Abstract

N-Acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) is the major immunoepitope of group A streptococcal cell wall carbohydrates. Antistreptococcal antibodies cross-reactive with anti-GlcNAc and laminin are present in sera of patients with rheumatic fever. The cross-reactivity of these antibodies with human heart valvular endothelium and the underlying basement membrane has been suggested to be a possible cause of immune-mediated valve lesion. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) encoded by the MBL2 gene, a soluble pathogen recognition receptor, has high affinity for GlcNAc. We postulated that mutations in exon 1 of the MBL2 gene associated with a deficient serum level of MBL may contribute to chronic severe aortic regurgitation (AR) of rheumatic etiology. We studied 90 patients with severe chronic AR of rheumatic etiology and 281 healthy controls (HC) for the variants of the MBL2 gene at codons 52, 54, and 57 by using a PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism-based method. We observed a significant difference in the prevalence of defective MBL2 alleles between patients with chronic severe AR and HC. Sixteen percent of patients with chronic severe AR were homozygotes or compound heterozygotes for defective MBL alleles in contrast to 5% for HC (P = 0.0022; odds ratio, 3.5 [95% confidence interval, 1.6 to 7.7]). No association was detected with the variant of the MASP2 gene. Our study suggests that MBL deficiency may contribute to the development of chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology.

Rheumatic fever (RF), which results from a nonsuppurative sequela of pharyngitis caused by group A streptococcus (GAS) in untreated genetically susceptible hosts, displays a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations including carditis, arthritis, chorea, subcutaneous nodules, and erythema marginatum (3). Arthritis occurs in 60 to 65% of patients while carditis, the most serious manifestation and one which often leads to valvular scarring, is observed in 30 to 45% of patients with RF.

The presence of antibodies and complement elements in heart and valvular tissue of patients with RF (22, 23, 25) as well as the presence of antiheart antibodies and antimyosin antibodies in the sera of patients with RF (5, 39) led to the suggestion that rheumatic carditis could be immune mediated. It has also been shown that cross-reactive human and murine monoclonal antibodies recognized N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) of GAS (30, 31). GlcNac is the immunodominant cell wall antigen of GAS and has been demonstrated to share cross-reactive epitopes with valvular tissue proteins (17) such as myosin, tropomyosin, keratin, vimentin, and laminin (1, 6, 7, 11, 24). Furthermore, an anti-GlcNAc/antimyosin monoclonal antibody from a rheumatic carditis patient was shown to be cytotoxic for human endothelial cell lines and also reacted with human valvular endothelium and the underlying basement membrane (14). These data suggested that valvular damage in patients with RF may be initially antibody mediated and may subsequently facilitate T-cell infiltration into the valves (14, 19).

Recently, it has been shown that GAS displayed strong binding to mannose-binding lectin (MBL) (27) encoded by the MBL2 gene in the chromosome region 10q11.1-q21. Circulating MBL, a C-type lectin and a member of the collectin family, is a soluble pattern recognition receptor and recognizes sugars present on the surface of a variety of pathogens. MBL plays a major role in innate immunity due to its ability to opsonize pathogens, to enhance their phagocytosis, and to activate the complement cascade via the lectin pathway (21). Activation of the complement cascade results from the association of the MBL with MBL-associated serine protease 2 (MASP2). This complex then cleaves the complement proteins C4 and C2, generating the C3 convertase C4bC2b (40) which activates C3 for the initiation of the alternative pathway and the formation of the membrane attack complex. MBL in serum is composed of four to six subunits of homotrimers of the MBL polypeptide. The complete structure of the human circulating MBL has been detailed previously (15). Inherited insufficiency of MBL that impairs the innate immune function and enhances susceptibility to infection (9) has been shown to be essentially due to three structural variants in exon 1 of the MBL2 gene at codons 52 (C to T), 54 (G to A), and 57 (G to A), corresponding, respectively, to changes of arginine to cysteine (Arg52Cys), glycine to aspartic acid (Gly54Asp), and glycine to glutamic acid (Gly57Glu) in the protein (34); these alleles have been designated, respectively, the D, B, and C alleles. These defective MBL2 mutant alleles are collectively termed the O allele, and the wild type is designated the A allele. Any of the three amino acid changes disrupts the collagen helix of the MBL molecule, and homozygosity or compound heterozygosity for any of the three alleles results in MBL deficiency. Similarly, it was reported recently that individuals harboring a mutation in the MASP2 gene which leads to an exchange of aspartic acid (GGC) for glycine (GAC) at residue 120 (Asp120Gly) have low levels of plasma MASP2, and the mutant MASP2 cannot associate with MBL to form the active MBL-MASP complex (33).

