Abstract

Mucosal epithelia of the human lower reproductive tract (vagina, cervix, and penile urethra) are exposed to sexually transmitted microbes, including Chlamydia trachomatis. The in vivo susceptibility of each tissue type to infection with C. trachomatis is quite distinct. CD1d is expressed on the surface of antigen-presenting cells, including mucosal epithelial cells, and interacts specifically with invariant NKT cells. Invariant NKT cells play a role in both innate and adaptive immune responses to microbes. Here we assessed CD1d expression in normal reproductive tissues by using immunohistochemistry. Immortalized epithelial cell lines from the human lower reproductive tract (vagina, endocervix, and penile urethra) were examined for CD1d expression and for ligand-induced cytokine production induced by CD1d cross-linking. CD1d expression in normal tissue was strong in the vagina but weak in the endocervix and penile urethra. Gamma interferon exposure induced CD1d transcription in all of the cell types studied, with the strongest induction in vaginal cells. Flow cytometry revealed cell surface expression of CD1d in vaginal and penile urethral epithelial cells but not in endocervical cells. Ligation of surface-expressed CD1d by monoclonal antibody cross-linking promoted interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-15, but not IL-10, production in vaginal and penile urethral cells. No induction was demonstrated in endocervical cells. CD1d-mediated cytokine production in penile urethral cells was abrogated by C. trachomatis infection. Basal deficiency in CD1d-mediated immune responsiveness may result in susceptibility to sexually transmitted agents. Decreased CD1d-mediated signaling may help C. trachomatis evade detection by innate immune cells.

Mucosal epithelia of the human lower reproductive tract are exposed to sexually transmitted microbes. However, the in vivo susceptibility of each tissue to infection by Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and cytomegalovirus is quite distinct. In women, the cervix is typically more vulnerable than the vagina (7, 22, 26). Many previous studies have demonstrated that human female reproductive tract epithelial cells participate in immunological function and are regulated by the actions of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and female hormones (13, 20, 27, 37).

CD1d is a major histocompatibility complex-like glycoprotein that presents self or microbial lipid antigen to natural killer T (NKT) cells (33). In humans, a specific subset of NKT cells expresses an invariant Vα24-JaQ/Vβ11 T-cell receptor and can recognize CD1d on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) through this receptor. CD1d is expressed not only in typical APCs (macrophages, dendritic cells [DCs], and B cells) but also in intestinal epithelial cells (4, 8), foreskin keratinocytes (5), and penile urethral epithelial cells (21). CD1d plays a role in both innate and adaptive immunity to various bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites (reviewed in reference 28). Activation of CD1d-restricted invariant NKT (iNKT) cells enhances host resistance to some microbes in a manner dependent on the level of CD1d expression on APCs (29, 30). In contrast, the activation of iNKT cells promotes susceptibility to some microbes (3, 28). For instance, in the murine lung, the immune responses of iNKT cells to two very closely related microbes, Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia muridarum, are protective and harmful, respectively (19).

The activation of CD1d-restricted iNKT cells in response to microbial invasion is antigen dependent, but these antigens can be derived from the invading microbe or possibly from host lipid antigens (6, 16, 23). Intracellular signaling mediated by surface CD1d utilizes NF-κB, a well-known immune-related transcription factor (32, 38). CD1d-restricted NKT cells can act directly on infected cells, killing CD1d-expressing cells (28). They can also modulate adaptive immune cells by altering Th1-Th2 polarization. Recognition of CD1d by iNKT cells can cause rapid release of both interleukin-4 (IL-4) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) from NKT cells (2). The resultant T helper cell polarization induced by activated iNKT cells differs, depending on the nature of the invading microbe (19). Therefore, CD1d and CD1d-restricted NKT cells serve as a natural bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses to microbes.

The function of CD1d can be addressed experimentally by monoclonal antibody (MAb) cross-linking of cell surface-expressed CD1d (11, 38). CD1d ligation by cross-linking with an anti-CD1d MAb (51.1) induces tyrosine phosphorylation in the cytoplasmic tail of CD1d, subsequent intracellular signaling through NF-κB, and autocrine cytokine release from CD1d-bearing cells. IL-10 is induced by CD1d cross-linking in intestinal epithelial cells (11), whereas IL-12 is induced in monocytes and immature DCs (38).

The expression and function of CD1d in human lower reproductive tract mucosae have been poorly studied, although previous work has demonstrated that CD1d expression is negligible in the upper reproductive tract (endometrial glands) (8). Here we assessed the CD1d expression profiles in a variety of mucosal epithelial sites in the female and male reproductive tracts (endometrium, cervix, vagina, and penile urethra) and addressed the hypothesis that varied expression of CD1d at these sites may invoke tissue-specific differences in epithelial immune responsiveness. Additionally, we have recently demonstrated that C. trachomatis infection results in the downregulation of surface-expressed CD1d in human penile urethral epithelial cells, the most commonly infected cell type in the male, and that this is caused by proteasomal degradation (21). Here, C. trachomatis-infected and noninfected penile epithelial cells were examined for antibody cross-linking of surface CD1d to confirm that C. trachomatis infection alters CD1d-mediated autocrine cytokine production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunostaining for CD1d was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of normal human endometrium, cervix (endocervix and ectocervix), vagina, and penis tissues (obtained under Institutional Review Board approval through Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, and the University of Tokyo). Two to 10 tissue samples from each site were examined. Optimal immunostaining required antigen retrieval via microwave exposure in 0.01 M citrate buffer. A mouse anti-CD1d MAb (NOR3.2; 1:500; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) or an irrelevant, isotype-matched mouse MAb (negative control anti-chlamydial protein antibody, a kind gift from Li Shen, Boston University) was used as the primary reagent. Immunostaining was amplified and detected by standard avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase methodology (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and diaminobenzidine color development (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA). Nuclei were counterstained by standard hematoxylin protocols (Vector Laboratories). Analyses were performed at a magnification of ×200.

