Abstract

Knockout mutants of Fusarium oxysporum lacking the putative photoreceptor Wc1 were impaired in aerial hyphae, surface hydrophobicity, light-induced carotenogenesis, photoreactivation after UV treatment, and upregulation of photolyase gene transcription. Infection experiments with tomato plants and immunodepressed mice revealed that Wc1 is dispensable for pathogenicity on plants but required for full virulence on mammals.

Light is a signal from the environment that regulates different aspects of fungal development. Photoreceptors perceive light and generate signals, the propagation of which stimulates cellular responses, such as carotenoid biosynthesis, spore formation, and phototropism, among others (20, 24). White collar 1 (WC-1) and WC-2 are two key elements involved in light signal transduction in Neurospora crassa, the best-studied fungal system (2, 21, 24). The genes that are orthologous to N. crassa wc-1 in several ascomycetes, basidiomycetes, and zygomycetes have also been identified (6).

In this work, we have characterized the wc1 gene, an orthologue of N. crassa wc-1, in Fusarium oxysporum, a soilborne pathogen that causes economically important losses of a wide variety of crops (8) and has been reported as an emerging human pathogen (27, 28). The wc1 gene was cloned by PCR, using gene-specific primers based on the locus FOXG_03727.2 in the F. oxysporum genome sequence (https://www.broad.mit.edu/annotation/). F. oxysporum wc1 was expressed independently of light at very low levels, as determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (data not shown). The predicted gene product showed various degrees of identity with Wc-1 proteins from Fusarium graminearum (91.1%; Broad Institute accession no. FG07941.1), N. crassa (58.0%; GenBank accession no. X94300), Magnaporthe grisea (55.3%; GenBank accession no. MG03538.4), and Mucor circinelloides (40.3%; GenBank accession no. AM040841). Similar to N. crassa WC-1, F. oxysporum Wc1 contained a putative activation domain at the N terminus, a LOV domain, two PAS dimerization domains, a nuclear localization sequence, and a Zn finger DNA binding domain. The LOV domain contained the 11 conserved amino acid residues suggested to accommodate the terminal adenine moiety of FAD (13) that is required for the binding of the WC-1/WC-2 complex to the frq gene (11), suggesting that F. oxysporum Wc1 has functions in light regulation that are similar to those of other Wc-1 photoreceptors.

To study the role of wc1, the gene was knocked out in F. oxysporum as reported previously (9). Several transformants carrying a copy of wc1 disrupted with the hygromycin resistance marker (Δwc1) were identified by PCR and Southern hybridization. The absence of full-length wc1 transcripts in the Δwc1 strain was confirmed by RT-PCR (data not shown), although the occurrence of truncated transcripts lacking the essential dimerization, nuclear localization signal, and DNA binding domains cannot be ruled out. Complementation of a Δwc1 strain was performed by cotransformation with the wc1 wild-type allele and the phleomycin resistance cassette, and the presence of the complementing wild-type allele (Δwc1+wc1) confirmed by PCR.