Given the key role played by MBL in innate immunity, we investigated whether the presence of MBL2 and MASP2 mutant alleles is associated with chronic severe aortic regurgitation (AR) of RF etiology. To this end we carried out a cross-sectional study including 90 patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology and 281 healthy controls (HC).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and controls.

Ninety patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology fitting the modified criteria of Spagnuolo et al. (32) were recruited at the Heart Institute (InCor), Clinical Hospital of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine. Briefly, patients had a cardiothoracic index of >0.50 in chest roentgenogram, electrocardiographic evidence of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy with a pulse pressure of ≥80 mm Hg, and diastolic arterial pressure of ≤60 mm Hg. Doppler echocardiography was performed to define the degree of AR. LV end-diastolic and LV end-systolic diameters and ejection fractions were measured by the Teichholz method. Patients with aortic stenosis or with any valvular heart disease other than AR of RF etiology and with atrial fibrillation were excluded. All AR patients had a history of rheumatic fever. The mean age of the patients was 33.6 ± 11.5 years, and 85% were male. A total of 281 consecutive, unrelated men and women admitted as the HC group were unrelated bone marrow donors excluded due to histoincompatibility.

MBL and MASP2 genotyping.

Blood samples were drawn from the patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology after they had given written informed consent, according to the Clinical Hospital Ethics Committee regulations. Genomic DNA was extracted by the DTAB/CTAB (dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide/cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) method. Polymorphisms at codons 52, 54, and 57 in exon 1 of the MBL2 gene were typed by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism using, respectively, the restriction enzymes HhaI, BanI, and MboII. The following pair of primers flanking the three polymorphisms was used: MBLex1F, 5′-CAT CAA CGG CTT CCC AGG CAA AGA TGC G-3′; and MBLex1R, 5′-CAG GCA GTT TCC TCT GGA AGG TAA AG-3′. Primer MBLex1R was specifically designed with a G → C change (underlined) to create an HhaI restriction site to discriminate the codon 52 sequence variation. PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 μl containing 1 μl of genomic DNA (50 ng), 1.5 mM MgCl2, a 0.25 pM concentration of forward and reverse primers (each), a 40 μM concentration of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 2 U of Taq polymerase in buffer containing 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) and 500 mM KCl. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 62°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The PCR was followed by a final step at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR product is 119 bp. The PCR product is cleaved into 28 and 91 bp by HhaI for the A allele and is uncleaved when the D variant is present due to the replacement of cytosine with thymine. For codon 54, the B variant is not digested by BanI while the A allele gives fragments of 35 and 84 bp. For codon 57, the C variant yields two fragments of 56 and 63 bp with MboII while the A allele remains uncut. PCR restriction fragments were size separated by electrophoresis on 12% polyacrylamide gels.

For the MASP2 polymorphism, the following pair of primers flanking the polymorphism was used to generate a PCR product of 197 bp: MASP2F, 5′-GCG AGT ACG ACT TCG TCA AGG-3′; and MASP2R, 5′-CTC GGC TGC ATA GAA GGC-3′. In the presence of guanine (codon GGC for Asp), two fragments of 142 bp and 55 bp were obtained by the restriction endonuclease MspI. The PCR product remained uncleaved in the presence of adenine (codon GAC for Gly). PCR restriction fragments were size separated on a 3% agarose gel.

