. 5B demonstrates the ability to purify the TM4-Cx43CT to homogeneity using the HisTrap HP affinity chromatography column. Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of the TM4-Cx43CT construct (Fig. 5C). Table 1 summarizes the results of the purification.

Fig. 2.

Electrophoretic profile of total cellular proteins obtained from E. coli DE3 strains BL21, Rosetta-2, C41, and C43 (labeled above each lane) expressing TM4-Cx43CT after IPTG induction for 4 hrs (panel A, lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9). Lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8 are controls (no IPTG). Lane 1 contains the protein molecular weight marker. B) The presence of the TM4-Cx43CT polypeptide was confirmed by western blot analysis using a Zymed Laboratories Inc. polyclonal anti-Cx43CT antibody. The blots correspond to lanes 6 and 7 from panel A. The arrows represent the location of the TM4-Cx43CT monomer. The asterisk represents TM4-Cx43CT dimers.

Fig. 3.

Electrophoretic profile of total cellular proteins obtained from the E. coli strain C41(DE3) expressing the TM4-Cx43CT at different temperatures (labeled above each lane) and IPTG concentrations 4 hrs after induction. Lane 2 is the control (no IPTG). Lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9 were induced with a final IPTG concentration of 0.5 mM and lanes 4, 6, 8, and 10 were induced with a final IPTG concentration of 1.0 mM. Lane 1 contains the protein molecular weight marker. The arrow represents the location of the TM4-Cx43CT.

Fig. 4.

Growth and expression profile of the TM4-Cx43CT in minimal media necessary for NMR structural studies. Growth curves (panel A) and electrophoretic profile of total cellular proteins (panel B) obtained from the E. coli strain C41(DE3) expressing the TM4-Cx43CT in different minimal media. The lanes in the SDS-PAGE gel correspond to cells grown in the following media: lane 3, ISOGRO, lane 4, 15N minimal media, lane 5, 15N13C minimal media, lane 6, Luria broth (LB), and lane 7, unlabeled minimal media. All minimal media were made as outlined in (35). Lane 1 contains the protein molecular weight marker. Lane 2 is the control, uninduced (no IPTG) cells grown in LB. The arrow represents the location of the TM4-Cx43CT.

Fig. 5.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the recombinant TM4-Cx43CT purification. A) TM4-Cx43CT purification prior to the affinity chromatography step; lane 1, protein molecular weight marker; lane 2, total cell lysate; lane 3, supernatant after 25,000 × g for 45 min spin; lane 4, pellet (inclusion bodies) after 25,000 × g for 45 min spin; lane 5, pellet solubilized in buffer containing 8 M urea. B) Purification of the TM4-Cx43CT by the HisTrap HP affinity chromatography column using an ÄKTA FPLC; lane 1, protein molecular weight marker; lane 2, sample before loading (solubilized in buffer containing 8 M urea; same as in panel A, lane 5); lane 3, flow through; lane 4, 40 mM imidazole wash; lane 5, 80 mM imidazole wash; lane 6, 100 mM imidazole wash; lane 7, 100 mM imidazole wash with 10% ethanol; lane 8, 300 mM imidazole wash; and lane 9, 500 mM imidazole wash. C) The presence of the TM4-Cx43CT polypeptide was confirmed by western blot analysis using the Zymed Laboratories Inc. polyclonal anti-Cx43CT antibody. The arrows and asterisk represent the location of the TM4-Cx43CT monomers and dimers, respectively.

Table I.

Purification of the TM4-Cx43CTa

| Step | Total Protein (mg) | TM4-Cx43CT (mg) | Purification factor | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell lysate | 1,200b | 59.2 | 1 | 100 |

| Inclusion bodyc | 67.8 | 29.5 | 8 | 50 |

| After Ni-NTA | 30.7 | 29.2 | 19 | 99 |

| After Dialysis | 25.3 | 24.8 | 20 | 85 |

Cells from 4 L culture broth were used in this preparation.