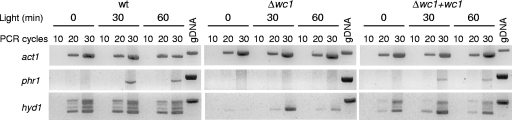

No significant differences were observed in the hyphal morphology and growth rate (determined as mycelial dry weight and sporulation rate) of the Δwc1 mutant and the wild-type strain grown in submerged culture (potato dextrose broth [PDB]) or on solid media (potato dextrose agar [PDA]), either in constant darkness or under photoperiods of 10 h dark/14 h white light. However, the Δwc1 strain did not produce aerial hyphae on PDA plates with cellophane sheets under photoperiods, suggesting a possible role of Wc1 in the hyphal development of F. oxysporum under these conditions. To test whether this phenotype was due to defects in surface hydrophobicity, water droplets were placed on the surface of fungal colonies grown either in the dark or under photoperiods. Drops remained for more than 4 h on the colony surface in all cases except for the Δwc1 mutant grown under photoperiods, where droplets rapidly soaked into the surface. To further investigate the light regulation of hydrophobicity by Wc1, the F. oxysporum genome was searched in silico, revealing four putative hydrophobin genes (hyd1, hyd3, hyd4, and hyd5) and an agglutinin-like gene (alp1). Similar expression profiles for hyd3, hyd4, hyd5, and alp1 were observed by semiquantitative RT-PCR of the wild-type, the Δwc1 mutant, and the Δwc1+wc1 strain grown in the dark or under illumination for 30 or 60 min (data not shown). By contrast, the expression of hyd1 was not detected in dark-grown mycelia from the Δwc1 mutant and appeared significantly decreased in this strain after illumination (Fig. 1). In the wild-type and the Δwc1+wc1 strains, different hyd1 transcript sizes were observed, containing either both, one, or none of the introns, whereas only the completely spliced form was detected in the Δwc1 mutant (Fig. 1). Differential splicing of a putative hydrophobin gene of Trichoderma viride in response to light was reported previously (32). These results suggest that Wc1 could play a role in the light-independent regulation of hyd1 transcription and mRNA processing and that hyd1 is not related to the light-dependent hydrophilic phenotype of the Δwc1 mutant.

FIG. 1.

Expression analysis of phr1 and hyd1 genes by semiquantitative RT-PCR of the wild type (wt), the Δwc1 mutant, and the Δwc1+wc1 strain grown on PDA plates under white light for the indicated time periods. Increasing numbers of amplification rounds were used, and the transcript signal was compared with that of the actin gene (act1). Amplification of genomic DNA (gDNA) was used as control for transcript size.

The light induction of carotenogenesis was studied by extracting carotenes from mycelia grown for 7 days in the dark or under photoperiods and measuring them as described previously (31). The carotenoid levels in dark-grown mycelia of the Δwc1 mutant were similar to those of the wild-type or the Δwc1+wc1 strain. Illumination of Δwc1 dark-grown mycelia caused a 32-fold increase in carotenes, compared with a 51-fold increase in carotenes in the wild type. Similar results have recently been recorded for the white collar wcoA mutants of Fusarium fujikuroi, which still maintain an efficient photoinduction of carotenoid biosynthesis (10). The partial defect in photoinduction of carotenogenesis in the Δwc1 mutant suggests the existence of Wc1-independent light signal transduction pathways in F. oxysporum. Although other types of photoreceptors have been identified in fungi, in few cases have their functions been elucidated (15). The F. oxysporum genome contains several putative photoreceptor genes, including two showing identity to the N. crassa cryptochrome DASH (4, 7), one to phytochrome phy-1 (12), two to opsin-1 (3), one to the vivid PAS protein VVD (14, 30), and one to the Aspergillus nidulans velvetA protein (26). Our results indicate that light induction of carotenogenesis in F. oxysporum may depend on some of these photoreceptors.

Transcriptional activation of photolyase genes mediated by white collar complexes was previously described in fungi (5, 18). We investigated the role of Wc1 in the expression of the F. oxysporum phr1 gene (1). The lethal effect of UV light on spore survival of the Δwc1 mutant (quantified as survival rate on PDA plates after irradiation of 109 microconidia with a 245-nm lamp) was similar to its effect on spores of the wild type (Table 1), but no recovery of survival after photoreactivation (induced by 5 h of white-light illumination of UV-irradiated spores followed by 48 h of incubation at 28°C in the dark) was detected in the Δwc1 mutant in comparison with the recovery of the wild-type or the Δwc1+wc1 strain, indicating a defect in the photoreactivation mechanism. To confirm this hypothesis, the levels of phr1 gene expression in the different strains in dark-grown mycelia or after different light periods were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Unlike in the wild-type and the Δwc1+wc1 strains, no light-transcriptional activation of phr1 was observed in the Δwc1 mutant (Fig. 1). Thus, we conclude that Wc1 regulates the phr1-mediated UV light resistance in F. oxysporum.

TABLE 1.