Serum cytokine and MBL measurements.

Blood was collected in EDTA tubes and kept on ice immediately. Within 15 min, samples were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm at 4°C for 15 min, and plasma was collected and kept at −80°C until analysis. Cytokines were measured by using commercially available kits (Immulite, Diagnostic Products Corp.) for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) and by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Quantikine; R&D Systems,) for soluble TNF-α receptors type 1 and 2 (sTNFRI and sTNFRII), IL-6 soluble receptor, and IL-1 receptor antagonist. The concentration of MBL in plasma was determined by a sandwich enzyme immunoassay using another kit (Antibody Shop, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism, version 4.0, software. Genotype and allele frequencies were calculated by gene counting. Comparison of allele and genotype frequency between groups was done by Fisher's exact two-tailed analysis. Genotype distribution was analyzed by comparing the observed number of a given genotype with the number expected under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The serum concentration of cytokines and MBL concentration are expressed as means ± standard deviations; the differences in mean values of cytokines and MBL according to the MBL2 genotypes were analyzed by analysis of variance, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was applied with multiple comparisons with the Dunn's test.

RESULTS

Allele and genotype distributions for both MASP2 and MBL2 were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in both patients and HC. The distributions of genotype and allele frequencies for the three structural variants in exon 1 of the MBL2 gene are shown in Table 1. The frequency of the D allele was higher among patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology than in the HC (11% versus 4%) and was statistically significant (P = 0.0025; odds ratio [OR], 2.8 [range, 1.5 to 5.2]). The frequencies of B and C alleles were similar in both groups. The frequencies of the O/O homozygotes were significantly different between patients and controls (16% versus 5%; P = 0.0022; OR, 3.5 [1.6 to 7.7]), whereas the frequencies of the A/O heterozygotes were similar in both groups.

TABLE 1.

Genotype and allele frequencies of MASP2 and MBL alleles in chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology and HC

| Genotype and allele(s)a | No. and frequency (%) of genotype or alleleb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| AR (n = 90) | HC (n = 281) | |

| MASP2 | ||

| D120D | 87 (97) | 269 (96) |

| D120G | 3 (3) | 12 (4) |

| G120G | 0 | 0 |

| Allele | ||

| D120 | 177 (98) | 550 (98) |

| G120 | 3 (2) | 12 (2) |

| MBL2 (A/D) | ||

| A/A | 72 (80) | 259 (92.1) |

| A/D | 17 (19) | 21 (7.5) |

| D/D | 1 (1) | 1 (.4) |

| Allele | ||

| D | 19 (11) | 23 (4)c |

| A | 161 (89) | 539 (96) |

| MBL2 (A/B) | ||

| A/A | 61 (68) | 210 (75) |

| A/B | 27 (30) | 64 (23) |

| B/B | 2 (2) | 7 (2) |

| Allele | ||

| B | 31 (17) | 78 (14) |

| A | 149 (83) | 484 (86) |

| MBL2 (A/C) | ||

| A/A | 82 (91) | 262 (93) |

| A/C | 8 (9) | 19 (7) |

| Allele | ||

| C | 8 (4) | 19 (3) |

| A | 172 (96) | 543 (97) |

| MBL2 (A/O) | ||

| A/A | 46 (51) | 176 (63) |

| A/O | 30 (33) | 91 (32) |

| O/O | 14 (16) | 14 (5)d |

| Allele | ||

| O | 58 (32) | 119 (21)e |

| A | 122 (68) | 443 (79) |

Mutations related to MBL2 are as follows: A/D, Arg52Cys; A/B, Gly54Asp; and A/C, Gly57Glu.

n, number of subjects.

P = 0.0025 (OR, 2.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5 to 5.2) for AR versus HC.

P = 0.0022 (OR, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.6 to 7.7) for O/O versus A/A plus A/O genotypes.

P = 0.0035 (OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.6) for AR versus HC.