Total protein of cell lysate includes both soluble and insoluble protein.

This corresponds to the 8 M urea dissolved inclusion body obtained from 4 L cell culture.

As might be expected, along the road towards purifying the TM4-Cx43CT, attempts to improve the purification scheme were made with little success. We felt it would be of general interest to mention some of these ‘dead-end’ avenues as they may save other researcher’s time and money, but more importantly they may provide ideas for future improvements when purifying membrane bound intrinsically disordered regions. Here are a few examples: 1) we expressed the TM4-Cx43CT with a 10x His-tag (pET expression vector 19b, Novagen) under the assumption the 10x His-tag would have greater affinity for the HisTrap HP affinity chromatography column than the 6x His-tag, however, the protein expression was significantly reduced (>2-fold) in the C41(DE3) bacterial cells and the binding affinity for the HisTrap HP column was comparable to the 6x His-tag TM4-Cx43CT (data not shown), 2) the presence of the protease inhibitor cocktail was important because the disordered structure of the Cx43CT domain was highly susceptible to enzymatic cleavage, 3) all attempts to wash the inclusion bodies to remove contaminating proteins had little or no effect (e.g. high salt and/or pH, 1% Triton X-100), and 4) the use of Talon resin (Co2+) did not improve the affinity or purity of the TM4-Cx43CT as compared to the HisTrap HP resin (Ni2+).

Reconstitution of the TM4-Cx43CT in detergent micelles

Initially, dialysis was used in an attempt to remove the 8 M urea from the 1x PBS buffer (buffer condition from the final HisTrap HP affinity chromatography step), however, decreasing the urea concentration resulted in precipitation of the TM4-Cx43CT. Therefore, we optimized the precipitation process while screening the detergent solubility of the TM4-Cx43CT precipitate. As summarized in Table 2, different buffer solutions used for dialysis against the TM4-Cx43CT caused precipitation of the TM4-Cx43CT, however, the precipitations were not all the same in terms of size and texture. For example, a large fluffy white precipitation was observed when the urea concentration was lowered to 1 M and the PBS buffer was removed from the dialysis buffer, while dialysis of the TM4-Cx43CT against a buffer containing no urea and no PBS caused the precipitation to be much smaller and grainier in appearance. The precipitated TM4-Cx43CT was solubilized in a buffer solution containing 8% detergent and 20 mM MES with 50 mM NaCl (pH 5.8) because previous studies have shown this combination to provide optimal resolution and sensitivity for NMR magnets with cryoprobes [36,(45). Detergents examined included Triton X-100, n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (βOG), n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, or 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-snglycero-3-[phospho-RAC-(1-glycerol)] (LPPG) and were chosen to sample different head groups, overall net charge, and chain length. Interestingly, the only detergent able to solubilize the TM4-Cx43CT was LPPG and the only precipitate capable of being dissolved was the fluffy white precipitation from the dialysis buffer containing 1 M urea and no PBS. Solubility tests of other membrane proteins have also identified LPPG as a superior detergent in terms of membrane protein solubility, NMR spectral quality, and sample stability (36).

Table II.

Precipitation of the TM4-Cx43CT

| Buffer Solutiona | Results |

|---|---|

| 1 M urea, 1x PBSb | no precipitation |

| 0.1 M urea, 1x PBS | cloudy supernate |

| 8 M urea, no PBS | no precipitation |

| 1 M urea, no PBS | fluffy precipitation |

| no urea, no PBS | small and grainy precipitation |

All buffers contained 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM EDTA.

If the TM4-Cx43CT was further dialyzed for 12 hrs against 0.75, 0.5, 0.25, and then 0.1 M urea in 1x PBS, precipitation started to form at 0.75 M urea and continued until reaching a maximal precipitation at 0.1 M urea.