Effect of UV light treatment and photoreactivation by white light on F. oxysporum spore viabilitya

| Strain | % Survival rate (mean ± SD) before and after photoreactivation after UV dose (J m−2) of:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0

|

600

|

800

|

1,000

|

|||||

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | |

| Δwc1 | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 16.7 ± 1.3 | 13.9 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Wild type | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 20.8 ± 2.2 | 31.7 ± 0.6 | 7.9 ± 1.4 | 13.0 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| Δwc1+wc1 | 100 ± 0.0 | 100 ± 0.0 | 32.5 ± 2.3 | 41.5 ± 4.1 | 15.1 ± 0.4 | 21.8 ± 1.3 | 7.0 ± 0.3 | 13.1 ± 0.4 |

Microconidia were irradiated with the indicated UV dose and plated on PDA. Survival rates are calculated from the results of three replicate experiments. Experiments were performed three times with similar results.

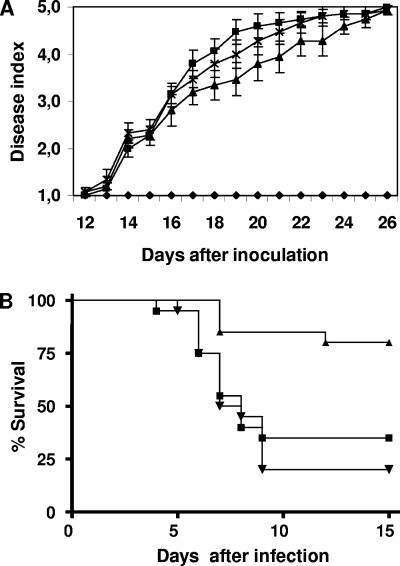

Several phytopathogenic fungi have been reported to harbor genes orthologous to wc-1 in their genomes (18, 19, 25), but their role in pathogenicity to plants has not been studied. We carried out tomato root infection assays with the different F. oxysporum strains as previously described (9, 16). No difference in the progression of the disease index with infection with the wild-type strain and the Δwc1 mutant was observed (Fig. 2A), suggesting that wc1 is dispensable for the virulence of F. oxysporum on plants.

FIG. 2.

(A) Incidence of Fusarium wilt on tomato plants (cv. Monika) caused by the wild type (squares), the Δwc1 mutant (triangles), and the Δwc1+wc1 strain (crosses). Severity of disease symptoms was recorded at different times after inoculation, using an index ranging from 1 (healthy plant) to 5 (dead plant) (16). Uninoculated plants were used as control (diamonds). Error bars indicate the standard deviations of the results from 20 plants for each treatment. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. (B) Virulence of different strains of F. oxysporum in immunodepressed mice. Groups of 10 mice were infected with 2 × 107 microconidia of the wild type (squares), the Δwc1 mutant (triangles), and the Δwc1+wc1 strain (inverted triangles) as described previously (28). Percent survival was plotted for 15 days. The results for infection with mutant Δwc1 differed significantly from the results for infection with the wild-type and the Δwc1+wc1 strains (P < 0.01). The experiment was performed three times. Data shown are from one representative experiment. Conditions were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Universitat Rovira I Virgili.

F. oxysporum tomato pathogenic isolate 4287 was previously found to infect and kill immunodepressed mice (28, 29). The injection of 2 × 107 microconidia of the wild type or the Δwc1+wc1 strain into the lateral tail vein of immunodepressed mice resulted in 65% and 80% mortality, respectively. (Fig. 2B). By contrast, infection with the Δwc1 mutant only resulted in a 20% mortality rate. The data were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method to compare groups with the log-rank test. The results indicate that the slight difference shown for the wild-type and the Δwc1+wc1 complemented strains was not statistically significant. By contrast, mice infected with the Δwc1 mutant differed significantly in survival compared to those infected with either the wild-type or the Δwc1+wc1 complemented strain (P < 0.01). Thus, mutation of wc1 impairs the virulence of F. oxysporum on immunodepressed mice. Similar results have been reported for BWC1 of the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans which, although not essential for virulence, contributes significantly to the severity of disease (17, 19). The impairment in pathogenicity of the Δwc1 mutant of F. oxysporum might not be attributable to its defects in carotene accumulation and hydrophobicity, two traits previously associated with virulence in mammalian hosts (17, 22, 23), since both alterations were light dependent, whereas during the infection of mice, the fungus remains in the dark. On the other hand, no increased thermosensitivity was observed in the Δwc1 mutant compared with the thermosensitivity of the wild type, as determined by counting colonies originated from spores grown on PDA plates at 37°C. A possible explanation for the reduced virulence of the Δwc1 mutant could be the existence of Wc1-dependent signal transduction pathways in F. oxysporum, controlling the production of other secondary metabolites under dark conditions. According to this hypothesis, the Δwc1 mutant would produce different amounts of those compounds, leading to a decrease in pathogenicity on mice. A recent report on the effects of the inactivation of the white collar gene wcoA of F. fujikuroi showed that the deduced protein is involved in the light-independent regulation of the production of secondary metabolites, such as gibberellins and bikaverins (10). The identification of genes differentially expressed by the Δwc1 mutant during the infection of immunodepressed mice should further elucidate the molecular basis for the role of Wc1 in the virulence of F. oxysporum and other pathogenic fungi in mammalian hosts.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Antonio Di Pietro for helpful discussions and Esther Martínez Aguilera for technical assistance (both from University of Córdoba).