To determine whether the defective MBL2 alleles have any influence on the severity of disease, we stratified the patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class. Fifty-four patients with AR were classified as NYHA functional class I/II, and 36 were NYHA class III/IV. As shown in Table 2, there was no statistical difference between the two groups despite a higher frequency of carriers of a variant MBL allele among patients with AR in the NYHA class I/II group (57% versus 36%). Borderline significance was reached at allele comparison.

TABLE 2.

Genotype and allele frequencies in patients with severe chronic AR of rheumatic etiology stratified according to the NYHA functional class

| MBL | No. and frequency (%) of genotype or allelea

|

|

|---|---|---|

| NYHA class I/II (n = 54) | NYHA class III/IV (n = 46) | |

| Genotype | ||

| A/A | 23 (43) | 23 (64) |

| A/O | 20 (37) | 10 (28) |

| O/O | 11 (20) | 3 (8) |

| Allele | ||

| A | 66 (61) | 56 (78) |

| O | 42 (39) | 16 (22) |

P was 0.02 for the presence of the A allele in the class I/II group versus the class III/IV group (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.88). Other differences were not significant. n, number of subjects.

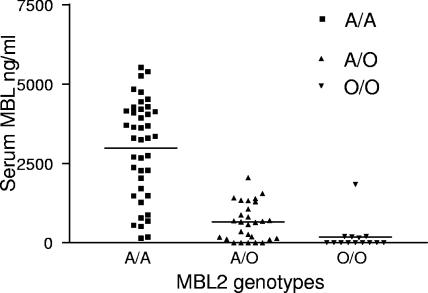

We analyzed the relationship between MBL2 genotypes and plasma levels of MBL in 83 patients as shown in Fig. 1. Subjects homozygous for the A allele had a higher level of MBL (mean, 2,985 ± 1,545 ng/ml; median, 3,290 ng/ml) than heterozygous subjects (mean, 655 ± 581 ng/ml; median, 648.5 ng/ml; P < 0.001 by Dunn's multiple comparison test) and than subjects homozygous for the mutant MBL O allele (mean, 183 ± 482 ng/ml; median, 0 ng/ml; P < 0.001). Comparison by a Kruskal-Wallis test also showed the distribution to be highly significant (P = 0.0001).

FIG. 1.

MBL plasma levels according to MBL A/O genotypes. MBL levels were detected in the plasma by a sandwich enzyme immunoassay (Antibody Shop, Copenhagen, Denmark). The cutoff for the assay was 50 ng/ml.

Regarding MASP2 polymorphism, as shown in Table 1, we observed no difference between the patients with AR and the HC. There were only 3 and 12 individuals heterozygous for the mutation among the patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology and the HC, respectively, indicating an allele frequency of 2% in both groups. Only two and six individuals were also heterozygous for the defective MBL2 alleles among the patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology and HC, respectively.

We evaluated whether the presence of defective MBL2 alleles would be associated with differences in disease progression as shown in Table 3. Disease-related phenotypes did not reveal any significant association according to MBL genotype except for the aortic root diameter. Individuals with the AA genotype tended to have higher aortic diameters than individuals with the O allele.

TABLE 3.

Disease characteristics according to MBL A/O genotype

| Parametera | Value for group according to genotype (SD)

|

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/A | A/O | O/O | ||

| No. of subjects | 46 | 30 | 14 | |

| Age (yr) | 33.6 (12.0) | 32.4 (11.6) | 35.6 (10.6) | 0.35 |

| Presence of LV dysfunction (%) | 24.4 | 10.3 | 21.4 | 0.32 |

| Septum thickness (mm) | 10.4 (1.8) | 10.3 (1.3) | 9.9 (1.1) | 0.66 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 71.6 (8.9) | 71.9 (8.9) | 70.7 (5.3) | 0.91 |

| LVESD (mm) | 50.8 (10.0) | 49.7 (9.1) | 48.5 (5.9) | 0.69 |

| LVEF (%) | 63 (10) | 66 (10) | 66 (10) | 0.43 |

| Aortic diam (mm) | 39.4 (5.8) | 35.4 (7.5) | 37.6 (4.7) | 0.01 |

| Left atrium (mm) | 39.2 (4.9) | 39.3 (8.2) | 40.2 (6.0) | 0.86 |

| Ventricular mass (g) | 238.2 (79.2) | 229.6 (71.4) | 219.3 (49.7) | 0.69 |

LVEDD, LV end-diastolic diameter; LVESD, LV end-systolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

In addition, we studied the cytokine profile of AR patients according to MBL2 genotype (Table 4) and found no association between any of the assayed cytokines and the MBL2 genotype.

