Abstract

Comparative genomics has identified several regions of difference (RDs) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that are deleted or absent in Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccines. To determine their relevance for diagnostic and vaccine applications, it is imperative that efficient methods are developed to test the encoded proteins for immunological reactivity. In this study, we have used 220 synthetic peptides covering sequences of 12 open reading frames (ORFs) of RD1 and tested them as a single pool (RD1pool) with peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained from pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) patients and M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in Th1 cell assays that measure antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion. The results showed that RD1pool induced strong responses in both TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. The subsequent testing of peptide pools of individual ORFs revealed that all ORFs induced positive responses in a portion of donors, but PPE68, CFP10, and ESAT6 induced strong responses in TB patients and PPE68 induced strong responses in BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. In addition, HLA-DR and -DQ typing of donors and HLA-DR binding prediction analysis of proteins suggested HLA-promiscuous presentation of PPE68, CFP10, and ESAT6. Further testing of individual peptides showed that a single peptide of PPE68 (121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145) was immunodominant. The search for sequence homology revealed that a part of this peptide, 124-ATNFFGINTIPIAL-137, was present in several PPE family proteins of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG vaccines. Further experiments limited the promiscuous and immunodominant epitope region to the 10-amino-acid cross-reactive sequence 127-FFGINTIPIA-136.

Tuberculosis (TB) is among the most important diseases of worldwide distribution with respect to both morbidity and mortality. Annually, TB afflicts about 9 million people with 2 million deaths (18). The rapid spread of TB in developing countries of Africa and Asia is accelerated by the human immunodeficiency virus epidemic and the spread of multi- and extra-drug-resistant TB (46). To protect against TB, vaccination with Mycobacterium bovis BCG has been used for more than 70 years, but its efficacy varies tremendously in different parts of the world (49). In addition, the diagnostic value of the presently used skin test reagent, the purified protein derivative (PPD) of M. tuberculosis, is low due to cross-reactivity with environmental mycobacteria and the vaccine strains of M. bovis BCG (14). Furthermore, vaccination with M. bovis BCG is contraindicated in immunocompromised subjects, including AIDS patients who are usually at a very high risk of developing TB (19). Identification of M. tuberculosis antigens useful for diagnosis and development of new vaccines is therefore an important goal in TB research.

The protection against TB requires cellular immune responses mediated by T helper 1 (Th1)-type cells that secrete large quantities of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (2, 13, 15), and therefore a primary criterion for selecting candidate antigens for vaccine design has been their ability to induce IFN-γ responses (reviewed in reference 27). M. tuberculosis is rich in antigens that induce IFN-γ secretion, and the presence of such antigens has been reported in purified cell walls, the cytosolic fraction, and short-term culture filtrates (ST-CF) (reviewed in reference 25). However, several studies have suggested that antigens present in ST-CF are the primary inducers of IFN-γ secretion and provide protection against TB in mice and guinea pigs (reviewed in reference 26). It has been previously shown that two M. tuberculosis-specific antigens present in ST-CF, i.e., ESAT6 and CFP10, are frequently recognized by human Th1 cells after natural infection and therefore are important in the specific diagnosis of active and latent TB (29, 31, 47). Interestingly, ESAT6 and CFP10, when tested together in IFN-γ assays, have been shown to improve the diagnostic efficacy of TB compared to results with each antigen separately (20). In addition, vaccination with ESAT6 and CFP10 has been shown to provide protection against challenge with M. tuberculosis in animal models of TB (50). However, ESAT6 and CFP10 can be used either as vaccines or as diagnostic reagents but not as both. This necessitates the identification of additional M. tuberculosis antigens, some of which could be reserved for diagnosis and others for the development of new vaccines against TB.

The analysis of the M. tuberculosis genome sequence has shown that genes encoding ESAT6 and CFP10 are located in region of difference 1 (RD1) that is deleted in all vaccine strains of M. bovis BCG but present in all of the tested strains and isolates of pathogenic M. tuberculosis and M. bovis (16, 23). The analysis of the RD1 DNA segment for open reading frames (ORFs) by Mahairas et al. suggested the presence of 8 ORFs (23), the genomic prediction by Gordon et al. predicted 9 ORFs (16), and Amoudy et al. predicted the presence of 20 ORFs (ORF1 to ORF20) in RD1, of which 14 ORFs (ORF2 to ORF15) were deleted in M. bovis BCG (7) (Table 1). As all of the ORFs predicted by Amoudy et al. are expressed in M. tuberculosis at the mRNA level (7), this prediction was considered appropriate to test for immunological reactivity.

TABLE 1.

Description of ORF annotation, gene designation, position of ORFs on RD1 DNA segment, length of the predicted proteins, and number of overlapping synthetic peptides used in this study

| Gene designation | ORF annotation by source (reference no.)a

|

Position on RD1 (nucleotide no.)b | Length of protein (aa) | No. of synthetic peptides | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahairas et al. (23) | Gordon et al. (16) | Amoudy et al. (7) | ||||

| Rv3871 | ORF1A | Rv3871 | ORF2 | 1-1776 | 591 | 39 |

| PE35 | NP | Rv3872 | ORF3 | 1919-2218 | 98 | 6 |

| orf4 | NP | NP | ORF4 | 3126-2707 | 139 | 9 |

| PPE68 | ORF1B | Rv3873 | ORF5 | 2240-3355 | 371 | 24 |

| esxB/cfp10 | NP | Rv3874 | ORF6 | 3448-3750 | 100 | 6 |

| esxA/esat6 | ORF1C | Rv3875 | ORF7 | 3783-4070 | 95 | 6 |

| orf8 | NP | NP | ORF8 | 4614-4195 | 139 | 9 |

| Rv3876 | ORF1D | Rv3876 | ORF9 | 4184-6184 | 666 | 44 |

| Rv3877 | ORF1E | Rv3877 | ORF10 | 6058-7716 | 552 | 36 |

| Rv3878 | ORF1F | Rv3878 | ORF11 | 7867-8709 | 280 | 18 |

| orf12 | ORF1G | NP | ORF12 | 8899-10539 | 563 | ND |

| Rv3879c | ORF1K | Rv3879 | ORF13 | 10956-8767 | 746 | ND |

| orf14 | NP | NP | ORF14 | 9689-10426 | 262 | 17 |

| orf15 | NP | NP | ORF15 | 10792-11079 | 95 | 6 |

NP, not predicted; ND, not determined.

Positions are from reference 16.