Structural analysis of the TM4-Cx43CT in detergent micelles

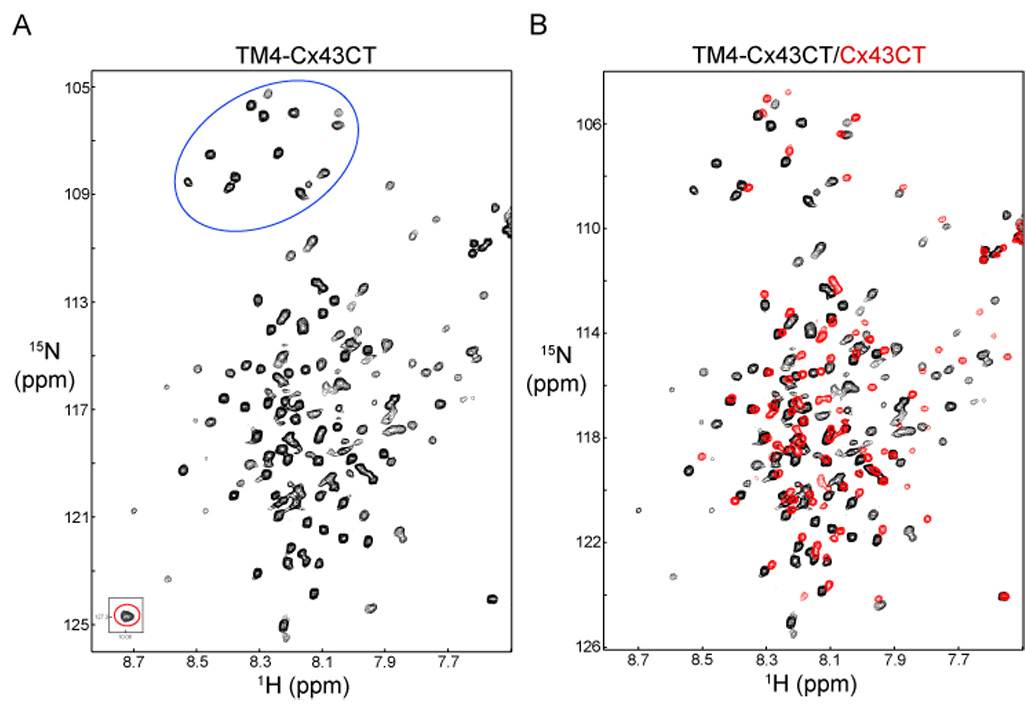

A typical NMR experiment (e.g. CBCA(CO)NH) for structural determination requires approximately 2–3 days time and in upwards of 10 different experiments need to be performed (for review see (46)). Therefore, an important parameter that needs to be determined for a new NMR sample, especially one in a lipid environment, is the stability of the signal. Towards this end, the area under the amide proton region in a 1D 1H spectrum as a function of time was used as an indicator of sample stability. The results indicate that the TM4-Cx43CT has a half-life of ~3 weeks in the LPPG micelles (data not shown). Next, 2D 15N-HSQC spectra were used to evaluate the sample properties of the TM4-Cx43CT in the LPPG micelles. The 15N-HSQC is a two dimensional NMR experiment in which each amino acid (except proline) gives one signal (or chemical shift) that corresponds to the N–H amide group. These chemical shifts are sensitive to the chemical environment, and even small changes in structure and/or dynamics can change the chemical shift of an amino acid. Fig. 6A shows that the TM4-Cx43CT is pure and contains a single conformation as indicated by the number of Trp (one, red circle) and Gly (fourteen, eleven from the TM4-Cx43CT and three from the linker, blue circle) residues in the 15N-HSQC spectrum exactly matching the number of these residues found in the TM4-Cx43CT sequence and the total expected number of amide peaks are accounted for in the spectrum. The TM4-Cx43CT spectrum was then compared in the same buffer and at the same temperature with a spectrum from a soluble version of the Cx43CT without the TM4 domain (residues S255-I382) (Fig. 6B). Overlap of the TM4-Cx43CT (black) and the soluble Cx43CT (red) spectra indicate that addition of the TM4 region downfield shifted those residues ascribed to the Cx43CT domain. Although the TM4-Cx43CT has not been assigned, the additional peaks in the TM4-Cx43CT spectrum are expected to be the result of the EL2 and TM4 residues (see Figure 1).