Cell lines and IFN-γ treatment.

The endocervical (End1/E6/E7), vaginal (VK2/E6E7) (generous gifts from D. J. Anderson, Boston University, Boston, MA), and penile urethral (PURL) epithelial cell lines used in this study were established from primary epithelial cells that were immortalized by transduction with the retroviral vector LXSN-16E6E7 (12, 21). Cells were cultured in keratinocyte serum-free medium supplemented with bovine pituitary extract, recombinant epidermal growth factor, and calcium chloride (KSFM; Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). For experiments involving IFN-γ, cells were exposed to 100 ng/ml IFN-γ (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) for 1 to 9 h.

Cross-linking with an anti-CD1d MAb.

Epithelial cells were cultured in KSFM in 12-well plates and used at near (80%) confluence. Ten micrograms per milliliter anti-CD1d MAb 51.1 (a kind gift from R. S. Blumberg, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) or an isotype control MAb (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) was added to cell monolayers, which were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 10 μg/ml goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) was added as a cross-linker for 30 min of incubation at 37°C. The cells were washed in PBS one additional time and incubated in the serum-free growth medium without antibiotics for 0 to 24 h.

Flow cytometric analysis.

Single-color flow cytometry was performed to determine cell surface CD1d expression patterns. Reproductive tract epithelial cells were detached from culture plates with 0.05% EDTA in PBS, washed in cold PBS, and incubated with NOR3.2 MAb (1 μg/ml) in PBS for 30 min on ice. For indirect staining experiments, cells were incubated with R-phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 min on ice. Controls were exposed to an isotype-matched irrelevant MAb (1 μg/ml; DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). After washing, the cells were analyzed for PC5 via standard flow cytometry.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and semiquantitative PCR.

One microgram of total RNA was used for the reverse transcriptase reaction with oligo(dT) and an RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Total cDNA reaction samples were used as templates for the amplification of each gene fragment with the PCR Core kit (Applied Biosystems). A primer pair set for each gene was synthesized by Invitrogen Corporation as follows: CD1d (453 bp), 5′-GCTGCAACCAGGACAAGTGGACGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGAACAGCAAGCACGCCAGGACT-3′ (reverse); glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 889 bp), 5′-GGAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGGTGGAGGAGTGGGTGTC-3′ (reverse). Expected single-band PCR products were quantitated with an image analyzer (Scion Image, Frederick, MD) and normalized to GAPDH.

For quantitative PCR, cDNAs were produced via RT of 1 μg of total RNA extracted from the cells as described above with an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Two microliters of fivefold-diluted cDNA was amplified in a thermal cycler (7300 Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystems) with a QuantiTect SYBR green PCR kit (Qiagen, Inc.) and the following primer pair sets: IL-12 p35, commercially available pair (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); IL-10, 5′-AGCTCAGCACTGCTCTGTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCATTCTTCACCTGCTGCTCCA-3′ (reverse) (11); IL-15, 5′-TTCACTTGAGTCCGGAGATGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCATCCAGATTCTGTTACATTCCC-3′ (reverse); β-actin, 5′-GAAATCGTGCGTGACATTAAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAGGCAGCTCGTAGCTTCT-3′ (reverse). The IL-12 and IL-15 mRNA levels were normalized to that of β-actin, the internal control.

Cytokine ELISAs.

Levels of secreted IL-12 and IL-15 were quantified by solid-phase sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; BioSource International, Inc., Camarillo, CA). Briefly, anti-IL-12 or -IL-15 specific antibody was used to coat microtiter plates and 50-μl volumes of culture supernatant samples or cytokine standards were added. Detection required the addition of a biotinylated secondary antibody and standard streptavidin-peroxidase methodology. A standard curve was produced by absorbance measurements at 450 nm for standard samples, and each unknown sample was measured and plotted on the standard curve.

C. trachomatis infection.

Nearly confluent PURL cells were overlaid with C. trachomatis serovar F (strain F/IC-Cal-13) elementary bodies suspended in a sucrose-phosphate-glutamate solution at a predetermined dilution that resulted in 70% of the cells becoming infected (multiplicity of infection = 1). Plates were centrifuged for 1 h, supernatants were aspirated after centrifugation, and cells were cultured for 24 h at 37°C in KSFM.

Statistical analysis.

Quantitative PCR and ELISA data are presented as means ± standard deviations. Experiments were performed independently at least three times. mRNA and protein levels (CD1d, IL-12, or IL-15) were compared to those without treatment or with isotype controls by paired, two-tailed Student t tests. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Expression of CD1d in human normal lower reproductive tract epithelia.

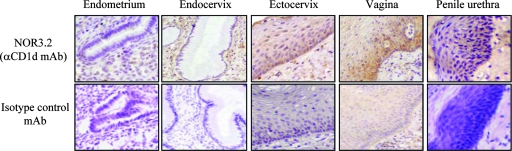

Since CD1d expression in human normal intestinal epithelial cells (4) and epidermal keratinocytes (5) has been demonstrated by immunohistochemistry with the anti-CD1d NOR3.2 MAb, we examined immunostaining of human normal endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, penile urethra, and endometrium with NOR3.2 or isotype control MAbs (Fig. 1). Vaginal epithelium was immunoreactive with the NOR3.2 MAb. CD1d was expressed strongly in the epithelial cells of basal and suprabasal cell layers with negligible immunoreactivity in the intermediate and superficial cell layers. Like the vaginal epithelium, ectocervical and penile urethral epithelia were immunoreactive with NOR3.2 in their basal and suprabasal cell layers, although their immunoreactivity was weaker than that of the vagina. In contrast, immunoreactivity with NOR3.2 was barely detectable in endocervical gland epithelial cells and completely absent in endometrial epithelial glandular cells. In all of the tissues tested, CD1d immunoreactivity was absent in submucosal stromal cells, although several small NOR3.2-reactive cells were detected among the stromal cells that may represent lymphoid cells or DCs. The latter finding is consistent with the previous data obtained from normal skin (5).