To test immunological relevance of various RD1 ORFs, we have previously attempted to express six ORFs (ORF10 to ORF15) in Escherichia coli and purify the recombinant proteins (1). However, due to several problems including the inability to express the ORFs in E. coli and extensive degradation of expressed proteins, we could purify only two of the targeted proteins, i.e., ORF11 (Rv3878) and ORF14 (1 and unpublished data). When tested with human serum, ORF14 was found to be a major antigen recognized by antibodies in sera of TB patients (1). Interestingly, ORF14 was predicted only by Amoudy et al. but not by others (7) (Table 1), and several studies have confirmed that ORF14 is a real protein coding gene of M. tuberculosis that is expressed under both in vitro and in vivo growth conditions (1, 8, 11). These findings suggest that to identify additional antigens of diagnostic and/or vaccine relevance, a systematic screening of all RD1 ORF proteins should be performed for immunological reactivity. However, such a study for antibody reactivity can be done only with full-length proteins as the epitopes recognized by antibodies are mostly conformational in nature whereas, in the case of T-cell reactivity, the problem of nonavailability of full-length proteins can be overcome by using synthetic peptides because T cells recognize mostly structural epitopes (reviewed in reference 28).

A number of studies have demonstrated the validity of the synthetic peptide approach for Th1 cell reactivity by using nonselected mixtures of overlapping synthetic peptides spanning the sequences of antigens like CFP10, ESAT6, Ag85B, and MPB70, for example. (3, 6, 22, 40). In these studies, it was shown that Th1 cell reactivities with the peptide mixtures were equivalent to the reactivities induced by the corresponding full-length proteins, thereby suggesting that overlapping synthetic peptides could replace complete antigens in T-cell responses. However, the tested pools have been comprised of peptides corresponding to single antigenic proteins (6, 10, 22, 40), whereas testing of RD peptides would require pools of hundreds of peptides covering the sequence of several putative proteins in each RD (16). To make T-cell assays feasible for testing peptides covering several protein regions, it is therefore essential that systems are established to test pools of hundreds of peptides in a single well of a 96-well plate. This requirement is more compelling now because the availability of the complete genome sequences of a large number of pathogenic organisms and the prediction of encoded ORFs require their functional characterization in terms of immunological reactivity for application in diagnosis and vaccine development. Furthermore, although selected ORFs of RD1, i.e., ESAT6, CFP10, Rv3873, Rv3878, and Rv3879c, have been tested in the past using pools of synthetic peptides (10, 22), a comprehensive analysis of RD1 ORFs for Th1 cell reactivity, and especially of the ORFs that were predicted exclusively by Amoudy et al., is lacking in humans.

The aim of the present study was to use 220 overlapping synthetic peptides covering the sequence of 12 RD1 ORFs (Table 1) as a pool (RD1pool) to determine the possibility of using pools of large numbers of peptides in Th1 cell assays. In addition, we systematically screened the peptide pool of each RD1 ORF to identify major Th1 cell antigens recognized by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from HLA-heterogeneous TB patients and M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects living in Kuwait. The promiscuous peptides of major antigens were identified by HLA-DR prediction analysis using the ProPred server, and immunodominant peptides recognized by Th1 cells were identified by testing individual peptides with PBMC from HLA-heterogeneous subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

TB patients included in the study were newly diagnosed and culture-confirmed cases of pulmonary TB (n = 40) attending the Chest Diseases Hospital, Kuwait. M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects (n = 38) were randomly selected from the blood donors at the Central Blood Bank, Kuwait. All the patients and healthy donors were serologically negative for human immunodeficiency virus, were PPD skin test positive (as determined with tuberculin PPD RT23 from the Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark), and included both Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti citizens residing in Kuwait. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects, and the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, Kuwait.

Complex mycobacterial antigens.

The complex mycobacterial antigens used in this study were irradiated whole-cell M. tuberculosis H37Rv (40), M. bovis BCG (34), and M. tuberculosis culture filtrate (provided by J. T. Belisle, Fort Collins, CO, and produced under NIH contract HHSN266200400091C/ADB contract AI40092, Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Materials Contract).

Synthetic peptides.

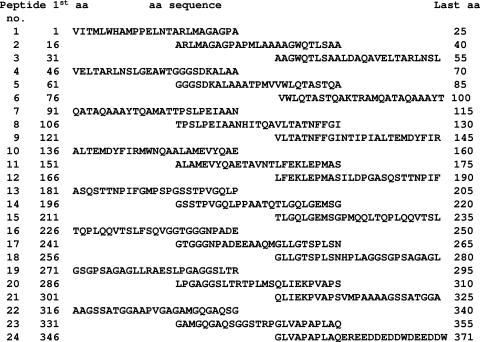

Thirteen synthetic peptides (25-mers overlapping neighboring peptides by 10 amino acids [aa]) spanning the sequence of MPB70 (6) and 220 peptides spanning the sequence of 12 RD1 ORFs (Table 1) were synthesized using fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry, as described previously (6, 39). For all peptides, identity was confirmed by mass spectroscopy, and purity was more than 70%. As an example, the sequences of peptides corresponding to PPE68 are shown in Fig. 1. The stock concentrations (5 mg/ml) of the peptides were prepared in normal saline (0.9%), as described previously (37, 39), and frozen at −70°C until used. The working concentrations were prepared by thawing the peptide solutions and dilution in complete tissue culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% human AB serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 40 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 2.5 μg of amphotericin B per ml).

FIG. 1.

Twenty-four 25-mer synthetic peptides covering the entire sequence of PPE68. The peptides overlap each other by 10 aa. The single-letter designations for amino acids are used.

Isolation of PBMC.

Heparinized venous blood was collected from pulmonary TB patients and buffy coats were obtained from BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. PBMC were separated from the blood and buffy coats by density centrifugation according to standard procedures (5, 36). The cells were finally suspended in 1 ml of complete tissue culture medium, tested for viability (>98% viable by trypan blue exclusion assay), and counted in a Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics Ltd., Luton, Bedfordshire, England).

Antigen- and peptide-induced proliferation of PBMC.