Fig. 6.

Demonstrating the feasibility of solving the TM4-Cx43CT structure. (A) 15N-HSQC of the TM4-Cx43CT domain in LPPG detergent micelles. Highlighted are the 14 Gly residues (blue circle) and 1 Trp side chain (red circle). (B) The control 15N-HSQC, TM4-Cx43CT alone (black), has been overlapped with a spectrum obtained from a soluble version of the Cx43CT without the TM4 domain (red).

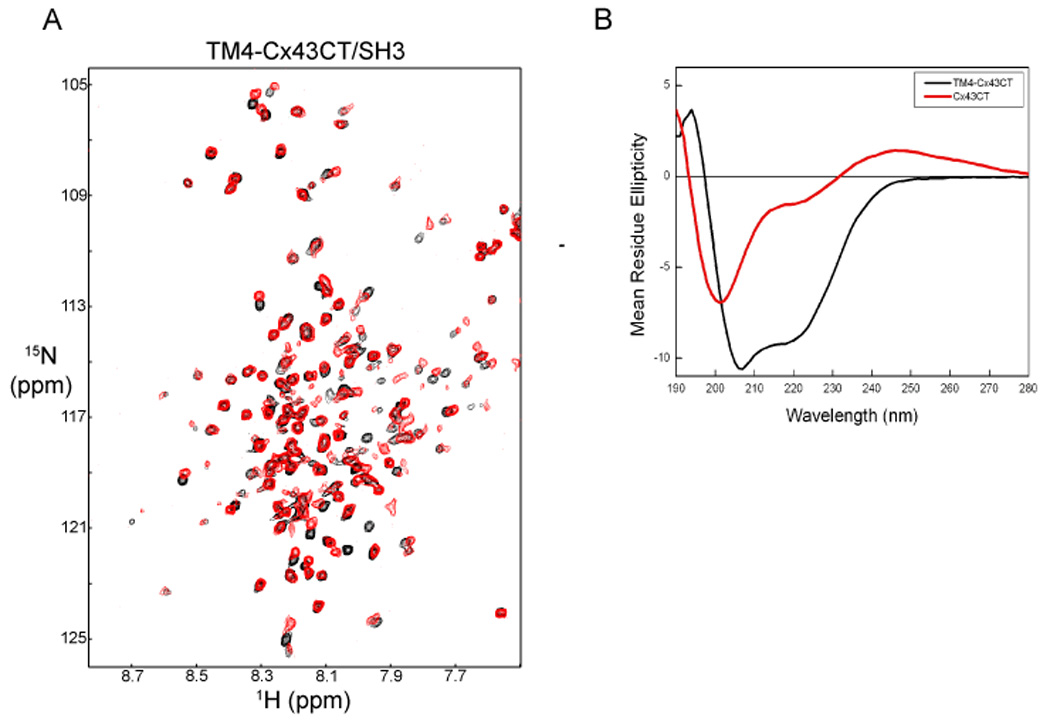

To determine if the Cx43CT portion of the TM4-Cx43CT has properly folded into a functional conformation, we tested the ability of the Cx43CT domain to associate with a known binding partner, the c-Src SH3 domain (28,47). Notice that a number of the resonance peaks obtained from TM4-Cx43CT alone (in black) did not overlap with those obtained in the presence of the c-Src SH3 domain (in red) in Fig. 7A. Shifts (red not over black) indicate a TM4-Cx43CT/SH3 association and a significant change in the TM4-Cx43CT conformation. The shifting of the TM4-Cx43CT residues in the presence of the SH3 domain indicates exchange between the free and fully bound states of TM4-Cx43CT is fast on the chemical shift timescale. When the same experiment was performed with a soluble version of the Cx43CT (residues S255-I382) without the TM4 domain, residues broadened beyond detection in the presence of the SH3 domain (exchange is intermediate on the chemical shift timescale) [28], suggesting the SH3 domain has a tighter binding affinity for the soluble Cx43CT.