FIG. 1.

Immunostaining of human normal reproductive tract epithelia for CD1d. Immunostaining for CD1d was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections of normal human endocervix, ectocervix, vagina, penile urethra, and proliferative-phase endometrium after antigen retrieval. CD1d was detected with NOR3.2, a CD1d-specific MAb (1:500) (upper panels). An isotype-matched control MAb was used as a negative control (lower panels) (magnification, ×200). Results are representative of 2 to 10 normal tissue samples from each site.

Expression of CD1d in genital tract epithelial cells and its induction by IFN-γ.

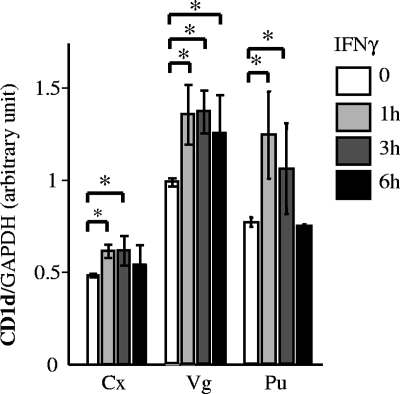

To quantitatively evaluate the CD1d expression levels in epithelial cells representing genital tract mucosal sites, we used immortalized cell lines primarily derived from endocervical, vaginal, and penile urethral epithelia in in vitro assays. These immortalized epithelial cells have been demonstrated to be characteristic of basal and parabasal cell-like cells in each tissue by comparing immunological markers and patterns of differentiation with those of normal tissues (12). Endometrial cells were also not used for this portion of our studies since endometrial epithelia lacked immunoreactivity to NOR3.2 in vivo. Semiquantitative RT-PCR demonstrated basal CD1d expression in endocervical, vaginal, and penile urethral epithelial cells at the transcriptional level (Fig. 2). Basal mRNA levels were clearly the highest in vaginal cells, followed by penile urethral and endocervical cells. The strong expression of CD1d in immortalized vaginal cells was consistent with CD1d immunoreactivity patterns in normal human tissues.

FIG. 2.

CD1d expression in human reproductive tract epithelial cell lines. Immortalized epithelial cell lines derived from the cervix (Cx), vagina (Vg), and penile urethra (Pu) were cultured with or without IFN-γ (100 ng/ml) for 1 to 6 h. cDNA was produced via RT of 1 μg of total RNA extracted from these cells and then amplified by PCR with primer pairs set in the CD1d and GAPDH genes. Expected single-band PCR products were quantitated with an image analyzer (Scion Image, Frederick, MD) and normalized to GAPDH. Mean values with standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate comparisons (exposure versus nonexposure) with statistical significance (P < 0.05; n = 6).

Previous studies have shown IFN-γ-mediated induction of CD1d in some APCs, including macrophages (9), keratinocytes (5), and intestinal epithelial cells (10). The CD1d promoter is upregulated by IFN-γ, possibly through IFN-γ-responsive elements present within the transcription initiation site (9). We therefore addressed the IFN-γ-mediated induction of CD1d expression in reproductive tract epithelial cells (Fig. 2). CD1d transcription was rapidly upregulated by IFN-γ exposure in all of the cell types studied; however, the level and duration of CD1d induction varied among the cell types. Endocervical cells demonstrated minimal CD1d induction, while vaginal and penile urethral cells exhibited more robust CD1d induction. Maximal induction was noted in vaginal cells. In endocervical and penile urethral cells, CD1d transcription increased at 1 h after exposure and returned to basal levels by 6 h after exposure. In vaginal cells, CD1d remained elevated 6 h after of IFN-γ exposure.

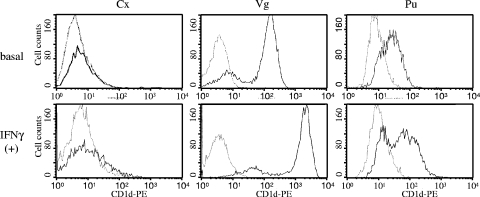

To investigate more thoroughly whether CD1d molecules were expressed on the plasma membrane of each cell line, cells were immunostained with the NOR3.2 antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3). Vaginal and penile urethral cells both expressed CD1d molecules at the cell surface, although expression was stronger in vaginal cells. In contrast, endocervical cells did not express CD1d at the surface despite our prior demonstration of CD1d mRNA in these cells by RT-PCR. Flow cytometric analysis also revealed that the cell surface expression of CD1d clearly increased in vaginal cells after exposure to IFN-γ. Similar exposures in penile urethral cells resulted in much less dramatic changes in cell surface CD1d expression. CD1d expression at the endocervical epithelial cell surface was negligible as revealed by flow cytometry, even in the presence of IFN-γ.

FIG. 3.

Cell surface expression of CD1d in human reproductive tract epithelial cell lines. Immortalized epithelial cell lines derived from the cervix (Cx), vagina (Vg), and penile urethra (Pu) were cultured with or without IFN-γ (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. The cells were stained with the anti-CD1d MAb NOR3.2 and a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig secondary antibody (bold line). Background level staining of the cells with an isotype-matched control antibody is also shown (thin line). The upper and lower panels show cell surface CD1d levels in nontreated (basal) and IFN-γ-treated cells [IFN-γ (+)]. The histograms shown are representative of at least three separate experiments.