Antigen- and peptide-induced proliferation of PBMC was performed according to standard procedures (33, 44). In brief, PBMC (2 × 105 cells/well) suspended in 50 μl of complete tissue culture medium were seeded into the wells of 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). M. tuberculosis culture filtrate, each peptide in the peptide pools, and individual peptides in 50 μl of complete medium were added to the wells in triplicate at an optimal concentration of 5 μg/ml, and whole bacilli were used at 10 μg/ml (39). The final volume of the culture in the wells was adjusted to 200 μl. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. The cultures were pulsed (4 h) on day 6 with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham Life Sciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and harvested on filter mats with a Skatron harvester (Skatron Instruments AS, Oslo, Norway), and the radioactivity incorporated was measured by liquid scintillation counting (4, 30). The radioactivity incorporated was obtained as counts per minute (cpm). Average cpm were calculated from triplicate cultures stimulated with each antigen or peptide. Cellular proliferation results are presented as the stimulation index (SI), which is defined as follows: SI = number of cpm in antigen-stimulated cultures/number of cpm in cultures without antigen. The SI values of ≥5 and ≥3 were considered positive proliferative responses against complex mycobacterial antigens and peptides, respectively (6, 40).

IFN-γ assay.

Supernatants (100 μl) were collected from cultures of PBMC (96-well plates) before they were pulsed with [3H]thymidine. The supernatants were kept frozen at −70°C until they were assayed for IFN-γ activity. The amount of IFN-γ in the supernatants was quantified by using Immunotech immunoassay kits (Immunotech SAS, Marseille, France) as specified by the manufacturer. The detection limit of the IFN-γ assay kit was 0.08 IU/ml. Secretion of IFN-γ in response to a given antigen or peptide was considered positive when the delta IFN-γ value (the IFN-γ concentration in cultures stimulated with antigen or peptide minus the IFN-γ concentration in cultures without antigen or peptide) was ≥5 U/ml in response to complex antigens and ≥3 U/ml in response to peptides (3).

Interpretation of antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion results and statistical analysis.

An antigen/peptide was considered a strong, moderate, or weak stimulator of PBMC in proliferation and IFN-γ responses based on median values and percent positives. The responses were considered strong with a median SI and IFN-γ value of >5 and a percent positive value of >60%, moderate with a median SI and IFN-γ value of >3 to 5 and a percent positive from 40 to 60%, and weak with a median SI and IFN-γ value of ≤3 or a percent positive of <40%. The results of proliferation and IFN-γ secretion in response to various antigens/peptides in the two donor groups were analyzed statistically for significant differences using a Pearson chi-square test for two proportions, and P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

HLA typing of PBMC.

PBMC were HLA typed genomically by isolating the high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from each PBMC by treatment of the cells with proteinase K and salting out in miniscale, as described previously (3, 39). The amount of DNA obtained was quantified by spectrophotometry. An HLA-DR “low-resolution” kit containing the primers to type for DRB1, DRB3, DRB4, and DRB5 alleles and an HLA-DQ low-resolution kit to type for DQB1 alleles were purchased form Dynal AS (Oslo, Norway) and were used in PCR as described by the manufacturer. DNA amplification was carried out with a GeneAmp 2400 PCR system (Perkin-Elmer Cetus), and the amplified products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis by using standard procedures. Serologically defined HLA-DR and -DQ specificities were determined from the genotypes by following the guidelines provided by Dynal AS.

ProPred analysis for promiscuous binding regions in PPE68 protein.

HLA-DR binding propensities along the primary structure of PPE68 and its individual peptides were detected by ProPred analysis at the default setting (threshold value of 3.0) using the server (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/propred/) (48). This server has been suggested to be a useful tool in locating the promiscuous binding regions that can bind to a total of 51 alleles belonging to nine serologically defined HLA-DR molecules (3, 30, 39, 48). These HLA-DR molecules are encoded by DRB1 and DRB5 genes including HLA-DR1 (2 alleles), DR3 (7 alleles), DR4 (9 alleles), DR7 (2 alleles), DR8 (6 alleles), DR11 (9 alleles), DR13 (11 alleles), DR15 (3 alleles), and DR51 (2 alleles). The server performs analysis for each of these alleles independently and computes the binding strength of all the peptides. The peptides predicted to bind >50% of the HLA-DR alleles included in the ProPred analysis were considered promiscuous for binding (39).

RESULTS

Antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion by PBMC of TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects to complex antigens, MPB70, and RD1pool.

PBMC from 40 culture-confirmed pulmonary TB patients and 30 M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects were tested for antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion against complex mycobacterial antigens and the peptide pools of MPB70 and RD1pool. In response to the complex mycobacterial antigens, PBMC from each donor responded to at least one of these antigens in both assays (data not shown). Furthermore, strong antigen-induced proliferation was observed with PBMC from TB patients (median SI, 16 to 25; percent positive, 70 to 85%) as well as healthy subjects (median SI, 14 to 17; percent positive, 75 to 90%) in response to all three complex mycobacterial antigens. The antigen-induced proliferation responses to MPB70 were moderate in both TB patients (median SI, 3.1; percent positive, 50%) and healthy subjects (median SI, 3.9; percent positive, 47%), whereas in response to RD1pool the PBMC from both donor groups showed strong antigen-induced proliferation responses (median SI values of 8.2 and 5.6 and percent positive responses of 66 and 71% in TB patients and healthy subjects, respectively). When tested in IFN-γ assays, the complex mycobacterial antigens and RD1pool induced strong responses in both groups, whereas MPB70 induced moderate responses in TB patients and strong responses in healthy subjects (Table 2). Furthermore, there were no significant differences (P > 0.05) in the responses evoked by RD1pool in TB patients and healthy donors. These results demonstrate that, in addition to complex antigens, the RD1pool also has antigens that induce strong Th1 cell responses in both TB patients and M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects.

TABLE 2.

Antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMC from TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in response to complex mycobacterial antigens, MPB70, and RD1pool

| Organism or antigena | Value for IFN-γ secretion parameter by study group

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB patients (n = 40)b

|

BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects (n = 30)b

|

|||||

| Median (U/ml [range]) | No. of positive subjects/no. of subjects tested | % Positive | Median (U/ml [range]) | No. of positive subjects/no. of subjects tested | % Positive | |

| M. tuberculosis | 34 (<0.4-316) | 35/40 | 88 | 53 (<0.4-335) | 28/30 | 93 |

| M. tuberculosis CF | 39 (<0.4-373) | 36/40 | 90 | 62 (3.8-285) | 29/30 | 97 |

| BCG | 42 (<0.4-357) | 37/40 | 93 | 88 (3.9-351) | 20/22 | 91 |

| MPB70 | 4.6 (<0.4-82) | 23/38 | 60 | 18 (<0.4-207) | 17/24 | 71 |

| RD1pool | 22 (<0.4-335) | 32/38 | 84 | 9.0 (<0.4-60) | 18/22 | 82 |

CF, culture filtrate.

n, number of subjects.

Antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion by PBMC of TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in response to peptide pools of individual ORFs of RD1.