Fig. 7.

Demonstrating both the TM4 (panel A) and Cx43CT (panel B) domains from the TM4-Cx43CT polypeptide are in a properly folded conformation. (A) The control 15N-HSQC, TM4-Cx43CT alone (black), has been overlapped with a spectrum obtained when the TM4-Cx43CT and c-Src SH3 domain were present at a 1:3 molar ratio (red). (B) Circular dichroism spectra of the TM4-Cx43CT and a soluble version of the Cx43CT without the TM4 domain. The spectra are represented as mean residue ellipticity. The TM4-Cx43CT and the soluble Cx43CT are labeled in the panel.

To test if the TM4 portion of the TM4-Cx43CT construct is properly folded, circular dichroism was used to evaluate if the secondary structure was α-helix as previously reported (12,48). The far-ultraviolet spectrum for the TM4-Cx43CT showed the minima characteristic of α-helices at 221 and 207 nm (Fig. 7B). The TM4-Cx43CT was then compared to the soluble version of the Cx43CT (residues S255-I382). Clearly, the soluble Cx43CT has little α-helical content in comparison to the TM4-Cx43CT, suggesting the α-helical signal is arising from the residues in the TM4 domain. This observation is consistent with previously published gap junction structures that the transmembrane domains from the connexin proteins are α-helical in structure (12,48,49). The α-helical content for the TM4-Cx43CT was determined to be 46% (see Material and Methods section). However, the predicted length of the TM4 is approximately 20 amino acids or 10% of the total number of amino acids. This suggests the α-helices extend out from the TM4 into the solution. Interestingly, the TM4-Cx43CT construct does contain a significant amount of the 2nd extracellular loop (see Fig. 1, EL2). Previous studies by Foote et al. (50) proposed a model by which the connexin extracellular domains (EL1 and EL2) form two concentric β-barrels. However, our CD data suggests there may be α-helices in these domains that are not resolvable at the resolution from the current electron crystallographic structures (12,49). Future structural studies will address the direction (i.e. towards EL2 or the CT) and length of the α-helix extending from the lipid environment.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that the Cx43CT domain attached to the 4th transmembrane domain can be purified in a properly folded conformation. In addition to enabling further characterization of this important Cx43 regulatory domain, purified TM4-Cx43CT will help address an important question; does the biophysical and structural characteristics of a soluble domain from a membrane protein have the same properties as when attached to the membrane. Additionally, the purification protocol developed for the TM4-Cx43CT will be of general use towards the better understanding of other membrane-associated intrinsically disordered domains.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Carol Kolar for her useful discussions and technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the United States Public Health Service Grant GM072631, the Nebraska Research Initiative funding for the Nebraska Center for Structural Biology, and the Eppley Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA036727.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sohl G, Willecke K. Gap junctions and the connexin protein family. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno AP, Chanson M, Elenes S, Anumonwo J, Scerri I, Gu H, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Role of the carboxyl terminal of connexin43 in transjunctional fast voltage gating. Circ Res. 2002;90:450–457. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukauskas FF, Bukauskiene A, Bennett MV, Verselis VK. Gating properties of gap junction channels assembled from connexin43 and connexin43 fused with green fluorescent protein. Biophys J. 2001;81:137–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75687-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukauskas FF, Bukauskiene A, Verselis VK. Conductance and permeability of the residual state of connexin43 gap junction channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:171–185. doi: 10.1085/jgp.119.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampe PD, Lau AF. Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:205–215. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saez JC, Nairn AC, Czernik AJ, Fishman GI, Spray DC, Hertzberg EL. Phosphorylation of connexin43 and the regulation of neonatal rat cardiac myocyte gap junctions. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2131–2145. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lampe PD, TenBroek EM, Burt JM, Kurata WE, Johnson RG, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1503–1512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis D, Stergiopoulos K, Ek-Vitorin JF, Cao FL, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Connexin diversity and gap junction regulation by pHi. Dev Genet. 