Autocrine cytokine production induced by CD1d ligation.

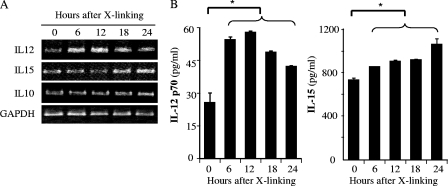

Surface CD1d interacts specifically with iNKT cells bearing an invariant Vα24-JaQ/Vβ11 T-cell receptor. The interaction not only activates NKT cells but also induces phosphorylation of CD1d, intracellular signaling, and the release of cytokines from the CD1d-bearing cell. Anti-CD1d MAb 51.1 can be used for CD1d cross-linking and represents an in vitro model for CD1d ligation (11, 38). IL-10, but not tumor necrosis factor alpha or IL-8, is induced by CD1d cross-linking in intestinal epithelial cells (11); IL-12 is induced in peripheral blood monocytes and immature DCs (38). IL-15 is also produced by a variety of mucosal epithelial cells that play important roles in mucosal immunity to microbes, including intraepithelial lymphocytes and NK and NKT cells (14, 15). To address the function of CD1d in reproductive tract mucosal epithelial cells, here we investigated CD1d ligation-induced autocrine cytokine production from reproductive tract-derived epithelial cell lines. First, penile urethral cells were exposed to an anti-CD1d MAb (51.1) or to an isotype control MAb. Both exposures were followed by exposure to a secondary anti-mouse IgG antibody cross-linker, and the cells were examined for IL-10, IL-12, and IL-15 production (Fig. 4). RT-PCR revealed that transcription of both IL-12 (p35) and IL-15 increased upon cross-linking; IL-10 transcription did not (Fig. 4A). Increases in IL-12 p35 occurred relatively rapidly, while those of IL-15 were comparatively delayed. To examine the autocrine production of IL-12 and IL-15, protein secretion into the culture medium was assessed by ELISA (Fig. 4B). IL-12 p70 secretion peaked at 12 h after cross-linking, while IL-15 secretion increased continuously throughout the first 24 h after exposure. Alterations in cytokine secretion patterns paralleled those seen at the mRNA level. CD1d cross-linking appears to induce the production of IL-12 and IL-15 in penile urethral epithelial cells.

FIG. 4.

Autocrine cytokines production by CD1d cross-linking in penile urethral epithelial cells. Ten micrograms per milliliter anti-CD1d MAb (51.1) was added to a monolayer of epithelial cells and incubated for 1 h. After washing with PBS, 10 μg/ml goat anti-mouse Ig antibody was added as a cross-linker for 30 min. The cells were incubated in serum-free growth medium without any antibiotics for 0 to 24 h. (A) cDNA was produced via RT of 1 μg of total RNA extracted and amplified by PCR with primer pairs for IL-10, IL-12 p35, IL-15, and GAPDH. PCR products were separated over an ethidium bromide-containing agarose gel. (B) Autocrine cytokine secretion from the epithelial cell at each time point was assessed by ELISA for IL-12 p70 and IL-15. Mean values with standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate comparisons (before versus after cross-linking [X-linking]) with statistical significance (P < 0.05; n = 4).

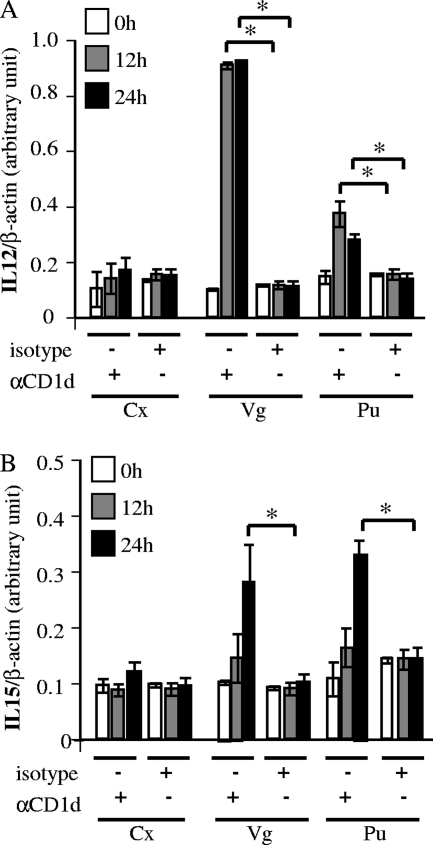

Next, we quantitatively estimated the transcription of IL-12 and IL-15 after CD1d cross-linking in the other available organotypic reproductive tract epithelial cell types (Fig. 5). Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated that IL-12 p35 mRNA levels peaked rapidly 12 h after cross-linking in vaginal and penile urethral cells (Fig. 5A). This induction was particularly strong in vaginal cells and remained elevated for at least 24 h. IL-15 transcription rose, albeit less dramatically, from 12 to 24 h after cross-linking in vaginal and penile urethral cells. These alterations in IL-12 and IL-15 transcription were consistent with the RT-PCR and ELISA data shown in Fig. 4. Endocervical cells did not respond to MAb cross-linking (Fig. 5). Taken together, our results demonstrate autocrine production of IL-12 and IL-15 by vaginal and penile urethral cells, an effect that appears to be mediated through pathways involving CD1d.

FIG. 5.

Quantitative analysis of cytokine production after CD1d cross-linking. CD1d cross-linking was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Anti-CD1d 51.1 (αCD1d) and isotype-matched control (isotype) MAbs were used as primary antibodies for cross-linking. Cells were harvested at 0, 12, and 24 h after cross-linking. IL-12 p35 (A) and IL-15 (B) mRNA levels were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR by SYBR green methodology. IL-12 p35 and IL-15 mRNA levels were normalized to the β-actin mRNA level. Mean mRNA levels and standard deviations are plotted against time. Asterisks indicate comparisons (isotype versus αCD1d at each time point) with statistical significance (P < 0.05; n = 6). Cx, cervix; Vg, vagina; Pu, penile urethra.