To identify the major Th1 cell-stimulating antigens encoded by RD1 ORFs, pools of synthetic peptides covering the amino acid sequence of each ORF were tested with PBMC from the above group of TB patients and healthy subjects in antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ assays. The results showed that all ORFs induced positive responses in one or both assays in a portion of TB patients and healthy subjects tested; i.e., responses ranged from 16 to 73% and 0 to 70% in antigen-induced proliferation (data not shown) and from 18 to 80% and 17 to 73% in IFN-γ assays (Table 3), respectively. However, strong responses were induced by the peptide pools of PPE68, CFP10, and ESAT6 in TB patients and by the peptide pool of PPE68 in healthy subjects in both assays whereas other ORFs showed weak to moderate responses in both donor groups and in both assays (Table 3; data shown for IFN-γ only). To further analyze the responses of healthy subjects to individual ORFs in relation to being infected and noninfected with M. tuberculosis, the BCG-vaccinated subjects were divided into ESAT6/CFP10 responders (n = 15) and nonresponders (n = 15), respectively. The analysis of results showed that only PPE68 induced strong IFN-γ responses in both groups of healthy subjects, with median values of 23 and 13 U/ml and percent positives of 80 and 67% in ESAT6/CFP10 responders and nonresponders, respectively. HLA-DR and -DQ typing of PBMC showed that TB patients and healthy subjects included in the study were highly HLA heterogeneous and covered all the major specificities of HLA-DR and -DQ (data not shown), thus suggesting that the major antigens (PPE68, CFP10, and ESAT6) were presented promiscuously to the responding cells.

TABLE 3.

Antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMC from TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in response to peptide pools of RD1 ORFs

| Antigen | Value for IFN-γ secretion parameter by study group

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB patients (n = 40)a

|

BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects (n = 30)a

|

|||||

| Median (U/ml [range])b | No. of positive subjects/no. of subjects tested | % Positive | Median (U/ml [range])b | No. of positive subjects/no. of subjects tested | % Positive | |

| Rv3871 | 1.3 (<0.4-47) | 12/40 | 30% | 3.8 (<0.4-84) | 16/30 | 53 |

| PE35 | 0.4 (<0.4-108) | 11/40 | 28% | 1.0 (<0.4-72) | 10/30 | 33 |

| ORF4 | 0.5 (<0.4-15) | 7/40 | 18% | 0.9 (<0.4-17) | 11/30 | 37 |

| PPE68 | 9.0 (<.4-171) | 27/40 | 68% | 22 (<0.4-108) | 22/30 | 73 |

| CFP10 | 18.3 (<0.4-235) | 32/40 | 80% | 2.9 (<0.4-107) | 14/30 | 47 |

| ESAT6 | 15.4 (<0.4-361) | 32/40 | 80% | 2.1 (<0.4-114) | 11/30 | 37 |

| ORF8 | 3.0 (<0.4-41) | 21/39 | 54% | <0.4 (<0.4-51) | 10/30 | 33 |

| Rv3876 | 2.7 (<0.4-270) | 19/40 | 48% | 3.0 (<0.4-124) | 15/30 | 50 |

| Rv3877 | 1.1 (<0.4-194) | 13/39 | 33% | <0.4 (<0.4-82) | 6/30 | 20 |

| Rv3878 | 1.3 (<0.4-10.5) | 15/37 | 40% | <0.4 (<0.4-13) | 5/30 | 17 |

| ORF14 | <0.4 (<0.4-121) | 11/37 | 30% | <0.4 (<0.4-23) | 5/30 | 17 |

| ORF15 | <0.4 (<0.4-305) | 8/37 | 22% | <0.4 (<0.4-102) | 10/30 | 33 |

n, number of subjects.

Median IFN-γ concentrations representing positive responses (delta IFN-γ of ≥3 U/ml) are given in bold.

ProPred analysis for promiscuous HLA-DR binding and identification of immunodominant peptides of PPE68 by testing PBMC from TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects.

The promiscuous nature of ESAT6 and CFP10 for HLA-DR binding and presentation to Th1 cells has been reported previously (39). In this study, to determine the promiscuous nature of PPE68 and its peptides, the full-length protein and the peptide sequences were analyzed for prediction to bind HLA-DR molecules by using the ProPred server. The analysis showed that PPE68 was predicted to bind 50/51 (98%) of the HLA-DR specificities included in ProPred (Table 4). Furthermore, 19/24 of PPE68 peptides were predicted to bind one or more HLA-DR specificities, with four peptides predicted to be promiscuous binders, i.e., peptides at residues 61 to 85, 121 to 145, 136 to 160, and 301 to 325 (Table 4). To identify the peptide(s) of PPE68 inducing antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion in healthy subjects and TB patients, individual peptides of PPE68 were tested with PBMC of both donor groups in both of the assays. In healthy subjects, all peptides induced positive responses in a portion of donors (positive responses ranging from 17 to 50% in proliferation and 30 to 70% in IFN-γ assays); however, best responses were seen with the peptide 121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145 (Table 4; data shown for proliferation only). The same peptide was also found to be the best stimulator of PBMC from TB patients when individual peptides of PPE68 were tested in antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ assays (data not shown). Thus, the sequence 121 to 145 represented the immunodominant peptide of PPE68, which contained the promiscuous epitope region responsible for inducing positive Th1 cell responses in both TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects.

TABLE 4.

HLA-DR binding prediction analysis of PPE68 and its peptides and their reactivities in antigen-induced proliferation assays with PBMC from BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects

| Peptide (residues) | HLA-DR binding prediction

|

Proliferation (n = 30)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive specificities/no. of specificities tested | % Binding | Median SI | No. of positive subjects/no. of subjects tested | % Positive | |