TABLE 4.

Cytokine profiles according to MBL genotype in patients with severe chronic AR of rheumatic etiology

| Cytokinea | Level of expression by genotype (SD)b

|

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/A | A/O | O/O | ||

| IL-6 | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.11 |

| TNF-α | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.6) | 0.47 |

| sTNFR1 | 2.9 (0.2) | 3.0 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.2) | 0.24 |

| sTNFR2 | 3.3 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.2) | 0.39 |

| IL-6R | 4.5 (0.1) | 4.6 (0.1) | 4.4 (0.1) | 0.19 |

| IL-1RA | 2.0 (0.4) | 2.7 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.7) | 0.10 |

IL-6R, IL-6 receptor; IL-1RA, IL-1 receptor antagonist.

Cytokine levels were log transformed due to the skewness of their distribution.

DISCUSSION

Our data provide evidence for the first time that a homozygote or compound heterozygote for the defective MBL2 alleles in exon 1 of the gene is associated with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology. MBL, an important component of the complement system, plays a key role in innate immunity. As the main role of innate immunity is to restrict the multiplication of infectious agents, deficiency in one of the genes involved in innate immunity may delay or impair the clearance of the pathogens, and persistence of the pathogens may trigger the immune system response. Indeed, subjects who are homozygous or compound heterozygous for defective MBL2 alleles or who have low serum MBL suffer from recurrent bacterial and viral infections as children (38), and a subset of them have enhanced risk for autoimmune disorders (36).

The autoimmune response can conceptually be considered as unusual exposure to a self-antigen or to an external antigenic epitope that cross-reacts with a self-antigen (molecular mimicry). In the setting of rheumatic disorders, several lines of evidence indicate that rheumatic fever/rheumatic heart disease is a postinfection autoimmune disorder (20). Indeed, enhanced antistreptococcal antibody response against GAS carbohydrate antigen, in particular, against GlcNAc (17), has been reported to persist in patients with RF with valvular heart disease (8). Autopsy studies have shown deposits of antibodies in valvular tissue of patients with rheumatic fever (23). Of particular interest is the demonstrated immune relationship between GAS polysaccharide and the structural glycoprotein of heart valve tissue (17). Further confirmation of such a link is provided by the observation that removal of inflamed valves in patients results in a significant decrease in the levels of anti-group A carbohydrate antibodies in the serum (2). Evidence of molecular mimicry between M5 GAS protein and cardiac proteins of patients with rheumatic heart disease has also been demonstrated (10).

Given these facts, we reasoned that MBL deficiency could impair innate immunity, with a consequent autoimmune response against cardiac proteins due to sustained exposure to GAS antigens in patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology. Around 49% of our patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology had at least one defective MBL2 allele compared to only 37% of HC. In addition, we showed that patients homozygous or compound heterozygous for defective MBL2 alleles (genotype O/O) were at higher risk of developing chronic severe AR.