1999;24:123–136. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)24:1/2<123::AID-DVG12>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stergiopoulos K, Alvarado JL, Mastroianni M, Ek-Vitorin JF, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Hetero-domain interactions as a mechanism for the regulation of connexin channels. Circ Res. 1999;84:1144–1155. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morley GE, Ek-Vitorin JF, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Structure of connexin43 and its regulation by pHi. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1997;8:939–951. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1997.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffy HS, Sorgen PL, Girvin ME, O'Donnell P, Coombs W, Taffet SM, Delmar M, Spray DC. pH-dependent intramolecular binding and structure involving Cx43 cytoplasmic domains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36706–36714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unger VM, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Yeager M. Three-dimensional structure of a recombinant gap junction membrane channel. Science. 1999;283:1176–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kardami E, Dang X, Iacobas DA, Nickel BE, Jeyaraman M, Srisakuldee W, Makazan J, Tanguy S, Spray DC. The role of connexins in controlling cell growth and gene expression. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2007;94:245–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li WE, Waldo K, Linask KL, Chen T, Wessels A, Parmacek MS, Kirby ML, Lo CW. An essential role for connexin43 gap junctions in mouse coronary artery development. Development. 2002;129:2031–2042. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffy HS, John GR, Lee SC, Brosnan CF, Spray DC. Reciprocal regulation of the junctional proteins claudin-1 and connexin43 by interleukin-1beta in primary human fetal astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLachlan E, Manias JL, Gong XQ, Lounsbury CS, Shao Q, Bernier SM, Bai D, Laird DW. Functional characterization of oculodentodigital dysplasia-associated Cx43 mutants. Cell Commun Adhes. 2005;12:279–292. doi: 10.1080/15419060500514143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unwin PN, Zampighi G. Structure of the junction between communicating cells. Nature. 1980;283:545–549. doi: 10.1038/283545a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unger VM, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Yeager M. Electron cryo-crystallography of a recombinant cardiac gap junction channel. Novartis Found Symp. 1999;219:22–30. doi: 10.1002/9780470515587.ch3. discussion 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunham B, Liu S, Taffet S, Trabka-Janik E, Delmar M, Petryshyn R, Zheng S, Perzova R, Vallano ML. Immunolocalization and expression of functional and nonfunctional cell-to-cell channels from wild-type and mutant rat heart connexin43 cDNA. Circ Res. 1992;70:1233–1243. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwak BR, Saez JC, Wilders R, Chanson M, Fishman GI, Hertzberg EL, Spray DC, Jongsma HJ. Effects of cGMP-dependent phosphorylation on rat and human connexin43 gap junction channels. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:770–778. doi: 10.1007/BF00386175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unger VM, Kumar NM, Gilula NB, Yeager M. Projection structure of a gap junction membrane channel at 7 A resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:39–43. doi: 10.1038/nsb0197-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sorgen PL, Duffy HS, Cahill SM, Coombs W, Spray DC, Delmar M, Girvin ME. Sequence-specific resonance assignment of the carboxyl terminal domain of Connexin43. J Biomol NMR. 2002;23:245–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019892719979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirst-Jensen BJ, Sahoo P, Kieken F, Delmar M, Sorgen PL. Characterization of the pH-dependent interaction between the gap junction protein connexin43 carboxyl terminus and cytoplasmic loop domains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5801–5813. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605233200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derewenda ZS. The use of recombinant methods and molecular engineering in protein crystallization. Methods. 2004;34:354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfuetzner RA, Bochkarev A, Frappier L, Edwards AM. Replication protein A. Characterization and crystallization of the DNA binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:430–434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minezaki Y, Homma K, Nishikawa K. Intrinsically disordered regions of human plasma membrane proteins preferentially occur in the cytoplasmic segment. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunker AK, Obradovic Z. The protein trinity--linking function and disorder. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:805–806. doi: 10.1038/nbt0901-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorgen PL, Duffy HS, Sahoo P, Coombs W, Delmar M, Spray DC. Structural changes in the carboxyl terminus of the gap junction protein connexin43 indicates signaling between binding domains for c-Src and zonula occludens-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54695–54701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ek-Vitorin JF, Calero G, Morley GE, Coombs W, Taffet SM, Delmar M. PH regulation of connexin43: molecular analysis of the gating particle. Biophys J. 1996;71:1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79328-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adzhubei AA, Sternberg MJ. Left-handed polyproline II helices commonly occur in globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:472–493. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson MP. The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem J. 1994;297(Pt 2):249–260. doi: 10.1042/bj2970249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Unfolded proteins and protein folding studied by NMR. Chem Rev. 2004;104:3607–3622. doi: 10.1021/cr030403s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miroux B, Walker JE. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:289–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber DJ, Gittis AG, Mullen GP, Abeygunawardana C, Lattman EE, Mildvan AS. NMR docking of a substrate into the X-ray structure of staphylococcal nuclease. Proteins. 1992;13:275–287. doi: 10.1002/prot.340130402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krueger-Koplin RD, Sorgen PL, Krueger-Koplin ST, Rivera-Torres IO, Cahill SM, Hicks DB, Grinius L, Krulwich TA, Girvin ME. An evaluation of detergents for NMR structural studies of membrane proteins. J Biomol NMR. 2004;28:43–57. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000012875.80898.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kay LE, Keifer P, Saarinen T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:10663. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson BAaB, A R. NMRView: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR. 1994;4:603–614. doi: 10.1007/BF00404272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitmore L, Wallace BA. DICHROWEB, an online server for protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W668–W673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Provencher SW, Glockner J. Estimation of globular protein secondary structure from circular dichroism. Biochemistry. 1981;20:33–37. doi: 10.1021/bi00504a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giepmans BN, Verlaan I, Moolenaar WH. Connexin-43 interactions with ZO-1 and alpha- and beta-tubulin. Cell Commun Adhes. 2001;8:219–223. doi: 10.3109/15419060109080727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunter AW, Barker RJ, Zhu C, Gourdie RG. Zonula occludens-1 alters connexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5686–5698. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorgen PL, Duffy HS, Spray DC, Delmar M. pH-Dependent Dimerization of the Carboxyl Terminal Domain of Cx43. Biophys J. 2004;87:574–581. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.039230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly AE, Ou HD, Withers R, Dotsch V. Low-conductivity buffers for high-sensitivity NMR measurements. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12013–12019. doi: 10.1021/ja026121b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, III, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR Spectroscopy. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanemitsu MY, Loo LW, Simon S, Lau AF, Eckhart W. Tyrosine phosphorylation of connexin 43 by v-Src is mediated by SH2 and SH3 domain interactions. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22824–22831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fleishman SJ, Unger VM, Yeager M, Ben-Tal N. A Calpha model for the transmembrane alpha helices of gap junction intercellular channels. Mol Cell. 2004;15:879–888. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oshima A, Tani K, Hiroaki Y, Fujiyoshi Y, Sosinsky GE. Three-dimensional structure of a human connexin26 gap junction channel reveals a plug in the vestibule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10034–10039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703704104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foote CI, Zhou L, Zhu X, Nicholson BJ. The pattern of disulfide linkages in the extracellular loop regions of connexin 32 suggests a model for the docking interface of gap junctions. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1187–1197. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]