| PPE68pool | 50/51 | 98 | 5.6 | 21/30 | 70 |

| 1-25 | 1/51 | 2 | 1.1 | 5/30 | 17 |

| 16-40 | 6/51 | 12 | 0.9 | 8/30 | 27 |

| 31-55 | 22/51 | 43 | 1.1 | 5/30 | 17 |

| 46-70 | 0/51 | 0 | 1.4 | 11/30 | 37 |

| 61-85 | 35/51 | 69 | 1.4 | 8/30 | 27 |

| 76-100 | 9/51 | 18 | 1.5 | 7/30 | 23 |

| 91-115 | 0/51 | 0 | 1.1 | 8/30 | 27 |

| 106-130 | 3/51 | 6 | 0.8 | 7/30 | 23 |

| 121-145 | 33/51 | 65 | 3.4 | 15/30 | 50 |

| 136-160 | 38/51 | 75 | 1.2 | 10/30 | 33 |

| 151-175 | 24/51 | 47 | 1.4 | 11/30 | 37 |

| 166-190 | 24/51 | 47 | 1.1 | 10/30 | 33 |

| 181-205 | 23/51 | 45 | 1.7 | 10/30 | 33 |

| 196-220 | 2/51 | 4 | 2.1 | 9/30 | 30 |

| 211-235 | 6/51 | 12 | 1.9 | 10/30 | 33 |

| 226-250 | 23/51 | 45 | 1.3 | 12/30 | 40 |

| 241-265 | 11/51 | 22 | 1.5 | 9/30 | 30 |

| 256-280 | 0/51 | 0 | 0.8 | 9/30 | 30 |

| 271-295 | 16/51 | 31 | 1.3 | 9/30 | 30 |

| 286-310 | 19/51 | 37 | 1.4 | 8/30 | 27 |

| 301-325 | 29/51 | 57 | 1.3 | 9/30 | 30 |

| 316-340 | 0/51 | 0 | 2.8 | 14/30 | 47 |

| 331-355 | 18/51 | 35 | 1.7 | 9/30 | 30 |

| 346-371 | 0/51 | 0 | 1.4 | 6/30 | 20 |

The median positive responses (SI of ≥3) are given in bold. n, number of subjects.

Identification of the promiscuous epitope region in peptide 121 to 145 of PPE68 and its presence in mycobacterial species.

The search for homologies with the sequence of immunodominant peptide 121-VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR-145 in the NCBI database showed that it was present in the PPE family proteins of laboratory as well as clinical stains of M. tuberculosis (H37Ra, H37Rv, C, F11, Haarlem, and CDC15151) and M. bovis AF2122/97 (data not shown). In addition, a 14-aa stretch (124-ATNFFGINTIPIAL-137) of this peptide was also present in several PPE family proteins present in various mycobacterial species, including M. bovis BCG vaccines (data not shown). HLA-DR binding prediction analysis using the ProPred server revealed that the promiscuous region of peptide 121 to 145 was confined to the 10-aa sequence 127-FFGINTIPIA-136, which was predicted to bind the same number of HLA-DR alleles (33/51, or 65%) as the peptide at position 121 to 145 (Table 4). To study the recognition by Th1 cells, the peptides at positions 124 to 137 and 127 to 136 were also synthesized and tested along with the peptide at position 121 to 145 with PBMC from eight HLA-heterogeneous BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects that responded to M. tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG, a peptide pool of PPE68, and the peptide at position 121 to 145 in IFN-γ assays (Table 5). The results showed that all of the eight donors responded to peptides at positions 124 to 137 and 127 to 136, whereas two other peptides of PPE68 from the C terminus region, i.e., the peptide at positions 331 to 355 and 356 to 371, stimulated PBMC for IFN-γ secretion from only two of the six tested donors (Table 5). These results confirmed the finding that the immunodominant and promiscuous Th1 cell epitope of PPE68 was present in M. bovis BCG vaccines and was limited to the 10-aa sequence 127-FFGINTIPIA-136.

TABLE 5.

Antigen-induced IFN-γ secretion by PBMC from HLA-DR heterogeneous M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects in response to mycobacterial antigens and peptides of PPE68

| Organism, antigen, or peptide (residues) | Peptide sequence | Antigen-induced IFN-γ (U/ml) secretion by PBMC from the indicated donora

|

No. of positive subjects/no. of subjects tested | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| M. bovis BCG | 43 | 44 | 27 | 18 | 40 | 43 | 15 | 30 | 8/8 | |

| M. tuberculosis | 48 | 43 | 26 | 21 | 40 | 45 | 37 | 29 | 8/8 | |

| PPE68pool | 43 | 10 | 23 | 10 | 26 | 21 | 21 | 10 | 8/8 | |

| 121-145 | VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR | 39 | 5.0 | 19 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 16 | 26 | 9.0 | 8/8 |

| 124-137 | ATNFFGINTIPIAL | 41 | 17 | 13 | 5.0 | 28 | 17 | 12 | 8.0 | 8/8 |

| 127-136 | FFGINTIPIA | 50 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 16 | 15 | 7.0 | 8/8 |

| 331-355 | GAMGQGAQSGGSTRPGLVAPAPLAQ | 5.6 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 7.3 | 2.0 | ND | ND | 2/6 |

| 346-371 | GLVAPAPLAQEREEDDEDDWDEEDDW | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 7.0 | 23 | 2.0 | ND | ND | 2/6 |

The following were the HLA-DR and HLA-DQ types of the healthy donors included in this table: donor 1, DR7, DR17, DR52, DR53, DQ2, and DQ6; donor 2, HLA types not determined; donor 3, DR11, DR13, DR52, and DQ7; donor 4, DR17, DR52, and DQ2; donor 5, DR1, DR18, DR52, DQ4, and DQ5; donor 6, DR14, DR15, DR51, DR52, DQ5, and DQ6; donor 7, DR4, DR16, DR51, DR53, DQ5, and DQ8; donor 8, DR4, DR17, DR52, DR53, DQ2, and DQ8. IFN-γ concentrations representing positive responses (delta IFN-γ values of ≥5 U/ml with complex antigens and ≥3 U/ml with peptides) are given in bold. ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

We have evaluated Th1 cell reactivity of 12 ORFs of the RD1 segment of M. tuberculosis by using PBMC from TB patients and M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of an approach using a large peptide pool for Th1 cell reactivity and the most comprehensive analysis of RD1-encoded proteins for Th1 cell reactivity in TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy humans. The test systems used to determine Th1 cell reactivity were antigen-induced proliferation and IFN-γ secretion assays (17, 25). IFN-γ is considered the most important Th1 cytokine involved in protective immunity against TB (2, 13, 15); therefore, in order to identify new candidates for safer subunit/peptide vaccines, it is important to identify major M. tuberculosis antigens and immunodominant peptides recognized by IFN-γ-secreting T cells. In addition, M. tuberculosis-specific antigens inducing IFN-γ production could also be useful in the specific diagnosis of TB (reviewed in reference 26).