Our data on chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology are in direct contradiction with an earlier report wherein the MBL2 wild-type allele was associated with mitral valve lesion of rheumatic etiology (26), but our findings are in line with the results of a recent study where mutant O genotypes were associated with heart valve lesions among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (12). The discrepancies between our study and that of Messias Reason et al. lie in the fact that all our patients have aortic valvular lesion while those of Messias Reason et al. (26) had mitral valve lesions; in addition our patients and HC are of mixed Brazilian ethnicity in contrast to those of Messias Reason et al. (26), who were Brazilian Caucasians. However, several studies have shown that a homozygote or compound heterozygote for the MBL mutant O alleles is associated with recurrent infections and autoimmune diseases (16, 18, 28, 35). MBL mediates the opsonophagocytosis of microorganisms. The host defense against GAS infection is mediated by phagocytosis and killing by polymorphonuclear cells and complement lysis (4). Although the association of the MBL2 variants with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology is compelling due to its biological function, we cannot exclude the possibility that these variants are in linkage disequilibrium with variants in a nearby causative gene. Also, the association of the homozygote or compound heterozygote for the MBL2 defective alleles in exon 1 of the gene with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology is not absolute and, thus, is not sufficient per se to explain the disease, as it occurs in only a subset of patients. It is most probable that the defective MBL2 O allele is one of several other predisposing risk factors. It is likely to act in synergy with other factors, both genetic and environmental, in the development of the disease.

With respect to the polymorphism in the MASP2 gene, there was no association with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology. Individuals homozygous for the mutation Asp120Gly are reported to have no MBL pathway activity (33) while there is no impairment of this pathway among heterozygous individuals (37). We did not observe any individuals homozygous for this mutation. This reinforced the association of patients with chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology with defective MBL2 alleles.

MBL is reported to suppress proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α and IL-1β and to increase IL-10, IL-1R antagonist, MCP-1, and IL-6 produced by monocytes following lipopolysaccharide stimulation in vitro (13). We did not find any association between defective MBL2 alleles and either disease progression or cytokine profiles in our population. However, it is interesting that no tendency of increased disease severity in the presence of defective alleles was apparent. It is our interpretation that harboring defective MBL2 alleles is a risk factor for the autoimmune response allegedly associated with development of rheumatic heart disease. Insufficiency of MBL in the serum has been reported to hamper the clearance of the immune complex, leading to impairment of the overall immune reaction (29). Hence, it is tempting to speculate that MBL deficiency leads to delayed clearance of apoptotic cell-derived self-antigen and thus to longer exposure to self-antigen. Molecular mimicry between M5 streptococcal protein and cardiac proteins of patients with rheumatic heart disease has been shown (10). Once this response has already occurred, the presence of a particular genotype in this locus does not seem to account for an increased risk of ventricular remodeling or of heart failure development.

Altogether, our results show that defective MBL2 alleles contribute to chronic severe AR of rheumatic etiology. Further studies should address whether valvular lesions of rheumatic etiology are associated with MBL2 genetic markers in other populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Fundacão de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnologico.”

We have no financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antone, S. M., E. E. Adderson, N. M. Mertens, and M. W. Cunningham. 1997. Molecular analysis of V gene sequences encoding cytotoxic anti-streptococcal/anti-myosin monoclonal antibody 36.2.2 that recognizes the heart cell surface protein laminin. J. Immunol. 159:5422-5430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayoub, E. M., A. Taranta, and T. D. Bartley. 1974. Effect of valvular surgery on antibody to the group A streptococcal carbohydrate. Circulation 50:144-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisno, A. L. 2000. Nonsuppurative poststreptococcal sequelae: rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis, p. 1799-1810. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Churchill Livingstone, New York, NY.