C. trachomatis infection abrogates CD1d-mediated cytokine production.

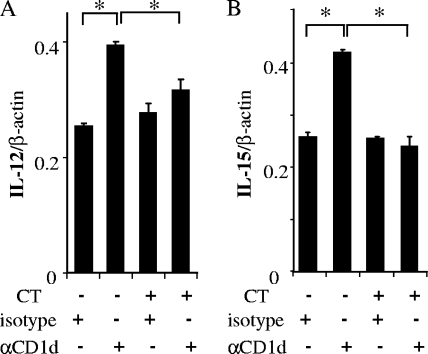

We have previously demonstrated that CD1d is downregulated by C. trachomatis infection through cellular and chlamydial degradation pathways (21). We therefore examined whether CD1d-mediated cytokine production was abrogated in C. trachomatis-infected cells (Fig. 6). In this investigation, we again used immortalized human penile urethral epithelial cells, which represent the most commonly infected cell type in the male reproductive tract. To our knowledge, there have been no published reports on C. trachomatis infection of human vaginal cells. We have therefore limited our further experimentation to those human cells known to be infected with this organism that also express basal levels of CD1d that allow for downregulation. Penile urethral epithelial cells were grown to a monolayer, infected with C. trachomatis, and cross-linked as described previously. Uninfected cells were used as a control. Quantitative RT-PCR revealed the typical increase in IL-12 p35 transcription 12 h after CD1d cross-linking in uninfected cells but no increase in C. trachomatis-infected cells (Fig. 6A). A similar abrogation of the increase in IL-15 transcription was also seen in cells infected with C. trachomatis (Fig. 6B). These differences in CD1d-mediated cytokine production between C. trachomatis-infected and noninfected cells were clearly significant (P = 0.0005 for IL-12, P = 0.0084 for IL-15). Note that IL-12 has been reported to be increased in endocervical secretions after C. trachomatis infection (35). Indeed, a minimal increase in the basal level of IL-12 mRNA was observed in C. trachomatis-infected cells in our experiments, although this increase was not statistically significant. In short, our results indicate that C. trachomatis interferes with CD1d-mediated cytokine production in infected epithelial cells from human reproductive tract mucosa.

FIG. 6.

Abrogation of autocrine cytokine production via CD1d intracellular signaling. Penile urethral epithelial cells were infected (CT+) with C. trachomatis serovar F (multiplicity of infection = 1, 70% infection) and harvested at 24 h postinfection. Control cells (CT−) remained uninfected. Thereafter, antibody cross-linking with the isotype-matched control (isotype) or 51.1 (αCD1d) MAb was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The cells were harvested 12 h after cross-linking. The levels of IL-12 p35 (A) and IL-15 (B) mRNAs were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR and normalized to β-actin. Mean values with standard deviations are presented. Asterisks indicate comparisons (isotype versus αCD1d) with statistical significance (P < 0.05; n = 4).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated in this study that human lower reproductive tract epithelial cells possess surface-expressed CD1d molecules and that they exhibit CD1d-mediated cytokine production. CD1d is known to be expressed in DCs, macrophages, B cells, and epithelial cells. It appears to serve as an essential bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses within the local mucosa, the first responders to invasion by microbes. As shown in our immunohistochemical investigations, epithelial cells represent the primary CD1d-bearing cells within the lower reproductive tract mucosa in humans. Expression at these sites varies, however, with strong expression in the vagina, ectocervix, and penile urethra and very low expression in the endocervix and endometrium. The interaction of CD1d with CD1d-restricted iNKT cells is lipid antigen dependent. This lipid antigen can be derived from invading microbes or possibly from host lipid antigens. Since most sexually transmitted microbes invade the epithelial cells within the reproductive tract mucosa, these cells could be important in the presentation of pathogen-derived lipid antigens via cell surface CD1d molecules. This would be predicted to activate CD1d-restricted iNKT cells and rapidly induce an adaptive immune response to invading microbes.

Our immunochemical data demonstrated that squamous epithelial cells in basal and parabasal cell layers react strongly with anti-CD1d MAbs, in patterns replicating those seen in normal human skin (5). The distribution of CD1d-bearing epithelial cells within the basal and parabasal cell layers may be required for effective interactions between CD1d and the iNKT cells that reside within submucosal tissues. These interactions may occur primarily through CD1d expressed on the basal membrane. CD1d expression patterns in our model cell lines were similar to those of basal or parabasal cells in corresponding normal tissues. Indeed, the immortalized cell lines used in this study have been previously characterized by others as being similar to epithelial cells present in basal or parabasal cell layers in vivo (12). Fichorova et al. have established and used an ectocervical epithelial cell line in several of their investigations. We were not able to examine this ectocervical cell line in our in vitro assays because of its slow growth characteristics. Still, our immunohistochemical study demonstrated that CD1d immunoreactivity and distribution patterns in the ectocervix were similar to those in the penile urethra and the vagina. We hypothesize that ectocervical cells may therefore possess CD1d functions similar to those of the vaginal and penile urethral cells studied here.