This research was financed by Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa (grants AGR 209 and CVI-138), and grant BIO2004-00276 from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alejandre-Duran, E., T. Roldan-Arjona, R. R. Ariza, and M. Ruiz-Rubio. 2003. The photolyase gene from the plant pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp lycopersici is induced by visible light and α-tomatine from tomato plant. Fungal Genet. Biol. 40159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballario, P., P. Vittorioso, A. Magrelli, C. Talora, A. Cabibbo, and G. Macino. 1996. White collar-1, a central regulator of blue light responses in Neurospora, is a zinc finger protein. EMBO J. 151650-1657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieszke, J. A., E. L. Braun, L. E. Bean, S. C. Kang, D. O. Natvig, and K. A. Borkovich. 1999. The nop-1 gene of Neurospora crassa encodes a seven transmembrane helix retinal-binding protein homologous to archaeal rhodopsins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 968034-8039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borkovich, K. A., L. A. Alex, O. Yarden, M. Freitag, G. E. Turner, N. D. Read, S. Seiler, D. Bell-Pedersen, J. Paietta, N. Plesofsky, M. Plamann, M. Goodrich-Tanrikulu, U. Schulte, G. Mannhaupt, F. E. Nargang, A. Radford, C. Selitrennikoff, J. E. Galagan, J. C. Dunlap, J. J. Loros, D. Catcheside, H. Inoue, R. Aramayo, M. Polymenis, E. U. Selker, M. S. Sachs, G. A. Marzluf, I. Paulsen, R. Davis, D. J. Ebbole, A. Zelter, E. R. Kalkman, R. O'Rourke, F. Bowring, J. Yeadon, C. Ishii, K. Suzuki, W. Sakai, and R. Pratt. 2004. Lessons from the genome sequence of Neurospora crassa: tracing the path from genomic blueprint to multicellular organism. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 681-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casas-Flores, S., M. Rios-Momberg, M. Bibbins, P. Ponce-Noyola, and A. Herrera-Estrella. 2004. BLR-1 and BLR-2, key regulatory elements of photoconidiation and mycelial growth in Trichoderma atroviride. Microbiology 1503561-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corrochano, L. M. 2007. Fungal photoreceptors: sensory molecules for fungal development and behaviour. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6725-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daiyasu, H., T. Ishikawa, K. Kuma, S. Iwai, T. Todo, and H. Toh. 2004. Identification of cryptochrome DASH from vertebrates. Genes Cells 9479-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Pietro, A., M. P. Madrid, Z. Caracuel, J. Delgado-Jarana, and M. I. G. Roncero. 2003. Fusarium oxysporum: exploring the molecular arsenal of a vascular wilt fungus. Mol. Plant Pathol. 4315-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Pietro, A., and M. I. G. Roncero. 1998. Cloning, expression, and role in pathogenicity of pg1 encoding the major extracellular endopolygalacturonase of the vascular wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1191-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estrada, A. F., and J. Avalos. 2008. The white collar protein WcoA of Fusarium fujikuroi is not essential for photocarotenogenesis, but is involved in the regulation of secondary metabolism and conidiation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45705-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Froehlich, A. C., Y. Liu, J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2002. White collar-1, a circadian blue light photoreceptor, binding to the frequency promoter. Science 297815-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Froehlich, A. C., B. Noh, R. D. Vierstra, J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2005. Genetic and molecular analysis of phytochromes from the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 42140-2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He, Q. Y., P. Cheng, Y. H. Yang, L. X. Wang, K. H. Gardner, and Y. Liu. 2002. White collar-1, a DNA binding transcription factor and a light sensor. Science 297840-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heintzen, C., J. J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2001. The PAS protein VIVID defines a clock-associated feedback loop that represses light input, modulates gating, and regulates clock resetting. Cell 104453-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrera-Estrella, A., and B. A. Horwitz. 2007. Looking through the eyes of fungi: molecular genetics of photoreception. Mol. Microbiol. 