- 4.Bisno, A. L., M. O. Brito, and C. M. Collins. 2003. Molecular basis of group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham, M. W., J. M. McCormack, L. R. Talaber, J. B. Harley, E. M. Ayoub, R. S. Muneer, L. T. Chun, and D. V. Reddy. 1988. Human monoclonal antibodies reactive with antigens of the group A Streptococcus and human heart. J. Immunol. 141:2760-2766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham, M. W., N. K. Hall, K. K. Krisher, and A. M. Spanier. 1986. A study of anti-group A streptococcal monoclonal antibodies cross-reactive with myosin. J. Immunol. 136:293-298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale, J. B., and E. H. Beachey. 1985. Multiple, heart-cross-reactive epitopes of streptococcal M proteins. J. Exp. Med. 161:113-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudding, B. A., and E. M. Ayoub. 1968. Persistence of streptococcal group A antibody in patients with rheumatic valvular disease. J. Exp. Med. 128:1081-1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisen, D. P., and R. M. Minchinton. 2003. Impact of mannose-binding lectin on susceptibility to infectious diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:1496-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fae, K. C., D. D. da Silva, S. E. Oshiro, A. C. Tanaka, P. M. Pomerantzeff, C. Douay, D. Charron, A. Toubert, M. W. Cunningham, J. Kalil, and L. Guilherme. 2006. Mimicry in recognition of cardiac myosin peptides by heart-intralesional T cell clones from rheumatic heart disease. J. Immunol. 176:5662-5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenderson, P. G., V. A. Fischetti, and M. W. Cunningham. 1989. Tropomyosin shares immunologic epitopes with group A streptococcal M proteins. J. Immunol. 142:2475-2481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Font, J., M. Ramos-Casals, P. Brito-Zeron, N. Nardi, A. Ibanez, B. Suarez, S. Jimenez, D. Tassies, A. Garcia-Criado, E. Ros, J. Sentis, J. C. Reverter, and F. Lozano. 2007. Association of mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms with antiphospholipid syndrome, cardiovascular disease and chronic damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser, D. A., S. S. Bohlson, N. Jasinskiene, N. Rawal, G. Palmarini, S. Ruiz, R. Rochford, and A. J. Tenner. 2006. C1q and MBL, components of the innate immune system, influence monocyte cytokine expression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 80:107-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galvin, J. E., M. E. Hemric, K. Ward, and M. W. Cunningham. 2000. Cytotoxic mAb from rheumatic carditis recognizes heart valves and laminin. J. Clin. Investig. 106:217-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garred, P., F. Larsen, J. Seyfarth, R. Fujita, and H. O. Madsen. 2006. Mannose-binding lectin and its genetic variants. Genes Immun. 7:85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garred, P., H. O. Madsen, U. Balslev, B. Hofmann, C. Pedersen, J. Gerstoft, and A. Svejgaard. 1997. Susceptibility to HIV infection and progression of AIDS in relation to variant alleles of mannose-binding lectin. Lancet 349:236-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein, I., B. Halpern, and L. Robert. 1967. Immunological relationship between streptococcus A polysaccharide and the structural glycoprotein of heart valve. Nature 213:44-47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graudal, N. A., H. O. Madsen, U. Tarp, A. Svejgaard, G. Jurik, H. K. Graudal, and P. Garred. 2000. The association of variant mannose-binding lectin genotypes with radiographic outcome in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 43:515-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guilherme, L., E. Cunha-Neto, V. Coelho, R. Snitcowsky, P. M. A. Pomerantzeff, R. V. Assis, F. Pedra, J. Neumann, A. Goldberg, M. E. Patarroyo, F. Pileggi, and J. Kalil. 1995. Human heart-infiltrating T-cell clones from rheumatic heart disease patients recognize both streptococcal and cardiac proteins. Circulation 92:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilherme, L., K. Faé, S. E. Oshiro, and J. Kalil. 2005. Molecular pathogenesis of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 7:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jack, D. L., N. J. Klein, and M. W. Turner. 2001. Mannose-binding lectin: targeting the microbial world for complement attack and opsonophagocytosis. Immunol. Rev. 180:86-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan, M. H., and F. D. Dallenbach. 1960. Immunologic studies of heart. III. Occurrence of bound gamma globulin in auricular appendages from rheumatic hearts. Relationship to certain histopathic features of rheumatic heart disease. J. Exp. Med. 113:1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaplan, M. H., R. Bolande, L. Rakita, and J. Blair. 