To overcome the problems associated with recombinant protein expression and purification, as reported previously (1, 8, 11), we have used in this study pools of 220 synthetic peptides covering RD1 ORFs of various sizes (Table 1). One of the obvious advantages of this approach is the speed with which peptides can be synthesized and tested for Th1 cell reactivity. Furthermore, major antigens and immunodominant peptides could be identified, and exact T-cell epitopes could be defined by subsequent testing of peptide pools corresponding to individual ORFs, followed by single peptides included in the pools (5, 40, 41). Each synthetic peptide was 25 aa in length and overlapped with the neighboring peptides by 10 residues. The reason for the 10-residue overlap was to greatly reduce the probability of missing T-cell epitopes, which are usually ≤10 aa in length (24). Furthermore, the inclusion of peptides of CFP10 and ESAT6, the two major and widely studied antigens recognized by TB patients (9, 10, 26, 27, 38), in the RD1pool acted as a quality control to ensure the reliability of a large peptide pool approach for determining Th1 cell reactivity.

The results of testing PBMC from TB patients for Th1 cell reactivity with the RD1pool were highly encouraging because a large proportion of the tested patients responded to this pool (Table 2), and the responses to the RD1pool were of magnitudes similar to peptide pools of individual ORFs like ESAT6 and CFP10, as reported previously (10, 26, 27, 38) and also found in this study (Table 3). These results suggest that large peptide pools corresponding to ORFs of various sizes could faithfully be tested for T-cell reactivity in proliferation and IFN-γ assays without having a significant inhibitory activity on the responses to individual ORFs constituting the pool. Thus, our results set the stage to use pools of synthetic peptides corresponding to other RDs of M. tuberculosis, i.e., RD4 to RD7, RD9 to RD13, and RD15, which are absent in M. bovis and M. bovis BCG and are predicted to encode antigens of diagnostic and vaccine potential (16, 43).

We further evaluated the RD1pool for the specificity of response by testing PBMC from M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. Since we had included in this pool the peptides corresponding to the ORFs of RD1 that are deleted in M. bovis BCG, we had expected significantly lower responses to the RD1pool in BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. However, contrary to our expectation, the RD1pool induced strong cell proliferation and IFN-γ responses with PBMC from healthy subjects (Tables 2). The strong responses to RD1pool in M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects could have been due to either infection with M. tuberculosis, as reported with healthy people living in Mumbai, India (21), or the presence of antigens other than ESAT6 and CFP10. In Kuwait, by using peptides of CFP10 and ESAT6, we have previously shown that M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects showed weak responses to these antigens (6). Thus, strong responses to RD1pool with PBMC of healthy subjects in this study suggest that antigens other than ESAT6 and CFP10 may be involved. To identify such antigens, we tested the peptide pools of each RD1 ORF separately in Th1 cell assays. The results showed that PPE68, CFP10, and ESAT6 were strong stimulators of Th1 cells in TB patients, whereas in BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects only PPE68 induced strong responses. These results suggest that the strong Th1 responses to RD1pool in BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects were primarily due to the peptides of PPE68.

The major recognition of PPE68 by T cells was first reported by us in a cattle model of TB (32) and later extended by others in mouse (12) and humans (22, 45). Our studies in cattle (32) as well as the studies of Demangel et al. in mouse (12) show that PPE68 was recognized by animals infected with M. bovis and M. tuberculosis, respectively, but not by animals vaccinated with M. bovis BCG. However, in humans, our present study (using Asian donors resident in Kuwait) and two previous studies (using Caucasian donors residing in the United Kingdom [22] and Denmark [45]) show that both TB patients and M. bovis BCG-vaccinated healthy humans respond to PPE68 in Th1 cell assays. Furthermore, the nonresponsiveness to PPE68 of healthy Danish subjects not vaccinated with BCG (45) suggests that the response in healthy BCG-vaccinated subjects was due to BCG vaccination and not due to exposure to environmental mycobacteria. However, differences exist in the magnitude of response; i.e., in our study 64% of ESAT6/CFP10 nonresponders responded to PPE68, whereas of tested BCG-vaccinated donors 7.9% in the United Kingdom (22) and 17.5% in Denmark (45) responded to PPE68.

It is well known that T cells recognize antigen in association with highly polymorphic HLA molecules. Therefore, among the requirements for new antigens to qualify as diagnostic reagents and/or vaccine candidates is their recognition by an HLA-heterogeneous group of donors (24, 35). The results of HLA-DR and -DQ typing showed that the TB patients and healthy donors tested in this study were HLA heterogeneous and represented all of the frequently expressed specificities of HLA-DR and -DQ molecules. Furthermore, based on the ProPred server analysis for HLA-DR binding prediction, our previous work has suggested that the antigens CFP10 and ESAT6 are promiscuous HLA-DR binders (39). The analysis of the PPE68 sequence for HLA-DR binding prediction in this study suggests that this antigen is also a promiscuous HLA-DR binder. Thus, our overall results suggest that HLA restriction will not be a problem if the above RD1 antigens are used in diagnostic applications and/or as vaccine candidates against TB.

After identifying PPE68 as the major antigen in both TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects, our next aim was to identify the immunodominant peptide(s) of this protein recognized by Th1 cells and determine if differences between TB patients and healthy subjects existed at the peptide level. We therefore tested the individual peptides of ORF5 (PPE68) with PBMC from healthy donors and TB patients in the Th1 cell assays. The results revealed that a single peptide, peptide VLTATNFFGINTIPIALTEMDYFIR, qualified to be immunodominant in both donor groups. The HLA-DR heterogeneity of the responding subjects and the prediction to bind 65% of the HLA-DR specificities included in ProPred strongly suggest that this peptide was presented to Th1 cells promiscuously. The previous studies have identified the immunodominant sequences of PPE68 as VLTATNFFGINTIPIALT in humans (45) and ATNFFGINTIPIALTE in mice (12), and these sequences have been shown to have high sequence homology with other PPE proteins present in M. bovis BCG and other mycobacteria (12, 45). In this study, we identified a shorter 14-aa sequence of PPE68, i.e., ATNFFGINTIPIAL, to be completely identical in PPE family proteins present in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG. Furthermore, ProPred analysis as well as testing with PBMC from BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects narrowed the promiscuous and immunodominant epitope region to the 10-aa sequence FFGINTIPIA.

In mice, Demangel et al. have shown that the peptide ATNFFGINTIPIALTE was recognized by T cells of mice infected with M. tuberculosis H37Rv and BCG::RD1 (BCG complemented with RD1) but not by BCG-vaccinated animals or mice injected with a PPE68 knockout construct (12), suggesting the specificity of the peptide for M. tuberculosis. However, their results are contrary to our results and the results of Okkels et al. (45) in humans, showing that the peptides containing the sequence ATNFFGINTIPIALTE are recognized by TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects. The results in humans are in line with the presence of the peptide sequence in PPE68 and several other PPE proteins, which are present in both BCG and M. tuberculosis. Demangel et al. have hypothesized that the nonrecognition of the peptide sequence ATNFFGINTIPIALTE in BCG-vaccinated mice, which is shared by many other PPE family proteins, may be due to the less appropriate presentation of other PPE proteins in mice (12).