Like intestinal epithelia, the endocervical epithelium contains monolayers of glandular epithelial cells. However, we show here that CD1d distribution in the endocervix is quite distinct from that reported in the intestine. Previous studies have demonstrated that CD1d localizes to the apical and lateral membranes of the small intestine and colon (31). By contrast, CD1d immunoreactivity in the endocervix was negligible at apical and lateral membranes. Our flow cytometric and RT-PCR analyses confirmed that endocervical epithelial cells do not present CD1d molecules on the cell surface despite CD1d transcription. Canchis et al. have previously reported that endometrial glandular cells also do not express CD1d (8), a result consistent with our immunohistochemical data. The absence of cell surface CD1d expression in the endocervical and endometrial epithelia may make these sites vulnerable to pathogen attack.

Although IFN-γ induced CD1d production at the mRNA level in all of the reproductive tract epithelial cells studied, the induction patterns of CD1d were quite distinct, depending on cell types. Flow cytometry more clearly revealed the differences in CD1d induction by IFN-γ exposure. Cell surface expression of CD1d was induced markedly in vaginal cells and minimally in penile urethral cells and remained unchanged in endocervical cells. The minimal increase in surface CD1d expression in penile urethral cells may reflect the transient induction in CD1d transcription noted after IFN-γ. In contrast, the induction of both CD1d transcription and translation upon IFN-γ-exposure in vaginal cells appeared significantly more prolonged.

Our investigations have also demonstrated that the human reproductive tract epithelial cells expressing CD1d on their surfaces have the capacity to produce cytokines after CD1d ligation. Vaginal and penile urethral cells increase their production of the Th1 cytokines IL-12 and IL-15 (but not IL-10) in a CD1d-mediated fashion. Since the ectocervix expressed CD1d in a distribution similar to that in the vagina and penile urethra, CD1d-bearing ectocervical epithelial cells may also possess similar CD1d-mediated cytokine production characteristics. Colgan et al. have demonstrated that anti-CD1d 51.1 MAb cross-linking of CD1d expressed at the apical surface of the plasma membrane induces IL-10 in an intestinal epithelial cancer cell line (T84 cells) (11). However, T84 cells are polarized and are known to possess distinct biological plasma membrane characteristics between apical and basolateral sites (24). As discussed in the Colgan report, it is unclear whether signal transduction through basolateral CD1d is the same as that through apical CD1d. Although our CD1d cross-linking experiments used the same anti-CD1d MAb, CD1d ligation induced not IL-10 but IL-12 and IL-15 production in reproductive tract epithelial cells. These cells, however, do not exhibit documented cell surface polarization. Yue et al. have also demonstrated that CD1d cross-linking by several MAbs, including 51.1, induces IL-12 in monocytes and immature DCs (38). Thus, the nature of the cytokine production and signaling induced by CD1d cross-linking may differ, depending on cell type and/or cell surface polarization.

IL-12 is a central mediator in both innate and adaptive immunity and is crucial in the prevention of infectious diseases and tumors (34). IL-12 induces IFN-γ-producing NK, NKT, T helper, and cytotoxic T cells and thereby bridges innate and adaptive immune responses. Yue et al. have demonstrated that CD1d cross-linking rapidly induces phosphorylation of IκB. This, in turn, promotes NF-κB activation and IL-12 production in monocytes and immature DCs (38). Colgan et al. have shown that CD1d cross-linking induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic tail of CD1d in intestinal epithelial cells (11), invoking a mechanism by which CD1d-bearing cells signal downstream pathways that result in cytokine modulation. Here we show the rapid release of IL-12 upon CD1d cross-linking in reproductive tract epithelial cells.

The activation of NF-κB is also associated with IL-15 production. NF-κB binding to the IL-15 promoter region is essential for IL-15 transcription (36). The activation of NF-κB upregulates the expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-6, IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 (1). Our investigations demonstrate that CD1d ligation can induce IL-15, as well as IL-12, production. Like IL-12, IL-15 is released both from classical APCs such as macrophages and DCs and from epithelial cells (25, 30). IL-15 is known to play a key role in mucosal immune responses within the reproductive tract. Using an IL-15 knockout (KO) mouse model, Gill et al. demonstrated that IL-15 is required for the generation of both innate and adaptive immune responses against transvaginal infection with HSV type 2 (HSV-2) (14). They reported that administration of recombinant IL-15 within the murine reproductive tract enables IL-15 KO mice to survive an otherwise lethal infection with HSV-2 and to generate specific adaptive immune responses to HSV-2 (15). Hirose et al. reported that IL-15 is synthesized by epithelial cells after bacterial infection of the intestinal mucosa. Further, this response is accompanied by early stimulation and IFN-γ production by intraepithelial lymphocytes (18). Taken together, our data suggest that interaction of CD1d with cross-linking receptors on iNKT cells can promote IL-12 and IL-15 release from the CD1d-bearing epithelial cells in the human reproductive tract mucosa. This may promote IFN-γ production by T helper, NK, and NKT cells and generate rapid innate and adaptive immune responses. In addition, IFN-γ derived from resident mucosal lymphocytes will upregulate epithelial cell CD1d expression in a paracrine fashion.

We have recently demonstrated that C. trachomatis downregulates the cell surface expression of CD1d by both cellular and chlamydial degradation pathways (21). Bilenki et al. have demonstrated that activation of iNKT cell by α-galactosylceramide exacerbates host susceptibility to C. muridarum infection in the lung while NKT KO and CD1 KO mice acquire increased resistance to the infection (3). In contrast, their group has also revealed that NKT KO and CD1 KO mice display increased susceptibility to pulmonary infection with another chlamydial species, C. pneumoniae; α-galactosylceramide treatment promotes resistance to this infection (19). These divergent immune responses to two distinct chlamydial species are thought to be due to differences in the cytokine profiles induced by activated iNKT cells (19). The production of IFN-γ or IL-4 by iNKT cells induces a Th1 or Th2 adaptive immune response, respectively. Since we here addressed CD1d-mediated cytokine production derived from reproductive tract epithelial cells, the resulting polarization of iNKT cells in response to C. trachomatis remains unstudied. As shown here, IL-12 and IL-15 induction after CD1d cross-linking is abrogated in the C. trachomatis-infected epithelial cell while the baseline level of these cytokines remains stable. The inhibition of CD1d-mediated cytokine production may be a mechanism by which C. trachomatis-infected cells evade (at least temporarily) the bridging of innate and adaptive immune responses that would otherwise occur upon the interaction of CD1d and iNKT cells.