1964. Presence of bound immunoglobulins and complement in the myocardium in acute rheumatic fever. Association with cardiac failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 271:637-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraus, W., J. M. Seyer, and E. H. Beachey. 1989. Vimentin-cross-reactive epitope of type 12 streptococcal M protein. Infect. Immun. 57:2457-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lannigan, R., and S. A. Zaki. 1968. Location of gamma globulin in the endocardium in rheumatic heart disease by the ferritin-labelled antibody technique. Nature 217:173-174. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messias Reason, I. J., M. D. Schafranski, J. C. Jensenius, and R. Steffensen. 2006. The association between mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism and rheumatic heart disease. Hum. Immunol. 67:991-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neth, O., D. L. Jack, A. W. Dodds, H. Holzel, N. J. Klein, and M. W. Turner. 2000. Mannose-binding lectin binds to a range of clinically relevant microorganisms and promotes complement deposition. Infect. Immun. 68:688-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Øhlenschlaeger, T., P. Garred, H. O. Madsen, and S. Jacobsen. 2004. Mannose-binding lectin variant alleles and the risk of arterial thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:260-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saevarsdottir, S., T. Vikingsdottir, and H. Valdimarsson. 2004. The potential role of mannan-binding lectin in the clearance of self-components including immune complexes. Scand. J. Immunol. 60:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shikhman, A. R., N. S. Greenspan, and M. W. Cunningham. 1993. A subset of mouse monoclonal antibodies cross-reactive with cytoskeletal proteins and group A streptococcal M proteins recognizes N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosamine. J. Immunol. 151:3902-3913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shikhman, A. R., N. S. Greenspan, and M. W. Cunningham. 1994. Cytokeratin peptide SFGSGFGGGY mimics N-acetyl-beta-d-glucosamine in reaction with antibodies and lectins, and induces in vivo anti-carbohydrate antibody response. J. Immunol. 153:5593-5606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spagnuolo, M., H. Kloth, A. Taranta, E. Doyle, and B. Pasternack. 1971. Natural history of rheumatic aortic regurgitation. Criteria predictive of death, congestive heart failure, and angina in young patients. Circulation 44:368-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stengaard-Pedersen, K., S. Thiel, M. Gadjeva, M. Møller-Kristensen, R. Sørensen, L. T. Jensen, A. G. Sjöholm, L. Fugger, and J. C. Jensenius. 2003. Inherited deficiency of mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease 2. N. Engl. J. Med. 349:554-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sumiya, M., M. Super, P. Tabona, R. J. Levinsky, T. Arai, M. W. Turner, and J. A. Summerfield. 1991. Molecular basis of opsonic defect in immunodeficient children. Lancet 337:1569-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summerfield, J. A., S. Ryder, M. Sumiya, M. Thursz, A. Gorchein, M. A. Monteil, and M. W. Turner. 1995. Mannose binding protein gene mutations associated with unusual and severe infections in adults. Lancet 345:886-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiel, S., P. D. Frederiksen, and J. C. Jensenius. 2006. Clinical manifestations of mannan-binding lectin deficiency. Mol. Immunol. 43:86-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiel, S., R. Steffensen, I. J. Christensen, W. K. Ip, Y. L. Lau, I. J. Reason, H. Eiberg, M. Gadjeva, M. Ruseva, and J. C. Jensenius. 2007. Deficiency of mannan-binding lectin associated serine protease-2 due to missense polymorphisms. Genes Immun. 8:154-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner, M. W., and R. M. Hamvas. 2000. Mannose-binding lectin: structure, function, genetics and disease associations. Rev. Immunogenet. 2:305-322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Rijn, I., J. B. Zabriskie, and M. McCarty. 1977. Group A streptococcal antigens cross-reactive with myocardium. Purification of heart-reactive antibody and isolation and characterization of the streptococcal antigen. J. Exp. Med. 146:579-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vorup-Jensen, T., S. V. Petersen, A. G. Hansen, K. Poulsen, W. Schwaeble, R. B. Sim, K. B. Reid, S. J. Davis, S. Thiel, and J. C. Jensenius. 2000. Distinct pathways of mannan-binding lectin (MBL)- and C1-complex autoactivation revealed by reconstitution of MBL with MBL-associated serine protease-2. J. Immunol. 165:2093-2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]