Unlike the two other major Th1 cell-stimulating antigens encoded by RD1 genes (i.e., ESAT6 and CFP10), PPE68 is not related to the pathogenesis associated with RD1, as shown in SCID mice (12). M. tuberculosis specificity and association with pathogenesis suggest that the antigens ESAT6 and CFP10 should be reserved for diagnostic applications to detect latent and active TB, as reported previously (9, 10, 38, 42). However, the strong Th1 cell-stimulating ability of PPE68 in both TB patients and BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects and the nonassociation with pathogenesis suggest that PPE68 and its promiscuous immunodominant peptide sequences may be valuable as subunit and peptide-based vaccine candidates, respectively. The presence of PPE68-reactive IFN-γ-secreting T cells in healthy elderly Norwegians, who had converted to skin test PPD positivity in childhood due to natural infection but did not develop clinical disease or receive any treatment (45), further supports the usefulness of this antigen as a new vaccine candidate against TB.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University Research Administration grants MI03/05 and MI 02/02, and the College of Graduate Studies, Kuwait University, Kuwait.

We are grateful to the Director, Central Blood Bank, Kuwait for providing buffy coats from BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects and to A. S. El-Shamy (Chest Diseases Hospital, Kuwait) for providing blood from tuberculosis patients.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, S., H. A. Amoudy, J. E. Thole, D. B. Young, and A. S. Mustafa. 1999. Identification of a novel protein antigen encoded by a Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1 region gene. Scand. J. Immunol. 49:515-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Attiyah, R., A. El-Shazly, and A. S. Mustafa. 2006. Assessment of in vitro immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a human peripheral blood infection model using a luciferase reporter construct of M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 145:520-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Attiyah, R., and A. S. Mustafa. 2004. Computer-assisted prediction of HLA-DR binding and experimental analysis for human promiscuous Th1-cell peptides in the 24 kDa secreted lipoprotein (LppX) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 59:16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Attiyah, R., and A. S. Mustafa, A. T. Abal, A. S. El-Shamy, W. Dalemans, and Y. A. Skeiky. 2004. In vitro cellular immune responses to complex and newly defined recombinant antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138:139-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Attiyah, R., A. S. Mustafa, A. T. Abal, N. M. Madi, and P. Andersen. 2003. Restoration of mycobacterial antigen-induced proliferation and interferon-gamma responses in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of tuberculosis patients upon effective chemotherapy. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 38:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Attiyah, R., F. A. Shaban, H. G. Wiker, F. Oftung, and A. S. Mustafa. 2003. Synthetic peptides identify promiscuous human Th1 cell epitopes of the secreted mycobacterial antigen MPB70. Infect. Immun. 71:1953-1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amoudy, H. A., M. B. Al-Turab, and A. S. Mustafa. 2006. Identification of transcriptionally active open reading frames within the RD1 genomic segment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Med. Princ. Pract. 15:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amoudy, H. A., S. Ahmad, J. E. Thole, and A. S. Mustafa. 2007. Demonstration of in vivo expression of a hypothetical open reading frame (ORF-14) encoded by the RD1 region of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 66:422-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen, P., M. E. Munk, J. M. Pollock, and T. M. Doherty. 2000. Specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis. Lancet 356:1099-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arend, S. M., A. Geluk, K. E. van Meijgaarden, J. T. van Dissel, M. Theisen, P. Andersen, and T. H. M. Ottenhoff. 2000. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 and to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect. Immun. 68:3314-3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daugelat, S., J. Kowall, J. Mattow, D. Bumann, R. Winter, R. Hurwits, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2003. The RD1 proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: expression in Mycobacterium smegmatis and biochemical characterization. Microbes Infect. 5:1082-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demangel, C., P. Brodin, P. J. Cockle, R. Brosch, L. Majlessi, C. Leclerc, and S. T. Cole. 2004. Cell envelope protein PPE68 contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis RD1 immunogenicity independently of a 10-kilodalton culture filtrate protein and ESAT-6. Infect. Immun. 72:2170-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demissie, A., M. Abebe, A. Aseffa, G. Rook, H. Fletcher, A. Zumla, K. Weldingh, I. Brock, P. Andersen, T. M. Doherty, and the VACSEL Study Group. 2004. Healthy individuals that control a latent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis express high levels of Th1 cytokines and the IL-4 antagonist IL-4delta2. J. Immunol. 172:6938-6943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enarson, D. A. 2004. Use of the tuberculin skin test in children. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 5(Suppl. A):S135-S137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flynn, J. L. 2004. Immunology of tuberculosis and implications in vaccine development. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 84:93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon, S. V., R. Brosch, A. Billault, T. Garnier, K. Eiglmeier, and S. T. Cole. 1999. Identification of variable regions in the genomes of tubercle bacilli using bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Mol. Microbiol. 32:643-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao, X. S., J. M. Le, J. Vilcek, and T. W. Chang. 1986. Determination of human T cell activity in response to allogeneic cells and mitogens. An immunochemical assay for gamma-interferon is more sensitive and specific than a proliferation assay. Immunol. Methods 92:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harries, A. D., and C. Dye. 2006. Tuberculosis. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 100:415-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesseling, A. C., B. J. Marais, R. P. Gie, H. S. Schaaf, P. E. Fine, P. Godfrey-Faussett, and N. Beyers. 2007. The risk of disseminated Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) disease in HIV-infected children. Vaccine 25:14-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill, P. C., D. Jackson-Sillah, A. Fox, K. L. Franken, M. D. Lugos, D. J. Jeffries, S. A. Donkor, A. S. Hammond, R. A. Adegbola, T. H. Ottenhoff, M. R. Klein, and R. H. Brookes. 2005. ESAT-6/CFP-10 fusion protein and peptides for optimal diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by ex vivo enzyme-linked immunospot assay in the Gambia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2070-2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalvani, A., P. Nagvenkar, Z. Udwadia, A. A. Pathan, K. A. Wilkinson, J. S. Shastri, K. Ewer, A. V. Hill, A. Mehta, and C. Rodrigues. 2001. Enumeration of T cells specific for RD1-encoded antigens suggests a high prevalence of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in healthy urban Indians. J. Infect. Dis. 183:469-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, X. Q., D. Dosanjh, H. Varia, K. Fewer, P. Cockle, G. Pasvol, and A. Lalvani. 2004. Evaluation of T-cell responses to novel RD1- and RD2-encoded Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene products for specific detection of human tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 72:2574-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahairas, G. G., P. J. Sabo, M. J. Hickey, D. C. Singh, and C. K. Stover. 1996. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J. Bacteriol. 178:1274-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustafa, A. S. 2000. HLA-restricted immune response to mycobacterial antigens: relevance to vaccine design. Hum. Immunol. 61:166-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustafa, A. S. 2001. Biotechnology in the development of new vaccines and diagnostic reagents against tuberculosis. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2:157-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustafa, A. S. 2002. Development of new vaccines and diagnostic reagents against tuberculosis. Mol. Immunol. 39:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mustafa, A. S. 2005. Progress towards the development of new anti-tuberculosis vaccines, p. 47-76. In L. T. Smithe (ed.), Focus on tuberculosis research. Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York, NY.