The human endocervix is one of the most common sites of pathogen invasion in the human female reproductive tract, acting as the primary transmission site for many microbes, including HSV, cytomegalovirus, C. trachomatis, and N. gonorrhoeae (7, 22, 26). In contrast, the vaginal wall appears relatively resistant to microbial passage. Previous studies have demonstrated that Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which serve as sentinels in pathogen recognition and help to generate host innate immunity, are expressed differentially in distinct mucosal tissues of the female reproductive tract. The immortalized cervical and vaginal epithelial cell lines used in this study express all TLRs, with the exception of TLR4 and -8 (17). Fichorova et al. reported that the absence of TLR4 is associated with susceptibility to N. gonorrhoeae in the endocervix (13). Our data add a relative deficiency of surface-expressed CD1d to the immune characteristics of the human endocervical epithelium, a quality that may add to its susceptibility to pathogen invasion. In the male reproductive tract, the minimal induction of surface CD1d by IFN-γ in penile urethral cells may influence their susceptibility to many microbes, including C. trachomatis. CD1d expression and CD1d activation of neighboring iNKT cells may play an important role in the generation of innate and adaptive immune responses to microbial infection of the penile urethra, vagina, and ectocervix. This may help to explain the distinct differences in sexual pathogen susceptibility among various sites within the human male and female reproductive tracts.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to C. D. McGahan and L. S. Graziadei for editorial assistance. We also thank Jeffrey Pudney for providing penile urethral tissues (under funding from NIH P01 AI46518).

This work was supported by NIH grants U19AI061972 (A.J.Q. and D.J.S.) and AI046518 (to D.J.S.) and JSPS grand scientific research (C) 18591823 (to K.K.).