645-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huertas-Gonzalez, M. D., M. C. Ruiz-Roldan, A. Di Pietro, and M. I. G. Roncero. 1999. Cross protection provides evidence for race-specific avirulence factors in Fusarium oxysporum. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5463-72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idnurm, A., and J. Heitman. 2005. Light controls growth and development via a conserved pathway in the fungal kingdom. PLoS Biol. 3615-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kihara, J., A. Moriwaki, N. Tanaka, M. Ueno, and S. Arase. 2007. Characterization of the BLR1 gene encoding a putative blue-light regulator in the phytopathogenic fungus Bipolaris oryzae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 266110-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee, K., P. Singh, W. C. Chung, J. Ash, T. S. Kim, L. Hang, and S. Park. 2006. Light regulation of asexual development in the rice blast fungus, Magnaporthe oryzae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 43694-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linden, H. 2002. Circadian rhythms: a white collar protein senses blue light. Science 297777-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linden, H., and G. Macino. 1997. White collar 2, a partner in blue-light signal transduction, controlling expression of light-regulated genes in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 1698-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, G. Y., K. S. Doran, T. Lawrence, N. Turkson, M. Puliti, L. Tissi, and V. Nizet. 2004. Sword and shield: linked group B streptococcal beta-hemolysin/cytolysin and carotenoid pigment function to subvert host phagocyte defense. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10114491-14496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, G. Y., A. Essex, J. T. Buchanan, V. Datta, H. M. Hoffman, J. F. Bastian, J. Fierer, and V. Nizet. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus golden pigment impairs neutrophil killing and promotes virulence through its antioxidant activity. J. Exp. Med. 202209-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, Y., Q. He, and P. Cheng. 2003. Photoreception in Neurospora: a tale of two white collar proteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 602131-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lombardi, L. M., and S. Brody. 2005. Circadian rhythms in Neurospora crassa: clock gene homologues in fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42887-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mooney, J. L., and L. N. Yager. 1990. Light is required for conidiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Genes Dev. 41473-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nucci, M., and E. Anaissie. 2002. Cutaneous infection by Fusarium species in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: implications for diagnosis and management. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35909-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ortoneda, M., J. Guarro, M. P. Madrid, Z. Caracuel, M. I. G. Roncero, E. Mayayo, and A. Di Pietro. 2004. Fusarium oxysporum as a multihost model for the genetic dissection of fungal virulence in plants and mammals. Infect. Immun. 721760-1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prados-Rosales, R. C., C. Serena, J. Delgado-Jarana, J. Guarro, and A. Di Pietro. 2006. Distinct signalling pathways coordinately contribute to virulence of Fusarium oxysporum on mammalian hosts. Microbes Infect. 82825-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shrode, L. B., Z. A. Lewis, L. D. White, D. Bell-Pedersen, and D. J. Ebbole. 2001. vvd is required for light adaptation of conidiation-specific genes of Neurospora crassa, but not circadian conidiation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 32169-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thewes, S., A. Prado-Cabrero, M. M. Prado, B. Tudzynski, and J. Avalos. 2005. Characterization of a gene in the car cluster of Fusarium fujikuroi that codes for a protein of the carotenoid oxygenase family. Mol. Genet. Genomics 274217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vargovic, P., R. Pokorny, U. Holker, M. Hofer, and L. Varecka. 2006. Light accelerates the splicing of srh1 homologue gene transcripts in aerial mycelia of Trichoderma viride. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 254240-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]