- 28.Mustafa, A. S. 2005. Recombinant and synthetic peptides to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens and epitopes of diagnostic and vaccine relevance. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 85:367-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa, A. S. 2005. Mycobacterial gene cloning and expression, comparative genomics, bioinformatics and proteomics in relation to the development of new vaccines and diagnostic reagents. Med. Princ. Pract. 14(Suppl. 1):27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustafa, A. S., A. T. Abal, F. Shaban, A. M. El-Shamy, and H. A. Amoudy. 2005. HLA-DR binding prediction and experimental evaluation of T-cell epitopes of mycolyl transferase 85B (Ag85B), a major secreted antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Med. Princ. Pract. 14:140-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mustafa, A. S., H. A. Amoudy, H. G. Wiker, A. T. Abal, P. Ravn, F. Oftung, and P. Andersen. 1998. Comparison of antigen-specific T-cell responses of tuberculosis patients using complex or single antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 48:535-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustafa, A. S., P. J. Cockle, F. Shaban, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2002. Immunogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RD1 region gene products in infected cattle. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 130:37-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mustafa, A. S., A. Deggerdal, K. E. Lundin, R. M. Meloen, T. M. Shinnick, and F. Oftung. 1994. An HLA-DRw53-restricted T-cell epitope from a novel Mycobacterium leprae protein antigen important to the human memory T-cell repertoire against M. leprae. Infect. Immun. 62:5595-5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mustafa, A. S., G. Kvalheim, M. Degre, and T. Godal. 1986. Mycobacterium bovis BCG-induced human T-cell clones from BCG-vaccinated healthy subjects: antigen specificity and lymphokine production. Infect. Immun. 53:491-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustafa, A. S., K. E. Lundin, and F. Oftung. 1993. Human T cells recognize mycobacterial heat shock proteins in the context of multiple HLA-DR molecules: studies with healthy subjects vaccinated with Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium leprae. Infect. Immun. 61:5294-5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mustafa, A. S., K. E. Lundin, and F. Oftung. 1998. Isolation of recombinant phage clones expressing mycobacterial T cell antigens by screening a recombinant DNA library with human CD4+ Th1 clones. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 22:205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mustafa, A. S., K. E. Lundin, R. H. Meloen, T. M. Shinnick, and F. Oftung. 1999. Identification of promiscuous epitopes from the Mycobacterial 65-kilodalton heat shock protein recognized by human CD4+ T cells of the Mycobacterium leprae memory repertoire. Infect. Immun. 67:5683-5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mustafa, A. S., F. Oftung, H. A. Amoudy, N. M. Madi, A. T. Abal, F. Shaban, I. Rosen Krands, and P. Andersen. 2000. Multiple epitopes from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen are recognized by antigen-specific human T cell lines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30(Suppl. 3):S201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mustafa, A. S., and F. A. Shaban. 2006. ProPred analysis and experimental evaluation of promiscuous T-cell epitopes of three major secreted antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 86:115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mustafa, A. S., F. A. Shaban, A. T. Abal, R. Al-Attiyah, H. G. Wiker, K. E. Lundin, F. Oftung, and K. Huygen. 2000. Identification and HLA restriction of naturally derived Th1-cell epitopes from the secreted Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85B recognized by antigen-specific human CD4+ T-cell lines. Infect. Immun. 68:3933-3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mustafa, A. S., F. A. Shaban, R. Al-Attiyah, A. T. Abal, A. M. El-Shamy, P. Andersen, and F. Oftung. 2003. Human Th1 cell lines recognize the Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 antigen and its peptides in association with frequently expressed HLA class II molecules. Scand. J. Immunol. 57:125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mustafa, A. S., Y. A. Skeiky, R. Al-Attiyah, M. R. Alderson, R. G. Hewinson, and H. M. Vordermeier. 2006. Immunogenicity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens in Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated and M. bovis-infected cattle. Infect. Immun. 74:4566-4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mustafa Abu, S., and R. Al-Attiyah. 2003. Tuberculosis: looking beyond BCG vaccines. J. Postgrad. Med. 49:134-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oftung, F., A. Geluk, K. E. Lundin, R. H. Meloen, J. E. Thole, A. S. Mustafa, and T. H. M. Ottenhoff. 1994. Mapping of multiple HLA class II-restricted T-cell epitopes of the mycobacterial 70-kilodalton heat shock protein. Infect. Immun. 62:5411-5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okkels, L. M., I. Brock, F. Follmann, E. M. Agger, S. M. Arend, T. H. M. Ottenhoff, F. Oftung, I. Rosenkrands, and P. Andersen. 2003. PPE protein (Rv3873) from DNA segment RD1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: strong recognition of both specific T-cell epitopes and epitopes conserved within the PPE family. Infect. Immun. 71:6116-6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padayatchi, N., and G. Friedland. 2007. Managing multiple and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 8:1035-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravn, P., A. Demissie, T. Eguale, H. Wondwosson, D. Lein, H. A. Amoudy, A. S. Mustafa, A. K. Jensen, A. Holm, I. Rosenkrands, F. Oftung, J. Olobo, F. von Reyn, and P. Andersen. 1999. Human T cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 179:637-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh, H., and G. P. S. Raghava. 2001. ProPred: Prediction of HLA-DR binding sites. Bioinformatics 17:1236-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trunz, B. B., P. Fine, and C. Dye. 2006. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet 367:1173-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang, H., C. H. Shi, Y. Xue, Y. L. Bai, L. M. Wang, and Z. K. Xu. 2006. Immune response and protective efficacy induced by fusion protein ESAT6-CFP10 of M. tuberculosis in mice. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 22:443-446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]