Editor: R. P. Morrison

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreakos, E., R. O. Williams, J. Wales, B. M. Foxwell, and M. Feldmann. 2006. Activation of NF-κB by the intracellular expression of NF-κB-inducing kinase acts as a powerful vaccine adjuvant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:314459-14464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behar, S. M., and S. A. Porcelli. 2007. CD1-restricted T cells in host defense to infectious diseases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 314215-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilenki, L., S. Wang, J. Yang, Y. Fan, A. G. Joyee, and X. Yang. 2005. NK T cell activation promotes Chlamydia trachomatis infection in vivo. J. Immunol. 1753197-3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg, R. S., C. Terhorst, P. Bleicher, F. V. McDermott, C. H. Allan, S. B. Landau, J. S. Trier, and S. P. Balk. 1991. Expression of a nonpolymorphic MHC class1-like molecule, CD1D, by human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1472518-2524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonish, B., D. Jullien, Y. Dutronc, B. B. Huang, R. Modlin, F. M. Spada, S. A. Porcelli, and B. J. Nickoloff. 2000. Overexpression of CD1d by keratinocytes in psoriasis and CD1d-dependent IFN-γ production by NK-T cells. J. Immunol. 1654076-4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brigl, M., L. Bry, S. C. Kent, J. E. Gumperz, and M. B. Brenner. 2003. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nat. Immunol. 41230-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byard, R. W., N. Z. Mikhael, G. Orlando, R. M. Cyr, and M. Prefontaine. 1991. The clinicopathological significance of cytomegalovirus inclusions demonstrated by endocervical biopsy. Pathology 23318-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canchis, P. W., A. K. Bhan, S. B. Landau, L. Yang, S. P. Balk, and R. S. Blumberg. 1993. Tissue distribution of the non-polymorphic major histocompatibility complex class I-like molecule, CD1d. Immunology 80561-566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Q. Y., and N. Jackson. 2004. Human CD1d gene has TATA Boxless dual promoters: an SP1-binding element determines the function of the proximal promoter. J. Immunol. 1725512-5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colgan, S. P., V. M. Morales, J. L. Madara, J. E. Polischuk, S. P. Balk, and R. S. Blumberg. 1996. IFN-γ modulates CD1d surface expression on intestinal epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. 271C276-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgan, S. P., R. M. Hershberg, G. T. Furuta, and R. S. Blumberg. 1999. Ligation of intestinal epithelial CD1d induces bioactive IL-10: critical role of the cytoplasmic tail in autocrine signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9613938-13943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fichorova, R. N., and D. J. Anderson. 1999. Differential expression of immunobiological mediators by immortalized human cervical and vaginal epithelial cells. Biol. Reprod. 60508-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fichorova, R. N., A. O. Cronin, E. Lien, D. J. Anderson, and R. R. Ingalls. 2002. Response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae by cervicovaginal epithelial cells occurs in the absence of Toll-like receptor 4-mediated signaling. J. Immunol. 1682424-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill, N., K. L. Rosenthal, and A. A. Ashkar. 2005. NK and NKT cell-independent contribution of interleukin-15 to innate protection against mucosal viral infection. J. Virol. 794470-4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill, N., and A. A. Ashkar. 2007. Adaptive immune responses fail to provide protection against genital HSV-2 infection in the absence of IL-15. Eur. J. Immunol. 372529-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumperz, J. E., C. Roy, A. Makowska, D. Lum, M. Sugita, T. Podrebarac, Y. Koezuka, S. A. Porcelli, S. Cardell, M. B. Brenner, and S. M. Behar. 2000. Murine CD1d-restricted T cell recognition of cellular lipids. Immunity 12211-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M., A. J. Quayle, M. Ficarra, S. Greene, W. A. Rose II, R. Chesson, R. A. Spagnuolo, and R. B. Pyles. 2008. Quantification and comparison of Toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness in primary and immortalized human female lower genital tract epithelia. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 59212-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirose, K., H. Suzuki, H. Nishimura, A. Mitani, J. Washizu, T. Matsuguchi, and Y. Yoshikai. 1998. Interleukin-15 may be responsible for early activation of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes after oral infection with Listeria monocytogenes in rats. Infect. Immun. 665677-5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyee, A. G., H. Qiu, S. Wang, Y. Fan, L. Bilenki, and X. Yang. 2007. Distinct NK T cell subsets are induced by different Chlamydia species leading to differential adaptive immunity and host resistance to the infections. J. Immunol. 1781048-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawana, K., Y. Kawana, and D. J. Schust. 2005. Female steroid hormones utilize Stat protein-mediated pathways to modulate the expression of T-bet in epithelial cells: a mechanism for local immune regulation in the human reproductive tract. Mol. Endocrinol. 192047-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawana, K., A. J. Quayle, M. Ficarra, J. A. Ibana, L. Shen, Y. Kawana, H. Yang, L. Marrero, S. Yavagal, S. J. Greene, Y. X. Zhang, R. B. Pyles, R. S. Blumberg, and D. J. Schust. 2007. CD1d degradation in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected epithelial cells is the result of both cellular and chlamydial proteasomal activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2827368-7375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine, W. C., V. Pope, A. Bhoomkar, P. Tambe, J. S. Lewis, A. A. Zaidi, C. E. Farshy, S. Mitchell, and D. F. Talkington. 1998. Increase in endocervical CD4 lymphocytes among women with nonulcerative sexually transmitted diseases. J. Infect. Dis. 177167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattner, J., K. L. Debord, N. Ismail, R. D. Goff, C. Cantu III, D. Zhou, P. Saint-Mezard, V. Wang, Y. Gao, N. Yin, K. Hoebe, O. Schneewind, D. Walker, B. Beutler, L. Teyton, P. B. Savage, and A. Bendelac. 2005. Exogenous and endogenous glycolipid antigens activate NKT cells during microbial infections. Nature 434525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormick, B. A., C. A. Parkos, S. P. Colgan, D. K. Carnes, and J. L. Madara. 1998. Apical secretion of a pathogen-elicited epithelial chemoattractant activity in response to surface colonization of intestinal epithelia by Salmonella typhimurium. J. Immunol. 160455-466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mention, J. J., M. B. Ahmed, B. Bégue, U. Barbe, V. Verkarre, V. Asnafi, J. F. Colombel, P. H. Cugnenc, F. M. Ruemmele, E. McIntyre, N. Brousse, C. Cellier, and N. Cerf-Bensussan. 2003. Interleukin 15: a key to disrupted intraepithelial lymphocyte homeostasis and lymphomagenesis in celiac disease. Gastroenterology 125730-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyirjesy, P. 2001. Nongonococcal and nonchlamydial cervicitis. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 3540-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen, S. J., L. Eckmann, A. J. Quayle, L. Shen, Y. X. Zhang, D. J. Anderson, J. Fierer, R. S. Stephens, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1997. Secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by epithelial cells in response to chlamydia infection suggests a central role for epithelial cells in chlamydial pathogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 9977-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiraki, Y., Y, Ishibashi, M. Hiruma, A. Nishikawa, and S. Ikeda. 2006. Cytokine secretion profiles of human keratinocytes during Trichophyton tonsurans and Arthroderma benhamiae infections. J. Med. Microbiol. 551175-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sköld, M., and S. M. Behar. 2003. Role of CD1d-restricted NKT cells in microbial immunity. Infect. Immun. 715447-5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sköld, M., X. Xiong, P. A. Illarionov, G. S. Besra, and S. M. Behar. 2005. Interplay of cytokines and microbial signals in regulation of CD1d expression and NKT cell activation. J. Immunol. 1753584-3593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Somnay-Wadgaonkar, K., A. Nusrat, H. S. Kim, W. P. Canchis, S. P. Balk, S. P. Colgan, and R. S. Blumberg. 1999. Immunolocalization of CD1d in human intestinal epithelial cells and identification of a β2-microglobulin-associated form. Int. Immunol. 11383-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanic, A. K., J. S. Bezbradica, J. J. Park, L. Van Kaer, M. R. Boothby, and S. Joyce. 2004. The ontogeny and function of Va14Ja18 natural T lymphocytes require signal processing by protein kinase Cθ and NF-κB. J. Immunol. 1724667-4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taniguchi, M., and T. Nakayama. 2000. Recognition and function of Vα14 NKT cells. Semin. Immunol. 12543-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trinchieri, G. 2003. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, C., J. Tang, P. A. Crowley-Nowick, C. M. Wilson, R. A. Kaslow, and W. M. Geisler. 2005. Interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-12 responses to Chlamydia trachomatis infection in adolescents. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 142548-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Washizu, J., H. Nishimura, N. Nakamura, Y. Nimura, and Y. Yoshikai. 1998. The NF-κB binding site is essential for transcriptional activation of the IL-15 gene. Immunogenetics 481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wira, C. R., J. V. Fahey, C. L. Sentman, P. A. Pioli, and L. Shen. 2005. Innate and adaptive immunity in female genital tract: cellular responses and interactions. Immunol. Rev. 206306-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yue, S. C., A. Shaulov, R. Wang, S. P. Balk, and M. A. Exley. 2005. CD1d ligation on human monocytes directly signals rapid NF-κB activation and production of bioactive IL-12. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10211811-11816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]